Awareness raising as an anti-corruption intervention

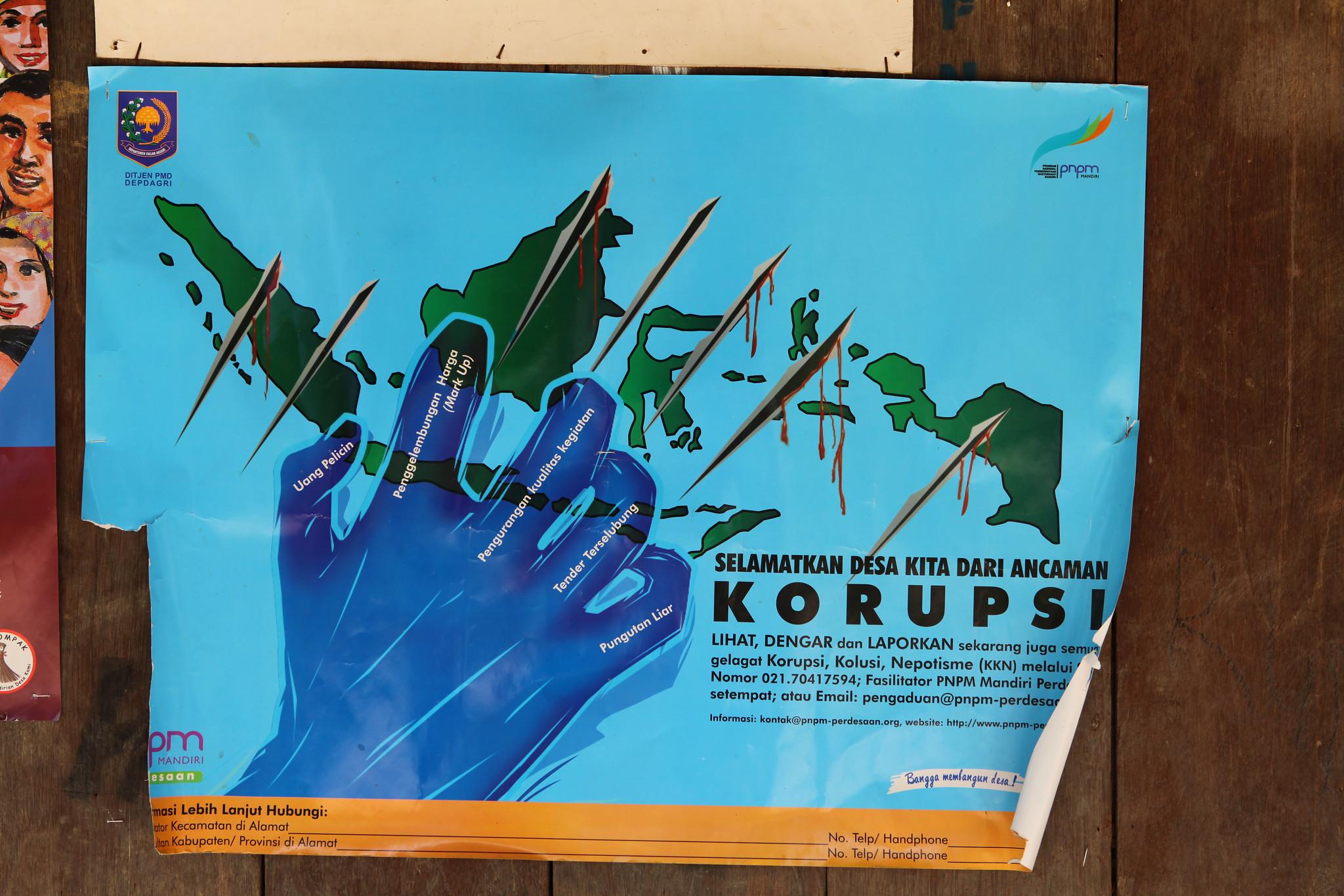

Anti-corruption strategies almost always contain an awareness raising element.f79a3f6b7004 Governments, donors and/or non-governmental organisations routinely aim to raise public awareness about the problem and consequences of corruption through billboards, posters, murals, and radio and television shows. Along with hoping that messaging will increase reports of and refusals to engage in corruption, many also see awareness raising as a tool to shift social norms and tolerance towards corruption, as well as to strengthen grassroots demands for accountability and clean government.

