1. The JKN programme: Positive impact, sustainability concerns

On January 1, 2014, Indonesia launched its National Health Insurance programme (Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional, JKN). Its central objective was to achieve financial protection and health equity through universal health coverage within five years, by 2019. The programme was also expected to improve health outcomes, address regional disparities in service quality and accessibility, manage resources effectively, and invest in health promotion and prevention programmes. The JKN is based on a mandate in the 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia, which states that‘everyone has the right to live in prosperity, physically and spiritually, to have a place to reside, to enjoy a good and healthy living environment, and to be entitled to obtain health care’.7993eb7e5cc4

The Health Social Security Agency (Badan Penyelenggara Jaminan Sosial Kesehatan, BPJS-K) administers the JKN. A single-payer system, it manages membership, collects premiums, administers contracts with providers, and pays providers.c90081349476 BPJS-K participants are divided into two groups, with the government subsidising registration and premium payments for those in the poorer group. Every participant enrolled in the JKN programme has a card with an identification number that is used to access health care services. The system is based on capitation for primary health care and case-based payments (INA-CBG) for advanced health care in referral facilities. In some cases, co-payment is required to access health services.b1484ba336a6

The JKN programme has clearly increased Indonesians’ access to health care. As of 2020, 22.2 million people (82.33% of the total population) are enrolled.99ad7d3ca841 The JKN programme, however, has run large deficits since 2014, which threatens its continued sustainability. In 2020, BPJS-K recorded a deficit of US$392 million.9f72e3b39a91 According to the Indonesian Supreme Audit Board (Badan Pemeriksa Keuangan), various factors contribute to the deficit – fraud and corruption among them. Yet fraud prevention and detection efforts are inadequate, and weak law enforcement is also a problem.9d735d57ed51

2. Health insurance fraud in Indonesia: Current situation

In the Indonesian context and hence in this study, fraud and corruption are seen as having a mutually reinforcing causal relationship, and the terms are often used interchangeably. Fraud in the National Health Insurance programme is defined under Indonesian law as an act that is carried out intentionally to obtain financial benefits from the programme through corrupt means.62c3c48ddad2 It is associated with graft in procurement processes, patronage, and clientelism.09f30b767e3d The following sections look briefly at the manifestations, drivers, and impact of fraud in the JKN programme.

2.1 Typologies and manifestations of health insurance fraud

Generally speaking, fraud in national health insurance schemes can include billing for services not rendered, unnecessary medical testing and overtreatment, fictitious providers, double billing, coding fragmentation, kickbacks, multiple claim submissions or alterations to claims, and third-party fraud, among other forms. All of these exist in the Indonesian health services, with bribery being one of the most common fraud schemes. Perpetrators include participants; BPJS-K; health facilities or health service providers including doctors, dentists, specialist doctors, specialist dentists, other health workers, and administrative personnel; providers of medicines and medical devices; and other stakeholders such as employers. One common practice involves unnecessary referrals from primary health care centres (fasilitas kesehatan tingkat pertama, FKTP) to advanced-level referral health facilities (fasilitas kesehatan rujukan tingkat lanjut, FKRTL) for the purpose of increasing reimbursement or gaining kickbacks.

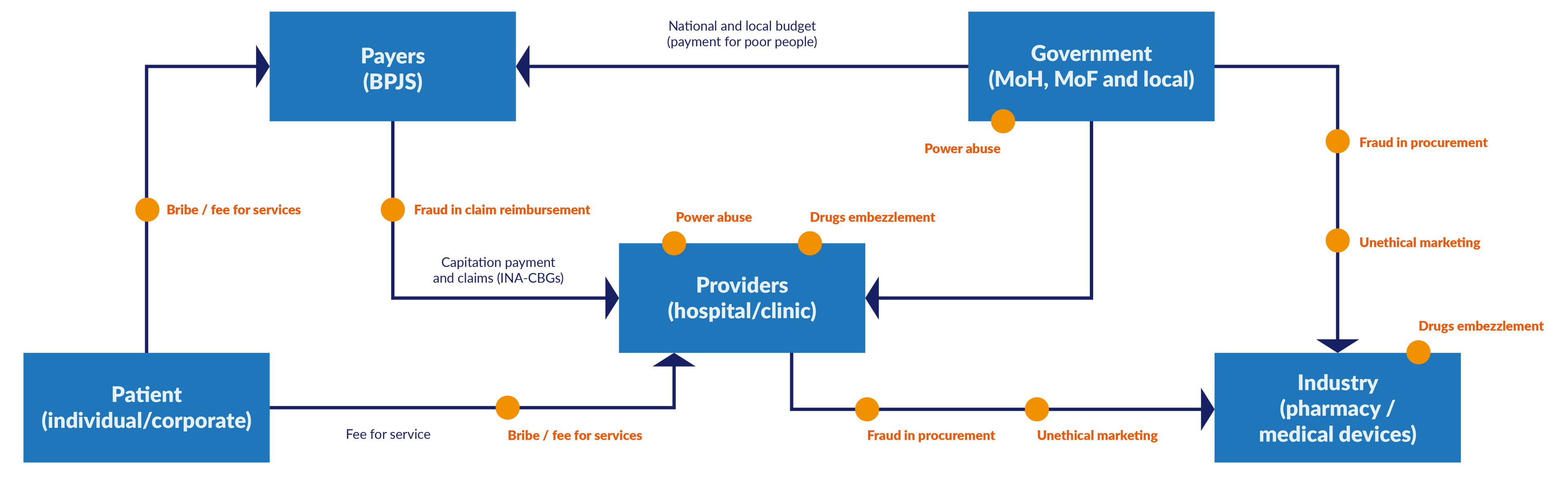

In a 2016 study, the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi, KPK) identified fraud and other corruption risks in each phase of the JKN programme implementation (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Fraud and corruption risk in Indonesia’s National Health Insurance programme

Source: Ariati 2016. MoH = Ministry of Health. MoF = Ministry of Finance.

