Researching social accountability mechanisms in the water sector

Weak governance systems, poor incentives, mismanagement, and corruption undermine efficient service delivery in the water sector. The UNDP Water Governance Facility states that up to half of water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) projects fail to remain successful for a prolonged period of time, leading to an overall loss of investment between US$ 1.2 and US$ 1.5 billion over the last 20 years.c7b759201f51

One response to these challenges has been the proliferation of social accountability (SAcc) mechanisms in the water sector. Such programmes engage citizens by providing appropriate tools and capacities to hold service providers and other water-related institutions accountable in order to make water services more efficient and their distribution more just. By building an architecture that allows for more transparency, accountability, and participation in water provision, these mechanisms also entail the promise of building an ‘integrity wall’ to reduce corruption risks.7f7dc15672f0

The existing literature on SAcc in the water sector provides little insight regarding the success of such interventions. Only a few studies explicitly address SAcc mechanisms in the water sector and even fewer focus on the impact of SAcc mechanisms on improving integrity.8c93f25fd650 Generally, those studies highlight that SAcc interventions are successful in raising awareness and citizens’ demand for better services and accountability. However, state responsiveness remains slow, and it is not clear whether such interventions have a direct impact on service improvement. Such observations align with Fox’s argument that SAcc mechanisms often address the symptoms of accountability failures rather than focusing on their causes and institutional change.06089b0e5e9b

The literature illustrates that the relationship between transparency, citizen action, and accountability on the one hand and effective government response on the other is not straightforward. As Guillan, et al.872ee7550f63 point out, transparency and information do not necessarily lead to participation and action, and action does not necessarily lead to response.bdacc5f6c95f Thus, scholars have called for more ‘nuanced approaches’402be01a426f to understand what makes social accountability mechanisms successful and to gauge their long-term and unanticipated effects.ef2f9f0c524a

One prominent and thoroughly studied example of a successful SAcc mechanism is participatory and transparent budgeting (PTB).3498fc0e210f Fox shows that participatory budgeting initiatives in Brazil, Mexico, and India have had positive effects on reducing infant mortality, increasing basic service coverage, and improving targeting.adb57864b6ab While these examples refer to health, education, and employment programmes, there is less information on PTB mechanisms in the water sector. The present study aims to fill this gap. It focuses on PTB as a SAcc mechanism in Nepal and Ethiopia to analyse its effects on improving water integrity and service delivery. The PTB interventions analysed addressed the planning and monitoring processes of the construction of a water scheme in a small rural or peri-urban community. While the focus is on local level initiatives, these projects were integrated into larger national programmes.

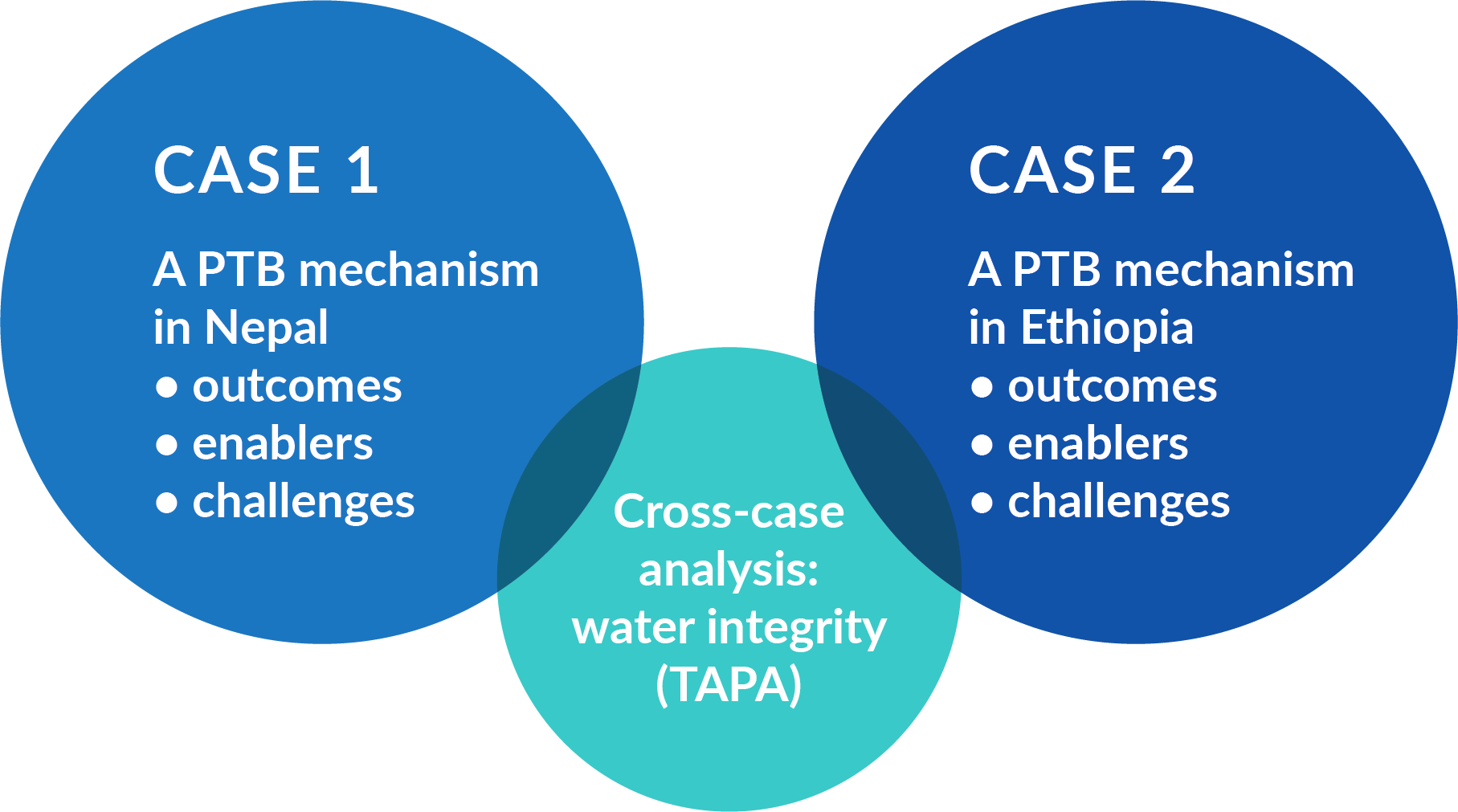

The study analyses both cases using the concept of the Integrity Wall, developed by the Water Integrity Network, as a tool to explore how these PTB mechanisms foster water integrity. Water integrity is a term that broadly refers to decision-making that is fair and inclusive, honest and transparent, accountable and free of corruption.f1e282763d0b More specifically, an assessment of water integrity involves an evaluation of the role and strength of transparency, accountability, participation, and anti-corruption (TAPA). Thus, the aim of this study is to analyse the two qualitative case studies of social accountability measures from Nepal and Ethiopia with the TAPA framework to understand how these mechanisms improve water integrity. After introducing the rationale, literature, and methodology of this project, the study initially presents the results of the two individual case studies of social accountability initiatives in light of their outcomes and challenges, and subsequently discusses the findings in relation to their impact on water integrity.

Background, rationale and methodology

The broader picture: social accountability and the water sector

In development cooperation, the concept of social accountability (SAcc) has gained momentum since the early 2000s in relation to various tools and mechanisms that aim to engage citizens in order to reduce corruption and improve services. The notion of SAcc emerged as a result of dissatisfaction with the dysfunction of formal accountability procedures such as voting and auditing. It was also due to the increasing recognition of the importance of strengthening the interaction between citizens and state in order to improve the effectiveness of service provision.74668b8abc64

The 2004 World Development Report highlighted the importance of a ‘short route’ to accountability, namely by reducing information asymmetries between clients and service providers through citizen participation and access to information.a5427ea24602 Such ‘client power’ aimed to complement the existing ‘long route’ to accountability of improving services via policy makers and state institutions. However, rights-based approaches have moved the concept beyond an ‘instrumental’ focus on users as clients. To date, the World Bank defines social accountability as the ‘extent and capability of citizens to hold the state accountable and make it responsive to their needs’.1b2d47545c33 This definition addresses both the demand side, that is, mobilising citizens to claim better services, and the supply side, which refers to improving state responsiveness by establishing mechanisms that allow for (formal) inquiry, feedback, and dialogue. Researchers have enriched this framework for understanding accountability by distinguishing between horizontal, vertical, and diagonal forms of accountability. These latter two forms address the political accountability relations between citizens and their elected representatives as well as more hybrid forms of accountability in which citizens get directly involved within state institutions.

