What we mean by corruption risk management

Corruption risk management (CRM) is a specific set of procedures and requirements to detect, assess, and mitigate corruption risks within an organisation. It is an important part of implementing anti-corruption policy. CRM holds a strategic dimension, as it implies backing from the top leadership and is integral to all decisions and activities of an organisation, from the institutional level to projects and programmes. What risks are we referring to?

Corruption risks relate to all kinds of risks inherent in and organisation’s activities, e.g:

- Fiduciary risks (because of fraud or theft).

- Legal risks (when violating laws).

- Safety risks (increasing the likelihood of accidents or illness).

- Operational risks (viability to achieve objectives).

- Information risks (hiding or withholding important data).

- Reputational risks

For example, favouritism within recruitment is a corruption risk for human resources management, and could be a reputational and operational risk for the organisation and its activities.

As with any other organisation, development aid agencies encounter corruption risks within procurement (eg bid rigging, manipulated tender specifications), human resources (eg conflict of interest, recruitment biases), as well as project financial and asset management. Risks also exist within implementing channels or external project partners, which can be public or private bodies, multi-donor trust funds, or NGOs. Accordingly, CRM helps to manage those risks, throughout the organisation.

At the institutional level, CRM is helpful in coordinating integrity and compliance policies, in defining rules and procedures, and in determining proper control mechanisms. CRM can help aid agencies to assess and mitigate corruption risks at all levels.

The rationale for CRM is not a cost/benefit analysis, but an investment to avoid the identified corruption risks from being able to harm the organisation and its development programmes. Mitigation benefits are measured in terms of the likely gains when leakages in projects are reduced, as well as indirect benefits in terms of strengthened control mechanisms and a lower level of corruption.

Corruption risk management in practice

All organisations can apply CRM techniques – scaled to their own resources and capacities. Yet, development agencies or their partners may lack resources and anti-corruption experts; not all organisations can develop an empowered and well-defined anti-corruption department. How is it possible to streamline the use of CRM?

CRM at the policy and strategic level – examples

When development aid agencies develop CRM policies, they demonstrate a commitment to ethics, integrity, and responsible use of tax money. This is particularly true post Covid-19 with scarce resources and the need to optimise funding usage. At the same time, each CRM strategy is unique and tailored the organisation.

United Kingdom

The 2017–2022 UK Anti-Corruption Strategy considers CRM as a way to enhance public confidence in domestic and international institutions, and to increase prosperity at home and abroad.

UK’s Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) manages risks at three levels: the corporate, operational unit, and intervention level. It operates with two different risk registers: corporate and operational.

FCDO deploys CRM by country – with explicit anti-corruption strategies for countries with high risk of corruption. One example is the 2015 anti-corruption and counter fraud strategy for South Africa. By collating information on corruption risks from different levels, managers become aware of potential problems and can use adequate mitigation mechanisms that are tailored to the local level.

France

In its 2020 general policy on anti-corruption, the French cooperation aid agency (AFD) also relates CRM to spending public money wisely. In addition, it uses CRM to optimise funding to partners in ways that best serve the purpose. The policy identifies three key moments to check corruption risks: during project instruction, contract signing, and project execution.

Germany

German Development Cooperation’s (GIZ) anti-corruption and integrity policy emphasises how anti-corruption efforts relate to promoting integrity and good governance in partner countries.

Canada

Global Affairs Canada has a unique Risk Management Advisory Group that manages corruption risks, avoids duplicating efforts, and facilitates knowledge sharing.

Defining a CRM strategy

It can be challenging to define a CRM strategy. A first step is to understand how the organisation’s structure, size, and activities go along with its attitude towards CRM. Key factors to consider are stakeholders’ views and concerns, governance structure, legal environment, partners, and sector distinctions.

For instance, stakeholders may define a risk appetite, which determines the way the organisation assesses risks and carry out mitigation measures. (See the U4 blog Zero tolerance for corruption in international aid on the distinction between strict and a scaled approach.) A tough anti-corruption stance at the policy- or strategic level without clarity on how to apply it in practice can cause misinterpretations.

