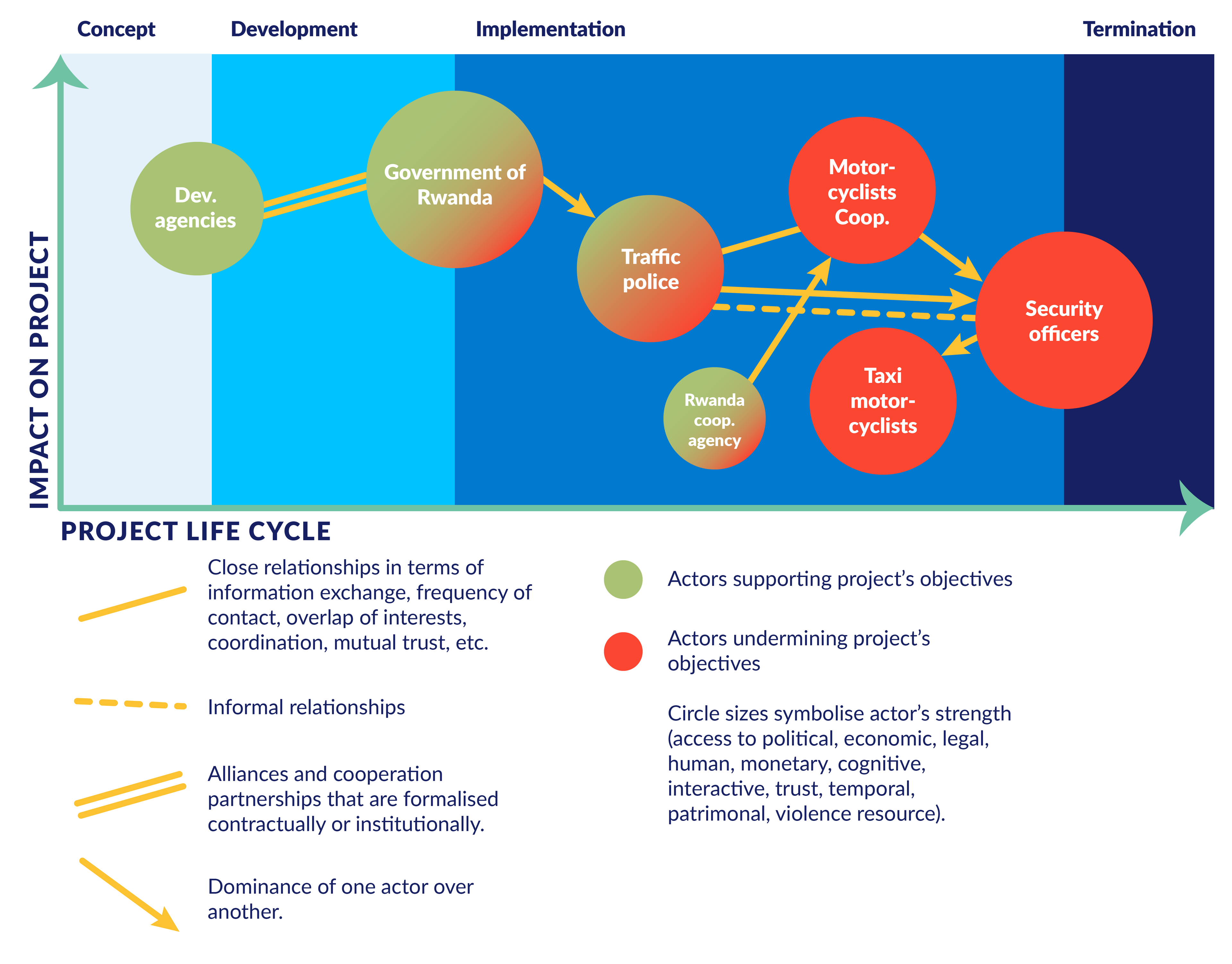

Figure 1. Social map of interrelationships: National anti-corruption strategy in the road sector – main implementing actors.

After coming to power in 1994, the Rwandan Patriotic Front spearheaded an anti-corruption campaign which today is an inevitable part of Rwandan life – be it on the streets or in the administration’s offices. The campaign has acquired both economic and social purpose in Rwanda’s bid to achieve its development goals, endow the nation with a middle-income economy, and govern efficiently in a country free from ethnic tensions.3d3d938ba8f0

Rwanda’s implementation of a ‘zero tolerance for corruption’ strategy4f73ce21748a has demanded considerable political, social, and economic resources in an attempt to change Rwandans’ cognitive perceptions and their daily experiences of corruption. Looking beyond this formal undertaking against corruption, how do the stakeholders take ownership of this policy on a daily basis? In order to understand the social embeddedness of public action in Rwanda,a60421792bb1 field research undertaken between 2013 and 2019 explored practices in a specific context, namely, the adoption of official policies (safety and security, and anti-corruption) by the taxi motorcycle (or taxi moto) sector operating on the streets of the capital, Kigali.

The research was guided by the social nature of corruption. Firstly, corruption is generally interpreted as ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain,’ which sufficiently encompasses a description of all acts of corruption in the taxi motorcycle sector. This includes corruption perpetuated by Kigali’s traffic police and the security officers of the taxi motorcycle co-operatives. Secondly, according to this social interpretation of corruption, individuals are not driven primarily by a personal desire to pursue their own interests, but instead are motivated by a strategic desire to conform to their perception of what others do or think. In this interpretation, corruption in a particular setting is sustained by normative aspects, or collective power dynamics and conformity to certain norms and behaviours.

Since the nineties, there has been a growing academic interest in the influence of social norms on corrupt practices. One of the more pressing concerns has been to better understand the elements or catalysts of corruption in order to fully grasp the relationship between society and the state. The lens of corruption is particularly useful for investigating the general public’s submission to formal and informal norms, and, in turn, the role of these norms in sustaining collective practices.

