Query

Please provide an overview of the negative effects of corruption on young people and their role in preventing corruption.

Caveat

While youth can generally be understood as the “period of life in-between childhood and adulthood” (Henze 2015), there is no universal consensus on which age group should be considered youth.

The United Nations “defines those persons between the ages of 15 and 24 as youth” but notes that Member States may employ different definitions. In some countries, children from the point of birth may be categorised as youth while in others the definition applies to persons as old as 35.

This Helpdesk paper documents evidence from a range of jurisdictions with different brackets for what is considered youth and thus eschews a single definition; nevertheless, the primary focus taken is on young adults rather than young children.

The negative effects of corruption on youth

The literature has only recently begun to explore the differentiated impacts of corruption on different age groups within the general population (Transparency International and Equal Rights Trust 2021), and this holds true for youth. It is understood widely that young people are often marginalised in society because of the existence of power asymmetries vis-à-vis older groups as well as their typically lower access to resources (Bullock and Jenkins 2020). However, less is known about whether and how corruption contributes to the marginalisation of young people.

This section explores different strands of literature – including survey-based studies and more theoretical work – that are beginning to shed light on the negative impacts of corruption shouldered by young people.

Level of exposure to corruption

Young people make up a substantial proportion of the general population – and in some countries a majority – meaning they are liable to be exposed to the same everyday forms of corruption faced by others (Kahuthia Murimi 2018).

However, some evidence suggests that young people may be more exposed to the occurrence of corruption relative to the general population. For example, the results of Transparency International’s 2019 Global Corruption Barometer survey found that respondents aged 18 to 34 in Caribbean countries were more than twice as likely to have paid a bribe than people aged 55 or over (Duri 2020). Similarly, results from the Global Corruption Barometer Asia 2020 found young people aged 18 to 34 were considerably more likely than people aged 55 or over to have paid a bribe or used personal connections to obtain a benefit (Transparency International 2021).

In several countries, youth-based surveys have been carried out which assess young people’ experience of corruption. However, these do not always set out to control findings against other age groups. In Kenya, 46% of respondents to a 2017 survey administered to young people in the country said they had paid a bribe to government officials; 80.3% of these cases related to services of particular relevance to young people, such as obtaining national identification documents, seeking medical assistance or applying for third-level education (Institute of Economic Affairs, Kenya 2021). Similarly, in Chile, 52.1% of respondents to a survey administered to young people between 18 and 29 years old said that corruption affects them significantly (Chile Transparente 2023).

Attitudes to corruption

Beyond assessing how frequently young people encounter corruption, studies measuring the general attitude of young people towards corruption can enrich the understanding of its negative impacts on youth. Research generally finds that young people hold disapproving attitudes towards corruption and perceive it to have negative impacts, though the degree of this ‘intolerance’ varies between countries. Furthermore, studies often find that a small (but in some countries significant) subsection of youth typically consider corrupt practices to be acceptable.

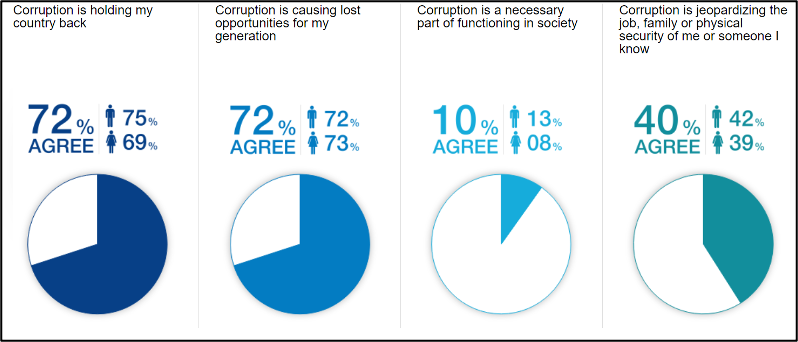

In 2014, the MY World 2014 survey collected responses from 1,089 people between the ages of 18 and 34 from 102 countries (World Economic Forum 2015). Their responses reveal a general recognition by young people of corruption’s negative impacts on themselves but also their wider surroundings (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: levels of agreement with select corruption-related statements under the 2014 MY World survey

World Economic Forum 2015.

