Query

Please provide an overview of corruption and anti-corruption in Senegal, with a particular focus on public financial management.

Background

Following its first peaceful transition of power in 2000, Senegal became regarded as one of the most stable electoral democracies in Africa (Freedom House 2023). Although it fares well concerning rule of law and anti-corruption efforts in comparison to other countries in the West African region, challenges persist in the forms of corruption perpetrated by government actors and selective prosecution targeting political opponents (BTI 2024; Transparency International 2024; Freedom House 2023).

After attaining independence in 1960, Parti Socialiste (PS), the party of the first president Léopold Senghor, ruled Senegal for over 40 years. Following the moderate liberalisation of the party system in 1974, Parti Démocratique Sénégalais (PDS) emerged as an opposition force (BTI 2024).

The first peaceful transition of power occurred in 2000, after presidential elections, in which Abdoulaye Wade from PDS defeated the incumbent Abdou Diouf (BTI 2024). Wade came to power on promises to improve governance, and his first major reform was the introduction of a new constitution in 2001, which limited presidential terms in office to two. Although GDP growth rates during the most of his presidency were around 5%, higher than in most of the region, they were not enough to meet the needs of the growing urban population (BTI 2024). Coupled with democratic backsliding during his tenure, cases of grand corruption, and the development of an extensive patronage system, opposition to his presidency rose (Shipley 2018; Ndiaye 2024). After the constitutional court ruled that Wade was eligible to run for his third term, a wave of protests emerged and gathered around his opponent Macky Sall, who won the 2012 elections (The Guardian 2012; BTI 2022, 2024).

Macky Sall committed to curbing against corruption and introduced the economic reform programme called Plan Sénégal Emergent (PSE), which reorientated economic and social policy in the medium and long term, focusing in particular on strengthening governance and the rule of law (Ministry of Justice of Senegal 2021; Shipley 2018). However, according to Camara (2019), Sall’s transition to power in 2012 did not lead to significant change with regards to corruption as political favouritism in the allocation of public resources and politically motivated prosecutions persisted.

After serving two terms in office, Sall announced on 3 February 2024, the postponement of the presidential election scheduled for 25 February. Sall cited the necessity of preventing a new crisis over an ongoing conflict between the judiciary and parliament (Ndiaye 2024) arising from the PDS and the ruling Benno Bok Yakkar (BBY) coalition accusing two constitutional court judges of corruption (Ndiaye 2024). Allegedly, the BBY’s presidential candidate, Prime Minister Amadou Ba, bribed the judges to remove a political opponent, Karim Wade of the PDS, from the race (Ndiaye 2024). According to Ndiaye (2024), this was a fabricated constitutional crisis as the BBY believed that its candidate had slim chances of winning. Sall’s decision was met with public outrage, leading him to eventually permit the holding of the election on 24 March. The opposition candidate Bassirou Diomaye Faye, of Patriotes africains du Sénégal pour le travail, l'éthique et la fraternité (PASTEF), won the elections in the first round of voting with over 54% of votes ahead of Amadou Ba with around 35% (Al Jazeera 2024). Faye has announced his intention to break with past practices and to govern with transparency (Crowe and Ba 2024).

Extent of corruption

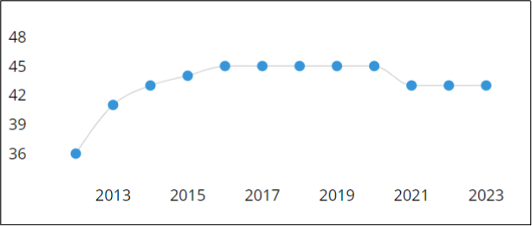

According to Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) for 2023, Senegal scored 43 out of 100, ranking it 93 out of 180 countries, and the regional average of 33 (Transparency International 2024; Banoba et al. 2024).c314c6e3bc6f Senegal reached its highest CPI score of 45 in 2016 and maintained it until 2020. Starting in 2021, its score decreased to 43 and remained the same in the following years, as shown in Figure 1 (Transparency International 2024).

Figure 1: CPI score for Senegal (2012-2023).

Source: Transparency International 2024.

Freedom House’s (2024) Freedom in the World report categorises Senegal as ‘partly free’. Its score was 67 for 2023, marking a continual decline from 2019 when it was 71 (Freedom House 2020, 2023). The report highlights that, while Senegal is one of the most stable electoral democracies in the region, a number of challenges persist, such as corruption in government, politically motivated prosecutions of opposition leaders and changes to electoral laws, which have contributed to reduced competitiveness of the opposition in recent years (Freedom House 2023).The latest Bertelsman Transformation Index (BTI) (2024) report notes that corruption allegations in Senegalese politics have always been common, but that in recent years these have attracted more controversy because they have led to the prosecution of members of the opposition or former ruling party. Indeed, the report notes that, although Senegal has official institutions mandated to counter corruption, the enforcement of anti-corruption legislation is viewed as politicised and selective. This is evidenced by the behaviour of the Cour de repression contre l’enrichissement illicite (CREI), a special anti-corruption court, that has primarily pursued political opponents or those associated with the former ruling party (BTI 2024).

The World Bank’s (2023) Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) for 2022 give Senegal’s control of corruption a score of -0.03, suggesting an improvement compared to 2012 (see Table 1).f6bcfdf7ad2c This indicator measures the strength of public governance based on perceptions of the extent to which public power is exercised for private gain (including both petty and grand corruption), as well as the capture of the state by elites and private interests (World Bank no date a). However, following an improvement in 2017, the score for the rule of law returned to the 2012 level in 2022, placing Senegal in the 43rd percentile rank (World Bank 2023). This indicator captures the perceptions of the extent to which agents have confidence in the rules of society and specifically the quality of contract enforcement, property rights, the police and the courts, as well as the likelihood of crime and violence (World Bank no date b).

