Query

Please provide an overview of development challenges related to corruption in North Macedonia in the following areas: a) human rights, democracy, the rule of law and gender equality; b) peaceful and inclusive societies; c) environmentally and climate-resilient sustainable development d) inclusive economic development.

Background

A hybrid regime

North Macedonia has made some notable democratic reforms since a major political transition began after the elections in 2016, which marked the end of the 11-year rule of the Internal Macedonian Revolutionary Organisation – Democratic Party for Macedonian National Unity (VMRO-DPMNE). However, important challenges related to state capture, corruption in the judiciary and an unreformed public administration remain (Taseva 2020; BTI 2020; Bliznakovski 2021).

Three decades after the start of its political transition, North Macedonia is still in the process of transitioning to democracy, and it belongs to the category of transitional or hybrid regimes, according to the Freedom House’s Nations in Transit (Bak 2019; Bliznakovski 2021).

Indeed, several prominent governance indices consider the country to be some way from a fully functioning democracy. Freedom House (2021) judges the country to be only “partly free”, given that “journalists and activists face pressure and intimidation”. The Economist Intelligence Unit (2021: 10) declares North Macedonia to be a “hybrid regime”, a form of governance marked in many countries by a number of characteristics. Elections, while regular, may not be “free and fair” in hybrid regimes due to substantial irregularities. Although media are generally free, they are often under the influence of special political and economic interests, which affects their independence. In these kinds of regimes, the judiciary may struggle to remain independent from the government and equality before the law is not guaranteed, while corruption can be widespread, presenting an obstacle to successful economic development (Freedom House no date). Moreover, government may exert pressure on non-parliamentary opponents, limiting the space for political participation, and public administration is generally at least partly dysfunctional (Economist Intelligence Unit 2021: 57).

Similar to other Western Balkan countries, after the dissolution of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (SFRY), North Macedonia faced the challenge of a triple transition: managing both political and economic transformation while seeking to consolidate a functioning nation state (Offe and Adler 1991; Keil 2018; Bak 2019; Duri 2021).

The initiation of a privatisation process to sell off state assets in the context of underdeveloped institutionsb2cf6b6b5f8b in the 1990s, as well as widespread smuggling incentivised by embargoes in the region, led to the consolidation of wealth in the hands of a relatively narrow economic elite. In turn, this powerful group of magnates used their political connections to further consolidate their position and secure favourable political outcomes (Keil 2018; Taseva 2020). It was this growth in informal networks between politicians and businesspeople that paved the way for systematic state capture to emerge in the 1990s (Taseva 2020: 9).

Academic and policy research has demonstrated that state capture is among the key factors that hinder the democratic transition reform process in post-communist countries (Hellman 1998; Tudoroiu 2015; Keil 2018). State capture has been recognised as a serious concern in the Western Balkans, including in North Macedonia,where informal ties between political and economic elites have enabled political parties to capture institutions through patronage, cronyism, and clientelism (Kraske 2017; Bartlett 2020; Taseva 2020; Resimić2022).

The challenge of state capture in the Western Balkans has recently been acknowledged by the European Commission (EC). When launching a new strategy for the Western Balkans in 2018, it emphasised the need for comprehensive governance reform as a prerequisite for potential future EU membership (EC 2018).

Further, the European Commission's 2020 strategy stressed the need for addressing corruption in the Western Balkans and emphasised the challenges related to poor governance and limited progress in improving the rule of law (EC 2020: 3; Duri 2021).

Some recent studies suggest that Western Balkan countries have made progress when it comes to technically complying with the formal requirements for EU membership. They note, however, that this technical compliance has not been accompanied by substantial or meaningful improvements in the quality of democracy in these countries (Richter and Wunsch 2020).

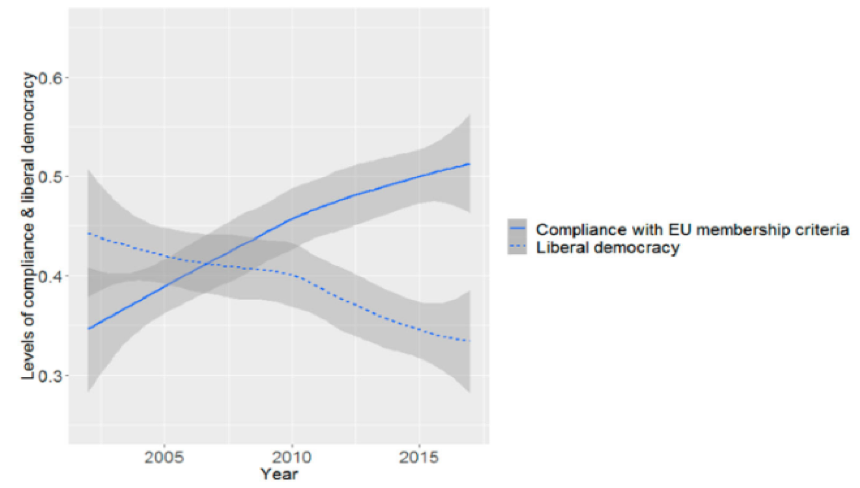

The observed decoupling in the Western Balkans between progressive improvements in terms of formal compliance with EU membership criteria on one hand, and de facto democratic performance on the other has been attributed to state capture, which may have emerged partly as an unintended consequence of the EU conditionality (see Figure 1 from Richter and Wunsch 2020).