Table 1 shows fraud risks and recorded fraud incidents in Indonesia between 2016 and 2021. The data is based on a literature review and on interviews with respondents conducted in August-September 2021.

Table 1. Typologies of fraud in Indonesia’s National Health Insurance programme

|

Perpetrator |

Fraud risk |

Recorded fraud incidents in Indonesia 2016–2021 |

|

Participants |

|

|

|

BPJS-K |

|

No data on fraud incidents. |

|

Health facilities or health service providers, including doctors, dentists, specialists, health workers, and administrative staff |

|

|

|

Drug and medical device providers |

Drug providers

Medical device providers

|

|

|

Other stakeholder (employer) |

|

|

2.2 Drivers of health insurance fraud

The main drivers of fraud in JKN are low salaries, information asymmetry in the health sector, and the absence of effective counter-fraud measures.

Health sector personnel in Indonesia are poorly paid.6974f9316ab3 Based on data from the government statistics bureau, the average monthly salary in the Indonesian health service sector was around $224 in February 2022.2716f2fd6ee8 The lowest-paid doctors are in Bengkulu Province, earning around $91 per month on average.5f49fb8381cf Low salaries may provide a motivation for health care personnel to engage in fraud and corruption to supplement their earnings. For instance, the KPK suspects that health care personnel often split the ‘financial benefits’ obtained from filing BPJS-K capitation claims.79c10534feba Health providers can easily manipulate the sale of drugs or medical devices: for example, hospitals may sell syringes at a price that is higher than the normal price.5d119fbce354

The situation is not helped by the information asymmetries between patients and health care providers, especially as regards expected service delivery and cost. Most patients in Indonesia do not understand health care procedures, leaving them vulnerable to over-prescription and unnecessary procedures.

Fraud and corruption continue because of the ineffectiveness of current anti-fraud and anti-corruption measures. For example, the fraud prevention team in the JKN does not function effectively. There are no fraud risk management guidelines in place, and the anti-fraud and ethics education programmes are inadequate.137f0d275c0d Fraud prevention is not a significant concern in the health sector, and most approaches to fraud are reactive rather than preventative: that is, management only reacts when fraud has occurred.fd32c5f5f24d

2.3 Impact of health insurance fraud

Due to the lack of records, it is difficult to determine the direct and indirect impacts of fraud in the JKN programme. Nonetheless, it may be surmised that JKN-related fraud has a cumulative effect on several vital areas or subsectors of the health system, as outlined below.

Service delivery. Corruption is a barrier to health care access and erodes the quality, equity, and efficiency of health care services.68207c7f9e27 Fraud foments a culture of corruption at the point of health care service delivery. In a Transparency International survey conducted in 2020, 10% of Indonesian respondents reported having paid a bribe to access health services in the preceding 12 months, and 19% had used personal connections for that purpose.2572d06f6425 A study from the Indonesian Corruption Eradication Commission has shown that health service delivery does not meet existing quality standards, which could be due in part to fraud.55aea9425b17 Fraud is plainly a matter of life and death: a study from the United States showed a 25% increased risk of dying among patients treated by health care professionals who had been convicted of fraud.faeccac1c874 As access, quality, and effectiveness of care is hampered, population health declines.

Pharmaceuticals and medical products. Fraud in the JKN contributes to the larger problem of pharmaceuticals-related fraud58995ae7d2ca and to the proliferation of substandard and falsified medicines and medical products on the black market. There are individuals who falsify market licenses in order to distribute cheaper medical devices of poorer quality.ef1fa053ae2e Fraud also contributes to medicine shortages.2f10b603d4c0 In Indonesia, corruption and lack of transparency affects drug pricing.ed67bf4fbc0a Not all drug and medical device entrepreneurs have registered their products in the e-catalogue as required by law, which leads to price distortion and disruption of procurement protocols.ad600c3851e5

Doctors often get a discount of 10%–20% on drug sales from pharmaceutical companies in the form of monetary and non-monetary gratuities. This incentivises doctors to prescribe more drugs than needed and to favour expensive drug brands over cheaper ones.d1cc10251c84 In some hospitals, there are individuals who sell medical devices at inflated prices.c5ea989a425f Corruption leads to parallel trading and off-label use of pharmaceuticals.d64a13f9256d

Health workforce. Fraud and corruption weaken the quality of the health workforce,with bad doctors driving out good doctors. Health sector corruption is one of the drivers for the brain drain of medical personnel, who emigrate to take up employment outside the country.42e275b823c2

Health financing. Fraud leads to financial loss and is involved in the loss of capitation funds.645dfa1f0323 In 2018, four out of six hospitals submitted overpayment claims to BPJS-K with hospital classes that were not in accordance with MoH standards.417e7bdfc544 KPK investigations found that unnecessary treatment in cataract surgery between 2014 and 2017 cost the economy $42.8 million, and phantom billing in physiotherapeutic services cost $35,049.317ece738665 These are big financial losses for only two relatively narrow areas of health care.

3. Legal and regulatory framework for health insurance fraud in Indonesia

As mentioned above, current anti-fraud measures in the health insurance system are ineffective. One of the reasons is that the regulatory framework that governs the JKN programme does not include any specific regulations or guidance on fraud risk mitigation at the operational level. Furthermore, Indonesia does not have a specific law concerning health insurance fraud; instead it has multiple provisions scattered across various laws, both civil and criminal.330bc8239774 The JKN regulations only provide administrative sanctions for fraud. There is therefore an urgent need to consolidate and streamline the existing laws and regulations to promote a harmonised and consistent approach to reducing fraud in the JKN.

