Query

Please provide an overview of the nature of corruption in sub-Saharan Africa, with a particular focus on state capture and fragility, as well as the anti-corruption activities of relevant regional organisations.

Caveat

This paper contains discussions on countries such as Somalia and Sudan, which may be regarded as outside the sub-Saharan Africa region. The United Nations Development Programme excludes both countries from its list (UNDP 2020), whereas the World Bank lists both countries as part of sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank 2018a). The African Union refrains from using such classification and its anti-corruption measures and initiatives cover the whole continent. Somalia and Sudan are priority countries for the enquirer, and therefore have been included in this Helpdesk Answer.

Overview of corruption in sub-Saharan Africa

Background

Sub-Saharan Africa consists of countries found to the south of the Sahara desert. The World Bank statistics from 2018 recorded a total population of 1.078 billion citizens, making it the second largest population region in the world (World Bank 2018a).

The history of sub-Saharan Africa, particularly of the 19th and 20th century, is characterised chiefly by European colonialism, whereby white minority governments controlled the economic and political affairs in most countries. The 20th century witnessed armed struggles and violent confrontations as black majority parties and groups fought for their independence from colonial governments.

Colonialism plundered the continent while stifling local political and economic development, and left behind a legacy with ramifications for the present, as reflected in the patterns of contemporary globalisation (Ocheni and Nwankwo 2012; Heldring and Robinson 2013; Frankema 2015).

Across the continent, many countries have made significant strides in the social, political and economic spheres since the turn of the millennium, although some of these successes have yet to be firmly consolidated.

South Sudan is a good example of this mix of promise and volatility. The country became the youngest state in the world in 2011 after 98.83% of people voted in a referendum to separate from Sudan to form an independent state, the culmination of a peace process that had ended Africa’s longest civil war in 2005 (Kron and Gettleman 2011). While the country has since experienced cycles of violence and the recurrence of civil war, a new peace agreement was signed in 2018 to introduce a power sharing government, and the opposition leader Riek Machar was sworn in vice president in February 2020 (Quarcoo 2020).

In the last few years, citizens in some African countries have taken to the streets to demand change, which has resulted in the removal of long-term leaders from power. In Burkina Faso, citizens protested against plans by the former president, Blaise Compaoré, to extend his 27 years in office, compelling his resignation in 2014 (Hinshaw and Villars 2014). Former president Yahya Jammeh was forced to end his 22-year rule in the Gambia in 2017 after losing elections to the new president, Adama Barrow (Maclean 2017). In 2019, the former president of Sudan, Omar al-Bashir, was removed from office by the military in 2019 after 30 years in power. With the army taking control over the transition of power, citizens protested in the streets to demand a civilian government, leading to the appointment of Abdalla Hamdok as leader of the transitional government (Awadalla 2019). Facing multiple charges of crimes committed during his presidency, al-Bashir was recently convicted and sentenced to two years imprisonment for corruption (Abdelaziz 2019).

Another step forward is the desire by African leaders to end war and violence on the continent. The current theme for the African Union is focused on the campaign “Silencing the Guns by 2020: Towards a Peaceful and Secure Africa”. The campaign is aimed at achieving an Africa free of wars, violent conflicts and human rights violations (African Union 2019a).

African countries have likewise demonstrated commitments to work together towards shared prosperity. The African Union’sAgenda 2063: The Africa We Want is a blueprint for political, social and economic transformation on the continent (African Union Commission 2015). It sets out Africa’s aspirations on key issues, such as inclusive growth and development, regional integration, good governance, human rights and a peaceful and secure Africa (African Union Commission, 2015: 2). In addition, African countries are involved in the United Nations 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The United Nations Secretary-General’s Special Advisor to Africa has argued that Agenda 2063 is mutually supportive and coherent with the SDGs and that some differences do not affect the simultaneous implementation of both agendas (Kuwonu 2015).

Another notable achievement is the Agreement Establishing the African Continental Free Trade Area, which entered into force in 2019. The trade agreement is aimed at expediting intracontinental trade, enhancing regional integration and invigorating African countries’ position in global trade. Once ratified by all countries, it will cover a market of approximately 1.2 billion people and a GDP of US$2.5 trillion, making it the second largest trade agreement after the World Trade Organisation (Abrego et al. 2019).

Nonetheless, corruption is a major challenge to these economic, social and political developments in sub-Saharan Africa. Its impact differs across various types of political systems in the region. In democratic states, it undermines state institutions and oversight bodies responsible for checks and balances on the use of power (Pring and Vrushi 2018). In weak democracies and autocratic regimes, it delays democracy as corrupt leaders use dirty methods to overstay in power and escape liability (Pring and Vrushi 2018). Such tactics included the rigging of elections and amendment of laws to the extent of terms in office. What is more, where state institutions are politically captured, they can become repressive tools for the corrupt elite. Corruption in fragile or conflict-affected states impedes peacebuilding efforts and contributes to renewed cycles of violence (Le Billon 2008).

Corruption is one of the major barriers to economic growth in the region and, as pointed out by Sabrino and Thakoor (2019), it behaves “more like sand than oil in the economic engine”. Corruption worsens poverty and aggravates inequality as resources meant for the poor and the underprivileged are diverted to line the pockets of the corrupt (Addah et al. 2012). Moreover, it compromises future generations by depriving resources for the development of children and young people. A report by the African Union pointed out that corruption has “stolen futures” in Africa, detailing how at least 25 million children in primary schools alone are victims of corruption (African Union 2019b: 12).

According to a report by the International Money Fund, sub-Saharan Africa will benefit more economically from mitigating corruption than any other region (Hammadi et al. 2019: 6). The report indicated that if governance in the region, which is comparatively poor, is brought to the world average, there could be an increased GDP per capita of about 1% to 2% per year. Hence, stronger governance and reduced corruption are key elements towards the achievement of desired development in sub-Saharan Africa.

