Query

What is the effectiveness of illicit-finance related conditionality in IMF and World Bank arrangements?

Introduction

In 1944, two international financial institutions (IFIs) – the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank – were established and mandated to provide loan based financial assistance or “arrangements”2a49f03d9383 to countries experiencing balance of payments difficulties and to countries for reconstruction and development projects respectively (Bretton Woods Project 2019). Both of these IFIs use “conditionality”, meaning they attach conditions to the financial assistance which the recipient country must fulfil to either first receive the financial assistance (also known as a prior action) or for continued disbursements to be made (also known as a structural benchmark) (IMF 2021a; Kenton 2023; IMF 2021a).

While these conditions mostly take the form of quantifiable macroeconomic targets that countries must meet, there are also so-called structural conditions which set out the policy requirements or reforms considered necessary by the IFIs for countries to meet such macroeconomic targets (Stubbs et al. 2020: 30). Furthermore, the IFIs’ conditions are intended to ensure that the financial assistance provided is well-utilised and, when it takes the form of a loan, that the risk of defaulting is reduced (Eichengreen and Woods 2016: 39-40).

Conditionality has proven to be a controversial topic in the literature (Stubbs et al. 2020: 30; Naffa 2017: 228), with critics arguing that it amounts to recipient countries being treated paternalistically (Kenton 2023; Azinge 2018: 201-2). This paper does not address this aspect of conditionality, but rather focuses on the aspect of effectiveness. Or as Killick (2012: 244) asks: “is [sic] conditionality actually able to exert the influence on policies that was presumed by its architects?”

Recent years have seen an increase in the use of illicit-finance related conditions, particularly on improving recipient countries’ anti-money laundering (AML) frameworks.e2669e23bbd5 While a number of studies have attempted to measure how effective conditionality is in achieving intended policy outcomes,d8d6c95fac0f this remains relatively under-researched in terms of illicit finance.

This paper sets out to review the available literature and shed light on the effectiveness of conditions in IMF and World Bank arrangements that require recipient countries to improve their AML frameworks and address illicit finance. It does this by first describing the policies of the IMF and the World Bank regarding illicit-finance conditionality and how these relate to the international standards set by the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). The following section explores the different dimensions of effectiveness and scans the available literature and data, while also highlighting inherent challenges with measuring effectiveness. This is followed by an analysis of three case studies documenting illicit-finance conditionality at work. Finally, some general conclusions are drawn.

The approaches of the IMF and the World Bank regarding illicit-finance-related conditionality

Conditionality pertaining to illicit finance is implemented by the IMF and World Bank according to different frameworks, but there are some similarities and areas of overlap.

IMF

The IMF’s work on illicit finance is guided by its AML/CFT strategy, which is reviewed by the executive board every five years (IMF n.d. a) with the most recent review having been endorsed in November 2023. AML/CFT is considered in IMF assessment processes for all members,580813833d25 regardless of whether they are a recipient of IMF funds.

For example, illicit finance is an important component of the financial sector assessment programme (FSAP) carried out jointly by the IMF and World Bank to provide an in-depth assessment of a country’s financial sector (IMF n.d. b).

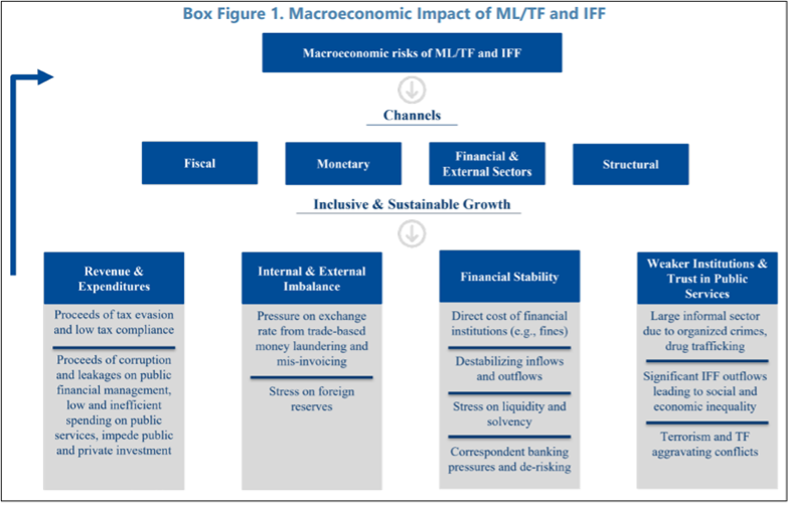

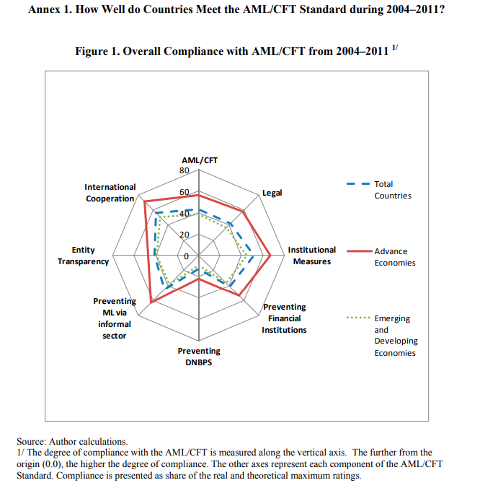

Furthermore, starting in 2012, the IMF has integrated AML/CFT factors into its more regular Article IV consultation processes, which are conducted annually with IMF members (IMF 2020b: 6). These processes aim to assess if illicit-finance related issues such as money laundering, terrorist financing and illicit financial flows (IFFs) have reached such a level to have an impact on the macroeconomic stability of a country (IMF 2020b: 6; IMF 2023d: 9) (see Figure 1).

Figure 1

Sourced from IMF 2023d: 9

This focus is also integrated into the IMF’s approach to conditionality. In its 2018 framework for enhanced fund engagement on governance, the IMF listed AML/CFT as one of the six state functions most relevant to economic activity and therefore a priority for governance focused conditionality.922758097763 Based on the above-mentioned assessments and other recipient country factors, IMF staff may choose to design and add to arrangement conditions pertaining to financial integrity and AML/CFT (IMF 2017b: 1).23e97fcf5aef According to the IMF (2023d: 2) the design of these conditions should be subject to “principles of criticality, parsimony, and avoiding cross-conditionality”.65a82c30ca21 Replicating the wording used in the IMF’s monitoring of fund arrangements (MONA) database (IMF, n.d. b), a list of examples of such conditions is given in Annex 1.

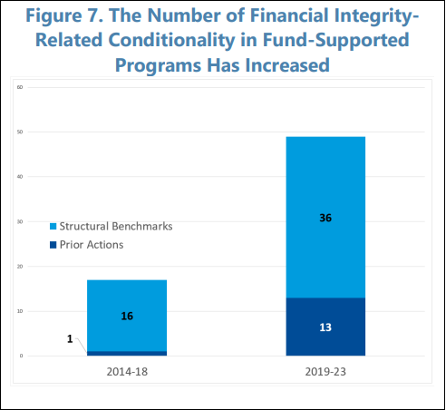

Data collected by the IMF indicates that the number of illicit finance-related conditions has grown significantly since it introduced the 2018 framework.

