Query

Please provide a summary of the recent debates and developments on the topic of settlements of foreign corruption cases and the management of their proceeds.

Introduction

Background

In a typical case of foreign bribery, a company from one country engages in the bribery of foreign public officials to win a business advantage in another (Transparency International n.d.) by, for example, securing exclusive rights to exploit natural resources or securing a public procurement contract.

Such cases can be investigated and prosecuted on the basis of foreign bribery legislation by the judicial authorities of an ‘enforcing country’, which is often (but not exclusively) the state where the company is domiciled, or the offending individual is a citizen. These authorities have recourse to initiating criminal, civil or administrative proceedings against offenders. While custodial sentences can and have been imposed for individuals, it is much more common that sanctions are monetary in nature, including in the form of a fine and the payment of damages ordered when proceedings have run their course or alternatively as part of a settlement agreement.

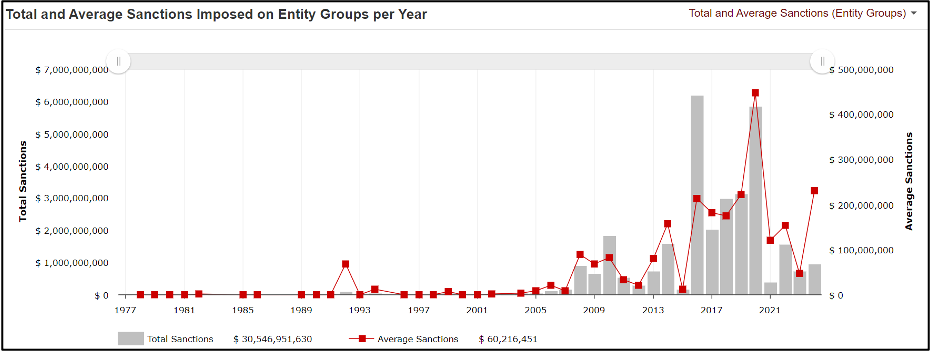

The volume of monetary sanctions imposed under foreign bribery frameworks – both in standalone cases and cumulatively speaking – are significant. As displayed in Figure 1, between the total sanctions imposed on entity groups – that is, excluding individual persons – under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act proceedings between 1977-2024 amounts to over US$30 billion, while the average sanction imposed was around US$60 million.

Figure 1: Total and average sanctions imposed on entity groups under FCPA proceedings (1977-2024)

Source: Stanford Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Clearinghouse 2024

Monetary sanctions may be regarded as fulfilling different purposes. One is to deter repeat and foreign bribery through exacting a financial cost on perpetrators. Another is to address the harms which have arisen because of the bribery. Olaya Garcia (2020a) argues this conveys an important anti-corruption message, namely that what was damaged by bribery is worth repairing. These harms are often severe and diffuse in nature (Transparency International 2020a: 21) given that numerous different actors can be affected by foreign bribery, including:

- Company shareholders: who may suffer significant financial losses as a result of actions undertaken by the company directors or employees without their knowledge (Messick 2016).

- Competitors: other companies that cannot fairly compete due to the advantage gained by, for example, losing out on a compromised procurement process (Transparency International 2020a: 21).

- The ‘foreign country’ where the bribery took place: this is typically the country where the bribed public official is active. The unfair advantage secured by the company can result in this country losing public funds and tax revenue, having to pay higher prices and obtaining lower quality services, among other things(Roht-Arriaza 2023; Transparency International 2020a: 21).

- Members of the public: the harm of foreign bribery can have downstream effects, leading to higher prices for consumers, diminishing the quality of the public services citizens receive or even cause irreparable damage to the environment they live in (Transparency International 2020a: 21). In some cases, an entire population may be harmed by foreign bribery, while in others the harm may be limited to an identifiable person or group. In the literature, the term ‘overseas victims’ is used to distinguish those victims residing in the ‘foreign country’ (Walker 2024). When victims are not represented by the state, they are sometimes referred to as ‘non-state victims’.

However, despite there being a wide range of actors that are negatively affected by foreign bribery, Hickey (2021a) describes that:

‘[T]he money extracted through foreign bribery enforcement is typically retained by the treasury of the enforcing nation. These proceeds, extracted almost exclusively through criminal settlement agreements made between prosecutors and corporations, are rarely used to remedy, or to attempt to remedy, the harm caused by corruption.’

A 2013 report from the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR) titled Left out of the Bargainanalysed 395 foreign bribery settlements agreed between 1999 and mid-2012. These resulted in a total of US$6.9 billion in monetary sanctions, but StAR estimated that only US$197 million, or 3.3 % of this total had been returned to foreign countries whose public officials were bribed (Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative 2013). In 2024, the NGO Spotlight on Corruption concluded that this pattern had not dramatically changed since (Roussel et al. 2024: 5).

This Helpdesk Answer takes this state of affairs as its point of departure and aims to better understand the bottlenecks blocking a higher level of monetary sanctions from reaching foreign countries and overseas victims.

A robust strand of academic literature, policy debates and jurisprudence has developed around this topic. This answer first describes the various relevant legal processes and terms and then provides an overview of national and international foreign bribery legislation, as well as other relevant frameworks. Secondly, a summary of four recent and relatively high-profile cases is given for illustrative purposes, documenting how different outcomes regarding monetary sanctions were reached. This is followed by a literature review of the main points of debate on the topic and, indeed, what typically constitutes the bottlenecks. The final section explores the ways enhanced cooperation can overcome such bottlenecks, based on existent practice and potential interventions.

Scope

The scope of this answer is limited in several ways. First, the question of how to allocate monetary sanctions is not limited to cases of foreign bribery; for example, the question of reparations has arisen in a settlement over a domestic bribery case from Brazil (Olaya Garcia 2020b). Nevertheless, this answer focuses on exclusively foreign bribery, primarily because this raises unique jurisdictional and transnational aspects which distinguishes it from domestic bribery.

Second, while, as noted above, a range of actors can potentially stake a claim to monetary sanctions includes company shareholders and competitors, this paper focuses on foreign countries and overseas victims.

Third, monetary sanctions may be available under foreign bribery legislative frameworks for a range of offences, beyond the offering or attempt to offer a bribe; for example, failure to carry out adequate due diligence or the failure to ‘prevent foreign bribery’ (McGregor and Yeldizian 2023). This paper does not preclude consideration of the allocation of monetary sanctions collected for such offences; however, it should be noted that the relevant literature tends to focus on cases where the offence was bribery.

