Introduction

“Multistakeholder partnerships (MSPs) involve organisations from different societal sectors working together, sharing risks and combining their unique resources and competencies in ways that can generate and maximise value towards shared partnership and individual partner objectives.”9a89bac5bb26

Accordingly, the idea behind MSPs is to rely on different actors’ expertise and their willingness to coordinate their action to solve collective problems. For example, stakeholders engaged within MSPs can: encourage a government to adopt standards on integrity; promote business regulation; and/or facilitate the adoption of a norm around integrity.

MSPs emerged in the 1980s, engaging on issues such as anti-corruption, the environment, and human rights. The scope and dimension of an MSP can vary. Some MSPs act within a specific sector and country, whereas others operate across national borders. MSPs generate interest from the literature to understand better those “non-hierarchical modes of coordination and the involvement of non-state actors in the formulation and implementation of public policies”.8ca39178fd16

This research examines how MSPs are managed and use their resources to promote integrity, with an aim to address corruption. It focuses on the governance of MSPs, their ways of working, and their capacity to deliver. Three MSPs are under scrutiny: the Infrastructure Transparency Initiative (CoST); the Maritime Anti-Corruption Network (MACN); and the Partnership Against Corruption Initiative (PACI).

The aim of the research is to understand the effectiveness of the different structures in achieving outcomes. Are these MSPs more than the sum of their parts? How do they contribute to the promotion of integrity and curbing corruption?

This paper is based on a critical assessment of the academic and public policy literature on MSPs, an in-depth investigation of three case studies (CoST, MACN, and PACI), and 16 semi-structured interviews with members of the three networks and prominent academics in global governance.

Theoretical background

A. The Governance Triangle

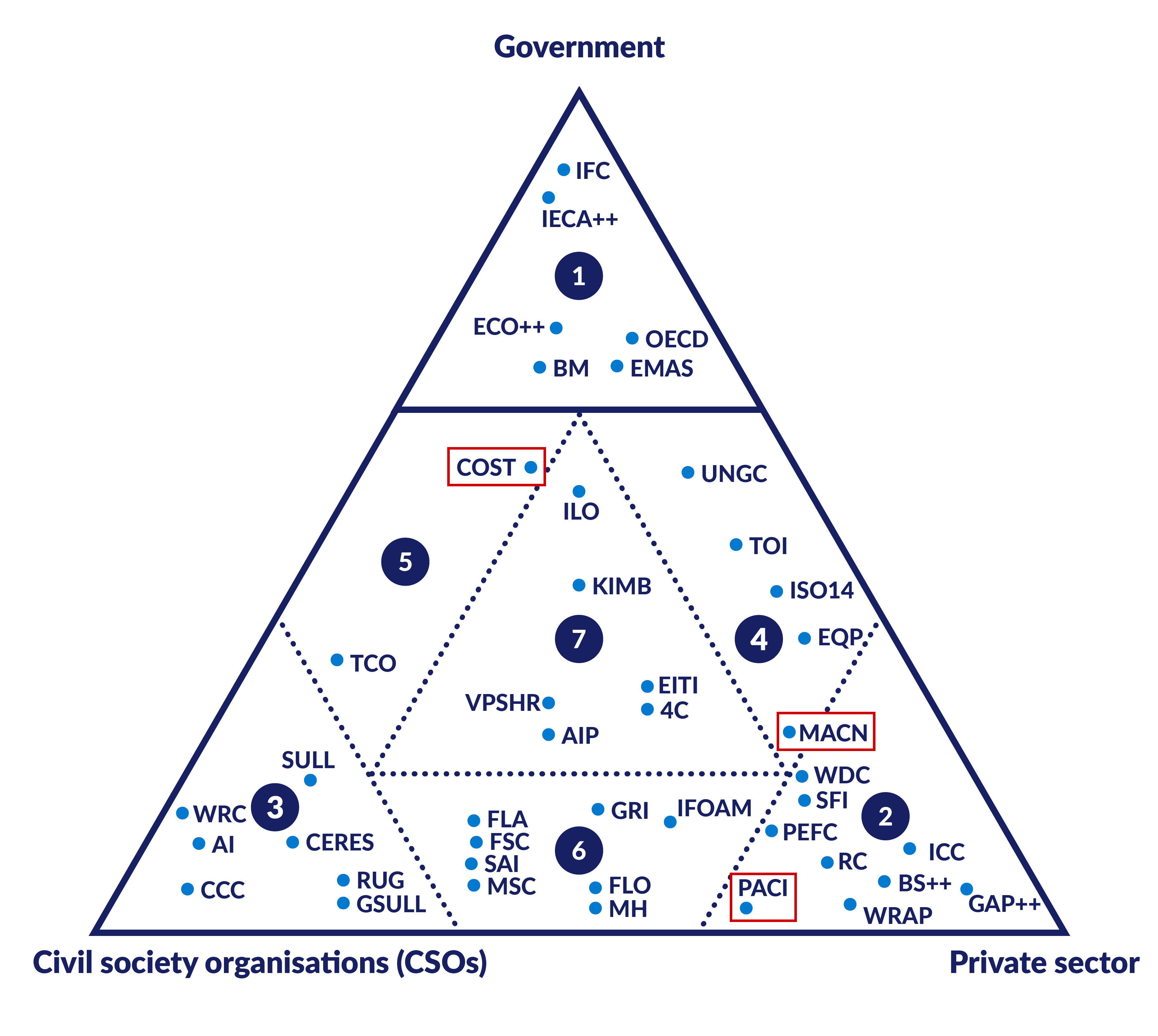

We used Abbott and Snidal’s58c8359c0de6 ‘Governance Triangle’ to help visualise MSPs’ governance structures and make a case selection. The seven zones of the triangle represent different possible combinations of stakeholder participation, between government, the private sector, and civil society organisations (CSOs).0ef91a2495d4 Following Abbott and Snidal’s definition, the governance shares depend in part on formal rules and tacit operating norms. For example, if a private company engages CSOs to monitor compliance, the arrangement would be placed between the private sector and CSO vertices.

