Enablers of corruption, enablers of war

Russia’s full invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 affected the world significantly. Unprecedented sanctions and restrictive measures were adopted against Russia, its oligarchs and political elite. The assets of sanctioned Russians – from bank accounts to mansions and yachts – are being identified and targeted all over the world, shining a spotlight on the huge amount of goods and properties owned and stashed in Western countries. This includes the US$300 million yacht seized in Fiji at the request of the United States,c17a6ecf1df0 as well as yachts seized in Spain (eg, The Tango estimated at US$90 million), Italy (eg, Sailing Yacht A valued at US$440 million) and France (eg, Amore Vero estimated US$120 million).818b6a009007 The difficulties of tracing, freezing, seizing, and confiscating these assets were also thrown onto the world stage.

Moving illicit funds out of Russia or other countries would not be possible without the help of ‘enablers’ – also known as ‘professional enablers’ or ‘gatekeepers’ – such as lawyers, financial experts, accountants and real estate agents. Some of the support provided by these enablers might qualify as legal (following the letter, though perhaps not always the spirit, of the law), and some might not (being wholly illegal). Either way, countries are beginning to realise that some of their citizens are helping to facilitate the financing of war and illicit acts – and that this carries consequences and risks. A 2023 paper found that ‘governments have been slow to address the enabler problem’.450967514f8b Because these ‘trusted experts’ have not been targeted, Russian oligarchs have been able to bypass sanctions and enjoy their wealth.4557aaf04f76

However, in May 2022, the United States (US) government banned ‘services critical to Russia’s wartime effort’, stating that

Wealthy Russians have relied on U.S. expertise to set up shell companies, move wealth and resources to alternate jurisdictions, and conceal assets from authorities around the world. In addition, Russian companies, particularly state-owned and state-supported enterprises, rely on these services to run and grow their businesses, generating revenue for the Russian economy that helps fund Putin’s war machine.f3b44e7045f9

US-based accounting firms, management consultancies and trust and corporate service providers were formally identified – for the first time in the US –as providing essential services enabling unethical behaviour and they were banned from providing those services to Russian nationals. In September 2022, following the path of the US, the United Kingdom (UK) announced that Russians will no longer have access to architectural services, advertising services, transactional legal advisory services, and auditing services.521a7a7ee3b5

Enablers do not limit their services to Russian oligarchs. They also support political elites to hide corrupt practices and launder proceeds from corruption; they help organised crime networks and terrorists; and they assist multinational companies that want to evade taxes. Over the last five years, several reports and investigations have examined the role of enablers: who they are, the type of services they provide to facilitate illicit financial flows81c1891c8580 (IFFs) and the actors they support.92fa76e72e2a