Legal and policy frameworks

Avenues towards monetary sanctions

As many terms associated with this answer’s topic are often used interchangeably, this section aims to clarify the different ways in which monetary sanctions are imposed, as well as how compensation to foreign countries and overseas victims can be granted.

Monetary sanctions are handed down against foreign bribery offenders as part of criminal, civil or administrative proceedings (UNODC 2019: 3). Such proceedings may conclude with a full judicial trial, but more typically this occurs through a non-trial resolution, commonly known as a ‘negotiated settlement’ or just a ‘settlement’. Søreide and Makinwa (2018:14) define this as any resolution that is an alternative to a full trial or that mitigates a full penalty in respect of a foreign bribery allegation. A notable example is a deferred prosecution agreement (DFA) under which enforcement agencies agree not to prosecute a foreign bribery offender on the condition of their fulfilment of the agreement’s elements, such as the payment of a fine or cooperation in the identification of wrongdoers (Yockey 2012; Campbell 2021). While they generally require a final stage of judicial approval, the terms of such agreements are typically negotiated by the foreign bribery enforcement body and the offender, often out of public view.

These kinds of resolutions constitute the majority of foreign bribery cases; the OECD (2019: 13) estimated that between 1999 and 2019, 695 out of a total 890 foreign bribery resolutions were concluded through a non-trial resolution. The same study (OECD 2019: 12) of 27 countries found all had at least one non-trial resolution system for foreign bribery and many had multiple systems.

One main reason that enforcing countries have used settlements to this extent is that they help prosecutors sidestep the often high evidentiary burdens of trial proceedings; furthermore, they are amenable to the multijurisdictional nature of foreign bribery given that one settlement can be agreed for multiple complaints arising from different jurisdictions (Hock 2021). Nevertheless several aspects of settlements have also been criticised including: the reported overuse of settlements (Rediker 2015; Roussel et al. 2023: 7); the increasing lack of criminal liability for offenders (Messick 2020a; Lord 2023: 848); whether or not the monetary sanctions resulting from settlements act as an effective deterrent (Freedberg et al. 2022; Gottschalk 2024; Dell 2013); the lack of transparency and oversight by courts in how settlements are reached (Søreide and Makinwa 2018:21); and concerns they may preclude other future legal actions, including those initiated by foreign countries.

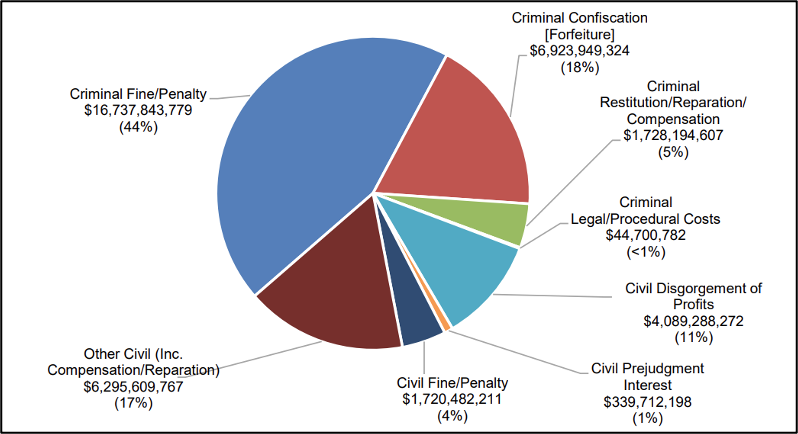

A 2021 study from UNODC estimated the breakdown of monetary sanctions imposed as part of settlements between 1999 and 2021, reflecting a diversity of different legal routes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: UNODC estimate of breakdown of type of monetary sanctions imposed as part of settlement agreements globally between 1999 and May 2021 (in US dollars)

Source: UNODC 2021: 19

This diagram gives an insight into the sheer range of different legal devices which make up the broader category of monetary sanctions. Four of the most relevant for the purposes of this answer are highlighted here:

- Fines are monetary sanctions which are meant to punish the wrongdoer and are usually payable to the enforcing state (UNODC 2021); however, it is possible that fines are accompanied by surcharges to be used for different purposes, such as allocations to victims’ funds (Dell 2020: 18). Unlike the confiscation of assets, Hickey (2021a: 378) explains that ‘the money that companies pay as punitive fines is not property derived from corruption offences’. The calculation of fines may be informed by the actual financial losses incurred by the act of bribery (Hickey 2021a: 401), but also other factors such as the severity of offence, the conduct of the offender, whether or not compensation has been granted and the desired deterrent effect against the offender.

- Confiscation of assets(forfeiture in some jurisdictions)refers tothepermanent deprivation of assets or proceeds deriving from a crime (UNODC 2021). While the term is most often associated with cases where domestic actors embezzle public funds and transfer the proceeds abroad, confiscated assets can also refer to the ‘the illicit profits, benefits or advantages of monetary value gained by companies as a result of paying a bribe to a foreign official’ (UNCAC Coalition n.d. b). As with fines, confiscated assets are normally absorbed by the enforcing country, but the path for foreign countries to obtain these assets is arguably clearer as they can stake a claim using the asset recovery process. In some jurisdictions, confiscated assets can also be apportioned as compensation for victims (UNODC 2021).

- Disgorgement of profits is the forced surrender of illegally obtained profits (UNODC 2021). In the context of foreign bribery, it concerns profits made from foreign bribery the offender would otherwise not have attained. Disgorged profits may also be used to compensate victims in certain jurisdictions (Dell and McDevitt 2022: 19). Both confiscation of assets and disgorgement of profits may be labelled as forms of ‘restitution’.

- Compensation (reparation in some jurisdictions)c800e49cb5f3 is a remedy aiming to financially address losses incurred by one party due to wrongs committed by another (UNODC 2021). Recipients of compensation can include foreign countries and overseas victims and other categories of victims such as competitor firms. There are different avenues for victims to make a claim for compensation, depending on national law. This is closely connected with the question of who has legal standing or locus standi in foreign bribery proceedings, which is discussed in further detail below. In some jurisdictions, non-state victims have the opportunity to be heard (including through victim impact statements), to directly to make claims in civil proceedings when they are accorded partie civile status (UNODC 2019: 3), or participate in the form of collective claims such as class actions or representative actions (Falconi et al. 2023: 20). In others only the prosecutor may make the request or a court may file a claim for compensation on behalf of a country or a group of victims. Compensation often constitutes an order imposed separately to other monetary sanctions, but not exclusively so (Dell 2020: 18; UNODC 2019: 3).

