Query

What are the main risks for corrupt practices in labour market policy, social dialogue and employment services? How can these risks be mitigated?

Caveat

The extent and forms of corruption that can affect the work of employment services depend on a range of variables, including country context, institutional structure and working practices.

Identifying an exhaustive list of corruption risks that could occur in the various settings where employment services are carried out is thus not only beyond the scope of this Helpdesk Answer but also relatively futile. Instead, this paper provides a framework to understand the various corruption risks that employment services in particular and labour market policies in general may be exposed to and showcases several mitigation measures that could be applied to reduce vulnerabilities.

Background

The International Labour Organisation (ILO) states that current labour economics is increasingly concerned with labour market institutions and regulations as well as their interactions with, and their impact on, different economic and labour market outcomes (ILO 2021b). Labour market regulations may affect areas such as wage setting institutions, mandatory social benefits, the unemployment insurance system, as well as different aspects of labour legislation (legal minimum wage, employment protection legislation and the enforcement of the legislation) (ILO 2021b).

Labour market policies (LMPs) can be understood as various types of regulative policies that influence the interaction between labour supply and demand (ILO 2021b). While usually focused on lowering the obstacles to employment, the basic elements of LMP instruments could be understood in terms of “demanding” that the unemployed actively seek and accept jobs on one hand, while “enabling” elements believed to increase the employability, productivity and ultimately attractiveness of jobseekers to employers on the other (Theodoropoulou 2018).

Other than these dichotomous tasks, LMPs also involve strategies that provide income replacement (usually called passive labour market policies) as well as labour market integration measures available to unemployed people or those threatened by unemployment (ILO 2021b).

In terms of enabling elements aimed at increasing employability, LMPs can involve (Bonoli 2010):

- incentive reinforcement measures to strengthen the work incentives for benefit recipients

- employment assistance measures to remove obstacles to labour market participation

- occupation measures to keep unemployed people occupied to prevent the loss of their human capital

- vocational training or measures providing basic education to enhance the skills of those who were unable to acquire sufficient training in the past or who need reskilling

When it comes to the cost, incentive reinforcement and employment assistance tend to be less expensive than occupation and training measures (Bonoli 2010). Theodoropoulou (2018) suggests that employment assistance together with incentive reinforcement and wage subsidies to employers in the private sector tend to be more effective than job creation in the public sector. Other areas that LMPs have focused on include supplementing the income of the working poor and improving social protection, including access to unemployment benefits for those workers under “atypical contracts or career trajectories” who would not usually qualify for support under the unemployment insurance systems (Theodoropoulou 2018).

A distinction can also be drawn between “old” and “new” labour market policy instruments. While the former comprises of passive benefits replacing the income of qualifying unemployed workers and employment protection legislation, the latter concentrates on “active labour market policies”a2a59164b7e0 (ALMPs), including investment in training and human capital formation, and “needs-based” income support for those unemployed on a long-term basis.

To better grasp how labour markets operate, it is important to bear in mind that, depending on varying contexts, laws governing employment conditions, such as job security and social protection to workers, are not necessarily applied uniformly to all workers, and the differing degree of their application results in the segmentation of labour markets (Papola 2013). The layers of differentiation can also be complex – going beyond the typical dichotomy of formal and informal sectors (Papola 2013). The Indian labour market is a good illustration of this as it contains several layers of segmentation based on size of the organisation, categories of workers (i.e., contract, permanent, casual, temporary, etc.) and presence of unions (Papola 2013).

Despite the various idiosyncrasies of national labour markets and LMPs, employment services are a key common component. According to ILO (2021a), employment services “promote an efficient development, integration and use of the labour force”. Public employment services are one of the major conduits for implementing employment and labour market policies (ILO 2021a). Given the challenges of today’s labour markets, public employment services are wrestling with an increasingly complex range of issues — from chronic unemployment or under-employment to demographic shifts and the impact of digital and technological evolution (ILO 2021a).

While public employment bodies continue to play a significant role in enabling active LMPs, the ILO (2021a) argues that the emergence of private employment services, where appropriately regulated, could offer new opportunities for cooperation in delivering employment services, notably by increasing outreach to new groups in the labour market. Similarly, the ILO (2021a) advocates for public employment services to partner with not-for profit and non-governmental institutions to expand coverage and provide additional services to specific target groups.

