Looking back over his two decades of anti-corruption efforts as a senior anti-corruption adviser in DFID from 2000 to 2019, Phil Mason concludes in part 1 of his U4 blog series that:

‘Dealing with corruption presents challenges to any practitioner who sees development primarily as a technical problem that can be solved by technical responses. Corruption needs to be viewed as an intensely political phenomenon, with responses crafted accordingly.’

This paper explains why corruption is an ‘intensely political phenomenon’. Rather than focus on the narrow concept of political (or ‘grand’ and ‘high’) corruption – wrongdoing in the election process, or undue influence through party financing or political donations – we explain how a range of corrupt acts may be politicised. That is, how they become embedded in how politics functions: how power is allocated, how decisions are made, and how institutions operate. Using insights from across the current literature, we aim to demonstrate that corruption is politics by other means, whether in a specific sector or across the board. Taking this systemic perspective, we identify why and how corrupt acts become politicised: when the spoils of corruption are sought and reinvested, not for personal enrichment, but to maintain and enhance a corrupt leader’s hold on power. While there is no blueprint for the politicisation of corruption, the process has common characteristics across different countries.

The paper is divided into two parts. The first part explains the politicisation process. It demonstrates the methods, organisation and consequences. It also explains how anti-corruption can be politicised, how anti-corruption can be hijacked, manipulated, and weaponised to serve the interests of corrupt political networks. The second section outlines how anti-corruption can be more astute in areas where corruption is highly embedded in the political system. We suggest a two-pronged approach with targeted, direct anti-corruption and more indirect efforts to build accountability attuned to political incentives.

1. The politicisation process

The use of corruption in politics

Personal greed may amplify it, but politicised corruption has a rationale beyond ‘private gain’. The spoils are not just for personal enrichment but rather to win, stabilise and extend political power. Corruption is an instrument that establishes patronage systems, builds loyalty, pays off rivals and opposition, co-opts accountability institutions, buys votes, and buys immunity from prosecution. Politicised corruption extracts resources, and invests in and maintains the structures, networks and tactics that politicians use to maintain and extend their hold on power.

‘Extractive and power-preserving political corruption’, a book chapter by Inge Amundsen, demonstrates the interdependent dynamics of extraction and power preservation, and provides several examples. It says that, for an environment to be characterised by politicised corruption, there should be evidence of both kinds of dynamics. To understand how these dynamics manifest, the chapter outlines not only the corrupt methods used to extract resources but also how corrupt methods are used to preserve power. These methods are detailed below.

Extraction

The most common forms of corruption used to extract resources from the economy and the population are:

- Soliciting bribes (money or favours) paid to a political power-holder (in person, or to their family members, organisation or the ruling party), normally by national and international companies or private individuals in exchange for access to natural resources, concessions, state contracts, or privileges such as monopolies. Procurement and large infrastructure projects are known to be particularly vulnerable – for example, the ‘arms deal’ scandal in South Africa, where vast amounts of cash were channelled from arms dealers through local companies and brokers to politically connected figures.

- Embezzlement is the theft or misappropriation of state assets (funds, property and services) by someone in authority in a public institution. One well-known high-level embezzlement case is Malaysia’s former Prime Minister Najib Razak who was accused in 2015 of channelling more than RM 2.67 billion (nearly US$700 million) to his personal bank accounts from the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), a government-run strategic development company.

- Fraud is when power-holders either play an active role in concealing or intentionally misrepresenting facts (including their own involvement), or take a share of payment or reward for ‘closing their eyes’ on economic crimes. The establishment of anonymous ‘dead meat’ companies by regime insiders is an example of fraud, frequently seen within the oil sector.

- Extortion is the use of force, threats, harassment or persistent demands to extract money or other resources from individuals, groups and businesses. Roadblocks (used to extort money from motorists) and land-grabbing are common strategies. One of the most high-level and violent extortion examples is the ‘nationalisation’ (outright seizure) of white farms in Zimbabwe and their redistribution to the members of the ruling elite. Another form of extortion is ruling political parties (or coalition partners or prospective ruling parties) putting pressure on businesspeople and private companies to finance political party organisations and campaigns.

Power preservation

It is easier to stay in power when your opponents are diminished and your ranks of supporters swollen. When accountability is weaker, you can subvert the democratic institutional checks and balances. Power-preserving corruption seeks to achieve this through:

- Buying friends and the opposition.This includes some well-known tactics such as favouritism (or nepotism), patronage and cronyism. For instance, Khisa8992dc63eca5 describes how the Ugandan president has been buying parliamentary and ruling party support: ‘In particular, when there is a controversial legislation before parliament, MPs are paid money under the guise of ‘consultation’, even when there is no necessity for consultations and when the MPs do not carry out any consultations.’

- Buying elections can mean bribing the electoral commission and high court to give favourable decisions. During election campaigns, candidates can also pay their party ‘militants’ to chant the candidate’s name and slogans louder than the others, and to pay them to commit acts of thuggery, intimidation and violence. Vote buying or ‘handouts’ is also a common practice in many countries.

- Buying impunity from judges, courts, auditors general, or anti-corruption agency commissioners is another tactic. In a large number of cases, the courts ‘cannot find evidence’ or they find some (trumped-up) technical reasons to dismiss the corruption cases against the politically connected and powerful, suggesting that the courts are under political influence.

Not all corrupt acts are part of this extraction–power-preservation dynamic. Bribes paid to avoid traffic fines or to access administrative documents, or fraud schemes and embezzlement involving public officials can remain for private gain and immediate consumption. There is no reinvestment of those resources in power preservation.

