1. Introduction

Today it is increasingly recognised that integrating anti-corruption and integrity measures into the health sector can strengthen system performance, promote an efficient use of sector resources, enhance patient care, and improve public health outcomes.ffd439af6a7f Transparency and anti-corruption initiatives specific to the health sector have been pursued around the world. At global level, the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals include commitments on universal health coverage as well as on good governance and transparency.

Yet there is surprisingly little documented evidence, available in English, of what has been done, how, with whom, and with what purpose and results – and of the lessons learned. Country case studies on transparency and anti-corruption projects in the health sector are in short supply. Apart from Morocco, Botswana, Ukraine, and Tunisia, there are not many country examples that development partners can turn to for inspiration.ebe376007d83

This U4 Practice Insight is intended to help fill this knowledge gap. It presents the experience of Colombia, where health sector leaders promoted the integration of transparency and integrity measures into key sector policies and institutions in order to improve system performance and recover public trust. These efforts were supported by various development partners, including the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the EUROsociAL II programme, and, in particular, the ACTUE Colombia Project,6e62a090bcda funded by the European Union (EU).

‘Actúe’ in Spanish means ‘act’, and ACTUE Colombia stands for Anti-corruption and Transparency Project of the European Union for Colombia (Proyecto Anticorrupción y Transparencia de la Unión Europea para Colombia). The project focused initially on ‘radical’ transparency in priority areas of the National Pharmaceutical Policy. It then broadened its scope to collaborate with Invima, the National Food and Drug Surveillance Institute (Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos), seeking to turn the agency into an ‘island of integrity’ within the health sector. At this stage the project worked to pilot subnational health sector transparency initiatives, diagnose corruption risks and levels of tolerance towards corruption in the health sector, and integrate anti-corruption measures in the sector more broadly.

This Practice Insight, intended for donors and for anti-corruption and health practitioners, presents approaches, experiences, and lessons learned from ACTUE Colombia. The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 briefly describes corruption in the Colombian health sector and outlines the approach of ACTUE Colombia, looking at how the project initiatives came about and at the role of development partners. Section 3 examines these initiatives in terms of their purpose and motivations and critically reviews the results achieved. Section 4 identifies key success factors as well as challenges for the sustainability of results. The concluding section presents recommendations for future initiatives aimed at mainstreaming integrity at sector level.

2. Anti-corruption mainstreaming in the health sector: The approach of ACTUE Colombia

2.1. Background: Health sector corruption led to a crisis

Colombia, with a population of roughly 52 million, has persistent perceptions of high levels of corruption.36a3f5682fb8 This is reflected in international and national assessments and indexes from Transparency International, the World Bank, Latinobarómetro, and other sources.563ac35cdcd5 Common practices include bribery to influence legislative, policy, judicial, and regulatory decisions and the misappropriation of public funds, particularly in sectors such as health, infrastructure, mining, and education. Petty corruption exists but does not generate great public concern. The more important problem is high-level corruption, especially related to public procurement at all levels of government, which coincides with a general perception of impunity. This fosters a culture of illegality and undermines the legitimacy of the State.

A situation of widespread political corruption and patronage stands in contrast to the formally well-regulated public service. National-level indexes and assessments point to weaknesses and inefficiencies in the public administration in terms of transparency, integrity, and accountability. In addition, traditional forms of corruption have been aggravated by the so-called ‘co-opted reconfiguration of the State’, a phenomenon whereby state institutions have been systematically captured for economic or criminal purposes and to ensure impunity.0fc2fc689742

In the Colombian health sector, allegations of corruption have surfaced for many years. Corruption diagnostics on specific aspects of the system have been conducted since 2002, including studies of public hospitals and of the subsidised health insurance system for the poor.ec628f5f1411 Reporting on a 2011 study by the United Nations Development Programme, Hussmann found that ‘vulnerability to policy and regulatory capture clearly affected the whole system in Colombia, including the regulatory and supervisory bodies themselves … Procurement of drugs and medical supplies continued to be susceptible to corruption and undue influence despite reform efforts. Political interference in the nomination of hospital directors, which is supposed to be based on merit, was pervasive, with serious consequences for hospital performance.’d2691afccc24

In 2011, the Colombian health sector experienced a corruption-related crisis that severely undermined trust in the system. This was caused by the public exposure of large-scale corruption schemes, involving virtually all actors in the health system, combined with mismanagement and lack of oversight in the sector. Fraudulent practices targeted medicines for high-cost health conditions such as cancer or transplant management. Among other anomalies, the health insurance fund paid highly inflated prices for medicines, in some cases 1,000% of their market value.000974011c09 Inflated drug expenditures were a principal driver of the escalating crisis in the health system.

The Colombian state responded immediately. The Constitutional Court ordered the executive to strengthen controls, while the government decided to unify and update the health insurance benefit package and to define maximum values for drug reimbursements with data available from SISMED, the national drug pricing system (Sistema de Información de Precios de Medicamentos).

Most importantly, in 2012 the government approved its first National Pharmaceutical Policy, with a focus on strengthening national drug governance and drug information systems.37696e52d8b3 The policy identified inequitable access to medicines and poor quality of care as central problems and cited five major causes: (a) inappropriate and irrational use of medicines; (b) inefficient use of financial resources; (c) insufficient availability of essential medicines; (d) lack of transparency, low quality of information, and little monitoring of the pharmaceutical market; and (e) weaknesses in leadership and oversight.

2.2. ACTUE Colombia’s strategic approach: Comprehensive, sectoral, multi-actor, and transversal

Against this backdrop of corruption and opacity near the beginning of his first term (2010–2014), President Juan Manuel Santos requested technical support from the European Union in the fight against corruption. In response, the EU worked with government counterparts and civil society to develop ACTUE Colombia in 2012.8a8e1a1fd606 Designed with a five-year scope, from July 2013 to June 2018, the project contained a strong anti-corruption sector mainstreaming approach and targeted the health sector as a priority. Its budget allocation totalled €9,020,000 (€8,200,000 from the EU and €820,000 from the Colombian government).

The EU assigned implementation of the project to a Spanish development cooperation agency, FIIAPP (Fundación Internacional y para Iberoamérica de Administración y Políticas Públicas), through the ‘delegated cooperation’ funding mechanism. Actual implementation of ACTUE Colombia ran from February 2014 to July 2018. The main Colombian counterpart was the national Transparency Secretariat (Secretaría de Transparencia de la Presidencia de la República), which housed the project team.489a054820bb For the health sector component, the Ministry of Health (MinSalud), the Health Superintendency (Superintendencia Nacional de Salud),46a289f5d2d3 and Invima were the public sector agencies most directly involved in project implementation.

In line with its overall strategic approach, ACTUE Colombia provided comprehensive support to innovative transparency and integrity instruments for the Colombian government in general and the health sector in particular. The multi-actor strategy involved public entities (at national level and, in some pilots, at subnational level), health professionals, the health care industry, and civil society. All initiatives had as a common purpose the generation of independent and publicly accessible information aimed at promoting behavioural change to prevent corruption and build trust. For more information see Annex 1 and the ACTUE Colombia website at www.actuecolombia.net, which contains a repository of documents.