3.1. Laws, regulations, and codes of conduct governing health care fraud and corruption

Law No. 40 of 2004 on the National Social Security System. This provides the legal basis for the JKN programme. It sets out principles and objectives and provides for administering federal guarantees. It also explains the duties and responsibilities of the National Social Security Board (Dewan Jaminan Sosial Nasional, DJSN) and stipulates which groups are covered and the types of services the JKN should provide. It does not say anything about fraud.

Presidential Regulation No. 82 of 2018 on health insurance. The regulation explains the mechanism for implementing the JKN in Indonesia and regulates fraud prevention and handling in the programme. Articles 92 to 95 stipulate the definition of fraud and the sanctions for fraudulent acts. The regulation establishes an anti-fraud team with representatives from various institutions. The law is regarded as too general in scope and not specific enough for an effective approach; nonetheless, it lays the foundation for the JKN to enact more detailed actions and sanctions against fraud and corruption.

Ministry of Health Regulation No. 16 of 2019 on prevention and handling of fraud and the imposition of administrative sanctions against fraud in the JKN. The regulation covers types of fraud, fraud prevention, fraud handling, imposition of administrative sanctions, and guidance and supervision. This makes it the most comprehensive piece of legislation on addressing fraud in Indonesia’s health care system. The fraud prevention and handling strategy is more detailed than in other regulations, and administrative sanctions are specified. There are clear technical instructions for implementing anti-fraud efforts. However, the regulation is unclear on the mechanism for escalating administrative sanctions to criminal sanctions. Another problem is that not enough funding has been made available for the infrastructure and personnel needed to implement the law.

BPJS-K Regulation No. 6 of 2020 on the fraud prevention system in the health insurance programme. The BPJS-K regulation provides a fraud prevention system for health facilities, providers, and participants. It promotes a fraud prevention culture through education and socialisation (the promotion of a new societal culture of integrity). It also provides for monitoring and evaluation and recommends methods of fraud risk management. However, it does not provide specific guidance for health facilities on how to conduct and follow up on a fraud risk assessment, and this has negatively affected its implementation. Our interviews showed that there is confusion and uncertainty among stakeholders on how to conduct such an assessment. Indeed, we did not find any evidence that any of the concerned actors has conducted a fraud risk assessment.

Prevention consists of formulating fraud prevention policies and guidelines in accordance with the principles of good corporate governance and good clinical governance. It also includes the preparation of specific fraud risk management guidelines designed to promote a culture of integrity, ethical values, standards of behaviour, and anti-fraud education and awareness raising among concerned parties. Fraud prevention should also involve creating a positive environment for the implementation of the health insurance programme and the development of health services oriented to quality control and cost control. Towards this end, the law calls for the establishment of a quality control and cost control team and for a fraud prevention team that is tailored to the needs and scale of each health care organisation.

Detection and response are the responsibility of the fraud prevention teams at BPJS-K health facilities and district/city health offices, as well as the prevention and handling teams at the provincial or central level, in accordance with their respective mandates. The law explains how fraud detection should proceed, from identification to the reporting stage. Fraud identification may be based on an analysis of data on health care claims, membership, payment of contributions, history of health services, and capitation. Other types of data that should be scrutinised include data on availability and use of drugs and medical devices as well as data on complaints. A detection report should follow. It should include a description of the alleged fraudulent acts, specifying time of occurrence, setting, perpetrators, chronology of events, potential financial loss, and loss or misuse of health care resources such as medical supplies and drugs. Initial evidence can be in the form of data/sound/picture/video recordings, copies of documents, and other such evidence. Lastly, the team submits the results of the detection to the leaders of each institution.

Fraud responses involve exposure, follow-up on completion of recommendations, monitoring and evaluation, and reporting. Fraud settlement is carried out internally in each institution. In the event that an individual or institution – a participant, BPJS-K, a health facility or health service provider, a provider of drugs or medical devices, or another stakeholder – commits fraud in the implementation of the health insurance programme, the minister, head of provincial health office, head of district/city health service, or other official or authorised agency may impose administrative sanctions. These may take the form of (a) a verbal warning; (b) a written warning; (c) an order for the return of losses due to fraudulent actions to the injured party; (d) additional administrative fines; and/or (e) license revocation. Administrative sanctions do not preclude criminal sanctions,556f055e7552 and courts may impose criminal sanctions on perpetrators who violate the JKN laws.

3.2. Enforcement of anti-fraud measures: Progress and challenges

We sought to discern the extent to which the law and guidelines are adhered to in responding to fraud. We found that each party involved in the JKN programme has established a reporting channel and whistle-blowing system that enables anyone to report fraud without fear of retaliation. Each organisation manages its reporting channel independently (Table 2).

Table 2. Reporting channels for fraud

|

Organization |

Availability of reporting channel (whistle-blowing system) for fraud in JKN |

|

Ministry of Health |

Website: https://itjen.kemkes.go.id/pengaduan. |

|

Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) |

Website: kpk.go.id. The KPK also has a public data disclosure initiative called JAGA (https://jaga.id/?vnk=fa6473ab). |

|

Health Social Security Agency (BPJS-K) |

Email: wbs@bpjs-kesehatan.go.id. |

|

Health district office |

Available, including reporting channel for FKTPs. |

|

Public hospital |

Email: upik@jogjakota.go.id; suggestion box. |

|

Indonesian Medical Association (IDI) |

Website: http://mkekidi.id/formulir-pengaduan/. |

|

International Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Group |

Available. |

Sources: Interviews with MoH, KPK, BPJS-K, Puskesmas, Health District Office, and IDI.