Another key step in defining a CRM strategy is to compile a register of corruption risks. It is thanks to this corruption risks register and the initial analysis on organisation’s specificities that will be determined the CRM governance structure and resource allocation. Not all development aid agencies have a defined anti-corruption strategy and may refer to several documents to manage corruption risks. See also this separate list with examples of reference documents that development agencies use for CRM guidance.

CRM at the institutional level

Fraud and corruption control is often seen as a ‘corporate’ responsibility, as any wrongdoing can be harmful at the institutional level. A good example is the Danish development cooperation’s risk management guidelines, which capture risks at the contextual, programmatic, and institutional levels. The guidelines emphasise the need to consider ‘operational security or reputational risk parameters’ for the institutional level.

Accordingly, it is important for central management to set rules and procedures to be followed throughout the organisation, and for how CRM will be structured. For CRM to work, there needs to be documented information in place – including internal and external communications on the anti-bribery policy and strategy. For example, in 2020, FCDO published smart rules – an operating framework for better programme delivery. It defines oversight functions and risk management governance.

Large development cooperation agencies can develop synergies between, for instance, compliance departments, audit offices, and CRM experts. This can help to streamline corruption risk management across existing monitoring and evaluation (M&E) processes. Strengthening interactions between control and programme functions can help integrate anti-corruption tools along delivery chains.

For example, the Danish foreign affairs ministry's Technical Quality Support Department has developed peer groups with anti-corruption experts and financial and development specialists. Those peer groups are helpful to prepare and follow project appraisal internally. Moreover, anti-corruption focal points are designated during implementation phase to work better with partners.

Development and humanitarian organisations should aim for a thorough project risk identification and mitigation process that is also clear on how to report and respond to corruption incidents. For example, CARE International has developed a Policy on fraud and corruption that outlines an internal escalation process to ensure appropriate management, awareness, and expeditious handling. Here, each contract holder has to ensure proper implementation of CRM measures, report regularly, and guide and train its staff, sub-grantees, and partners on the policy.

CRM at the programme and project level

At the programme and project levels, anti-corruption efforts should not be an expensive burden that hampers activities, but rather a proportional measure to help stakeholders manage operations and risks, internally and externally.

