Blog

The anti-corruption community should become more ‘tribal’

Anniversary blog series

U4 staff and friends celebrate U4’s 20th anniversary with a blog series reflecting on developments and lessons learned in a world of ever evolving corruption challenges:

- U4 at 20: A quiet birthday at home with friends (across the world) – Peter Evans

- Specialised anti-corruption institutions: Measuring their performance and managing our expectations – Sofie Schütte

- The role of technology in anti-corruption: Dystopian reflections – Daniel Sejerøe Hausenkamph

- Strategic litigation and its untapped potential for anti-corruption – Sophie Lemaître

- The anti-corruption community should become more ‘tribal’ – David Jackson

- Corruption risk management in the aid sector: past, present, and the path ahead – Guillaume Nicaise

- Corruption is unaffordable for Latin America’s resurgent left: Democracy and lives are at stake – Aled Williams and Daniela Cepada Cuadrado

- Corruption is absent from the UN ‘World of Debt’ report – Daniela Cepada Cuadrado

- Anti-corruption games: Learning how to face corruption challenges – Guillaume Nicaise and Rachael Tufft

- a) Gender and corruption: What we’ve learned from 20 years of research (Part 1) – Ortrun Merkle and Ina Kubbe

b) Gender and corruption: Charting the course for the next 20 years (Part 2) – Ortrun Merkle and Ina Kubbe

And other blogs to come throughout 2023!

Sign up to the U4 Newsletter to get updates, or follow us on Twitter | Linkedin | Facebook.

Corruption has come into ever sharper focus over the past 20 years. Once seen as an off-limits issue in global economic and diplomatic relations, there now exists a broad consensus on what corruption is, why it needs to be tackled, and on the need for international collaboration to do so. The number of practitioners, international frameworks, and NGOs dedicated to anti-corruption has multiplied, as has the volume of research.

To some this may have become something of an overblown industry. To others, this is a ‘community of practice’ that, however imperfectly, is finding more effective ways to respond to demands for action on corruption voiced by publics. But within this community, are we all on the same page (or at least singing from the same song book)?

Big events, such as the International Anti-Corruption Conference, are often wrapped in narratives of the egregiousness of corruption, and attempt to convey the sense of the many united under one flag.

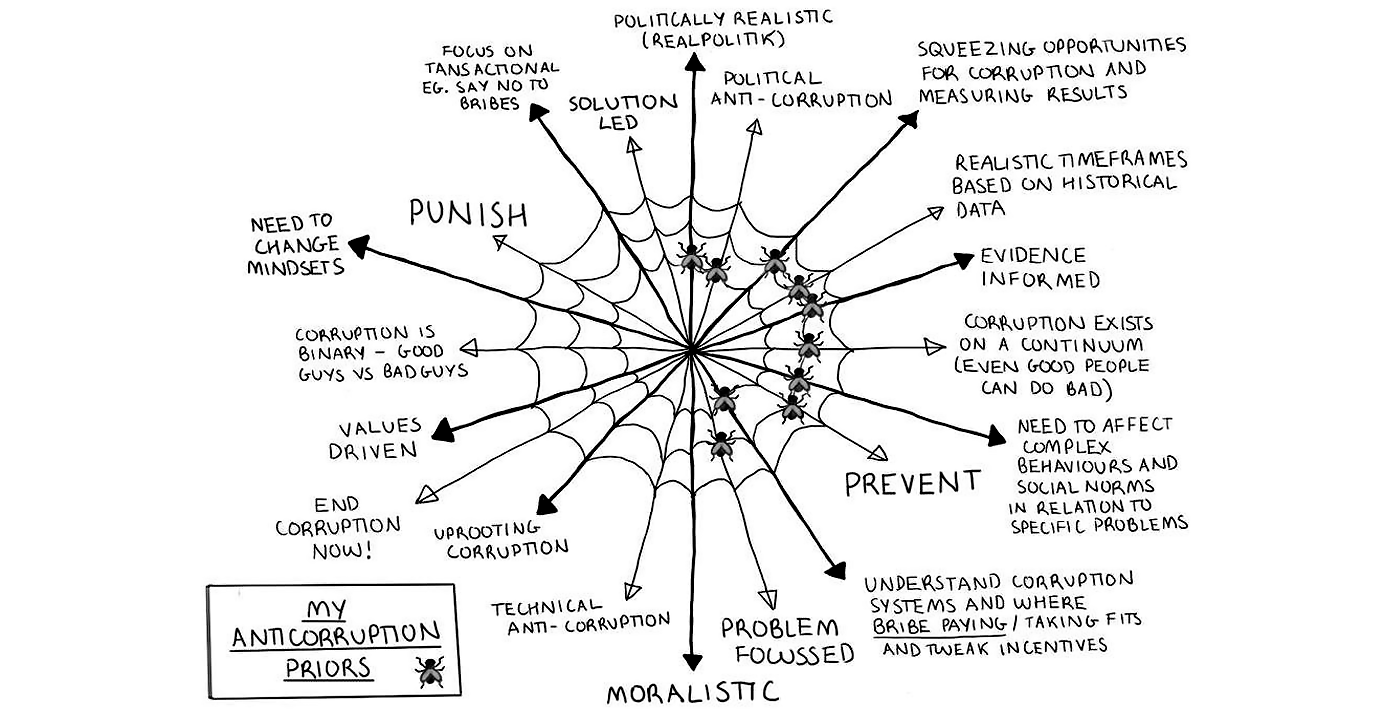

But perhaps the unity forged through acting against corruption conceals undeclared distinctions that are worth exploring. Peter Evans, U4 Director, noted how unconscious priors – the beliefs or uncertainties that we hold before we come to our problem – tend to be an ‘unspoken’ feature of the anti-corruption community. My own sense is that these different underlying assumptions reveal several ‘tribes’ (in the neutral sense) within anti-corruption.