Extent of corruption

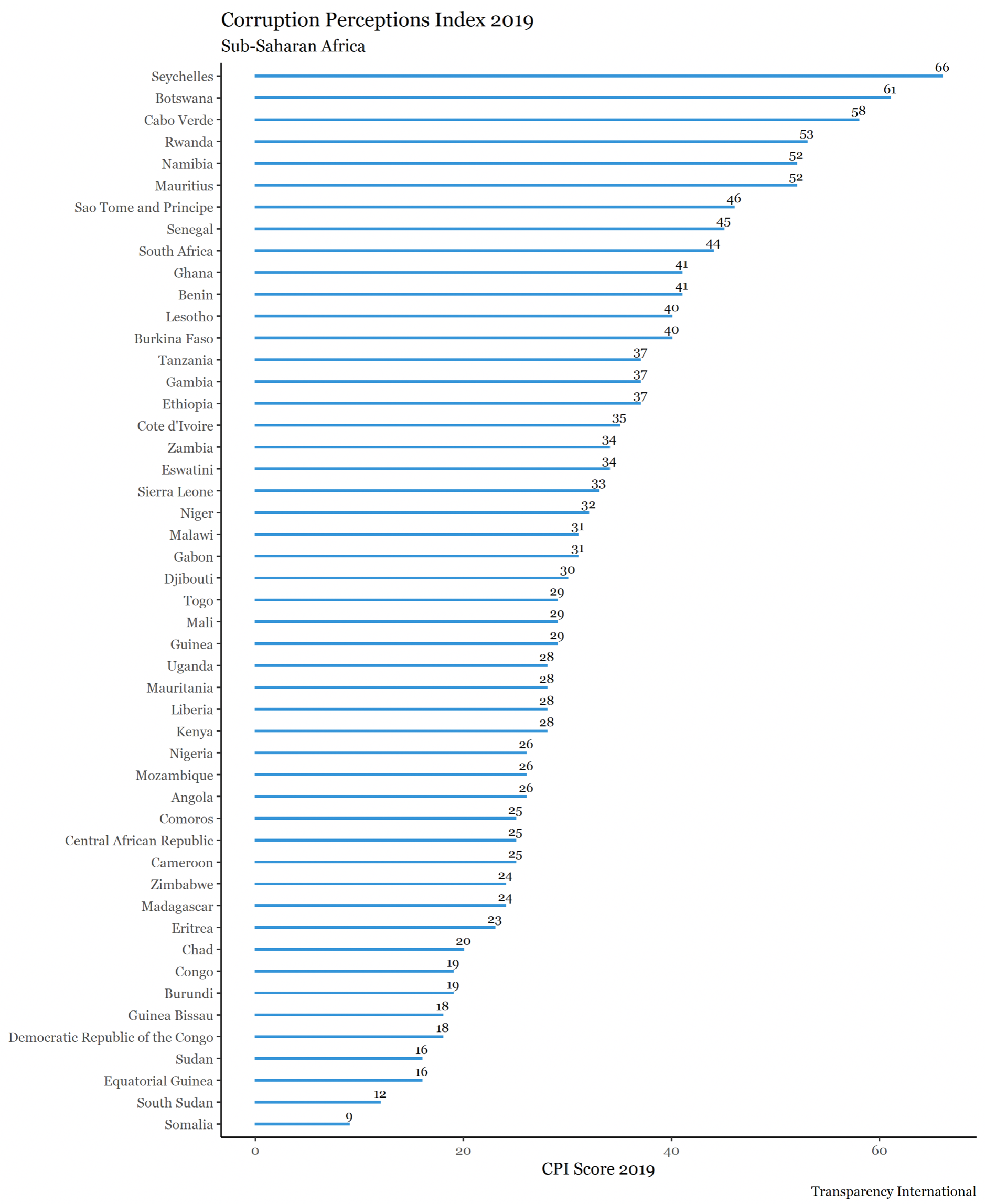

Sub-Saharan Africa was the lowest ranking region on the 2019 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), with a regional average score of 32 out of 100 (Transparency International, 2020). The global average score is 43, and the African average indicates how corrupt the public sector across the region is perceived to be. The diagram below shows how countries in sub-Saharan Africa scored on the 2019 CPI, with 0 denoting the most corrupt and 100 the least corrupt.

Corruption Perceptions Index 2019

The five least corrupt countries in the region are Seychelles, Botswana, Cape Verde, Rwanda and Namibia. There is a correlation between CPI scores and other corruption-related indices. For instance, the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI), a World Bank research tool which captures key themes of governance, gives percentile scores for control of corruption (World Bank 2018b). According to the 2018 indicators, Seychelles scored 75. 96, Botswana (77.88), Cape Verde (78.37), Rwanda (71.15) and Namibia (65.38). These countries are performing well on both indices. Comparatively, Sudan (5.77), Equatorial Guinea (2.40), Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (3.85), South Sudan (0.48) and Somalia (0.00) are performing badly on controlling corruption.

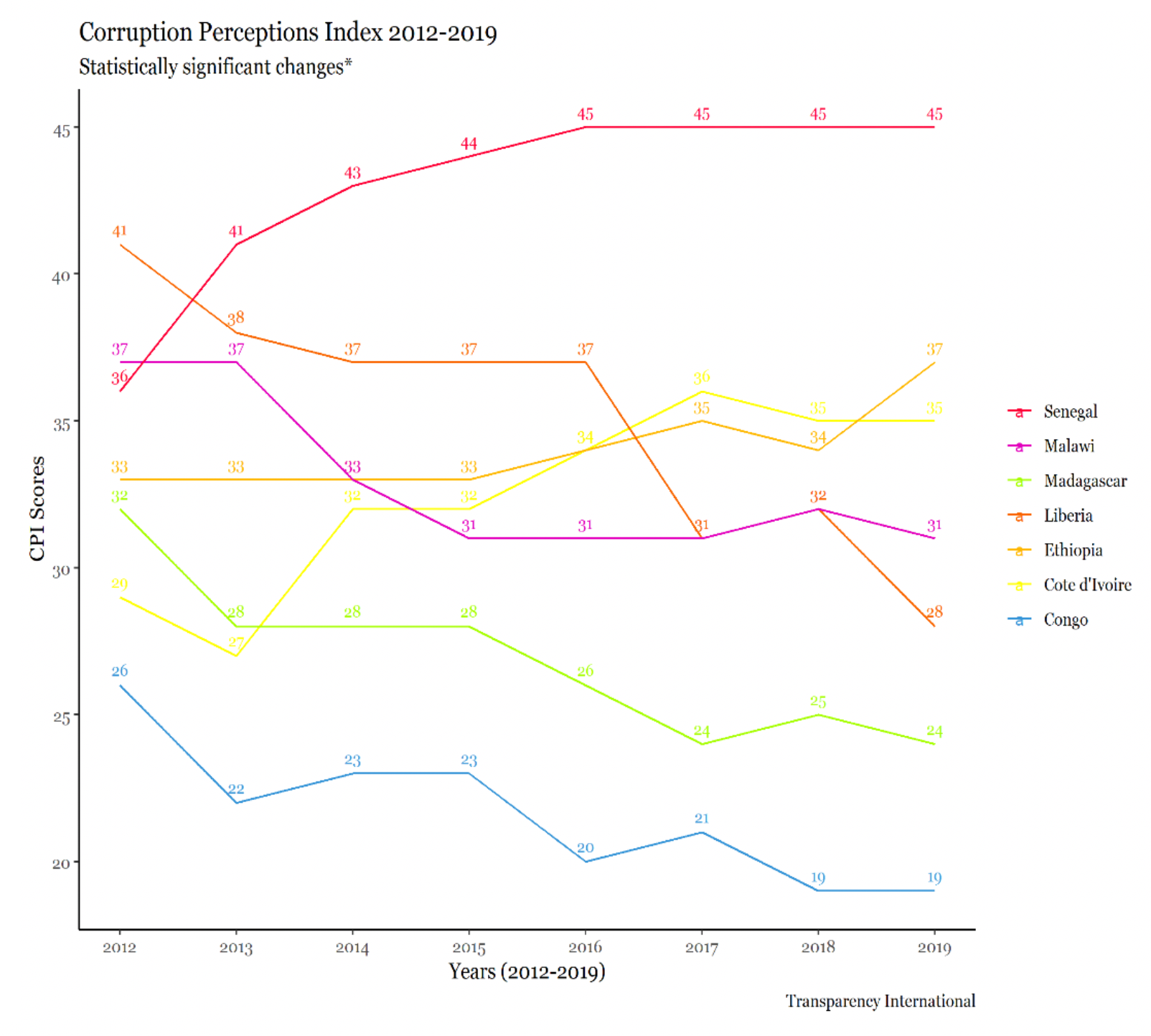

Seven countries have presented a significant change, either positive or negative, on the CPI between 2012 and 2019. The diagram below statistically shows significant changes at the 10% level only when comparing CPI 2019 against CPI 2012 scores.