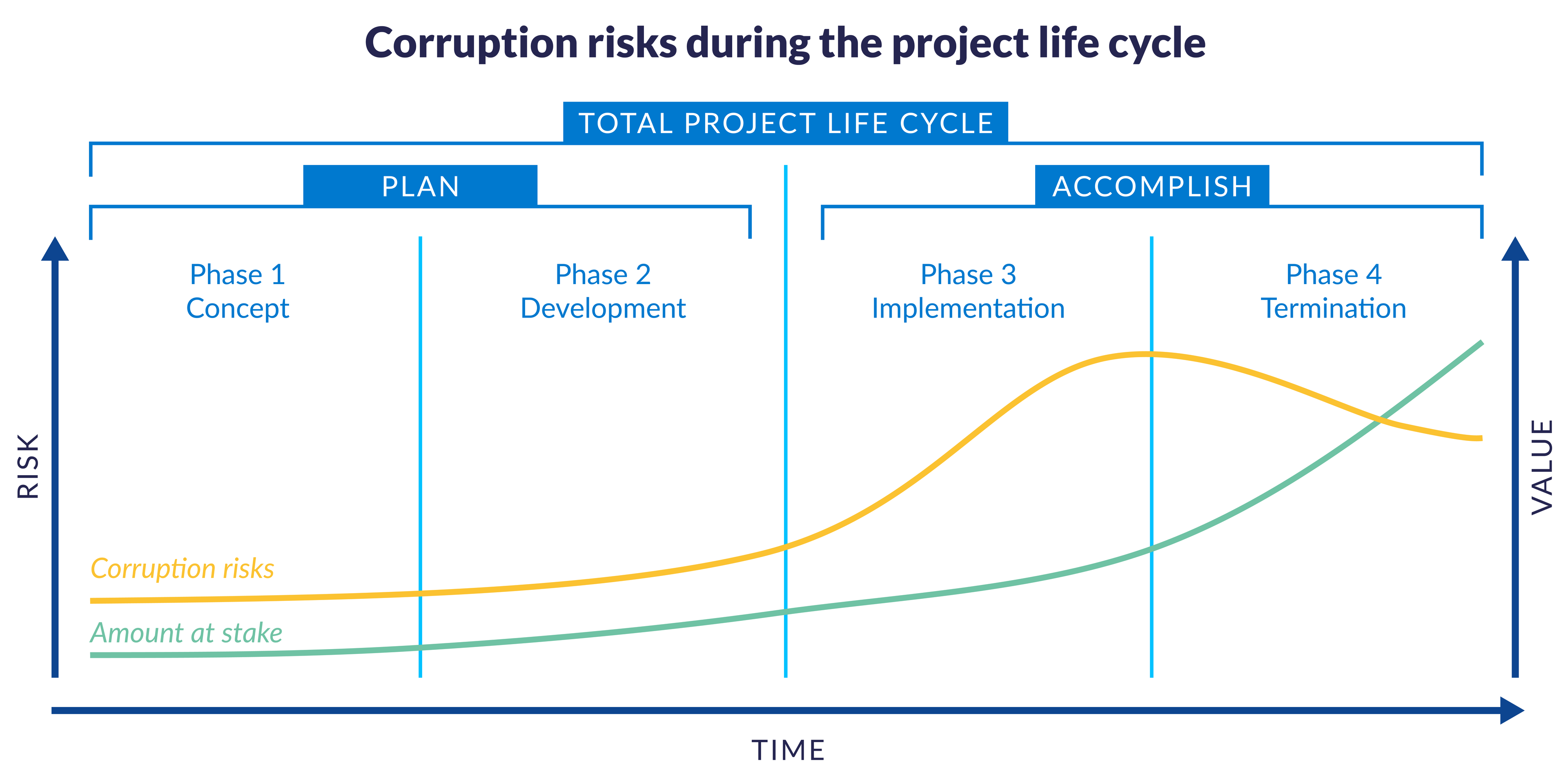

Figure 1 below shows the different project phases – inception, development, implementation, termination – and their respective corruption risks. The yellow line shows that corruption risks already exist in the planning phase, rise during the implementation phase – when large sums of money can change hands – and diminish during the termination phase.

Figure 1.

Corruption risks exist in all project phases. They peak during the implementation phase when large sums of money can change hands.

Credit: Adapted from Project and program risk management (Wideman 1992) by-nc-nd

Phase 1 – Concept

Corruption risks in the concept phase relate to decisions that can have a direct impact on stakeholders, target definitions, and intervention areas. Partners’ interests and their eagerness to see the project develop can influence scoping missions. When project appraisals are outsourced to consultants, it increases risks for fraudulent assessments, bribery undermining merit-based procedures, high-cost projects being promoted, etc. Political manoeuvres (for instance, to benefit certain constituencies), gifts and kickbacks, and conflicts of interest are other corruption risks that relate to this phase.

Role of CRM

The concept phase is crucial for the initial identification and assessment of corruption risks, including political economy analysis to consider development aid programme impact.

Responsibilities

For small organisations, it is mainly the middle management that is involved in risk definition. In larger organisations, anti-corruption experts are part of the process, at least as a back-up.

Best practice

For risk assessment and risk mitigation, the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) provides TRAC – an IT system that includes requirements for assessing risks, evaluating their potential impacts, and establishing mitigation approaches. Global Affairs Canada employs fiduciary risk assessment tools as an integral part of development agencies’ safeguards.

Phase 2 – Development

The development phase involves corruption risks when, for example, choices such as who will (or will not) be the beneficiaries and partners are specified in the terms of reference. Other risks include budget manipulation, vague criteria, and asymmetrical information. Moreover, the process around choosing partners is vulnerable to unethical practices: bribery, clientelism, conflicts of interest, etc.

