Urban development and corruption: Risks and potential

Getting urbanisation right is a prerequisite for human development and environmental sustainability. Yet, corruption risks in urbanisation abound and threaten to stymie ambitions for a prosperous, inclusive, resilient urban future. Corruption in urban development is a particularly important challenge. Decisions around zoning, land management, infrastructure and service build-out offer some of the most sophisticated, inscrutable and lucrative ways for personal enrichment, crony capitalism, clientelism and political patronage.eddfc9331e9f

Developers bribe local politicians, secretly finance their campaigns, or give them ownership stakes in projects. In China, 60% of 150 listed real estate firms are politically connected to local government.32fff85df4cf These practices enable developers to gain privileged access to precious urban land. Developers also violate zoning rules and construction codes with impunity, and bypass public vetting procedures for projects that often put scarce urban land to dubious use and/or endanger critical urban ecosystems. Box 1 lists news articles exemplifying such practices.

Urban planning corruption in the press

India

How to steal a river

New York Times Magazine, March 1, 2017

“Everything is corrupt… [cascade of bribes go] to the topmost levels in the government…. when this is given, then almost anyone can be managed… this is the system.”

[real estate manager, India]

China

China property developers face setbacks in ambitious foreign push

Financial Times, May 31, 2016.

“With Chinese local governments, everything is negotiable. Developers are treated like gods”

[Asia director of top global developer]

USA

A $72-million apartment project. Top politicians. Unlikely donors

LA Times, October 30, 2016.

Kenya

Kenyan schools face land corruption battle

Corruption Watch, January 31, 2017.

Egypt

How Alexandria's 'leaning tower' became an emblem of the city's corruption

The Guardian, 26 June, 2017.

Bangladesh

Garment trade wields power in Bangladesh

New York Times, 31 January, 2017.

BGMEA gets one more year to demolish its building

Dhaka Tribune, April 2, 2018.

Germany

Ex-chief of the NRW construction company sentenced to long imprisonment (article in German) Spiegel online, February 13, 2017.

Ingolstadts Ex-OB entgeht knapp dem Gefängnis (mayor and developer helping each other out, article in German), Sueddeutsche Zeitung, 22 October, 2019.

The consequences are both immediate and long-term. Corrupted urban planning and development deprives rapidly growing cities of urgently needed resources to expand services and upgrade infrastructures. And in the long run it threatens to hardwire unjust economic, social and political relations into the fabric of cities that will be extraordinarily difficult to undo.

From narrow anti-corruption to systemic integrity

How should we protect urban development from corruption? Classic anti-corruption approaches take a rather narrow, compliance-oriented approach to deter misconduct. Yet, recently, efforts have expanded to include a broader array of interventions that are more about nurturing integrity – ‘doing the right thing’ rather than the more limited ‘avoiding the wrong thing’.468cbcedd490

Such integrity strategies typically take aim at three levels:

- Most commonly they seek to reinforce personal integrity through ethics training, invocation of social value systems and related awareness raising.

- Often this is embedded in an organisational approach to build cultures of integrity within specific organisations and administrations, emphasising tone from the top, codes of conducts and an enabling intra-organisational ethics infrastructure.2fd57b142d70

- More recently, such integrity approaches have also taken a sectoral turn as integral parts of a growing number of collective action initiatives, eg for the extractives, construction, pharmaceutical or shipping sectors.

Professional integrity: A promising fourth pillar

Another, potentially potent, source of integrity has received little attention: The professional community that a particular individual is part of and the self-image, purpose, values, ethical responsibilities this community seeks to project. Anti-corruption and broader integrity efforts have only engaged with a small band of professional communities such as medicine (and occasionally also the accounting and legal professions).

This lack of attention is unfortunate since the history and fundamental social compact that defines the relation between society and professional communities revolves around classic notions of integrity. Society entrusts professions with an important fiduciary role to exercise their skills and competencies in the best interest of their clients and society. The professions are in return granted a certain degree of autonomy and self-regulation that allows them to fulfil this role, and to further develop and promulgate the canon of related responsibilities without interference by political or other special interests.87cd8683e648 Public integrity and fiduciary duty are thus the foundational principle for professions and professional communities. This offers a unique potential for:

- Norm formation and internalisation: Professions build on some of the most intensive and extensive education and training infrastructure, from compulsory multi-year education programmes, often in specialised schools to an extensive array of continuous trainings that engage practicing professionals throughout their careers.