Corruption Perceptions Index 2012-2019. Statistically significant changes.

* Statistically significant changes at the 10% level only when comparing CPI 2019 against CPI 2012 scores.

The biggest improvers are Senegal (+9), Cote d’Ivoire (+6) and Ethiopia (+4). Countries with the biggest decline are Liberia (-13), Madagascar (-8), Congo (-7) and Malawi (-7). On the latter category, there seems to be a correlation with the Ibrahim Index of African Governance (IIAG) particularly in the sub-category on transparency and accountability between 2008 and 2017 (Mo Ibrahim Foundation 2018). For instance, Liberia’s score went from 39.3% in 2016 to 34.9 in 2017, which was below the regional average (35.3). Congo has mostly scored below 20% on transparency and accountability. Madagascar’s score has fluctuated over the years below the regional score. Malawi’s scored went lower than the regional average between 2013 and 2015, though it has since started to improve.

Other corruption measurement tools have indicated high levels of corruption in the region. According to the 2019 Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) for Africa, based on a survey in 34 countries, about 55% of people perceived levels of corruption in their country to have increased in the previous 12 months (Transparency International 2019: 9). This corresponds with the 2017 Afrobarometer survey, which indicated a similar percentage on perceived increases in levels of corruption 263a96be732e The GCB reported that such perceptions were higher in countries such as DRC (85%), Sudan (82%) and Gabon (80%). Across African countries, the groups or institutions perceived to be most corrupt included the police (47%), government officials (39%), parliamentarians and business executives (36%) and offices of the president or prime minister (34%).

According to the most recent GCB survey, more than one in four people reported paying a bribe to access public services (Transparency International 2019: 15). This equates to nearly 130 million citizens in the 35 countries surveyed who paid bribes in a period of one year (Transparency International 2019). DRC recorded the highest bribery rate, with 80% of people indicating that they had paid bribes to access public services, followed by Liberia (53%), Sierra Leone (52%), Cameroon (48%) and Uganda (46%).

The percentage of bribery was lower in Afrobarometer’s survey, with almost one in every five people (19%) admitting to having paid a bribe to access public services (Afrobarometer, 2019:16). The most reported payments of bribes were in police assistance (26%), household utilities (20%) and acquisition of identity documents (19%). Comparatively, the GCB recorded 28% for political assistance, utilities (23%) and identity documentation (21%).

Corruption mostly affects the poor in sub-Saharan Africa. The GCB indicated that two in five of the poorest people in Africa have paid bribes to access public services, compared to one in five rich people (Transparency International 2019:17). Poor people are affected the most because they have little power to stand up against corrupt public officials nor the resources to seek private services.

The business community is not spared from bribery and corruption. According to the TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix on business bribery risk, at least 34 countries from the region scored above 50, with 1 indicating lesser risk and 100 higher risk of business bribery (TRACE International 2019). Also, about 36% of people think that business executives in Africa are corrupt (Transparency International 2019: 12).

The GCB reported that more than half (59%) of people are dissatisfied with anti-corruption efforts by their governments (Transparency International 2019: 10). Nonetheless, other surveys have shown an improvement in anti-corruption work in Africa. For instance, the WGI indicated an overall improvement on control of corruption in sub-Saharan Africa between 2013 and 2018 (World Bank 2018b). The IIAG, in the sub-category of transparency and accountability for the period 2013-2017, also indicated aggregate improvements in the reduction of corruption in government branches (+2.8 points gained) and public sector (+2.1 points), and accountability of government and public employees (+1.8) (Mo Ibrahim Foundation 2018). However, there were few retrogressive indicators, such as no improvements in anti-corruption mechanisms (0%), absence of favouritism (-0.2%), sanctions for abuse of office (‑3.5%) and abuse of corruption in the private sector (-4.9).

Other governance ratings depict a downward trend in many African countries. In terms of the Governance Index in the latest Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index, a majority of countries in Southern and Eastern Africa remain stagnant or have retrogressed on governance (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018a). The average regional score has fallen to 4.40, which is its lowest in the past seven BTI surveys. The southern and eastern region ranks the weakest on policy coordination, anti-corruption policy and efficient use of resources. Comparatively, the west and central Africa region is recording very slow progress in governance rating, with some progress on anti-corruption efforts from a lower base (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018b).

Nature of corruption challenges

Political corruption

Corruption is a serious challenge to political integrity in African countries. As the results of the 2019 GCB survey indicate, many Africans believe there is a high level of political corruption in their countries, particularly by government officials, parliamentarians, and heads of state and governments (Transparency International 2019: 12). In countries like DRC, the office of the president or prime minister (82%) and parliamentarians (79%) are perceived as the most corrupt institutions.

Political corruption can take many forms, ranging from unresolved conflicts of interest and crooked political financing to the distribution of embezzled funds, extensive patronage networks, the abuse of state resources and, ultimately, state capture.

State capture

State capture involves “a situation where powerful individuals, institutions, companies or groups within or outside a country use corruption to influence a nation’s policies, legal environment and economy to benefit their own private interests” (Transparency International Anti-Corruption Glossary). Such capture of state institutions by private persons to influence state policies and decisions for their own private benefits has become a significant concern in Africa (Lodge 2018: 23). Its main consequence is that interests of a specific group are prioritised over public interests in the operation of the state. In South Africa, the term was used often to describe the relationship between former President Jacob Zuma and the Gupta family. According to the State of Capture report by the public protector, the Gupta family profited unduly from a corrupt relationship with the former president and influenced executive decisions, such as the appointment or dismissal of ministers and the awarding of government contracts to the family’s businesses (Public Protector South Africa 2016).

State capture may involve a more indistinct proximate alignment of interests between state business and political elites through family relationships, friendships or business relationships (Martini 2012: 2). In such a situation, state policies or institutions are used to benefit the private interests of those connected to political elites. An example is Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of the former Angolan president José Eduardo dos Santos and Africa’s richest woman, who is reported to have exploited her father’s position for her own private gain. According to the Luanda Leaks, the dos Santos family’s alleged state capture included the abuse of executive power to award government contracts, telecom permits and diamond-mining rights to the benefit of Isabel and her family (International Consortium of Investigative Journalists 2020). What is more, the Luanda Leaks revealed financial enablers, including financial institutions, law firms and accountants, who created and facilitated channels for grand corruption by the dos Santos family.

Patronage networks

Government reliance on extensive patronage networks is a common feature in some African countries. These patronage networks are part of informal power structures which determine who gets access to public resources. The patronage practices include the three Cs, namely co-optation, control and camouflage (Camargo and Koechlin 2018: 5):

- Co-optation includes the recruitment or strategic appointments of associates and potential opponents, who are granted impunity in abuse of state power and resources in exchange for mobilising support and maintaining loyalty to the regime.

- Control mechanisms are unwritten management tools for clashes of hidden interests, to safeguard elite cohesion and to impose discipline among allies.

- Camouflage involves the concealment of the realities of co-optation and control behind formal facades and policies consistent with a commitment to good governance and democratic accountability. For instance, it may include punishing a detractor to show anti-corruption commitments.

