The role of environmental, social, and governance reporting in achieving sustainable governance

Sustainability reporting is intrinsically aligned with the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). It involves tracking and reporting progress on environmental, social, and governance (ESG) issues, providing a structured approach for public and private organisations to demonstrate commitment towards sustainability targets. With tightening legal frameworks and market pressures, public and private organisations need to report on their compliance with ESG criteria. This is particularly the case for anti-corruption requirements as part of governance aspects.

The effectiveness of ESG reporting for anti-corruption remains a contested issue. Proponents highlight its potential benefits, such as reducing financial misconduct and corporate fraud, particularly under male leadership, and improving accountability in public investments. Organisations like the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS) see ESG reporting as an opportunity to enhance financial transparency by integrating anti-financial crime (AFC) metrics into corporate disclosures.

However, sceptics point to its limitations, such as its inability to predict corporate scandals,f59599ba7e8d particularly in self-regulated environments like the USA, where political corruption can undermine voluntary disclosures. Moreover, ESG reporting can align with the fraud triangle, as the pressure to meet ESG expectations and the opportunity for ‘greenwashing’ or data manipulation may incentivise misrepresentation rather than meaningful change. In some cases, reporting on corruption may even pose a legal risk, deterring companies from full transparency. These tensions underscore the need for robust and reliable frameworks to realise ESG’s anti-corruption potential.

Guided by the following research questions, we set out to assess these anti-corruption provisions and reflect on their ability to reduce corruption, looking at both frameworks and practice: (1) How have ESG reporting standards developed, and how can these frameworks be improved to address anti-corruption measures? (2) Is there any evidence that ESG reporting can reduce corruption or fraud?

For this report, we performed desk-based research, including academic and grey literature (media articles, reports, guidance, etc.) on ESG reporting and anti-corruption, and regulatory frameworks. We also reviewed sustainability and annual reports from the 50 largest development cooperation organisations (in terms of official development assistance (ODA) volume, on the basis of International Aid Transparency Initiative (IATI) data, assessing anti-corruption information from those organisations. This group includes a wide range of organisations, such as multilateral organisations (eg, UN agencies), private organisations (eg, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation), banks (eg, the Asian Development Bank), public organisations (eg, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (Norad)), and civil society organisations (eg, Oxfam).

We also conducted 12 remote semi-structured interviews with experts on ESG reporting from the public sector, civil society, and the private sector. All quotes presented in this paper have been checked and approved by the interviewees and all of them gave their consent to being named.

This paper is structured as follows: we first introduce ESG reporting, presenting its scope and rationale. Next, we dig into ESG frameworks, including strengths and gaps in anti-corruption reporting, challenges in implementation, and opportunities for improvement. Third, we present good practices and entry points in sustainability reporting. Finally, we provide recommendations to development practitioners, standard setters, the private sector, governments, and civil society organisations.

ESG reporting: definitions, rationale and implications

Sustainability is an approach to ensure that today’s activities do not negatively affect future generations. For that purpose, specific criteria around environmental, social, and governance aspects have been defined to assess how organisations contribute to sustainability. ESG reporting originated as an evolution from corporate social responsibility (CSR), driven by growing demands from international organisations (eg, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the UN Global Compact) and regulatory bodies to integrate ESG considerations into corporate and investment practices.

ESG reporting has evolved over the past several years, with substantial changes in vocabulary and focus. The term 'sustainability' has experienced significant changes in its usage and meaning within the business sector. Initially, sustainability primarily referred to environmental concerns and resource conservation. However, it has expanded to encompass a broader range of issues, including social responsibility and governance practices. Europe and the USA differ in their approach to ESG and sustainability reporting, with Europe favouring ‘sustainability’ (eg, the European Union (EU) directive on corporate sustainability reporting ) and the USA emphasising ‘ESG’ (eg, the Security and Exchange Commission’s (SEC’s) climate disclosure rules). This reflects their distinct regulatory and cultural perspectives on corporate responsibility.

