Why and how the HACC was established

On 7 June 2018, after a lengthy political struggle, the Ukrainian parliament, known as the Verkhovna Rada, enacted a law creating a High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC). This specialised judicial body, with nationwide jurisdiction over high-level corruption cases, began operations in September 2019. This brief discusses the history and rationale for the HACC, its most distinctive features, and some of the challenges it will face.

Since Ukraine regained its independence in 1991, it has been plagued by pervasive corruption. Following the 2014 Maidan Revolution, Ukraine launched a comprehensive institutional reform project that included the creation of four new anti-corruption bodies: (a) the National Anti-Corruption Bureau (NABU), which investigates high-level corruption cases; (b) the Specialized Anti-Corruption Prosecutor’s Office (SAPO), an independent unit within the Prosecutor General’s Office that oversees NABU’s investigations and prosecutes its cases; (c) the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption (NAPC), which administers the asset declaration system and participates in anti-corruption policy making; and (d) the Asset Recovery and Management Agency (ARMA), which focuses on recovery of stolen assets. These new prosecutorial and investigative units have not been as successful as many hoped. Ukraine’s regular courts are notorious for their corruption and susceptibility to political pressure; even when judges act in good faith, it can be hard for these overburdened judges, dispersed all over the country, to process corruption cases expeditiously.

In response, Ukrainian activists advocated creating a specialised anti-corruption court (Kostetskyi 2017; Anti-Corruption Action Centre 2016). The 2016 Law on the Judiciary and Status of Judges authorised the creation of a HACC but did not provide specific terms for its adoption, and for several years the political establishment resisted calls to create this court. Then-president Petro Poroshenko initially argued that Ukraine should instead focus on nationwide anti-corruption and judicial reform, or perhaps on the creation of specialised anti-corruption chambers within existing courts. Ukrainian anti-corruption activists, although supportive of broader judicial reform, viewed this as inadequate. Under pressure, Poroshenko eventually proposed his own HACC bill in late December 2017, but that bill was criticised as too weak.

Anti-corruption activists maintained a vigorous advocacy campaign for a robust HACC, enlisting the support of international actors like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the European Union (EU), the World Bank, and other donors (Krasnosilska 2017). These bodies, though initially reluctant, became indispensable drivers of the effort to create the HACC. Crucially, domestic advocates convinced the IMF to make the HACC’s establishment a condition for Ukraine to receive $1.9 billion in funding (Kaleniuk 2019). Additionally, in its September 2018 memorandum of understanding with Ukraine, the EU similarly conditioned financial assistance on creation of the HACC. Attempts to water down the proposals were strongly opposed by the IMF and the European Commission for Democracy through Law, known as the Venice Commission. Parliament adopted a draft law on the creation of the HACC in March 2018, and after three months of deliberation, enacted the law in June 2018.18309dfc6594

