Origin of the anti-corruption courts

Corruption in Zimbabwe, as in many other countries, is both endemic and institutionalised. Consisting of both petty and grand/political corruption, it is one of the major developmental challenges facing the country. Zimbabwe scored 24 points out of 100 and ranked 157 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s 2020 Corruption Perceptions Index. Perceptions are high that corruption runs rampant in Zimbabwean society, partly due to the impunity that surrounds cases of grand and political corruption. Therefore, after the 2017 ouster of President Robert Mugabe, who had ruled the country for 37 years, expectations likewise were high that corruption would be dealt with decisively. Citizens especially hoped to see perpetrators of grand corruption prosecuted.

The Constitution of Zimbabwe (No. 20) Act 2013 establishes the Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission (ZACC) and the National Prosecuting Authority (NPA) as the main institutions mandated to counter corruption in the country. In an effort to strengthen anti-corruption measures, since 2017 the government of Zimbabwe has adopted additional anti-corruption policy and institutional frameworks. These include the Special Anti-Corruption Unit (SACU) and a set of new, specialised anti-corruption courts.

The SACU, which is housed in the Office of the President and Cabinet, was established by President Emmerson Mnangagwa in 2018 to ‘improve efficiency in the fight against all forms of corruption and to strengthen and improve the effectiveness of the national mechanisms for the prevention and fight against corruption’.3153476a0a51 Its terms of reference are not widely known, leaving its mandate somewhat unclear. This has led to criticisms that the SACU duplicates the mandate of other state anti-corruption agencies, such as the ZACC and NPA, since it also investigates and prosecutes corruption cases. Furthermore, questions have been posed with regard to the legality and independence of the SACU, as its establishment is not supported by any statute or law. In 2018, the prosecution powers granted to members of SACU by the prosecutor general were challenged in court by the former University of Zimbabwe vice chancellor, Professor Levi Nyagura.9add3b278119 However, the court aquo ruled that the prosecutor general’s granting of prosecutorial authority to members of the SACU was within the ambit of the law, specifically section 5(2) of the Criminal Procedure and Evidence Act [chapter 9:07].

In the same year, anti-corruption courts were established as a pilot project in the country’s two major cities, Harare and Bulawayo. In his speech at the official opening of the 2018 legal year, Chief Justice Luke Malaba pointed out that the courts were being established in order to ‘deal with corruption-related cases expeditiously’. Similarly, a key informant from the Judicial Service Commission (JSC) noted that the decision to set up the specialised courts was an administrative move to combat corruption and deal with graft cases promptly, effectively, and efficiently. As of December 2020, the anti-corruption courts have been established in all of the country’s ten provinces, mostly at magistrate level.

Institutional setup: Hierarchy and jurisdiction

The specialised anti-corruption courts are part of the general court system and the criminal justice system; the only distinction is that they deal mainly (though not exclusively) with corruption-related cases. They are therefore bound up with the functioning of the general court system. A key informant from the Ministry of Justice explained that the anti-corruption courts ‘are just like any other criminal court dealing with any other offence. The only mark of distinction is that, in the current environment and government policy, they have been set aside to deal with and prioritise corruption and related offences.’

When not handling corruption cases, these courts hear other matters. Nonetheless, a majority of citizens hold the view that the courts were established for the sole purpose of hearing corruption cases only. This, according to a representative from the Law Society of Zimbabwe, reflects the fact that ‘there was no significant public debate on the establishment of the courts’, or on the expertise of prosecutors to prosecute corruption cases, and thus ‘it may be argued that they were established prematurely’.