Figure 2

Sourced from IMF 2023d: 2

World Bank

A 2005 review of its development policy financing (DPF) led the World Bank to adopt five good practice principles to guide its application of conditionality: criticality, customisation, harmonisation, ownership, predictability and transparency (World Bank 2007). Conditions normally take the form of prior actions recipient countries must meet before receiving any funds and are designed during the country engagement process (World Bank n.d.).

Cormier and Manger (2020: 3) find that, in comparison to the IMF, there is greater variation in conditions in World Bank arrangements which focus on longer term development rather than responses to balance of payment crises. The World Bank’s framework on conditionality deals less explicitly with aspects of illicit finance – for example, the World Bank reported that, between Q4 FY2012 and Q2 FY2015, 0% of its prior actions dealt with AML/CFT (World Bank 2015) – although they do feature as conditions contained in arrangements, including more recently. Since 2005, the World Bank has maintained a database of prior actions for development policy operations which is updated annually (World Bank n.d.). The present review identified 45 illicit-finance related prior actions in the database as of January 2024, with the majority stemming from post-2016. Replicating the wording used in the World Bank’s database of prior actions, these 45 prior actions are listed in Annex 2.

In terms of coordination between the IFIs on conditionality, an IMF analysis found staff from both institutions are largely involved in the design of conditionality by their counterparts, but noted that improvements could be made in the coverage and consistency of conditionality (IMF 2004: 4, 17); however, it should be noted this analysis was published in 2004 and it does not appear an updated has been carried out since then. Killick (2012: 252) argues that in reality there is often de facto cross-conditionality between IMF and World Bank arrangements, meaning that there is a high level of similarity between their conditions.

Coordination with the Financial Action Task Force (FATF)

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF n.d.) is the global money laundering and terrorist financing watchdog and sets international standards (foremost the FATF Recommendations) to prevent these activities. It carries out assessments in the form of mutual evaluation reports of jurisdictions according to its standards. In the event the FAYTF identifies weaknesses, it may place a country on the so-called black or grey lists which identify high-risk jurisdictions subject to a call for action, and jurisdictions under increased monitoring respectively. As with failure to meet IFI conditions, being placed on these lists can have serious economic repercussions, which can stimulate countries’ fulfilment of action plans in which FATF sets out necessary policy reforms to secure a delisting (Azinge 2018: 196; Maslen 2023: 7).

Given its importance in illicit finance, cooperation between the IFIs and FATF has been extensive. IMF and World Bank staff assist FATF staff in carrying out their mutual evaluations for the lower-middle income countries that are members of FATF style regional bodies (FSRBs) (IMF 2020c: 6; Pisa 2019: 13). The World Bank has reportedly reduced its contributions to this assessment process due to resource constraints, but the IMF maintains a high level of engagement (IMF 2023c: 52).

In terms of conditionality, several authors argue that the IFIs reproduce compliance with FATF standards as conditions in arrangements, which serves to harden the application of these standards due to the potential costs incurred by failing to comply (Azinge 2018: 361; Ekwueme and Bagheri 2013: 25; Gathii 2010: 3; Levi and CGD Working Group 2015: 3; Nanyun and Nasiri 2021: 4-5). For example, if linked to IFI conditions, failure to comply with the FATF standards can also have repercussions for a country’s credit worthiness (Azinge 2018: 361).

However, the IMF, for example, has argued it does not completely reproduce the FATF standards in its conditions as this would amount to cross-conditionality (IMF 2023d: 23). Nevertheless, it acknowledges that FATF assessments “are critically important to member countries and feed into the fund’s work as staff relies on them [sic] in program conditionality” (IMF 2020c: 7). Furthermore, it makes clear that specific action items from a country’s FATF action plan can also be integrated as conditions in their arrangements with this country” (IMF 2023d: 23).

This paper finds that the IFIs do rely on compliance with the FATF standards in designing conditionality, meaning the effectiveness of illicit-finance related conditionality is, to some extent, dependent upon the effectiveness of the FATF framework.

The effectivenessof illicit-finance related conditionality in IMF and World Bank arrangements

Challenges in measuring effectiveness.

This section examines insights from the literature on the effectiveness of illicit-finance conditionality, with four caveats.

Firstly, the number and nature of conditions vary widely across arrangements; Chletsos and Sintos (2021: 3) find that the literature often fails to account for this, instead treating conditionality as if it has a “single, constant effect” on recipient countries. Therefore, even if conditionality is assessed as being effective in one case, this finding may not hold for others.

Secondly, as already alluded to, the inclusion of illicit-finance-related conditions in IMF and World Bank arrangements is a fairly recent phenomenon, meaning it can be difficult to ascertain the long-term impacts in the recipient countries (Angin et al. n.d. 3). In this vein, Eichengreen and Woods highlight that even though results in areas such as strengthening the rule of law can only be achieved over time, the IMF tends to attach conditions which it envisions can be fulfilled in 12 to 24 months as this constitutes the typical duration of its arrangements (Eichengreen and Woods 2016: 39-40).

This relates to a key third question – what constitutes effectiveness in terms of conditionality? The IFIs appear to avoid an overly narrow definition, preferring to take a more flexible approach that takes account of different trade-offs (IMF 2019:2). Lamdany (2009: 139) differentiates between effectiveness as measured when a condition is considered by the staff of the IFI to have been “met”, i.e. complied with and effectiveness as measured by the condition leading to durable reform in the policy area, something which may be more difficult to assess. This speaks to a gap often highlighted in the literature between technical compliance and effective implementation of AML/CFT frameworks (Nanyun and Nasiri 2021: 8) which is discussed more below.

Finally, a fourth point is the issue of attribution when measuring impact. Even where observed progress in countering illicit finance in a recipient country coincides with related conditions in IMF or World Bank arrangements, it can be difficult to causally attribute this shift to these conditions. There may be other domestic political factors driving the same progress, not to mention pressure for reform from other external sources, for example, the European Union or influential lobby groups.

IMF and World Bank data

Both IFIs collect data on the conditions they attach to arrangements and carry out periodic reviews of their conditionality frameworks with an eye to assessing effectiveness, although the IMF arguably does so more extensively.

The IMF maintains MONA database, which contains comparable information as far back as 2002 on arrangements and their conditions (IMF n.d. b). It contains information on illicit-finance-related conditions, including describing whether they were met by recipient countries or remain outstanding, as well as at which point in the assessment process they were met.

However, weaknesses in the database have been cited by scholars. Angin et al. (n.d.: 12) found the IMF’s categorisation of anti-corruption conditions in MONA suffers from many inconsistencies and missing data, leading to an undercounting of conditions. Rickard and Caraway (2019: 43) argue it cannot easily be used for data analysis on an aggregate level. Indeed, illicit-finance-related conditions are primarily split across two codes: 11.4. anti-corruption legislation/policy and 6.1. financial sector legal reforms, regulation and supervision (IMF, n.d. b). However, both of these codes are also used for conditions which are not directly related to illicit finance, for example currency-induced credit risks. Disaggregation into more specific sub-categories of illicit-finance-related measures is also not provided for, although this would be desirable to assess and compare the effectiveness of measures.

