Introduction

Elections are now the most widely used means to select political leaders and legitimise executive authority. In the past three decades, the number of countries holding multiparty elections on a regular basis has more than doubled, from just over 40 in the 1980s to over 90 in the 2010s (World Bank 2017, 24). Despite the global spread of electoral institutions, however, many low- and middle-income countries are still struggling to live up to the standards of electoral democracy. Indeed, while about 90% of all elections around the world were free and fair in the 1980s, this share had declined to about 60% by the 2010s. In newly democratising countries, electoral contests are often (though not always) plagued by procedural flaws, intimidation, violence, and all sorts of irregularities. Even when the incumbent refrains from the crudest forms of manipulation, such as ballot stuffing and deliberate vote miscounts, elections often fall short of democratic ideals. Political parties rarely run on programmatic agendas; more often than not, vote buying, job patronage, and clientelism are the most effective strategies to mobilise votes and secure an electoral majority (Wantchekon 2003; Keefer and Vlaicu 2008; Mares, Muntean, and Petrova 2016).

Democratisation is widely thought to be a necessary precondition for sustainable development and poverty reduction (World Bank 1997; UNDP 2002). Yet reaping the economic and social benefits of democracy depends critically on the quality of electoral contests (Chauvet and Collier 2009). Therefore, the persistence of electoral malpractice in low- to middle-income democracies should ring an alarm bell for the aid community, which has poured an increasing amount of resources into democracy promotion. Since the early 2000s, aid spending on electoral assistance programmes around the world has increased dramatically, going from US$75 million in 2002 to $728 million in 2010 (before declining again to $353 million in 2016).0debe9ec233d During 2002–16, electoral assistance absorbed between 1.1% and 4.5% of total aid spending on “good governance.”d4e0fedc531d

Have all these investments had an impact on the quality of elections? How could aid effectiveness be improved? In this U4 Issue, we undertake a systematic evaluation of the best available evidence to identify lessons learned and suggest how practitioners may develop strategies to improve electoral integrity. In particular, we review elections over time and across countries using panel data on electoral integrity and aid disbursements allocated specifically to improve electoral integrity. Our sample includes 502 national elections in 126 countries during 2002–15, covering (virtually) allnational elections that took place in allaid recipients over this time period.7bf2df6b2a91 To measure electoral integrity for the period 2002–15, we find that the best balance between detail and coverage is achieved by the indicators of electoral conduct published by the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) project (Coppedge et al. 2016).6e02d8b904c4

An analysis of such a comprehensive collection of data seems particularly pertinent since few studies on aid and electoral integrity provide a systematic evaluation of this particular area of development assistance. In this respect, our study makes a contribution to the stock of evidence around aid and electoral integrity. It supplements individual evaluations of specific donor programmes, such as that of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), by providing a data-driven perspective on the issue.cde45c0fc717 It also complements recent field experiments that investigate the impact of specific donor-agency interventions on various dimensions of electoral integrity.f3eca9592d22 Although experimental methods are useful for examining the impact of specific intervention strategies in specific contexts, they are of more limited use in drawing out general lessons for the field (Norris 2015, 36).

Other studies have tried to analyse the bigger picture, employing cross-country statistical analysis to examine the overall effectiveness of donor interventions in the area of democracy and elections. In their work with cross-country data covering all official donor agencies, however, neither Birch (2011, 64–67) nor Norris (2015, 104–8) finds a significant effect of donor-led election support on the quality of electoral contests. The problem with cross-sectional analyses, of course, is that they do not assess changes over time, meaning that we cannot be sure that changes in electoral integrity are due to fluctuations in aid spending. Our analysis seeks to complement these studies by adding a time dimension to cross-sectional data to identify the effect of aid spending on the quality of elections.

The only other paper that employs a panel data specification to study a similar question is by Finkel, Pérez-Liñán, and Seligson (2007). Focusing on aid spending by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the authors find a positive (albeit modest) impact of democracy promotion on democratic development for the period 1990–2003. Their paper, however, focuses on one particular donor agency and investigates electoral integrity only in passing, as a component of the broader notion of democratic development. A focus on the 1990s, moreover, makes the study somewhat outdated.

Our analysis of the period 2002–15 provides an original contribution to the evidence base around election aid and integrity. Within our setup, we explore three policy-relevant questions: (1) Have electoral assistance programmes improved electoral integrity? If so, in which contexts has democracy promotion proved most effective? (2) How sustainable are the effects of election-support aid? (3) Are certain forms of electoral misconduct more responsive than others to donor-funded interventions?In providing systematic, evidence-based answers to these questions, we seek to stimulate new thinking around general approaches to building integrity in elections.

Of course, the drawback of a big-picture analysis is that it doesn’t tell us much about the effectiveness of specific interventions, but macro and micro evaluations would seem to be complementary, each illuminating different parts of the complex challenge of building integrity. Our answers to these three questions are followed by a policy discussion in which, rather than making recommendations on a specific course of action, we offer some advice that can feed into debates around strategies.

Election-support aid and electoral integrity

Types of violations that undermine the integrity of elections

To describe the extent to which elections conform to democratic principles, political scientists and policy analysts have used terms such as “free and fair elections,” “electoral quality,” and “electoral integrity.” In this paper, we understand all these terms as equivalent, although for convenience we focus on the notion of integrity. Electoral integrity refers to “contests respecting international standards and global norms governing the appropriate conduct of elections” (Norris 2015, 4). Standards and norms are based on international legal instruments (Tuccinardi 2014). For instance, Article 21(3) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights stipulates that “the will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government; this will shall be expressed in periodic and genuine elections which shall be by universal and equal suffrage and shall be held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.”

In low- to middle-income societies, however, electoral contests are often riddled by a series of violations and irregularities. Pippa Norris, in Strengthening Electoral Integrity,describes typical shortcomings of electoral contests in developing countries:

Opponents are disqualified. District boundaries are gerrymandered. Campaigns provide a skewed playing field for parties. Independent media are muzzled. Citizens are ill-informed about choices. Balloting is disrupted by bloodshed. Ballot boxes are stuffed. Vote counts are fiddled. Opposition parties withdraw. Contenders refuse to accept the people’s choice. Protests disrupt polling. Officials abuse state resources. Electoral registers are out of date. Candidates distribute largesse. Votes are bought. Airwaves favor incumbents. Campaigns are awash with hidden cash. Political finance rules are lax. Incompetent local officials run out of ballot papers. Incumbents are immune from effective challengers. Rallies trigger riots. Women candidates face discrimination. Ethnic minorities are persecuted. Voting machines jam. Lines lengthen. Ballot box seals break. Citizens cast more than one ballot. Legal requirements serve to suppress voting rights. Polling stations are inaccessible. Software crashes. “Secure” ink washes off fingers. Courts fail to resolve complaints impartially. (Norris 2017, chap. 1)

The integrity of an electoral contest may be undermined at different levels, reflecting the multi-dimensional and composite character of the notion of electoral quality (Schedler 2002). Corrupt practices – bribery, extortion, fraud, and nepotism – are behind many of these violations of integrity, but so are other illicit methods, such as intimidation, violence, and theft. At the level of electoral contestants, the incumbent power holder – the ruling coalition, or the party or individual in power – may restrict the entry of political organisations into the electoral arena. It may spuriously bar opposition candidates from running, starve them of resources, and sever the communication links between contestants and voters. Additionally, the incumbent may skew the playing field in its favour by preventing opposition rallies or by siphoning off government resources to finance its own campaign. In the most extreme cases, it may also insulate key elective offices from genuine electoral competition, allowing only limited contestation under the aegis of an authoritarian coalition (see, for example, Khan 2013).

At the level of voterpreferences, both incumbent and contestants may engage in vote buying, effectively denying citizens their right to freely formulate and express their individual political preferences. The incumbent (or, less frequently, the contestants) may also exploit control of the state’s bureaucracy and security apparatus to mobilise votes among civil servants or intimidate opposition voters. Acting on behalf of their political sponsors, the owners or managers of politicised firms may also pressure or intimidate their workers to vote for a particular candidate (Mares, Muntean, and Petrova 2016).

At the level of outcomes of electoral contests, the incumbent may manipulate the process of casting, counting, and aggregating ballots in a variety of ways – by ballot stuffing, destroying or manipulating votes cast, deliberately miscounting the votes, tampering with the vote aggregations, and so on. In the most extreme cases, the incumbent may refuse to step down if the outcome of the election is not in its favour.

