Main points

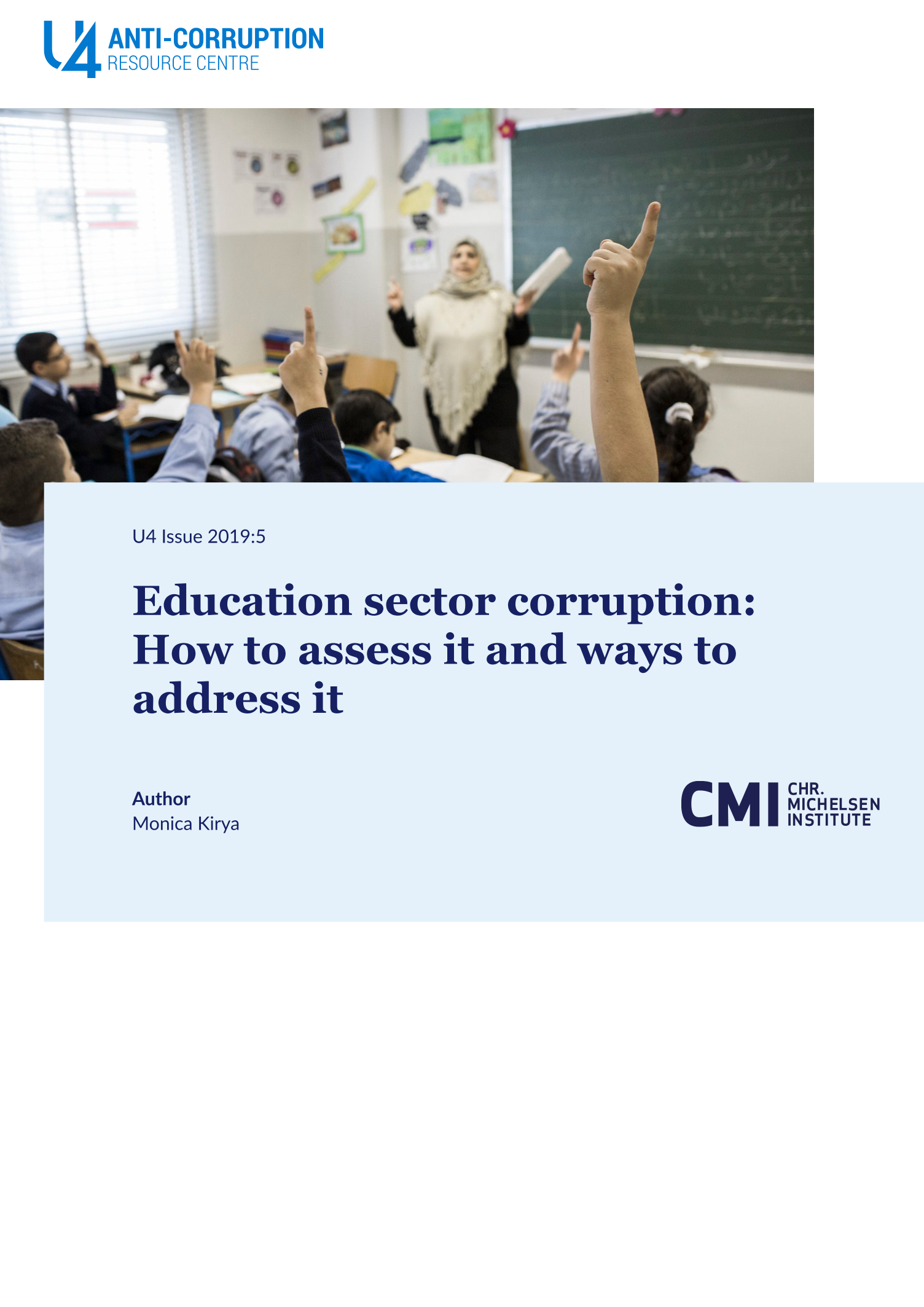

- Corruption in education threatens the well-being of society because it erodes social trust and worsens inequality. It sabotages development by undermining the formation of educated, competent, and ethical individuals for future leadership and the labour force.

- Corruption in primary and secondary education affects policy making and planning, school management and procurement, and teacher conduct. Examples include cheating and other academic violations; bribery, nepotism, and favouritism in school admissions, teacher appointments, and licensing of education facilities; bid-rigging in the procurement of textbooks and school supplies; diversion of funds and equipment; teacher absenteeism; and exploitation of schoolchildren for sex or unpaid labour.

- Corruption contributes to poor education outcomes. Diversion of school funds robs schools of resources, while nepotism and favouritism can put unqualified teachers in classrooms. Bid-rigging may result in textbooks and supplies of inferior quality. When families must pay bribes for services, this puts poor students at a disadvantage and reduces equal access to education. Teachers’ demands for sex may cause girl students to drop out of school.

- Features of a country’s education system and political economy often create incentives for corruption. Sector-specific approaches to anti-corruption reform enable stakeholders to target specific instances of corrupt behaviour and the incentives underlying them.

- Assessing corruption risks and designing mitigation strategies must be a locally owned and locally led process. Context mapping, using tools such as political economy analysis, power and influence analysis, and the Integrity of Education Systems (INTES) approach, can help practitioners spot corruption problems and identify likely allies or opponents of reform.

- Stakeholders should engage in dialogue and consensus building to agree on which problems to prioritise, taking into account their urgency and the political feasibility of different anti-corruption strategies.

- Anti-corruption strategies in education can make use of (a) transparency-promoting tools, such as ICTs, participatory budgeting, Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys, and social audits, and (b) accountability-promoting tools, such as performance-based contracting, teacher codes of conduct, community monitoring, complaints mechanisms, salary reform, procurement reform, and public financial management reforms.

- Monitoring, evaluation, and learning should be built into anti-corruption reforms so that measures can adapt to changing contextual realities.

- Including values, integrity, and anti-corruption education in school curricula is a long-term strategy mandated by the United Nations Convention Against Corruption.

- Bilateral development agencies can support participatory sector planning processes that include corruption risks as part of education sector situation analyses. They can support technical assistance for political economy assessments, systems analysis, and other approaches to assessing corruption risks. Assessments should build upon synergies with gender analysis and human rights–based approaches to ensure that anti-corruption measures address aspects of inequity and vulnerability.