A corrupt practice can be considered a social norm if the practice fulfils an empirical expectation (conformity is expected in response to a given behaviour) and a normative expectation (conformity to a collective belief is a determining factor in the actors’ behaviour); a belief in a system of social sanctions influences the actors’ practices; and actors have developed a preference for conforming to a given behaviour.84ce42d2293c

Within a social norms framework, the research aimed at establishing the normative and customary (ie what individuals prefer to conform to) scope of corrupt practices in Kigali’s taxi motorcycle sector. Open-ended interviews with 120 taxi motorcycle drivers and security officers took place in 2013 and 2019. For both periods, taxi drivers were chosen at random on the streets to participate in the research (the interviews took place both during the day and at night), while security officers were contacted directly when they were at taxi ranks.

The interviewees were males aged between 19 and 38 years, as almost all drivers are young men. There were also numerous participant observations at the taxi motorcycle ranks and checkpoints. The research sought to identify patterns of behaviour (whether the practices are more akin to customs or are social norms), determine the actors’ level of agency (whether they act independently or interdependently), and measure the conditionality of actors’ preferences and how these relate to sanctions.

During all the open-ended interviews, the use of vignettes, or short hypothetical scenarios or stories, allowed interviewees to respond to a pertinent situation without feeling they were the focal point of the discussion. This method was selected as a way to understand the social basis of the corruption and the importance of reciprocal norms in the taxi motorcyclists’ reference networks (family and colleagues). With six years between each set of data collection, it was possible to capture the evolution of petty corruption practices in Kigali’s taxi motorcycle sector.

Apart from the vignettes, the questions asked were designed to explore the social embeddedness of public action in Rwanda, and in particular, the policy for law and order on public roads. In Rwanda, the most common form of urban transport is the taxi motorcycle. Even though the drivers operate in what is an informal economic sector, it has become highly regulated.de8c5e9291a3 In 2008, in an attempt to control the sector, the drivers were placed into co-operatives.a91229516cdd These co-operatives maintain close ties with the traffic police, as police officers give lectures on road safety during motorcycle drivers’ meetings. At those meetings, security officers respond to requests from the headquarters of the traffic police.d4900b6bff19 The investigation into the social embeddedness of public policy addresses the extent to which the rule of law has been adopted and, in so doing, examines the actors’ ‘hijacking’ of the anti-corruption strategy.

Exploring the actors’ environment

The crackdown on corruption

Rwanda’s drive to promote public and private integrity drew upon important domains, ranging from legal-disciplinary to socio-cultural. Since 1999, different initiatives have included rehabilitation programmes to foster notions of integrity and civic responsibility among population groups (Itorero and Ingando), evaluation tools measuring the performance of public servants (Imihigo), and a stringent legal operational framework for the public and private sectors. Rwanda took significant steps, such as the adoption of the 2003 anti-corruption law (revised in 2018), and decreed that any person directly or indirectly involved in bribery was punishable by two to ten years’ imprisonment and a fine totalling up to ten times the amount procured illicitly. Nevertheless, the definitive beginning of state reform and of its reorganisation in pursuit of greater integrity occurred with the adoption in 2012 of the national anti-corruption strategy and its directive of ‘zero tolerance for corruption.’

Rwanda’s strong stance against corruption has been praised. In particular, the Office of the Ombudsman is officially in charge of combatting corruption, relying on infrastructure and various important instruments to monitor transparency and compliance with regulations in all governmental sectors. Nevertheless, there are also concerns that the anti-corruption policy may be used as a tool to maintain the power balance. Immoral conduct or corruption charges are used to persecute critics and opponents. The context of low voice and accountability favours the potential use of anti-corruption policies by the powerful.It also suggests that the anti-corruption policy in Rwanda is a strong tool for maintaining order, especially within public services.

As part of the zero tolerance campaign, the administration undertook institutional reforms within the police force. A services inspectorate was created, along with a disciplinary unit and an ethics centre for the promotion of professional standards. Nowadays, each new recruit is briefed on ethics by senior officers and is trained on ethical standards and the code of conduct required. Evaluation procedures were also implemented, as well as a dedicated telephone line for denouncing any kind of corruption.

Today in Rwanda, even a vague suspicion of corruption can prompt dismissal. Suspects can also be relieved of their responsibilities or undergo a rehabilitation programme with a disciplinary unit. Between 2010 and 2015, more than 400 officers were dismissed for soliciting or accepting bribes. In 2017, another 200 were dismissed because of corruption.In addition, numerous police and security officers and taxi motorcycle drivers have been convicted of corruption, as shown in the Ombudsman’s database, and all those convictions were based on the acceptance or payment of a bribe. Such convictions amount to a purely economic and minimalist conception of corruption and would provide only a superficial interpretation of corrupt practices for policymakers and practitioners.

The administration also implemented other preventative measures to discourage police officers from corruption, such as the improvement of the social security system and a rotational system of employees. Most importantly, police officers’ salaries were doubled in 2016. Indeed, the low salaries were often thought to be one of the main reasons for traffic police corruption5b37d9103d31 because the traffic police had been living in a survival economy.b7c78e023a11 Notwithstanding this, an officer’s gross average monthly salary was approximately 70,799 Rwandan francs (RWF)3eb78feeaa0a before the pay rise, which is within the range of gross average earnings of 72,000 RWF per inhabitant in 2016. Therefore, other factors may be contributing to a decision to pursue corruption, such as the social environment in which the officers are operating.

Turning to the next group of actors in the taxi motorcycle sector, the position of a co-operative security officer came into effect in 2012. These officers’ official task is to ensure order in the co-operatives and the taxi motorcycle ranks.958106004e3f Their training curriculum does not deal with anti-corruption education. They are paid a monthly salary of 60,000 RWF – a sum comparable to the gross average earnings, but which they consider insufficient: ‘With the salary I earn at the end of the month, it’s almost impossible not to be tempted by corruption […] The salary isn’t enough and we don’t have enough social security.’3ec2409eb821

The administrative background against which the security officers operate is blurry: they sign an employment contract with, and are appointed by, their co-operative but must submit reports to and act in accordance with the directives of the Federation of Taxi Moto Drivers (FERWACOTAMO). Consequently, the security officers have considerable room for manoeuvre, given that they are not accountable to their employer and they act on behalf of an organisation that does not take heed of their activities. Therefore, in spite of the security officers’ important role in maintaining order on public thoroughfares, the federation (whether intentionally or not) has overlooked the anti-corruption measures implemented by the police.

