Query

I am looking for existing documents that tell the story of countries that have significantly succeeded in curbing corruption.

Caveat

The following examples in this paper list only illustrative success stories as reported in the public domain. The list is not meant to be exhaustive. The anti-corruption success examples do not include the ones found in an earlier paper on Successful Anti-Corruption Reforms (2015).

Background

When it comes to understanding and debating the nature and consequences of corruption, as well as strategies for curbing it, there are substantive resources available. However, in terms of systemic evidence for “sustainable transitions away from endemic corruption and towards consistent integrity”, resources are far less (Jackson 2020: 1).

Johnston (2018: 51) states that, while the anti-corruption movement has witnessed success in certain areas including but not limited to making corruption a global issue and raising significant awareness to it by mobilising grievances against official exploitation and misconduct, “clear-cut, sustained reductions in corruption in diverse societies on the state level have been few”. One of the many ideas for re-thinking assumptions that Johnston (2018: 52) points to includes understanding what the “opposite of corruption might be and how we might build positive support that”.0cae7d355548 The following sections will touch upon some existing approaches in anti-corruption strategies and consider a few emerging ideas to create success in the area.

Importance of a theory of change

Despite considerable investment in anti-corruption interventions, often “mainstream approaches have not fully delivered” (Jackson 2020: 1). One explanation for such a scenario is a limited understanding of how change happens (Jackson 2020: 1; Mungiu-Pippidi 2015). Thus, even though anti-corruption interventions have “theories of action”, what is often lacking is a true theory of change which encompasses a plan on navigating and inducing reform changes in complex internal dynamics (Green 2017: 8; Jackson 2020: 1).

In Rethinking Corruption: Hocus-Pocus, Locus and Focus (2017: 21), Heywood opines on what may be going wrong:

- Viewing institutional reconfiguration solutions as “magic bullets” for anti-corruption. Heywood terms the trend as “hocus-pocus”. The author suggests that there ought to be a re-thinking of how we currently understand corruption, and consequently set up anti-corruption measures.

- Concentration on countries as the primary unit of analysis in academic research and anti-corruption advocacy, and not enough being done in understanding corruption as an increasingly transnational occurrence (“locus”).

- Heywood argues that there is insufficient disaggregation of different types and modalities of corruption outside of rudimentary binary divisions not fully appreciating the complexities of an increasingly transnational world (“focus”).

“You don’t fight corruption by fighting corruption”

Kauffman (2017) states the above-mentioned quote which surmises the essence of an indirect approach to curbing corruption (Jackson 2020: 7). The focus of indirect approaches is on introducing “feasible social and political reforms that may bring about control of corruption as a by-product” (Jackson 2020: 8).

In Transition to Good Governance (2017), Mungiu-Pippidi and Johnston examine 10 countries that successfully reduced corruption, and their findings showed that it was not always anti-corruption measures that explained this success. Their work finds that “structural aspects, such as political agency and modernisation of the state, play a significant role in determining whether anti-corruption efforts are successful or not” (see Zúñiga 2018).

State modernisation

Rooted in the “principal-agent”caa879e3f6a1 model, the dominating strategy in anti-corruption policies over the last three decades can be described as state modernisation. Such an exercise entails the state and other “associated social actors” creating and improving institutions and capacity to limit individuals’ discretionary powers, expand sanctions for misconduct and improve monitoring (Mungiu-Pippidi and Johnston 2017; Jackson 2020: 3). Modernisation also includes development of an anti-corruption system with clear laws and procedures, enforcement organisations and monitoring capacity. The implicit assumption in such an approach is that if “governance systems in more-corrupt countries come to look like those in less-corrupt countries, it becomes harder for corruption to prosper" (Jackson 2020: 3).

Thus, anti-corruption measures as a part of this paradigm includes setting up/strengthening anti-corruption agencies and audit institutions, delineating national anti-corruption strategies, reforming public financial management, ensuring whistle-blower protections, better procurement controls, and bolstering community monitoring and transparency measures. On the other hand, capacity could be strengthened through corruption risk management to identify and provide remedies for vulnerable areas and enhance law enforcement capabilities. In doing so, the vital area of focus would include bolstering the capability of key state institutions such as the police, judiciary, oversight institutions, parliament and local government, while simultaneously having bottom-up approaches that include supporting and enabling civil society actors to monitor corruption (Jackson 2020: 3-4).