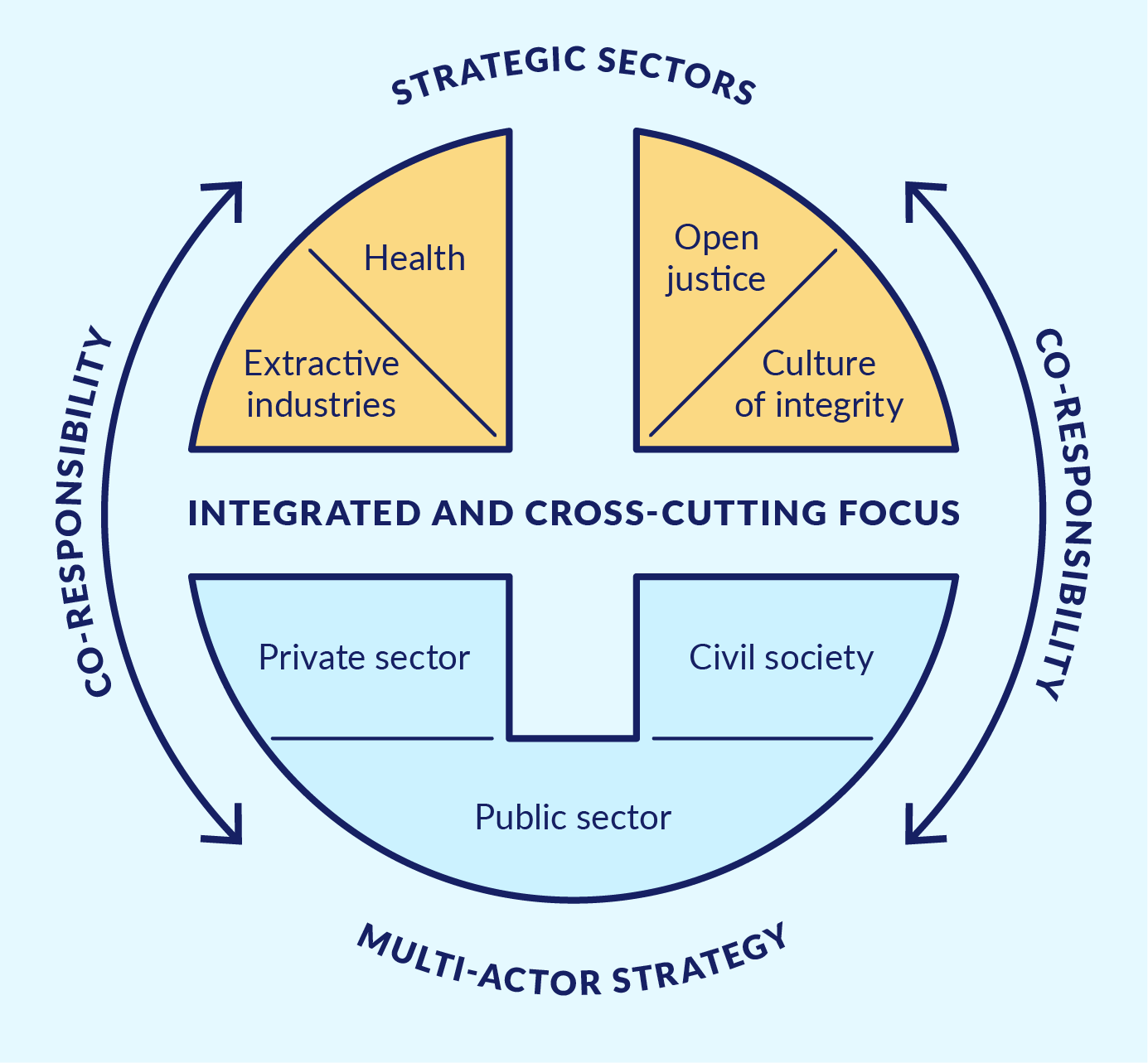

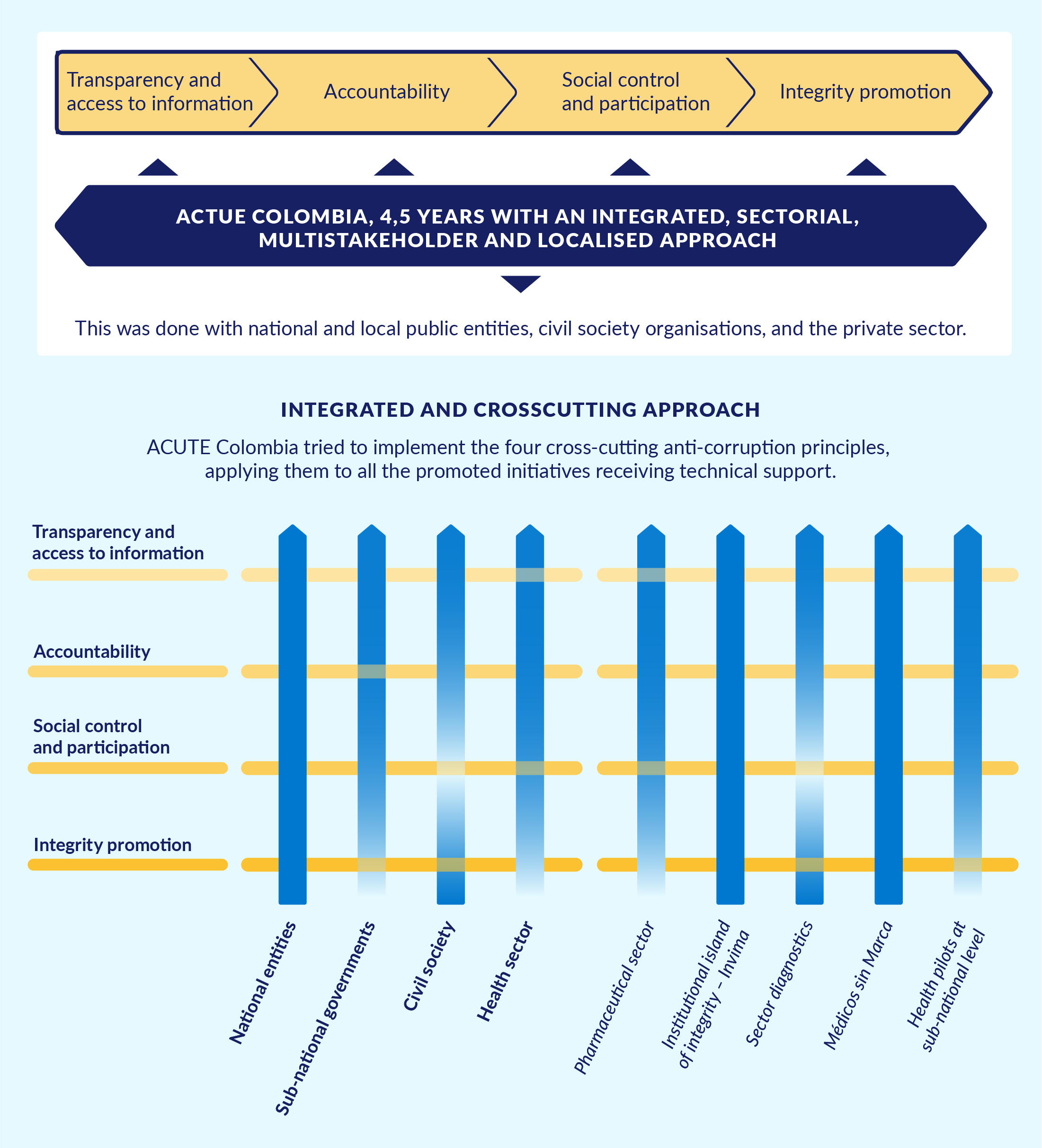

As shown in Figure 1, ACTUE Colombia sought to strengthen the anti-corruption capacities of Colombian state institutions through an approach that was comprehensive, sectoral, multi-actor, and transversal.

Figure 1. ACTUE’s cross-cutting and integrated focus

Source: Enfoque y metodología de ACTUE Colombia – ACTUE Colombia website.

Comprehensive implied that actions were pursued in mutually reinforcing thematic areas. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) framework for public integrity and key principles of the Open Government Partnership (OGP) served as overall guidance for project activities. Thus, the health sector transparency initiatives were built on normative developments and methodological guidance resulting from ACTUE’s substantial support to the Transparency Secretariat and another key Colombian government agency, the Administrative Department of Public Service (Departamento Administrativo de la Función Pública, DAFP). This support targeted implementation of the new Law on Transparency and the Right of Access to National Public Information (Law 1712 of 2014). It also sought the strengthening of public accountability and civic participation and the improvement of conflict of interest management, ethical conduct, and internal control. ACTUE Colombia also contributed to institutional capacity building and the strengthening of inter-institutional coordination around integrity.

Sectoral implied efforts to ground public integrity and transparency frameworks at sector level in order to generate tangible results. In addition to the health sector, ACTUE Colombia targeted the extractive industries sector as well as open justice and the development of a culture of integrity. With respect to the latter, a key component was the ‘island of integrity’ initiative developed with Invima.

Multi-actor implied acknowledging the co-responsibility of all parties involved. The project reached out to and worked with public sector entities, private sector organisations, civil society, and academia, bringing them together around shared areas of interest.

Transversal implied helping to build bridges between integrity approaches at the national and subnational levels. This was pursued through work with the Transparency Secretariat and the DAFP, pilots with departmental and municipal governments,85da096a5a6d and social accountability initiatives.

The assumption underlying ACTUE Colombia was that the combined application of these four strategic elements in specific sectors would promote meaningful change related to transparency and integrity, which in turn would improve sector performance and enhance public trust. The project relied on a ‘door-opener’ approach, using promising entry points with a view to expanding interventions later based on concrete results.

2.3. Transparency and integrity to recover trust in the health sector

‘Transparency, accountability and integrity are intrinsic health governance values. … These concepts are interrelated: transparency and accountability are critical for efforts to ensure integrity and deter corruption. Transparency requires that citizens be informed about their rights and entitlements, and how and why decisions are made … Accountability requires institutions to explain and make understandable their performance in achieving goals and addressing the needs of the public, in comparison to standards and commitments made. … Where governance is transparent and data are available, it is more likely that officials and leaders can be held accountable, and there is less space for malfeasance or corruption.’5fdf730cf8ce

ACTUE Colombia’s health component had the following overall objective: ‘To support the development and implementation of a transparency and integrity strategy in the health sector.’ Considering the size and complexity of the sector, the project initially focused its door-opener activities on the subsector of medicines and medical supplies.eb06438f4422 This included six main areas of action, detailed below.

Radical transparency as a game changer in the pharmaceutical subsector

A package of measures was rolled out to address opacity, irregularities, and corruption risks around prices and prescription of medicines. These included expansion of the Drug Price Thermometer (Termómetro de Precios de Medicamentos); consolidation of the Formulario Terapéutico de Medicamentos, or national drug formulary, called Medicamentos a un Clic; and development of a mobile application called Clicksalud to give citizens easy access to health system information. Additionally, a public registry of relationships between the health industry and health professionals was created under a law known as the ‘Sunshine Act a la colombiana’ or the Colombian Sunshine Act.b0601afb9f32

Integrity and transparency to improve institutional performance: The case of Colombia’s food and drug authority, Invima

Working with Invima, ACTUE Colombia supported the development of an ‘island of integrity’ strategy.afb5f1cd254f A battery of instruments and methodologies developed by other components of ACTUE were implemented in Invima under the leadership of a core group of the agency’s managers and senior staff. These measures were geared towards implementation of the access to information law, strengthening of Invima’s public accountability, and creation of a culture of integrity within the agency. In addition, technical assistance for the participatory development of the mandatory corruption risk maps and action plans paved the way for the creation of a comprehensive integrity risk management system. Under the leadership of a new Invima director, transparency and integrity became crucial means to achieve the institution’s public health objectives.

Participatory sector diagnostics as vehicles for multi-actor buy-in for reform efforts

ACTUE Colombia sought to contribute to the participatory generation of knowledge about transparency and opacity in the health sector. As a first step, the project supported the development of a policy document, the Decalogue of Transparency and Integrity for Drug Price Regulation and the Definition of Benefit Packages in Colombia.50a756d37e25 In a second step, an assessment of existing transparency/integrity initiatives pursued by public health sector entities as well as the self-regulation efforts of pharmaceutical associations was conducted in order to explore their effectiveness and gain insights on motivations, achievements, and challenges.ccf4fbc3a8d0 Finally, ACTUE Colombia agreed with MinSalud and the Health Superintendency to conduct a participatory assessment at national and subnational levels, in public and private institutions, to assess risks of corruption and opacityas well as levels of tolerance of corrupt practices in the sector. This would lay the foundation for a sector-wide transparency and integrity policy.057fb53c6119

Initiatives with civil society and the private sector

Building on its multi-stakeholder approach, ACTUE Colombia worked with health industry associations to promote compliance with norms and standards on transparency and integrity. The project also supported the creation of a self-regulatory initiative of doctors and health professionals called Médicos Sin Marca (Doctors without Brands). Development of Médicos Sin Marca Colombia drew on experience transfer from a Chilean group, Médicos Sin Marca Chile.7120c9b2e9c4

Pilots at subnational level: Connecting the dots of multiple technical guidelines

Because ACTUE Colombia aimed to link national and subnational initiatives, the project integrated a health focus into its subnational line of action aimed at piloting transparency and integrity-strengthening efforts in departmental governments. Two departmental health secretariats and the two main public hospitals in these departments received technical assistance to implement the access to information law; the Anti-Corruption Law (Law 1474 of 2011), especially its corruption risk maps and action plans; and integrity and accountability instruments provided by the DAFP.

