ABOUT THE SERIES

Experiences, lessons, and advice for future anti-corruption champions

In this series, Phil Mason covers the origins of anti-corruption in DFID as an illustrative example of how development agencies came to encounter the issue in the late 1990s. He lays out how he and DFID saw the development implications of corruption, how the world was so ill-equipped to deal with it, and how the global response has developed to what it is today.

Mason explores the origins of DFID’s involvement in some of the ‘niche’ areas that often stump development practitioners as they lie outside their usual comfort zones of development assistance: money laundering, financial intelligence, law enforcement, mutual legal assistance, illicit financial flows, and asset recovery and return. He summarises lessons learned over the past two decades, highlights some of the innovations that have proved especially valuable, and point up some of the challenges that remain for his successors.

Parts

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem (this note)

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

In this note, I offer a perspective from personal experience of one of the trickiest aspects we, as UK anti-corruption development practitioners, faced in taking forward our ambitions – the role and impact of our Overseas Territories (OTs).

What’s the issue?

Some of the UK’s OTs have achieved global notoriety in the field of money laundering and illicit financial flows. They have had a hugely negative effect on the UK’s overall efforts to build an international reputation for combating corruption. To most of the world, we have been seen as complacently harbouring major facilitators of ‘dirty money’ at the same time as we are trying to extol our progressive anti-corruption credentials.

How does this contradiction arise? Why does the UK persist in tolerating this behaviour from jurisdictions over which it formally has reserved powers to override local autonomy and could lay down the law exactly as it wished?

What follows is a personal reflection, seen from the position of a Department for International Development (DFID) operator who was focused on the developmental impacts of these practices as they touch the rest of the world. I hope to offer an explanation (which is far from a justification) for this peculiar state of affairs. By reading this note, future policy operators will at least know the lie of the land they are attempting to do battle on.

Where we will go

I shall outline the place of the OTs vis-à-vis the UK as a whole and their association with the rise of the phenomenon of the offshore financial centre. I will go on to give a sense of the impact on global corruption of those whose economies are essentially based on servicing this finance. I will also explore the motivations and viewpoints of the OTs as to their relationship to the UK.

Bringing all this together at the end, I will try to offer an explanation as to why we find ourselves in the bizarre position. As things stand, metropolitan UK continues to express disquiet over the practices of the OTs, yet takes no action against them. Nor does it force the OTs to choose to become independent. On the other side, the OTs continue with some vigour and animosity to accuse the ‘mother country’ of bad treatment, while expressing an unchanging wish to keep their subservient status as non-independent territories.

Trust me, I believe there is a logic (albeit contorted) to this!

The 14 remaining UK Overseas Territories encompass huge diversity in size and income

Note: this map does not distinguish St Helena from its sub-dependencies, Ascension Island and Tristan da Cunha. So resist counting them up – you won’t get 14!

Who we are talking about – a brief primer on the British Overseas Territories

The Overseas Territories* are essentially the remnants of the British Empire, the ‘last pink bits’ that for a range of reasons have not progressed on the path to independence that the vast majority of other British colonies did. It will become evident as we proceed why that has been the case for these places.

There are 13 remaining territories under UK stewardship (14 if we include the pair of UK military bases in Cyprus – Akrotiri and Dhekelia – which technically constitute an OT). Of these, 3 are unpopulated (the British Antarctic Territory, British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT), and South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands). The overall population of the others amounts to some 250,000, ranging from Bermuda and Cayman (65,000 each) to Pitcairn (49).

The UK OTs encompass huge diversity. In size, they range from the vastness of British Antarctic Territory – just over 1 million square miles (2.6 million square kilometres) – to Pitcairn, at 1.75 square miles (4.5 square kilometres), half the size of Heathrow Airport, set in the south Pacific, 1,000 miles (1,600 kilometres) from the nearest land (French Polynesia).

One of the UK’s OTs has the highest per capita income in the world: Bermuda – 50% higher than the US and more than twice that of the UK. In Tristan da Cunha, a dependency of St Helena, we have the most isolated human community on the planet – it is situated 1,500 miles from Cape Town, 1,300 miles from St Helena, and 2,200 miles from the Falklands. Just 250 people live there, and they are entirely self-sufficient.