The survey is one of the few examples of a youth-centred cross-national surveys that allows for comparison between regions. For example, in terms of agreement with the statement “corruption is holding my country back”, while the average level was 72%, this rose to 90% for respondents from sub-Saharan Africa. Notably fewer (61.6%) of respondents living in what were classified as advanced economies expressed this view.

While young people might generally express opposition to corruption, other evidence indicates some may also treat it as routine or normalised. A study from Torgler et al. (2004) relying on World Values Survey data found that respondents in the 18 to 30 age group were more likely to believe corruption was justifiable than counterparts in the 30 to 65 plus group.

Authorities in Latvia carried out surveys of attitudes towards corruption in 2021, 2022 and 2023 and found for each year, respondents aged between 18 and 29 were the group most willing to use “informal solutions” (such as relying on personal contacts) to solve issues they faced (UNODC 2024b). In a South African survey administered across young people aged between 18 and 35, 62% said they never participate in corruption, but 67% said it was normal for ordinary people to have to pay public officials to obtain access to basic services (Corruption Watch 2020); this suggests corruption may be normalised to the point that young people do not even realise they are engaging in it.

Nevertheless, Morkūnas et al. (2024) argue that the reported positive attitudes of some Lithuanian youth towards the practice of bribery should be understood as a “forced response to government failures, rather than an intrinsic motivation”. Similarly, in a case study of Guatemala, Burrell et al. (2023) find young people’s economic precarity can make it difficult for them to avoid engaging in practices such as patronage or clientelism.d731ef975d75

Social impacts

As with the general population, young people rely on access to health care services to sustain healthy and safe lives. While the elderly, pregnant women and children are unsurprisingly disproportionally exposed to corruption risks in healthcare (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017b), there is also evidence that young people are at heightened risk of corruption when accessing certain health services.

For example, access to sexual and reproductive health services is often already “particularly challenging for youth, especially if they are unmarried or part of the LGBTQI population” due to stigma regarding youth sexual activity, restrictive laws and information asymmetries, among other things (Schoeberlein 2021). The often-clandestine nature of how sexual and reproductive health services are provided to young people can make them vulnerable to extortive practices such as overcharging.

Furthermore, medical illnesses or conditions to which young people are susceptible may be exacerbated by corruption. For example, the recent growth of the youth population in parts of the world means they reportedly are facing an increased risk of being affected by HIV (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2024); one study has shown that the antiretroviral therapies (ARVs) on which people living with HIV rely can be vulnerable to forms of corruption such as misappropriation and collusion in procurement (Kohler et al. 2018). Another study in Nigeria found that medical supplies containing the opioid, codeine, were embezzled and sold on the black market where it was purchased for use as a recreational drug, causing substance addiction risks especially among young people (TI Global Health 2018). There were similar findings regarding the illicit resale of psychotropic medicines for recreational purposes in Zimbabwe (Bergin 2024).

It is unsurprising that young people are exposed to and negatively impacted by corruption in the education sector considering they are among the main beneficiaries of schools and universities. The large size of the education sector and the funds it receives, as well as the high stakes associated with young people obtaining a good education, can all create corruption vulnerabilities (Kirya 2019a). Kirya (2019a) notes that a wide range of processes across primary and secondary schools are highly vulnerable to corruption. This includes, but is not limited to, bribery and favouritism in admissions, collusive cheating in examinations, bid rigging and diversion of school supplies, as well as sexual corruption21dfcf0d6782 by teachers and other staff against parents and students. Similar forms of corruption affect tertiary level institutions (Kirya 2019b). For example, it was found that sexual corruption primarily affected the 18 to 25 age group in Madagascar, namely students and young people looking for a first job (Transparency International and Equal Rights Trust 2021.

These forms of corruption severely undermine young people’s enjoyment of the advantages provided by quality education, such as improved well-being and social mobility. Corruption in the education sector is associated with unemployment and wider economic challenges young people often face. Poorer quality education or pervasive academic dishonesty can undermine the value of qualifications students obtain and their prospects for employment (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017a).