Social dialogue

One method of improving labour market outcomes is social dialogue. Social dialogue is defined by the ILO as “including all types of negotiation, consultation or simply exchange of information between, or among, representatives of governments, employers and workers on issues of common interest relating to economic and social policy” (European Commission 2017). In the European context, for example, social dialogue refers to discussions, consultations, negotiations and joint actions involving organisations representing the two sides of industry (employers and workers). It takes two main forms (European Commission 2017):

- a tripartite dialogue involving the public authorities

- a bipartite dialogue between the European employers and trade union organisations; this takes please at cross-industry level and within sectoral social dialogue committees

Social dialogues can also take place at various scales (European Commission 2017):

- cross-industry social dialogue, which brings together representatives of employers (including business associations) and employees (particularly trade unions) at the national or even international level to discuss issues related to the whole economy and the labour market in general

- sectoral social dialogue is where both sides from a given industry meet to discuss on sector specific issues

- company level social dialogue are discussions between the employer and representatives of employees (including works councils). In the case of multi-national enterprises, such works councils can be transnational in nature and include negotiations with the employer on matters including restructuring, corporate social responsibility, equality, and health and safety.

ILO (2020c) notes that “sound industrial relations and effective social dialogue contribute to good governance in the workplace, decent

work, inclusive economic growth and democracy. [Therefore] they can also be important means of advancing gender equality and fair labour markets, and vice versa.”

Labour market policies during the COVID-19 pandemic

In the context of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, active labour market policies and employment services have played – and continue to play – an important role in cushioning income losses, protecting existing jobs, facilitating employment and promoting labour market attachment (ILO 2020a). Since the beginning of the crisis, national policies have prioritised income compensation for workers and sought to reduce the risk of more job losses through mechanisms such as (ILO 2020a):

- job preservation programmes: short-term work compensation has been used primarily as a massive transfer programme for workers affected by the sharp reductions in economic activity brought on by COVID-19; measures have included expanding coverage and relaxing eligibility criteria

- targeted recruitment in essential sectors: dedicated job-matching services, often delivered through web-based job-matching systems to minimise the risk of contagion.

- employability-oriented services to maintain labour market participation: some countries have reinforced support for target groups in need of improving digital skills and have used digital technology to ease access to free skills training and online learning tools and resources

Corruption and labour market outcomes

Certain operational corruption risks, such as nepotism in hiring practices, are common to employment agencies in a wide variety of countries. Nevertheless, the background political economic conditions, such as the quality of institutions and the rule of law, in which active labour market policies are implemented matter considerably in determining the extent and nature of corrupt practices.

Background levels of corruption are also important determinants of the composition and characteristics of labour markets. For example, in countries with a high prevalence of corruption, the quality of public investment is typically poor, resulting in lower growth and income, which in turn impedes job creation in the long run (Lim 2017). Findings from middle-income economies show that measures designed to lower long-term unemployment can prove ineffective in settings characterised by weak administrative capacity and poor governance, both of which are hallmarks of economies with a high incidence of corruption (Lim 2017).

As for other macro-economic factors, Baklouti and Boujelbene (2019) find that countries with a large shadow economy are disproportionately affected by corruption’s corrosive effect on economic growth. Thus, while some of the second-order effects of corruption on the labour market may be indirect, they clearly influence the economic conditions in which employment services operate. Dutta et. al (2011) argue that strong bureaucratic interference and corruption at every stage of economic activity is one of the main reasons behind high participation in informal and unregulated sectors. Similarly, environments with high levels of informal economy contributes to corruption in a way that officials are less likely to follow procedure and be more inclined to be corrupt as informal agreements are more likely to place (Dutta et. al 2011).

Moreover, corruption also has direct negative effects on the labour market. A study on the labour force participation rate (LFPR) using panel data from 132 countries finds empirical support for the claim that corruption has a significant and robust negative effect on labour supply (Cooray and Dzhumashev 2018). The authors propose that this is due to the fact that corruption reduces productivity, alters the tax burden and leads to an increase in economic activity in the informal sector at the expense of participation in the formal sector.

The study also points to the importance of fiscal policy in terms of tax collection and the provision of public goods as a means of increasing the labour supply in the formal economy. This can be done by enhancing productivity and indirectly reducing the relative attractiveness of activities in the shadow economy (Cooray and Dzhumashev 2018). The authors argue that policymakers should therefore adopt a two-pronged approach to reduce the negative impact of corruption on LFPR: prioritise anti-corruption measures while simultaneously working to improve the quality of labour market regulation.