In practice, the effectiveness of awareness raising efforts is usually assessed in terms of their reach – how many people see them – which speaks to an overarching assumption: these campaigns will work as intended as long as enough people are exposed to them. Over the last decade, however, a growing body of research has explored the potential positive and negative impacts of anti-corruption messaging by examining how exposure to messages shapes attitudes and behaviour.

Findings suggest that in some cases such messages backfire, even making individuals more likely to pay a bribe, and that when this does not happen, they tend to have no impact at all.13c305357ffd Significantly, these kinds of worrying outcomes are not limited to anti-corruption messaging. A wider body of literature on public health campaigns has also highlighted the potential for awareness raising messages to be ineffective or to backfire.b2fb74e15a82 Taken together, these alarming findings suggest that resources spent on awareness raising risk being wasted, or even worse, doing more harm than good. Therefore, a clear policy implication has emerged: awareness raising campaigns, including traditional anti-corruption messaging, should be halted until they have been systematically tested and shown to likely have a positive effect.

Potential to backfire

Many studies have been conducted on the impact of anti-corruption messages, but prior to 2016 these tended to be more descriptive and did not systematically investigate the impact of messages, or they focused on the impact such messaging had on voting. Since 2016, however, nine prominent studies have been conducted that use experimental techniques to isolate what impact anti-corruption messaging has on beliefs about corruption and anti-corruption efforts, and on willingness to bribe.1b8eb08496f7 Each have adopted a similar approach. Participants are randomly assigned to either treatment or control groups, with the former exposed to a message, while the latter is not. Estimates of the impact of exposure to messaging are established by comparing how participants who are exposed to a message (treatment group) respond to a survey or behave in a simulated ‘bribery game’ to the behaviour or responses of participants who are not shown a message (control group). Table 1 below shows that across the nine studies, 19 messages have been tested in seven countries.

Strikingly, the literature finds that more than half (10) of the 19 messages have backfired to some extent. Specifically, exposure to the message tested in Corbacho et al.’s study in Costa Rica – about bribery increasing – elicited greater self-reported willingness to bribe.492f263c0198 Peiffer’s four very different messages tested in Jakarta, Indonesia, all increased concern about corruption, reduced pride in the government’s anti-corruption response, reduced confidence that ordinary people could easily engage in civic anti-corruption activity, and reduced willingness to protest against corruption.2a360e7f3491 These findings are noteworthy because the four messages tested were different from each other but tended to have the same level of impact. Two of these messages described the widespread nature of corruption, but another touted the government’s successes in controlling corruption and the last was even an ‘up-beat’ message which described ways citizens could get involved in anti-corruption activity.

Finally, and perhaps most worryingly, Cheeseman and Peiffer’s study in Lagos, Nigeria, found that messages could make individuals more willing to pay a bribe.ed65d3910019 What makes this study distinctive is that participants were invited to play a game with real money in which participants had the option of bribing a third-party referee in order to do better than a rival player. Their findings make for stark reading: three of the five messages tested were found to actually encourage bribery.

This is particularly significant because the messages tested by Cheeseman and Peiffer were also substantively different to one another, demonstrating again that a wide range of messages can have a negative effect. The three that encouraged bribery respectively described corruption as endemic, as being against religious moral teachings, and underlined the government’s successes in controlling corruption. Exposure to four of their five messages also reduced agreement that taxes should be paid.271353162333

These findings are a stern reminder that raising awareness of corruption through messaging is not the same as helping to address it, and that such efforts may in fact be exacerbating the problem. So why does this happen? Drawing on insights from political messaging and social norms research, scholars have suggested that anti-corruption messaging may be ill equipped to change how people think about corruption because it tends to be the type of issue that people already have strong feelings about. Especially for those already convinced that corruption is widespread, instead of changing minds, messaging is more likely to reinforce pre-existing beliefs that the problem is too big to solve and too intractable to try to resist.ea911bc1c2a4

