Although social accountability interventions enjoy enthusiastic support among multilateral partners and their local affiliates, the evidence for their effectiveness in reducing corruption has long been divided. The most optimistic recent consensus posits that success relies on contextual factors.4e1f456a0cf7 This paper places interventions by SEND Ghana and the Peasant Farmers Association of Ghana (PFAG) within the general context of other civil society organisation (CSO) or farmer-based initiatives. In so doing, it critically examines their innovativeness and contributions to anti-corruption initiatives in Ghana’s agricultural input subsidies and the contextual factors that shape their impact. Their use of participatory approaches allows the interventions to identify problems of misallocation or diversion of resources. At the same time, such approaches empower them to hold local government officials to account.

Agriculture can provide a pathway out of poverty

There are compelling reasons to focus on subsidies in Ghana’s agricultural sector. First, these support programmes and the sector as a whole are highly vulnerable to corruption. Second, stakeholders, including the national government, the donor community, and local CSOs, are increasingly invested in agriculture as an avenue for job creation and a pathway out of poverty. Governments across Africa have shown sustained interest in boosting agricultural productivity, because of the sector’s strategic national importance and its potential to improve rural livelihoods.173be0c3abe3 In Ghana, agriculture continues to be a crucial pillar of the economy, although its historical sectoral dominance has declined in recent years due to the expansion of the service sector. For instance, agriculture employs over a third of the economically active population.d70e9f4db65c Between 2013 and 2018, the sector contributed an average of 21.6% to gross domestic product (GDP), as against 34.5% and 43.9% for industry and services respectively.7dd7a848b1b5

However, after six years of the subsidy programme, Fearon et al.c1541fb2ecb1 concluded that the programme had been inefficient. This was despite a total of 202.5 million Ghanaian cedi (GHS; about US$53.1 million) being invested in it. Moreover, the government’s implementation of the subsidy provided many opportunities for both political and bureaucratic corruption. Stakeholders who have closely followed the subsidy programme since its inception in 2008, have been vocal about the need for continuous reforms to ensure that the subsidies reach the intended beneficiaries. Any such reform efforts have to be informed by lessons learned from past and ongoing interventions aimed at improving the implementation of the programme.

Critical research into impacts of social accountability on subsidies

This paper uses in-depth interviews with key stakeholders in the subsidy programme to critically examine social accountability interventions in the subsidy implementation. These interventions are concentrated along the border districts of the country, which also happen to have high poverty rates.b8b9db2332c9 In all, we conducted 33 in-depth interviews between July and September 2020. Interviewees included ten (10) CSO officials, of which two were national executives of SEND Ghana and PFAG. The rest were officials of local CSOs and community-based organisations (CBOs). The CSOs formed part of a loose coalition, with crosscutting networks of communications and frequent collaboration on specific projects. Both SEND Ghana and PFAG have working committees that serve as the vehicle for their social accountability interventions at the district level.

We conducted five interviews with leaders of SEND Ghana’s district committees (known as District Citizens’ Monitoring Committees [DCMCs]), and also interviewed eight focal persons from PFAG’s working committees. In addition, we spoke to four farmers and two local journalists. Finally, we interviewed four officials – two each at the local and national levels – from the Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA). We conducted most of the interviews by telephone due to the risks travelling during the Covid-19 pandemic. Only four interviews with respondents based in Accra were conducted in person. All the interviews were transcribed and coded using the Atlas.ti analysis software.

Overall, our analysis shows that the interventions have achieved many important results, including improvements in the programme’s operational design and reduced smuggling activities (although there was insufficient data to assess the true extent of smuggling or its reduction). They have also encouraged citizens’ voices and participation in public affairs. However, social accountability actors face serious obstacles, particularly the lack of legal backing and possible complicity of political agents, public officials, traditional leaders, and community members in acts of smuggling. Addressing these challenges could scale up the impact of these interventions and be potentially transformative for the fight against corruption in Ghana. This would require, among others, gaining access to more secure funding and strengthening of the linkage between social accountability and horizontal accountability mechanisms.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. It commences by briefly reviewing the literature on corruption and social accountability. The paper moves on to present the broad political context in Ghana, which frames both the FSP and social accountability initiatives. The paper then provides an overview of Ghana’s Fertiliser Subsidy Programme (FSP), tracing its evolution since inception in 2008 to its current incarnation as part of the current government’s flagship Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ) campaign. The paper then lays out the study findings, paying attention to the impacts of social accountability interventions and the factors that constrain their effectiveness. It concludes with a brief reflection on how the larger political context and local social realities shape the possibility for effective anti-corruption efforts and meaningful reforms. The paper provides some recommendations for donors, governments, and CSOs.

Social accountability yields results

Corruption is commonly understood to mean the abuse of public office for private gain. However, this definition is not specific enough. Khan et al.7d6874342d43 conceptualise corruption more narrowly within the context of rent-seeking behaviour and the rule of law. They argue that while state policies like subsidies necessarily generate rents, the form that rent-seeking activities assume is shaped by the overall state of the rule of law. Corruption in the form of informal and illegal rent-seeking tends to occur under conditions of weak rule of law. Other scholars have also stressed the importance of making a distinction between political corruption, which is perpetrated ‘at the highest levels of the political system’ by elected politicians and high-ranking public office holders, and bureaucratic corruption, which occurs ‘at the implementation end of politics’ by middle- and lower-ranking officials.d2d9ec11f376 However, both types of corruption are initiated to take advantage of opportunities for rent extraction. In the case of political corruption, the extraction can happen as an end in itself, or as a means to hold on to power.978cecf57332

Corruption is universally condemned as reprehensible because of its apparently corrosive effect on state capacity and national development. It is considered to be the primary obstacle to development and is portrayed using vivid language such as ‘predation’ and ‘prebendalism’.2948a04d8d93b54dcd79a348 For instance, in his discussion of the political economy of corruption in Ghana, Ninsina13b581f55b9 declares that the country:

...lives under the tyranny of this canker called corruption…. It has become a cancerous tumour eating into various parts of the social fabric…. It subverts and weakens the institutions of the nation-state and dissipates public resources for social development. Clearly, this is a dangerous tumour and must be attacked and uprooted.

In recognition of corruption’s devastating consequences, enormous amounts of resources have been devoted to fighting it. Conventional approaches to combating corruption rely on pursuing horizontal accountability through formal state institutions, such as effective legislatures and justice systems, the establishment of anti-corruption bodies, and civil service reforms.090e3e9821dd These approaches tend to target corruption throughout the political system, by implementing ‘strategies to improve the enforcement of formal rules across the board’.265eb3b4b4e2 However, despite decades-long efforts, horizontal accountability institutions have yielded underwhelming results.4c632c612fec

Implicit in horizontal approaches to anti-corruption is the assumption of strong political will to energise existing anti-corruption mechanisms. However, the political will to fight corruption cannot be taken as a given in developing country contexts.ef3fa45b712b As a result, vertical accountability – involving direct citizen action – has been suggested as an antidote to lack of political will.7dedb0605c86 Diagonal accountability occurs when vertical and horizontal approaches are fused, as when civil society organisations team up with citizens to demand or enforce accountability on office holders.88edb1e93f9b

‘Social accountability’ refers to these vertical and diagonal mechanisms of accountability. It involves bottom-up strategies, processes, or interventions that allow citizens to voice their opinions on public service delivery.0d400607c836 It includes a wide range of actions and mechanisms that citizens, communities, independent media, and CSOs employ to hold public officials accountable beyond the electoral cycle.ee2c29d47a42 The core of these activities includes collecting, analysing, and disseminating information, as well as advocacy for reforms.