Assessing which forms of corruption are politicised can be difficult because seemingly ‘non-political’ forms of corruption may be linked to political networks, which have extended their reach into lower levels of administration and service delivery. For example, petty corruption in education, health, or taxation can sometimes comprise a pyramid of upward extraction through clientelist networks, through which small bribes and embezzlements amass into generous money or gifts for high-level political actors. Usually the more clientelism, nepotism and cronyism within a particular sector or unit, the more likely it is that corruption will be politicised, and part of the system of extraction and power preservation.

The role of informal policy arenas and networks

The cycle of extraction and power preservation requires planning and implementation that operates outside of the formalities of government. This is why the level of political corruption is high where formal frameworks are weak and informal spaces are stronger. Informal spaces can be hidden beyond the public realm of formal procedures and institutions, and it is in the interests of political corrupt actors to enlarge and develop these ‘informal spaces’ to evade formal accountability. This creates what the World Bank describes (in the Development Report of 2017) as informal policy arenas. Examining informal politics is therefore key to understanding political corruption.

Politicised corruption also relies on networks, with key players – such as politicians, government ministers, senior civil servants and other elected, nominated or appointed senior public office holders – generally found at the highest levels. Yet, some of the most powerful ‘political’ actors may not even be elected – they could be businesspeople, military leaders, senior bureaucrats, or figures from organised crime. These networks comprise what the Democracy in Africa coalition describe as shadow states.

Sarah Chayes has analysed these structures of corruption in more detail, looking closely at how corrupt political networks span the political and private sectors. A U4 study applied social network analysis to map a corrupt network in Pelalawan in Indonesia and showed how forestry corruption networks are remarkably broad and far-reaching. Powerful state actors held monopoly control over key resources, making them principal players, but they were assisted by a raft of ‘grey actors’ in the private and public spheres who utilised their specialised skills in law, surveying or accounting to enable the scheme to continue. Likewise, Claudia Baez-Camargo and colleagues examined informal political networks to demonstrate that political elites proactively build informal networks based on reciprocity, loyalty and trust, often through co-opting strategic individuals.

These structures can be organised in different ways. Michael Johnston distinguishes between different syndromes of political corruption, which vary according to the strength of the political and economic institutions, and the degree of concentrated power. In fragile states, for example, where institutions are weak, we are likely to find political corruption organised as ‘official mogul’ systems, characterised by more concentrated and pyramidal organisation, or ‘oligarch and clan’ systems, where power is more diffuse and competitive, as different networks compete for access to power and control over resources.

The organisation of politicised corruption can also span national boundaries. Political corruption in one state can be facilitated by professional enablers within international banking, consultancy companies and law firms. In certain cases, corporations, banks and intelligence agencies operating from the Global North have been at the apex of structured corruption. In Apartheid Guns and Money, Hennie van Vuuren documents how money laundering schemes in apartheid South Africa were orchestrated by Western politicians, CEOs and secret lobbyists.

Corrupt elites can also be strengthened by the flow of development aid from external donors. A World Bank paper on elite capture of foreign aid reveals that aid disbursements to countries coincide with sharp increases in bank deposits in offshore financial centres known for bank secrecy and private wealth management. The implication is that some foreign aid to highly aid-dependent countries ends up as part of the extraction–power-preservation spoils for political elites.

The systemic consequences

That some forms of corruption serve basic political functions and are the result of organisation is part of the reason corruption is often described as systemic: it becomes the rule of the games in political systems. Corruption becomes embedded as a self-reinforcing logic: when corruption is relied on as a political tactic, the more political actors see its advantages, and accountability institutions become hollow and powerless. There are few incentives for political actors to undermine the benefits or break the system, and so politicians, parties and would-be reformers become stuck. Therefore, corruption is often described as being partly a ‘collective action’ problem.

This trap can lead to far-reaching consequences for political systems. One U4 study that draws on research from Bolivia and Mozambique describes how the abuse of state resources for re-election damages democracy. Moreover, political participation is compromised as the power to mobilise can be skewed to the side of the corrupt. Corruption-inducing forms of collective action, such as patronage networks, overwhelm more constructive forms of social organisation, such as transparent and open political parties or legitimate interest groups, that are crucial for a functioning democracy.

It can also encourage systemic institutional decay where the legislature, administration and judiciary become subordinate to the interests of political elites, and therefore are unable to fight corruption. Richter and Wunsch describe how this kind of ‘state capture’ exists in Serbia, resulting in selective application of rules, inability of enforcement institutions to achieve autonomy, and public policies being made to serve particular interests rather than the public good. Ultimately, it can lead to the suppression of democratic institutions. The U4 publication (Rethinking anti-corruption in de-democratising regimes) demonstrates how corruption is an important part of the toolbox for would-be autocrats in their pursuit of unchecked power.

The politicisation of anti-corruption

The flipside of corruption being politicised is that anti-corruption is also political, even though it often presented as an endeavour distanced from local or global political processes. Interventions that aim to reduce corruption can be counterattacked and politicised in different ways, leading to unintended or counterproductive outcomes.

Political counterattack

As anti-corruption efforts advance, the ruling elites who use corruption to preserve power will start thinking about how to break free from those constraints. Surveying anti-corruption efforts, Fisman and Golden conclude that the corrupt will always seek to protect their interests, and that every ‘program elicits a strategic response by those who orchestrated and benefited from wrongdoing in the first place.’