Individuals suspected of committing fraud receive a warning. If the act is proven, the individual is sanctioned. For example, a general doctor or dentist will receive a warning from the Indonesian Medical Association or Indonesian Dental Association, while specialist doctors and dentists will be given notice by their respective professional associations. Members of the International Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Group (IPMG) who commit fraud receive a warning or sanction from the IPMG’s managing director. Sanctions can involve the revocation of a distribution permit or cancellation of membership in a professional association.625cbb12b1fd In private hospitals, the department head warns personnel (usually doctors) who commit fraud. If there is no response, the perpetrator is penalised, for example, through dismissal from the hospital.a7e1a7e57707 Other sanctions that have been imposed include contract termination with BPJS-K6bf3fca13174 or refund and return of the payment to BPJS-K.06bf49d895cf For example, BPJS-K asked 92 hospitals in various regions to refund the difference in cost for service claims that had been inappropriately inflated (total cost $54.6 million).20c9ab654786 BPJS-K has also terminated its relationship with about 70 hospitals because they committed fraud.1413744d4ef6

Our findings show that one of the challenges regarding enforcement is that there is a multiplicity of teams and actors with responsibilities for detecting and reporting fraud, which leads to lack of clarity, duplication, and overlap. Also, the lack of a mechanism for escalating administrative to criminal sanctions may be hindering the effectiveness of current approaches. The law does not provide a specific mechanism for collaboration between the JKN and Ministry of Health anti-fraud measures and the criminal prosecution service, yet the existing administrative sanctions may not be sufficient to deter fraudulent behaviour. Nonetheless, we found 14 court decisions between 2017 and 2021 in which criminal sanctions were imposed on perpetrators of fraud in the JKN. Most of the cases concerned corruption in primary health services (see Annex 2).

4. Good practices and lessons learned in managing health care fraud and corruption

4.1. Ethics codes, policies, and guidelines

Notwithstanding the problems mentioned above, the existing policies and guidelines for fraud prevention, detection, and response provide a foundation that can be built upon and improved.546498bc3a15 For example, the Indonesian Financial and Development Supervisory Agency (Badan Pengawasan Keuangan dan Pembangunan, BPKP) has put in place a Fraud Control Plan for several priority areas in the health sector. The plan includes six stages: socialisation, institutional commitment, determination of score evaluation, presentation of evaluation results, reporting, and follow-up and monitoring. Unfortunately,the BPKP has only provided assistance at the socialisation stage.aa818b7f81df

Several other institutions have established guidelines that can play a role in reducing fraud. BPJS-K has a code of ethics that addresses fraud,1715d1260cc0 and the Indonesian Medical Association (Ikatan Dokter Indonesia, IDI) established Guidelines for the Prevention of Fraud in implementing the JKN programme for doctors in Indonesia in 2018. The IPMG has a code of ethics for its members which provides for handling of fraud-related complaints.172bddbc1955

In 2019, the board of directors at a private hospital in Surakarta issued a regulation to govern third-party relationships. The regulation provides forms that health workers and hospital employees can fill out to declare or report conflicts of interest to the KPK. The private hospital also signed the KPK integrity pact, which states that hospital employees and officers shall not commit fraud in the hospital environment.

4.2. Automation and digitisation

The National Public Procurement Agency (Lembaga Kebijakan Pengadaan Barang/Jasa Pemerintah, LKPP) oversees the procurement of public goods and services, including for the health sector. IPMG and Gakeslab (Association of Laboratory and Health-care Businesses) sell medicine and medical equipment through an electronic catalogue which complies with the LKPP regulation on procurement through online stores and e-catalogues.467a7b92d070

MoH Regulation No. 5 of 2019, on planning and procurement of medicines through electronic catalogues, provides that public entities such as the health district office or government hospital as well as pharmaceutical companies must submit a medicine needs plan (RKO) to the MoH. The RKO helps in minimising medicine shortages, reducing inequality in access to medicines, and ensuring that medicine prices do not exceed e-catalogue standards.f0a7b4266dd3 Each RKO is reviewed by the head of health care facilities before it is submitted to the e-catalogue.

