ABOUT THE SERIES

Experiences, lessons, and advice for future anti-corruption champions

In this series, Phil Mason covers the origins of anti-corruption in DFID as an illustrative example of how development agencies came to encounter the issue in the late 1990s. He lays out how he and DFID saw the development implications of corruption, how the world was so ill-equipped to deal with it, and how the global response has developed to what it is today.

Mason explores the origins of DFID’s involvement in some of the ‘niche’ areas that often stump development practitioners as they lie outside their usual comfort zones of development assistance: money laundering, financial intelligence, law enforcement, mutual legal assistance, illicit financial flows, and asset recovery and return. He summarises lessons learned over the past two decades, highlights some of the innovations that have proved especially valuable, and point up some of the challenges that remain for his successors.

Parts

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption (this note)

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

In this note, I delve into an aspect of corruption that has become increasingly central to the global response: money laundering and flows of illicit finance. It is one that holds many challenges for conventional development agencies.

In the opening section, I try to demystify what we are talking about. I then explore why tackling money laundering and illicit financial flows (IFFs) presents particular difficulties for donors. I go on to look at the developmental consequences of the phenomenon and why this topic should be a priority for donors. Finally, I consider the complications in this field for donors and some of the current live debates that practitioners should be aware of.

Money laundering and illicit financial flows – what are we talking about?

‘Money laundering is the processing of criminal proceeds to disguise their illegal origin’

– Financial Action Task Force [FATF]

When a criminal activity generates substantial profits, the individual or group involved must find a way to control the funds without attracting attention to the underlying activity or the persons involved

Illicit financial flows…

… are the resulting streams of illegal funds that are moving through financial systems