Figure 1. Decoupling of formal compliance and democracy levels in the Western Balkans.

Source: Richter and Wunsch 2020: 44.

For example, Richter and Wunsch (2020) suggest that the strong pressure for market liberalisation and democratisation in the Western Balkans created lucrative opportunities for business actors to develop close and occasionally illicit ties with politicians. Recent political change

In the case of North Macedonia, VMRO-DPMNE lost power after the 2016 elections. These elections came after the Wiretapping affair, which involved the leak of taped conversations in February 2015 by then opposition leader Zoran Zaev (who claimed that the recordings were leaked to the opposition), documenting evidence of government officials “plotting to rig votes, buy off judges and punish political opponents” (Taseva 2020: 11-12). This scandaluncovered the extent of malfeasance on the part of the VMRO-DPMNE led government and shed light on the extent of state capture by the ruling political parties (BBC 2016; Damjanovski 2016; Bliznakovski 2017; Deskalovski 2017).

Following an EU-led mediation, the four main political parties signed the Pržino agreement as an attempt to resolve the political crisis and pave the way for early general elections in 2016 (Damjanovski 2016; EC 2016: 4). After the elections, the new coalition government was composed of the Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM), the Democratic Union for Integration (DUI) and the Alliance for Albanians (AA). Zoran Zaev of SDSM became the prime minister (Bliznakovski 2018). The transfer of power was impeded by the attempts of VMRO-DPMNE to paralyse the parliament. The political crisis culminated with the storming of the parliament building by the nationalist group backed by VMRO-DPMNE in April 2017, after the new coalition government elected an ethnic Albanian as the new speaker (Bliznakovski 2018). In 2021, four former senior officials were convicted of organising the storming of the parliament building, including the former president of the parliament, two ex-ministers and a former intelligence officer (Euronews 2021). They were found guilty of endangering the constitutional order (Marušić 2019).

Following these general elections, the new government expressed a strong commitment to pursue Euro-Atlantic integration. The name dispute with neighbouring Greece was resolved in 2018 with the Prespa agreement, which opened the space for commencing accession negotiations with the EU. Then, North Macedonia joined NATO in March 2020. However, although accession negotiations with the EU were expected to begin in 2020, Bulgaria vetoed North Macedonia's bid, citing arguments over language and shared history (DW 2020; Makszimov 2021).

After the following general elections in July 2020, SDSM and DUI once again formed a coalition government, which included the Besa movement and the Democratic Party of Albanians (DPA) (Bliznakovski 2021). However, the local elections in October 2021 heralded the return of VMRO-DPMNE, which managed to win almost every major city in the country, including the capital, Skopje (Nechev and Marković 2021). There are different interpretations of these results, but they are likely the result of a confluence of several developments. One is public frustration with the stalled EU integration process, while another factor is reportedly the lack of progress in curbing high-level corruption involving senior government officials (Nechev and Marković 2021).

Extent of corruption

Despite some positive developments that accompanied the change in political power in North Macedonia after the 2016 elections, corruption remains one of the key obstacles to democratic transformation, as evidenced by international governance indices that point to the country's lack of progress in curbing corruption.

According to Transparency International's Corruption Perception Index (CPI), North Macedonia scored 39 on a scale of 0 (most corrupt) to 100 (least corrupt) in 2021 (Transparency International 2020; Cuckić 2021). While the country witnessed a progressive decline from a score of 45 in 2014 to 35 in 2020, the 2021 rating represents a four point improvement from 2020. North Macedonia currently ranks 87 out of 180 countries, while in 2014 it ranked 64 (Taseva 2021).

Table 1: Western Balkans Countries’ scores in the 2021 CPI. Source: Transparency International 2022

|

Country |

2021 CPI score |

|

Albania |

35 |

|

Bosnia and Herzegovina |

35 |

|

Kosovo |

39 |

|

Montenegro |

46 |

|

North Macedonia |

39 |

|

Serbia |

38 |

As such, the only country in the region to perform better than the global average CPI score of 43 is Montenegro (Duri 2021: 3). As noted by Taseva (2021), problems of politicisation and corruption in public employment procedures, which will be discussed in detail in the following sections, are particularly challenging.

North Macedonia likewise fares poorly on the World Governance Indicators (WGI) dataset developed by the World Bank. The country scores particularly badly on the “control of corruption” variable, which measures the strength of public governance via perceptions of the extent to which a public power is exercised for private gain (including both petty and grand corruption), with a rating of -0.42 on a possible range of -2.5 (worst) to 2.5 (best) (Duri 2021; Bartlett 2020; World Bank 2021). Its percentile ranking on the WGI Control of Corruption indicator is 38 (the ranking ranges from 0 (the lowest) to 100 (the highest) (World Bank 2021).