Role of CRM

It is crucial to establish control and M&E procedures, as these measures may have a huge impact on future corruption risks. Pay particular attention to funding modalities. They influence the organisation’s capacity to control and mitigate corruption risks. It is hard to say if one funding modality is riskier than another – this depends on development aid agencies’ capacity to exert control and implement safeguards.

Responsibilities

The project manager is likely to assume overall responsibility of the project at the beginning of this phase. The project manager will rely on existing corruption risk assessments (such as country-level and sector-level assessments).

The core project team conducts comprehensive, project-specific risk identification and assessment. This is a way to distribute responsibilities and take ownership of mitigation measures and strategies. The risk analysis findings should clarify precautionary measures and inform the project’s design and governance structure.

Best practice

Best practice varies according to funding modalities. For budget support, specific development agency safeguards exist. Explicit control measures can be put in place when relying on external partners. For example, the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade have developed a fraud control toolkit for funding recipients.

Phase 3 – Implementation

Activities such as recruitment and procurement take place at this stage – leading to a peak in disbursements. This is why there is a larger risk that involved actors engage in a variety of corrupt activities. These risks may be fiduciary (fraud, theft), reputational, operational, legal- and compliance-related, and more. For example, asset management, licences and access to services, per diems, procurements, and the selection of participants for training are common sources of corruption risks.

Role of CRM

All organisations – big or small – should carefully allocate management and oversight responsibilities to ensure that tasks and outputs are properly monitored and supervised. The organisation should conduct a mid-term evaluation and audits – of performance, finances, compliance, etc. – carrying out adequate controls.

There is no ‘one size fits all’ solution since each project has its unique characteristics – eg budget size and structure.

Responsibilities

Larger organisations should have an anti-corruption team to support handling whistleblowing and fraud cases, and to help resolve ethical dilemmas: conflicts of interest, contract violations, etc.

Some also have specialised, central units that handle procurement.

Smaller organisations can engage skilled staff to perform first-party audits, or outsource the task to certified auditors.

Best practice

Sida’s audit manual tackles corruption risks, while their audit guide does so for grants to NGOs.

ISO 9001 provides guidelines for internal audits. For whistleblowing, Globaleaks software provides a good solution that is free, open source, and secure. See also the U4 topic page on procurement with a basic guide and examples of best practice.

Phase 4 – Termination

The termination phase is not immune to corruption risks. With the perceived need (or urge) to disburse the remaining funds, malpractices may occur. End-of-contract activities can increase exposure to pressures and opportunistic behaviour. With the closing of accounts, breaches may be exposed, such as fraudulent document results, collusion between programme managers and evaluators or auditors, undermined evaluations, etc.

Role of CRM

Organisations should include CRM in programme- and project control operations and evaluations. M&E insights should be used to improve the CRM framework’s quality.

Responsibilities

For larger organisations, anti-corruption experts may help in project evaluation. For all organisations, dedicated services should control financial aspects. Evaluators should also check how relevant and effective the CRM framework has been.

Best practice

Financialaudits focus on compliance with applicable statutes and regulations. The Financial and Compliance audit Manual from the European Court of Auditors is a comprehensive guide for such audits.