Kirya (2019a) describes how bribe demands can restrict access to education for families without the financial means to pay them, while sexual corruption attempts can lead affected students to drop out of education altogether. Albisu ArdigóandChêne (2017a) explain how that even when corruption occurs hidden from view and young people do not directly encounter it (for example, the misappropriation of funds), it can still lead to a significant loss of allocated resources for educational institutions, resulting in a lower quality learning environment due to overcrowding and poorer infrastructure. Furthermore, if nepotism and favouritism influence recruitment processes, it can lead to the employment of underqualified teachers and lecturers. Global Financial Integrity (2016) argues that illicit financial flows (IFFs), including those deriving from corruption, can lead to shortages in funding education, highlighting how the estimated volume of IFFs from Malawi represents around 300% of its annual public spending on education.

Economic impacts

Several studies shed light on how corruption contributes to the financial marginalisation of young people. In many countries, young people perceive that the rate of unemployment is partly attributable to corruption (Majadibodu 2024), such as due to the prevalence of nepotism in recruitment procedures for public sector roles (Mchunu 2019; Transparency Maldives 2015; Transparency International Hungary). One recent UK study found a majority (61%) of young people believe it to be difficult to get a job without a ‘way in’ (Machell 2023).A study carried out by the anti-corruption body in Azerbaijan found that “corruption in recruitment processes disproportionately affects young job seekers” (UNODC 2024c).

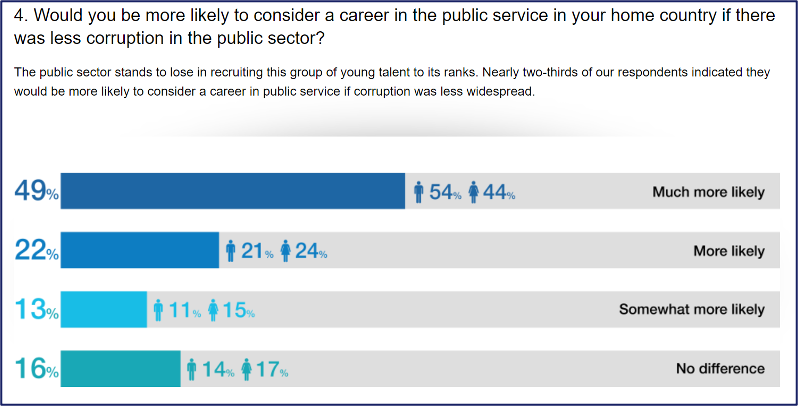

The uneven playing field that corruption in recruitment creates can lead to wider disillusionment with the public system (Bashir 2023). Indeed, responses to the 2014 MY World survey attested to this point (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Response to question in 2014 MY World survey

World Economic Forum 2015.

Other studies have pointed out how corruption can disincentivise young people from pursuing careers in sport (Amenta and Di Betta 2021), including due to the risks of sexual corruption risks in the sector (Transparency International 2022b).

Prospective young entrepreneurs may also face corruption when attempting to launch their business, for example when registering companies, accessing finance or obtaining official documentation. A 2014 survey in Mauritius found that 81.9% of respondents from the 21 to 25 age group believed they would need to pay bribes to obtain required licenses such as patents (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2024a). For similar reasons, in some studies corruption has been cited by young people as one of the main factors demotivating them from engaging in entrepreneurship (Center for International Private Enterprise 2012).

There is empirical evidence supporting the assumption that corruption contributes to youth unemployment. Comparing estimates of perceived bribery among public officials and youth unemployment rates, Bouzid (2016) found that not only is corruption associated with an increase in youth unemployment, but it also drives job seekers themselves to resort to corruption in an attempt to secure positions. Similarly, in their ethnographic study of Guatemala, Burrell et al. (2023) found that engaging in clientelism is often viewed by young people as the only possible way of securing employment. The economic impacts corruption has on young people can trigger other outcomes such as emigration (also known as “brain drain”), which may undermine a country’s wider economic growth prospects (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017a). In their study of Bosnia and Herzegovina, Begović et al. (2020) found that dissatisfaction with public services and a high perception of corruption were associated with a greater likelihood of individuals deciding to emigrate, and that this effect was stronger for people under the age of 30 than over it. In Haiti, most public sector positions are reportedly occupied by people over 35, and clientelism is perceived by young people as necessary to obtain a job, which has also been linked to emigration (France24 2019). Elsewhere, Djordjevic (2024) argues the estimated increase in labour exploitation in the Western Balkans is facilitated in part by corruption and that young people are more at risk due to their higher unemployment rate. Furthermore, sexual corruption cases have been documented in which immigration officials have exploited the vulnerable situation of young immigrants and asylum seekers, both men and women, and demanded sex from them (UNODC 2020).