Aid agency interventions to support electoral integrity

A review of programming documents suggests that electoral assistance strategies are premised on a three-pronged diagnosis of structural deficiencies that give rise to electoral misconduct. First, rules and procedures such as voter registration systems or the laws governing the electoral management body (EMB) may be missing, vague, or faulty. Second, when rules and procedures are notionally in place, their enforcement may be deliberately weak or absent altogether. Third, even when the political will exists to respect the rules of the game, the technical and organisational capacity of the relevant actors may be insufficient to accomplish this task. Indeed, electoral malpractice may result not only from intentional manipulation but also from knowledge or capacity deficits.7b328e2c9603

Corresponding to these three potential sources of misconduct (rules, enforcement, capacity) are three broad types of intervention: (1) establishing or improving electoral rules and regulations; (2) strengthening the capacity and independence of enforcement organisations (e.g., electoral management bodies, courts, etc.); and (3) building the capacity of civil society to monitor and report on elections. An additional but closely related set of interventions aims to empower citizens to exercise their (passive and active) electoral rights. Such interventions might include, for example, training political or community leaders or taking steps to increase voters’ electoral participation, especially among marginalised groups such as women and youth.

Real-world examples of electoral assistance provide some illustration. Focusing on electoral contestants, for instance, a UK Department for International Development (DFID) project in Somaliland helped establish an agreed set of rules for adjudication of election disputes (DFID 2013, 2). The USAID-funded Bangladesh Election Support Activities (BESA) programme sought to increase compliance with campaign finance laws in Bangladesh by strengthening the analytical capacity of government bodies to audit candidate filings (USAID 2015, 4). A European Union (EU) funded project sought to improve the functioning of the Nigerian EMB by offering advice on the establishment of effective internal rules. This included efforts to “support skills and capacity development for women as candidates and party leaders” (EU Commission 2014, 8). Focusing on voterpreferences, the same project in Nigeria sought to boost women’s political empowerment by supporting targeted legal reforms to promote gender-based affirmative action and combat family voting, or undue patriarchal influence over voting choices (EU Commission 2014). Regarding the outcome of electoral contests, all three of these programmes included activities to improve the capacity of civil society and media groups to monitor and report on electoral contests (e.g., by funding domestic election monitors or training media practitioners on issue-based coverage of elections).

Of course, many of these activities cut across the strategies and categories identified above. Some of them also target different aspects of electoral integrity simultaneously. For this reason, there is no unified theory of change underpinning electoral assistance programmes. Rather, each type of intervention is expected to improve one or more specific aspects of integrity through a different causal mechanism. For instance, a voter education campaign may empower vulnerable groups to exercise their franchise, while international monitors may help deter vote-counting irregularities on polling day. When they allocate resources to electoral assistance, however, donor agencies would like each dollar invested to have a material impact on the overall quality of elections.

Method of analysis

Data and variables

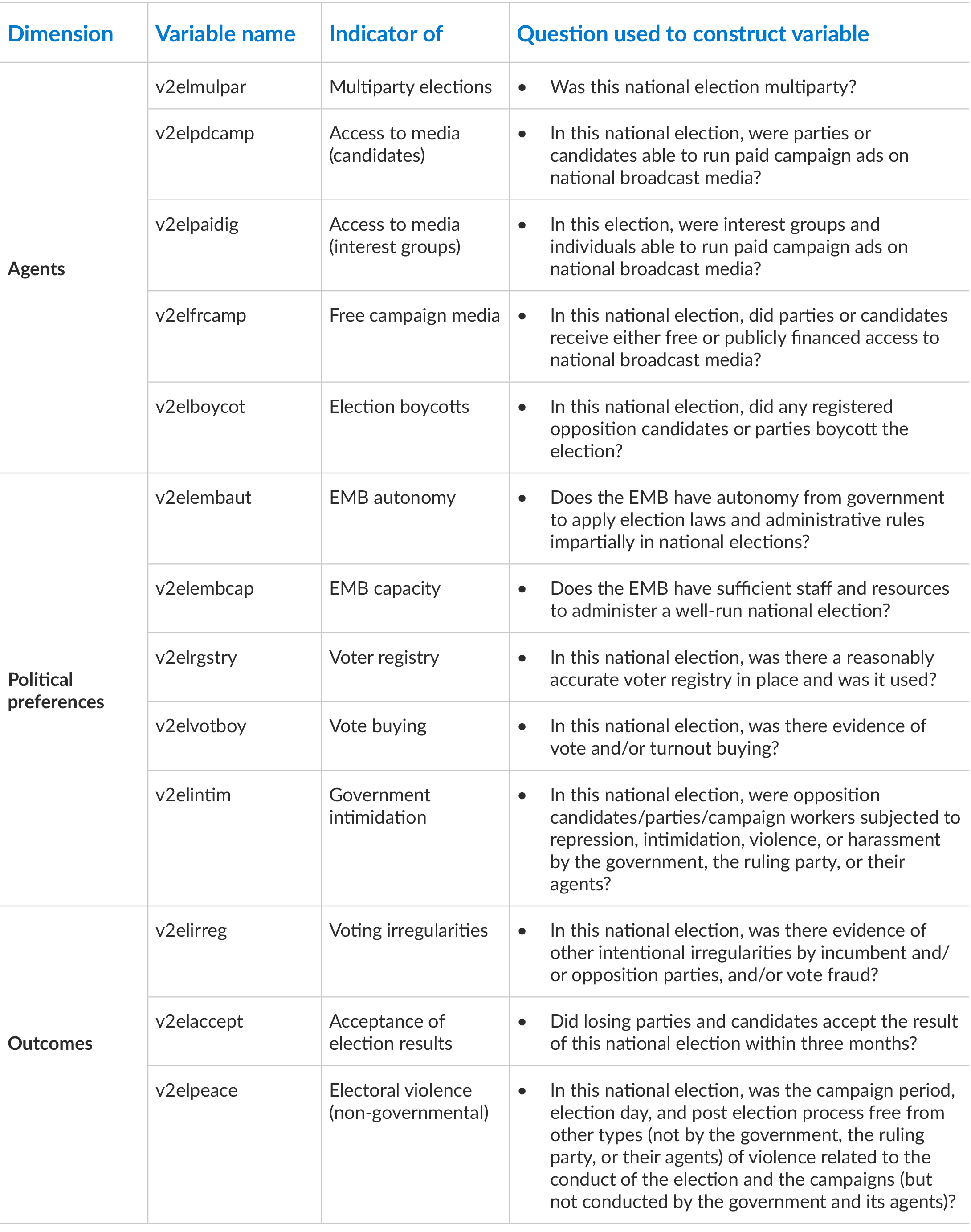

Our two main variables are (1) official development assistance (ODA) spending on election support, and (2) electoral integrity. To measure integrity, we use the Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) dataset compiled by the University of Gothenburg in Sweden (Coppedge et al. 2016). This dataset offers a number of comparative advantages that influenced our choice. First, V-Dem provides better coverage over time than other datasets; second, it provides richer information on a continuous scale; third, each V-Dem data point is based on five independent assessments, meaning measurement error is likely to be lower in the V-Dem data than in other datasets. To measure the concept of electoral integrity, we singled out 13 indicators (Table 1). The variables are coded for election years only, leading to 502 election years during 2002–15, and each data point refers to the conduct of specific electoral contests.a8f32c08a94f

Table 1: Components of electoral integrity index (integrity)

To measure our main independent variable of interest, namely aid for election support, we use data reported by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The OECD data allow us to disaggregate aid volumes by project purpose and isolate the aid flows specifically directed to electoral assistance, rather than to democracy promotion, good governance, or development assistance more generally.44a46c168012 The volumes of aid expenditures on election-support programmes are a proxy for the extent and intensity of donor-led efforts to ameliorate electoral integrity. More spending indicates more and/or more extensive programmes and is expected to lead to improvements in integrity levels. More specifically, the budget category for “elections” includes aid flows designed to support “electoral management bodies and processes, election observation and voters’ education” (OECD 2018). Therefore, the measure offers an adequate operationalisation of electoral assistance interventions as defined in the preceding section.

The dataset pools aid spending by all official donors (bilateral and multilateral, DAC and non-DAC88647ea572b7). In 2015, 29.7% of aid spending for elections came from multilateral donors – chiefly the EU and, within the United Nations system, the UNDP. The remaining 70% originated from bilateral donors, typically G7 countries such as the United States (which provided some 50% of all bilateral aid for elections) and the United Kingdom (which contributed 17.7%).b346e5c72356 All these agencies espouse similar conceptions of electoral integrity and draw from the same toolkit of interventions in their efforts to promote it. Although we acknowledge that each donor may employ a slightly different mix of interventions on the ground, we conduct our analysis from the point of view of the “average donor,” a common approach in the aid literature.