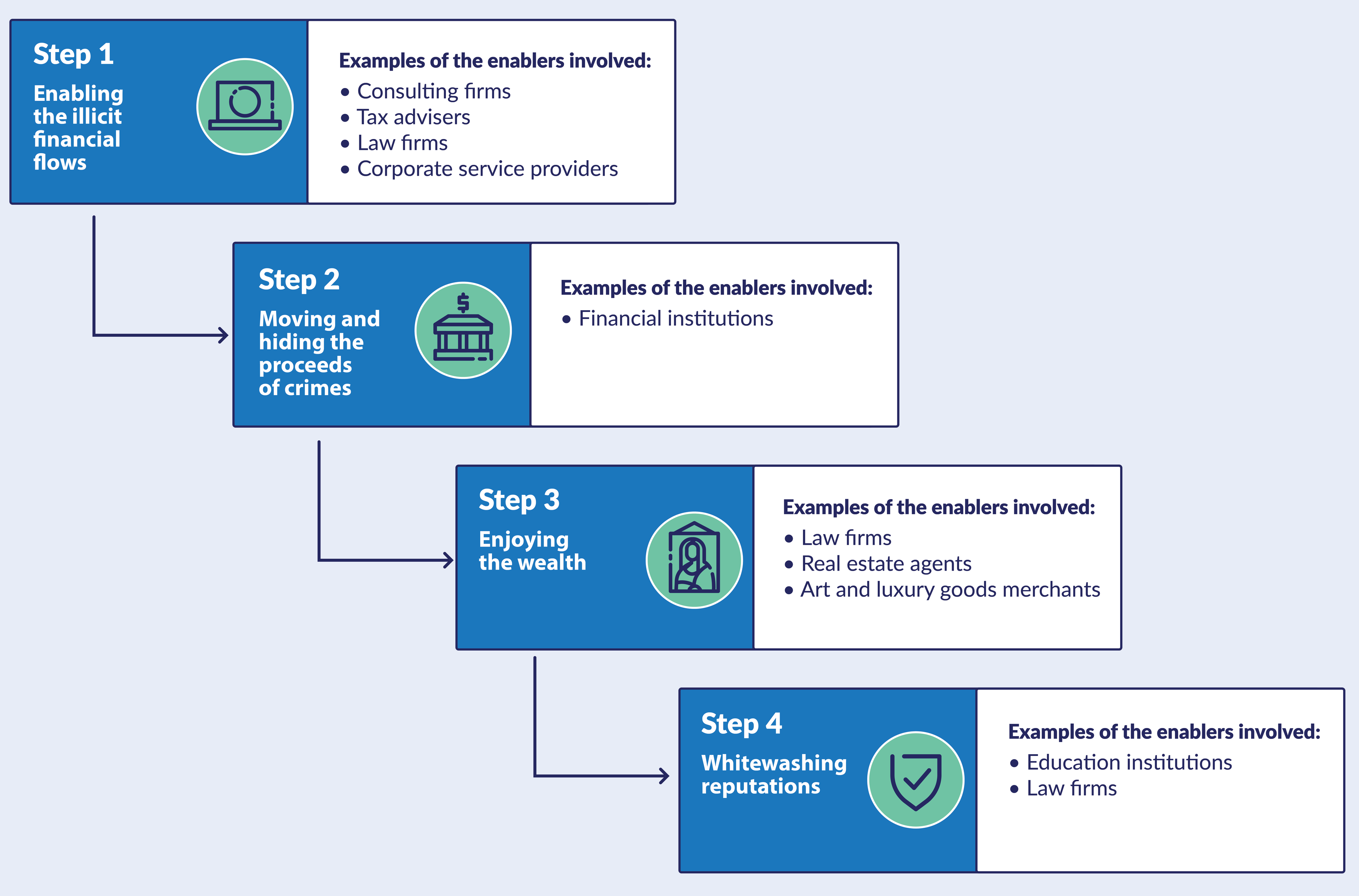

However, none of the research has looked at the different stages of IFFs at which enablers intervene: initiation, hiding and laundering, utilisation, and whitewashing. This U4 Issue explores the ways in which enablers have supported ‘kleptocrats’ (ie, ‘individuals empowered to gain from the system through their political connections and status and by a lack of institutional oversight and accountability’)619e59f0f741 at each of these four stages. It also provides recommendations to donor agencies and the relevant ministries in their home countries.

Caveat: Ascribing intentionality and liability in the case studies

The U4 Issue is based on publicly available cases, reported by investigative journalists, researchers, law enforcement and academia. It does not provide an exhaustive list of cases where enablers were involved, but it presents a wide range of cases and actors around the world. In addition, in all the cases presented in this U4 Issue, it is challenging to determine whether the enablers were unwittingly involved, wilfully blind, corrupt, or complicit (U4 Helpdesk Answer 2021). The Issue does not assess whether the support from enablers could be qualified as criminal activity. More research is needed on a case-by-case basis to determine the level of their active participation and knowledge that their actions would enable IFFs.

The value chain of enablers

Proceeds of corruption and other forms of IFFs, including money laundering and tax evasion, regularly end up in countries other than the country where the IFFs took place. To move this money out of their own country, kleptocrats need experts and advisers: the enablers that set corruption and tax evasion schemes in motion and that have specific knowledge, training, skills and experience. Different enablers intervene at various stages, providing diverse services. Enablers provide services to kleptocrats to:

- Initiate the scheme of corruption or tax evasion.

- Hide and launder the proceeds from these crimes.

- Allow kleptocrats to enjoy the benefits of the illicit wealth they acquired.

- ‘Whitewash’ the reputation of kleptocrats.

Enablers are involved at four main stages

Step 1: Enabling the illicit financial flows to happen

In the first stage, complex corporate structures and bank accounts in multiple jurisdictions are set up to enable corrupt practices or tax evasion to take place. Various enablers can be involved.

Consulting firms and tax advisory firms

A myriad of enablers provide company registration services, including consulting firms, accountants and tax advisors. They will often register a complex network of (shell) corporate legal entities including companies, trusts, and foundations in secrecy jurisdictions to hide the ultimate beneficial owners, ie, the real flesh-and-blood human being who owns or controls a legal entity.