Multiple claims are not infrequently pursued as part of the same foreign bribery proceedings and settlement negotiations, meaning that aggregate monetary sanctions imposed are often actually made up of a combination of these legal devices. Critically, this means such claims tend not to be not mutually exclusive (for example, a fine does not preclude a compensation order from being made).

However, it should be noted that some voices in the literature are sceptical about the comparability of different forms of monetary sanctions. For example, Stephenson (2016) argues against grouping together monetary sanctions reached via different legal routes, contending that measuring levels of compensation as a proportion of overall monetary sanctions amounts to a false equivalence. While agreeing that the routes are legally distinct processes with important nuances, this Helpdesk Answer recognises value in considering different forms of monetary sanctions in tandem in order to have a wider overview of the foreign bribery landscape.

Foreign bribery legislation

The regulation of foreign bribery arguably began in 1977 when the United States passed the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). It prohibits US citizens and companies from engaging in foreign bribery, but the body tasked with enforcing the act, the Department of Justice (DOJ), has interpreted its scope widely, meaning that foreign nationals and entities have been held liable under it, for example, where companies are listed on the US stock exchange or even operate a US based bank account or where a US based internet server is involved (Hickey 2021a: 374; Falconi et al. 2023: 21).

The FCPA influenced the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD)’s Anti-Bribery Convention, which became effective in 1999 and as of September 2024, has been ratified by 46 countries (Hickey 2021a: 373-74). In turn, countries such as Australia, Brazil, Canada, France, Spain, Switzerland and the United Kingdom have introduced national legislation against foreign bribery (Falconi et al. 2023: 21).

This spread of regulation has not always been backed by corresponding levels of enforcement. In 2022, Transparency International (2022: 10) assessed that only two of the 47 countries surveyed were actively enforcing the OECD Convention (Dell and McDevitt 2022: 10) due to shortcomings in the fulfilment of many provisions (see Figure 3). Furthermore, a 2019 review by the OECD (2019: 13) found that only 23 of the 44 parties to the convention had successfully concluded a foreign bribery action.

Figure 3: Transparency International’s 2022 assessment of the enforcement of the OECD Anti-Bribery Convention

Source: Dell and McDevitt 2022

The national legislative acts prohibiting foreign bribery are generally silent on issues such as the restitution of victims (Roussel at al. 2024: 3). A notable exception is Canada’s Corruption of Foreign Public Officials Act (CFPOA) under which judges at the conclusion of a trial or non-trial resolution are required to consider compensation for victims, including by imposing a surcharge on fines (Harrington 2020: 264-65).

Nevertheless, such acts can often be read in conjunction with other legislation or policies. For example, in the US context, the FCPA does not have provisions on compensation to victims (Falconi 2023: 21), but the Crime Victims’ Rights Act can be interpreted as enabling victims’ claims under the FCPA (Rahman 2020). In the UK, the government has published tailored general principles to compensate victims (including affected states) in bribery, corruption and economic crime cases, and the UK Sentencing Council (2014) has issued sentencing guidelines which give instructions on how to calculate a fine in foreign bribery cases and mandates judges to treat a consideration of compensation as a priority.5254a5f559dc

At the international level, the OECD convention is generally silent on the compensation claims of victims of foreign bribery, but other conventions are much clearer. For example, Article 3 of the 1999 Council of Europe Civil Law Convention on Corruption (which has been ratified by 36 countries) established a right for persons who have suffered damage as a result of corruption to have the right to initiate an action to obtain full compensation for such damage.

The almost universally ratified United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) criminalises foreign bribery (Article 16) and notably contains Article 35 on compensation for damage and Article 32(5) on the protection of witnesses, experts and victims. Furthermore, it also establishes compensation claims in the context of asset recovery under Article 53 (b) and Article 57(3)(c).

Relevant UNCAC articles

Article 32(5) (protection of witnesses, experts and victims)

The views and concerns of victims are to be presented and considered at appropriate stages of criminal proceedings against offenders.

Article 34 (consequences of acts of corruption)

With due regard to the rights of third parties acquired in good faith, each state party shall take measures, in accordance with the fundamental principles of its domestic law, to address consequences of corruption. In this context, states parties may consider corruption a relevant factor in legal proceedings to annul or rescind a contract, withdraw a concession or other similar instrument or take any other remedial action.

Article 35 (compensation for damage)

Each state party shall take such measures as may be necessary, in accordance with principles of its domestic law, to ensure that entities or persons who have suffered damage as a result of an act of corruption have the right to initiate legal proceedings against those responsible for that damage in order to obtain compensation.

Article 53 (b) (measures for direct recovery of property)*

Take such measures as may be necessary to permit its courts to order those who have committed offences established in accordance with this Convention to pay compensation or damages to another State Party that has been harmed by such offences.

Article 57(3)(c) (return and disposal of assets)

In all other cases, give priority consideration to returning confiscated property to the requesting state party, returning such property to its prior legitimate owners or compensating the victims of the crime.

* The UNCAC Coalition (n.d. b) UNCAC Article 53.b – which provides for direct recovery of property through compensation claims – was precisely established to provide a concrete remedy to states harmed by corruption in situations – such as bribery or trading in influence – where the proceeds of corruption involve funds of private origin to which the state was never entitled (UNCAC Coalition n.d. b)

Roht-Arriaza (2023: 36) describes how documentation of the preparatory work for Article 35 makes it clear that the article was intended to cover both civil and criminal actions, and compensation for damage was to apply not only to states but also legal and natural persons. Olaya Garcia (2020a) sees Article 35 as providing an obligation on states for reparation. Similarly, Perdriel-Vaissiere (2014) explains how the asset recovery process established under the UNCAC applies to ‘the illicit profits, benefits or advantages of monetary value gained by companies as a result of paying a bribe to a foreign official’. Furthermore, the UNCAC Coalition (n.d. b) explains that Article 53 (b) ‘was precisely established to provide a concrete remedy to states harmed by corruption in situations – such as bribery or trading in influence – where the proceeds of corruption involve funds of private origin to which the state was never entitled’.