The ruling party's responses will depend on their power and position and the techniques available to them. Powerful actors may be subtle, using their official position to obstruct anti-corruption efforts through inaction or disruption, perhaps at the same time as rhetorically championing those same efforts. Political actors can deploy 'roadblocks' to reform, ranging from simply not turning up to meetings, to publicly denouncing reform interventions as politically motivated. A common result of this kind of interference is ‘empty shell’ anti-corruption institutions and unimplemented laws. In Europe’s Burden: Promoting good governance across borders, Mungiu-Pippidi describes how disputes over Romania’s vast anti-corruption reforms corroded the cross-party consensus, leading to eventual stagnation and regression.

Corrupt politicians will defend their vital interests vehemently, and sometimes violently. Extralegal manipulation beyond the law can also be part of the response. Those pushing for reform can face retaliation from political actors, being forced to leave their position. They can be threatened, arrested, or driven into exile. Journalists and campaigners are particularly vulnerable. The U4 report, Managing a hostile court environment, describes how judges and other legal professions have been attacked.

Weaponising anti-corruption

As well as tactics of inaction, disruption and violent resistance, corrupt political actors can also hijack and weaponise the anti-corruption agenda and efforts. For instance, any anti-corruption reforms undertaken can have ulterior motives: they can be used to tarnish and target opponents, and remove institutional checks, which, ironically, can make it easier to pursue corruption.

Accountability institutions charged with supporting the common good and upholding the rule of law can be hijacked, captured and weaponised. Anti-corruption commissions and special corruption courts, along with tax authorities, the police, courts and other institutions, can be turned into a weapon for private interests. They can be ‘bought’ to intimidate opponents and rivals, and to secure impunity and protection for leaders, their allies and cronies. In Uganda, both the anti-corruption commission and the tax authorities have been used to curb the opposition party. In Rwanda, after she announced her candidacy for president in 2017, political activist Diane Rwigara was disqualified from the election and detained – along with her mother and sister – for alleged tax evasion.e881ef7983b4

When used in this way, anti-corruption efforts can backfire. The U4 report on artificial intelligence outlines the risk of new surveillance technology, which can be effective in predicting or revealing misconduct or abuses of power, instead being used as a tool for control. This U4 political economy analysis of Cambodia suggests that recent anti-corruption reforms have been critical to consolidating power in the hands of the ruling Cambodian People’s Party.

International interests politicising the ‘fight’ against corruption

International development cooperation is not isolated from economic, security and geopolitical concerns. Anti-corruption efforts are restrained by, and can be overruled by, political, security and economic interests of donor country governments. This can include implicit support for corrupt ruling elites in partner countries. In a U4 report, Twenty years with anti-corruption, Phil Mason describes the highly complex political character of anti-corruption when he writes: ‘UK Overseas Territories (OT) such as British Virgin Islands and Cayman Islands have a well-known reputation for facilitating money laundering and the movement of illicit finance.’ He asks rhetorically: ‘Why does the UK allow this adverse behaviour, which taints the wider UK reputation?’ The answer is bound up in broader questions of geo-politics, specifically that ‘taking stronger action could rebound in far-off parts of the OT family, with political consequences too unthinkable to bear’ (p.12) for places like the Falklands and Gibraltar.

The political interests of western states also shape the anti-corruption policies that emerge. For instance, the targets of anti-corruption policies have shifted. Initially, the policy focus was on businesses and corporations that were seen as culprits that could be brought to court under national and international legislation banning the bribery of foreign public officials.ee1c1c428368 Yet, in 2003 the UN Convention Against Corruption shifted the focus to national governments, with the emphasis on preventive policies and government liability. This change has not escaped criticism. Brown and Clokeaf34556f7aae decry the neoliberal perspective of this approach that has a ‘blindness to the complex interplay between economic liberalisation, political power, and institutional reform.’ It has been questioned whether this is a ‘natural’ development or a deliberate strategy of refocusing attention away from the developed world's business elites to the developing world’s political elites. Kolstad et al12b45cc96280 note that ‘the role of private agents in corruption has been neglected relative to public officials’, and ‘the traditional donor focus on corruption as a problem of accountability and poor governance may be too limited'.

2. Responding to the politicisation of corruption

Getting the politics right: a two-pronged approach

Where corruption is politically embedded, anti-corruption efforts are constantly at risk of facing pushback and unintended consequences, or of being ineffective. This situation may be common in fragile states, but is also present in relatively stable, economically productive countries. To avoid these risks, we suggest a two-pronged approach revolving around direct anti-corruption interventions and more indirect accountability reforms.

Direct anti-corruption efforts focused on specific corruption risks and challenges are necessary to provide central anti-corruption activity where discourse and mobilisation can progress. In addition, efforts are needed to help support political accountability and build longer-term resilience. The aim is to build up sufficient answerability and sanctions so that corruption is squeezed out of politics.

Designing politically astute interventions for these two approaches requires some novel elements that mark a shift from traditional approaches. To avoid subversion by political actors, direct interventions need to become highly targeted, bottom-up and chosen according to the viability of local political conditions, rather than due to donor preferences or preconceptions of what anti-corruption should look like. Focusing on conventional forms of accountability, such as capacity building within the judiciary, parliament or other oversight institutions, could clash with ruling elites’ interests. We suggest alternative and more realistic approaches that can align with politicians’ incentives.

Evidence points to a clear synergy between direct approaches and accountability; the strength of the broader accountability environment determines the effectiveness of direct anti-corruption interventions. For example, Adam and Fazekas’08e29b417bfb review of information and communications technology (ICT) interventions in anti-corruption concludes that effectiveness depends on the strength of pre-existing accountability mechanisms. It is therefore not an ‘either/or’ debate: effectiveness depends on combining direct and indirect approaches, and new ways of working for donors.