Table 1. Senegal’s scores on the World Bank’s Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) in 2012, 2017 and 2022.

|

|

2012 |

2017 |

2022 |

|||

|

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

Score |

Percentile rank |

|

|

Voice and accountability |

0.00 |

49.30 |

0.32 |

57.14 |

0.16 |

54.11 |

|

Political stability |

-0.11 |

40.76 |

-0.06 |

43.81 |

-0.15 |

40.57 |

|

Government effectiveness |

-0.47 |

39.34 |

-0.37 |

38.57 |

0.00 |

52.83 |

|

Regulatory quality |

-0.11 |

50.24 |

-0.19 |

44.29 |

-0.30 |

41.04 |

|

Rule of law |

-0.28 |

46.95 |

-0.17 |

48.57 |

-0.26 |

42.92 |

|

Control of corruption |

-0.26 |

49.29 |

-0.11 |

52.86 |

-0.03 |

53.77 |

Source: World Bank 2023

The latest round of the Afrobarometer survey conducted in 2021/2023 across 39 countries in Africa suggests a mixed picture. For example, only 4% of Senegalese respondents consider corruption as one of the top three problems facing the country. By comparison, the average for the 39 surveyed countries was 11% (Dulani et al. 2023: 4).

However, some other findings add more nuance. For instance, when asked about corruption trends, 73% of respondents in Senegal thought that corruption increased over the 12 months prior to being interviewed, above the African average of 58% (Dulani et al. 2023: 6). Moreover, in the 2014/2015 survey, only 34% of respondents in Senegal thought that corruption increased over the 12 months prior to being interviewed. This means Senegal experienced the highest jump of all surveyed countries between the 2014/2015 and the 2021/2023 round (Dulani et al. 2023: 7).

An earlier survey conducted by OFNAC with the support of UNDP in 2016 found that the public sector was perceived as the most corrupt, next to public administration, the judiciary, the private sector, the national parliament, the media, and technical and financial partners. The highest perception of corruption within the public sector was recorded for public security (police and gendarmerie), followed by the health and education sectors (enda Ecopop 2021).

Forms of corruption

Corruption in Senegal takes various forms, but some are more consequential than others due to their reach into different institutions and the magnitude of money involved. These include grand corruption, clientelism and nepotism, and administrative corruption.

Grand corruption

Since 2000, there have been several prominent cases where the abuse of high-level power has occurred at the expense of the public interest.

Karim Wade, the son of former president Abdoulaye Wade who governed the country from 2000 to 2012, was implicated in a number of corruption scandals involving the misappropriation of public funds, as well as illicit enrichment (Châtelot 2016; Camara 2019). Shortly after Abdoulaye Wade assumed office, he appointed his son Karim as his personal adviser responsible for the implementation of major projects. In 2009, Karim Wade was appointed minister for state for international cooperation, regional development, air transport and infrastructure (Camara 2019). Through these roles, he established control over a wide array of lucrative sectors, earning nicknames such as ‘minister of heaven and earth’, and ‘Monsieur 15%’, the latter referring to the alleged commissions he was suspected of receiving from public contracts (Châtelot 2016).

In 2004, Karim was appointed as the president of the controversial National Agency for the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (ANOCI), which was tasked with organising the summit of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation in 2008 (Camara 2009). ANOCI faced criticism for insufficient transparency in awarding lucrative contracts to the Gulf states (France 24 2013). Furthermore, its legal status was considered ambiguous as its accounts were separate from the official budget, and therefore not subject to oversight by the Ministry of Economy and Finance’s controller (Beck et al. 2013: 236). Based on allegations of kickbacksd2521e41291a and other forms of corruption, MPs requested that Karim Wade appear before parliament to submit an audit report (Beck et al. 2013: 236).

In 2015, Wade was sentenced to six years in prison for corruption and fined US$230 million for illegal enrichment after a controversial trial at the CREI (BBC 2015; Freedom House 2017). The conviction was based on Wade’s inability to account for his personal wealth, reportedly held via a network of shell companies and bank accounts in various offshore locations (Shipley 2018). Some human rights groups criticised the court for violating due process, including prolonged pretrial detention (Freedom House 2017). He was released having served half of his sentence in 2016, following a presidential pardon (Châtelot 2016). Due to his conviction, Karim Wade was barred from running for president in the 2019 elections. This constituted one of a set of similar cases of targeting opposition politicians, raising concerns over politically motivated prosecutions (BTI 2024).

During Abdoulaye Wade’s presidency, there were other cases suggesting the misuse of public funds at top government levels. For example, the construction of a monolithic bronze statue in Dakar, the Monument de la Renaissance Africaine, caused controversy, not only on accounts of its price of US$23 million but also because Wade reportedly wanted to claim 35% of its future revenue on the basis of intellectual property as he claimed that he had designed the statue (Ph. B. 2010).

Former president Macky Sall’s younger brother Aliou Sall was also implicated in a high-level corruption case involving British Petroleum (BP) (Global Witness 2019). In 2015, the BBC published a story indicating that BP agreed to pay billions to a businessman in exchange for a stake in natural gas fields off the coast of Senegal (BBC 2019a; Global Witness 2019). Through his companies, the businessman, who had previously been accused of bribery and links to human rights offences, allegedly paid Sall consultant fees in the years leading up to the BP deal (Global Witness 2019; BBC 2019b). According to Global Witness (2019), there was a risk that Aliou Sall used his ties to the president to advance BP’s business interests. Following these allegations, Aliou Sall resigned as the head of the state-run savings fund (Caisse des Depots et Consignations) (BBC 2019b).