4.3. Specialised anti-fraud teams

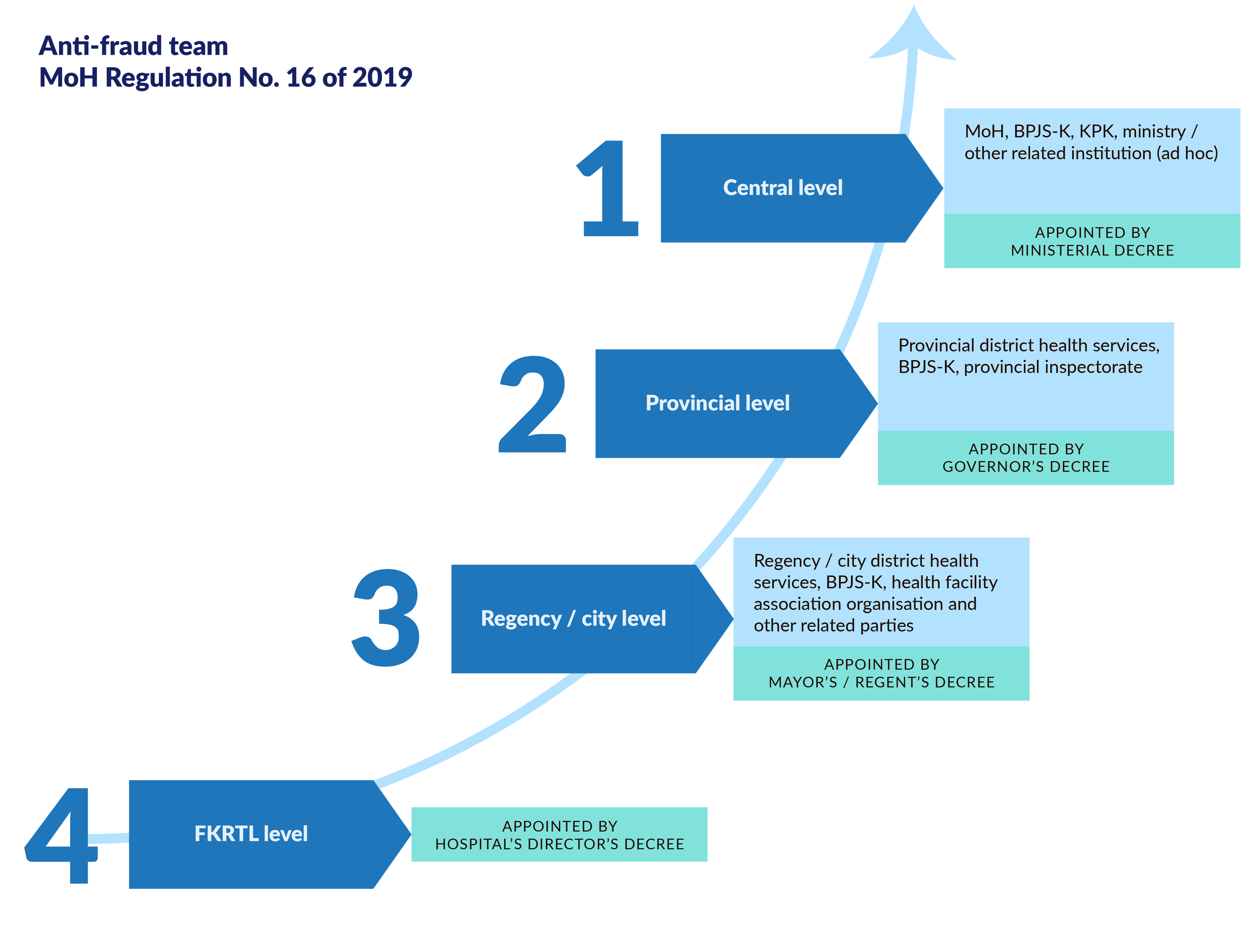

Specialisation builds knowledge and skills on fraud prevention and prioritises it as a key organisational function. MoH Regulation No. 16 of 2019 mandates the establishment of anti-fraud teams at the national (central), local (province and city/regency), and FKRTL levels (Figure 2). The main tasks of the fraud prevention and handling teams at the central and local levels are to promote quality control and cost control while also promoting a culture of fraud prevention and good organisational and clinical governance. The teams are also mandated to handle fraud cases and to ensure the proper monitoring and evaluation of anti-fraud interventions. Unfortunately, although the anti-fraud teams have been established, they are not fulfilling their roles in accordance with their mandates under MoH Regulation No. 16. Improving their effectiveness could go a long way towards enhancing fraud prevention and appropriate handling of fraud cases in the JKN programme.7fa4f435543f

Figure 2. Anti-fraud teams in the JKN programme

Table 3 summarises our findings regarding the current status of these teams based on interviews with respondents in 2021.

Table 3. Status and role of anti-fraud teams in the JKN programme

|

Organisation |

Status |

Role |

Notes |

||

|

|

Implemented |

Not yet implemented |

National |

Local |

|

|

MoH |

X |

|

X |

|

The anti-fraud team has not implemented the anti-fraud programme properly because of the Covid-19 pandemic. |

|

|

X |

|

X |

||

|

BPJS-K |

X |

|

X |

X |

BPJS-K has coordinated with other institutions. |

|

KPK |

X |

|

X |

|

KPK has established a socialisation programme at the district and city levels to form an anti-fraud prevention team. But due to the pandemic the extent of the fraud team’s engagement and success is not known. |

|

Serang District Health Office |

X |

|

|

X |

The team has not carried out activities optimally. |

|

Private hospital in Surakarta |

|

X |

|

X |

The private hospital has not been included as an anti-fraud team at the district level, but the hospital has an internal team to minimise fraud in the facility. |

|

Indonesian Dental Association (PDGI) |

|

X |

|

X |

|

|

Indonesian Hospital Association (PERSI) |

|

X |

X |

|

If there is a dispute between BPJS-K and the hospital, the hospital must write a letter asking for clarification. The regional PERSI will act as a mediator at the regional level. |

|

Association of Indonesia Local Health Offices (ADINKES) |

|

X |

|

X |

If there is a dispute between a health care centre and BPJS-K regarding JKN fraud, ADINKES will provide technical assistance, for example, by proposing regulations related to fraud control. |

|

Puskesmas (primary health care centres) and Paguyuban Puskesmas (community health centres) |

|

X |

|

X |

There is an internal control system that performs claim verification together with the verification team. |

Sources: Interviews with MoH, KPK, Health Service District, private hospital in Surakarta, BPJS-K, PDGI, PERKLIN, PERSI, and ADINKES.

4.4. Education and awareness raising

Some organisations implement anti-fraud awareness and education programmes. For example, the Ministry of Health conducts anti-fraud education programmes for health facilities, and BPJS-K conducts regular seminars on digitising anti-fraud policies for the regions. BPJS-K has established three forums that run twice a year at the provincial and district/city levels. The Indonesian Public Health-Observer Information Forum (FORKEMI) raises awareness of services to participants, while the supervision forum focuses on how business entities comply with and implement their obligations. Lastly, there is a stakeholder communication forum.a049c445a435

Organisations that have carried out anti-fraud awareness activities include the Serang District Health Office, the Surakarta private hospital, the Indonesian Hospital Association (Perhimpunan Rumah Sakit Seluruh Indonesia, PERSI), and the Indonesian Clinic Association (Perhimpunan Pengusaha Klinik Indonesia, PERKLIN). The Indonesian Dental Association (Persatuan Dokter Gigi Indonesia, PDGI) and Gakeslab have been cooperating with the KPK to promote fraud control through seminars and socialisation interventions.