A. Direct anti-corruption efforts

When corruption is highly politicised, the immediate problem is that it will be in the interests of political elites, bureaucrats, businesspeople, criminal networks, and multinational corporations to withdraw the support needed for effective direct anti-corruption reforms. We argue therefore for a targeted, sectoral and bottom-up approach based on mobilising a broad-based critical mass to support reforms. To do this, practitioners should analyse specific contexts, work on mobilising coalitions, and support new forms of capacity building.

Target the most feasible areas

‘Lack of political will’ is often used as a shorthand explanation for failed anti-corruption efforts. The not-altogether-useful phrase implies inaction by political elites, but it does not explicitly show how powerful actors deliberately resist, circumvent, or instrumentalise reforms. Political will exists on a scale from support – a commitment to initiate and implement reforms – to a hostile desire to block, subvert and hijack reforms. Where political actors are positioned on this spectrum depends on their interests.

When corruption is highly politicised, integrity-building programmes can be more effective by concentrating on sectors or areas of public administration where anti-corruption does not threaten the interests of power-seeking political actors and where there is some support – from citizens, businesses or other groups – to push forward reforms. This targeted approach may disappoint those who believe that corruption should be fought across all fronts, but experience of anti-corruption efforts being thwarted shows that it is prudent to accentuate viability. For example, the Anti-Corruption Evidence consortium led by Mushtaq Khan and his team at School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS) University of London said that, for anti-corruption strategies to work, they must be feasible to implement.

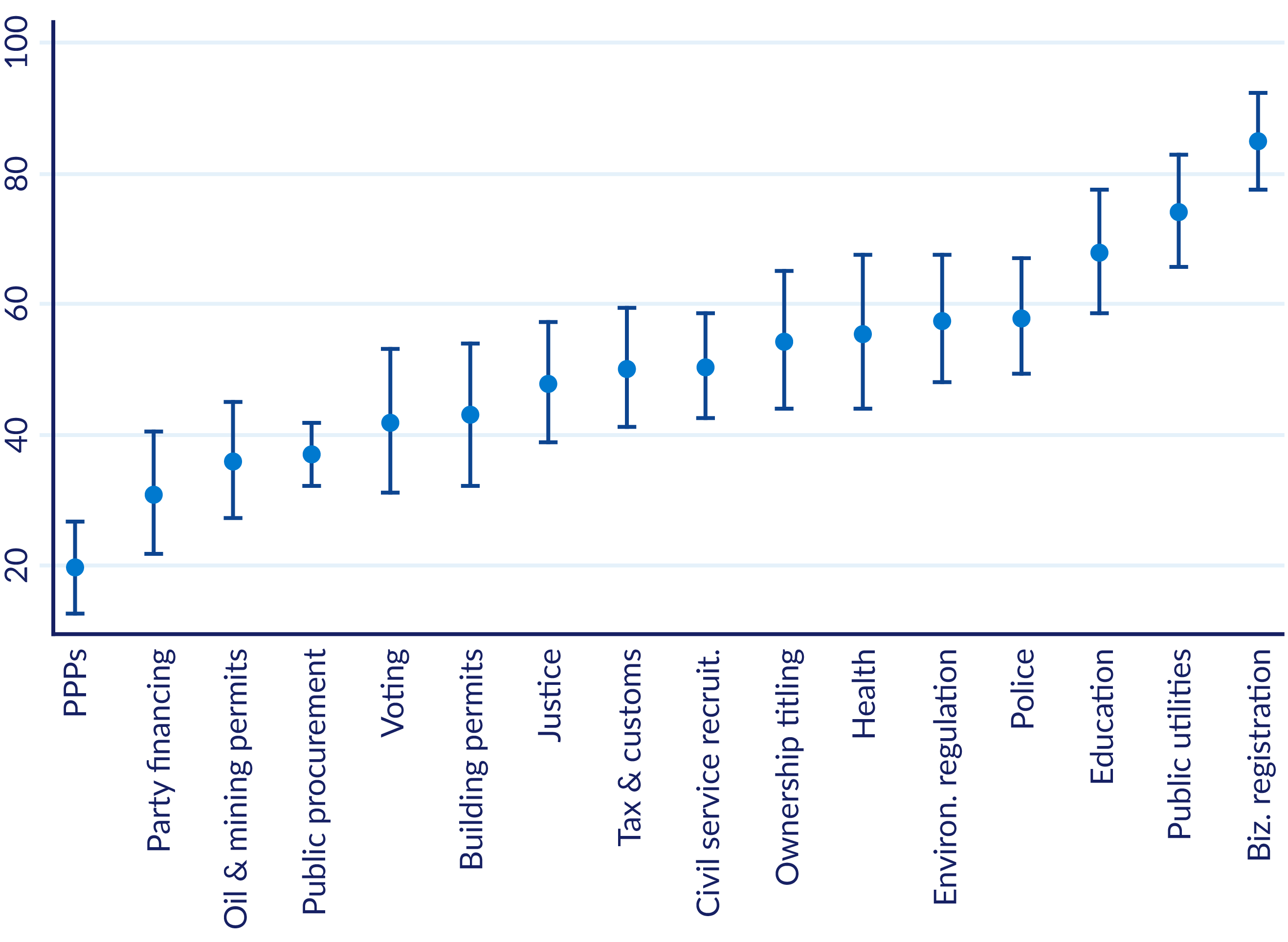

Taking its cue from that emphasis, a U4 analysis by Luca J. Uberti asks whether blanket anti-corruption efforts often fail due to economic constraints and political resistance. Uberti's report assesses whether an anti-corruption practice is either central or peripheral to the political stabilisation strategies used by political elites in Albania. Through expert surveys, the aim was to identify and attack a political settlement’s ‘weak points,’ where organised opposition to reform was likely to be low enough to make reform feasible. The feasibility ratings are presented in Figure 1 below. The sectors believed to be most amenable to anti-corruption interventions include education, public utilities, and health and environmental regulation. By contrast, public procurement and public-private partnerships are among the sectors where anti-corruption interventions are most likely to face resistance by powerful groups.