Work conditions of the taxi motorcycle drivers

In Kigali, there are more than 15,400 taxi motorcycle driversdcf1f5e94e59 and they are an integral part of the town’s transport system.11e690c59c47 They are synonymous with the capital city of Rwanda: young and vibrant, with half of them having migrated from the countryside in search of economic opportunities. Most drivers explained that they left their rural homes, armed only with meagre savings and limited education, in the hope of finding a better life in Kigali. They chose to be taxi drivers because of the possibilities of making money quickly and because there are possibilities for career advancement. Subsequently, becoming a taxi driver is one of the most popular career choices.

The taxi motorcycle drivers are hardworking, putting in about 11 hours per day for a turnover of approximately 225,000 RWF (in 2019). Their working conditions are difficult: fatigue, hazardous driving, and dense traffic are some of the factors that increase the risk of accidents (which occur fairly frequently). Because most drivers do not own their motorcycles, they have to pay their ‘boss’ (the motorcycle’s owner) 5,000 RWF per day for its use. The owner is accountable for the insurance and maintenance of the motorcycle; however, the fuel (3,000 RWF per day), the taxi rank fee (300 RWF per day), and taxes (around 90,000 RWF per annum) are the driver’s responsibility.

Notwithstanding these costs, a driver’s salary is higher than the average Rwandan salary. According to the drivers interviewed, they can save approximately 50,000 RWF per month if they rent the motorcycle, and for those who already own one, their savings can amount to 100,000 RWF per month. This kind of income exceeds that of police and security officers, possibly leading to envy: ‘The police and the security officers are always asking us for money. We are being milked for our money!’d0c2629c0632 These monthly profits are calculated without deducting the cost of fines and corrupt practices, which evidently impact heavily on the money the drivers take home (up to a fifth of savings on average, according to the interviews).

While the taxi motorcycle drivers may be a heterogenous group, there is nevertheless some sense of unity among them. There is evidence of a subculture which bonds them, through notions of solidarity, a uniform (the official taxi motorcycle vest), the difficult working conditions shared by all, and the fact that they are far from their families who live in the countryside. In addition, the taxi motorcycle community is formalised through its compulsory registration of drivers with a co-operative. All these factors encourage the motorcyclists to see their peers as part of their reference network. The network influences their individual expectations, shapes perceptions of their interaction with the police and security officers, and ultimately forms a basis for understanding the norms relevant to their working environment.

Descriptive norms are created and reinforced during exchanges between taxi motorcycle drivers, particularly when they are in the taxi ranks – such as at the Nyabugogo rank, the hub of the Kigali transport system. When the drivers park their motorcycles, they generally chat about accidents, problems with passengers, and especially their encounters with security officers and the police. The drivers share advice and opinions on corruption, which are trivialised by the odd joke or anecdote about an event on the job:

A motorcycle taxi driver is stopped and his motorbike is impounded. The driver finds out the policeman’s address and spends the night in front of the police officer’s house. At 3am the officer comes out of his house to urinate and discovers the driver there. The officer thinks of calling for help, but the driver says that he doesn’t want to harm him. The driver just wants to know how to safeguard his livelihood so he can feed his children and that’s why he followed the officer to his house. Surprised, the officer tells the driver to go home and to come to the office the following day to collect his motorbike. The driver goes to fetch his motorbike and that evening he finds the officer to buy him a drink and finally they become good friends!f7c35abec4bc

These exchanges contribute to the process of normalising corruption, creating empirical expectations, and instilling a fearful understanding of the implications of encounters with police and security officers. At the same time, the exchanges allow the drivers to feel more confident and to learn to reduce the risks when they find themselves in similar encounters. It must be emphasised that this normative influence is minimal because there is no social sanction if a taxi motorcycle driver deviates from the norm by refusing to engage in corruption or by adopting a different attitude towards the officers. Thus, although the drivers’ professional reference network is meaningful and relevant, the drivers are independent and develop personal – not collective – expectations. As the anecdote attests, in the context of their work and in terms of the police and security officers, the drivers act of their own volition, despite being linked to the co-operatives.

Taxi motorcycle co-operatives

The 147 co-operatives set up throughout the country8f507062887d are grouped under the umbrella authority of the FERWACOTAMO. There are certain co-operatives in Kigali, like Tubane Hafi, that have up to 800 drivers registered with them. According to Law no. 2007, co-operatives are responsible for regulating the sector, and it is compulsory for the drivers to be registered with one. On a practical level, they offer services like procurement of credit, purchase of motorcycles, and mediation when conflicts occur between taxi motorcycle drivers and their motorcycle’s owner. However, they provide a rather limited service, as no co-operative may defend or advocate the collective interests of taxi motorcycle drivers.

The co-operatives collect a monthly fee of 5,000 RWF per member, in addition to an annual membership fee (around 60,000 RWF). Officially, the fees are meant to pay for the co-operatives’ operating costs (in particular the managers’ and security officers’ salaries), FERWACOTAMO membership, and the co-operatives’ provident and investment funds. Unfortunately, allegations of misappropriation of funds and extortion and a lack of co-ordination have stained the reputation of these co-operatives. All the drivers interviewed were dismissive of the co-operatives: ‘They only talk about money. They are thieves!’4829b850faad According to the official 2018 figures released by the Rwandan Co-operative Agency (RCA), 205 million Rwandan francs were misappropriated through embezzlement.4705b76b6cdd Cases are now handled by the Rwanda Investigation Bureau.