- Norm diffusion and collective identity: Professional networks and identities are forged through joint education, specialised repertoires of knowledge and practice, and shared professional status. At least in principle, this makes the professional peer group and networks a much stronger normative reference point, enabler for norm diffusion, and source of associational identity, than mere organisational affiliations that are bound to change every several years. A doctor is likely to feel, and be, more connected to another doctor than a colleague working in accounting at the same hospital.

- Convening and advancing thinking about ethical responsibilities: A constitutive element of what makes a profession a profession is the explicit recognition that the specialised expertise has acquired. Also important are the specific public duties and responsibilities that come with the profession’s exposed role in society. Some professions already have a strong tradition of actively cultivating and advancing related ethical duties and responsibilities, often underpinned by a normative discourse in the scholarly literature.

- Enforcement and sanctioning mechanisms: Professional bodies police the entry and quality of professional education and conduct. In principle, they have significant leverage to shape the curricula and entry requirements for the profession. And they hold powerful tools for sanctioning irresponsible behaviour through limitation, suspension or revocation of professional licences for individuals and entire firms. All these are instruments that go well beyond, and are much more far-reaching, than intra-organisational sanctions against ethical transgressions.

These characteristics of professional communities are somewhat stylised and can vary significantly across professions and country contexts. Yet, they point at the possibility of an existing self-regulatory institutional infrastructure that can potentially be leveraged to strengthen integrity.

A focus on urban planners to build urban integrity

Urban planners can play a pivotal role for the integrity of urban development. They straddle the worlds of public administrations and private developers. They command specialist expertise and occupy insider positions that make them uniquely placed to either facilitate or help guard against some of the most pervasive corruption schemes in urban development.

On the corrective side, this can range from calling out fake demand forecasts, manipulated impact assessments, or token public consultations – to probing the implications of development schemes, and to what extent they ultimately serve special interests, or can be legitimised on public interest grounds.

On the preventive side, this can include promoting the inclusivity of planning and urban development deliberations, a fiduciary regard for under-represented groups, and an active propositional role of devising development options that advance the public interest or seek to address existing inequities head on. What’s more, urban planning is – at least on paper and in principle – a professional community that offers entry points for fostering a strong sense of integrity mentioned earlier.

As a relatively young discipline, urban planning cannot quite match – neither in practice nor in self-perception – the so-called big professions of medicine or law with their elaborate institutional infrastructures developed over centuries.99cee110452c Yet urban planning and the adjacent discipline of architecture that also supplies a substantive number of urban planning professionals, in principle bear all the hallmarks of a profession.418907c552c9 These include compulsory, multi-year education and training programmes, a number of normative values related to public responsibility, and potent mechanisms to self-police through licensing and accreditation.