Key characteristics of the HACC

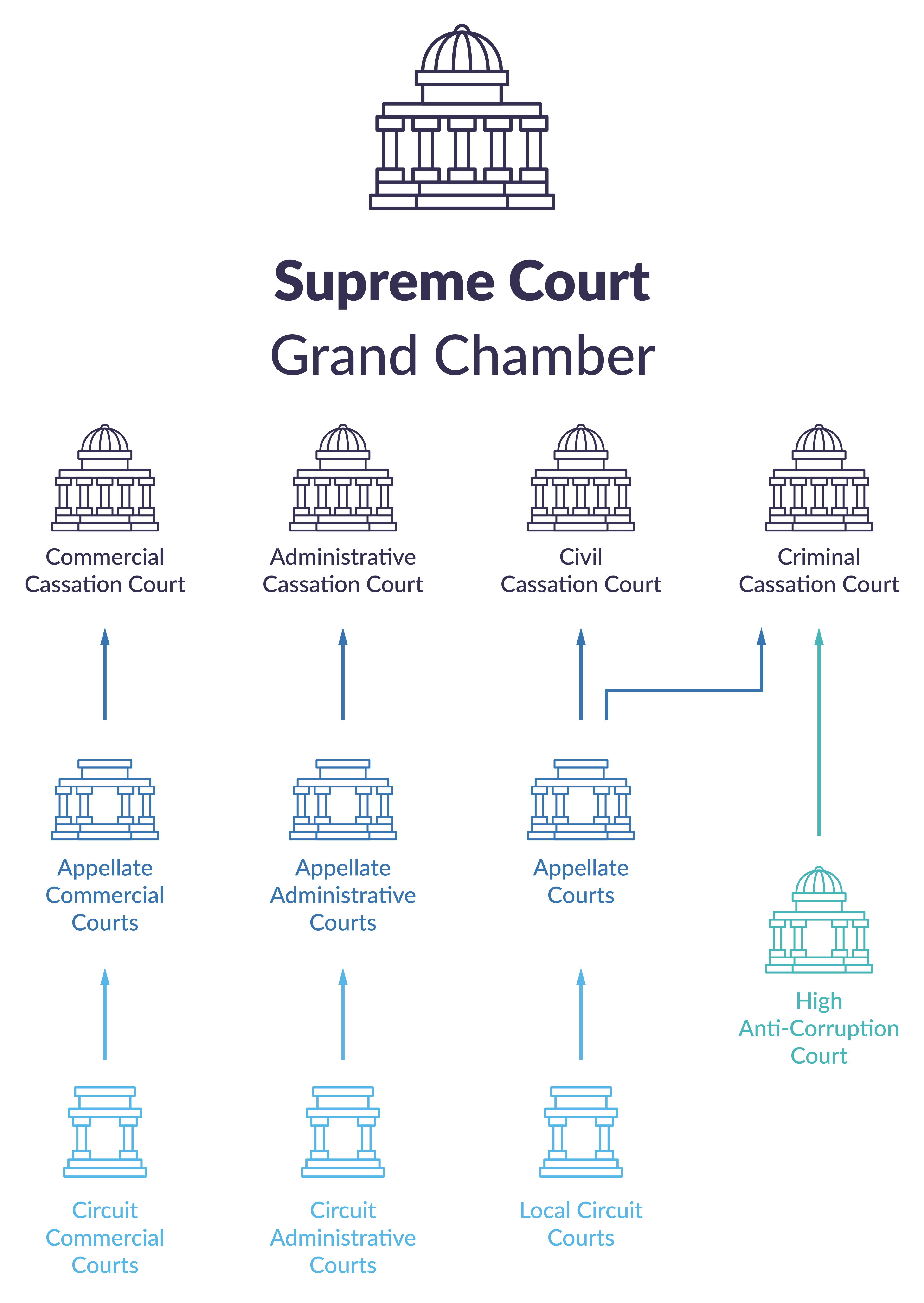

The Ukrainian judiciary, as reformed most recently in 2016, is organised as a three-level system:

- At the lowest level are first instance courts, including local circuit courts (with criminal and civil jurisdiction), circuit administrative courts, and circuit commercial courts. These courts are distributed throughout the country.

- The second level consists of appellate courts organised into three subdivisions: ordinary appellate courts that hear appeals from the local circuit courts, and appellate administrative courts and appellate commercial courts that hear, respectively, appeals from the administrative and commercial circuit courts.

- The Supreme Court, at the top of the judicial hierarchy, consists of a Grand Chamber and four Courts of Cassation: Commercial, Administrative, Civil, and Criminal.

