Foggy progress in IFF

The IFF agenda has made great strides. Over the last decade or so, the problems caused by IFF and the policy choices needed to curb IFF have been receiving increasing attention from world leaders. The issue has maintained a high profile, as evidenced by the advocacy put forward in the High-Level Panel Report (also known as the Mbeki Report); the aspirational commitments made in the Addis Ababa Action Agenda (AAAA) for financing for development; IFF’s inclusion in the ambitious goals and targets set in the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and the support from G20 leaders (High-Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, 2015; United Nations, 2015a, 2015b; G20, 2016).

There is now consensus that IFF have wide-ranging adverse consequences for developing countries’ economic management, growth and development, making it a priority on the development agenda. There is also consensus that both national and international actions are needed to curb IFF (UNODC, undated and OECD, 2016). Countries are increasingly coming together to encourage policy measures that are directly linked to domestic resource mobilisation (DRM) and preventing their loss through IFF. Preventive measures at the international level include the promotion of tax information exchange, sharing of tax enforcement skills, beneficial ownership registries for legal entities, and asset recovery of stolen or illegally transferred assets. There are also measures to discourage secrecy regulations, tax havens, money laundering and terrorist financing, as well as transnational organised crime, trafficking and corruption.

Further steps are in prospect, even perhaps in time rising to the ambitious standards of the coherent, ‘whole-of-government’ coordinated policy actions at both national and international levels that the OECD has envisioned (as a challenge) (OECD, 2016). There seems to be a general convergence in the thinking about what needs to be done to curb IFF. This convergence in thinking is reflected in the OECD’s and the World Bank’s recent thought leadership on countering IFF.

The OECD (2016) provides a framework and self-screening tool for countries to help plan for, avoid, or resolve several key trade-offs or policy inconsistencies and apply existing international standards effectively. The OECD is leading several programs related to tax and other activities critical to the IFF agenda. Coherence and a whole-of-government approach in each country and internationally are essential to successfully containing IFF.

The World Bank (2016) has summarised the panoply of operations that the World Bank and/or other international agencies support or undertake with relevance to curbing IFF. These range from better understanding IFF, to partnering with the United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime (UNODC)on the Stolen Asset Recovery Initiative (StAR), and helping countries and practitioners recover stolen assets.

In both sets of contributions, there is a sense that policies for specific purposes that were previously unconnected are being brought together in the new policy agenda for countering IFF (World Bank, 2016). Nevertheless, although the IFF agenda may have highlighted many problems, it is certainly not without its own problems.

The problems of IFF

Fair attribution would credit much of the success in creating the IFF agenda to pioneering research and advocacy. Kar, Baker, and Cardamone (summarised in 2015a) provided crucial advocacy research that highlighted potential magnitudes of IFF from developing countries, while speculating about the potential development gains that could have been made without the loss of resources due to IFF. The capital flight research performed by Ndikumana and Boyce was similarly important. However, indications have emerged that there are some significant problems that may derail the implementation of coming phases of the IFF agenda.

The ability to move from public awareness of the issues to actually doing something about them has been hampered by vagueness about the component causes and consequences that has arisen from and continues to spill over into the definition of IFF itself. Similarly to the aggregate definition of ‘corruption’, there is a considerable lack of precision in the definition of IFF. This has direct effects on efforts to identify IFF, estimate their volumes, determine their drivers, prioritise focus, and establish the effectiveness of anti-IFF measures at various levels.

The definitional problems will impede progress in the UN SDG process to develop a measurable indicator for IFF.The SDG target referring to IFF is Target 16.4: “By 2030, significantly reduce illicit financial and arms flows, strengthen the recovery and return of stolen assets and combat all forms of organized crime”(UN, 2015a). The specific indicator for IFF (Target 16.4.1) is the “total value of inward and outward illicit financial flows.” The indicator for IFF has been classified as one of a limited number of ‘Tier III’ items by the Inter-Agency Expert Group on SDG Indicators (IAEG-SDG). This means the proposed indicator lacks an established methodology or standard, both of which are being developed and tested. The IAEG-SDG has sought assistance from the UNODC and the United Nations Committee for Trade and Development (UNCTAD) as custodian agencies in developing the IFF indicator. These agencies have commenced their deliberations to arrive at an agreed methodology, a task that may take two years or more and involve pilot projects and testing. Obviously, if not resolved, the opportunity for consistent tracking of IFF on a country-by-country basis against the target in this development round could be lost. Meanwhile, delays lead to uncertainty and confusion.

The research base for the estimation of IFF that has underpinned the global agenda has come under pressure. Demand for analysis to inform policy approach and design has been rising. But the approaches to estimation used by many of the leading IFF or capital flight research teams, such as Global Financial Integrity and Ndikumana and Boyce (henceforth GFI and N&B), appear not to have been picked up in the IAEG-SDG process and have proven hard to relate to the IFF problems seen in individual countries.

There have only been a few recently published papers and notes addressing the issues relating to the methodologies deployed thus far in the estimation of However, the disquiet over the methodological problems is present whenever IFF researchers confer. Little seems to have improved since the World Bank’s seminal Draining Development publication.077f59329ed4 Nitsch finds some prominent estimates of total IFF and one component, trade misinvoicing, to be meaningless and a matter of faith.0063b5de174e Forstater has worked through errors in some trade misinvoicing studies and worries that the approaches used by the leading research teams create a distraction for future, hopefully more useful, IFF research.efe6e0d468d7 As a result, where they can, some, especially country researchers, are beginning to bypass the methodologies that have previously been deployed.

Soundly formed estimates are important for understanding the significance of the IFF problem and for prioritisation. When the IFF agenda was still in its relative infancy, Fontana correctly stated the deeply felt suspicion that what cannot be measured cannot be managed.d2eca5775341 But it could well be that the conceptual foundations and initial analysis underpinning the IFF agenda have been put together in too much haste, rather than being the outcome of meticulous research and lengthy reflections on various policy influences.

Another problem is the linkages between the IFF agenda and the anti-corruption agenda. Corruption and IFF are not synonymous. As greater understanding of IFF at the country level emerges, it will become clearer that only some IFF stem from corruption, though corruption plays a direct or facilitative role in many IFF and types of IFF. This has been clear for some time, both from research and observations on the potential interaction between corruption, smuggling, and capital export under a repressed exchange rate regime, eg May (1985).

Furthermore, whereas anti-corruption policies and programmes of many varieties are suggested by various national and international NGOs, INGOs as well as international intergovernmental organisations (IGOs) for all countries, including those affected by IFF, few of these policies and programmes are targeted specifically at addressing IFF. This paper suggests that anti-corruption policies need to consider the relationship between IFF and corruption if anti-corruption efforts are to contribute to curbing IFF. Corruption threatens all the preconditions for curbing IFF, but also the effectiveness of most of the general remedies to IFF.497780ae1cb1 However, as the role of corruption in relation to the various aspects of IFF has not been properly explored, discussion of how anti-corruption efforts can help address IFF is largely missing.

In countries with high corruption risk environments (systemic corruption) that represent non-universalistic governance regimes with weak rule of law, progress on curbing IFF as well as curbing corruption seems likely to be a long haul.650c4ec5ea83 Still, the understanding of how to make a transition from such governance regime types is slowly emerging while exposing many flawed assumptions of previous policies ignorant of the relevance of regime type factors and dynamics (Ibid). The establishment of an international environment where IFF drivers and facilitators are identified and curbed, albeit offshore, can assist in compensating for the weak prospects of improving governance in such adverse environments. In many cases the likelihood of effective change based on the standard anti-corruption and anti-IFF remedies is slim before there is a shift in governance regime type. At the international level, it also remains an open question whether the political economy of needed change will also make it possible.e4a13d7d6bf5

Nevertheless, in line with the central anti-IFF policy proposals, we need to ask if there is more that can be done in-country and internationally in a complementary manner, given the many obstacles to changing identified drivers and facilitators of IFF. The anti-IFF agenda still has a long way to go before a realistic and context-specific agenda, taking both country and international level contexts into consideration, can emerge.