Furthermore, each entry in the MONA database does not reflect one condition, but a change in the status of implementation of a condition. As of 8 March 2024, there were 1,633 such entries under the 11.4. code and 16,399 under the 6.1. code, but as these include duplications of conditions, it is difficult to calculate the total number of illicit finance-related conditions and the percentage of these complied with.

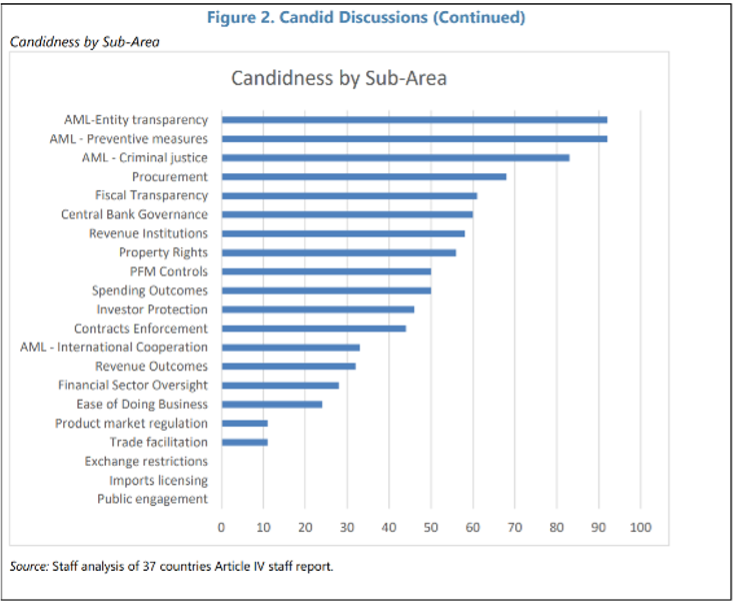

The IMF itself appears to rely on a combination of the MONA database with staff estimates to determine aggregate compliance rates for conditions. In its review of the 2018 framework, it found that AML issues are the most common topics featuring in “candid discussions” between IMF staff and recipient country stakeholders as part of Article IV consultations (see Figure 3). Indeed, such discussions were more likely to take place with lower-middle-income countries than with advanced economies (IMF 2023b: 95).

Figure 3

Sourced from IMF 2023a:100

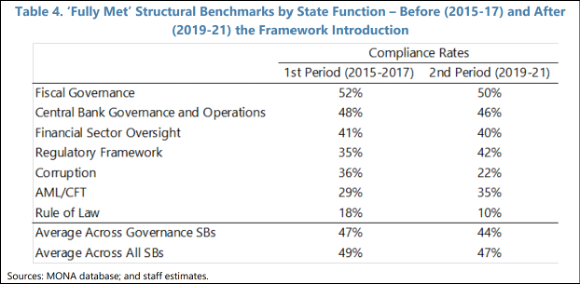

However, their review also measured the estimated compliance rate for AML/CFT structural benchmarks, finding it was below the average compliance rate for all governance-related structural benchmarks, although the rate had improved between 2019 and 2021 in comparison to 2015-17 (see Figure 4).

Figure 4

Sourced from IMF 2023a:100

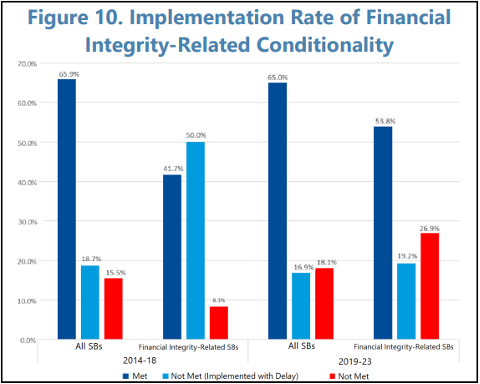

More recent data analysed by the IMF in its review of the fund’s anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism strategy (IMF 2023d: 24) adds further nuance to this picture. It instead considers so-called financial integrity structural benchmarks, which appears to be a broader set than the AML/CFT structural benchmarks. The review found that the percentage of benchmarks both met and not met increased from 2019 to 2023 in comparison to the period from 2014 to 2018, but the number of conditions implemented with delay had fallen (see Figure 5).

Figure 5

Sourced from IMF 2023d: 24

The IMF also considered the overlap between its arrangements and the FATF assessment process. While noting in line with the principle of cross-conditionality that “the FATF’s decision to include on or exit a member country from its list cannot be made a condition in a fund-supported program”, it highlighted the significant role it plays in helping countries exiting the FATF lists (IMF 2023d: 23). It found that, between 2010 and 2023, 44% of the 78 countries that have been included in the FATF grey list were also part of an IMF arrangement in a fund supported programme at the time of the listing and that almost 90% of the FATF listed countries “took at least five years to demonstrate effectiveness to be able to exit the list” (IMF 2023d: 22).

In terms of the World Bank, database of prior actions does not provide data on how many of the 45 illicit-finance related conditions listed in the database of prior actions were met.

However, in its 2021 review of DPF, the World Bank (2021: 34), relying on its teams’ self-assessment, found that for a total of 916 prior actions attached to arrangements between Q3 FY2015 and Q3 FY2020, “76 percent achieved at least partial results, while 24 percent did not achieve results or did not have observable results”.

While inconsistencies and gaps in how the IMF and World Bank classify and measure illicit-finance conditions make assessment difficult, it appears that a majority of conditions are at least partially met.

The following subsections consider some of the wider dimensions of effectiveness as discussed in the literature.

Technical compliance versus effective implementation

A criticism that has been levelled at conditionality is that it prioritises technical compliance with AML standards over the effective implementation of these standards (Naffa 2017: 229). While not always clearly defined, technical compliance is generally used to describe formally meeting a requirement without the need to have effectively implemented it. Therefore, the actual effectiveness of conditions which only require technical compliance cannot be assumed.

In a sense, IFI conditions may necessarily lean towards technical compliance rather than effective implementation because they need to be fulfilled in the short term, i.e. within the duration of the arrangement.