Foxd656a2e433b7 points out that while these frameworks are valuable in understanding the various forms of (social) accountability, they are limited in their capacity as analytical tools. To understand whether SAcc actually works, the different approaches need to be disentangled and addressed individually so that we can compare and assess them. Only then can we answer whether ‘informed citizen engagement can improve the public sector’s performance’.55d84d866206 For example, Baez-Camargo and Jacobsea41850455e4 identify the core elements of SAcc as voice (here, meaning capacity building, participation, transmission of information), enforcement, and answerability. Such an approach helps to highlight the interrelation between users, policy makers, and service providers. Moreover, Grandvoinnet et al.b94c04bae2a0 distinguish SAcc mechanisms based on the types of actors (individual vs. collective) and strategies (confrontational vs. collaborative) involved. Here, grievance mechanisms or citizen report cards target individuals and aggregate individual data, whereas social audits and community scorecards are based on collective action. Whereas the latter is collaborative and involves working jointly with service providers, social audits are more confrontational as they aim to directly address actors’ wrongdoings.bba91a99793a

Other important elements that are necessary to unpack include the different needs and forms of social accountability required for each phase of service delivery (planning and design, financing, procurement, construction, and operation) and the distinction between tactical (local, one-off) and strategic (more integrated) approaches.fdd02d36b1f2 In order to identify the different forms of social accountability one must determine whether the SAcc mechanism has been introduced by an external actor such as a development agency, or whether it emerged out of the local civil society as a social movement8194b1edd0fc; whether it is based on formal or informal and direct or direct inquiry (U4 Practice Insight forthcoming); whether it draws on a particular legal context such as participatory budgeting in Brazil;3a4f7aa6653b and whether the initiatives target state and/or other non-state actors.e2aa28d95666

The table below shows examples of various SAcc mechanisms.

|

Tool |

Core features |

Further info |

|

User complaint mechanism |

Enables individuals and user groups to raise complaints, should be combined with redress mechanism. |

|

|

Establishment and empowerment of water user groups |

User groups with a legal role and status can raise demands to the service provider or regulator. |

|

|

Social audit |

Participatory examination of the impact or performance of a programme or service provider. | |

|

Community score cards |

Systematic feedback on a service between mobilised citizens and WSPs or local governments. |

|

|

Citizen report cards |

Household surveys for user feedback. Can be combined with public debates or advocacy campaigns on findings. |

Citizen report card learning toolkit: improving local governance and pro-poor service delivery |

|

Public hearing |

Dialogue between government bodies or service providers and citizens. |

|

|

Participatory budgeting |

Citizens participate in local budget decisions, either deciding over an earmarked portion of the budget or giving recommendations. |

|

|

Budget monitoring |

Monitoring budget allocation and execution. Often combined with advocacy. |

Our money, our responsibility: a citizens’ guide to monitoring government expenditures |

|

Public Expenditure Tracking Surveys (PETS) |

Quantitative exercises tracing the flow of resources from origin to destination. | |

|

Community monitoring of procurement and infrastructure development |

Civil society following procurement processes and raising red flags, physically checking infrastructure development. |

Civil society procurement monitoring tool Getting to the heart of the community: local procurement monitoring in Mongolia |

SAcc mechanisms have produced ‘mixed results’

The general rationale underlying most SAcc mechanisms is that enhancing transparency will lead to (improved) participation, which in turn will lead to accountability and government response (answerability and enforceability). Yet, while there are many individual success stories of SAcc mechanisms,137b96ad6a2b meta-studies evaluating a large number of projects have drawn attention to the difficulty of measuring results. In general, such studies found that SAcc mechanisms seem to be marked by their diverging outcomes or ‘mixed results’.e4f6ca833881

Such reviews suggest that evidence of accountability outcomes are not straightforward and are at best modest, suggesting that much of the evidence is superficial and remains limited in scope.e01319fb1b36 Fox suggests that many SAcc mechanisms only address the symptoms of accountability failures rather than focusing on causes and institutional change.1ad3bba0fdf0 He laments that researchers often too easily assume a direct relationship between transparency, citizen action, accountability, and government response, while they take for granted (and never articulate well nor analyse) links to anti-corruption and democratisation agendas.8acecc5cf57b As Guillan and others point out, information does not necessarily lead to action, and action does not necessarily lead to response.ea4854004980 Moreover, Fox distinguishes between tactical SAcc approaches that ‘are bounded, localised, and information-led’ and strategic SAcc approaches that ‘bolster enabling environments for collective action, scale up citizen engagement beyond the local arena and attempt to bolster governmental capacity to respond to voice’.6e30cb4f2e9c Thus, Fox calls for ‘vertical integration’ of SAcc interventions, meaning that social accountability action has to be interlinked and coordinated across various local, sub-national, national, and transnational scales. Vertical integration of this sort addresses power imbalances more effectively, as it generally strengthens the coordinated, independent oversight of public sector actors at all levels.9a961e414fa0

The impact of social accountability on reducing corruption is generally not the main focus of such studies, even though a DFID report states, ‘evidence does indicate overall that social accountability mechanisms can have an impact on levels of corruption,’ depending on the mechanisms used and the context within which they are implemented.4955a9a16290

Based on such conclusions, more recent works have turned to developing context assessment frameworks that help to make the ‘right fit’.996ca695f4a6 Generally, authors agree that there is need for more ‘nuanced approaches’e7086c4eea81 that draw out the relationship between SAcc mechanisms and better services, including reduced levels of corruption and increased integrity, rather than assuming a direct link. Moreover, further studies should focus on the long-term and unanticipated effects of SAcc mechanisms7b1df79311c2 as well as the extent to which broader institutional reforms integrate SAcc mechanisms.e94a51bcba12

Enhancing social accountability in the water sector

The water sector is particularly prone to weak governance systems and corruption, given that the number and complex structure of stakeholders involved, the scale of its operations, and the low level of knowledge amongst citizens create manifold opportunities for corrupt behaviour. The UNDP Water Governance Facility, for example, states that up to half of water, sanitation, and hygiene projects (WASH) fail to remain successful for a prolonged period of time, leading to an overall loss of investment between US$ 1.2 and US$ 1.5 billion in the last 20 years.14476847d901

A number of water sector organisations have deployed social accountability mechanisms to address such losses by strengthening state-citizen relations.c569d464f1e2 These tools promise to establish an extra set of checks and balances to compensate for monopolistic market structures or governmental shortcomings. However, with few exceptions, there are no comprehensive studies to provide evidence for the success of such initiatives. The 2007 WEDC synthesis report assessed a large number of accountability initiatives and comes to the result that the mechanism created greater public awareness about corruption and increased citizen satisfaction with service delivery overall. However, the study also finds that relatively few social accountability mechanisms were directly focused on the poor, and the ones that were often required a certain level of education and literacy.103e1c289c8d

Underlining these findings, other studies also show increased citizen awareness and increased demands through social accountability mechanisms. However, state responsiveness and direct impact in terms of service improvement often remain slow and/or remain understudied. This highlights the need to better integrate SAcc mechanisms into broader water sector reform programmes.8bf2d4c5cc7e

Based on a study of experiences from various water sector organisations, Hepworth concludes that changes driven by water sector social accountability initiatives are linked to increased knowledge, greater capability, new state-citizen interaction, improved advocacy, enhanced dialogue, material improvements, system/policy change, building of trust and legitimacy, outward learning, and uptake.78b638b76835 These various and diverse outcomes that this review collects suggest that more studies are needed to show in-depth how and when various mechanisms are linked to particular outcomes.

