Blog

Goodbye government, hello corruption

This post was first published on the Oxfam blog From Poverty to Power, edited by Duncan Green.

In December 2021 I left the UK Government after 20 years as a governance adviser, and then research commissioner, and became Director of the U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre in Norway. After 20 years of being a ‘flexpert’, spread thinly across multiple issues, I wanted to zero in on corruption because tackling it is a means to many bigger ends. It’s a major constraint (but not the only governance constraint) to delivering ‘development outcomes’, changing real lives, and maximising bangs for bucks, in health, education, climate change – everything.

The ‘anti-corruption community’ is a specialised niche, but my heart is in sectors – I would rather help others (you?) to understand corruption in your sector, use evidence, and invest your own time and budget to do something about it. U4 has been doing exactly this for 20 years – health, natural resources, and climate are some of our most prominent and enduring areas of work – and impact.

Dirty politics too!

I feel the same about getting to grips with the real politics in any sector – including broadcasting the value of practical political economy research.

I try to persuade sector people to understand and tackle political barriers to change, and (again) invest their time and budgets in this – not see politics as someone else’s problem, or bemoan #LOPW (Lack Of Political Will).

Credit: Peter Evans by-nc-nd

Bad politics and corruption are, of course, connected, and ideally are addressed together. Is doing this expensive? Not really, if compared with the budgets wasted if corruption and bad politics go unchecked.

A calculation by SOAS ACE estimated the cost of researching politically viable anti-corruption strategies in the garment sector in Bangladesh was GBP 130k – for a sector in which donor investment was $1Bn.

Did my arguments work in DFID?

Not really, though ACE’s sector research (funded under the governance research budget) had good traction, and the importance of politics (elites, bargains) in development has been boosted by the new book by ex-DFID Chief Economist Stefan Dercon.

Talking money: how much of my sector budget should I spend on this stuff?

This idea that every sector should grip its own corruption risks and politics, and invest in anti-corruption, leads to awkward questions that donors, civil servants, and politicians try to avoid:

- If you have a sector or programme budget of 1000 dollars, how much of this is likely to be lost to corruption?

And a follow up: - How much of your 1000 dollars should you allocate (or ‘earmark’) to understand and tackle the corruption in Q1?

This is not just about aid. Whether you are a government ministry, World Bank, NGO, or donor, corruption losses are hard to estimate, sensitive to discuss, and no one likes doing either. But for reference: a World Bank paper (2020) estimated an implied leakage rate in aid of 7.5%.

Corruption? Systemic, innit.

And this is not about just money wasted and outcomes denied. Not just ‘accounting losses’.

Leaky sector budgets are a corruption accelerant and feed ‘systemic corruption’ – re-fueling bad politics, incentivising policy capture and resistance to reform by those that benefit from the messy status quo. LoPW? More like active political won’t.