The opportunity to refocus

This ‘shaking of the foundations’ is occurring at a critical juncture as the agenda’s research focus on volume estimates at a global or continental level is now shifting and expanding towards more detailed and robust single country, regional, and industry studies of how to prevent IFF at those lower levels. For instance, country studies generally are intended to identify, with specific country-relevant and industry-relevant understanding, the types of IFF, the types of players involved, the channels used, and the drivers and facilitators. These studies also seek to identify effective country-specific policies to curb IFF. It is important for the next stage of the IFF agenda that these country and industry studies draw on the firmest possible research foundation.

Compared to the number of UN member countries, until now there have been only a handful of IFF country studies, and fewer still have been published.46ab468f51b7 Many more will be needed if all UN countries are to progress toward the IFF target between 2015 and 2030. These problems and pressures create an opportunity – indeed, an imperative – to re-focus, so that the IFF agenda move forward with greatest effect, to have a material impact on curbing IFF across the widest possible range of countries.

Outline of the paper by sections

- Weaknesses in the IFF foundation details the pressure on the foundations of the IFF agenda, notably the lack of clarity in the definition of IFF and the weaknesses of the approaches most often taken in global and multi-country studies to estimate the amount of IFF.

- Estimations of IFF sets out some thoughts on how the issues in section of weaknesses might be addressed more constructively.

- The role of corruption in IFF reviews and expands the understanding of the role of corruption in IFF.

- Practical approaches and country level discusses some critical and practical proposals at the country level intended to advance the IFF agenda at that level.

- Recommendations presents policy recommendations.

Weaknesses in the IFF foundations

The IFF agenda is a complex yet young subject, involving several multi-disciplinary strands that have to combine to find effective ways forward. It involves issues that often have been treated as distinct or unrelated:

- fiscal policy and taxation

- balance of payments (BoP) accounting and trade statistics

- financial sector capabilities and inclusion

- anti-money laundering and countering of terrorist financing (AML/CFT)

- technology

- exchange controls and exchange rate regimes

- criminology, intelligence and the judicial process

- industry policy

- property rights and real estate

- national and international law

- international cooperation and assistance.

Understanding in all these fields will be necessary in order to construct a firm research foundation. There have been attempts to achieve greater rigor and effectiveness within the IFF agenda as it has progressed. For instance, a 2011 U4 Issue attempted to clarify the links between IFF and corruption, and how corruption may be controlled by stemming such flows.b409d295b0f7 It recommended a more evidence-based approach to tackling IFF, which considers the costs and benefits of policy choices. It also advocated going beyond then-prevalent reliance on anti-money laundering (AML) policies to embrace more fully other policies to counter IFF. These included good governance reforms to address corruption as a source of illicit funds and more decisive efforts by rich countries to reduce support for havens that facilitate secrecy and shelter the proceeds of grand corruption.

There has been some progress since 2011 in the range of policy actions being deployed to counter IFF, especially at an international cooperative level. While there will be more to come at the international level, there has also has been a lack of progress elsewhere. The problem that has received the least attention is the lack of understanding of the concept IFF.

Defining IFF

Some activists as well as researchers have expressed concern that critiquing the very definition of IFF itself risks undermining the progress made to date in seeing the relationship that various facilitating factors, dynamics, and actors at both national and international levels play in the loss of domestic tax revenues as well as in various domestic and international criminal activities. However, lack of precision in language undermines the ability to identify the scope of a problem, and in this case the definition fails to address key aspects of IFF. While the concern about undermining progress may be justified, it is also not clear what progress it would be undermining. There is little reason to expect any effective improvements the fight against IFF when policies only address a part of the problem, or when actual effects cannot be measured because the methodology does not accurately measure the problem in the first place, or only measures part of it. A separate question concerns the role of research relative to activism, when the full contours of the relationship between the two that may not always be clear.

The definition advanced by Global Financial Integrity (GFI) has been that IFF are “illegal movements of money or capital from one country to another. GFI classifies this movement as an illicit flow when the funds are illegally earned, transferred, and/or utilized.”e7efd594aeb0 To provide context to this definition, it is common to identify particular international transfers or activities as instances of IFF. For instance, the Mbeki Report (High-Level Panel, 2015) elaborates that these funds typically originate from three sources:

- Commercial tax evasion, trade misinvoicing and abusive transfer pricing;

- Criminal activities, including the drug trade, human trafficking, illegal arms dealing, and smuggling of contraband; and

- Bribery and theft by corrupt government officials.

There have been many attempts to provide further detail to these high-level, rather conceptual and descriptive definitions. On one hand, the OECD at one stage broadly defined illicit financial flows as any financial flows “… generated by methods, practices and crimes aiming to transfer financial capital out of a country in contravention of national or international laws.”f3228d16da8a On the other hand, the World Bank (2016) describes IFF as falling into three main areas, without clarifying their relationships to the definition:

- Acts: The acts themselves are illegal (eg corruption, tax evasion); orSource of funds: The funds are the results of illegal acts (eg smuggling and trafficking in minerals, wildlife, drugs, and people); or

- Use of funds: The funds are used for illegal purposes (eg financing of organised crime).

Clarity of the concept, ie a clear definition of IFF, is directly relevant for identifying IFF in-country and subsequently how to address them. The definition also matters for estimating the volume of IFF: only flows that qualify according to the definition should be included. Finally, the definition also plays a direct role in assessing the effects of anti-IFF measures on the various components of IFF. Such assessments depend on having a definition that directly or indirectly can help identify the relevant components.

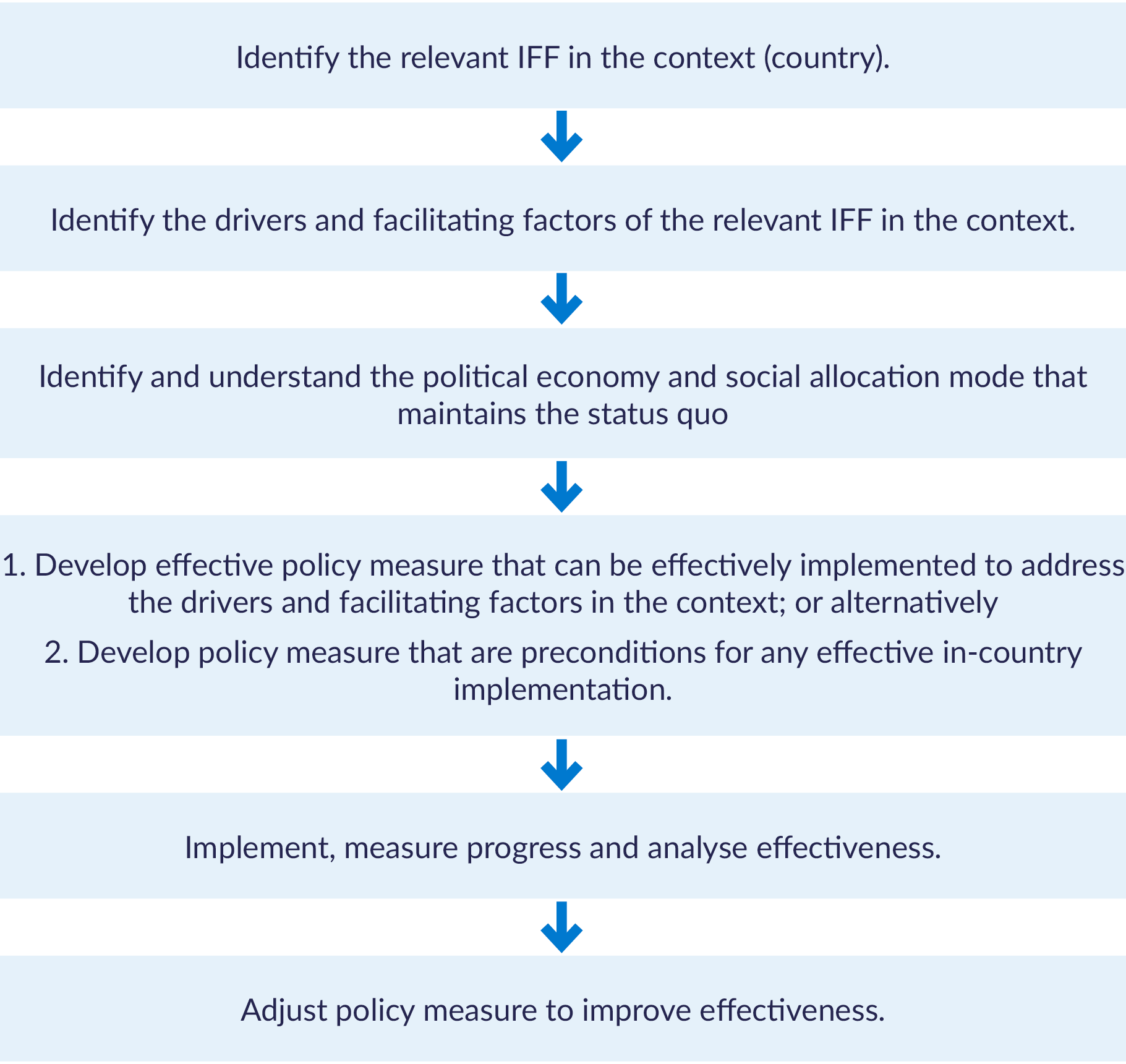

A very simple logic for the process of identifying country-level anti-IFF policies is outlined in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The process for identifying in-country anti-IFF policy measures.

