Query

Based on relatively recent research on Bangladesh, could you please review evidence on: a) the forms (sector, type and geographical) of corruption that have been most damaging to the country in terms of the impact on the poor; and b) the approaches that appear to have been successful/unsuccessful in addressing corruption in Bangladesh.

Background

The People’s Republic of Bangladesh was founded as a constitutional, secular, democratic, multiparty, parliamentary republic. After independence in 1971, Bangladesh went through periods of poverty and famine, as well as political turmoil and military coups. The restoration of democracy in 1991 was followed by considerable advances in economic, political and social development. However, the current milieu in the densely populated country continues to remain volatile as it undergoes substantial economic and social change (UNDP 2018).

The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the main opposition to the incumbent Awami League (AL), resorted to violence across the country after boycotting the elections in 2014, leading to arrests and harassment of key party officials by the security forces (Freedom House 2017a). However, the ruling AL government has consolidated political power through sustained harassment of the opposition and those perceived to be allied with it, as well as of critical voices in the media and civil society. Such acts have greatly affected the opposing BNP as well as the Islamist Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) party (Freedom House 2018a).

Islamist extremism has been on the rise in the otherwise usually tolerant country (BBC News 2018). There has been a rise in radicalism and extremism with systematic attacks aimed at silencing secular bloggers, many of whom have been murdered (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

Though the government denies the domestic presence of Islamic State (IS), all the attacks between 2015 and 2016 were claimed by IS and al-Qaeda in South Asia (AQIS) (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018). IS even took responsibility for the Gulshan café attack in 2016, where 20 hostages and two police officers were killed in the Dhaka bakery that was known to be popular with foreigners (Freedom House 2017a; Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

These attacks led to a crackdown on radical groups, with around 15,000 people arrested to curb a spate of extremist violence (Freedom House 2017a). Observers said the initiative involved widespread human rights abuses by authorities, including arbitrary arrests, enforced disappearances and custodial deaths, which currently continue in the country (Freedom House 2017a; Freedom House 2018).

Bangladesh has basic well-defined administrative infrastructure throughout the country, although it is deficient in some respects (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018). The geographically low-lying country is vulnerable to flooding and cyclones, and is likely to be badly affected by any rises in sea levels (BBC News 2018). It is, therefore, imperative to counter corruption in areas such as disaster prevention and management.

It should be noted that the influx of over 655,000 Rohingya refugees fleeing attacks by the Burmese military has exacerbated specific governance issues such as human trafficking and forced prostitution, and has led to price rises in basic products and a fall in daily wages (Khatun 2017; Human Rights Watch 2018). Government apparatuses also have to deal with corrupt third parties who use the crisis to issue fake Bangladeshi identification to the refugees in exchange for bribes (Khatun 2017).

However, Bangladesh has made remarkable progress in reducing poverty, supported by sustained economic growth. Based on the international poverty line of US$1.90 per person per day, poverty in the country fell from 44.2% in 1991 to 14.8% in 2016/17. Rapid growth enabled Bangladesh to reach the lower middle-income country status in 2015. In 2018, the country fulfilled all three eligibility criteria for graduation from the UN’s Least Developed Countries (LDC) list for the first time. Life expectancy, literacy rates and per capita food production have increased significantly (World Bank 2018b).

Bangladesh has made incredible progress in terms of income growth and other aspects of human development. Per capita income in the country, for example, has risen from US$520 in 1990 to US$4,040 in 2017; GDP growth has remained above 5% per year for the past 10 years. Life expectancy has increased from 65 years in 2001 to 72.5 years in 2016; adult literacy levels are at an all-time high of 72.76%, according to UNESCO statistics. This marks an increase of 26.1 percentage points from 2007.

Despite these successes, the country still faces some daunting challenges with about 22 million people still living below the poverty line, and corruption being widespread in a number of sectors (World Bank 2018; Bertlesmann Stiftung 2018).

Drug trafficking, corruption, fraud, counterfeit money, gold smuggling and trafficking in persons are the principal sources of illicit proceeds. Bangladesh is also vulnerable to terrorism financing, including funding that flows through the hawala/hundie79a1bcf10c3 system and by cash courier. The Bangladesh-based terrorist organisation, Jamaat ul-Mujahideen Bangladesh, has publicly claimed to receive funding from Saudi Arabia (US Department of State 2016).

Eradicating the “culture of corruption9334da46966b” in Bangladesh requires much more than what is currently being done (Anup 2013). In fact, some observers suggest that the country could have achieved at least 2%–3% higher annual GDP growth if corruption could be moderately controlled (Jamal 2017).

Overview of corruption in Bangladesh

Extent of corruption

Bangladesh ranks 143 out of 180 countries in Transparency International’s 2017 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) with a score of 28/100 (Transparency International 2018) with 0 denoting the highest perception of corruption and 100 the lowest. Bangladesh also scores poorly in a number of governance-related issues, including corruption, according to the Worldwide Governance Indicators (WGI) by the World Bank (2017). The scores in the table below denote the percentile ranks520d2c87b0d5 for Bangladesh:

|

Indicator |

2016 percentile rank |

2017 percentile rank |

|

Control of corruption |

18.8 |

19.2 |

|

Government effectiveness |

25.5 |

22.1 |

|

Political stability and absence of violence/terrorism |

11.0 |

10.5 |

|

Regulatory quality |

22.1 |

20.7 |

|

Rule of law |

28.4 |

28.4 |

|

Voice and accountability |

30.5 |

30.0 |

The 2017 TRACE Bribery Risk Matrix places Bangladesh in the high-risk category, ranking it 185 out of 200 surveyed countries. This high risk of bribery is confirmed by the National Household Survey 2017 conducted by Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB), which shows that 66.5% of the surveyed households have been victims of corruption in one or other selected sector of service delivery (including electricity, health and education) or when coming in contact with law enforcement (TIB 2018).

