Procedural fairness as a principle of decision-making

Civil service reforms aimed at reducing corruption and increasing efficiency of bureaucracies in developing countries have had limited success3679fcf28c56 Most reforms have focused on establishing more efficient bureaucracies in such countries, by improving human resource management through writing job descriptions, setting up functioning payroll systems, and establishing lines of accountability, including independent civil service commissions with responsibility for recruiting, training, and promoting civil servants. Reforms have also included measures to boost transparency and accountability through access to information laws, participatory planning, and budgeting.22b426eac867 However, advocating procedural fairness has not featured prominently as a key element of civil service reforms, even though it has been a component of constitutional reforms in some developing countries.

Promoting procedural fairness is a requirement of Article 10 of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), which states that ‘each State Party shall, in accordance with the fundamental principles of its domestic law, take such measures as may be necessary to enhance transparency in its public administration, including with regard to its organization, functioning and decision-making processes, where appropriate.’

Corruption is often insidious and difficult to prove. However, it can be inferred from opaque decision-making tainted by bias, and other violations of due process. Ensuring procedural fairness is a way to take decision-making out of the shadows where corruption happens and bring it into the light, so that decisions are made in a transparent and accountable manner.

Bureaucrats exercise wide discretionary powers when making decisions, which creates opportunities for illegal, improper, and unfair behaviour that may amount to corruption, ie ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.’8ec638c376b2 According to Klitgaard’s formula for corruption, ‘Corruption equals monopoly plus discretion minus accountability.’62173a4d9a9f The principle of procedural fairness aims to control discretion and enhance accountability in bureaucratic decision-making. It originates from the Common Law and ensures that decision makers are impartial, their decisions are based on evidence that logically supports the facts (and confirmed in writing), and those who will be affected by those decisions participate in their making50e640ba85f4

Therefore, procedural fairness has the potential to improve transparency and accountability in a variety of bureaucratic decisions that are prone to corruption. For example, in granting licences for telecommunications,764bef17a15b construction,f21cd02af566 mining,9469f70596bf logging,b9512fc517d6 schools6acb93346ad5, or health facilities3007e5a1903a to individuals or entities who do not meet, or clearly contravene, the requirements of a licence.