Social accountability encompasses a wide variety of accountability tools, covering ‘traditional’ forms such as public demonstrations, advocacy campaigns, and investigative journalism, as well as more recent innovations such as citizen report cards, participatory public policymaking, public expenditure tracking, oversight committees, and citizens’ involvement in public commissions and hearings.79666188d1eb These tools have grown increasingly popular with CSOs and international development practitioners as an effective means of combating corruption.dd4baae57882

This popularity is based on the fact that social accountability has been shown to yield results. The literature is replete with case studies of social accountability’s potential to improve governance, promote local-level development through enhanced service delivery, and empower citizens.6e061a63e546 It ensures that service providers and policymakers become responsive to their citizens’ demands.72e7f90af429 In settings where regulatory capacity is weak, social accountability complements horizontal accountability by filling the gap and exercising some form of control.cd4dafbacf84 By making available the information necessary to judge the quality of goods and services provided to the public,6c30397f8b10 social accountability improves the quality of governance and policy design. It also enhances the relationship between citizens and the state, by empowering otherwise marginalised groups to claim entitlements from duty bearers (public officials). This is vital in its own right and necessary for the attainment of inclusive development outcomes.4fc5cc08e7d1

Nevertheless, social accountability is no panacea. O’Meally254a86a6691a cautions against the extreme optimism of advocates of social accountability. He points out that heavy reliance on particular methodologies and their diffusion across contexts, ‘risks obscuring the underlying social and political processes that really explain why a given initiative is or is not effective’.

Moreover, social accountability practitioners are compelled to walk a fine line between demanding accountability and avoiding political cooptation. The potential of these bottom-up anti-corruption initiatives to enforce accountability is diminished when they become politicised, i.e., when they get embroiled in and become a core part of ongoing political debates.40bf3e467c36 At the other extreme, there is the danger that by being too conciliatory in their approach, social accountability actors could end up watering down their impact. Under these conditions, social accountability could end up being ‘subordinated to liberal’ notions that are complicit in ‘preserv[ing] existing power hierarchies and limit the scope for critical evaluation of prevailing reform agendas’.1287dfebd92b

As will be shown below, the protagonists in this study are trapped somewhere between these two extremes, as they struggle to strike a balance between nurturing effective relationships with public officials, avoiding cooptation, and steering clear of ongoing partisan contestations.

Strong democracy but entrenched dysfunctions

Ghana’s political system has been described as a ‘competitive clientelistic political settlement’.70424525c0bc This explains the existence of robust electoral competition in the country, alongside widespread and entrenched governance problems and institutional dysfunctions. Ghana’s Fourth Republic, which was ushered in with the promulgation of the 1992 Constitution, was welcomed with much optimism after a chequered history of political instability marked by frequent coups. The Fourth Republic has been the longest-running and most stable period of Ghana’s history. Despite some lingering problems, scholars believe that the country is well on the path of democratic consolidation.71427ab58c61 However, it has failed to deliver the much-anticipated governance dividends, because of the incentives created by the logic of the country’s vibrant electoral democracy.

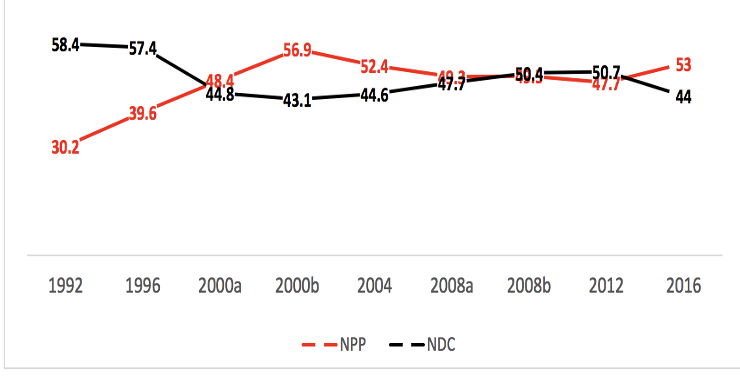

Ghana’s electoral democracy is dominated by two large political parties, the New Patriotic Party (NPP) and the National Democratic Congress (NDC), each with roughly equal mobilising capacities. Power has alternated three times between the two parties, and since 1996, both parties have consistently controlled well over 90% of votes during each election (see Figure 1). Since 1992, competition between these two parties has grown increasingly strong. The vote difference between the two tends to be narrow. In 2008, for example, the ruling NPP lost the election by less than 0.5%.50b3a488e6b8 Thus, the ruling elites feel a high degree of vulnerability due to the credible electoral threat posed by their opponents.

Figure 1. Percentage of NPP and NDC votes in presidential elections, 1992–2016

Source: Appiah and Abdulai (2017)

As a result, political leaders are increasingly obliged to make short-term policy choices aimed at distributing goods and services in a highly visible manner. This is rather than the longer-term measures that are necessary for development of the productive sectors of the economy.cae2656f267b The logic of this competitive clientelistic political settlement has compelled both political parties to follow similar policy options, despite their markedly different ideological positions: the NDC espouses a social democratic ideology while the NPP is a right-of-centre party. Furthermore, the country’s vibrant electoral democracy has rendered the policymaking vulnerable to the demands of highly mobilised interest groups. This exerts pressure on governments to adopt popular policies without regard to economic sustainability, while reducing their incentive to punish corrupt acts or embark on meaningful institutional reform.b16330a5c0cf

The negative implications of Ghana’s competitive clientelist political settlement are further complicated by institutional weakness and the constitutional concentration of too much power in the hands of the president. The 1992 Constitution of Ghana vests in the president the power to appoint and dismiss the heads of independent agencies – agencies such as the Electoral Commission, the Commission of Human Rights and Administrative Justice, and the Auditor General. It has been common practice for sitting presidents to direct heads of state agencies appointed by their political opponents to take prolonged leave of absences or other forms of leave that effectively discharges them of their roles. This happened in 2009 and 2020, when John Atta-Mills and Nana Akufo-Addo directed the then Auditor-Generals at the respective times to proceed on leave.7aca28851cf8 This enormous presidential discretion has the potential to undermine the independence and effectiveness of state anti-corruption agencies.

The lack of institutional autonomy is compounded by the fact that institutions, from parliament to the judiciary to anti-corruption agencies, are directly dependent on the executive for their operational budgets and other resources. This institutional context undermines the fight against corruption, as these agencies are ‘denied resources, and their leaders harassed, especially if they assert too much independence from political authorities’.fb8822781e65 This situation partly explains the ineffectiveness of horizontal accountability mechanisms.

Making fertiliser available and affordable for farmers

Subsidy on fertiliser was a common intervention of many early post-independence governments in Africa, to promote food security and improve agricultural productivity.a34ec9222440 However, by the 1990s, most of these subsidy programmes had been dismantled across the continent. In Ghana, the introduction of the economic recovery programme (ERP) in 1983 and the establishment of a liberalised economy led to the abolition of pan-territorial pricing and subsidies on agricultural inputs, as well as the privatisation of state-owned enterprises.04d30c4e431b However, evidence indicates that the move to abolish input subsidies resulted in a decline in food production and fertiliser usage.480e0b09133e By the early 2000s, farmers in Africa used an average of 8kg of fertilisers per hectare (ha) of arable land, compared to 135kg in Southeast Asia, 100kg in South Asia, and 73kg in Latin America.d6d77c5bda80 The consequent stagnation of agricultural production resulted in over-reliance on imports and an increasing malnutrition rate in the region.0be7ec2253ac

Against the backdrop of the global food and energy price hikes, delegates at the 2006 African Fertiliser Summit in Abuja acknowledged the need to increase the use of both organic and inorganic fertiliser to promote agricultural productivity. They resolved to make fertiliser easily and promptly accessible to farmers.57dd0330c3ce Among other things, the delegates agreed to adopt the following specific measures, to: grant targeted subsidies to the fertiliser sector; use ‘smart’ subsidies to ensure that poor smallholder farmers had access to improved seeds and fertilisers through the private sector; enhance the use of fertiliser from 8kg per ha to an average of at least 50kg per ha by 2015; create an enabling environment to boost agricultural development; and, finally, to institute ‘fertiliser-friendly’ policies.509feb5f6b97

Ghana’s ongoing Fertiliser Subsidy Programme (FSP) was first instituted in 2008 in response to global price hikes on food, fertiliser, and energy.de60e2989052 It was part of four interrelated sets of programmes introduced to boost the productivity of the agricultural sector. These included: 1) Agricultural Mechanisation Service Centres (AMSEC), which sought to make mechanisation services and equipment readily available across the country; 2) the establishment of block farms in selected areas for the consolidation of production areas to benefit from inputs, extension services, mechanisation, and credit; and 3) the establishment of the National Food Buffer Stock Company (NAFCO), to guarantee satisfactory food prices for farmers by procuring, storing, and selling farm produce, as well as mitigating post-harvest loss by absorbing excess produce.baf00a41920f