The OTs contain 90% of the UK’s biodiversity, comprising some of the richest environmental assets on Earth.

For our purposes, we shall focus on the issues arising from those territories which make their living by serving as offshore financial centres. This boils things down to essentially four big players – Cayman Islands, British Virgin Islands (BVI) and Bermuda in the Caribbean, and Gibraltar (until Brexit, a gateway to the single European market). There are also two recent minor players, Anguilla and Turks and Caicos.**

* To keep the scope of this piece manageable, I intend only to cover the OTs – since they illuminate unique factors that give rise to the peculiar relationship with the UK that are relevant to our illicit finance story. I will not consider in detail the UK’s other ‘vulnerability’ in this area, the Crown Dependencies (Guernsey, Jersey and the Isle of Man). These are also significant offshore centres and give rise to similar illicit financial flow (IFF) risks as the OTs. Yet the political dynamics vis-à-vis the UK are very different, since they are possessions of the Crown, not the UK government, and are governed under different constitutional principles to the OTs. Their omission here, however, is not intended to imply they do not have just as significant global impacts on illicit finance.

**A UK Treasury review in 2009 looked at the scale of these offshore activities. While now dated in terms of the statistical information, this does provide a good snapshot of the nature of the business involved.

‘Sunny places for shady business’ – the origins and characteristics of ‘offshore’

Space does not permit a detailed history of the rise of the phenomenon of the ‘offshore financial centre.’ There are many good accounts, a favourite being The Sink (Jeffrey Robinson, 2003). This begins at the beginning in the organised crime era of the 1930s, swings through the early stirrings of the ‘60s and ‘70s (with the first bastions – Switzerland, The Bahamas, and the Dominican Republic), before the explosion of offshore centres in the ‘80s and ‘90s. That brings us to now with, according to one estimate, more than 70 such centres worldwide.

A paper from 2000 by the International Monetary Fund (IMF) still gives a good introduction to the range of services that typically characterise what we mean by an ‘offshore centre.’ It also discusses the aggregate economic impact these activities are thought to bring about.