The corruption risk management cycle

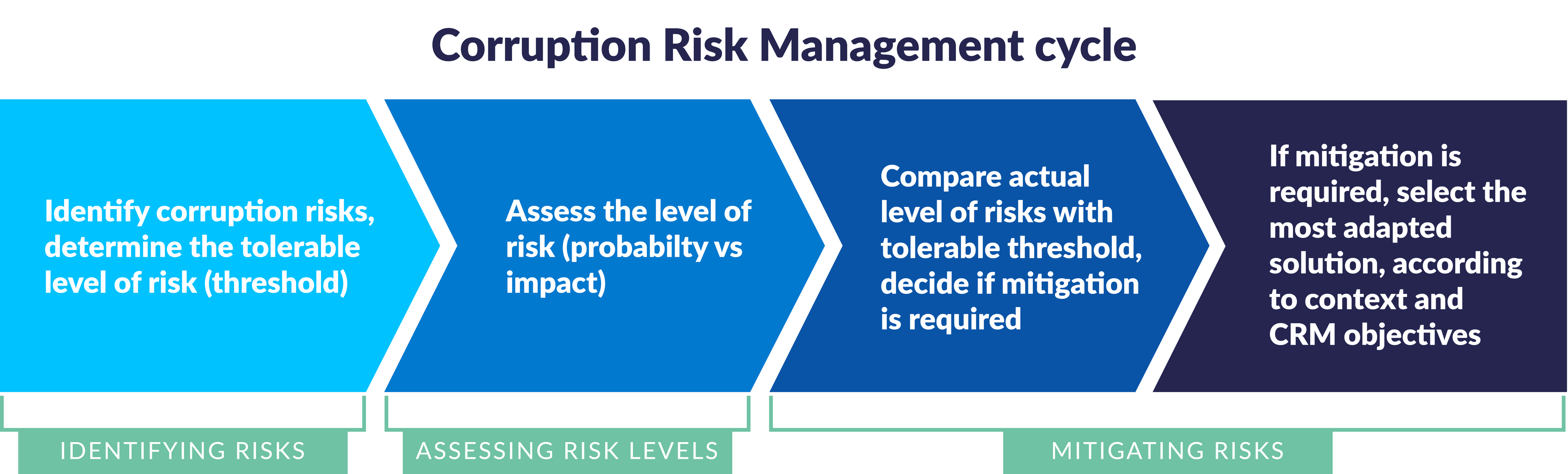

Key steps to establish a full corruption risk management cycle:

- Risk identification

- Risk assessment

- Risk mitigation

Figure 2.

Below are brief descriptions of scope, risk owner (the person in charge of implementing recommendations) and operational tools for each step in the CRM cycle.

Step 1 – Identifying risks

Scope

Risk identification involves an inventory of all corruption risks that could threaten project delivery. It can be part of a more general risk management system. The organisation establishes a risk register and identifies the source of any risks, their causes and effects, and type – institutional, programmatic, or contextual.

In the inventory, one has to distinguish between minor and major risks – depending on how they can potentially affect programme outcomes. This helps establish the risk thresholds and future mitigation targets.

Defining risk thresholds can be difficult (especially with a ‘zero tolerance for corruption’ policy). This involves distinguishing acceptable risks – low impact and probability – from those that should generate a necessary mitigation reaction. Organisations should carry out an initial risk identification at the appraisal or development stage, and later review the register regularly as situations may evolve.

Risk owner

Programme managers should identify relevant risks. For example, international red flags developed by the World Bank, the OECD, or the International Chamber of Commerce show where to look for corruption risks in procurement. Previous country and sector assessments from project appraisals should inform their analysis. When there is an anti-corruption team within the organisation, it should provide support to define specific risks.

Tools

We strongly recommend looking at the U4 Guide to using corruption measurements and analysis tools for development programming. Approaches can rely on quantitative or qualitative data, or a mix of both. Document reviews, brainstorming, participatory methodologies (such as interviews with employees or stakeholders), and horizon scanning are all valid tools to identify risks.

For example, USAID’s rapid appraisal methodology for public financial management (p.8) helps to understand partners’ capacities and environment. The Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT)’s risk identification approach (p.7) defines events that may occur, their causes, and their potential impact.

