Query

What are the linkages between gender and illicit financial flows?

Introduction

Illicit financial flows are increasingly understood as one of the greatest challenges to global development Conservative measures estimate that illicit financial flows (IFFs) between 2006 and 2015 on average equalled roughly 20% of trade in developing countries with advanced economies (GFI 2019). The High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa estimates that Africa alone is losing more than US$50billion a year to IFFs.

IFFs weaken the financial system and economic potential of countries and divert resources that are needed to finance public services such as health, education, justice and security (OECD 2014). They are especially detrimental to developing, fragile and institutionally weak countries as they embolden those who operate outside the law, undermine governance and intensify weaknesses in the country’s institutions (OECD 2018, p. 18). Therefore, countering IFFs has become an integral concern reflected in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (Goal 16, Target 16.4).

Interestingly, while much attention is paid to gendered aspects of development overall, there are very few studies exploring the extent to which women are affected by and involved in IFFs. The scarce literature that does exist on the gendered aspects of IFFs focus on the impact of IFFs on women but do not cover the question of how women are involved in illicit financial flows.

The links between gender and IFFs can be investigated from three perspectives: i) how IFFs specifically affect women; ii) how women can help curb IFFs; and iii) the role women can play in IFFs.

Background

In recent years, the international development community has become increasingly interested in the concept of IFFs. When the term was first introduced in the 1990s, it only covered the concept of capital flight. However, it has since been used to describe a broader set of cross-border movements of capital connected to illegal activities (Kukutschka 2018). Global Financial Integrity (GFI) defines IFFs as “funds [that] are illegally earned, transferred, and/or utilised” (GFI n.d.). The transfer of capital internationally can be considered illicit for three different reasons: (World Bank 2017):

- the transfers themselves are illegal

- the funds are the results of illegal acts

- the funds are used for illegal purposes

As the following sections will show, all these also have different consequences for women.

Existing research generally agrees on three potential origins of the IFFs (FEMNET 2017)

- proceeds of commercial activities (aggressive tax planning and trade mispricing)

- revenues from criminal activities (smuggling and trafficking of drugs, people, weapons, etc.)

- public corruption: most attention in the literature is given to the outflow of profits of corruption (OECD 2014), even though these are estimated to account for only 3% to 5% of IFFs (Economic Commission for Africa 2014; Schneider 2010; Baker & Joly 2008).

In general, IFFs can also be used for further illegal activities (e.g. terrorist financing or bribery) and for legal consumption of goods (OECD 2014, p.16).

These streams are linked. Not only do they all inhibit overall political and socio-economic development they also all have gender specific outcomes, which will be discussed in the following sections (FEMNET 2017, p.9).

While there is an ongoing debate about the definition of IFFs, the definition by GIF is the one most frequently used and will be the one used for this query. For an overview of definitions see Forstater (2016) and Erskine & Eriksson (2018).

How do IFFs affect women and gender equality?