In a survey of IMF staff members (IMF 2023c: 63), some country teams reportedly expressed concern that the IMF’s coverage of AML/CFT was superficial and over-reliant on FATF and FSRB assessments. Indeed, FATF has also been criticised for an excessive focus on technical compliance in its standards (Chêne 2017: 3; Durner & Cotter 2018: 3). It appears that at least 43 conditions listed in the MONA database make direct reference to compliance with the FATF standards.50978299d3c9

Due to data limitations, it is difficult to accurately assess the extent to which IFI conditions do focus on technical compliance over effective implementation. While they should not be treated as representative of all IMF illicit finance-related conditions, the examples listed in Annex 1 indicate a mixed picture. Many of the conditions appear to call for a legal or policy shift, such as passing of bills and adoptions of law, whose implementation can be assessed in technical terms, but appears less amenable to being assessed for effectivness over a longer period of time. For example, a condition was attached to an arrangement with Albania to “develop and discuss with IMF staff an Action Plan for implementing the recommendations of the Financial Sector Stability Assessment Report.” However, there are some examples of conditions that align more with effective implementation; for example, a condition was attached to an arrangement with Uganda regarding the “development and implementation of tools for risk-based AML/CFT supervision of the financial sector.” These examples also demonstrate a variety in levels of specificity, with some conditions appearing quite vague in wording; for example, a condition was attached to an arrangement with Antigua and Barbuda to “amend legislation to effectively combat money laundering and financing terrorism.” Some of the examples of World Bank prior actions listed in Annex 2 are indicative of an effective implementation approach. For example, the following prior action was attached to an arrangement with Honduras: “The Know Your Customer (KYC) policy has been implemented in all the banks, finance companies and savings and loans institutions subject to CNBS supervision.” However, the majority of prior actions featured on this list lean towards technical compliance. For example, the following prior action was attached to an arrangement with Morocco: “adoption by the Council of Government of a draft law on the fight against money laundering.”

There is evidence that the IMF is attentive to the inadequacies of technical compliance, stating assessments based on AML/CFT frameworks and conditions should “focus not only on the adequacy of the legal framework but also on the overall institutional capacity and effective implementation” (IMF 2017b: 15). For example, it commits to assessing elements of AML/CFT that are more related to implementation, such as the investigation and prosecution of offenders and the number of suspicious transaction reports filed (IMF 2017b: 30).

Similarly, FATF (2023) has responded to such criticism and ensured its assessment methodology focuses on both effectiveness and technical compliance. However, in a 2022 review it found that while it continued to record countries’ significant improvement in technical compliance with the FATF’s 40 Recommendations, “many countries still face substantial challenges in taking effective action commensurate to the risks they face”.

Political will

As alluded to, this paper does not engage with the debate around whether or not conditionality is paternalistic insofar as it does not touch on effectiveness. However, certain voices in the literature argue that the way in which conditions are designed by the IFIs can lead to a lack of political will or “ownership” of the conditions by the recipient country, disincentivising their effective implementation (Eichengreen and Woods 2016 :42; Dreher 2002: 7).

In relation to the FATF standards, Azinge-Egbiri (2022: 16-17) finds that if rulers in recipient countries are “coerced” into compliance and are unable to participate in the standard-setting process, they may not consider these standards to be legitimate and thus may engage in “sham compliance”, where they attempt to convince assessors that they have met the standards even in the absence of meaningful reform.

Political will can also be absent when there is a poor level of popular support for the IFIs. For example, Breen and Gillanders (2015) find negative public perceptions of IMF and World Bank effectiveness in countries with low levels of political trust and high levels of corruption.

However, the IMF (2023d: 24) recognises this and found that “although financial integrity conditionality is generally met, lack of political will coupled with capacity constraints generally underscore the challenge of timely implementation of related structural reforms” (IMF 2023d: 24).

The IMF (2021b: 28) cites the positive example of its illicit-finance related conditions attached to a 2016 arrangement with Madagascar. The World Bank also supported Madagascar with technical assistance on AML/CFT reforms at this time (World Bank Group Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions 2017: 22). Madagascar met several conditions, including by enacting a law on AML/CFT at the end of 2018. They noted that this was an achievement considering the arrangement took place against a political transition and elections. However, the IMF stated that “successful implementation of governance reforms requires the authorities to be fully committed and to cooperate closely with the fund”. This indicates the IMF understands the difficulty of securing effective implementation in the absence of political will.

Sensitisation to local factors

This touches on another point some authors have raised, namely that the conditions the IFIs design may be overly general and not sensitive to the local context, thus undermining their effectiveness (Azinge-Egbiri 2022: 17).

For example, lower-middle income countries that face capacity constraints may be less able to effectively implement conditions. While the IMF commits to observing the principle of parsimony, Reinsberg et al. (2022) found non-compliance with IMF conditions can often be explained by over-ambitious programmes that do not take due consideration of local circumstances. In a 2021 paper, the IMF recognised that capacity restraints can hinder the implementation of conditions, making it important to align conditionality with technical assistance efforts (IMF 2021b: 20-21).

For example, with respect to the IMF’s condition for its arrangement with Lebanon that the government establish anti-corruption and anti-money laundering frameworks, Gharib et al. (2023: 18) found the policy sequencing did not account for political interference in the judiciary; instead, they argue the IMF should have inserted a prior condition for a draft law ensuring the independence of the administrative courts.

Similar criticism has been levelled at the FATF standards which Gathii (2010: 17) argues the IMF promotes as “universally applicable – to all countries whether they are members or not”. Again, the IMF seems to be conscious of such criticism. A 2011 paper published by the IMF (Verdugo Yepes 2011: 6, 10) studied 161 countries assessed by the FATF since the revision of its assessment methodology in 2004, finding that “compliance is correlated with the countries’ economic development reflecting a designed weakness in the AML/CFT standard and the assessment of countries’ compliance with it” and argues for adjustments to the assessment methodology to be address this imbalance (see Table 6).

Figure 6

Sourced from Verdugo Yepes 2011: 32.

Offsetting this critique, certain studies have found that both the IMF and World Bank have used their membership within the FATF to advocate on behalf of developing states (Blazejewski 2008: 54-55; Nance 2017: 142). For example, prior to 2008, FATF non-members were assessed according to stricter standards in the form of the 25 non-cooperative countries and territories (NCCT) criteria as opposed to FATF members who were assessed against the 40 FATF Recommendations; the IMF and World Bank both pushed for a harmonised assessment process (Blazejewski 2008: 56) Indeed, Gathi (2010: 10) argues that some developing countries have even sought to move the monitoring of FATF Recommendations from the FATF to the IMF as they perceive they have more prospect of even-handed negotiation with the latter.

Narrow scope

Another argument is that IFI illicit-finance related conditions may focus too narrowly on aspects of AML/CFT and fail to effectively counter other characteristics of illicit financial flows, such as financial secrecy (Meinzer 2023), which may feature less in the FATF standards. As such, and considering that IFI conditionality applies primarily to low and middle-income countries, the effectiveness of illicit-finance related conditions in addressing the role of higher-income external jurisdictions that enable cross-border IFFs may be comparatively limited.

However, the IFIs seem to be expanding how they treat illicit finance. Meinzer (2023) of the Tax Justice Network praised the IMF’s recent approach of incorporating large financial centres into its determination of illicit finance risks. Indeed, the IMF has started carrying out offshore financial centre assessments in addition to its FSAP (IMF 2020c: 6). Furthermore, it has introduced voluntary assessments for members to assess transnational AML/CFT risks affecting them (IMF 2023a: 35).

Furthermore, a report published by the IMF (Verdugo Yepes 2011: 25) found that the FATF standards should incorporate more comprehensively the underlying risks of ML/CFT, such as international finance and trade. Furthermore, a 2021 World Bank report called on the FATF to take more effort to reflect financial inclusion in its assessment, holding financial inclusion as necessary to the effectiveness of AML/CFT measures (Celik 2021: 7, 9).