Corruption may set off a vicious cycle because one of young people’s existing vulnerability factors to the impacts of corruption is their comparatively weaker access to financial resources (Muyambwai 2019). In contexts in which illicit payments are typically demanded to access basic services, unemployed young people may be at particular risk of losing out. A case study from Papua New Guinea found evidence that corruption in land administration bodies prevented young people from accessing or inheriting land, which was exacerbated by the lack of voice young people had in the sector (Transparency International and Equal Rights Trust 2021). Corruption may even affect initiatives and funds set aside for youth economic empowerment, for example the alleged misappropriation of nearly US$ 10 million from Kenya’s National Youth Service (Corruption Watch 2020).

Political and security impacts

Related to the impacts outlined in previous sections are a set of wider negative political impacts that corruption has on young people. Some have argued that corruption can cause youth disillusionment with politics and lead to apathy towards participation in political life (International IDEA 2018). However, this relationship may be more nuanced. Bekenova (2022) analysed data from 90 countries comparing the estimated level of corruption and the share of youth in parliament, finding corruption did not have a significant effect. That being said, it should be noted that the proportion of young people in parliament globally remains very low; a UN Youth Office study found that only 2.6% of parliamentarians were under 30 years of age (United Nations Office of the Secretary General’s Envoy on Youth 2023).

Nevertheless, it appears that corruption may be linked to other forms of political alienation. For example, Farzanegan and Witthuhn (2017) analysed data from 100 countries over the period between 2002 and 2012, finding that an increase in levels of estimated corruption in countries with a higher youth population (over 19% of the general population) is associated with increased political instability. They define political instability by willingness to engage in protests, but also violence, noting that corruption can engender a perception among young people that they have “nothing to lose”. Similarly, alleged corruption in the administration of elections has reportedly triggered violence in some countries that was instigated by disenchanted young people (Kahuthia Murimi 2018).

Some studies have argued that corruption can act as driver for the radicalisation of youth into terrorist and violent extremist groups (Institute for Security Studies 2016; Transparency International Defence and Security 2017). Shelley (2014) explains that “in the absence of possibilities for employment and in an environment of pervasive cynicism, youth are drawn into and can be recruited for extremist organisations.” She notes that such groups may even offer young people alternatives to public services plagued by corruption.

Corruption among police and border agents may facilitate illicit trafficking of firearms and other weapons. These often fall into the hands of young people and can lead to the escalation of higher levels of gang violence, which often disproportionally blights the lives of young people (Integrity Group Barbados 2017). Furthermore, evidence indicates that youth and ethnic minorities may be more exposed to other forms of police corruption such as attempted extortion (Gilmore and Tufail 2013), which may also contribute to disillusionment with state authorities.

The role played by youth in preventing corruption

Young peoples’ relationship with corruption should not be viewed as confined to their roles as potential victims (or perpetrators), but also in their capacity to contribute to anti-corruption measures. This includes trying to address the unique negative impacts corruption has on them personally, but also its wider societal ramifications. In all countries, especially those with large numbers of young people, youth engagement can have a transformative, legitimising effect on anti-corruption efforts (Pring 2015).

This section describes different ways young people can engage in anti-corruption, highlighting some real-life examples.

Activism and awareness raising

One of the most prominent forms of engagement is the mobilisation of young people as activists. This may take the form of standalone organisations such as integrity clubs and youth movements that are independent of other structures and have a mandate to raise awareness and advocate about corruption (Wickberg 2015). This may also take the form of more structured, specialised initiatives in the sectors young people are most in contact with; for example, where youth groups at schools and universities represent their peers and collaborate with management in matters of anti-corruption and integrity (Albisu Ardigó and Chêne 2017a).

Thai Youth Anti-Corruption Network

The Thai Youth Anti-Corruption Network was created in 2012 under a partnership between UNDP and Khon Kaen University’s College of Local Administration with a governance structure led by students. After beginning with around 35 members, the network underwent rapid growth in subsequent years with membership numbering over 4,000 students. Similarly, while initially it focused on discouraging students from engaging in corruption, its activities began to focus on preventing corruption in Thailand more widely, primarily via awareness raising carried out through conferences, camps, and social media campaigns, among other vehicles. The network has also partnered on advocacy campaigns with government and private sector actors such as the Thai Chamber of Commerce and Federation of Thai Industries respectively (Independent Commission Against Corruption of Mauritius 2019; Pring 2015).