Although straightforward, that simple logic depends on a clear definition. Unfortunately, the definition of IFF has never been completely settled, despite the fact that the definition has a material impact on what is to be described, estimated, analysed and ultimately addressed through policies. The identified sources of IFF are of course relevant, but they are in no way sufficient to identify when IFF exist. What the typical attempts at definition loosely suggest is also that the actual movement of money across a border can represent a criminal offence/illegal act. Finally, these typical definitions also suggest that illegal use of any cross-border flows also qualify them as IFF, regardless of whether the source or the transfer is itself illegal. Unfortunately, these examples of interpretations do not help improve the precision of the definition as needed for qualitative in-country studies. As has been suggested elsewhere, the definition of IFF is “marred by a lack of terminological clarity, which somewhat limits the emergence of effective policy options.”def403977fd6

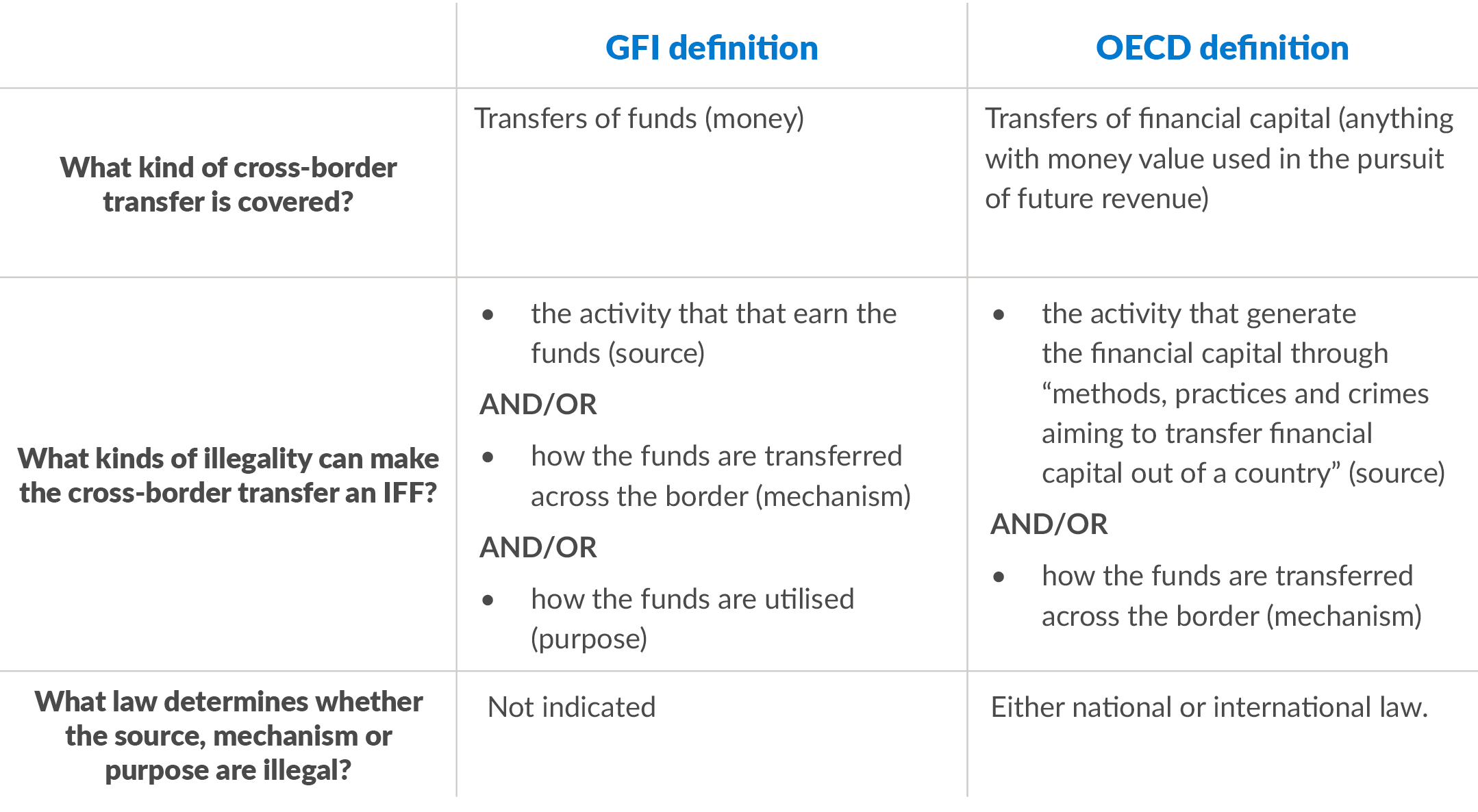

Comparing the GFI-definition to the OECD-definition provides some interesting differences. The GFI-definition appears to imply that either the cross-border flow of money is qualified as IFF due to its illegal source, or due to the fact that the cross-border flow is illegal, or because the cross-border flow is used for anything illegal. Under this definition, to identify IFF it is first necessary to investigate each cross-border flow (recorded or not) to determine whether any element of the GFI definition is present that qualifies it as IFF (see Figure 2 below).

The IFF qualification criteria in the OECD definition present several ambiguities. To define IFF as “generated by methods, practices” obscures what type of activity that is involved. Here it is not possible to identify whether the qualification of IFF has to do with the nature of the activity that is the source of the financial capital, or if it concerns the mechanism used for cross border transfer of financial capital. Both activities and transfer mechanisms can be illegal according to the OECD definition, but it is not clear if there is a distinction between source activity and transfer mechanism. Nor is it clear what else is covered by ‘methods’ or ‘practices’ that are illegal, particularly as there is no reference to any specific legal source.

That separation between source activity and transfer mechanism should however be possible to make when the illicit financial capital has been generated through a criminal offence, which the OECD definition makes reference to. Due to the demands for legal safety, criminal offences must be very precise as to how they are defined. To be able to separate between the source activities and the transfer mechanism following the OECD definition, dividing the definition into three elements similar to a criminal offence may help analyse the value of the definition from a precision perspective (OECD definition reference within quotes):

- “[F]inancial capital generated by methods, practices and crimes” (source activities generate financial capital), and;

- That have as an “[aim] to transfer financial capital out of a country” (intent to attempt a transfer, or the completed transfer, of capital out of a country), and;

- The concerned transfer is “in contravention of national or international laws” (illegal status of the transfer mechanism or of the use of transferred financial capital in transfer origin country, in transfer recipient country, or in any transfer transit country, or due to international law).

Element 1 does not imply that the source activity has to be illegal, except when it concerns crimes. Nor does it say anything about what specific activities that generate the financial capital in question, ie the source can be any activity that forms part of some methods or practices that aim to transfer financial capital out of a country. It also says nothing about where those activities have to take place, which means they can occur anywhere, although element 3 relates to laws that can only be valid when certain conditions are met, such as within a certain territory. Also, there are ambiguities to the applicability of the definition as it does not identify a legal or physical person as the agent that has an aim to transfer financial capital across the border. Instead, it is the ‘methods, practices and crimes’ that aim to do that. A criminal offence that aims to do that should not be a problem as qualified subjects are always defined in criminal law to determine its applicability. But ‘methods and practices’ in element 1 seem to refer to some combination of human activity, technology and process that result, or attempt to result, in a cross-border transfer of financial capital.