Coordination and bridge building between health sector institutions

Finally, ACTUE Colombia played an important role inimproving coordination and building bridges between health sector institutions, in particular MinSalud and Invima, and national integrity institutions, in particular the Transparency Secretariat and the DAFP. The focus was on (a) supporting the meaningful use of normative and methodological guidance regarding implementation of the access to information and anti-corruption laws, as well as integrity and accountability instruments; (b) helping to integrate sector initiatives into broader government initiatives, such as the OGP action plans; and (c) ensuring political support for sector-level regulations (e.g., transparency and conflict of interest management in some regulatory processes).

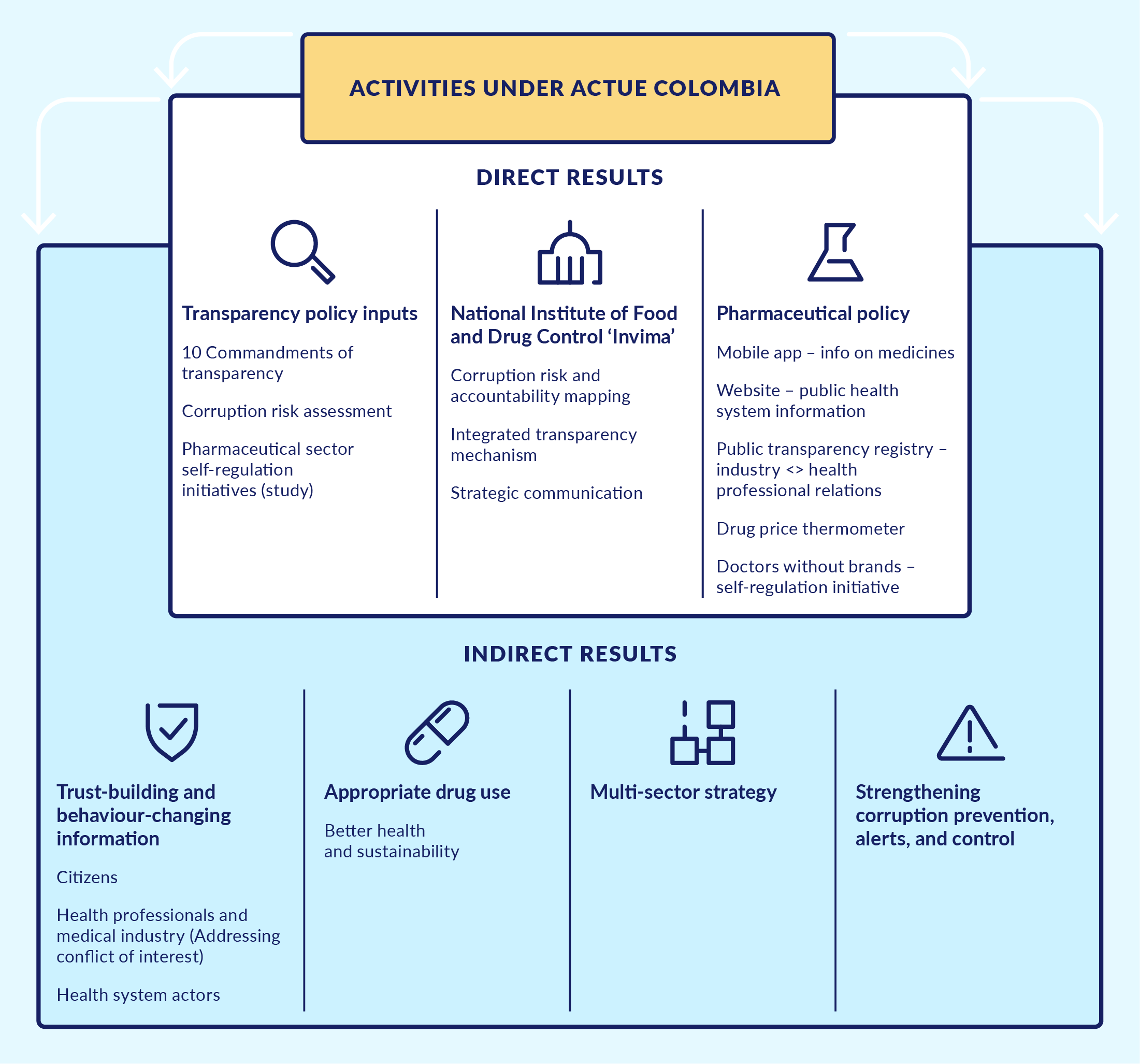

Figure 2. Direct activities and indirect results from ACTUE Colombia

Source: Author’s compilation based on internal ACTUE documents.

2.4 Programming: Strategic entry points and opportunities for mainstreaming

ACTUE Colombia supported anti-corruption mainstreaming in the health sector through a combination of (a) strategic entry points, agreed upon in the inception phase of the project; (b) prioritised actions, along with safeguards to ensure continuity during a change in national government; and (c) flexible responses to new opportunities or changing needs during the implementation phase. The strategic and consistent support was highly valued by all counterparts, as reflected in the final external evaluation of the projecta5c80b5e0562 and interviews with key stakeholders.

Since the formulation phase of the ACTUE Colombia project, the EU had taken opportunities to support the Ministry of Health in its efforts to increase transparency and integrity for better sector performance. Technical and financial support was provided to MinSalud to develop a preliminary corruption risk map in the pharmaceutical value chain. In addition, the EU-funded EUROsociAL II programme supported a series of experience exchanges between Latin American and European countries and Colombia aimed at increasing transparency in drug price regulation and the prescription of medicines. These initiatives laid the foundations for ACTUE Colombia in terms of its thematic content and partnership building.

As the implementation of ACTUE Colombia did not start until March 2014, its inception phase coincided with presidential elections in the first half of that year. There was a high degree of uncertainty about the electoral outcome and about the anti-corruption approach the new government might pursue after taking office in August 2014. In this context, ACTUE Colombia and its counterparts prioritised actions aimed at consolidating existing anti-corruption and transparency initiatives that had a prospect of medium-term sustainability. For the health sector, this meant providing support to MinSalud in three key transparency activities related to pharmaceutical policy and the rational use of medicines:

- Developing the Decalogue of Transparency and Integrity for Drug Price Regulation and the Definition of Benefit Packages in Colombia, in coordination with the IDB.

- Developing a national drug formulary, called Medicamentos a un Clic, to complement the international experience exchanges supported by EUROsociAL II.

- Scaling up an innovative instrument to increase drug price transparency, the Drug Price Thermometer.

MinSalud considered these actions as stepping-stones that any incoming government could build upon. As it turned out, the re-election of President Santos in 2014 created a positive context for sustained transparency commitments in the pharmaceutical and broader health sector. Continuity in health sector leadership was ensured through the continued tenure of Minister of Health Alejandro Gaviria, who had taken office in 2012. The pharmaceutical team of MinSalud also maintained its focus on radical transparency.

During the project implementation phase, important new opportunities emerged for ACTUE Colombia to further strengthen anti-corruption mainstreaming in the health sector. At the same time, some of the envisioned initiatives did not materialise. These changing circumstances led the project to make a number of iterative programming adaptations, always closely agreed with the Ministry of Health and the Transparency Secretariat. Several such changes are worth noting briefly.

First, responding to a request from the new director of Invima,78a4fd7304ae ACTUE Colombia agreed to support the above-mentioned institutional transparency strategy. The strategy focused on linking transparency policies and actions to the institutional mission of Invima and on holistically strengthening its open government approach, making use of a battery of instruments and methodologies developed by other project components of ACTUE.

Second, MinSalud and ACTUE Colombia initially had envisioned creating a transparency index for health sector entities, assuming that such an instrument could contribute to transformative change.4c0e6dfba3cb However, after the idea was explored in detail with other public entities, it was discarded.d466dd139ff2 Instead, ACTUE Colombia agreed with MinSalud and the Health Superintendency to carry out the above-mentioned assessment of corruption risks and tolerance levels in the health sector.

Third, patient organisations, in terms of their conflict of interest management, transparency, and accountability, had been identified as one relevant area for action. But initial meetings in 2015 did not result in a clear demand for such support. Instead, a group of key actors in the Colombian pharmaceutical sector, in particular from civil society and academia, asked ACTUE to facilitate the creation of a self-regulation initiative for the medical profession. This led to the formation of Médicos Sin Marca Colombia, inspired by similar experiences in other countries. Its aim has been to ensure the profession’s independence from the influence of pharmaceutical industry marketing incentives.

Finally, for several years a variety of actors in the Colombian health sector had undertaken a broad range of transparency initiatives, focused increasingly on the pharmaceutical subsector. Nonetheless, despite their perceived value, these efforts seemed disjointed, and little was known about their effectiveness. Therefore, in 2017 ACTUE Colombia commissioned a systematic assessment of results of the main transparency initiatives in the health sector, with an emphasis on the pharmaceutical subsector.a14c2128e89e

3. What was done? What were the results? And what happened later?

3.1. Radical transparency as a game changer in the pharmaceutical subsector

The National Pharmaceutical Policy of 2012 had identified opacity of crucial decision-making processes as a key problem in the pharmaceutical sector, one with negative effects on access to health services, financial sustainability of the sector, and trust in its institutions. Technical assistance to the Ministry of Health in these areas was an entry point for ACTUE Colombia to help mainstream transparency and integrity into the country’s health sector.