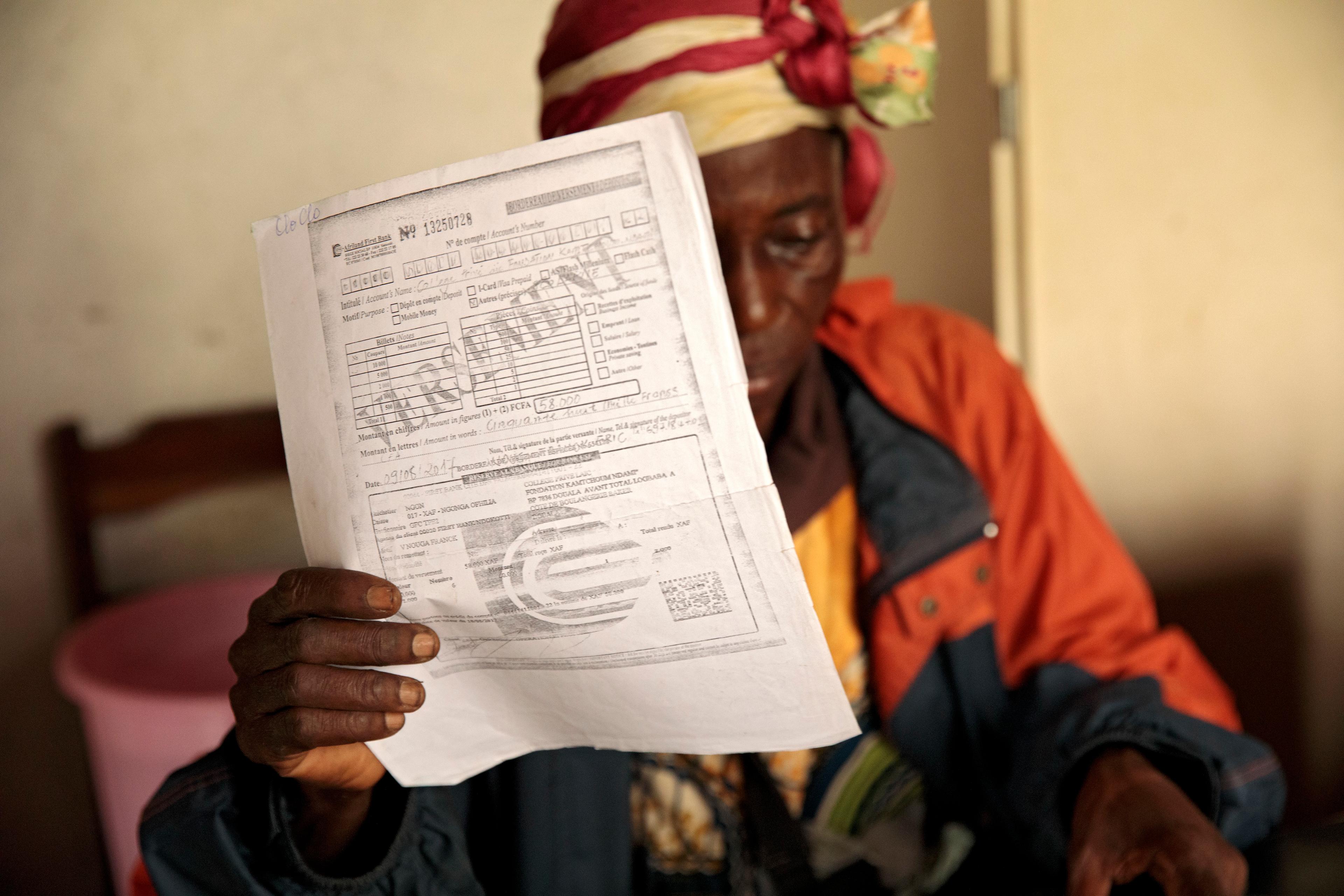

Other types of decisions made by bureaucrats that are prone to corruption include employment and recruitment decisions,8b590e443a19 immigration decisions,7f66b0768331 and tax assessments.230caa028725 Procedural fairness could also apply to decisions concerning the grant or withdrawal of welfare payments and pensions, urban planning decisions, land demarcation, environmental impact assessments and demarcation of electoral constituencies. Virtually any decision made by a public official or body has the potential to affect the rights and interests of individuals and would therefore have to follow procedural fairness principles.

Practical steps to enhance procedural fairness

There are two approaches to realising the principle of procedural fairness.43eff784b3bb The first is to ensure that administrators ‘get it right’ the first time by making decisions that adhere to these principles and procedures. This could be achieved by enacting laws and regulations on administrative procedures, and training administrators how to use them. These procedural laws have two main objectives: enabling those likely to be affected by governmental decisions to participate in their making and hold administrators to account; and facilitating judicial review by requiring administrators to produce evidentiary records, which can then be used to scrutinise their decisions.

The second approach is to ensure that effective redress mechanisms exist to monitor whether procedural fairness has been, or is being, observed. The goal is to correct the errors of administrators when they ‘get it wrong’. Quite often, these two approaches go together.

A key challenge in highly corrupt settings is the absence of individuals who could promote procedural fairness and enforce it, as politicians and bureaucrats will be unwilling to change the status quo since they benefit from it.0d8717450bdb Development partners supporting governance reforms, and civil society organisations working to advance voice and accountability, can play a role in both the supply side of procedural fairness – by advocating its enactment and training bureaucrats to uphold it,d8cd3da76bab and the demand side – by empowering citizens to call for it and seek remedies when it is violated.

Getting it right through robust legislation

Kenya, Malawi, Zimbabwe, Uganda, and South Africa have strengthened the requirement for procedural fairness in bureaucratic decision-making by enshrining it in their Constitutions and /or enacting a specific law.393147bb9be3 As mentioned above, procedural fairness is a Common Law principle. However, its application based on Common Law is fraught with several problems, especially the lack of a clear legal basis on which to challenge bureaucratic decisions. Lawyers have to do extensive research to find judicial precedents to support a legal action, and judges can use their discretion to distinguish between different situations and decide to uphold procedural fairness in some cases but not in others.86c8304ef562

Enacting specific legislation that gives the courts powers to check executive excess through Constitutions and Fair Administrative Action Statutes presents a new opportunity to promote transparent and accountable decision-making. This is because, in Commonwealth countries, the law operates according to a hierarchy: the Constitution is the Supreme Law; Acts of Parliament come second; Common Law (or Case Law) and Equity are third; and fourth is unwritten Customary Law.