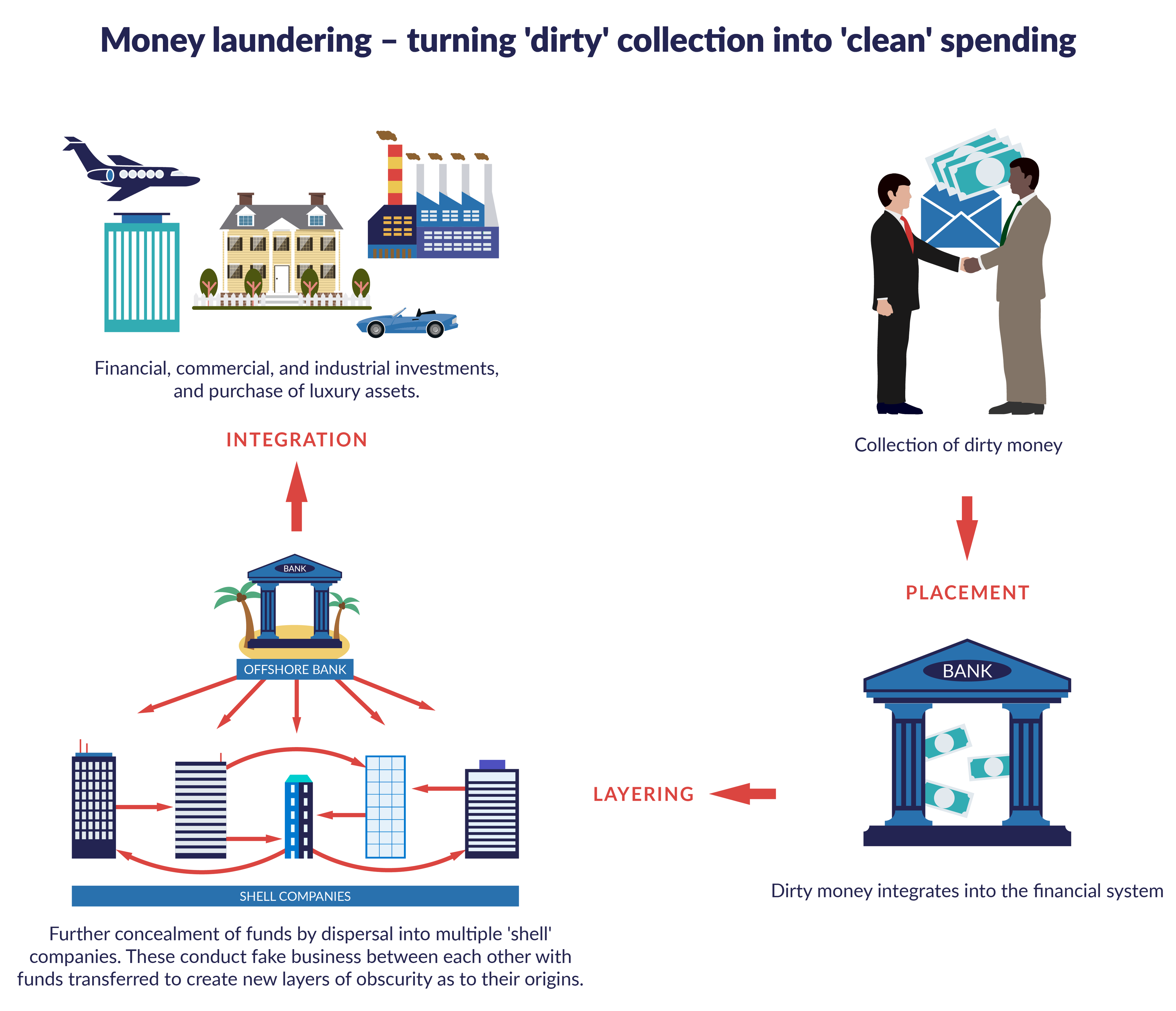

Figure 1. The essential steps of how money laundering works

Money laundering involves a relatively simple cycle of steps:

- Dirty money needs to be ‘placed’ in the financial system in order to distance it from the original criminality. The criminal will usually choose entities where high volumes of cash do not look out of place, such as casinos, dealers in high-end valuables such luxury cars, or money exchange/transfer companies.b585b3f2d21b Note that these days, criminals are unlikely to try to place their cash directly into a bank because of the improved ‘know your customer’ checks that banks must undertake as part of anti-money laundering regulations. These seek to ask about the depositor’s line of business to validate the origins of the money. Banks, and other regulated sectors, are then required to report any attempted ‘suspicious transactions’ to the authorities for further investigation.446225b85df9 Hence, criminals will search for less diligent, and less direct, entry routes into the formal financial system.d6d6a0e7ab83

- The best money launderers are highly innovative in how they begin to put more distance between the money and its initial entry point into the financial system. A fake company is created, and the money transferred to its accounts. More fake companies, usually set up across many different jurisdictions, are then used to further mask the money’s origins by transferring funds through each. The higher the number of ‘layers’, the harder it will be for law enforcement to follow the thread and make the connections back to the original placement.

- Finally, given that the whole point of the exercise is to be able to enjoy the fruits of one’s criminality, the criminals are able to draw out their money from the last resting place of the funds, after their many travels. The money appears clean (or ‘laundered’). It is ‘integrated’ back into use in the real world for the benefit of the perpetrators.

The requirements of money launderers have spawned a market for locations around the world in which to create fake companies or accounts to hold ‘dirty’ money. A constellation of offshore financial centres has grown up, often advertising themselves as providing greater secrecy than elsewhere, and seemingly having no other purpose than to facilitate these questionable needs.

High-profile examples include the UK’s Overseas Territories (OTs) of the Cayman Islands and British Virgin Islands, as well as others like Panama, Dubai, and Delaware. I will look at the UK OTs in detail in Note 7.

Illicit financial flows – is there a clear definition?

No. What precisely constitutes an illicit financial flow is hotly contested. It is not merely a technical difficulty. There are high politics involved in defining the scope, as developing countries perceive developed countries as wanting to exclude certain practices in order to favour the business interests of their multinational companies. The challenge of reaching a consensus on what the problem consists of therefore gets wrapped up in highly contentious disputes between governments.

The most commonly used definition is the World Bank’s: ‘Money illegally earned, transferred, or used that crosses borders’.

Essentially, there are three ways in which finance can become illicit:

- the finance is the result of illegal acts (eg corruption, bribery, tax evasion, drug production); or

- the finance is the result of illegal acts with legal ‘products’ (eg smuggling cigarettes, trafficking in minerals, wildlife, people); or

- the finance itself is used for illegal purposes (eg financing of organised crime, terrorism).

However, there is a large grey area regarding commercial activities. Developing countries have been keen to include in the ambit of IFFs ‘abusive’ commercial practices, particularly by (largely developed country) multinational companies. Examples of such practices include tax evasion and avoidance, transfer pricing, and profit shifting.

Companies, and developed country governments, not surprisingly take a different view. They hold that apart from tax evasion, which is by definition illegal, the other practices are not automatically illegal. Where the line is drawn as to when ‘abuse’ of these legal practices begins, and hence the point at which the finance involved becomes ‘illicit,’ is a highly contested issue. While there is as yet no consensus, the creation of a new international expert panel in early 2020 offers the prospect of one emerging.

It is noticeable that the African Union/UN Economic Commission for Africa 2015 High Level Panel Report on Illicit Financial Flows, chaired by Thabo Mbeki, takes an expansive view of what should be considered an IFF. It enthusiastically embraces the measurement methodology of advocates who cite abusive trade practices as the biggest generator of IFFs. We shall return to this at the end of this note, as the issue of measurement carries important implications for the focus of policy responses.