Clientelism and nepotism

During the administration of Abdoulaye Wade, ministries and public administration institutions were expanded to facilitate clientelism and nepotism. There were 41 ministries at one point, some of which were reportedly used to award his political allies and family members (Africa Confidential 2010; Camara 2019). These practices extended to the civil service. Although the recruitment process for civil servants nominally emphasises merit and competence during the selection process, there have been instances of less rigorous recruitment rounds such as those in 2012 and 2015, which provided opportunity for the regime to award its supporters in specific ethnic, political or regional groups (Shipley 2018: 6).

Nepotism was widespread during Abdoulaye Wade’s presidency. As discussed, his son, Karim Wade, held important political positions, including ministries that provided him control over lucrative sectors (Camara 2019). Furthermore, the president’s daughter, Sindiely, was appointed deputy director of the 2010 World Festival of Black Arts and Culture (FESMAN) (Wallis 2011; Camara 2019). Sindiely Wade was accused in a report by the state inspector-general of alleged embezzlement and mismanagement of funds in relation to FESMAN, but unlike her brother she was never prosecuted (Camara 2019).

Upon taking office in 2012, Macky Sall shut down some unnecessary state institutions, ordered audits of prominent government projects and published an audit of his own finances (Freedom House 2015). However, nepotistic practices continued. Examples include appointing Mansour Faye, the president’s brother-in-law, as the minister of hydraulics and sanitation in 2014, and Aliou Sall, the president’s brother, to the Deposits and Consignments Fund, a public sector financial institution, in 2017 (Camara 2019). Both became implicated in corruption scandals with Faye being accused of mismanaging the government’s Covid-19 food aid programme (Freedom House 2021) and Aliou Sall being implicated in the already discussed energy deal.

Administrative corruption

The latest round of the Afrobarometer survey, conducted in 2021/2023, offers some insights into the levels of administrative corruption in Senegal. For instance, 57% of respondents in Senegal reported that they had to pay bribes to obtain a government document. This constituted the second highest result in the survey, far above the average of 31% for the 39 surveyed countries (Dulani et al. 2023: 15).

Moreover, 73% of respondents in Senegal answered that ordinary citizens risk facing retaliation or other negative consequences if they report corruption, placing Senegal slightly above the regional average of 71% (Dulani et al. 2023: 19).

The 2015 World Bank Enterprise Survey found that the bribery incidence, referring to the percentage of firms experiencing at least one bribe payment request, was 11.1%, below the average for sub-Saharan Africa (19.7%) and below the global average of 13.3%. Moreover, this survey indicated that obtaining a water connection and construction permit were the administrative processes most vulnerable to corruption in Senegal, but both were still below the average for sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank 2015). Furthermore, only 6.3% percent of firms reported that they are expected to give gifts to public officials to get things done, which was significantly below the regional average of 24.9% and the global average of 15.9% (World Bank 2015). The World Bank plans to carry out another Enterprise Survey in 2024, meaning updated figures should be available soon. In 2019, the president of the national anti-corruption agency OFNAC painted a different picture, stating that firms that refuse to participate in corruption are deprived of government contracts (Pressafrik 2019).

Drivers of corruption in the public financial management cycle

Public financial management (PFM) can be defined as the set of systems and rules used to effectively manage public funds and spending (Lawson 2015; see also Duri 2021; Duri et al. 2023). The various stages of the PFM cycle include mobilisation, budget formulation, approval and implementation, budget dispersal, budget execution, internal oversight and external oversight (Lawson 2015; Duri et al. 2023). These stages are all vulnerable to the various forms of corruption affecting Senegal.

Conversely, it means that robust PFM systems can prevent corruption risks. For example, PFM reforms that ensure greater accountability for the use of discretionary funds reduce the chance that they are lost through corrupt practices (Jenkins et al. 2020).

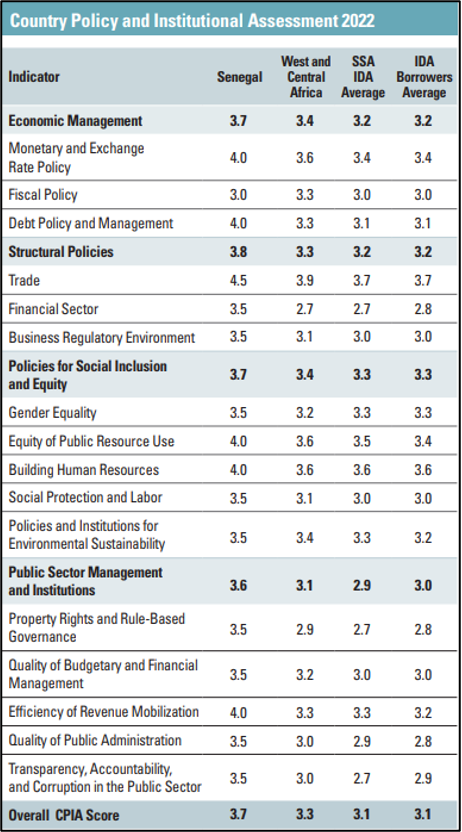

According to the World Bank’s Country Policy and Institutional Assessment (CPIA)5c6e7c4377d7 report (2023), Senegal fares comparatively well in the public sector management and institutions cluster.5b16f12d3cb7 For the cluster that concerns the quality of its budgetary and financial management,61903f20051b efficiency of revenue mobilisation,bc97ce417644 and transparency, accountability, and corruption in the public sector,9a3929e2a9af its score is slightly above the averages for the West and Central Africa, Sub-Saharan Africa International Development Association (SSA IDA3dc3b737c7bb) and IDA borrowers, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2: CPIA 2022 for Senegal.