Over a period of time, these tools deemed as “indispensable” in anti-corruption approaches have evolved to include “focus on sectoral mainstreaming, increased specialisation and refinement of legal tools, enhanced methods of external or social accountability, and the incorporation of technology and e-governance tools”.

Despite the widespread use of this approach in anti-corruption programming, the reason limited effectiveness is seen in the real world is linked to implementation deficits. Often the implementation challenge (which can manifest as a lack of independence for anti-corruption agencies, apparently strengthened oversight institutions being actually weakened), is perceived as another principal-agent problem. However, in reality the anti-corruption roadblocks stem from challenges of “collective action, power asymmetry, social norms, or the political economy of reforms” (Jackson 2020: 5).

Understanding context is key

Johnston (2018, 55) argues that “best practices” for anti-corruption interventions are elusive, since what works in one particular country may be ineffective/impossible or even “downright harmful” in another context. For instance, simply replicating the laws and institutions of successful countries without ensuring “solid social demand for reform, grounded in lasting social values and interests”, will be like “pushing on one end of a string”.

Thus, in designing measures to tackle corruption, what is needed are “better practices” that are adapted to the specific contexts in which corruption is embedded. Such practices include a deeper comprehension of sustaining anti-corruption efforts as well as outlining and tackling the possible anti-corruption opposition which can take root (Johnston 2018: 55).

Hough (2013: 29, 121), states that “unsurprisingly” there are no concrete answers when it comes to comprehending under what conditions a type of anti-corruption strategy works, nor are there any “one size fits all” interventions. However, if the governance context is understood, “then, and only then, will more specific anti-corruption policies have a chance” (Hough 2013: 121).

Diagnosing the problem is crucial to designing anti-corruption strategies, and the success of anti-corruption interventions depends on not just internal factors of project design and implementation but also the external environment in which they are implemented (Rahman forthcoming: 7). A few features that are known to affect such measures include the condition of the local accountability environment (Brautigam 1992: 21; Grimes 2013), rule of law in the context of operation (Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadašov 2017), extent to which the media is free (Brunetti and Weder 2003) as well as free and competitive elections for public office (Winters and Weitz-Shapiro 2013). In light of such detail, a thorough political economy analysis (PEA) could be helpful in mapping out the contextual realties of interventions.