Step 2 – Assessing risk levels

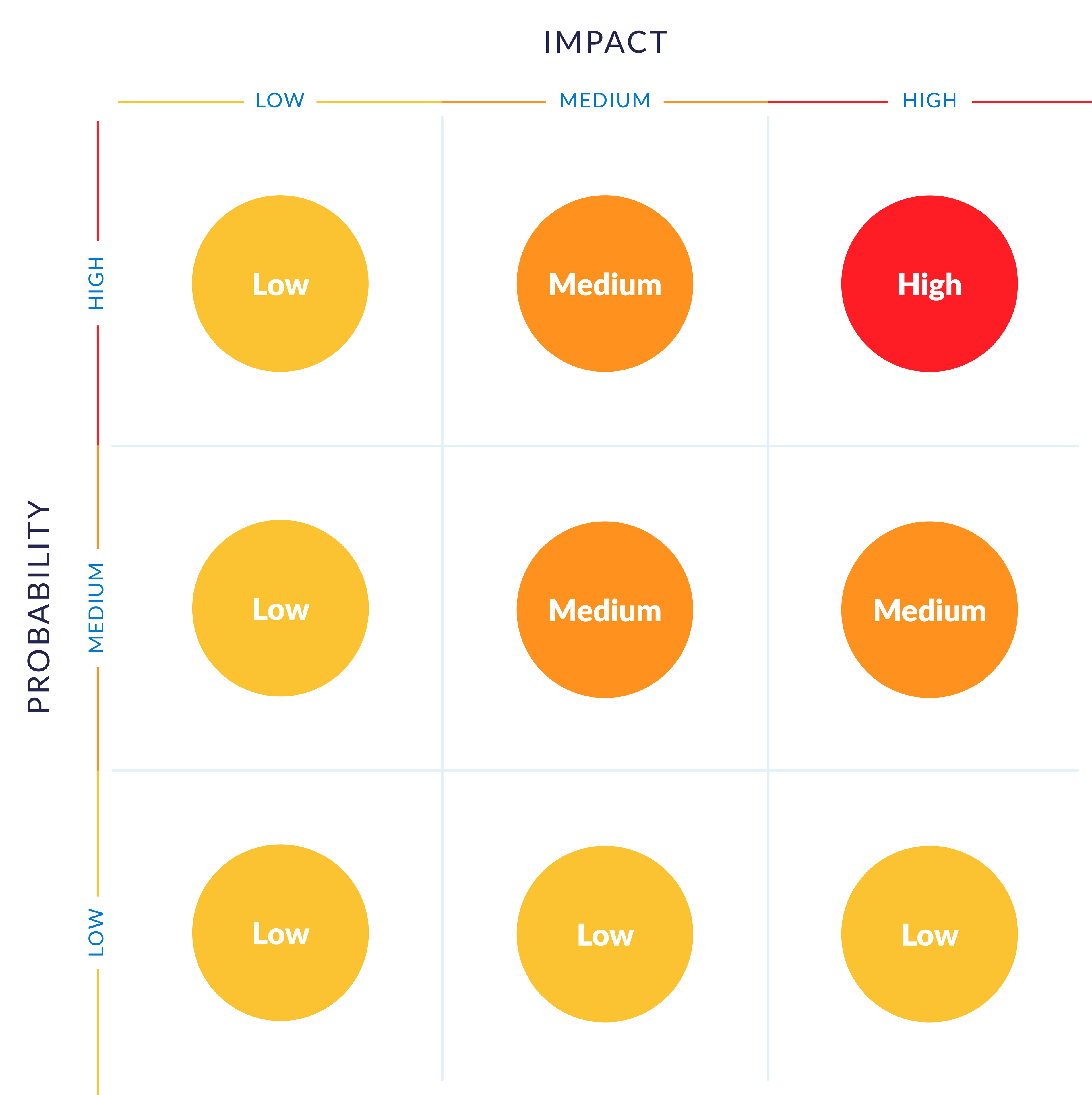

Organisations assess risk levels by evaluating the magnitude of an identified risk and then determining the level of response. This includes looking at whether the event is unlikely, likely, or very likely to happen – corresponding to a low, medium, or high probability.

At the same time, one has to estimate the potential impact of that occurrence for the organisation and its activities – distinguishing between a low, medium, or high impact.

For example, a development programme may assist custom authorities that potentially face bribe requests. The likelihood that this will happen is high in a country with a low Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA)score. The impact would be substantial in terms of, for example, a damaged reputation. However, the impact may be low considering overall project results, so it could be assessed as a medium risk. A medium risk will then require proportionate mitigation measures.

Figure 3.

Using a heat map when presenting the risk assessment results can help to pinpoint priority areas.

Organisations can determine how likely a risk is to become reality – or probability – by studying various aspects, such as:

- Previous occurrences in the country, sector, or similar programmes.