For instance, section 3 of the Judicature of Act of Kenya, confirms the hierarchy of law that courts should apply in decision-making. Firstly, the Constitution of Kenya; secondly, the written laws (including Acts of Parliament); thirdly, Common Law and Doctrines of Equity; and lastly, African Customary Law.6c239c3100e9 Also, the Common Law should apply only when the circumstances and its people permit. This shows that procedural fairness principles previously occupied a tenuous position in the legal hierarchy, making them difficult to enforce since they were part of the Common Law and its problematic colonial legacy. Therefore, elevating procedural fairness to a constitutional right and making it a mandatory legal requirement by enshrining it an Act of Parliament raises its importance and makes it easier to enforce.

The statutory requirement that bureaucrats should provide written reasons for their decisions takes it even a step further. Written reasons are indispensable to fair decision-making because, as Kinchin observes, ‘Accountability is of minimal value when it is not being seen to be done by those whom the public service is accountable to.’85a349a5d01b Written decisions are important because the affected party can see how a decision has been reached and what factors have been considered. The potential for judicial, as well as public, scrutiny of the decision forces the decision maker to thoroughly think through his or her decision, apply the law correctly, and justify that decision on the available facts and evidence. Accordingly, the requirement for written decisions encourages better decision-making that is not only administratively sound, but also less likely to be tainted by corruption.

The legal requirement for procedural fairness has been established in Kenya with the Fair Administrative Action Act 2015 (‘the Act’), which gives effect to the constitutional requirement for just and fair administrative decision-making. Zimbabwe enacted the Administrative Justice Act in 2004.14857ceddd0f South Africa’s Promotion of Administrative Justice Act (PAJA) has been in effect since 2004.57432fdf120a Malawi and Uganda are yet to enact legislation to give effect to the constitutional provision for procedural fairness in administration action.

Kenya’s law provides an elaboration of procedural fairness and a broad definition of ‘administrative action’, which includes ‘the powers, functions and duties exercised by authorities or quasi-judicial tribunals,’ and ‘any act, omission, or decision of any person, body or authority that affects the legal rights or interests of any person to whom such action relates.’d782e924901b This definition embraces both public and private administrative action, and the Act therefore applies to both state and non-state agencies. Further, it defines ‘decision’ as not only administrative decisions already made, but also those being proposed. It is sufficiently broad to enable affected individuals and civil society organisations undertaking public interest litigation to rely on it.

Section 4 of the Act provides substantial provisions as to what constitutes procedural fairness.6beee28a59b8 Every person has the right to efficient, lawful, and procedurally fair administrative action, and to be given written reasons for any action taken against them. Where it is likely to adversely affect their rights or fundamental freedoms, they shall be given adequate notice of its nature and the reasons for it; an opportunity to be heard, with the right to legal representation and to cross-examine; notice of the right to a review or internal appeal; and a statement of why the action was taken together with the relevant information, materials, and evidence that were relied upon in making the decision or taking the administrative action.

The Act further states that the person against whom administrative action is taken has the opportunity to attend proceedings (in person or in the company of an expert); be heard; cross-examine persons who give adverse evidence against them; and request an adjournment of the proceedings, where necessary, to ensure a fair hearing.

These provisions allow citizens to participate in bureaucratic decisions, either individually or with others who are affected by the decision. The law promotes their active participation – not just through attendance, but through the ability to bring evidence and, even, to be advised by an expert. This has the potential to curtail corruption if civically minded citizens, with a stake in various types of bureaucratic decisions, monitor the decision-making processes and ensure that they are proper, just, and fair. They can then challenge decisions deemed to violate these principles in the courts of law.

On the supply side, bureaucrats operating in jurisdictions where Fair Administrative Action Statutes apply are now compelled to be more meticulous when making decisions. If the law is adhered to and enforced, it will be more difficult to make corrupt decisions.