In sum, these studies reiterate that firstly, SAcc mechanisms require a favourable context (legal-political and community) and should be designed to help to create this favourable context through institutional reforms. Otherwise they face the risk of (re)creating unequal power relationships or even creating new opportunities for corruption (eg ‘tokenistic or ‘captured’ forms of participation). Secondly, SAcc initiatives in the water sector create citizen awareness and demand. However, the extent to which the respective institutions meet these demands has not been studied systematically. Lastly, in all of the aforementioned studies, it remains unclear just how much of a direct effect SAcc mechanisms have on reducing corruption. This raises the question how concrete social accountability mechanisms have been effective in increasing integrity in the water sector and what exactly the contextual conditions for its success have been when it has been effective.

Zooming in: Participatory and transparent budgeting as a means to improve social accountability

Engaging citizens in budgeting processes

For the purpose of this multiple case study, this report focuses on one particular mechanism, namely participatory and transparent budgeting (PTB), to analyse its effect on social accountability and improved integrity in the water sector. PTB is a prominent and well-studied example of successful SAcc mechanisms.f857acf6f728 To enhance the democratic process locally, PTBs aim to engage ordinary users in budgeting processes by giving them the opportunity to decide how local resources should be spent and/or to monitor such expenditures.582907623f11 By making local budgets transparent and letting users participate in decision-making processes, the aim is to make local government more effective and predictable, enhancing the use of public funds and providing fewer opportunities for corruption, social exclusion, and clientelism. Moreover, increased transparency about public expenditures is also associated with increased trust in the functionality of public institutions.f9162ce8c98f

In some cases PTB projects have improved fiscal collections, reduced tax arrears and have also increased citizens’ commitment to infrastructure works.52e6c6797207 & 93d0406af9b7 The extent to which such participatory and transparency budgeting mechanisms disrupt local control of powerful actors over budgeting remains contested, however. Many studies point to the risk of elite capture of PTB when the mechanism does not challenge, but instead reinforces, the culture of local government officials that dominates the budgeting process.2208b1583baf For PTB to thrive, it is necessary that a sufficient budget to fund service delivery projects is in place, that there is a supportive political environment, and that there is a pro-active civil society with mayoral support.c17c36f2b689

PTB in the water sector

While many PTB examples refer to health, education and employment programmes,f06d732dc9b8 there is less information on PTB mechanisms in the water sector. The Water Integrity Outlook 2016 states, ‘institutional fragmentation and complex funding arrangements make the water sector particularly vulnerable to financial inefficiencies, mismanagement and corruption’.16cdfa9de2c4 Corruption and misappropriation of funds may appear in the form of inflated budgets, ghost contracts, double-counting, kickbacks and bribes, etc. Addressing such circumstances and following existing developments in the health and education sectors, there is increasing recognition that transparent and accountable allocation and management of funds is key to financing and improving water services.c806c449b7b7 For a long time, financing discussions in the water sector focused on revenues from water tariffs to cover recurrent costs and (pooled) donor funding for investments. More recently, initiatives such as Sanitation and Water for All and Public Finance for WASH have increased efforts to attract and absorb more funding from national and local government budgets and to strengthen civil society’s role in monitoring these government commitments and expenditures (eg WASHCost or wash watch).

Such public budgeting procedures705b40688f22 enable citizens to participate in local finance decisions, such as deciding over an earmarked portion of the budget or giving recommendations (participatory budgeting), to raise complaints or verify accounts (budget monitoring) or to execute quantitative exercises tracing the flow of resources from origin to destination (public expenditure tracking survey). Ideally, these approaches establish an on-going dialogue between community, governments, and service providers with the effect of building trust, capacity, confidence, and greater integrity on both sides. A few water sector case studies have shown mixed effects, however. Beall et aladc6844b2e23 suggest a positive link between participatory mechanisms and water provision, yet these studies do not only refer to budgeting processes. A case study from Peru that analyses the link from PTB to coverage and water service quality indicators finds no statistically significant relationship between PTB and measures of coverage and service continuity, even though in this case, PTB is backed by a constitutional norm, and it is mandatory at all sub-national governments levels.9cb754003c0d Moreover, it shows that PB in the water sector may also lead to inequitable outcomes, as the poor have greater costs of participation.473b4e82fefa

Research question

As mentioned earlier, PTB is one of the few areas where there is evidence of the positive impact of SAcc in specific sectors (eg health, education).5af48c0afb56 However, evidence and systematic studies within the water sector is scarce. Hence, to address this gap, the present study analyses SAcc mechanisms in two country contexts that have introduced and implemented variations of PTB. With this focus, we raise the question:

How do participatory and transparent budgeting mechanisms contribute to increased integrity in the water sector and under which conditions do they do so?

This question encompasses the following sub-questions:

- How do the similar PTB initiatives implemented in different contexts differ in terms of implementing agency, approach, process, and outcome (in regard to service delivery, sound financial management, and integrity)?

- What outcomes, enablers, and challenges in relation to establishing water integrity can be observed, and how do they differ across various country contexts?

The Integrity Wall as a research tool

The underlying assumption of legal and economic definitions of corruption – that is, the abuse of public power for private gaind740e60b7aea – presupposes a strong distinction between the public and private spheres, suggesting that those spheres can be easily defined and delineated from one another, for instance, the distinction between public office holders and the beneficiaries of public services. In this conception, public processes and public administration ideally follow clear and formal processes, guidelines, rules, roles and positions, a violation of which has detrimental effects on the provision of public goods. While such legal and economic definitions of corruption provide a good understanding of how the practice disturbs, challenges, and distorts formal legal, public, and administrative processes, those conceptsare less appropriate in communities where informal arrangements co-exist, overlap, and interact with formal settings.

To circumvent these analytical challenges, this study focuses on the extent to which water integrity as an affirmative notion can be established through indicators of transparency, accountability, participation, and anti-corruption. In this context, we follow the Water Integrity Network’s (WIN) definition of water integrity as based in a form of ‘decision-making that is fair and inclusive, honest and transparent, accountable and free of corruption’.6b5c5ca1f924 WIN provides four indicators of governance principles to effect an improvement in water integrity: transparency, accountability, participation, and a clear stance against corruption. These four principles (TAPA) are understood as integrity enablers that lead to reduced instances of corruption, promoting respect for the rule of law, triggering responsiveness, and ultimately leading to improved services in the water sector.4c0ddee5b009 The outcome of the analysis allows analysts, policy makers and other practitioners to check how ‘waterproof’ their actions and policies are, and to strengthen enforcement mechanisms with a clear focus on those who are affected most strongly – the poor and marginalised.

Figure 1. The Integrity Wall

TAPA in participatory and transparent budgeting processes

Transparency

Transparency as an indicator for water integrity refers to an open flow of information. As applied to participatory and transparent budgeting, transparency requires that accounts, intentions, projects, and steps of the budget cycle are openly published, accessible, timely, and reliable. This also requires that the corresponding roles and responsibilities, including rights and obligations, be clear, understandable, and comprehensible for all stakeholders.a229d4f39b66 The key is that information is delivered in an accessible format and with understandable language so that it allows citizens to engage with it.

Accountability

Accountability is the process of holding actors responsible for their actions. To make accountability effective in PTB means that the lines of accountability must be not only clear and transparent, but also functional. This means that roles and responsibilities of involved actors are clear and comprehensible6041151369a4 and that mechanisms are in place which enable decision makers to respond to citizens. Furthermore those decision makers not only have to be willing, but also must possess the skills, capacity, and resources to respond, and, perhaps most importantly, it must be the case that they can be made liable in case of non-action.e4506a7d1661 With respect to PTB, this raises questions about whether lines of responsibility in governance and funding systems are clear, whether budgets and plans are made public, whether it is relevant to improve water justice for all stakeholders, how large and important the budget under review is, etc.

Participation

Participation is a crucial factor in promoting water integrity. As previous experiences from other sectors have shown, all PTB processes face the risk of addressing only a selected group or particular members of the targeted community. The ability to familiarise oneself with budgeting issues requires a level of education that often only the wealthier sections of the population have achieved. The mechanism thus faces the risk that the process ends up captured by local political elites that use it to advance their personal interests, thereby reinforcing existing inequities with regard to less powerful groups.5b07dee4a7ed Issues surrounding participation raise questions about who participates and why, how marginalised people are included in the process, the gender balance of the participants, and the degree to which capacity-building mechanisms are in place to ensure effective participation.