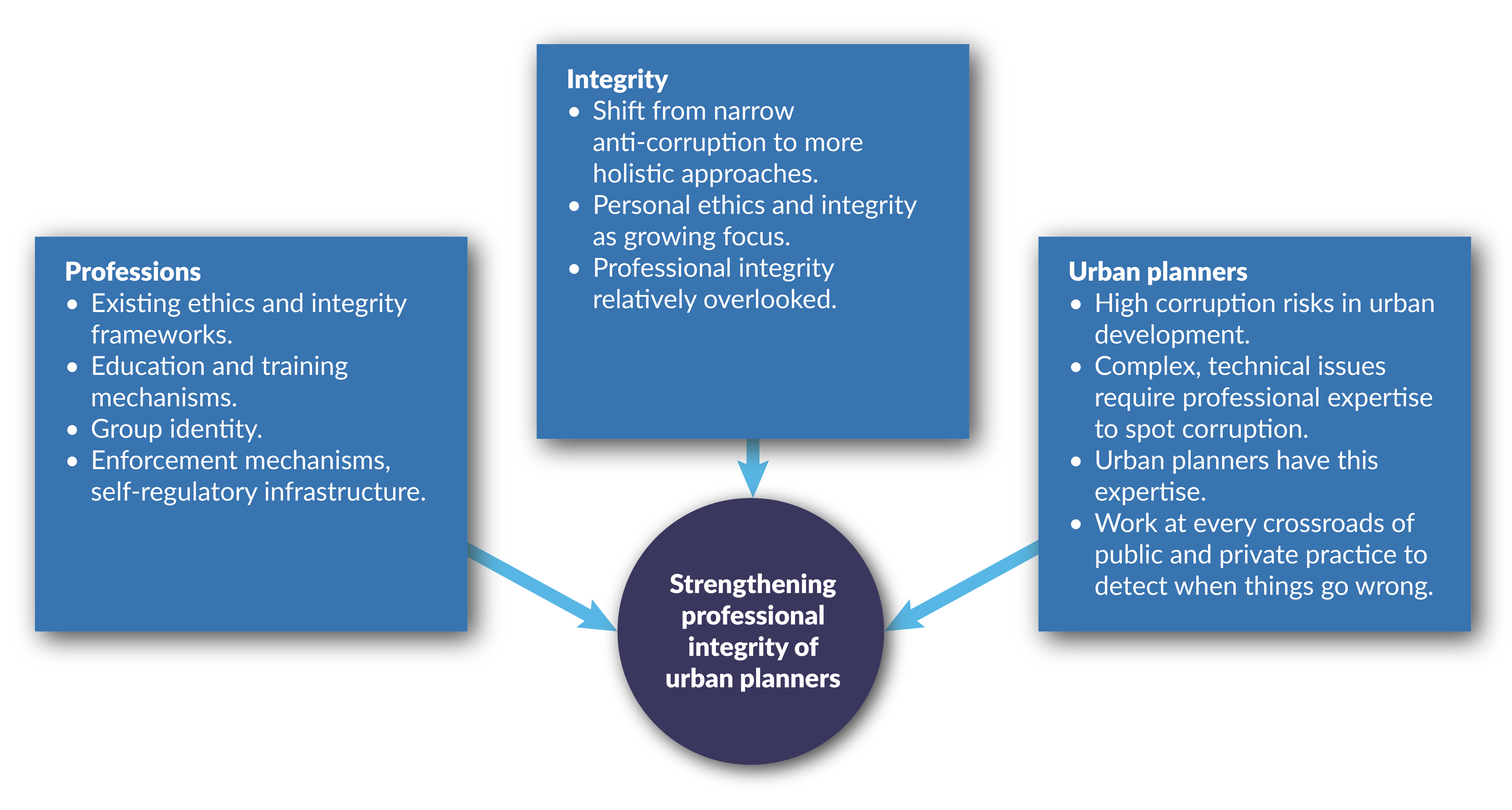

All this makes efforts to strengthen the integrity of urban planners a promising and complementary entry point for corruption-proofing urban development. Figure 1 summarises this argument.

Figure 1: Urban integrity and urban planning – a promising route

Credit: Author.

Urban planning and professional integrity in practice

A number of factors suggest that both context and timing are crucial for initiatives to foster urban planning integrity.

A greatly enabling policy context

The two most relevant policy frameworks for urbanisation and development firmly recognise the importance of urban planning. Goal 11 of the 2015 Sustainable Development Goals is exclusively dedicated to urban development. It sets out a number of commitments that accord a pivotal role for urban planning to help move cities onto sustainable, inclusive paths. It also explicitly binds countries to enhance the ‘capacity for participatory, integrated and sustainable human settlement planning’.4bc20daa8f4f

The New Urban Agenda of 2018 is the central set of global policy commitments that articulate the ambitions of the urban development community for the next twenty years. This agenda further expands on the SDG’s ambition for cities. Signatory countries pledge to promote ‘preventive anti-corruption measures,’ and improve ‘capacity for urban planning and design and the provision of training for urban planners at national, subnational and local levels.’ These binding multi-year policy frameworks lend strong legitimacy and momentum to efforts that focus on nurturing and expanding integrity in urban planning as part and parcel of sound urban governance.

