Education is a driver of development, but corruption and underfunding weaken this role

Education is a fundamental human right and a major driver of personal and social development. It is regarded as a foundational right, whose achievement is a precondition for a person’s ability to claim and enjoy many other rights. However, in societies where corruption is rampant, there is a great risk that the entire education system will be undermined. Children and adolescents often become familiar with corruption at schools and universities, and corruption in the classroom is particularly harmful as it normalises acceptance of corruption at an early age.c57b72bd9c53 When this happens, a central role of the education sector – to teach ethical values and behaviour – becomes impossible. Instead, education contributes to corruption becoming the norm at all levels of society. Social trust is eroded, and the development potential of countries is sabotaged.

In 2015, countries agreed to pursue 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Goal 4 calls for ‘inclusive and equitable quality education for all.’ However, the 2017 progress report on SDG 4 revealed that worldwide, 263 million children of school-going age were not enrolled in school, including 61 million of primary school age. The 2018 progress report showed that only 41% of children in sub-Saharan Africa and 52% in North Africa and Western Asia attend school. Moreover, many who are in school, especially in Africa and Latin America, do not acquire necessary skills. The 2018 report found that about 617 million youth worldwide of primary and lower secondary school age – 58% of that age group – are not achieving minimum proficiency in reading and mathematics. The reasons include lack of trained teachers and poor school facilities.969efed567c7

Corruption, ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain,’ contributes to poor education outcomes in several ways.f1d48753429c Embezzlement or diversion of school funds deprives schools of needed resources. Nepotism and favouritism can lead to poorly qualified teachers being appointed, while corruption in procurement can result in school textbooks and other supplies of inferior quality. Children, especially girl children, who are harassed for sex by their teachers may drop out of school. When families must pay bribes or fraudulent ‘fees’ for educational services that are supposed to be free, this acts as an added tax, putting poor students at a disadvantage and reducing equal access to education.9bd18c5a6712 Tackling corruption is therefore essential if SDG 4 is to be attained.

An underfunded sector

Governments need a lot of money to provide quality and inclusive education, yet domestic funding is limited. Many poor countries rely on development assistance to fund their education programmes. Table 1 shows the volume of development assistance for education, including official development assistance (ODA) and private grants, from 2012 to 2016.

Table 1. Total development assistance for education from all donors, 2012–2016

|

Year |

Amount |

% of total |

|

2012 |

10,414 |

7.7 |

|

2013 |

10,296 |

6.8 |

|

2014 |

10,811 |

7.2 |

|

2015 |

10,777 |

6.1 |

|

2016 |

12,385 |

6.8 |

Source: Donor Tracker (2018). Includes ODA and private grants reported to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Gross disbursements in 2016 prices.

According to Donor Tracker, development assistance for education reached $12.4 billion in 2016, after some years of stagnation.014223ffd581 Even though assistance to the sector has increased in volume, it is only 7% of total ODA on average. This amount is lower than the estimated $39 billion per year in additional external financing that low-income and lower-middle-income countries would need to attain the SDG on education. Donor countries provided 72%, or $8.9 billion, of the aid received in 2016, while the rest came from multilateral funding bodies such as the Global Partnership for Education, the World Bank, and the European Union.bd440a1d6f9a

Development assistance for education is largely split between three regions. In 2016, 32% of allocations went to Asia (excluding the Middle East), 23% to sub-Saharan Africa, and 16% to the Middle East and North Africa.5d8d214dd2cd Assistance is spread across the different levels of education, with the largest share going to early childhood and primary education (Table 2).

Table 2. Official development assistance spending on education, by subsector

|

Basic education (early childhood education, basic life skills for youth and adults, and primary education) |

33% |

|

Scholarships and living costs for students from developing countries studying in donor countries.* |

22% |

|

General education system strengthening (education policy and administrative management, teacher training, school construction, and education research) |

21% |

|

Secondary education |

13% |

|

Post-secondary education |

11% |

* According to Donor Tracker (2018), this means that one out of five dollars spent on ODA to education stays in the donor countries. For instance, Germany dedicated $1.1 billion or 55% of its bilateral education funding on scholarships, and France spent $782 million or 69% on scholarships. Together, these two countries’ spending on scholarships represents 15% of all development assistance for education

While assistance to education overall falls short of what is needed, government spending on education varies widely across countries and can be very low. For instance, in 2016 South Sudan spent as little as 0.85% of its total government expenditure on education, while St. Lucia spent 21.98%.15cf87f40f32

Types and manifestations of corruption in the education sector

The shortfall in education funding shows the importance of safeguarding the resources available by preventing theft, embezzlement, diversion, and other types of wastage and loss in the system.

The education sector comprises early childhood, primary, secondary, and tertiary educational institutions, as well as administrative structures, accreditation agencies, examination boards, and an array of licensing, inspection, and regulatory authorities. It employs hundreds of thousands of staff, consumes enormous amounts of supplies, and requires a vast infrastructure. The sheer size of the sector makes it susceptible to corruption, given the large sums of money allocated to it and the difficulty of supervision, inspection, and monitoring.202713ee4e0c Furthermore, education is a high-stakes endeavour, valued by both governments and parents, who recognise that education outcomes determine the futures of individuals and the nation. This creates incentives for providers of education services to demand bribes, and for parents and other users of the system to pay up in order not to miss opportunities.7486683709c3

Corruption in education occurs at the political, administrative (central and local), and classroom levels. It takes various forms. However, it is important to remember that corruption in the sector is a symptom of underlying problems. Often there are features of the education system and of a country’s political economy that create incentives for corruption. For instance, high unemployment rates combined with unclear hiring and firing guidelines create an environment in which favouritism in recruitment can flourish. Similarly, poor education facilities, combined with highly competitive single (as opposed to continuous) assessment systems, create incentives for families to purchase private tutoring, which may give rise to opportunities for corrupt gain.5b1a5b759261 In such instances, reforms must address the underlying incentives for corruption in order to be successful. As the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) observed in a report on corruption in education in Serbia:

The most effective prevention measures are those that target the motives of individuals or entities to initiate – or agree to – corrupt transactions and break the law. In education, the perpetrators are seldom criminals. They are mostly regular participants in the system. Their motives to bend or break rules are, often enough, rooted in a perception that education is failing to deliver what is expected, and that bypassing rules is a possible, sometimes even the only available, remedy. Participants in an education system that addresses their needs in the course of its legitimate operation will not have much reason to engage in corruption. Provided there is an effective system of monitoring and control, they will also have little opportunity to do so.44f6f0acb4c9

The prevalence of corruption in the education sector is difficult to determine. Indices such as Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer tell us the prevalence of bribery in accessing public services – for example, 13% of survey respondents from Africa in 2015 paid a bribe to teachers or school officials – but they do not consider other forms of corruption, such as fraud, embezzlement, and theft.a7116f0f35be It is therefore difficult if not impossible to estimate the value of education funds and assets lost in this manner, not only because corruption is hidden, but because there is no concerted effort being made to quantify the losses. One estimate says that up to 30% of development aid in all sectors is lost to fraud and corruption.892e173b1de6 From this, we can extrapolate that a significant portion of aid to the education sector is lost to corruption.

Manifestations of corruption are interconnected and deeply embedded in social, political, and economic dynamics. For instance, a bureaucrat’s demand for a bribe may be linked to expectations and power relations at higher levels of authority, with proceeds of bribery distributed up the hierarchy.0428504c9293 In addition, corruption tends to be highly resilient and adaptive, migrating, adapting, and changing its form in response to anti-corruption measures. Some types of behaviour are similar and reinforce each other. Box 1 provides some examples of corrupt practices in the education sector.

Box 1. Examples of corruption in the education sector

- Illegal charges are levied on children’s school admission forms, which are supposed to be free.

- School places are ‘auctioned’ to the highest bidder.

- Children from certain communities are favoured for admission, while others are subjected to extra payments.

- Good grades and exam results are obtained through bribes to teachers and public officials. The prices are often well known, and candidates are expected to pay up front.

- Examination results are only released upon payment.

- Schools nullify the consequences of failing exams by admitting or readmitting students under false names.

- There is embezzlement of funds intended for teaching materials, school buildings, etc.

- Substandard educational material is purchased due to manufacturers’ bribes, instructors’ copyrights, etc.

- Schools or politically connected companies monopolise the provision of meals and uniforms, resulting in low quality and high prices.

- Teachers on the public payroll offer private tutoring outside school hours to paying pupils. This can reduce teachers’ motivation in ordinary classes and reserve compulsory topics for the private sessions, to the detriment of pupils who do not or cannot pay.

- School property is used for private commercial purposes.

- Pupils carry out unpaid labour for the benefit of staff.

- Teacher recruitment and postings are influenced by nepotism, favouritism, bribes, or sexual favours.

- Teachers or officials take advantage of their office to obtain sexual favours in exchange for employment, promotion, good grades, or any other educational good.

- Examination questions are sold in advance.

- Examination results are altered to reflect higher marks, or examiners award marks arbitrarily in exchange for bribes.

- Examination candidates pay others to impersonate them and sit exams for them.

- Salaries are drawn for ‘ghost teachers’ – staff who are no longer (or never were) employed for various reasons, including having passed away. This affects de facto student-teacher ratios and prevents unemployed teachers from taking vacant positions.