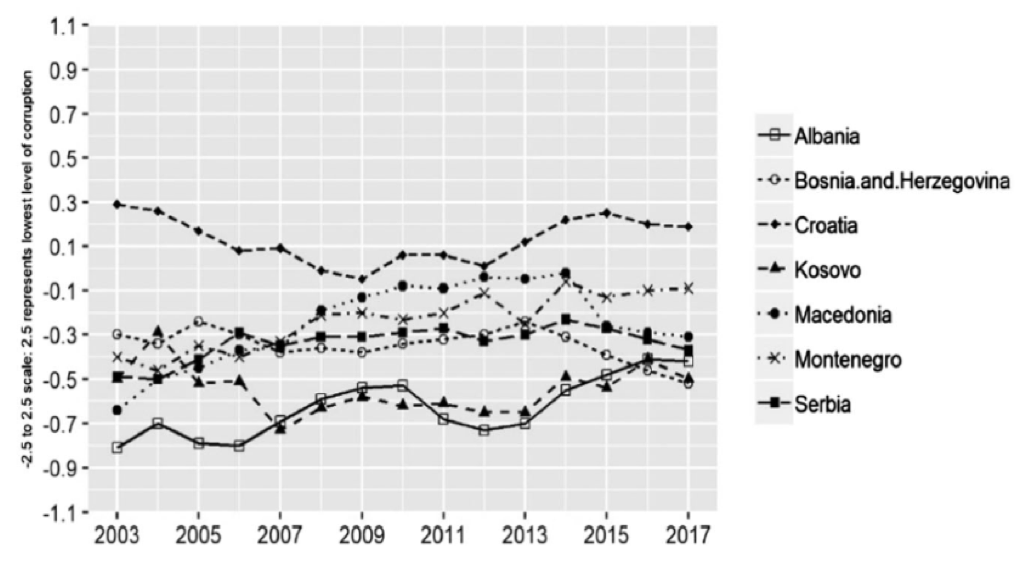

If we put the “control of corruption” scores in a comparative perspective with other Western Balkan countries over a longer period of time (Figure 2), we can observe a general stagnation across the region, with North Macedonia declining sharply after 2014 (Richter and Wunchs 2020), a trend which has subsequently continued (World Bank 2021).

Figure 2. Control of corruption in the Western Balkans.

Source: Richter and Wunsch 2020: 55.

The picture we can gather from the expert assessments referred to above is corroborated by citizens’ own perceptions. Citizens’ trust in the government has declined since 2007 in the Western Balkans, and North Macedonia is no exception to this trend (OECD 2020).

A survey conducted in the summer of 2021 showed that 28.3% of respondents named crime and corruption as the most serious problem facing North Macedonia today (NDI North Macedonia 2021). The major reasons for corruption, according to the surveyed citizens, include failure to take actions against those involved in criminal activities, such as court sentences and confiscation of property, and that the laws, while they do exist, are not implemented in practice (NDI North Macedonia 2021).

Further survey evidence reveals there is little trust in the judiciary in North Macedonia, with 52% of respondents stating that they do not trust the judiciary (EPI Institute 2020; Taseva 2020). Forty-one percent of respondents named corruption as the biggest factor contributing to distrust towards courts. The second most important factor contributing to distrust was a suspicion of political influence. While 34% of respondents said they think there is political influence in courts, a further 31% said the same for the Public Prosecutor's Office (EPI Institute 2020). A recent survey conducted by Romalitico found that more than 90% of respondents do not file complaints when denied access to certain social rights and entitlements due to a mistrust in institutions (Kareva et al. 2021).

Further, petty corruption is widespread in North Macedonia. A survey from 2019 revealed that almost a third of respondents reported having been solicited for a bribe in the previous year, while 23% reported bribing an official in the same period (Nuredinoska et al. 2020). The same survey showed that 45% of respondents said they believe that most public servants are involved in corruption.

Forms of corruption

Academic and policy research in North Macedonia suggest that there are two pressing forms of corruption that pose a significant challenge to the successful democratic transition: state capture and corruption in the judiciary (Kiel 2018; Richter and Wunsch 2020; Taseva 2020, 2021; Zúñiga 2020).

State capture

The standard understanding of state capture emphasises the role of an autonomous business class that colonises the state to achieve narrow benefits (Hellman 1998; Hellman et al. 2003).

However, the experience of post-communist countries, including North Macedonia, shows firstly, the key role that political parties play in driving the state capture dynamic and, secondly, the existence of complex political-business networks that sustain these processes (Fazekas and Tóth 2016; Resimić 2021).

Consequently,a recent study on state capture in the Western Balkans (Zúñiga 2020) and a related report on North Macedonia (Taseva 2020) adopt the definition of state capture proposed by Fazekas and Tóth (2016), according to which state capture refers to efforts of public and private actors to direct public policy decisions away from the public interest. State capture occurs where clusters of repeated corrupt interactions come to dominate institutions that control lucrative processes, such as procurement and market regulation, key political decision-making organs and law enforcement actions (Fazekas and Tóth 2016).

Zúñiga's 2020 report on state capture in the Western Balkans found that impunity for high-level corruption and tailor-made laws are the result of patronage and clientelist networks. The role of political parties is crucial in understanding the structure and operation of these networks.

Although North Macedonia underwent an important political change in 2016, the evidence suggests that this has not put an end to state capture (Deskalovski 2017; Taseva 2020). Some of the practices and mechanisms of capture remain untouched. One explanation for this continuity lies in the organisational entanglement of political parties and firms. While firms need political parties to get favourable business opportunities, political parties need firms to secure political finances to win elections (Stark and Vedres 2012; Schoenman 2014). While these ties are not necessarily corrupt, they are resistant to disruption in contexts in which the rule of law is poor and the judiciary is weak, which, as discussed below, is the case with North Macedonia. Examples of court cases against two former prime ministers being dismissed after the statute of limitation expired, and the fact that the former prime minister NikolaGruevski escaped to Hungary by car via Albania and Montenegro while no one was held accountable, suggest the persistence of the role of political networks (Taseva 2020: 6; BTI 2020).