The subsidy programme introduced in 2008 instituted a nation-wide subsidy of 50% on four types of fertiliser: NPK 15-15-15, NPK 23-10-05, urea, and sulphate of ammonia. Until 2010, farmers were issued vouchers which they presented to fertiliser retailers to cover the subsidised value of their fertiliser purchase.5cde14f03fa6

Ghana’s subsidy rate of 50% was (and is) the highest in West Africa and encouraged smuggling to neighbouring Burkina Faso and Togo, where market prices were higher. This is still the case today. Diversion of the subsidised fertiliser also occurred at the regional and district Ministry of Food and Agriculture (MoFA) offices through fake vouchers/coupons or coupons unaccounted for.23a8b7a95a45 The initial implementation of the programme was further plagued by administrative challenges, including late delivery of fertilisers, inadequate storage, and district agricultural personnel being overburdened with work.c2b1be5cb221 At distribution points, some retailers also took advantage of shortages to increase retail prices.8a77373ed173

As a result, in 2010 implementation of the FSP shifted from a voucher to a waybill system, whereby the government absorbed the cost of port clearance and transportation. Under this system, smallholder farmers no longer needed coupons to benefit from the subsidy. But the waybill system was itself not immune to problems. These included lack of transparency, delays in paying suppliers, and poor monitoring, which enabled widespread diversion of the subsidised fertilisers.450549fb0e99

After gaining political power in 2017, the Akuffo Addo-led administration continued the subsidy programme under the auspices of the Planting for Food and Jobs (PFJ) campaign. The PFJ sought to strengthen the programme by developing guidelines for fertiliser distribution and by using Nation Builders’ Corps (NABCO) beneficiaries to monitor distribution at district retail points to ensure accountability.3ba14be39969

The input subsidy programme under the PFJ similarly came with a package of other complementary support services. The five pillars of the PFJ are: 1) subsidies on certified seeds; 2) subsidies on fertilisers; 3) provision of extension services; 4) provision of marketing support; and 5) the creation of a database of farmers through e-agricultural services. An indication of the fertiliser programme’s centrality to the PFJ was that from the outset, more than half of the estimated budget was dedicated to that programme (US$400,544,561 out of US$723,538,502).1d822ad6c2f6

Subsidy allocation across the country is determined by historical data on fertiliser needs and demands from each region. The northern parts of Ghana have the highest fertiliser demand and receive about 45% of the subsidy.0b8548c30cbebddea6263a5b In 2017, a total of 121,000mt of fertiliser was distributed across the country. The following year, the programme exceeded its target of 270,000mt of fertiliser, more than double the amount distributed in 2017 (see Table 1).

In 2019, the approved selling prices for fertilisers were GHS75 (~ US$13) per 50kg bag of NPK and GHS70 (~ US$12) per 50kg bag of urea. The number of fertiliser bags distributed per farmer has not been constant, with recorded variations ranging from a maximum of 15 bags to a minimum of three bags per farmer. The lack of fixed-quotas per farmer has created opportunities for rent-extraction and political manipulation, further exacerbating leakages and smuggling of the subsidised fertiliser.0b72bff05d75

Table 1. Quantity of subsidised fertilisers distributed under PFJ, 2017–18

| Fertiliser |

2017 |

2018 | |

| Actual (mt) | Target (mt) | Actual (mt) | |

| NPK | 74,734.55 | 165,000 | 167,187 |

| Urea | 28,342.73 | 85,000 | 75,830 |

| Sulphate of ammonia | 17,922.72 | – | – |

| Compost | – | 20,000 | 1,812 |

| Granular | – | – | 1,998.6 |

| Sub-total | 121,000 | 270,000 | 246,828 |

| Opening stock | – | – | 35,000 |

| Grand total |

121,000 | 270,000 | 281,828 |

Source: MoFA (2018)

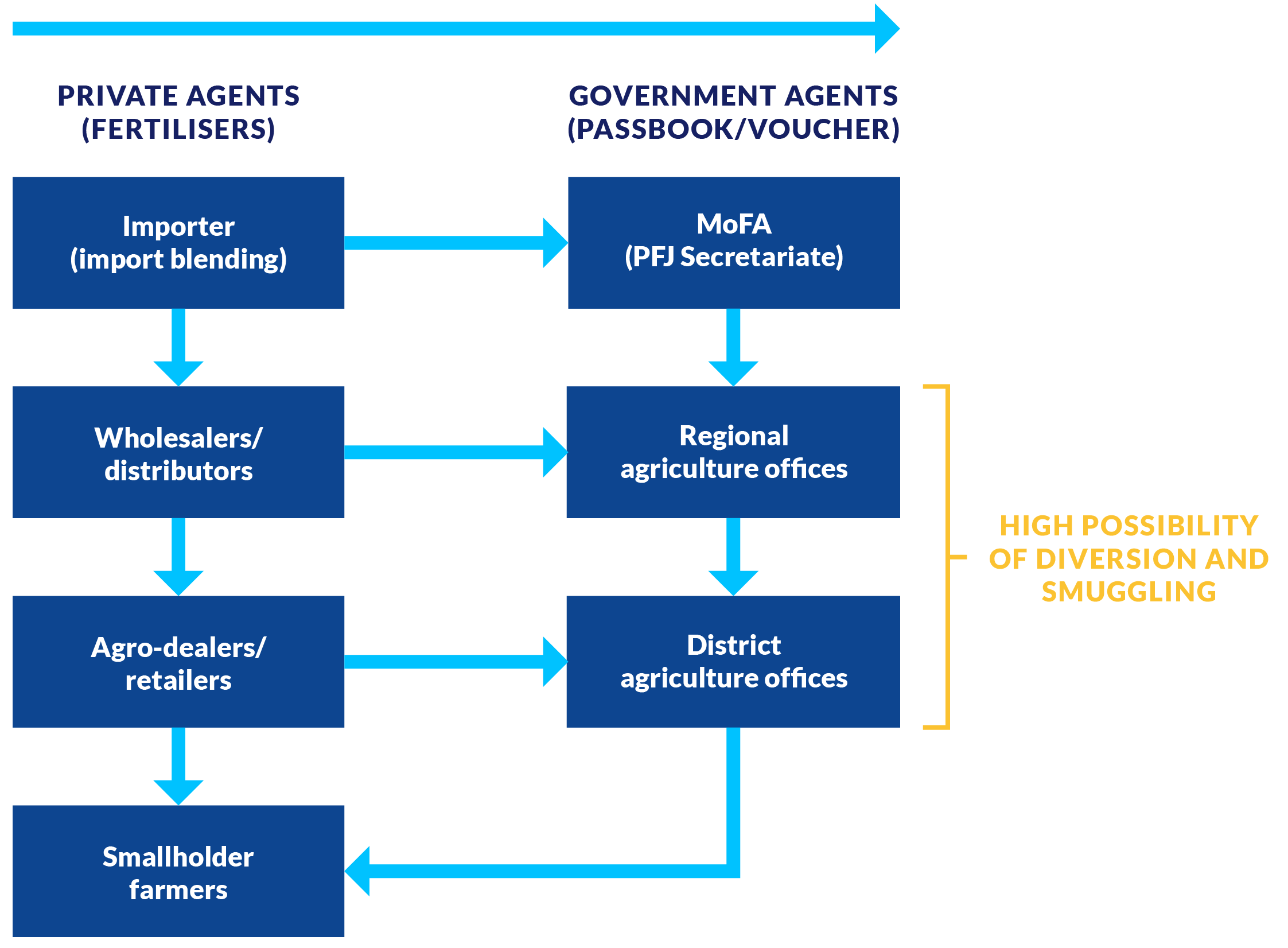

Subsidised fertiliser value chain

The prevailing subsidised fertiliser distribution value chain commences at Tema Port and proceeds to blending and processing warehouses after clearance support from the government through MoFA.1a9a76ccd1c9 The fertilisers are then repackaged and loaded onto trucks for distribution to wholesalers across the country, along with a waybill to be submitted to regional MoFA offices for endorsement. From the regional warehouses, the fertilisers are then distributed to retailers with an invoice showing details, such as the type and quantity of fertiliser, and a record sheet to record daily sales to farmers. Retailers must also submit invoices to district agricultural offices for endorsement. To access the subsidised fertilisers, farmers must go to retail points and present passbooks (which can be obtained at the various MoFA district and regional offices). To claim payment, importers need to receive and submit all endorsed forms from their distributors and retailers, for verification by the MoFA national office.856146036b51 Figure 2 depicts the process.