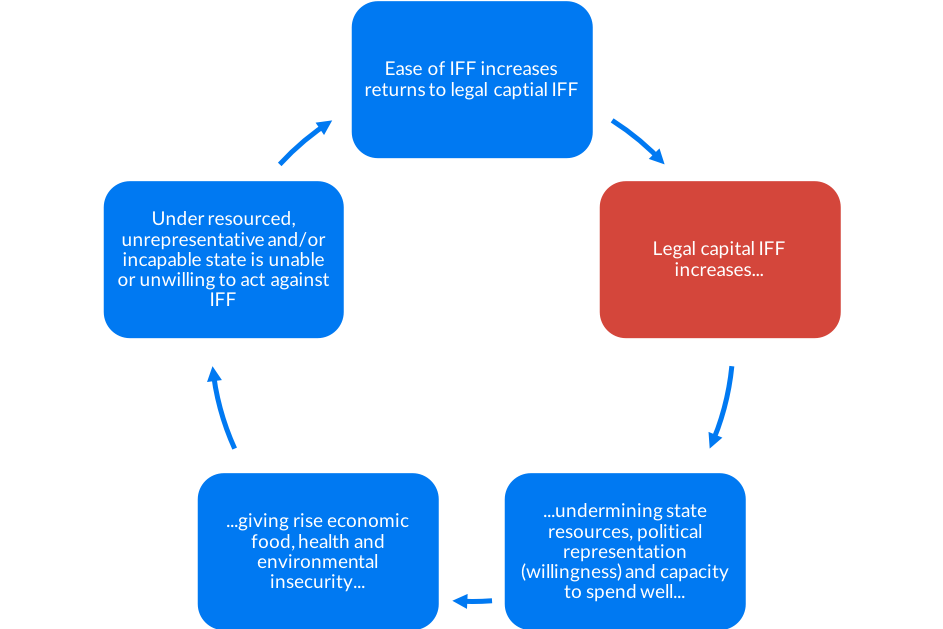

Many organisations focus on the role of illicit financial flows as an impediment to development. As IFFs are hidden and potentially come from illegal activities, the government cannot tax them, resulting in a loss in government savings, investment and consumption. Additionally, as the IFFs are typically sent abroad, they cannot be used to benefit the society where they originated (Eriksson 2017).

The loss of resources for development caused by IFFs has been linked to high levels of unemployment, poverty and inequality. IFFs lead to a lack of resources for domestic investments that spur economic growth and limit funds for investment in infrastructure and social policy. This hampers human development and the guarantee of basic human rights (Herkenrath 2014), which, as will be discussed in the following sections, has a disproportionate impact on women.

In addition, IFFs result in a lack of available resources that could be invested in fulfilling commitments to gender equality more generally (FEMNET 2017, p.9). Taxation is considered as one of the key tools to address economic inequality and gender inequality. The inability of the state to provide high quality public services perpetuates and exacerbates gender inequalities.

There are two main areas of tax evasion and avoidancethat affect women and gender equality: i) they undermine the possibility to close the financing gap for gender equality and women’s rights; ii) they have negative effects on vertical equity (those who have the ability to pay more taxes should pay more) and the progressiveness of tax systems (the tax rate increases as the income increases) that disproportionately affect women. (Grondona et al. 2016, p.2).

The following sections will discuss two elements to understand how IFFs affect women and gender equality: i) how are the effects of IFFs gendered; and ii) how are men and women differently affected by the origins of IFFs.

Gendered effects of IFFs

Lack of funding for public goods and services

Tax evasion and corruption lead to insufficient government funds, especially for public services such as education, sexual and reproductive health, maternal care and social protection, (FEMNET 2017). When allocating scarce resources, governments often choose to prioritise certain areas, like security over social services, creating a further gap in services offered (Waris 2017). This lack of government spending for public services has highly gendered effects. Women are especially dependent on these services for their survival, as the majority of the 1.5 billion people living on US$1 or less a day are women. The feminisation of poverty, i.e. the widening of the gap between men and women in the cycle of poverty in the last decade (UN Women 2000), has further increased the dependency of women on public service provision.

In many societies, cultural gender stereotypes and unequal power relations force women’s societal roles on unpaid care work. This perpetuates the poverty cycle, prevents women from participating in the formal labour market and political life.

The effect of cuts in government spending on the protection and promotion of women’s rights could also be observed in wake of the 2008 financial crisis (Alliance Sud et al. 2016). In Spain, for example, the UN Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) found in 2015 that the financial and economic crisis as well as austerity measures by the state negatively affected all spheres of life for women. They found that women faced reductions in social security and dependent care payments, unemployment, wage freezes and other negative labour market outcomes (CEDAW Comm. 2015).

Another example was the Ebola crisis in 2014/15 , where up to 75% of Ebola victims in West Africa were women. The crisis was intensified by budget shortfalls in the health services, which were exacerbated by tax abuse and illicit financial outflows (Alliance Sud et al. 2016, p.5).

Lack of funding for promoting gender equality

Institutions and programmes intended to promote gender equality and women’s empowerment receive inadequate funding when there are limits on government budgets. While an increase in budget does not always mean that these programmes get funding, they are usually the first to be cut in times of economic downturn and decreasing budgets (Alliance Sud et al. 2016).

Additionally, when the government reduces investments in public services, women are usually required to fill those gaps in caregiving, education and family support with unpaid labour (Waris 2017; Alliance Sud et al. 2016).