Anti-corruption

A clear stance against corruption must strengthen regulators and law enforcement systems and provide opportunities to speak out against corruption and build platforms to discuss integrity. In regard to PTB this raises questions about how the government legislates the PTB mechanism and integrates it as part of larger governance/government programmes, the extent to which the mechanism addresses corruption directly, whether complaint mechanisms are clear and accessible, and whether there are penalties in place for abuses and protection for whistle-blowers.

Analytical framework

The four TAPA principles provide a framework for understanding and assessing the experiences observed in the two case studies of this report. For this purpose, we describe each case along three research dimensions:

- Outcomes

The various ways in which the mechanism is operationalised and how successful it is in relation to its own goals. - Enablers

The contextual and contingent factors that contribute to the outcomes of the mechanism. - Challenges

The unforeseen consequences that have an impact beyond the framing of the particular mechanism.

These dimensions serve as a basis for the cross-case analysis that focuses on the four TAPA principles.

Figure 2: Cross-case analysis

Case selection and data collection

The present report is based on a case study analysis with qualitative methods, namely interviews and observations.2e43fa712631 This report is based on two individual studies, each of which is based on a heuristic analysis of two particular PTB mechanisms two different countries. Each case study draws out how the particular PTB mechanism works, what outcomes it produces, what its enablers are, and what challenges it faces. In a second step, a cross-case study analysis juxtaposes these two individual studies along the integrity-TAPA principles of the research framework.

Case selection

The case studies were carefully selected based on the SAcc mechanism that each employs, their similarities, as well as research access to the field. After a literature review on social accountability mechanisms in general and examples from the water sector in particular, as well as interviews with selected experts from WIN’s and U4’s networks, we compiled a list of SAcc cases in the water sector. We ordered and assessed them based on a number of selection criteria drawn from our research questions. The criteria included: social accountability mechanism (similarity in form of engagement and how directly it addresses corruption and integrity issues); sector (rural and peri-urban, WASH and livestock/ irrigation or multi-purpose); key accountability problems identified by implementing actor; duration of initiative (completed/ongoing); outcome (as presented by the initiative); legal/political context (level of democratisation/political will, enabling legal frameworks, etc); focus on the poor/marginalised; availability of existing studies; possible existence of baseline data; feasibility of the mechanism; and access to the field (for research/study of the mechanism in action).

After sampling and discussing three possible research projects, the research coordination team decided on a scenario that includes two cases from two very different countries, but which nonetheless share the same phenomena. The two cases present a PTB intervention in Nepal and Ethiopia. In both these cases, PTB interventions address the planning and monitoring processes of the construction of a water scheme in a small rural or peri-urban community. Thus, the PTB mechanism in these case studies refers to oversight of investment expenditures in small water scheme projects. While the focus is on local-level initiatives, these projects are integrated into larger national programmes.

The case studies therefore focus on two similar SAcc interventions (here: participatory and transparent budgeting) in a relevantly similar sector (WSS and irrigation / livestock in rural and peri-urban areas) in different country contexts (Ethiopia, Nepal). Each case had a pro-poor and pro-vulnerable population focus.

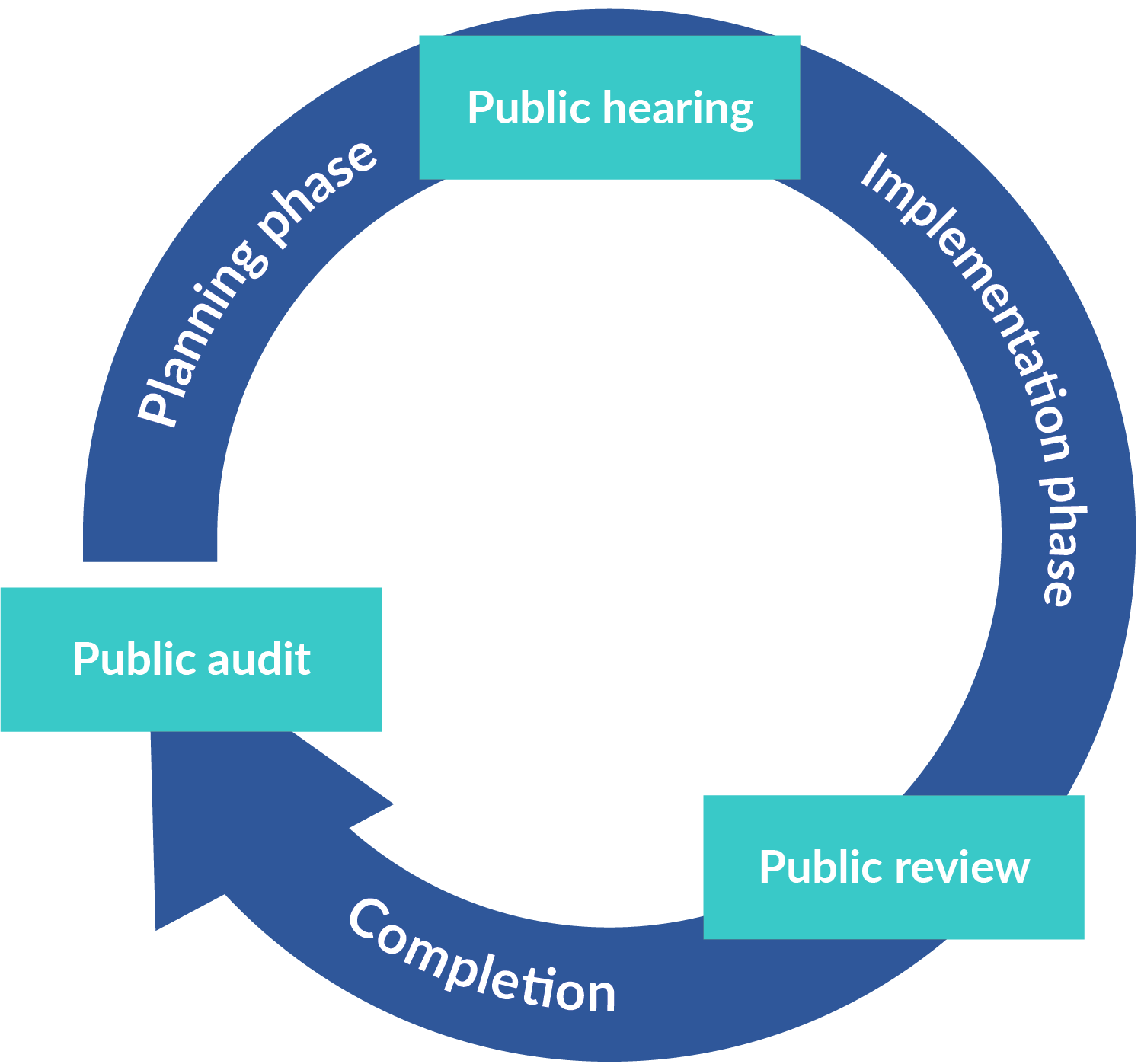

The Nepal case focuses on two communities that followed a three-step participatory budgeting process (public review, public hearing, and public audit) for the development of a water scheme as part of the nationwide WUMP programme coordinated by the Swiss development NGO Helvetas. The case represents a setting in which the PTB mechanism operates as a long-term project by an international development organisation implemented by local NGOs, and in which government authorities play a limited role, mostly due to a lack of elected officials in this particular context.

The Ethiopian case, on the other hand, focuses on two communities that implemented a budget monitoring strategy for water scheme development as part of the so-called Community Managed Project Approach (CMP). Even though this programme is not directly related to the nationwide Ethiopian Social Accountability Programme (ESAP-2) launched by the Ethiopian government in 2012 to strengthen citizen action in service provision, the case is interesting as it operates in an environment that formally endorses social accountability.

Data gathering and research teams

The present approach takes as a starting point, the viewpoint of members of the observed community and relates them to the aforementioned principles of water integrity. Two different research teams separately gathered data for the individual cases. To ensure a coherent framework for both cases, we translated the three research dimensions and the TAPA principles into a comprehensive research protocol. Throughout the data collection process, the observations and findings were shared with the research coordinator and the other participating researchers to refine the questions and support the analysis.