When the qualification of IFF depends on the illegality of ‘methods and practices’ it is crucial that its components are defined so they can be identified. Due to the reference to illegality in element 3, it appears these methods and practices must be identified by reference to the valid laws of each single country. Alternatively, if the qualification of IFF does not depend on the illegality of ‘methods and practices,’ it will instead be important to be able to distinguish illegal cross-border transfers of financial capital in each country.

Element 2 depends on an interpretation of the meaning of the term ‘aim.’ Firstly, to aim for some specific result when doing or using something, such as an illegal transfer mechanism to transfer financial capital across the border (as defined in element 3), can relate to so called ‘criminal intent’ in relation to the completion of a criminal act. In this case it could also be extended to other illegal acts, ie not only criminal acts. Another possible interpretation is that it relates to an attempt and not the completion of the use of a criminal/illegal transfer mechanism to transfer financial capital across the border, which can be criminal/illegal because of the intended use of financial capital or because of the type of transfer mechanism itself (as defined in element 3).

However, if it concerns a criminal attempt, that does not suffice on its own. Any reference to a criminal attempt needs a criminal offence to refer to, which is only indirectly offered in element 3. Element 3 refers to what some unspecified existing laws stipulate as legal or illegal. When we look at IFF as a criminal offence, it would need to be manifested in domestic criminal laws. Element 3 is fully possible as an element in a criminal offence should it be precise, although few countries refer to international law in their criminal codes. Rather, they seek to incorporate international law commitments into domestic law to make it comply with its domestic validation rules for law (promulgation rules). As this third element now stands, it seems to refer to criminal offences on international money laundering and terrorist financing.

The meaning of the attempted financial capital transfers referred to in the OECD definition of IFF will depend entirely on what valid criminal law in a certain country qualifies as criminal, ie the transfer mechanism itself or the intended use of the financial capital making the transfer criminal, or both. Also the open questions in element 1 and 2 ought to be answered in criminal law: what the specific activities are, where they need to occur and by whom committed (to determine jurisdiction), within what time, what elements that need to be present for a crime to have been committed, and how the various elements need to be covered by subjective intent. Due to the level of precision in criminal law, the distinction between various acts and the transfer mechanisms in ‘methods and practices’ would be likely be clear. An unresolved problem with element 3 is that it refers to illegality, which could cover many other acts and transfer mechanisms than those in criminal offences alone. The questions relating to lack of precision remain.

This analysis using a criminal offence perspective to precision has limitations in relation to the wider definition. It suggests that the OECD definition simply stresses the importance of identifying and preventing attempts at already illegal cross-border transfers of financial capital according to unspecified national or international laws. To refer to the OECD definition as proscribing a criminal offence is of little, if any, value.

It is possible there is some implicit assumption that the OECD definition would capture a chain of flows that is illegal in each step that would consist of incomes from illegal or criminal activities (source activity), and illegal or criminal cross border transfer/s (transfer mechanism).b0c97b4bd7c2 Alternatively, there is a chain of flows with partial illegality or criminality, in which either the source activity or the transfer mechanism is illegal or criminal. Unlike under the GFI definition, the eventual use of the transferred financial capital does not immediately appear relevant to qualify an IFF according to the OECD definition. However, it is also possible that a transfer of financial capital can qualify as illegal or criminal if the intended use of the financial capital after transfer is illegal or criminal. The implied assumptions are not clear.

For anyone trying to establish the prevalence of IFF defined in these ways, there are subsequently a wide range of factors that need to be identified (see Table 1 below).

Table 1. Comparison of IFF-qualification criteria in the GFI and OECD IFF definitions. Source: Eriksson, 2017a

How do these different definitions matter for identifying the relevant IFF in a specific developing country context? From a practical perspective, there are major differences between them. The first difference concerns the source for defining when a qualifying factor is deemed illegal or not. In the OECD definition, reference needs to be made to international law as well as national law. GFI does not mention the source of law. The second difference concerns the need in the OECD definition to qualify methods, practices and crimes that contribute to generating financial capital for which there is an aim to make an illegal transfer across a border. It is unclear how to define that aim and subsequently to know when it exists. Is it defined by establishing objective factors that amount to an ‘aim’? Or, does it relate to a subjectively qualified ‘aim’, as required for ‘subjective criminal intent’ in relation to the completion of a criminal offence? In the case of the OECD definition, it could also be extended to other illegal acts, ie not only criminal acts. As suggested above, it could also relate to an attempt and not the completion of the use of a criminal/illegal transfer mechanism. Without knowing when that aim exists, it is not possible to identify the existence of IFF by choosing one, two or all three interpretations. However, each choice will produce very different results from the other ones. These sets of differences can be expected to result in considerable divergences when seeking to identify context-specific IFF and therefore also the targeted policies to prevent it.f20f3c40c543

As suggested above, the identification of the context-specific IFF are likely to differ considerably depending on the interpretation of the uncertainties contained in the definitions. In the OECD definition, it is not clear whether ‘practices and methods’ have to be illegal or not. If they have to be illegal, it is unclear what contribution to such generation is enough to qualify a method and/or a practice as illegal. That difference alone will have an effect on the identification as well as the volume of IFF. Also, if methods and practices that contribute to generate the cross-border transfer have to be illegal, it appears neither the status of the recipient nor the use of a cross-border transfer matters for identifying the relevant IFF in a specific developing country context. That would take away flows of legally generated revenues, transferred via legal mechanisms, received by terrorists, or used to fund terrorism, human trafficking or other forms of international organised crime, from being included in IFF. Due to the persistent existence of secrecy in the global financial system, created and protected by nation states, coupled with the ease of using highly complex transaction structures, there is little reason to believe that only illegally earned money is the sole relevant source of funding for illegal activities.947329de09ec

Identifying and accessing information to identify IFF

The consequences suggested above are primarily based on a theoretical analysis of the definitions. The more practical issue concerns how to identify and access information about cross-border transfers of financial capital and about the factors that qualify them as IFF in a specific developing country. The barriers to identifying and accessing information about qualifying factors create immense difficulties regarding reliable identification and measurement.

Only a small percentage of illegal acts (civil, administrative/public and criminal) are detected and reported. For criminal offences, an even smaller number end up with convictions, which offers the only confirmed instances of criminal activity.14d78cf5d2a4 The same applies to illegal behaviour according to civil law or administrative/public law. The few instances confirmed as illegal can be found by looking at civil law judgments and cases of recorded regulatory and administrative breaches. But what about all illegal and criminal acts that cannot be found in public records, but that are linked to a cross-border flow? Public records would not always record the linkage to a cross-border flow (or the value of it).

Another issue concerns how to establish legality/illegality by looking at the status of a recipient of a cross-border transaction. Should that illegal recipient only be identified as the first recipient of a cross-border transfer or as a recipient further down a chain of transfers, even if only a part of the original cross-border transfer reaches that prohibited recipient? Similar problems of where to stop in the transaction chain arise when trying to establish the legality or illegality of the use of such a transaction.

As suggested above, besides deciding where a cross-border transfer ends, it will also be necessary to access foreign public data on illegal acts (civil, administrative/public and criminal) that can be matched with the cross-border transfers.

However, as the cross-border transfers also may be illegal themselves, the publicly available data on all legal cross-border transactions can only be expected to represent a part of all actual cross-border transfers. That holds also whether one assumes that all cross-border transfers take place within formal transaction systems or also include Informal Value Transfer Systems (IVTS), which can be legal as well as illegal.4dc5c2636c91

Both within and outside such systems, illegal cross-border transfers do take place. Consider if one decides to only use publicly available cross-border transfer data. How can a researcher identify the cross-border flows that are illegal due to, for instance, a bribe paid to an officer at a financial institution or at an IVTS to agree to fraudulently register false transaction details? Such transfer data is unlikely to include facially illegal activity, so how would a researcher be able to spot illegal transfers that would qualify a cross-border transfer as IFF?