What becomes apparent is that curbing corruption is a potentially powerful way to increase access to formal employment by allowing allow people to take advantage of labour market opportunities that arise. Conversely, improving the quality of labour market policies also has the potential to encourage the development of human capital and improve social cohesion, which can reduce incentives for corruption as a consequence (Lim 2017). Insofar as strengthening institutions and public employment services can support the growth of the formal sector, this has the potential to also reduce workers’ exposure to corrupt practices.

Understanding corruption in the value chain

There are various ways to assess potential corruption risks in LMPs. The application of any given corruption risk assessment framework to a particular labour market would require extensive in-depth research, and thus goes beyond the scope of this answer.

Given the breadth of LMPs, this paper will focus on the process of providing employment services, in other words matching demands from employers to jobseekers. Analysing a typical value chain related to the provision of employment services helps shed light on potential corruption risks to which the sector may be vulnerable at the various stages of its operations.

As noted above, the nature of labour markets – and hence the severity and type of corruption encountered – differs across contexts (see Papola 2013). While much of the literature on labour markets relates to industrialised economies, employment services in the Global South can look quite different from those in the EU in the extent of informal employment and workers’ rights, as well as other factors that can bring distinct corruption risks.

Similarly, public employment services may face qualitatively different corruption risks to employment services managed privately due to the types of actors and organisational processes involved. Thus, any robust assessment of corruption risks at various stages of the employment services value chain needs to be customised to cater to the specificities of a particular context. The following section sets out a framework to understand the various corruption risks that employment services may be exposed to.

Value chain analysis

A value chain “describes the full range of activities that are required to bring a product or service from conception, through the intermediary phases of production and delivery to final consumers, and final disposal after use” (Kaplinsky and Morris 2001).

One method of assessing corruption risks in employment services is to consider the level of the value chain at which they might occur: contextual, organisational, individual or procedural (adapted from Selinšek 2015 and Jenkins and Chêne 2018).

A few factors that may encourage corruption risks in employment services at the various levels are highlighted in the following table (adapted from Selinšek 2015 and Jenkins and Chêne 2018).

Factors encouraging corruption at different levels

|

Level |

Specific risk factors |

|

Contextual factors Factors outside the control of the employment services agency |

|

|

Organisational factors Factors within the control of the organisation or sector that are the result of their actions or inactions, such as the rules and policies for good governance, management, decision making, operational guidance and other internal regulations |

|

|

Individual factors Factors that could motivate individuals to engage in corrupt or unethical behaviour |

|

|

Working process factors Factors that arise from working procedures in an organisation |

|

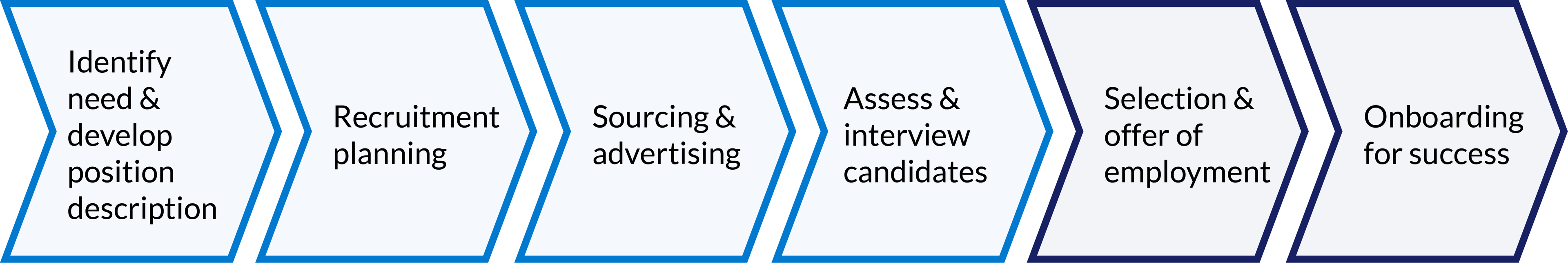

As depicted in Figure 1, typical stages in the value chain of providing employment services include needs identication and policymaking, resource planning, sourcing of suitable candidates, matching unemployed candidates with potential employers and recruitment finalisation process (Ahmed 2011; Iowa State University 2021). Also, capacity for integrity can be incorporated into every stage of thevalue chain process. For example, hiring processes can promote integrity as an organisational value from the beginning with the job, description, advertisement, selection and on-boarding processes (OECD 2020). In some OECD countries, background checks and pre-screening for integrity are two of the first activities used to weed out people who present high risk (OECD 2020). For an overview of capacities to preventing corruption risks during hiring processes, one can refer to recent OECD Public Integrity Handbook (2020).