Empirical evidence has shown the existence of such informal governance or power networks in Rwanda, Tanzania and Uganda (Camargo and Koechlin 2018). In Nigeria, powerful patron-client networks in the electricity sector create opportunities for rent capture (Roy et al. 2020). Patronage systems also exist in the hector sector across sub-Saharan Africa, and has influence on health system governance including distribution of resources (Hutchinson et al. 2019).

Before the removal of President Compaoré in Burkina Faso, the executive had a massive influence on most appointments of public officials, and also controlled the payment and transfer of resources to local governments (Hagberg et al. 2017). Such strategic and clientelistic recruitment practices and control over local government financing were key electoral tactics deployed by Compaoré to remain in power (Hilgers and Loada 2013).

In DRC, patronage-client relationships characterised the presidency of Joseph Kabila as allegations were raised of corrupt cabinet ministers and government elites channelling illicit gains to the president in exchange for keeping their positions and getting protection from prosecution (Titeka & Thamani 2018). As a result, the president and his family, at the top of an enormous and organised system of graft, amassed wealth at the expense of the public. For instance, the family of the former president alleged owned more than 80 companies, and had active interests in farming, mining, banking, real estate, airlines and telecoms, and held over 71,000 hectares of land (Congo Research Group 2017).

Conflict of Interests

Some political and government leaders find themselves in situations where they stand to acquire private benefits from decisions made in their official capacity. During al-Bashir’s presidency in Sudan, government officials, members of the ruling National Congress Party and senior security members often had vested interests in state-owned enterprises, resulting in conflicts of interest and lucrative opportunities for corruption (US Department of State, 2015). Furthermore, members of the ruling party and senior security officials owned private entities which benefitted from favouritism from the government in the awarding of public contracts (US Department of State 2015: 12).

Opaque political financing

Another challenge to political integrity is the generally opaque funding of political parties. According to a report by the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance, there is insufficient regulation of political funding and election campaigns in many African countries, making it easier for corrupt activities associated with political financing to continue unchecked (Check et al. 2019).

For instance, Burkina Faso does not regulate private political funding, which increases the vulnerability of political parties to corruption risks (International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance 2018). Undisclosed political funding puts political parties and actors at risk of capture as secret funders will require a “payback” once their funded candidates get into power. In Somalia, there have been accusations of the United Arab Emirates, Qatar, Turkey and Saudi Arabia all financing the campaigns of preferred candidates, and thus fuelling corruption (Burke 2017).

Persons facing allegations of grand corruption have been involved in election campaigns, creating more corruption risks. This includes the use of dirty money to fund electoral campaigns and buy votes. In DRC’s last elections, the campaign finance team for presidential candidate Emmanuel Ramazani Shadary consisted of Albert Yuma, the CEO of Gècamines, which is DRC’s largest state-owned corporation, and Moïse Ekanga Lushyma, the director of Sino-Congolese cooperation programme (Global Witness 2018). Both had been implicated in corruption scandals involving the looting of public funds (Global Witness 2018).

Vote buying

Vote buying by political candidates remains a challenge in a number of African countries. The 2016/2017 Somalian parliamentary and presidential elections were impaired with allegations of widespread corruption (Burke 2017). Abdirazak Fartaag, a former Somali government official, alleged that the electoral system, which required only 14,000 people to elect members of parliament, who will then elect a president, resulted in “corruption inflation” as candidates bought voters to get a seat in parliament (Gettleman 2017). It was alleged that at least US$20 million was corruptly used in the parliamentary elections. This was followed by presidential candidates who accused each other of buying votes from parliamentarians. The local anti-corruption campaigners labelled it “the most expensive election, per vote” in the history of the country (Burke 2017).

Role of foreign actors

Political corruption is aggravated by multi-national companies who bribe public officials and senior politicians to win lucrative contracts or for other unlawful private gains. Many recent cases of grand corruption have involved multi-national companies. In 2017, the United Nations Department of the Treasury (2017) sanctioned Israeli billionaire Dan Gertler based on allegations of him amassing fortunes through corrupt mining and oil deals in DRC. Gertler was in a partnership with Glencore, a British-Swiss multi-national commodity trading and mining company, in their mining activities in DRC. It is alleged that Gertler acted as a middleman for multi-national companies to acquire mining rights in the country, due to his close relationship with former President Joseph Kabila. The US Treasury claimed that between 2010 and 2012 alone, over US$1.36 billion in revenues was lost through underpricing of mining assets sold to offshore companies linked to Gertler (US Department of the Treasury 2017).

Another high profile case involves the US indictment of three Mozambican public officials and five business leaders over allegations of US$2 billion fraud and money laundering scheme (US Department of Justice 2019). It was alleged that the indicted persons conspired in a fraudulent loan scheme with an international investment company which involved US$200 million in alleged bribes and kickbacks. In 2019, three Credit Suisse bankers pleaded guilty and attested to their roles in the bribery scandal (Ljubas 2019).

Countries with multi-national companies involved in corruption scandals in sub-Saharan Africa are judged not to be doing enough to prevent or sanction foreign bribery. Transparency International’s 2018 report Exporting Corruption revealed that the majority of exporting countries have limited, little or no law enforcement against bribery of foreign public officials (Dell and McDevitt 2018: 10). This implies that the majority of foreign bribery cases remain unchecked, posing a challenge to sub-Saharan Africa as one of the major target markets for multi-national companies.

Foreign countries also play a role in hiding the proceeds of political corruption from sub-Saharan Africa. It is estimated that Africa loses at least US$50 billion per year through illicit financial flows (UNECA 2015). At least 5% of the illicit outflows are attributed to corruption, which amounts to about US$2.5 billion a year lost by African countries through corruption (UNECA 2015: 24,32). Sources of these proceeds include bribery or kickbacks, extortion, self-dealing or conflicts of interest and embezzlement of public funds (Financial Action Task Force 2011: 16). Illicit funds are then stashed in offshore or foreign jurisdictions with assistance from financial institutions, bankers or lawyers (Financial Action Task Force 2011: 16). The Financial Secrecy Index 2020 gives an indication of the destination of proceeds of corruption from Africa, with the top five secrecy jurisdiction consisting of the Cayman Islands, USA, Switzerland, Hong Kong and Singapore (Tax Justice Network 2020).

Corruption, state fragility and conflict

The least peaceful countries in Africa have high levels of corruption. For instance, countries near the bottom of the 2019 CPI, such as Somalia, Sudan and South Sudan (ranked 180, 179 and 173 respectively), have experienced violent conflicts in recent years and they rank 2nd, 8th and 3rd respectively among the most fragile states in the world (Fragile States Index 2019).

Corruption corrodes state authority, capacity and legitimacy in fragile states (Johnsøn 2016: 59). For instance, high levels of corruption in Somalia have led to dysfunctional institutions, with corruption in the security sector described as “systematic and organised” (Marqaati 2017: 9). There have been reports of soldiers and internal security looting, harassing, intimidating or torturing people (Marqaarti 2017: 10-11). Dysfunctionality and rampant corruption in the security sector and state institutions create an environment for disorder and lawlessness in the country.

Corruption creates the conditions for criminality to thrive, including illicit mining, arms trading and narcotics. According to the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime, criminal networks in Mali use a combination of the threat of violence and networks of corruption to protect the illicit flow of arms, cigarettes and narcotics (Reitano and Shaw 2015). As stated in a recent report, “the pervasive levels of corruption within Sahelian states and their security apparatus have permitted criminal markets to emerge in the first place and then enabled their expansion” (Micallef 2019: 90). Proceeds from criminal activities are channelled to armed or extreme groups and militias, providing them with the financial resources to expand and destabilise the government. In addition, some of the funds are used to maintain corruption networks to ensure the smooth operation of the criminal business. As a result, there is a cycle of corruption, crime and conflict, threatening peace and stability in the country and the Sahel region.