In line with the overall strategic approach of ACTUE, the supported initiatives were mutually reinforcing and brought together different actors of the health system. Thus, the Drug Price Thermometer, while having public value on its own, was a crucial input for Medicamentos a un Clic and ClicSalud. These three initiatives addressed different stakeholders, such as public sector entities, health professionals, judges, and the public at large. Similarly, the Colombian Sunshine Act, which formally regulated the relationships between the pharma industry and health professionals, was complemented by the self-regulatory initiative of health professionals known as Médicos Sin Marca. All of these initiatives featured what the Ministry of Health team called ‘radical’ transparency, that is, the publication of relevant information from all actors for transparent decision making. A strong digital component ensured that data and information would be easily available to any interested party.

The initiatives ultimately aimed to promote the rational use of medicines on the part of prescribing doctors, patients buying drugs in pharmacies, and judges deciding which medicines should be eligible for reimbursement in cases where they had not been included in the explicit health benefit package.

Regulation of drug prices and market access

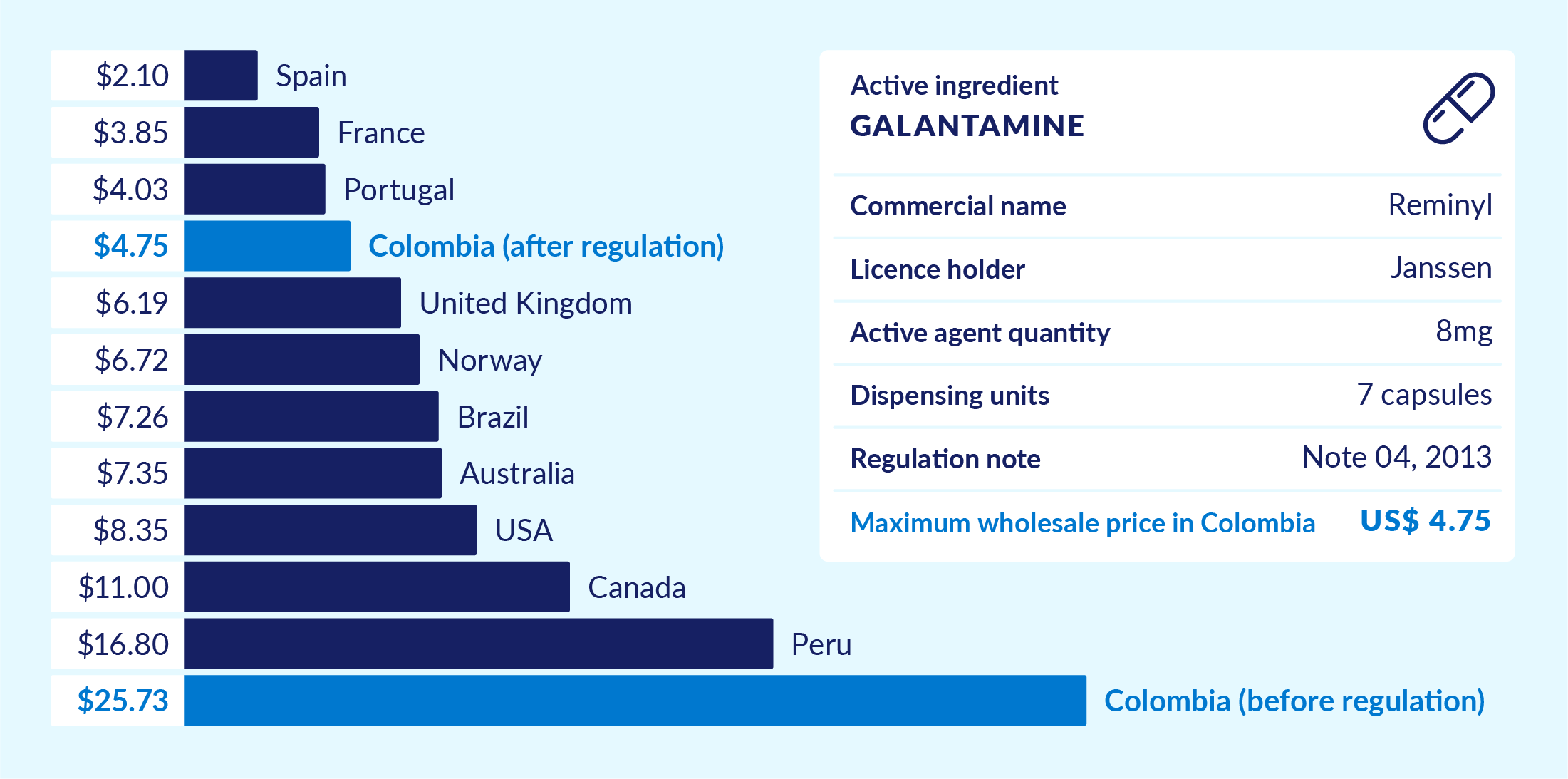

What was done? In view of comparatively high drug prices in Colombia, the government pursued the transparent regulation of drug prices as one of its first key initiatives. This relied on a methodology of either establishing international reference prices or defining maximum prices, depending on the market situation of each drug. In addition, MinSalud developed the Thermometer of Regulated Drug Prices to provide comparative price information on regulated drugs. Figure 3 shows an example of a specific drug whose price in Colombia before the regulation (red bar) was far higher than its price after the regulation (blue bar). For comparison, the grey bars indicate prices of the same drug in reference countries.

Figure 3. Drug price thermometer – price drop example after transparency regulation

This chart is for illustration only. It shows data before and right after the government approved its first National Pharmaceutical policy in 2012. Adapted from an original version by the Ministry of Health, Colombia – accessed in 2015 and no longer available online.

In addition, positions and interests of all stakeholders involved in regulatory processes, including the pharmaceutical industry and patient associations, were made public. This allowed MinSalud to regulate market access for biotechnological generics, a crucial new generation of drugs. This required the ministry to go up against the powerful interests of the international pharmaceutical industry and their lobbying efforts.4ac7faf8bdc0 In this case, the Transparency Secretariat of the Presidency played a significant role, requesting that all actors participating in the regulatory process openly declare their interests and positions. This allowed MinSalud to expose the influence of pharmaceutical companies over certain patient associations and adopt policy options that best served the public interest.

The situation six years later: Generally, the drug pricing and market regulations in Colombia set important political precedents for the financial sustainability of the country’s health system. Also, openly accessible information has influenced the behaviour of doctors and patients, allowing them to take more informed decisions.d0165f215827 However, the system is not static, and policy options to ensure the rational use of medicines require regular adjustments based on independent information and open regulatory processes.

The successor government of President Iván Duque, in office from 2018 to August 2022, continued the regulation of drug prices and the use of methodologies for a clear and transparent regulatory process. However, drug price regulation is no longer a priority, nor has it been given much public visibility in the past few years.

Overall, in view of one of the key architects of the National Pharmaceutical Policy of 2012,19449f611c77 the sustained technical, financial, and public relations support of ACTUE Colombia contributed to a relevant policy change in drug price regulation by further supporting the technical leadership and political will of the Ministry of Health. The role of the Technical Secretariat of the National Drug Price Commission was passed from the Ministry of Commerce to the Ministry of Health. The focus on creating a culture of transparency and openness also helped to build trust.

National Drug Price Thermometer

What was done? In order to provide easily accessible information on drug prices, in 2014–2015 MinSalud developed the Drug Price Thermometer.bbcdc49a864a This innovative web-based application allows citizens and health professionals to access comparative information on drug prices, thereby ensuring savings in out-of-pocket spending and conserving the overall resources of Colombia’s health system. With the support of ACTUE Colombia, the Ministry developed a mobile application for easier access and broadened the Thermometer to cover all available drugs for which reliable information has been reported to MinSalud.

Figure 4. National drug price thermometer: an interactive tool to compare prices

Source: Ministry of Health and Social Protection, Drug Price Thermometer – MinSalud website.

The Drug Price Thermometer became an integral component of the national drug formulary. The Thermometer added to the information on drugs that health professionals can consult when they decide on the best prescription formula for their patients.

The situation six years later: The Drug Price Thermometer used to be regularly updated, including by the Duque government in its first three years. However, although the Thermometer continues to be accessible through the MinSalud website, the updates have been discontinued since 2021.37e5566608d5 This may be due to the pandemic or a lack of resources, although updates are fairly easy to make, as they draw on a central drug price reporting system (SISMED) maintained by the Ministry.

In addition, in the view of one of the creators of the Drug Price Thermometer, the instrument has a weak point in that the available information reflects prices charged by drug distributors, not end-point vendors to the public, especially pharmacies. The Ministry of Health tried to work with the Ministry of Technologies to create a solution, including a geo-referencing of drug prices, but these efforts did not yield results.8a73165b3a4b Although the current Thermometer serves to illustrate and raise awareness of the large differentials in prices charged for medicines, there seems to be limited demand by intended end-users, including doctors and citizens. This in turn contributes to the lack of public demand for continuous updates.

Medicamentos a un Clic (Formulario Terapéutico de Medicamentos)

What was done? ACTUE Colombia provided technical support to the Ministry of Health to develop the web-based Formulario Terapéutico de Medicamentos, known as Medicamentos a un Clic. It provides timely, reliable, independent public information on the use, quality, contraindications, and prices of available medicines. The instrument allows health professionals to prescribe more safely, judges to make more informed decisions regarding health jurisprudence, and patients, their families, and caregivers to use medications properly. It was developed by the Institute for Health Technology Assessment (Instituto de Evaluación Tecnológica en Salud, IETS), drawing on experiences from six countries4fc2904ac43f and the World Health Organization (WHO). Additionally, close to 200 professionals, patients, and citizens from three Colombian cities provided feedback on the initial proposal to ensure adaptation to the local context.

Medicamentos a un Clic was created as part of a large government drug information system that includes other strategies such as the drug data standard and SISMED. The overall aim is to overcome problems related to the transparency of drug pricing and spending and to the use and quality of drugs.

The situation six years later: Medicamentos a un Clic is still presented on the MinSalud website as a strategy to address the ‘lack of transparency, low-quality information, and insufficient monitoring of the pharmaceutical market’ identified in the National Pharmaceutical Policy.ed857a855516 The instrument was created with the expectation that it would be fully linked with other relevant information systems, such as the drug prescription registry Mipres,b8f1ad8c596b and that it would be regularly updated. However, leadership changes in key institutions, in particular the IETS, Invima, and MinSalud, and the lack of regular budget allocations have impeded the realisation of this vision.