Impact of other conditions

As mentioned above, the majority of conditions attached to IMF and World Bank arrangements concern macroeconomic factors or other structural policy areas relevant to the economy. Therefore, illicit-finance conditions, if present, are typically attached in with another wide set of conditions.

Several authors have carried out studies indicating that some of these conditions can actually create further illicit-finance vulnerabilities in the recipient countries. A frequently cited example is that conditions calling for the deregulation of the banking sector can create new avenues for money laundering (Zúñiga 2018: 6).

Chletsos and Sintos (2021) investigated the effect of IMF intervention on the size of the informal or shadow economy, relying on a panel of 141 countries from 1991 to 2014. They analysed both basic participation in IMF arrangements and the presence of conditionality, finding that both led to an increase in the size of the informal economy in recipient countries. A large informal economy can generate assorted illicit-finance vulnerabilities.

Similarly, using a novel data set of 180 countries between 2000 and 2018, Nosrati et al. (2023: 14) found that IMF conditionalities designed to curb money laundering and related financial flows did reduce estimated levels of capital flight, but this effect was offset by other IMF conditionalities (for example, pertaining to privatisation), leading to an aggregate increase in capital flight, another potential indicator of illicit-finance vulnerability.

Finally, Ataman (2022) tested the impact of IMF conditionality on corruption levels (as measured by the V-Dem measure) of 131 countries between 2000 and 2014, finding that there was no statistically significant impact.2d8527112d77

These studies call into question whether the effectiveness of illicit-finance conditions can be disentangled from the IFI’s wider conditionality policies, which can also impact illicit finance despite not being necessarily designed to.

Case studies

In the absence of comprehensive data, another approach to assessing the effectiveness of illicit-finance related conditionality is a deeper analysis of cases. This section presents three empirical cases but cautions against treating the findings as representative of a much wider and varied set of conditions and arrangements.

IMF beneficial ownership conditions

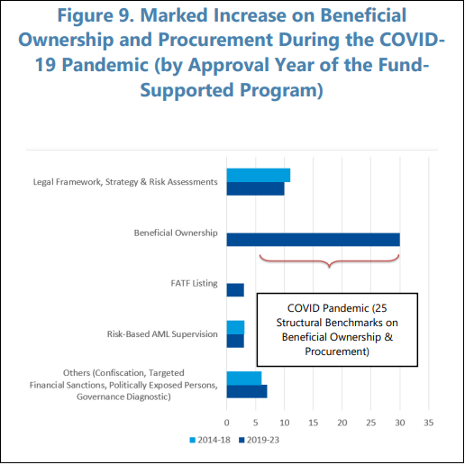

Both the IMF and World Bank entered arrangements with many countries during the COVID-19 pandemic to support them in procuring medical equipment and against the general macroeconomic consequences of the pandemic (Open Contracting Partnership and Open Ownership 2021: 5).

Partially with the aim of countering risks pertaining to medical procurement fraud and money laundering, the IMF stepped up its inclusion of conditionality or commitments related to procurement transparency and beneficial ownership information in these arrangements (IMF 2023d: 23; Knobel 2023). It found that these conditions appear to have had a significant positive impact during the pandemic and were implemented by most recipient countries (see Figure 7).

Figure 7

Sourced from IMF 2023d: 23

A report from Open Contracting Partnership and Open Ownership (2021) aimed to assess the impact of these conditions. It also found that most governments made progress in complying with the conditions in establishing transparency and beneficial ownership systems, thus meeting the broad spirit of the IMF commitments (Open Contracting Partnership and Open Ownership 2021: 4). However, it found that when it came to publishing data on the beneficial owners of emergency suppliers in these systems, this was low in quality and quantity. In this sense, they argued that the conditions could have been more specific and ambitious.

For example, it found that the government of Afghanistan metbeneficial ownership conditions by issuing a circular in September 2020 mandating that bidders submit information about their beneficial owners (Open Contracting Partnership and Open Ownership 2021: 10). However, the report found poor implementation in practice as none of the buying agencies studied were using the downloadable form the government offered but instead were uploading PDF scans of paper which can be prone to errors.

The report also raised the question of attribution as many respondents felt that governments’ decisions to introduce measures were not always a direct consequence of the IMF commitments, but this often followed from other factors such as leadership from domestic actors and existing ongoing reforms in this policy area, as well as sustained advocacy by other actors such as civil society (Open Contracting Partnership and Open Ownership 2021: 8).

There is also evidence that conditions were not always sensitive to local capacity needs and accompanied by sufficient funding to ensure effective implementation. For example, in response to IMF conditions, the Kyrgyz Republic amended its procurement law, establishing a portal on which buyers would be mandated to publish information on suppliers’ beneficial owners (Open Contracting Partnership and Open Ownership 2021: 10). However, apparently the government did not provide a sufficient budget to hire new staff or web developers to operate this portal (Open Contracting Partnership and Open Ownership 2021: 12).

Pakistan

Pakistan has been party to arrangements with the IMF regularly since 1982 to address balance of payment issues (Uddin 2022: 85). In 2019, both entered an arrangement valued up to US$6 billion to be dispersed in tranches based on the fulfilment of conditions (Uddin 2022: 85).

The FATF first put Pakistan on its grey list from 2012–2015, and then relisted it in June 2018 due to identified deficiencies in its AML/CFT framework (Basel Institute on Governance 2022: 2). Following Article IV consultations, the IMF then made addressing deficiencies in AML/CFT a condition of its ongoing arrangement with Pakistan (Uddin 2022: 90; Basel Institute on Governance 2022: 2).

The IMF cited Pakistan as a positive example of conditionality in its review of the fund’s anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism strategy. The IMF (2023d: 22) argued that, when the arrangement was first concluded, Pakistan had shown little progress in addressing its 27-item action plan agreed with the FATF, but Pakistan then improved its performance supported by conditionality, and exited the grey list in October 2022.

At the time, Pakistan was heavily reliant on international financial assistance, so there is good cause to stake conditionality’s role in the exit (Maslen 2023: 11). Furthermore, Sultan et al. (2022: 4) find evidence that an IMF condition was the principal motivation for the government including tax evasion as a predicate offence in its AML legislation.

The Basel Institute on Governance (2022: 2) summarises that, between September 2020 and August 2022, Pakistan was subjected to four follow-up reports and improved its performance in technical compliance from 41% to 72% and no longer received the “non-compliant” evaluation for any of the 40 FATF Recommendations. However, it notes that performance under the FATF’s effectiveness criteria or “immediate outcomes” was not reassessed.

In terms of effective implementation, the literature paints a mixed picture. The IMF (2023e: 21) found positive examples; for example, citing Pakistan’s issuing of fines against financial institutions for AML/CFT deficiencies.