The research teams gathered data via desk research of relevant documents of each case and via semi-structured interviews with the actors engaged in the SAcc mechanisms (local government officials, service providers, CSOs, and water user organisations). In addition, the researchers conducted focus group discussions, engaged in participatory observation of selected events, and collected stories (about corruption) from the participants and from other publications (radio reports, newspaper reports, etc). The researchers aimed to draw out the specific problems and issues the particular community encountered when aiming to build water integrity. This also required a general awareness of how these practices and their meanings change or have changed over time.

Both research teams provided a report that presents their case along the research dimensions (outcomes, enablers, and challenges) followed by a cross-case analysis based on the TAPA principles that focuses on the mechanism’s impact on water integrity.

Findings: The impact of participatory budgeting for the water sector in Nepal and Ethiopia

CASE 1: Nepal—Public hearing, public review, and public audit in two communities

Helvetas’ Water Resources Management Program (WARM-P) in Nepal

Nepal has set ambitious goals and targets on drinking water and sanitation, both in its sector development plan and its commitment to the attainment of sustainable development goals (SDGs). Given that Nepal holds one of the lowest rankings on the Corruption Perception Index—130th amongst 168 countriesd26224596276—those water sector investments are vulnerable to illegitimate loss. But efforts are underway to improve governance and curbing corruption. An example is the development of the Nepal’s Water Supply, Hygiene and Sanitation Sector Development Plan (WASH SDP),3a0b781142d8 which acknowledges the importance of good governance and water integrity in the effectiveness of water projects and service provision.5d90c979f7ec Several non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and development organisations have used SAcc mechanisms in their intervention in the water sector.8c63ba811db7 The tools most commonly used are public hearings and public audits. Community scorecards and community feedback and accountability mechanisms are additional tools WaterAid employs in partnership with the Federation of Water Supply and Sanitation Users Nepal (FEDWASUN).

In this context, Helvetas – a Swiss NGO – initiated WARM-P in Nepal in 2001. The programme aims at supporting improved planning, co-ordination, and partnership to create a fair and equitable environment for communal water resource management. WARM-P is implemented in the Dailekh, Jajarkot, and Kalikot districts in the Mid-Western region and Achham in the Far-Western region of Nepal, regions characterised by the highest concentration of poverty in Nepal.f64d8a24387d WARM-P introduced participatory and integrated water resource planning at the lowest administrative unit level, the village development committee (VDC).d56d6ca08993 The planning process involves several stakeholders (local people from different social groups, local government, and politicians) in the VDC to prioritise water resource development based on water availability, current uses, and future needs.88e05f2a509d The process leads to the development of a Water Use Master Plan (WUMP). Once the WUMP is completed, Helvetas funds the construction of a few of the prioritised schemes in each VDC area under WARM-P. The selection of the scheme is based on the WUMP priority setting, but also depends upon the cost of each scheme and budget available under WARM-P, as well as the financial capacity of the local government, which must contribute a share of the budget (water users have to contribute with both unpaid and paid labour for the construction work). Once the four main parties (Helvetas, local partner NGO, user committee, and VDC) have approved the design of a particular scheme, the participatory construction project formally begins. It includes three social accountability events: public hearing, public review, and public audit (Figure 3). This first case study of this paper describes and analyses these three events in two Nepalese villages.

The research process

The research team selected two communities that are located in two of the four districts where WARM-P is implemented for this case study. The team made the selection in consultation with Helvetas, the implementing development organisation, and made it based on the criteria of a) caste/ethnic heterogeneity and b) individual/collective taps. Moreover, it was possible to observe one of the three PTB steps directly in one community. One drinking water scheme included individual taps and one included collective taps shared by several households.

The team conducted a total of 44 interviews as well as observations of one key event in each village, one focus group discussion in each village, and transect walks. The snowballing method was deployed to locate individual households within categories of different castes, neighbourhoods, ethnic groups, and wealth status to ensure the representation of a diversity of social actors, views, and perspectives.

The case study was conducted by the Nepal office of the International Water Management Institute (IWMI). The team of two researchers (one Nepali, one foreigner living in Nepal) worked in close consultation and coordination with the country team of the implementation agency Helvetas, both in Kathmandu and with the local WARM-P team in Surkhet district. The research team received field access from Helvetas staff and their local partner NGO as well as documents and field communication support. The IWMI researchers were present during one public audit in one community.

Table 1: Characteristics of two case studies in Nepal

|

Case Attribute |

Sanakanda scheme |

Kalikhola Bandalimadu scheme |

|

District VDC, locality |

Dailekh Goganpani VDC, wards 8 and 9 |

Achham Mastabandali VDC (now Kamal Bazaar Municipality), Gheghad (Nayabada), previously Doombada |

|

Date of preparation of the WUMP |

2002, updated in 2015 |

2011, updated in 2016-17 due to change in administrative status and boundaries |

|

No. of households |

52 |

67 |

|

No. of people |

365 |

407 |

|

Main caste/ethnic groups |

Dalits (Kami), Chhetri, Bahun |

Thakuri, Dalits, Bahun, Magar |

|

Type of scheme |

Individual taps |

Collective taps shared by households |

|

Usage |

Drinking water |

Drinking water and homestead land irrigation |

|

Project cost |

NPR 3,504,845 (US$ 32,317) |

NPR 1,792,146 (US$ 16,525) |

|

Date of scheme initiation and first user meeting |

Oct. 2014 |

Dec. 2013 |

|

Public Audit held on |

18/09/2016 |

25/12/2014 |

Contextual factors of water management schemes in Nepal

As the elections for local governments in Nepal were suspended from 2002 to 2017, local politics faced an impasse regarding spaces for democratic deliberation and good governance. In the vacuum caused by the absence of elected officials, resource allocation and service delivery was largely organised by widespread informal practices. A 2012 study pointed to widespread practices of patronage, pork-barrel politics, and kickbacks in local government units,fe90e4437daf noting that the existence of patronage and distributional coalitions often offset entitlements citizens receive from the state. The generally patrimonial nature of the Nepalese state5fa72ccc7f45 is particularly pronounced in local level politics. Local powerbrokers, such as local government bureaucrats, politicians, and important school teachers, frequently control local people’s access to local government services.ae13df5d9045 These practices can reproduce exclusions that continually keep segments of society, especially those belonging to Dalit or indigenous communities, at the margins of the society.

From 2002 onwards, The Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Local Development (MOFALD) developed several measures aiming at enhancing transparency, accountability, and participation (TAP) in the absence of elections. These included the 14-step process of planning,cc1ca68f28a7 the creation of citizen fora, and citizen awareness centres as well as provisions for adopting social accountability mechanisms. A total of 20 anti-corruption and oversight agencies and various other laws have been put in place to prevent corruption in Nepal. However, there has been a lack of confidence in these anti-corruption institutions, and a recent assessment suggests a large gap between law and practice.7a58c5e89223

At the same time, a multitude of existing community institutions still ensure the functioning of local governance. Several grassroots institutions have developed fairly well established, democratic, and transparent decision-making processes. Many of them survived through the hardships of the Maoist insurgency, even when governmental agencies were displaced from rural areas.77d7cab21c0f They have a system of regular meetings, joint planning, a certain degree of communication with government officials, and many have been around for about two decades on their own. These traditional institutions rely on the continued trust the local population has in them and they offer institutional capital for water and sanitation user groups in many communities.

Nepal relies on aid projects to finance development. While fund flows from government agencies to the local level create opportunities for bribes and rent-seeking,1105087e2ee4 aid also has the potential to change incentives for integrity in state institutions and other actors. Here, donors can play a positive role in infusing ‘good governance’ principles into the development of laws and policies. For instance, the Helvetas WUMP model is now adopted under national guidelines by the Government of Nepal.8c200259fdbd

Helvetas put in place SAcc mechanisms starting in 2002, and they gained momentum after a few years when the government introduced good governance laws.2bed1dbeefe2 Other agencies adopted SAcc mechanisms on their own, but those became increasingly streamlined under the rubric of the 2005 Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness. SAcc in WASH projects became all the more important as the government now sets ambitious targets for sustainable development goals (SDGs). In 2015, the government revised the targets on drinking water and sanitation for 2030 and emphasised governance as a key component of the new WASH Sector Development Plan (SDP). The SDP also stresses the need to enhance the accountability of politicians, policy-makers, and service providers and has put in place mechanisms to ensure that their actions are transparent. The SDP also sees social action as playing a potentially important role in enforcing compliance, especially where there is a dearth of effective regulatory institutions, as in the case of Nepal.