Redress for violations of procedural fairness

One of the most important elements of the principle of procedural fairness is that disaffected individuals can challenge the decisions of bureaucrats through the courts of law.a617fd610c01 It is argued that the prospect of judicial review of such decisions can encourage proper decision-making by instating ‘a judge over the bureaucrat’s shoulder.’0a6397baf786 A person or entity dissatisfied with an administrative decision can apply for judicial review and a specific remedy, such as certiorari, quashing the decision; prohibition, preventing an unlawful decision from being carried out; mandamus, commanding the performance of a legal duty; injunction, stopping a public body from doing something; a declaration as to the rights of both parties; or damages if harm resulting from the decision is proved.096e846570ff

Generally, judicial review of administrative decisions is concerned with how a decision was reached, as opposed to its merits. Therefore, it can be useful for monitoring whether the principles and procedures of Administrative Law, such as procedural fairness, have been observed.d53807a5a4c8 It is based on the assumption that administrative agencies will not wish to be exposed by the courts for maladministration. This fear of bad publicity gives administrators an incentive to observe the principles and procedures of Administrative Law. Secondly, individual case inspection can help administrators whose decisions or practices have been reviewed adversely to improve. Court decisions can expose administrative failing and subsequently stimulate reform and promote good administration.

Section 7 of the Act details actions that constitute violations of procedural fairness and which would be grounds for judicial review.89b8334a3214 These comprehensive grounds can be used to challenge corrupt decisions involving power abuse, nepotism, and favouritism. The Act unpacks or disaggregates the grounds of judicial review in a manner that administrators can appreciate. They will know, in advance, what is expected of them while exercising power, and what the rules are as they make decisions. In the future, this approach could be enhanced by communicating guidelines on administrative decision-making and training bureaucrats to follow them.

Obstacles to enforcing procedural fairness

The potential of procedural fairness to curtail corruption in bureaucratic decisions faces several challenges:

Political and bureaucratic resistance

Procedural fairness is bound to encounter political and bureaucratic resistance because it threatens the interests of power holders. Such resistance, which has already been experienced in relation to reforms in computerisation, citizen engagement, and parliamentary scrutiny, is one of the biggest hurdles to institutionalising procedural fairness.bc547822079b In many African countries the administrative culture, since independence, has evolved around certain values such as loyalty, unquestionable respect for ‘elders’, and people in authority.afed770d9f9a Yanguas argues that administrative compliance with the rules governing decision-making is almost non-existent because ‘almost by definition one cannot have a highly corrupt state that formally monitors and sanctions itself.’7b321baa78eb

However, the substantial increase in judicial review applications challenging arbitrary administrative decisions in countries such as Kenya shows that the situation is not intractable, that citizens are less afraid to take on the government, and that governments care about their reputation. Indeed, Yanguas says that there is some evidence of the increasing professionalisation of bureaucracies in some developing countries, such as Rwanda and Ethiopia.

Lack of awareness and ignorance of the law

Many citizens are still ignorant of the law and face challenges in accessing justice, such as expensive legal fees and a substantial distance between their homes and justice institutions (eg lawyers’ offices).82d67268f7f0 The United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 16.3 states: ‘Promote the rule of law at the national and international levels and ensure equal access to justice for all.’7cc15a79999d Strengthening legal aid and empowerment of the population is therefore a necessary pre-condition for the enforcement of procedural fairness in administrative decision-making.0f7e93032e7c

Lack of access to justice

The question of whether courts are impartial when reviewing administrative decisions cannot be ignored. Transparency International reports that out of six public services, people who encountered police and the courts were most likely to have paid a bribe.f830680f3056 Yet, the enforcement of procedural fairness depends on the independence and integrity of the courts. This should, however, not be seen as an insurmountable obstacle. As the importance of procedural fairness lies mainly in its potential to improve decision-making processes – through the ‘judge over the bureaucrat’s shoulder’ – and not necessarily outcomes, then the threat of judicial scrutiny could cause public officials to make decisions in a fair and transparent manner.1d010268b359 There are several cases, from countries such as Kenya, where citizens have successfully challenged unjust decisions (see Appendix).

Enabling factors for procedural fairness

Legal guarantees of procedural fairness

Enshrining the right to fair administrative action in the Constitutional Bill of Rights helps to clarify the Common Law position and provides a stronger basis for citizens and courts to enforce this right. An Act of Parliament that establishes the right to procedural fairness, and how it can be enforced, is a step further in enabling citizens to obtain appropriate remedies in instances of violation.f055ed5e59aa

Islands of integrity and bureaucratic effectiveness

Despite the persistence of corruption, research on countries such as Ghana shows a more complex picture, with increased emphasis on meritocracy and ‘islands of bureaucratic effectiveness’ or ‘pockets of efficiency’.9057de80264a Such ‘islands’ also exist in notoriously corrupt countries such as Uganda, in the dairy sector and in revenue collection.54c518ba5a35 Thus, procedural fairness in bureaucratic decision-making can be strengthened where the political patronage system favours effectiveness and efficiency. Training public officials to build their capacity to make decisions in accordance with procedural fairness would ensure that the principles are adhered to where there is political will for this to happen.