Isolating the effect of donor interventions

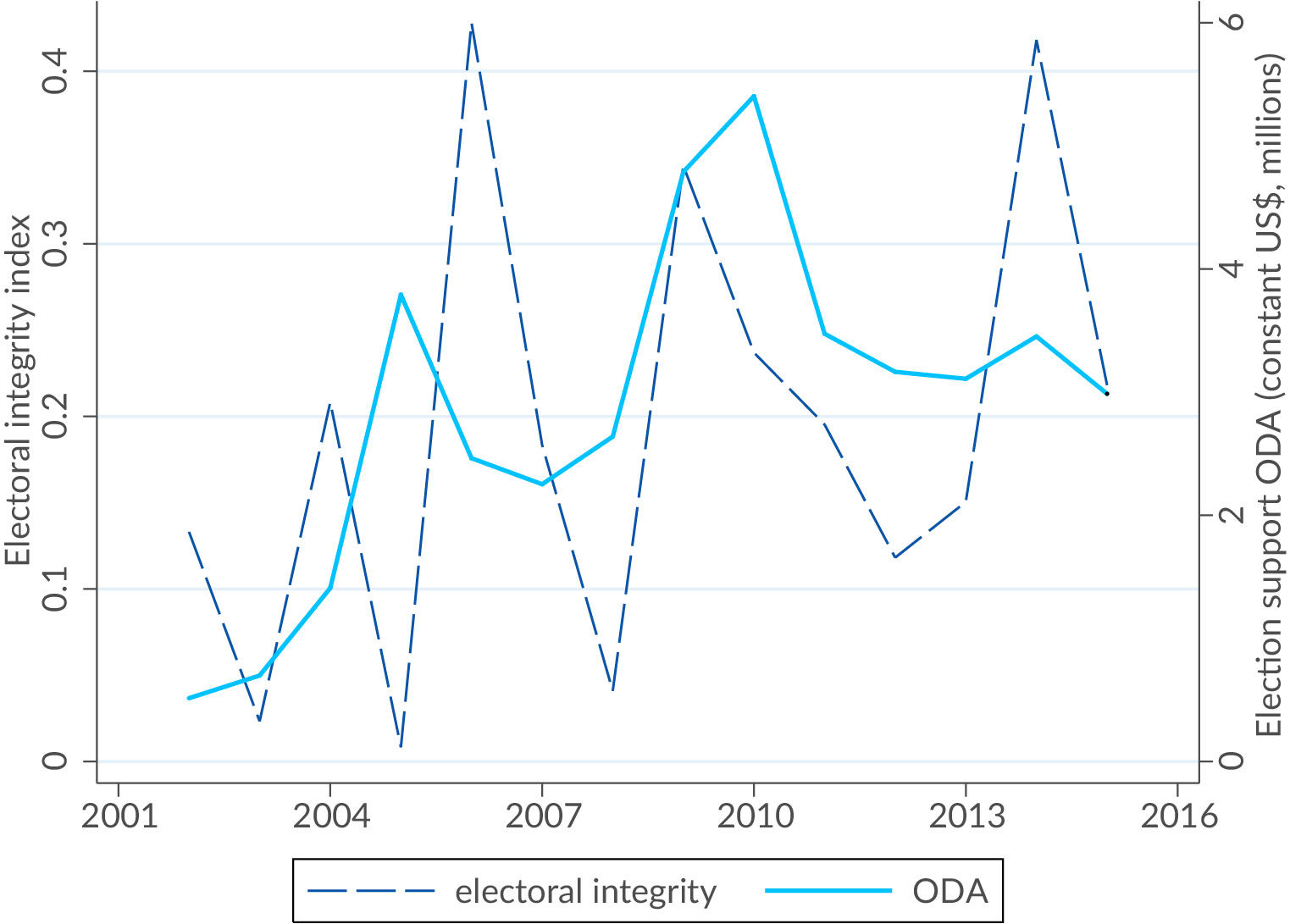

Figure 1: Election support ODA (solid line) and electoral integrity (dashed line), 2002–2015

Note: The data are averaged over 129 aid recipients. Sources: OECD, International Development Statistics, 2017; V-DEM Project.

Trends in aid spending for election support during 2002–15 are summarised in Figure 1. Election-support ODA increased dramatically during 2002–10, then declined slightly in the wake of the global financial crisis. During 2002–15, donors spent an aggregate total of $5.1 billion on election-support activities in developing countries. On the recipient side, election-related ODA amounts to an average influx of about $2.8 million per country per year. Such spending rises to about $5.6 million during a country’s election year, indicating that most (51.4%) aid for electoral assistance is disbursed in the run-up to elections, rather than between successive contests. Some of the top aid recipients in this programme area are also aid-dependent countries more generally, such as Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Haiti, and Sudan.

In addition, Figure 1 shows the average level of electoral integrity across aid recipients during 2002–15. Aid spending for elections by all donors correlates positively (0.32) with average electoral integrity in aid recipients. The correlation coefficient increases to 0.43 if we consider the relationship between average electoral integrity and total aid disbursed in the preceding year. During 2002–15, an unprecedented increase in donor support for electoral integrity was accompanied by an overall increase in the average quality of elections in the developing world.

Of course, we cannot tell from this correlation whether election-support aid actually had a causal impact on the increase in electoral integrity. That outcome could have been influenced by other confounding factors. To control for alternative explanations, we undertake a regression analysis in order to isolate as far as possible the causal significance of electoral-support aid (we discuss our econometric strategy in greater detail in the Appendix). In our view, our analysis, although it does not meet the strict definition of causation that would arise from a randomised experiment, provides a good first-order approximation of the causal impact of election-support programmes on electoral integrity.