Figure 1: The Governance Triangle, adapted from Abbott and Snidal (2009)

Each MSP’s positioning within the Governance Triangle is based on an analysis of the formal agreement and tacit operating norms, by examining the indicators that make up the ANIME analytical framework (explained below). As Abbott and Snidal outline, such measurements are only impressionistic and should not be over-interpreted. CoST, MACN, and PACI’s positioning within the Governance Triangle is based on our own estimation, as below:

CoST: government: 60%; private sector: 15%; CSO: 25%.

MACN: government: 15%; private sector: 60%; CSO: 25%

PACI: government: 10%; private sector: 70%; CSO: 20%

As illustrated in the Governance Triangle, for the purposes of this research, we did not select cases that were: 100% government-led (zone 1); 100% CSO-led (zone 3); or ‘perfect’ examples of equal distribution (zone 7). On the contrary, the research looked at MSPs with an unequal balance of power. The aim was to assess their efficiency and capacity to deliver, and to observe different stakeholders’ capacity to combine resources and competencies, and to bargain power.

We chose the Infrastructure Transparency Initiative (CoST), the Maritime Anti-Corruption Network (MACN), and the Partnership Against Corruption Initiative (PACI) of the World Economic Forum because of their different combinations of stakeholders. One MSP was led by the government (CoST), with the other two being different business-led initiatives (MACN and PACI). What is more, we wanted to observe different governance structures: two MSPs had a more vertical structure, with one dominant stakeholder (the government for CoST and businesses for PACI); while one MSP had a more horizontal structure, where stakeholders enjoyed more equal power sharing (MACN). Furthermore, we introduced a criterion of sectoral and non-sectoral variation. This centred around the fact of MACN and CoST being sector-specific partnerships (the maritime and infrastructure sectors, respectively) while PACI is not connected to any one specific sector.

B. The analytical framework

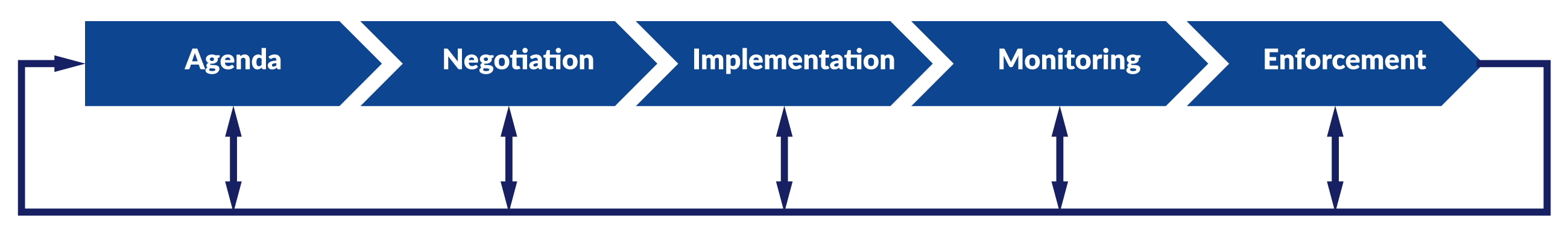

As acknowledged by Rascheed91440af669 or Menaschy,5fc73a8d36cc MSPs form because it is unlikely for any single actor to have sufficient skills and resources to solve a collective action problem. For example, a CSO might have the necessary bargaining power, but not enough material resources for enforcement. Yet, measuring the success of MSPs in countering corruption or promoting integrity is complex, as there are many variables that can influence outcomes. We therefore proposed to assess the different cases by not only looking at outputs, but also inputs, examining MSPs’ governance, ways of working, and outcomes. In particular, a systematic review would be achieved by looking at a set of indicators called the ‘ANIME framework’:9a96e0812a32 agenda setting, negotiation of standards, implementation, monitoring, and enforcement.

Figure 2: The ANIME analytical framework

(Abbott and Snidal, 2009)

Using this analysis, we could then assess different competencies for each MSP: independence, representativeness, expertise, and operational capacity.

We move on with the analysis of the three case studies: CoST, MACN, and PACI. For each case study, we provide a brief description of the MSP and its governance structure. Then each case study will be assessed according to the ANIME framework: agenda setting, negotiation of standards, implementation, monitoring, and enforcement. Conclusions are given for each case study and as a whole.

CoST (Infrastructure Transparency Initiative)

With more than 38,000 projects disclosed and a budget of 2 million pounds (by 2019),6c9cf87ee092 CoST is one of the leading global initiatives for transparency and accountability in public infrastructure projects. CoST currently has 19 programmes on four continents, mainly in Central America and Africa.

The main way that the initiative promotes integrity is through the “disclosure, validation and interpretation of data from infrastructure projects”. CoST’s goal is to tackle “mismanagement, inefficiency, corruption and the risks posed to the public from poor quality infrastructure”. All CoST initiatives are bound by the same principles: disclosure, assurance, multistakeholder working, and social accountability.