The Association of Indonesia Local Health Offices (Asosiasi Dinas Kesehatan, ADINKES) also engages in advocacy, public awareness, and education programmes on fraud control. It has signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) with BPJS-K regarding fraud prevention through the ‘JKN series’, which involves socialisation interventions to prevent fraud in health services.

4.5. Public participation and open data

Public participation and open data are crucial for preventing and handling fraud. Based on our interviews with respondents, there is no mechanism for data sharing between agencies, and data on identified fraud risks has not yet been published. The MoH does not receive regular reports on potential fraud from participants, BPJS-K, or health facilities, nor does it publish regular reports.2cff866d85e7 In contrast, the United States publishes an annual report on potential fraud or fraud that has occurred, sanctions imposed, and public and private health plans, which is important for public knowledge and oversight.13190c8923a8

Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW), in collaboration with the LKPP, has created a platform called Opentender that provides open procurement data, including information on fraud risks. ICW has used potential fraud analysis, derived from corruption analysis, since 2004, and in procurement since 2008. All data provided in Opentender is derived from the public procurement agency, LKPP.ce8a10509215 The LKPP and Indonesia Procurement Watch (IPW) signed an MoU to conduct procurement through electronic procurement.1536d663e56e It covers medicine and equipment procurement and aims to minimise the potential for fraud.af031f5033a3

The Center for Health Policy and Management (PKMK) at the Universitas Gadjah Mada has initiated a community of practice that focuses on preventing and handling fraud in the JKN programme.e3f6fc112f9e The DJSN maintains an online dashboard that provides health insurance data as well as a monitoring and evaluation system in cooperation with BPJS-K, the Ombudsman, and non-governmental organisations (NGOs).b35b04892ebe

5. Gaps, challenges, and the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic

By September 2021, 4.23 million Indonesians had been infected with Covid-19, with 142,000 deaths.73a7908da346 The government is utilising JKN and BPJS-K as part of its pandemic response. Presidential Regulation No. 64 of 2020 redefined the contribution structure to improve compliance with dues payment. JKN participants who were in arrears could reactivate their membership by paying off what they owed within six months, and the rest were given leeway on their membership payments until 2021. BPJS-K is specifically assigned to verify Covid-19 claims, which are funded from the budget of the Indonesian National Board for Disaster Management (Badan Nasional Penanggulangan Bencana, BNPB) and the Ministry of Health, rather than from JKN participant fees. Furthermore, the government has optimised Covid-19 self-screening through the mobile JKN app and has put in place a new online consultation service (telemedicine) so that access to services at primary care centres becomes more accessible, faster, and more individualised. Lastly, BPJS-K introduced digital consultation services to reduce the transmission of Covid-19.cf6818c6d65b

The pandemic affected the JKN programme in several ways. First, participation by wage earners decreased from 91.20% in 2019 to 87.02% in December 2020, with a total membership deactivation of 1.06 million people due to high levels of layoffs in the formal and informal sectors. Second, JKN participants’ visits to both primary and referral facilities decreased, with visits to private practice dentists declining by 36.6% and visits to type D hospitals falling by 34.2%, to cite two examples.2a2c5cf8d292 Third, the potential misdiagnosis of Covid-19 cases meant that costs could be charged to JKN funds rather than to the government’s allocation package for handling Covid-19, or double claims could be issued. Lastly, the cost of health services decreased due to low utilisation during the Covid-19 outbreak.943a7baf5750

During the pandemic, new fraud risks have emerged and existing ones have increased. For example, data manipulation by primary health care centres has increased because the pandemic has made it harder to achieve performance targets on metrics such as number of visitors. This led some FKTPs to falsify data on visitation to claim that the target was achieved.eab020fed4be Referral hospitals are also vulnerable to fraudulent claims or double claims for Covid-19 services. At the hospital level, the risk of fraudulent reimbursement, service upcoding, double claims, and cloning increased.b1301e4781d8 For example, due to lack of standard fees for treatment and admission of Covid-19 cases, incidents of fraudulent overcharging increased at the points of service delivery.d92c179bf83f On top of that, some hospitals routinely made unnecessary referrals to higher-class hospitals (service upcoding).c71cdb263aff Fraud was involved in the reuse of Covid-19 antigen tests at Kualanamu International Airportand the hoarding of Covid-19 medicine.9fc6195c60af

There is also potential fraud related to medical supplies and medical equipment. For instance, markup of prices above the prices set in the procurement e-catalogue provides hospitals with an unfair advantage. The procurement process is vulnerable to this type of fraud in part because of the new requirement to negotiate prices.eafa536be694 Another risk is hospitals procuring medicine at the price set by the JKN but reselling it unlawfully to make a profit.1e2f0060f105

During Covid-19, because not all medicine and medical device entrepreneurs had registered their products through the e-catalogue, a consolidation tender was held. The consolidation tender brought together the device entrepreneurs within and outside the e-catalogue to issue revised quotations. The consolidation itself is contrary to the implementation of the e-catalogue and can undermine the system.

Due to the pandemic emergency, importers of medical devices could submit a recommendation letter which exempted them from the BNPB import rules regarding in vitro diagnostic, medical equipment, and household health supplies. They no longer require import licensing in the form of a distribution permit or Special Access Scheme permit from the MoH. This relaxation of the rules could lead to fraud if these medical goods are sold on the black market for a cheaper price.33d798277ff4

Fraud control efforts in the JKN programme at the central and regional levels, as well as in health facilities, may be delayed or not implemented because of the Covid-19 pandemic.94d0bbd2e1a1 The fraud prevention and control teams could not optimally carry out their roles because their members were deployed as health workers (doctors/nurses or vaccinators) in the pandemic response, or because their numbers were drastically decreased due to the impact of Covid-19.8ebccdaa1aae By September 2021, 2,029 health workers in Indonesia had reportedly died of Covid-19.7a0e038f883c

Another challenge has been the reallocation of financial resources in the local government from JKN fraud control programmes to pandemic response.58201b6c7f26 Lastly, lack of coordination among relevant agencies and unavailability of data on fraud make it difficult to ensure effective fraud control in the pandemic response.92219e93ccf6

6. Recommendations to strengthen anti-fraud measures in Indonesia’s national health insurance programme

Based on the findings, we recommend a number of strategies to reduce fraud risk in the JKN programme.