In 2017, the taxi motorcycle drivers started a petition against the lack of accountability and corruption within the co-operatives. The drivers’ petition of protest even went so far as to attract the attention of the Rwandan parliament. The main result was a change in security officers’ status to ‘disciplinary officers’.fa4e1decdea5 If the drivers had to resort to a petition in order to assert their rights, it is primarily because they feel powerless in the face of their co-operatives: ‘The co-operative managers do not advocate improvement because they cannot oppose the state;’b4c4f29bdbbe ‘The general assembly meetings are dominated by those who do not represent motorcycle taxi drivers: they only tell us about who is going to be a manager;’f63923358dad ‘Former military personnel decide who is going to manage the associations.’efa36b1ac3b4

These perceptions of constraint and dominance by others in the co-operatives relate to the notion of state structural violence,a97817682403 where state authority operates subjectively, through the violence felt by the general public, and where this authority is dispersed within every social organisation. These positions of authority are greatly inflated by horizontal structures of co-optation throughout Rwandan society, and reinforce the chain of accountability towards the centre.355c4974a686 This observation corroborates the drivers’ feelings of isolation in the face of multiple intertwining strands of formal and informal authority. Indeed, co-operatives in this instance are more a control mechanism, and far less a union advancing taxi motorcyclist drivers’ interests.

As witnessed in the interviews, co-operatives and colleagues represent only a modicum of solidarity for the taxi motorcycle drivers. In order to understand the significance of their reference networks, drivers were asked to respond to a vignette in which a colleague asks for help with a corruption issue concerning a police officer. All the drivers showed little enthusiasm for the idea of taking risks for those in their professional network, unless there was a chance of personal gain: ‘Words alone will not suffice when asking for pastureland for a cow;’38df4513b382 ’No-one does anything anymore unless he thinks he can get something out of it and for the drivers, it’s worse than in any other job.’f34f74846bb2

When the colleague was replaced by a relative of the driver in the next vignette, the response revealed strong obligations of solidarity.

Abstract from an interview with a motorcycle taxi

Joshua is a motorcycle taxi driver in Kigali. A policeman stops him. That day Joshua forgot his helmet and he does not have all his papers in order; his motorcycle is seized. Joshua understands that if he wishes to recover his motorcycle, he will have to pay approximately 60,000 Rwandan francs. He thinks of calling on his cousin, Jean-Paul, to play the intermediary role and negotiate his case.

Me: What would a biker do in his situation?

Damien: The biker would seek leniency or pay for corruption. If his cousin is strong in the police, the biker would think he will solve his problem.

Me: What do Joshua's friends and family expect from him in this situation?

Damien: Friends and family are going to be afraid it won't work and Joshua will be punished.

Me: Who has the most influence on Joshua's decision? Bikers, his family?

Damien: It's Jean-Paul who will play a big role in this situation and even in all the decisions Joshua is going to make. Family members go to collect the money to help. Bikers don't care. There are a lot of seized motorcycles and bikers don't even know who they belong to.

If the vignettes confirm the role of family support in sustaining certain corrupt practices,bdcf8cff58d9 by contrast they also highlight the weak sense of obligation that drivers have towards their colleagues. Furthermore, individualism and mistrust among taxi motorcycle drivers seemed to be more widespread in 2019 than they were in 2013. The drivers referred to acts of denunciation by colleagues when there was a risk of someone adversely affecting the taxi motorcycle profession, or when ‘spies’ in the pay of the government denounced the misdeeds of certain drivers.

The formal collaboration established between the traffic police and the taxi motorcycle cooperatives relies on security officers, who constitute the cornerstone of this collaboration. The RCA directives state that ‘the [security] officers may work anywhere at the request of the federation or of traffic police headquarters’.4c889d7ca015 Moreover, the officers may be mobilised ‘in the event of an organised police operation in which the police request the co-operative to assist and to make its officers available’ (Ibid.). The security officers are thus considered assistants in the maintenance of law and order on public roads. Nevertheless, their authority is limited in the case of taxi motorcycle drivers, and excludes general road safety. Also they are not entitled to issue fines: regulations specify that security officers shall bring offenders to motorcycle co-operatives and only representatives of a co-operative may issue fines.

Yet the reality of security officers’ practices is somewhat different from those stipulated in the regulations: ‘As a security officer, my remit comes from the police. Sometimes we get a specific instruction, a wanted notice, and we have to find the culprit.’ebd421e53b00 Security officers may also find wanted taxi motorcycle drivers and take them to the police. This kind of collaboration has implications for research and practitioners because it illuminates the potential shift of power away from police officers (formal authority) to security officers (informal, unofficially delegated authority).

Following a taxi motorcycle drivers’ petition, the RCA accused FERWACOTAMO of disorganised leadership and asked for its revamp. The RCA also requested a change in the status of security officers to ‘disciplinary officers’ – ostensibly, the idea of discipline being more constraining and less ambiguous than the notion of security. However, in practice, nobody uses the term ‘disciplinary officer,’ which attests not only to the vagueness linked to the officers’ status but also to the gap between norms and practices.

In 2019, the RCA established guidelines for ‘disciplinary measures by security agencies’ in an attempt to define the officers’ prerogatives and punishments in the event of non-compliance with instructions.851ea29de0cd This meant that, up until 2019, the security officers were not subject to any official procedures or checks. As of May 2019, ‘officers responsible for security are not authorised to impose or collect fines from co-operative members,’ even if the reality of the practices illustrated below differs from the rules that have been laid down.

Actors’s practices and their normative scope

According to Transparency International, the Rwandan police force is still perceived as the most corrupt institution in the country. Indeed, corrupt practices within the force seem to have increased by nearly 16% between 2014 and 2017, and police corruption is seen as a routine part of the taxi motorcycle drivers’ work. Yet, from the research findings, the trend is different. When interviewed in 2013, approximately 85% of the 70 motorcycle drivers stated that they had paid a bribe to the police in the month prior to the survey. By 2019, only 25% of the drivers interviewed confirmed that they had paid a police bribe, yet 100% confirmed that they had bribed security officers. In other words, corrupt practices on Kigali’s streets are no longer perpetrated by the same actors, but the practices nevertheless continue with similar patterns. The various stages in the corrupt practices can be analysed in terms of a social norms theory.

First stage: the initial interaction

When a taxi motorcycle driver is stopped, invariably he begins the conversation by begging for the forgiveness of the police or security officer in the hope of being let off lightly. The driver is quite aware that he is presumed guilty, regardless of whether any misdemeanour has been committed or not. The driver appeals to a sense of leniency in the officer, who is authority personified and can determine the price to pay for the misdemeanour: ‘How can I forgive you when you have sinned! I can’t just forgive you like that!’325a33aaa672

This exchange illustrates the actor’s interdependence, which is established through an empirical and normative expectation: by adopting a religious register, the driver hopes to obtain clemency or be in a position to negotiate. The semantic markers in the exchange normalise the negotiation process by subscribing to a specific course of action and a set of codes that are familiar to the actor. In addition, the strategic rationale behind this exchange allows, on the one hand, the driver to reduce the cost of the fine and, on the other, the police or security officers to secure some financial kickback.