Figure 2. Subsidised fertiliser value chain distribution in Ghana

Source: Adapted from IFDC (2019)

Under the 2017 arrangement, farmers were allowed to pay half of the subsidised price upfront, with the remainder to be paid after harvest. However, the repayment rate was only 3% and the arrangement was scrapped in the 2018 implementation season.1d34adcc0829 Furthermore, because of instances of smuggling, the subsidised fertilisers are now packaged in 25kg bags to distinguish them from other fertilisers sold on the open market. In addition, copies of consignment waybills must be submitted to regional ministers and metropolitan, municipal, or district chief executives (MMDCEs) for endorsement. More recently, distribution at retail points is monitored by NABCO beneficiaries, whose records are used to validate sales records received from retailers.a382b3a6b003

In spite of these safeguards, fertiliser smuggling is still widespread. It is hard to determine the true scale and cost of smuggling, but the International Fertiliser Development Centrece2f7dc08e28 estimated that in 2018 alone, the country lost more than 50,000mt of subsidised fertiliser, costing the country about US$12 million. MoFA officials have expressed alarm about the cost of smuggling and have warned that if it is not checked, the entire PFJ campaign could collapse.6f12978e74f2 IFDC has recommended a reduction in the subsidy rate from 50% to 25%, in line with what prevails in neighbouring countries, to curtail smuggling. However, this is an essentially political decision, and it is uncertain whether or when it will be taken. Indeed, subsidy programmes provide fertile ground for rent-seeking behaviour and ‘create their own political momentum [that] become very difficult to reverse once in place’.1286d6759e30 In the meantime, CSOs and other stakeholders are undertaking a number of social accountability interventions to reduce instances of smuggling, as well as improve the general implementation of the subsidy programme.cee948c24246

In the next section, this paper provides details about the social accountability initiatives targeting the FSP. After an overview of these initiatives, it examines what they have achieved and how the socio-political environment in which they take place shapes their effectiveness.

Social accountability in Ghana’s Fertiliser Subsidy Programme

All social accountability interventions in the fertiliser programme start with the mobilisation of communities or farmer-based organisations (FBOs), through training or sensitisation programmes. Because the operational details of the FSP are frequently modified, CSOs engage in outreach activities to provide up-to-date information to farming communities. This includes providing communities with information about the cost, types, and availability of fertilisers in the districts. The most important social accountability activities undertaken regarding the FSP are data collection and dissemination, as well as monitoring of the distribution process to avoid smuggling.

All CSOs who participated in the present study relied on farmers and community members to collect the data they used for their needs assessment reports and to identify instances of abuse. By relying on community members to collect information, they can benefit from local knowledge that may be out of the reach of government officials. A farmer who was active in these initiatives reported that because there were many different smuggling routes in his community, only one of which the police knew well, law enforcement officials posted to his community tended to be ineffective. According to him, it was possible to ‘be in this town, and you wouldn’t know what is happening’.c653ba3bcc1a

Using the information they gathered, CSOs were then able to exact commitments from the stakeholders, including state officials, input suppliers, and the communities themselves, about how to address the shortfalls identified. They organised accountability forums where they invited ‘MoFA officers and assembly officers to town hall meetings and give them the opportunity to address allegations regarding corruption or smuggling and also give account to beneficiaries regarding certain issues’.798c224ac936

However, accountability forums are one of many options open to CSOs. To magnify the impact of these activities, the CSOs attempted to consolidate existing farmer organisations. This was especially so for PFAG, which at the time of writing was seeking to bring together all farmer organisations under a single umbrella, ‘so that we can articulate our grievances very well to get a larger voice’.19154c5e78eb Even though the CSOs took the initiative in designing social accountability interventions, the bulk of the social accountability work was carried out by the communities or, where prior specialised training was required, by selected community members.

To prevent smuggling of the subsidised fertilisers, the various CSOs had instituted mechanisms in cooperation with communities and farmer groups along the border towns. To illustrate these mechanisms, the next sections briefly describe the models used by SEND Ghana and PFAG. SEND Ghana’s DCMC and PFAG’s taskforce are not entirely independent of each other, since the parent organisation of both bodies maintains a close working relationship. Moreover, each body is composed of representatives of other local CSOs and farmer-based organisations (FBOs).

SEND Ghana’s model

SEND Ghana isa policy research and advocacy organisation established August 1998. It is the Ghanaian subsidiary of SEND West Africa, with sister organisations in Liberia and Sierra Leone. SEND Ghana works across multiple sectors, including governance, education, health, agriculture, and human development, and is involved in social accountability intervention across all these sectors. It operates through collaborations with the government, other civil society organisations (CSOs), academics, individuals, and communities. The primary vehicle for carrying out its social accountability intervention is the District Citizen Monitoring Committee (DCMC), which is an 11-member committee made up of representatives of groups within the communities. Representatives are drawn from traditional leadership, local government, CSOs, women’s groups, youth groups, and persons with disabilities. The DCMCs carry out community sensitisation, evidence generation, validation, policy engagement, securing stakeholder commitment, and ensuring regular follow-ups.

Tracking of public expenditure is the main social accountability tool employed by SEND Ghana; however, at the community level, it also organises participatory project monitoring and community score cards. SEND Ghana works closely with target communities through focal non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and DCMCs. Each district is classified as a network and is provided with some logistical support from SEND Ghana. The focal NGOs mobilise the DCMCs to organise reviews or quarterly meetings to inform the local community on issues of concern. To track the progress of these activities and programmes in the various communities, they task the district focal person or key personnel, who are computer literate and have access to the internet, to operate an electronic platform used to channel concerns and make inquiries, and record meeting proceedings. The DCMC meets quarterly and works on various social accountability projects, which involve social auditing and monitoring.

To monitor the FSP at the district level, DCMCs brief beneficiary communities and engage with them to understand the challenges regarding access to this input. A major concern across the various districts has to do with smuggling, which prevents eligible farmers from accessing the subsidy. To address this problem, DCMCs have constituted monitoring teams and stationed them along specific routes to intercept smuggling attempts. These committees work in close collaboration with the local government, local MoFA officials, and the security agencies to address smuggling and for onward processing of culprits for prosecution.

The PFAG model

The Peasant Farmers Association of Ghana (PFAG) was established in 2005 to mobilise smallholder farmers under a common umbrella and to advocate for their interests. Members include individual farmers, farmer-based organisations (FBOs), and other agribusiness stakeholders. Membership of PFAG includes 1,962 FBOs and 100,055 actors along the value chain, of which 45% are women.c8954a0f4998 PFAG has a national office in Accra, from where activities in the regions and districts are coordinated. Regions and districts have focal persons who serve as liaison officers between the national office in Accra and their respective regions. They collaborate with other key stakeholder institutions like the district assembly, Ministry of Local Government and Rural Development, the Regional Coordinating Council (RCC), traditional authorities, the media, and other CSOs. PFAG engages in advocacy, sensitisation, and monitoring of government programmes. It also organises capacity-building exercises for members to help them better monitor government agricultural interventions. The regional and district focal groups of the association spearhead PFAG’s monitoring and evaluation of the Fertiliser Subsidy Programme (FSP). The focal group is made up of a minimum of five (5) members, comprising representatives of peasant farmers, CSOs, and the Commission on Human Rights and Administrative Justice (a state anti-corruption agency).

Monitoring usually begins from the onset of the planting season. The regional focal person liaises with the input dealers and district agricultural officials to collect information on the expected date for fertiliser distribution and distribution methods. This information is then passed on to beneficiary communities. The focal persons monitor the movement of the fertiliser after it is released to the district upon the endorsement from the head of the local government. They try to gather information from all the stakeholders responsible for the distribution and delivery of the input, including the NABCO (Nation Builders’ Corps) personnel stationed at vending points, retailers, and district MoFA directors.