IFFs can thus take many forms. Yet a constant driver propelling them is corruption. IFFs can be generated by corruption in the management of public resources and assets. Examples include state looting, especially through state-owned enterprises, and abuse of licensing concessions in areas such as extractives, logging, and telecoms.

The links between development, money laundering, and illicit finance (and ultimately asset recovery), which I deal with in Note 6 are well set out in Making the connection, which was produced for us by the International Centre for Asset Recovery during the early years of our thinking. U4 has also covered the basics exceptionally well, the nature and scale of the problem, as well as spotlighting the roles of developed countries. The IFFs issue continues to be one of U4’s key priority themes.

This note does not need to dwell further on the technicalities of the phenomenon, as these are well covered in the above-mentioned papers. We conclude with some perspectives from personal experience that practitioners need to be aware of when getting involved. I see two main issues: (1) operational considerations and (2) current controversies over methods for measurement of IFFs, which have important consequences for policy choices.

Undermining development, challenging donors

When the funds involved are state assets of developing countries, money laundering and its fruits – IFFs – represent a huge and damaging threat to development. As we saw in Note 2, ‘leakage’ of funds from developing countries regularly dwarfs the inflows of development assistance they receive (and often private inward investment as well). For most developing countries, their resource bucket has bigger holes leaking out precious funds than they are able to accumulate.

But dealing with IFFs is deeply problematic for practitioners on many levels. This is because:

- They are cross-border

This immediately presents issues for an aid provider community that is still predominantly organised around country-level programming: classic donor approaches only therefore touch part of the overall problem. - Action in both countries is needed

IFFs require concerted action both in the developing country (the ‘origin’) and in ‘destination’ countries where the illicit funds end up, which are usually developed country financial centres. This creates further completely new relationships that aid providers need to understand and cultivate: classic donor approaches have rarely ventured into the systems of other developed countries. - Multiple agencies must collaborate

IFFs are difficult to identify and need multiple agencies working well together if they are to be stopped. However, most of these bodies lie outside the usual domain of development donors, like operational law enforcement, gatherers of criminal intelligence, financial sector regulators, or those working on international legal cooperation: classic donor approaches have not normally worked with the agencies that are pivotal to tackling the problem. - Politics gets in the way

IFFs almost always involve deep political dimensions. This is especially the case when the money laundering is being done, or is being given protection, by politically significant actors in the state: however difficult the technical issues might seem in combating IFFs, the political aspects will often present even larger roadblocks to action. - High costs and sustained effort

IFFs involve huge investments of time and energy to successfully pursue. By their nature, most IFFs are hidden in deliberately complex ways, spread around multiple jurisdictions to obstruct detection. They can take even the best investigators decades to pursue and recover, with delays and expensive legal challenges likely at every step. There are also huge uncertainties as to outcomes, as any of the administrative and judicial processes involved could stymy recovery: the length of time and costs involved make pursuing IFFs inherently unattractive to donor funders, who prefer shorter and more predictable activities to finance. - Their 'abstract nature'

IFFs are also, compared to other development challenges that donors have the choice of contending with, a much more ‘abstract’ problem. ‘Success’ is not only far more difficult to achieve, but also more difficult to demonstrate. Recovered stolen funds might merely disappear back into a national treasury, with few specific results to show for the effort. At the same time, good preventive activity produces virtually nothing visible, even if results are obtained. It is notoriously difficult to know the deterrence effect produced by creating strong preventive measures – ‘how much money did not get laundered?’ is like asking which wars did not take place because of successful deterrence: with donors under pressure to ‘show results’, combating IFFs suffers in the priority stakes in a donor’s portfolio of programming choices.

These are profound obstacles to donors taking on the IFFs problem. Money laundering has been graphically depicted as the ‘getaway car’ of corruption. But donor agencies, traditionally looking outward and with eyes only in the direction of their partner countries, have all too often ignored the getaway car carrying illicit funds that is rushing past in the other lane, in the opposite direction. The Department for International Development (DFID) saw that managing the traffic on this two-way street was an essential requirement for tackling modern international corruption, as it affected developing countries.

Note 2 told the history of DFID’s unique response, by using aid funds to create dedicated police units to combat the getaway cars coming out of developing countries and parking in the UK financial system. This approach recognised that IFFs presented a monumental threat to everything donors were trying to do to promote sustainable development.