6.1. Improve the legal and regulatory environment

It is important to revise the law on the National Social Security System (Sistem Jaminan Sosial Nasional) by adding articles related to preventing, handling, and imposing sanctions for JKN-related fraud. This would include adding criminal sanctions that target fraud in the JKN programme. Other measures should ensure that regulations for preventing and handling fraud are binding on non-state entities.

Periodic reporting from BPJS-K to the MoH and other supervisory agencies regarding the potential of fraud and fraud incidents should be implemented. Additionally, BPJS-K and the MoH should provide detailed guidelines on how to conduct fraud risk management for each key actor in JKN at the operational level, based on the ISO 31000:2018 risk management guidelines.260f0534c646 Further advice on fraud risk management in the health sector is available in the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) health sector risk management approach, the Global Fund approach to corruption risk management, and the World Health Organization guidance for Member States on improving transparency and accountability in health systems.f6d18ddc24f7

A code of conduct or ethics for health service facilities, medical and health providers, and health professionals involved in JKN implementation would also help to improve self-regulation.

6.2. Streamline institutional roles and responsibilities and build the capacity of the anti-fraud teams

The Indonesian government needs to ensure that there are adequate operational resources to manage and sustain the anti-fraud programme in a more systematic and comprehensive manner. This should include development of the anti-fraud programme plans with appropriate fraud risk mitigation strategies.755d0c9c0ecb The anti-fraud teams should conduct fraud risk assessment systematically at national and local levels and at the level of health providers (FKTPs and FKTRLs). The district health offices should also be involved. Indonesia should establish an integrated reporting channel and an information-sharing mechanism to encourage cooperation and joint investigations among the different organisations involved in JKN programme implementation.

The United States provides a good example of how this can be achieved. The Healthcare Fraud Prevention and Enforcement Action Team (HEAT) performs a strategic role in preventing and prosecuting health care fraud in Medicare and Medicaid.b929bcaa737b They identify new enforcement initiatives and areas for increased oversight and prevention. State Medicaid Fraud Control Units play a critical role in the many fraud cases involving both Medicare and Medicaid. The Department of Justice (DOJ) and Department of Health and Human Services Office of Inspector General (HHS-OIG) have expanded data sharing and improved information-sharing procedures to get critical data into the hands of law enforcement, making it possible to track patterns of fraud. Both departments provide Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) compliance training for providers and HHS-OIG compliance programme guidance documents and training for providers. There have been ongoing meetings with the public and private sector and increased efforts to educate specific groups, including elderly and immigrant communities, to help protect them.a5acd0f07cf3

Leadership and management is critical to the successful implementation of an anti-fraud strategy.d5649c6e3472 To carry out their roles effectively, health sector leaders must be equipped with the skills and instruments to be able to detect and mitigate potential fraud. These leaders are expected to work proactively in fraud control efforts using the latest and most appropriate technology, such as electronic medical records.23ec08cced4b

6.3. Promote open data initiatives

Open data initiatives are important for minimising fraud.cfd37435806f They can encourage greater collaboration and identify inefficiencies, duplications, and errors that undermine public confidence in national health insurance programmes. Furthermore, the existence of a data-sharing programme and information can help policymakers formulate and develop new fraud control efforts in a timely and efficient manner, since the data they need is already available.964c4b4474d7

6.4. Set clear standards for health service delivery

The MoH, BPJS-K, and other concerned parties need to establish comprehensive national health care guidelines.fb62f65bec96 FKTPs and FKRTLs should establish standard operating procedures in accordance with the guidelines and MoH Regulation No. 1438/MENKES/PER/IX/2010 on medical service standards.465aefa5004d

6.5. Reform registration and identification

Indonesia could implement a biometric system through the BPJS-K card, following the model of Taiwan94602e04d057 and Ghana,5e6edce8b9cc to reduce forgery, identity theft, and false claims. BPJS-K should use data cross-checking to improve detection of fraudulent claims, potential inappropriate practices, and potential fraud, as has been done in Australia.56382426b97b

6.6. Provide education, training, and awareness raising

The respective organisations should establish anti-fraud awareness and training programmes for all relevant stakeholders, including JKN participants. The community of practice initiated by PKMK at the Universitas Gadjah Mada should be expanded to include a larger audience and more stakeholders from government, practitioners, and communities to discuss lessons learned and continuously improve anti-fraud interventions.

Indonesia could consider following the example of the United States, where the education and training programme is carried out by various parties, in cooperation and individually, including the CMS,492e454a443c HHS-OIG, National Health Care Anti-Fraud Association, and Drug Enforcement Administration. Education and training involves publishing and disseminating educational materials on fraud, disseminating fraud control guidelines, and assisting in the implementation of fraud prevention programmes. Training also covers interagency cooperation in data sharing and analysis of potential fraud cases, the detection and investigation of potential fraud cases, coding, and clinical documentation.