Figure 1: Estimated feasibility of anti-corruption interventions in Albania, by sector

Source: Uberti, 2020

Analysis also demonstrates the types of interventions that can be aligned to political incentives. U4’s analysis of Cambodia’s anti-corruption regime between 2008 and 2018 suggests that many anti-corruption reforms may be blocked, especially those that strengthen civil society or social accountability. However, opportunities may exist to create anti-corruption coalitions supported by social groups, particularly at the commune level.

Mobilise the winners of reform

Identifying a reform area that is politically viable is not enough; even sector-specific reforms can face pushback. And so, another important task for practitioners is to understand the political dimensions of particular sectors or subsystems. This can help galvanise actors and generate the core ingredients for reform: legitimacy to change, influence over others to make changes, and a capacity to expand a network of supportive actors. Groups must be motivated to ‘keep up the pressure’. Mushtaq Khan and colleagues stress how these kinds of coalitions can spur horizontal enforcement of reforms. The Building State Capability faculty at Harvard University describe this as being about initiating, maintaining and growing an ‘authorising environment’ for reform.

Donors should emphasise local action and leadership to keep up the pressure. As Booth and Unsworth stress: locals are more likely than outsiders to have the motivation, credibility, knowledge and networks to mobilise support, leverage relationships and seize opportunities in ways that qualify as ‘politically astute’. Acting as a convener and developing an infrastructure for this collaboration can be an important area of responsibility for donors. The size and shape of the group of actors engaged will vary for each case.

A crucial element is to avoid preconceptions of where political and social influence comes from, because this will vary according to context. It may be insightful to understand how norms and informal structures may shape influence. Village elders or customary authorities may, for example, be more influential than elected mayors. The authorising environment may have a geopolitical angle, with external powers, for example, China, exerting influence.

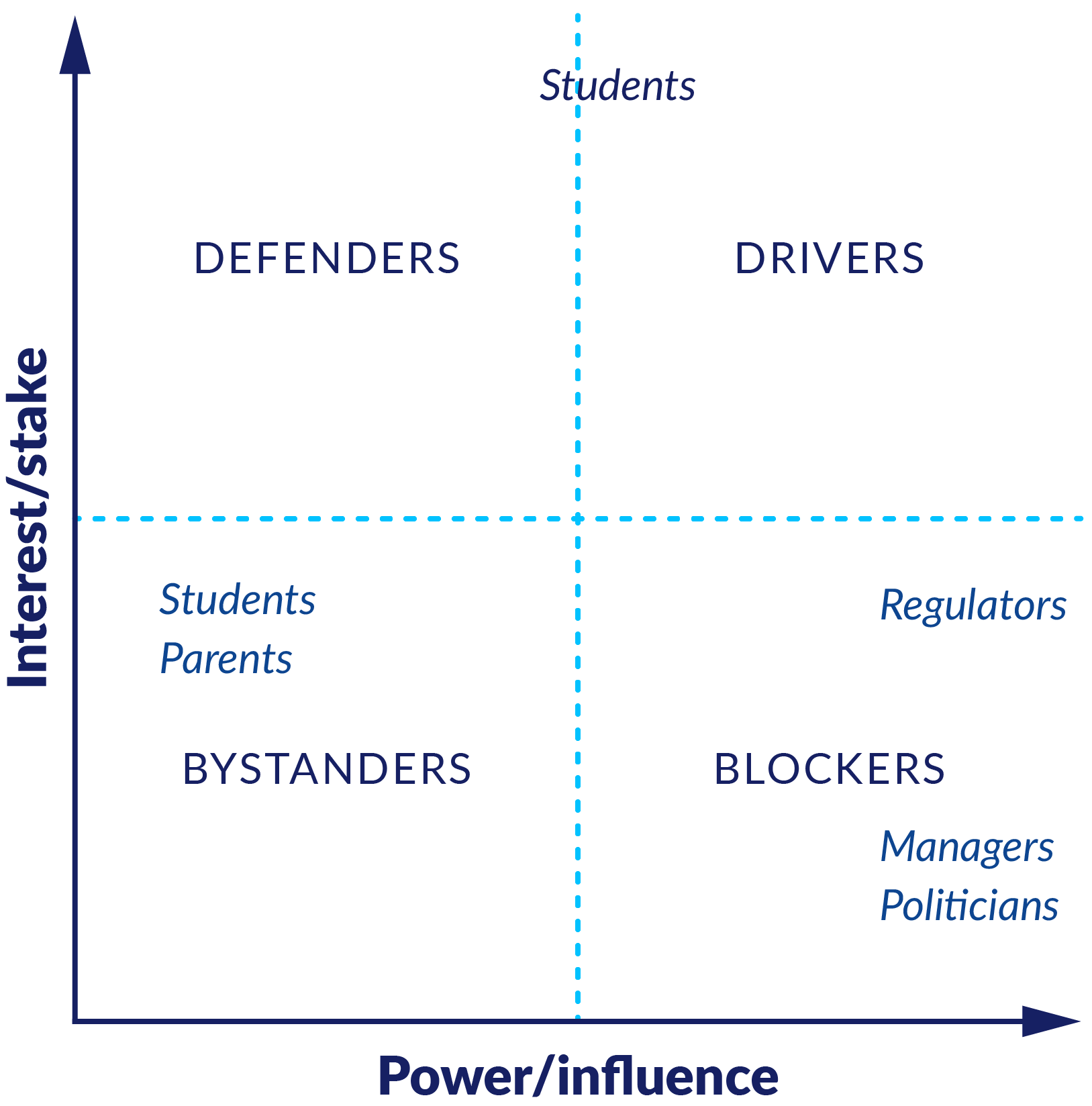

The heart of these strategies is about mobilising those who gain from reforms – that is, those who lose from corruption. Practitioner should identify who may win from reform, and who has the influence to change specific issues. Successful strategies do not always depend on persuading those in high office; critical mass can also shape action. For example, a U4 paper on Albania shows that, of all the actors involved in the education sector in Albania, students are the most likely to be effective at pushing reform.