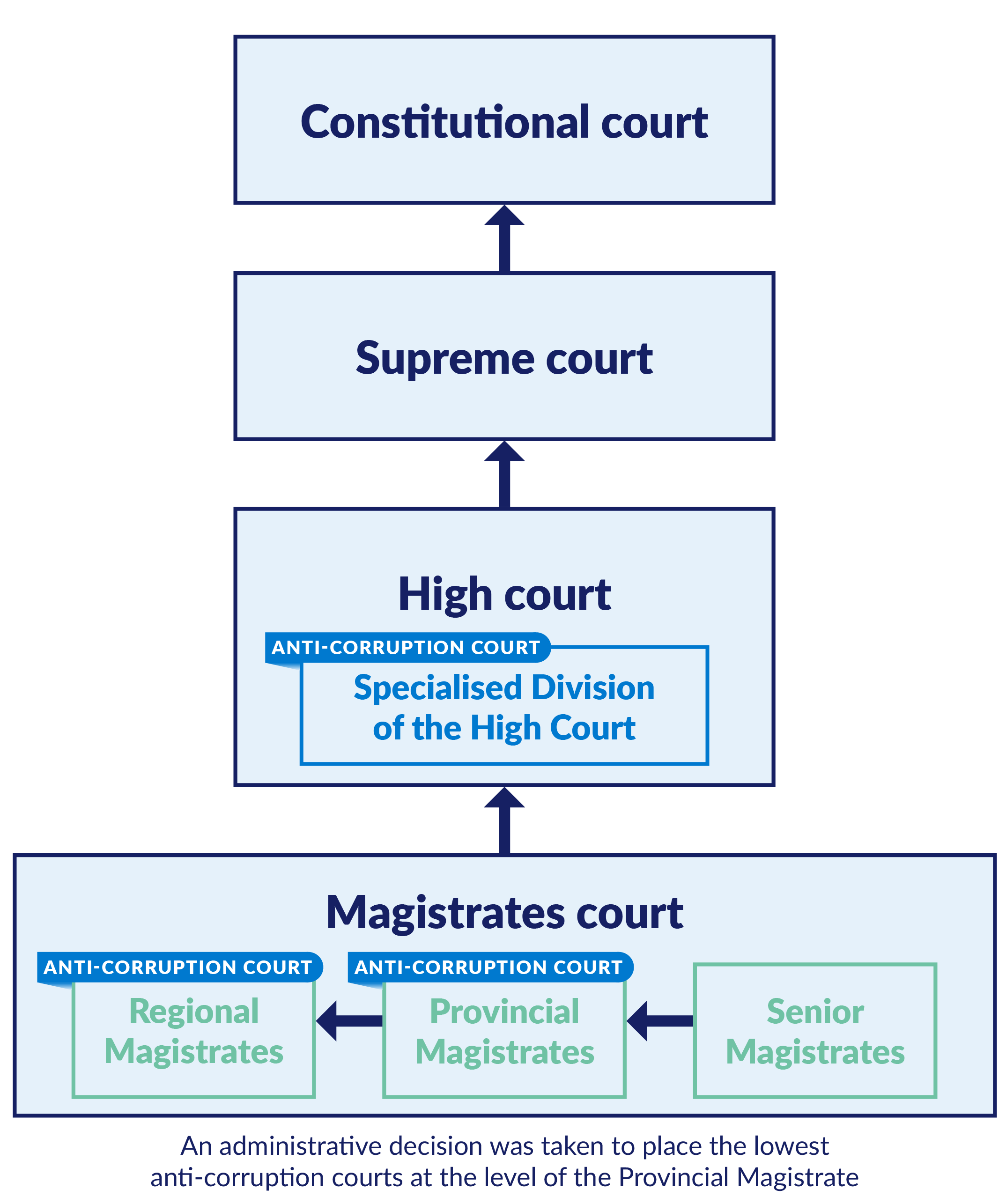

The anti-corruption courts were created as a specialised division of the High Court under section 46A of the High Court Act [chapter 7:06]. This law gives the chief justice (after consultation with the judge president) powers to create specialised divisions of the High Court in accordance with section 171(3) of the Constitution. However, the JSC took an administrative decision to place the lowest anti-corruption courts at the level of the provincial magistrate. Therefore, the prosecutor general has the discretion to choose which level of court should hear a particular corruption matter after considering the nature and circumstances of the corruption-related offence that has been charged. The main consideration is the range of punishment that the particular offence is expected to attract.