Targeted/sector specific interventions

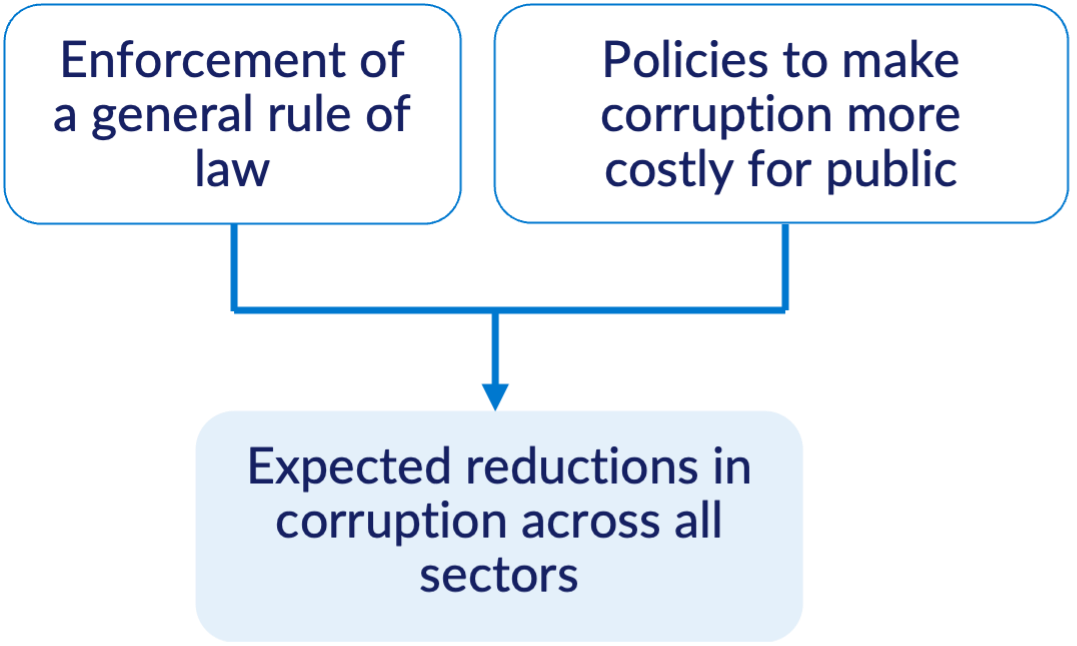

Khan, Andreoni and Roy (2019: 8) observe that most conventional anti-corruption strategies are usually based on a combination of methods to enhance the “enforcement of formal rules across the board, together with policies that seek to change the cost-benefit calculations of individual public officials in a context of asymmetric information”.

Figure 1: Conventional anti-corruption approaches (Source: Khan, Andreoni and Roy 2019: 8)

In developing countries, such approaches have not achieved adequate results because they consider these countries to be generally rule-following contexts with few infractions that can be potentially fixed with “improvements in good governance, transparency, and accountability”. In reality, “generalised rule-following behaviour is more or less absent” in most of these contexts. Moreover, it is not practical to immediately establish rule-following practices due to structural constraints, including the configuration of power in these societies (Khan, Andreoni and Roy 2019: 8). To tackle such challenges, the researchers identified four clusters for effective anti-corruption strategies (Khan, Andreoni and Roy 2019: 3):

- Aligning incentives: creating internal support for rule-following behaviour by creating developmental policies that benefit those organisations/stakeholders that have “some voice and bargaining power in society” (Khan, Andreoni and Roy 2019: 24, 25).

- Designing for differences: by incorporating anti-corruption measures that would be feasible for the wide variety of stakeholders in a given sector (Khan, Andreoni and Roy 2019: 32, 33).

- Building coalitions: anti-corruption efforts could benefit from having powerful organisations as allies (Khan, Andreoni and Roy 2019: 40).