Corruption in the judiciary

The extent of political interference over the judiciary was exposed during the Wiretapping affair, which illustrated the scale of capture of this branch of government. It demonstrated that the ruling political elite was involved in electing judges that are close to them (BTI 2020). In the Assessment of the Senior Experts' Group on Rule of Law Issues in North Macedonia (EC 2017: 4), it was noted that there is a present misuse of the judicial system by “a small number of judges in powerful positions” who serve political interests. They note that this group of judges exerts pressure over junior colleagues to control the process of appointment, evaluation, promotion and dismissal, and in this way discipline those who do not conform. The report describes this process as "the capture of the judiciary and prosecution by the executive power” (EC 2015: 4-5).

It is perhaps unsurprising, therefore, that 42.4% of citizens surveyed in North Macedonia recently stated that they “have no trust at all” in courts, making it the least trusted institution, even compared to political parties (NDI North Macedonia 2021). Similarly, 36.8% said that they “have no trust at all” in the public prosecutors office, making it one of the top three least trusted institutions, along with courts and political parties (NDI North Macedonia 2021).

The need for judicial reform in North Macedonia has been recognised for years in European Commission reports. For example, in the 2016 report, it was noted that there has been a backslide in judicial reform since 2014, characterised by recurrent political interference in the judiciary and its lack of independence (EC 2016: 4). Further, the Recommendations of the Senior Experts' Group on systemic Rule of Law Issues (hereinafter: Recommendations) (EC 2015: 9), following the Wiretapping affair, noted that there is evidence of an “atmosphere of pressure and insecurity within the judiciary”. Moreover, the Recommendations (EC 2015: 9) note that many judges think promotion within the judiciary system is reserved for those who make decisions in favour of political actors.

Reports more recently have noted some progress in the judiciary. For example, a strategy to reform the judicial system was adopted in 2017 (Republic of North Macedonia Ministry of Justice 2017; Taseva 2020), building on the earlier European Commission assessment reports, the above-mentioned Recommendations and others. The strategy acknowledged serious challenges within the judiciary, such as the inconsistent implementation of legislation (Republic of North Macedonia Ministry of Justice 2017: 5).

The 2018 GRECO report noted some progress in strengthening the independence of judiciary. Namely, the report welcomed the amendments to the law on judicial council which placed less emphasis on the quantitative criteria of a judge's performance (GRECO 2018: 10).

The latest European Commission report (2021) noted some improvement with regards to the judiciary and fundamental rights. Namely, it recognised some progress in strengthening judicial independence and addressing police impunity (EC 2021: 17). Furthermore, it noted that the implementation of the judicial strategy is moving forward on the Law on Public Prosecutor's Office, and in relation to accountability for the crimes tied to the Wiretapping affair (EC 2021: 17). It also recognised the efforts of the State Commission for the Prevention of Corruption (DKSK) in delivering results which include high-profile cases (EC 2021: 17).

In the GRECO (2020: 14) report, it was noted that the law on prevention of corruption and conflicts of interest offers conditions for independence and professionalism of the DKSK by revising “the regulation of the terms of selection and appointment” of its members. Further, recently adopted amendments to the law on courts, the law on the judicial council and the codes of conduct for judges are important improvements (Taseva 2020: 13). For example, the GRECO (2020: 7) report welcomed measures to strengthen the independence of lay judges,343a746a5c93 such as extending the code of ethics for judges to incorporate lay judges. Further, it welcomed the amendments to the law on courts of 2019, which introduced a change in disciplinary mechanisms with regards to clarifying “disciplinary infringements applicable to judges” within the procedure to discipline and dismiss a judge (GRECO 2020: 9).

Nonetheless, a report on state capture in the Western Balkans and the case study of North Macedonia (Zúñiga 2020; Taseva 2020) revealed that political parties continue to exert influence over the judiciary and negatively affect the prosecution of high-level corruption cases.

The case of the Special Public Prosecutor's Office (SPO), which was established in 2015 after the emergence of the Wiretapping affair (Ozimec 2016; Taseva 2020), illustrates how corruption affects the integrity of the judiciary and its institutions. The SPO charged 94 individuals and seven legal entities in 18 corruption cases related to the Wiretapping affair (Mackie 2017). However, the SPO collapsed in 2019 (and ceased to function soon thereafter, in September 2019), after the Special Public Prosecutor (SPP) resigned due to her involvement in corruption in the case known as the Extortion Affair (Lukić 2019). SPP Katica Janeva was accused of involvement in extortion and racketeering against businessman Jordan Kamčev (Republika 2021a). The trial had a political dimension as, during the trial, allegations against prime minister Zoran Zaev and key people of the regime were made for their alleged involvement in the extortion (Republika 2021a). Janeva was later sentenced to seven years in prison due to abuse of office and authority (Taseva 2020: 12; Samardžiski 2020). While SPO had a promising start, the results were poor. Overall, there were 40 unfinished processes after four years of work and only three completed cases (Trpkovski 2019; Taseva 2020). The cases of SPO were returned to the Public Prosecutor's Office (Zúñiga 2020: 5).

Finally, the most recent GRECO (2020: 6) report noted ongoing challenges in judicial independence that require meaningful reform. Namely, to strengthen the independence of the judiciary to prevent undue political influence, they recommended abolishing the ex officio position of the minister of justice in the judicial council. This is due to the danger that when a minister of justice has a position in the judicial council, they may exert political influence, even when they have no voting rights (GRECO 2020: 7). This recommendation, however, has not been implemented in North Macedonia yet. In addition, further measures are needed to establish and enforce consistent rules and codes on the professional conduct of prosecutors (GRECO 2020: 10).