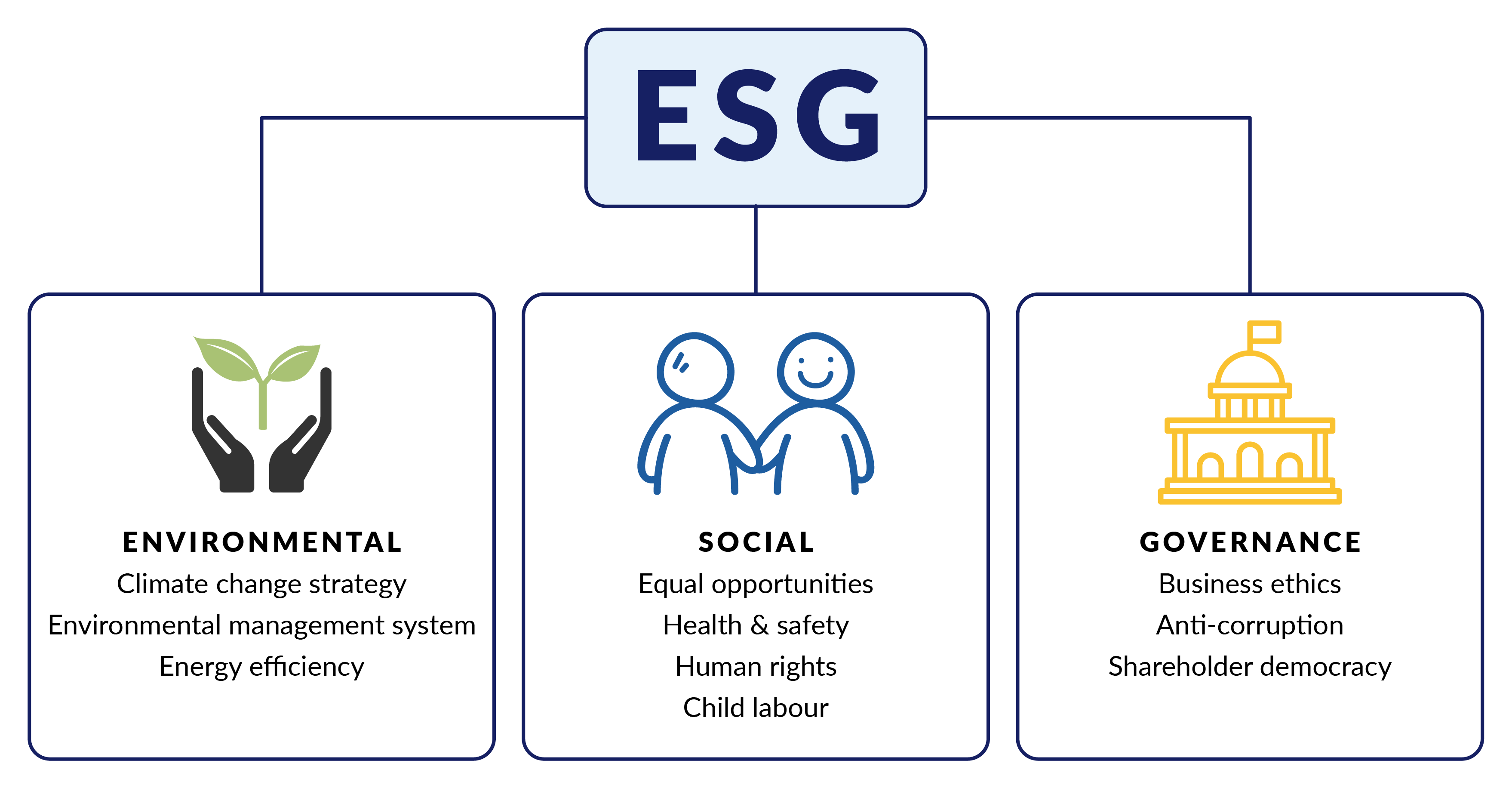

Figure 1: ESG criteria

Adapted from WorkPath.

Environmental, social, and governance reporting practices span a spectrum from voluntary disclosure to mandatory compliance, reflecting a diverse and fragmented landscape. In many countries outside the EU, ESG reporting remains voluntary, with no unified standards defining how organisations disclose their sustainability efforts. This has led to significant variability in practices and frameworks.

Two of the most prominent voluntary ESG frameworks are the United Nations Global Compact and the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI). The UN Global Compact provides a principles-based approach, outlining ten core commitments related to human rights, environmental protection, and anti-corruption. In contrast, the GRI offers a more granular system, featuring three types of standards: universal standards applicable to all organisations, sector-specific standards, and topical standards addressing issues such as anti-corruption. Emerging frameworks, such as B Corp, have further diversified the landscape, incorporating anti-corruption requirements alongside broader sustainability goals. While these frameworks provide valuable guidance, their diversity presents challenges for comparability and standardisation across organisations and jurisdictions.

In response to these challenges, the EU has taken a leading role in shaping ESG reporting by moving towards a regulatory framework. The Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), adopted as part of this broader push, mandates the standardisation of ESG disclosures across the EU. From 2025, nearly 50,000 large EU companiesb62cfdcc1a84 are required to align their reporting with the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). This regulatory shift introduces mandatory reporting and extends its influence to smaller enterprises through value chain requirements. As Piotr Bernacki observes, ‘Many SMEs [small and medium-sized enterprises] will be affected through the value chain of their larger business partners.’8d4c6322ba88 This will impact organisations within the EU but also outside the EU, through the ripple effect across supply chains.

The EU’s drafting of the ESRS reflects both the ambition and complexity of this regulatory transition. The following section explores the dynamics of this drafting process, offering insights into the competing interests and compromises that have shaped the final standards.

The EU Sustainability Reporting Standards drafting process

From 2022 to 2023, private association the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), endorsed by the European Commission, undertook the mission to draft the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS). The two-year drafting process involved extensive consultations with 475 stakeholders, including private enterprises and civil society organisations.

As the drafting process evolved, so did the structure of the standards. According to Pier Mario Barzaghi, EFRAG coordinator for the technical expert group for governance: ‘Business conduct (G2) became part of the mandatory general governance standard, while risk management and internal control (G1) became subject to materiality analysis.’fb92c1482789 As explained by Piotr Bernacki, EFRAG sustainability reporting technical expert, materiality – the assessment of significance or relevance – is a real issue: ‘for the materiality analysis, companies have the discretion to determine which aspects are material and are not required to report on every data point’.00b45c58cf35

Some stakeholders advocated for less strict standards and reduced reporting requirements. The end of a political cycle in the EU institutions coincided with the finalisation of the ESRS, increasing sensitivity to corporate wishes. For instance, President Ursula von der Leyen announced a plan to reduce reporting requirements on companies by 25%. Conversely, civil society tried to push for stricter requirements, as acknowledged by Carlota de Paula Coelho, senior policy manager at B Corp Spain: ‘There are a lot of data points missing, on managing supply chain, beneficial ownership, competition, etc. Half of the data points were cut. It was excruciating for us, the civil society.’379d69af10d3

EFRAG also experienced difficulties related to a shortage of money and overburdened staff, leading to inefficiencies. Nevertheless, the final version represents a workable consensus. According to de Paula Coelho, ‘When the first set of standards left EFRAG, I thought the Standard was not good enough. But when I saw the difficulties in getting it adopted by the legislators, I realised that EFRAG was more willing to go beyond than the EU Parliament and the Council and it would not have been useful to get something more ambitious because it would never have survived.’1d2f4a7564d0 Following public consultation, the ESRS were finally adopted in July 2023.