Young people often employ creative means in their activism, such as arts and culture. For example, Fair Play is a global movement where young musicians can submit online music videos about corruption in their community; as of 2018, these videos had reached an audience of 10 million people (Kahuthia Murimi 2018). In Hungary, university students and Transparency International Hungary developed an “alternative tourist guidebook” that highlighted cases of corruption in the country (Transparency International 2022a).

Transparency International (2014) has published a Toolkit listing 15 ways in which young activists can promote anti-corruption. In 2024, members of theUnited Nations Office on Drugs and Crime’s (UNODC) YouthLED Integrity Advisory Board that comprised23 young people representing 23 different countries co-drafted Taking action against corruptionwhich outlines ten steps young activists can take to build anti-corruption initiatives.

Aside from raising general levels of awareness, youth activism can trigger tangible outcomes such as legislative changes or ensuring greater accountability for corrupt actors, as evident from examples around the world. In Kyrgyzstan, young people active on social media were viewed as significant organisers of protests held in response to allegations of electoral fraud (Egwu 2020). In Indonesia, Wahyuningroem et al. (2023) found that young people played a significant role in building both strong online and offline movements protesting the ratification of the Draft Law (RUU) of the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), which some observes alleged was an effort to curtail civil liberties. Ortiz et al. (2022) found that the number of protests led by young people and/or students increased by more than sixfold globally between 2006 and 2020, and that corruption was the second most common issue behind such protests. It should be stressed that the role of young activists, as with members of the general population, may not always be neutral and indeed can be liable to forms of partisanship that weaken anti-corruption efforts (International IDEA 2018).

Youths for Integrity Fiji

Youths for Integrity Fiji is a network made of around 150 young Fijians that was established by the local Transparency International chapter Integrity Fiji. It focuses on awareness raising activities including through arts and culture. The network also collaborates with the Fiji Independent Commission Against Corruption to raise awareness about the financial losses incurred by corruption in the country.

In 2021, the network launched an advocacy campaign to oppose a draft bill which allegedly would have granted police wide-reaching investigative powers threatening the enjoyment of civil liberties. They issued a press release on some of Fiji’s most prominent media platforms. The decision of former prime minister Bainimarama to subsequently withdraw the bill was credited to the role of civil society actions like those of Youths for Integrity Fiji (Transparency International 2023).

Education of young people

Educating young people about corruption and its negative impacts is generally thought to be a key preventative measure. For example, studies carried out in Nigeria and Ukraine indicate that effectively tailored integrity education can result in a reduction in corrupt behaviour on the part of young people and students (UNODC 2024c; Borcan et al. 2023).

In their formative years, young people may be more impressionable, meaningful efforts can be taken to ensure they do not internalise a tolerance of corruption (Pring 2015). Civic education in this regard can be a strategic entry point to spread positive values across society (International IDEA 2018). This need not constitute a didactic transfer of knowledge from adult educator to young student; young people can also shape the anti-corruption education they receive.

While in many contexts, young people have a reasonable level of awareness of corruption and its impacts on them (Corruption Watch 2020; Duri 2020), this should not be taken for granted. For example, a survey of Indonesian youth found more than half could not define the word integrity, while many were unable to identify if an act constituted corruption or not (Sihombing 2018). Other surveys have indicated that young people may perceive corruption as irrelevant to their lives (Chile Transparente 2023).

There is thus potential for civic education that enhances the understanding of governance concepts and their relevance for young people. Participants in a youth forum held on the margins of 2021 Special session of the General Assembly (UNGASS) against corruption said it was “necessary to substantially strengthen educational programmes on integrity, transparency and anti-corruption, starting from a very young age” (United Nations 2021a). The UNODC’s Global Resource for Anti-Corruption Education and Youth Empowerment initiative (GRACE) has pioneered value-based education, collaborating with Malawi national stakeholders to develop anti-corruption educational material for primary level students which is based on the indigenous philosophy of Umunthu (UNODC 2023c).