From my own experience, from big gatherings to in-country discussions, I observe three main tribes in the community: practical innovators, realists, and activists. These tribes see things differently, want diverse things, view success in varying ways, and tend to prioritise different responses to corruption. Being more explicit about underlying differences is not a bad thing: it allows for a more vibrant debate. We just need to be more open and respectful about those differences.

This is armchair anthropology, of course, but perhaps there is a serious point: corruption – hidden, abstract, difficult to define – can be a hard topic to communicate, made harder by these differing perspectives being unspoken. Muddled dialogues may result. Even worse, uncertain of where others are coming from, we may play safe in our discussions, leading to ‘groupthink’.

The three tribes of the anti-corruption community

Practical innovators

Practical innovators are generally interested in the evolution of practice: new digital tools, open data, better measurement, more refined standards, and sophisticated risk management. For this tribe, success is often viewed in terms of technical innovation: corruption is best addressed through smarter approaches.

Practical innovators have advanced the anti-corruption agenda considerably in the past twenty years: the ‘toolbox’ has acquired many new compartments and bespoke instruments.

Activists may see the practical innovators as too caught up in the technical, while underestimating the importance of passion, justice, and social action: voices, campaigns, demonstrations, and politicking. Realists may criticise practical innovators for being too focused on ‘best practice’, allowing plans to run ahead of what is actually feasible and likely to be effective in a particular context. They also may argue that practical innovators have no answers to questions around the roots of corruption, such as imbalances in power.

Realists

Indeed, realists take a sober perspective on corruption, seeing it as something socially embedded and therefore almost impossible to eliminate completely. According to this view, it may not be necessary to address all corruption: some can be navigated without fundamentally threatening things that matter, like economic growth. Transitioning away from corruption is for the long term, a never-ending journey: small wins, piecemeal reforms, and serendipitous change (reduced corruption without explicit anti-corruption) are better than, for example, the development of elaborate anti-corruption rules or powerful enforcement institutions with little payoff, or worse – ‘performative’ anti-corruption. Realists emphasise the need for evidence-led and politically feasible reforms.

Realists therefore tend to be allergic to action for the sake of it. Realists have been an important corrective to the more ‘solution-led’ anti-corruption present in the last two decades. They bring clarity on what can and cannot be effective in certain contexts.

Practical innovators meanwhile may view realists as being overly pessimistic or obsessed with ‘context, context, context’. Activists may see realists as stripping anti-corruption of moral clarity.

Activists

Activists view corruption through the lens of social justice. They voice why we should care, emphasising anti-corruption as a route to fairness. Activists work mainly through public advocacy, campaigns, and direct action. The need for effective whistleblowing and transparency are common themes. Success stories often relate to individuals: triumphs are when the corrupt are held accountable, brought to justice, punished. Activists have been crucial in sustaining anti-corruption in the public eye, often bravely energising action in difficult places. Many times they have acted at critical moments to push reforms over the line.

Realists may contend that activists have too much faith in the public to be agents of change, and that they ignore things like ‘corruption functionality’ where vulnerable people use corruption to solve everyday problems. Practical innovators may argue that long-term accountability can only come about through having the right systems and measures in place.

Table 1: Know your tribes

|

Tribe |

Basic view on corruption |

What do we need more of in anti-corruption? |

What do we need less of? |

Success is… |

|

Practical innovators |

Technical problem |

Innovation in practice |

Endless contextual considerations! |

The adoption and implementation of better practice |

|

Realists

|

Social and political problem |

Aligning interventions with what is feasible in very specific contexts |

Standardised practice! |

Minor victories Pushing local reforms ‘over the finishing line’ |

|

Activists

|

Social justice problem |

Public voices against the corrupt Transparency Prosecutions |

Shiny new tools! |

Corrupt held accountable and brought to justice |

Should anti-corruption be more tribal?

The tribes described here are highly stylised and may not be identifiable by everyone. Perhaps we can belong to all three, or change over time: I must say I probably started off more of a practical innovator but am becoming more realist over time. I find, perhaps paradoxically, it’s easier to be optimistic starting from a more realistic perspective. I am in constant admiration of the courage of activists.

A 2020 U4 Issue reviewing theories on How change happens in anti-corruption shows that there is no one blueprint for the transition from high to low corruption. The paper argued that additional approaches beyond the ‘state modernisation paradigm’ – for example, indirect, targeted, nurturing norms, big bangs, and transnational approaches – are increasingly important. Hence we should build on each other’s strengths, recognise how they complement one another, and work as a team:

- Practical innovators strengthen anti-corruption’s muscles.

- Realists are most sensitive to constraints and the most credible opportunities.

- Activists establish a purity of principle.

More tribalism – a more explicit reflection on operating assumptions, what counts as success, as well as strengths and weaknesses – can bring out the best from those working on anti-corruption.

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)