Illegal exploitation and the trade of natural resources was identified by the UN as fuelling ongoing conflicts in DRC (UN Security Council 2017:18). The security sector in DRC is heavily involved in the mining industry, and the report noted the involvement of Major General Gabriel Amisi Kumba, who was the commander of the first defence zone, in illegal gold exploitation (UN Security Council 2017: 22). On the other side, a number of rebel and Mai-Mai groups control their own mines (Matthysen et al. 2019). This provides them with financial resources to sustain their violent activities. The UN reported that gold from conflict-affected areas is still smuggled and traded on international markets. Proceeds from the smuggled gold then go on to benefit criminal groups (UN Security Council 2017: 18).

The African Union’s agenda to silence guns by 2020 risks being hamstrung by high levels of corruption on the continent. In South Sudan, one of the most fragile countries on the continent, a recent UN report singled out corruption as a hallmark of conflict in the country as millions of dollars have been looted from public coffers (UN Commission on Human Rights 2020). In 2019, thousands of people took to the streets protesting against the deepening economic crisis and endemic corruption (Maclean and Boley 2019). Such grievances can easily spill into violence. This suggests a need for an effective anti-corruption programming to prevent violent uprisings and reprisals. Leymah Gbowee, a Liberian Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2011, reiterated that silencing the guns in Africa will require tackling corruption as it is a major factor leading to violent conflicts in the region (UN African Renewal 2019: 12).

Land corruption

Land is the bedrock of social, economic and political life in Africa. However, it is heavily susceptible to corruption. According to a study by Transparency International, one in every two people encounters corruption during land administration processes in Africa, compared to one in five persons for the rest of the world (Transparency International 2013).

Another report by Transparency International on land corruption in Liberia, Zambia and Sierra Leone pointed out that sexual extortion, bribery, fraud, patronage and kickbacks are common forms of corruption in land administration (Wadström & Tetka 2019: 7). The problem is aggravated by structural flaws in the laws and administrative frameworks dealing with land governance. For instance, the surveyed countries lacked standardised customary tenure systems, had fragmented land policies or regulations, or their land administrative offices lacked transparency and accountability (Wadström & Tetka 2019: 9). All these factors create many opportunities for corruption to thrive.

Women are affected the most by land corruption due to their strong dependency on land (Transparency International, 2018a). Transparency International’s Land and Corruption in Africa programme conducted a baseline survey on women and land corruption together with eight national chapters: Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Madagascar, Sierra Leone, Uganda and Zimbabwe. It reported women’s experiences and everyday challenges in accessing land, and their constant exposure to bribery and sextortion by community leaders and land officials (Transparency International 2018b: 8). For instance, at least 60% of rural women surveyed in Zimbabwe had been asked for a bribe by a community leader (Transparency International 2018b: 44). In Kenya, 39% of women surveyed had been asked to pay bribes in land-related matters in the previous year (Transparency International 2018b: 24). In Liberia, at least 4% of women surveyed had either been exposed to sextortion to resolve a land issue or they knew other women who had (Transparency International 2018b: 28).

Women remain vulnerable to land dispossession, particularly in countries with land-grabbing exercises. In Zimbabwe, at least 40% of rural women and 64% of urban women surveyed indicated their vulnerability to land dispossession (Transparency International 2018b: 44). In Chisumbanje, community land was grabbed by an ethanol company, Green Fuel, which allegedly obtained the land through bribery of senior politicians. The company destroyed crops from the fields and people were forced to accept half-hectare plots, which were smaller than the land lost. An interview with displaced community highlighted how women from the displaced communities traded sex for land, and any refusal of sexual advancements resulted in a loss of land (Transparency International 2018b: 56).

Private investors are engaging in corrupt deals to access land and to bypass consultations with the affected communities. In Zambia, chiefs are bribed to use their traditional powers for the conversion of customary land into state property and long leaseholds without any input from village heads or the affected community, in contravention of the recognised principle of “free, prior and informed consent” (Wadström and Tetka 2019: 8). This is the situation in Liberia and, in some instances, research showed that corporations pay kickbacks to Liberian authorities for obtaining hectares of land without any surveys or demarcations being undertaken (Wadström and Tetka 2019: 8).

Gender-based corruption

Gender and corruption has become an area of increased focus in recent years. For instance, Transparency International Rwanda conducted a survey on gender-based corruption in public workplaces in the country (Transparency International Rwanda 9f9ab0f9ae202 It was revealed that at least 1 in 10 respondents had personally or knew someone who had experienced gender-based corruption at their workplace during the previous 12 months (Transparency International Rwanda 2018a: 33). It also indicated that gender-based corruption cases are rarely reported to superiors due to fear of retaliation or other consequences. The few respondents willing to share their experiences indicated that turning down gender-based corruption was usually met by a hostile work environment, including denial of annual leave and threats of termination of their employment contract. Even after reporting the cases to superiors, some respondents were subjected to humiliation and harassment (Transparency International Rwanda, 2018a: 34).

Some research has shown that men are more likely to pay bribes than women (Boehm and Sierra 2015). This is supported by results from the GCB survey which showed that men (32%) paid more bribes than women (25%) in sub-Saharan Africa (Transparency International 2019: 17).

Experimental studies have indicated that women tend to be more honest than men and are more concerned with fairness in their actions (Rivas 2015; Lambsdorff, Boehne & Frank 2010). It has also been attributed to the men’s traditional role as financial providers for the family, which makes them responsible for paying bribes for basic services (Transparency International, 2019: 17). According to Transparency International, “irrespective of whether women are more or less corrupt than men, they experience corruption in different ways than men, due to power imbalances and to the difference in participation in public versus domestic life” (Rheibay & Chêne 2016:6).

Some gender-based forms of corruption have roots in cultural practices that unfairly discriminate or exclude women from participation in the social, political and economic development of the country. In Somalia, studies have shown that corruption and gender inequality share roots in certain cultural practices and traditions (Ahmed 2016, 43; The Conversation 2017). For instance, traditional male leaders, who play a role in the selection of initial political candidates, have been allegedly accused of unjustifiably preferring male candidate, and thereby disadvantaging prospective female candidates (The Conversation 2017).

Another gendered form of corruption is sextortion. A recent report by Transparency International indicated that sextortion is common in many sectors, including education, police, refugee camps, judiciary and civil services (Transparency International, 2020). There are many reported cases of sextortion across African countries. For instance, an investigation into refugee camps in Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya, Uganda and Yemen unearthed corruption by employees from the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), who accepted bribes from refugees in exchange for listing them for resettlement in a favourable country (Hayden 2019). It was reported that some refugee women and girls were forced to pay bribes in the form of sex. The UNHCR denied the accusations in the report and blamed them on false agents (UNHCR 2019).

Sextortion is likewise common in the provision of basic services, such as food and water. After the 2019 Cyclone Idai in Mozambique, which destroyed homesteads and livelihoods, many people became dependent on food aid programmes administered by local leaders and public officials. A report by Human Rights Watch (2019) revealed that these leaders had demanded bribes to add families to the aid list. Women who did not have money were subjected to sextortion as local leaders demanded sex for food.