Figure 2: Actors in Albania’s education sector: Power–interest matrix

Source: Uberti, 2020

A close analysis of the context is important. In Albania, the research showed that some students (especially poorly performing students) might have an interest in seeing corruption continue, as it allows them to reduce their workload and pay their way through exams. Thus, many students can be little more than bystanders in the process of change. Yet the research also pointed to the potential of this group for action and intervention. For example, the concessions extracted by recent student protests (a leadership reshuffle in the Ministry of Education, a rollback of a proposed student fee increase) show the potential power and influence that the student movement can play in driving reforms.

One anti-corruption programme that seriously nurtured an authorising environment is the asset-recovery support programme funded by Department for International Development (DFID) and the EU – Strengthening Uganda’s Anti-Corruption Response. The programme, which ran from 2015–2020, adopted an unusually long one-year inception phase. This enabled it to better understand Uganda’s patronage system and identify actors and institutions that could be harnessed to promote changes in practice.

Build new forms of capacity

Coping with the politics of anti-corruption also requires skills and capacity that may involve unorthodox forms of support. One form of skill-building could aim to enable practitioners to take a more adaptive approach to anti-corruption. The reasoning is that standard linear ‘plan-implement-report’ logframes of anti-corruption may not be well set up to deal with political pushback, whereas adaptive approaches that include greater flexibility and emphasis on ongoing learning may be better suited to cope with ‘political surprises’ as reforms play out. However, training practitioners to develop the confidence to be adaptive is not easy and needs to be worked on. Recent thinking by the Overseas Development Institute suggests that senior management could develop ‘safe spaces’ within organisations, where staff feel secure to experiment with more adaptive approaches to programme work.

An Open Society Foundations report on seeing new opportunities within anti-corruption identifies further key areas of support relevant for coping with the politics of anti-corruption. As political backlash is a risk, one key area of aid can go toward reinforcing care and protection structures. Interventions could provide resources for digital, physical and psychosocial security.

Extra funding for legal advice and protection might be needed if reformers are arrested or defamed in by the media. Funding peer self-help networks can help sustain reforms in the face of opposition, providing solidarity, resilience, information-sharing, and a sense of mutual care for members. The Corruption Hunter Network, a solidarity group for anti-corruption legal professionals supported by the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad), is a globalised version of such a network. A U4 study on networks of anti-corruption authorities suggests that there is scope to improve these kinds of peer networks.

Another different intervention would be to support reformers' ‘change management’ capabilities. Such an approach rightly views anti-corruption efforts as a complex process of coordination and collective change, rather than just a technical question of establishing the right institutional procedures or laws. Anecdotal evidence suggests that support for reformers to steer complex change is seldom formally part of the anti-corruption support package. The Open Society Foundation report suggests that specific ‘political coaching’ could be important. This means supporting a network of reformers with local expertise on how to navigate delicate political and administrative processes. This is where knowledge may be gained from former politicians, academics, journalists, or lawyers familiar with these processes.

B. Developing accountability constraints

Strengthening the accountability of political leaders can help to enhance representation, inclusion and justice. Pitching anti-corruption within a broader framework of building accountability has additional advantages.93c21d758241 Accountability has possible beneficial outcomes beyond anti-corruption alone, such as efficiency of public spending qualities that expand the potential range of political support for reform.4fd299c2f4e4 Also, accountability is multidirectional: it emanates from various sources and can be exercised in many combinations, expanding the scope for a whole range of interventions that go beyond anti-corruption alone.

Accountability forces political actors to answer for their actions. When standards are violated, accountability also means the ability to sanction that violation. The immediate dilemma is that those in power who gain from the corrupt system have few incentives to develop accountability that would directly constrain their own sources of advantage. This is especially true of attempts to build up conventional forms of institutional accountability, emanating from the parliament, judiciary, ombudsmen, or supreme audit institutions, as well as more specialised anti-corruption commissions and courts. Attempts to enhance these institutions can deplete the sources of extraction and power preservation, and so can be undermined or not permitted by those in power. Evidence points to these institutional forms of accountability struggling to act as autonomous constraints in highly corrupt countries.6ab849e2cf19

The other established route focuses on more vertical forms of accountability. Large investments have been made to support to anti-corruption non-governmental organisations (NGOs) or social accountability mechanisms. Supporting organisations can create bursts of answerability but they have struggled to instigate more deep-seated change. The evidence suggests that these interventions are effective only when the overall system of accountability is strong.f5e3b8df1b0e

This does not mean that these conventional forms of accountability are unimportant. In countries with a credible rule of law and with committed political leadership, then these accountability institutions should be supported as a priority.

Yet, in contexts of high politicisation, accountability measures will only fit to context when they provide at least some incentives for powerful actors within government or as part of broader society. We explore what these incentive-driven accountability measures can be, based on the key criteria that there is empirical evidence to support the effectiveness these interventions to build accountability and ultimately control corruption. These are meant as initial possible options, and their viability should be assessed country to country.