IFF and women’s employment

IFFs can also lead to higher rates of unemployment. As public resources leave the country, economic development is hampered, and job creation slows. Once again, in such contexts, women are more at risk of unemployment, have fewer chances to participate in the labour force and often have to accept worse working conditions, shorter working hours and lower quality jobs (Waris 2017).

Taxation and fiscal policy

Women also face an additional burden in taxation. Governments will often react with easily administered but regressive tax reforms, focusing on increased consumption taxes to make up for money lost to IFFs (FEMNET 2017). These taxes are usually levied on basic goods and services, which disproportionally affect women for several reasons. (Waris 2017). First, consumption taxes usually put an extra burden on poorer households as they spend a larger portion of their earnings on consumption(Capraro 2014). As discussed above, in the context of the feminisation of poverty, these households are often headed by women. In addition, as women are often in charge of the household, they tend to spend a larger portion of their income on goods that are affected by the higher taxes (Alliance Sud et al. 2016; Grondona et al. 2016).

Women might not only be affected by this as consumers but also as small-business owners and producers. As states need to make up for the loss of revenue, they will often increase taxes on small- and medium-sized companies, where women are overrepresented (Grondona et al. 2016). A study in Vietnam, for example, found that those sectors where more women were business owners carried higher consumption taxes than those predominantly run by men (Capraro 2014).

The gendered impact of IFFs on peace and security

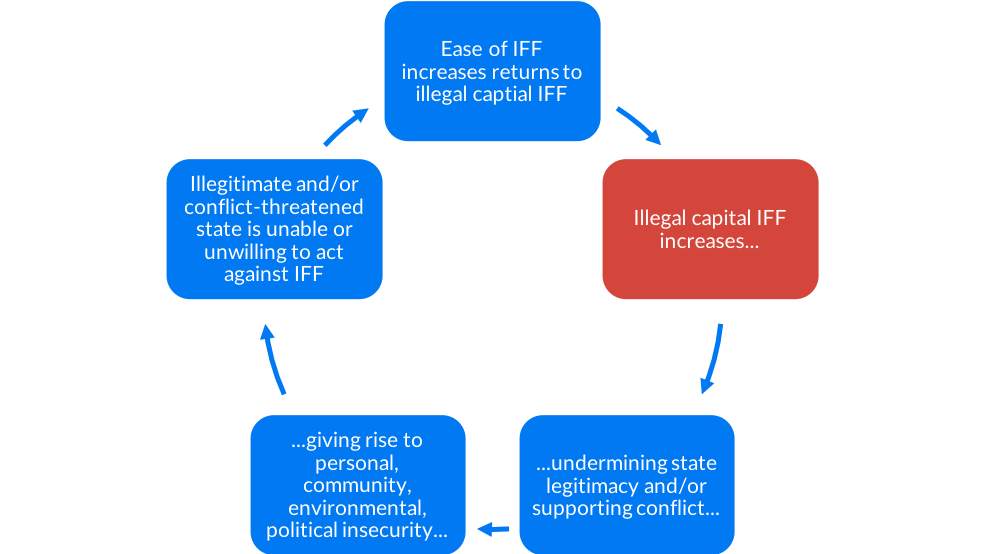

Illicit financial flows flourish in conflict and insecurity and exacerbate both (Cobham 2016). There are two vicious cycles showing how IFF is linked to insecurity. In countries with low levels of institutionalisation of authority, large amounts of money will be allocated to patronage. In such contexts, governments and their opponents are likely to resort to violence to maintain and challenge the current power structures (Cobham 2016).

Also, the illicit outflow of capital from legal operations can lead to insecurity. Where revenues are missing for goods and services that are most needed, this will damage the relationship between the citizen and the state, undermine state legitimacy and public trust in institutions, and can lead to social unrest and increased violence (Cobham 2016).

Insecurity has different effects on men and women. While men have a higher risk of death during conflict, most refugees and displaced people are women. Women also face changes in their economic roles and are more likely to face gender based and sexual violence (Strachan and Haider 2015). Across the African continent, IFFs have been linked to resource conflicts and terrorist groups (OECD 2018). The profits of illicit trade often benefit groups that are involved in conflict and act as a driver for conflict (OECD 2018)

As will be discussed later, human trafficking is also a major source of illicit financial flows. Armed conflict increases the vulnerability for human trafficking as weak rule of law and a lack of resources to react to criminal activity create a fertile ground for traffickers. The lack of access to basic necessities, such as food, shelter and clean water makes many people, including women, more vulnerable to traffickers (APA 2014; UNODC 2018a).