There is evidence that sextortion has become an institutionalised part of corruption culture in some countries. A survey by Transparency International Zimbabwe reported that 57% of surveyed women had experienced sextortion in different sectors of the community. As one of the central informants from civil society noted, “sex is a currency in many corrupt deals in Zimbabwe. Sexual harassment is institutionalised, and women have been suffering for a long time” (Transparency International Zimbabwe 2019: 11).

Corruption in development assistance

Development assistance funds are a common target of corrupt activity in some countries and sectors. The 2018 country report for Somalia by Bertelsmann Stiftung (2018c) noted endemic misappropriation of both domestic revenues and foreign aid in federal institutions. The UN Monitoring Groups also reported on diversion and misappropriation of humanitarian aid in the country (UN Security Council, 2016: 31).

Corruption in donor aid can strain relationships between recipient governments and international donors. In Uganda, there was a corruption scandal in its refugee programmes as funds went missing (Gitta and Fröhlich 2019). The scandal also exposed an inflation of the number of refugees by over 300,000. As a result of the scandal, some countries, such as Germany, UK and Japan, suspended aid. Likewise, in 2018, the UK suspended its funding to Zambia after admission by the government that funds targeted for poor families had gone missing (Papachristou 2018).

Overview of anti-corruption frameworks in sub-Saharan Africa

International instruments

United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC)

UNCAC was adopted on 31 October 2003, and it entered into force on 14 December 2005. It is the sole universal anti-corruption legal instrument. It comprehensively covers five main themes: preventive measures, criminalisation and law enforcement, international cooperation, asset recovery, and technical assistance and exchange of information. All African countries, with the exception of Somalia and Eritrea, have ratified the convention.

African Union Convention in Preventing and Combating Corruption (AUCPCC)

The AUCPCC is the regional anti-corruption legal instrument, which was adopted on 1 July 2003 and entered into force on 5 August 2006. Similar to UNCAC, it covers areas such as preventive measures, criminalisation and law enforcement, international cooperation and asset recovery.

AUCPCC indicates anti-corruption consensus by African countries, but its ratification status has been lower compared to UNCAC.. According to the official AU ratification status in 2019, 43 countries had ratified the treaty out of possible 55 (African Union 70f22a42bdf6 Countries yet to ratify include Cameroon, Central Africa Republic, Cape Verde, Djibouti, DRC, Eritrea, Morocco, Mauritania, Somalia, South Sudan, Swaziland and Tunisia.

African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance

The African Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance was adopted on 30 January 2007, and came into force on 15 February 2012. It sets out standards on good governance and democracy in areas such as rule of law, free and fair elections, and prohibits unconstitutional change of government. It has been praised for its potential to enhance the implementation of shared values on democracy, good governance and credible elections in Africa (South African Institute of International Affairs 2014).

It contains specific anti-corruption provisions. Article 3 stipulates that states parties shall implement the charter in accordance with the principle of “condemnation and rejection of acts of corruption, related offenses and impunity”. In Article 27, states parties commit themselves to “improving efficiency and effectiveness of public services and combating corruption”. Under Article 33, states parties are required to institutionalise good economic and corporate governance through “preventing and combating corruption and related offences”.

African Charter on the Values and Principles of Public Service and Administration

The Charter was adopted on 31 January 2011, and it entered into force on 23 July 2016. It is aimed at enhancing professionalism and ethics in public services in Africa. Article 12 contains measures for preventing and countering corruption. It provides mandatory obligations for states parties to establish independent anti-corruption institutions, and ensure constant sensitisation of public service agents and users on “legal instruments, strategies and mechanisms used to fight corruption”. Furthermore, states parties are required to establish national accountability and integrity systems for the purpose of promoting “value-based societal behaviour and attitude as a means to preventing corruption”. Lastly, the article specifies that “States Parties shall promote and recognise exemplary leadership in creating value-based and corruption-free societies”.

African Charter on the Values and Principles of Decentralisation, Local Governance and Local Development

The Charter was adopted on 27 June 2014 and came into force on 13 January 2019. Article 5(3) provides that local governments should manage their administration and finances in an accountable and transparent manner. Article 14 is dedicated to promotion of transparency, accountability and ethical behaviour in local government. It provides measures such as establishment of national laws and provisions from local and central government to promote transparency and accountability. Subsections 3 and 4 specifically place an obligation on central and local governments or authorities to counter all forms of corruption and to establish tools to promote and protect whistleblowers and to resolve grievances.

Instruments by regional economic communities

Southern Africa Development Community (SADC) Protocol against Corruption

The SADC community consists of Angola, Botswana, Democratic Republic of Congo, Lesotho, Malawi, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania, Zambia and Zimbabwe. The SADC Protocol against Corruption was adopted on 14 August 2001, and entered into force on 8 August 2003, becoming the first anti-corruption treaty in Africa. It provides measures to prevent and counter corruption in both the public and private sectors.

The draft East African Community (EAC) Protocol on Preventing and Combating Corruption

The EAC consists of Burundi, Kenya, Rwanda, South Sudan, Tanzania, and Uganda. The draft EAC protocol has not been signed yet due to issues raised by member states (DiMauro 2014). For instance, Kenya objected to granting prosecutorial powers to anti-corruption agencies as it has granted such powers to the director of public prosecutions (DiMauro 2014).

Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) Protocol on the Fight against Corruption

ECOWAS member states are Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, Cote d'Ivoire, the Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Liberia, Mali, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Togo. The ECOWAS Protocol was signed on 21 December 2001. Information on ratifications is difficult to obtain, making it difficult to firmly state the position of the protocol. According to some media reports, the head of the Democracy and Good Governance Division of ECOWAS Commission was quoted in 2019 as saying that the protocol is in force, after meeting the ratification threshold (Premium Times Nigeria 2019).

Regional organisations and initiatives

United Nations organisations

There are several United Nations-mandated organisations that are working or have worked on anti-corruption in Africa.

High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa

In 2011, the 4th Joint African Union Commission/United Nations Economic Commission for Africa (UNECA) Conference of African Ministers of Finance, Planning and Economic Development mandated UNECA to establish the HighLevel Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa. The High Level Panel, led by former president Thabo Mbeki of South Africa, submitted its report in 2014. The report dedicated a section to corruption and illicit financial flows (IFFs), and many respondents to their questionnaires perceived corruption as the biggest source of IFFs from their countries (UNECA 2015: 32).

Finding 8 of the High Level Panel stipulated that corruption and abuse of power remained an ongoing concern to counter IFFs (UNECA 2015: 69). Its approach to tackling IFFs indicated its belief in strong anti-corruption measures as an effective tool. For instance, the panel recommended that IFFs become a specific component in the regional anti-corruption framework, the AUCPCC, and bring it within the mandate of the African Union Advisory Board on Corruption (UNECA 2015: 83-84).

United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) regional offices in Africa

UNODC is the custodian of UNCAC and serves as the Secretariat of Conference of the States Parties, the major discretionary body established under the terms of article 63 of UNCAC. UNODC has three regional offices in sub-Saharan Africa – the Southern Africa office, Eastern Africa office, and the West and Central Africa office – which are involved in anti-corruption work in their respective regions.