Consulting firms such as Boston Consulting Group, PwC and McKinsey came under scrutiny for providing services to Angolan billionaire Isabel dos Santos, the daughter of José Eduardo dos Santos, former President of Angola, and ignoring corruption red flags and persistent allegations of corruption around her business activities.ce6f9411bc98 These firms had allegedly set up shell companies and moved money for Isabel dos Santos and advised her on ways to avoid taxes.6b58f83c02d9 For example, PwC reportedly suggested ‘a dos Santos retail group called Grupo Condis that it could take advantage of “very competitive” tax rates, “potentially between 0% and 5%,” by incorporating a holding company in an offshore financial center such as Malta or Singapore’.0747f10635e9 According to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ), ‘firms in PwC’s global network billed more than $1.28 million between 2012 and 2017’ for tax-related advice to ‘the dos Santos empire’.1bc308be0d30

Law firms and corporate service providers

Lawyers can be involved in different stages of the corruption and tax evasion scheme. At this first stage, they can provide advice, whether knowingly or unknowingly, on how to enable the IFF-related activities, for example, by registering companies and setting up anonymous corporate legal entities, managing corporate legal entities and thus shielding the beneficial owner.

Mossack Fonseca, a Panamanian law firm and corporate service provider, was the first enabler to make headlines following the revelations of the Panama Papers in 2016. Mossack Fonseca provided services to 140 politicians and public officials around the world. It acted as a registered agent for more than 300,000 companies registered in secrecy jurisdictions such as the British Virgin Islands, Bahamas, Panama and Seychelles.c7dd543fa918 It worked with more than 14,000 banks, law firms, company incorporators and other middlemen to set up companies, foundations and trusts for customers.f03ad031e2a2

Step 2: Moving and hiding the proceeds of crimes related to illicit financial flows

The second step in which enablers play a crucial role is in disguising the proceeds of corruption or tax evasion. Hiding the origin of the funds is crucial. Multiple corporate legal entities, bank accounts, products and jurisdictions are used to make the origin of the funds more difficult to detect. Several enablers are involved at this stage, but the involvement of one, in particular, is required.

Financial institutions

Kleptocrats often move the proceeds of corruption and tax evasion through the financial system. Domestic and international banks provide services such as creating and managing corporate legal entities, opening bank accounts and in some cases hiding the beneficial owner, advising on tax-related matters, and providing correspondent banking services.

Banks play a role in facilitating IFFs by allowing suspicious transactions, sometimes without filing Suspicious Activity Reports with competent authorities, or by not conducting proper due diligence procedures on their customers and the origin of funds (also known as ‘know your customer’ (KYC) rules). Over the last ten years, the role of banks in enabling IFFs has been exposed by various scandals such as the Laundromats, the Paradise Papers, the Luanda Leaks, FinCEN Files and Pandora Papers. For example, through its Laundromat investigations (the Russian Laundromat and the Azerbaijani Laundromat in 2017, the Troika Laundromat in 2019), the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) revealed how Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Moldovan and Russian banks authorised suspicious transactions from high-risk clients, including Russian oligarchs. Between 2007 and 2015, the Estonian branch of Danske Bank allegedly helped to launder 200 billion euros.751ebd2ae1f1 The 2022 SwissLeaks or ‘Suisse Secrets’ scandal exposed how the bank Credit Suisse had opened and maintained bank accounts for high-risk clients, including political elites, involved in money laundering or corruption cases.0c071f83270a Accounts identified as ‘problematic’ contained over US$8 billion in assets.91cf7b1bb654

In addition to the role played by major international banks, recent investigations have highlighted a lesser known trend: some banks are owned by politically exposed persons (PEPs) suspected of corruption, or by individuals who turn a blind eye to suspicious transactions, increasing the ease with which funds of illicit origin can be moved. For example, Francis Selemani, the brother of the former president of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), managed BGFIBank DRC. Francis Selemani and his family allegedly used the bank ‘to misappropriate public funds, transferring millions abroad and purchasing millions of dollars in foreign real estate’.4715e50e8d2a According to documents reviewed by The Sentry, between 2015 and 2018, more than US$12 million was sent to Selemani’s own accounts and to companies he owned or controlled.