Empirical results and policy discussion

Effectiveness of election-support aid

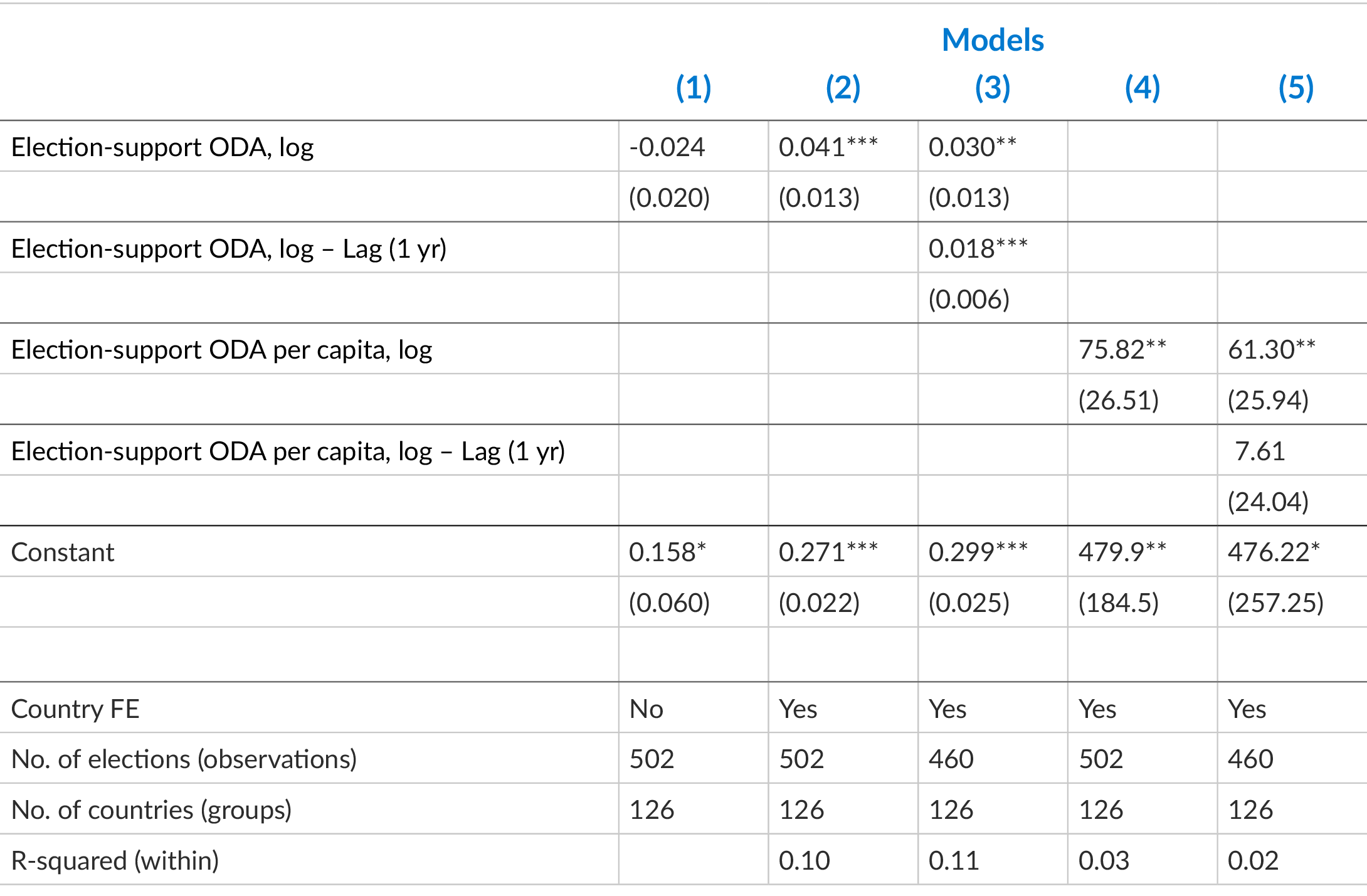

The analysis examines whether aid disbursements for electoral assistance have an effect on electoral integrity. These results are presented in Table 2. Each column displays a different model, corresponding to the different ways we set up the analysis. Model 1, shown in column 1, is a simple regression of the electoral integrity index on (the log of) election-support ODA. The estimated coefficient is negative and statistically insignificant, indicating no relationship between aid and integrity. This negative relationship, however, is biased if some other determinant of integrity omitted from the regression has a beneficial effect on integrity while inducing donors to allocate less aid. When making funding decisions, donors may take into account some (fixed or slow-moving) country characteristics (e.g., level of development, level of political contestation) that affect electoral integrity. Specifically, donors may decide to provide more extensive electoral assistance to the countries that are most in need (see Appendix).

To address this concern, Model 2 includes country fixed effects (FE) – essentially, dummy variables for each country that capture all country-specific characteristics that may jointly influence aid allocations and integrity outcomes, thus correcting the bias of Model 1. In Model 2, any remaining effect of aid disbursements is identified only by using time variation. Thus, the analysis answers the question: within each country, is it the case that (random) increases/decreases in aid spending for electoral assistance are associated with improved integrity standards? The answer, according to the data, is yes. ODA for election support is estimated to have a positive and statistically significant effect on integrity. This is suggestive evidence that election-support ODA and related programmes do have a beneficial effect on the quality of elections in aid recipients. Model 2 studies the effect of aid disbursements during election years. Model 3, by contrast, allows for electoral assistance programmes implemented up to one year before an election to have an effect on that contest. The results suggest that programmes implemented in pre-election years, too, have a statistically significant, albeit smaller, impact on the quality of the upcoming contest. Further results, not reported, suggest that aid disbursed two years prior to an election has no appreciable effect on the integrity levels of the ensuing election.

Models 4 and 5, finally, experiment with an alternative conceptualisation of the effect of aid on integrity. So far, we have assumed that what matters is the total volume of aid (for elections) assigned to a given country for a given election, regardless of country size. Models 4 and 5 assume that what matters is the volume of aid disbursed per capita. It is difficult to establish a priori which of these two assumptions is the correct one, so we try both. The results (for election-year spending) are robust to making this alternative assumption, although statistically the model exhibits a worse fit with the data.

Table 2: Effects of ODA spending for election support on electoral integrity (OLS), 2002–2015

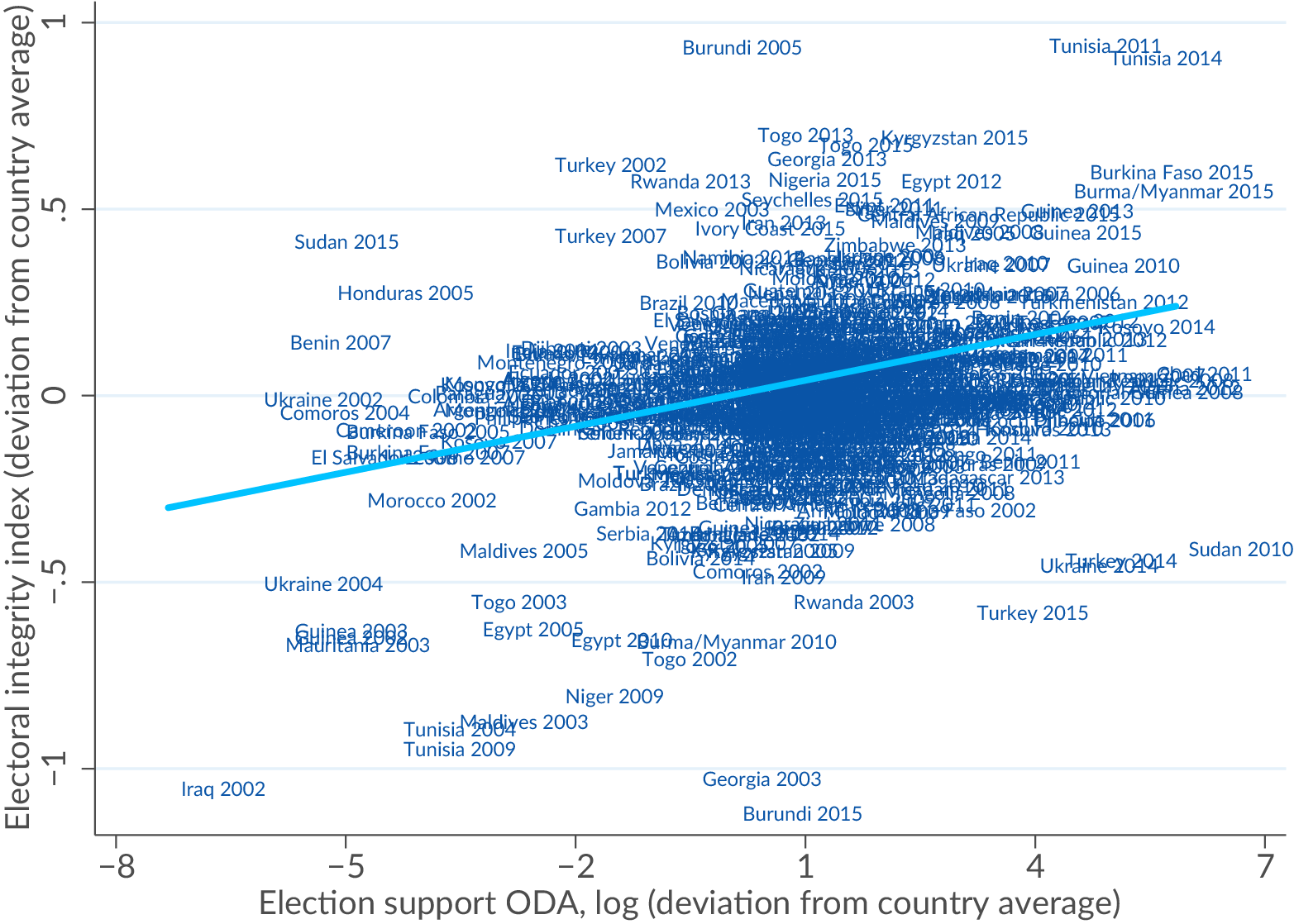

Another way to present the relationship is through a scatterplot that summarises the patterns within the data. Figure 2 plots the estimated relationship between aid and integrity (based on Table 2, Model 2) after purging the influence of fixed country characteristics (as proxied by the country FE) that may influence both aid and integrity simultaneously, thus potentially biasing the relationship. Since identification of the relationship is only based on changes in aid and integrity levels taking place within each country, a movement on the horizontal axis should be interpreted as a deviation from a country’s average level of aid, and movement on the vertical axis signals deviation from the country’s average level of integrity. The line in the plot rises from left to right, demonstrating that donor-funded electoral assistance does seem to have a positive effect on the quality of elections in developing countries.

Figure 2: Partial correlation plot: election-support ODA and electoral integrity

Notes: Based on Table 2, Model 2.