Source: Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 105. (Measured on a scale from 0 to 5 where 5 is the highest score).

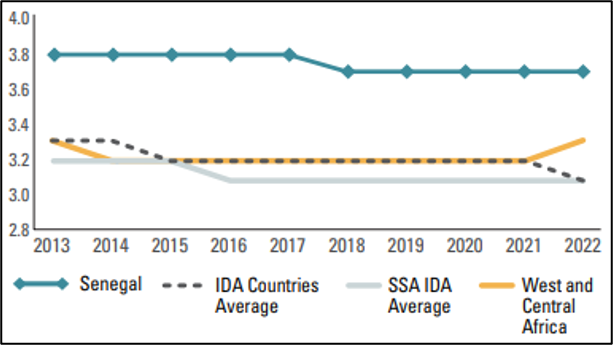

However, despite Senegal’s score being above regional averages, Figure 3 suggests that its score has been mostly stagnant over the last decade. The CPIA identifies several challenges present in countries in Africa, including Senegal, that can drive corrupt practices. For instance, one pressing issue relates to poorly targeted and costly fuel and electricity subsidies that benefit high income earners (Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 13). The report notes some efforts have been initiated in Senegal to reform inefficient subsidies (Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 13).

Figure 3: Senegal’s CPIA score and the regional averages between 2013-2022.

Source: Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 105

In its recent report, the IMF (2023) recognised Senegal’s efforts to strengthen its revenue administration and PFM, enhance the governance of public funds and improve the anti-corruption framework. The report also notes progress in the gradual elimination of treasury deposit accounts (comptes de dépôts) used by central government entities without legal personality (IMF 2023: 14). Moreover, steps have been taken to ensure some large public investments previously outside the normal budgetary process are now part of it, thereby strengthening internal controls (IMF 2023: 14).

However, some civil society organisations in Senegal have been critical of the IMF’s findings, noting slow progress in many key reforms, including those related to PFM, such as restricted access to tax data and insufficient data on public spending, particularly on public procurement (Forum Civil 2023). Important challenges persist in PFM’s vulnerability to corruption in Senegal, such as insufficient budget transparency and existing gaps in the public procurement legislation.

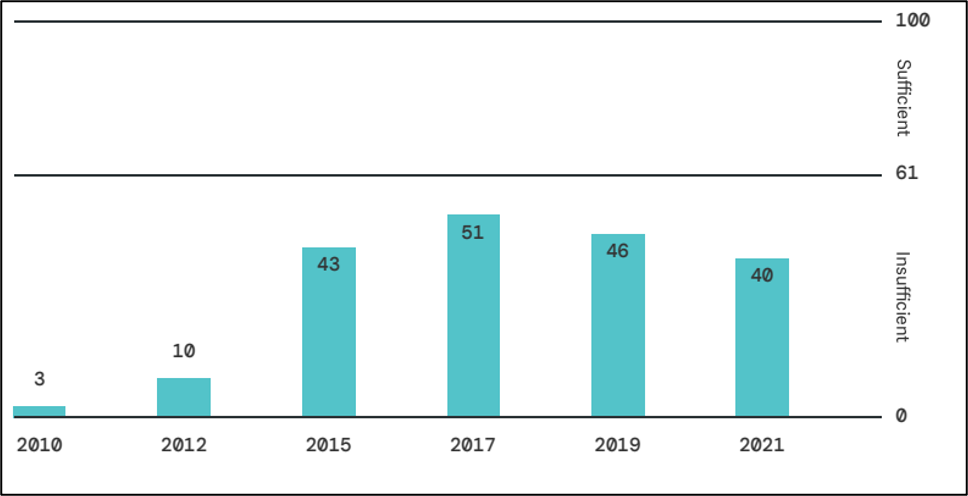

Insufficient budget transparency

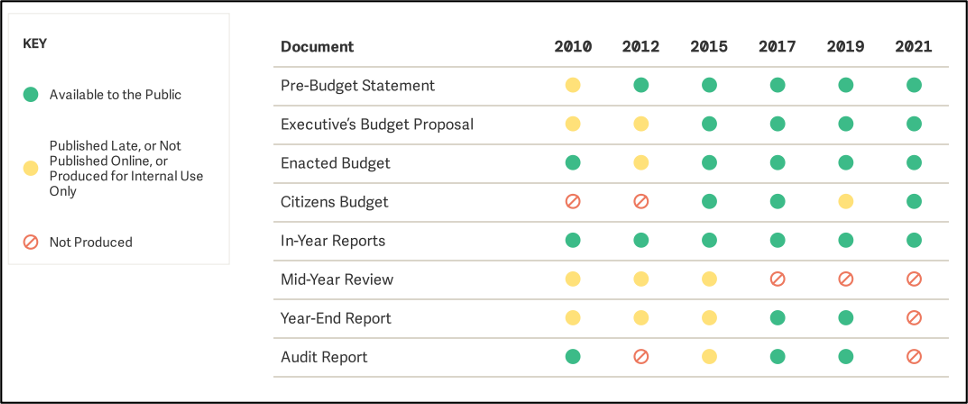

One major driver of corruption in the PFM cycle is a lack of budget transparency.0f74a823954d Senegal’s score of 40 in the Open Budget Survey (2021: 2) suggests that the country does not publish enough materials to support an informed public debate on the budget, although its score had been improving between 2010 and 2017 before declining again (see Figure 4). This score places Senegal 76 out of 120 countries, and below the global average of 45 (Open Budget Survey 2021: 2). Specifically, the key current issues were related to:

- the lack of public availability of mid-year reviews, year-end reports and audit reports

- citizens’ budgets, where budget information is presented in an accessible manner, were not comprehensive enough

- insufficient data in the executive’s budget proposal (Open Budget Survey 2021: 5).