As Taseva (2020: 35) concludes, while there have been some reforms, overall, the criminal justice system remains vulnerable to grand corruption as it has trouble detecting and prosecuting high-level corruption and is unable to prevent the politicisation and capture of institutions by partisan interests.

Corruption by theme

The following section discusses how the key forms of corruption in North Macedonia affect four broad spheres that are central to a successful democratic transformation:

- human rights, democracy, rule of law and gender equality

- peaceful and inclusive societies – creating conditions for inclusive reconciliation and conflict and violence prevention efforts

- environmentally friendly and climate-resilient sustainable development and sustainable use of natural resources

- inclusive economic development

Human rights, democracy, rule of law and gender equality

This subsection's primary focus is on the rule of law as this is the area most critically affected by the two forms of corruption discussed in the previous section. The following discussion is not exhaustive but it aims to address the most significant challenges in North Macedonia within this broad theme.

Democracy levels in North Macedonia over the last decade havebeen characterised by a declining trend. As shown in Table 2, although the North Macedonia's democracy score, according to Freedom House, improved over the last three years, it is now lower than it was 10 years ago.

|

Year |

Score |

|

2010 |

4.21 |

|

2011 |

4.18 |

|

2012 |

4.11 |

|

2013 |

4.07 |

|

2014 |

4.00 |

|

2015 |

3.92 |

|

2016 |

3.71 |

|

2017 |

3.57 |

|

2018 |

3.64 |

|

2019 |

3.68 |

|

2020 |

3.75 |

While the Freedom House's Nations in Transit score for North Macedonia in 2020 is slightly above the average for the Balkans,ed1c97b0df23 the Bertelsmann Foundation classifies North Macedonia as a defective democracy with weak rule of law (BTI 2020).

Politicisation of public administration is an important challenge for North Macedonia as the influence of political parties on recruitment processes in public administration is significant. VMRO-DPMNE made a concerted effort to capture the public administration by putting in place loyalists during their decade-long rule to establish strong clientelist networks (Cvetkovska 2012; Lyon 2015). The Wiretapping affair brought some of these practices to light, such as threatening to fire public officials unless they voted for the incumbent party at elections (Džankić 2018).

There is some evidence that these practices continued after the change in political power in 2016. The fact that the recruitment process is driven more by partisan loyalty than by meritocracy is a human rights issue as well as it deprives those who are not members of political parties of equal opportunities to apply for positions in the public administration. The State Commission for Prevention of Corruption and Transparency International Macedonia recently completed a project assessing integrity issues in employment practices in the country. The project resulted in a number of recommendations to address vulnerabilities in public employment policies to rectify issues of nepotism, clientelism and cronyism (DKSK and TI Macedonia 2019).

These recommendations included, for example, the need to reduce discretion by “establishing clear criteria in internal announcements” in public sector institutions (DKSK and TI Macedonia 2019: 4). The project also recommended tightening up procedures related to the appointment of directors of public enterprises and public institutions.

One suggestion was to form a commission that would act “upon the documentation for election” for the above-mentioned positions (DKSK and TI Macedonia 2019: 12). The commission, it is proposed, should include a representative of the institution or an enterprise for which the director is being elected/appointed, an NGO sector representative, a representative of the DKSK and the secretary of the municipality, as well as a representative of the professional and scientific community (see further in DKSK and TI Macedonia 2019: 12).

A recent monitoring report suggests that there is a generally low level of implementation of recommendations stemming from the project (TI North Macedonia 2021: 8). Overall, analysis suggests that the political capture of employment practices in public administration has serious negative consequences on human rights, the rule of law and the general satisfaction of young people with regards to opportunities in the country. There is thus a need to improve the human resource management and hiring practices to reduce nepotism and clientelism in public administration and state-owned companies (see DKSK and TI North Macedonia 2019).

A recent study shed light on the practice of issuing tailor-made laws in the Western Balkans (Zúñiga 2020; Taseva 2020: 29). The research from North Macedonia demonstrated that tailor-made laws have three main purposes: to control an industry or a sector, to achieve impunity for corruption and to avoid checks and balances (Taseva 2020: 29).

Two prominent are the amnesty law of 2018 (Zúñiga 2020) and the amendments to the criminal code of 2018, which lowered the sentence for misuse of public procurement (Taseva 2020: 29). The amnesty law practically exempted from criminal prosecution anyone suspected of committing a crime during the storming of the parliament building in April 2017, with the exception of the organisers and those who committed physical violence (Zúñiga 2020: 19; AP 2018).

Further, amendments to the 2018 criminal code lowered custodial sentences for cases involving the misuse of public procurement with significant damages or value (Taseva 2020). This is especially problematic considering that the process of public procurement is particularly prone to corruption, as (Fazekas and Tóth 2016; Wachs et al. 2020). A case in point is the public procurement of a luxury car worth close to €600,000. In this instance, the special prosecution office launched an investigation under the codename Tenk in 2017 (Taseva 2020). A court in Skopje found that Nikola Gruevski, while he was the prime minister, influenced two officials regarding the procurement of the Mercedes Benz vehicle in 2012 (BBC 2018). Prosecutors demonstrated that Gruevski exerted influence over a member of the tender commission to favour “a particular car dealer to supply the vehicle for his personal use” (BBC 2018). The influence resulted in an irregular procurement giving favourable treatment to a certain bidder without following the tender conditions (Taseva 2020). This case exemplifies how open competition can be altered under the political influence of high-level officials who abuse their power to achieve narrow private interest, resulting in wasteful spending of public resources.