This is especially said to apply to messages which emphasise a descriptive social norm; i.e. norms based on beliefs about how others behave.5699ed8d7da6 This is worrying, as these are the most common kinds of messages used in practice. A central theme of anti-corruption messaging campaigns has been to raise public awareness to the scale and consequences of corruption.9465a1d410c3 Such messaging invariably highlights a descriptive norm that many people in society engage in, benefit from, and/or facilitate corruption.75fe2121607f

In addition to making people think more about the problem, ‘descriptive norm’ awareness raising (emphasising how widely practiced corruption is) also risks making corruption appear to be socially acceptable. As a result, it can encourage individuals – who have been shown in a number of studies to opt into forms of behaviour that they believe their peers are already doing784bb58360e5 – to adopt more positive attitudes towards participating in graft.

Worryingly, a similar risk has been noted with respect to raising awareness to other types of social bads. For example, Paluck and Ball092273f68749 argue that descriptive norm-based awareness raising around rape in the Democratic Republic of Congo may have made gender-based violence seem more socially normative, working to encourage men to commit such violence. Six of the 19 messages tested in the anti-corruption messaging literature overtly emphasise a ‘negative’ descriptive norm, that corruption is widely practiced or on the rise, most of which were found to have backfired to some extent (Table 1).

Table 1: Anti-corruption messaging literature finds most messages counterproductive (red) or ineffective (amber). Few worked as intended (green)

|

Themes of messages tested |

Effect |

Location |

Study |

|

Increasing rate of bribery in country |

Red |

Costa Rica |

Corbacho et al. (2016) |

|

Grand corruption is endemic |

Red |

Jakarta |

Peiffer (2017; 2018) |

|

Petty corruption is endemic |

Red |

||

|

Government successes in anti-corruption |

Red |

||

|

Citizens can get involved in anti-corruption |

Red |

||

|

Corruption is endemic |

Amber |

Port Moresby |

Peiffer and Walton (2022) |

|

Corruption is illegal |

Amber |

||

|

Corruption is against religious teachings |

Amber |

||

|

Corruption is a ‘local’ issue |

Green |

||

|

Bribery declined recently in region |

Amber |

Manguzi |

Köbis et al. (2019) |

|

Corruption is endemic |

Red |

Lagos |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2021; 2022) |

|

Government successes in anti-corruption |

Red |

||

|

Corruption is against religious teachings |

Red |

||

|

Corruption steals tax money |

Red |

||

|

Corruption is a ‘local’ issue |

Red |

||

|

Citizens strongly condemn corruption |

Green |

Mexico |

Agerberg (2021) |

|

Corruption is endemic |

Amber |

Albania |

Cheeseman and Peiffer (2022b) |

|

Citizens strongly condemn corruption |

Amber |

||

|

Wealth is lost to other countries |

Amber |

Red: at least one unwanted effect; Amber: no impact/largely no impact across outcomes; Green: clear intended impact

* Specifically, the message tested had no impact bribery in game for those who took on role of citizen. Reduced bribery for those who took on role of public official.

** Specifically, these messages had no impact on self-reported willingness to bribe or report corruption, or on beliefs about acceptability of corruption, though increased agreement that respondents can hold public officials accountable by not voting for corrupt ones, as well as willingness to vote for candidates who focused their campaign on fighting corruption.

No safe bets

One clear lesson has emerged from the research conducted so far: anti-corruption awareness raising campaigns should avoid emphasising a descriptive norm, as such messaging is especially poised to backfire. Unfortunately, a complementary lesson pointing to messaging strategies that are a safe bet and will likely work as intended has not emerged. Three trends in the research are worth noting in this regard.