Such programmes can be integrated into school and university curricula as standalone subjects or integrated into existing subjects. Kirya (2019a) explains this could constitute, for example, introducing a specific course on public integrity into schools or inviting anti-corruption commissions and CSOs to deliver ad-hoc ethics trainings. States responding to a 2024 UNODC study largely indicated they relied on a mix of formal and non-formal methods to educate young people on corruption, for example legally requiring such modules to be integrated in school curricula (UNODC 2024c).

Anti-corruption education may also be delivered in extracurricular settings (International IDEA 2018). An example is the Vietnam Integrity School, which brings young people together “to learn about anti-corruption, exchange ideas and discuss what integrity means in their daily lives, including family, school, and work, as well as at the national level” (Tong 2020).

Bentley and Mullard (2019) collected data on and analysed a youth fellowship programme implemented by Accountability Lab Nepal. Participating fellows shadow and are mentored by so-called “integrity trendsetters”, that is public servants who have resisted corruption and displayed integrity in their roles. They found the intervention was effective: participating young people often overcame initial scepticism towards public servants, the experience increased their trust in public officials, and they learned that career progression in the public sector does not need to rely on corruption.

Materials used to educate young people should be appropriately tailored; for example, evidence indicates young people may be less responsive to anti-corruption messaging in print media and more responsive to mediums such as YouTube videos or cartoons (Ishikawa 2024). Materials can also be developed to educate young people on some of the specific risks they face. For example, UNDP (2020) developed the Business Integrity Toolkit for Young Entrepreneurs, which guides budding entrepreneurs on how to navigate the typical corruption challenges they might face when establishing a business.

A related avenue is the growing call to use recovered proceeds of corruption to fund education and employment opportunities for young people (UNICRI 2022). For example, the BOTA Foundation ensured that a portion of the recovered proceeds derived from corruption perpetrated by political elites in Kazakhstan were used to fund needs-based scholarships for youth to attend institutions of higher education (World Economic Forum 2022).

Innovation

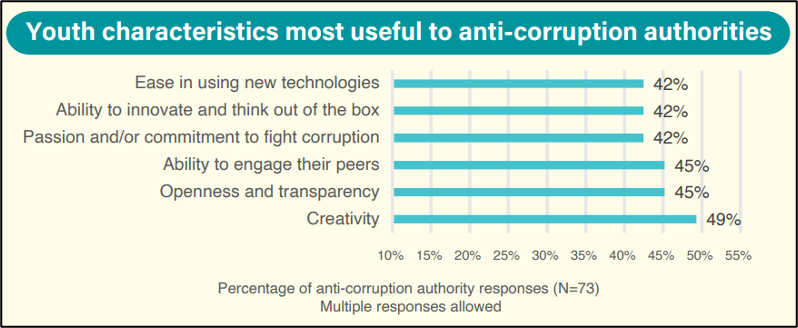

Pring (2015) explains that one of the main benefits of engaging young people is that they “are more likely to be creative in their approach to problem-solving, meaning anti-corruption efforts may be more innovative, forward-thinking, and make better use of modern technology”. In this sense, younger people can bring insights and novel techniques with which older generations involved in anti-corruption efforts may be less familiar. Responses to a UNODC (2023) survey of 73 anti-corruption authorities around the world indicate widespread endorsement of young people’s potentially innovative contribution, including in using new technologies (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: responses of anti-corruption authorities to UNODC survey on youth engagement

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2023.

There are different vehicles to facilitate youth innovation, such as brainstorming sessions, incubation labs, hackathons or competitions where winning ideas are given seed funding so they can be realised in practice (United Nations Development Programme 2018).

Evidence shows that this can lead to tangible and impactful results. For example, in Kosovo, the DigiPrishtina hackathon – where young computer programmers gather to develop tech solutions – led to the development of e-recruitment and e-spending tools to monitor corruption risks in municipality recruitment processes and the flow of public funds at the local level respectively (Neziri 2015). In another example from Kosovo, a social innovation camp involving youth activists led to the establishment of a crowdsourcing platform to support the engagement of girls in the fight against corruption (Neziri 2015). Mahlangu (2023) suggests other potential innovative ideas that young people could explore to prevent corruption, such as developing “interactive mobile games or apps that simulate real-life corruption scenarios” and establishing a ‘name-and-fame’ programme rewards youth-owned businesses operating with integrity.