Others have argued that the human rights legislative regime can give rise to compensation claims, especially from non-state victims (Falconi et al. 2023). For example, the Declaration of Basic Principles of Justice for Victims of Crime and Abuse of Power adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1985 recognises the rights of victims of crime to compensation and restitution.

Under the UNCAC implementation review process, which relies on peer review mechanisms between signatory states, the UNODC noted that most reviewed state parties were assessed as having translated Article 35 into national legislation. While reviewers concluded this was largely done in a general rather than an explicit manner, they said this generally did not preclude natural persons, legal persons and foreign states being entitled to claim compensation (UNODC 2019: 3). However, as will be illustrated below, even in such jurisdictions where claiming compensation is possible, the existence of legal bottlenecks often serves to obstruct the success of such claims.

Foreign bribery cases

As already noted, multiple foreign bribery cases are concluded and settled every year across many jurisdictions. These four foreign bribery cases0f74d6304d25 were selected primarily with the aim of demonstrating how different outcomes can be reached.

Airbus

Airbus is a multinational aerospace corporation based in France and the Netherlands producing civilian, defence and space aircraft. The company faced allegations that, over a period of at least four years, numerous employees were engaged in bribery of public officials in up to 20 foreign jurisdictions to win advantageous contracts (Purnell et al. 2024), including especially egregious cases in Colombia, Ghana, Indonesia and Sri Lanka (Rahman 2020).

While there are still multiple ongoing actions against Airbus on the basis of violations of foreign bribery legislation – as well as arms export regulations (Stanford Foreign Corrupt Practices Act Clearinghouse 2020) – Airbus negotiated a settlement with enforcement agencies from France, the UK and the US in 2020, agreeing to pay a monetary sanction of US$3.7bn, which remains the global record for a foreign bribery settlement (Walker 2024). This figure constituted a combination of fines and disgorged profits.

This settlement did not, however, provide for compensation to foreign countries or overseas victims. For example, the UK’s enforcement agency – the Serious Fraud Office (SFO) – reportedly did not consider facilitating a compensation order because it was unable to easily identify a quantifiable loss to a particular party as a result of the bribery (Campbell 2021: 212).

Some affected foreign countries have complained about their failure to gain from the settlement. For example, Indonesian authorities assisted the UK’s Serious Fraud Office in investigating Airbus bribes to Indonesia’s state-owned airline, but did not obtain any part of the settlement (Walker 2024); the authorities threatened to undertake legal action against the UK and, as of September 2024, no formal agreements on compensation have been publicised (Teresia 2023).

Similarly, the government of Sri Lanka stated its intention to explore ways of claiming damages pertaining to the settlement (Rahman 2020). While experts had estimated the bribery had resulted in at least US$9 million in losses for the Sri Lankan public, when pressed, UK authorities reportedly repeated that the losses incurred by the criminal conduct was hard to measure (The Sunday Times 2023).

Glencore

Glencore is a multinational commodities trader headquartered in Switzerland. It was investigated for having operated a widespread foreign bribery scheme through its subsidiaries, intermediary corporations and middlemen to gain business advantages in natural resource-rich countries (Spotlight on Corruption 2023).

In May 2022, Glencore negotiated a settlement with authorities in Brazil, the US and the UK after being handed monetary sanctions of up to US$1.5 billion for foreign bribery and price manipulation perpetrated by its subsidiaries based in these countries (Denina et al. 2022). Approximately US$1.1 billion of this sum was reportedly paid into the US Treasury in contrast to the US$29.6 million paid to the state-owned Brazilian petrol company Petrobras which had been directly affected by the bribery. However, there had been allegations that Petrobras employees were complicit in accepting bribes (Public Eye n.d.), and indeed the company had itself been fined under separate FCPA proceedings (US Department of Justice 2018).

In trial proceedings overseen by a crown court in the UK in November 2022, Glencore was given a £280 million penalty (a combination of confiscated assets and a fine). During the proceedings, the government of Nigeria applied for a compensation order, claiming to have been harmed by Glencore’s UK subsidiary’s acts of bribery (Crown Court sitting at Southwark 2022). The court rejected the order, determining that under UK law only the prosecution or defence in the case could request such an order and that the Nigerian government did not have the legal standing to do so (Crown Court sitting at Southwark 2022). The court also reasoned that it was too difficult to identify victims, quantify the losses they had suffered and establish causation between the act and the losses, putting forward that the financial cost of the bribes themselves could not be used as a corresponding value for damages (Roussel et al. 2024: 8). It also noted that allowing claims from too wide a range of victims would pose ‘a risk of deluging the criminal justice system’ (Crown Court sitting at Southwark 2022). Following this outcome, the government of Nigeria took up its own negotiations with Glencore and, in 2024, reached a settlement of US$50 million. Civil society actors called on the Nigerian government to be more transparent in their plans to spend the funds for the benefit of affected communities (Spotlight on Corruption 2024).

Glencore had also acquired a majority stake in one of the biggest copper and cobalt mines in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) for US$585 million but received a US$440 million discount upon signing under opaque circumstances (Spotlight on Corruption 2023. Many voices, including from civil society, advocated for compensation to DRC due to the losses incurred (Transparency International, RAID and CAJJ 2024). In December 2022, Glencore agreed to pay US$180 million to the DRC to settle acts of corruption alleged to have taken place between 2007 and 2018 (Spotlight on Corruption 2023. Nevertheless, the NGO Spotlight on Corruption (2023) argued this settlement was not proportionate to the damages caused by the ‘discount’. The settlement was also criticised for opacity, and there have been calls for the DRC government to reveal how they intend to use the money to benefit victims (Spotlight on Corruption 2024).

In February 2024, a US judge ordered Glencore to pay US$30 million in compensation to the founders of a health company that provided medical services to Glencore’s employees in the DRC mines. Glencore had reportedly bribed a Congolese judge to give it a favourable ruling against the health company which in turn contributed to the latter’s financial demise (Dolmetsch 2023). Nevertheless, a civil society coalition highlighted that no compensation was given to the health company’s employees who had also lost their jobs as a result of the bribery (Transparency International, RAID and CAJJ 2024).