CoST’s governance structure

At the international level, the Board of Directors has a multistakeholder composition, with representatives from government, the private sector, and civil society organisations. The board guides new members’ admission and fundraising; it also brings support to national-level programmes.

The CoST Secretariat is hosted by UK non-governmental organisation (NGO) Engineers Against Poverty. Each national programme has its own secretariat. However, the CoST Secretariat has a general coordinating role for funding, facilitation, and technical assistance. It also checks for transparency in government procurement data, using the CoST standard. The private sector participates in the CoST Secretariat through the International Federation of Consulting Engineers.

CoST contains a specific element that other MSP do not have: a clear governance board for all national-level CoST initiatives, with formal representatives for the government, the private sector, and civil society organisations. These CoST governance boards are called multistakeholder groups (MSG). The government plays a key role in enhancing infrastructure transparency. Typical ministries involved in CoST include ministries of finance, public works, or infrastructure. The private sector is involved in CoST MSGs through chambers of construction, institutions of engineers, and business associations, contributing with technical expertise. Civil society is also well represented. For example, seven Transparency International chapters on integrity are part of CoST programmes at the national or subnational levels. Integrity Watch is part of the CoST programme in Afghanistan and the Africa Freedom of Information Centre (AFIC) in Uganda.

Analysis

Agenda setting

By institutional design, CoST’s MSPs have an advantage in the strong participation of the government in the agenda-setting process. The chair of the MSG is given to a government representative, and it is his or her responsibility to define the agenda. For example, the chair of CoST Thailand’s MSG is the Permanent Secretary of Finance. With the help of the secretariat, the Permanent Secretary of Finance proposes an agenda to the members and the agenda is agreed in a collaborative way. However, this reliance on government for agenda setting can also be problematic when political will declines, as this impacts the entire process.

Another challenge concerns the capacity for other stakeholders to influence the agenda. According to interviews with CoST Thailand, this challenge was modified thanks to the secretariat. This ensured free discussion among members, with the possibility to ask questions if projects were ‘dropped’ or not justified by the criteria. Another way to improve this process was by providing agenda items before the discussion took place, so that members had plenty of time to prepare.

Meanwhile, private sector representatives were concerned about the implications for their business if they participated in such an initiative (would they win contracts?). Moreover, in some contexts it was difficult for civil society to find a way to maximise the limited space for civil discourse. These issues were found to impact private companies and civil society’s capacity to influence agenda setting.

Negotiation among stakeholders

The process to start a new CoST programme sheds light on the inner workings of the group. It also shows how coordination among stakeholders takes place at the international level. The application is initiated by a senior government minister. Essentially, this buy-in from a senior government member is key for the initiative to be successful. An application comes to the secretariat, which commits the government to use CoST’s features.

CoST subsequently asks for letters of support from the private sector and civil society. The application is then reviewed, CoST assesses the government’s action plans, and ultimately this goes to the board for approval. After this, the secretariat makes its recommendation to the board. The government is then approved as a member or an affiliate (which represents a ‘light touch’ relationship and potentially a ‘gateway’ to membership). The international secretariat is crucially important throughout the process: it knows who and how to talk to the government, understands how to run a local MSG, and it is not under local pressure.

At the national level, coordination principally takes place through the MSG, with support from the local secretariat. The local secretariat is the host agency, with an independent legal status and its own financial and administrative management (for more details, see CoST guidance note). The MSG’s effectiveness depends on the quality of the local secretariat and the willingness of the MSG members to actively lead and participate in the programme.

Some MSGs are more influential than others. Those that tend to be more influential include senior individuals, especially government officials who have access to decision makers. MSG members are involved on a voluntary basis, although it is often part of their job to represent their respective institutions. Thus, local secretariats must be empowered to build those relationships on behalf of the MSG.

Stakeholders’ capacity for negotiation is related to their constituency, with a two-level game negotiation. This means that stakeholders represent their sector and commit to certain objectives within the CoST MSG, while at the same time liaising with their constituency to find support and to implement changes. Accordingly, CoST stakeholders need to support each other to shape the infrastructure sector.

However, interviewees from the private sector and civil society highlighted difficulties in raising concerns within MSGs, with the risk of being singled out or creating ‘embarrassment’. Thus, it was unclear how much support stakeholders got from each other and how divergent interests were managed. Moreover, it was unclear how much bargaining power CoST members enjoyed within their constituency.

“What needs to improve is the MSG members’ engagement with the constituents they represent. They need to ensure, for example, that the broader construction industry is aware of CoST, what it is trying to achieve for the sector, and when appropriate, obtain their views on specific issues.”c56dc52464ac In particular, civil society often lacked the capacity to use the disclosed data and hold government officials accountable.

Finally, the Covid-19 pandemic has brought many challenges, including with fundraising. This challenge may have an impact on CoST initiatives, as a heavier reliance on government budgets is likely to undermine the balance of power among stakeholders within the MSGs.

Implementation

CoST typically obliges procuring entities to disclose 40 data points or ‘items’, as outlined in CoST standards – the CoST Infrastructure Data Standard (CoST IDS) and the Open Contracting for Infrastructure Data Standard (OC4IDS). These data points include both project and contract data, and cover key stages of the infrastructure project cycle. This method provides a way to curb lack of transparency in the infrastructure sector, as “private sector companies will only disclose data if they are responsible for a public–private partnership investment”.a5fb68dd8029

Taking CoST Thailand as an example, the strength of this MSG comes from the legal power of the Ministry of Finance to mandate procurement entities to be managed under the CoST programme. Every year, the General Auditor’s Department and the secretariat make a shortlist of projects to be put under the CoST programme.