First, other types of messages – which do not explicitly focus attention on the scale of the problem – have also been found to backfire. Perhaps most surprisingly, Peifferc074bf8d2ea6 and Cheeseman and Peiffer’s82acfcbd0e42 ‘good news’ messages emphasising government successes in controlling corruption, and Peiffer’s252b709c455b ‘upbeat’ message about how easily citizens can get involved in anti-corruption civic activity were also found to have the opposite impact to that which was intended. Indeed, these findings are consistent with wider research on so-called ‘boomerang effects’ of messaging, which has shown that even carefully designed messaging can inadvertently focus attention on information which causes an individual to respond in an unintended way.abc491589fc2 Importantly for practitioners, these findings suggest that even positive messages can encourage people to recall firmly held beliefs that corruption is endemic and intractable, and so still risk doing more harm than good.

It is also important to recognise that in many contexts ‘positively’ framed anti-corruption messages will lack credibility. Efforts to raise awareness of the fact that the government is actively controlling corruption, for instance, will lack credibility in a place where no serious efforts have taken place and citizens experience graft on a daily basis. Intuitively, political messaging research has established that messages with weak arguments – and messages that lack everyday validity – are more likely to result in unintended, ‘boomerang’ effects.cdab16708be6

The second trend is that many messages have failed to register any impact on the outcomes scrutinised. Peiffer and Walton, for example, found that exposure to three of the four messages tested in their study in Port Moresby, Papua New Guinea – one on corruption as endemic, another about corruption being illegal, and a third framing corruption as against religious, moral teachings – had no impact on attitudes towards reporting corruption.147239a0fec1 Similarly, Köbis et al. found that exposure to even an up-beat message about how bribery had fallen locally, failed to have any impact on the participants’ willingness to pay a bribe in a lab-based simulated bribery game, when those participants took on the role of the ‘citizen’.11008032f195 Cheeseman and Peiffer also found that exposure to a message about corruption being a ‘local issue’ and another which framed corruption as stealing tax money in Lagos had no impact on the majority of participants’ willingness to bribe in their bribery game.57cd5641eef5

Finally, Cheeseman and Peiffer’s, study in Albania finds that exposure to two messages, one of which described corruption as being endemic, and another with a more positive spin – namely that citizens strongly disapprove of corruption – had no impact on self-reported willingness to bribe or report corruption, or on beliefs about the acceptability of corruption.f23b4d6ebdd7

In other words, a wide range of messages with different thematic emphases and tones have been found to be unimpactful. These ‘null’ results are important because the outcomes scrutinised in the literature reflect some of the core aims of anti-corruption awareness raising, such as bolstering positive attitudes about and a willingness to report corruption, reducing the acceptability of corruption, as well as reducing a willingness to engage in bribery. These findings suggests that, in practice, investments in anti-corruption strategic messaging are often a waste of resources.

Third, it seems unlikely that the findings of the two studies that find that messages have worked as intended can be reliably generalised. To be clear, only two (of 19) messages tested thus far have registered only ‘positive’ or intended impacts. In both cases, subsequent studies testing similar messages have failed to support these positive results, undermining confidence in how generalisable initial optimistic findings were. In the first instance, Peiffer and Walton’s previously mentioned study found that exposure to a message framing anti-corruption as ‘local’ issues encouraged favourable attitudes towards reporting. However, Cheeseman and Peiffer’s study tested the impact of a very similar message in Lagos where ethnic identification is also salient, and, as noted earlier, found that it had no impact on bribery.feb3c063422e

The second message tested which has had a clear ‘positive’ impact was from Agerberg’s survey experiment conducted in Mexico.06c8b51c9167 This message emphasised the fact that citizens strongly condemn corruption. Those exposed to this message demonstrated less acceptance that corruption is a basic part of Mexican culture, and a lower likelihood of self-reported willingness to pay a bribe. However, Cheeseman and Peiffer also tested the impact of a similar anti-corruption message in their survey experiment in Albania.1463de67ac66 As noted earlier, they found that exposure to it had no impact on self-reported willingness to bribe or report corruption, or on beliefs about acceptability of corruption, suggesting that Agerberg’s hopeful findings may not be generalisable. The overwhelming takeaway from existing research, therefore, is that anti-corruption messages rarely, if ever, have the desired effect.