The drafting of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) shows that requirements are not based solely on evidence and relevance but are the result of inherent tensions between different interest groups. Corporate interests strongly influence the development of sustainability standards. However, differing perspectives emerged during the drafting, highlighting divergent views on the balance between the costs and benefits of sustainability reporting. For instance, our analysis of written comments from EFRAG participants shows that small enterprises (10 to 49 employees) presented reservations on business conduct, invoking complexity and costs, while medium-sized businesses (50–249 employees) were significantly more willing to report on formal governance and business conduct policies.

There is an intricate relationship between mandatory disclosure provisions and materiality assessments that companies must navigate to determine their reporting obligations. According to Bernacki, ‘Ensuring that companies accurately link their practices with their reports presents a significant challenge, particularly when they might argue the absence of materiality to justify non-disclosure.’6c58d8ab6a61 The qualitative nature of many provisions will make third-party verification more difficult and more subjective. For Carlota de Paula Coelho, ‘It is unlikely that auditors will have the capacity to meaningfully cross-check information.’f3505d65a8f6 This highlights the clash between regulatory intentions and the realities of feasible enforcement.

Nevertheless, the process also shows clear regulatory ambitions to enhance corporate transparency and accountability. This indicates a significant step forward in integrating ESG principles into the core governance frameworks of companies across Europe. We will now dig deeper into those anti-corruption requirements.

Anti-corruption requirements in ESG frameworks: an overview

As global attention to sustainable practices intensifies, anti-corruption becomes increasingly pivotal in ESG reporting. Sustainability reports are an easy way to gather information on partners, for instance, for due diligence checks or third-party assessments. Advanced technologies, such as artificial intelligence (AI), can even automate the monitoring of ESG data, detect anomalies, and provide predictive insights into potential risks. But how much emphasis is really placed on anti-corruption in these reports?

For Peter Paul Van de Wijs, chief external affairs officer for GRI, ‘Anti-corruption requirements related to voluntary disclosure can be stricter than mandatory requirements.’5af0b9ed3f7c For instance, the anti-corruption requirements outlined in the GRI 205 Standard focus on organisations reporting how they manage corruption-related risks. They include identifying and managing conflicts of interest, ensuring training on anti-corruption policies, participating in collective action to combat corruption, and disclosing confirmed incidents of corruption, along with the actions taken in response.

In the EU standard, several data points cover anti-corruption aspects. The framework requests organisations to provide information on the policies, procedures, and capacities for preventing, detecting, investigating, and responding to corruption and bribery. Accordingly, anti-corruption provisions cover prevention (eg, training, policies), detection (eg, whistleblowing systems), and remediation (eg, measures to address breaches, convictions, and fines). Moreover, the framework requires the disclosure of incidents, the number of convictions and fines, and measures taken to address breaches. We summarise these requirements in Annex 1.af45b9cee44e

In the USA, ESG reporting is primarily voluntary, and there is no clear standard for presenting data on anti-corruption topics. However, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires public companies and listed companies to disclose anti-corruption information in their periodic reports. This involves first, providing an assessment of internal controls over financial reporting and their effectiveness.e0fb3a227a51 Second, reports must disclose significant events, such as investigations, enforcement actions, or legal proceedings related to Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA) violations.42d72863b743 And, third, companies need to provide corporate governance details, including the board’s role in overseeing anti-corruption compliance programmes.

In the UK, neither the Bribery Act nor the Corporate Governance Code mandate specific disclosure requirements explicitly related to bribery and corruption. Yet, the Corporate Governance Code does require disclosures on a ‘comply or explain’ basis rather than as mandatory requirements. The 2006 Companies Act does not provide specific requirements related to anti-corruption. However, it does require a review of the company’s business, including the principal risks, governance arrangements, and statements from auditors about the company’s financial statements and internal controls. The UK government is currently updating its reporting requirements. It is expected that the UK will broadly adopt the International Sustainability Standards Board’s (ISSB) S1 and S2 standards in 2025, creating the UK Sustainability Reporting Standards (SRS). Further announcements are expected in the first quarter of 2025, with the first published sustainability reports anticipated for periods beginning on or after 1 January 2026.

In Hong Kong, listed companies on the Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited (HKEX) are required to report on anti-corruption aspects. In particular, the disclosure relates to anti-corruption policies, anti-corruption training for directors and staff, and risk management and internal control systems. There is no specific standard to follow.

In China, stock exchanges have announced new sustainability (ESG) reporting guidelines for listed companies. Yet, while governance aspects refer to risks (and may include corruption), there are no specific requirements related to anti-corruption.

India has introduced new ESG reporting requirements for the top 1,000 listed companies, mandating detailed disclosures under the Business Responsibility and Sustainability Report (BRSR) format. These requirements cover various sustainability aspects, including anti-corruption policies, training for board members, and awareness programmes for value chain partners. The aim is to enhance transparency, align with international standards, and support responsible business conduct.