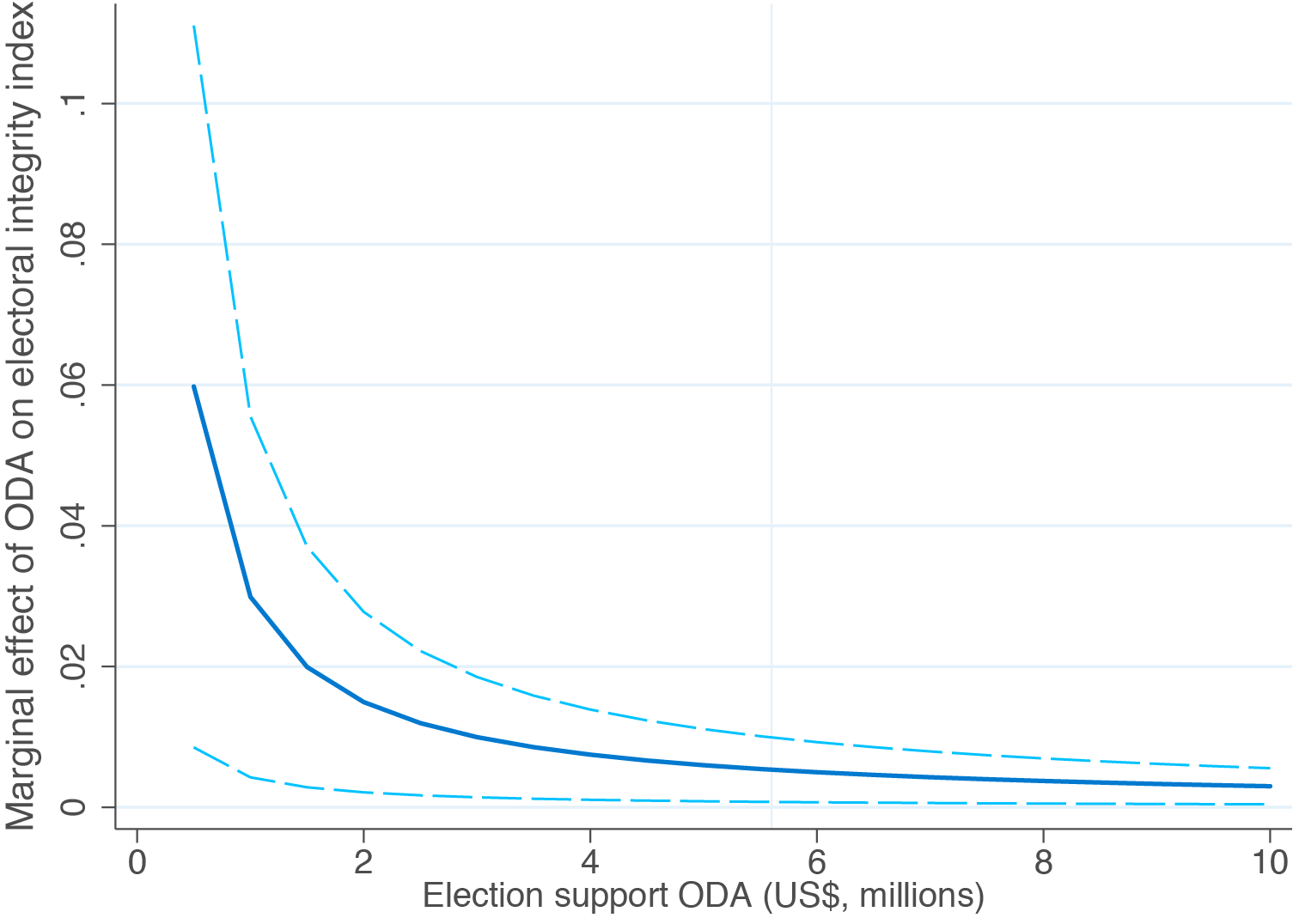

Magnitude of the effect of aid on integrity

We have provided suggestive evidence indicating that aid does help improve electoral integrity. However, for policymakers it is important to understand the size of the marginal gains that can be expected from increasing election-support ODA. An intuitive way to interpret the results is to consider the impact of each additional dollar spent.603468811982 The analysis presented in Figure 3 suggests that the aid-integrity relationship is non-linear: the effect of the marginal dollar spent decreases as the volume of aid increases. For countries that receive little election aid to start with, the effect of each new dollar spent is quite high. This effect, however, declines as the country receives more aid (i.e., more election support) and tends to flatten out thereafter. For an aid recipient receiving the average volume of election-support ODA (marked in Figure 3 by the vertical line),1e7b458c873f an additional $1 million spent in an election year (moving from $5.6 million to $6.6 million in annual receipts for election support) is followed by an improvement in electoral quality equal to just 0.66% of the average variation (i.e., standard deviation) in integrity levels across all aid recipients. In other words, the average investment in electoral assistance does make an appreciable impact, but the magnitude of this improvement is small if measured relative to the total observed variation in the quality of elections across developing countries. Similarly, an additional $1 million spent in the year preceding an election leads to an increase in integrity equal to 0.63% of this average deviation. Consistent with this finding, donor-funded electoral assistance explains only 11% of the total variation in electoral integrity over time (Model 3), which means that the reason why some developing countries have better elections than others is not (primarily) the fact that they receive more aid for this purpose.

Figure 3: Estimated effect of election-support ODA on electoral integrity (95% confidence interval)

Notes: Based on Table 2, Model 4. The diagram plots the marginal effect of election-year ODA spending on the electoral integrity index, at different levels of aid spending. The dashed lines mark the 95% confidence interval. The vertical line denotes the average value of ODA spending ($5.6 million). The standard deviation of the integrity index is 0.78.

Policy discussion: How to make electoral support more effective

Our results suggest that election-support ODA is a factor in improving electoral integrity – but the gains on average are rather small. The question for policymakers is: can aid be targeted in a way that provides more “bang for the buck”? One way to increase aid effectiveness, as suggested in the preceding section, is to target countries that do not currently receive large volumes of aid for election support. In these countries, the effect of allocating the marginal dollar is greater.

The marginal effect of aid spending, however, may also differ systematically across different country contexts, even holding current aid spending constant. The large group of aid-receiving countries is a rather heterogeneous group that includes least-developed countries such as Haiti as well as more advanced middle-income economies such as Argentina and Malaysia. It is plausible that structural conditions, as proxied by income levels, may create different opportunities and constraints for donor agencies implementing electoral assistance programmes.6565ba013f6f

Thus, we examine whether there are systematically different pay-offs from allocating aid to countries at varying levels of development. To investigate this policy question, we allow the per capita gross domestic product (GDP) of countries to interact with aid to examine whether the level of development exerts a moderating influence on the magnitude of the aid effect. Figure 4 reports the estimated effect of election-support ODA on integrity at different levels of development. Although electoral assistance is never estimated to be detrimental to electoral democracy, the results suggest that (election-year) support programmes (left panel) may be subject to decreasing marginal returns as an aid recipient develops economically. The same is true, albeit less starkly, for pre–election year spending (right panel). For instance, the integrity gain from doubling aid spending in a country with a GDP per capita of $403 is more than twice as large as the gain from doubling aid spending in a country with a GDP per capita of $2,980. For income levels higher than $4,000 per capita (that is, in upper-middle-income economies, using the World Bank classification), the effect of doubling aid spending becomes statistically indistinguishable from zero.

Figure 4: Effects of ODA spending for election support at different levels of development

Considerations for practitioners: Our results suggest that to improve the effectiveness of aid, donors should consider targeting electoral assistance programmes to low-income societies. This does not mean that the increase in overall aid effectiveness in this area from reallocating aid to lower-income countries will be automatic. We present here the average gain. Yet, the results indicate that the lower a country’s income levels, the more likely it is to benefit from election support programmes. At higher levels of income, broader societal transformations are likely to be a more consequential driver of overall electoral quality, so that the gain from receiving donor-funded election support is much smaller. It goes without saying that considerations of reallocation to low-income societies should also be based on a thorough review of country-specific political and social factors that may potentially hinder the effectiveness of election-aid support.

Sustainability of election-support aid

Another important test we undertake is to try to understand the sustainability of support to electoral integrity. In our analysis, therefore, we test the extent to which gains in integrity in one election carry over to the next one. Table 3 reports models that account for the potential “dynamic persistence” of integrity levels over successive contests. Column 1 reports a simple static model along the lines of Table 2, Model 3. Column 2 conditions the outcome on the integrity level achieved in the previous contest, which might have taken place a year or even several years prior. Although integrity norms do seem to be subject to persistence, the magnitude of the autoregressive coefficient (0.322) is fairly small. This means that only about 32% of the integrity level achieved in a given contest is “automatically” carried over to the next contest.77badb8f5fe4 Of course, elections may be spaced several years apart and a number of intervening events might have an impact on the quality of the subsequent election. Still, the fact that integrity norms in developing countries are not very “sticky” raises important questions about the sustainability of donor-funded reforms. It appears difficult for aid recipients to entrench and institutionalise the norms and processes established by donor agencies. In other words, the positive outcomes of donor-funded election support are rather ephemeral. The estimated impact of election-support ODA is slightly smaller in this dynamic model, but still close to our previous findings.