Hashmi (2017) notes that the lack of transparent and accountable governance, as well as the prevalence of impunity for well-connected people shroud the true extent of corruption in Bangladesh.

Main drivers of corruption

It has long been argued that there is a strong connection between governance, ethics, integrity, and corruption, all of which are the product of a complex interplay of political, economic, social, and even psychological factors and forces (Westra 2000). In the case of Bangladesh, Rashid and Johara (2018) argue that there exists an integrity-governance-corruption nexus in the country, as a result of which all the organs of government have become pervaded by corruption.

Iftekharuzzaman (2014) contends that a key driver of this behaviour are the close ties and networks between politics and business in the country. The ratio of MPs with business as the primary occupation has reached nearly 60% from about 18% at the time of Bangladeshi independence. Ministers have adamantly insisted that there is nothing wrong in amassing wealth from positions of power, which according to Iftekharuzzaman (2014) reflects widespread denial that corrupt schemes established for personal benefits are damaging to society more broadly. Indeed, the lack of political will to fight corruption has been a constant obstacle to democratic and accountable governance in Bangladesh (Aminuzzaman and Khair 2014).

A 2014 study identified a number of other enabling factors for corruption, including weak oversight functions, insufficient resources, a dearth of technical and professional competence in key positions, politicisation of institutions, nepotism and an absence of exemplary punishment for corruption that has led to a culture of impunity/denial. This is exacerbated by low awareness of citizens of their rights and inadequate access to information (Aminuzzaman and Khair 2014).

Some argue that an apparent declining commitment to democratic norms might also effect levels of corruption in the country. In 2017, Bangladesh’s score in the Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index fell to its lowest ever. Its overall score of 5.43 out of 10 placed the country 92nd out of 165 countries assessed. While the country's points in all other categories remained essentially unchanged, the score in civil liberties dropped from 6.76 in 2006 to 5.29 in 2017, reflecting concerns among rights activists, and leading to the categorisation of Bangladesh as a "hybrid regime".

In an assessment of why the country’s score fell, Anik (2018) observed that where democracy is weaker, corruption tends to be more widespread, governments are more likely to repress opposition parties, and the impartial functioning of public administration is jeopardised (Anik 2018).