A recent study on state capture in the Western Balkans (Zúñiga 2020) and in North Macedonia (Taseva 2020) revealed that, although DKSK has stepped up its efforts to tackle high-level corruption, its overall impact is still limited. In 2019, the DKSK worked on 1,165 cases, out of which only 8% of cases were launched based on the body's own initiative (Fakik 2020: 9-10). It played a role in only 8 criminal and 24 misdemeanour charges in 2019, out of 299 closed cases in 2019 (Fakik 2020: 11; Bliznakovski 2021). In the first half of 2020, DKSK reviewed 196 cases and found grounds for further action in only 7% of them (Bliznakovski 2021).

Peaceful and inclusive societies

North Macedonian political dynamics are still shaped by ethnic divisions. This has consequences for how corruption manifests itself.

The Ohrid Framework Agreement (OFA) had its 20th anniversary in August 2021. This agreement ended an internal inter-ethnic conflict and provided a more inclusive arrangement for ethnic minorities, particularly the Albanian ethnic group (Bliznakovski 2017: 61). In accordance with the OFA, positions in public administration were distributed according to the principle of equitable representation of national minorities at state and municipal levels (Džankić 2018). There is some suggestion that positions for minority representatives tend to be distributed in line with political party membership (Džankić 2018; Lyon 2011).

Another important challenge in the Western Balkans relates to organised crime, as these countries are hubs in Europe for organised criminal activities, often involving drugs and human trafficking (GI-TOC 2015; UNODC 2020).

Based on conviction data, organised criminal activities in North Macedonia are most frequently related to smuggling of migrants and drug production and trafficking (UNODC 2020: 81). According to the latest Global Organised Crime Index, North Macedonia has a criminality score of 5.32, which places it 74 out of 193 countries, and a resilience score of 5.21, which places it at 76 (GI-TOC 2021). The report (GI-TOC 2021: 3) notes that illicit markets in the country are dominated by loose criminal networks, of which many are based upon ethnic or family ties, which points to the strong role that ethnic identity plays. The report also notes the existence of collusion between state actors and criminal groups, and to some extent of capture of state institutions and politicians (GI-TOC 2021: 4).

There have, however, been some positive developments in recent years in tackling the relationship between politicians and criminal groups, such as efforts to restore checks and balances and increase transparency by requiring ministers to declare their spending (GI-TOC 2021: 5).

Further, UNODC (2020: 85) states that there is a strong link between money laundering and organised crime in North Macedonia. Money laundering is most frequently linked to financial fraud, smuggling, tax evasion and corruption. A recent case involves Risto Novačevski, the best man of the former prime minister Gruevski, who is a suspect in a case of money laundering and the illicit purchase of building lots. Gruevski was the first suspect in the case, accused of using scam tactics (illegally taking money either in person or through the municipal committees of his political party, which were intended as party donations but were allegedly not reported in the party's financial reports) to illicitly accumulate over €1 million between 2006 and 2012 when he was prime minister (Marušić 2020a).

Organised crime also has negative consequences for the environment, partly due to low penalties for environmental crimes (GI-TOC 2021). How corruption affects the environment is discussed in the following section, but the role of criminal groups is key to this discussion. This is illustrated by a recent case in which dangerously polluted oil flooding into the country ended up being used in the heating system of several public institutions, a scheme that allegedly involved organised crime groups and corrupt government officials (Cvetkovska et al. 2021; Cvetkovska 2021; Duri 2021).

In 2016, North Macedonia adopted a law which enabled the production of cannabis for medical use and the export of medicinal cannabis extractions. The distribution of licences for cannabis cultivation drew a lot of attention as they were allocated to individuals close to the ruling political party and to former politically exposed persons (Reitano and Amerhauser 2020: 20; Makfax 2020).

Finally, organised crime in the Western Balkans has a regional component. A recent study suggests that criminal groups from Albania, Kosovo and North Macedonia cooperate with each other in various businesses, such as migrant-smuggling networks (Reitano and Amerhauser 2020: 19).

Environmentally friendly and climate-resilient sustainable development

A recent Transparency International's Helpdesk answer (Duri 2021) provides a detailed overview of corruption in the environment sector in the Western Balkans. It suggests that deeply embedded patronage networks and the dynamic of state capture have led to the frequent award of contracts in the natural resources sector to ruling political elites and their cronies (Duri 2021). This is particularly clear in the process of allocating state subsidies for hydropower projects, which is characterised by widespread corruption (Duri 2021). Indeed, the lucrative potential of the hydropower sector has attracted economic actors and exacerbated corruption (Duri 2021).

North Macedonia is not an exception in this respect as there are also tailor-made laws for the environmental sector. For example, in the energy sector, regulation no. 2929da0df3cdde introduced two types of support for producers using renewable energy sources: feed-in tariffs and premiums. This regulation particularly benefited hydropower producers, some of which are politically connected (Balkan Green Energy News 2019; Gallop et al. 2019; Zúñiga 2020: 17-18; Taseva 2020).