Figure 1: Typical stages of providing employment services (Iowa State University 2021)

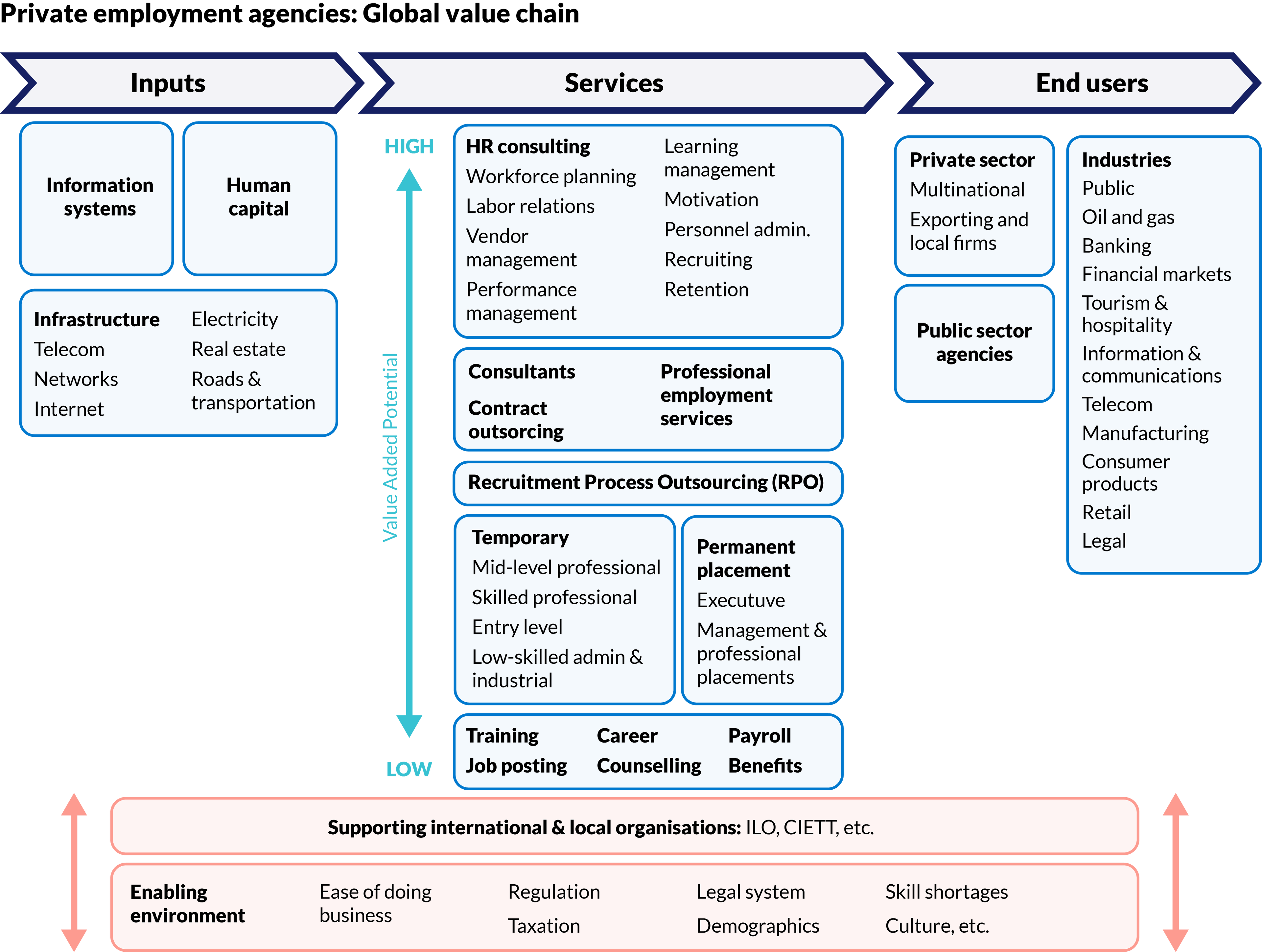

Employment service value chains can have further layers of complexity added to them depending on the type of employment agency (generally public or private) and environment in which it operates. For example, as shown in Figure 2, Ahmed (2011) notes that the industry’s primary inputs are human capital, information technology and local infrastructure; and the end users are employers in the public and private sectors. Ahmed further stresses that the enabling environment and supporting institutions have a significant impact on each stage in the chain, type and level of service, as well as the degree of market penetration.