The Eastern and Southern Africa offices are currently involved in the implementation of a Global Project on Fast-Tracking the Implementation of UNCAC (UNODC, no date). The project is aimed at supporting SDG, 16 with an overall objective of preventing and countering corruption through the effective implementation of UNCAC. In 2017, the Eastern Africa office engaged in a regional workshop on the project together with the East Africa Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (UNODC 2017). The association gave recommendations on four thematic areas to support regional countries: public procurement, whistleblower protection, financial investigation and international cooperation.

The Southern Africa office held its regional workshop on the project in October 2019 (UNODC 2019a). The workshop focused on four thematic areas: interagency cooperation, whistleblower protection, asset disclosure, and identifying and managing conflict of interest in public procurement. Besides the project, the Southern Africa office has engaged in other anti-corruption work in the region. For instance, it held a high-level meeting with the Mozambican government to discuss strategies against the increased levels of transnational organised crime, drugs and terrorism in the country (UNODC 2019b). Corruption and money laundering were raised as specific areas where UNODC can assist and, to this effect, it has provided technical and legislative assistance to Mozambique.

The West and Central Africa office launched its mid-term report in November 2018. According to the report, the office was involved between July 2016 and July 2018 in 112 activities to prevent and counter corruption (UNODC West and Central Africa 2018: 43). Its activities included supporting a culture of integrity, law enforcement, asset recovery and IFFs. For instance, UNODC assisted in the establishment of the Norbert Zongo Cell for Investigative Journalism in West Africa (CENOZO), which encourages investigative journalism on issues such as corruption, organised crime, bad governance and violations of human rights in West Africa (UNODC West and Central Africa 2018: 44). It has also assisted Burkina Faso, Rwanda, Ghana and Nigeria to strengthen their law enforcement and justice systems (UNODC West and Central Africa 2018: 47).

African Union organisations and initiatives

African Union Advisory Board on Corruption (AUABC)

The AUABC is an independent board within the African Union, established in terms of article 22 of the AUCPCC. It has a mandate to promote and encourage the adoption of anti-corruption measures in member states to assess progress in the implementation of those measures and submit a progress report on each member state to the Executive Council on a regular basis.

The board has a strategic plan in place for the period 2018 to 2021. Its objectives include: encourage AUCPCC, promote and encourage effective domestic laws, promote the adoption of a harmonised code of conduct for public officials, and develop and implement strategies to address the corruption component of IFFs (AU Advisory Board on Corruption 2017: 53-74).

African Peer Review Mechanism (APRM)

The APRM was adopted by the African Union in 2003, and it is a mutually agreed instrument voluntarily acceded to by AU member states and aimed at encouraging the adoption of policies, standards and practices on good governance (APRM, no date). It has four thematic areas consisting of democratic and political governance, economic governance and management, socio-economic governance and corporate governance.

The APRM carries out country reviews on these thematic areas, and has made useful recommendations on anti-corruption. For instance, the 2017 review of Sudan examined anti-corruption laws and policies in the country and recommended that Sudan should consider setting up an independent anti-corruption agency and to enhance its national anti-corruption strategy (APRM 2017: 6, 10). In its second review, Uganda was encouraged to comprehensively review institutional arrangements, mandates and capacity of public institutions with anti-corruption mandates, and to develop strategies to enhance societal engagement in tackling corruption (APRM 2018: 7).

African Anti-Corruption Year, 2018

The African Union declared 2018 as the anti-corruption year in Africa under the theme Winning the Fight against Corruption: A Sustainable Path to Africa’s Transformation (African Union 2018). It signalled a commitment by African leaders to come together to curb corruption. The objectives in the anti-corruption year included (AU Advisory Board on Corruption 2018: 6):

- evaluating progress in tackling corruption since the adoption of the AUCPCC

- increasing space for the private sector, information and communications technology and civil societies in measures to curb corruption

- developing an African common position on asset recovery

- monitoring progress on ratification and implementation of anti-corruption instruments

- providing technical support to member states

- contributing to reinforcing of the implementation of anti-corruption policies

The progress report on the implementation of the anti-corruption year was presented by President Muhammadu Buhari, who was the leader responsible for the 2018 theme (African Union 2019d). The report noted three new ratifications of the AUCPCC from Angola, Mauritius and Sudan, with Morocco and Tunisia expressing their willingness to ratify. Other noted achievements included enhanced citizen participation and engagement, agreement to review AUCPCC, identification and designation of anti-corruption priorities, such as the common position on asset recovery, development of an African Anti-Corruption Methodology and continued support on IFFs through the Consortium on Illicit Financial Flows (African Union, 2019c: 6).

Other organisations or initiatives

Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)

The EITI provides the global standard on good governance in the extractive industry. In 2018, EITI had 24 member states in Africa, which was almost half of its global membership.

The implementation of EITI standards have assisted African countries with better management of natural resources and increased revenue. For instance, EITI reports in DRC between the period that DRC began to implement the standards in 2007 and 2015 have indicated a regular increase in government revenue generated from the extractive industry (EITI 2018: 10).

The EITI reports on Africa have indicated that African member states have shown commitments to enhance beneficial ownership transparency measures in line with its 2020 target, with 22 African countries that had already gathered ownership information through EITI reporting (EITI 2018: 30). It also reported that DRC has been leading on advocating beneficial ownership in the extractive industry since 2014 and about 30 companies have wilfully revealed names of their beneficial owners Furthermore, the EITI played a role in the amendment of the Companies Act in Zambia to ensure beneficial ownership measures (EITI 2018: 30).

African Organisation of Supreme Audit Institutions (AFROSAI)

AFROSAI was created in 2005, and its objective is to promote and enhance shared ideas and experiences among supreme audit institutions on public finance auditing in Africa. These audit institutions are key players in national accountability and their audits, and they hold governments to account on the expenditure of public funds.

In 2018, AFROSAI undertook a “coordinated compliance and performance audit on corruption as a driver of IFFs” (AFROSAI 2018: 4). The auditors looked into the extent of the implementation of UNCAC and the AUCPCC by 12 African countries, particularly on asset declarations and public procurement systems.

The audit revealed a lack of standardised regulatory framework on asset declarations as countries differ substantially. It also urged governments to impose effective sanctions for non-compliance, enhanced verification of declarations and public access to declarations (AFROSAI 2018: 8). On public procurement, it encouraged competitive and effective procurement processes, better management of conflicts of interest, assets declarations by procurement officials and strengthening of oversight on procurement (AFROSAI 2018: 16).

Afrobarometer

Afrobarometer is an independent and pan-African research institution that conducts public surveys on key issues such as democracy and governance. It covers more than 30 African countries in country-by-country and multi-country surveys. Its questionnaires require respondents to give feedback on corruption cases. For instance, 16 questions in the Liberia survey were based on respondents’ experiences and thoughts on corruption (Afrobarometer 2018: 22-31). It collaborated with Transparency International to produce the GCB for Africa in 2019.

Financial Action Task Force (FATF)-style bodies in Africa

There are three main FATF-style bodies in Africa: the East and Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group (ESAAMLG) and the Groupe d’Action contre le blanchiment d’Argent en Afrique Centrale (Action Group against Money Laundering in Central Africa, GABAC)) and the Inter-Governmental Action Group against Money Laundering in West Africa (GIABA). As corruption is a predicate offence for money laundering, all three bodies engage in work that involves dealing with the proceeds of corruption.