In another instance, Rafael Marques, an anti-corruption activist and founder of Maka Angola, called Portugal ‘a laundromat for Angola’ and described how one former president of the Portuguese Central Bank said he was told to not look ‘too strict’ at the business deals of Isabel dos Santos.a5534f834339 Isabel dos Santos also owned a 42.5% stake in EuroBic, a privately owned Portuguese bank, via two entities.9a027ea62034 EuroBic was under scrutiny by the Bank of Portugal for processing suspicious payments from Angola.17ef4bd88a41

Step 3: Enjoying illicitly acquired wealth

Once the proceeds of corruption and tax evasion are circulated through multiple companies, bank accounts and jurisdictions, they are directed back into the hands of kleptocrats for them to enjoy.

Law firms

As we have seen, law firms are involved in step 1, and they are also important at this third stage – for example, by representing or supporting their clients in property purchases or investments, or helping to obtain visas or citizenship. Jho Low, a defendant in the 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) scandal, used a DLA Piper bank account in the US to buy a US$200 million interest in the Park Lane Hotel in New York.cb6a4858f3fe The law firm claimed it had no reason to suspect the funds were from proceeds of crime.

Herbert Smith LLP, now Herbert Smith Freehills, was the solicitor for the purchase of two of the properties owned by Dariga Nazarbayeva and Nurali Aliyev (the daughter and grandson of Kazakhstan’s president between 1991 and 2019) that were mentioned in a 2019 unexplained wealth order issued by the UK.b26e8ae0caf7 These properties were suspected to have been purchased with funds from crimes, including corruption, but it is impossible to determine whether the law firm had conducted the necessary and appropriate due diligence.4ccae4138a71

In a similar case, Claudia Sassou-Nguesso, the daughter of the President of the Republic of Congo, is suspected to have embezzled US$20 million in public funds which she may have used, in part, to purchase a luxurious apartment in Manhattan in 2014, worth more than US$7 million.2170e331ad2b According to Global Witness, the law firm K&L Gates LLP was hired to facilitate the acquisition of the property through a company registered at the law firm’s office in New Jersey.77fdf99087fb

Although there is limited evidence from any of the cases we know of that lawyers have been active participants or that they had any suspicion of foul play, the 2015 undercover interviews conducted by Global Witness with 13 law firms in New York provide useful insights. Posing as an adviser to an African minister of mining, Global Witness’s investigator asked how to anonymously move large sums of money that were possibly linked to corruption. Of the 13 law firms, 12 provided advice on how to hide and move the funds as well as purchase assets in the US without being detected.05759554fe23

Real estate agents

Similar to lawyers, real estate agents play an important role in facilitating the purchase of properties with proceeds from corruption, embezzlement of public funds or tax evasion. Real estate agents and notaries often do not verify the origin of the funds used to purchase properties. Global Financial Integrity found that real estate agents were involved in 25% of the money laundering cases in the US and 14% of cases in Canada.4a99b278697c

For example, Francis Selemani, the brother of the former President of DRC, allegedly purchased 17 properties across the US and South Africa with support from real estate agents, despite red flags.a4a90c233f78 Gulnara Karimova, the daughter of the former Uzbek President, reportedly purchased more than US$240 million of real estate around the world.fbc4ab1884f8 Some of the funds were reported to have come from bribes she had received from telecom companies. She had purchased in 2009 a luxury flat in Paris for 30 million euros as well as a castle, Château de Groussay, near Paris, and a villa in Saint-Tropez3e8e8eed6e34ed5a7b27326d She had also bought five properties in the UK worth over 50 million pounds.08d89210e57f She was able to sell two of them in 2013 even though information regarding her involvement in corrupt practices was in the public domain. Real estate agents were involved in either the purchase or sale of these properties.09fd4ad5df08 To the authors’ knowledge, no investigation was opened to determine whether the real estate agents involved in the Karimova case had conducted appropriate due diligence.

Art and the luxury goods industries

Luxury goods like cars, yachts, jewellery, gems and art are highly valued by kleptocrats as ways to enjoy or invest the illicit wealth they acquired. The art and the luxury goods industries do not necessarily ask about the origin of the funds used to purchase goods. For example, in the 1MDB scandal, the US Department of Justice alleges that Jho Low used laundered funds to purchase a yacht, a jet, diamonds, a Claude Monet painting for almost 34 million pounds, and tens of millions of pounds’ worth of artwork from Christie’s and Sotheby’s, including works by Jean-Michel Basquiat, Pablo Picasso and Vincent van Gogh.c5e0e294e2a0 No questions seem to have been asked about the origin of the wealth.