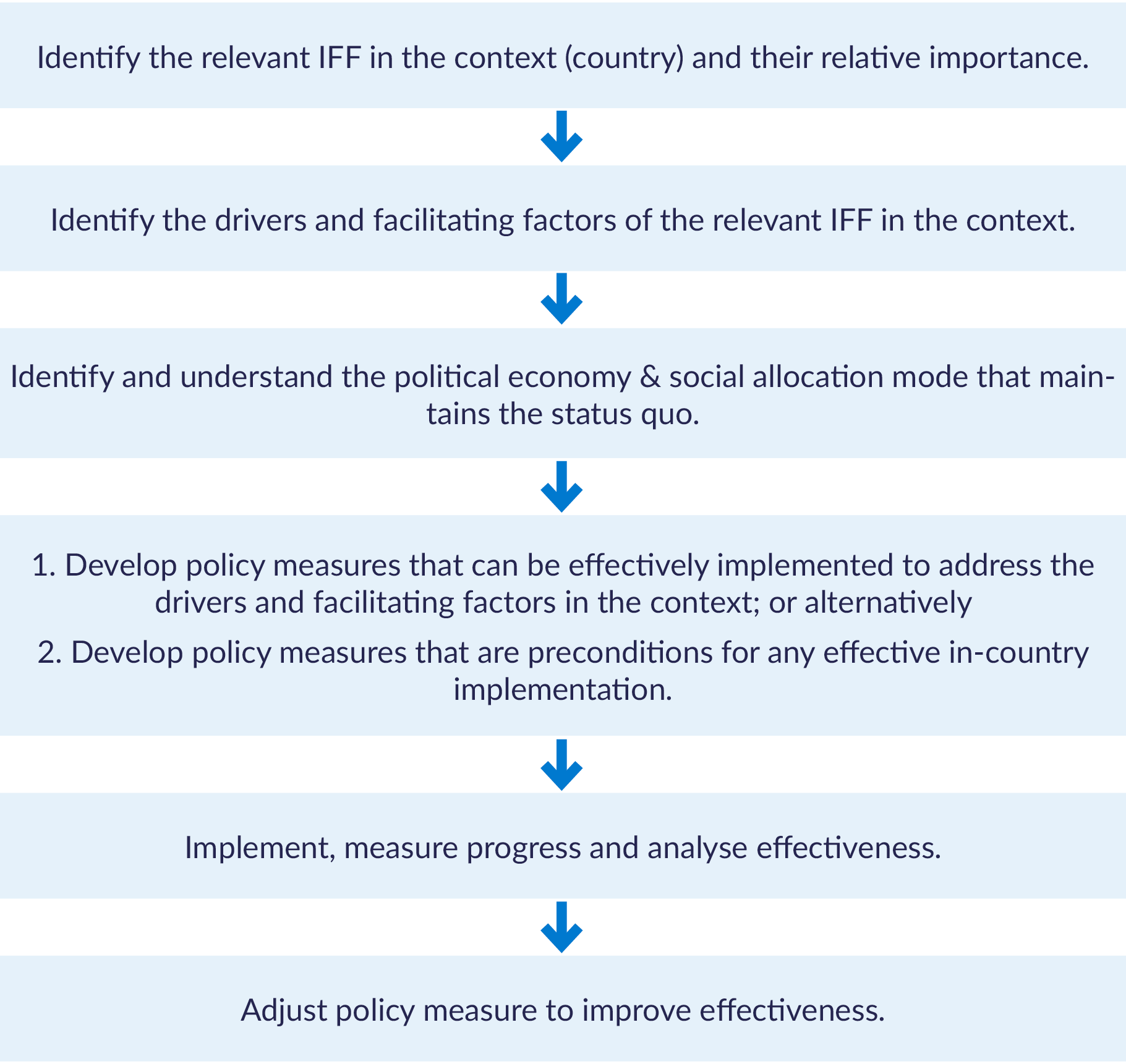

Subsequently, the definition leaves a researcher not only with an enormously difficult task, but also with the need to engage in speculation, estimation or rather ‘guesstimation.’ And all of these problems arise at the very first step of the process for identifying in-country anti-IFF policy measures (see Figure 2 below).

Figure 2. The process for identifying in-country anti-IFF policy measures.

Of course, making qualified guesses is nothing new in many research disciplines and policy areas. For example, a central feature of economics concerns selecting certain behavioural and contextual factors for inclusion in models aiming to predict the outcomes of shifts in selected variables.f6fadfe83929 It is also common to make estimates of undetected criminal activities and make projections of future developments.9a17e5bfabdc Based on such guesstimates, some choose to add another level of estimation to arrive at a reasonable cost of criminal activities.0f39a20c0347 To that regard, Kleiman et al make an observation:e872f95b109e

“Although financial-cost estimates are useful for budgetary purposes, sometimes the most pertinent dimensions of a problem are not registered on the accountant’s ledger. Omitting the avocadoes is fine when making goulash, but not when making guacamole. In this regard, crime is more like guacamole: if you omit the non-financial costs of pain, suffering, and death, and the additional costs created by the fear of those non-financial risks, you are missing most of the problem.”

Making educated guesses is also a practice used in management in contexts of uncertainty where not all the influencing factors or dynamics of a problem or a goal are known. Such educated guesses rely equally on science (logic and evidence), craft (practical experience), and art (creativity and imagination).050973237758 Given the considerable uncertainties surrounding the IFF concept, the difficulty in identifying the country-relevant IFF, the uncertain effectiveness of counter-IFF policies and their fit with contexts having weak governance and rule of law, the use of educated guesses appears useful for country-level work on IFF in many respects.

Without a better understanding of the types and extent of IFF, future attempts to assess the effectiveness of anti-IFF policies will be fraught. One possible approach in that circumstance would be to disconnect the chain outlined in Figure 2 above, and simply assume that the chosen anti-IFF policy measures (the solutions) are effective in the specific context. Such an approach would focus on measuring the achievement of the proposed anti-IFF solutions, and not on measuring their impact on the factors that delivered the guesstimate of IFF. That would however represent a repeat of the common critique against development policies for not being able to show impact.0138e18a8411 On the other hand, alternatives for measurement do exist, as when impact measurement is unsuitable.4cd0f3677898

An alternative would be to assess the effect of anti-IFF policies on the factors that plausibly contribute to maintaining the dynamics and interconnectedness of the system that make IFF possible (Eriksson, 2017b). That ‘disruption approach’ requires that step two in Figure 2 above focuses on so called ‘systems mapping.’ Systems mapping tools help explore the system, communicate understanding, and allow for the identification of knowledge gaps, intervention points and insights (Hummelbrunner and Williams, 2010).