We organise the options into three building blocks of accountability: access to information; new forms of collective action; and smart sanctions. Taken together, these foundations suggest a multi-sectoral agenda for anti-corruption: as well as connecting with other government departments, practitioners need to be involved with those promoting democracy, as well as sectors such as welfare, media support, ICT and infrastructure development. These practices are not about short-term programmes. Many of the options imply incremental approaches but require long-term and credible backing.

Table 1. Overview of some indirect accountability interventions

|

Purpose |

Aim |

Types of reforms |

|

Access to information |

More equitably distribute information about the workings of government |

|

|

New forms of collective action for the economy, public services and representative organisations |

Overcome the reasons why social groups do not organise for more accountability to generate stronger collective pressure for more accountability |

|

|

Develop alternative sources of sanctions |

Stronger sanctions mean corrupt actors may self-restrain and norms around accountability standards become internalised |

|

Improve access to information for citizens, media

Information is power. Privileged knowledge of government tenders, procurement processes, job openings, public welfare spending and legal reforms give political actors more opportunities to pursue extraction for gain. Those with privileged access to information seek to hoard this advantage. Restricting information flows enhances a politician’s opportunities to cut deals, solicit bribes and develop fraudulent schemes. Being able to hide the workings of government provides further foundations for systemic corruption. Interventions aim to more equitably distribute information and create openness, so that politicians are more answerable. Corrupt politicians have few incentives to implement direct interventions for transparency, such as freedom of information acts or public registers. But the suggestions below indicate there are incentives to pursue policy reforms that provide for broader openness as they can contribute to economic growth, better welfare outcomes and budgetary savings.

Support the basics of a free press

Studies by Brunetti and Weder8ef1388ec535 and Ahrend,098b82ff622a among others, show that a freer press leads to less political corruption, and a lack of press freedom leads to higher levels of corruption. Media coverage of corruption provides accountability by revealing information that can lead to investigations and trials, information that can foster a social climate against corruption, and that can act as a platform for dialogue and debate and encourage new accountability initiatives.

Enhancing the infrastructure of a free press means developing legal frameworks, promoting the press plurality, supporting media’s economic sustainability, advocating for access to information, protecting sources or whistleblowers. Supporting investigative journalism is also important.

Supporting a free press around elections could be strategic. A free press should be able to garner broad political support. It aligns with international norms, and, as this report on press freedom by UNESCO demonstrates, there are correlations between a free press and better outcomes in health education, government effectiveness, and a less violent society. Despite the importance of a free press for accountability, several surveys suggest that the issue languishes low in terms of development agencies’ governance priorities.

Support internet access

Analysis for the World Bank suggests that the internet’s emergence has played a role in reducing corruption. The internet provides platforms for the generation and dissemination of information around corruption. It can help encourage mobilisation against corruption, including through the use of social media. Jha and Sarangi’s cross-country analysis of more than 150 countries shows that social media has a sizable impact on corruption. The authors suggest that the effects of social media are not contingent on freedom of the press; social media can impact on corruption in countries where the press is free, and also where press freedom is repressed.

While the evidence suggests that the internet does not cause economic growth, if used productively, the internet can help serve goals of economic development. The increase of internet use in West Africa had a positive relationship with human development. Internet infrastructure support for those countries that are both highly corrupt and have poor internet penetration can support accountability.

Digitalise public services

ICT reforms to administration can bring greater openness and predictability to information flows. Digital public services means that official decisions can be tracked, reducing the scope for discretion. ICT can be used to monitor funding flows and maintain transparent records of government interactions. Empirical evidence shows that e-government seems to be associated with lower corruption. For political actors, the digitalising of public services can be financially attractive. Kenya’s public sector digitalisation reportedly saved the government US$290 million over four years.

But these kinds of reforms are not universally suitable. Digital reforms may exacerbate digital divides and can be captured by elites. Accountability is often dependent on the existing strength of enforcement mechanisms and technological know-how.0ceb19937356 Politicians should not have incentives to abuse the possibilities that reforms offer.

Develop new forms of collective action for the economy, public services and representative organisations

Stronger constraints on accountability exist when society is collectively organised against corruption.ac3681cc0190 Helping social groups act in a collective way against corruption requires policy more far-reaching than, for example, funding NGOs to start awareness-raising or social accountability initiatives. It is about laying an infrastructure for combined action in specific areas, so that the force of collective pressure can incrementally lead to accountability constraints. Many of the interventions should be aimed at overcoming the reasons why social groups do not organise against corruption, and so should provide credible and stable incentives to mobilise.

Support collective action in the economy

When cronyism, a symptom of politicised corruption, structures relations between firms and the state rather than rule-based and transparent frameworks, there is normally a majority of businesses that lose out. This may be an important coalition for change, but it is prevented from organising against discriminatory privileges and rents due to the absence of a credible coordination mechanism.

Businesses can be influential because they pay taxes, can mobilise employees, and observe how governments act. Collectively organising business around formal associations can help them forge a credible collective position to educate, advocate and collaborate for more accountability. Interventions can help support the legal structure of associations, capacity-building around advocacy and planning, as well as material support for collective mobilisation. In theory, this space is beyond political sabotage.380f3d8ae37a The kinds of businesses organised depends on contextual considerations about which firms would have a self-interest in collective action. This U4 study about ethnically plural societies suggests that, in Guyana, it is small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs), rather than larger firms, that have a strategic role to play to contest politicised corruption such as clientelism. A playbook developed by the United Nations Global Compact provides guidance on how businesses can pursue anti-corruption collective action.