With hindsight it became clear that despite the great importance of transparent and independent information on the use of medical drugs, the generation of such data by trusted national institutions through transparent and participatory processes was not enough. Greater outreach to and involvement of end-users, such as prescribing doctors and specialised clinical associations (e.g., orthopaedist, gastroenterologist, oncologist, and paediatric associations, among others), is needed to foster usable instruments whose public value is widely recognised. In this sense, top-down approaches to generating relevant information need to be complemented by strong and energetic bottom-up approaches to promote use of the instruments and gather feedback on the information they provide.

ClicSalud

What was done? MinSalud and the Health Superintendency developed jointly and in coordination with the Ministry of Technologies a mobile application called ClicSalud. Its purpose was to promote transparency on crucial health sector issues, to facilitate access to public information, to inform decision making, and to promote dialogue and trust between citizens, the Ministry, and the Superintendency. This tool contained three modules designed to enable citizens (a) to understand and compare drug pricescc0316104927 as well as the quality of health insurers and health service providers; (b) to request information or lodge complaints; and (c) to obtain information on the health system, the rights and duties of citizens in the social security system, and recommendations related to public health. ACTUE Colombia supported the development of this mobile app as well as its dissemination strategy.ae569c206467

The situation six years later: At the time of writing, ClicSalud is still accessible but with reduced functions. It now mainly provides price comparisons through the Drug Price Thermometer. The information on the quality of health insurers has not been updated since 2017.

Overall, in the view of a former advisor to Minister of Health Gaviria,be58f45d381c ClicSalud did not fulfil its potential as a ‘one-stop shop’ giving citizens easy access to comprehensive information about the availability, quality, and prices of health services. Reasons include the changed priorities of the Ministry of Health, its apparent reluctance to make information easily available, challenges to institutionalised cooperation between the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Technologies, and lack of a continuous marketing strategy to promote use of the app – to name only the most important aspects. With political will and an adequate level of resources, however, the app could be revitalised and adapted to citizens’ needs.

The Colombian Sunshine Act

What was done? Interactions between the drug and medical device industry, on the one hand, and health professionals, teaching hospitals, and health-related universities, on the other, have been an area of concern in Colombia and many other countries. Payments and the transfer of valuable benefits (e.g., consulting and speaking fees, research funding, training courses, meals, gifts) from the industry to health professionals can unduly influence medical practice, education, and research. These relations can have positive results, as they can be ‘a key component in the development of new drugs and devices’.592c5f173ac6 However, they can also generate conflicts of interest or blur the lines between promotional activities and medical practice, research, or training. Studies have demonstrated that even minor financial relations lead health professionals to take biased decisions when prescribing medicines or specific health technologies.cf1a510c26eb

The Ministry of Health decided to regulate these relations to improve transparency, contribute to the management of conflicts of interest, and help to recover trust in the sector. ACTUE Colombia provided technical assistance for the development of the associated resolution and financial support for the design of a digital platform as the operational basis for a public registry, inspired by similar initiatives in the United States (Sunshine Act) and France (Bertrand Law).

The crafting and approval of the legal resolution turned out to be a long, participatory, and at times tedious process, due in part to changes in government leadership.17fa61bdf4c0 Additional factors included the many powerful interests involved as well as practical concerns about the operationalisation of the resolution. Also, design of the platform encountered a series of challenges regarding the interoperability of information systems as well as unclear institutional responsibilities to sanction non-compliance. However, pro-active, open, and creative dialogue between all actors allowed the problems to be resolved, and the Registry of Transfers of Value (Registro de Transferencias de Valor) became operational in 2019.d198554ce9db

The situation three years later: Although the industry reports regularly to the registry, the Ministry of Health of the Duque government did not make any of this information public. In addition, there has been a shift in the agenda of civil society organisations, which since 2020 have focused their already limited monitoring and advocacy work on Covid19 vaccines and other pandemic-related issues. Although academic, media, and other civil society organisations played a crucial role in bringing the Colombian Sunshine Act into being, there has been no strong push from their side to demand public dissemination of its data.

In the view of a former key official of the Ministry of Health, non-publication of industry reports not only constitutes a violation of legal requirements but also calls into question the registry’s reason for existence and its public value.c3b8d2ea8708 Without accessible data it is impossible to exercise public scrutiny of industry behaviour and its influence on prescribers, patients, and patient organisations. This situation should be corrected as soon as possible in line with the resolution and good international practice.

Health sector commitments in the Colombian OGP Action Plan

The above-mentioned health sector transparency and integrity initiatives were also integrated into the II Colombia Action Plan 2015–2017 with the Open Government Partnership.67917ba82583 The commitments included Medicamentos a un Clic, the Drug Price Thermometer, and the Colombian Sunshine Act. Transparency and the use of innovative technologies were the main strategies used to fulfil this commitment. The action plan, launched in November 2015,fc97dc9c468a served as a public window to showcase and generate traction for already existing government commitments.

3.2. Integrity to improve institutional performance and trust: The case of Invima

What was done? The ‘island of integrity’ initiative developed with Invima was probably the most coherent reflection of ACTUE Colombia’s comprehensive, multi-stakeholder, and transversal approach applied in the health sector (see Figure 5.) The leadership of a new Invima director, strongly committed to transparency and integrity as a means to improve institutional performance, offered an opportunity to gradually tie all elements of ACTUE’s approach together. The initial door-opening activities soon evolved into a full-fledged integrity strategy linking corruption risk management, transparency policies, and accountability strategies, as well as actions to detect and sanction harm done to the institutional mission of Invima and to the holistic strengthening of its open government approach.

Figure 5. Main results from 'island of integrity' approach in Invima

Source: ACTUE Final Report on Results.

The first door-opener initiative was provision of technical assistance to Invima so that the agency could turn a formal ‘tick-the-box’ compliance exercise into a meaningful corruption risk diagnostic and management tool. Thus, the mandatory Anti-Corruption and Citizen Service Plan and Corruption Risk Map,98d8885c2000 stipulated in the Colombian anti-corruption law, was developed through a process involving key staff members of Invima in different units and hierarchical positions. The resulting ‘living document’ was used by Invima’s leadership to develop a cross-cutting corruption prevention and zero-tolerance policy led by the director’s office.

The second door-opener initiative converted another formal compliance exercise into a permanently used management tool for continuous use. In Spanish, ‘la rendición de cuentas’ refers to being proactively accountable to the different constituencies of a public entity. Invima developed an innovative accountability strategy, largely based on the participatory generation and dissemination of clear and accurate public information. The agency was publicly recognised by its users (companies and citizens) for these efforts.

Thanks to the initial lessons learned, Invima’s senior leadership realised that the many formal compliance obligations regarding transparency and corruption prevention lacked coordination and a clear management purpose. Therefore, ACTUE Colombia provided technical assistance for a process at national and subnational levels to develop an ‘integrated transparency and integrity management system’. This system combined a set of preventive transparency and integrity measures with strategies for rapid response to allegations of corrupt practices, corruption network schemes, and ethical misconduct. Preventive measures included the implementation of a pilot project called ‘pathways for a culture of integrity, transparency, and the public good’.beba790ef3db A key operational aspect of this integrated system was the development of a strong internal and external communication strategy to encouraged the desired cultural change and promote preparedness to anticipate or react to alleged corruption.

What were the results? The positive results of Invima’s efforts were reflected in its good performance on the Public Entity Transparency Index of Transparencia por Colombia in 2015–2016.f17857185501

A number of lessons were learned from this experience in institutional integrity building:

- High-level leadership and support of the management team is key.

- It is necessary to go beyond formal compliance and convert integrity approaches into management tools to achieve the institutional objectives required for transformative change.

- Involving the staff in creative and open ways generates support.

- Proactive and strategic communication is essential.

- International cooperation is an essential element of strategic guidance.

These lessons learned were shared, in particular with local governments supported by ACTUE Colombia, for the purpose of inspiration and knowledge transfer.

3.3. Participatory diagnostics as vehicles for buy-in and commitment to reforms

The design of initiatives aimed at mainstreaming transparency and integrity into the health sector in general and into specific health sector institutions, actors, and processes requires a solid and broadly shared understanding of the main problems and possible solutions. ACTUE Colombia supported the development of diagnostic assessments conducted by recognised Colombian universities and civil society organisations. These participatory research initiatives provided solid proposals for policy and action.

Decalogue of Transparency and Integrity for Drug Price Regulation and the Definition of Benefit Packages in Colombia

What was done? As noted above, the first corruption and integrity risk assessment for the Colombian health sector, the Decalogue of Transparency and Integrity for Drug Price Regulation and the Definition of Benefit Packages in Colombia, was carried out in 2014.c3c09ccbf70f

The process was as follows. A panel of ten experts, representing key areas of sector knowledge, with a holistic perspective on Colombia’s health system, identified corruption and opacity risks in the two selected processes (drug price regulation and definition of benefit packages). A lead researcher and process facilitator from a prominent Colombian university conducted a document review to provide conceptual guidance. Next, semi-structured interviews were held with representatives of 14 key health actors relevant to the two processes (including the Ministry of Health, the Superintendency, Invima, health insurers, health service providers, and civil society organisations involved in health advocacy, among others). The panel of experts then discussed the findings, agreed on solutions, and synthesised them in ten recommendations of the Decalogue. The Decalogue was presented for feedback to the minister, key staff of the Ministry, and a variety of health sector entities before being publicly launched by the minister in 2015 (see Box 1).

Box 1. Decalogue of Transparency and Integrity for Drug Price Regulation and the Definition of Benefit Packages in Colombia

The Ministry of Health, with the support of the Transparency Secretariat of the Presidency, led development of the Decalogue in two key processes: (a) the regulation of drug prices, and (b) the definition of benefit packages. In both cases, the Ministry wanted to ensure processes that complied with relevant national policies and laws (the National Pharmaceutical Policy of 2012, the anti-corruption law of 2011, the Comprehensive Anti-Corruption Policy of 2013, and the access to public information law of 2014). The processes also needed to be in harmony with good international practices, especially of the OECD. Through its emphasis on transparency and integrity, the Decalogue sought to increase trust in the legitimacy of decisions made in the health system, in line with the principles of justice, equity, autonomy, and public deliberation.*

In light of this, the Ministry of Health, with the support of the Transparency Secretariat, committed to:

- Fully apply the access to public information law.