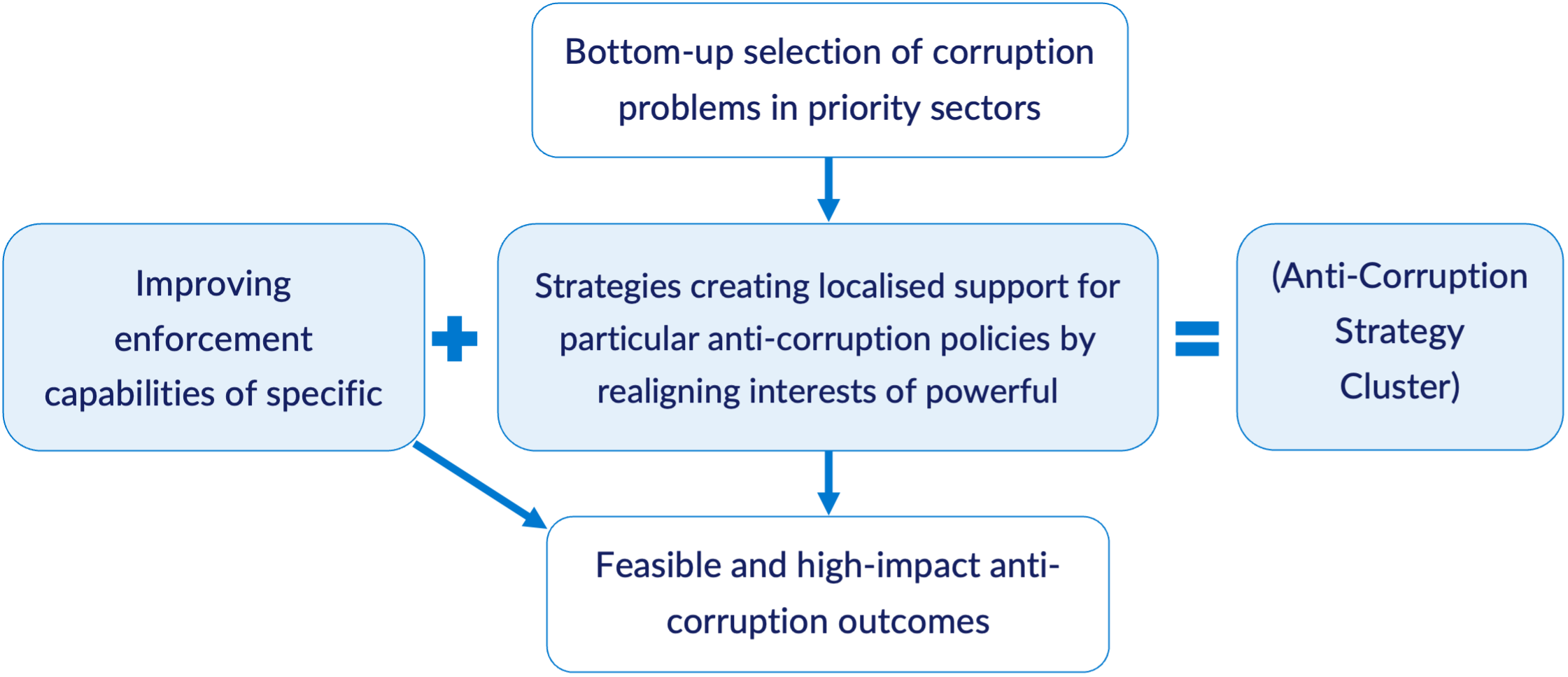

Uberti (2020) states that in low and low-to-middle-income economies, the main purpose of development practitioners ought not to be reducing “corruption across the board by establishing or strengthening a national legal-institutional framework for anti-corruption”. Instead, practitioners should “target their efforts to specific spaces (or ‘sectors’) where corruption is particularly damaging, and donor interventions are less constrained”. Such targeted responses ought to be “both feasible and high-impact” depending on the specific context of the country/sector (Uberti 2020: 12-18).

Figure 2: Feasible and high-impact anti-corruption strategies (Source: Khan, Andreoni and Roy 2019: 17).

Challenges faced and lessons learned

Tracing the impact of anti-corruption measures is difficult as it is challenging to precisely quantify corruption in the first place. Thus, when it comes to estimating the efficacy of specific anti-corruption interventions on the levels of corruption, the issue is additionally exacerbated by “challenges of causality and attribution”. This is primarily the case as separating a particular reform from other types of measures operating together is not an easy task. Likewise, anti-corruption reforms do not usually produce significant results in small intervals, while evaluations are often performed in a short timeframe following the intervention (Chêne 2015: 2).

Moreover, there are several lessons that development practitioners can keep in mind in designing and implementing anti-corruption interventions. For instance, apart from designing anti-corruption initiatives that are tailored to the specific context, robust integrity management systems at the donor end can help to keep projects on track and support with simultaneous monitoring, evaluation and learning to course correct if required (Rahman forthcoming: 6).

Given that there are no magic bullets or one-size-fits-all interventions, the success of anti-corruption measures is usually boosted by a blend of complementary (top-down and bottom-up) approaches and propelled by the interaction of several reforms operating simultaneously (Chêne 2015: 1).

When trying to strategise for anti-corruption measures in a given context, one must not forget that corruption successes can also be at a community/grassroots level. Moreover, corruption has a “disproportionate impact on the poor and most vulnerablec86ccad3030c, increasing costs and reducing access to services, including health, education and justice” (World Bank 2021). Therefore, to make anti-corruption efforts successful in practice, they ought to include the voices of those most affected.