Finally, in Malaysia, ESG reporting has been mandatory for all public listed companies since 2016, driven by various government and regulatory initiatives (eg, the Malaysian Code on Corporate Governance, the Sustainable and Responsible Investment Framework). The ESG Index Series, including the FTSE4 Good Bursa Malaysia Index, benchmarks companies’ ESG performance, including on anti-corruption and whistleblowing management, aligning with ISO 37001 Standard. Bursa Malaysia recently launched an ESG Reporting Platform, which aligns with the updated listing requirements from September 2022. Accessible at no extra cost via the Bursa LINK system, the platform enables listed companies to create a summary performance table for their sustainability statements, highlighting key indicators and data on their most significant sustainability issues.

This overview presents a diverse landscape of anti-corruption in ESG reporting, with varying requirements across regions. While progress has been made, significant gaps remain. The next section examines these limitations and their impact on effective anti-corruption practices.

Gaps and limitations in anti-corruption reporting requirements

Limited focus on anti-corruption in ESG standards

Experts at the French Anti-Corruption Agency note that anti-corruption data points represent around 1% of the global data points that companies must report on, which is not significant. Moreover, Catherine Ferriol, head of the business support department at the French Anti-Corruption Agency (AFA), states, ‘Organisations already have to comply with anti-corruption laws, such as Sapin II in France, so the only novelty is the need to be transparent about this fulfilment with the law.’3ee45b474d36

These observations are confirmed by the 2023 Carrot & Stick report. Scrutinising 2,463 policies from 133 countries, the authors found that only 1.3% of all standards required anti-corruption aspects. However, 40% of standards included a general disclosure on the organisational profile, including ethics, integrity, governance, reporting practices, and stakeholder engagement. According to a 2023 report from the International Federation of Accountants and Transparency International UK, almost all the largest listed companies disclose some information about anti-corruption policies and training, but only just over a third disclose corruption incidents (37%) and very few report the costs of corruption (4%).

Insufficient attention to cross-cutting and salient anti-corruption issues

Even when anti-corruption is included, ESG frameworks have no or weak provisions on several cross-cutting or salient anti-corruption issues. For instance, the ESRS framework has no dedicated section or disclosure requirement specifically focused on conflict-of-interest disclosure and management. This is also only indirectly covered in other sections, such as corporate culture or anti-corruption policy, despite being an important risk of corruption in large private organisations. Similarly, the notion of gender is not referenced in the standard, even though it influences corruption activities (eg, sexual corruption) and anti-corruption activities (eg, whistleblower protection mechanisms).

It is noteworthy that the draft ESRS included a requirement on beneficial ownership, but the final standards excluded it. This provision sought to disclose the identity of ultimate beneficial owners or those in control of the company, along with their respective ownership or control percentages. Regulators and stakeholders lose a key tool for holding companies accountable for anti-corruption efforts due to this removal.

Emphasis on process rather than outcome and impact

Another clear limitation is that most data points focus primarily on internal management processes, rather than on outcomes and impact. For instance, a description of anti-corruption and anti-bribery training provides no insights into participants’ knowledge, skills, or perspectives on corruption and anti-corruption. As de Paula Coelho notes, ‘It is uncertain whether these minimum requirements will define new behaviours or have any impact. It is all about disclosure, not real change, as it prescribes transparency rather than behaviour. On the other hand, I think companies, by setting up data collection mechanisms and tracking sustainability metrics, will become more sensitised to managing these impacts. The standards are imperfect, but the theory of change is not bad.’edc8de2ff038

Similarly, Maud Vignoux, who oversees support to economic actors at Agence Française Anti-Corruption (AFA), explains, ‘Companies subject to the Sapin II law could perceive anti-corruption data points as non-significant in the context of broader sustainability obligations. However, these companies are concerned about the obligation to communicate on anti-corruption matters, including on non-definitive sanctions, as it could damage their reputation.’5599f1729f5f This could encourage organisations to proactively strengthen their anti-corruption measures.

Data quality and reliability

The quality and reliability of ESG data remain challenging. As Vladimir Hrle, international financial corporation expert observes, ‘Every company will say that they care about anti-corruption efforts, but in our experience very few will reveal whether they experienced any issues related to fraud and corruption, especially on legal actions involving the company.’d55f33535265 Non-compliance in reporting often stems from the absence of necessary governance practices: ‘One of the reasons is that companies do not have relevant practices, so they cannot report on those practices.’6b156ffcd632

In fact, companies often lack robust systems for collecting and verifying ESG-related information, leading to incomplete or inconsistent data. The siloed nature of data across different departments and systems within organisations further complicates the collection process, potentially resulting in inaccuracies and gaps in reporting. To add to this, the fragmented landscape of ESG reporting, where different standards impose varying requirements, presents significant challenges in achieving comparability across disclosures. This inconsistency can enable companies to circumvent anti-corruption disclosures by deeming corruption as an immaterial topic.

This fragmented landscape and its loopholes underscore the need for improvements in ESG reporting standards. The next section explores some entry points for enhancing these frameworks to ensure more consistent, actionable, and impactful anti-corruption disclosures.

Entry points for improving standards

The analysis of current anti-corruption requirements in ESG frameworks highlights several areas where targeted improvements could enhance their effectiveness and impact. Strengthening these standards involves addressing both structural weaknesses and expanding the scope of disclosures to ensure organisations are held accountable for their anti-corruption efforts.

Broadening anti-corruption data points

Expanding anti-corruption data points can support companies in developing trust. Frameworks should include additional metrics on conflict-of-interest policies, beneficial ownership, and anti-financial crime compliance. These disclosures would allow regulators and stakeholders to better evaluate the robustness of organisational anti-corruption measures.

Shifting focus to impact-based metrics

Most existing standards prioritise internal processes. Frameworks should incorporate impact-based metrics that assess the outcomes of anti-corruption measures, such as changes in employee awareness and behaviour. This would shift the focus from mere compliance to meaningful change.