- Unify and harmonise the regulation of drug prices and benefit packages.

- Promote citizen participation and social control.

- Foster the formation of suitable human talent with high technical capacity.

- Strengthen the autonomy of medical doctors and ensure transparent relationships between the industry and health professionals.

- Take decisions based on international evidence regarding the prices and coverage of health technologies.

- Strengthen the role of Invima and the Health Superintendency in the national system of inspection, surveillance, and control.

- Promote the autonomy and technical capacity of the IETS.

- Reduce distortions that derive from the marketing of health technologies.

- Establish institutional mechanisms for the coordination and monitoring of this Decalogue.

In the Decalogue, ‘transparency’ means that public entities must publicise the tasks they perform and how they carry them out by publishing information in accessible, visible, and user-friendly formats. ‘Integrity’ means that public servants must act in an upright and fair manner so that their decisions serve the public interest rather than private interests.

Source: Decálogo de medidas prioritarias de transparencia e integridad para la regulación de precios de medicamentos y la definición del plan de beneficios en Colombia (Ministerio de Salud y Protección Social and Secretaría de Transparencia 2015).

What were the results? The inclusive and participatory process of developing the Decalogue generated buy-in from the minister and other key actors in the system. The initial purpose – to ensure continuity of a series of already existing transparency and integrity initiatives in the realm of drug price regulation and benefit package definitions – was achieved ‘naturally’, given that President Santos won a second term in office and Minister of Health Gaviria continued in his post. The Decalogue contributed to shared commitments among a variety of sector actors with rather different institutional interests and laid the foundation for the ACTUE Colombia health sector action plan.

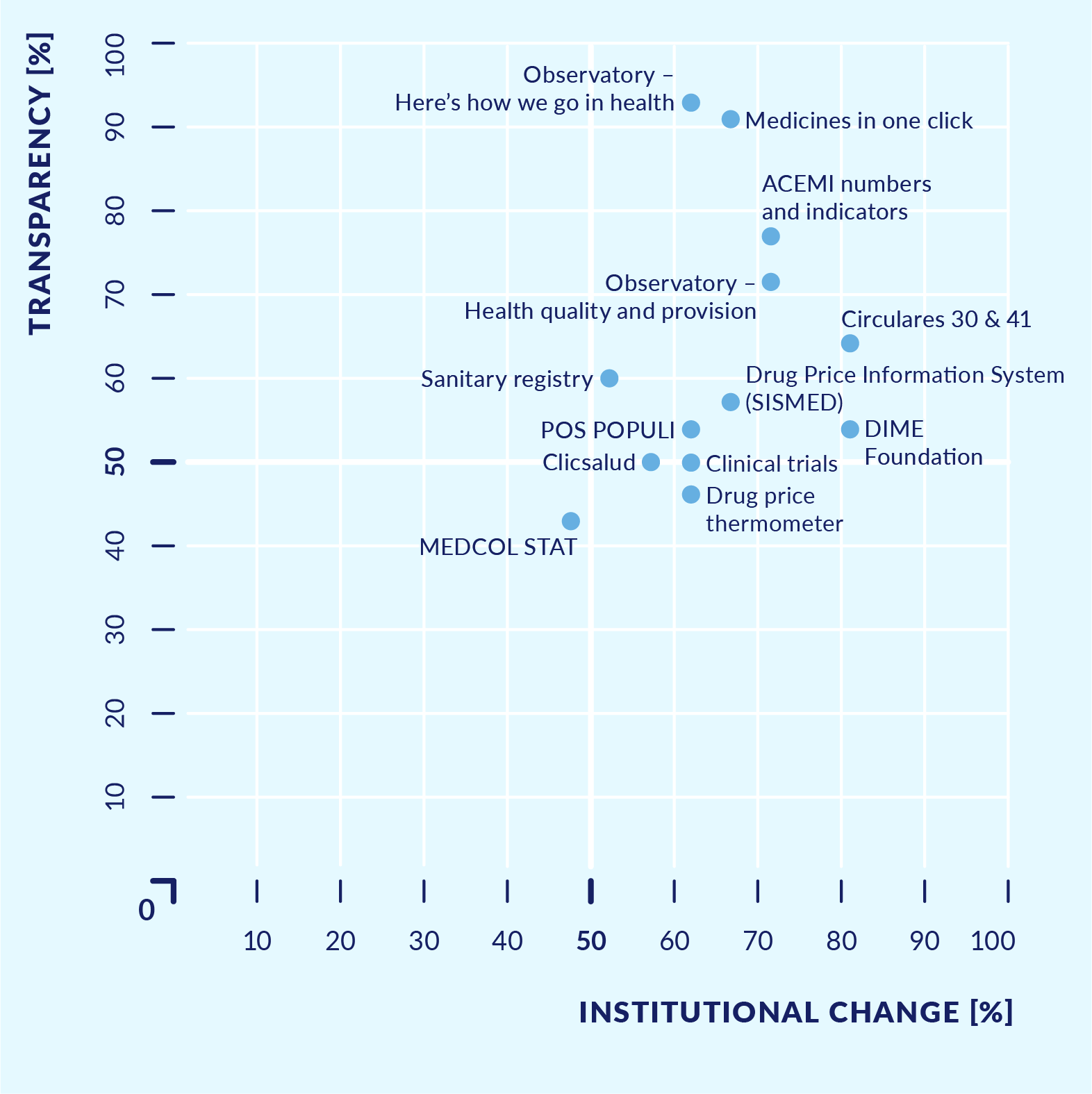

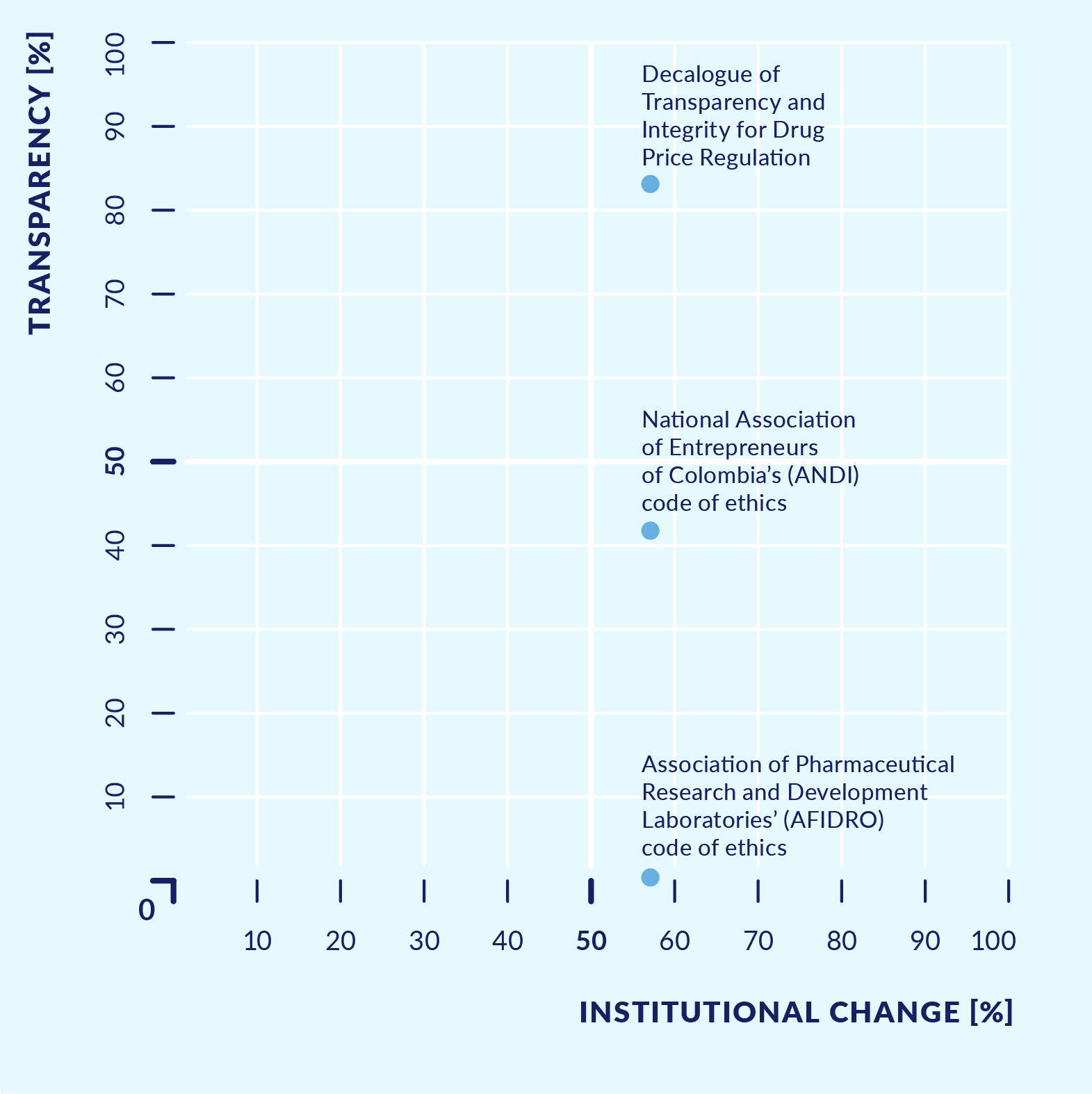

Ranking of transparency initiatives in the health sectorc998ed35e8c6

What was done? Prior to the launch of ACTUE Colombia, different actors of the Colombian health sector had undertaken a broad range of seemingly valuable but disconnected transparency initiatives. From 2010 onward these efforts focused increasingly on the pharmaceutical subsector. To address the knowledge gap, ACTUE Colombia contracted the Universidad de los Andes in 2017 to conduct a systematic assessment of the main transparency initiatives in the health sector, with emphasis on the pharmaceutical subsector.