ICBC Standard Bank

ICBC Standard Bankis a London based bank which is 60% owned by Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) and 40% owned by South Africa's Standard Bank Group. One of its subsidiaries based in Tanzania reportedly arranged a US$6 million consultancy agreement with a shell company overseen by local public officials. This was considered to be a de facto bribe in exchange for being listed as the underwriters for a sovereign note placement note of up to US$600 million (Campbell 2021).

Investigations were launched by the SFO against the headquarters office in London on suspicion of failing to prevent this. A deferred prosecution agreement was reached in 2015, under which Standard Bank was fined US$25.2 million, and was required to pay the government of Tanzania a further US$7 million in compensation, which reflected the value of the consultancy agreement with accumulated interest (Campbell 2021).

When giving judicial approval of the deferred prosecution agreement, the Queen’s Bench Division justified the compensation order saying that it was clear in this case that the Tanzanian government had suffered a loss, and this would not have been the case ‘but for’ the de facto bribe (Hickey 2021: 403-404). In finalising the transfer of the compensation to Tanzanian authorities, the SFO was assisted by the UK’s (then) leading development actors, the Foreign & Commonwealth Office and Department for International Development (DFID) (OECD 2019: 215). Additionally, Standard Bank was bound by the DPA to cooperate with Tanzanian law enforcement who were pursuing a domestic bribery investigation into the same case (Nainappan 2020).

Odebrecht and Braskem

Odebrecht is a conglomerate headquartered in Brazil operating in very sectors – most prominently construction – and active in over 28 countries. A subsidiary of Odebrecht and also headquartered in Brazil, Braskem, is the largest petrochemical firm in the Latin American region (Persons 2023).

Between 2003 and 2016, Odebrecht and Braskem were alleged to have operated a vast and complex bribery scheme using parallel, hidden accounts that targeted numerous actors working across the local, regional and national levels in Brazil, as well as foreign officials (Persons 2023). It was estimated that they spent over US$788 million in bribes to gain advantages in bids for over 100 public works projects in 12 countries (UNCAC Coalition 2024).

These allegations were investigated by the federal police of Brazil as part of a wider bribery and money laundering case known as Operation Car Wash (OCCRP 2023). Globally, other investigations were launched, including by US national authorities who were able to apply the FCPA because, among other things, Odebrecht held offshore funds in the US while Braskem traded on the New York Stock Exchange (Persons 2023).

The DoJ led the negotiation of a settlement with Odebrecht which agreed to pay sanctions amounting to US$ 3.5 billion to resolve the charges made by the US, and in Brazil and Switzerland (US Department of Justice 2016). It was agreed that the US and Switzerland would each receive 10% of the total sanctions, and the remaining 80% would be shared with Brazil (US Department of Justice 2016). The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) led the negotiation of a settlement with Braskem which agreed to pay of US$632 million (a combination of a fine and disgorged profits); this was similarly split between the US and Switzerland, receiving 15 % each, and Brazil receiving 70% (US Department of Justice 2016).

While US authorities did not make a public statement as to why a relatively high proportion of the monetary sanctions were shared with Brazil, other commentators have noted that Brazil played a proactive role in supporting the DoJ investigation, plus the majority of the bribes under investigation were accepted by Brazilian public officials (FCPA Professor 2016).

However, many other affected national agencies – for example from Colombia, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Panama and Peru – carried out investigations into Odebrecht and Braskem’s offences, but these countries did not receive any allocations of the US led settlement (UNODC 2021: 6). Nevertheless, many of these countries concluded their own settlements later; indeed, Odebrecht agreed with the Inter-American Development Bank to make a US$50 million contribution to civil society member organisations operating in the bank’s member countries (UNODC 2021: 6).

Points of debate

The four cases described above are illustrative of the varying outcomes foreign bribery resolutions can have; outcomes which may be attributed to the specific facts of each case, but which can also, at times, appear somewhat inconsistent to observers.

This section explores in further detail the points of debate present in such cases and recurring in the literature on foreign bribery, with a particular focus on technical barriers identified by judicial actors.

Enforcing and foreign countries

Arguably one of the most pressing points of debate concerns which jurisdiction should receive the monetary sanctions resulting from foreign bribery; or, phrased otherwise, if and how they should be divided across the enforcing and foreign countries party to a case. The cases outlined above attest to a range of outcomes. In the Airbus case, the foreign countries failed to receive any portion of fines which were absorbed into the treasuries of enforcing countries. The Glencore and ICBC Standard Bank cases show that even where ancillary forms of compensation are awarded to the foreign country, they will often still be dwarfed by the level of fines paid into the enforcing country. However, the Odebrecht and Braskem cases paint a different story where the bulk of the monetary sanctions imposed was voluntarily allocated by the enforcing country to the foreign country.

This issue has become especially controversial because enforcing countries are most often in the Global North and foreign countries in the Global South. Hickey (2021a: 381) describes how many commentators consider it unethical for countries from the Global North to retain monetary sanctions as a form of revenue where the primary harms of foreign bribery affect lower and middle-income countries and their citizens. Hickey (2021a: 377) also points out that this can be viewed as hypocritical in light of the fact that Global North authorities often justify their foreign bribery enforcement efforts with reference to the harms it causes in the Global South. Olaya Garcia (2020a) argues that compensation for foreign countries could have the potential to repair trust between citizens and public institutions in the Global South, which can be instrumental for wider development goals.

Nevertheless, authorities from enforcing countries have justified not sharing monetary sanctions with foreign countries on several grounds, which have also been supported by several other voices from the literature. One of the foremost arguments is the risk of ‘recycled corruption’ or ‘repeat corruption’, which essentially holds that the fact public officials from the foreign country were found to have accepted bribes may be indicative of future corruption risks and, therefore, the potential loss of returned funds (Harrington 2020: 269). This risk is often especially pronounced where the foreign country has not held the public officials of the original bribery act accountable.

Indeed, in practice it can be difficult to extricate individual foreign bribery offenders from a wider enabling system. For example, the US Department of Justice refused a compensation request from a state-owned electricity company from Costa Rica during foreign bribery proceedings, arguing that so many employees of this company had reciprocated the bribery scheme operated by the defendant company that it should not be considered a victim but a co-conspirator instead (Messick 2016). Perdriel-Vaissiere (2014) considers the argument of repeat corruption a ‘legitimate concern’, but notes it is unfair for the citizens of the foreign country who are without fault for the corrupt behaviour of their public officials and therefore end up doubly penalised.