‘You aren’t parked correctly! So, what do you think about that? You need to get your act together.’07e00e147aec Security and police officers regularly use this expression as an explicit sign to the drivers that they are open to negotiation. Other such signs are when a police officer refrains from opening his charge book (or tablet since 2019), and when the officer keeps the driver’s licence, inviting the driver to return for it after dropping off his/her passenger. If the police or security officer asks the driver to park his/her motorcycle and to let the passenger go, the driver knows that the officer is not open to negotiation. On the (rare) occasion when a police officer has clearly indicated a willingness to negotiate but the driver refuses to pay a bribe, the driver runs the risk of contending with an overly eager officer who will promptly enforce full payment of the official fine and then find anything else for which the driver can be fined.

Once again, these situations demonstrate the interdependence between officers and drivers, with the former having empirical expectations about the drivers’ behaviour. Fear of sanctions encourages the drivers to opt for corrupt practices, and this fear is conditioned in the officers’ favour. Thus, social norms theory rules out the hypothesis that the taxi motorcycle drivers practise corruption as a custom. Rather, by conforming to the police and security officers’ expectations, the drivers’ behaviour can be considered prudential – a way of defending their interests.6aead1ece51e

It seems that the starting point of the exchange between drivers and police or security officers is key to determining the actors’ negotiating power. The similarities among all the interviews indicate that there is a set of codified rules that is respected. The actors have distinct roles to play, with the police and security officers invariably having the upper hand in the interaction. The interdependence is based on ‘factual beliefs’ about the discretionary power of the police and security officers, both of whom epitomise authority for the drivers and are permitted to make arrests. These officers clearly have a greater influence on the exchange. Some officers, for instance, play their part with great conviction and even display hostility towards the drivers. Indeed, drivers talk of the unfriendly manner of some police or security officers, which can include preconceived ideas and arbitrary arrests. By contrast, they also speak of some officers making jokes, which is an indication that negotiation is possible.

An important difference between 2013 and 2019 is the evolution of the cost-benefit rationale behind the corruption. In 2013, the drivers could clearly identify ‘windows of opportunity’ for corruption: police officers were more ready to engage in corrupt practices later in the day (after 10.00pm, when the charge books had been filled) and at the end of the month (when they had less money). Opportunities for negotiation were more likely with those in subordinate positions as opposed to positions of responsibility, for example with young recruits rather than older police officers.

By 2019, these distinct opportunities for negotiation seemed to have disappeared completely from the police force and did not pertain to the co-operative security officers, who instead are ‘always hungry’08060fcac075 regardless of the time of day or month. This demonstrates an evolution of corrupt practices on the streets of Kigali – one where it appears that the police are not as quick to be bribed, but where security checks are now delegated to officers who are far more corrupt. While the original hypothesis for the study was based on a definition of corruption as a social phenomenon, this evolution highlights the structural aspects linked to corruption, whereby a (traffic) control system appears to be a driver of corrupt practices and the actors’ cost-benefit rationale an incentive for the corruption.

Second stage: the negotiation process

‘Turangyzanye.’ ‘Let’s get this over with.’ The police and security officers use this expression to signal the beginning of negotiation. In 2013, the discussion would take place a short distance from the police barriers. In 2019, the scene had moved to a more neutral environment that was sheltered from view. To protect their interests (by having the fine reduced), the drivers refer to their unfortunate socio-economic situations to try to invoke some sympathy. Alternatively, they talk about what the police and security officers can do with the ‘free money’ they get, adding an element of temptation: ‘Sometimes the officers say, “We’ll let you go if you give us 10,000 RWF.” What can I do?’d312379901ef

During this phase of the negotiation, only pecuniary issues are discussed. The drivers do not mention their ethnicity or geographic origins. That would be too risky because certain officers might react antagonistically to this kind of information: ‘Me, I don’t say that I come from the north. It’s President Habyarimana’s region.’add637cc0964 Thus, the actors have the empirical expectation that anonymity will be preserved. If this norm is not respected, the drivers can be put back on track by being told, ‘Don’t play around like that. You are guilty. You need to be forgiven!’df4cf7744b63

In this stage of negotiation, the security and police officers may still use coded language. For example, if they say ‘Give me Friday,’ the fifth day of the week denotes that they are asking for 5,000 RWF. Officers might also ask for ‘gutera akantu,’ literally ‘Throw in something small’ (2,000 RWF) in order for the misdemeanour to be forgotten. At times, the officers’ language is more explicit, for instance when they ask the driver to ‘buy a Fanta’ or ‘pay for forgiveness.’ Body language is used as well. Four fingers in the air mean 4,000 RWF and a fist means 5,000 RWF.

These acts of nuancing the usual meanings of gestures and words in their Kinyarwanda language illustrate a desire to conceal illicit practices. However, the interviews indicate that the twisting of meanings in this situation does not constitute a speech community with a shared set of norms,e80fbe1e972f but rather just a mutual understanding of the performative function of the expressions used. Once again, predominantly economic factors seem to be the drivers behind the corruption here – a corruption which is codified by practical norms,f5e53f1e141d and more specifically, descriptive norms.

Most bribes amount to small sums of money. The bribe is always commensurate with the real fine and is generally about half the amount thereof. For example, it is compulsory to wear a helmet for safety reasons and failure to do so incurs an official fine of 10,000 RWF, but the actors negotiate an informal fee of 5,000 RWF. ‘State bargaining’926de3b611d5 – in this case, the police and security officers’ bargaining of the official amounts set for contravening the rules of the road – shows a close link between the formal setting and informal practices. The officers’ pragmatism compels them to suggest a price for the offence that is based on official criteria, while estimating a price that is acceptable to the taxi motorcycle drivers and subsumes the risk taken. In fact, the police or security officers face a very real risk of sanctions: even for a small bribe of 1,000 or 2,000 RWF, officers can be sentenced to one or two years of prison.