The study evaluated 16 of the 23 initiatives identified initially.b0bf6a4a61fa Some of them aimed to strengthen the ethical commitment of certain actors, while others focused on increasing transparency in the use of resources. Most efforts were initiated by the government, but some originated in the private sector.

The initiatives were clustered into two groups to allow comparison: initiatives that visualise hard data, and initiatives that seek to establish ethical commitments related to transparency. With the results of the analysis, a ranking was developed to reflect the aggregate assessment of each initiative. In addition, a graphic illustrated the position of each initiative along two axes: (a) the level of relevance to efforts to generate institutional change in the health system, and (b) the level of transparency according to good practice. It is worth noting that an initiative can be very transparent yet have little impact, or it can be important for change in the system but not very transparent.

Figure 6. Health transparency initiatives that visualise hard data – Degree of focus on institutional change and transparency

Source A: Study of health sector transparency initiatives, 2017.

Figure 7. Ethical commitments or basic principles related to transparency and access to information

Source A: Study of health sector transparency initiatives, 2017.

What were the results? The main comparative findings were as follows. Most initiatives sought to address reputational challenges, while some focused on challenges in the management of health system resources. Most initiatives introduced new tools to make existing information publicly available rather than changing existing rules or introducing new forms of decision making. Only around half of the initiatives included participatory processes or some kind of consultation with users, and only half had clearly defined institutional responsibilities. Also, only half of the initiatives made the information regularly available to the public in a clear, user-friendly, and easy-to-navigate way. Initiatives with the greatest potential to generate an impact on the health system were also those that complied with good practice regarding transparency and access to information. In contrast, the code of ethics initiatives of the pharmaceutical industry had not yet fully clarified the mechanisms to sanction violations, nor did they provide for publication of sanctions applied.

The study identified seven main lessons learned, many of which are reconfirmed in this Practice Insight:

- Publication of information is not sufficient to achieve transparency. Many of the initiatives were developed from the ‘supply side’ perspective of the respective entity without sufficient attention to the ‘demand side’ – that is, the information needs of specialised users and the public. This limited the usefulness of the initiatives.

- The motivations behind the transparency initiatives and their purpose in relation to the health system need to be explained to interested actors and to the public at large. Otherwise, opportunities are missed to make a real impact on the system through publicly available information.

- ‘Owners’ and coordinators of the initiatives must be clearly identified. There was no policy to articulate the different government initiatives, nor was there learning from previous experiences.

- A broad vision and coordinated approach is essential. The ad hoc and disconnected transparency initiatives did not add up to a coherent effort to pursue a general culture of transparency.

- Cooperation matters. In addition to the leadership within each organisation, the main driver of the initiatives was inter-institutional support and international cooperation.

- Technical knowledge of transparency is needed to design a successful initiative. Transparency initiatives often emerged in an ad hoc way, without drawing on evidence and good practice.

- ‘Transparency for what?’ needs to be a guiding question. The cases of drug price regulation and regulation of biological medicines illustrated how the transformation of initially ‘pure’ transparency initiatives into mechanisms of procedural justice could yield results for the health system. In these cases, transparency efforts went well beyond publishing information and sought to create a space for dialogue between the government and interested stakeholders, helping them to understand and, in some cases, challenge the criteria used in decision making.

Assessment of corruption and opacity risks and levels of tolerance towards corruption in the Colombian health sector

What was done? Finally, as noted above, in 2016 the Ministry of Health in coordination with the Health Superintendency agreed with ACTUE Colombia to conduct a corruption risk assessment in the broader health sector. The top leadership of both entities was aware of the need for a prioritised, coherent, and strategic approach to a sector-wide transparency and integrity strategy.

To ensure its credibility and legitimacy, the assessment was conceived as an independent external analysis, recognising that the process was as important as the results. The Ministry and Superintendency provided strategic inputs and high-level support where needed. The assessment was awarded through an international tender to a multi-disciplinary team led by the Health Economics Group (Grupo de Economía de la Salud, GES) of the Universidad de Antioquia. ACTUE Colombia health experts collaborated at the technical and political levels.

The purpose was to assess risks of corruption and opacity, identify possible practices of corruption, and, as a new element, assess levels of tolerance towards corruption. In view of the size and complexities of the health system, the Ministry and Superintendency decided to focus the assessment on three macro-processes of resource management: (a) public health, (b) health insurance, and (c) health service provision, at both national and subnational levels, in public and private institutions.

The university team designed an innovative and tailor-made methodology for the assessment with a series of interlocking phases, each with a set of different data collection instruments. Efforts were made to ensure a participatory process involving a broad range of health actors and citizens through different instrumentsb664e6c3fab3 and at different stages. For a more detailed description of the methodology, see Annex 1.

With the results of this broad-based data collection process, two policy documents were developed and discussed with stakeholders.9a7d7bb81106 The first was an in-depth assessment of the risks of opacity and corruption as well as levels of tolerance towards corruption in the focus areas of the diagnostic.49731e4073f0 The second document presented recommendations for an integrity and transparency policy in the health sector.e160ce8662c0

A strong communication strategy was central to the process. Monthly information bulletins explained in clear, simple language the different steps of the methodology and presented intermediate findings as well as a synthesis of the final results. A series of public events at national and subnational levels discussed the findings with specialised health actors and with the broader public. Also, the research team and ACTUE Colombia participated in multiple public sector and academic events and in conferences organised by the private sector.938dcffa6112

What were the results? The immediate results of this broad process include:

- The public positioning of a set of policy recommendations which provided the basis for a health sector transparency policy and were fully embraced by the (then) Ministry of Health and Health Superintendency.

- Overall buy-in by the different health actors for the policy recommendations, given that these had been developed jointly.

- A shared understanding of corruption and opacity in the Colombian health system from different perspectives, based on a solid analysis of the risks and their underlying dynamics (drivers and enablers) in three macro-processes: public health, health insurance, and health service provision.830a17ecb05e

In the medium term, the sector assessment also made an impact on public policy in the sense that its analysis and key recommendations were taken up in the National Development Plan of the Duque government.c1108d6f6512 It also has been used as a reference for action by a variety of health actors, including the Superintendency, with a focus on strengthening its risk management and early warning mechanisms.

In the view of a leading Colombian health economist,a3329704b160 the health sector corruption assessment helped to generate buy-in for a transparency and integrity agenda with the high-level leadership of relevant public entities, industry interests, and relevant professional associations. However, the concrete implementation of the suggested transparency agenda fell victim to a new political cycle and weak institutional capacity, as the Duque government discontinued emphasis on the transparency and integrity agenda. For the most part the recommendations remained just that – recommendations – waiting to be taken up, potentially by the soon-to-come new government.

3.4. Initiatives with civil society and the private sector

In line with its multi-actor approach, ACTUE Colombia fostered civil society initiatives at the intersection of transparency/integrity and pharmaceutical policies.

ACTUE supported the creation by the medical profession of a self-regulation initiative to ensure practitioners’ independence from the influence of pharma industry marketing incentives. Called Médicos Sin Marca Colombia, it was inspired by similar efforts in several countries in Latin America, Europe, and elsewhere, and in particular by the counterpart Chilean initiative. Knowledge transfer and mentoring by Médicos Sin Marca Chile was crucial in the foundational phase of MSM Colombia. Members of the Chilean organisation shared lessons learned from their experience, advised on a strategic approach in Colombia, and participated in several dissemination events in Bogotá and other cities as well as at the formal launch in 2017.527000513389 MSM Colombia today enjoys support from the Centro de Pensamiento de Medicamentos, Información y Poder of the Universidad Nacional, the Federación Médica Colombiana, the national non-governmental organisation Ifarma, and the World Bank initiative SaluDerecho (see Box 2).

Box 2. Médicos Sin Marca Colombia

The purpose of MSM Colombia is to promote and ensure an independent clinical practice, free from conflicts of interest and from the influence of the pharmaceutical and medical device industry. This pertains especially to three key areas where the industry has shown great power to influence the decision making of medical professionals: (a) the prescription of medical drugs; (b) pharmaceutical and other health-related research; and (c) medical training.

MSM Colombia engages in awareness-raising activities and public debates at the national and subnational levels, offers university and self-learning courses, and carries out advocacy on public policy issues. With regard to the latter, MSM Colombia has played a significant role in the above-mentioned Registry of Transfers of Value between the pharmaceutical industry and health professionals. As an expert civil society group, they provided critical input into the original regulation and have been involved in the review of its implementation.

While MSM Colombia continues to engage in policy advocacy work as well as training and awareness raising, in the view of one of its founding members, it needs to reach out more proactively to prescribing doctors in order to achieve the ultimate goals of the organisation.*

* Interview with key informant, 14 February 2022.

In addition, and again in line with its multi-actor approach, ACTUE Colombia sought to build bridges with the pharma and medical device industry in the country. Towards this end, it advocated for the creation of self-regulation initiatives within the respective sectoral chambers of commerce represented in the National Business Association of Colombia (ANDI) and the inclusion of pharmaceutical companies in a private sector compliance review conducted by the national Transparency Secretariat with the support of ACTUE.f9ac47ef2979

Finally, the corruption and opacity diagnostic described above was used to bring private health actors on board for transparency and integrity initiatives. The coordination efforts were useful and the relevance to work with the private sector on concrete problems and shared solutions was demonstrated. Unfortunately, though, this happened only towards the end of the project. With hindsight, it would have been worthwhile to identify more systematically opportunities to work with private health actors beginning early in the project’s life cycle.