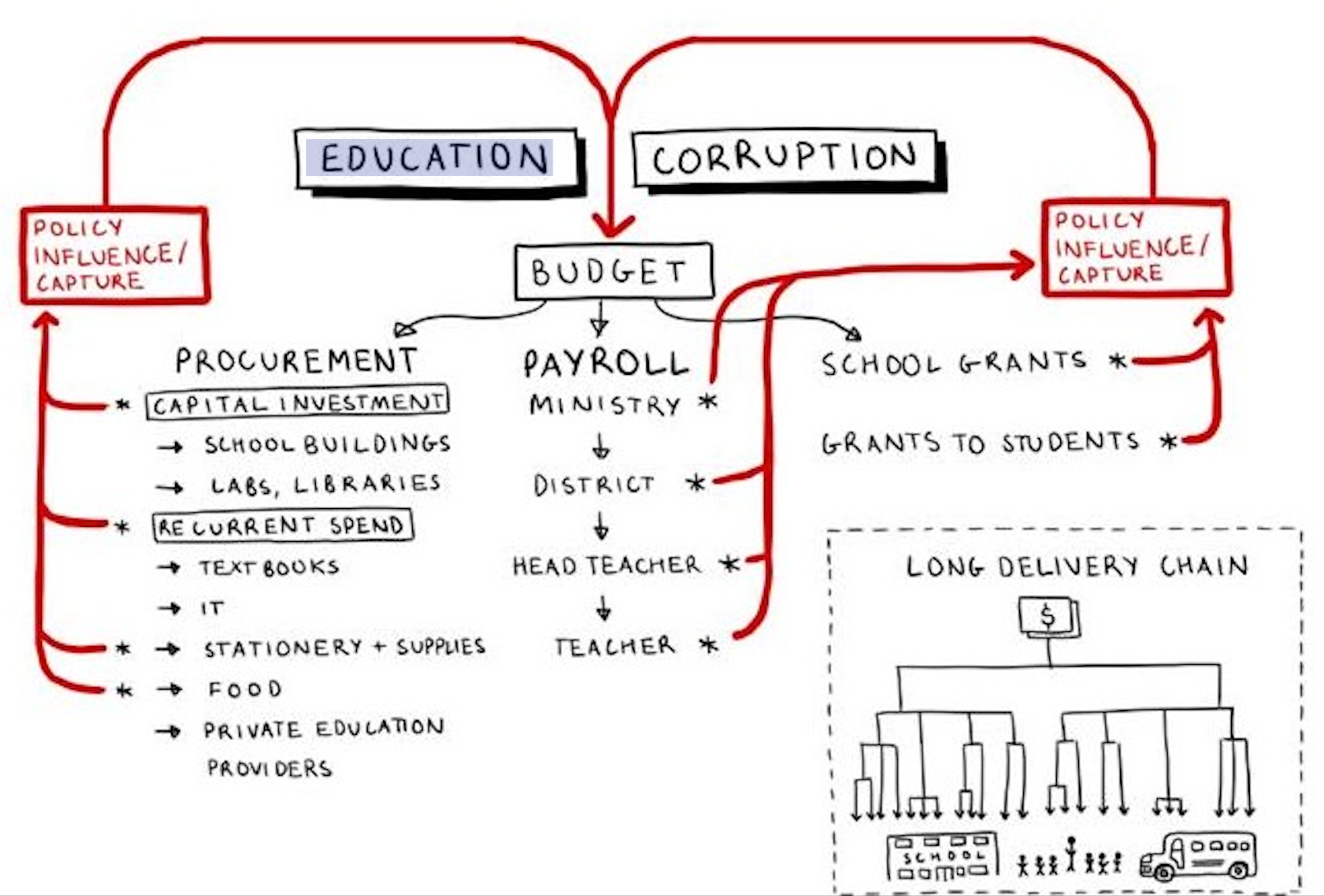

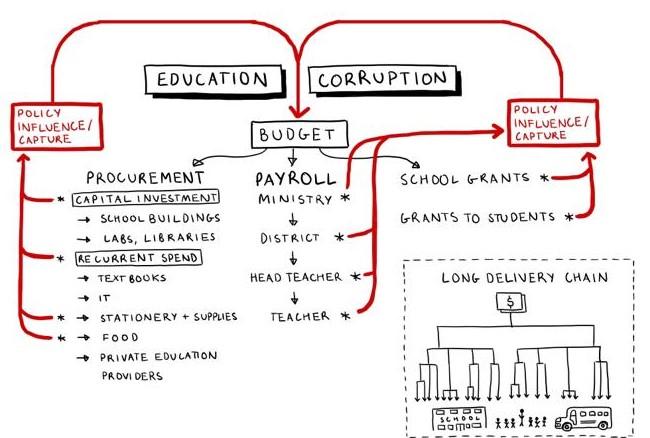

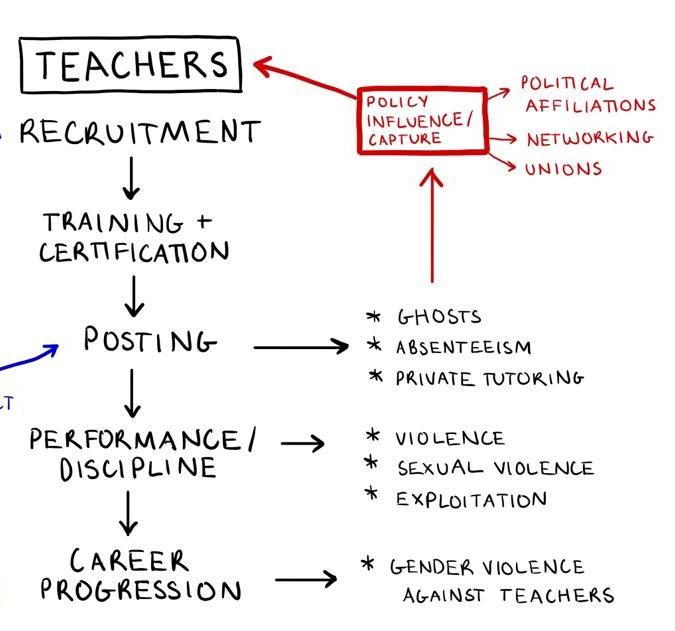

As an example, the red lines in this sketch (work in progress) attempt to capture systemic corruption flows in a typical education sector, drawing on U4’s education research.

Corruption is not just money wasted...Corruption fuels bad systems: bad policy ('policy capture'), bad politics.

Credit: @hamsiiidris

Leaking funds at multiple levels sustain power relations, compromise many in the sector who are forced to pay up or suffer, and so perpetuate impunity (no one is truly innocent, so no-one can speak out) and resistance to regulation and reform. And impunity for corruption probably means impunity for other things – such as sexual exploitation.

Credit: @hamsiiidris

Leaks also cross borders, feed Illicit Financial Flows, and perpetuate the global systems that enable these. Unintended consequences writ super large.

So, corruption is even nastier than you thought.

Let’s talk anti-corruption budgets.

OK – so how much is enough? Too much?

The idea of putting a number, or percentage, on the amount to spend on anti-corruption in a sector is also difficult and uncomfortable.

It’s has been easier to say that anti-corruption is mainstreamed, without a budget. However, as with gender, mainstreaming risks evaporation. Everybody’s problem is nobody’s problem; and we fall back on generic, technical corruption safeguards. And ignore the politics.

Another donor strategy is to say ‘as well as this sector programme in country x, we also fund accountability, governance, transparency, civil society’. At country level, this begs the question ‘what is the right budget for this work?’. And also (internal voice) ‘does that governance stuff actually address corruption risks and bad politics in this sector, and within the timescale of this sector programme?’ As a donor I often doubted it.

Of course, earmarking sector budgets smacks of conditionality. And conditionality has generally been found to be ineffective. Aid effectiveness purists dislike it (for good reasons). Those enmeshed in the political economy of aid-giving are probably more resigned to it.

Regardless, I think the question is still worth chewing on: what would be the right amount to spend on anti-corruption in any big sector? Health? Education? Climate finance?

My colleague David Jackson asked just this as a recommendation in a new paper on anti-corruption and accountability in Ukraine’s future reconstruction, co-written with Chatham House. A U4/TI helpdesk report on earmarking for anti-corruption is also imminent (spoilers – there are some private sector rules of thumb, but very little data from aid).

We may not end up with a perfect number, but hope to stimulate this irritating but important debate in your sector.

Are you doing and spending enough?

Disclaimer

All views in this text are the author(s)’, and may differ from the U4 partner agencies’ policies.

This work is licenced under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)