Table 3: Robustness analysis: Controlling for dynamic persistence

Notes: The table reports ordinary least squares (OLS) regression with country fixed effects (FE). The dependent variable is electoral integrity. Robust standard errors clustered at the country level are reported in parentheses. *** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1; constant not reported to save space.

Policy discussion: How to make electoral support more sustainable

Donor-funded electoral assistance does work. However, its impact on the integrity standards of aid recipients is quite small and short-lived. In other words, the small positive gains do not sustain very well across electoral cycles. In part, donors may need to accept that a short-term impact merits the investments in integrity. At the same time, it would seem wise to explore the question of whether there are steps that donors can take to ensure greater sustainability of integrity gains. We suggest making more selective choices about the kinds of interventions to pursue based on a close understanding of the conditions of the country in which these interventions will take place.

This is not an easy process. It requires an understanding of how the informal nature of (electoral) politics presents certain implementation constraints that affect sustainability in development settings.e26848293665 A way to understand these informal, uncodified processes and relations is to view the nexus between politicians and voters as essentially a patron-client relationship. “Patron-client relations” is a term that development theorists use to describe a broad range of informal and personalised relations of power and exchange. This type of clientelistic mobilisation is present to some degree in most countries but is often ubiquitous in low- to middle-income societies (Khan 2005; Uberti 2016). There are several reasons why this is the case (see Box 1).

Box 1: The importance of patron-client relationships in developing-country politics

In their simplest form, patron-client relations involve an exchange of resources for loyalty between two individuals of unequal status (Kitschelt and Wilkinson 2007; Khan 2010, 60–64). In the context of electoral politics, patrons are current or prospective office holders who capture material resources from the state (licenses, public funds, etc.) and distribute or promise to distribute these goods to their clients, who are typically voters. These rewards are intended to secure the clients’ continuing loyalty to the patron and to endow them with resources to distribute further down the hierarchy. In turn, clients offer their loyalty and organisational support by providing or mobilising votes or bringing more political entrepreneurs into the network. Traditional scholarship tends to emphasise culture – especially patrimonial norms of authority, with deference to strong leaders and charismatic “big men” – as the fundamental determinant of such patterns (see Gray and Whitfield 2014, 4–6 for a review). Recent contributions, however, maintain that a cultural explanation for the dominance of clientelistic politics is hard to reconcile with the immense diversity of traditional cultures observed in the developing world and with the great variety of economic performance outcomes associated with clientelistic political systems (Mkandawire 2013). Moving beyond a cultural perspective, North, Wallis, and Weingast (2012) link the prevalence of clientelistic political conflicts to the lack of centralised control over violence by most developing-country states. The dispersion of violence potential creates myriad opportunities for political entrepreneurs to mobilise their clienteles, flex their muscles, issue credible threats, and capture a share of state-created resources.

A more fundamental root cause is suggested by Khan (2005), who links the dominance of clientelistic political strategies to a lowlevel of economic development. In low-income societies, the modern industrial sector is typically small as a share of GDP and of total employment; most people are employed in the public sector or are self-employed. For this reason, low-income societies do not have consolidated classes and class interests defined by their relationship to productive capital, as is the case in advanced industrialised countries (Gray and Whitfield 2014, 22). Consequently, politics tends to be faction-based and clientelistic, rather than class-based and programmatic.

The predominance of patron-client politics creates a broad realm of informal power dynamics and relations that act as structural constraints on the sustainability of the standard repertoire of electoral-integrity interventions. Here we identify three types of constraints that we deem highly relevant to donor programming and project implementation. This discussion, however, is by no means intended to be exhaustive.

First, theautonomy of enforcement institutions may be compromised. Many of the interventions that support electoral integrity focus on reforming the legal framework for elections, by means of, for example, campaign finance laws or regulations around administrative procedures. Ultimately, however, the sustainability of these efforts requires autonomous organisations (judiciary, electoral commission) that are able to sanction violations of these rules. Electoral integrity frameworks are typically subject to manipulation by powerful actors, with the formal electoral institutions and organisations unable to regulate and discipline the intense political rivalry between political factions, each faction organised hierarchically along patron-client lines. Groups with the ability to muster the organisational support to capture the state actually get to “own” the state and its apparatus in a way that can overwhelm the autonomy of those enforcement institutions (Gray and Whitfield 2014, 4). Within clientelistic systems, attempts to enforce formal electoral rules run up against the likelihood that the incumbents will only enforce laws if it is in their political interest to do so. And so the incumbent may use its privileged control over the administrative and military apparatus of the state (the police, polling booths, vote tallying centres, etc.) to manipulate electoral processes with relative impunity.

If an analysis demonstrates that informal power is skewed in favour of the incumbent, the autonomy of the enforcement institutions is likely to be diminished, creating uncertainty over whether rules introduced in one election will be enforced in the next. In such a situation, it may not make much sense to, for example, fund capacity building of enforcement institutions; instead, donors can select alternative approaches that do not rely on formal enforcement mechanisms, such as supporting social accountability efforts.

Second, informal arenas of decision making may decide who gets what, including in the area of political finance. Within clientelistic systems, the pool of budgetary resources is typically so small (due to the state’s typically low ability to generate tax revenue) that redistributive demands from organised patron-client factions cannot easily be satisfied through the formal budgetary process, that is, by means of formal institutions such as fiscal or social policy (Khan 2010). Rather, redistributive demands are typically accommodated through all sorts of informal, off-budget transfers, or through the informal, rule-violating manipulation of formal budgetary or policy tools. These interactions are informal because they are not governed by codified (formal) rules, but typically take place under the radar, leading to the informalisation of policymaking. In general, this creates informal arenas where redistributive politics takes place and where information about who gets what is often not forthcoming.

As this is an important constraint on effectiveness and sustainability, donors would do well to think through how to work around it. Consider the regulation of political finance, whichraises some of the most common problems for electoral integrity in many countries around the world. Typically these problems are addressed through the introduction of laws and standards, such as disclosure requirements or contribution limitations (Norris 2017). In many cases political competitors do abide by these rules. But an analysis of informal structures may identify constraints to the sustainability of such an approach.

For instance, using the case of a small developing economy (Albania), Imami, Lami, and Uberti (2017) show that the incumbent uses its discretion in the allocation of mining licenses to reward political supporters in the run-up to elections. These supporters may include, for instance, politically connected firms with the capacity to provide (legal or illegal) campaign finance or to mobilise votes among their employees or community members. In such a case, political contributions are raised informally, beyond the reach of political finance regulation. A routine regulatory approach may have little “bite” in the longer term as political actors eventually find ways to circumvent the rules. Instead, donors could consider complementary (and more context-specific) interventions to help enforce the regulation of political finance. Examples might include funding NGOs or other social actors to monitor the distribution of contracts and licenses prior to elections (if in a given context political finance is shown to be often given in exchange for licenses), or mobilising powerful social groups (for instance, firms that lose out from this politicised allocation of licenses) to expose and sanction illegal ways of raising political finance (Khan, Andreoni, and Roy 2016).

A third constraint is that formal norms of electoral integrity may be trumped by alternative social norms. Practitioners should closely examine the norms around elections that prevail in specific contexts. As has been noted, candidates involved in electoral contests generally mobilise votes by means of clientelistic promises (e.g., jobs, international travel) or material perks (e.g., subsidies, cash), often with little or no recourse to programmatic forms of campaigning. Consider attempts to prohibit vote buying, a violation of electoral integrity that is proscribed, yet common, in many countries. Efforts are often made to support enforcement institutions to monitor and prevent these practices. Yet an analysis of patron-client relations may demonstrate that such an intervention would be highly constrained because it runs up against one of the central rules of the game of patron-client mobilisation in developing countries. In a context where unemployment is rampant and interests and preferences may not be clearly defined,128ad4b4a404 voters often see their vote as a good that they can trade for material benefits. As noted by Khan (2010, 63), “the ‘contract’ between patrons and clients is often surprisingly modern and rational […] and is readily re-negotiated if clients (or indeed entire factions) are offered better terms by other patrons.” Thus, vote buying can become normalised, becoming an (unpalatable) “norm” dictated by the economic and political strictures of the social order rather than a violation of widely embraced democratic principles (Uberti 2016). Attempts to eliminate it through the enforcement of laws may eventually be overwhelmed by the prevailing logic of clientelism, which may command greater normative support in the local society. In such a situation, it may be more sustainable to think of ways to encourage broader shifts around underlying norms by means of education campaigns, school curricula reforms, or public discussions.