A part of each interview was dedicated to exploring the notion of mediation, which is very important in Rwandan culture. When a motorcycle is impounded or when a fine is too high, the actor can in fact make use of a mediator to secure the deal and facilitate its process. This person can be a relative, a representative from the co-operative, or anyone else in the actor’s reference network who is capable of securing the terms of negotiation and ensuring the social inclusion of the actors.

For instance, if the owner of the impounded motorcycle is a police officer, they can act as mediator by using their position to persuade colleagues to release the motorcycle. Once the terms of the transaction have been set, the police officer can record the payment of a small fine in the system (for example, a broken headlight) in order to justify the impoundment and subsequent release of the vehicle. Security officers can also be prevailed upon to use their mediation skills, for which they are compensated. This kind of mediation resonates with ‘camouflage’ practices which are devised to protect and legitimise a social network and its practices by embedding, and therefore concealing, informal practices in formal procedures.de0a0b92327f

Third stage: the exchange of money

By the final stage, as the acceptance of a bribe is imminent, the interaction becomes more risky. The actor’s priorities are to minimise any risks and to secure the transaction covertly. It should be noted, however, that the need to conceal actions was less pressing in 2019 because security checks were then conducted more frequently by security officers who were less cautious than the police. The exchange of money can be deferred for a period lasting from a few minutes to a few days, depending on the time that the driver needs to procure the money. Thereafter, if the transaction involves the police, the driver is required to appear in civilian clothing (without the official motorcycle driver’s vest and helmet) when paying the bribe.

For a bribe without deferment of payment, the driver simply places the money in the palm of his hand and transfers it, by a handshake, to the security or police officer who will then discreetly place the money in his pocket. The actor can also agree to a money transfer via a mobile phone application, or use a third party (like a street vendor) in order to buy telephone credit in lieu of a cash payment.

The security officers usually patrol in pairs, thereby sharing the risks, profits, and responsibilities – sometimes one keeps a lookout while the other takes the money. Such solidarity among security personnel allows corrupt practices to be incorporated into their reference network. This sharing demonstrates the prominence of social ties in the creation of practical norms in the study environment. The reciprocity created by this solidarity serves to normalise corrupt practices and to reinforce common values among the officers while reducing the risk of betrayal within the teams.

In local jargon, when a driver is stopped and manages to bribe a police officer, he will later tell his colleagues that he had his ‘tail cut’ (gucika umurizo), meaning that he had to share his profits with someone else. The driver could also talk of ‘five sticks’ (inkoni eshanu) to denote being struck five times with a stick (5,000 RWF) by the officers, or he could say, ‘The state has hit me.’ In these expressions, corruption is associated with a loss, a misfortune, and also a social injustice linked to what the drivers consider to be an unlawful punishment. For the majority of these motorcycle drivers, corruption is just as much an act of stealing (their money) as a moral wrong, yet it is also a necessity: ‘Corruption is bad, but it allows us to continue to work.’40c28029e8df The interviews demonstrate that economic rationalisation prevails over ethical arguments, even if the drivers say that they are sad to see their money disappearing into officers’ pockets instead of being used for the community.

It is important to emphasise that the taxi motorcycle drivers are exemplary tax payers: with 32,000 drivers each paying an annual flat rate of 72,000 RWF on their profits, the drivers contribute 16% of the country’s annual tax revenue. Consequently the bribes cannot be considered an act of defiance against a taxation law, but rather a way of paying fines that are regarded too high or unlawful (especially when the fines are collected by security officers). Thus, the drivers refer to their engagement with corruption as a legitimate way of protecting their personal interests.

Social embeddedness of public policies

Delegated management of road traffic safety

While the number of cars and motorcycles in circulation in Rwanda grew exponentially (from 61,000 registered vehicles in 2009 to 180,137 vehicles in 2018), the number of traffic police checks on the roads has reduced. Hypothetically, the strong crackdown on corruption and the dismissal of a considerable number of police officers have led the police services to limit the interaction between their officers and the public. As a result, the government’s zero tolerance approach to corruption has had some paradoxical consequences for their road traffic safety policy.

Indeed, on the streets of Kigali, the withdrawal of the police force from traffic control duties opened the door for security officers to assume de facto the position of a road safety regulating authority for the taxi motorcycle drivers; de facto because there is no formal delegation of such an authority, which is therefore in operation without any checks and balances to curtail it. Higher-level directives for the security officers simply mention that they must be available for police operations. These officers also assume the right to stop taxi motorcycles on public thoroughfares, whereas the guidelines state that they are only responsible for safety and security at the taxi ranks.3e637d86121a

The situation depicted in Rwanda is about an ‘informal privatisation’ of security norms. This kind of corruption appears simultaneously ‘transgressive’ and ‘palliative,’ in the sense that it ‘seriously undermines the delivery of quality public services’ but, over time, in its own ‘makeshift’ way, it facilitates service delivery.ec7a7a630cec As a result, the security officers’ practices are tolerated because these officers have made themselves indispensable: ‘Once, the security officers were suspended for two weeks, but there was such chaos among the drivers that we were quickly reinstated.’c140ec6e3457 Also, through their intervention method – consisting of patrols where the drivers are arbitrarily stopped anywhere on the streets – the security officers replicate a vertical power structure and reassert the omnipresence of the state while simultaneously pursuing their own interests.

Nonetheless, Kigali’s streets are not places of lawlessness: ‘informal privatisation’ of security norms by security officers implies a strategic ability to self-regulate in order to keep their status and avoid sanctions. On the one hand, the security officers are accountable to their hierarchy because they obtained their jobs (and, more especially, can keep them) through their relations within the co-operatives and/or FERWACOTAMO. This reinforces corrupt practices: ‘Seeing that we’re asked for money to guarantee our jobs, we obviously have to make a plan to get money from the drivers,’ said one security officer.83029e435223 On the other hand, fear of infiltrators within the organisation, denunciation, and reprisals are sufficient motivation for respecting the empirical norms, without overstepping the mark. At first glance, the actors’ economic rationale seems primarily shaped by ‘the constraints and dependencies linked to their interpersonal relations’.33e91e10fe81

The social representations of expected behaviours should also be considered. The use of cryptic language and mediators, as well as the security officers’ rationale behind the redistribution of their profits within their own ranks, are all examples of embedding rules within a social context. Likewise, the transfer of police authority to security officers illustrates an ‘institutionalisation’ of the business of corruption, precisely because the practices remained unchanged even when the actors were different.