Prior to the HACC’s creation, a criminal case involving alleged corruption would be heard before a local circuit court in the relevant district; the verdict could be appealed to the appropriate circuit court and from there to the Criminal Cassation Court. The HACC, based in Kyiv, replaces the first two levels in this hierarchy for certain cases. Specifically, HACC jurisdiction extends to cases brought by NABU and SAPO against designated high-level officials (including ministers, deputies, members of parliament, agency leaders, judges, prosecutors, and heads of state-owned enterprises) for a specified set of corruption-related crimes that entail damage in excess of a monetary threshold (currently 968,000 hryvnia, roughly equivalent to US$39,500).83a5d1bf2a82 The HACC’s trial chamber, which has 27 judges (nine of whom have investigative rather than trial functions) who sit in three-judge panels with the exception of investigative judges who sit alone, serves as the first instance court for such cases. Parties may appeal rulings from the HACC trial chamber to the HACC appellate chamber – an independent body with 11 judges who also sit in three-judge panels.532ccdf2a77b Uniquely, both the trial and appellate chambers are part of a single legal entity with the chief judge of the trial chamber as its head. The appellate chamber’s decisions can subsequently be appealed to a panel of the Criminal Cassation Court specially established to hear anti-corruption cases, but without specially vetted and selected judges.

Figure 1: The Ukrainian court system

Source: Adapted from USAID New Justice Program.

Key innovation: The judicial selection process

The HACC’s most innovative feature is the role of foreign experts in the judicial selection process. To understand this feature, it is useful to first review the ordinary process for appointing Ukrainian judges. As set out in Article 70 of the Law on the Judiciary and Status of Judges of 2016, it works as follows:

- Applicants for judgeships must be Ukrainian citizens between 30 and 65 years of age, who hold a law degree, have at least five years of professional work experience in the field of law, and are ‘competent and honest.’ Candidates submit a written application that is reviewed by a 16-member body called the High Qualification Commission of Judges (HQCJ).5c09b7575e1c The HQCJ administers several assessments, including a legal knowledge test, a practical exam, and a psychological evaluation. The HQCJ also interviews candidates and gathers information from other institutions, including the Prosecutor General’s Office, NABU, the National Police, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs.

- The 2016 Law on the Judiciary and Status of Judges created an additional body, the Public Integrity Council (PIC), to assist the HQCJ in determining the eligibility of a judicial candidate through an evaluation of the candidate’s professional ethics and integrity.6f27af041b9c The PIC is a 20-member body that includes civil society representatives, scholars, journalists, and other professionals. The HQCJ may invite the PIC to participate in interviewing judicial candidates, though this is not obligatory. The PIC can object to a candidate on ethical grounds, but the HQCJ can disregard the PIC’s objection if 11 of the 16 HQCJ members support the candidate.

- The HQCJ forwards a list of approved candidates to the High Council of Justice (HCJ), which makes final decisions and sends the list of selected judges to the president. Within 30 days of receiving the list, the president must sign a decree appointing these judges for life. No legislative confirmation is required.

The HACC selection process differs in two important ways. First, HACC applicants must satisfy one of the following additional criteria: (a) five years of judicial experience, (b) seven years of experience in legal scholarship, (c) seven years of experience as a defence attorney, or (d) seven years of combined experience in these three areas. The second and more innovative difference is the involvement of a new body, the Public Council of International Experts (PCIE), in place of the PIC. The PCIE plays a role similar to that of the PIC, but with two key distinctions. First, while the PIC is composed of Ukrainian citizens, the PCIE’s six members are foreigners recommended by international organisations with which Ukraine has agreements concerning anti-corruption initiatives. Second, the PCIE has greater power to block candidates.

The PCIE was initially established for a six-year term; individual PCIE members are selected for two-year terms without the possibility of reappointment. The PCIE selection process worked as follows. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs compiled a list of international organisations eligible to propose PCIE candidates. These organisations presented the HQCJ with a list of candidates, with each organisation entitled to propose at least two names. The HQCJ then selected six names from this list.

The PCIE’s main role is to screen HACC candidates for integrity and ethics. The HQCJ provides the PCIE with a dossier on each candidate who makes it through the initial screening; this dossier includes the candidate’s income and asset declarations, memos from NABU, and other relevant materials. The PCIE may request additional documentary evidence and hear witnesses.