- Teachers conduct private business during teaching hours, often to make ends meet. Absenteeism, a form of ‘quiet corruption,’ can have severe effects on learning outcomes and de facto student-teacher ratios.*

- Licences and authorisations for teaching are obtained on false grounds.

- Student numbers are inflated (including numbers of special-needs pupils) to obtain better funding.

- Bribes are paid to auditors for not disclosing the misuse of funds.

- There is embezzlement of funds allocated by the government or raised by local non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and parents’ organisations.

- Politicians allocate resources to certain schools to gain support, especially during election periods.

- School management and operation is influenced by informal arrangements driven by political interests.

* World Bank (2010).

The examples in Box 1 show that corruption can occur in various education subsectors and at different points in decision-making and supply chains. Risks should be analysed systematically so that anti-corruption can be integrated into a strategic plan for the education sector. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the Global Partnership for Education have published Guidelines for Education Sector Plan Preparation. These do not mention corruption risks but provide a useful framework within which corruption can be analysed, along with other risks such as disasters and conflict. Planners should begin by identifying the common types of corruption and how they affect learning outcomes.88f03cdb2361 The remainder of this section looks at patterns of corruption in two key areas: (a) policy making, planning, and school management, and (b) teacher management and professional conduct.

Policy making, planning, and school management

Policy and funding decisions

Decisions on education policy may be made politically through informal networks of power, outside the appropriate organs and institutions, when politicians exercise undue influence over decision making in the sector. This can affect, for instance, decisions on whether to implement free universal education, engage in private-public partnerships, or build new schools, as well as decisions about government funding for schools and even about curriculum content. Sometimes governments make policy choices that are not feasible, for political reasons. For instance, universal primary education capitation grants may be insufficient and lead to schools charging fees to meet their costs. Political decisions about allocation of funds may lead to wastage when they result in unnecessary projects such as building schools in areas that already have many schools, leaving poor areas underserved. This worsens inequality and undermines equitable development. When public policy decisions consistently and repeatedly serve private interests rather than the public interest, this type of corruption is referred to as ‘policy capture.’a7e434160a75

Procurement and public financial management

Corruption in procurement affects the acquisition of educational material (curriculum development, textbooks, library stock, uniforms, etc.) as well as meals, buildings, and equipment. As sales volume is guaranteed and the monetary value of such transactions is high, bidders eagerly pay bribes to secure the contracts. When bidding procedures are irregular, poor-quality products become the norm, and contracts are frequently secured by unprofessional agents. Diversion and mismanagement of school supplies results in wastage and loss, depriving schoolchildren of the materials they need to learn.

Box 2. ‘Free’ textbooks for sale in Afghanistan

In Afghanistan, there is widespread corruption in the procurement and distribution of school materials. Textbooks are supposed to be issued free to students, yet many parents have reported that the books are sold by government officials, teachers, and students. There are surprisingly few schoolbooks in classrooms. The books present are often outdated and of poor quality, and many do not align with the curriculum. In urban areas, good copies of required textbooks can be purchased in the local market bazaar, but in rural areas some of the books are not available. Ministry of Education officials often send more textbooks to schools where they have better connections and relationships.

Source: MEC (2017).

Box 3. Millions of dollars stolen in Kenya

In 2008, the World Bank and bilateral donors poured millions of dollars into basic education in Kenya. The UK Department for International Development (DFID) alone provided more than $83 million. The money was meant for infrastructure, school supplies, and other needs. In 2009, rumours of fraud and misappropriation started circulating, and the Kenya Ethics and Anti-Corruption Commission compiled a list of more than 40 education officials implicated in theft. However, prosecuting the officials proved difficult: documents went missing, and witnesses refused to testify or just disappeared. In 2011, a forensic audit established that more than $54 million had been misappropriated by ministry officials. Donors pulled the plug: funding was stopped, and the Kenyan government was forced to reimburse donors using taxpayers’ money.

Source: VOA News (2012).

School inspection and licensing

The privatisation and liberalisation of education in the post–Cold War period led to a proliferation of schools across the developing world.3fafc8f936f5 New institutions must be inspected and licensed by the relevant ministry. However, private schools may bribe to get these necessary authorisations, and negligence of duty by school inspectors is also widespread.527c704886c1 The results are potentially devastating to learning outcomes, as schools with poor facilities and unqualified teachers abound.

Student admissions and examinations

In some places, stiff competition for admission to favoured schools creates incentives for corruption in admission processes. In many countries, exam papers or exam questions can be sold in advance to high-paying candidates. Oral examinations are even more open to corruption, as evaluations are subjective and difficult to monitor. Corrupt practices often become routine, as candidates know how much a ‘pass’ costs and expect to pay cash up front. In some places, such as the state of Uttar Pradesh in India, cheating in examinations has become so ingrained that when authorities tried to crack down on it, students protested and demanded their traditional ‘birthright’ to cheat.3b6f1a966f8f

The examination system is central to societies based on meritocracy, and its fairness is crucial to ensuring quality outcomes in education. Corruption in the examination processes puts low-income students at a disadvantage, which reduces their equal access to a better life.

Box 4. Examples of admission and examination fraud from around the world

In Vietnam, bribery in school admissions is widespread. The cost is as high as $3,000 for entry to a prestigious primary school, and between $300 and $800 for a medium-standard school. Paying bribes for admission to desired schools is generally considered a practice only wealthier families can afford.

Source: Transparency International (2013)

In 2014 in Cambodia, a government crackdown on cheating on secondary school exit/university entrance exams led to a dip in the pass rate from 87% to 26%.

Source: Ponniah (2014)

In Romania, fraud, cheating, and grade selling in the public education system is extensive. The upper-secondary exit examination in particular has been characterised by corruption. In 2009, the government started an anti-corruption campaign that included increased surveillance during exams, with increased threat of punishment for cheating. The overall pass rate dropped from 81% in 2009 to 48% in 2011 and 2012.

Source: Borcan, Lindahl, and Mitrut (2017)

In Sierra Leone, one form of corruption involves allowing students to pay for the privilege of retaking exams they have failed. In 2017, three teachers who were also examiners were arrested because they allegedly asked pupils to pay the sum of 150,000 leones, per subject, so that the students could rewrite the exams at a secret location and pass the tests with the examiners’ help.

Source: Thomas (2017)

The Egyptian government deploys police to guard examination papers, which are transported in boxes sealed with wax to curb cheating. This has hardly had any impact, however, with cheating openly discussed on social media and answers uploaded to Facebook and Twitter. Students even developed a question-and-answer-sharing app called Chao Ming, which links Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, LiveLeak, and a private chat component. Students justify their cheating by saying that the exams are too difficult.

Source: Youssef (2016)

After the move towards multiparty democracy in Nigeria in the early 1990s, the government found itself unable to pay public sector salaries on a regular basis. This took a heavy toll on the education sector, as desperate public servants had to find ways to survive. An easy source of income for officials was to sell fake diplomas. This practice quickly proved lucrative, and it has scarcely abated in the two decades since then, leading to many people holding worthless diplomas in Nigeria.

Source: Transparency International (2013)

Private tutoring

Sometimes referred to as the ‘shadow education system,’ private tutoring is worth billions of dollars worldwide. In some countries, household expenditure on private tutoring matches government expenditure on education.c551a6455906 Private tutoring has come to be regarded as indispensable even in better-off economies such as Vietnam and South Korea, where it continues to thrive despite numerous policies and regulations that prohibit the practice.efd1fa7eb464

Education that is supposedly free becomes prohibitively expensive for poor families when private tutoring is required to pass exams and assessments. In some countries, private tutoring is tolerated; however, it is expressly banned in others. Where regulatory and supervisory systems are weak, teachers may try to supplement their incomes by providing paid supplementary tutoring after school hours for their regular pupils despite formal bans. In the worst cases, those that clearly involve an abuse of power for private gain, educators teach only parts of the curriculum during school hours, forcing pupils to pay for the rest during private lessons. Such practices exacerbate social inequities and severely curtail the prospects of the poorest and most vulnerable students.

Teacher management and professional conduct

Irregularities in recruitment, posting, and promotion

Some countries have no clear criteria for teacher recruitment, or existing guidelines are ignored. Recruitment decisions are often based on favouritism and nepotism, sometimes resulting in the appointment of unqualified personnel. Placements in rural schools tend to be unpopular, especially among unmarried and female teachers, and can sometimes be avoided by bribing public officials. Skewed distributions of teacher postings can leave some schools overstaffed and others in crisis. Teachers may bribe or otherwise influence promotion committees. Corruption also occurs in the allocation of loans and scholarships for teacher training and teacher education.