Incorporating gender dimensions

The lack of gender-specific considerations in ESG frameworks, such as addressing issues like sexual corruption or ensuring whistleblower protection mechanisms, represents a missed opportunity to strengthen anti-corruption efforts. Integrating gender-sensitive requirements would not only address risks but also foster more inclusive anti-corruption strategies.

Adopting stronger regulatory mandates

Regions where anti-corruption disclosures remain voluntary, such as the USA and China, could benefit from adopting more stringent requirements. Drawing lessons from robust frameworks, such as the EU’s ESRS, could help establish clearer expectations and close existing gaps.

By addressing these entry points, ESG frameworks have the potential to achieve meaningful progress in anti-corruption efforts, advancing sustainability and ethical governance. Building on these strategies, valuable insights can be gained from the development aid sector, where reporting practices are designed to meet high standards of accountability and transparency. The next section examines these good practices, offering lessons to enhance ESG reporting.

Good practice examples for ESG reporting that can enhance anti-corruption, transparency and accountability

Transparency in communicating on organisational integrity

A first observation is that ESG reporting in the aid sector is not yet a common practice. Only a quarter of the organisations we assessed provide ESG reports. This is understandable, as not all donor countries have mandatory reporting practices (eg Canada, Australia). However, development cooperation organisations often report anti-corruption activities in their financial or activity reports. In total, only 12% (6 of the 50 organisations we checked) did not provide any information on their anti-corruption activities.

These reports share several commonalities, including a strong emphasis on governance, transparency, training, and preventive measures. They collectively demonstrate a commitment to upholding ethical standards and addressing corruption through comprehensive policies and procedures.

Some organisations go further. We chose to emphasise three of these to reflect on best practices, as the three offer different focuses. Our selection criteria were based on comprehensiveness and level of detail, transparency and accountability in activities, and emphasis on impact and outcomes.

Anti-corruption disclosure in USAID’s annual report 2023

The 2023 USAID annual report presents information on its anti-corruption framework, which includes detailed policies and procedures to prevent and respond to allegations of corruption. For instance, it provides specific metrics showing a 25% reduction in corruption incidents, attributed to enhanced internal controls and oversight mechanisms.

The report details specific cases of violations, the nature of incidents, investigation processes, and the outcomes. For instance, an alleged diversion of food aid in Ethiopia led to the identification of multiple fraud schemes, including corruption in beneficiary selection and exploitation by vendors purchasing food from beneficiaries. Beneficiaries were also coerced into giving a portion of their aid to local officials and armed groups. The report highlighted control shortcomings as well as recommendations, including the need for a centralised tracking system for allegations and the delegation of clear roles and responsibilities for responding to such allegations.

The report places a strong emphasis on transparency and the implementation of detailed administrative actions and safeguarding procedures. These include stricter financial controls, enhanced audit procedures, training, and the creation of an anti-corruption centre.

Finally, the report emphasises how USAID engages with a wide range of stakeholders, including programme participants and the US government, to enhance its anti-corruption measures and ensure stakeholder trust.

The USAID annual report effectively communicates its anti-corruption framework through clear and accessible language, making the information understandable for a broad audience. By addressing critical anti-corruption data points, including ethical practices, reporting mechanisms, safeguarding procedures, and incident disclosure, the report demonstrates a comprehensive approach to combating corruption.

The detailed presentation of specific cases underscores USAID’s commitment to transparency and accountability. It also highlights the limits, challenges, and impact of USAID’s anti-corruption measures. The emphasis on detailed administrative actions, such as stricter financial controls, further illustrates USAID’s proactive measures to prevent and address corruption. Finally, the inclusion of metrics provides insight on the effectiveness of these measures.

Overall, the USAID annual report 2023 demonstrates a comprehensive approach to governance within ESG reporting, particularly in its handling of anti-corruption disclosures. This comprehensive approach can reinforce stakeholder trust.

Anti-corruption activities at the Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida)

Sida provides a specific annual report on its ‘handling of suspicions of corruption and irregularities’. The detailed document offers a comprehensive overview of the agency’s efforts to combat corruption in the context of international development cooperation.

A significant portion of the report is dedicated to case management, with data on cases of suspected corruption or irregularities, as well as assessments of trends by year, type of irregularity, geographic distribution, and detection methods. For instance, in 2021, Sida registered 303 new cases of suspected corruption or irregularities, a slight decrease from the 326 cases registered in 2020. Most cases were detected through reports from Sida’s partner organisations (77%), followed by whistleblowers (12%), audits, and regular follow-up activities. Geographically, Africa accounted for 54% of the reported cases, with significant numbers also arising in Afghanistan and Syria.

Sida also provides information about its investigation processes and results. For instance, in 2021, Sida closed 374 cases, which confirmed suspicions of corruption or irregularities in 228 cases (61% of the closed cases). To address these confirmed cases, Sida imposed various sanctions, including repayment requests (110 cases), training measures (71 cases), and dismissals (55 cases). Legal action was taken in about one in ten confirmed cases.

Finally, Sida highlights its collaboration with partner organisations, which is crucial to its anti-corruption strategy.

As presented above, Sida provides a thorough and transparent account of the agency’s anti-corruption activities. Like USAID’s report, Sida's ESG reporting reflects a detailed approach to managing and investigating corruption. Its report includes data on trends, geographic distribution, and detection methods. This may indicate a strong focus on oversight and transparency, as well as an awareness and use of reporting mechanisms among partner organisations.