Another argument which has been made is that the countries where the bribery has taken place should be more proactive in investigating and prosecuting offenders themselves through, for example, their own domestic laws criminalising bribery. As any legal proceedings or settlements would take place under their own jurisdiction, any resulting monetary sanctions would naturally be paid into their own treasuries. In this vein, Stephenson (2016) argues that if enforcing jurisdictions were obliged to apportion some of the monetary sanctions in the form of compensation to foreign countries, it could disincentivise such foreign countries from initiating their own legal actions.

Hawley (2016) responded that this would be unlikely, arguing there are other, more significant reasons why countries where the bribery took place refrain from prosecuting offenders, including their fear of deterring foreign investment, their lack of capacity or experience in carrying out such prosecutions, as well as their own complicity in the offence in some cases. Additionally, Campbell (2021: 212) highlights the unavailability or absence of the necessary international cooperation mechanisms to gather evidence, such as mutual legal assistance agreements and requests. One could furthermore add that the multinational companies accused of foreign bribery often have the financial resources to engage in protracted disputes which typically precede a negotiated settlement.

Lastly, the higher levels of enforcement among certain countries may not only be attributable to the existence of political will but also to the fact that they hold certain advantages. For example, Purnell et al. (2024) argue that enforcement of foreign bribery has traditionally been driven by US authorities because they have a wider scope of corporate criminal liability than most countries. In contrast, foreign countries may not have a comparable enforcement infrastructure (Lord 2023: 854).

Calculation of compensation

One of the perhaps more debated points concerns deciding who is entitled to compensation for foreign bribery and, if so, how should the value of that compensation be calculated (Falconi et al. 2023: 47). That being said, this issue is arguably less pertinent for confiscated assets or disgorged profits, which, unlike fines or compensation, are more likely to have a fixed value.

As explained above, compensation is normally meant to correspond to the damages incurred because of the bribery. However, some of the harms flowing from foreign bribery are diffuse and can amount to material (financial losses) and immaterial damages through, for example restricted access to education and healthcare for the public (Falconi et al. 2023: 47). Similarly, foreign country governments can experience both direct and indirect harms from bribery, such as the distorted allocation of their public resources (Hickey 2021: 397).

Falconi et al. (2023: 13) describe how in most countries there are no explicit legal provisions guiding the quantification of damages for corruption, but legal actors instead normally have recourse to general principles of contract or tort law. On this basis, courts often impose evidentiary thresholds with, for example, a certain level of proximity between the act of bribery and the damage caused by it (Falconi et al. 2023: 45). This essentially means claimants will often need to meet burdensome evidentiary hurdles such as proof of damages or causation to receive compensation (Falconi et al. 2023: 47).

Furthermore, even where compensation is granted, there can be disputes over how much is awarded. In the ICBC Standard Bank case, compensation was given based on an estimation of the direct corresponding financial cost, whereas in the Glencore case, judicial actors indicated calculation on this basis was not possible, even though some estimates were proffered.

Several authors argue that compensation need not be calculated with the aim of reaching an exact figure corresponding to the harm caused, submitting that some level of compensation is better than none (Roussel et al. 2024: 15). Others point out that such precision in not expected in the calculation of fines (Olaya Garcia 2020; Hickey 2021: 398), the main function of which is to deter offenders. Indeed, the barriers placed on the calculation of compensation compared to the calculation of other monetary sanctions may go some way to explaining the ostensibly disproportionate ratio between both in foreign bribery cases.

There have been calls for alternative legal approaches that recognise these challenges and pave a way to provide compensation for the diffuse harms caused by bribery, and, indeed, such approaches already exist in other sectors, such as damages caused to the environment, for example (Dell 2020b: 23). Several authors have highlighted how the concept of ‘social damage’ as reflected under Costa Rican law could give a more expansive understanding of the damages caused by foreign bribery (Roht-Arriaza 2023; McDevitt 2016; Olaya Garcia 2016).

‘Social damage’ in Costa Rica

The criminal procedure code of Costa Rica allows victims of a criminal offence to claim damages for social harms, explicitly saying this encompasses collective or diffuse interests. In proceedings, they are then represented by the attorney general (procuraduría). The social damage clause has been applied in numerous corruption cases (Roht-Arriaza 2023: 50), including towards a successful compensation action in which French-American company Alcatel paid US$10 million to the Costa Rican treasury for the losses it caused to citizens by bribing a telecommunications company (McDevitt 2016).

Legal standing of claimants

A point of debate closely linked with the calculation of compensation is that of legal standing (or locus standi), or rather which parties are allowed to participate in or make claims regarding foreign bribery proceedings, and to what extent does that influence (or even predetermine) the outcomes of cases.

Corruption Watch (2018: 4) points out that many foreign bribery schemes are by their very nature complex, involving multiple jurisdictions and networks of actors. This can make it difficult to gather all the necessary evidence to substantiate a claim, which in turn, can essentially mean that the more complex the scheme a foreign bribery offender operates, the less likely it is that a victim can prove they suffered a harm (Corruption Watch 2018: 4). Messick (2020b) argues that the evidentiary hurdles on victims are one of the main reasons such a low number of compensation orders have been granted.

In general, being able to directly participate in trial or non-trial resolutions allows victims to advocate for their claims and submit evidence on the impacts foreign bribery had on them (Walker 2024). Otherwise, what the court hears can be skewed towards the defendant (Corruption Watch 2018), as can especially be the case in negotiated settlements (Olaya Garcia 2020a). Falconi et al. (2023: 28) explain that when victims do not have the opportunity to participate in proceedings or are not even informed about their right to do so, it can have a strong bearing on the final decision to award compensation or not. Indeed, having legal standing can be a prerequisite to be considered for compensation in the first place, as seen in the Glencore’s Nigeria case.

It is important to distinguish between two victim classes: the foreign state and non-state victims. In many jurisdictions, only other states have standing as victims whereas non-state victims or organisations representing them do not (Roht-Arriaza 2023: 36).Some voices in the literature call for a wide scope of legal standing to be applied in foreign bribery cases. Walker (2024) argues that victims should have legal standing in foreign bribery proceedings since victims often have strong representation rights with regard to other equally serious crimes. There are also practical concerns; Roht-Arriaza (2023) argues victims should have legal standing in criminal proceedings too and not only civil because under the latter legal costs are normally not covered, which can disincentivise claims.