‘Ghost teachers’ are another corruption problem affecting management of human resources in the education sector. The term can refer to teachers who are perpetually absent and rarely show up to teach, or to teachers who simply do not exist. The automation of teacher registration and records creates an opportunity for school heads and inspectors to connive with those in charge of information technology systems to create non-existent teachers, whose salaries they then find ways to appropriate.cf8df6aa94d5 Ghost teachers can also result when teachers die or migrate and their families continue to cash their salary cheques.06156d55f29f In another variation, existing teachers may have double or even triple entries in the system, showing them as being deployed in more than one school simultaneously, with multiple salary streams.02f449c0627c In Nigeria, in the first half of 2016 alone, allegations of ghost teachers or teachers collecting more than their official salary were made in 8,000 cases across four states.f8ca1539ade9

A related phenomenon is that of ‘ghost pupils.’ As school funding grants are often based on the number of pupils at the school, school heads may fudge the numbers to obtain more funds.0c4e770eee95

Teacher misconduct

Motivated and efficient teachers are crucial for quality in teaching. However, in developing countries, there are often complaints of absent teachers, physically abusive teachers, and teachers who demand illegal fees. It is not uncommon to find drunk teachers in schools, or classes where no teaching is conducted at all. A student in a focus group discussion in Afghanistan explained how difficult it can be to deal with this problem:

We wouldn’t dare to complain about teachers. They threaten and hit us with books, iron rulers, and sticks; they punish us. Teachers always encourage intelligent students and repress students who struggle to learn. Teachers love rich students; they attend to [those students] and grade them by favouritism.2879b52b7457

Teacher absenteeism is a widespread problem in many countries. A World Bank study found that absenteeism was as high as 45% in Mozambique and 15% in Kenya. However, even some teachers who were present at school did not carry out their duties.c2fc11a5bc73

Misuse of school property such as vehicles and buildings by teachers and school administrators for private purposes also constitutes corruption.

Sextortion and school-related gender-based violence

Sextortion is abuse of power to obtain a sexual benefit. It is a form of sexual and gender-based violence. At the same time, it is a type of bribery and extortion in which sex, rather than money, is the currency of exchange.6d0d30cf89f0 UNESCO uses the term ‘school-related gender-based violence’ (SRGBV), which encompasses various types of abusive behaviour:

School-related gender-based violence is defined as acts or threats of sexual, physical or psychological violence occurring in and around schools, perpetrated as a result of gender norms and stereotypes, and enforced by unequal power dynamics. It also refers to the differences between girls’ and boys’ experiences of and vulnerabilities to violence. SRGBV includes explicit threats or acts of physical violence, bullying, verbal or sexual harassment, non-consensual touching, sexual coercion and assault, and rape. Corporal punishment and discipline in schools often manifest in gendered and discriminatory ways. Other implicit acts of SRGBV stem from everyday school practices that reinforce stereotyping and gender inequality, and encourage violent or unsafe environments.9f4f130efff6

In a study of sexual violence in Botswana in 2001, 67% of girls reported sexual harassment by teachers, and 11% of the girls surveyed had seriously considered dropping out of school due to harassment (even though Botswana provides 10 years of free education). One in ten girls had consented to sexual relations for fear of reprisals affecting their grades and performance records. In Côte d’Ivoire, a survey by the Ministry of National Education found that 47% of teachers reported having solicited sexual relations from students.396c32dfaad7

Margaret, a grade 7 student in Malawi, describes how sexual demands by teachers can derail girls’ education:

The teacher can send a girl to leave her exercise books in the office and the teacher follows her to make a proposal for sex, and because she fears to answer no, she says I will answer tomorrow. She then stops coming to school because of fear … The girls are afraid to tell their parents, because they feel shy when they have been proposed, so they prefer staying at home … If the girl comes to school then the teacher can become angry and threaten that she will fail … If the girl accepts the teacher then she can become pregnant and drop out.5f878ace4664

Exploitation of child labour in schools

In some cases, teachers or administrative personnel at schools may force students to participate in child labour. After an explosion at a primary school in the province of Jiangxi, China, in 2001, it was revealed that the school had been using the children to assemble fireworks since 1998. The proceeds enabled officials to pay teachers and cover the school budget, while also making a nice profit for the Communist Party cadre. Before the explosion, parents and students had complained about the practice, but the school said that it was mandatory.d744ceaebbf5

In 2015, Human Rights Watch reported the commercial exploitation of children in Quranic schools (daaras) in Senegal. Parents send children to learn the Quran at boarding schools where Quranic teachers become de facto guardians. However, many so-called teachers use religious education as a cover for economic exploitation of the children in their charge. The teachers, usually male, force their students to beg for money, and for rice and sugar for resale, and inflict severe physical and psychological abuse on those who fail to meet their daily quota. As punishment, children are frequently chained, bound, and forced into stress positions.ab585d6b4325

The examples above illustrate some of the ways in which corruption manifests in the education sector. There are differences as well as commonalities across different countries. Therefore, it is important for any reform process to begin with a risk assessment, or other means of mapping the types of corruption in the education sector of a given country and the underlying reasons or incentives that allow corruption to flourish. The next section looks at various methods that can be used to assess corruption risks as part of an education sector situation analysis.

Assessing corruption risks in the education sector

There are several ways of assessing corruption risks in a given context. The methods and models suggested here include political economy analysis, power and influence analysis, corruption risk assessment, systems mapping and integrity of education systems assessments. The list is not necessarily exhaustive as these are not the only methods that can be applied to assess corruption risks in the education sector. Indeed, development actors are encouraged to adapt them or come up with approaches that will be appropriate to the context because corruption types and manifestations differ from country to country. The approaches suggested here have several things in common, so development actors can use them singly or adopt a combination of them that will suit the specific needs of their development programmes. Therefore, readers are encouraged to explore the suggested methods in more detail before applying them.

Political economy analysis

Today, there is increasing expectation that political economy analysis (PEA) will precede the implementation of major development interventions. This reflects, in part, the disappointing results of many traditional, highly technical development programmes, which looked good on paper but fell short when implanted in a specific country context. The purpose of PEA is to understand the political context in a country: in other words, to understand why things happen instead of how they happen.812d45c2054f As the OECD defines it, ‘Political economy analysis is concerned with the interaction of political and economic processes in a society: the distribution of power and wealth between different groups and individuals, and the processes that create, sustain and transform these relationships over time.’48b8a032ac8e

PEA is particularly concerned with mapping and understanding the structural and contextual background that shapes the political and institutional environment. This involves analysing the political settlement in a given polity, that is, ‘the written and unwritten laws, norms and institutions that underlie the political order of a state and maintain a balance of power between elites.’4da7a3493370 Analysing these issues involves understanding the political bargaining process – the formal and informal mechanisms through which actors engage with each other – and identifying the stakeholders or agents who participate in this process. It is also important to understand the ideas and motivations that shape the actions of stakeholders, such as money, political ideology, or religion.c35087e6b251

A political economy analysis is a prelude to an approach known as 'Doing Development Differently', (DDD), which seeks to move away from analysis as a one-off enterprise, or one done at regular intervals, and towards a more continuous and iterative process.95af8cf2ec72 Doing Development Differently emphasises that development interventions should be politically smart – aligned as much as possible with political will and incentives – and locally led. PEA is not a magic bullet, but it can support more effective and politically feasible development strategies by revealing the risks of chosen interventions and setting realistic expectations of what can be achieved.1e5135a66ab4

At the sector level, PEA can reveal opportunities for reforms and explain why previous reforms have stalled. It can identify institutions and individuals both within and outside the government with the power and influence to propel or stifle reforms. A mapping of the sector enables practitioners to design structural interventions that are better informed by contextual realities and therefore more technically and politically feasible.

A PEA of the education sector can help practitioners understand the contextual realities of the sector. For instance, what sort of economic model is involved? Do the country’s rulers want to use education to create a skilled workforce, as one element of a broad national development project, or are they using education provision as a mechanism to secure support from elite groups and their followers? The answers to these sorts of questions are important because they reveal where the risks for corruption are greatest and what sort of reforms are possible.

Wales, Magee, and Nicolai of the Overseas Development Institute studied how variations in political context shape education reforms and their results. They describe three ideal-types of political settlement – developmental, hybrid, and predatory – and their potential for development gains, illustrated below in Table 3. A PEA approach enables practitioners to design appropriate interventions.c0366f508e60 Wales et al. argue that even in difficult political contexts, it is often possible to improve access at both the primary and secondary levels sufficiently to allow sustained and near-universal access to education. They advise that reforms are best initiated during periods of transition: for example, when a new group takes power, or when some social groups become more powerful than they were before for one reason or another.

Table 3. Political settlement types and education sector development potential

|

Developmental |

Hybrid |

Predatory |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

High development potential

|

Moderate, sector-dependent development potential

|

Low development potential

|

|

Development partner strategy

|

Mixed strategy

|

Reform unlikely to succeed, but impact possible

|

Source: Adapted from Wales, Magee, and Nicolai (2016).