Hence, the state’s regulatory actions are interwoven with social rules specific to the work environment studied and to a larger social context. The somewhat obscure administrative framework which delegated a limited authority to the security officers then facilitated abuse of that same authority. In so doing, formal governance itself created the paths which permitted the officers to circumvent any official constraints, thereby fusing formal processes with informal ones. This concept of social embeddedness is one where corruption’s supply and demand go beyond the actors’ interpersonal relationships and are socially organised,df190701f243 rather than being influenced by the needs and limitations of those relationships.c856e129f424

The actors’ power game

In light of the public’s concerns over road safety, the taxi motorcycle drivers are often perceived as a dangerous element on the roads. The security officers exploit this perception to legitimise the measures they take to ‘correct’ their colleagues and justify their own practices. Consequently, the motorcyclists become cash cows because of the images conveyed by the media and authorities – ill-disciplined youth, a community allowing delinquents into its midst, and the cause of numerous road accidents. The authorities do not consider the motorcyclists as political actors, but rather as trouble-makers.378aebe0b7a5

Apart from their official functions, the co-operatives and FERWACOTAMO are used as a mechanism of control over the taxi motorcycle drivers. Indeed, their presence is a divergent element in the centralised development plans (especially the master plan for the town of Kigali). In a country where silence is institutionalised, the motorcyclists’ resistance, for instance by demonstrating in Kigali to defend their sector2d043dfd1bae or organising a petition, emphasises both the strength of their community and the pressures that they face.

The security officers are confident of their role because they are acting in the name of the state: ‘My power comes from the association managers and state institutions like the Rwanda Co-operative Authority, the police, and the city of Kigali.’b334b24d079d In power relations between security officers and motorcyclists, the officers exploit formal rules, the symbolic power of the authorities, and the motorcyclists’ insecurity and their weak capacity for mobilisation within the co-operatives. Consequently, the officers’ attitude is sculpted by a mixture of prudential (related to their personal interests) and non-prudential (the negative perception of taxi motorcycle drivers) normative beliefs.

Emboldened by their own sense of legitimacy in ‘correcting’ the taxi motorcycle drivers, with the help of their professional network and the lack of bottom-up accountability, the security officers make use of existing regulations to their own advantage – as if selecting from a repertoire of possible moves at their disposal. Even if the corruption does have some benefit for the drivers, they nevertheless see it as something akin to plundering, which inevitably creates tension for the officers: ‘We ask them for their papers but they don’t have them and they just drive off. They insult us, some of us have even been hit.’099189c139e2 This hostility shows the extent to which the motorcyclists feel helpless in the face of what they perceive as a ganging up between security officers and the police force: ‘The traffic police don’t listen to us. When a driver tries to explain his innocence and says that the security officer is persecuting him, the police officer just adds another charge called “failure to comply.”’3849444fdce6

These power relations expose the real issue: at face value, a simple bribe belies an abuse of power, a breach of trust, and an abuse of a dominant position. This is institutionalised corruption. Corrupt practices are supported by structural elements (the delegation of authority to security officers and the lack of supervision of those officers) and by interpersonal relationships and power relations (police and security officers’ domination of the motorcyclists, and the redistribution of officers’ bribes to superiors).

Personal relationships also develop among security and police officers. According to the security officers interviewed, these relationships develop naturally without any kind of exchange of gifts. In addition, corruption is equally supported by normative aspects (the officers’ expectations and sanctions in the event of non-compliance by the motorcyclists). In this way, the social embeddedness of law and order and anti-corruption policies reveals the actors’ agency – an agency that is conditioned by social, institutional, and cognitive environments, and which highlights the Rwandan state’s use of formal and informal mechanisms of control.

Finally, the ultimate cost of corruption extends far beyond principal–agent corrupt practices and may affect end-users and citizens. The author faced a very dangerous situation when his taxi motorcycle driver tried to escape security officers and he and the driver ended up in a ditch. This demonstrates how road safety may be compromised by the need to evade officers out of fear of fines or bribery. Users may also suffer a service price inflation, as the costs of corruption are likely to be reflected in the market price.

Furthermore, continued bribery is not only a threat to the rule of law, but also to political and social integration. While citizens are well aware of the corrupt practices in the taxi motorcycle sector, they are unwilling to file reports and risk dealing with the authorities. In so doing, they are ultimately supporting the unfair balance of power, and the power abuses that accompany this imbalance. Accordingly, this study reiterates that curbing corruption requires good, transparent governance which practises social accountability and freedom of speech.

Assessing the effectiveness of the ‘zero tolerance’ strategy

If corruption among the traffic police staff has diminished over the research period (2013–2019), corruption practices have remained in the sector and certainly have perpetuated despite the tight legal and procedural anti-corruption framework in place. The relative impact of the ‘zero tolerance for corruption’ policy is highlighted by this study, in which the policy’s efficacy appears to diminish according to the normative and social contexts and the power relations among the actors. The state is thus an object of negotiation on a daily basis, mainly by the security officers who have the will and the capacity to promote their personal interests above any collective interest.

Social norms theory has helped to identify the nature and catalysts of corruption, underlining the actors’ diminished ethical considerations and a low prevalence of social norms. Corruption practices are more aligned with descriptive norms and are influenced by the cost-benefit rationale behind the decision to engage in corruption. The methodology enables the identification of possible anti-corruption policy changes to the study environment by considering, for instance, the need to promote the status of taxi motorcycle drivers (changing attitudes), increasing the security officers’ sense of accountability, and reducing incentives for corruption (eg decreasing the cost of fines).