Civil society organisations help to publicise key issues identified in the CoST's reports, putting them into the public domain. This action includes amplifying issues regarding the environmental and social impact of projects in CoST, value for money, and anti-corruption. Examples of civil society work in CoST include training programmes in Afghanistan; work with the School of Social Accountability in Honduras; and a media collaboration in Honduras to investigate fraud in public works.

Finally, an advantage of CoST’s activities comes because of support from external players, such as the World Bank. Participation in CoST is not dictated by international organisations, neither is participation in CoST part of World Bank conditions attached to funding (‘conditionality’). However, the World Bank has had discussions with Honduras, Guatemala, and Ukraine, stressing that CoST would bring value to their infrastructure sectors.

Monitoring

To accredit results, MSGs rely on assurance teams (volunteer engineers) to monitor the information entered onto the CoST database attached to the national initiative. They do this monthly, evaluating the completeness of information that is required from procuring entities. The teams undertake random visits to construction sites and seek input from nearby communities. MSGs also rely on social monitoring, but the efficiency of this is less clear; to what degree civil society and ordinary citizens (without a technical background or data-related competencies) can draw conclusions on the data remains a question.

When all stakeholders from the local MSG agree, the findings are sent to CoST International. An annual MSG meeting follows the results of the chosen projects, where it approves the annual report and new projects. This meeting revisits the current regulation and amends it if needed.

CoST relies on a sophisticated process to ensure internal transparency. For example, CoST has an open information policy that includes publishing the minutes of CoST Board meetings.

CoST monitors many different aspects to assess the value its outcomes. According to CoST’s business plan for 2020–2025, some of the successes that CoST has brought about include: cost savings of more than US$360 million by the Thai Ministry of Finance; savings of US$8.3 million in the Afghanistan Ministry of Transport; and the closure of a corrupt institution in the Honduran roads sector. Another example has been the creation of a CoST open data portal in Ukraine, to ensure more transparency on public tenders in the infrastructure sector.

CoST also uses the number of bidders as a proxy indicator for integrity and a direct outcome for stakeholders. The rationale is that the more competitive the bidding process, the greater the likelihood of integrity within the procurement process. This in turn will increase the propensity to save money and reduce time overruns. For example, CoST was introduced in local government projects in Thailand. Using benchmarking with conventional bidding, CoST claims that local government savings reached up to 18% of bid total amount, and even 24% when its Integrity Pact programme was implemented.1a5821dbf96a

Another important outcome for CoST is its capacity to modify regulations for the disclosure of information on public procurement, to ensure transparency and fair competition. For example, CoST is integrated into the Procurement Act in Thailand.

Enforcement

Vietnam, Philippines, Zambia, and Botswana have stopped being part of CoST, while Tanzania is in the process of becoming inactive. A whole process takes place, before discontinuation of membership due to a lack of performance. Warnings are subsequently made to the respective governments. If a programme gets flagged, the government has six months to show immediate progress. The process goes to two reviews and takes 12 months.

In terms of sanctions, the surprising fact is that there have been no reactions from other members of the partnership or others such as the media when a country has left CoST. Such reactions could be formal communications, a press release, statements etc. – given that such projects, involving billions of euros/dollars, are of public interest. Accordingly, in a vertical structure where the public entity is the dominant actor, failure to implement the initiative may not generate reactions from other entities that are part of the MSP. This emphasises the lack of accountability within this kind of configuration, despite such accountability being crucial to reaching expected outcomes.

Enforcement also depends on coordination between assurance teams, local committees, and procuring entities. No severe frauds have been reported in local MSGs, but sanctions are sometimes taken for non-compliance with transparency and information regulations.

Conclusions

CoST works with the government, civil society, and the private sector to disclose, validate, and use data from public infrastructure projects. This process may inhibit or deter corruption and lead to more integrity-based decisions. The use of such evidence may also hold stakeholders more accountable and improve outcomes from the infrastructure sector.

CoST can rely on strong expertise from the state and businesses, with the involvement of engineers who have the knowledge and ability to assess the data. The MSP is highly representative, as all actors (the public sector, private sector, and civil society) work together, ensuring effective operational capacity. The government has an enhanced role, as it initiates the partnership with CoST, participates in the entire process, and may also provide funding. In particular, initiatives relying on MSGs with high-level public officers are likely to be more effective.

However, reliance on government for the implementation of reforms is a challenge. When political will decreases, this hampers CoST’s capacity to implement changes, with the risk that CoST’s activities will be paralysed. The vertical governance structure may also negatively impact civil society and private sector support, as well as their capacity to raise concerns, hampering CoST’s operational capacity.

MACN (Maritime Anti-Corruption Network)

MACN is a private sector-led MSP to fight maritime corruption. MACN’s membership, which totals more than 160 members, is open to private companies that own or operate commercial vessels and companies in the maritime value chain. This includes those in the ship management sectors, port management, or shipping agencies.

The main way that MACN promotes integrity is by: “raising awareness of the challenges faced; implementing the MACN Anti-Corruption Principles and co-developing and sharing best practices; collaborating with governments, non-governmental organisations, international organisations and civil society to identify and mitigate the root causes of corruption; and creating a culture of integrity within the maritime community”.