Power and influence analysis

Closely related to PEA is power and influence analysis. This is based on the premise that governance shortcomings are due to the existence of strong informal rules and networks that can contradict, undermine, or interfere with the operation of formal legal and regulatory frameworks. Power and influence analysis involves an iterative process of institutional/stakeholder mapping through purposively selected stakeholder interviews. The aim is to identify discrepancies between formal and informal authority relations, accountability lines, and incentive structures. Understanding the way such informal rules and networks affect the incentives and motivations of key stakeholders in the sector of interest is a prerequisite to identifying strategies that can improve governance outcomes in a specific context.2cc61f967eb2

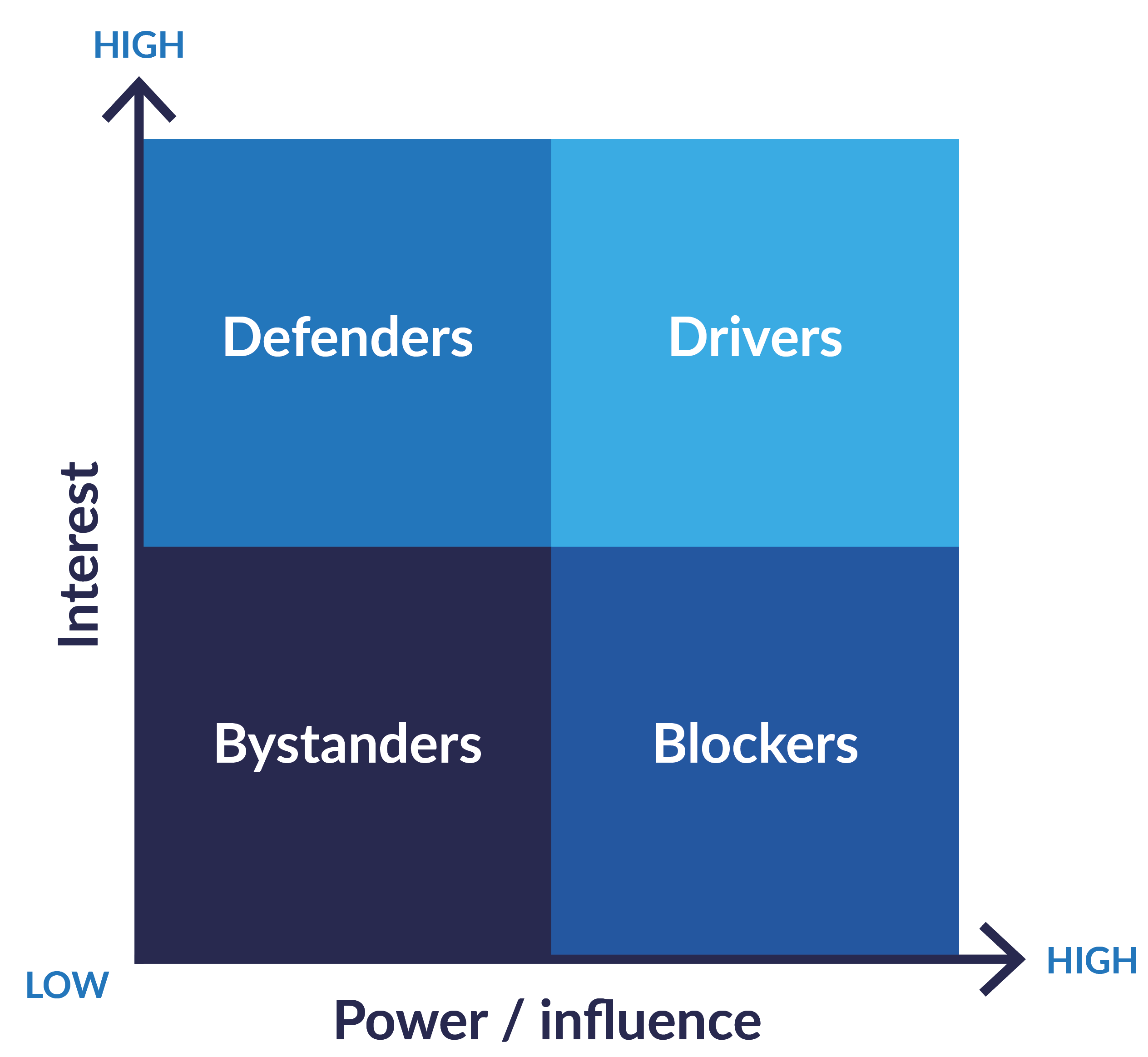

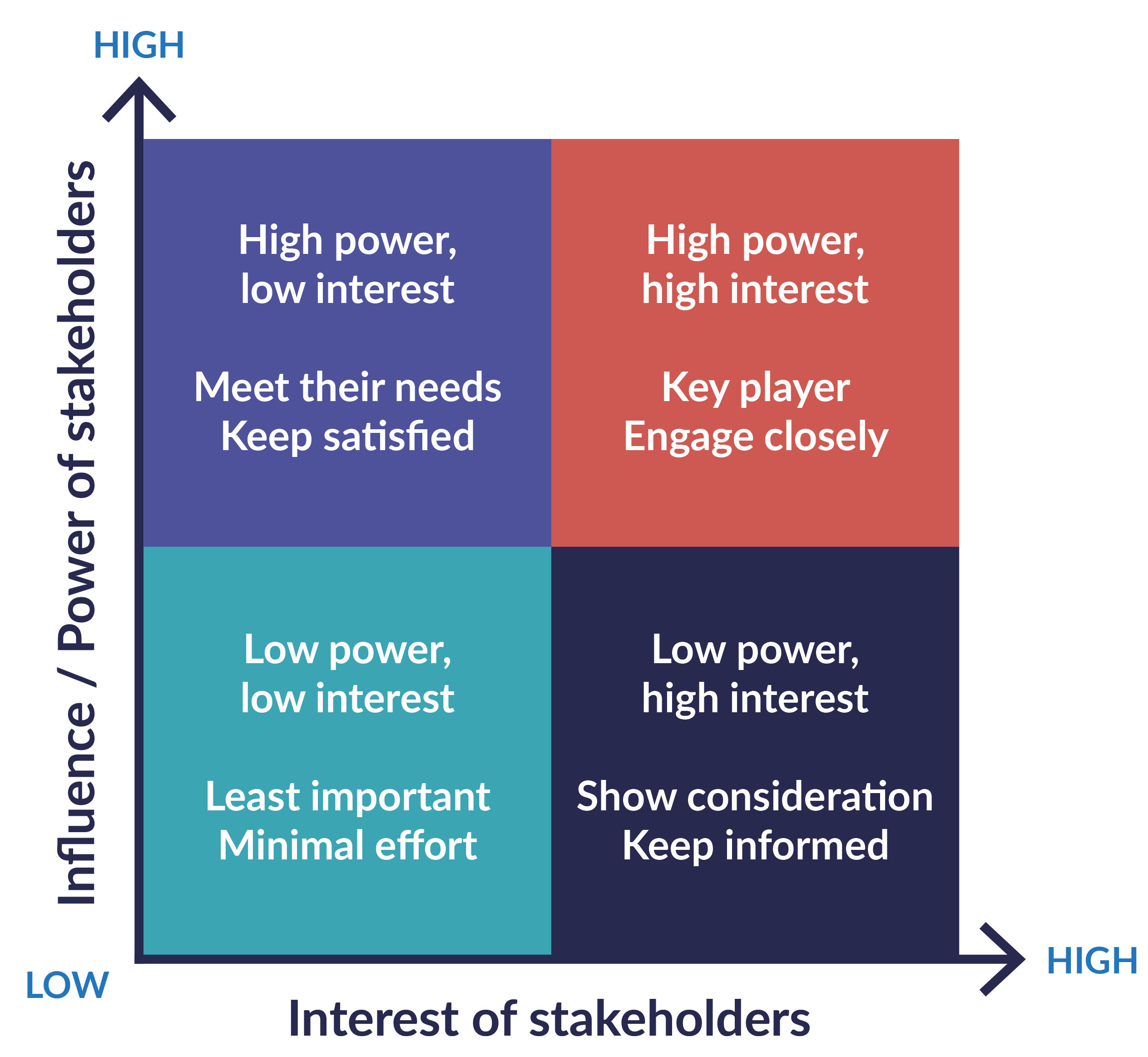

Figures 1 and 2 show how to map power and influence in a manner that will deepen practitioners’ understanding of a sector and help them decide who should be engaged and how they should engaged.07f5f5002f41 The stakeholders with high power and high interest, known as ‘Drivers’ are crucial, and should be most closely engaged, while those with low levels of power and low interest ‘Bystanders’ require the least engagement and should merely be kept informed of the process. Those with high interest but low power, the ‘defenders’ should be closely engaged too, as they can play a significant role in advocating for changes. Those with high power but low interest are potential ‘blockers’ and therefore it is important to avoid antagonising them, to ensure that their needs are met and that they are satisfied with the process and suggested reforms.

Figure 1. Stakeholder analysis matrix comparing the interest of each actor with their perceived power and influence on policy

Source: McMullan et al. (2018).

Figure 2. Stakeholder interest/influence matrix

Source: Cordell, n.d. (Showme.com).

Corruption risk assessments

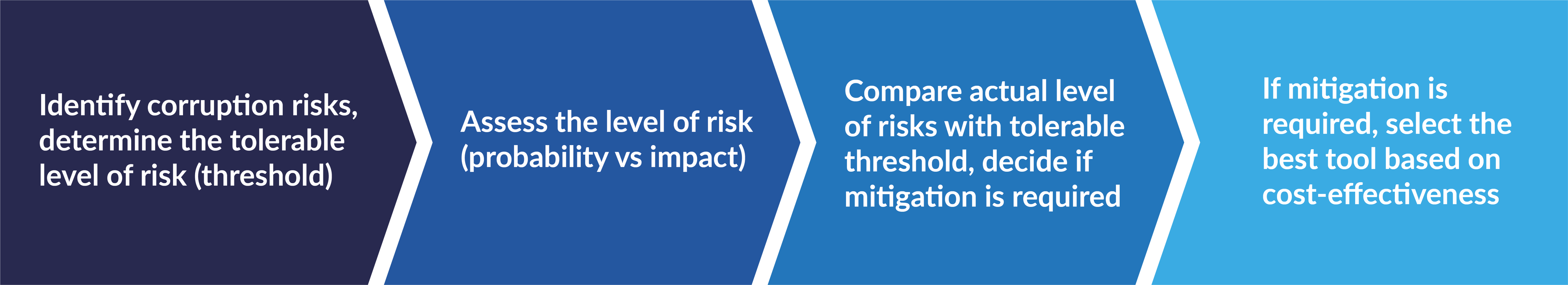

In 2015, U4 published a four step corruption risk management model illustrated in Figure 3, below. This model recommends a systematic risk assessment, followed by defining risk thresholds and then choosing risk mitigation measures based on a simple cost-benefit analysis.25f52cb67fce The model emphasises the following elements:

- The criteria for tolerable levels of risk should be formulated;

- Risk assessments should consider both the probability of the risk occurring and the impact the risk is expected to have on the development outcomes in question;

- Risks should be prioritised based on a cost-effectiveness approach as opposed to a control-based approach, because the aim is not to eliminate risk but to increase gains;

- Risk mitigation strategies need to flow from risk assessments, based on the notion of acceptable risk and on cost-benefit considerations.