3.5. Pilots at subnational level

What was done? Pursuing a transversal approach, ACTUE Colombia sought to link national initiatives with the subnational level. Towards this end, the project provided, in close cooperation with its main national counterparts (the Transparency Secretariat and the DAFP), technical support to governors’ offices in three pilot departments to implement a set of mutually reinforcing integrity norms. These included the national access to public information law, the mandatory corruption risk maps and management plans, and the national norms for public accountability and civil society participation. The link with the health sector strategy consisted of including, in two of the three departments, the health secretariat of the departmental government and the main departmental public hospital. The subnational pilots were implemented over a period of 18 months. Technical assistance teams worked directly with the respective public entities to diagnose the initial state of affairs, strengthen institutional and individual capacity, and assess the results of the pilot period.09ca2099e52e

What were the results? Overall, the pilots showed that the departmental governments had not yet developed a sector approach, led by their health secretariats, to implement the above-mentioned norms. The pilots raised awareness of the need for such an approach, and first steps for implementing it were taken. However, most departmental governments did not fare too well with regard to their initial knowledge and capacity to effectively implement the integrity norms. Moreover, methodological guidance from national-level entities was confusing. The pilots with public hospitals showed that they had an institutional culture of risk management, including management of corruption risks, although it was mainly focused on formal compliance. However, hospitals had almost no knowledge or capacity to implement the access to information law, and civil society participation mechanisms had barely begun to function. In sum, the pilots showed that different types of public health entities have different needs for technical assistance. But all would benefit from a more systematic and comprehensive approach, one that pursues integrity as a means to improve institutional performance rather than aiming at formal compliance for its own sake.

4. Key success factors and challenges

The strategic and flexible support that ACTUE Colombia provided for the implementation of the National Pharmaceutical Policy between 2014 and 2018 helped the Colombian health authorities in their push for radical transparency as a game changer. These efforts were aimed at modifying institutional and personal behaviour in order to promote the rational use of medicines, with benefits for both public health and the health of the system’s finances, and to rebuild trust in the sector. Holistic support for an institutional integrity strategy centred in the food and drug agency, Invima, contributed to transformative change in corruption risk management and the creation of a culture of integrity in the agency. The sector-wide risk assessment together with the policy recommendations for transparency and integrity brought these issues to the attention of senior leadership in the health sector and provided a basis for a sector-wide transparency policy.

National health authorities under the Santos government had a clear commitment to address opacity and corruption risks in order to improve health sector performance. Their attitude differed from classical anti-corruption sector approaches, which often pursue the reduction of corruption as an end in itself. However, the successor Duque government and its lead health sector authorities did not have transparency and integrity – much less radical transparency – as a priority on their agendas.174f2e20c83b To make matters worse, civil society suffered from capacity and funding constraints and shifted much of its advocacy towards pandemic-related issues, thus lowering oversight of and demand for anti-corruption work.

In addition, and by unfortunate coincidence, ACTUE Colombia reached the end of its project term and closed at the same time that the change of government took place in mid-2018, and no successor project followed. This impeded the transfer of knowledge from the project to the new Duque government as well as continuity of technical and financial support that would have been required in order to bring many of the initiatives to fruition.

In looking at the results the project, it is possible to identify seven key factors that were important in shaping its successes and challenges.

4.1. The pharma policy as strategic entry point

The National Pharmaceutical Policy of 2012 reflected the commitment of the Colombian health authorities at that time to address a number of serious irregularities and complex corruption schemes. It continued to serve as an important reference, enabling national policy makers to identify needs for technical assistance and international development agencies to define their responses and support.

Taking a pragmatic approach, ACTUE Colombia initially provided support to help MinSalud safeguard existing transparency initiatives against the potentially different agenda of the new government that took office in 2014 (see section 3.3.1 of the Decalogue). The project worked to generate a more holistic view of the linkages between the different initiatives and to strengthen trust between health authorities and ACTUE. It also developed a strategic action plan for further support from ACTUE to the Ministry of Health for the remainder of the project time.

The comprehensive technical and political support for a series of transparency initiatives around medicines made it possible to develop and test innovative measures, to demonstrate political will through concrete actions, to launch a public discourse on transparency in the pharmaceutical sector, and to foster inter-institutional coordination, both among health institutions and between health sector and transparency/integrity institutions.

The ‘island of integrity’ initiative with Invima could be considered as a spill-over. The director of Invima had been closely involved in the radical transparency initiatives of the pharmaceutical subsector while he was serving as sub-director of IETS and later as director of medical drugs in the Ministry of Health. While this innovative effort was valuable in itself, it also served as reference for other integrity initiatives supported by ACTUE Colombia, especially the integrity pilots in health sector entities at departmental level.

The fact that ACTUE Colombia was a trusted partner of the Ministry of Health led to a second spill-over effect. The agreement to conduct the assessment of health sector corruption and opacity risks, which had not been foreseen initially, made it possible to lay the basis for a health sector transparency and integrity policy.

4.2. An integrated approach going beyond mere transparency

ACTUE Colombia sought to support mutually reinforcing integrity elements in the health sector, including proactive transparency, access to information, stakeholder participation, corruption risk management, cultural change, accountability, and the use of technology. These materialised to different degrees in the different initiatives. The results largely confirmed the underlying assumption of the approach: that all the elements need to be applied together to generate transformative and sustainable change. Transparency alone, even radical transparency, is not sufficient.

In this regard, the ‘island of integrity’ initiative with Invima was the most comprehensive. Together with a broad set of preventive measures,8acae4ca0616 it included a mechanism for rapid response to alleged wrongdoing, internal and external investigations, and sanctions, all driven by determined high-level leadership. This combination proved essential to achieve transformative results and build a culture of integrity. However, continuity of this initiative through at least one additional term of government would have been needed in order to anchor the approach in the institution’s processes and culture.

On the other hand, the initiatives with the Ministry of Health around drug prices, rational use of medicines, and relationships between the industry and health professionals were built on the premise of radical transparency and the use of information technology as a potential game changer. But they were relatively weak in terms of stakeholder participation and monitoring of results. While in a few cases the radical transparency approach was enough to achieve transformative results, the lack of consistent end-user involvement limited use of the instruments and impeded strong public demand to bring the instruments to their full potential.

Figure 8. How transparency and integrity cut across all ACTUE activities

A main lesson from the project is that all four issue areas should be part of mutually reinforcing initiatives.

Source: FIIAPP, European Union, and Colombian Government 2018.

An important element of the integrated approach was the pursuit of multi-actor initiatives. This was based on the assumption that transformative change requires the participation of all stakeholders in decision making to ensure its appropriateness and legitimacy, as well as in the implementation of rules and regulations. Many initiatives featured this approach, although in a rather sporadic way in some cases. This is likely to have limited the full potential and sustainability of the initiatives. In particular, work with civil society organisations, including organisations of patients and medical specialists, could have been given more emphasis in order to foster the demand for and use of transparency tools.

4.3. Flourishing and perishing of transparency: The role of high-level leadership

Although it may sound obvious, the leadership and political commitment of high-level health authorities was a key factor in determining the strategy’s level of success. In the initial years, under the Santos government, the leadership of health sector institutions pursued transparency and integrity in an effort to strengthen sector performance and to recover trust in the system. The pharmaceutical policy team of the Ministry of Health served as an incubator for innovative transparency initiatives focused on improving subsector outcomes and strengthening administrative processes. The technical capacity of the Ministry of Health and continuous public debates positioned the issue of health sector transparency on the public agenda. Also, the leadership of Invima played an essential role in transforming a ‘tick-the-box’ approach to corruption risk management into a meaningful management practice and in generating cultural change within the agency.

However, the Duque government, rooted in a different political coalition, pursued a different emphasis in its health policies, characterised by greater proximity to industry interests and a lack of political will for transparency. Since 2018, there has been a tendency towards opacity.94872cd563f6 In the Ministry of Health, for example, some measures of the Santos government were reversed, including the publication of formal communications between the industry and the Medical Drug Directorate in MinSalud. Other measures were curtailed, such as the Colombian Sunshine Act, or discontinued, such as the national drug formulary, Medicamentos a un Clic. The Covid-19 pandemic exacerbated the tendency towards increased opaqueness. The new leadership of Invima also abandoned its strong public and internal commitment to transparency and integrity, leading one of the radical transparency team members of the former government to resign after only a few months. Finally, actions to implement the policy recommendations of the sector assessment have been nearly non-existent.

Although a shift in priorities is normal during government transitions, the loss of high-level commitment to transparency in the Colombian health sector marked a drastic change. Moreover, it took place against the backdrop of a relatively weak public demand for transparency in health. Compounding the situation was the coincidence that ACTUE Colombia completed its project term and closed just at the time of the change in government.

4.4. Many powerful instruments without a conductor: Institutional coordination

Different units and directorates of the Ministry of Health and other health institutions created multiple transparency initiatives, with good initial results and important potential to generate change. High-level advisors to the minister of health performed partial coordination functions related to transparency, as the issue was a priority for the minister. However, there was no institutional arrangement for ministerial, let alone sector-wide, coordination, with clear responsibilities and reporting lines. With hindsight, it became clear that this was a serious weakness.

An institutional coordination function, whether exercised by an individual or a team, is crucial. It serves as the conductor of the orchestra. In the view of a former ministerial advisor, a ‘transparency tsar’, reporting directly to the minister, could have been located in the Planning Department, which is responsible for administrative policy implementation and budget allocation. Alternatively, an inter-institutional committee could have been set up to regularly review progress based on systematic monitoring reports.2b0a633a1e5f

4.5. Pitfalls of intersectoral cooperation

A distinctive feature of the health sector transparency initiatives in Colombia was that they were led and guided by the national health authorities. In various other countries, national anti-corruption authorities are the driving force that push sector-level transparency, integrity, or anti-corruption initiatives in line with their institutional mandates. They often struggle to achieve real buy-in on the part of health authorities.

On the other hand, although the Transparency Secretariat formally supported the transparency initiatives of the Ministry of Health, Invima, and other health sector entities, it did not have the institutional vision or capacity to engage actively with these initiatives. To a considerable extent, therefore, ACTUE Colombia facilitated and promoted this coordination.

The DAFP plays a crucial role in integrity policies, including policies on conflict of interest management, citizen services, accountability, and so on. While the DAFP made general efforts to disseminate guidance for implementation, ACTUE Colombia supported in-depth capacity building of health sector institutions, including the Ministry of Health and Invima. This was another opportunity for the project to contribute public value through its comprehensive multi-actor approach, but it also raises questions as to how intersectoral institutional cooperation at national level can be improved.

Given that the transparency initiatives had a strong digital component, cooperation between the Ministry of Health and the Ministry of Information Technologies was crucial. Despite the efforts made, however, key informants for this Practice Insight asserted that inter-agency coordination was not sufficiently institutionalised and depended to a significant extent on individual personalities. This limited the effectiveness and sustainability of the different transparency instruments.