For instance, ESAAMLG recently published a typologies report on corruption in public procurement and associated money laundering in the member states (ESAAMLG 2019). The report contains informative sections such as forms of procurement corruption, stages vulnerable to corruption and common red flags or indicators of corruption in the procurement sector. In addition, it provides detailed guidelines for the roles of law enforcement officials, public procurement authorities and financial intelligence unit in preventing and countering procurement corruption.

Enhancing Africa's ability to Counter Transnational Crime (ENACT)

ENACT is a regional organisation that builds the knowledge and skills required to counter transnational organised crime in Africa. Its partners include the Institute for Security Studies (ISS), INTERPOL, and it has an affiliation with the Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime (ENACT 2017). ENACT has published reports of corruption and organised crime. An example is its report of corruption facilitating organised crime in East Africa (ENACT 2019). It has analysed the role of corruption in illegal mining in Senegal (Kane 2019) and on silencing the guns by 2020 (Alusala 2018). Its partner ISS Africa published a brief policy on the role of the youth in curbing corruption in Africa (Murimi 2018).

Other stakeholders

Media

Freedom of expression remains a challenge in African countries. The lowest ranking countries in Africa on the 2019 World Press Freedom Index include Eritrea, Sudan, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, Somalia and DRC (Reporters Without Borders 2019a). Journalists face severe challenges to operate in closed communities with limited press freedom. In Somalia, for instance, Reporters Without Borders condemned the arbitrary closure of a TV channel and a news website which had published a corruption scandal as the government sought to silence independent and critical media sources (Reporters Without Borders 2019b). DRC faced internet shutdowns and blockage of social media – violating the freedom of press and access to information– during the 2018 presidential elections (Amnesty International 2019).

There have, however, been some improvements to media reforms in the region. For instance, Liberia passed the Kamara Act of Press Freedom in 2019, which repealed repressive measures such as criminal defamation of the president (Carter 2019).

Networks of investigative journalists play a fundamental role in unearthing and reporting corruption in Africa. They offer certain advantages over journalists working alone, such as combined resources and cross-border coordination. One of the leading organisations is the African Network of Centres for Investigative Reporting, which is a network of African reporters collaborating on transnational investigations and pooling resources to build capacity and expertise relevant to countering organised crime and corruption. The network worked with other investigative journalists around the world on the Panama Papers and exposed offshore accounts and hidden finances of corrupt world leaders (Fairweather 2016).

Another network, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) was instrumental in the West Africa Leaks, which exposed secret companies and financial accounts of some of West Africa’s top politicians and economic players (Fitzgibbon 2018). The ICIJ worked in collaboration with the Norbert Zongo Cell for Investigative Journalism in West Africa, which funds and coordinates transnational investigations to counter corruption, terrorism, organised crime and human rights violations.

The Global Anti-Corruption Consortium participates in a partnership with the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCPR) and Transparency International to support investigative journalists to report on corruption. Up to date, it has been involved in reporting on grand corruption in Africa. For example, OCCRP exposed large-scale looting of the Gambia’s assets by former president Yahya Jammeh and Western professionals and businesspeople who made it possible (OCCPR 2019).

Civil society

Civil society organisations tackling corruption are visible in many African countries. National chapters of Transparency International are actively involved in anti-corruption efforts across Africa through projects, research and advocacy work. For instance, TI Rwanda is involved in a project to promote transparency and accountability in climate change financing (Transparency International Rwanda 2018b). Transparency International Uganda has contributed to improved health services in Lira district by engaging with the district officials to keep tabs on poor service delivery and enhancing the capacity of community-based groups to use information and communication technology to report on sub-standard service delivery in their communities (Transparency International Uganda 2018).

The UNCAC Coalition has the largest number of civil society organisations committed to encouraging, implementing and tracking the implementation of UNCAC. There are over 35o organisations worldwide, and the Africa Anti-Corruption Platform lists 75 civil society organisations, though not all of them are members of the coalition (UNCAC Coalition, no date).

Some civil society organisations have reviewed their country’s compliance with UNCAC provisions. For example, TI Zimbabwe reviewed the country’s anti-corruption laws in 2018. It provided recommendations on key anti-corruption issues, such as the enactment of whistleblowing laws, a comprehensive anti-money laundering statute, independence of the anti-corruption commission, and education and training of law enforcement officials (TI Zimbabwe 2013: 14). The coalition has organised conferences to bring together African civil society and governments to discuss their possible collaboration to curb corruption (UNODC 2015).

Civil society organisations engage and mobilise the public to counter corruption. In Burkina Faso, the Réseau National de Lutte Anti-Corruption (REN-LAC) includes civil society organisations, media, academics, diplomats and representatives from legal bodies and ministries (Luning 2010). REN-LAC has played a key role in engaging the public on corruption issues and providing policy solutions to the government. It operates an anti-corruption hotline, though there is scarce information on responses to these complaints or statistics on cases addressed (REN-LAC 2019).

Annex 1: Overview of governance indices in SIDA priority countries

|

Control of Corruption, 2018 |

Corruption Perceptions Index 2019, score (rank out of 180) |

The Economist Democracy Index 2020 |

Rule of Law Index/ World Justice Index 2020, score (rank out of 126) |

Press Freedom Index, 2019 (rank out of 180) |

Freedom House Score |

Global Peace Index 2019 (rank out of 163) |

UNCAC Status R/A* |

AUCPCC Status |

||

|

Governance (-2.5 to +2.5) |

R/A* |

|||||||||

|

Burkina Faso |

-0.11 |

53.37 |

40 (85) |

4.04 (hybrid regime) |

0.51 (70) |

36 |

56/100 (partly free) |

104 |

2006 |

2005 |

|

DRC |

-1.50 |

3.85 |

18 (168) |

1.13 (authoritarian regime) |

0.34 (126) |

154 |

18/100 (not free) |

155 |

2010 |

signed in 2003, no R/A

|

|

Liberia |

-0.85 |

20.19 |

28 (137) |

5.45 (hybrid regime) |

0.45 (98) |

93 |

60/100 (partly free) |

59 |

2005 |

2007 |

|

Mali |

-0.70 |

26.92 |

29 (130) |

4.92 (hybrid regime) |

0.44 (106) |

112 |

41/100 (partly free) |

145 |

2008 |

2004 |

|

Rwanda |

0.58 |

71.15 |

53 (51) |

3.16 (authoritarian regime) |

0.62 (37) |

155 |

22/100 (not free) |

79 |

2006 |

2004 |

|

Somalia |

-1.80 |

0.00 |

9 (180) |

no data |

no data |

164 |

7/100 (not free) |

158 |

no R/A |

signed in 2006, no R/A |

|

South Sudan |

-1.73 |

0.48 |

12 (179) |

no data |

no data |

139 |

2/100 (not free) |

161 |

2015 |

signed in 2013, no R/A

|

|

Sudan |

-1.43 |

5.77 |

16 (173) |

2.70 (authoritarian regime) |

no data |

175 |

12/100 (not free) |

151 |

2014 |

2018 |

- The GCB and Afrobarometer surveys were drawn from the same data set.

- TI Rwanda defined gender-based corruption as “favours demanded or received by someone in a position of entrusted power, such as of sexual nature, in exchange for a service, where a person who explicitly or implicitly demands or benefits from, or accepts favours due to gender differences as a promise in order to accomplish a duty, or to refrain from carrying out his/her duties”.

- Yet to be updated to include Tunisia which submitted its instrument of ratification in February 2020.