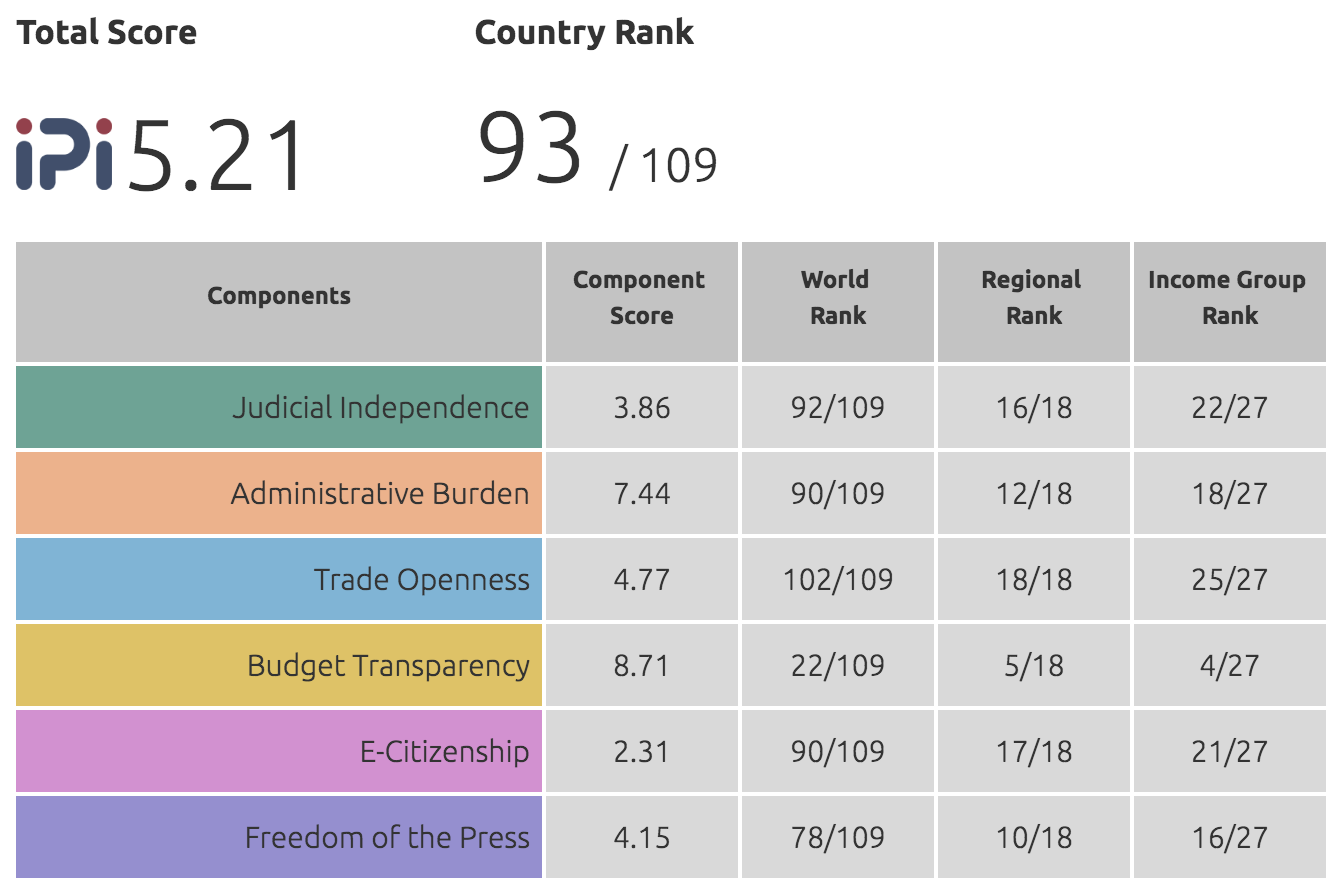

Such a volatile scenario creates a breeding ground for politics to be “monopolised” and the concomitant flourishment of various drivers of corruption, including complex bureaucratic environments, weak rule of law, the absence of effective checks and balances, as well as a low level of judicial independence (IPI 2017; Anik 2018). Tellingly, Freedom House (2018) accords the status of “Partly Free” to Bangladesh with a score of 45/100, stating that under the AL government, anti-corruption efforts have been weakened by politicised enforcement and subversion of the judicial process.

Source: Index of Public integrity IPI 2017.

Forms of corruption

Political and grand corruption

Corruption is so pervasive at both micro and macro levels that it threatens to become a way of life (Jamal 2017). Elites in Bangladesh may well have manipulated the political process to suit their own ends, just as they have developed elaborate corrupt practices both to look after their friends and to preserve their own positions in power (Hough 2013). This gives rise to the phenomenon of what Mungiu-Pippidi (2006) calls “particularism”, a mode of social organisation characterised by the regular distribution of public goods on a non-universalistic basis that mirrors the vicious distribution of power within such societies. Few anti-corruption campaigns dare to attack the roots of corruption in societies where particularism is the norm, as these roots lie in the distribution of power itself (Mungiu-Pippidi 2006).

Corruption is to be found at all levels in almost all areas of government and some private organisations (Anup 2013). Grand corruption is so prevalent that it affects the capacity of the state to act and makes it difficult to reform (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

Party financing is one of the greyest areas where unaccounted money is deposited. There is no audit or regulatory mechanism in place to scrutinise sources of party funding (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018). While some limits on contributions exist, and parties and candidates are both subject to restrictions on spending during campaigns, evidence suggests that limits on both spending and donations are breached regularly. The law specifies some reporting requirements for parties and candidates but, in practice, those requirements are rarely adhered to (MPT 2014). Moreover, access to relevant information pertaining to governance is virtually absent (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

According to the Open Budget Survey 2017 by International Budget Partnership (IBP), Bangladesh scores 41/100 on the Open Budget Index. IBP notes that Bangladesh provides the public with limited budget information, as countries that score above 60 on the Open Budget Index are considered to be providing sufficient budget information to enable the public to engage in budget discussions in an informed manner.

Some of the most extreme anti-corruption measures in the country came about in 2007–2008, when the military-backed caretaker government headed by Fakhruddin Ahmed launched an anti-corruption crusade. This campaign led to the arrest of many of Bangladesh’s most well-known and influential politicians. The arrests went right to the top, including both party leaders Khaleda Zia (AL) and Sheikh Hasina(BNP), whose rivalry long dominated the country’s politics with each having been prime minister at various times since 1991 (BBC News 2018). The arrests also included former cabinet members, leading business people and tens of thousands of others on charges that ranged from buying undue influence to bribery, tax evasion, embezzlement and fraud (Hough 2013). The eventual release of all the accused and imprisoned during this period shows the extent of impunity operating in the country (Hough 2013).

Currently, Khaleda Zia remains imprisoned for embezzling US$250,000 meant for an orphanage, and a recent court ruling increased her sentence from five to ten years (NDTV 2018). Zia happens to be the arch rival of the incumbent prime minister.

The biggest impediment against effective corruption control in Bangladesh, as is the case in most other countries where corruption is pervasive, is that political commitment remains far from truly enforced without fear or favour, which allows corruption to be often condoned and protected (Jamal 2017). Thus, due to the high levels of corruption at the top, and the consequent poor enforcement of legislation and often biased to favour those with political connections, there is a requirement for graft to be weeded out not just by top-down but also bottom-up approaches, including the media and civil society.

Petty and bureaucratic corruption

Although salaries in the public sector have increased over the past few years, bribery remains widespread and constitutes an important source of income of public officials in Bangladesh (Palash 2018). According to TI Bangladesh, the hike in salaries has not helped to deter bribery because the incentive structure that allows public officials to extract bribes still remains: public office holders are rarely subjected to judicial or parliamentary scrutiny. Corruption in public office is very high. The rent-seeking elements in the bureaucracy always try to please their political boss, favouring the status quo (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018). Additionally, promotions and appointments in the public sector are often based on political considerations (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

Businesses especially encounter corruption when accessing public services. Nearly half of businesses expect to give facilitation payments to public officials “to get things done”. Nepotism, fraud, bribery and irregular payments in the process of awarding government contracts are perceived as extremely common. Tax evasion also remains common, as well as collusion and a discretionary space for granting benefits to targeted groups of taxpayers in both tax policy and administration (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018).

There is a high risk of corruption in the Bangladeshi land administration. Companies express insufficient confidence in the government’s ability to protect property rights. Bangladesh’s most prominent construction scandal is the collapse of an eight-storey garment factory in April 2013, which killed over 1,100 people. The factory suffered from a faulty construction that violated building codes. The incident highlights the larger issue of a lack of good governance, corruption, limited resources, bribes involved in licensing and permits, or collusion between factory owners and safety inspectors, which allows facilities to remain operational even when dangers are identified, much to the detriment of workers’ health and safety (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018; Bhattacharya et al 2018).