In 2017, PFAG and SEND Ghana collaborated to institute an apparently effective watchdog committee, which was tasked to monitor towns along the border owing to the high reported incidence of smuggling. According to national executive officials of both organisations interviewed for this study, the watchdog was extremely successful in foiling attempted acts of smuggling. However, the watchdog was part of a donor-funded project, which has since come to an end. Despite earlier assurances, the government has not stepped in to provide the necessary funding to ensure that the watchdog continues its work. The story of the watchdog is an important illustration of the fact that although social accountability mechanisms can be potent instruments in the fight against corruption, they are ultimately constrained by a lack of legal and financial backing. Social accountability actors are thus compelled to rely on voluntaristic mechanism, often with little or no logistical support. This is elaborated on further below.

Improving programme design and governance

These social accountability initiatives have had many impacts, which can be broadly categorised into programmatic impacts and governance-related impacts. Programmatic impacts have to do with modifications in the structure of the FSP and its implementation modalities. These were possible because social accountability interventions were able to successfully raise awareness about the problem of smuggling. The very existence of the monitoring exercises was enough signal to smugglers that they were being watched.6bec28cafe43 They were further able to focus public attention on the issue, through their ties with media houses. Media attention was effective in stimulating government action. In the words of one respondent, ‘There are times that we issued press statements and then government will follow up to put things in place to make sure that smuggling of the fertiliser is checked’.7baefb2a2698

As a result of heightened awareness of the issue of smuggling, monitoring of the programme has substantially improved. Some of the improvements have resulted from checks introduced by the government. The movement of the fertilisers from the regional and district centres is now subject to tighter scrutiny. Initially, there were virtually no intermediate checks between the initial loading points and the retail points, where farmers purchased the subsidised fertiliser. But now, ‘the regional officers have to clear every vehicle containing fertilisers and attach BNI [Bureau of National Investigations] officers to them before they move for fertiliser distribution’.744a41faf26d

Increased scrutiny has also had the effect of putting pressure on the input dealers to ensure that their fertilisers do not end up with smugglers, possibly because ‘they know the consequences they will face in terms of their brand identity’.fec33d2b2762 However, the penalty is not only limited to damaged reputation, as dealers whose fertilisers are found in the markets of the neighbouring country risk being heavily fined and suspended from the programme.a4b6cd19b427 In July 2019, a distribution company was indefinitely suspended from the programme after two of its trucks were impounded at the Paga border heading to Burkina Faso with 4,000 25kg bags of fertilisers meant for the Kasena Nankana district.035a4db37620

This increased level of scrutiny has been possible because of the strong collaboration which has developed between national and community-based CSOs, communities, local implementing agencies, and the media. Of these, the media partnerships are more reliable, because state anti-corruption agencies are not sufficiently independent of government control.bb53699aa6f0 The media, on the other hand, is ‘structurally independent’, and has on many occasions openly clashed with the interests of the government.1128082ae001aa1042c406e5 One journalist described how media collaboration with social accountability actors often looks:

So, what we do is that anytime we get these kinds of information, we liaise with the security agency. We tell them that there is a truck load of fertiliser packed at this place, could you please monitor it? We also make our [contact] numbers available to tell farmers along the border to call our stations if they find any car, any transporter, anybody moving along trying to cross with the fertiliser, they can blow it on air... There are a lot of tip offs we also give to the security. I’m not just alone, we’re in teams and when we see or hear anything, if a community member volunteers information, we ask the security to act on it2926caedcb92

This heightened vigilance has led to smugglers being arrested and fewer incidents of smuggling. Trucks smuggling fertilisers have been intercepted in border towns like Tumu in the Upper West Region and Paga in the Upper East region.e5626ae20279 From one account, the heightened level of awareness has resulted in the interception of about 10,000 bags of fertiliser.301c101cbaa0

As a result of increased vigilance from below and the resultant pressure on public officials, CSOs have succeeded in triggering reforms in the programme’s design. Some of these have been minor tweaks, which cannot be expected to have a substantial impact in the short term. They have, nevertheless, rendered programme implementation more transparent, thus creating more room for beneficiaries to demand accountability. The small modifications include packaging the fertiliser in 25kg bags to differentiate it from fertiliser sold on the open market and embossing the PFJ logo onto the bags.71a21f468632 Other reforms are more substantial, such as the shift from the voucher system to the waybill system which occurred in 2010.

Overall, the CSO actors believed that as a consequence of the incremental improvements in the design and monitoring of the programme, they had been able to help smallholder farmers derive a lot more benefit from the fertiliser programme than they would have been the case without the anti-corruption intervention. According to one farmer,c2f1e70eb1d3 at the start of the programme, almost all outlets were reporting shortages barely weeks after the commencement of distribution. This was forcing farmers to buy at market rates. However, once rigorous monitoring mechanisms were put in place, access to the subsidised fertiliser had vastly improved.

Beyond the programmatic improvements, social accountability interventions have also had important spillover effects, which have the potential of reconfiguring the relationship between government and citizens. These include the ability to elicit responsiveness from duty bearers. This impact extends beyond the agricultural sector. For instance, in one community that was experiencing an unstable power supply, community members teamed up with the local radio station to register their discontent with the municipal authority, the state power distribution company, and the state utility regulator. The problem was fixed shortly after this engagement.bf57d672a25f

The CSOs found that teaming up with media houses was an effective way of achieving their goals. For instance, a SEND Ghana representative narrated an encounter with a government official who, after accepting an invitation to attend a public seminar, had commented that if they failed to turn up, ‘you have your friends the media to also take us [to task]. So, our working with the media also helps’.d6ceb23edf75 By bringing duty bearers and community members together in forums where officials have had to answer to their constituents, the social accountability initiatives have been crucial in enhancing local-level accountability.

Second, and consequently, social accountability initiatives have mainstreamed the idea of popular participation in governance in parts of the country where the balance of power in state–society relations had strongly disadvantaged ordinary citizens.842034677417 Social accountability interventions have succeeded in demystifying contact between ordinary citizens and local government officials. In fact, one respondent described the emergence of a ‘cordial relationship between the district assembly and farmers’, where they often communicated in person or by phone to discuss issues of concern.7220a5e9fc9e Having built their confidence through community education and sensitisation, and by directly involving them in FSP monitoring, there have been instances where community members have on their own initiative gone to the local MoFA offices to demand particular services. Some ‘have even agitated for some specific staff to be transferred from their districts, because they are not getting their services that should be provided’.ef5fac1237f2

Across farmers, CSOs, the media, and public officials, there was acknowledgement that not only did smallholder farmers have a larger platform to air their grievances, but these complaints were also being taken more seriously.

Move from confrontation to cooperation

If there was one lesson that all participants in these initiatives have learned, it was that the approach was as important as the particular tool adopted to demand accountability. Initially, they had adopted what most of them called a ‘confrontational’ approach to anti-corruption. The earlier approach was too focused on finding fault with the programme and passing this information on to the media. Duty bearers seemed to be especially resentful of this practice, because of the political implications of such disclosures. As a CSO representative reported, political appointees would reprimand them because of the perception that ‘we are not supportive of the government’s cause and that we are too focused on the negatives’, rather than on the programme’s beneficial aspects.90fad4bfb96a They noticed that because confrontational approaches made duty bearers resistant, they tended to be ineffective:

The duty bearers normally wanted to react and protect themselves. Instead of looking at the real issue, they were rather protecting themselves40648b0cb3bd

From our past experience, we realised that being confrontational and aggressive would not yield the required results. So we have been a bit diplomatic, a bit non-confrontationalb33295177e85

In the past, I think the combative part was very loud. There are a lot of people who think that we’re biased because I recall from 2014, 2015, 2016, we were so loud and the government found us very uncomfortable. So they said we were anti-government or doing the bidding of the opposition. When the new government came in somehow we’ve gone down a bit. Not that we have gone down but we have tried to change the approachb46eb2cb214a

This change in approach involves CSOs and duty bearers collaborating in search of solutions to problems. As a result, the relationship between them has substantially improved. A national representative of PFAG reported that they had developed good relationships in many departments of MoFA. Their contacts continuously encouraged them to ‘come let us engage… PFAG, if you have any concern, come to us, don’t go to the media’.2210dc5e09d9 But this also comes with its own challenges. As another respondent concluded, ‘results come slowly in accountability work’, but having to adopt diplomacy and dialogue makes the process even slower.a8eb082a1e8c

Sometimes, this new approach to anti-corruption was deliberately cultivated. SEND Ghana reported providing advocacy training for members of its DCMC and partner CSOs. The training stressed the importance of self-presentation in a way that did not appear interrogational. As someone who had participated in this training recounted, in the past, ‘the way we presented ourselves was like we are coming to “witch-hunt” the technocrats and the politicians at the district and regional levels’.06e6754aa1d6 He felt that the training they received on communication and advocacy skills improved the way they went about their anti-corruption work.