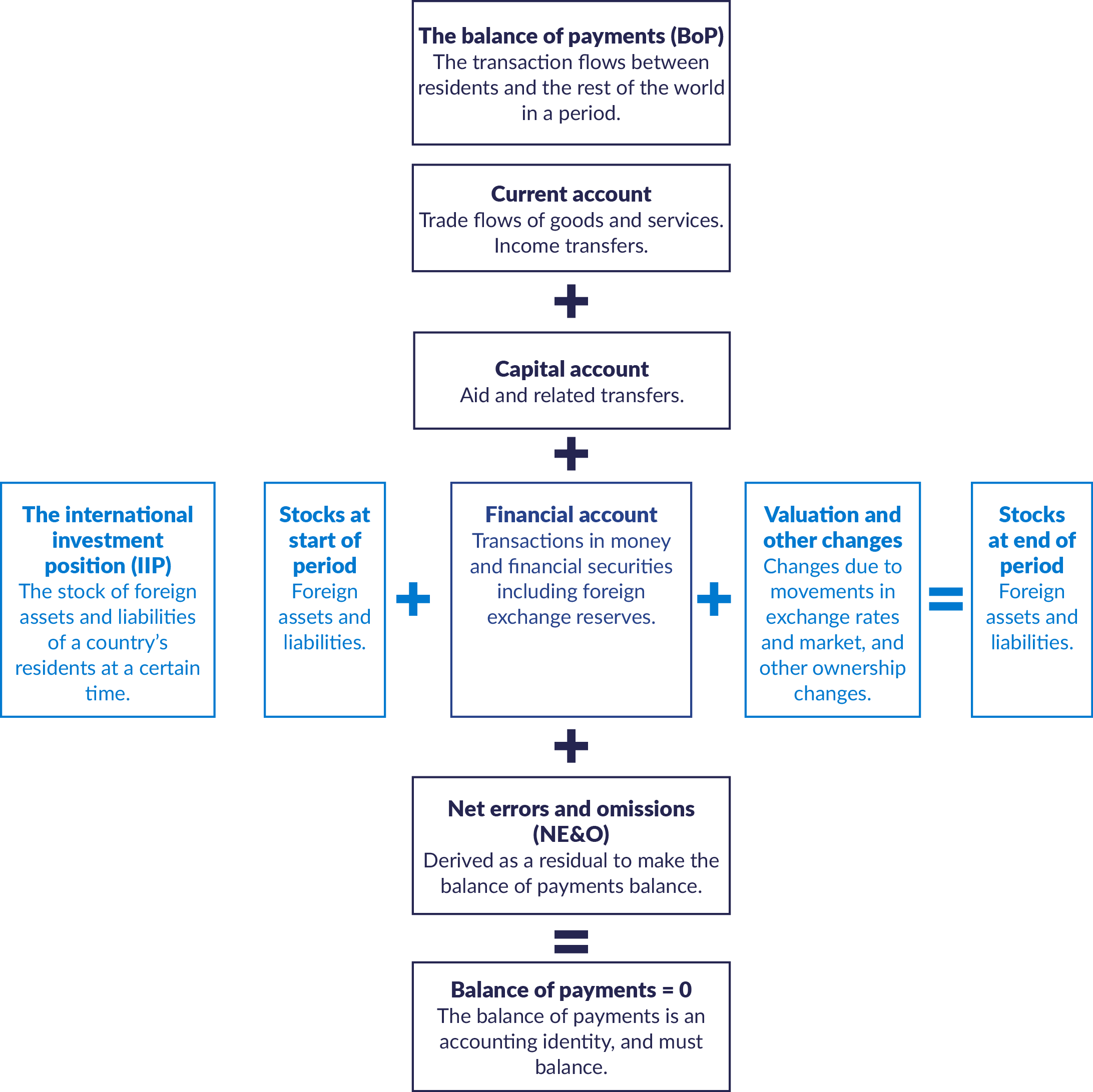

Finally, an alternative way of identifying IFF (further discussed in Chapter 3), and the approach most often used to date, is based on the cross-country flow data in the balance of payments (BoP) that are assumed to be linked to illegality (see Figure 3 below). The BoP is an integrated set of statistical accounts setting out all the economic interactions of the residents of a country with the residents of the rest of the world. This approach relies on assumptions that accounting balancing items and statistical mismatches represent illegal behaviours and thus attributes them to be IFF. The approach only leads to highly aggregated estimates. For more disaggregated assessments, the onus still falls on the researcher to identify the flows where there is illegality at source, the cross-border transfer mechanism or use (including recipient status). Consequently, such assessments include all the same uncertainties as described above.

Accuracy cannot be any better than the quality of the estimates and the assumptions behind them. Should the estimates be wrong, the wrong drivers and facilitators will be identified and the wrong policies developed. In such circumstances, it’s appropriate to ask: how good can these estimates be?

Figure 3. The two steps to decide if an activity is an IFF (Source: Alex Erskine).

The scope of the IFF definition

Another problem concerns what to include as IFF and what not to include. Country researchers on IFF have encountered difficulties and others advance arguments for expanding the scope of IFF. Below is a selection of questions, accompanied by motivating arguments, this problem raises.

Should IFF only comprise international transfers of funds, or also include domestic transfers of funds?

While the consensus has been to focus on fund flows across the border, some researchers describe some purely domestic flows as IFF.7511c616cef5 The argument is partly a consequence of looking at domestic revenue mobilisation and the loss of tax revenues, which is one of the motivations for the anti-IFF agenda. One can argue, based on traditional legal principles, that revenues generated from illegal activities cannot be taxed, regardless of whether they leave a country or not.32497bb3410f

Not all countries do apply this principle though. For example, in the USA a person’s taxable income will be treated the same regardless of whether it was obtained illegally. In the legal case James v. United States (1961), the Supreme Court held that ill-gotten gains had to be included in the "gross income" for Federal income tax purposes even if other laws would eventually forcibly require the return of those criminal proceeds. Consequently, analysts will have to take account of the (complex and country-specific) tax treatment of types of illegal economic activities that involve domestic and international transfers. While both domestic and international illegal money transfers may result in a potential loss of funds for development, the way that illegal economic activities are taxed and valued directly influences the eventual net effect on development.934ae83cfcdb

Independent of the question over the tax treatment of illegal economic activities, some important new research from the Gold and Illicit Financial Flows (GIFF) project of the Global Initiative against Transactional Organised Crime (Global Initiative) explicitly includes domestic IFF, motivated by the practical difficulties at country level to distinguish between informality, illicitness, illegality, and due to porous borders.207111545d4f While those circumstances may indeed make it more difficult to identify cross-border flows, one can question whether the cross-border characteristic of IFF can be replaced by a requirement for loss of tax revenues even if that is one of the motivations to prevent IFF.

Should IFF only comprise transfers of financial capital, or also include more physical or intangible mediums of value, such as goods, services or property rights?

Starting from the point of view that IFF represent a loss of resources for development, the consensus over time has developed that IFF should include not just money or financial capital but effectively any asset (or value) that illegally leaves a country and subsequently cannot contribute to development. Outflows involving illegal goods or services are difficult to understand as a loss to development if they cannot be taxed due to legal principles preventing such activities from generating legitimate sources of taxable revenues. Legal trade involving a fraud to illegally transfer money out of a country via trade payments is clearly part of IFF. But international illegal trade involving legal goods and services is a different matter. The illegal component is that such trade occurs on a black market, ie it is not transparent and does not follow formal requirements for economic activities involving trade. Such international illegal trade can concern legal goods such as timber from country A, sold to someone in country B, with eventual payment made to the seller, domiciled in country C, or to a group of sellers domiciled in countries D, E and F. This means that the goods traded have illegally been transferred across the border in country A, but the money flows for this trade leaves country B with recipients in countries C, D, E or F. With a definition of IFF confined to money or financial capital, country A would not suffer a loss of resources for development for the reasons that no money/financial capital leaves country A. The timber in this example can be replaced with other illegally traded assets (owned items that can be easily converted into cash) leaving country A, with the same effect. Nevertheless, physical assets (items of value) have left the country.

A similar situation concerns a fraudulent swap of assets between country A and B. The value fraudulently hidden through the swap can be converted into money outside country A. Again, a definition that extends to assets (or value) would address this problem.

Should IFF only comprise illegal activities (methods, practices and crimes) of business and governments, or also include illegal activities of individuals?

Outflows from all illegal activities are damaging to the economy and development, whether the perpetrator is an individual or a firm or government official. Inflows may be an offset in a purely balance-of-payments statistical sense, but they keep more funds out of the formal economy and add to governance problems. Money is fungible: there is no difference between the cross-border flow of one illegal dollar and another illegal dollar, no matter who is responsible for the flow (business, government or individuals). Thus, the definition needs to be extended to include the illegal activities of individuals.

Should IFF only comprise illegal activities (methods, practices and crimes), or include legal activities that are deemed illicit?

The GIFF’s in-depth studies of gold mining activities in West Africa suggested that not every IFF is illegal: some are only illicit.20dbf37e25c7 This brings the discussion back to a continuing problem with the IFF concept: the term ‘illicit’ includes illegal acts but also includes disapproval by society.2dcc77eabac4 Illegality requires that a crime or otherwise breaking a law or a regulation is involved at some point in the activity. The illegality criterion explains why tax avoidance, such as intra-firm profit shifting, is not an IFF, whereas tax evasion is. One way of understanding the choice to stop at illegality is because it removes uncertainty and personal discretion for deciding what is illegal. As such, laws provide legal certainty. Additionally, by referring to law, the responsibility for deciding what is legally acceptable rests squarely on national parliaments or legislatures. Another reason in favour of the illegality criterion has to do with pragmatism: it is easier for governments to agree to a definition that refers to illegality as the criterion for IFF because what is illegal is something they have control over. For governments that have no interest in preventing IFF, that criterion is clearly preferable. Choosing illegality also makes it more likely that it is possible to estimate IFF because there will be more information available on criminal activities that have been reported and prosecuted.