Access to information and whistleblowing

Access to information and fair administrative action or procedural fairness are mutually reinforcing aspects of public sector governance. Procedural fairness would ensure that the reasons for public decisions exist in written form; access to information brings both the process and the decision to light. Over the past two decades, around 120 countries have passed laws or national policies requiring public bodies to proactively publish information about their activities and respond promptly to requests for information.03852963409b Fair Administrative Action laws are less common but should be encouraged. Whistleblower protection provisions would also enable insiders, ie concerned public officials, to monitor fellow bureaucrats and raise the alarm when procedural fairness is violated.

Legal aid and legal empowerment

Petitioning the courts to review unfair administrative decisions is an exercise that requires legal expertise. Aggrieved citizens who cannot afford legal services would require legal aid to enforce the right to procedural fairness in such decisions. They would have to know that they had such a right – and that such right had been violated – in order to approach legal aid organisations for redress. Legal and rights awareness education programmes would empower them to do so. In Common Law countries, especially where procedural fairness is constitutionally guaranteed, human rights awareness programmes, rights-based approaches, anti-corruption education initiatives, legal empowerment, and social accountability programmes should therefore incorporate procedural fairness and its potential in curbing the abuse of power.

Judicial Independence

Judicial independence is required by international law and the consitutions of many developing countries espouse judicial independence.7b1c9826e9c9 In practice, however, there are several threats to judicial independence such as direct physical attacks on court premises and individual judges6ca6d648bcba and disregarding court orders. Despite these challenges, judiciaries in developing countries have shown willingness to assert their independence and challenge wrongful behaviour by the executive branch of government.5ccfdd3490d9 The appendix shows examples of cases where judges have ruled against wrongful bureaucratic decisions.

Conclusion

The enactment of Fair Administration Action laws in countries such as Kenya, South Africa, and Malawi, has the potential to improve bureaucratic decision-making and reduce abuse of power. However, further empirical research on how these laws are being enforced in political contexts with varying degrees of democracy would help assess their impact and ascertain what further improvements should be made to promote a culture of transparent and accountable decision-making by bureaucracies in developing countries.

Although not a perfect solution, the passing of laws is an important first step that can influence long-term adherence to the rule of law.An Act of Parliament that mandates fair administrative action can provide citizens and activists with a normative basis for their advocacy efforts to have a greater voice in decision-making. It can strengthen social accountability by providing a sanctions and redress mechanism where wrong-doing has occurred. Also, it can improve contestability, by ensuring that the interests of previously excluded groups are taken into account in decisions that affect them.c7af9cce8f2c

Recommendations

Bilateral donors should:

- Support legislative reform for Fair Administrative Action laws and capacity building of bureaucracies to adhere to procedural fairness

- Encourage civil society voice and accountability initiatives to consider procedural fairness as an area for strengthening social accountability and improving transparency and accountability in the public sector

- Advocate legal aid and legal empowerment for citizens to enforce their rights to procedural fairness

- Promote further research on procedural fairness and its application

Appendix

Examples of cases where procedural fairness has been enforced through the courts of law

Over the years, in Commonwealth countries, procedural fairness has been the subject of various court actions where individuals have challenged government agencies concerning bureaucratic decisions that they deemed unjust or improper. While the examples are not explicitly about corruption, they illustrate how procedural fairness principles can work indirectly to curtail corrupt, arbitrary, and unjust decisions by public officials.

Malawi: Magistrates challenge recruitment decision and procedure by the Judicial Service Commissiona52fcc26da0d

In 2018, Jamison Chakuma, Henry Zimba, Joseph Muweta, Mike Lungu, Issa Eddie Salanje, and several other Court Clerks employed by the Malawi Judicial Service Commission, filed an application for judicial review against the Commission and the Chief Justice of Malawi. In contravention of the Courts Act, the Commission filled vacancies for Third Grade Magistrates (TGMs) by inviting applications from outside the Judicial Service when there were qualified and suitable officers within the Judiciary. As claimants in this case, they had upgraded their education under a legitimate expectation that this would qualify them for such promotion. They sought an order of certiorari to quash the decision to appoint new TGMs contrary to relevant Public Service law regulations, which allowed vacancies to be advertised internally and was a breach of the claimants’ right to a legitimate expectation of promotion under section 43(b) of the Constitution of Malawi. They also asked the Court to grant them an order akin to mandamus compelling the Chief Justice to appoint the claimants as TGMs.