Figure 4: Changes in the budget transparency score of Senegal.

Source: Open Budget Survey 2021: 3.

As shown in Figure 5, it is noteworthy that while year-end reports and audit reports were available in 2017 and 2019, they were not available in 2021. Moreover, while mid-year reviews were published with delays, or not online or produced only for internal use in 2010, 2012 and 2015, they were not produced in 2017, 2019 or 2021.

Figure 5: Availability of the key budget documents over the years in Senegal.

Source: Open Budget Survey 2021: 3.

The Open Budget Survey (2021) rated Senegal poorly for public participation in the budget process with a score of 4 out of 100. It noted that CSOs and media currently face difficulties in accessing information on public finances (OGP 2022). While specific laws, such as those related to public procurement and the budget, allow citizens to request information, Senegal still lacks a standalone law on free access to information (OGP 2022: 9), although a preliminary draft has been under discussion as of early 2024.

Furthermore, Senegal scores low on budget oversight in the Open Budget Survey (2021), including both oversight by the legislature and by the supreme audit institution. Specifically, Senegal’s national assembly provides limited oversight during the planning stage of the budget cycle and there is no oversight during the implementation stage. Moreover, Senegal does not have an independent fiscal institution (Open Budget Survey 2021: 9).

The latest available Public Expenditure and Financial Accountability (PEFA) (2020) report on Senegal (2020) noted that, while budgetary forecasts in terms of revenue were realistic, issues were identified in budget execution. The report notes that existing economic and administrative classifications are not sufficient to provide information on the purpose of budgetary expenditures (PEFA 2020: 146). Moreover, the budget documentation submitted to the parliament is not comprehensive as it does not cover financial assets or explanations of the budgetary implications of new initiatives and significant public investments (PEFA 2020: 146). Lastly, transfers to subnational administrations lack transparency and distribution criteria (PEFA 2020: 146-147).

Some of these findings are illustrated by a case related to the Covid-19 pandemic. In 2022, the court of accounts (cour des comptes) released a report on expenditures made in 2020 and 2021 from the ‘response fund against the effects of COVID-19’, which totalled over €1.1. billion, financed by donors and the state (Africa News 2022). The report flagged overbilling and misappropriation of the public fund, resulting in a loss of around €10 million (Gerth-Niculescu 2023). For instance, the report found evidence of overbilling the price of rice purchased and distributed to the poorest segments of the population, resulting in a surplus invoiced to suppliers amounting to F.CFAcba2f8fcb838 2.7 billion (app. €3.8 million) (Cour des Comptes 2022: 101).

The report also found instances of aid and relief being delivered to the same beneficiaries multiple times by the Ministry of Women, Family and Children (MFFGPE). Namely, analysis by the court of accounts found that people with same first and last names and identical ID numbers, and sometimes same addresses, received aid multiple times in different amounts (Cour des Comptes 2022: 113). Finally, the court of accounts also identified that many invoiced companies had neglected to pay VAT for public contracts tied to the fund (Cour des Comptes 2022: 91), which could be indicative of collusion to evade taxes.

The court of accounts asked the Ministry of Justice to open investigations against at least ten people, including ministry officials involved in the alleged mismanagement of the fund (Africa News 2022). The IMF’s (2023: 13) recent report noted that, following the publication of the court of accounts’ report, the authorities implemented an action plan to rectify the identified flaws in the PFM, and criminal proceedings have been launched against individuals and companies involved in the misappropriation of Covid relief funds.

Public procurement risks and gaps in legislation

Senegal’s public procurement framework is weakened by a reported lack of enforcement and the fact that some key sectors are outside the scope of legislation.

The court of accounts found in its recent report on Covid-19 spending that, even after the expiration of regulations which allowed public procurement to be conducted without applying the public procurement law due to Covid-19, the law was still not consistently enforced (Cour des Comptes 2022: 72). A number of health-relevant procurement contracts were issued by different institutions without following the law (Cour des Comptes 2022: 72:76), including to companies that lacked the necessary sectoral experience (Cour des Comptes 2022: 75). For instance, a company secured four contracts to supply PPE equipment, despite its main activities being land, air and maritime transport, according to Senegal’s company register (Cour des Comptes 2022: 75).

Legislative amendments to the public procurement code made in 2022 resulted in removing critical public sector energy companies from the scope of this legislation (Seneplus 2022; Baldé 2023). Specifically, the amendments ensure that public companies responsible for the application of the petroleum policy, exploration, exploitation of petroleum resources and gas, refining and marketing of oil and gas products, construction, operation and maintenance of transport infrastructure and distribution of natural gas, production, transport, distribution of electrical energy, can all acquire goods, equipment and services without applying the procedures provided by the public procurement code if they meet conditions specified by a joint order from the minister responsible for finance and minister responsible for energy and are approved by the body responsible for regulating public markets (Journal Official de la Republique du Senegal 2023: 82). While the official justification for these changes was improving efficiency, the risks of undermining transparency in some of these lucrative sectors, which may drive corrupt behaviour, are evident (Baldé 2023).

Moreover, procurement related to national security emanating from the presidency or from the ministries of armed forces, health and interior can also be exempted from competitive tender requirements (ITA 2023).