MACN’s governance structure

MACN’s governance structure comprises a Steering Committee, elected by the 164 members of MACN. This Steering Committee oversees the activities of MACN, provides inputs, sets the agenda for annual meetings, admits new members, reviews the annual budget, and monitors budget performance. The seven members of the Steering Committee reflect the diversity of MACN members, considering factors such as industry segments, company size, and country of origin. The Steering Committee members are selected through member voting and sit for at least a one-year term. The MACN member vetting process is overseen by the Steering Committee.

The MACN Secretariat coordinates, with resources and knowledge sharing, all national and local work streams. It is responsible for advancing MACN’s strategic work plans, ensuring its governance and operations, and managing relations with internal and external stakeholders. The secretariat is hosted by BSR, a ‘global non-profit organisation’, which works with its network of more than 250 member companies.

The scope of work with key performance indicators (KPIs) per work stream is developed by the secretariat and is approved by MACN’s Steering Committee. Donor-funded projects are guided by KPIs set in already established monitoring and evaluation (M&E) plans and are not approved by the Steering Committee.

MACN as an organisation is governed by the private sector. However, each in-country collective action is implemented in partnership with a local organisation, such as an NGO, and involves MACN member companies or in-country business operators. The actual coordination with stakeholders involved in the collective action depends on the scope. A project working group is required for all initiatives, with a mix of members, business associations, civil society, and government.

MACN relies on a set of policy documents to define its governance process and the roles and responsibilities of all stakeholders: the MACN Operating Charter, the MACN Anti-Corruption Principles, and the MACN Anti-Trust Compliance Policy.

Analysis

Agenda setting

In MACN, member companies come together with stakeholders, including port and customs authorities, CSOs, and local governments, to understand the underlying causes of corruption in the maritime supply chain and design a course of action. Twice a year, MACN meets with all members, local partners, and other external stakeholders, including the government, to discuss current challenges, progress against work plans, and next steps. Once a year, MACN hosts a one-day collective action workshop, including all local partners and practitioners involved across MACN’s collective action projects. The purpose of the session is to enable cross-learning, coordinate actions globally, and invite external stakeholders to engage in projects.

Through surveys, feedback from members, and a wider consultation, MACN identifies issues it wishes to focus on. Once an issue has been identified, an elaborate scoping phase starts. Working groups for specific work streams and initiatives are established on an as-needed basis. These consist of member companies, eg, for piloting new tools and training materials, and for scoping out and implementing collective action initiatives in ports. Each Steering Committee member has a defined role to oversee specific work streams and ensure that they align with the overall agenda.

Priority countries, for collective action work, are decided by the Steering Committee. However, the committee relies heavily on incident data and feedback from the membership. Countries and ports targeted are those where MACN members experience severe and frequent integrity challenges and are willing to address them. MACN also targets countries and ports where the membership has sufficient commercial leverage in ports.

Feasibility is also important: MACN targets countries where there are opportunities to make a difference. It looks at the business and political climate, access to funding, using external data sources, as well as the presence of a trusted partner who can lead the initiatives in the country.

Negotiation among stakeholders

Negotiation takes place against a backdrop, whereby members assess what they get out of their participation and maximise their benefits. Such benefits include access to the knowledge resources generated by the information infrastructure that MACN has established. According to Hans Krause,855e6ec00624 “by participating in MACN collective action, [MACN members] have a greater impact in alleviating a fundamental bottleneck of trade and development than acting alone”. Thus, there is a large incentive for companies to stay engaged in the negotiation process.

According to the interviews, the collaboration at MACN seemed to work effectively. Bilateral conversations took place between the Steering Committee and individual members, and with the secretariat. Voting decisions occurred during meetings for formal decisions, such as for a change of operating charter, member dues, and Steering Committee elections. Each paying member had one vote. Accordingly, the negotiations took place only between private companies; civil society organisations and government were consulted, but not involved in strategic choices or decision-making.

Implementation

MACN appoints a commissioned company lead in all collective actions. This company is involved in setting the work plan, gives the industry perspective, and contributes with industry know-how. For example, for its collective action in Argentina, MACN commissioned a law company, Governance Latam, to conduct interviews to understand root causes of corruption and then to support public authorities to implement reforms. The local partner will lead the engagement with government and local business in the country, including recruitment, day-to-day project management and meetings, and will work relatively independently. Usually, MACN needs to spend some time training and building capacity in the local partner organisation. Moreover, it provides support during implementation activities.

The role of MACN’s Secretariat in collective actions is to act as a third-party convener, facilitating the creation of a broad coalition to define and implement. It is responsible for progressing with MACN’s strategic work plans, ensuring good governance, and managing MACN’s day-to-day work, including with its members, third parties, and funders. “We use our extensive international network to build support for the project among international stakeholders.”58230ecc1a96 For example, private companies that ship large volumes of goods through a port are solicited, as they have the commercial leverage necessary to influence other stakeholders. MACN works closely with local partners, embassies, industry associations, and MACN member private companies to reach out and access stakeholders. MACN projects must engage at the most senior level in government, to gain buy-in and maintain commitment at several levels.

Monitoring

MACN has a monitoring system in place. This is based on mandatory annual self-assessment by each member state. Members are compared against their peers in the segment (tanker, bulk, etc.) and areas where MACN sees gaps. For example, “In collective action ‘Say No’ campaign in Argentina, all participating private companies report their port calls, corrupt demands faced, and feedback on how bribery was resolved.”a13095706a58 Moreover, a new regulatory framework was implemented and corruption incidents decreased by 90%. Accordingly, this dialogue among peers is critical to ensure and to monitor implementation.