Figure 2: Global value chains of private employment agencies (Ahmed 2011)

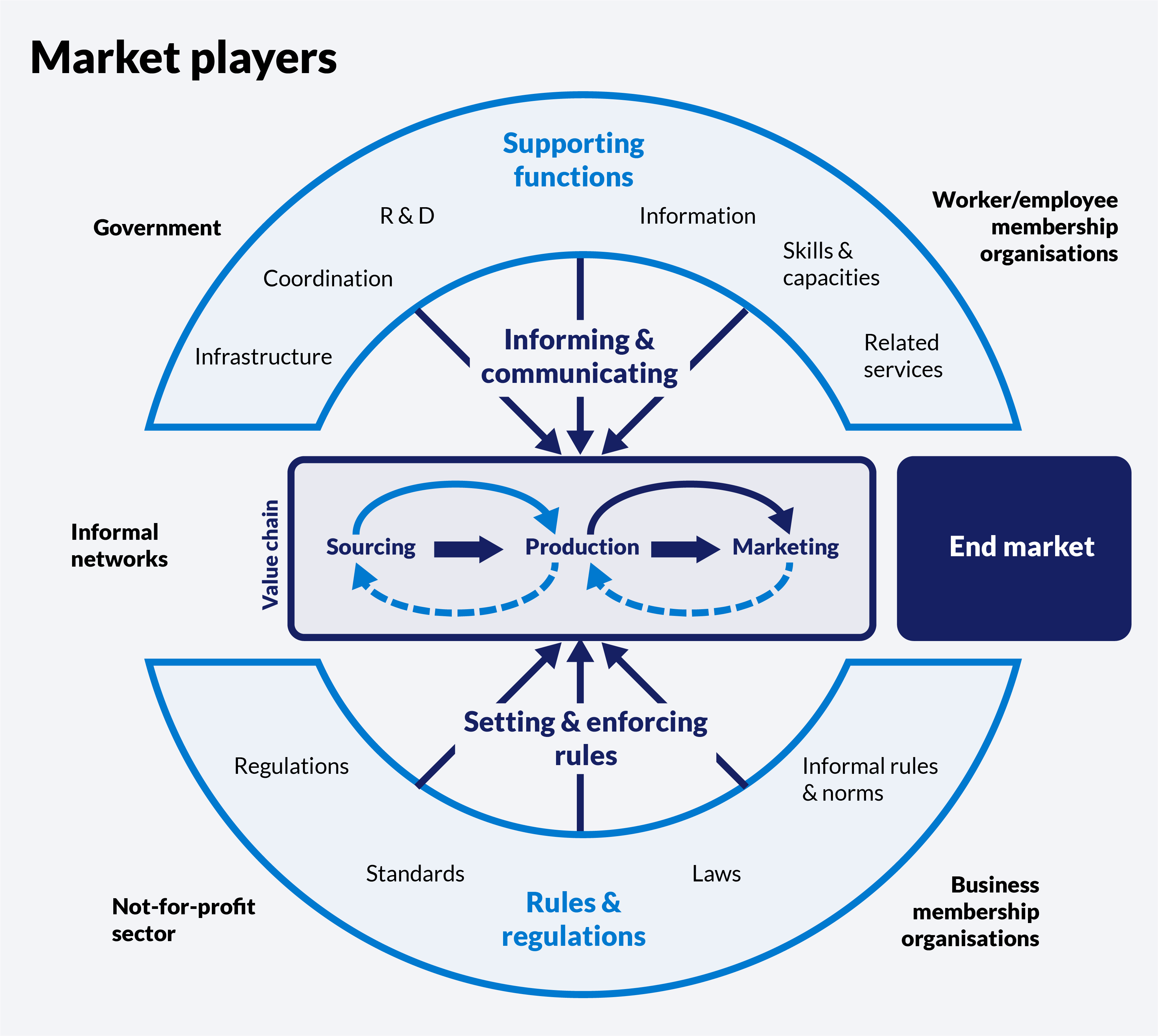

Value chains for employment services are often developed with a developmental purpose in mind as a means of addressing productivity, growth and job creation. As illustrated in Figure 3, value chains are complex systems in which multiple market actors have a role to play (Hakemulder and Value Chain Development Team 2016). For example, a talent sourcing process for an employment agency (public or private) can involve the use of information systems in the form of labour directories for identification of workers, recruitment services including interview processes, and finally supply/matching of required labour to employers. All of this would also depend on environmental factors such as the average skill levels of the work force, contextual culture and so on.

Figure 3: Employment services value chain describing actors and processes (Hakemulder and Value Chain Development Team 2016)

The purpose of decoding the various levels of operations in providing employment services is that certain integrity and corruption risks can be more likely at particular stages of the value chain. See the illustrative table that follows (adapted from Jenkins and Chêne 2018; Hakemulder and Value Chain Development Team 2016 and conversation with practitioners). For example, at the policy setting stage there may be undue influence exerted by trade union or a business organisation that can have an impact on the way a certain labour market policy is constructed and implemented.

|

Main actors at each stage |

Potential corruption risks |

|

|

Policy setting |

Politicians, ministers, trade unions, companies |

Undue influence |

|

Identifying target groups |

Government ministries, employment agencies |

Undue influence |

|

Recruitment planning |

Decision makers within employment agencies (i.e., directors/managers) |

Undue influence; nepotism

|

|

Operational sourcing (including infrastructure and human resources) |

Employment agency officials; Service providers (e.g.: IT solutions); Subcontractors |

Bribery; kickbacks; collusion; nepotism; procurement fraud, i.e., false invoicing |

|

Sourcing potential employers |

Companies/organisations requiring labour i.e., employers; employment agency |

Bribery; collusion |

|

Candidate assessment and selection |

Job seekers; employment agency officials |

Bribery |

|

Skills training / development |

Job seekers; employment agency officials; skills training centres |

Ghost beneficiaries |

|

Offer of employment |

Job seekers; employment agency officials; employers |

Bribery |

|

Onboarding |

Employers; employees; employment agency officials |

Bribery |