- Existing databases on corruption occurrences.

- Reviewing partners’ processes.

- Understanding local context, etc.

For example, the Maritime Anti-Corruption Network registers all incidents reported in specific places, and the Water Integrity Scan assesses corruption risks in the water sector from a users perspective. Such appraisals may inform development agencies’ own risk assessments.

To estimate the potential impact if a risk becomes reality, organisations must consider the likely financial, legal, regulatory (capacity of a programme to operate), operational, and reputational damage. It can be useful to study how past incidents in the country, sector, or similar programmes have affected operations and employees.

Assessing corruption risks can sometimes be difficult, as corruption is a complex issue. Moreover, risk perceptions vary from one context to another. For example, favouritism in recruitment represents a corruption risk for human resources management, yet the degree of social acceptability varies. The risk evaluation may then be different from one context to another.

Risk owner

Project or programme managers can assess corruption risks potentially affecting their project or programme, and regularly review the risk register. Country directors and anti-corruption experts can help to assess internal and external context.

Tools

Useful methods for risk assessment include brainstorming, risk-mapping, probability analysis, participative methodologies, and decision tree analysis (decisions based on expected outcomes and probabilities). Risk registers can be simple and effective, such as the DFID/FCDO risk management matrix.

Step 3 – Mitigating risks

There are different ways to mitigate risks:

- Risk treatment

Actions or procedures that help avoid or reduce the probability of a occurring and harming the organisation and its activities. - Risk tolerance

Significant residual risks exist despite prevention and mitigation actions, and managers keep track of those risks in case of escalation. Organisations should determine their tolerance level to inform future decisions. - Risk transfer

When the risk is present but organisation cannot take it on, but rather rely on another entity to assume that responsibility. Such entities may be an insurance company or a third party with expertise to mitigate the risk. - Risk termination

The organisation chooses a different path of action because the risk is too high and cannot be managed. This is an option when corruption risks cannot be transferred, treated or tolerated by existing anti-corruption controls.

Organisations should identify recommendations, who is the risk owner, and necessary resources for all mitigation measures. Resources may include political support, infrastructure, human resources, rules and guidelines, information, and monitoring and reporting measures.

Organisations should also consider risk appetite – the attitude towards corruption risk – in their risk responses. This will depend on the organisations’ interest or intended activity outcomes.

Risk owner

Mitigation is often a multi-stakeholder and cross-functional effort, ascontrols, monitoring activities, and other mitigation recommendations require coordination across various departments.The procurement department, finance officers, anti-corruption team, country director, and/or the sectoral or regional director may be involved, depending on cases and the level of responsibilities.

Mitigation also depends on whether it is a preventative or an investigative control. In case of an investigative control, anti-corruption and fraud experts may be much more involved, whereas preventative controls is a concern for programme managers or compliance and training officers.

Tools

All mitigating actions must be proportionate. This applies to audits, evaluations, due diligence, financial and non-financial controls as well as service delivery surveys. Such actions require resources, and can therefore affect the capacity to reach objectives. They can even have unintended consequences, such as reputation damage.

Yet, CRM and mitigation is fundamental and shall safeguard the organisation’s interests and its possibility to succeed. GIZ’s Guidance (p.121) shows list of good mitigation examples during programme planning and implementation.

Implementing a CRM system within development aid agencies

This section is inspired by ISO standard 37001, a standard that aims to help build an anti-bribery management system. See also the 2021 U4 Issue Getting the most out of the ISO 37001 standard on how development aid agencies can benchmark and add value in anti-corruption activities.

Planning and support activities

Each organisation has to consider its distinct context including stakeholders’ needs and expectations and CRM requirements when planning their implementation. For good planning, consider the following:

- Objectives

- Actions

- Resource needs

- Responsibility levels

- Reporting and evaluating results

- Sanctions and penalties

Employers should ensure that staff throughout the organisation know its anti-corruption policies and enable them to comply with CRM guidelines and procedures. This requires updated and appropriate anti-corruption awareness and training programmes for all staff – covering what constitutes corruption and risks, the CRM system, etc.