To sum up, there has been an increased awareness and demand for good governance in the WASH sector and beyond. However, the lack of strong institutions and the lack of accountability among local and national policy-makers have largely kept this demand from being met. Entrenched interests of patron-client relationships and distributional coalitions have become pervasive in the absence of regular cycles of elections. These pose important hurdles to the effectiveness of reform efforts.

PTB in theory: Public review, public hearing, public audit

The first SAcc mechanisms that Helvetas introduced in 2002 in WARM-P were public hearing, public review, and public audit.18ded008ec00 The NGO issued guidelines on downward accountability for community-managed infrastructure across its different programmes across several sectors in 2004.6670e2f8651b The adoption of these mechanisms gathered further momentum after 2004, notably thanks to the emergence of new regulations on the compulsory use of public audits by government agencies in Nepal for the allocation of block grants and the construction of public schemes. Helvetas Nepal also developed its own Manual on the Public Audit Practice, which is in line with the Government of Nepal’s guidelines.edc214663a7b

The three tools are linked in a project cycle, as shown in Figure 3. Once the four main implementing actors (Helvetas, local partner NGO, user committee, and VDC) decide to go forward with a particular WASH scheme and they receive a detailed technical plan from a professional service provider, the project cycle formally begins.

Each of the four actors have different roles and responsibilities. Helvetas supports the development of WUMP in its programme jurisdictions, engages with government and civil society entities from the central to the local level, and provides the highest proportion of funds in cash and in kind. They also recruit, fund, and supervise the local NGO, which is in charge of social mobilisation and/or technical support. The NGO’s role is to act as ‘social accountability practitioner,’ assisting the community with organising the PTB events, mediating between water users and WARM-P, and providing support to community leaders with respect to procurement of construction materials. Both the NGO and Helvetas provide community capacity training to ensure committee members have the right skills to manage construction work, handle its meetings and accounting, and understand the rights and responsibilities of the committee members, local users, and others. Helvetas retains the technical and financial capacity to enforce its procedures via SAcc tools.

Figure 3: PTB project cycle

The local government provides around five percent (expected share: 5-10%) of project cost, and monitors and supervises the progress of the scheme implementation. The user committee represents the local community. According to Helvetas guidelines, the elected user committee is supposed to reflect proportionate representation by caste and a fair representation of women (33%). It receives the funds and coordinates the project’s implementation. The chairperson often comes from previously formed committees active in the locality. It is often the case that the same person, most often a local leader of a dominant political party, leads several committees in the village, such as those for schools, cooperatives, or forest user groups. The table below describes the various steps of the project cycle.

Table 2: Key features of PTB processes adopted under WARM-P

|

Attribute of PTB measure |

Public hearing |

Public review |

Public audit |

|

Main objectives |

Lay out/discuss the project purpose, stakeholder roles, budget; endorse the project, get agreement, fixing the hoarding board |

Monitor the progress; clarification of issues; settle expenses and make request for funds release; revise work plan |

Provide information on cash, in kind, and labour contribution for the project; present final statement of income and expenses; decision in case of embezzlement etc; |

|

When |

At the beginning of project |

Implementation |

Completion of the project |

|

Frequency |

Once |

Twice |

Once |

|

Who should attend? |

At least 60% of water users are required, along with the user committee, VDC, local NGO partner, and Helvetas representative |

||

|

Follow-up project activity |

Contracting on the project Release of the first instalment |

Release of instalments from WARMP (and VDC) |

Final clearance |

PTB in practice: the communities

The water schemes explored in this case study – the Sanakanda scheme in the Dailekh district and the Kalikhola Bandalimadu scheme in the Achham district – serve a population of 4546 and 2931, respectively. Both communities experience strong outwards migration, meaning that almost all male villagers seasonally go to India for employment because insufficient water resources make it impossible to grow off-season vegetables to sell at the nearest market. While there are many ‘sources’ of water, almost all of them have a very small flow. The communities had an established Water Resource Management Committee even before Helvetas implemented the WUMP. Yet, as many men are away and because women do not step into public affairs due to social norms, it is often difficult for local people to hold people in power (who are largely male) accountable.

The Sanakanda scheme was part of the WUMP process in Goganpani that was first prepared in 2002 under the lead of Water Resource Management Committee by a consulting firm and updated in late 2015.cb8aedd66041 The Kalikhola Bandalimadu scheme was part of the WUMP process inMastabandali and prepared in 2011.9dbf1786c479 In both cases, it was clear that the WUMP provided a basis for Helvetas and its partners to implement the PTB public hearing, public review, and public audit during the construction phase of the scheme.

In these communities, the WARM-P project operated in four participatory arenas: the preparatory meetings of the WUMPs, the regular user group meetings, the meetings for the public hearing, public review and public audit, and the construction work as such. In both villages, the PTB process (ie public hearing, public review, and public audit) took a little more than a year and included 14 and 23 meetings, respectively. While the first public hearing initiated the project by providing information on the parameters of the project, the public reviews that took place later focused on the expenditure against received instalments, enforced community rules, and supervised the construction of the schemes. At the end of the construction of the scheme, the public audit acknowledged that the schemes were ready for commissioning after detailed technical and financial checks.

Outcomes

Generally, the PTB mechanism focused on enhancing the information the user committee provided to the users. For instance, during the Sanakanda public audit, the chairperson presented the actual expenditures versus the estimated budget, the type and number of structures completed (intake, tap, etc), the status of the maintenance fund, the financial contribution of the community, the progress/achievements on total sanitation, and a list of tasks still to be completed. The chairperson communicated the information using non-vernacular, official language. While Helvetas documents suggest using an information billboard to display financial information,4cc52519094d in this case, the chairperson communicated the budget headings and amounts only orally. Without any visual aids, it was difficult for participants to make sense of the long list of figures enumerated. An anonymous suggestion and grievances box provided an opportunity to raise questions. At the end of the session, the NGO facilitator read aloud anonymous comments (‘grievances’) that had been collected in a box during the meeting, and the chairperson responded. However, the responses were not discussed. In sum, this observation showed that the information provided during this public event predominantly informed users about achievements, costs, and expenditures (Table 3).

|

Attribute |

Public hearing |

Public review |

Public audit |

|

Information provided to users |

Agreement about project initiation, basic information about the project, the collection of maintenance fund, the opening of the bank account, and the identification of funding agencies. |

Expenditures against received instalments, enforcement of community rules, execution of total sanitation programmes, clearance of financial compliance, progress on the project’s work and remaining work, action plan |

Total cost of the project, itemised costs and costs for individual households for private tap connection, cost sharing between the participants – cash and in-kind contributions from WARM-P and the local government |

Source: Minutes of the meetings

Further interviews with users also indicated that respondents received information about the project’s progress and wage payments, but could not recall the amount of the specific budget. Male users of the Kalikhola scheme who frequently travel to India for work, reported that they did not know about the budget because of their frequent absences. Nevertheless, most respondents were clear about the extent of their labour contribution and their wages for this contribution.

The practices of the respective user committees in the two schemes differed in significant respects. While one committee was less transparent regarding detailed expenses, the other committee had published all the figures. The latter also had more detailed and specific plans of action of all activities during the public audit and specified the chairperson and one more member for procurement of construction or sanitation materials (water filter). These differences may be attributed to a more active and literate population in the latter village.

The role of water users varied greatly. They participated in monthly meetings when levies were collected. Sometimes, these meetings were formal and minuted, but in other instances, locals gathered in a designated place and held informal deliberations. Users participated to various degrees in the decisions about construction, such as procurement of materials, transportation, labour contribution, paid work in digging and filling the mainline and branch line, and construction of structures. Helvetas staff supported procurement decisions in consultation with the committee chairperson. All households participated in the paid work in digging pipelines, but also made personal contributions in the form of ‘unpaid’ labour. Some discontent regarding the payments arose, but most villagers seemed to trust the wage distribution.

The PTB mechanism provided a platform to discuss the scheme’s finances and, in one instance, led to a revelation of fund misappropriation. The revelation was possible as the information about construction materials was openly available and because the person in question was willing to speak up against a leader.