This has also greatly improved CSO effectiveness, since they rely on the cooperation of local government officials and bureaucrats in the MoFA for their work. This might be in terms of getting access to data on expenditure and revenue for budget tracking, or meeting with responsible officials to convey the concerns of aggrieved communities. As one respondent stated, officials were more willing to cooperate with them because ‘they know I am not going to harm them’.1c7e077a0679 Once officials, especially technocrats at the local level, no longer feel themselves to be the targets of activism, they are more willing to provide support.

Important as dialogue and diplomacy were, they had their limitations. The anti-corruption campaigners were well aware of this. Not only did diplomacy substantially slow down the process, but duty bearers could actually subvert it by putting up a facade of cooperation. In anticipation of such outcomes, the CSOs kept their options open. Consequently, they made strategic use of their ties to media houses whenever behind-the-scenes consultations stalled. SEND Ghana sometimes even commissioned investigative journalism pieces.76e027786eee

When all else failed, some organisations were willing to take more drastic measures as a last resort. A former executive of the Sissala Youth Forum (SYF) described what happened after they went through every possible level of engagement without success:

So we have engaged with the [district] agric director, we have engaged with the municipal chief executive. We have also engaged with the police commander, because sometimes criminals are caught; when these business people are caught diverting the fertiliser, the police definitely come in to follow up and ensure that the right thing is done…. We have been able to meet the president and his ministers, the chief of staff at the seat of government on [matters affecting the district]. Before then, we’d also met the former president when he paid a courtesy call on the chiefs and people of the area. We followed these up with a press conference…. So after the engagement and press conferences, when we don’t see any result, we do a demonstration…. I think in December 2019, the youth carried out a demonstration to remind the government of [its] promises. And everybody got to know our problems and priorities in the area63375e365aad

However, the protest was always a tool of last resort. In Ghana’s highly charged political atmosphere, there was always a possibility that protests could backfire. On the one hand, it was possible to discredit demonstrators as doing the bidding of opponents of the government in order to incite disaffection with the ruling party. On the other hand, the protest could be derailed if it was infiltrated by agents of the opposition political party. It was partly to avoid being mired in partisan conflicts that many of these CSOs shifted towards less confrontational engagements where they could carry out their anti-corruption work ‘away from the limelight’.

Constraints on effectiveness of social accountability

In spite of their best efforts, however, there were several binding constraints that limited the effectiveness of actors involved in social accountability in the FSP. These obstacles included: 1) the personal cost to those involved; 2) the operational problems inherent in these initiatives; and 3) the politics of accountability from below.

Social accountability actors suffer personal cost

First, engaging in social accountability was found to be costly for community members who dedicated time and resources to an endeavour for which they received no personal reward. For instance, anti-smuggling task-force members made heavy time commitments, including staying up at night to track potential smugglers. Because this limited the time they could spend on their farm, but was not remunerated, many were unwilling to do it for an extended period of time.

Monitoring anti-smuggling activities also increased communal tensions and put those involved in social accountability on the defensive in their communities. Social accountability actors sometimes found their work pitted them against the interests of entire groups within the community and, in some cases, the whole community itself. Some were even denounced as traitors who ‘leak community information’.08b4ee7ec324 An executive of the Sissala Youth Forum narrated an instance where a traditional leader threatened him, saying that if he did not ensure the release of a smuggler arrested as a result of SYF’s monitoring activities, the leader would not offer him assistance if he needed it in future.db87db61bea5 Relations with community members deteriorated so much that one respondent found it necessary to ensure that his family members kept out of trouble in the community, because he feared that people might take any opportunity to attack his family.bcc7361bb8d6

Tensions could be so high that social accountability actors sometimes felt their personal safety was at stake. The interventions put them in direct conflict with the ‘shadowy network’ of smugglers. The quotations below illustrate the sense of personal insecurity that accompanied the monitoring exercises:

We do see that if you’re engaged in anti-corruption, it means that you’re indirectly preventing somebody from ‘eating’.... So it has actually been very hectic. When you’re preventing someone from doing something in a particular way, the person intentionally does it that way so that he or she can get something to ‘eat’. So if you’re preventing him from doing that, you see that you’re into trouble8acc90cbf8b6

You know some of these smugglings, they are insider jobs, okay, so the security of our farmers is being compromised. That’s the fear that we have. So you may have a farmer that’s trying to report to any of the security guys, and the officer may have an interest in the whole situation, and the guy who reported it is at risk. So that’s the weakness in it, the safety of our farmers, that’s one of the challenges that we had70eb26e3abd6

There was a time a group of individuals planned how they would deal with me. Fortunately, a brother of mine was also there. Because anytime I see them moving I either call a BNI [Bureau of National Investigations] officer or District Police Commander to come and stop their moves… So there was a time I called the national office and told them I was creating enemies for myself and risking my life for a non-payable work that I am doing…. I am thinking about the ordinary farmer, but I am endangering my life for the ordinary farmer. So if I were not there in the region, who can do that. I ask myself all these questionsd9c3f8f506b1

This fear was heightened by the widespread suspicion that those engaged in smuggling could have powerful backers who protected them. So foiling their activities might expose the person reporting to attacks. According to a journalist in Tumu,a2befb1369ca listeners who called into their radio show complained that they had concerns for their own safety.

Unavailable and inadequate data, meagre resources

Second, social accountability efforts were found to be hampered by a host of logistical and operational problems. A basic problem was unavailable or inadequate data. Because data is central to monitoring the implementation of the programme and demanding accountability, data lapses rendered their work extremely difficult. The red tape often associated with accessing any service from the agencies of state made this problem especially severe. This problem had, however, slightly improved in recent times following the CSO shift from confrontational strategies to those involving more dialogue. But the input dealers were not so inclined to be cooperative. A PFAG focal person in the Upper West Region described an ongoing struggle to get access to basic information from fertiliser retailers:

Yesterday I went to two dealers, it is ‘go and come, go and come’, but in data collection you need to be very patient and use your strategy to get the information you want. So I am still on them to pick my information. As I am talking to you now, this morning I went to them and they ask me to come around 4pm, that’s in the evening so I will go again. So picking information is difficultaaf8e083ea8e

Nonetheless, unreliable data was not necessarily an indication of an attempt to hide malfeasance. In the agricultural sector, and indeed across all sectors of the economy, lack of reliable data has long been recognised as a notorious problem.6543cb9a1a01 The situation was compounded by the lack of an overarching organisational framework for existing FBOs. Because not all farmers were members of PFAG, the group did not have accurate data on beneficiaries of the FSP, even at the district level. This seriously hampered its ability to effectively monitor the programme: ‘So normally the number of fertilisers that will come in we don’t have that knowledge, the number of farmers that have registered at MoFA, we might not have that knowledge, so it’s difficult for you to track’.9e847b51816f

This situation was compounded by the meagre resources with which the actors involved had to conduct their activities. Both SEND Ghana and PFAG provided minimal resources to members of their taskforce, but these were hardly enough to undertake the activities necessary to monitor the implementation of the programme. A national representative of PFAG67f75004cdd2 recognised this problem: ‘if you see a truck [loaded with fertiliser] moving and you have a motorbike, you can take one and quickly follow them. If we don’t have the logistics to do that, it presents a problem’. Similarly, the DCMCs were often unable to follow through with their action plans because they lacked resources. As a committee member complained: ‘when you need to make certain moves, you need to make certain contacts, you don’t have any budget line, you don’t have any source of funding to be doing all those daily activities’.ca27cdbc1357