These gaps contribute to corruption related risks in public procurement processes. Audit reports from the court of accounts regularly identify issues such as the lack of transparency, failure to announce tender calls on time and inadequate post-award monitoring (Cour des Comptes 2022). The national regulator for public procurement, ARMP, in its audit reports, cites various irregularities discovered in public procurement processes, including collusive practices, lack of transparency, ignoring official procedures and misappropriation of funds (e.g. Osiris 2016; ARMP 2022). Furthemore, bribes and other informal payments are reportedly common to facilitate contract awards (GAN Integrity 2020).

In Senegal, politically connected companies are frequently favoured for public procurement tenders (Development Gateway 2017; Shipley 2018). For instance, the national anti-corruption agency OFNAC (OFNAC 2022) reported alleged conflicts of interest and violations of the public procurement code in a case involving the multinational retailer Auchan Group, a company called Setam and local authorities from the city Mbour. A complaint by the CSO Forum Civil alleges that a part of the land belonging to Caroline Faye Stadium was granted to Auchan Group to build a store without following all the necessary procedures, such as obtaining the prefect’s approval (OFNAC 2022). Moreover, the complaint notes that the Auchan Group transferred F.CFA 50 million (around €76,000) into the account of an entrepreneur managing the company Setam, who was simultaneously a departmental adviser, although these funds belonged to the municipality of Mbour (OFNAC 2022: 59). Following the investigation, OFNAC found that the award of the construction contract without prior competition to Abdou Salam Ndiaye, the manager of Setam and simultaneously a departmental adviser and the brother of the municipal councillorOumy Sylla Ndiaye, indicated favouritism (OFNAC 2022: 59-60).

Another compliant was submitted to OFNAC in relation to anomalies in administrative accounts of the commune Faoune. Despite projects being unfinished, costs were recorded in the commune’s accounts for completed works (OFNAC 2022: 58-59). The complaint alleged that this was facilitated by the lack of a procurement commission and a procurement unit, which were supposed to exist based on the stipulation in the public procurement code. During the investigation, OFNAC found evidence of a violation of the public procurement code and forgery, among other offences (OFNAC 2022: 58-59).

A recent report from ARCOP (Autorité de Régulation de la Commande Publique) (2023) suggests the need to change public procurement regulations to exclude elected political officials from participating in public procurement due to conflict of interest.

Main sectors affected by corruption

Police and military

Survey evidence and investigative journalism research suggests that corruption is present in both the police and military, although arguably less so than in most other African countries.

According to the Afrobarometer survey conducted in 2021/2023, 21% of respondents in Senegal believe that most or all of the police are involved in corruption, which is significantly below the average of 46% for the 39 surveyed countries (Dulani et al. 2023: 11). Moreover, the perception of police corruption improved by 9 percentage points compared to 2014/2015 (Dulani et al. 2023: 12). In general, the law enforcement agencies in Senegal are recognised as being professional and dynamic compared to regional counterparts (Organised Crime Index 2023).

However, bribery among traffic police is reportedly a common practice (Niasse-Ba 2018). A local BBC journalist said drivers often pay bribes for minor traffic violations to avoid serious sanctions (BBC 2016). Further, organised crime, particularly drug trade, is reportedly facilitated by corruption in border agencies and the police (Shipley 2018).

With regards to the military, there was a case of a bribery scheme organised by some members of the gendarmerie, which is part of the Ministry of Defence (Laplace 2018). Reportedly, these bribes were collected by the gendarms in charge of road checks and then placed in a fund opened in the name of a unit, without any legal basis (Laplace 2018).

OCCRP reported on the case of arms contracts issued by the Ministry of Environment that suggests evidence of inflated prices and low competitiveness in the sector (Omeje and Barkallah 2022). Namely, the said ministry signed a deal to purchase US$77 million worth of weapons from a little-known local firm, which was set up only some months earlier (Omeje and Barkallah 2022). The contract was rerpotedly facilitated by businessman Aboubakar Hima, suspected of siphoning millions from inflated arms deals in Nigeria and his home country, Niger, and a former employee of Israeli arms dealerGabi Peretz who was alleged to have offered a €300 million credit line to the Senegalese military (Omeje and Barkallah 2022; Africa Intelligence 2022).

Judiciary

The literature indicates that the justice sector in Senegal is vulnerable to corruption and government pressure, manifesting as politically motivated prosecutions and selective implementation of justice (Shipley 2018; Kanté 2021; US Department of State 2022; Ndiaye 2024; BTI 2024). In his 12-year tenure in office, the former president Macky Sall faced criticism from political opposition leaders and civil society representatives for using the judiciary to settle political scores. Prominent Senegalese figures including academics, writers and journalists, called on Sall to take steps to ensure the independence of the judiciary (Banoba et al. 2024; RFI 2023).

Freedom House (2023) notes that one major issue is the president’s control of appointments to the constitutional council, the court of appeals and the council of state. Moreover, the higher council of judiciary, which recommends judicial appointments to the executive branch, is headed by the president and the minister of justice, which negatively affects its independence (Freedom House 2023).

Similarly, BTI (2022, 2024) points out that the current institutional setup gives too much power to the president, as careers largely depend on it, and the judiciary grapples with corruption, underfunding and understaffing.