Teodorin Obiang, the vice president of Equatorial Guinea and son of the president, owned 18 luxury cars in France alone, among other high-end items.7b8d99ecba0c In the US, Obiang’s Ferrari and collection of Michael Jackson memorabilia were confiscated while Switzerland confiscated 25 of his luxury cars in 2018.b311e25b8158 In total, Teodorin Obiang spent more than US$200 million on 50 luxury cars such as Ferraris, Maseratis and Lamborghinis with funds from suspicious origin.

Step 4: Improving the kleptocrats’ reputation

As well as purchasing properties, art, cars or yachts to enjoy their illicit wealth, kleptocrats often seek to secure a positive reputation. They will work with a certain type of enabler to acquire a new clean image.85dcaf47c4e4 Charities will list kleptocrats as donors on their website and public relation firms will write glowing profiles, remove critical coverage, and offset any reported controversies. For example, Eliminalia, a Spanish reputation-management firm, is suspected of having helped kleptocrats to ‘erase their past’.1943ad10a0a0 While these organisations are certainly helpful in ‘whitewashing’ damaged reputations, this section focuses on two principal types of enablers that support kleptocrats to improve their image: the education sector and law firms.

Education sector

Kleptocrats will send their children to schools or universities that have an excellent reputation, enabling kleptocrats and their families to develop a network with other powerful families and integrate themselves into the country’s elite and society.e21f85c8064c This is also a way of protecting their social status in their home countries. Education institutions around the world rarely verify the origin of the funds used to pay tuition or make donations. They are therefore exposing themselves to becoming enablers of IFFs.

The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace found that PEPs from Nigeria and Ghana who had been convicted of corruption or had their assets seized by UK courts had sent their children to private boarding schools and universities.96e7d1091781 For example, former Plateau State governor Joshua Dariye was convicted of corruption in Nigeria in 2018. He was still able to send his children to UK boarding schools and universities.3ef902c69d0e The Carnegie Endowment for International Peace also notes that ‘many West African PEPs appear to be using unexplained wealth to pay for UK school and university fees’.5ff3e736aaa5

Law firms

Kleptocrats will hire lawyers to make charitable donations to improve their reputation and be perceived as philanthropists, but the most important role of law firms at this stage is to provide legal advice to launch lawsuits targeting media, journalists, activists, whistleblowers and civil society organisations for defamation or breach of privacy laws. These lawsuits are known as ‘strategic litigation against public participation’ (SLAPP) and their intention is to silence critical voices.a9b038220c21 According to a survey conducted by The Foreign Policy Centre in 2020, 73% of respondents (investigative journalists from 41 countries) had been subject to legal threats.199d767c8b9b The Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE) found 570 SLAPP cases over a ten-year period across Europe.4af695af9b66 Some law firms actually specialise in launching SLAPP lawsuits.

In 2021, Russian oligarch Roman Abramovich, through his lawyers, launched a lawsuit against HarperCollins and journalist Catherine Belton for her book Putin’s People: How the KGB Took Back Russia and then Took on the West. In December 2022, the case was settled without going to trial. Among other terms, the publisher and author agreed to make amendments to the book.1735dde1c858

One US law firm on behalf of the Nazarbayev Fund is suing openDemocracy, the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, the Telegraph and OCCRP after they reported on a fund linked to the former Kazakh President, Nursultan Nazarbayev, and a company registered in the UK.ed08ab8e162d

Enablers seem immune to prosecution

Kleptocrats have been the subject of investigation, have signed agreements (such as guilty pleas) with various judicial systems, or have been convicted. For example, Teodorin Obiang was found guilty in France in 2020 of money laundering and embezzlement of public funds. This conviction was upheld in 2021 by the Court of Cassation, opening the way for the confiscation of his assets in France for an estimated total of 150 million euros.e924305989e6 However, the enablers that have helped the kleptocrats seem to enjoy a relative immunity to prosecution.

Real estate agents, law firms, corporate service providers, and consulting firms have rarely been investigated or prosecuted for their role in kleptocrats’ IFF schemes. However, over the last five years, banks that supported kleptocrats and their money laundering schemes have been on the radar of law enforcement. For example, in December 2022, Danske Bank pleaded guilty because of ‘its deficient anti-money laundering systems’ allowing ‘billions of dollars of suspicious and criminal funds through the U.S. financial system’.8f5a0e372ad2 The bank agreed to forfeit US$2 billion to resolve the US investigation. Credit Suisse agreed in 2021 to pay US$547 million to resolve charges in the US and the UK for its role in the ‘hidden debt’ scandal in Mozambique. The bank had ignored red flags and corruption risks.f98b133f5931 BNP Paribas was indicted for money laundering and embezzlement of public funds in May 2021 for its role in the Biens mal acquis (‘ill-gotten gains’) case, related to the family of Omar Bongo, the former president of Gabon.38a998a32a5f We are yet to see lawyers, real estate agents, art dealers or the yacht industry under the same scrutiny.