Many of the committees also faced ‘free-rider’ problems in the performance of their day-to-day tasks. A DCMC member complained that ‘only a few of us are actually committed’.fc935b48749a There was a similar problem with community members. Because of widespread labour migration to urban centres in the south, community organisations needed to continually train new partners in the communities because of the resulting high turnover of trained volunteers.adc11d4c7418 This problem was also replicated in their engagements with public officials. Because officials were frequently transferred between duty posts, building relationships became an uphill task: ‘Mr A did not hand over properly and inform Mr B what we’re dealing with and so we have to start all over again’.53d6ab22627b

Public officials benefit from abuse of FSP

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, the socio-political context constrained the potential of social accountability initiatives. The underlying factor was that a variety of actors stood to benefit from the abuse of the FSP. These included public officials (including border security), who colluded with smugglers and local political leaders who used the programme as a vehicle to reward the ‘party faithful’. There was also little trust in the security agents stationed at various checkpoints and along the borders, because they did not seem very interested in apprehending smugglers. Many smugglers were able to easily pass through checkpoints.457aba2d980d Moreover, some border security officials did not follow up on tip-offs they received. Worse, when community members impounded trucks loaded with fertilisers, the case was not always handled transparently:

… But as I said, at the end of the day, where is justice? Where is the rule of law? What is the punishment to the smugglers? Who are the people involved? What is the source of that fertiliser? Where is it coming from? Who is checking it? We cannot know4d40ae064c67

Sometimes the number of days it takes to get responses to the feedback we give them also presents a challenge, it can dampen your spirit, when you say you apprehended…Let me give you one example. One of our guys at Tumu apprehended one truck full of fertiliser that they were going to smuggle. And then he called the police that this is what is happening. The police came and took the truck to the police station and said they will investigate the issue. The next day when he came, the truck had gone. You get it? When something like that happens, you feel relaxed [reluctant] to do anything because you know it will not end anywhere…. The security agencies, I think there isn’t commitment when it comes to the smuggling issue. I think when there are [media] reports of smuggling that’s when they pretend to move into actiondcf2640dd834

They are also able to beat the security network to smuggle input to neighbouring countries. Sometimes the securities also try to get ‘customers’ who will give them their share of money anytime inputs are smuggled. They try to work their way through from the top, so when they get to the bottom, it becomes a problem for us because the bottom would not have the capacity to handle issuesb0c82209fb4b

At other times, CSOs received information that the police had arrested smugglers carrying a certain amount of fertiliser, but they faced problems in their attempts to independently verify the exact details with the police themselves. And worse, they almost always never got to know the real culprits involved. This apparent shielding of smugglers frustrated the CSOs’ work:

You will never hear the results of that problem and that is an issue we need to deal with, because we have to make sure that those who are behind the smuggling of the fertilisers [are punished] so that those who do that will not do that again. Those are the challenges that we’re facing.5fd6a42f4995

This inversion of responsibility definitely affected the morale of community members involved in the fight against smuggling. As one journalist said, ‘People feel like the police, the immigration, the customs, they have a bigger role to play to protect this commodity … So their apparent disinterest dampens the spirit of community members who volunteer information or participate in monitoring activities’.e42fbd56252c

Yet, ultimately, respondents believed that the buck stopped with political leadership, specifically national-level government officials. And therein lies the problem, because as a PFAG focal person insisted,9f1196616b41 despite the effort his committee put in, ‘the problem can only go down if the government is serious about it’. In the same vein, a high-level official of a CBO said that from their engagements with various actors (including journalists, traditional leaders, FBOs, and local MoFA officials), one common and key point highlighted by all stakeholders was the argument that ‘It is only the government who can stop the act’.c828166571d5

Far from intervening to curtail smugglers’ activities, it appeared to respondents that political actors actually encouraged these acts. For one, party members affiliated with the government seemed to be benefiting disproportionately from the fertiliser distribution. Similarly, when trucks belonging to persons affiliated to the government were intercepted, they were able to use their political connections to escape any consequences. As described by a PFAG focal person,781d33585ba2 whenever any such arrest occurred, a call often came through to ‘please allow this car to go’. This would effectively bring an end to the matter. According to another respondent:

The challenge with this [situation] is that because these people belong to the main political parties in Ghana, they are not punished – even if you take action for them to be arrested. They have connections with the top people in the country, so they tend to go free3cdcc82d9f20

Moreover, it was no secret that local political leaders were involved in the abuse of the system. A farmer in Bolgatanga19f712d1d472 reported that he had once helped to stop a case of potential smuggling. However, once they had apprehended the culprit, he and other actors were made to understand that the smuggling was taking place with the authorisation of the assemblyman of the area. The involvement of some local government leaders like assemblymen and district chief executives complicated the efforts of those involved in social accountability:

We have not been successful at reducing or possibly eliminating the act of smuggling, because the very people who are in the best position to support that action are also directly involved in the act. People who are supposed to control those acts (security) are also refusing to do so.bb387d70b16a

In recognition of the crucial roles that politically connected individuals played in the operation of the programme, campaigners attempted to identify those with influence at the community level and involve them in ending the abuse. Yet these exercises can be equally frustrating:

We even had a meeting with the political party agents because we heard party agents are behind those acts. My secondary school mate, who is very active in one of the parties’ affairs, called me and asked why I was worrying myself by calling for the meeting. He told me that farmers have not complained of shortages of inputs and are also getting their share of money for selling input in Burkina Faso. He said I am wicked to them by trying to spoil their business. Some of them even tell farmers that if they don’t stop the ‘smuggling complaints’, the government may stop the programme.33bee32c4593

The open involvement of political agents in these abuses was found to be frustrating anti-smuggling efforts. For instance, some committee members were reluctant to report smuggling activities when the culprits were politically connected. This was because not only did they suspect that the case would not be pursued to its logical conclusion, but that the source of the information would be disclosed to the culprits: ‘It becomes like okay, you are now getting in the way of the party people, and so they will also make your life difficult’.47113d8d8612

Perhaps because of their apparent involvement in the abuse of the programme, government officials appeared reluctant to embrace workable solutions to the problem of smuggling. A national representative from PFAG claimed that attempts to secure introductory letters from national-level officials to give its activities a semblance of official legitimacy hit a roadblock after initial enthusiasm from the government. ‘We were doing it to secure introductory letters from the ministry to our farmers, so that once they intercept you and they report it to us, we can let them know that they have the authority to do so. We’re struggling to get that’.7b06c73a9990 But this was only one of several potential solutions they had floated with the government, which had not (as of the time or writing) generated much interest: ‘So for me, I think we have given the solution to government [of a] digital system, [like a] farmers database, revise the monitoring system, beef up the security, we should be able to get something [done] about it’.51737f1883cb

Given the government’s stalling over working with CSOs to find an effective solution to the problem of smuggling, the conclusion for many of these CSOs was to think that the government lacked the political will. This was a consequence of the fact that persons with ties to the government were benefiting from the abuse of the system. According to a CSO representative:

I conclude that the government is aware of the problems but are not prepared to support or implement the workable solution to ensure that the policy works well. Since their own people are involved, they are not ready to punish them. This discourages a lot of civil society organizations391c463db351

Finally, the politics of local accountability generated an atmosphere of mistrust. So deep was this mistrust that some members of anti-smuggling committees harboured suspicions about their own colleagues’ intentions. Sometimes, partisan affiliation got in the way of social accountability activities, even among members of task forces or monitoring committees. For instance, committee members would attempt to cast doubt on or otherwise compromise the credibility of information that might show their political party in a bad light. At the same time, considering the intensity of partisan sentiments at the local level, other committee members refrained from confirming the validity of information if they sensed that partisan interests were at stake. This eroded the confidence of both the community members who provided confidential information and otherwise committed task force members who should have acted on this information. According to a particularly disgruntled PFAG focal person:

People who feed us with information are also reluctant to give because you don’t know how that information will one day be used against you. And that’s the challenges that we face. I think our individual interest in Ghana is over 90% more important to the people than the national interest…. So these are the challenges that I personally have observed. I did advocacy that landed me in police cells22b26c6b293d

Thus, enthusiasm about the social accountability mechanisms’ successes was dampened by what appeared to be the ultimate limits of these endeavours. Given the legal limits of their interventions, there was a discernible sense of disillusionment from those actors who were engaged in social accountability. This had resulted in some communities entirely circumventing the law and resorting to unilateral actions, including vigilante justice.