Figure 3. Corruption risk management process

Sources: This model was developed by Johnson (2015) and draws on the risks management approach recommended by the International Organisation for Standarization (ISO) and its 31000 framework; the Deming quality cycle; and the model developed by Leitch (2016).

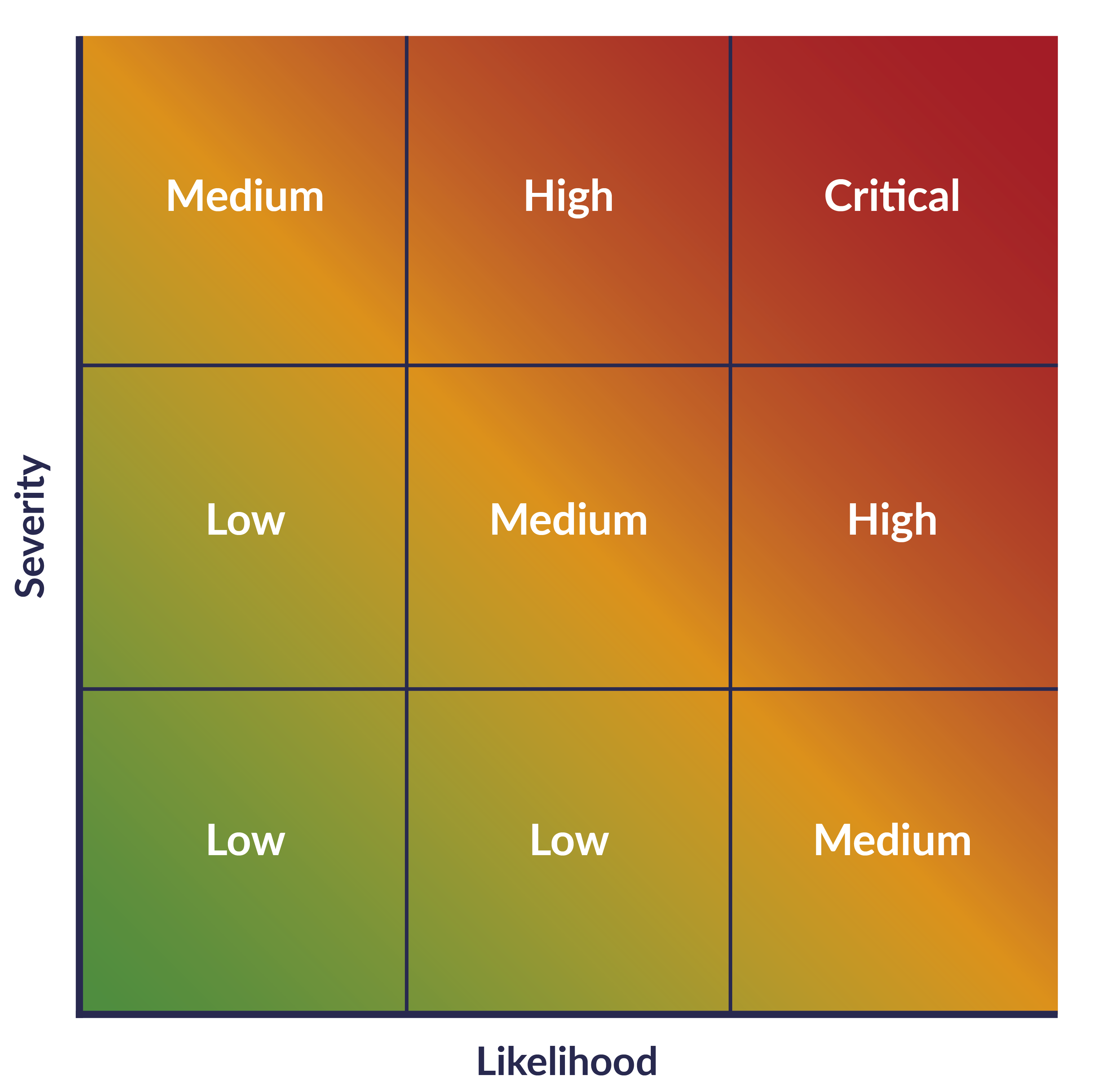

The four-step corruption risk management model builds on standard components of risk management processes in development cooperation but incorporates insights from the broader risk management literature. Step 1 is to identify corruption risks and determine risk tolerance. Step 2 is to assess the level of risk, that is, the likelihood that a hazard will occur and how severe the impact of its occurrence would be. A risk heat map, such as the one shown in Figure 4, is a helpful way to visualise this. Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys (PETS) can help assess the level of risk by identifying the amount of leakage (waste + corruption) in a financial flow. In the education sector, PETS can be used to identify the discrepancy between a disbursement from the ministry of finance and the amount spent by a school. Development actors should carefully consider what tools they will use to determine the risks and then decide on mitigation measures.

Figure 4. Risk heat map

Step 3 is to compare the actual risk with the tolerable risk and decide whether mitigation is required. Evaluating risk helps practitioners identify which types of corruption within the sector should be targeted first: that is, how to prioritise anti-corruption interventions. Ideally, risks that pose the greatest threat of harm should be the priority. However, and a cost-benefit analysis can help in making this decision.

When evaluating which types of risk to prioritise, the political feasibility of addressing different types of corruption also matters. Therefore, it is necessary to modify step 4 by choosing not just the most cost-effective strategy, but also the most politically feasible one. This means, taking into account levels of power and influence as discussed above. It requires development practitioners to work in a politically informed way by identifying windows of political opportunity, especiallyfor instance, where there are politicians or public officials – ‘local convenors,’ in the ‘Doing Development Differently’ (DDD) terminology – who can mobilise actors and carry reforms forward. Another way is to identify pre-existing ‘islands of effectiveness’ or integrity and build on those.c7ba286a4505

A corruption risk management approach such as the one above promotes a quantitative assessment of the costs of corruption that can inform the choice of interventions to prevent corruption. Cost-benefit considerations should determine which corruption risks are prioritised, so that high levels of wastage and loss can be prevented through appropriate public financial management controls.

Systems mapping and analysis

In developing countries, corruption is often not the exception to the rule, but an entrenched system. This is true infor the education sector as well. However, although corruption is a complex problem, analyses often frame it as a simple, one-dimensional, cause-effect relationship. To tackle corruption adequately, it is crucial to recognise that it is complex and non-linear, and that multiple causes and actors are interlinked with each other. Systems analysis is grounded in the assumption that to understand how corruption functions, one needs to identify its enablers and drivers, how they are related, and how they interact with the larger socioeconomic, political, and cultural context. Various factors are analysed as part of a dynamic system and visually represented in a systems map. A systems map can be used to:

- Understand multiple perspectives on causes of corruption and how they interact.

- Gain new insights into opportunities for intervention in the system.

- Identify potential effects of an intervention, including unintended negative consequences, and sources of resistance to the intervention.

- Guide coordination, so that multiple actors can strategically allocate their resources in a way that complements an overall anti-corruption strategy.13eda589266f

An example of applying systems analysis and corruption systems map can be seen in work by the CDA Collaborative Learning Projects.ca6356b06edd Even though their systems map was developed in relation to the criminal justice sector, it is relevant to and can be adapted to education to show incentives and ways of thinking that lead to or reduce corruption.

The INTES approach

Integrity of Education Systems (INTES) is a corruption risk assessment methodology that has been developed specifically for the education sector. It was pioneered by the Open Society Foundation to address corruption in secondary and higher education in Armeniab582fe274263 and has also been applied by the OECD to assess integrity in the Ukraine education sector.b1c2a258c5a5 The methodology is designed to support national authorities, civil society, and other participants in the education sector as they work to develop effective solutions to corruption in schools and universities.

The approach is based on recognition that corruption in education is not a stand-alone phenomenon but a consequence of deeply rooted problems in the education system and the society that it serves. INTES posits that tackling the visible manifestations of corruption, such as bribing, cheating, and stealing, is reactive and insufficient to tackle the root causes that have made such problems pervasive. Understanding why perpetrators do what they do is key to designing proactive, as opposed to reactive, solutions.