Lessons from previous and ongoing anti-corruption projects could provide insights for enhancing effectiveness. For a detailed overview of the methodological challenges involved in measuring progress and the impact of anti-corruption as well as lessons drawn from successful approaches, please refer to Successful Anti-Corruption Reforms (2015).

Latest thinking on curbing corruption

A recent paper by Wathne (2021) surmises these findings:

- Corruption is not a “disease or deviation but a historical standard”. The goal of zero corruption has not been reached by any country, and it is not likely to be fulfilled any time soon either.

- Corruption is “complex and resilient”. The shift from a society with high levels of corruption to a low-corruption society is lengthy and non-linear. Consistent gradual improvements are also challenging to maintain.

- Across and even within countries, there are varying forms and degrees of corruption.

- A contextual understanding of the drivers of corruption and the broader political economy need to be considered when deploying anti-corruption measures.

- There is “no single blueprint”. Each context requires a customised mixture of strategies, mechanisms, and stakeholders to curb corruption.

- In contexts with systemic corruption, anti-corruption efforts ought to go beyond merely targeting individual “bad apples” and take a systems approach.

- While recognising that there is no one way of achieving success in anti-corruption, there are some potential success factors such as “collaboration and coordination, building trust, taking advantage of windows of opportunity, building and harnessing political will and citizen support for good governance, changing expectations, and reshaping the policy arena”.

- When designing anti-corruption interventions, flexibility, political responsiveness and contingencies for potential backlash ought to be considered.

- There are limitations to what anti-corruption measures can achieve by themselves. Even the role of donor agencies can be limited. The effectiveness of anti-corruption interventions often depends on the broader political economy, including the policy arena.

- Successful anti-corruption efforts by donors may require a more comprehensive approach that takes into account the transnational dimensions of corruption and employing a wide “whole-of agency, or even whole-of-government, approach”.

An anti-corruption intervention should…

- Be sufficiently anchored and led by local stakeholders, including powerful individuals where possible

- Be based on a strong theory of change, including and understanding of the complexity of corruption and anti-corruption

- Be based on a deep, contex-specific understanding of the drivers and enablers of corruption, as well as the wider political economy

- Draw on local knowledge, including marginalised voices

- Make use of the emerging anti-corruption literature

- Employ a tailored, multi-faced, multi-stakeholder approach

- Complement ongoing efforts and strategies

- Where appropriate, include or be complemented by non-aid levers, given the transnational nature of corruption

- Foster collaboration and coordination

- Build trust

- Contribute to addressing the underlying causes of corruption

- Contribute to a shift in an equilibrium

- Take on a high-impact bottleneck

- Be politically smart and feasible given the prevailing political settlement

- Set a realistic goal

- Employ a realistic time horizon

- Make use of windows of opportunity when they arise

- Anticipate unintended consequences and backlashes

- Contain an M&E plan that contributes to the anti-corruption evidence base and allows for continuous analysis and learning

- Allow for continuous adjustment while the intervention is underway

- Be implemented and funded by stakeholders genuinely committed to reform.

Source: Checklist for anti-corruption interventions (Wathne 2021:54).

Select anti-corruption success stories

As mentioned in the section above, context is key in designing and applying anti-corruption interventions. Success of a particular measure in a given context may not work in another and may not even work in the same context at a different period of time.

Moreover, as mentioned in the sections above, there are several methodological challenges involved in measuring progress and the impact of anti-corruption. Nevertheless, numerous evidence mapping exercises suggest that public finance management reforms and strengthening horizontal and vertical accountability mechanisms and transparency tools (such as freedom of information, transparent budgeting and asset declarations), among others can have an impact on controlling corruption (Chêne 2015; Menocal et al. 2015: 84-86). Social accountability measures and civils society organisations play crucial roles in reducing corruption (Menocal et al. 2015: 86).

For examples from these aforementioned areas please refer to Successful Anti-Corruption Reforms (2015).

The following success stories and methods of anti-corruption interventions are meant to be illustrative and not exhaustive. The following examples cover anti-corruption topics not included in the 2015 paper. They focus on curbing disinformation to enhance electoral integrity, anti-corruption initiatives at the local level and changing attitudes towards corruption, among others.