However, others such as Shah (2021) argue that Pakistan’s implementation of FATF requirements faces significant structural limitations. Sultan et al. (2022) found that, in terms of implication of its AML legislation, Pakistan has convicted only one person for money laundering and has made limited use of asset confiscation processes. They also found that, while FATF successfully led to the State Bank of Pakistan to exert pressure on financial institutions and other regulated entities to file more suspicious transaction reports (STRs), the majority of these STRs were poor in quality (Sultan et al. 2022: 4). They argue that implementation is held back by the lack of required resources and the availability of a forward-looking plan.

Similarly, Zia at al. (2022: 3; 13) argue that international standards have helped Pakistan obtain an improved score in the Basel AML Index, but implementation in Pakistan, especially investigations and prosecutions, is limited by “institutional incapacity, lack of coordination between local law enforcement and international intelligence agencies and a lack of political will”.

Panama

Panama was first placed on the FATF grey list from 2014–2016 and then again in June 2019, following deficiencies identified in its MER report (Basel Institute on Governance 2023: 1).

During this first period, the IMF published two reports assessing Panama’s compliance with the FATF criteria, which helped inform its arrangements with Panama (Ylönen 2017: 9). However, Ylönen (2017: 10) suggests these reports went beyond the FATF criteria and addressed a wider scope of illicit finance, including Panama’s financial secrecy regime and shortcomings in automatic tax information exchange.

While the IMF claims that “FATF’s decision to include or exit a member country from its list cannot be made a condition in a fund-supported program” (IMF 2023d: 23), based on the MONA database (IMF n.d. b)it appears that a condition was placed in its 2021-23 arrangement with Panama to “adopt measures to strengthen the effectiveness of the AML/CFT framework to support the country’s efforts to exit the FATF list of jurisdictions with strategy (see Code 804)”. Panama exited the grey list in October 2023.

The IMF (2024 a) welcomed this but notably also recognised that “failure to consolidate recent progress on the AML/CFT framework risks undermining international confidence in Panama’s financial sector”. Specifically, it said Panama should address risks emerging from virtual assets and implement measures such as beneficial ownership. Therefore, the IMF seemed to recognise that more needed to be done to ensure effective implementation. Similarly, the Basel Institute on Governance (2023: 3) argued that Panama’s further progress depended on addressing factors such as serious corruption and challenges to the independence of the judiciary.

World Bank arrangements with Panama also have integrated illicit-finance related conditionality. Following the 2016 leak of the so-called Panama Papers, which implicated the Panama based offshore finance firm Mossack-Fonseca in illicit financial flows in the form of tax evasion and money laundering practices, the World Bank included international tax and AML/CFT conditions in its DPF arrangement with Panama (World Bank Group Equitable Growth, Finance, and Institutions 2017: 19-20). It noted that these were “historically isolated topics” but argued that this engagement helped Panama to more effectively adhere to the common reporting standards on tax payments and implement an AML regime.

Conclusions

The marked recent uptake in illicit-finance conditions in IMF and World Bank arrangements speaks to the recognition of the criticality of countering illicit finance to broader macroeconomic stability and development outcomes. Though, within the reviewed literature, the IMF appears more engaged and deliberate in this policy area then the World Bank.

Nevertheless, studies of this nature into the effectiveness of such conditions would benefit from improved availability, consistency and comparability of data. For example, disaggregation of conditions into consistent sub-categories could help to analyse what kind of illicit-finance conditions are more currently more effective than others.

While the challenges of measuring effectiveness must be reemphasised, it is clear from the literature that illicit-finance related conditionality is a powerful tool due to the financial assistance at stake for the recipient country. It appears reasonably successful in achieving technical compliance, but it is difficult to draw conclusions about the effectiveness of its longer term implementation.

Many of the doubts about the effectiveness of conditionality are the same doubts levelled at global efforts to curb illicit finance in general, for example, achieving a balance between over-ambitious and under-ambitious actions. However, there is evidence that the IFIs are conscious of these struggles. IFIs rely on FATF standards as a benchmark for effectiveness, but are also willing to break with the FATF on certain points.

There may be an inherent tension between the short-term nature of IFI arrangements and the reforms necessary to achieve long-term resilience to illicit finance. Enhancement of IFI illicit-finance related conditionality could be achieved by strengthening funding for costs associated with effective implementation, such as capacity development and expansion.

In this vein, the Open Contracting Partnership and Open Ownership (2021: 4) recommends the IMF “invest in sustained follow-up on implementation that incentivises and encourages meaningful, lasting reform” and supports the formation of multi-stakeholder groups towards this goal.

Annex 1: examples of IMF illicit finance-related conditions

This table comprises a list of conditions listed under the economic descriptors 1.4. “Anti-corruption legislation/policy” and 6.1. “Financial sector legal reforms, regulation, and supervision” in the IMF’s database as of 8 March 2024. The list was selected by the author for illustrative purposes and is only a sample of the much larger dataset of conditions. For further details on these conditions, the reader is invited to explore MONA database (IMF, n.d. b).

|

Country |

Condition (as described in the IMF’s MONA database) |

|

Afghanistan |

Publish on http://anti-corruption.gov.af/en, both in Dari and in English: names and positions and asset declarations of officials not listed in the constitution who have declared their assets as of 2017 in line with the asset declaration legislation enacted consistent with the end-December 2017 structural benchmark, and mechanisms to access their declarations. |

|

Afghanistan |

Strengthen our AML/CFT regime by implementing an action plan based on the recommendations of the February 2011 assessment by: (i) submitting amendments to the AML/CFT law to parliament as necessary; (ii) increasing the capacity of FinTRACA, including by hiring additional staff as needed; (iii) expanding MSP registration and implementation of reporting to MSPs in areas currently inaccessible or security reasons if and when the security situation allows; and (iv) enforcing MSP reporting by dedicated software in all reporting areas where it is technically and logistically feasible. |

|

Albania |

Strengthen governance in relation to the public administration by: ii) starting the enforcement of procedures to implement the law on the asset declaration of public officials developed in consultation with the World Bank. |

|

Albania |

Develop and discuss with IMF staff an Action Plan for implementing the recommendations of the Financial Sector Stability Assessment Report. |

|

Antigua and Barbuda |

Amend legislation to effectively combat money laundering and financing terrorism. |

|

Argentina |

Submit to congress amended AML/CFT Legislation (Law 25.246), in accordance with the international standard, and considering inputs from experts, academics, relevant civil society institutions, and Fund staff, for its consideration by congress in the course of 2022 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Submit to the Federation parliament a new draft law on banks and other lending institutions in line with IMF staff recommendations. |

|

Burundi |

In accordance with the laws of Burundi, the FBu 6 billion and the deeds for 25 properties belonging to Interpetrol that have been placed under seal will remain in place until a court decision has been reached on the Interpetrol case. |

|

Cape Verde |

Complete Action Plan of task force assessing measures to ensure that financial sector regulation and supervision is in line with best international practice, including provisions applying to IFIs and AML/CFT. |

|

Djibouti |

Increase the staffing of the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU), its resources, and its independence, to enable it to carry out its mission properly, taking account of the recommendations of the AML/CFT mission of the IMF Legal Department. |

|

Ecuador |

Enact new AML/CFT legislation to strengthen the AML/CFT framework in line with the FATF standards. |