The new regulation was particularly advantageous for a company called Small Hydro Power Plants Skopje, whose manager is Todor Angjušev, the brother of deputy prime minister Kočo Angjušev (Zúñiga 2020).

Furthermore, Kočo Angjušev founded a company called Feroinvest with his brother in 2003. This firm operates several hydropower plants. Although Angjušev stepped down from the management position of Feroinvest in 2016, he still takes part in drafting legislation for the energy sector, which opens the question of potential conflict of interest (see Zúñiga 2020: 18; Gadžovska Spasovska and Kalinski 2019; Taseva 2020: 32). As reported by Radio Free Europe, Kočo Angjušev, either directly or indirectly, controls a third of small hydropower plants in North Macedonia (Gadžovska Spasovska and Kalinski 2019).

As with other Western Balkan countries, there is a backlash against these hydropower schemes among environmental activists, who point out that concessions are distributed in an opaque manner, and that the corruption in the decision-making process leads to the approval of projects that have led to considerable environmental damage (Todorović 2020).

Further, the challenge of politicisation in employment practices is widely present in the environment sector too, particularly in the energy sector in all Western Balkan countries. This typically occurs through the installation of political party loyalists or members as directors or as members of boards of directors. Indeed, political appointments to director and management positions in state-owned enterprises (SOE) in the energy sector are a common practice in North Macedonia (Southeast European Leadership for Development and Integrity 2016: 3). In North Macedonia, the Wiretapping affair revealed that the head of the prime minister's cabinet allegedly instructed the CEO of ESM (Електрани на Северна Македонија – Power Plants of North Macedonia) ELEM to hire people from a list prepared by the Ministry of Interior (Southeast European Leadership for Development and Integrity 2016: 3).

This comes against a background in the energy sector of widespread mismanagement of SOEs, abuse of public subsidies, rigged public procurement processes as well as the persistence of monopolies and cartel behaviour among suppliers (Southeast European Leadership for Development and Integrity 2016: 2). In North Macedonia, this is particularly problematic in the energy sector, where the restriction of competition is a frequent challenge (Southeast European Leadership for Development and Integrity 2016: 8).

Thus, efforts towards reforming corporate governance are needed to depoliticise SOEs and limit the abuse of public resources and corruption risks that come with political appointments (see Southeast European Leadership for Development and Integrity 2016: 3). Simultaneously, efforts are needed to increase the transparency in the financial governance of these SOEs (Southeast European Leadership for Development and Integrity 2016: 15-16).

Recent protests by citizens and ecological movements, as well as grassroot campaigns aimed at educating people about the damage of concessions to various mining companies, indicate that there is a lot of space for international actors to push for transparency in concessionary projects that involve mining and potentially harmful to the environment (see Stojadinović 2020; Todorović 2020).

Another important threat to the environment stems from illegal logging in North Macedonia, involving organised crime groups. It appears in various forms, such as illegal logging in public forests and illegally obtaining logging authorisations via bribes. Illicit actors use threats, physical violence and corruption to facilitate illegal logging (Stefanovski et al. 2021; Duri 2021). Research into illegal logging suggests the existence of several forms of organised crime, including

collusion between illegal loggers and members of forest enterprises and the forest police, whereby the illegal actions are facilitated by bribes

initial legal logging in forests that are managed by the PENF (Public Enterprise National Forests) who hires subcontractors. These subcontractors may engage in illegal logging, colluding with the employees of the Ministry of Interior and occasionally with public prosecutors, in case a criminal investigation is launched (Stefanovski et al. 2021: 35).

These practices have serious negative consequences as they lead to deforestation, and data suggests that North Macedonia lost 38,600 ha of tree cover between 2001 and 2019 (Stefanovski et al. 2021: 8).

Finally, one important danger stemming from capturing key state agencies in the environment sector (particularly in renewables) is that the perception of corruption and nepotism negatively impacts public acceptance of transitioning towards energy efficient and renewable systems (see Gallop et al. 2019: 5; Duri 2021). For example, the fact that well entrenched businesses benefited from the incentive system (i.e. subsidies) for small hydropower plants, while regular people had little access to incentives, contributes to the feeling of public resentment (Gallop et al. 2019: 5). The extent of opposition from citizens and environmental groups mentioned above reflects the lack of transparency and the existence of corruption in a number of environment related projects.

Inclusive economic development

North Macedonia's economy is dominated by the state as the largest employer. As mentioned in the first subsection onhuman rights, democracy, rule of law and gender equality, in the context of partisan influence on recruitment practices in public administration, economic opportunities for younger people are reduced, pushing many of them to emigrate. This results in a brain drain as young people do not see a future for themselves in their own country. The data suggests that the unemployment rate among young people is at a high of 46.7%, based on 2017 data, although the trend is declining (ILO 2019).

Bank related fraud and bank collapses are important challenges affecting the business environment in North Macedonia. The collapse of the Eurostandard Bank in 2020 led to an investigation by the Public Prosecutor's Office in early 2021 (Dimitrievska 2021).

The Central Bank of North Macedonia revoked the licence of the Eurostandard Bank due to its failure to meet legal requirements for operation. It was announced that the investigation will include the bank's owners, Trifun Kostovski, former mayor of Skopje, and his son, for their alleged involvement in money laundering and causing the bankruptcy of the bank via illegal activities (Dimitrievska 2021).