Considerations for practitioners:Donor agencies can examine these constraints by structuring traditional political economy analysis and other risk assessment tools more consistently around the notion of informal norms and institutions, patron-client networks, and the overall distribution of power. In some cases, donors may even treat informal patron-client networks as “an integral part of the solution” by making clientelistic politics part of intervention design (Parks and Cole 2013, 12). For instance, it may be useful to identify particular clientelistic networks that stand to benefit from improvements in electoral integrity under specific circumstances (e.g., oppressed social or political groups in a semi-authoritarian regime). Donors could then work out imaginative ways to mobilise these groups’ support to demand and achieve cleaner elections (see Khan, Andreoni, and Roy 2016, 22).

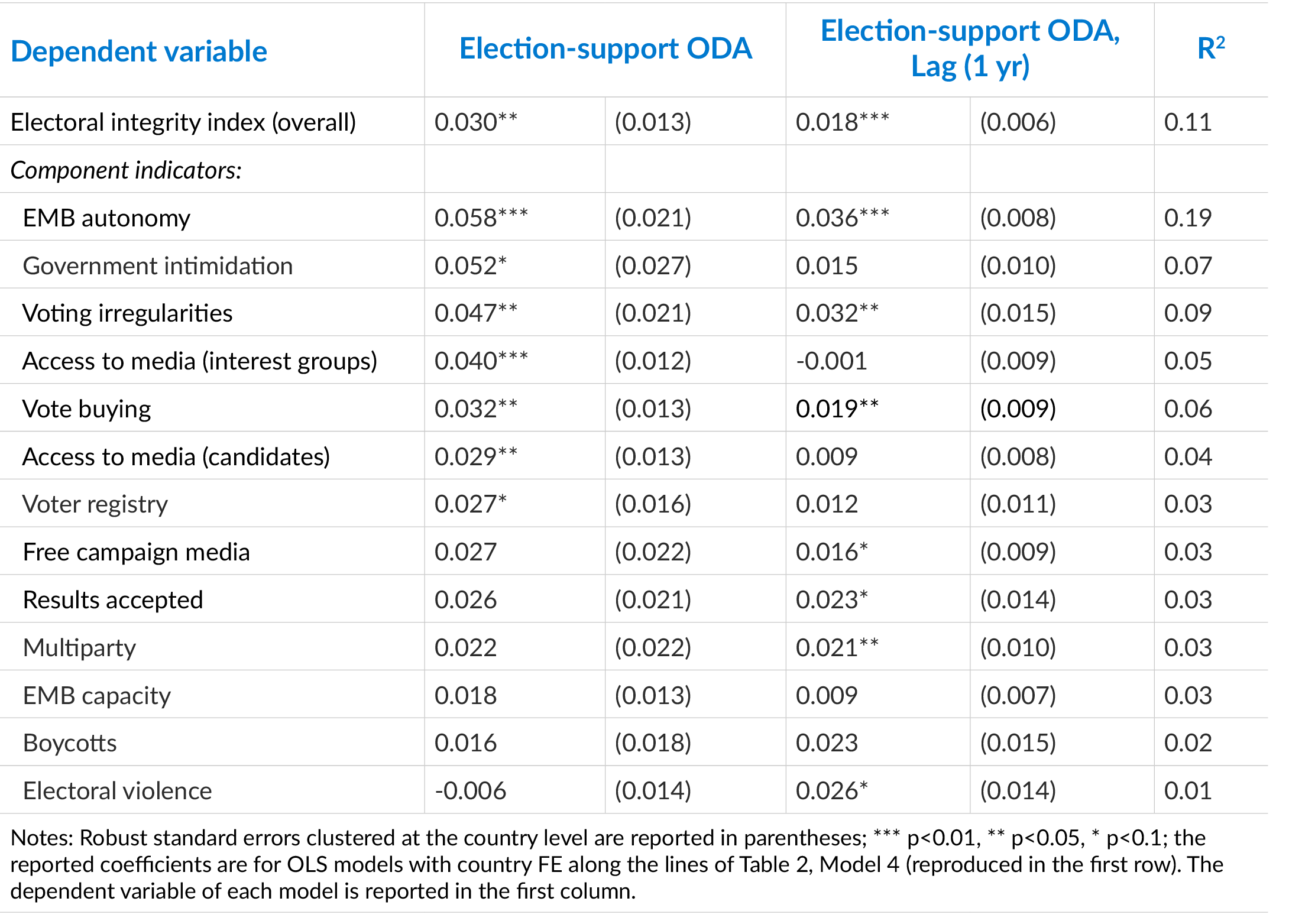

Forms of electoral misconduct that are more responsive to election-support aid

Another question that should be of concern to donor agencies is which particular aspects of electoral integrity are most amenable to donor interventions. An answer to this question is important because targeting the types of misconduct that are likely to be more responsive to donor interventions may improve the overall cost-effectiveness of electoral assistance programmes. To investigate this question, we estimate versions of Model 3 from Table 2 using the 13 sub-components of electoral integrity (which we used to construct our overall integrity index) separately as dependent variables. As in Table 2, Model 3, we allow for electoral assistance programmes implemented during an election year, as well as those taking place up to one year prior, to have an impact on the ensuing contest.1b8e5f695582

The point estimates and standard errors from these 13 regressions are reported in Table 4. For comparison, the first row reports the results of the regression model with the overall integrityindex on the left-hand side. In line with our previous findings, the parameter estimates are generally larger for election-year ODA spending than for its first lag. Election-year interventions are particularly effective at promoting the political independence of the EMB, containing government intimidation, pre-empting voting irregularities that take place on election day, and ensuring access to broadcast media for interest groups and, to a lesser extent, election candidates. ODA spending in the year preceding the election, in contrast to election-year spending, is also estimated to have a beneficial effect on electoral violence, party bans, and the likelihood of election results being accepted by the incumbent, although by far the strongest impact of once-lagged ODA is, again, on voting and counting irregularities taking place on election day.

Table 4: Effects of ODA spending for election support on components of electoral integrity

Policy discussion: How to tackle the most difficult aspects of electoral misconduct

Although they are not conclusive, these results suggest that different types of electoral malpractice are variably responsive or resistant to aid-funded electoral assistance programmes. This means, on the one hand, that targeting the more amenable forms of misconduct, such as vote-counting irregularities and ballot stuffing, may be more cost-effective on average than other interventions. On the other hand, much more can be done to develop imaginative (and more effective) approaches to addressing the more intractable forms of misconduct, such as electoral violence, boycotts, manipulation of the voter registry, and vote buying.

An interesting new strand of research built around experimental studies provides a clue to a set of interventions that could target these especially stubborn forms of electoral malfeasance, which our analysis has shown are very difficult to combat by means of standard approaches.4fe65663fb86 These studies mostly use randomised controlled trials to investigate an important ingredient of electoral integrity: the provision of information about political choices. On the whole, these studies suggest that providing information can increase political participation, raise demands for accountability, and change preferences and behaviour (Ferraz and Finan 2011; Collier and Vicente 2014). Such effects require a particular type of information, namely valid and objective information about political choices contained in empirically verified facts about politicians, budgets, spending, voting records, and so on.c88256aa6b74 Mechanisms by which this information can be disseminated include text messages, published audits, public speaking platforms, grassroots mobilisations, newspaper report cards, and awareness-raising campaigns.

A number of studies demonstrate that vote buying, for example, is one form of electoral corruption that can be addressed through information provision. For instance, Vicente’s (2014) field experiment in West Africa shows that an information sensitisation campaign against vote buying, sponsored by the electoral commission, was effective in diminishing electoral malfeasance (although it had the perverse effect of reducing voter turnout and favouring the incumbent). Likewise, Fujiwara and Wantchekon’s (2013) experimental study in Benin suggests that holding town hall meetings as conduits for informed public deliberation prior to an election reduces the prevalence of vote buying. Banerjee et al.’s (2011) experimental study found that providing slum dwellers with newspapers containing report cards with information on candidate qualifications and legislative performance reduced the incidence of cash-based vote buying.

Electoral violence is another area that can be addressed through information provision. Collier and Vicente’s (2014) field experiment found that an anti-violence campaign, based on encouraging electoral participation through town meetings, popular theatre, and door-to-door distribution of materials, had a measurable effect on reducing the level of violence and voter intimidation in an election in Nigeria. Aker, Collier, and Vicente (2012) conducted a field experiment during an election in Mozambique and found that three different forms of voter education – an SMS information campaign, an SMS hotline for misconduct, and a free newspaper – had a positive effect on voter turnout. The distribution of the newspaper was also found to reduce electoral problems such as election-day misconduct, campaign misconduct, and violence and intimidation.