Sector specific corruption risks

Undue influence

Developing active labour market policies involves setting priorities: which industries or regions are deemed strategic; which type of firm merits support; which target groups to prioritise for training opportunities; who should receive subsidies, and so on. Given the resources up for grabs, there is a risk that certain interest groups may seek to illicitly influence these political decisions for their own benefit. For example, in the past, corporations operating in China have claimed success in pressuring the Chinese government to weaken or abandon significant pro-worker reforms it had proposed (Global Labor Strategies 2007).

Labour market regulations and policies play an important role in protecting workers and as such should be the product of multi-stakeholder dialogue (ILO 2020b). Yet stark power asymmetries between workers and their employers can enhance the risk that employers exercise undue influence over labour market policy and leave employees with little voice in the design of labour market policies (OECD 2019).

Improper relationships between company executives and political leaders, particularly where political donations are involved, can also undermine the enforcement of existing regulations when firms use their economic clout to distort the labour market. The OECD (2019) notes that certain employers “deliberately misclassify workers in an attempt to avoid employment regulation, tax obligations and workers’ representation, as well as to shift risks onto workers and gain a competitive advantage”.

According to the OECD (2019), labour protections are increasingly being outflanked by new forms of work that pose a challenge to regulations largely designed for full-time, permanent employees working for a single employer. Chen (2020) notes that in the context of the gig economy, workers are routinely deprived of labour protections, such as minimum wage, overtime pay, workers’ compensation, unemployment and state disability insurance, as employers often insist on illegally misclassifying them as “independent contractors”.

Nepotism

Unfair practices related to the use of personal connections are commonplace in labour markets, especially in contexts where the government faces challenges in keeping unemployment rates under control (SIA 2013). Reports from Tanzania suggest that fresh graduates are the worst affected as they lack the experience and “connections” that have become the two major factors for finding work in the country (SIA 2013). Tanzanian legal experts argue that, while nepotism is against the law, cases involving unfair recruitment practices rarely gain much attention unless it also involves other issues such as abuse of office in the public sector (SIA 2013).