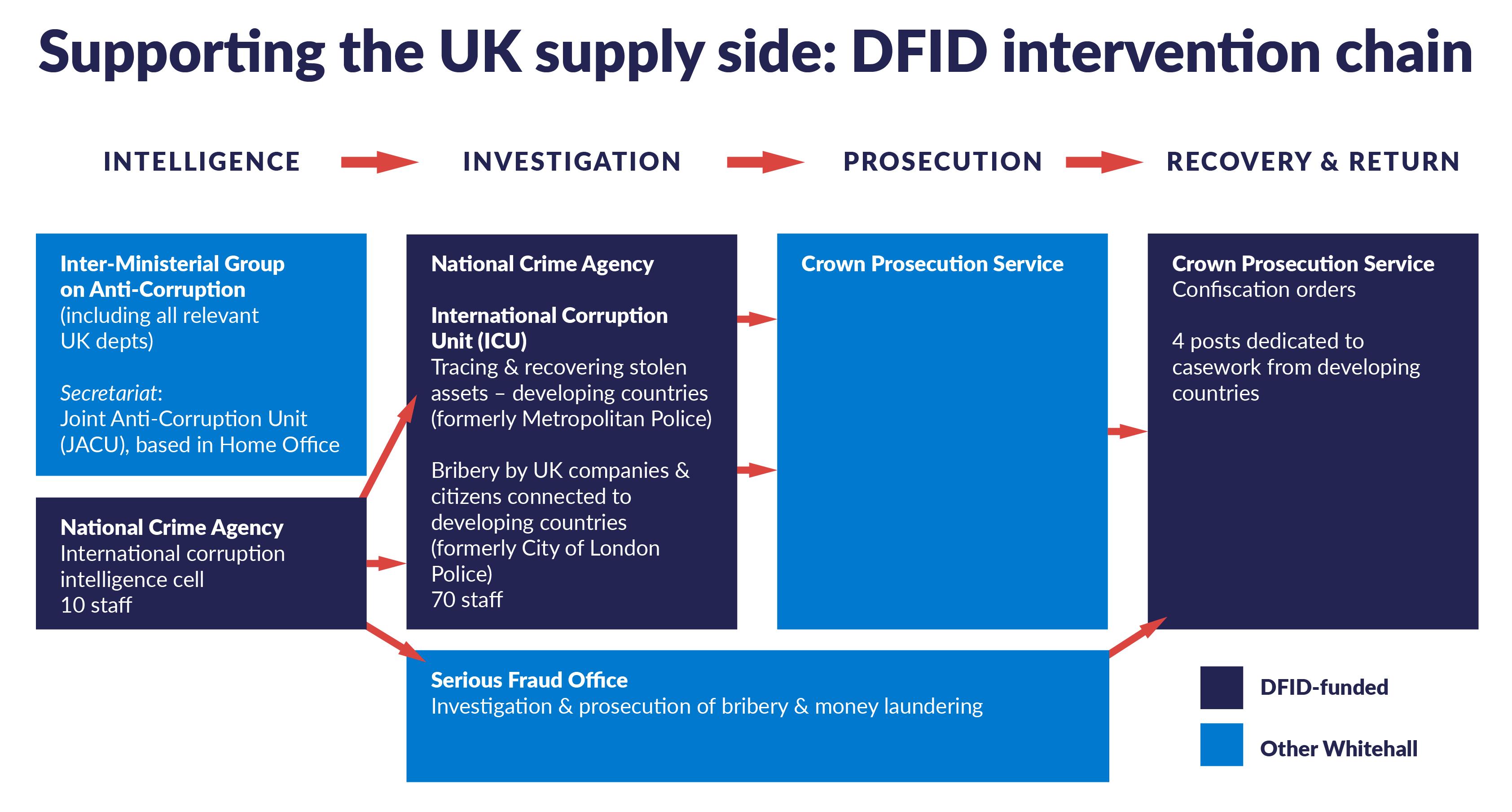

A key lesson we learned in the UK was the vital importance of being able to support the whole chain of the anti-money laundering process. The diagram bellow illustrates how we ensured that our support contributed to the upstream work of intelligence gathering and analysis, as well as the investigation stage itself. We also supported the end of the process, by enabling adequate resources to pursue the realisation of recovered assets after the courts had issued confiscation orders.84393ed42e67

Figure 2

Any donor considering support to money laundering capacity (either at home or in a developing country) needs to be ready to contemplate backing all these elements.

Measuring IFFs – the Global Financial Integrity problem

Global Financial Integrity (GFI) has become the primary source of global- and country-level data on ‘losses from IFFs.’ It regularly estimates annual overall losses from developing countries of more than US$850 billion. This is broken down by source as being in the region of 3–5% through the corrupt practices of government officials, 30–35% through criminal activities (eg drug trafficking), and the remainder – by far the largest element – from trade mis-invoicing. GFI has claimed that up to 80% of IFFs are trade related. Its 2017 report on global flows claimed that 87% of IFFs were trade related.