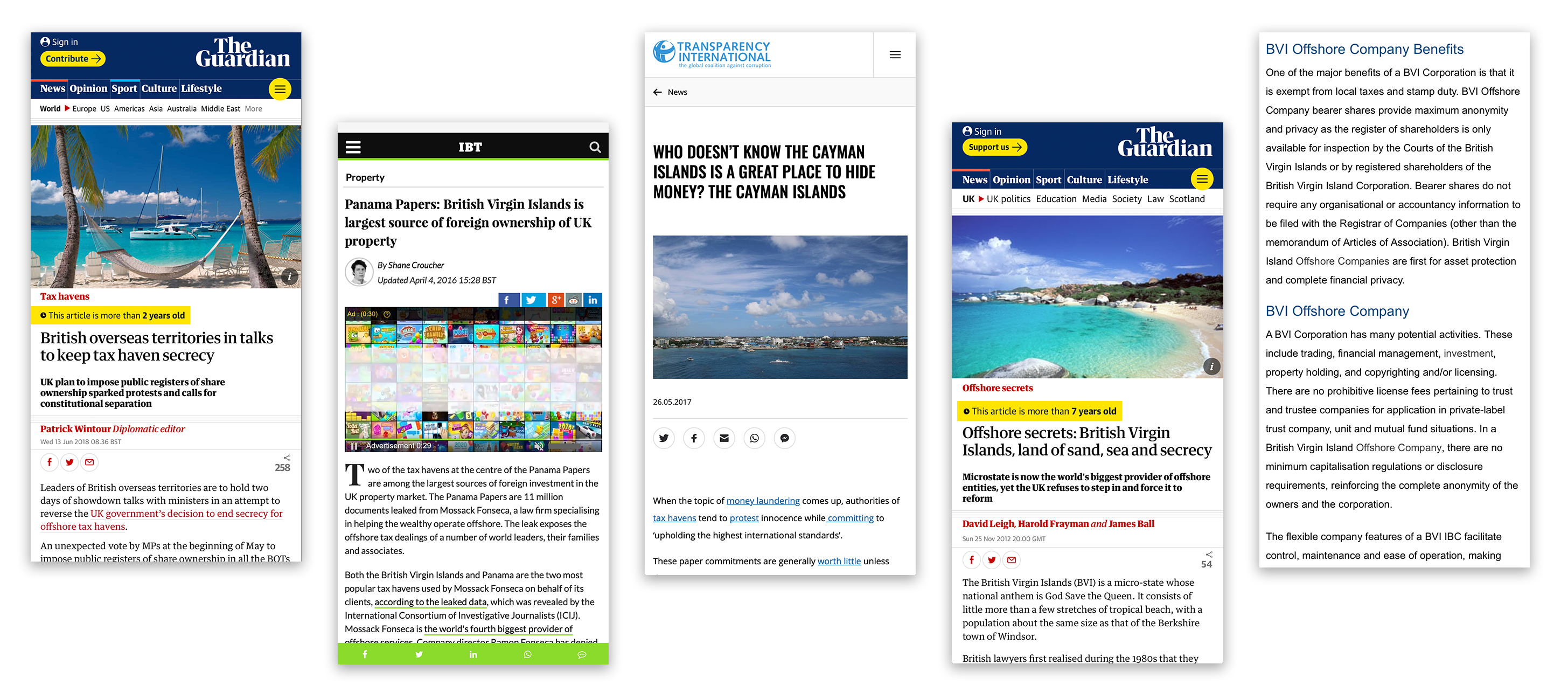

Before we turn to the ‘how’ and the ‘why’ of the particular UK setting, we should take a quick detour into the ‘what.’ Here are some illustrative examples, drawn from the UK’s two most high-profile actors in the game – BVI and the Cayman Islands – to give a taste of the reality of this business, and, not to put too fine a point on it, the brazenness with which is it advertised.

British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands are the UK’s most high-profile offshore financial centres.

The UK conundrum

To understand the phenomenon of the OT offshore centre, we need to grasp the foundations of the relationship.

The explanation for why an OT remains under the UK wing will fall under one of three reasons.

1. Necessity

The territory is simply too small to be a viable independent state (St Helena and dependencies; Pitcairn) or is an unpopulated territory that is important to UK interests (British Antarctic Territory; South Georgia).

2. Strategic imperative (theirs or the UK’s)

The territory faces an external political threat that means independence is existentially risky (Falklands, Gibraltard29ba60820dc), an overwhelming natural threat that it cannot cope with on its own (Montserrat, which has an active volcano), or it represents a security asset to the UK (BIOT [Diego Garcia], Cyprus bases).

3. Choice

The territory actively chooses to remain under British stewardship (Anguilla, Bermuda, BVI, Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands).

It is this last category that concerns us here. All of this latter group have dabbled to some extent or another in offshore financial services at some time in the last three decades. Three of them – Bermuda, BVI, and Cayman Islands – have built formidably large industries, centred on, respectively, insurance and re-insurance; company formation (‘shell’ entities that are not working companies, but simply created to act as holders or conduits of finance); and banking. The latter two are the most susceptible to illicit financial flows (IFFs). They are the reason why BVI and Cayman ‘loom large’ in the global identity parade of enablers of money laundering. How they came to be in this position stems from the nature of the political settlement with the metropolitan authority in the aftermath of decolonisation.

Towards the end of the shedding of Empire, as the size of the remaining possessions became ever smaller, there was an acceptance in London that the very smallest might never be capable of managing a fully independent future. The future course was shaped by one unavoidable constraint and two policy choices.

‘Do your own thing; don’t look for help from us’

The unavoidable constraint was the ‘sacred trust’ obligations arising from the United Nations Charter.e85a4df734ba Under this, the UK acknowledges its responsibility to promote the ‘well-being’ of those populations that remain under its administration. But the policy options chosen to achieve this were distinctly pragmatic. The acceptance of ensuring the OTs’ well-being did not stretch to subsidising them. OTs were given a clear signal that they needed to make their own way in the world as best as they could. Only those falling into economic distress could expect some help from the metropolitan coffers.