However, information is not a panacea, as other studies highlight the limitations of such an approach and suggest the importance of a careful intervention design. Humphreys and Weinstein (2012), for example, examined the effects of an intervention that sought to strengthen parliamentary accountability through the creation and dissemination of a parliamentary scorecard, which provided Ugandan voters with basic information on the activities of their representatives in Uganda’s eighth parliament. In this case, the information did not seem to have a significant effect. The explanations put forward are instructive for the design of these kinds of interventions in the future: they advise that information can be easily manipulated and caught up in a political debate in which the validity of the information is contested. A robust dissemination of information is therefore important. The kind of information that is disseminated is also an important element of intervention design. This is confirmed by Chong et al.’s (2015) experimental study, which shows that a voter-education campaign that focuses just on corruption may have the perverse effect of prompting voters to withdraw from the political process altogether.

Considerations for practitioners: Practitioners should be sensitive to the different components of electoral misconduct during elections and should undertake a comprehensive analysis to discover which kinds of violations are most threatening to integrity and most impervious to reform within a given setting. At the same time, practitioners should take randomised controlled trials seriously and think about developing interventions around the provision of information.

Conclusion

Our findings suggest that, on average, donor-funded electoral assistance programmes have had a beneficial effect on electoral integrity in aid recipients during 2002–15. The magnitude of the effect, however, is rather small and the gains in integrity not very sustainable. These results point to the difficulties of transferring and institutionalising integrity norms in societies dominated by informal power networks. We suggest that, to increase the effectiveness of electoral assistance, donors should structure traditional political economy analysis (and other risk assessment tools) more consistently around the notion of informal norms, institutions, and the overall distribution of power.

Leading observers of donor support for electoral integrity have identified a tendency for donors to put electoral assistance on “autopilot” (Carothers 2015, 64). Carothers, for example, laments that approaches to democracy building have become routine, with donors relying on a standardised menu of interventions that are indiscriminately carried from one setting to the next. Similarly, Bush (2015) has argued that many interventions have become tame through an emphasis on routine technical exercises. Clearly, there is scope for new, more creative and context-sensitive kinds of interventions, especially to target the most stubborn forms of corruption. We therefore suggest a more sustained focus on implementation constraints and a more imaginative approach to programme design.

Our analysis also suggests that the current mix of interventions is generally more effective in promoting electoral integrity in low-income (as against middle-income) societies and in countries that do not currently receive large volumes of (election support) aid. Current interventions are also shown to be able to ameliorate some aspects of integrity (e.g., technical irregularities taking place on election day) more than others. Thus, to increase aid effectiveness in the area of electoral democracy, donors should consider reallocating aid to low-income societies that do not currently benefit from election support programmes. Donors should also target the most amenable aspects of electoral integrity to improve cost-effectiveness, while also considering more imaginative approaches to tackle the more stubborn aspects of electoral misconduct.

Selected further reading

Norris, P. 2017. Strengthening electoral integrity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Today a general mood of pessimism surrounds Western efforts to strengthen elections and democracy abroad. If elections are often deeply flawed or even broken in many countries around the world, can anything be done to fix them? To counter the prevailing ethos, Pippa Norris presents new evidence for why programs of international electoral assistance work. She evaluates the effectiveness of several practical remedies, including efforts designed to reform electoral laws, strengthen women’s representation, build effective electoral management bodies, promote balanced campaign communications, regulate political money, and improve voter registration. Pippa Norris argues that it would be a tragedy to undermine progress by withdrawing from international engagement. Instead, the international community needs to learn the lessons of what works best to strengthen electoral integrity, to focus activities and resources upon the most effective programs, and to innovate after a quarter century of efforts to strengthen electoral integrity.

World Bank. 2017. World Development Report 2017: Governance and the law. Washington, DC.

Why are carefully designed, sensible policies too often not adopted or implemented? When they are, why do they often fail to generate development outcomes such as security, growth, and equity? And why do some bad policies endure? World Development Report 2017: Governance and the Law addresses these fundamental questions, which are at the heart of development. Policy making and policy implementation do not occur in a vacuum. Rather, they take place in complex political and social settings, in which individuals and groups with unequal power interact within changing rules as they pursue conflicting interests. The process of these interactions is what this report calls governance, and the space in which these interactions take place, the policy arena. This report reveals that governance can mitigate, even overcome, power asymmetries to bring about more effective policy interventions that achieve sustainable improvements in security, growth, and equity.

Carothers, T. 2015. Democracy aid at 25: Time to choose. Journal of Democracy 26(1): 59–73.

A quarter century into its existence, international democracy aid has grown considerably and evolved positively in its methods and results, albeit more slowly and partially than one might wish. But international democracy support now operates in a much more difficult international context than before, characterized by significant uncertainty, controversy, and hostility. Western actors engaged in global democracy work face a fundamental choice between pulling back or leaning forward, a choice that will do much to determine whether democracy promotion remains relevant and effective in the face of democratic crisis and democratic breakdown in many parts of the world.

Appendix: Econometric Strategy

This appendix presents our empirical specification in greater detail. We also discuss the identification strategy that we use to estimate a plausible approximation of the causal effect of aid spending on the quality of elections.

- More generally, aid spending for “government and civil society” has also increased, peaking at $17 billion, or 13.5% of total aid flows, in 2009.Authors’ calculations based on data from the OECD, International Development Statistics,2018. All dollar amounts in this paper refer to US dollars.

- Ibid.

- Our dataset provides the best possible coverage given existing data limitations, bearing in mind that donors only began to report disaggregated aid expenditures in 2002 (Clemens et al. 2012, 599).

- To our knowledge, this is the first paper to employ this novel dataset to investigate the aid-integrity nexus.

- For example, an independent evaluation of UNDP’s programme on electoral systems and processes concluded that the organisation’s work was effective in strengthening the technical and logistical capacity of electoral management bodies, especially in post-conflict settings (UNDP 2012). This analysis, however, is based on the work of a single donor agency.

- These studies investigate, inter alia, the effect of a monitoring technology on aggregation fraud (Callen and Long 2015), the impact of an anti-violence campaign on election-related violence (Collier and Vicente 2014), and the ability of observer missions to deter ballot box fraud and count tampering (Ichino and Schuendeln 2012).

- Since electoral assistance programmes seek to address both aspects of electoral malpractice, we do not restrict our analysis to issues of deliberate manipulation, as other authors have done (Bishop and Hoeffler 2016).

- In case of multiple elections held in the same year, the ratings of the integrity of each election are aggregated.

- The figures include grants and “soft” loans (where the grant element is at least 25% of the total) from official sources. They do not include transfers from private sources, such as international non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and charities. While electoral assistance is also provided by private organisations (e.g., election monitoring by international NGOs), most funding for election support is channelled through official donor agencies.

- The DAC is the OECD’s Development Assistance Committee, an international forum that brings together the aid agencies of OECD member countries.

- Authors’ calculations based on data from OECD, International Development Statistics,2018.

- See Uberti (2017) for details of the approach used to derive these figures. For statistical reasons, the models presented so far used the logarithm of aid spending, rather than the absolute value, as the main independent variable.

- This is a country receiving $5.6 million in electoral assistance during election years. These averages are based on the 460 observations used in the regression.

- Income levels, of course, may also exert a direct influence on the quality of electoral democracy. Since income levels change fairly slowly over time in our sample, the income effect is largely captured by the country fixed effects. Additional models (not reported) control for GDP per capita in the regression and lead to qualitatively consistent results.

- These results are robust to correcting for dynamic panel bias. The 2SLS (two-stage least squares) results are available upon request.

- The notion that the informal nature of politics moderates the impact of aid policy is increasingly influential. In World Development Report 2017, for instance, the World Bank acknowledges the importance of informal “elite bargains” in driving political and economic outcomes and moderating the effectiveness of aid policy.

- For instance, due to the lack of a clear class structure defined in relation to property ownership (see Box 1).

- Further lags of the aid variable always turn out to be insignificant.

- Of course, donors should assess, on a case by case basis, the extent to which the interventions described below are truly different from the standard approaches they have implemented so far to combat vote buying.

- A related strand of research demonstrates that the provision of information can reduce the corrupt behaviour of politicians in general. Benito et al.’s (2014)analysis of Spanish municipalities, for example, suggests that rent seeking by politicians increases when voters are less well informed about local political processes. Ferraz and Finan’s (2011)comparative study of the effects of audits of municipality expenditures, which were undertaken and then publicly disseminated by the Brazilian federal government as part of an anti-corruption program in 2003, demonstrates how auditing can discipline politicians to restrain from corrupt behaviour.