Donor countries are home to enablers: Examples from the US, Switzerland and the UK

Enablers based in OECD countries have often played a role in the cases mentioned in this U4 Issue (and in the literature mentioned in the reference list). This results in a dichotomy: on the one hand, OECD countries are some of the main providers of official development assistance (ODA), supporting capacity building in developing countries to counter IFFs, while on the other hand, the enablers based in their countries play a significant role in enabling IFFs.

This section explores the role of three OECD countries in enabling IFFs: the US, Switzerland and the UK. The UK and US were responsible for 40% of all money laundering in the 38 OECD countries.7227d800a199 In addition, Tax Justice Network’s 2022 Financial Secrecy Index (which assesses how a country’s financial and legal system enables the hiding and laundering of money) ranked the US as the number one most secretive out of 141 jurisdictions. The country enabled ‘the biggest supply of financial secrecy ever recorded by the index’.5578dd3fdb47 Switzerland is the second most secretive jurisdiction (since 2018, the country has been ranked in the top three) and the UK was ranked 13. However, the level of secrecy within the UK has increased since 2018 (when it ranked 23). Some of the British overseas territories and Crown dependencies (British Virgin Islands, Guernsey, Cayman Islands, Jersey) are also in the top 20 most secretive jurisdictions.

United States

The Financial Action Task Force (FATF) regularly assesses countries’ compliance with their Anti-Money Laundering and Counter Financing of Terrorism standards.7fe170f5600c Two FATF standards (Recommendations 22 and 23) apply to enablers. At the time of the last FATF assessment in 2020, the US was rated ‘not compliant’ with the enablers standards, the lowest possible score.705354f762e9b32ff154cf8d

Enablers based in the US appeared in multiple IFF-related cases. For example, Global Financial Integrity found that, between 2015 and 2020, more than US$2.3 billion was laundered through US real estate.bbaafdeeaa09 Law firms and real estate agents were the main types of enablers involved. In the Pandora Papers, 206 US-based trusts linked to 41 countries, holding combined assets worth more than US$1 billion, were identified. South Dakota is the lead provider of secrecy and concealment services followed by Florida, Delaware, Texas and Nevada.c75630e32617

While the US blocked in 2022 certain enablers from supporting Russia with company formation, accounting and consulting services, their services remain available to possible illicit actors in other countries.51985be690ff A bill to increase transparency, called the ENABLERS Act, was introduced into the legislative process. It required enablers such as corporate service providers, lawyers, art dealers and accountants to conduct a due diligence process on their clients, their assets and the source of the funds.6cc87de004ef It was blocked by the Senate in December 2022.

Switzerland

In 2020, FATF assessed Switzerland’s regulation on enablers as ‘partially compliant’, the second lowest score.68547fce993c The Pandora Papers contained information on 90 Swiss advisers: legal, notary and consulting firms.5b65b71925ae From 2005 to 2016, at least 26 Swiss firms mentioned in the Pandora Papers provided services ‘to clients whose offshore companies were later investigated by authorities looking for evidence of money laundering and other financial crimes’.59d58b5a0aff These firms acted as intermediaries, connecting clients with offshore service providers.7d3346a8305e Thirty-three thousand ‘letter box’ companies registered in the cantons of Geneva, Zug, Fribourg and Ticino were found to be involved in suspicious transactions linked to corruption and money laundering.d29f2d0d78e6 In Zug, 6,300 of these companies are registered in buildings in which law firms and fiduciary offices conduct their business.b4db1730e3d8

A law strengthening the anti-money laundering requirements for enablers, including for lawyers and notaries, was discussed in the Swiss parliament but was rejected in 2021. However, the Federal Council is working on new provisions.3acac0987c66

United Kingdom

After the invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 by Russia, the UK House of Commons, reporting on illicit finance and the war in Ukraine, indicated that ‘the ignominious role that London and the Crown Dependencies and Overseas Territories (OTs) have played in undermining the integrity of our institutions and financial systems, as well as the UK’s international relationships, is no secret’.dbca5468f831