Results of monitoring are shared with the secretariat and members who are part of the initiatives, to monitor progress and share common challenges. “It is a way to understand for example which ship owners or agents are not following the new regulation. This is a very careful and delicate process. Private companies (members/non-members) who are not following the regulation are approached by MACN to discuss the challenges/ and offer membership to the MACN.”68cc61ccbb14

Of interest, MACN established an anonymous incident reporting system. By July 2021, MACN had collected more than 41,000 reports of corrupt demands globally, addressing corruption from both the public and private sectors. Yet, reporting is strictly anonymous and non-attributable, so it does not provide a way for MACN to know more about how network members respect anti-corruption laws and policies. An external review of these self-assessments emphasises low reporting requirements: “Monitoring and sanctions are problematic in the case of MACN. It is not clear how network members can police the behaviour of their competitors, to assess whether or not they pay bribes.”aa005f82835e

MACN also monitors progress on capability building, developing “shared methodologies, frameworks, training, and campaigns, helping each member company to strengthen its approach to tackling corruption”, such as compliance risk requirements, risk assessment, monitoring and internal controls, etc.

Finally, MACN monitors results for peer dialogues (eg, sharing best practices, addressing compliance issues in hot spot locations) and progress on collective actions (eg, a reduction in requests for facilitation payments in the Suez Canal; new regulations in Argentina and Nigeria).

Enforcement

In terms of enforcement for internal policy rules, MACN’s activities are overseen by the MACN Steering Committee, with active participation of the full MACN membership. There are clear member obligations, and suspension and termination of membership criteria, in the Operating Charter. The Steering Committee is responsible for overseeing and executing suspension and termination decisions (this requires a two-thirds majority). Yet, when MACN’s rules are violated by a member, the only available measure is the termination of membership.38e437e0a72f This lack of a scaled approach can be problematic for enforcement, as it is not solution-oriented; only risk avoidance is considered. It also emphasises the lack of monitoring for progress towards MACN principles.

According to David-Barrett, “the MACN is successful in attracting members because it once again provides a valuable reputational signal that allows companies that join to access selective benefits. This signal is read by potential clients that are themselves motivated by a desire to be part of an international club of ethical businesses.”

According to this argument, enforcement and compliance with anti-corruption laws and procedures are likely to improve thanks to this consortium of powerful players in the maritime industry, through peer pressure and the emulation of other stakeholders. Yet, the argument must be counterbalanced by the fact that monitoring is based on self-assessment and MACN members have little capacity to monitor their competitors and other MACN members.

Conclusions

The MACN Secretariat enjoys significant independence to define and implement its plans. MACN has implemented collective action initiatives, in partnership with the industry, governments, and civil society. This has proved to be an efficient way to reduce demands during port calls; to support businesses to say ‘no’ to corruption; and to improve governance frameworks in the port sector through regulatory reforms. Expertise is solid. MACN enjoys wide recognition and a solid reputation based on effectiveness. Yet, MACN is based on a community of private interests, with limited capacity to monitor and enforce anti-corruption policies among members.

MACN is a business-led initiative, with limited involvement of civil society and government within its governance structure, as well as for the agenda setting. However, civil society and government are involved in local groups during the implementation phase, facilitating ownership for local initiatives. While the private sector identifies problem areas and agrees to a common standard, enforcement cannot take place without the government’s collaboration. This collaboration on the ground ensures that both the private and public sectors are represented. It enhances MACN’s representativeness, and ensures effectiveness for its operational capacity.

PACI (Partnership Against Corruption Initiative)

The World Economic Forum’s PACI is a business-led initiative with approximately 90 signatories from different sectors across the globe. PACI is the largest business-led platform in the global anti-corruption arena, “building on the pillars of public–private cooperation, responsible leadership and technological advances”.1e22f0f331f9 PACI’s operations are financed through the World Economic Forum (WEF).

The main way that the partnership promotes anti-corruption is through its efforts to achieve meaningful and sustained dialogue via global, regional, and industry initiatives. PACI contributes to other anti-corruption initiatives and collaborates with governments, international organisations (such as the UN Office on Drugs and Crime), think tanks (eg, the Basel Institute on Governance), and CSOs (such as Transparency International).

The World Economic Forum’s PACI case study is different from the other cases, as there are no country-specific work streams.

PACI’s governance structure

PACI is a business-governed initiative. There is no government involved directly in PACI’s governance, but a collaboration with governments and CSOs in work streams. PACI consults, convenes, and implements activities with governments. When members of the World Economic Forum (WEF) propose a project, the WEF PACI team steps in to set up a steering committee, including members from the private and public sectors.

The PACI team is responsible for advancing PACI’s strategic work plans, ensuring its governance and operations, and managing relations with its internal and external stakeholders. There is no secretariat; operations are supported and financed by the World Economic Forum. PACI’s membership is composed of 90 private companies, all from different sectors, which have WEF membership.

The companies’ membership in PACI is achieved through participation in the PACI Vanguard. The Vanguard Board has a CSO and an academic representative on its Steering Board (2 of 11 members). There is no government representation within the PACI Vanguard, only consultations. The vanguard’s purpose is to find solutions to collective action problems in anti-corruption and integrity, using the WEF’s wide network base. The PACI Vanguard relies on quarterly calls and biannual meetings with the broader PACI group, alternating between North America and Europe.

For on-board new signatories to PACI, private companies sign the PACI principles and a letter of disclosure. Essentially, the members commit that there is no pending corruption-related litigation for the private company at the time that they join PACI. The application is then reviewed internally (by the PACI team, compliance team, the Governing Committee, and the Vanguard Board). Following this due diligence, the PACI team decides whether it will accept the application of the new signatory. The PACI team can also decide to discontinue a member if its principles are no longer being implemented by the company.