In this regard, the anti-corruption courts situated at the Magistrates Court are governed by the ordinary sentencing jurisdiction of the different levels of magistrates, as provided by section 50 of the Magistrates Court Act [chapter 7:10]:

- Court of the Provincial Magistrate: fine of up to level 10, or 5 years imprisonment.

- Court of the Regional Magistrate: fine of up to level 12, or 10 years imprisonment.

According to the standard scale, a level 10 fine is currently pegged at ZWL$ 24,000, while a level 12 fine is pegged at ZWL$ 36,000 (about US$ 272 and US$ 409 respectively). A level 12 fine is the maximum that can be imposed at magistrate level, with certain defined exceptions. Where the offence requires greater punitive jurisdiction, the indictment may be moved to the High Court division of the anti-corruption courts. Judges who preside over anti-corruption courts at the High Court have unlimited sentencing jurisdiction, subject to the maximum permissible sentence prescribed by the offence-creating provisions, in addition to their review and appellate jurisdiction. For example, if a person is found guilty of the criminal offense of bribery as defined in section 170 of the Criminal Law (Codification and Reform) Act [chapter 9:23], they can be subject to a level 14 fine of ZWL$ 120,000.

Figure 1. Hierarchy of the courts dealing with criminal matters in Zimbabwe

In both levels of anti-corruption courts, those situated at the Magistrates Court and at the High Court, a single judicial officer presides over each trial, unless it is an appeal from the Magistrates Court to the High Court. Cases from the Magistrates Court sitting as an anti-corruption court can be appealed to the High Court sitting as an anti-corruption court. However, cases from the latter can be appealed at the Supreme Court, which is not specialised. As noted above, when not presiding over corruption matters, judicial officers seconded to anti-corruption courts preside over other matters of a civil or criminal nature. In this regard, the specialised anti-corruption courts do not offer exclusive specialisation in the truest sense of the word, although at the Magistrates Court, there are certain courtrooms labelled ‘Anti-Corruption Court’.

Appointment and removal of judicial officers presiding over anti-corruption courts

There are no separate procedures for the appointment and removal of judges or magistrates presiding over cases in the specialised anti-corruption courts. They are appointed in the same manner as judges and magistrates presiding over any other cases (in accordance with sections 180 and 182 of the Constitution, respectively). A judge may be removed from office for the inability to perform the functions of their office due to mental or physical incapacity, gross incompetence, or gross misconduct in line with section 187 of the Constitution. For magistrates, the Judicial Service Regulations, 2015 and the Magistrates’ Code of Ethics, 2019 stipulate the circumstances that may lead to dismissal from office.

A key informant from the JSC stated that as a matter of practice, judges seconded to anti-corruption courts are selected from a pool that has undergone training on presiding over corruption cases. Magistrates, on the other hand, are mandated to preside over anti-corruption cases based on their expertise and experience in handling other criminal matters. There are currently seven magistrates and four judges seconded to the anti-corruption courts at the Harare Magistrates Court and Harare High Court, respectively.

Performance of the specialised anti-corruption courts

Statistics obtained from the JSC reveal that country-wide, the Anti-Corruption Court Division of the High Court received 66 matters in 2020. As of 31 December 2020, 52 of these had been completed. The Magistrates Court received 91 corruption matters, and as of 31 December 2020, 81 cases had been completed.This amounts to clearance rates of 79% and 89% respectively.

Tables 1 and 2 give an overview of how the cases were disposed of at the respective courts. While one can argue that these statistics illustrate the efficiency and effectiveness of the specialised courts, expert critics and ordinary citizens alike have pointed to the failure of these courts to conclude cases of corruption involving high-profile public officials, such as former minister Prisca Mupfumira and former minister Obediah Moyo, within a reasonable time frame. Critics have also noted that in a country with an apparently high level of grand corruption – as exposed by, among others, the auditor general in her annual reports – the anti-corruption courts should not be inundated with corruption cases that are deemed petty. Rather, these courts should focus on responding to perceptions of impunity in cases involving senior public officials and politically exposed persons, while other corruption cases are dealt with in the ordinary criminal courts.