Some field level studies have found that to obtain a work order of any infrastructure project around 10%–20% of the project cost is to be paid as bribes to ruling party leader, 15%–20% to mayor, engineers and civil managers, and 2%–3% percent to other officials (Bhattacharya et al. 2018).

Sectors affected by corruption

Service delivery

Analysts observe that bribery, rent-seeking and inappropriate use of government funds, excessive lobbying, long delays in service performance, pilfering, irresponsible conduct from government officials, and excessive bureaucratic intemperance and mind-set have made public sector departments associated with law enforcement, water supply, electricity, gas supply, education, waste disposal, health, transportation, issue of passports and maintenance of land records susceptible to corruption. Lack of proper accountability appears to have also been a cause for this susceptibility to corruption (Zamir 2018).

The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Index 2017–2018 ranks Bangladesh 99/137, and it provides ranks on the following parameters:

- diversion of public funds – 75/137

- favouritism in decisions of government officials – 106/137

- strength of auditing and reporting standards – 120/137

Politicisation of recruitment in universities and schools affects the standard of education in Bangladesh. Those who fall from political grace are appointed as officers in special duty (OSD) and are not given any responsibility. For example, in January 2016, five senior bureaucrats holding the rank of additional secretary were made OSDs at the public administration ministry (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018). In fact, nepotism and political affiliations are common factors influencing the recruitment and training of teachers in Bangladesh (Mulcahy 2015). Although, primary education in Bangladesh is ostensibly free (for children aged 5–13), a household survey from 2009 found that, 66% of households reportedly had to make unauthorised payments to secure admission of their child into class one (ages 5–7) (Mulcahy 2015).

The healthcare sector is also rife with cases of grand and petty corruption. Healthcare seekers are known to pay bribes to obtain better services, access to ambulances and sometimes to avail the services. Private healthcare institutions employ unregistered doctors and doctors with fake qualifications or often fail to employ the legally required minimum number of doctors and support staff. Political influence and collusion in the selection of contractors for food supplies and purchase of unnecessary medical equipment, as well as selective training often depriving the most deserving candidates of training opportunities remain harsh realities (McDevitt 2015).

Judiciary

Although on paper the judiciary is independent and has been separated from the executive since 2007, the executive still maintains control over judicial appointments, and the judiciary remains closely aligned with the executive branch (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018).

Apart from being known as corrupt, the judicial process in Bangladesh is sluggish with appeals are subject to lengthy delays (US Department of State 2017; Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018). Delays in the recruitment of judges have left several hundred positions in lower courts vacant, leading to a substantial case backlog (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018).

Anti-corruption efforts have been weakened by politicised enforcement and subversion of the judicial process under the incumbent AL government (Freedom House 2018). The judiciary does not always protect the constitutional right to a fair and public trial due to corruption, partisanship, and weak human resources and institutional capacities (US Department of State 2017).

Companies face a high risk of corruption in the Bangladeshi judicial system. Corruption is perceived to be widespread in lower courts. Magistrates, attorneys and other court officials frequently demand bribes from defendants or rule based on loyalty to patronage networks. Enforcing a lawful contract is a big challenge for businesses as it is uncertain, takes an average of 1,442 days and is extremely costly (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018).

Security forces

The police force is the most corrupt institution, followed by the civil service, political parties and the judiciary in Bangladesh (The Daily Star 2010). There is a high risk of corruption when interacting with Bangladeshi police. Businesses ranked the Bangladeshi police as one of the least reliable in the world and noted business costs due to crime and violence (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018). Law enforcement agencies were likewise found to be the public bodies with whom citizens are most likely to experience corruption according to the National Household Survey 2017 conducted by Transparency International Bangladesh (TI-B) (TI-B 2018)

Police harassment in exchange for bribes is common. Public distrust of police and security services deters many from approaching government forces for assistance or to report criminal incidents. Security forces reportedly used threats, beatings, kneecappings and electric shocks, and some officers committed rape and other sexual abuses – all with impunity (US Department of State 2017).

A 2015 survey to assess the Trust Index on different institutions in Bangladesh by the Power and Participation Research Centre (PPRC) found that trust in the police was low in Dhaka (14.2 percent) and rural areas (13.2 percent), and moderate in other urban areas (20.0 percent) (Rashid and Johara 2018).

The Bangladesh military has directly ruled the country for 15 of its 46 years of existence. Bangladesh’s armed forces also have a dual role as internal security forces and are repeatedly called on to prevent civil unrest. Such is its power that even Bangladesh’s democratically elected civilian leaders have been forced to tread carefully around the military (Smith 2018). The armed forces have also been known to carry out human rights abuses with impunity, including extrajudicial killings, torture, arbitrary or unlawful detentions, and forced disappearances (Freedom House 2017a; US Department of State 2017).

The armed forces account for 6% of Bangladesh’s annual budget, totalling US$3.2 billion in the year 2017–2018, according to official statistics. Weak monitoring, controls and audits facilitate corruption and waste in their budgeting. The parliament, the auditor general of Bangladesh, and the anti-corruption watchdog are often reluctant to investigate the military – and are even actively prevented from doing so. Even in the absence of dishonesty, failure to implement the due process often leads to purchases of high-cost items of questionable strategic purpose, severe delays and cost overruns. Bangladesh systematically excludes significant items from its expense reporting for its military expenditure, and the military’s off-budget spending is often contributed to its business activities, rather than national defence (Smith 2018).