If at least three PCIE members have doubts about a candidate’s integrity, the PCIE can initiate a joint meeting with the HQCJ. At this meeting, the 22 participants (the 16 HQCJ members plus the six PCIE members) may solicit additional information and bring the candidates in for additional questioning. The HQCJ and PCIE members then vote on whether to approve the candidate, applying a ‘reasonable doubt’ standard. (That is, each member should vote to advance the candidate only if there is no reasonable doubt about the candidate’s integrity or ethics.) To pass this stage, a candidate must receive at least 12 ‘yes’ votes, with at least three of those votes coming from the PCIE members and nine from the HQCJ (the so-called ‘3+9 formula’). So, if four of the six PCIE members oppose a candidate, the HQCJ cannot forward that candidate’s name to the HCJ. Alternatively, if a combination of three or fewer PCIE members and a minimum of nine HQCJ members oppose a candidate, the candidate is also blocked.1717424fed53

The rest of the selection process resembles the process for ordinary judges. The HQCJ completes its review and forwards a list of candidates to the HCJ, which conducts its own review and sends the final list to the president.

The HACC’s proponents viewed the PCIE’s involvement as crucial, because they believed that only screening by foreign experts could guarantee that the HACC would not be compromised by the appointment of unsuitable judges. HACC advocates were influenced by the fact that the PIC’s recommendations had been ignored in the 2017 Supreme Court selection process, resulting in the appointment of several judges of questionable integrity (Ukraine Crisis Media Center 2017). The international community backed Ukrainian civil society on this point. Notably, the IMF, relying on a proposal in the Venice Commission report, made the participation of international experts in the HACC selection process a condition for the release of assistance funds.

In July 2018, the HQCJ sent a letter to the 14 international organisations identified as eligible by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, inviting them each to nominate two or more candidates for the PCIE. In September 2018, five of these organisations – the EU, Council of Europe, European Anti-Fraud Office, European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, and Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development) – acted in concert, jointly providing the HQCJ with a consolidated list of 12 candidates. Submitting a joint list prevented the HQCJ from discriminating among PCIE candidates based on which organisation had recommended them. No other organisations appear to have provided additional nominees. While some critics complained that the HQCJ chose the weaker six of the 12 candidates nominated, the six candidates chosen to serve on the PCIE are nonetheless highly qualified. Joint nomination by international organisations has expanded beyond the HACC experience. Recent legislative amendments concerning the selection commission for the new head of the National Agency for Prevention of Corruption proposed the option of a joint list as a way for the donors to nominate individuals to the selection commission.

Selection of the first set of HACC judges took place between September 2018 and April 2019, with the PCIE most active in January 2019. The PCIE called for joint meetings to discuss 49 of the 113 candidates who made it past the preliminary assessments. Six meetings were held; 39 candidates were eliminated, and three more withdrew. A total of 71 candidates advanced in the competition: 52 for a position in the trial chamber, and 19 for a position in the appellate chamber. The HQCJ recommended 27 of the 52 candidates for the trial chamber, and 12 of the 19 for the appellate chamber. The HCJ forwarded all these names to the president, except for one appellate candidate who dropped out. All 38 judges were seated, and the HACC began operations in September 2019.

Most of the 38 judges selected to serve on the HACC are viewed as honourable and competent, though civil society did express concerns about eight of the selected candidates. Many experts contrast the HACC selection process favourably with the process for the Supreme Court. While the PIC was unable to prevent the appointment to the Supreme Court of questionable candidates, the PCIE apparently helped prevent several inappropriate appointments.

While this is encouraging, a number of challenges – some legal, others practical –have been noted about the PCIE’s role in judicial selection.

First, some claim that the PCIE infringes on Ukraine’s sovereignty. The force of this argument is mitigated by the fact that Ukraine’s parliament authorised the PCIE, and by the fact that, legally, the PCIE acts as a subsidiary to the HQCJ, which retains most of the power in selecting HACC judges.

Second, some argue that the PCIE should have broader power to recommend candidates, rather than only blocking those candidates about whom there are significant integrity concerns.