The report highlights the agency’s ongoing efforts to strengthen procedures, manage corruption risks effectively, and promote a culture of integrity and accountability in development cooperation. Moreover, the emphasis on collaboration with partner organisations as a cornerstone of its anti-corruption strategy indicates a holistic approach to fostering integrity within the broader development community.

Anti-corruption at the African Development Bank (AFDB)

Through its Office of Integrity and Anti-Corruption (PIAC), the AFDB reports on how integrity is managed within the Bank and its operations. It presents the organisational structure and resources used to enforce PIAC’s anti-corruption prevention and investigation mandate.

The report emphasises its activities to strengthen its framework for identifying, preventing, and addressing potential integrity risks. This was achieved through the implementation of the Strategic ‘3Ps’: People, Policies, and Partnerships. For instance, the AFDB highlights its role at the International Anti-Corruption Conference (IACC) and its partnerships with other multilateral development banks.

The report also provides detailed information about cases and their management, disaggregating data by sector, region, type of irregularities, etc. Additionally, it gives details on staff misconduct investigations, disaggregating data by gender distribution of complainants, gender distribution of subjects of investigation, duty station (eg, headquarters, HQ), duration of employment, etc., as well as remedial actions (eg, dismissal, warnings).

The AFDB report provides a thorough and transparent account of how integrity is managed within the Bank and its operations. Its ‘3Ps’ strategy, around People, Policies, and Partnerships is particularly relevant.

Attention to gender equality

The report’s detailed information on case management, particularly the disaggregation of data by gender, duty station, and type of irregularities, underscores the Bank’s commitment to transparency and accountability. This level of detail not only allows the leadership to take informed and necessary actions, but also fosters a culture of integrity within the organisation. The disaggregation of data by gender and duty station is particularly relevant as it provides the opportunity to tackle drivers of corruption in relation to power dynamics and work environment.

Many development cooperation organisations place particular emphasis on gender equality. For instance, the management boards of GIZ (Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit, the German Corporation for International Cooperation), the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO), and USAID’s leadership teams include gender parity. To some extent, gender considerations are also integrated into ESG reporting practices within the development cooperation sector. However, other aspects of diversity, such as ethnicity and disability, remain largely unaddressed by these organisations in relation to anti-corruption and sustainability reporting.

Enhancing ESG reporting through collective action

By fostering a culture of mutual accountability and setting common standards, organisations within specific industries and value chains are encouraged to promote enhanced sustainability practices within a more trusted business environment. As noted by Lucie Binder at the Basel Institute on Governance, ‘The idea behind anti-corruption collective action is that we can level the playing field if we bring different players together with the same focus.’4d1e8a99b96b

According to this perspective, a group of organisations can align policies and procedures by considering the reporting requirements of ESG frameworks and incorporating them into their existing anti-corruption practices. This may involve assessing their current policies and procedures, identifying gaps in relation to ESG reporting requirements, and making necessary adjustments to ensure compliance. This can also be resource efficient, as collective action allows organisations, especially smaller ones, to pool resources and share expertise.

The collective action against corruption in Thailand, developed in the box below, presents a compelling approach, demonstrating the mutual benefits for both large and small companies to engage collectively in anti-corruption reporting.

Collective action against corruption in Thailand

Since 2010, the Thai Collective Action Against Corruption (Thai CAC) has aimed to reduce corruption by raising standards at the company and sector levels. Companies participating in this initiative pledge to disclose their internal policies. Thai CAC provides certification to those that have been externally verified and comply with the CAC standards.

Thai CAC has pledged to gather 1,000 signatories and over 400 certified companies, including Thai commercial banks and pharmaceutical companies. According to Vanessa Hans at the Basel Institute on Governance, ‘Companies can engage in collective action initiatives to ensure that their anti-corruption practices are made more effective and consistent with those of their supply chain partners – and are also more consistently reported in ESG disclosures.’9da976170236

The idea is that ‘change agent companies’ will invite subcontractors and business partners to take part in the initiative to promote a transparent and sustainable business environment. Training and support are provided to SMEs to help them understand and fulfil the anti-corruption requirements of the multinationals.

In addition to certification and training, this collective action also relies on enhancing business reputation (eg, delivering gold badges), social pressures, multi-stakeholder dialogues, and the development of trust relationships across companies to leverage anti-corruption.

The CAC is a 100% privately funded organisation, with local and international sponsors, including the Center for International Private Enterprise (CIPE) in particular.

This case study demonstrates the potential of collective action in enhancing ESG reporting. By encouraging companies to disclose internal policies and undergo external verification, the initiative elevates anti-corruption standards and promotes transparency and accountability in sectors. Collaboration among private sector companies and their supply chain partners can ensure consistent anti-corruption practices in ESG disclosures, enhancing report credibility.

‘Change agent companies’ can be pivotal to fostering integrity throughout the supply chain. Providing training and support can help smaller companies fulfil anti-corruption requirements. Certification, reputation enhancement, social pressures, and multi-stakeholder dialogues are insightful tools to build trust and encourage participation, creating a sustainable and transparent business environment.

As the final step in our journey on good practices for ESG reporting, the following box features another type of collective action, with a Swiss development initiative involved to support sustainability reporting and improve the business environment.

Using progression matrices to assess practices in the financial sector

The Integrated ESG programme, financed by the Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO) and implemented by the International Finance Corporation (IFC, World Bank Group), collaborates with financial institutions, governmental agencies, and the private sector to promote sustainable investment in various countries (Colombia, Egypt, Ghana, Serbia, etc.).