Lower level government administration

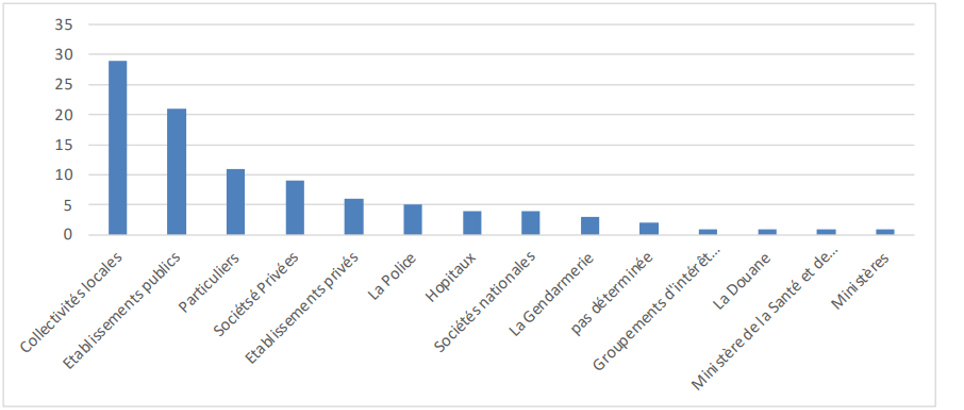

According to OFNAC’s annual report (2022), the most corruption related compliants made during 2021 were related to local government authorities, followed by public institutions (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. Complaints by the type of authority in Senegel in 2021.

Translations for Figure 6: collectivités locales – local communities, etablissements publics – public establishments, particuliers – individuals, sociétsé privées – private companies, etablissements privés – private establishments, la police – police, hopitaux – hospitals, sociétés nationales – national societies, la gendarmerie – gendarmerie, pas déterminée – not determined, groupements d'intérêt économique – economic interest groups, la douane – customs, ministère de la santé et de l'action sociale – ministry of health and social action, ministères – ministries)

Source: OFNAC 2022: 45.

There have been investigations of alleged corruption at lower government levels. For example, OFNAC (2022) reported that it received a complaint against the mayor of the community of Darou Khoudoss-Mboro, Magor Kane, with regards to an alleged lack of transparency in the collection of municipal road taxes, financial discrepancies in the 2018administrative account and unjustified real estate assets, among other issues (OFNAC 2022: 55). Following an investigation, OFNAC (2022: 56) found evidence of various offences including forgery, embezzlement of public funds and illicit enrichment.

The former mayor of Dakar, Khalifa Sall, was sentenced to five years in prison in 2018 after being accused of embezzlement of public funds (France 24 2018). Several opposition figures and human rights activists alleged that this was a politically motivated prosecution (US Department of State 2017). A year later he was pardoned by the then-president Macky Sall258427c77827 (France 24 2019). However, the constitutional court later ruled that Khalifa Sall was ineligible to run and challenge the incumbent Macky Sall in the presidential election in 2019 due to his previous conviction (Freedom House 2023).

Legal and institutional anti-corruption framework

International conventions and initiatives

Senegal has ratified a number of conventions and treaties and joined several initiatives:

- Senegal joined African Peer Review Mechanism in 2003

- Senegal ratified the ECOWAS Protocol on the Fight against Corruption

- it ratified the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) in 2005

- it ratified the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption (AUCPCC) in 2007

- Senegal joined the Open Government Partnership (OGP) in 2018

Senegal’s first action plan submitted to the OGP for 2021-2023 committed to enhancing access to information and civic participation in budgets and public policies, among other goals. However, as noted in its second action plan (2023-2025), these two commitments, along with four others (out of 12) have not been achieved yet (Ministry of Justice of Senegal 2023).

Domestic legal framework

The key pieces of legislation for countering corruption in Senegal are:

- the criminal code, which criminalises corruption

- the Uniform Act No. 2004-09 of 6 February 2004 on countering money laundering (United Nations 2017)

- a 2014 law requires asset disclosures to be made by the president, cabinet members, top national assembly officials, and the managers of large public funds (Freedom House 2018).

Senegal has made some efforts in improving its budget transparency, through:

- the Law No. 2012-22 of 27 December 2012, transposing WAEMU Directive No. 01/2009/CM/WAEMU on the Code of Transparency in Public Financial Management, which sets out principles for ensuring transparent, efficient and optimal management of public financial resources in the community space

- making the budget more accessible to citizens through a multi-stakeholder framework for budget monitoring (Ministry of Justice of Senegal 2021: 6)

- the entering into force of Organic Law No. 2020-07 on the Budget Acts, which reformed Senegal’s budgetary system, as the budgeting process changed from the logic of means to the logic of performance, with the results-based management as a backdrop (Ministry of Justice of Senegal 2021: 7)

In addition, a public-private partnership (PPP) law entered into force in 2021, and the public procurement code was amended in 2022 with the decree no. 2022-2295 of 28 December 2022. The amendments introduced several improvements, such as introducing sustainable development objectives and encouraging the participation of small and medium-sized enterprises (Chambers and partners 2024).

Institutional framework

ARMP (Autorité de Régulation des Marchés Publics)

ARMP, the national regulator for public procurement, is an independent administrative authority created in 2006, made up of the Regulatory Council, the Dispute Resolution Committee and the General Direction (ARMP 2022: 7). ARMP ensures regulation of the public procurement system by issuing opinions, proposals or recommendations. It also carries out investigations, implements independent audits, issues sanctions for identified irregularities, among its other authorities (ARMP 2022: 7).

According to its recent report, ARMP (2022: 30) audited 117 contracting bodies in 2021, which awarded 7,629 contracts, of which a representative sample of 3,361 was subject to random auditing.

Court of accounts (cour des comptes)

The court of accounts is the supreme audit institution in Senegal, which conducts audits of government bodies. Its responsibilities include judicial control of the accounts of public accountants, the control of the execution of finance laws, the control of the para-public sectorand sanctions for mismanagement (Cour des Comptes no date).