In several jurisdictions, victims can attain legal standing through collective mechanisms. For example, if victims can fulfil certain legal criteria such as proving their claims relate to a common issue, they can then group together and make a claim under a class action taken forward by a single representative plaintiff (Falconi et al. 2023: 23-26). In several Latin American countries, including Argentina, Brazil, Costa Rica and Peru, public prosecutors have led actions to represent a wider group of victims and claim collective damages (Falconi et al. 2023: 23-24).

Others have put forward arguments for limiting the scope of legal standing; for example, the reasoning given for the rejection of the compensation order requested by Nigeria in the Glencore case was that granting it could open the floodgates for many other claims, a reflection of the diffuse harms bribery causes. Stephenson (2016) argues that foreign bribery offenders may be disincentivised from self-reporting if they fear they will face too many claims. On the other hand, proposals have been made to ensure the volume of victim claims is realistically managed, including through the appointment of a victims’ ombudsperson or coordinator at an early stage in foreign bribery proceedings (Dell 2023: 53).

During the UNCAC review process, several states reportedly claimed to have adequately implemented Article 35 by allowing for compensation orders which are issued at the discretion of judicial actors. However, reviewers reportedly regarded this as insufficient given that it does not amount to giving victims the right to initiate compensation proceedings by themselves (UNODC 2019: 3). Similarly, Taylor (2022) – commenting on the Glencore and Nigeria case – argues that deciding who are victims or not should not be only at the discretion of a prosecutor. In the Airbus negotiations, authorities reportedly argued that the final settlement did not preclude any victims from subsequently claiming compensation (Campbell 2021: 212); however, Campbell (2021: 213- 214) argues that the requirements of doing so may be onerous – especially for non-state victims – that such claims were unlikely to proceed.

Spending of funds

A final, but critical point of debate, is how monetary sanctions collected from foreign bribery cases are spent and how this is made transparent (including with the aim of avoiding the aforementioned risk of repeat corruption).

When paid into the public treasuries of enforcing countries, as Lemaître (2020) points out, monetary sanctions could conceivably be used for a range of purposes, such as covering the operational costs of enforcement agencies. However, this can equally be the case for compensation granted to foreign countries; for example, at the time of writing, it is not fully clear how the compensation allocated to Nigeria and the DRC under the Glencore resolutions will be spent and if there are guarantees it will not be subject to repeat corruption.

This point intersects with the idea that one purpose of monetary sanctions is the remediation of harms. Commentators have invariably argued that compensation could be used to fund projects addressing the wider public’s core needs, such as education and healthcare (Lemaître 2020). In terms of confiscated assets, some voices have developed a concept of social reuse, under which such assets (for example, physical spaces) could be repurposed to serve community needs (CIFAR 2024). In the Odebrecht and Braskem case, the offenders were made to pay at least a portion of their overall sanctions to civil society organisations in affected countries.

Others suggest interventions should focus on addressing ‘the actual problem around which the corruption occurred’ (Olaya Garcia 2020b). There are examples from Colombia and Guatemala where the remedy ordered by judges was for offenders to complete public infrastructure projects that remained uncompleted due to corruption (Roht-Arriaza 2023: 47). Hawley (2016) has argued that enforcing countries should consider awarding compensation upon the condition that the foreign country penalises the public officials who took the bribes as well as the inclusion of safeguards on how compensation is spent.

Furthermore, Transparency International (2015) describes how a portion of fines can be allocated for anti-corruption work. A notable example in this regard is a settlement negotiated between the World Bank and the German technology multinational Siemens, which resulted in the launch of the Siemens Integrity Initiative, a US$100 million programme funding anti-corruption projects and organisations over a 15-year period (Kelly and Graycar 2016: 25).

A related point of debate is which actor should decide how compensation spent. Roussel et al. (2024: 8) points out that even in the few cases where compensation has been granted, the enforcing countries’ judicial actors – or sometimes even the foreign bribery offender themselves – have had the final say on how the compensation is to be spent under a settlement. They see this as potentially indicative of an attitude of ‘benevolent stewardship’ and argue the decision would be better placed with the foreign country where the compensation will be sent (Roussel 2024 et al.: 10). Olaya Garcia (2020b) argues that victims themselves, perhaps represented by civil society organisations, should be able to advise on the use of funds.

Enhanced international cooperation

One can conceive of several factors necessary for a change in the distribution of foreign bribery monetary sanctions, including greater demonstrations of political will from enforcing countries as well as more efforts from judicial actors to resolve legal bottlenecks, as reflected in the previous section. This section focuses specifically on the role enhanced international cooperation can play.

Multilateralism

The multijurisdictional nature of foreign bribery makes it especially relevant for actors involved in diplomatic and foreign affairs, who can play an important advocacy role in multilateral fora.

While international legal instruments and policy declarations reflect a global consensus in general in support of compensation to foreign states and overseas victims (Falconi et al. 2023), these have not resulted in much progress (Corruption Watch 2018). Hickey (2021a) notes that enforcement agencies lack the necessary frameworks to guide compensation processes. There have therefore been calls for more specific multilateral commitments which would give foreign countries and overseas victims more predictability in the outcomes (Søreide and Makinwa 2018: 25).

For example, some voices have called for the establishment of an ‘international victims of corruption relief fund’ which could be funded by monetary sanctions resulting from foreign bribery cases and be ‘dedicated to the amelioration of harms caused by corruption’ (Roussel et al. 2024: 12-13). Similarly, the High Level Panel on International Financial Accountability, Transparency and Integrity for Achieving the 2030 Agenda (FACTI) report called for the establishment of escrow accounts managed by regional development banks to host confiscated assets or disgorged profits until they can be legally returned to originating jurisdictions that have adequately proven that such proceeds will not be at risk of repeat corruption (Owasanoye and Yongding 2021).

Elsewhere, Transparency International has argued that the OECD Working Group on Bribery should develop and apply guidelines for granting compensation to victims in foreign bribery cases, which would support timely notice to victims about foreign bribery proceedings as well as recognise a wider scope of victims and facilitate their ability to make claims (Dell 2020: 9)

However, political obstacles may prevent such initiatives. For example, during negotiations on the OECD’s 2021 Recommendation of the Council for Further Combating Bribery of Foreign Public Officials in International Business Transactions, some member states and NGOs reportedly advocated for the inclusion of language on victims’ rights and victims’ compensation, but this was blocked by certain OECD member states (Dell and McDevitt 2022: 16).