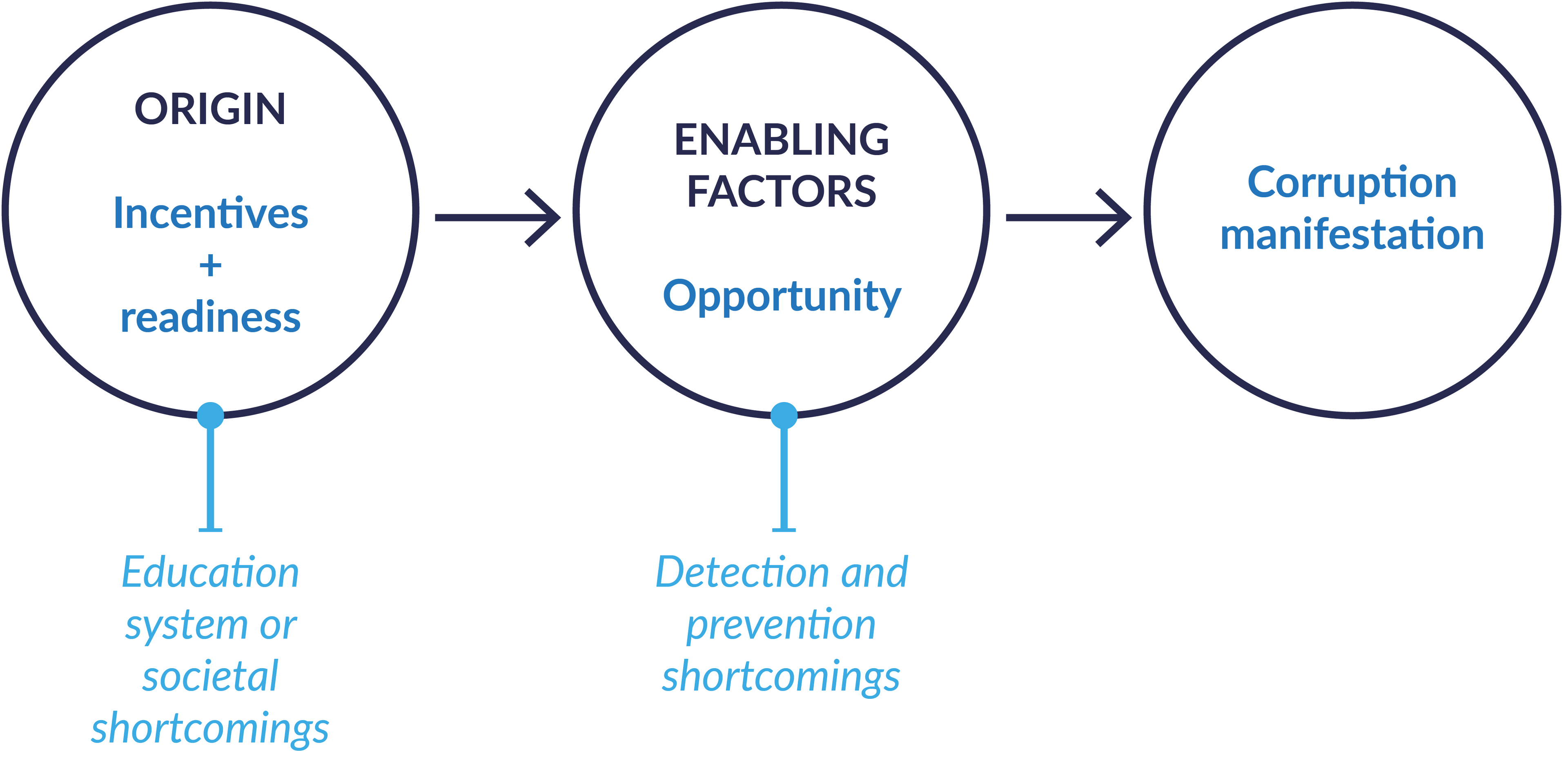

INTES treats corruption violations as the final stage in a corruption process (see Figure 5). This process originates in a combination of various factors at education system level, or even broader problems in the political economy, and ends in manifestations of malpractice that are reported in the media and in corruption surveys.

Figure 5. Understanding education sector corruption using INTES

Source: Adapted from Milovanovitch (2015).

To reveal what happens at different stages of the corruption process, types of corruption are situated within the broader integrity context within which they take place. The next step is to see how the context and offense are related. The method tries to answer the following questions:

- What is the violation?

- How does it happen?

- Why does it happen?

In this way, it is possible to reveal the root causes of violations and to identify (a) factors that make the offense possible, and (b) factors that create incentives for the perpetrators to commit the offense. This allows a more comprehensive approach to finding solutions. An advantage of the INTES method is that it combines assessing risks and finding solutions in an easily understandable process matrix, illustrated in Table 4.

Table 4. INTES assessment logic and sequence

| INTES phase | Step | INTES logic | Lead question | Task |

|

Phase I: Identification |

Step A |

Education corruption |

What? |

Determine what counts as integrity violation |

|

Phase II: Causal analysis |

Step B |

Failing prevention and detection = opportunity |

How? |

Determine what opens opportunity for the violation |

|

Step C |

Failing education services = incentive |

Why? |

Determine what creates incentive for the violation |

|

|

Phase III: Solutions |

Step D |

Formulate action |

||

Source: Adapted from Milovanovitch (2015).

Guiding principles for assessing and mitigating corruption risks in education

The approaches described above can be used separately or in combination to assess corruption in education. In either case, there are some important principles to bear in mind. These have been adapted from the UNESCO guidelines on education sector planning and the Doing Development Differently (DDD) approach, and are briefly summarised below.5e87e338dcf7

Country leadership and ownership

Assessing corruption risks in education should be a country-led process. The DDD approach says that successful reform initiatives:

- Focus on solving local problems that are debated, defined, and refined by local people in an ongoing process.

- Are legitimised at all levels (political, managerial, and social), building ownership and momentum throughout the process so that they are ‘locally owned’ in reality, not just on paper. It is important to have buy-in from powerful stakeholders who may otherwise capture or sabotage reforms. It is equally important to include marginalised and excluded groups to ensure the legitimacy of reforms.214f0e3083ac

- Work through local conveners. These are intrinsically motivated local actors who have the needed knowledge, networks, and creativity to facilitate reforms.fb8c75d3f43e One caution is that reforms dominated by individuals can dissipate when these persons leave their positions and move elsewhere. Therefore, it is important to ensure institutional memory and mentorship so that reform momentum is maintained.c330c4a5e4a8

Participation

A corruption risk assessment is conducted as part of the situation analysis that informs education sector planning. UNESCO recommends that this be participatory. The process should involve a policy dialogue that builds consensus on the development of the education system. It should allow political leaders and technical experts to find a balance between ambitions and constraints, as well as raising awareness and gaining the commitment of a wide range of education stakeholders. The DDD Manifesto says that local convenors should mobilise all those with a stake in progress, in both formal and informal coalitions and teams, to tackle common problems and introduce relevant change.3c51d9d4843b

Corruption risk assessment should also involve other concerned ministries such as the ministry of finance, various levels of education system administration, stakeholders in the education sector and civil society, traditional leaders, the private sector, non-governmental education providers, and international development partners. In line with the rights-based approach, a diversity of groups – such as urban and rural people, men and women, persons with disabilities, and ethnic minorities – should be consulted. This is important because corruption affects different groups differently, and anti-corruption interventions should take these differences into account. Their involvement can be secured through consultations during the plan preparation process or through structured discussions on drafts of the plan document. Another reason for ensuring broad participation is that strong coalitions can overcome embedded informal networks of power that facilitate corruption, and multi-stakeholder partnerships can defeat predatory pressures by mobilising for collective action against corruption.7cef556efaeb

An example of a coalition that played a role in curbing corruption in the education sector is the Textbook Count initiative in the Philippines. A national-level NGO, G-Watch, spearheaded a civil society coalition in partnership with government reformers to provide independent monitoring of the textbook supply chain. In a context characterised by systemic corruption, leakages were rampant, and many textbooks were of poor quality or never delivered at all. The initiative combined civil society engagement, coordination with reform champions in the national Department of Education, and mobilisation of membership organisations such as the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts of the Philippines to oversee the complete process of procuring, producing, and delivering the books. G-Watch monitored procurement and purchase at national level. A partnership with the Coca-Cola Company enabled textbooks to be loaded onto Coca-Cola trucks that could penetrate deep into the country to ensure that textbooks were delivered to far-flung areas. Boy Scouts received the textbooks and ensured their delivery to schools.00f72254036e This example shows what can be achieved if practitioners ‘think outside the box’ when they identify potential collaborators and stakeholders.