Enablers based in the UK have featured prominently in multiple cases and investigations conducted by journalists, non-governmental organisations and researchers. For example, in 2019 Transparency International UK identified 86 financial institutions, 81 law firms and 62 accountancy firms based in the UK that helped, whether knowingly or unknowingly, acquire assets from suspicious wealth. Assets included 421 properties worth 5 billion pounds, 7 luxury jets worth around 170 million pounds and 3 luxury yachts worth around 237 million pounds.9bf53c8806a7 In 2023, Transparency International UK found that 6.7 billion pounds’ worth of UK property was purchased with suspicious funds, of which 1.5 billion pounds’ worth was purchased by Russians subject to sanctions and with ties to the Kremlin.591e1286002f Most of these properties were held via secretive offshore companies.

The UK is also a haven for SLAPPs, with more SLAPP lawsuits there than in any other country other than the journalists’ home countries. Its legal and judicial system make it particularly attractive for this kind of litigation because the burden of proof is on the defendant, the legal costs are high, and the process to reach trial is lengthy.d0f1ba243915

The Economic Crime (Transparency and Enforcement) Act, adopted in 2022, will counter some of these issues. It requires overseas entities that own or wish to own property in the UK (and the enablers providing them with services) to identify their beneficial owner. It applies retrospectively to property bought by overseas owners up to 20 years ago in England and Wales and since December 2014 in Scotland. Despite the new law requiring companies to register their beneficial owners by 31 January 2023, more than 18,000 companies ‘have either ignored the law altogether or submitted information which makes it impossible for the public to find out who owns them’.5e0f6f5afab8

As the cases highlighted in this Issue show, enablers based in other OECD countries, such as Canada or France, facilitate IFFs. Although OECD countries’ role is essential, enablers based in non-OECD countries are also involved. For example, in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates, real estate agents and property developers were found to accept suspicious funds from PEPs to purchase properties.e6e83f5991bf Kleptocrats in Africa have also been buying real estate in Kenya, South Africa or Uganda with unexplained wealth.36a7e0b015fb

Recommendations

The steps, methods and channels of IFFs are ever changing as kleptocrats stay one step ahead of law enforcement. Hence, the above-mentioned enablers might only cover some of the currently used and known methods. That also means that policies, laws and law enforcement actions need to be continuously adapted. The following recommendations for the governments of donor countries are targeted at disrupting the enablers based in the donor countries supporting kleptocrats.

Recommendations for governments of U4 Partners and donor countries

Update relevant laws and policies:

- Conduct a national IFFs threat assessment to determine the enablers at risk of supporting kleptocrats and propose adequate mitigation measures.

- Close loopholes that allow foreign companies to purchase assets without identifying their beneficial owners.

- Establish a free public central register of wealth and assets and their beneficial owners.357d888dc511

- Ensure compliance with the FATF recommendations, especially for enablers (recommendations 22 and 23).

- Expand or consolidate anti-money laundering regulation, including due diligence and suspicious transaction reporting requirements, to unregulated or not well-regulated enablers such as auction houses, luxury car dealers, art industry and universities.

- Require due diligence of all transactions and services involving domestic and foreign state-owned enterprises and government officials.

- Continuously monitor money laundering trends and design appropriate countermeasures for new technologies or emerging channels including cryptocurrencies and mobile money providers.

- Introduce penalties for enablers (eg, deterrent administrative or criminal penalties, disqualification, lifting professional privilege in specific conditions).

- Ban services provided by enablers to individuals and companies under sanctions.

- Adopt anti-SLAPP provisions or legislation to ensure the judicial system is not abused to silence journalists, civil society and whistleblowers reporting on IFFs.

Improve accountability measures:

- Work with professional bodies and associations to develop or strengthen ethical rules and their corporate social responsibility, and to support training programmes for key enablers (eg, art industry, real estate agents) on the risks of IFFs and their role.

- Develop public-private partnerships at the domestic and international level to exchange information on IFFs and enablers (including typologies) and on how kleptocrats exploit the legal and financial systems.

- Prevent corruption and looting of provided aid through robust accountability measures for aid programmes and include consequences for when aid does go missing.

- Develop guidelines blocking access to aid programmes for military-linked companies and for economic interests connected with government officials, their family members and friends.

- Coordinate and streamline accountability measures with other aid providers, donor countries and (international) financial institutions.

- Support domestic governance and rule of law programmes; support civil society’s capacity to investigate the role of enablers; and support whistleblower protection mechanisms.