Bentley and Mullard (2020) studied the “Accountability Incubator” programme operated by Accountability Lab and that as of 2020, was being implemented in one Latin American, five African and two Asian countries. Under the programme, young civil society leaders receive mentoring and capacity-building with the aim of developing their own ideas and tools to enhance accountability. Using implementation in Nepal as a case study, Bentley and Mullard found that the ideas participants developed were diverse, relying on methods such as database development, social media tools and apps, film and theatre and encompassing numerous research, policy and advocacy tactics, including attempts to measures the extent of corruption. They found that programmes perform best when they give young people funding and space “to trial, fail, learn, and re-design innovative solutions.”

Monitoring and reporting

The availability of new technological solutions to collect and track data provides another important entry point for youth engagement in anti-corruption (Transparency International Hungary 2016). There are several emerging examples of young people taking an active role in monitoring the flow of funds to detect potential corruption, especially in the public sector. The European Commission-funded YouMonitor project of the EU published a toolkit which aims to empower young people to establish monitoring communities against corruption.

In Paraguay, the youth-led organisation Reacción Juvenil de Cambio Paraguay built the capacity of students to monitor the spending of resources from the national budget allocated to their schools and report any potential irregularities (Pring 2015). In Bangladesh, the Youth Engagement and Support (YES) network, which has over 4,000 youth volunteers and 61 branches, supported the monitoring of a social safety programme called Vulnerable Group Development. Numerous branches were involved in verifying the eligibility of beneficiaries to prevent mistakes. They also identified corruption risks such as favouritism; out of an estimated 95,000 cases, they informed the local authorities of 2,800 suspect cases, which reportedly accounted for more than US$ 400,000 (Transparency International 2022a). Similarly, in Palestine, a group of local students assessed the quality of public roadworks being constructed and found that the construction company had been using inferior quality materials to save on costs, triggering an anti-corruption investigation (Transparency International 2022a). One corollary of young people being exposed to corruption is that they can potentially report it, which in turn, can lead to corrupt actors being held to account and deterring other potential wrongdoers. The United Nations (2021a) have argued that young people may be even more likely to report corruption after seeing it with “fresh eyes”.

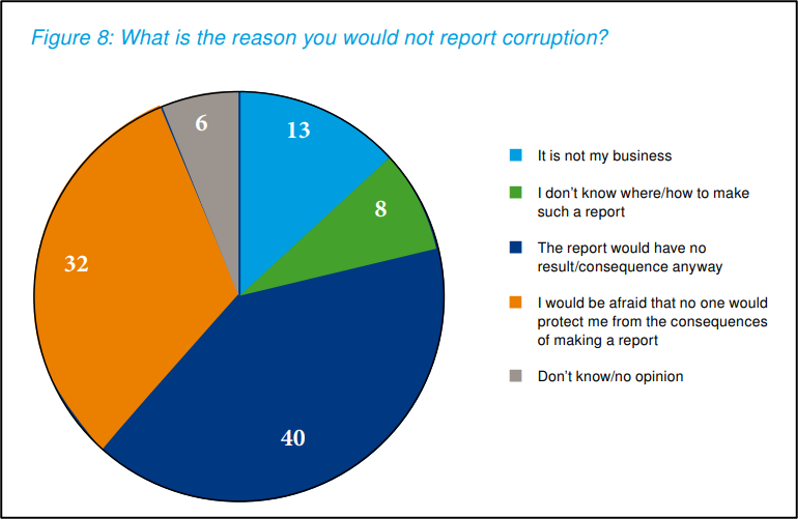

Nevertheless, some young people may be reluctant to report corruption. There were mixed responses to a questionnaire distributed to young people by the Independent Commission Against Corruption of Mauritius (2019) on their willingness to report corruption. Many respondents who indicated a willingness to report corruption they would encounter based their answer on a sense of justice or duty. However, young people who stated their unwillingness to report corruption cited reasons such as fear of reprisals and a general lack of interest. In a 2016 survey by Transparency International Hungary of young people aged 18 to 29, respondents who said they would be unwilling to report corruption shared their reasons (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: responses to a TI Hungary survey

Transparency International Hungary 2016.