It has been revealed that the Bangladeshi military has stakes in food, textile, jute, garment, electronics, real estate, automobile, shipbuilding, manufacturing and travel businesses. The military also operates Trust Bank and the Ansar VDP Bank and has a record of giving illicit loans from these institutions to top officers. According to a BBC investigation, the Bangladesh Army’s business interests further include power plants, roads, infrastructure and bridge projects, amounting to billions of dollars of private assets. In fact, military-owned businesses are virtually indistinguishable from other commercial enterprises in the way they operate (Smith 2018).

Impact on the poor

Corruption in Bangladesh hinders proper allocation of resources, weakens public services, reduces productivity, worsens poverty, marginalises the poor and creates social unrest (Anup 2013).

The Bangladeshi poor78422d564d19 are deprived of equal access to education and white-collar jobs. Irregularities in appointments were visible and, in many cases, those with political affiliation or willing to pay bribes were employed over meritorious candidates. Extreme poverty often forced people to accept unsafe, poor working conditions, often for long hours. The government introduced a gender sensitive budget in 40 ministries; however, women remain socially marginal and victims of violence. They face discrimination in the workplace and have lower wages (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

Corruption has an in-built bias against the poor, disadvantaged and low-income sections of society. They are directly affected by the increased cost of public services for bribery and have limited or even lack access to services because of they cannot pay a bribe (Jamal 2017).

TIB’s 2012 National Household Survey showed that, while corruption affects everyone, poorer sections of the society suffer more. Cost of petty corruption was estimated to be 4.8% of average annual household expenditure. More importantly, for households with the lowest range of expenditures, the rate of loss is much higher at 5.5%, compared to higher spending households where it is 1.3%. Thus, the burden of corruption is greater for the poor (Iftekharuzzaman 2014).

Changing this culture of corruption remains difficult as there has been a tendency for citizens to not just tolerate corruption but to respect those who are seen as clever and savvy enough to use their office to look after themselves, their friends and their families. The fact that money is often made through dubious means can frequently be overlooked; public servants who play the game and manipulate rules to suit themselves are seen as being worthy of emulation and admiration. In short, corruption is widely perceived to grease the wheels and to help ensure that preferred outcomes come quickly, efficiently and effectively (Hough 2013; Hashmi 2017).

How successful have anti-corruption efforts been?

Numerous studies have concluded that despite the existence of reasonably sound legal framework, the implementation and enforcement of legislation is largely inadequate, and a culture of non-compliance generally prevails (Aminuzzaman and Khair 2014; Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018; Freedom House 2018).

Hough (2013) observes that Bangladeshi governments of all colours have claimed that they want to tackle corruption. This has led to a series of high profile, top-down campaigns involving new legislation, the introduction of new institutions and ultimately, the high profile arrests of certain politicians. Despite initial enthusiasm among much of the Bangladeshi population, the success of these attempts has, however, been minimal.For instance, while the passing of the Right to Information (RTI) Bill and the subsequent establishment of the Information Commission was hailed as victory by many, as discussed in the following section there are still issues surrounding its proper execution (Freedom House 2017b; Rashid and Johara 2018).

Recent analysis by Khan (2017) notes that, while Bangladesh has some of the worst governance and anti-corruption scores in the world, since 1980, it has made moderate to good progress on different indicators of economic and social development. Thus, it is Khan’s view that anti-corruption and governance initiatives in Bangladesh have to be located in the context of this paradox. Part of the explanation might be found in the fact that anti-corruption strategies in Bangladesh have largely been of the systemic type, primarily focused on the demand side, i.e. interventions intended to improve the quality of public institutions through the promotion of transparency, the investigation of corruption and the imposition of legal penalties through prosecution (Khan 2017). Such measures are reliant on a system of vertical enforcement that remains weak in Bangladesh.

Indeed, while the country already had most of the formal legislation to be compliant with UNCAC when it acceded to the convention in 2007, the problem in Bangladesh is the informal processes and power relationships that prevent the implementation of these laws (Khan 2017).

Moreover, direct investigations into allegations of high-level corruption in the current political climate are unlikely to be effective and may even be counterproductive, as in the Padma Bridge298233bace35 case (Khan 2017). The Anti-Corruption Evidence (ACE) Research Consortium recommends that implementable anti-corruption activities should have a low profile, and be based on an outcome-oriented and incremental set of policy proposals. The emphasis should not be on prosecution and punishment but on finding policy combinations that create incentives for stakeholders in particular sectors or activities to behave in more productive ways.

As such, Khan suggests that alternative anti‑corruption strategies should be designed which seek to exploit the “supply side” by capitalising on the country’s robust civil society and relatively active media sector (ACE 2017). Thus, the importance of social accountability initiatives and civil society contributions to anti-corruption efforts become all the more apparent. Iftekharuzzaman, (TI-B 2017) seems to concur with this assessment, stating that alongside political will, the impartial application of justice and the accountable operation of integrity institutions, efforts to curb corruption will rely on a conducive environment for citizens, journalists and civil society representatives to strengthen the demand for good governance.

In this respect, there are some encouraging developments. The earlier introduction of a Citizens’ Charter (CC) in 2000 has gone into the 2nd Generation starting in 2010, with the objective of providing a platform for civil servants and citizens to discuss the services needed by citizens (Rashid and Johara 2018). In addition, a new performance appraisal system has been launched on a pilot basis to appraise the role and function of public sector employees on the basis of mutually agreed on performance indicators (Rashid and Johara 2018). Finally, to enhance financial accountability, an initiative called the “Strengthening Public Expenditure Management Programme” (SPEMP) has also been undertaken with the aim of building a more strategic and performance-oriented budget management process (Rashid and Johara 2018).