Its aim is to integrate ESG factors into capital allocation to improve financial sector efficiency and access to investment and markets. According to Christian Braendli, deputy head of private sector development at SECO, ‘Better ESG practices are closely linked to improved organisational performance, greater access to capital, and development outcomes. Governance, as the foundation of ESG, plays a pivotal role by aligning environmental and social considerations with a company’s strategy, culture, and operations.’52ccf15013c7

The IFC uses progression matrices to assess and guide companies’ governance practices. As IFC’s Caroline H Bright observes, ‘The matrix is about improving practices, not about reporting indicators. We want to see that a company has a board of directors, annual shareholders meetings, and proper procedures for managing risks.’fff3b9f459c1 The matrix categorises practices into minimum, basic, intermediate, and advanced levels, helping companies understand where they stand and how they can improve.

While the IFC supports ethical standards and control systems, it also comes with challenges: ‘In developing markets, there are fewer external incentives for organisations to introduce good governance, especially when you get further and further away from the EU, and many companies do not yet understand the benefits it can bring,’ Bright notes.b81066b37eae

In Serbia, the new EU directive is viewed as a potential catalyst for companies to establish essential ESG policies. According to Hrle, ‘The new ESG reporting directive could motivate companies to implement relevant ESG policies, including anti-corruption and bribery.’56d1f2eae8f6 Although Serbia is not an EU member, Serbian companies involved in EU value chains will need to comply with EU regulations to remain competitive.

As presented above, these progression matrices provide a structured approach to evaluating and improving governance practices. By categorising practices into different levels – minimum, basic, intermediate, and advanced – the IFC helps companies to self-assess and understand their current standing and the steps needed for improvement. This method can ensure that companies not only comply with regulations superficially, but also develop robust governance frameworks over time. This can be not only beneficial for individual companies, but may also contribute to broader development outcomes, suggesting a positive ripple effect at the sector level.

Yet, the case study also highlights the difficulty in obtaining transparent information from companies about their anti-corruption efforts. This suggests that while significant strides are being made to integrate ESG standards, challenges remain in ensuring transparent governance and incentivising companies – particularly in developing markets. ESG reporting alone is not sufficient to solve corruption issues in varying business environments.

It is also crucial to maintain a critical perspective on such initiatives. Our analysis of various multi-stakeholder partnerships for integrity revealed challenges in monitoring and enforcement. In a horizontal power structure led by the private sector, members often lack both the capacity and willingness to monitor one another. Conversely, in a vertical, government-led structure, over-reliance on the public sector can hinder long-term involvement and discourage collaboration from other partners, particularly civil society and the private sector.

Conclusions

The intersection of environmental, social, and governance reporting and anti-corruption measures represents a pivotal development in corporate governance. Our analysis reveals that while ESG reporting is gaining momentum globally, the integration of anti-corruption provisions remains limited and inconsistent. Anti-corruption requirements represent only 1% of all ESG data points, despite the critical role these measures play in promoting transparency and integrity.

The European Union’s efforts to enhance corporate sustainability reporting through the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD) illustrate both the potential and challenges of implementing comprehensive ESG standards. The drafting process of the European Sustainability Reporting Standards (ESRS) revealed significant stakeholder tensions, reflecting the complexity of balancing corporate interests, regulatory intentions, and practical enforcement capabilities. Despite these challenges, the ESRS marks a significant step towards greater corporate accountability and transparency.

However, the effectiveness of ESG reporting in reducing corruption remains inconclusive. While there is evidence to suggest that robust anti-corruption measures within ESG frameworks can enhance governance and indirectly reduce corruption, the implementation and enforcement of these measures are fraught with challenges. The disparity in global reporting standards, the influence of corporate interests, and the practical difficulties of auditing and verifying reported data all contribute to this uncertainty. Furthermore, the focus on structural compliance over behavioural change increases the risk of ESG reporting becoming a box-ticking exercise rather than promoting genuine reform. Given its reliance on data quality and availability, AI is unlikely to alter this dynamic.

Nevertheless, exemplary practices by organisations like USAID, Sida, and the African Development Bank demonstrate the value of detailed, transparent reporting in fostering a culture of integrity and accountability. Sector-level collective actions, for instance, along supply chains, also hold promise in advancing ESG reporting and anti-corruption efforts. Keeping in mind that proper conditions are needed to ensure effective governance and oversight mechanisms, these partnerships offer opportunities for setting and raising sector-specific standards, facilitating knowledge sharing, and enhancing the integrity and sustainability of business practices. Setting up data collection mechanisms and tracking sustainability metrics, such as the IFC progression matrices, can develop capacities to better manage corruption risks.

Our research highlights the need for a more integrated approach to ESG and anti-corruption reporting. While current standards and practices provide a foundation, there is a need for enforceable frameworks that address both the qualitative and quantitative aspects of governance, focusing not only on policies and processes but also on practices. The inclusion of diverse perspectives, including in terms of gender and inclusivity but also work environment, and the alignment of reporting practices across sectors and regions, are crucial for achieving meaningful progress.

In conclusion, the integration of anti-corruption measures within ESG reporting frameworks holds significant promise for enhancing corporate governance and sustainability. However, realising this potential involves addressing the inherent challenges of regulatory enforcement and alignment across jurisdictions. As the global focus on sustainable development intensifies, the continued evolution of ESG reporting standards can play a pivotal role in driving the transparency and accountability needed to combat corruption and promote ethical business practices.

Recommendations

To standard setters:

- Incorporate anti-corruption measures into ESG reporting regulations, including disclosures on systems for corruption prevention and detection, corruption incidents, beneficial ownership, and lobbying.