Enabling factors

The presence of the NGO worker and of the Helvetas representative provided, to some extent, a means to ensure that the chairperson was responsive to the users, and their presence built in some enforceability. At the same time, the public forums provided a channel to enhance the accountability of the NGO and Helvetas.

Moreover, Helvetas mitigated some of the corruption risks related to cost estimation and procurement through specific institutional arrangements. As the implementing agency, Helvetas hired external engineers, located outside of the programme districts, for the design of the scheme and for cost estimates. Helvetas also directly provided most of construction materials. Helvetas’ primary motive in procuring most of the material was to ensure the availability of materials, low prices, and good quality by purchasing material in bulk. Thus, opportunities for corruption lay only in the procurement of smaller items like private taps and sanitation materials, which the chairpersons of the user committees purchased themselves.

Challenges

Both committees included women, marginalised groups (Janajati, Dalit), and representatives from different localities of the villages. The Sanakanda user group was relatively mixed in terms of ethnicity and was chaired by a Brahman man, who was also a prominent village leader. In the Kalikhola water user group, about 90% of the households are Dalits, but the chairperson of the executive committee was a high caste Chhetri man. During one of the interviews, a Thakuri woman leader shared that she wanted to stand for the chairperson position but the NGO facilitator discouraged her from taking this position due to her gender. She eventually became a member of the executive committee. Such an anecdote reveals, however, that there are structural barriers that limit the opportunities for new political leaders when creating user groups. Thus despite the representation of women and disadvantaged groups on the committees, in this case, the key positions remained with individuals from socially dominant groups and already established political leaders.

The observation of a public audit also showed that the committee chairperson spoke almost exclusively, which reflected the power relations within the community. Moreover, whereas formally, the user committee leads the public audit, in this case, it was the local NGO facilitator who drove the event. Even though such public audits ideally facilitate discussion, this instance reflected a knowledge and power imbalance between the NGO personnel, local leaders and community members: the chairperson presented most information using official, formal language and steered the event, while seeking approval from the NGO facilitator. He made an oral presentation of the figures on costs that would be difficult even for an educated person to comprehend. As a result, even though participants were invited to voice their claims, nobody spoke up.

Moreover, two neighbourhoods of a predominantly indigenous group were not included in the drinking water scheme in one village. These residents expressed strong resentment about being excluded, and that point also appeared in the public audit. Helvetas indicated that the source availability was too low to include all settlements, especially those located far from the source, and the priority was to provide water to areas where hardship was more prominent (a focus on need-based approach). Nevertheless, the resentment seemed to emerge from concerns around inclusion.

The interviews and observations revealed that some of the project information was unequally distributed amongst water users. For instance, those holding leadership roles in community organisations remembered the total project cost, while most respondents suggested that they ‘heard about’ the budget but did not recall the amount. Instead, they had knowledge about what concerned them the most, such as knowing about their own labour contribution, the wage they would receive, or the work they had to do for sanitation. Thus it turned out that one’s position, level of education, and migration status shaped one’s knowledge of the project.

The PTB mechanisms addressed or responded to most of the demands from the users, but the PTB mechanisms failed to address fully some of the concerns during the construction phase. For example, some water users continuously demanded an increase in the capacity of storage tanks. The project officials, however, mentioned that they could not meet their demands as they followed the government guidelines. Thus, technical norms, topography, and source capacity also come into play when aiming to achieve equitable water distribution.

Conclusion

The study undertaken of the two villages in Nepal of public hearing, public review, and public audit revealed several following insights:

First, compared to ghost public audits/hearings that government agencies practice,00fbe814e96a the public audits / hearings conducted under WARM-P intervention were ‘real’: they actually happened. Second, the PTB measures provided opportunities for the users to have information and knowledge about the project, to participate in significant ways in the management of the project’s construction activities and partly in the design, as well as in decision-making about how to run the drinking water scheme in the future. The provision of the user committee thus served as a platform for improved transparency, accountability, and participation. However, the study also showed that the implementation of the same scheme in relatively similar localities will still produce very different outcomes in terms of actual information provided and actual user participation. This suggests that it is important to take into account a community’s specific characteristics when managing how to translate a particular SAcc mechanism into practice.

One problematic issue that arose in the process was that the scope and scale of the mechanism was not always clear: While the mechanism focused primarily on the local user committees and on their financing of the water scheme, the public fora stirred up discussions about other issues and created demands that went beyond the scope of this particular PTB mechanism (i.e. development of the scheme) and thereby left some citizens disappointed and dissatisfied.

Lastly, while user committees did have provisions for the inclusion of different social groups, high caste or elite domination still persisted. However, it is not only elite capture, but also technical standards or natural features such as topography that can limit the effectiveness of the mechanisms and leave some groups feeling excluded.

Therefore, the results indicate that the SAcc measures have enhanced information access, transparency, and participation, and have established accountability to a certain extent. At the same time, the measures operated on an uneven playing field characterised by high levels of social inequalities that the mechanism itself cannot alleviate.

CASE 2 - Ethiopia: Synergising activities between government, NGO, and water users

The One WASH National Plan (OWNP) and the Community Managed Project (CMP) approach in Ethiopia

Over the last few decades, Ethiopia has come a long way with regard to improving coverage of water and sanitation. In March 2015, it achieved the MDG 7c target on access to drinking water supply. Despite this progress 43% of the population still does not have access to improved water supply, while 72% does not have access to improved sanitation in their daily lives. The development of Ethiopia’s Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) is shaped by the sector-wide One WASH National Plan (OWNP), which features, among other things, the Community Managed Project (CMP) approach, and is the focus of the second case study. While the nation-wide Ethiopian Social Accountability Programme 2 (ESAP-2) that the Ethiopian Government launched in 2012 has since sparked a great deal of discussion, the present case study focuses on the CMP approach instead.

The CMP approach was initiated in 2003 with the aim of accelerating the establishment of the water supply in the Amhara region of Ethiopia as part of the ‘Rural Water Supply and Environmental Programme’ (RWSEP). The Ethiopian Government and the Government of Finland jointly finance this programme.54436eadf6c2 In 2010, the World Bank evaluated the CMP approach positively and recommended mainstreaming the approach nationwide. Soon thereafter, it became one of four rural WASH financing modalities in Ethiopia. By 2015, the government had implemented it in 76 woredas (districts) spread over five regions and covering nearly 3 million people with improved water supply.7f89775833d5 Similar to the WUMP programme in Nepal, the CMP approach entails that a local committee representing the community monitors and manages funds for the construction of a communal water scheme construction in order to improve the implementation, ownership, and sustainability of interventions. The CMP approach goes a step further, though, as it requires that funds for the physical construction and maintenance of water schemes be directly transferred to a community-managed account (of a micro-credit institution) over which the local committee has control. The local committee is also directly responsible – and here the approach differs from that of the previous case – for procuring the goods and services required for water scheme construction and installation.e82cb6a4babe The second case study of this paper centres on the CMP approach and is based on interviews, focus groups, and observations in two communities of the Oromia Region close to Addis Ababa.

The research process

The research team selected two community water supply schemes with CMP for field research. Both, Ela community and Quare Gora community, are located in the Jidda Woreda of the Oromia Region close to the capitol, Addis Ababa. The two communities were selected based on their accessibility and the fact that ESAP is also being implemented in the same Woreda.

The team collected qualitative data from different sources including Woreda WASH Team (WWT) members, CMP supervisors, WASHCO members, and the general user community. With regard to in-depth interviews, we interviewed seven WWT members and supervisors (all male) and 16 users of the two water supply schemes (six female and ten male). In addition, we held two focus group discussions. For comparison, we visited one institutional latrine constructed at a high school and the neighbouring water supply schemes. Along the way, we paid special attention to the sustainability, quality of construction, and management approach of the water supply schemes.

A state of emergency affected the research process during field research in 2017. At the time of research, the military did not allow people to come together and discuss socio-economic or political issues. The Command Post, the defence military that leads the country during a state of emergency, had to grant a permit for any meeting in advance. This created insecurity and confusion among both citizens and the government as to which public actions were allowed or prohibited. Understandably, the research team encountered a sense of reluctance on the part of many stakeholders to discuss accountability and corruption, and this reluctance may be reflected in the research results.

MetaMeta – Netherlands and MetaMeta – Ethiopia carried out the study.