Legal and institutional anti‑corruption framework

International conventions

Bangladesh signed and ratified the United Nation Convention against Corruption in 2007 (UNODC 2018). The country also signed the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organised Crime in 2011 (UNTC 2018).

Domestic legal framework

Bangladesh will celebrate 50 years of independence in 2021. In this context, there are several prospective plans like Vision 2021, the 7th Five Year Plan (7FYP) and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the country has prioritised countering corruption in all these strategic policy processes. For example, in Vision 2021, a political manifesto from the Awami League asserts the aspiration of government to fight against corruption tor sustainable development, and goal 5 (of 8) is to ride society of corruption (Palash 2018).

The Code of Criminal Procedure, the Prevention of Corruption Act, the Penal Code and the Money Laundering Prevention Act criminalise attempted corruption, extortion, active and passive bribery, bribery of foreign public officials, money laundering, and using public resources or confidential state information for private gain (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018; Hosain 2018).

In the last decade a number of other laws have been formulated to tackle particular forms of corruption. These include the Anti-Corruption Public Procurement Rules 2008, The Public Finance and Budget Management Act, 2009, The National Human Rights Commission Act, 2009, The Chartered Secretaries Act, 2010, The Prevention of Money Laundering Act, 2012, and The Competition Act, 2012 (Rashid and Johara 2018).

Facilitation payments can be construed as an unlawful gratification and are thereby illegal. As for gifts and hospitality, there are no specific guidelines or monetary thresholds under Bangladeshi laws and regulations. As a guideline, companies are advised to consider the Government Servants (Conduct) Rules, which stipulates that government servants may accept gifts, provided that the value does not exceed 500 takas (US$6.50). The Anti-Corruption Commission Act provides the legal framework for the independent anti‑corruption commission (ACC) to ensure transparency in the public sector (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018).

The Right to Information Act plays an important role in ensuring transparency and accountability (Paul 2009). The act simplified the fees required to access information, overrode existing secrecy legislation and granted greater independence to the Information Commission, tasked with overseeing and promoting the law (Freedom House 2017b). However, on-going challenges include low response rates to requests for information, and the need to increase awareness of the act’s existence among the public and authorities (Freedom House 2017b).

Despite the enactment Whistleblowers' Protection Act 2011, legal practitioners and officials say they know little about the law, and thus, the act is yet to receive the expected response. As per the law, also known as the Public-Interest Information Disclosure Act (Provide Protection) 2011, no criminal, civil or departmental proceedings can be initiated against a person for disclosing information in the public interest to the authorities, and the whistleblower’s identity will not be disclosed without their consent (Dhaka Tribune 2018).

Bangladesh is no longer on the Financial Action Task Force list of countries that have been identified as having strategic anti-money laundering (AML) deficiencies, and there are no sanctions against the country (KnowYourCountry 2018). However, a report by the US Department of State (2016) found that black market money exchanges remain popular because of the limited convertibility of the local currency, cash-based economy and scrutiny of foreign currency transactions made through official channels. Alternative remittance and value transfer systems also are used to avoid taxes and customs duties. Additional terrorism financing vulnerabilities exist, especially the use of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), charities, counterfeiting and loosely-regulated private banks.

Institutional framework

A National Integrity Strategy (NIS) was approved by Cabinet in October 2012. Subsequently, NIS units have been established at each ministry and a National Integrity Advisory Committee has been formed with the Prime Minister as its Chair. The overall purpose of a National Integrity Strategy is to provide a system of governance that creates trust among citizens. The Government also plans to establish an Ethics Committee composed of the heads of the institutions (Rashid and Johara 2018).

Anti-corruption commission

In Bangladesh, the (ACC) was established in 2004 as a neutral and independent institution under the Anti-Corruption Commission Act of 2004. It addresses anti-corruption in Bangladesh in three broad categories: legal, institutional and other actors (Palash 2018).

The 2018 Freedom House report states that the ACC has become ineffective and subject to overt political interference, and that the government continues to bring or pursue politicised corruption cases against BNP party leaders.

In 2016, the government pushed the Anti-Corruption Commission (Amendment) Bill through parliament, which reauthorised police to pursue cases of fraud, forgery and cheating under eight sections of the penal code (Acharjee 2015; ABnews24 2016).

Former ACC chairman M Badiuzzaman stated that the inclusion of these sections to the ACC’s schedule via an amendment in 2013, hampered the pending investigations of the 5,000 cases on forgery and cheating they were dealing with (Acharjee 2015). Hence, it was deemed necessary to segregate the workload and streamline the focus of the ACC (Acharjee 2015; Bdnews24 2016).

In practice, however, the situation may not have affected the efficiency of the ACC as the 2018 BTI report claims that the situation remains unchanged as there have been reports that the police take bribes for releasing people arrested under dubious charges (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

A sense of impunity is widespread as the ACA has never convicted any high-profile politicians or business people. According to the ACC’s 2015 annual report, poor conviction rates due to shoddy investigations led to the acquittal of 207 out of 306 people convicted of corruption. Most corruption cases are politically motivated, and public faith in the ACC is absent (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

Comptroller and auditor general

The Office of the Comptroller and Auditor General (OCAG) is responsible as the country’s supreme audit institution for auditing government receipts and public spending. It is also tasked with ascertaining whether expenditures have yielded value for money in government offices, public bodies and statutory organisations. Appointed by the president of the republic, the comptroller and auditor general (CAG) heads the supreme audit institution. CAG has the mandate to determine the scope and extent of auditing (CAG 2018).