Analysis

Agenda setting

The main challenge that PACI needs to deal with is broad participation by private companies operating in different sectors. This means that PACI members are diverse and come into the group with a wide set of priorities. It is thus difficult to prioritise what the group wants to focus on.

While agenda setting is presented as consensual, some members are more influential than others in the choice of projects. “Members and partners of the World Economic Forum benefit from a tailored engagement based on their company’s strategy. The deeper a company’s engagement, the greater is its ability to shape the Forum agenda.”f3d7c9b3ccc9

According to interviews with PACI members, the agenda for PACI was mostly set by CSOs, thanks to their participation in the different bodies of PACI. In particular, these included the Global Future Council on Transparency and Anti-corruption. This independent group of experts is curated by the PACI team and co-chaired by Transparency International and the Woodrow Wilson International Centre, to define the trends and focus of PACI activities.

As the public sector is not represented within PACI’s Governance Board, the private sector and CSOs set the agenda and define operations.

Negotiation among stakeholders

The PACI group is based on trust, exchange, and common interests among its members. “Open discussions take place before, during, and after every meeting. Consensus-based decisions are made during the meeting.”7899e7d7c206 Moreover, the power of the World Economic Forum’s brand means participation in PACI is desirable, even if participants contribute with their time, pro bono. Furthermore, PACI members support PACI initiatives, as these can be beneficial to their business.

For strategic decisions, the PACI team presents its findings to PACI signatories during their annual meeting in Davos. Consensus on strategic objectives is reached, but with difficulty given the diversity of actors involved in different sectors. PACI is currently exploring ways for improvement – for example, through surveys to identify commonalities among members.

The PACI team is the orchestrator of the collaboration between stakeholders. It ensures a feedback loop for inputs,441275253309 which comes out of the Global Future Council on Transparency and Anti-corruption and other WEF bodies. Accordingly, civil society enjoys some bargain power during meetings, thanks to its participation in the Vanguard Board, the Global Future Council on Transparency and Anti-corruption, PACI meetings, and WEF annual meetings. However, according to interviews, the agenda and negotiation could be more inclusive and civil society did not have the capacity to take the lead.

Government representatives are present during WEF annual meetings and PACI events to shape ideas, but do not have power to define PACI strategic goals.

Implementation

Once a topic is validated by PACI signatories, the project is coordinated by a PACI team member. This entity sets up a steering committee, which includes members from the private and public sectors. Implementation plans vary according to PACI’s different work streams, on ‘Tech for Integrity’, beneficial ownership, enlisting gatekeepers in the fight against corruption, and compliance in terms of crisis. For example, for the topic of beneficial ownership, a multistakeholder advisory group, involving civil society, the private sector, and government, has been set up to implement short-term pilots to verify beneficial ownership information.

According to the interviews, PACI did not aspire to enforce any decisions or any change in terms of how the government or the private sector worked vis-à-vis integrity and anti-corruption. There was no pressure to adopt any robust accountability assessments, use performance indicators, or engage in a quantitatively measured exercise to quantify its impact. PACI could, nonetheless, become a platform for ideas to be adopted by actors within sectors.

All resources that are devoted to the PACI initiative are World Economic Forum owned and managed. A small PACI team and the WEF’s broad engagement on a multitude of issues mean that there might be pressure on how much time, staff, and funds the World Economic Forum can devote to the initiative.

Monitoring

PACI is accountable to the World Economic Forum, to its partners and constituents, and to the two co-chairs of PACI and the Vanguard Board. Reporting sessions take place during the Biannual PACI Community Meeting. In line with PACI principles, the PACI team operates according to its concept of disclosure, discussing any concerns with signatory companies. Member companies are also asked to provide feedback, for example, through surveys, to assess the relevance of PACI’s work streams and how useful they are for signatories.

PACI monitors its participation and contribution to international forums and anti-corruption initiatives. Examples include taking a lead role in the B20 Taskforce on Integrity or implementing the Agenda for Business Integrity, a four-pillar framework to support collective action, and leverage technologies, knowledge, and commitment towards integrity. PACI believes that it encourages a change in thinking, as it puts forward new concepts in the field and promotes the values of anti-corruption and integrity.

Given the variety of projects, there is no formal monitoring system. “Improvements in terms of integrity are difficult to measure, but we can see these by the internal policies of private companies, the way their leadership addresses and prioritises anti-corruption at the board level, and lastly if they understand ethics and integrity beyond compliance.“46d5665a039e Accordingly, PACI’s monitoring does not rely on clear indicators and measures for change.

Enforcement

PACI’s principles are not legally binding. Rather, they are used for open discussions with signatories in cases of concern or infringement. The PACI team can decide to suspend a member in cases where they are no longer enforcing PACI principles. This is decided by a governing committee, in consultation with the World Economic Forum.

It is not PACI’s aspiration to hold governments accountable for specific integrity measures (as is the case with CoST) or to push governments to change legislation (as is the case with MACN).

PACI contributes to non-legally binding recommendations, such as the ones from the B20 Taskforce on Integrity. PACI also contributes and pushes for reflection and public policy research on anti-corruption through its different work streams (such as the Strategic Intelligence capability, handbooks, WEF reports, etc.).

Conclusions

PACI is led mainly by the private sector, with no formal representation from government. PACI consults, convenes, and implements activities with government, but governments are not represented within PACI’s governance structure. Participation within PACI stems mostly from business and civil society. In particular, civil society is part of PACI’s governance structure, as well as its projects, influencing its agenda and outputs. Overall, the level of representativeness is low.