Organisation and process planning

A corruption risk assessment carried out as part of a planning process should be well organised and coordinated to foster a common understanding of the problems and facilitate appropriate solutions and strategies. Since a wide range of actors are involved, it is important to map the actors and clarify their roles and responsibilities in the process. A steering committee composed of ministry officials and representatives from other groups such as development partners, private sector actors, and civil society organisations (CSOs) should guide the process.2ce417103c31

UNESCO emphasises that the planning process is just as important as the final output, the education sector strategic plan. The process also serves to build the capacity of actors. Similarly, the DDD approach emphasises that local convenors should blend design and implementation through rapid cycles of planning, action, reflection, and revision, drawing on local knowledge, feedback, and energy, to foster learning from both success and failure.c88b2333cb23

Prioritisation: Small bets, sequencing, feasibility, and high impact

When choosing interventions, it is important to focus on making ‘small bets,’ that is, focusing on a few activities that are likely to be feasible and to have a high impact. Successful interventions are ‘politically smart’: they align the interests and capabilities of powerful organisations at the sectoral level in order to ensure the enforcement of sets of rules.f82ad6935ce4 This makes it possible to build trust, empower people, and promote sustainability. Interventions can be sequenced over one or more planning periods. The reason for incremental, as opposed to comprehensive, reforms is that in many developing countries the incentives, political will/authority, and long-term outlook necessary for comprehensive reform to succeed do not exist. Prevailing political and institutional arrangements do not lend themselves to sweeping reforms that might threaten the political order, so windows of opportunity for far-reaching changes are rare. Instead of ambitiously trying to tackle everything at once, it is better to secure some short-terms gains in the forms of islands of effectiveness (or islands of integrity in this case), which can then provide the foundation for cumulative gains over the long term.84bdf3d8beb2

Anti-corruption in the education sector: Tools and strategies

Once risks have been assessed, actors and systems mapped, and incentives identified, appropriate interventions can be designed and implemented. They should be adapted to the local context so that they are a good fit. Anti-corruption interventions can be categorised in different ways. One way is to distinguish between interventions that promote transparency and those that promote accountability. Another way is to classify interventions based on whether they play a role in the prevention, detection, or sanctioning of corruption. However, some strategies can enhance both transparency and accountability, and some can be used to both prevent and detect corruption, leading to sanctions. Some key factors to bear in mind when choosing a strategy are (a) political feasibility, (b) cost, and (c) the social and economic context, for instance, gender roles, literacy levels, internet access, and other factors that affect civic engagement.

Transparency-promoting tools and strategies

The role of ICTs

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) have become important in promoting transparency in governance. This has been achieved through email and SMS mechanisms for complaints and feedback, open data initiatives, digital right-to-information platforms, interactive geo-mapping, voice reporting and citizen journalism, blogs, wikis, and information management systems.db5d398b0be4 Social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter have also improved the interaction between service delivery agencies and the public. Many public agencies’ websites include links that citizens can use to ask questions or complain about service delivery. India’s ‘I Paid a Bribe’ website is one of the best-known platforms for crowdsourcing complaints about bribery.9099954f75ea Additionally, digitisation and automation can reduce opportunities for bribery by eliminating or decreasing face-to-face interactions between citizens and bureaucrats.c524a186c2dc Mobile money transfers, for example, facilitate direct cash transfers to the poor and displaced, greatly reducing the risk of leakage, diversion, and theft in social protection programmes.ba536c682a23

Technology is changing the way examinations are supervised. In Romania in 2011, closed-circuit television (CCTV) monitoring of exams was introduced to tackle endemic fraud. This was accompanied by credible threats of punishment for misconduct: students caught cheating would be banned from retaking the exam for at least a year, while teachers caught receiving bribes could receive a pay cut or a prison sentence or both. The initiative was introduced in response to widespread cheating on the 2010 baccalaureate exams, where teachers distributed answers to students. As soon as monitoring was introduced, exam outcomes dropped sharply, and by 2012 the pass rate had been cut almost in half compared to 2009. Research by Borcan, Lindahl, and Mitrut (2017) found that the campaign was effective in reducing exam fraud but had the unintended effect of increasing score gaps between poor and better-off students, reducing opportunities for the less privileged to enter elite universities. Other countries that have used CCTV to supervise exams include the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Moldova, Cambodia, and India.d2b46e1f2369 A key to the success of CCTV monitoring is consistent and strict application of the rules to ensure that cheating is punished.

ICT can help with reducing teacher absenteeism. In Uganda, SNV Netherlands Development Organisation and the Makerere University Faculty of Computing and Information Technology developed a mobile phone application known as CU@School. As part of a pilot, every Friday head teachers were required to type in attendance figures for boys and girls and for male and female teachers, using a simple form preloaded on their mobile phones. The form was sent to a digital database, replacing paper forms and separate manual data entry. The data could be visualised in real time, using graphs, tables, and geographic maps, on the computers of district officials, who could then take action. To engage school communities, the programme also sent information to newspapers and local radio shows. The media then informed communities on what was happening in schools, highlighting examples of collaboration between parents, school management, and local officials to improve schools. Unfortunately, the programme was not extended after the pilot.cc14ae4ac465

There is optimism regarding the potential of ICTs to transform governance and promote democratic participation, including in education, but ICTs also face limitations in developing countries. Among them are limited internet access, high data costs, a dearth of ICT skills and knowledge (especially among women and minorities), and repressive governments that have been known to shut down social media and block certain websites.

Participatory budgeting

Leakage of scarce resources is a serious threat to the achievement of education outcomes. Opaque budget processes, off-budget activities (i.e., outside the formal budget), weak and poorly managed expenditure systems, and a lack of public controls provide manifold opportunities for corruption. Resources disappear because of lack of transparency in public spending on education. The quality of education suffers. Students drop out of school, and if they stay, they do not learn much given the inadequate teaching supplies and education infrastructure.

The budget is the main policy instrument of the government. However, stated policy objectives and priorities often do not find expression in annual budgets. For example, even though government policy documents may pledge adherence to the goal of universal primary education, the defence sector and large infrastructure projects often receive a disproportionate share of the budget, in part because they provide more opportunity for kickbacks and pay-offs to politicians. Distortions also occur in budget revision processes: the education budget (as part of the social sector) is usually more affected by reversals of budget allocation decisions than, for example, interest payments and programmes with a high political profile. Stated priorities in education are often the first to lose funding, whereas other budget categories, such as the defence sector and the official residences of heads of state, receive their full amount and may even request supplementary budgets.abaa6729a56e

Within the education budget, reversals and changes linked to corruption frequently affect non-wage expenditures such as learning material and school maintenance. Salaries, which represent on average 80% of the overall education budget, are less likely to be cut. While personnel are important, it is also obvious that a shortage of textbooks and paper and poor school infrastructure provide disincentives for parents to send their children to school and have a negative impact on enrolment rates.

Sometimes there are distortions between subsectors of education. Disproportionate funding may be allocated to post-primary education, which is more expensive than primary education and mainly benefits the elite. However, it is the primary education sector that ought to receive the bulk of education spending in the context of the SDGs. Also, budgets are frequently built on unrealistic estimates, either over- or underestimating tax revenue, which makes it difficult for citizen groups and civil society organisations to understand and act on budget proposals. A comprehensive budget analysis therefore needs to look at both the revenue and expenditure sides of the budget. The various distortions and manipulations of the budget can constitute acts of corruption insofar as they benefit the political and economic elite of a country at the expense of the public. Therefore, participatory budgeting is an important anti-corruption tool.

Tagged ‘next-generation democracy,’ participatory budgeting is a process of democratic deliberation and decision making in which community members decide how to allocate part of a municipal or other public budget.b5057cf9c414 According to the World Bank, factors that favour the adoption of participatory budgeting programmes include strong mayoral support, a civil society willing and able to contribute to ongoing policy debates, a generally supportive political environment that insulates participatory budgeting from legislators’ attacks, and sufficient financial resources to fund projects selected by citizens.2eca14a3d676

There is some scepticism regarding the effectiveness of participatory budgeting in reducing corruption. A study on Uganda noted the general perception that participatory budgeting is just an annual ritual exercise to comply with pressure from supranational agencies to adopt ‘new public management’ reforms, rather than a practical process that involves citizens in formulating local government budgets that meet their needs. The study argued that power relations, inadequate locally raised revenues, cultural norms and values, and citizens’ lack of knowledge, skills, and competencies in public sector financial management all served to limit the effectiveness of participatory budgeting in Uganda.692e2af8f99b

The requirements for participatory budgeting to be effective include:

- Training and technical assistance. Citizens and public officials should be trained and assisted to implement the mechanism.26c5555176ee

- Sequencing. The introduction of participatory governance practices should be carefully sequenced. An overload of reforms can occur when administrative, fiscal, and political decentralisation together with participatory budgeting are pushed at the same time.6c64c2111a53

- Decision-making power (in cases of cities and local governments). A local government must have enough discretionary funding available to be financially flexible. This allows citizens to have more decision-making power over the selection of new projects.

- A reliable mechanism to facilitate public deliberation. This might include an offline or online platform or a combination of both, for example, live-streaming of deliberation events.