BPJS-K, as the main organiser, should provide an anti-fraud awareness toolkit to FKTPs and FKRTLs. Such a toolkit should explain how to detect and stop fraud, as well as how to file a report if someone becomes aware of fraud.b2bf5921c889 In addition, BPJS-K and the MoH can conduct online training programmes to ensure that practitioners meet health service standards.8808e7d1291d

6.7. Strengthen supervision, monitoring, and evaluation

Effective supervision, monitoring, and evaluation will help the respective organisations better prevent and deal with fraud. Efforts should be made to improve oversight by the DJSN through monitoring and evaluation and periodic reporting on fraud risks and incidents. The DJSN should collaborate with BPJS-K, the Ombudsman, NGOs, and other stakeholders such as trade unions to compile data and issue reports to BPJS-K, the relevant local government, and health facilities/providers.f75ec032f13a

6.8. Further research

Health service delivery is complex, and it is challenging to ensure evidence-based policy and action. Assessing the effectiveness of anti-fraud intervention can be even more difficult. While there are many studies on types and manifestations of fraud in national health insurance systems, few provide insights on the effectiveness and impact of anti-fraud measures. Further research is needed to improve the evidence base on the impact of anti-fraud measures in the Indonesian context. Such research could look at issues such as identification of health service tariffs (INA-CBG) according to the actual value of the cost of care/services and the impact of fraud awareness activities on reducing fraud. Also important are quantitative studies on the direct impact of fraud.

- Article 28H, unofficial translation.

- Presidential Regulation No. 111 of 2013 on health security.

- Co-payment is an additional fee paid by participants for obtaining a given service, based on Ministry of Health Regulation No. 51 of 2018.

- BPJS-K 2020a.

- All dollar figures in this report are US dollars. The Health Social Security Fund is considered secure if it has sufficient assets to cover estimated claims for the next 1.5 months, according to Government Regulation No. 84 of 2015 on management of health social security assets.

- Sunarti et al. 2020. The Indonesian Supreme Court in its judicial review accepted an applicant who argued that a deficit in JKN funds managed by BPJS-K is the result of errors and fraud in the management and implementation of the social security programme by BPJS-K.Mahkamah Agung RI. 2020. Decision No. 7P/HUM/2020.

- Ministry of Health Regulation No. 16 of 2019, Article 1(1), defines fraud as ‘an act that is carried out intentionally to obtain financial benefits from the health insurance programme in the National Social Security System through fraudulent acts that are not in accordance with the provisions of the legislation’.

- Halim 2014; Martini 2012.

- Anti-Corruption Clearing House 2017.

- Statistics Indonesia 2022.

- Ministry of National Development Planning 2019.

- Interview with KPK.

- Interview with Gakeslab.

- Annisa et al. 2020.

- Interviews with BPKP and private hospital in Surakarta.

- European Commission 2013.

- Vrushi 2020. The data is from Global Corruption Barometer Asia.

- Djasri, Rahma, and Hasri 2018.

- Nicholas et al. 2019.

- Wibowo et al. 2020.

- Integrity Indonesia 2019.

- Jakarta Post 2019.

- European Commission 2013.

- Interview with Gakeslab.

- Winda 2018.

- Interview with Gakeslab.

- European Commission 2013.

- Sukma, Sulistiyono, and Novianto 2018.

- Court Decision No. 74/Pid.Sus-TPK/2019/PN Sby.

- KPK 2020.

- KPK 2018.

- By contrast, the United States has a strong law regarding health insurance fraud, the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). It provides for the establishment of the Health Care Fraud and Abuse Control Program under the joint direction of the attorney general and the secretary of the Department of Health and Human Services.

- Ministry of Health Regulation No. 16 of 2019, Article 6(7).

- Interviews with IDI, PDGI, IPMG, and Gakeslab.

- Interview with a private hospital in Surakarta.

- Interview with a private clinic.

- Interview with a private clinic.

- Manafe 2019.

- JPNN 2019.

- Interviews with private hospital in Surakarta, BPKP, IDI, Serang District Health Office, IPMG, and Gakeslab.

- Interview with BPKP.

- Interview with BPJS-K.

- International Pharmaceutical Manufacturers Group 2021.

- Interviews with IPMG and Gakeslab.

- Interviews with IPMG and Gakeslab.

- Interview with KPK.

- Interviews with MoH and BPJS-K.

- Interview with MoH.

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Justice 2020.

- See the Opentender website (in Indonesian).

- MoU between LKPP and IPW No. 01-MoU/IPW/VIII/2015.

- Interviews with Gakeslab and IPMG.

- Universitas Gadjah Mada 2020.

- Interview with DJSN. The online dashboard (in Indonesian) is at sismonev.djsn.go.id/ketenagakerjaan/.

- Covid-19 Task Force 2021.

- BPJS-K 2020b.

- This data comes from an unpublished DJSN document reviewed by the authors.

- Situmorang 2020.

- Interview with a Puskesmas.

- Ministry of Health 2020. The potential for fraud in handling Covid-19 in hospitals was the subject of a presentation organised by the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners in Indonesia on 12 September 2020.

- Interview with Adinkes.

- Interview with a private hospital in Surakarta.

- Kompas 2021a, 2021b.

- Interview with IPMG.

- BPJS-K 2020b.

- Interview with Gakeslab.

- Interview with KPK.

- Business Standard 2021.

- LaporCovid-19 2021.

- Ministry of Finance 2020.

- Interview with MoH.

- International Organization for Standardization 2018.

- Hunter et al. 2020; Wierzynska et al. 2020; World Health Organization 2018.

- Hussman 2020.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2017.

- US Department of Health and Human Services and US Department of Justice 2020.

- Interviews with BPKP, Serang District Health Office, private hospital in Surakarta, Puskesmas and Paguyuban Puskesmas.

- Laursen 2013.

- Scrollini 2018.

- Governing Institute and Lexis Nexis 2016.

- Interviews with IDI and PDGI.

- Ministry of Health 2019.

- Jou and Hebenton 2007.

- Wang, H., Otoo, N., and Dsane-Selby 2017.

- Australian Government Department of Health 2021.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services 2021.

- NHS Counter Fraud Authority 2019.

- Australian Government Department of Health 2021.

- Interview with DJSN.