For example, Sida offers regular training on corruption risks, detection, and investigation. When necessary, training should be opened up to partners and stakeholders. In the preparation and support phase, it can be useful to simulate emergencies, define action plans, and prepare materials for alerts, warnings, etc.

Corruption should not be treated as ‘taboo’ within the development sector. Discussing corruption issues is important for value transfers: transparency rather than secrecy, and responsibility rather than indifference. Openness is also a way to show that corruption is not related only to the audit department, but to programme quality, accountability, and other agencies’ commitments.

On the other side, powerful deterrents should be put in place for all staff. A disciplinary system should ensure compliance with the CRM system. Communicating efficiently on sanctions helps to increase employees’ awareness, keeping those sanctions as a deterrent. For example DFID/FCDO defined a policy for gifts and conflicts of interest, with clear consequences for civil servants who disrespect the policy.

Organisations should review incentivising elements and conduct due diligence for new employees in all positions exposed to a medium/high corruption risk. An anti-corruption compliance declaration is recommended for employees at risk, as well as top management and the governing body.

The organisation has to align its internal and external communications with the anti-corruption management system – considering how, when, and what should be communicated, and to whom if, for instance, corruption is revealed. Moreover, the organisation should communicate the anti-corruption policy well to persons among staff and partners who may face corruption risks. Responsible staff or departments have to control this information regularly – making sure it is suitable and available.

Operational aspects

Processes should be in place to meet the CRM requirements, along with corresponding control mechanisms. All entities under the control of the development aid agency (such as country programmes or development projects) should respect these CRM processes.

For partners and entities outside the organisation’s control, which face more than a low corruption risk, the organisation should ensure that their anti-corruption controls are adequate. For example, DFID/FCDO enacted a supply partner code of conduct, with specific requirements on anti-corruption and due diligence.

The ‘Swedish model’ shows an alternative way: Sida pays instalments as long as controls and evaluations from controllers, quality assurance system managers, and project committees remain positive.

If partners’ controls are not adequate, the organisation should require that they put in place anti-corruption controls for activities related to the organisation. When this is not possible, the organisation should report the situation in its corruption risk evaluation and determine how to manage the risk.

Organisations should implement specific procedures for raising concerns – allowing anonymous reporting. These procedures should ensure confidentiality, protect whistleblowers, encourage reporting in good faith, and enable personnel to get help when involved in a situation of bribery. All personnel should be aware of the reporting procedures and how to use them. Each employee should also be aware of their rights and protections.

Finally, preparing for compliance breaches is an essential component of a CRM strategy. This is for when a violation of the CRM requirements and/or the anti-bribery policy is reasonably suspected, reported, or detected. Procedures should ensure that investigators work effectively – with cooperation from relevant staff. Investigators should identify urgency and safety needs, the causes and impact of the breach, as well as next required steps. Some criteria should apply during investigations in terms of jurisdiction, materiality, credibility, context, and confidentiality of investigations and their results.

The role of CRM for integrity and corruption risk prevention

CRM can be part of a more comprehensive approach that links anti-corruption tools directly to compliance, integrity, and good governance. For example, the GIZ 2020 anti-corruption policy relates the CRM system to a ‘corporate culture of anti-corruption’. Similarly, an OECD recommendation places risk management alongside internal ethics and at the centre of an integrity system. Accordingly, CRM can be integrated as a powerful driver for an integrity culture.

Finally – as CRM processes require regular monitoring and improvement – monitoring activities can both help prevent corruption risks and detect non-compliance. Organisations can use insights from investigations into compliance failures to inform training programmes. Doing so can encourage a more proactive leadership and organisational resilience to achieve a strong compliance culture. Similarly, reporting mechanisms can be used to communicate ethical concerns and improve integrity within the organisation.

----------

U4 online course on corruption risk management

Check out upcoming dates for the 2-week, expert-led course for U4 partner staff and any of their partners who they wish to nominate. The course covers the basic principles of corruption risk management and insights on how to identify and act on corruption risks in your work.

----------

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)