Table 4: Characteristics of Case Studies in Ethiopia

|

Case attribute |

Ela community scheme |

Qare gora scheme |

|

Kebele |

Manga Qore kebele |

Daga Gora kebele |

|

No. of households |

47 |

28 |

|

No. or people |

212 |

150 |

|

Type of scheme |

Community hand pump |

Community hand pump |

|

Usage |

Drinking |

Drinking |

|

Cost |

41,400 ETB |

34,500 ETB |

|

Completion date |

February 2014 |

April 2013 |

Contextual factors of water management schemes in Ethiopia

Ethiopia, officially a democracy, has enjoyed double digit growth over the past decade, yet most communities are still characterised by very low levels of development and poverty, especially in rural areas. While urban centres are rapidly developing, rural areas have been left behind, particularly in terms of basic service delivery. Moreover, not all ethnic groups, minorities, and regions are equally represented under the current administration. Gender equality is also very challenging and Ethiopia ranks 0.84 on the global Gender Development Index.

Community engagement in Ethiopia has a long tradition in form of the ‘iddir,’ which is the traditional community-based mechanism that ensures that community members support each other financially and with labour. Additionally, the ‘iqub’ is a customary credit and saving scheme through which members receive a sum of money periodically on a turn-by-turn basis. These traditional mechanisms play a key role providing socio-economic support to its members, and it is those experiences which feed into newer models of social accountability. While these traditional mechanisms are strong, formally organised civil society has a shorter history in Ethiopia. The famine periods in the 1970s and 1980s led to a growing number of civil society actors, which mainly focused on relief and humanitarian interventions. This number has grown steadily after the fall of the Derg leadership in 1991 until today. In October 2016, the Ethiopian government announced a nationwide state of emergency following almost a year of unrest and protests against certain policies. This strongly affects the exercise of civil society engagement and is considered to “undermine basic rights, including freedom of expression, association and peaceful assembly”.c2ec4c17b141 At the same time, the current situation is embedded in the country’s broader history of autocratic rule and mistrust between civil society institutions and government agencies. For example, in 2009, the government passed into law the Charities and Societies Proclamation, which placed severe restrictions on civil society organisations engaging in human rights advocacy. In practice, this means that the government has to support fully every social accountability measure.

In 2012, the Government of Ethiopia launched the nation-wide Ethiopian Social Accountability Programme 2 (ESAP-2) that coordinates SAcc-related activities at the kebele and woreda levels. The Ministry of Finance and Economic Development (MoFED) endorses those activities and stipulates that CSOs must allocate a maximum of 30% to administrative costs and at least 70% to programme costs. While the present study is concerned with the PTB process of the Community Managed Project Approach, it is noteworthy that ESAP 2 also includes PTB initiatives. Unlike the CMP, in ESAP-2 initiatives funds are not directly transferred to a community managed account; however, communities are directly involved in various steps along the budget planning and expenditure process. Ethiopian NGOs throughout the country manage the process, and funding for actual implementation of WASH services comes from different government levels.4929d9d46eea

The development of Ethiopia’s Water Sanitation and Hygiene (WASH) sector is currently shaped by the One WASH National Plan (OWNP) that links together the various water sub-sectors, developing a comprehensive Monitoring and Evaluation framework and increasing attention and resources on hygiene and sanitation. This is the first sector-wide approach in WASH in Ethiopia and brings together four Ministries with the aim to cover all regions of the country. The CMP approach has an official implementation modality status within this programme (others are: Woreda Managed Project Approach; NGO-implementation; self-supply).

The discourse on corruption in Ethiopia is two-fold. On the one hand, several studies have demonstrated encouraging results showing that, compared to its African peers, Ethiopia has lower levels of petty bureaucratic corruption in basic services.34149b8916ed However, corruption levels in other sectors (eg land, mining, pharmaceuticals) are high and political corruption is widespread, leading to diminished trust in public institutions.855fed0a217a Moreover, it is important to keep in mind Ethiopia’s drive toward decentralisation, as those structural changes often create new opportunities for corruption, though there may be substantial regional differences in corruption incidences and risks.cd101586b290

PTB in theory: The CMP approach

In 2003, the Government of Ethiopia and the Government of Finland initiated the Community Managed Project (CMP) approach as part of the Rural Water Supply and Environmental Programme (RWSEP) to accelerate the implementation of water supply in the Amhara region of Ethiopia. The CMP approach aims to make communities responsible for planning, procurement, implementation, and maintenance of communal water points. Under this approach, the programme transfers funds for the physical construction of water schemes directly into a community-managed account at a micro-credit institution. The fund includes both community-generated funds (ca. 25-30%) andgovernment subsidies provided for capital expenditures. A community-elected Water and Sanitation Committee (WASHCOs) manages the procurement, construction, and operation and maintenance process of the water scheme.f14f26474a09

The CMP approach comprises several steps: First, the water district office provides information about various technological options (hardware information) and suitable sites for water points as well as information about the CMP process. In the second step, the community elects a Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene committee (WASHCO) that is responsible for the management of the proposed scheme and its funds. The five to seven members of the WASHCO are elected for a period of two to three years. The committee must include at least 40% women, members have to be direct beneficiaries of the scheme, there has to be a balance between older and younger people, and at least the secretary and the accountant have to be literate.0a499b391784

Third, the WASHCO develops a project application and submits it to the Woreda WASH Team that advises, assesses, and approves the project. In parallel, the WASHCO raises the community’s cash contributions for the scheme. Upon the water district office’s approval of the scheme, the district head and the WASHCO chairperson sign a funding agreement between themselves. After this, the WASHCO team receives four days of training in procurement, financial management, recording and reporting of construction processes. After that training, funds can be released to the community. Fourthly, the WASHCO supervises the daily follow up on the construction, including the procurement of material and services mostly from local artisans. After the completion of the scheme, a community public audit is carried out to assess the WASHCO’s work. After this audit, the WASHCO receives further training on O&M management and on tariff setting and collection.9e6a271fcd83 Until now, the CMP approach mainly dealt with simple, low-cost technologies such as hand-dug wells and other types of shallow wells. In the case of more complicated, costlier solutions, the CMP approach outsources the tendering procedure so that it takes place at the level of the regional capital.

The funding request process entails the following sub-steps: The WASHCO submits an official request to the WASH team at the woreda office, then the woreda bureau submits the request to the zonal bureau, which forwards it to the regional bureau. Then, the microfinance institution at the regional level transfers the money in instalments to the WASHCO account at the woreda level. The WASHCO must report any use of funds has with receipts before a it can request any further withdrawals. The WASHCO also deposits 1,000 ETB up front in cash at the local account (collected from households in the community) to be used for operation and maintenance (O & M). There are separate bank accounts for funding construction related costs and for O & M related costs. The construction account is closed upon completion of the scheme. Other substantial community contributions include labor and locally available construction material, while the regional government and COWASH provide the rest of the investment costs and the capacity building costs respectively. The WASHCO fully manages the finances and does the financial tracking of the investment costs and regularly reports on its undertakings to the water district office and the wider user community. The WASHCO arrives at budget decisions via a consultation process in which everyone has to agree on amounts and specific budget utilisation.

The CMP is intended as a bottom-up approach as it transfers complete decision-making responsibility as well as fund disbursement to the community for which the scheme is developed. A team delegated from the community even bears responsibility for initiating and executing a tendering process to find an appropriate service provider to install the technology.

PTB in practice: The communities

This research focused on two small communities: Ela und Quare Gora communities (kebeles) in the Jidda woreda, close to Addis Adaba. Here, rural water supply coverage has been fluctuating since the early 2010s. After a steady increase from 40.61% in 2010 to 86% in 2014, it dropped slightly again in 2015 due to a change in parameters for coverage. The CMP approach was implemented in 2011. Its goal was to ameliorate water shortage and low sanitation coverage by responding to community demands and to ensure sustainability by institutionalising a participatory budgeting system. As outlined above, the CMP approach transferred funds for the physical construction of a water scheme to a community-elected WASHCO to build and maintain the scheme. The projects in the two communities were completed in 2013 and 2014, respectively. The Oromia Regional Government, the Water, Minerals and Energy Bureau (WMEB), and the Bureau of Finance and Economic Development (BoFED) as well as COWASH-Finland carried out these projects

Outcomes