The three big offshore centres, one of which remember is the richest place per capita on the planet, arguably just followed their instructions – very well indeed!

The two policy principles the UK followed that have moulded the shape of the relationship we have today were that local autonomy in each OT should be maximised as far as possible, and that the financial obligations of the metropolitan power should be minimised as far as possible. (The theory appears to have been that pursuing the former would help secure the latter.)8f2c71312ec2

The combined effect of these factors gives us the current situation: OTs enjoying constitutions that devolve almost all authority to locally elected administrations. This explains the sharp objections when London intrudes on issues that affect their economic prospects, such as requiring public registers of beneficial ownership of BVI’s shell companies.

But the question arises at least for these offshore centres, why do they need to put up with any such interference at all? As developed, rich places, they could surely sustain an independent status and be rid of these intrusions?

The clue is in their flags

That Union Jack in the top left-hand corner of every OT flag gives the game away for the financial centres. Trading in often-volatile global markets, the make-up of the flag sends a vital signal – that this place is following the British standards of rule of law, stability, and security. Not least, it implies there is a larger ‘backer of last resort’ should anything go wrong. This is a highly persuasive advert. It is why the OTs put up with the prickly relationship with London.

Flags of overseas territories

The Union Jack in the top left-hand corner of every OT flag implies there is a larger backer of last resort should anything go wrong.

But they do so also because they know there’s a second factor at play here, potentially even more powerfully in their favour. It answers the reverse question – why does London put up with this?

The London eye

Looking at things from this end of the pipeline, it remains a bit of a mystery at first sight why London does not simply rid itself of these troublesome places. Jettisoning the three big offshore centres from the OT family would remove at a stroke some of the knottiest problems the UK has to contend with in the IFFs arena. So why has that not been the approach?

There are two answers, a semi-official one and one based on personal speculation, but speculation based on two decades of closely observing (and for a nearly five years managing for DFID) these relationships.

The first I call a ‘semi-official’ version because it is an argument I have personally heard advanced by officials in relevant departments but it is not, so far as I know, publicly cited (at least in these terms) in official statements of policy. It runs like this: the overall state of IFFs would be worse if we, the UK, allowed these places to become independent, since we would ‘lose sight of what is going on’ (the words of one official to me). Our guiding hand of common sense and integrity would no longer be there to keep them from straying from the ‘straight and narrow’.

There are a few holes in this argument, not least the extent of autonomy granted to the OTs means there is precious little leverage that London has, short of the ‘nuclear option’ of the Governor exercising his/her reserve powers to make law on London’s behalf. And London has been very, very reticent, to the point of a self-denying ordinance, to let Governors intervene.

There has also been very little evidence of London actually exerting much of its self-asserted better stance to try to change things in these OTs. The mantra has been about ‘encouraging’ the OTs to achieve higher standards; yet, any independent authority can do that too. The UK’s supposed privileged position has shown no great returns over the years.891db53f858d

It might be noted that this argument is hardly a new one for London. Exactly the same sentiment was used more than 200 years ago to justify Britain’s continued role in the slave trade, on the grounds that if Britain stopped doing it, the trade would fall into the hands of the ‘less civilised’ French, Spanish, and Portuguese. So British ships carrying on were vital to maintain a certain level of decency to the business. Here’s Henry Dundas, Home Secretary and Secretary for the Colonies, speaking in Parliament in 1799:

Would the interests of humanity, would the advantage of the coast of Africa be [served by abolition]? Certainly not. The trade would still be carried on; the supply would be obtained with the difference that now the trade is conducted under the control and regulation of this House whereas then it would be carried on by other nations free from all the salutary and humane regulations enforced by the parliament of this country … A precipitate measure would take out of the hands of this House the means of alleviating, by proper regulation and control, the miseries with which the trade is attended.

Treasury ministers (or their staff) have long memories indeed!

The connected web

A more compelling argument – my speculation – comes from taking a broader perspective, seeing the OTs in the round. My hunch is that the answer lies here.