Reports of favouritism and conflicts of interest have also been reported in industrialised economies. For example, in Australia, the Victorian ombudsman reported on key concerns in public sector employment arising from more than 60 investigations, including (IBAC 2020):

- inadequate pre-employment screening

- appointments compromised by nepotism, favouritism and conflicts of interest

- recycling of officers with histories of questionable conduct or performance

Bribery

Corruption in hiring processes, especially in the public sector, has been widely documented (Weaver 2021). An interview of 60 Indonesian civil servants from 2006 found that all of them had paid a bribe to be hired (Kristiansen and Ramli 2006). Moreover, former Russian Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev has publicly acknowledged that most government jobs in Russia can be purchased (NewsRu 2008; Yasmann 2008).

In addition to securing a job, conversations with practitioners indicated that bribery is also widespread when it comes to other activities related to employment services such as obtaining access to skills and vocational training.

Fraud

Practitioners interviewed for this Helpdesk Answer also mentioned incidents of fraud related to the procurement of basic equipment in job centres, this could equally apply to the acquisition of software packages to receive and process jobseekers’ applications. So-called ghost beneficiaries may pose another challenge: fraudulent claims of the number of recipients of jobseekers’ allowance, benefits or training, whereby unscrupulous individuals inflate the number of supposed beneficiaries and pocket the difference.

Potential mitigation measures

Clearly defined labour protections and appropriate regulatory standards

While labour protections and standards are not themselves anti-corruption instruments, well formulated labour market regulations can serve to reduce the opacity and uncertainty that provide entry points for corruption. As the OECD (2019) notes “clearly defining the employment status of workers… acts as a gateway to various worker rights and protections – including employment and social protection, but also access to training and collective bargaining”.

Clear stipulations on employment status could potentially help to reduce the grey zone that provides employers and those working in employment services great discretion over workers’ fates as well as opportunities to extract bribes from jobseekers who want to escape precarity.

Work by Khan, Andreoni and Roy (2016: 20-21) argues that to encourage compliance with labour standards, regulatory requirements ought to be feasible and realistic in a given market. In some low-income countries, organisations may lack the capability to comply with regulations. Khan et al. (2016) point out that in such scenarios, firms engage in corrupt practices as an economic survival mechanism by paying off labour inspectors to look the other way or bribing employment services providers to illicit supply workers.

Poorly designed labour market regulations can perversely serve as a breeding ground for corruption and rent-seeking behaviour because, due to the unsurmountable gap between legal requirements and the economic reality, unscrupulous officials may strike illicit bargains with firms that are unable to comply with the rules.

LMPs informed by robust analysis

As emphasised above with reference to Khan et al (2016), enforcing strict rules on firms in the informal sector may have the unintended consequence of unemployment for workers and other hardships. This underscores the need for thorough political economy analysis to understand the inner workings of a given labour market when formulating LMP interventions (Ahmed 2011; Nunn 2013; OECD 2019). Such analysis could also help reveal potential vulnerabilities to corruption. This kind of analysis is arguably even more important in development assistance interventions, given that donors are typically less familiar with labour markets in partner countries than in their home country.

There are a number of examples from European employment agencies that use detailed econometric analysis to model the employment prospects of certain social groups and target their programming accordingly. In Belgium, the public employment service of the Flanders region (VDAB) uses a variety of qualitative and quantitative data to inform its target setting process, while in Sweden information provided by the analysis department influences the target levels set by employment services (Nunn 2013). In low-income countries, such data may not exist or be of poor quality, but the principle of tailoring interventions to the local setting to work with the grain is nonetheless pivotal.

Monitoring and benchmarking

Continuous monitoring of operations and results measurement can help improve outcomes in the labour market by improving the quality and availability of monitoring data to assist employment agencies’ planning and adaptation to more efficient models (Nunn 2013). In addition, tracking budgets and other expenses over time facilitates audits processes that can help uncover financial irregularities.

Nunn (2013) also reports that knowledge exchange between employment services agencies in different European countries has helped inform integrity management approaches and enhance compliance with standards. For example, sharing learnings from challenges faced by an agency could benefit another employment agency facing comparable issues. Similarly, employing a standardised format for monitoring, evaluation and learning would contribute to creating a commonly accepted benchmark/standard for performance and integrity management.