|

Gabon |

Preparation of the first report on the operations of the Commission Against Illicit Enrichment. |

|

Guatemala |

Complete off-site inspection of offshore banks |

|

Honduras |

Implement the Law on Beneficial Ownershio, make operational a comprehensive beneficial ownership registry |

|

Republic of Ireland |

Agree on terms of reference for the due diligence of bank assets by internationally recognised consulting firms. |

|

Jamaica |

Improve frameworks for AML/CFT. |

|

Jordan |

Introduce into the GST Law "place-of-taxation" rules for GST in line with international best practices |

|

Kenya |

Submit to the National Assembly, the draft amendments to the POCAMLA and POCAMLR, to be in line with FATF standards addressing the legal and regulatory gaps identified in the Kenya Mutual Evaluation Report 2022 to support anticorruption efforts. |

|

Kyrgyz Republic |

Resubmit to Parliament the draft AML/CFT law in line with international standards. |

|

Lesotho |

Submit to Parliament the new Financial Institutions Bill, which incorporates amendments to deal with supervision of NBFIs by the CBL, and unlawful business practices, including Ponzi schemes. |

|

Madagascar |

Adopt implementation decree for the law on illicit asset recovery, including the setting-up of the illicit asset recovery agency, with a dedicated budget allocation in the 2021 revised Budget. |

|

Malawi |

Submit to parliament amendments to the AML/CFT Act, the Penal Code, and the Corrupt Practices Act in line with the FATF standard and the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC). |

|

Mauritania |

Finalize the national risk assessment with respect to AML-CFT, accompanied by an action plan, and submit them to the Council of Ministers |

|

Moldova |

"Complete identification of UBOs in all banks: “All remaining banks" |

|

Nepal |

Submission to Parliament of draft Anti-Money Laundering Act. |

|

Niger |

Issue a legal instrument requiring the collection of beneficial ownership information of companies awarded single tender or sole source contracts , except defense and security-related contracts, and their publication on the Public Procurement Portal. |

|

Pakistan |

Establish a robust asset declaration system with a focus on high-level public officials |

|

Rwanda |

Finalization of action plans, including progressive penalties, for bringing commercial banks into full compliance with banking regulations by 12/31/04 |

|

Serbia |

Implement items listed in Serbia's action plan to address the significant AML/CFT weaknesses identified by the FATF. |

|

Seychelles |

Implement a risk-based approach to the supervision of banks and trusts and company service providers, consistent with the FATF standard. |

|

Uganda |

Adoption through the Financial Intelligence Authority (and Ministry of Finance) of a regulation that requires financial institutions to identify and apply enhanced due diligence measures for domestic Politically-Exposed Persons. |

|

Uganda |

Development and implementation of tools for riskbased AML/CFT supervision of the financial sector. |

Annex 2: examples of World Bank illicit finance-related conditions

This table comprises the list of prior actions listed under the theme code 312 (“financial sector integrity”) in the World Bank’s database as of 8 March 2024. The World bank describes the database as “A database of prior actions for all development policy operations since fiscal year 2005 is updated annually at the end of each fiscal year by the Operations Policy and Country Services Vice Presidency” (World Bank, n.d.).

|

Country |

Condition (as described in the World Bank’s prior action database) |

|

Argentina |

The Borrower has enacted a corporate criminal liability law strengthening the anti-corruption framework and bringing the Borrower in line with international standards, as evidenced by Law No. 27,401. |

|

Bolivia |

h) SBEF incorporated in 2003 the review on Anti-Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) into bank Inspection manuals and on-site inspections |

|

Bolivia |

j) Submit law to Congress, adopting revised the 40+8 Recommendations of the Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF). |

|

Cabo Verde |

Reduced exposure of off-shore banking as shown by the closure and cancellation of license of a non-compliant off-shore institution as evidenced by the Decree No 4/2009, published in the Boletim Oficial, Serie I, Number 7, dated February 19, 2009. |

|

Colombia |

• Lower the impact of illegal activities on the financial sector by strengthening the Anti Money Laundering/Combating the Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) regulatory framework through the issuance of decree 3420 (2004) reorganizing the Comisión de Coordinación Interinstitucional Contra el Lavado de Activos |

|

Colombia |

Reduce the risk of money laundering and financing of terrorism through: (i) the dubmission to the legislature on December 19, 2005 of draft Law No. 208 of 2005 criminalizing the financing of terrorism and stregthening the budgetary and institutional capacity of the Financial Intelligence Unit; and (ii) the issuance through MHCP of Decree No. 2515 dated July 22, 2005 for the stregthening of the budgetary and institutional capacity of the Financial Intelligence Unit |

|

Colombia |

The Borrower has strengthened its ability to conduct the administrative intervention of the entities that carry out unauthorized financial intermediation activities, by collecting resources or cash from the public without proper authorization or regulation by the Financial Superintendency, through a series of actions aimed at providing the Superintendency of Companies with the legal mandate to take strategic and precautionary measures, including inter alia: taking control of said entities, taking possession and/or ordering the freezing of their assets, and returning resources or funds to the affected persons, as evidenced by the enactment of Decree Nº 4334 |

|

Colombia |

Prior action #5: The Government has adopted measures for preventing, controlling and sanctioning contraband, money laundering and tax evasion, as evidenced by Law No. 1762 dated July 6, 2015 and published in the Official Gazette on July 6, 2015. |

|

Guatemala |

Guatemala taken off list of non-cooperative countries of the Financial Action Task Force |

|

Guatemala |

Establishment and operation of a Special Investigating Unit in the banking Superintendency, responsible for the investigation of illegal financial activities. |

|

Guatemala |

The Superintendence of Banks has strengthened its supervision of financial transactions of High Risk Institutions, including significant transactions with Public Sector Entities, by mandating: (a) financial institutions to carry out enhanced due diligence of business relationships with State Contractors, including bank accounts; and (b) all Regulated Entities to comply with procedures for managing and addressing the risks related to money laundering and financing of terrorism, all pursuant to the Borrower’s Law No. 67-2001, as amended to the date of this Agreement, and as evidenced by the Superintendent´s letter No. ___ dated______. |

|

Guyana |

The Recipient has enhanced the enforcement of the existing legal framework for anti-money laundering by improving the effectiveness of the investigation and prosecution process by giving the authorities adequate time to collect the evidence. |

|

Honduras |

• The Interinstitutional Committee for the Prevention of Money Laundering has been established. |

|

Honduras |

The Congress has: • (a) approved an amendment to the Criminal Code to include the financing of terrorism as an autonomous crime and the amendment has entered into effect; and |

|

Honduras |

• The Know Your Customer (KYC) policy has been implemented in all the banks, finance companies and savings and loans institutions subject to CNBS supervision. |

|

Indonesia |

The Capital Markets and Financial Institutions Supervisory Agency (Bapepam-LK) has strengthened the protection of investors through separation of accounts of brokers and investors under Regulation No. V.D.3. |

|

Iraq |

The Borrower passed the Combatting of Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism Law No. 39 of 2015, aimed at reducing money laundering activities and the financing of terrorism. |