In a study of young people in Lithuania, Toleikienė et al. (2020) found that their motivation to inform or withhold information about corruption was also influenced by variables such as gender, social status and level of civil and political activity.

However, there is more encouraging evidence suggesting that attitudes to reporting wrongdoing can undergo a shift. In the same survey from Transparency International Hungary of young people aged 18 to 29, 66% of respondents said they would report corruption if they encountered it, which represented a 25% increase from a previous iteration of the survey in 2012.

Measures that address the reasons behind young people’s reluctance to report corruption may inform efforts to incentivise them to do so. Participants in a youth forum held on the margins of 2021 Special session of the General Assembly (UNGASS) recommended that states and other relevant actors ensure young people have access to secure and anonymous reporting channels as well as mechanisms such as legal representation, financial assistance, and mental health support (United Nations 2021a).

Meaningful youth engagement

While there are a range of emerging positive examples, some commentators warn that the potential of youth engagement in anti-corruption remains underutilised or is treated as tokenistic or cosmetic by national authorities (Wickeberg 2015; Kahuthia Murimi 2018). Hjulmann and Andersen (2011) caution that while youth are sometimes referred to as being important actors in anti-corruption efforts, they are rarely provided with meaningful opportunities to influence decision-making processes.

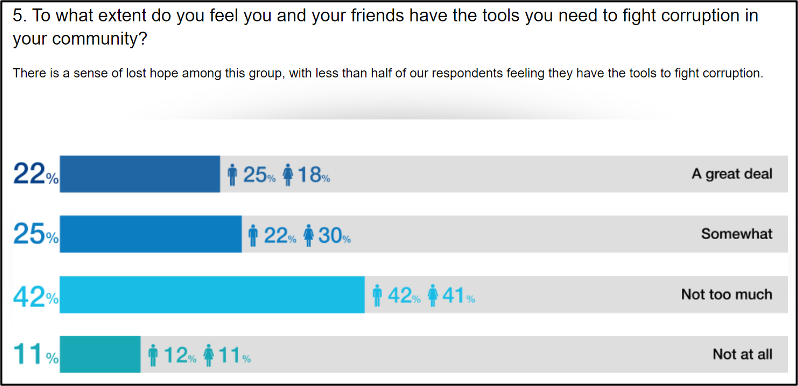

These views are supported by some survey evidence. Responses to the UN ‘s 2014 MY World survey suggest that young people largely do not feel they are adequately equipped to fight corruption in their local community (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: Responses to question in 2014 MY World survey

World Economic Forum 2015.

In Mauritius the majority of young respondents to a study said they were not fully involved in any anti-corruption activities despite at the same time expressing a desire to be more involved (Independent Commission Against Corruption of Mauritius 2019). A survey in Chile found that young people often develop feelings of helplessness and hopelessness in face of inadequate steps to involve them, which may demotivate them in terms of confronting corruption (Chile Transparente 2023).

These considerations have led many voices in the field to stress the importance of “meaningful” youth engagement. In this vein, Kahuthia Murimi (2018) argues:

‘For young people to significantly contribute to the fight against corruption, states and other stakeholders in addressing corruption need to be clear and genuine about the timing of youth engagement in anti-corruption initiatives, the degree of their involvement, who among the youth is to be engaged and the level of control that young people have in driving such initiatives.’

Similarly, Wickberg (2015) explains youth engagement efforts tend to be more sustainable and successful when they are led by young people, but also where they are integrated effectively into existing anti-corruption structures and initiatives. The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (n.d.) operates a YouthLED Integrity Boardcomprised of young people who play an advisory role to its anti-corruption work; UNODC (2023a; 2023b) has also called on anti-corruption authorities globally to step up their engagement of young people in their activities to prevent corruption, communicate with stakeholders and more effectively manage resources. It recommends such authorities create the enabling conditions for youth engagement in anti-corruption work and facilitate their participation across all stages of implementation.

- Transparency International (n.d.) defines patronage as a “form of favouritism in which a person is selected, regardless of qualifications or entitlement, for a job or government benefit because of affiliations or connections.”

- Bjarnegård et al. (2024) define sexual corruption as occurring "when a person abuses their entrusted authority to obtain a sexual favour in exchange for a service or benefit that is connected to the entrusted authority.