Access to information at the local level

Information on the work of local politicians, budget and expenditure, procurement and contracts can go a long way in supporting accountability and transparency measures. A study looking at “Access to Information in European Capital Cities” found that several eastern European capitals performed better at providing access to information than their equivalent cities from older democracies, which came as a result of the pressure for widespread information disclosure that originated from “unsatisfactory levels of corruption in their home countries”, as well as in the context of relatively new transparency laws.

|

⬤ Kyiv |

⬤ Madrid |

|

⬤ Prague |

⬤ Pristina |

|

⬤ Tallinn |

⬤ Vilnius |

|

⬤ Amsterdam |

⬤ Berlin |

|

⬤ Bern |

⬤ Bratislava |

|

⬤ Bucharest |

⬤ Lisbon |

|

⬤ Ljubljana |

⬤ London |

|

⬤ Moscow |

⬤ Oslo |

|

⬤ Riga |

⬤ Rome |

|

⬤ Skopje |

⬤ Sofia |

|

⬤ Athens |

⬤ Belgrade |

|

⬤ Chisinau |

⬤ Sarajevo |

|

⬤ Stockholm |

⬤ Yerevan |

Figure 3: ratings from the Access to Information in European Capital Cities report. Given the relatively small number of indicators, the report decided against creating a full ranking. Instead, they put the cities into three broad categories: Green (with a score of at least 75% of maximum points), Orange (50–74.9% points), Red (below 50% of points). (Source: Zajac, Šípoš and Piško 2019: 4).

However, the report cautioned that “not really any city… serve as a best practice for other cities” due to varying performances when measured against the study’s different indicators. Furthermore, there are some cities that may not have performed well overall but serve as “best practice” for some indicators. Thus, this speaks to the point on adopting “good practices” by learning from other contexts and customising it to a given milieu.

Some examples include:

- Stockholm uses photos, infographics, tables, explanatory text, among others to make its budget report on expenditure user friendly and easily digestible (Zajac, Šípoš and Piško 2019: 10).

- Bratislava and Prague publish contracts on a central register. Both have well-arranged systems of categorisation, but the former lacks a system of filtering and searching by keywords, periods or reference number, which is not the case for the latter (Zajac, Šípoš and Piško 2019: 11).

For further information please refer to: Access to Information in European Capital Cities (2019).

An example of making use of access to information at the local level comes from New Delhi, India. In 2005, some of the poorest residents of the city, with the help of a local NGO, made use of the then newly passed right to information law and discovered huge discrepancies in subsidised rationse64135081e3d being supplied by designated fair price shops as a part of the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS). It was found that 80% of the grain meant for distribution to the poor was being was being siphoned off and black marketed for personal profit. In light of these findings and pressure from local activists, the local government completely overhauled TPDS to ensure better access to food supplies for ration card holders (Burgman et al. 2007, 19).

Strengthening anti-corruption framework and institutions

In Taiwan, democratisation (in 1992) and the change in ruling parties (in the 2000s) lead to the passage of new laws and the reform of existing anti-corruption ones (Göbel 2015; 3). The reforms established a clear legal definition of what constitutes “corrupt” behaviour in accordance with international norms (Göbel 2015:3). The judiciary in these circumstances was professionalised and its independence was bolstered (especially after the change in the ruling parties). At the same time, anti-corruption agencies were significantly strengthened. While the “institutional configuration” of anti-corruption agencies is not perfect, these were considered “major achievements” for the country (Göbel 2015).

For further information please refer to: Anticorruption in Taiwan: Process-tracing report (2015).

On the other hand, since its inception in 2003, Indonesia’s Corruption Eradication Commission (Komisi Pemberantasan Korupsi), also known as KPK, gained national and international recognition for prosecuting high-level corruption. It was also lauded as contributing to the improvement of the country on Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI). However, in 2019, despite the opposition by civil society anti-corruption actors, an amendment to the anti-corruption law was passed (Transparency International 2021). This amendment has introduced significant changes to the institutional structure of the KPK, which curtailed its investigative and prosecutorial powers (Juwita 2021). For example, KPK now has a supervisory board, potentially affecting its independence, and its investigators are required to carry out their duties under the coordination and supervision of the police (Transparency International 2021). Such an example shows that success stories from the past can be undone.