PACI enjoys resources and the managerial ability to achieve its goal to be “the leading business voice on anti-corruption and transparency” and “to address industry, regional, country or global issues tied to anti-corruption and compliance”.7dda528f960e Its operational capacity is high, considering its logistical capacity to organise or to participate into international forums on integrity and anti-corruption issues.

Yet, there is no monitoring and, therefore, no proof of its capacity to influence business behaviour and address anti-corruption issues. Enforcement is applied only through the expulsion of members where there is proof they have litigation pending.

Finally, PACI deals with a wide variety of issues, but without making the best use of expertise on specific topics across time or relying on external skills and knowledge for its initiatives. Accordingly, its internal level of expertise is low.

Multistakeholder partnerships are greater than the sum of their parts

Each MSP was able to deliver outcomes when addressing collective action problems that individual stakeholders could not deal with alone. CoST relies on expertise from the private sector and the government’s capacity to enforce transparency in the infrastructure sector; for example, by ensuring transparency for public tenders in Ukraine via the infrastructure open data portal. MACN has implemented and enforced collective actions that have contributed to fewer incidents of corruption and have resolved MACN members’ grievances; for example, by using the new regulatory framework in Argentina, which decreased corruption incidents by 90%. As a result of the involvement and coordination between civil society and the private sector within PACI, new ideas can now emerge in international events, such as the Agenda for Business Integrity.

The different governance structures rely on different mechanisms to enhance integrity, all of which have both qualities and deficiencies. CoST’s two-level game structure is likely to be effective, as stakeholders are engaged towards common objectives within CoST and can support each other in terms of implementation for their own particular constituencies. Moreover, the significant involvement of government is a way to ensure support and to build on public operational capacity. However, the risk of abandonment is high in this case, while the dominance of the public sector could discourage other stakeholders’ support. MACN’s capacity is based mainly on the commitment of the biggest players to level up standards and report breaches. However, reporting is non-attributable, while members have neither the incentive nor capacity to monitor their peers. PACI, meanwhile, builds on WEF’s reputation to raise international attention on integrity issues, but hasn’t the influence necessary to promote changes.

Accordingly, enforcement within MSPs remains an issue, for those with both horizontal and vertical power structures. Partnerships are based on members’ voluntary commitment and non-legally binding agreements. Therefore, members may lack the capacity or willingness to act where principles are breached and there is no capacity for enforcement. This is true in the case of CoST, whose high reliance on the public sector likely lowers its enforcement capacity. As a result, many CoST initiatives are on standby or have just ceased to operate, without generating sanctions or reactions from CoST members. This is also true for MACN, whose members enjoy the benefits to their reputation that the partnership brings. Yet this maybe meaningless given that it does not scrutinise its members’ commitment towards the partnership’s principles. This shows the limit of multistakeholder partnerships in terms of their capacity for checks and balances, as they are based on trust and mutual interests and such scrutiny would be detrimental to the partnership.

Despite this, the different networks could aspire to adopt best practices from outside their own networks. MACN could share its risk assessment and incident reporting mechanism; CoST could share its skills around how to structure a multistakeholder group on the ground; and PACI could contribute its know-how on organising international forums on integrity and anti-corruption issues.

Finally, this study shows that solutions to curb corruption and enhance integrity can emanate from both the public and the private sectors; it is their collaboration which enhances integrity. MACN is led by private companies, but it is the participation of government and civil society which determines its capacity to deliver. CoST is led by a non-profit organisation, but it is the coordination among civil society, the public sector, and the private sector which ensures the implementation of transparency measures. By contrast, PACI‘s lack of government representativeness and its cross-sectoral approach generate difficulties in defining a strategic work plan and a track record to ensure impact.

Recommendations to development agencies and practitioners

- Development agencies and public sector leaders could benefit from a structured dialogue on how they can jointly increase integrity and address corruption through MSPs. This could be through changes in government legislation, norm setting in a particular sector, or by promoting new ideas on integrity.

- When considering support to MSPs, development agencies could draw on the ANIME framework for a better assessment of their potential impact.

- Development practitioners are encouraged to engage with and utilise national and local MSP initiatives, to increase integrity and better address corruption in their sectoral work.

- The Partnering Initiative, 2016.

- Börzel and Risse, 2010, p. 113.

- Abbott and Snidal, 2009.

- We generally use the term ‘civil society organisations’, but we specify when we refer specifically to non-governmental organisations.

- Rasche, 2012.

- Menashy, 2017.

- Abbott and Snidal, 2009

- CoST International, 2021.

- Interview with a member of the CoST Secretariat, December 2020.

- Interview with a member of the CoST Secretariat, December 2020.

- Interview with member of CoST Thailand, December 2020.

- 2015, p. 23.

- Interview with a member of the MACN Secretariat, December 2020.

- Interview with a member of the MACN Secretariat, December 2020.

- Interview with a member of the MACN Secretariat, December 2020.

- David-Barrett, 2019, p. 12

- Van Schoor and Luetge, 2016, p. 10.

- WEF, no date.

- Interview with the PACI team, November 2020.

- Interview with the PACI team, December 2020.

- This means the PACI team ensures that outputs (results, discussion, findings, publications) from the Global Future Council on Transparency and Anti-corruption and other WEF bodies reach WEF stakeholders (private companies), so CSOs can have an impact.

- Interview with the PACI team, November 2020.

- Partnering Against Corruption Initiative website.