Nevertheless, law may stipulate what is legal or illegal, but it certainly does not mean that laws reflect a societal consensus of what ought to be legal and not, as legislative power may represent specific interests that are unrepresentative of society at large.85b59b45c718 This is particularly true in many developing countries, where the law clearly suffers from this sort of problem, but perhaps more so in selective and particularistic implementation of law and policies, as well as in the allocation of resources.6254d4fb81f0 Subsequently, using the qualification of illegality may in fact ignore the political realities behind IFF by not recognising ‘legal corruption.’ba2725301aa9 In other words, the quality of laws and the interests they represent render them unreliable in identifying extractive economic institutions that contribute to transferring public resources out of a country, further undermining the interest of political elites to take an active interest in improving domestic governance and institutions.08ba60d28647

Should IFF only be defined according to what is deemed as illegal in the laws of the country where the flow comes from, or it can be defined as illegal by the laws of the receiving country, or by the laws of some other nation state?

Finally, the OECD definition of IFF indicates the illegality should be in respect of “national or international” laws, whereas the World Bank says “national” law is the criterion.4118b2119412 In practice, however, no consensus has developed and researchers have not focused on this issue. The domestic laws of some countries have extraterritorial reach in terms of standard-setting for behaviours by actors in other jurisdictions. However, such laws only establish jurisdiction over such actors abroad if they have some legally defined connection to the country of the law. Examples of such extraterritoriality can be found in the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act, the UK Bribery Act, as well as in anti-corruption legislation of other jurisdictions who are parties to the OECD anti-bribery convention. Consequently, national laws, whether they have extraterritorial reach or not, identify illegal (including criminal) activities that relate to physical and legal persons that somehow have a legally valid connection to the respective nation.

International law differs from state-based legal systems in that it is primarily applicable to countries rather than to individuals or organisations. Much of international law is consent-based governance, which means that a state member is not obliged to abide by international law unless it has expressly consented to it. There are exceptions to consent-based international law, which establish mandatory demands on the behaviour of states and non-state actors regardless of consent. However, such mandatory norms are found in customary international law and peremptory norms (jus cogens), which do not relate to IFF. This means that the definition of illegality based on an international law cannot be applied to a state that has not consented to that international law. For those countries that have consented to certain international law, there need not be a conflict between national and international law in defining what is illegal and not: international law consented to supersedes conflicting national law, although international law may not yet have been incorporated into national law.

But the reference to international law might create conflicts with national laws due to how they are interpreted.68b8990a7252 That has immediate relevance for how to define what ought to be illegal in national law, and hence directly impacts how to define IFF in a specific country. Whereas economic policies are rarely the subject of international law, an open question is how to interpret what qualifies as abusive laws that legalise corruption,16db0525fa66 or ‘extractive economic institutions’ that are structured to extract public resources and put them into the hands of private actors.d76843f632d9 Either way, the reference to national and international law makes the scope of IFF relative in each country.

Having reached this critical juncture in pursuing the IFF agenda, it is now time to agree to a more precise definition of IFF so that country studies and other research can proceed with broadly similar criteria for what are IFF. At the very least researchers (and those who guide them) seem likely to have to:

- Distinguish between ‘international’ and ‘domestic’ IFF.

- Shift to focusing on ‘value’ transfers rather than just on ‘financial’ transfers.

- Include all actors, not only business and government officials.

- Recognise and understand from a country perspective the complexity of even the apparently straightforward term ‘illegality’.

Only then can donors and others with consistency orient global and country research towards all relevant IFF activities and accelerate the search for effective actions.

Estimations of IFF

Problems with the balance of payments (and trade) perspective

International and country balance of payments and trade databases are readily available, and many researchers have used them as a shortcut to estimating the volume of IFF. The two components of almost all global/multi-country estimates of IFF are unrecorded (presumed illegal) capital flows and trade misinvoicing. Both are based on historical antecedents: the capital flight research on the Latin debt crisis in the 1980s and the trade mispricing studies of Bhagwati.8c57871b8b51

The research underpinnings of the IFF agenda thus far have been strongly influenced by estimates comprising proxies for capital flight and for trade misinvoicing made by GFI and N&B. Curiously, the relationship between the IFF definitions and the methodologies these researchers have used to arrive at IFF estimates has been given little attention.

To understand why this is the case, some background is required on the balance of payments. The full BoP is an integrated set of statistical accounts setting out all of the economic interactions of the residents of a country with the residents of the rest of the world.1e2d8f72602f

There are two main parts of the Full BoP accounts (see Figure 3):

- The Balance of Payments (BoP): One part (confusingly, also termed the Balance of Payments), records the transaction flows in a period such as a year, dividing those transaction flows between the current account (for goods and services transfers – these are the trade flows – and income transfers), the capital account (mainly for aid-related transfers) and the financial account (for transactions in money and financial securities).

- The International Investment Position (IIP) records the stock of foreign assets and foreign liabilities of the country’s residents at a time such as the end of a year and accounts for the changes in those stocks over time.

Figure 4. Simplified illustration of the full balance of payments and its components. (Source: Alex Erskine)

The following aspects of the BoP framework are important to understand how IFF currently are identified:

- It is a ‘double entry’ system: for the country, every credit has a corresponding debit.6676567dcb4b Any discrepancies in the double entry system for a country are reconciled by including a balancing item or statistical discrepancy, termed net errors & omissions (NE&O), to make the three BoP flow accounts balance. The sum of the balances on the current account, the capital account and the financial account and the NE&O has to be zero: this is an accounting identity.

- By convention, these NE&O tend to be considered part of the financial account, rather than part of the current account or the capital account, even though the errors and omissions may well have originated outside the financial account.

- Transactions are valued at market prices prevailing at the time of change of ownership. Similarly, stocks of assets and liabilities are valued at market prices on the date specified. In practice, trade transactions are often recorded at the time of reporting to the customs authorities and at the values then declared.

National and international statisticians developed a rigorous full BoP accounting framework in the 1940s and have persisted in reforming and adjusting the framework to maintain its relevance as global development has proceeded. Most countries have long had an interest in trade and balance of payments transaction flows and have their own BoP accounts. As a result, the quests to find proxies for IFF have habitually started with BoP and trade data.

The essence of the estimation processes to date has involved adding together two factors to provide an estimate of IFF (see Figure 4 below):

- BoP data: NE&O is assumed by most IFF researchers to be a proxy for deliberately undeclared and illegal transactions shifting capital across the border (described by some as unrecorded capital flows or ‘capital flight’).

- Trade data: IFF researchers have often also typically derived a ‘mirror mismatch’ between what the country has recorded as exports to (and imports from) its trading partners, and what the trading partners have recorded as imports from (and exports to) the country. After adjusting for assumed transport and insurance costs, this is used in a variety of ways to serve as a proxy for what is assumed to be deliberate and illegal misinvoicing of trade to shift capital across the border.

Figure 5. The ‘typical’ research approach to estimating global or multi-country IFF. (Source: Alex Erskine)

From the BoP perspective, IFF outflows include not only those IFF outflows that have been recorded, but also the shortfall from what the country’s full BoP accounts would have recorded had activities been undertaken legally and properly reported at market value. The shortfall resulting from an IFF can occur anywhere in the BoP flow accounts: in items in the current account or the capital account, as well as always in the financial account. And the shortfall resulting from an IFF will necessarily also impact on the country’s international investment position (IIP).