For further information please refer to: Dismissals Following Controversial Civics Test Further Weaken Indonesia’s Anti-Corruption Agency KPK (2021).

Tax digitalisation to reduce corruption

Between 2001 and 2017, the revenue authority in Rwanda revamped its tax collection methods, improved staff capacity, enhanced information management, and introduced a substantial and continuous public education campaign to rebuild citizen trust in the system. The result of this campaign was that the country collected the same amount tax in three weeks in 2017 as it had collected in a year about 12 years earlier (Schreiber 2018). As a part of this overhaul, the Rwanda Revenue Authority (RRA) also introduced digitalisation across the tax collection process, which has significant anti-corruption benefits. For instance, digital payments reduce the likelihood of corruption through eliminating cash transactions, and e-invoicing promotes transparency (Rosengard 2020: 33, 37).

For further information please refer to: Tax Digitalization in Rwanda: Success Factors and Pathways Forward (2020) and A Foundation for Reconstruction: Building The Rwanda Revenue Authority, 2001–2017(2018).

Figure 4: Factors contributing to the success of the tax digitalisation process of the RRA (Source: Rosengard 2020: 20).

Curbing bribery in service delivery

Despite facing myriad corruption challenges, such as nepotism and cronyism, political corruption and illicit financial flow (IFFs) risks, Mauritius reports low levels of bribery in service delivery (Rahman 2019: 4-9). According to Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) 2019 Africa Report, only 5% of Mauritians paid bribes to access public services like education, healthcare, identification documents and safe water. This is in stark contrast when compared to an average of 28% across the 35 countries covered by the GCB 2019 research (Transparency International 2019).

Petty corruption was not always reported as being so low. For instance, in the past, even though Mauritius had “well-developed institutions, educated civil servants, and high levels of economic development” excessive red tape lead to citizens having to pay bribes to receive services without delays (Dreisbach 2017: 2). To counter this, the anti-corruption agency, despite not having high prosecution and conviction rates, drove change from 2009 to 2016. Between this period, the idea was to enable systemic transformation instead of punishing individual offenders. It is argued that this strategy purposely “sidestepped certain major concerns such as the influence of money on elections, but it did manage to reduce petty visible forms of graft” (Dreisbach 2017: 2).

Using a bottom-up approach, the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), involved government institutions in detecting their own particular corruption risks, creating solutions and monitoring their implementation. This enabled a sense of ownership and responsibility in institutions towards their anti-corruption efforts and motivated senior officials to further bolster effective integrity at the institutional level (Transparency International 2019).

For further information please refer to: Tackling Corruption from the Bottom Up: Decentralized Graft Prevention in Mauritius, 2009–2016 (2017)

Defending elections against disinformation

Disinformation, particularly through social media, has become an “increasing problem to electoral integrity and citizens’ trust in their democratic institutions” (Martin-Rozumiłowicz and Kužel 2019: 3). In such a scenario and given the background of the 2016 Russian state information influence attack on the US presidential election, the Swedish Civil Contingencies Agency, in the run up to the 2018 elections, began formulating methods to defend the integrity of the country’s electoral process. Instead of focusing on blocking the creation and spread of disinformation, the agency sought to develop the “resilience of institutions and society overall to withstand information influence activities”. Thousands of civil servants were trained, interagency coordination was organised, traditional and social media were coordinated with, public awareness was raised, and the digital information landscape was actively monitored. Despite one cyber-attack on the Swedish Election Authority website, the election went smoothly, and since then “the government [has] doubled down on the resilience-building approach for protecting the 2022 election” (LaForge 2020).

For further information please refer to: Sweden Defends Its Elections Against Disinformation, 2016–2018 (2020).