Third, the PCIE had to act under short notice and excessively tight deadlines. PCIE members were not appointed until early November 2018 but were expected to complete their work by the end of January 2019; they had only 30 days in Kyiv to review dossiers, question candidates, and make decisions. With such a compressed schedule, and the fact that PCIE members neither spoke Ukrainian nor had much prior knowledge about Ukraine, the council faced a daunting task. Fortunately, the International Development Law Organization (IDLO) and the EU Anti-Corruption Initiative (EUACI) established a Secretariat—composed of legal analysts, interpreters, and other support personnel—that proved crucial to the PCIE’s performance. EUACI and other donors also supported civil society in performing integrity checks on the candidates, the results of which were provided to the PCIE.

The HACC going forward: Prospects and challenges

It is too soon to thoroughly assess the HACC’s performance. As of 1 December 2019, the HACC had issued two judgments, one convicting a regional judge, and another convicting the deputy director of a state-owned enterprise. In both cases the penalties were relatively light, but one cannot draw broad conclusions from these two cases about the court’s likely future activity. While a performance assessment is limited at this time, it is worth noting some of the challenges to the HACC’s effectiveness in addressing Ukraine’s corruption problem.

First, the HACC’s success depends on the quality of work conducted by NABU and SAPO. The HACC can convict only if investigators uncover, and prosecutors present, evidence of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt.

Second, the fact that parties can appeal HACC decisions to the Supreme Court’s Criminal Cassation Court may be a concern. Supreme Court judges have not gone through the same vetting process as have HACC judges.

Third, the caseload may prove excessive relative to the number of HACC judges. This problem is compounded by the fact that HACC judges must sit in panels of three, and if one judge is absent for any reason, the remaining two must wait for the third in order to proceed with hearing a case.

Fourth, some observers warn of unrealistic expectations for the HACC to deliver swift convictions of powerful figures. The role of a court is to do impartial justice, not necessarily to convict, and unrealistic expectations could lead to unwarranted disappointment if the HACC does not have an immediate transformative effect. The HACC’s proponents may need to both temper their own expectations and manage those of the Ukrainian citizenry.

Finally, some critics worry that an excessive focus on the HACC could distract activists and the international community from the need to implement reforms to other institutions, like the police and the Prosecutor General’s Office (Dubrovskiy and Lough 2018). While the establishment of the HACC is a major victory, it is important that activists and external supporters use this success as a catalyst for even more vigorous reform efforts, rather than treating the HACC as a cure-all.

The HACC is an unprecedented attempt to reform Ukraine’s judiciary by creating a stand-alone court to address high-level corruption. The first round of HACC judge selection appears to have gone well, with the PCIE fulfilling its mission of screening candidates for integrity. Yet the court’s effectiveness is not guaranteed. To ensure its success, the government, civil society, and external supporters must continue to identify and respond to challenges as they arise.

- During these debates, some questioned whether the HACC violated Article 125 of the Ukrainian Constitution of 1996, which states that ‘the creation of extraordinary and special courts shall not be permitted.’ Proponents argued that the HACC was not a ‘special court’ within the meaning of Article 125. The HACC’s constitutionality has not been officially challenged at the time of writing.

- The HACC’s jurisdiction extends to criminal investigations filed after 22 September 2019. A provision of the law provided for transfer to the HACC of cases already pending before the ordinary courts. To prevent the HACC from being swamped by the more than 3,000 corruption cases already pending, the parliament amended the procedure for transfer of cases shortly after the HACC began operations.

- There are 12 seats in the HACC appellate chamber, but currently only 11 judges because one of the 12 original appointees declined to take the position.

- The HQCJ currently has 16 members, but a law adopted by parliament (Draft Law 1008, act 193-IX) on 16 October 2019 would decrease the HQCJ from 16 to 12 members. This change, however, had not yet been implemented at the time of the writing (Chyzhyk 2020).

- The PIC’s only experience so far has been in the 2017 process for selecting Supreme Court judges.

- The formula might change if the number of HQCJ members changes. See note 4.