Considering the evidence, Justice Ntaba of the High Court of Malawi found that the Commission had no formal or well-established human resources policy for the appointment or recruitment of judicial officers such as magistrates, including regulations on whether vacancies were to be advertised internally or externally. The Court observed that the lack of clear regulations had created this situation ‘where decisions on the appointment or recruitment of magistrates is not clear, unambiguous nor consistent despite the recruitments being based on merit when conducted. This practice is in my considered view is wrong in law.’ The Court granted the claimants’ order for judicial review and recommended that the Commission review the recruitment process and ensure that it fulfilled the requirements for procedural fairness. The Court, however, did not grant the orders of mandamus or certiorari, arguing that they were not appropriate for this case as they could only be issued against an inferior tribunal or authority.

The case nevertheless illustrates how procedural fairness and judicial review can be used to advocate proper decision-making in recruitment and promotion – areas where wide discretion and ambiguous rules leave room for corruption.

Kenya: Concerned citizens challenge the appointment of Constituency Returning Officerscb787bf0e1ad

Registered voters Khelef Khalifa and Hassan Abdi Abdille, describing themselves as ‘public spirited citizens’, applied for an order of certiorari to quash a decision of the Kenya Independent Elections and Boundaries Commission in 2017, regarding the appointment of Constituency and Deputy Constituency Returning Officers for the 2017 general elections. The claimants alleged that the appointment decision was made unilaterally and in bad faith. It was in breach of the Constitution and the law as it did not follow the law and had ignored the need for transparency and accountability. Specifically, several political parties and independent candidates had not received the list of proposed officers. This denied them the opportunity to make representations on the appointed persons. The applicants believed that the process of their appointment was therefore illegal, procedurally unfair, and violated the basic tenets of the rule of law and the Fair Administrative Action Act, as well as the constitutional provision that ‘all power belonged to the people’ and must be exercised with their participation.

The Court agreed that the Commission acted in violation of the law but did not grant the order because it would be against the public interest to interfere with and possibly derail the election process, as the election was only a few days away at the time of judgment.

This is an example where political concerns over the impact of quashing a bureaucratic judicial decision held sway. Although the appointment of returning officers did not involve the various political parties, thereby creating a risk that the officers could have been biased in favour of the incumbent ruling party, the Court was not willing to revoke their appointment because it would have derailed the election process. Nonetheless, the example illustrates that is possible to challenge arbitrary decisions possibly motivated by favouritism.

Kenya: Attempt to close refugee camps and repatriate Somalian refugees declared null and void by the courtbf0cddf8bb55

On 9 February 2017, the High Court of Kenya at Nairobi declared that the government’s decisions to close the Dadaab refugee camp without first consulting stakeholders and to forcibly repatriate its Somali refugees were unconstitutional. In addition to Refugee Law, the Court also considered the issue of whether the government’s decisions violated the constitutional right to fair administrative action. The Court noted that the Fair Administrative Action Act elaborates the constitutional right to fair administrative action and stipulates grounds for challenging a particular action. The Act states that if an administrator is preparing to take an action that ‘is likely to adversely affect the rights or fundamental freedoms of any person,’ the administrator must, among other things, provide ‘prior and adequate notice,’ an opportunity to be heard, notice of the right of review and appeal, reasons for taking the administrative action and all the relevant material, and notice of the right to legal representation. The Court decided that the decisions of the government had violated the fair administrative action clause of the Constitution (Article 47), as well as the Act, and stated that the decisions were ‘ultra vires, null and void.’

Kenya: Opposition politician challenges revocation of firearm licencee50cb736773e

Opposition politician Johnson Muthama received a notice from the Firearms Licensing Board in early 2018 saying that his firearm licence had been revoked on the basis that he ‘had been found…unfit to be entrusted with a firearm anymore.’ He had held the licence since 1990 and had never been involved in an incident with a firearm or been convicted of any offence. He argued that the Board had given no reasons for its decision and was thus not lawful. Moreover, he had not been given an opportunity to be heard regarding the cancellation of his licence, and therefore the actions of the Board were arbitrary and in breach of the Firearms Act, the Constitution, and the Fair Administrative Action Act.