More broadly with respect to generalisability, it is important to note that awareness raising efforts vary considerably in practice and that the research conducted so far has not considered the impact of some of these variations. For example, it is unclear how the impact of messaging is shaped by who delivers the message, the length and intensity of exposure to messaging, the media through which it is communicated, and how messaging campaigns interact with other anti-corruption efforts. The geographical coverage of studies is also not exhaustive. These limitations point to the need for further research in this area. We currently have no evidence to suggest, however, that these variations matter for the efficacy of messaging campaigns. The need for further research therefore does not take away from the clear lesson of the studies that have been conducted, namely that there is not a ‘safe’ messaging strategy that can always be relied upon to deliver the expected and intended effects.

The need to test messages

These findings suggest that practitioners should think hard about whether to conduct anti-corruption awareness raising campaigns, which may not offer value for money even if they do not backfire. If such campaigns are seen to be necessary – for example because under-acknowledging major social problems may give implicit license to a status quo that facilitates them – then it is essential to test their impact on a sample of the target audience before they are communicated to the wider public.

Anti-corruption message testing should not rely exclusively on focus groups or interviews for two reasons. First, participants in such research may feel pressure to give researchers answers that participants think they want to hear, rather than report how they truly feel about a message. Second, anti-corruption messaging very likely impacts on attitudes subconsciously, and so individuals may not be fully aware of the true impact that a message is having.

Experimental techniques must therefore be used as they can provide a systematic estimate of the effect of exposure to messages. This strategy considerably reduces the risk of false reporting by individuals, as participants are never asked what a given message made them think or feel. This kind of pre-deployment testing should become a staple component of messaging development processes in any anti-corruption messaging campaign. Testing in this way while continuing to innovate how messages are framed and otherwise designed may also be the only way to find more effective messaging narratives that work as intended in the contexts they are deployed in. Further details on how such tests can be conducted can be found in Cheeseman and Peiffer.4133211cfbbf

It is also important to note that even the most promising messaging campaign may be ill suited to change some behaviour. Citizens who come to be more critical about corruption because of an effective messaging strategy may be unable to do anything about it, for example, in highly authoritarian contexts where openly critical citizens are repressed. Moreover, in systems in which corruption is functional – i.e. it is necessary to get basic tasks done, such as overcoming economic, political and administrative blockages – refusing to engage in graft may be impractical for many ordinary people. This will be especially the case for those who have fewer resources and connections, and a large number of people who depend on them for food, education, and healthcare. Where both of these conditions hold, awareness raising efforts may not change behaviour even if it is successful in changing how people think about corruption.

(For a more nuanced version of this argument that provides an example of how to test anti-corruption messaging and includes a longer discussion of core findings, see: Cheeseman, N. and Peiffer, C. 2021. The curse of good intentions: Why anti-corruption messaging can encourage bribery.)

- Cheeseman and Peiffer 2021; 2022; UNCAC 2004.

- This brief’s literature review draws on Cheeseman and Peiffer (forthcoming).

- Greszczuk 2020; Steadetal 2019.

- Corbacho et al. 2016; Peiffer 2017; 2018; Peiffer and Walton 2022; Köbis et al. 2019; Cheeseman and Peiffer 2020; 2021; 2022; 2022b; Agerberg 2021.

- 2016.

- 2017; 2018.

- 2021.

- Cheeseman and Peiffer 2022.

- Peiffer 2018; Cheeseman and Peiffer 2022.

- eg Legros & Cislaghi, 2020.

- eg UNCAC 2004, Article 13, p. 15.

- Agerberg 2022.

- Tankard and Paluck 2016; Biccheri and Dimant 2019.

- 2010.

- 2017; 2018.

- 2021; 2022.

- 2017; 2018.

- Bryne and Hart 2016.

- Park et al. 2007.

- 2022.

- 2019.

- 2021.

- 2022b.

- 2020.

- 2021.

- 2022b.

- 2021; 2022.