A strong, rapidly growing demand for urban planning education and training

Urban planning expertise is extremely scarce in many middle- and low-income countries. As Figure 2 shows, both absolute numbers and per capita ratios of planners are low. Malawi, for example, had as of 2011, a total of 30 registered planners for more than 34 million people, while the ratio of planners to population in India or Uganda – some of the most rapidly urbanising countries– is less than a tenth of what is available in South Africa.

Figure 2: Number of registered planners in selected countries

| APA countries | Population 2011 (millions) | Number of accredited planners | Number of planners per 100 000 | Year of estimate |

| Burkina Faso | 16,970,000 | 14 | 0.08 | 2011 |

| Ghana | 24,970,000 | 150 | 0.60 | 2011 |

| Nigeria | 162,500,000 | 2,333 | 1.44 | 2011 |

| Mali | 15,840,000 | 50 | 0.32 | 2011 |

| Kenya | 41,610,000 | 194 | 0.47 | 2011 |

| Uganda | 34,510,000 | 90 | 0.26 | 2011 |

| South Africa | 50,800,000 | 1,690 | 3.33 | 2011 |

| Malawi | 15,300,000 | 30 | 0.20 | 2011 |

| Mauritius | 1,286,000 | 27 | 2.10 | 2011 |

| Tanzania | 46,200,000 | 158 | 0.34 | 2011 |

| Zambia | 13,400,000 | 60 | 0.45 | 2011 |

| Zimbabwe | 12,700,000 | 262 | 2.06 | 2011 |

| Other countries | ||||

| United Kingdom | 61,126,832 | 23,000 | 37.63 | |

| United States | 304,059,724 | 38,830 | 12.77 | 2010 |

| Australia | 18,972,350 | 4,452 | 23.47 | 2009/2010 |

| Pakistan | 173,593,383 | 755 | 0.43 | 2010 |

| India | 1,210,193,422 | 2,800 | 0.43 | 2011 |

Source: Lall et al. 2017.

All this points to high and accelerating demand for significantly expanding urban planning education and training in the decades to come.

A vibrant conversation on ethics, yet limited systematic consideration of corruption awareness and preparation

There is a vibrant and evolving conversation in urban planning research on the ethical underpinnings of, and normative principles for, the profession. Building on foundational contributions, such as Marcuse’sa0989670dfa4 critical stock-take of urban planning values in the 1970s that found extant professional norms too restrictively centred around client relationships, and oblivious to broader obligations to the public, the literature has steadily reworked and expanded its normative paradigms. Planning theory has graduated from technocratic conceptions of the rational objective expert29cf25ac430d to a recognition of planning as situated in contexts of power asymmetries and inequality.7b9340e24db5 It has taken participatory and communicative turns repositioning the planner as a process moderator, honest broker or guardian of the public or less powerful interests.cebc406666b5 Current theory increasingly sheds its Northern-centric perspective to investigate the particular responsibilities of planning and planners in the Global South.c50141f9bcc1

This normative vibrancy in theory, however, is only gradually and partially finding its way into practical planning education and training – primarily in the form of examinations of normative theories or concrete situational ethics trainings. What appears to be still under-recognised in many trainings is a critical understanding of the broader context of urban political economies, including the corruption dynamics that risk interfering with urban development.

This leads to the equally neglected question: How can the vast body of scholarship on corruption help derive practical strategies to strengthen the integrity of urban governance and the practical preparations and contributions that planners can and should make.d6473948b813,35b24a86ebf8

A small but potent empirical toolbox to track integrity cultures and values in planning

A few empirical studies have sought to examine ethical predispositions of planning students and planners. These studies have created some useful assessment methodologies that can be adopted for tracking values and related shortcomings in different urban planning communities. Howe and Kaufman,9bed0fe7257c for example, assessed the ethics and attitudes of US planners. Their methodology has formed the basis for several similar exercises in Israel, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden and Norway,b15dfc488b43 as well as follow-up work in the US that confirms the evolution and practical significance of codes in ethical decision-making of planners.9c722133fad6 More in-depth interview techniques have been deployed to gauge the self-perceptions of planners in Ireland8a380ca1f315 and a broader catalogue of survey questions to identify ethical challenges for planners in Turkey.3cf25f44e7ae

All these studies, and the methodologies they deploy, offer a starting point both for benchmarking values of integrity in other planning contexts and for devising tailored methodologies for assessing and tracking such values and norms.