- Work with European financial institutions to increase scrutiny of transactions stemming from known high-risk jurisdictions, according to the EU’s list of High Risk Third Countries for AML/CFT (anti-money laundering/combating the financing of terrorism) and the FATF grey and black lists.

Increase enforcement:

- Raise awareness of the role of enablers among law enforcement agencies and work with law enforcement to identify legal obstacles that could prevent them from investigating enablers.

- Set up a task force team from different government institutions to ensure coordination (eg, similar to task forces put in place to trace assets from Russians under sanctions).

- Adequately resource law enforcement agencies.

- Systematically investigate the role and modus operandi of enablers and prosecute them as necessary.

- Foster cross-border data sharing between competent authorities to follow IFFs across borders.

- US Department of Justice 2022a.

- NBC News 2022.

- Herbert Chang et al. 2023.

- Herbert Chang et al. 2023.

- US Department of the Treasury, 2022a.

- Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office 2022.

- In this Issue, IFFs are understood as ‘financial flows that are illicit in origin, transfer or use, that reflect an exchange of value and that cross country borders’ (eg, corruption, tax evasion and tax avoidance, money laundering) (UNCTAD and UNDOC 2021). An introduction to illicit financial flows can be found in the U4 Basic Guide.

- See the references section for a full list of relevant resources.

- Definition proposed by Heathershaw et al. 2021.

- Hallman et al. 2020.

- Hallman et al. 2020.

- Hallman et al. 2020.

- Hallman et al. 2020.

- Harding 2016.

- ICIJ 2017.

- Financial Times 2018.

- Pegg et al. 2022.

- OCCRP 2022.

- The Sentry 2022.

- International Forum for Democratic Studies 2023.

- BBC 2020.

- Transparency International Portugal 2020.

- US Department of Justice 2017.

- Customer due diligence and record-keeping requirements (as outlined in Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations 10, 11, 12, 15, and 17) apply to legal professionals in specific cases including when creating or managing companies, managing clients’ money and assets, or buying and selling real estate (FATF 2012).

- Heathershaw et al. 2021.

- Global Witness 2019.

- Global Witness 2019.

- Global Witness 2016.

- Kumar and de Bel 2021.

- In 2019, Gulnara Karimova signed a guilty plea with the French financial prosecutor and her assets were confiscated. US$10 million were returned to Uzbekistan in May 2020.

- The Sentry 2022.

- Freedom for Eurasia 2023.

- RFI 2019.

- Freedom for Eurasia 2023.

- Freedom for Eurasia 2023.

- US Department of Justice 2021.

- RFI 2017.

- Agence France-Presse 2020.

- Heathershaw 2021.

- OCCRP 2023.

- Transparency International UK 2019.

- Page 2021.

- Page 2021.

- Page 2021.

- Lemaître 2021.

- Coughtrie and Ogier 2020.

- CASE 2022.

- The Foreign Policy Centre 2023.

- Williams 2022.

- Transparency International France 2021.

- US Department of Justice 2022b.

- US Department of Justice 2021.

- TV5 Monde 2021.

- Ferwerda et al. 2020.

- Tax Justice Network 2022.

- The FATF uses four levels of compliance: compliant, largely compliant, partially compliant and non-compliant.

- FATF 2022.

- FATF 2020b.

- Kumar and de Bel 2021.

- Fitzgibbon et al. 2021.

- US Department of the Treasury 2022a.

- US Congress 2021.

- FATF, 2020a.

- Alecci 2022.

- Alecci 2022.

- Alecci 2022.

- Budry Carbó and Moret 2021.

- Regenass and Budry Carbó 2021.

- swissinfo.ch 2023.

- Foreign Affairs Committee 2022.

- Transparency International UK 2019.

- Transparency International UK 2023.

- Coughtrie and Ogier 2020.

- Transparency International UK 2023.

- Page 2020; Page and Vittori 2020.

- The Sentry 2020.

- In November 2022 the Court of Justice of the European Union ruled that public access to beneficial ownership registers interfered with the right to respect for private life and to the protection of personal data. However, the Court opened the door for special access for those that have a legitimate interest, including civil society and journalists involved in the prevention of money laundering and its predicate offences. Discussions at the EU level regarding the revised AML framework are ongoing to determine who can be considered to have a ‘legitimate interest’ (eg, allowing access to foreign competent authorities) and the modalities to access the registry to avoid demonstrating legitimate interest on a case-by-case basis.