This does not preclude there being greater political appetite in the future. On the one hand, enforcing states may not see it in their self-interest to surrender control of monetary sanctions secured in their jurisdiction. However, some enforcing counties are arguably increasingly experiencing political fallback; for example, the Airbus case shows how aggrievances from a foreign country about monetary settlements can lead to a breakdown in relations with the enforcing country.

Law enforcement

As they typically implicate multinational companies active in numerous markets, foreign bribery cases often span multiple jurisdictions requiring coordination between different law enforcement agencies. However, greater cooperation between investigatory bodies responsible for enforcing foreign bribery can also lead to more sharing of monetary sanctions, as the Odebrecht and Braskem case clearly demonstrates.

At the beginning of investigations, agencies from enforcing countries can engage with foreign country authorities and representatives of victims to ensure their concerns are accounted for in important decisions; for example, those relating to settlements (Taylor 2022). Regarding the conclusion of cases, some countries have bilaterally developed memorandums of understanding to facilitate compensation for victims (Walker 2024). The OECD (2019: 127) highlights how Brazil has facilitated another avenue towards compensation through the inclusion of a ‘condition in a non-trial resolution that the foreign bribery offender must reach an agreement in the victims’ country within a pre-determined amount of time’.

Transparency International (Dell 2020b) has called on enforcing countries to share information and financial resources to help foreign countries in their own investigations. Indeed, if a foreign country has increased capacity to prosecute bribery domestically, it can absorb any resulting monetary sanctions and thus decrease its reliance on the possibility of compensation from an enforcing country as a recompense for the harms suffered (although a country domestically enforcing a bribery case may not preclude foreign bribery actions taken from other countries for the same act).

UNODC (2021) describes how, under Operation Car Wash, Brazilian authorities greatly expanded its enforcement of domestic bribery. This not only resulted in hundreds of domestic resolutions but also reportedly played an important role in facilitating Brazil’s receipt of monetary sanctions reached in foreign bribery settlements led by Switzerland, the US and the United Kingdom, including in the Glencore and Odebrecht and Braskem cases.

Development actors

Enforcement agencies may not be best placed to advise on all matters relating to monetary sanctions; for example, Hickey (2021a: 379) argues that foreign aid agencies are better placed to ‘administer complex systems that ameliorate the harms that corruption can cause to societies at large’. De Simone and Zagaris (2014) explain this is enabled by the fact that such agencies often possess a comparatively stronger knowledge of the local context in foreign countries and an existing network of contacts important for information sharing purposes.

Indeed, the role of such agencies may be all the more critical considering that enforcing countries are most often in the Global North while foreign countries are in the Global South. Development actors can provide financial support, capacity building and technical assistance for the investigation and prosecution of domestic bribery in the latter countries, as well as on how they can claim compensation from foreign bribery proceedings (De Simone and Zagaris 2014).

De Simone and Zagaris (2014) set out a further list of ideas for how donor agencies can both advocate for greater proportions of compensation among key actors in their home countries and monitor any funds dispersed to foreign countries (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: proposed measures donor agencies can take in the restitution of monetary sanctions from foreign bribery

|

Restitution |

Promote and facilitate restitution to developing countries of funds recovered in foreign bribery cases. |

In their home countries, donor agencies can:

|

| Monitoring and managing returned funds | Facilitate restitution and counter concerns related to the potential loss of returned funds. |

Donor agencies can:

|

Source: De Simone and Zagaris 2014: 31-32

The role of development agencies has been particularly prominent in the UK system. For example, the (then) leading development agencies of the Department for International Department (DFID) were given a key role in assessing potential compensation for foreign bribery.

UK general principles (1 and 3) to compensate overseas victims (including affected states) in bribery, corruption and economic crime cases

The general principles are as follows:

- The Serious Fraud Office (SFO), the Crown Prosecution Service (CPS) and the National Crime Agency (NCA), hereafter referred to as ‘the departments’ will consider the question of compensation in all relevant cases.

- The departments will work collaboratively with the Department for International Department (DFID), Foreign and Commonwealth Office (FCO), Home Office (HO) and HM Treasury (HMT) in relevant cases to:

- identify who should be regarded as potential victims overseas. This may be in the form of an affected state.

- assess the case for compensation

- obtain evidence which may include statements in support of compensation claims

- ensure the process for the payment of compensation is transparent, accountable and fair

- identify a suitable means by which compensation can be paid to avoid the risk of further corruption

(Serious Fraud Office 2018).

In a UK case known as Smith & Ouzman, DFID played an important role in facilitating compensation to Mauritania and Kenya; it overcame reported concerns about the risk of repeat corruption by helping to identify infrastructure and health projects to spend the funds, which led, for example, to the successful purchase of ambulances in Kenya (OECD 2019: 128). Similarly, Harrington (2020: 277-78) proposes the establishment of a victims’ fund in Canada which would be administered by the international development ministry to avoid repeat corruption and facilitate input from authorities and local communities from the foreign country into how it is spent.

In this way, development actors can also play a role through their close relationships, funding and working with international organisations and civil society. For example, Swiss authorities have concluded foreign bribery settlement agreements containing conditions that a payment be made to support projects run by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC). However, a study by the OECD (2019: 126) found that most compensation systems operated by responding OECD member countries did not allow for payments to be made to NGOs, whether domestic or foreign.

- While the exact meaning of these terms may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, the term ‘compensation’ is adopted for the purposes of this answer (on the basis of it featuring in Article 35 of the UNCAC, the most universally ratified anti-corruption instrument of its kind). See Hickey (2021a: 399-400) for an alternative typology on how to distinguish these processes.

- For a more comprehensive overview of the consideration of victims under the FCPA and the UK Bribery act, refer to this previous Transparency International Helpdesk Answer.

- For the purposes of this paper, basic summaries of these cases are provided, highlighting compensation claims. It is noted these are complex cases spread over multiple jurisdictions over several years, and some aspects of the cases may still be subject to further proceedings. The reader is invited to consult further case law and literature for further information.