Although the institution publishes annual reports on its website, it appears to do so with significant delays; at the time of writing this Helpdesk Answer (March 2024), the latest available annual report was from 2017. The court of accounts publishes other types of reports on its website, such as thematic reports.

OFNAC (L’Office National de lutte contre la Fraude et Corruption)

OFNAC is the primary anti-corruption institution in Senegal. It is an independent administrative authority established in 2012 with the goal of preventing and countering fraud and corruption, strengthening fiscal transparency and promoting integrity in the management of public affairs (PPLAAF 2018). It has the authority to initiate its own investigations (Ministry of Justice of Senegal 2021: 7).

Following the adoption of the Law No. 2014-17 of 02 April 2014 on the declaration of assets, OFNAC was authorised to receive asset declarations from holders of public authority, elected officials and senior civil servants, who manage a budget equal to, at least, F.CFA1 billion (approximately €1.5 million) (Ministry of Justice of Senegal 2021: 7). The summary of findings on compliance with asset declaration obligations is published in OFNAC’s annual reports (eg OFNAC 2022: 30-36).

Efforts are reportedly underway to strengthen the powers of OFNAC and improve the asset declarations framework (IMF 2023: 60).

Financial judicial pool (Pool judicaire financier - PJF)

In 2023, the court for repression of illicit enrichment (CREI) was overhauled as, in 11 years of its existence, it had only tried two accused persons, the opposition figures Karim Wade and Khalifa Sall (Le Point Afrique 2023). This body has been widely criticised for other important reasons as well, considering that it failed to guarantee the rights of persons it indicts (FIDH 2014).

CREI was replaced by a so-called financial judicial pool (PJF), which includes a prosecutor’s office competent on financial crimes. With the adoption of Law No. 2023-14 on 2 August 2023, the PJF was established within the special high court (Tribunal de Grande Instance hors Classe) and the court of appeal of Dakar specialising in economic and financial offences and crimes (IMF 2023: 61).

Other stakeholders

Media

Senegal has a diverse media landscape, although it faces a number of challenges, including politicisation, incumbent bias of the state-owned national TV station, challenges with access to information, and others (RSF 2024; BTI 2024). Moreover, there are occasional cases of harassment and jailing of journalists (BTI 2024). For example, in 2020 a journalist was arrested after alleging that the gendarmerie had embezzled a portion of funds they had confiscated during a raid of a company suspected of corruption and made to appear in court on suspicion of making false allegations (MFWA, 2020).

Civil society

Senegal has an active and vibrant civil society, particularly on anti-corruption issues, but certain legal changes in recent years have threatened the NGO sector (Freedom House 2023; BTI 2022). BTI (2024) notes that segments of civil society have been vulnerable to co-optation by those in power.

With regards to anti-corruption efforts, several civil society organisations signed an agreement with OFNAC in July 2022 establishing cooperation in implementing the national anti-corruption strategy (Freedom House 2023). According to the Freedom House (2023) assessment in the Freedom in the World report, Senegal received a score of 3 out of 4 regarding freedom for non-governmental organisations, particularly those engaged in human rights and governance related work. The report notes that legislative changes to the penal code and code of criminal procedure of 2021 introduced some controversial provisions, allowing NGO leaders to be criminally charged for alleged offences committed by their organisations (Freedom House 2023).

CSOs active in the field of anti-corruption include:

- The CPI ranks countries on a scale of 0 (highly corrupt) to 100 (very clean).

- Scores range from -2.5 to 2.5 (higher scores correspond to a better governance) (World Bank 2023).

- The term kickback describes a kind of bribe “where a portion of a contract fee from an awarded contract is returned to the person approving the contract” (Transparency International UK, n.d.).

- IDA is an arm of the World Bank Group that provides credit to the poorest countries (Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 105).

- This criterion ‘assesses the extent to which the executive, legislators, and other high-level officials can be held accountable for their use of funds, administrative decisions, and results obtained’ (Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 109).

- This criterion ‘assesses the overall pattern of revenue mobilization, not only the tax structure as it exists on paper, but revenues from all sources as they are actually collected’ (Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 109).

- This criterion measures ‘the extent to which there is (a) a comprehensive and credible budget, linked to policy priorities; (b) effective financial management systems to ensure that the budget is implemented as intended in a controlled and predictable way; and (c) timely and accurate accounting and fiscal reporting, including timely audits of public accounts and effective arrangements for follow-up’ (Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 109).

- However, it is worth noting that this cluster has the lowest score, compared to the other three in Senegal: economic management (3.7), structural policies (3.8), policies for social inclusion and equity (3.7), and public sector management and institutions (3.6) (see Figure 2).

- The CPIA is a diagnostic tool used to capture the quality of a country’s policies and institutional arrangements on an annual basis. The tool was first developed and employed in the mid-1970s and has been periodically updated and improved ever since. It scores countries on 16 criteria, grouped into four clusters (economic management, structural policies, policies for social inclusion and equity, and public sector management and institutions). There is a complementarity of the CPIA with the PEFA framework, considering that CPIA guidelines refer to PEFA reports as a source for scoring specific PFM related criteria (Office of the Chief Economist for the Africa Region 2023: 109-113; PEFA no date).

- The Open Budget Survey (2021: 2) index assesses the online availability, timeliness and comprehensiveness of eight key budget documents using 109 equally weighted indicators and scores each country on a scale of 0 to 100. A transparency score of 61 or above indicates that a country is likely publishing enough material to support an informed public debate on the budget.

- F.CFA is the abbreviation used for the West African CFA franc which is the currency used in eight West African states, including Senegal.

- Despite sharing a surname, Macky Sall and Khalifa Sall are unrelated.