|

Liberia |

The Recipient has adopted anti-money laundering and anti-terrorism financing regulations to enhance transparency and accountability. |

|

Liberia |

The Recipient has facilitated the effective operation of its Financial Intelligence Unit through issuing: (a) Regulation on Currency Transaction Reporting for Financial Institutions (FIU/CBL/SRI A-CTR/02/2016); (b) Regulation on Suspicious Transaction Reporting for Financial Institutions (FIU/CBL/SR2ASTR/ 02/2016); (c) Regulation for Further Distribution and Action on the UN List of Terrorists and Terrorist Groups (FlU/OR1A-ER/02/2016); and (d) Regulation Dealing with Cross-Border Transportation of Currency and Bearer Negotiable Instruments (LRA/FIU/ORI-TCN/02/2016). |

|

Moldova |

Strengthened its asset declaration regime by (a) enacting amendments to the NIA Law, the Law on Declaration of Assets and Interests, the Criminal Code, and the Contravention Code; (b) adopting a regulation on the methodology for verification of asset declarations and conflicts of interests; and (c) launching the NIA’s electronic asset declaration and verification system online. |

|

Morocco |

• Adoption by the Council of Government of a draft law on the fight against money laundering |

|

Mozambique |

The Recipient's Parliament has enacted the Anti-Money Laundering/Combating Financing of Terrorism Law as evidenced by the Official Gazette Nr.64 dated August 12, 2013. |

|

Mozambique |

The Recipient's Council of Ministers (CoM) approves Anti-Money Laundering/ Counter Financing of Terrorism (AML/CFT) Law Regulations as evidenced by Decree No. 66/2014 published in the Boletim da Republica No. 87 dated October 29, 2014 |

|

Nepal |

The Cabinet has approved the Asset (Money) Laundering and Prevention Regulations. |

|

Nepal |

The NRB has revised its directive to the BFIs to implement the Asset (Money) Laundering Prevention Regulations. |

|

Pakistan |

Issuance of master circular containing consolidated instructions on financial disclosure. |

|

Pakistan |

The Ministry of Finance has completed the National Risk Assessment (NRA) for Anti‐Money Laundering and Combatting Financing of terrorism (AML/CFT). |

|

Pakistan |

The Federal Board of Revenue has notified the Benami Transaction (Prohibition) Rules of 2019, mandating all commercial banks to conduct biometric verification of all bank account holders, as instructed by the State Bank of Pakistan |

|

Panama |

The Borrower, through the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, has taken initial actions aimed at conforming with the Common Reporting Standards for Automatic Exchange of Financial Account Information in Tax Matters (CRS) through its commitment to adhere to the CRS by 2018, as evidenced by Notification D.S.-MIRE-2016-25092, dated May 9, 2016. |

|

Panama |

The Borrower, through MEF, has submitted to the National Assembly a draft bill to establish tax evasion as a predicate offense for money laundering, as evidenced by the Draft Bill No. 591 submitted on January 18, 2018 to the National Assembly |

|

Paraguay |

The Government’s executive branch has presented to the Congress for approval, the Anti-Money Laundering Draft Law which contains provisions for, inter alia: (a) the definition of money-laundering as a crime; (b) the establishment of a centralized intelligence unit of the Government to deal with anti-money laundering issues; and (c) the definition of financing of terrorism as a crime. |

|

Paraguay |

To support the facilitation of reduction of tax evasion, the Borrower has amended the Criminal Code to criminalize money-laundering of assets obtained from tax evasion |

|

Samoa |

The Recipient, through its Cabinet, has approved and published a national strategy to mitigate money laundering and terrorism financing risks. |

|

Seychelles |

The Borrower through is National Assembly approved new anti-money laundering and combating the financing of terrorism anti-money laundering/combatting the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT) Act 2020 and Beneficial Ownership (BO) Act 2020 to strengthen the domestic financial sector and to establish and maintain an up to date register of beneficial owners. |

|

Sierra Leone |

The Recipient’s Anti-Corruption Commission has submitted to Parliament for approval an Asset Disclosure Regulation which inter alia defines the scope of all government officials covered by said regulation and includes an effective, non-discretionary administrative sanction for noncompliance with asset disclosure filing obligations as evidenced by the letter dated January 25, 2019 from the Clerk of Parliament. |

|

Tajikistan |

The Recipient:(b) enacted the Law on Anti-Money Laundering and Countering Financing of Terrorism, Number 684, dated March 25, 2011. |

|

West Bank and Gaza |

The PMA has instructed banks operating in West Bank and Gaza to adopt strengthened AML/CFT internal controls, in accordance with the AML/CFT strategy adopted by the Palestinian Cabinet on November 2018, as evidenced by (i) Cabinet decision No. 16/229/17 dated November 22, 2018 adopting the national strategy for AML/CFT; (ii) PMA Circular No. 74/2019 to all banks operating in the Recipient’s territories dated March 26, 2019; and (iii) Cabinet decision dated November 22, 2018 establishing a national committee to supervise the implementation of the national AML/CFT strategy |

- There is a wide number of different instruments used by the IMF and World Bank to provide financial assistance, dependent largely on circumstances in which the assistance is requested. Some of these take the form of loans, while others do not stipulate repayment conditions. Unless otherwise specified, this paper follows on from the general literature and adopts “arrangements” as a catch-all term to describe these instruments.

- See, for example, Rickard and Caraway (2019) on austerity or Stubbs et al. (2020) on public education spending.

- Anti-money laundering is often grouped with combating the financing of terrorism (AML/CFT), including by the IMF, World Bank and the Financial Action Task Force (FATF). Nevertheless, as the IMF has stated, “while ML and TF share common attributes and exploit the same vulnerabilities in financial systems, they are distinct concepts and present different risks” and that they should be assessed separately (IMF 2023d: 8). This paper focuses on illicit finance and its overlap with AML rather than CFT.

- As of August 2023, there were 190 IMF members countries.

- According to Leckow (2002), cross-conditionality means “the IMF cannot delegate to another institution the power to establish conditions for the use of the IMF’s resources or the power to assess whether particular conditions set by the IMF have been met”. For example, cross conditionality would occur if the IMF made assistance contingent upon a country’s compliance with the standards or conditions set by another organisation, such as FATF.

- In its policy frameworks, the IMF does not appear to consistently apply a standard term to describe conditionality related to illicit finance, on occasion using financial integrity – defined as including money laundering, terrorist financing and proliferation financing – and, on others, AML/CFT (for example, see IMF 2023d.)

- The other five functions are: fiscal governance; financial sector oversight; central bank governance and operations; quality of market regulation; and rule of law.

- This figure (43) represents where mention of “the FATF” is explicitly made in the wording of the condition as reflected in the MONDA database. It does not encompass cases where the wording of a condition does not mention “the FATF”, but where the condition is the same or similar to a FATF action item, meaning that the number of IMF conditions that relate to the FATF standards could be substantially higher.

- V-Dem’s variable combines data across six different forms of corruption, including executive, legislative, judiciary and public bureaucracy giving a comprehensive indicator of how pervasive corruption is during a given year (Ataman 2022: 23-24).