- Provide clear guidance on assessments to prevent companies from excluding corruption as immaterial. For instance, specify the inclusion of corruption risk assessment tools that evaluate both financial materiality and stakeholder materiality, ensuring corruption is considered within all relevant contexts. When issues are not deemed material, companies should be required to provide a clear rationale for this conclusion.

- Ensure reasonable assurance as part of ESG reporting to prevent misrepresentation and mitigate risks of greenwashing and reputation laundering.

To development practitioners:

- Advocate for comprehensive regulatory frameworks that address both the qualitative and quantitative aspects of governance, focusing not only on policies and processes but also on practices such as capacity-building initiatives, or collaboration with governments on regulatory frameworks.

- Promote accountability in your organisation by backing sustainability reporting on integrity and anti-corruption aspects. This could be, for instance, via conducting internal audits on anti-corruption practices, the use of third-party verification for ESG reports, or through the creation of dedicated anti-corruption teams.

- Support sector-wide collective initiatives for anti-corruption disclosure as a way to raise integrity standards, facilitate knowledge sharing, and improve business practices.

To private companies:

- Invest in robust anti-corruption and integrity practices to comply with emerging ESG regulations.

- Disclose sustainability information transparently, including specific details on anti-corruption practices, risk assessments, and mitigation strategies. Ensure that these disclosures are easily accessible and understandable to all stakeholders, including investors, regulators, and the public.

- Engage in multi-stakeholder collective action initiatives to address complex sustainability challenges.

To governments:

- Mandate ESG reporting as a legal requirement and incorporate anti-corruption measures.

- Strengthen enforcement mechanisms and ensure that penalties for non-compliance are substantial enough to deter violations.

- Make ESG information accessible through centralised open access platforms.

- Encourage multi-stakeholder collective action initiatives to strengthen ESG practices.

To civil society organisations:

- Promote anti-corruption as central to ESG reporting. Strengthen advocacy efforts to highlight the critical role of anti-corruption measures within ESG frameworks, ensuring this message reaches decision makers and the public alike. Key players like Transparency International and Global Witness can ‘lead the charge’ in shaping this narrative.

- Push for greater transparency. Advocate for the publication of policy-relevant data and information that support public scrutiny and accountability. Organisations such as Open Data Charter could be instrumental in this area.

- Undertake independent monitoring. Develop and disseminate reports on sustainability practices to provide an unbiased assessment of companies’ adherence to ESG commitments. Partnerships with networks like Accountability Lab or Publish What You Pay can enhance the credibility and reach of these efforts.

- Engage in multi-stakeholder initiatives. Actively participate in collaborative forums such as the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) or the Open Government Partnership (OGP) to drive improvements in ESG practices and foster collective action.

Annex 1: Governance aspects in the European Sustainability Reporting Standards

Governance aspects in the European Sustainability Reporting Standards

|

ESRS governance aspects |

Data points |

|

Business conduct policies and corporate culture |

|

|

Management of relationships with suppliers |

|

|

Prevention and detection of corruption and bribery |

|

|

Incidents of corruption or bribery |

|

|

Political influence and lobbying activities |

|

|

Payment practices |

|

- See, for instance, recent legal investigations related to ESG matters, such as the ones against Goldman Sachs,BNY Mellon or Deutsche Bank.

- Bernacki, P., EFRAG sustainability reporting technical expert; president, Polish Association of Listed Companies. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- The measure concerns large EU companies with more than 250 employees and more than 40 million EUR in net turnover.

- de Paula Coelho, C., senior policy manager, B Corp Spain. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- Bernacki, P., EFRAG sustainability reporting technical expert; president, Polish Association of Listed Companies. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- Van de Wijs, P.P., chief external affairs officer for the Global Reporting Initiative. Interviewed by 12 August 2024.

- For an in-depth summary of ESRS G1, please refer to: ESG and anti-corruption.

- SEC Regulation S-K Rules, Item 103.

- Federal Register. 2003. Management’s report on internal control over financial reporting and certification of disclosure in exchange act periodic reports, 18 June.

- Ferriol, C., head of the business support department, Agence Française Anti-Corruption. Interviewed 30 November 2023.

- de Paula Coelho, C., senior policy manager, B Corp Spain. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- Vignaux, M., oversees support to economic actors, Agence Française Anti-Corruption. Interviewed 30 November 2023.

- Hrle, V., IFC expert, World Bank Group. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- Hrle, V., IFC expert, World Bank Group. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- Binder, L., senior specialist, governance and integrity, Basel Institute on Governance. Interviewed 23 June 2023.

- Bernacki, P., EFRAG sustainability reporting technical expert; president, Polish Association of Listed Companies. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- Barzaghi, P.M., EFRAG coordinator for the technical expert group for governance; partner, KPMG Italy. Interviewed 31 October 2023.

- de Paula Coelho, C., senior policy manager, B Corp Spain. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- de Paula Coelho, C., senior policy manager, B Corp Spain. Interviewed 21 November 2023.

- Hans, V., head, private sector, Basel Institute on Governance. Interviewed by Name, 23 June 2023.

- Braendli, C., deputy head, private sector development, Swiss State Secretariat for Economic Affairs (SECO), SECO Economic Cooperation and Development. Interviewed 29 September 2023.

- Bright, C.H., regional ESG advisory lead for Europe, Central Asia, Middle East and Pakistan, International Finance Corporation. Interviewed 13 October 2023.

- Bright, C.H., regional ESG advisory lead for Europe, Central Asia, Middle East and Pakistan, International Finance Corporation. Interviewed 13 October 2023.

- Hrle, V., IFC expert, World Bank Group. Interviewed 21 November 2023.