How men and women are affected by the origins of IFFs

To get a complete picture of the gendered effects of illicit financial flows, one also must take a look at the origins of the illegal capital and how these might have different effects for men and women. This section will discuss the effects of corruption and human trafficking as these sources of IFFS have clear gender dimensions.

Corruption

Corruption only accounts for a small part of IFFs (about 3% to 5%). Yet, corruption plays an important role in understanding IFFs. For one, IFFs are used to get the proceeds of corruption out of the country, often for money laundering purposes. Other mechanisms through which corruption and IFFs are connected include: i) corruption as a means of facilitating the generation of illicit funds, e.g. when corrupt authorities do not punish tax evasion or trafficking of women; ii) corruption can be a means to enable illicit flows, e.g. when bank officials are bribed to ignore suspicious transactions (Reed & Fontana 2011, p.19f)

It is well-established that men and women are differently affected by corruption (e.g. Boehm & Sierra 2015; Chêne, Clench & Fagan 2010; Ellis, Manuel & Blackden 2006; Hossain, Nyami Musembi & Hughes 2010; Leach, Dunne & Salvi 2014). Corruption can lead to increased inequality, lack of infrastructure and lack of service provision, which, as discussed, above affect women disproportionally.

These differences exist both in the direct and the indirect effects of corruption. A direct effect is when the individual is directly participating in the corrupt act by, for example, paying a bribe. Indirect, on the other hand, refer to the effects of a corrupt exchange on a third, non-participating party (Boehm & Sierra 2015). Direct effects of corruption are different for men and women. In absolute terms men will encounter more corruption in areas where they are more active, e.g. the business sector. However, as research has shown, women are still proportionally more vulnerable to corruption in these sectors (Boehm & Sierra 2015).

One of the main reasons that leads to men and women being differently affected by corruption are the gender roles that result from unequal power relationships within society. The roles typically associated with men or women lead to different exposures to corruption. The sectors where women are disproportionally affected by corruption, such as public services (Nyami Musembi 2007), health care (Chêne et al. 2010), and education, however are likely not the sectors where IFF originate.

Political corruption, however, which is a frequent source of IFF, can also perpetuate gender inequalities and prevent women from getting into high level positions in politics and business (Rheinbay & Chêne 2016).

Human trafficking and migrant smuggling

Trafficking in persons and migrant smuggling is an important source of IFFs. Most smuggled migrants are young men (however, this depends on the circumstances driving the mobility), yet some routes have large shares of female smuggled migrants, e.g. in South-East Asia (UNODC 2018c). Migrant smuggling has created an estimated economic return of US$ 5.5-7 billion in 2016 (UNODC 2018c).

On the other hand, worldwide, about 49% of trafficking victims are women and 23% girls (27% men and boys) (UNODC 2018a), therefore, human trafficking has a clear gendered dimension.

About 60% of trafficking in persons detected worldwide w ere foreigners, hence the UN Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC) estimates that trafficking in persons is one of the most lucrative illicit businesses worldwide (UNODC 2018b). The ILO estimates that human trafficking proceeds amount to US$150.2. billion per year (this includes trafficking for sexual and labour exploitation) (FATF-APG 2018, p.13). Terrorist organisations have also been shown to use human trafficking to fund their activities and organisations (FATF-APG 2018).

Multiple factors have been determined to underly human trafficking. Many of those who are trafficked are victims of economic policies in their countries that make maintaining a livelihood impossible. Here IFFs can be seen not only as a result of human trafficking but also as an underlying cause of human trafficking, when, as discussed above, women are disproportionally affected by a lack of government resources and seek alternative opportunities which make them vulnerable to human trafficking. Hence, poverty is one of the major underlying factors for women to fall into the hands of traffickers. At the same time trafficking traps the women into poverty (FEMNET 2017).