GFI’s methodology is highly contested. It is based on comparing trade figures in national accounts reported to the UN for exports and imports between countries. It attributes any discrepancy between what one country reports as exports to another country, and what that other country reports as imports from the exporting country as an illicit financial flow.

This produces eye-watering numbers, which have been successful in drawing attention to the important issue of IFFs. However, its overwhelming attribution to trade-based abuses (and in particular, the minimal involvement this implies to ‘grand corruption’ by government leaders) belies real-world experience.

The attribution to trade-related abuses is strongly contested by other academics. DFID had GFI’s methodology critiqued by the Said Business School, Oxford, in 2010 and it was judged to be deeply flawed. As described above, the reliance on country reporting of trade accounts is central to GFI’s method. Critics argue that there are many reasons for discrepancies and errors in accounts, especially from developing country systems where statistical capacity is known to be weak.53ee43b769e6

A good reprise of the counter-argument to GFI’s methodology is the work of Maya Forstater, who has set out the concerns clearly.

The most salient issue here is less the accuracy of the numbers, but the policy implications that practitioners are being encouraged to draw from the figures. GFI’s approach has helped to generate a line of argument, strongly from African leaders for example, such as in the Mbeki report mentioned earlier, that ‘we are not the problem’ in their country’s corruption fight.

The Mbeki Panel relied heavily on GFI data to present a case to the world on how Africa’s wealth was being plundered. The key message that African leaders appeared to want to convey was that corruption by government systems and elites (the usual focus of western donor interest) represented a miniscule proportion of losses compared to that from ‘predatory’ multinational corporations.

The concern for any seasoned anti-corruption hunter would be how easily the GFI’s approach suits developing country leaders. It effortlessly takes the spotlight off them for the quality of governance they preside over. And it severely risks driving donor policy responses into a narrow channel (trade/customs strengthening). This in turn leaves the all-too-evident poor governance issues, which we know are huge drivers of corruption and economic loss, marginalised and ignored. Such a situation is highly convenient for a corrupt politician.

A consensus approach to better measuring and dissecting IFFs into their component parts is urgently needed. We embarked on thinking in DFID to develop ideas for designing a tool that could help a country identify how it ‘loses’ its IFFs. This was in order to set the right policy responses that fit the profile of the problem. That work needs to continue.

–––––––––

Other parts of this series of U4 Practitioner Experience Notes

- Old issue, new concern – anti-corruption takes off

- Fighting the ‘seven deadly thins’ – starting the DFID journey

- The international journey – from ambition to ambivalence

- Evidence on anti-corruption – the struggle to understand what works

- Money laundering and illicit financial flows – the ‘getaway car’ of corruption (this note)

- The end game: asset recovery and return – an unfinished agenda

- The UK Overseas Territories and global illicit finance: the peculiar British problem

- Working with other parts of government … when they don’t want to work with you

- The UK’s changing anti-corruption landscape – new energy, new horizons

- Keeping the vision alive: new methods, new ambitions (final note)

- Those who are less sophisticated have tripped up at this first step. In one case in an English Midlands town in the early 2000s, money launderers of drugs cash used a kebab shop for commercial cover. They placed their money there, making it look as if it was the proceeds of sales. It did not take long for police, who had put the shop under surveillance and counted the customers, to show the vast mismatch between the supposed takings and the number of kebab buyers.

- Other regulated sectors include real estate agents, accountants, lawyers, and casinos. Yet experience shows that these sectors rarely report ‘suspicious’ activity.

- As recently as the early 2000s, Nigerian money launderers were reportedly still able to simply bring suitcases of banknotes to London and deposit them over the counter at certain branches of some well-known banks without many questions being asked. Things have at least moved on a bit since then.

- Note that DFID observed the principle of the independence of judicial proceedings by not being involved directly in funding the prosecution stage. DFID made it clear to our law enforcement agencies that they held complete and unfettered operational autonomy over the choice of who to investigate and prosecute. This was an important safeguard against accusations that decisions on cases were ‘politically influenced’. Law enforcement independence on these matters is an important factor to maintain. DFID merely provided the tools to take action.

- DFID drew GFI’s attention to a UK Office of National Statistics admission in 2014 that the UK had misreported its country destination trade statistics since 2009. This meant, for example, that the UK had under-estimated its exports to the US by more than £40 billion over the period, representing 20% of total UK exports to the US up to 2012. If the UK can make such errors …