Table 1. Overview of completed corruption cases heard by the High Court Anti-Corruption Division

| Convictions | 34 |

| Acquittals | 3 |

| Struck off | 9 |

| Withdrawn | 1 |

| Dismissed for want of prosecution | 5 |

| Total | 52 |

Table 2. Overview of completed corruption cases heard by the Magistrates Court Anti-Corruption Division

| Convictions | 23 |

| Acquittals | 19 |

| Withdrawn before plea | 7 |

| Further remand refused | 32 |

| Total | 81 |

Data for both tables provided by the Judicial Service Commission.

Early challenges

The establishment of the anti-corruption courts has been viewed as signalling a more focused and institutionalised approach that will significantly improve Zimbabwe’s ability to adjudicate corruption cases. However, there are early challenges that have the potential to impede the courts’ performance, as discussed briefly below.

Independence of the judiciary

An independent judiciary is central to the rule of law and to the impartial adjudication of corruption cases. The Constitution of Zimbabwe explicitly provides for the independence of the judiciary (section 164) and sets out clear procedures for the appointment and dismissal of judicial officers. However, formal rules alone do not guarantee that appointments will be free from political interference. Furthermore, in instances where appointments are made purely on merit, judicial officers might not be free to exercise their duties and functions impartially. This has been the case in Zimbabwe, where citizens generally believe that the executive tends to influence judges and magistrates and often interferes in politically contentious issues.aed513a89514 Moreover, critics have expressed concern about politically motivated prosecutions, pointing out that the only high-profile corruption cases prosecuted to finality appear to involve individuals who have fallen out of favour with the executive.

While stakeholders in the judicial system may downplay such perceptions, they nevertheless have a negative effect on citizens’ confidence in the anti-corruption courts. It is therefore important that remedial action be taken to address political interference and other forms of judicial corruption, whether real or perceived. Barrettacbd7006299d correctly opines that the effect of perceived corruption should not be underrated, as corrective measures require both ‘marketing a non-corrupt image and rebuilding the legitimacy of, and confidence in, the system’.

Delays in concluding cases involving senior public officials

One of the objectives for the establishment of the specialised courts was to deal with corruption-related cases expeditiously. However, cases of corruption, especially those involving political elites and politically exposed persons, seem to be taking a long time to conclude, for various reasons. For instance, the former minister of health, Obediah Moyo, first appeared in court on 20 June 2020 on allegations of corruption in public procurement. However, his matter is still pending. Similarly, former minister Prisca Mupfumira, who is facing various allegations of corruption, initially appeared before the courts on 26 July 2019. Almost two years later, her matter is also yet to be finalised. Delays in completing cases of this nature contribute to lack of public confidence in the ability of the anti-corruption courts to address impunity.

The Zimbabwe Anti-Corruption Commission and some anti-corruption activists say that key procedural weaknesses provide opportunities for delays in concluding cases. These include the rights afforded to accused persons to file various processes that in some cases suspend the continuation of trials. For instance, lower courts in Zimbabwe lack jurisdiction to adjudicate constitutional matters. Therefore, if an accused person appearing at the magistrate-level anti-corruption courts raises a constitutional argument, the matter will be referred to the High Court1fec6ab94655 or Constitutional Court, with proceedings at the Magistrates Court suspended.

Some critics suggest that delays could be curtailed by amending or creating new Rules of Court for anti-corruption courts to prescribe a time limit within which corruption cases must be dealt with. Proponents of this view state that corruption matters should be disposed of within six months, as is currently the position with electoral petitions (section 182 (1) of the Electoral Act [chapter 2:13]. However, it is important to note that while valid concerns exist regarding the timely completion of corruption cases, efforts to resolve cases expeditiously should not curtail the rights of accused persons, such as the rights enshrined in sections 69 and 70 of the Constitution. Furthermore, prescribing time frames without a thorough diagnosis of what is causing the delays might not address the real difficulties. The length of any trial is affected by the interactions between various stakeholders in the criminal justice system, including prosecutors, judicial officers, defence counsel, and investigators. Therefore, input as to what is a reasonable time frame should be sought from relevant stakeholders. The amount of resources channelled towards the functioning of the anti-corruption courts also influences their efficiency in disposing of corruption cases. In this regard, Stephenson and Schütteb5a4a5952cd7 rightfully caution against viewing imposing deadlines as a panacea that would speed up prosecution of corruption cases.