There were also claims from the opposition party VMRP-DPNE that 29 firms close to prime minister Zoran Zaev's family, including his brother Vice Zaev, did not repay their loans to Eurostandard Bank (Dimitrievska 2021; Republika 2021b). The owner of Eurostandard Bank, Trifun Kostovski accused the ruling SDSM of being responsible for the bank's collapse. In particular, he claims that the manager entrusted to run the bank gave loans to firms tied to the SDSM party (Republika 2021c).

Other suspicious behaviour in the collapse of the Eurostandard Bank relates to the Minister of Finance, Nina Angelovska, who withdrew her deposits two months before the bank's collapse. This raises the question of whether she used insider information on these developments to save her deposits (Republika 2021d).

The relative size of informal economy in North Macedonia is one important factor that negatively affects inclusive economic development. Some efforts have been made to reduce the informal economy (UNDP 2021). Based on 2016 data, informal employment constituted 18.5% of total employment and was more prevalent among young people and older workers (ILO 2019).

Due to the size of the informal economy, the tax revenue is lower than in other parts of Europe. Tax evasion is a common feature of informal economies, which has negative consequences for the credibility of state institutions and the ability of states to pursue socio-economic goals (Reitano and Amerhauser 2020: 23).

Evidence suggests that profits are mainly transferred to offshore destinations. In the case of North Macedonia, popular destinations include Bermuda, Bahamas, Seychelles and Panama. Most of these funds are then reinvested into the country in the form of investments from such offshore locations, and experts believe that this is one way in which illicit financial flows (IFFs) are entering the country (Reitano and Amerhauser 2020: 24).

Legal and institutional anti-corruption framework

North Macedonia is a signatory of a number of relevant international anti-corruption conventions and initiatives, and it also has important domestic legislation in place.

Legal framework

International conventions and initiatives

North Macedonia has ratified a number of relevant anti-corruption treaties, including:

- Council of Europe’s Criminal Law Convention on Corruption (ETS 173)

- United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime and the Protocols Thereto

- United Nations Convention Against Corruption (UNCAC)

Domestic legal anti-corruption framework

Domestic anti-corruption legislation in North Macedonia includes:

- law on the prevention of corruption and conflict of interest

- criminal procedure code

- criminal code

- law on free access to public information

- law on whistleblower protection

- law on the environment

In the 2020 GRECO report on corruption prevention with respect to the members of parliament, judges and prosecutors, it was noted that North Macedonia satisfactorily dealt with nine out of nineteen recommendations of the fourth round evaluation report. The report recognised efforts to revise the legislative frameworks (GRECO 2020: 14-15). The introduction of rules guiding the acceptance of gifts, hospitality and other advantages for judges and lay judges has been welcomed by GRECO (2020: 15). There are still, however, certain gaps that need to be addressed. For example, as mentioned in previous sections, the inconsistency of the rules on conduct for prosecutors requires further attention.

Institutional framework

The institutional framework relevant for anti-corruption encompasses:

- the State Commission for Prevention of Corruption (DKSK), which is the key specialised anti-corruption institution, although its main focus is on prevention and oversight (Bliznakovski 2021)

- the Sector for Organised Crime and Corruption, a department under the Sector for Internal Control and Professional Standards, Ministry of Interior

- Public Prosecutor's Office of the Republic of North Macedonia

- Deputy Prime Minister for the fight against Corruption, Sustainable Development, and Human Resources (see Marušić 2020b).

Other stakeholders

Other important stakeholders include the media and civil society organisations.

Media

As in other Western Balkan countries, politicisation of the media is an important challenge in North Macedonia. Following the change in power after the elections in 2016, the partisan and state influence on media was relaxed, but there is still a widespread perception that the media is under political influence (Bliznakovski 2021; Balkan Barometer 2020).

Changes in legislation in 2019 and 2020, introduced the possibility for political parties to use state funding to pay for advertisements, which disproportionally benefited the three largest political parties (BTI 2020; Bliznakovski 2021). These changes were criticised by the media as they potentially open the space for jeopardising editorial independence by directing state funds towards friendly media outlets (Bliznakovski 2021). In the context of economic crises exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic, these regulations may facilitate capture of media by partisan interests or business actors (A Balkan Free Media Initiative Report 2021: 41).

Politically connected owners pose one of the key obstacles to independent media in North Macedonia. A recent report by (Balkan Free Media Initiative Report 2021: 47-49) provides examples of several TV stations with political connections.

Civil society

North Macedonia has a vibrant civil society, with the general environment for civic action improving in recent years (Bliznakovski 2021). After the change in power in 2017, civil society organisations' experts reportedly became more involved in the work of state institutions (BTI 2020).

Some of the most important civil society organisations relevant for anti-corruption are:

- Transparency International Macedonia, which is the local Transparency International chapter, working on anti-corruption topics relevant to the country

- Institute for Democracy “Societas Civiis” – Skopje

- the Macedonian Center for International Cooperation

- A country with underdeveloped institutions is characterised either by missing a number of relevant laws and regulations or by the enforcement of laws and regulations in a selective manner (see Schoenman 2014; Resimić 2021).

- Lay judges are non-professional officers of the court who sit alongside professional judges in some civil law jurisdictions. Their role is comparable to that of magistrates in common law countries.

- Balkans includes here Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Kosovo, Montenegro, North Macedonia, and Serbia (Csaky 2020: 25).

- From 2019, this regulation sets the conditions for the production of electricity from renewables (Zúñiga 2020: 17).