In her judgment, the Judge observed that the law required the Board to be ‘satisfied’ about the circumstances that were necessary to cancel someone’s licence, but there was nothing to indicate how it had ‘satisfied’ itself. Therefore, it had wrongly exercised its powers, and the notice was illegal due to ‘procedural impropriety and unfairness’ in making the decision. The Judge made an order prohibiting the Board from revoking the licence ‘without following due process’ and complying with the Constitution and the Firearms Act.

The examples illustrate the potential uses of procedural fairness requirements to curb corruption by:

- Promoting meritocratic recruitment and fair civil service management Appointments, promotions, transfers, and terminations of public officials are prone to nepotism, favouritism, and similar forms of bias. Those with authority often appoint public servants with particular political leanings or from favoured ethnic backgrounds.3b52da655cbe Ensuring procedural fairness in appointments and other aspects of civil service management could curtail these tendencies.

- Advocating transparency and accountability in licensing procedures

Citizens can use procedural fairness requirements to challenge licences that have been granted corruptly to the detriment of citizens. - Reducing opacity and impunity in bureaucratic decision-making

Sometimes, governments make arbitrary decisions for unclear reasons, as happened with the Kenyan government’s closure of the refugee camp. While the decision may not have necessarily been tainted by corruption, the example shows how such decisions, whether tainted by corruption or not, can be challenged and stopped.

- Yanguas, P. and Bukenya, B. 2016. ‘New’ approaches confront ‘old’ challenges in African public sector reform. Third World Quarterly 37(1): 136–152.

- European Commission. 2009. Public sector reform: An introduction. Tools and Methods Series Concept Paper No. 1.

- Definition commonly used by Transparency International.

- Klitgaard, R. 1998. International cooperation against corruption. Finance & Development 35(1).

- Australian Government. What is procedural fairness?

- Wickberg, S. 2014. Overview of corruption in the telecommunications sector. U4 Helpdesk Answer 2014:06. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute.

- Curbing Corruption. 2019. Construction and infrastructure.

- U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre. Basic guide to corruption in oil, gas and mining sectors.

- Earthsight. 2018. Complicit in corruption: How billion-dollar firms and EU governments are failing Ukraine’s forests.

- Mobarak, H. 2017. School inspection challenges: Evidence from six countries. UNESCO.

- Hussmann, K. 2011. Addressing corruption in the health sector: Securing equitable access to health care for everyone. U4 Issue 2011:1. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute.

- Bureaucrats contravene public service recruitment guidelines and make decisions based on favouritism and nepotism.

- U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre. Basic guide to corruption and migration.

- Bridi, A. 2010. Corruption in tax administration. U4 Helpdesk Answer 229. Bergen: U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre, Chr. Michelsen Institute.

- Akech, M. 2016. Administrative law. Nairobi: Strathmore University Press, p. 29.

- Fritzen, S. 2005. Beyond ‘political will’: How institutional context shapes the implementation of anti-corruption policies. Policy and Society 24(3): 79–96.

- In line with this, there are published detailed guides on procedural fairness for bureaucrats from the UK, New Zealand, Hong Kong, Kenya, Malawi, and South Africa. See: Currie, I. et al. 2018. The Promotion of Administrative Justice Act Administrators' Guide. University of Witwatersrand, Justice College and GIZ; Katiba Institute. 2018. Fair Administrative Action under Article 47 of the Constitution. (A guide for the administrator with some guidance for the public on what to expect and how to complain.); UK Government Legal Department. (n.d.). The judge over your shoulder: A guide to good decision-making.; Government of Hong Kong Department of Justice. 2019. The judge over your shoulder: A guide to judicial review for administrators.

- Article 42 of the Constitution of Uganda 1995; Article 43 of the 1994 Constitution of Malawi; Article 47 of the 2010 Constitution of Kenya; Article 68 of the 2014 Constitution of Zimbabwe; Article 33 of the 1996 Constitution of South Africa.

- Chirwa, D. 2011. Liberating Malawi's administrative justice jurisprudence from its Common Law shackles. Journal of African Law 55(1): 105–127.

- The Judicature Act, Chapter 8, Laws of Kenya.

- Kinchin, N. 2007. More than writing on a wall: Evaluating the role that codes of ethics play in securing accountability of public sector decision‐makers. Australian Journal of Public Administration 66(1):112–120.

- See also Kushner, H.L. 1985. The right to reasons in administrative law. Alberta Law Review 24: 305.