Similarly, between 2016 and 2020, the State Electoral Office in Estonia adopted a “network approach” by involving stakeholders from other government agencies, intergovernmental organisations, civil society, social media companies and the press to identify and monitor disinformation. They also worked with the press to correct false statements. A curriculum to help school students identify disinformation was also developed. While these efforts largely succeeded in countering disinformation, it also received criticism for curbing free speech and increasing censorship (McBrien 2020).

For further information please refer to: Defending The Vote: Estonia Creates A Network To Combat Disinformation, 2016–2020 (2020).

Shaping a new generation of anti-corruption activists

In a bid to help change corruption norms and behaviour in Lithuania, the country’s anti-corruption agency, Special Investigation Service (SIS), launched an anti-corruption process between 2002 to 2006, with support from an educational NGO, the Modern Didactics Center, and a group of educators. The aim was to apply experimental approaches, inside and outside the classroom. Anti-corruption elements were introduced to the standard course curriculum wherein corruption came up “naturally” as a part of the lesson, and a values framework helped students identify “why” corruption was wrong. Even projects outside the classroom involving corruption (for example, surveys of their communities) encouraged students to become local activists (Gainer 2015: 6). However, in this case, as in several other cases targeting change in corrupt behaviour, it is “extremely difficult” to assess results. Nevertheless, the anti-corruption initiative, with the support of donors such as the Open Society Institute, the UN Development Programme and the US State Department was used as a pilot guide for similar programmes in eight other central and eastern European countries (Gainer 2015: 11).

For further information please refer to: Shaping Values for A New Generation: Anti-Corruption Education In Lithuania, 2002–2006 (2015).

Grassroot initiatives involving vulnerable groups

Women and other vulnerable groups5693bbc45df7 are known to experience deeper repercussions of corruption (for example, sextortion, a gendered form of corruption where sex rather than money is the currency of the bribe). In several local contexts, however, anti-corruption efforts have gained success when they include (and/or are championed by) the voices of vulnerable groups. However, success once again would depend on contextual customisation and the use of intersectional approaches in designing interventions.

For example, in 2016, in Kulbia, Ghana, 10 widows1019c7167566 got together and learned to create videos, producing a short documentary about their “experiences of discrimination and landlessness as a result of widespread corruption by traditional land custodians”. They raised awareness and demanded accountability from local chiefs and customary land administrators. Such an exercise sparked an advocacy movement that has come to be led by local “queen mothers” (traditional women leaders) (Chibamba, Bankoloh Koroma and Mutondori 2019: 11-12).

For further information please refer to: Anti-Corruption and Gender: The Role of Women’s Political Participation (2022) and Seeing Beyond the State: Grassroots Women’s Perspectives on Corruption and Anti-Corruption (2012).

- The author adds that, on one hand, the goal of “No corruption” may not be possible or credible for sustaining long term citizen engagement, while on the other hand, the aim of “less corruption” inspires few.

- The persistence of corruption understood from the principal-agent model indicates that “the persistence of corruption is rooted in insufficient monitoring and sanctioning of public agents by their principals, whether these are politicians or society at large”. Thus, anti-corruption, from such a view can be ushered by "shaping institutions and building capacity to alter the personal calculations made by potentially corrupt actors" (Jackson 2020: 3).

- The disproportionate effect of corruption on vulnerable groups can be amplified by intersectional factors such as: age; sex; sexual orientation, gender identity and expression; ethnic or racial identity; and religion or belief.

- People surviving on less than US$1 a day in India are allocated ration cards that allow them to purchase essential items such as grains, sugar, cooking oil and kerosene fuel from specified “fair price shops” at subsidised prices (Burgman et al. 2007: 19).

- Corruption and discrimination are known to intersect on the basis of age; sex; sexual orientation, gender identity and expression; ethnic or racial identity; and religion or belief (McDonald et al. 2021: 13).

- While face women face significant risks of land corruption, widows in the Upper East Region of Ghana are particularly negatively affected by traditional land practices. Widowhood typically means the loss of most (if not all) of a woman’s land, which is either sold or given to her husband’s family by the traditional land administrator.