Expertise and capacity of stakeholders

Corruption is by its nature a complex and technical crime. Therefore, while Zimbabwe has judicial officers and prosecutors with adequate skills and competencies to adjudicate and prosecute criminal cases in general, there is a need to build the capacity of all stakeholders who deal with anti-corruption cases. These include investigators, prosecutors, magistrates, and judges. In 2018, the International Commission of Jurists with funding from the European Union joined forces with the Judicial Service Commission to convene an anti-corruption capacity-building workshop for judicial officers. It would be useful to extend the same capacity-building initiatives at a similar scale to investigators and prosecutors.

A key informant from the Ministry of Justice stated that judicial officers assigned to deal with anti-corruption matters have so far been handling the cases presented to them with commendable alacrity. However, some stakeholders noted that the performance of the anti-corruption courts is hampered by the quality of investigations and prosecution. A perusal of corruption cases dealt with by the courts also points to the need to strengthen the capacity of prosecutors and investigators. For instance, in S v Mubaiwa, a case in 2020, the judge made the following remarks:

‘The State is the dominant litigant in the prosecution of cases at public instance. It is in charge of investigation and timeous prosecution of crime. There is no point in commencing a prosecution without the necessary seriousness to start the trial. Trials have been delayed by postponements to complete investigations or failure to prefer correct charges or add alternative charges or failure to serve the person accused with relevant state papers or attending to interlocutory matters that could be anticipated by the State. The fight against corruption cannot be achieved through detention without trial or pre-trial incarceration.’

This view was supported by a key informant from the Law Society of Zimbabwe, who stated that before the courts were set up, there was a need to first capacitate the officers in charge of the technical operation of the courts. A well-equipped prosecutorial authority would better complement the specialised courts. This provides an opportunity for development partners and civil society organisations to contribute to the realisation of the courts’ objectives by strengthening the capacity of investigators and prosecutors.

Coordination of stakeholders

The success of the anti-corruption courts also hinges on the effective coordination of anti-corruption agencies including the police, ZACC, NPA, and SACU. However, the diversity of these institutions along with their intersecting mandates, competing agendas, and varying levels of independence makes it difficult to coordinate their efforts. This lack of coordination has at times resulted in the arrest of each other’s state witnesses. Such incidents should serve as an impetus for the country to develop and adopt comprehensive whistle-blower and witness protection legislation and institutional frameworks. Currently, whistle-blowers are only afforded protection under section 14 of the Prevention of Corruption Act [chapter 9:16], which criminalises the victimisation of whistle-blowers but does not provide institutional modalities for their safety.

Conclusion and key recommendations

The establishment of specialised anti-corruption courts in Zimbabwe is a positive step in the adjudication of corruption cases. However, it is crucial to adopt measures that will further strengthen the anti-corruption courts and their contribution to the broader anti-corruption agenda. Among the recommendations:

- Build the capacity and expertise of investigators, prosecutors, and the judicial officers who operate the anti-corruption courts.

- Strengthen the framework for coordination between state anti-corruption agencies.

- Develop and adopt comprehensive whistle-blower and witness protection legislation and establish the necessary institutional frameworks.

Over and above these recommendations, it is critical that steps be taken to ensure the judicial and prosecutorial independence of the anti-corruption courts, as defined in the Constitution. For many Zimbabweans, the true measure of the courts’ success will be their record in countering impunity in cases involving corrupt senior public officials and political elites.

- OPC 2018; see also Maodza 2018.

- Taruvinga 2018.

- Magaisa 2016.

- 2005: 2.

- In terms of section 171(1)(c) of the Constitution of Zimbabwe (No. 20) Act 2013, the High Court may decide constitutional matters except those that only the Constitutional Court may decide.

- 2016:7.