Develop trust in welfare institutions

When social groups lose trust in public institutions to deliver services fairly, they seek more personalised and informal relations with politicians. The more public services are delivered through patron-client relations, the more formal procedures are ignored or bypassed. Accountability is hollowed out, creating an environment for politicised corruption to flourish. There is clear evidence that corruption is correlated with declining trust in public institutions.

When citizens trust institutions to deliver welfare, they may begin to demand accountability and improvements channelled in a public oriented way (eg, from ‘find a way to get my operation’ to ‘provide universal healthcare and better hospitals for all.’) This can trap corrupt elites. Building trust is a long-term endeavour. Entry points can be long-term investments in nurturing strong leadership and management of key welfare institutions, and making financial support conditional on better hiring procedures, with the emphasis on transparency and competitiveness.

Support political parties to develop broad-based programmes

Research by Cruz and Keefer6c1149bbf840 finds that, when countries have parties appealing to voters on a public programmes and credible manifestos, as opposed to more clientelistic electoral campaigns, they also have a well-functioning administration free from corrupt influences. This is because of the clear incentive: a non-corrupt administration autonomous from political meddling is key to fulfilling electoral promises. These parties tend to be less hierarchical. In highly corrupt settings, clientelism tends to be the dominate way political parties make their appeal. But the chance of broadening electoral appeal, especially for ‘first movers’, is an incentive to develop programmatic agendas.

Political party development is highly sensitive, but there could be some entry points. Practitioners could help parliamentarians develop credible party manifestos by connecting them with research institutes in the nation, or with peers in the region. Strengthening party grassroots structures can help translate local challenges into collective manifestos. Working with voters through certain small-scale interventions may also be important. For example, Fujiwara and Wantchekon’s883c33563305 experimental study in Benin demonstrates that holding 'town hall meetings' as conduits for informed public deliberation prior to an election reduces the prevalence of vote buying. Giving citizens ‘democratic vouchers’ that they can donate to political parties of their choosing, an initiative advocated by Julia Cagé and Thomas Picketty among others, may help collective action against clientelism.

Develop smart sanctions

Sanctions strengthen accountability, not just because they constrain individuals, but because they send signals about the rules of the game in society. When there are sanctions, corrupt actors may self-restrain and norms around accountability standards become internalised. Yet, corrupt political actors are unlikely to genuinely support efforts to enhance the oversight institutions that can punish corruption. Alternative forms of sanctioning should also be constructed.

Build up social sanctions

Social norms are ‘shared understandings about actions that are obligatory, permitted, or forbidden within a society’.f09e410f6c78 They provide the unwritten rules of behaviour, the micro building blocks of a social order. When there is strong social norm against corrupt behaviour, political actors may face social sanctions of guilt, shame or exclusion from communities. As social norms against corruption are strengthened, social organisations – media, groups of citizens, NGOs, voters, public officials, and political parties – are emboldened to strike back quickly.

Strengthening social norms against corruption is not straightforward – it is much more than awareness-raising. Tentative policy suggestions of values training, overcoming pluralistic ignorance, community dialogues, educational instruction and working with social networks can help long-term efforts to shift norms and strengthen social sanctions.

Strengthen external sanctions

Corruption is partly a transnational phenomenon, with forms of accountability exercised by external actors. States have the leverage to hold politicians to account through targeted sanctions. Masonfb448f9364be calls for aid-giving states to develop measures to target specific individuals or groups. Examples include: withholding visas to visit the donor country; exclusion orders; and restricting engagement when corrupt practice is suspected. This approach requires strong collaboration between a donor agency and other parts of the same government, as control over these ‘non-aid’ levers resides largely outside the remit of development agencies. The aim is to build up a system of disincentives. In addition, as donor countries’ domestic legal, accountancy, and banking systems can facilitate money laundering, fraud, and other forms corruption in developing countries, domestic sanctions against wrongdoers can help close that loop. Supporting frameworks such as the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative and International bribery standards can also help accountability efforts.

New ways of working

When corruption is politicised, it becomes embedded in how politics functions. Politicised corruption relies on networks, with key players at the highest levels. Anti-corruption can also be politicised. The politics of (anti-)corruption means that initiatives must be more astute in areas where corruption is highly embedded. As a final recommendation, new forms of practice should be considered to pursue the suggested approaches to more astute accountability. Beyond the obvious need for constant donor coordination, the approaches recommended in this chapter suggest a multisectoral agenda for anti-corruption. Practitioners need to connect with other government departments, they need to be involved with those promoting democracy, as well as sectors such as welfare, media support, ICT and infrastructure development. These practices are not about short-term programmes. Many of the options imply incremental approaches but require long-term and credible backing. The U4 paper by Phil Mason, Reassessing donor performance in anti-corruption, on new pathways for practice, offers some important thinking in how practitioners can depart from traditional ways of working to be better organised, responsive and sensitive to the politics of addressing corruption.

- 2019.

- Amundsen 2019.

- The US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (1977) targeted bribery of foreign government officials by publicly traded corporations or US persons. The OECD Convention on Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions (1999) also targeted national and transnational companies.

- 2004.

- 2008.

- 2018.

- Taylor 2018.

- Taylor 2018, 67.

- Mungiu-Pippidi 2015; Johnson, Taxell, and Zaum 2012.

- DFID 2015.

- 2003.

- 2002.

- Adam and Fazekas 2018.

- Mungiu-Pippidi 2015.

- ‘Building coalitions’ in the economic sector is one of the key strategies advocated by the DFID-ACE programme that researches which coalitions can make a difference across various different sectors.

- 2015.

- 2013.

- Ostrom 2000.

- 2018.