- Accountability and monitoring. When the budget is finalised, it should be made public. The agency concerned should provide feedback to citizens about their proposals and the realisation of the proposed projects. Both citizens and officials need to be able to monitor the implementation of the participatory budget and the projects.8975975e44b6

Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys

PETS ‘measure the amount of funds received at each point in the chain of public service delivery, from a nation’s treasury to the classroom or health clinic where the funds are intended to be spent. Citizens are involved in monitoring a sample of schools or clinics.’bceb18b4f6bb

PETS were successfully implemented in a number of African countries during the late 1990s and early 2000s. In Uganda, a groundbreaking 1998 survey of public spending in primary education revealed that in the early 1990s, less than one-third of intended non-salary public spending had reached the schools. The bulk of the non-wage resources were retained and used by district authorities; the money disappeared without schools being able to claim their entitlement, as they were simply not informed. The study could have been kept in a drawer, but under pressure from NGOs, the Ugandan government launched a public information campaign. Monthly transfers of non-wage grants to districts were published in newspapers and broadcast on radio. Primary schools and district administrations had to post notices of all inflows of funds. The level of leakage fell significantly. Whereas in 1995, only 20 cents of each dollar spent by central government on non-wage education items actually reached schools, the figure increased to 80 cents in 2001.84ffeee8f440

Uganda’s success with PETS has been widely cited, but the experience is problematic for several reasons, and it has been difficult to replicate.3a84369d70b6 The public information campaign in Uganda was possibly one of many factors – notably including political will – that allowed the PETS to succeed in reducing leakages. An attempt to replicate PETS in Tanzania met with less success, as the government questioned the methodology used to determine that leakages were happening. A related public financial information campaign, in which financial information was publicly displayed at local government level, also had limited success because it was too general and did not specify outputs or entitlements.cdc3627cf07c

In Cambodia, a PETS implemented in 2017 tracked the flow of operational funds from the provincial treasury to schools, comparing amounts to reveal reallocations along the way and checking dates to ascertain disbursement timelines. The PETS also examined how funding amounts at school level are associated with measures of quality. It established that on average, schools did receive the full amount allocated to them, but there were significant delays in disbursement, with fund requests for the first quarter disbursed in April or May. The study did not establish reasons for the delays.f75c06cef41f

The enabling factors for PETS to succeed, as with many anti-corruption strategies, include political will. But they also include publication of clear information to stakeholders, capacity of stakeholders to access the information, capacity of stakeholders such as CSOs to undertake budget analysis, and an appropriate advocacy strategy to engage the public on issues identified by the PETS. The surveys are highly technical and require specialised skills. Moreover, with increasing digitisation of public records, financial information is now often published on open central government portals, as is the case in Uganda, where citizen access is limited by lack of access to ICTs. Finally, PETS do not offer solutions for the problems identified.93c287d99629 For all these reasons, their value is increasingly questioned, and more attention is now being focused on social audits.

Social audits

An alternative to PETS, social audit is a process of reviewing official records and determining whether state-reported expenditures reflect the actual money spent on the ground. Social audits often take the form of public hearings, where members of the community who use services can voice their concerns to public officials. Prior to the event, civic groups collect information and evidence of corruption and poor service delivery. They present this information to officials, who are given the chance to respond. In the Indian state of Andhra Pradesh, social audits have become an institutionalised feature of the government machinery.

A form of social audit is Integrity Action’s Fix-Rate, part of their community integrity-building approach.

The fix-rate focuses on measuring outputs, like the resolution of citizen complaints, or improvements in public service delivery based on problems identified by the stakeholders of this service. Inputs, in turn, are activities or policy changes, like public hearings, social audits, information portals, integrity pacts, or access to information laws. The fix-rate assesses whether these inputs empower citizens and public office holders, individually or collectively, to achieve a specific fix, and therefore an improved outcome that is in the public interest. When such fixes are achieved with some degree of consistency this can be interpreted as a signal that a policy, law or method of problem solving works and that it has the potential to become a routine practice of state-society relations.2056efaca259

Integrity Action has used the Fix-Rate to improve rubbish collection in the city of Naryn, Kyrgyzstan, education infrastructure in Timor Leste, and water supply in the town of Lunga Lunga, Kenya, among many examples.30f603260d59

The main value of social audits is that they enhance citizen voice. They can improve answerability, but have been found to be weak on enforcement. Even where there is a well- institutionalised mechanism, as in Andhra Pradesh, social audits are constrained by complex hierarchy and overlapping lines of reporting, which have made it difficult to enforce the decisions taken at social audit hearings. The experience of Andhra Pradesh reveals yet again the importance of political will and of aligning political incentives if anti-corruption reforms are to succeed.5cdb1dfc9e95 Integrity Action’s approach, which is focused on fixing problems, can add value to social audits that are overly focused on process and not on outcomes.

Accountability-promoting tools and strategies

Performance-based contracting for teachers

A practice that has proved effective is hiring teachers on short-term contracts, with performance a deciding factor in their contract renewal. A study from Kenya in 2015 found that locally hired, short-term contract, monitored teachers worked harder, presumably because they faced stronger incentives. This in turn helped improve learning outcomes. Involving parents in teacher management also helped to reduce nepotism in school recruitment.e4724ce96a86

Performance-based contracting can be used to counter teacher absenteeism. The Indian state of Rajasthan tried a version of this approach to improve teacher attendance in 60 non-formal education centres. Each teacher was given a camera with a tamper-proof date and time function, along with instructions to have one of the children photograph the teacher and other students at the beginning and end of the school day. The photographs were used to track each teacher’s attendance, which was then used to calculate his or her salary. The introduction of the programme resulted in an immediate decline in teacher absence, which fell from an average of 43% absent teachers in comparison schools to 24% in the treatment schools.bb61fb8e1afb Nevertheless, surveillance in the classroom must be used with care. Teachers may feel that this practice demonstrates a lack of trust. In addition, when surveillance is used against students, it may violate students’ right to privacy and can have negative effects on learning.1dd44f798b03

Teacher codes of conduct

Clear codes of conduct for school staff are needed to ensure certain standards of professional ethics that are not directly covered by law. Codes must describe what constitutes corrupt practice, especially when proper professional conduct differs from widely accepted social norms. For example, gift giving may be appropriate outside the classroom, but not as a requisite for receiving education. Codes of conduct can regulate the content and duration of instruction, the allocation of funds to schools, the granting of social incentives, the recruitment and management of staff, the rights and duties of teachers, the issuance of diplomas, and interactions between students and teachers.3e233d0faefc

To be effective, codes must be publicly known, respected in government and at the top levels of society, and consistently enforced. Non-compliance with codes should result in appropriate sanctions, ranging from reprimands to suspension or cancellation of teaching licences.00845a369bf6 Professional associations or unions can help develop such codes or provide models, such as the Declaration on Professional Ethics developed in 2001 by Education International, a global federation of teachers’ trade unions.91cf02254977

While codes of conduct are important, it is crucial to ensure that corrupt behaviour amounting to criminal conduct – such as theft, misuse of funds, or sexual abuse – is consistently dealt with by the courts to maintain respect for the rule of law.

Community monitoring programmes

Parent-teacher associations and community groups can play a vital role in improving school management. Research from Uganda revealed that community monitoring improved test scores and pupil and teacher attendance at low cost, but only when communities could choose the criteria by which they judged school performance. School Management Committees (SMCs) were trained on how to use scorecards to monitor schools. In one of the two models studied, the scorecards were designed by central organisations including NGOs and education authorities, while in the other they were designed by SMC participants themselves. A hundred schools across Uganda were assigned randomly to one of these two community monitoring programmes, or to a control group where no additional monitoring was implemented. Monitoring based on criteria assigned centrally did not lead to any improvements. This shows the importance of participation and coordination between parents and teachers for improving schools.93194d96fdfc

Community monitoring can also be used to track textbook and other education supply chains. The Philippines Textbook Count initiative mentioned above involved civil society monitoring of the procurement process, while volunteers from the Boy Scouts monitored up to 85% of 7,000 textbook delivery points. This helped ensure that textbooks reached schools, reducing costs by up to two-thirds and procurement time by half.f96ef917763b

Complaints mechanisms

Complaints mechanisms play an important role in detecting corruption. Such mechanisms can be internal, for example, within an educational institution or department, or external, located in another institution such as an ombudsman.

There is some scepticism about their effectiveness because there is often no follow-up. Many complaints mechanisms are poorly designed, with no requirement to maintain written records of complaints, nor any obligation to act on them or provide written feedback.493692f845da It is not enough to set up a suggestion box or designate an email address or hotline. According to the good practice principles set forth by Wood (2011), complaints mechanisms should be:

Legitimate: Clear, transparent, and independent governance structures must be in place to ensure that there is no bias or interference in the process.

Accessible: A mechanism must be publicised and provide adequate assistance to those who wish to access it, including specific groups such as children, women, and disabled people. Accessibility needs to take into consideration language, literacy, awareness, finance, distance, and fear of reprisal.

Predictable: A mechanism must provide a clear and known procedure, with a specified time frame for each stage, clarity on the types of processes and outcomes the mechanism can and cannot offer, and a way to monitor the implementation of outcomes.

Equitable: Stakeholders must have reasonable access to the sources of information, advice, and expertise they need to engage in the process on fair and equitable terms.

Rights-compatible: A mechanism’s outcomes and remedies must accord with internationally recognised human rights standards.

Transparent: A mechanism must provide sufficient transparency of process and outcome, and transparency should wherever possible be assumed as the default.9778b577e109

Salary reform

Teachers’ notoriously poor pay in many developing countries may be one of the factors that creates incentives for corruption in the education sector. Reports of teachers striking over pay are common.8a6004d9a07b However, the relationship between pay and corruption in the education sector needs to be seen in the context of broader civil service pay reform. This is because public salaries in the education sector are governed by rigid civil service codes that make it legally and politically difficult to change salaries for teachers and administrators without changing the salaries of everyone else in the public service as well.

Civil service reform has been a component of structural adjustment programmes in the last couple of decades. Reform of civil service pay is vital for building capacity and improving the delivery of public goods and services. Low salaries in the public service may attract incompetent or even dishonest applicants, which results in an inefficient, non-transparent, and corrupt administration. When government positions are paid less than other comparable jobs, the moral costs of corruption are reduced. Poorly paid public officials might find it less reprehensible to accept bribes than officials who receive a fair salary. However, some researchers see salary increases as a necessary but insufficient condition for reducing corruption. According to Rafael Di Tella, raising wages is a means of addressing corruption primarily at the very low levels of a bureaucracy. Once subsistence levels are guaranteed, higher wages will deter corruption only if officials are audited.6a44b6e14d90