The research emphasises the structural aspects linked to corruption, where weak or non‑existent supervision of actors seems to play a markedly determining role in permitting corrupt practices. The findings are in line with other studies correlating the increased risk of corruption when delegated authority is involved. In this specific case, weakness in supervision procedures is intrinsic to formal governance because the state relies on the co-operatives to keep order, despite the lack of transparency in its administration. By adding new layers of supervision without accountability and transparency, as in Kigali’s motorcycle federation and co-operatives, the state generates potentially more avenues for corrupt practices.

Furthermore, the research shows how the co-production of order (by state and state-endorsed actors) and the social embeddedness of Rwandan public policies generate a co-production of corruption. Taking the form of a vicious circle, the deployment of a zero tolerance for corruption builds on and feeds a verticality of power, masking and ultimately perpetuating certain embezzlement practices that are part of the Rwandan governance.

With the informal woven into the fabric of formal governance, and combined with a nominal understanding and superficial application of the notion of corruption (ie only considering bribes and not the abuse of power), the disparity between Rwanda’s image (zero tolerance for corruption) and the daily reality of Rwandans emerges. If this facet of corruption is not seen in international rankings, it is because the reach of coercive power ensures that speech is suppressed, and because it is less visible and gets less attention than the financial implications of petty corruption.

Lastly, the deployment of the ‘zero tolerance for corruption’ policy appears to have an additional objective: the perpetuation of the current status of law and order and of the balance of power in Rwanda, favouring those in power. The analysis is in line with other studies demonstrating that anti-corruption measures are calibrated to advance particular interests. The tolerance of petty corruption practices may just be a trade-off for securing state control by empowering co-operatives to maintain law and order on the streets of Kigali. The price of this arrangement is primarily paid by the weaker ones in this balance of power, ie the taxi motorcycle drivers whose income has actually decreased during the period of study.

Recommendations for development practitioners

- A thorough understanding of the interests and aims of stakeholders and of the structure of social relationships is necessary for realistic concept design and to help development aid managers in project implementation. It is important to reduce the implementation gap while maximising project outcomes. Stakeholders may have divergent needs and aims, and already-established power imbalances may hamper anti-corruption measures and outcomes. For example, development practitioners may want to reduce corrupt practices, while political elites may use anti-corruption policies to increase control mechanisms at the expense of a reduction in corruption. State officers may be content to maintain the status quo, while taxi motorcycle drivers wish to maximise their income without resorting to bribery. The complexity of these divergent interests and the interplay of relationships should never be underestimated.

- This case study shows how interviews and participant observations are useful in establishing a social diagnosis, and ascertaining actors’ levels of agency, beliefs, expectations, and preferences, as well as the strength of their reference networks. Social diagnosis could help development practitioners take into account the multiplicity of influences, and to map out and align the various actors, entry points, pathways, and possible risks to consider in counter-corruption initiatives. It would be an in-depth complement to the standard political economy analysis done by most development actors. At the strategic level (during development phase), theory of change should consider social mapping, thereby reducing the risk of strategic failures and corruption opportunities.

- Once a diagnosis has been made, the implementation phase may introduce social change through legal leverages (new codes of conduct and control systems, and laws to create new normative expectations); information programmes (campaigns targeting social expectations that need to be changed); and economic actions (trying to positively impact the cost-benefit rationale towards promoted behaviours). Adequate deterrence and sanction systems should be implemented by those in authority in order to avoid negative spin-off and reduce the gap between programme objectives and effective outputs and outcomes.

- Baez Camargo 2017.

- Republic of Rwanda 2012b.

- Bierschenk & de Sardan 2014.

- Bicchieri 2016.

- For more information on the creation of the co-operatives, see: W. Rollason. Motorbike people: Power and politics on Rwandan streets. Lexington Books. p. 46.

- Goodfellow 2015.

- Agence Rwandaise des Coopératives 2019.

- One euro equalled about 1,000 RWF, with the exchange rate being about the same between 2013 and 2019.

- Bozzini 2014.

- Baker 2007.

- Interview with a security officer, 9 December 2019.

- Agence Rwandaise des Coopératives 2019.

- Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Authority 2018.

- Rollason 2017a.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Remera, 12 September 2013.

- Participant observation. Discussion between two taxi motorcycle drivers, Nyabugogo taxi rank, 15 September 2013.

- Rwanda Utilities Regulatory Authority 2018.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Gasabo district, 12 September 2013.

- Amani 2018.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Kicukiro, 10 September 2013.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Kiyovu, 08 September 2019.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Nyarutarama, 10 December 2019.

- Agence Rwandaise des Coopératives 2018.

- Uvin 1998.

- Ingelaere 2014.

- Translation from Kinyarwanda of ‘Amatama masa ntasabira inka igisigati’.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Gasabo district, 10 December 2019.

- Baez Camargo & Koechlin 2018.

- Agence Rwandaise des Coopératives 2019.

- Interview with a security officer, Kicukiro, 8 September 2013.

- Agence Rwandaise des Coopératives 2019.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, 12 October 2013.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Nyabugogo, 13 August 2019. In Kinyarwanda, ‘Kwibwiriza’ translated as ‘Get your act together.’

- Bicchieri 2016.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Nyabugogo, 15 August 2019.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Nyabugogo, 15 December 2019.

- Ibid.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, Nyabugogo, 25 September 2013.

- Olivier de Sardan defines a practical norm as ‘the diverse set of informal, de facto, tacit or latent rules that underpin those actors’ practices which do not converge with public norms.’ J.P Olivier de Sardan. 2013. Les normes pratiques: pluralisme et agencéité.

- Labov 1989.

- Bierschenk & de Sardan 2014.

- Baez Camargo & Koechlin 2018.

- Interview with a taxi motorcycle driver, 23 August 2013.

- Agence Rwandaise des Coopératives 2019.

- Interview with a security officer, 26 September 2019.

- Bierschenk & Olivier de Sardan 2014.

- Interview with a security officer, 10 December 2019.

- Granovetter 1985.

- Polanyi 1983.

- Granovetter 1985.

- Rollason 2017b.

- Rollason 2019.

- Interview with a security officer, 26 September 2019.

- Interview with a security officer, 15 September 2019.

- Interview with a security officer, 23 September 2019.

- Interview with a security officer, 15 September 2019.