Conclusions and policy implications

The findings reported here reaffirm the importance of context for social accountability. Social accountability interventions in the implementation of Ghana’s Food Subsidy Programme have helped reduce smuggling, improved the programme’s operational design, and have increased citizens’ awareness and participation in public affairs. These results have been possible because of the existence of a loose coalition of CSOs committed to anti-corruption activism and reform. At the same time, because these organisations are dependent on the cooperation of public officials, a conciliatory approach to engagement now ensures greater cooperation from public officials.

However, this dependence on goodwill comes with its own limitations. These include intentional delays from duty bearers who could, and often do, merely put up an appearance of compliance. Meanwhile, social accountability actors confront serious obstacles, including logistical constraints, the personal costs of involvement in social accountability initiatives, and lack of legal backing. The obstacles are rendered even more formidable due to the complicity of political agents, public officials, traditional leaders, and community members in the diversion of subsidised fertilisers.

The social accountability initiatives described in this paper could have a potentially transformative impact on the fight against corruption in Ghana if they were able to overcome these obstacles. In particular, the connection between social accountability and horizontal accountability mechanisms must be strengthened. The weak connection between these mechanisms is an outcome of the interaction between the country’s competitive clientelist political settlement and the social realities of political bargaining and local-level social negotiations. As discussed above, the constitutional arrangement that vests so much power and discretion in the hands of the presidency undermines state institutions’ autonomy, while encouraging executive interference in their functions. For instance, the executive’s ability to appoint and dismiss heads of state agencies, coupled with the fact that these agencies rely on the government for operational resources, means they are beholden to the incumbent.

Even with robust horizontal mechanisms, bottom-up accountability initiatives remain vulnerable to local-level struggles and negotiations that often act against anti-corruption activism. The FSP provides many opportunities for political elites to engage in rent distribution. Indeed, the original introduction of the subsidy in 2008 cannot be entirely divorced from the pressure to win over voters in the elections that were held later that year. Moreover, once the policy was in place, there was pressure to maintain it – even though it was initially meant to be a temporary measure in response to the food crisis. The programme has also been used by politicians as an instrument to sway voters by manipulating the distribution of the subsidies for electoral gain.102a9f221a10 The fact that these dynamics have continued under the governments of both major parties points to the powerful logic of the underlying competitive clientelistic political settlement. Thus, effective results would require institutional interventions with strong state backing. Social accountability can trigger this process but cannot be used as a substitute.b263f795e1ed

Despite this, while social accountability by itself is no panacea, its ability to mobilise a coalition of anti-corruption activists and enhance of the relationship between citizens and their local governments provides an opening that can be effectively scaled up. This is consistent with new thinking about successful anti-corruption strategies, which recommends shifting from system-wide interventions to ones that target particular sectors where anti-corruption is bothfeasible and potentially high impact.9d350503687d

The Fertiliser Subsidy Programme meets both criteria. It has strategic importance because of its potential to contribute to poverty reduction and stimulate economic growth by boosting agricultural productivity. There is also a loose coalition of already highly mobilised actors in place, committed to improving implementation by supporting horizontal accountability institutions. But this would require an effectively targeted anti-corruption strategy and a strongly collaborative approach between social and state-level actors.

Recommendations for donors, government, and CSOs

One of the most important lessons from the last few decades of anti-corruption activities is that corruption cannot always be addressed by subtle changes in programme design. This is particularly relevant when corruption is systemic, forming part of the political logic of a given country; that is, when corruption is tied to the maintenance of political power. In such cases, reformers are left with two major routes for change.

The first involves targeting anti-corruption efforts towards sectors where effective anti-corruption strategies can be both feasible and have potentially high impact. Agricultural subsidies is an area that can potentially impact development outcomes, such as poverty alleviation, food security, jobs, and livelihoods.

The second route requires more systematic efforts. This is particularly relevant in contexts of systemic corruption linked to clientalistic political settlements. In such cases, social accountability and the role of ordinary people in affecting change is only one piece of a puzzle. The puzzle also requires institutional interventions backed by the authority of the state and other national and international actors. Donor governments can go some way towards catalysing such change by simultaneously supporting civil society and people’s participation, while ensuring policy coherence across the spectrum of their activities in each country. For example, effective action could involve harmonising trade policies, diplomacy, foreign policy, and development policy to leverage reform at the political level, while at the same time supporting civil society and the independent media through standard donor channels.

In addition to standard support for civil society, donors should also consider indirect approaches that build up the capacity of people to advocate directly for change. This could be support for education programmes where social studies and civic engagement is part of the curriculum.

Donors should leverage their influence with national governments to ensure government–CSO cooperation in order to reduce the influence of potential detractors to reform. This can be done by:

- Incorporating social accountability initiatives, such as the PFAG taskforce, into standard monitoring and evaluation (M&E) activities. In particular, donors should prioritise CSO initiatives that have exhibited a track record of uncovering and helping to curtail diversion of resources.

- Using their influence with a broad range of national stakeholders to facilitate sustained collaboration between CSOs and horizontal accountability institutions. This can be done by supporting regular forums/workshops, where representatives from civil society and formal agencies can work together to resolve obstacles to effective anti-corruption and how to overcome powerful detractors.

Governments wishing to increase fertiliser usage through subsidy programmes should include control mechanisms, both formal and citizen led, to reduce the scope of political agents and public officials cause disruption. This can be done by strengthening connections between civil society-led accountability initiatives with horizontal accountability mechanisms; for example, by formalising citizen feedback into programmes.

CSOs, meanwhile, should be aware of the existence of informal norms and social practices that support or promote corruption acts. As such, they must exercise caution when selecting social accountability partners. In this regard, donors, CSOs and governments must devote attention to understanding the social milieu in which anti-corruption is undertaken. There is as yet very little that is known about how communal norms and expectations shape perceptions of various types of corruption in Ghana and other West African countries. Such an understanding is crucial to designing effective anti-corruption interventions.

- Fox 2015.

- Teye and Torvikey 2018.

- ISSER 2019; GSS 2019.

- ISSER 2019.

- 2015.

- GSS 2019.

- 2019: 11.

- Amundsen 2019: 6–7.

- Amundsen 2019.

- Prebendalism is a political system built on patronage.

- Evans 1992; Lewis 1996.

- 2018: 2.

- Uberti 2015; Fox 2015.

- Khan et al. 2019: 8.

- Uberti 2020; Khan et al. 2019; Schatz 2013.

- Asante and Khisa 2019; Khan et al. 2019; Malena 2004.

- Rahman 2018.

- Fox 2015; Zúñiga 2018.

- McNeil and Malena 2010; Malena 2004.

- Melana et al. 2004; O’Meally 2013.

- Malena et al. 2004.

- Ahmad 2008.

- Joshi 2010; McGee and Gaventa 2010; Malena 2004.

- Melana et al. 2004; Lodenstein et al. 2013.

- Lodenstein et al. 2013.

- Bank 2003; Cornwall et al. 2000.

- Khadka and Bhattarai 2012.

- 2013: 3; see also Joshi and Houtzager 2012.

- Sberna and Vannucci 2013.

- Rodan and Hughes 2012: 367.

- Oduro et al. 2014.

- Arthur 2010; Botchway and Kwarteng 2018.

- Appiah and Abdulai 2017.

- Whitfield 2011.

- Resnick 2016; Appiah and Abdulai 2017.

- Larte Lartey 2020.

- Gyimah-Boadi 2002: 3.

- Druilhe and Barreiro-hurlé 2012.

- Kato and Greeley 2016.

- Banful 2011.

- Crawford et al. 2006.

- World Bank 2008.

- Benin et al. 2013; Druilhe and Barreiro-hurlé 2012.

- Banful 2011, 2009; Druilhe and Barreiro-hurlé 2012.

- Banful 2009; Benin et al. 2013.