Priorities for research, options for action

Where next for efforts that seek to fully realise the potential of urban planners to contribute to the integrity of urban governance? A number of worthwhile next steps can be identified.

Research: Baselines and priorities

To develop a more granular, policy-relevant understanding further research examining and tracking the values and ethical dispositions of planners in contextualised and comparative perspective is essential. What is particularly needed is a focus on countries in the Global South undergoing rapid urbanisation, where this type of research has been largely absent.

Diagnostic work on the strengths and weaknesses of particular professional integrity infrastructures, – e.g. the self-regulatory mechanisms and their enforcement of national planning associations – is a prerequisite for devising effective enhancements. How good are the codes currently in use? Are there meaningful instances of active enforcement? Where are lighthouse examples, which mechanisms need to be improved most urgently? All these are important questions to address.

Forging networks, tailoring education and a creative outlook

'Listen to people and value our opinions.' – Urban planning associations could integrate existing anti-corruption capabilities such as whistleblowing hotlines or legal defence resources into their integrity ecosystems. (Copyright: Urban Projects Bureau)

Strengthening the professional integrity system of the planning profession is first and foremost an effort to be owned by the planning community itself. Yet, there is no need to reinvent the wheel and there are opportunities to bring on board and adapt lessons, insights, and practical approaches from the anti-corruption research and policy community.

Right now, this cross-disciplinary conversation is in its infancy and could benefit from more occasions to compare notes and exchange ideas. Such conversations could, for example, translate into partnerships that connect existing anti-corruption capabilities such as whistleblowing hotlines or legal defence resources directly into the integrity ecosystems of planning associations.

Donors could play an important catalysing and convening role in this context. They can help connect the anti-corruption and urban development communities as they often cover both themes in their programming. They can facilitate peer learning and cross-country comparative work on useful institutional designs for the profession as they work across a broad range of countries. And they can help build capacity, integrate integrity issues into urban planning education, and expand related training opportunities at a time when rapid urbanisation significantly increases demand for urban planners.

Finally, with urban planning education ramping up around the world, and a fresh spirit of creative urbanism, urban justice, and data-driven cities in the air – there is a large future cohort of incoming planners that may be particularly open to reflect on and update the self-image and sense of responsibility to come with their professional identity.

An award-winning creative initiative by a band of urbanists points towards some unorthodox, yet highly inspiring ways to support this: A team from the Urban Projects Bureau travelled the world to ask people from all walks of life what they think about and expect from architects. The result – captured in portraits of the respondents who hold placards with their views – assembles into a captivating canvass of hopes and expectations for how architecture is entrusted to serve the public interest. This canvass has been exhibited at the Venice Biennale of Architecture. It could inspire similar projects to surface public expectations for urban planners and – in much more powerful ways than any conceptual exploration and inculcation could ever be – instigate a self-reflection on the identity and public responsibility of a profession so important for the integrity of urban governance.

- Zinnbauer 2017.

- Wang and Zhang 2014.

- Heywood and Rose 2015; Weaver and Treviño 1999.

- Warren et al. 2014.

- Durkheim 2013 (1957); Abbott 1988; Goode 1957; Frankel 1989.

- Glazer 1974.

- Carmon 2013.

- SDG 11.3.

- 1976.

- Beckman 1964.

- Flyvbjerg 2002; Fainstein 2010.

- Healey 1996; Forester 1999.

- eg Watson 2006 and 2014.

- Zinnbauer 2013.

- Based on an unpublished, snowballing review of urban planning curricula and ethics programmes in the context of designing an anti-corruption module for urban planners (see www.transparency.org/urbanintegrity for more information).

- 1979.

- Sager 2009.

- Lauria and Long 2017.

- Fox-Rogers 2016.

- Kilinc et al. 2012.