Other underlying reasons for women to end up as victims of human trafficking are discrimination in education and economic opportunities, conflict and displacement, unemployment and restrictive migration laws as well as cultural and religious practices, and the corruption of authorities. (Grondona et al. 2016). As previously discussed, many of these factors can be caused or exacerbated by illicit financial flows, creating a vicious cycle.

How might women participate in IFF

There is currently no research on how and if women participate in generating and facilitating IFFs to the same extent or differently than men. However, inferences can be made from what is known about differences in behaviour of women regarding corruption, tax evasion and crime. An important finding is that, while women tend to be less involved in such illicit activities, the underlying reasons are not yet known and there is little evidence that women would behave in less corrupt ways when they access economic and political spheres of power. There are also prominent cases of women engaging in all these activities.

As discussed, for measures to curb IFFs to be effective, one important requirement is successful anti-corruption policies (Erskine & Eriksson 2018). A large body of research has discussed the differences in attitudes towards corruption and the opportunities for women to be involved in corruption. Research has shown that women might be less prone to engage in corrupt behaviour.

Experimental studies have also shown a difference in attitudes towards corruption (e.g. Barnes & Beaulieu 2014; Chaudhuri 2012; Frank et al. 2011; Rivas 2013; Schulze & Frank 2003). Different potential reasons have been identified for this, such as higher risk aversion, less willingness to engage with corrupt officials or more pressure on women to adhere to existing social norms about corruption as they are more likely to be punished for corrupt behaviour (Esarey & Chirillo 2013).

Research also shows that women’s opportunities to engage in corruption are often different than those of men. Social norms and networks might be different for women, and therefore they cannot engage in corruption the same way as men (e.g. Alhassan-Alolo 2007; Bjarnegård 2013; Goetz 2007). There is also no evidence that women actually do behave differently once they are in the same power position, especially as a part of the labour force (Jha & Sarangi 2015). An example is the health sector, where many frontline workers are female nurses (Witter et al., 2017). We can extrapolate from this that health workers demanding bribes are often women. The exception seems to be the political realm, where women in parliament have repeatedly been shown to make a difference in anti-corruption efforts. However, this reasons for this are still being debated (see above).

There are, however, also high stakes corruption scandals involving prominent female politicians. Examples such as Christina Fernandez de Kircher, the former president of Argentina (Al Jazeera 2018) or the Indian politician Jayaram Jayalalith (BBC 2014). These show that women can also play a prominent role in IFFs.

There is also anecdotal evidence of how women might or might not participate in other aspects of IFFs. As discussed, women are more affected by the effects of tax evasion. At the same time, as they are overrepresented among the poor and tend to use a larger portion of their income on basic goods, so they might simply have less opportunity to participate in tax evasion.

A study of Asian and European countries also finds that while opposition to tax evasion is widespread, women in most countries are more opposed to tax evasion than men. However, they also found multiple countries with no differences and some where men are more opposed to such practices. Therefore, evidence is mixed, and this topic would require further research and discussions (Wei and McGee 2015).

Along similar lines, research also indicates that women are in general more tax compliant and honest across a large sample of countries and institutional contexts than men (D'Attoma, Volintiru & Malezieux 2018). However, whether this results in differences in the participation in IFFs is a matter for further research.

The Panama Papers also showed that while the majority of those mentioned in the papers were men, several women were also identified. The wife and daughters of the Azeri president for example have been indicated to be prominently involved in numerous offshore holdings (Fitzgibbon, Patraucic & Rey 2016). The wife of the former President of Iceland has also been linked to offshore accounts in the Panama Papers (Chittum 2016).

Numerous other grand corruption scandals have identified female involvement, especially those who are wives and / or daughter of powerful men. An infamous example is the former first lady of Zimbabwe, who has been known for her lavish lifestyle and her use of IFFs for massive spending abroad (Cobin 2017; Thornycroft 2017). The first unexplained wealth order ever issued in the UK was also issued against a woman (Drury 2019)

Crime, especially human trafficking, also are traditionally considered a male domain. Yet, human trafficking also sees an increasing number of women involved in the subjugation, recruitment, surveillance and transfer of victims (EUROPOL 2011). Importantly, women do not only perform menial support tasks but take on a wide variety of roles, especially in transnational criminal organisations. Some women have even been reported to take on total control of trafficking operations (Siegel & de Blank 2010).