Performance management to increase public accountability of employment agencies

Several public employment services in Europe have adopted performance management tools to improve their public and political accountability (Nunn 2013; Hakemulder and Value Chain Development Team 2016).

A few examples of performance management practices include (Nunn 2013):

- Belgium’s VDAB considers a wide variety of data including labour market analysis and research and survey data to study both long- and short-term impacts of its programming.

- In Germany, a system is used to compare the performance of similar regions in clusters that are regarded as facing comparable labour market situations. Performance variation between and within regions is then used to identify good practices for sharing between regions and localities.

- Spain has benchmarked the active labour market policy performance of its 17 autonomous regions by means of a system with 22 indicators. Their outcomes determine the distribution of funds to employment services in the regions.

Focus on social dialogues to promote inclusive governance

According to Grimshaw, Koukiadaki and Tavora (2017), social dialogue plays an increasingly significant role in supporting the transition to democratic, more equitable and sustainable political and economic systems in low- and middle-income countries.

Grimshaw, Koukiadaki, and Tavora (2017) point to several features of social dialogues that can help build trust, improve information flows, reduce opacity and thereby indirectly reduce opportunities for undue influence and corruption. For example, social dialogues have the capacity to increase transparency on certain issues and they can help increase accountability, decrease the perception of corruption and thereby support reducing incentives for corruption.

First, effective social dialogue establishes formal (and often informal) processes that lessen the capital-labour power imbalance in the labour market and enable parties to build consensus that resolve disagreements through accepted dispute resolution mechanisms. For example, it can help ensure all parties have their voice heard in policy debates and labour reforms. In Singapore, social dialogue has been used as a way to address issues affecting the increasing number of contract and casual workers, largely related to the expansion in outsourcing services (Ebisui 2012).

Second, its flexibility can facilitate novel modes of exchange and collaboration between different stakeholders in the labour market, including diverse government agencies, civil society organisations, regional and local government bodies, and training bodies. In South Africa, for example, social dialogue regarding labour market policy, as well as social and economic policy in general, takes place at the National Economic Development and Labour Council, which comprises the typical tripartite partners as well as a community constituency representing civil society (Ebisui 2012).

Complaints channels, grievance mechanisms and whistleblower reporting

Safe grievance and reporting channels can enable those who suspect they were denied employment or training opportunities due to corrupt practices to report this. This has a twofold advantage. First, it allows for alleged wrongdoing to be investigated and if necessary correct; and second, it allows for patterns of corruption such as hotspots in specific job centres to be more readily identified. It is important that there are clear lines of responsibility to investigate and sanction any wrongdoing by employment agencies, whether public or private.

In Serbia, for example, the Law on the Protection of Whistle-blowers Act, No. 128/2014, defines a whistleblower in Article 2(2) as “any natural person who performs whistle-blowing in connection with his employment; hiring procedure; use of services rendered by public and other authorities, holders of public authority or public services; business dealings; and ownership in a business entity”. The act goes a step further to define “employment” broadly in Articles 2(5) and 21 to include volunteers, work performed outside employment, internship, or any other factual work for an employer (Chalouat, Carrión-Crespo and Licata 2019).

Human resources (HR) and management practices to support a culture of anti-corruption

Due diligence and integrity screening when hiring employees to work in an employment service is an important means of countering nepotism and bribery (CGMA and IBE 2019). Moreover, maintaining functional independence of employment service providers is seen by practitioners as imperative to enforcing a culture of integrity. For example, recruitment of staff to work at employment centres should be strictly based on merit rather than connections, otherwise this could trigger a vicious cycle in which employment agencies simply assign the most lucrative postings to friends and family.

As a final reflection, it may also be good practice to separate the public employment service from the labour inspectorate, not least given widespread reports of corruption in labour inspectorates around the world (ILO 2005; The European Trade Union Institute 2016). A practitioner interviewed for this paper noted that where the team responsible for labour market policy (typically in the Ministry of Labour) sits close to the labour inspectorate, employers tend to be anxious about engaging in social dialogues as they fear they will become targets of labour inspection.

- [1] ALMPs describe measures to help individuals enter the labour market or to prevent already employed individuals from losing their jobs. ALMPs include various measures, from training to job search assistance, subsidies, supported employment opportunities and programmes to support entrepreneurial activities.

- The public employment service and the ministries of labour are the principal authorities responsible for ALMPs in most countries (European Centre for Social Welfare Policy and Research 2020).