- Kenya Fair Administrative Action Act 2015; Zimbabwe Administrative Justice Act 2004

- South African Promotion of Administrative Justice Act No. 3 of 2000

- Section 2 of the Kenya Fair Administrative Action Act, 2015.

- Section 4 of the Kenya Fair Administrative Action Act, 2015.

- This is articulated in Article 42 of the 1995 Uganda Constitution; Article 43 of the 2006 Malawi Constitution; and Section 7 of the 2015 Fair Administrative Action Act of Kenya.

- Bingham Centre for the Rule of Law. 2016. The UK’s judge over your shoulder: A model for Kenya?

- Corwin, E.S. 2017. The doctrine of judicial review: Its legal and historical basis and other essays. Routledge.

- McMillan, J. 2009. Can administrative law foster good administration? Whitmore Lecture.

- Section 7 of the Kenya Fair Administrative Action Act, 2015.

- Akech, M. 2015. Evaluating the impact of corruption indicators on governance discourses in Kenya. In The quiet power of indicators: Measuring governance, corruption, and rule of law, Merry, S.E., Davis, K.E., and Kingsbury, B. (eds) 248–283. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Karyeija, G.K. 2010. Performance appraisal in Uganda’s civil service: Does administrative culture matter? PhD dissertation. Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Bergen.

- Yanguas, P. 2017. Varieties of state-building in Africa: Elites, ideas and the politics of public sector reform. Effective States and Inclusive Development (ESID). Working Paper 89, p.7.

- Danish Institute for Human Rights. 2011. Access to justice and legal aid in East Africa. A comparison of the legal aid schemes used in the region and the level of cooperation and coordination between the various actors.

- Sustainable Development Goals Knowledge Platform. SDG 16.

- OECD. 2016. Leveraging the SDGs for inclusive growth: Delivery access to justice for all.

- Schütte, S.A., Reddy P., and Zorzi, L. 2016. A transparent and accountable judiciary to deliver justice for all. U4 Anti-Corruption Resource Centre and UNDP. See also Transparency International. 2015. Global Corruption Barometer Africa Report.

- Oliver, D., 1989. The Judge Over Your Shoulder. Parliamentary Affairs, 42(3), pp.302-316.

- Tuya, J.M. 2018. Unlocking the revolutionary potential of Kenya's constitutional right to fair administrative action. Doctoral dissertation. University of Cape Town.

- Rasul, I., Rogger, D., and Williams, M.J. 2018. Management and bureaucratic effectiveness: Evidence from the Ghanaian civil service. World Bank Group. Policy Research Working Paper 8595.

- Kjær, A.M. 2015. Political settlements and productive sector policies: Understanding sector differences in Uganda. World Development 68: 230–241.

- Article 19 and UNCAC Civil Society Coalition. Fighting corruption through access to information.

- Article 14, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, 1966. See also, Article 160(1) of the Constitution of Kenya, 2010.

- In Uganda, military personnel attacked the High Court to prevent the release on bail of two suspects suspected of belonging to a rebel group. See International Bar Association, 2007. Judicial independence undermined: A report on Uganda, p.25.

- For instance, the judiciaries of Kenya and Malawi have recently annulled presidential elections marred by irregularities. For an earlier academic analysis on the issue, see VonDoepp, P., 2005. The problem of judicial control in Africa's neopatrimonial democracies: Malawi and Zambia. Political Science Quarterly, 120(2), pp.275-301.

- World Bank. 2017. Op. cit.

- S v Judicial Service Commission and Another (Judicial Review No. 22 of 2018) [2019] MWHC 34 (04 February 2019).

- Republic versus Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission ex parte Khelef Khalifa and Hassan Abdi Abdille, Miscellaneous Application 628 of 2017 High Court of Kenya.

- Kenya National Commission on Human Rights & another v Attorney General & 3 others [2017] eKLR.

- Republic versus Secretary of the Firearms Licensing Board, Firearms Licensing Board and Attorney General, Judicial Review Application No. 43 of 2018.

- Ijewereme, O.B. 2015. Anatomy of corruption in the Nigerian public sector: Theoretical perspectives and some empirical explanations. Sage Open 5(2). See also Matheson, A. et al. 2007. Study on the political involvement in senior staffing and on the delineation of responsibilities between ministers and senior civil servants. OECD Working Papers on Public Governance 2007/6. OECD Publishing.