The role of women in fighting IFFs

How can women help to curb IFFs

Very little research has been done on the role women can potentially play in curbing illicit financial flows. However, one can investigate what is known about the role of women in some of the aspects of IFFs, or the role of women in curbing corruption.

Over the last decades, research in different regions of the world has shown that higher levels of female participation in politics are linked to lower levels of corruption, both at the national and regional level (e.g. Dollar, Fisman & Gatti 2001; Grimes & Wängnerud 2010, 2012; Jha & Sarangi 2018; Swamy, Knack, Lee & Azfar 2001; Stockemer 2011; Wängnerud 2015). The underlying mechanisms for this relationship and the direction of the causality, however, are still being debated.

Several possible explanations have been established. For one, women in political office have been shown to bring different policy issues to the table, such as those concerning women and children (e.g. Sanbonmatsu 2017). As corruption affects women differently and often disproportionally in some areas, one can expect that female politicians to focus on anti-corruption efforts in those areas. While more research on this effect is still needed, it has been shown women’s focus on policies targeting the well-being of children and women leads to improved public service delivery and monitoring, and lower levels of corruption (Alexander & Bågenholm 2018; Jha & Sarangi 2018).

Women also are more dependent on a well-functioning state for the provision of key services and for this reason might have a different view on the destructive force of corruption within society. Therefore, they might be less likely to get involved in corruption and more likely to support the anti-corruption agenda (Wängnerud 2015).

For many aspects of corruption, a network is essential. For example, clientelism in democratic structures by definition contains a network (Stokes 2007). There is evidence that women can help to break up these often male-dominated networks (Bauhr 2018). Women often do not have access to these clientelistic networks (Bjarnegård 2013) as this corruption relies on “homosocial” capital, a type of social capital which is built on the relationships of men.

Patronage networks are frequently dominated by men and exclude women from participating (Arriola & Johnson 2014; Beck 2003; Bjarnegård 2013; Merkle, 2018). One could therefore assume that an increase in the number of women in politics could break up existing networks and therefore reduce corruption. As women have been largely excluded from power and therefore also corrupt networks, they are more likely to criticise corrupt behaviour when they see it (Branisa & Ziegler 2011; Goetz 2007; Vijayalakshmi 2008). At the same time however, it might be the case that, even with higher numbers of women, corrupt networks may continue to exist and include more women in those networks over time, once they have achieved positions of power (Esarey & Schwindt-Bayer 2019).

Research has shown that firms with female CEOs have a lower propensity for corruption (Hanousek et al. 2017). Women’s groups can also be important allies in anti-corruption efforts, and women’s engagement in good governance efforts should be fostered as this would create not only increase accountability and transparency but also promote gender equality (Hossain et al. 2010).

Conclusion

Only few studies until now have looked at how women are affected by and involved in IFFs. This overview showed that the links between gender and IFFs can be investigated from three main perspectives: i) how IFFs specifically affect women; ii) the roles women play in IFFs; and iii) how women can help curb IFFs.

The loss of state resources through IFFs disproportionally affects women, who are often more dependent on government services such as education, sexual and reproductive health initiatives, maternal care and social protection. Similarly initiatives to promote gender equality are often the first to experience budget cuts when government revenues decrease.

Men and women are also differently affected by the origins of IFFs, particularly corruption and human trafficking. While corruption only accounts for a small part of IFFs it has been well established that corruption affects women and men differently. Similarly, human trafficking, which is an important source of IFFs is highly gendered. About 49% of trafficking victims are women and about 23% girls.

Nothing has been discussed until now on how women might potentially participate in the creation of IFFs. However, the overview presented here shows that inferences can be made on what is known about differences in behavior of women and men regarding tax evasion, corruption and crime. The main finding here is that, while women tend to be less involved in such illicit activities, the underlying reasons are not yet known and there is little evidence that women would behave in less corrupt ways when they access economic and political spheres of power, which can be illustrated with some prominent examples of women being involved in such illicit activity.

Overall, the research presented in this overview shows that there seem to be important differences in how women participate in are affected by IFFs, which needs to be further researched in much more detail.