Although the OCAG audits government expenditures, it rarely requests that the government explain large-scale spending or points to irregularities in expenditure (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2018).

Law enforcement

A notable effort have been made to improve integrity in the country’s law enforcement agencies is the Police Reform Programme (PRP), sponsored by international development partners. It is a comprehensive capacity building initiative aimed at producing a more effective and representative police force (UNDP 2015). Under the reform programme, the police has doubled the number of female officers, set up 52,000 Community Policing Forums and the country’s first Victim Support Centre (UNDP 2015). Despite this, law enforcement bodies still occupy the highest rank in civilians’ experience of corruption according to TI-B’s 2017 National Household Survey (TIB 2017).

Other stakeholders

Media

The media and investigative journalism play a crucial role in bringing allegations of corruption to light and acting against impunity. Media reporting is an essential – albeit untapped – source of detection in corruption cases. International consortiums of investigative journalists are an example of an international cooperation that leads to tangible results in bringing financial and economic crime to the attention of the public and law enforcement authorities (OECD 2018).

The media tends to be polarised, aligning with one or other of the main political factions. Television is the most popular medium. The main broadcasters – Radio Bangladesh and Bangladesh Television (BTV) – are state-owned and government-friendly. BTV is the sole network with national terrestrial coverage. Satellite and cable channels and Indian TV stations have large audiences (BBC News 2017).

Some prominent bloggers who have written about Islamic fundamentalism have been murdered for their writing. Bloggers and social media users have been arrested on blasphemy-related charges (BBC News 2017).

Bangladesh ranks 146 in the 2018 World Press Freedom Index by Reporters Without Borders. Freedom House (2017b) rates the press in Bangladesh as “not free”. Physical violence and threats against journalists and bloggers continue with impunity, murders remain unsolved and other acts of violence go unpunished (Freedom House 2017b). Authorities are known to initiate legal action against journalists under restrictive laws, including defamation, sedition and the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act (Freedom House 2017b).

The draft Digital Securities Act, designed to replace section 57 of the ICT Act, has proposed even harsher penalties for vaguely defined crimes under national security, defamation and “hurting religious feelings” (Human Rights Watch 2018). Authorities periodically block access to certain news websites, including several known for criticism of the government, and, in 2016, internet access was shut down for several hours in parts of Dhaka (Freedom House 2017b).

According to some journalists and human rights NGOs, journalists engage in self-censorship particularly due to fear of security force retribution (US Department of State 2016; Freedom House 2017b). Freedom of association and assembly is guaranteed by the constitution but is not always respected in practice (Business Anti-Corruption Portal 2018).

Civil society

Civil society in any country plays a pivotal role in anti-corruption efforts. Not only does civil society act as a watchdog exposing cases of corruption, it also spreads awareness, proposes alternatives and offers a platform for a coalition of actors to work together (Kim 2009).

Over the years, Bangladesh has become a vibrant polity for the participation of various institutions in its development paradigm and governance structures, as well as anti-corruption efforts (Hosain 2018).

However, the Foreign Donations (Voluntary Activities) Regulation Act, which took effect in 2016, has made it more difficult for NGOs to obtain foreign funds and has given officials broad authority to deregister NGOs that make “derogatory” comments about government bodies or the constitution, which further curbs the independence of such organisations (Freedom House 2017a).

Nevertheless, a few notable civil society actors are:

Transparency International Bangladesh (TIB)

TIB is an independent, non-governmental, non-partisan and non-profit organisation dedicated to anti-corruption, good governance, accountability and transparency in the country (TIB 2018). It is a national chapter of the global anti-corruption NGO, Transparency International.

Starting as a trust in 1996, and later gaining NGO status in 1998, its mission is to catalyse and strengthen a participatory social movement to promote and develop institutions, laws and practices for countering corruption in Bangladesh and establishing an efficient and transparent system of governance, politics and business (TIB 2018).

The current 2014–2019 strategy, Building Integrity Blocks for Effective Change (BIBEC) aims to strengthen a series of mutually supportive and reinforcing “integrity blocks” to effectively reduce corruption. “Blocks” here imply the key institutions, policy/law, education, training, ethics and values and, above all, the people of the country (TIB 2014).

TIB’s website is primarily in English but has resources, reports and its corruption reporting tab in Bengali. It is highly informative on the corruption landscape and the organisation’s activities. It is currently the sole organisation in Bangladesh wholly dedicated to countering corruption and has the following areas of activity:

- Research and policy: TIB conducts diagnostic studies, household surveys, as well as national integrity system and Sustainable Development Goals assessments. In addition, it operates a parliament watch programme, and issues a citizen report card (TIB 2018). TIB also has an option on its website to report corruption (TIB 2018), and states that though the organisation has no power to act on the incidents being reported, the information is used for research purposes, and the ACC is informed about them (TIB 2018).

- Civic engagement: the organisation engages citizens to help counter corruption. A few notable programmes include the Committee of Concerned Citizens (CCC), Youth Engagement and Support (YES), Young Professionals against Corruption (YPAC), Mothers’ Gathering, Face-the-Public (FtP), and advice and information desks (AI desks).

- Outreach, communication and advocacy: in addition to these “bottom-up” approaches, TIB engages with the government, organising meetings with policymakers and public officials (TIB 2018). TIB’s sustained advocacy and engagement has contributed to a number of developments in the field of anti-corruption (TIB 2014).