A foundational principle of the relationship with the OTs is that each and every territory has the right of self-determination. Usually, this means the choice to go independent. But it is the corollary that assumes greater significance for our story – for the other dimension of self-determination is that the UK will never force a territory to leave the family against its will.

That promise has been the cornerstone of policy for more than 50 years, since it was spelt out by George Thomson, Foreign Office Minister, in September 1968:

We … will always adhere closely to the cardinal principle to which we have adhered in the past – that the wishes of the people concerned must be the main guide to action – it is not and never has been our desire or intention either to delay independence for those dependencies who want it or to force it upon those who do not. [emphasis added]

The implications of this become stark. A move to independence must be the result of what is termed the ‘settled will’ of the local population. In practical terms, this means a referendum on the specific question of independence. (Bermuda has had several over the years, all declining the idea).

For some, independence is far from attractive. Rather, it holds a distinct threat. It was a commonly heard sentiment among citizens of the Caribbean territories where independence was a viable option that a popular referendum would never return a vote in favour, ‘because we don’t trust our politicians’. Keeping the link with London was seen as their safeguard against what a clique of local politicos might do unchecked.

For a smaller set of OTs – two in particular – the issue takes on existential significance. We noted earlier that Gibraltar has only the choice of being under the UK or Spain. It dreads the threat of unilateral action by London. Likewise, for the Falklands. The more likely outcome for it would not be independence but absorption by Argentina. They too fear a London ready to exercise unilateral force.51793be91b8e

So, what would be the consequences of London getting fed up with BVI or Cayman Islands? Telling them they must go independent would solve that particular problem. But doing so would let a ‘genie out of the bottle’. If we (the UK) could force one OT to leave, how much longer would it be before Argentina would be asking the same, or Spain?

It is this that sends ‘shivers down the spines’ of those who have ever been in charge of OTs at the London end. The political ramifications of being seen to sell ‘kith and kin’ (as those in the Falklands are still fondly regarded in some quarters) would be incalculable.

It is here, I suspect, that the UK’s quandary with IFF-fuelled OTs meets its determining fate. And explains the incongruity of the relationship that we see with our offshore financial centres.

So there we have it: OTs fractious at the strings attaching them to London, but seeing the advantages outweighing the negatives (which they have become accomplished at deflecting in any case); and London petrified that taking stronger action could rebound in far-off parts of the OT family, with political consequences too unthinkable to bear.

And in the meantime, and among many others, the poor of the developing world who are losing resources through illicit flows into these places, carry on paying the price.

–––––––––

Other parts of this series of U4 Practitioner Experience Notes

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem (this note)

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

- Gibraltar does not have an option for independence. Under the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht, which ceded the territory to the UK in perpetuity, if the UK gives up possession, it reverts to Spain.

- Article 73: ‘Members of the UN which have … responsibilities for the administration of territories whose people have not yet attained a full measure of self-government … accept as a sacred trust the obligation to promote to the utmost … the well-being of the inhabitants of these territories …’

- Britain did have to consider whether integration of the territories into the UK as per the French model offered a solution when, in 1955, Malta made a formal request to do just that. The UK government decided against the approach on cost grounds (equalising tax and social security levels, and the annual cost of budget support, estimated to be 15% of the entire development budget for the Empire). This experience ensured that integration has not been considered as a serious option since. More recently, a Foreign Office strategic review in 2003 concluded that there was no enthusiasm in the territories for French-style integration. Most were reported to ‘dislike the very intrusive French system of administration’.

- One reason for this goes back to the ground rule of ‘no subsidy’ that has governed relations with OTs from the start. London is always nervous that any action that undermines the economic model of these places will quickly turn into a demand for financial support from the centre. Hence London being conflicted over taking executive action to strengthen the controls that could stem financial flows.

- In my time, we came close when an OTs minister became frustrated at how the ‘mutual responsibility’ foundations for the relationship had become unbalanced. The OTs appeared to enjoy all the fruits of effective independence, but were not, in UK eyes, returning the favour by observing responsibilities that London looked for in maintaining standards in a range of policy areas. Not for nothing was it often reported that Caribbean chief ministers were saying they had ‘the best deal in the world’.