- Finally, TIB hosts the Investigative Journalism Awards (since 1999, encouraging the exposure of systemic corruption), TI Integrity Awards (recognising the courage of individuals and organisations who have made a significant impact on reducing levels of corruption), cartoon competitions, debates, round tables, press conferences and seminars (TIB 2018).

The Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD)

CPD is a think-tank committed to contributing towards participatory policymaking. It primarily undertakes research and analysis, organises dialogues, produces publications and supports capacity building of relevant stakeholders (CPD 2018).

CPD’s research outputs as well as members have contributed to national and regional policy changes and initiatives in support of good governance, sound economic management and the interests of marginalised groups in the society (CPD 2018). For example, Professor Rehman Sobhan, the chairman and founder of CPD served as a member of the President’s Advisory Council (CPD 2018).

Other CPD researchers have also contributed to the policymaking process in Bangladesh as members of various committees and working groups like the Bangladesh Bank, Planning Commission, Ministry of Commerce, Ministry of Industries and Ministry of Agriculture (CPD 2018).

CPD’s on-going research areas include, but are not limited to, governance, corruption, anti-corruption, and service delivery (CPD 2018). A host of its research addresses the drastic effects that corruption has for various sectors in the country. For example, in a recent article published by The Daily Star, CPD’s research on the jute sector was used to highlight that it was corruption that was responsible for the losses in Bangladesh’s pivotal economic area (Pandey 2018).

The Independent Review of Bangladesh’s Development (IRBD) is CPD’s flagship programme that produces analyses of the macroeconomic performance of the Bangladesh economy as well as analyses and recommendations for the national budget, promoting fiscal transparency (CPD) 2018).

Apart from this, CPD hosts meetings, conferences and special events, as well as two global initiatives – Southern Voice on Post-MDG International Development Goals and LDC IV Monitor – in partnership with leading international think-tanks (CPD 2018).

SHUJAN – Citizens for Good Governance

SHUJAN, which identifies itself as a non-partisan pressure group, was founded in 2002 as an initiative of a group of concerned citizens. Its purpose is the promotion of democracy, decentralisation, electoral reforms, clean politics and accountable governance (SHUJAN 2018). It seeks to present the “voice of the people” to the government, policymakers and service-providing institutions (SHUJAN 2018). It consists of a decentralised network of committed individuals from the capital city down to the villages, it is not supported by donors; rather, it is a volunteer-based movement in which citizens invest both their time and money to do its work (SHUJAN 2018).

Its contributions include converting the existing electoral roll, prepared in 2000, into an online database and creating the template for an error-free electoral roll (SHUJAN 2018). Its website features laws of election, a list of political parties and their manifestoes, as well as a list of publications (SHUJAN 2018).

BRAC

BRAC, also known as Building Resources Across Communities, is an international non-governmental development organisation based in Bangladesh committed to social development in nine countries in Asia and Africa (Korngold 2017; BRAC 2018a). It is also the largest global anti-poverty organisation providing microloans, self-employment opportunities, health services, education, and legal and human rights services (Korngold 2018).

BRAC engages in several social accountability initiatives at the local level, and has its presence in all 64 districts in Bangladesh. It seeks to support women to take control of their lives as well as play an active civic role in the public sphere. It works to strengthen women-led community-based organisations, promoting pro-poor, responsive and accountable governance through a community-led development approach, and helps increase access to information (BRAC 2018a; BRAC 2018b).

Its methods include creating community-level forums through which people living in poverty can raise their voices and exercise their rights (Polli Shomaj), engaging through popular theatre and radio programmes, and promoting volunteers to facilitate a community agenda in local government (BRAC 2018b).

These BRAC programmes help strengthen local governance and increase accountability of administrative apparatuses.

- Hawala is an alternative remittance channel that exists outside traditional banking systems. Transactions between hawala brokers are made without promissory notes because the system is heavily based on trust and the balancing of hawala brokers' books. Hawala, also known as hundi, means transfer or remittance (Investopedia 2018).

- cAround the world, people talk about “corrupt cultures,” implying a predisposition of a group of people to behave in corrupt ways. Measures of corruption are in fact strongly correlated with “cultural variables” such as strong family ties, the traditional end of the World Values Survey’s (WVS) tradition-rational dimension, the survival end of the WVS’s survival-expressive dimension, individualism, and power distance. The decision to be corrupt involves both cultural norms and a calculation of risks and rewards. Klitgaard (2017) contents that the problem is not that people in certain cultures approve of corruption, but rather that they perceive conflicts between values: for example, between favouring one’s family and doing one’s civic duty.

- Percentile rank indicates the country's rank among all countries covered by the aggregate indicator, with 0 corresponding to lowest rank and 100 to highest rank (World Bank 2017a).

- Poor is defined as per the aforementioned World Bank threshold of people surviving on less than US$1.90 a day.

- In the late 2000s, a World Bank-led consortium agreed to fund a US$3 billion bridge in southern Bangladesh (ACE 2017). Shortly before the project was to begin, an unconnected investigation implied that a Canadian company had been planning to bribe ministers in Bangladesh to win a contract (ACE 2017). The World Bank insisted that the minister referred to in the documents should be included in a full investigation, and though the government eventually agreed to an investigation by the anti-corruption commission, it exempted the minister. The World Bank eventually withdrew from the project in the absence of a satisfactory investigation, and the Bangladesh government found more expensive financing from Chinese sources. The cost of construction was also inflated several times in the absence of any credible external monitoring of contracting and costs. Ultimately, the anti-corruption exercise failed to root out corruption, and may even have strengthened the corrupt, by demonstrating that pressure from international partners could be resisted (ACE 2017).