Consider two examples:

- An export that is not reported, eg, as a result of smuggling

Illicitly traded goods, such as an export smuggled out, will affect BoP data in that it will show exports to be lower than if recorded and the current account more in deficit/less in surplus. If the foreign payment for the goods is also smuggled (ie not recorded), transaction flows into the country reported in the financial account will also be lower. If the foreign payment for the illicitly exported goods enters the country in a way that is recorded in the financial account, there will be an imbalance that will be reflected in the net errors and omissions (NE&O). - An unrecorded flow of capital out of the country, eg from grand corruption

Both that flow and, unless it is separately declared, the corresponding claim over a bank account or securities abroad will fail to feature in the financial account. Such failures will potentially reflect in a NE&O larger than otherwise and/or less net foreign assets in the IIP.

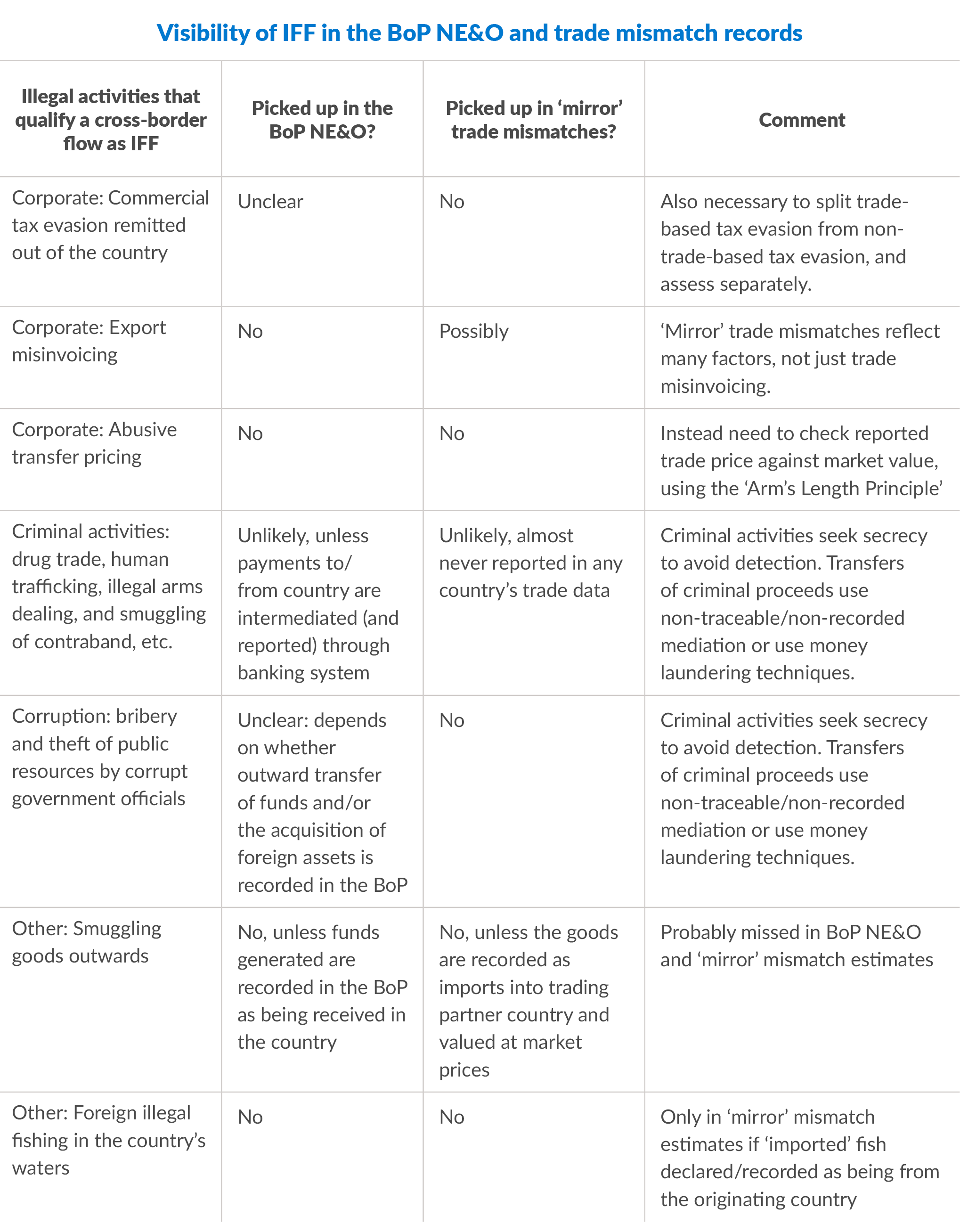

Given the previous discussion on the problems with the definition and the difficulties of identifying the cross-border flows that qualify as illegal, the question arises whether this BoP and trade data methodology really can capture the IFF. Table 2 below highlights some of the challenges confronting researchers regarding the effect of some IFF activities on what is recorded in the BoP and trade records.

Table 2. Visibility of IFF in the BoP NE&O and trade mismatch records (Source: Alex Erskine)

Assessment of IFF impacts

As previously suggested, researchers cannot be held liable for advocates’ misuse of research. They can however make as clear as possible to advocates what their IFF estimates represent and some of the uncertainties in assessing implications of IFF. For instance, tracing though the development consequences of IFF is complex and the impact of IFF on development is uncertain. Advocates (and headline writers) at times may have been confusing what has been estimated to be IFF from a country with the additional funds for public spending that would be available if the IFF had not occurred.

The most likely effect of unanticipated IFF outflows is an increase in the current account deficit creating a shortfall in the BoP (see Figure 4 above). This requires an increase in the amount of finance that has to be raised from international sources or from the country’s foreign exchange reserves to keep the overall balance of payments in balance. This may have further negative consequences in terms of market or policy changes. Market-driven changes might include higher interest rates and/or a weaker exchange rate, each with a variety of implications for economic activity and welfare. Policy changes may include official moves in interest rates and/or the exchange rate, suppressing market-driven activities, or changes to planned public spending or revenues. However, this is only the first of the adverse economic impacts of IFF outflows.

A second impact may be on the country’s fiscal position. When tax revenues are lower than planned, say as a result of tax evasion and leading to less money circulating in the formal economy, fiscal policymakers face a choice: the government may choose to do nothing but borrow more, or raise other taxes and/or reduce government spending. All such decisions have varying economic and development consequences.

The activities that lead to IFF outflows may also cause further damage to growth and development prospects. For instance, reports of such illegal activities lead to and perpetuate low levels of trust in formal governance and the rule of law. In addition, loss of wildlife, trees, fish and other natural resources through IFF related activities such as smuggling/illicit trade practices have an impact on the country’s environment that adversely affects growth and development potential. Such externalities are often hard to value in monetary terms.

The full cost to development due to IFF is especially hard to assess. Were the IFF activity not to have occurred, the impact on domestic savings, national investment (fixed capital spending), and consumption is unclear. But the presumption is that the potential for domestic development would be increased if the additional tax revenue from low levels of IFF allowed lower tax rates or increased public or private investment in infrastructure, education, health, or productive employment opportunities.

Nevertheless, researchers (and citizens) have to ask if this is a reasonable expectation even if more resources would be spent on these policy areas, other things being equal. Development assistance that has focused on precisely those policy areas have struggled to show any considerable developmental effects.6b1defd983fb

Confusion over trade misinvoicing

The trade misinvoicing theme is similarly being pushed to an extreme by analysis that assumes that aggregated ‘mirror’ trade data mismatches (gross or net) are ‘proof’ of deliberate trade misinvoicing and tax evasion.

Technical rejection of this assumption is provided by the International Trade Centre (ITC) (International Trade Centre, undated). The ITC, a joint agency of the United Nations and the World Trade Organization, alerts researchers to the numerous reasons why ‘mirror’ trade data will not match the in-country data even after adjustment for known valuation differences. This is because many developing countries are non-reporting countries, and some use differing statistical standards especially for low-value transactions. Also, timing and exchange rate differences can intrude, as many goods are shipped to transhipment ports for re-export rather than shipped to their final destination, and so forth.

Too often these poorly constructed estimates are used to guide further research work. Their influence is hard to set aside. As just one example, in reviewing trade mispricing estimates for five African countries, Nicolaou-Maniasfb87dc5fc7a7 carefully lists several flaws in using the two most used databases, the IMF Direction of Trade Statistics (DOTS) and UN COMTRADE. Nevertheless, her paper repeats other researchers’ poorly-based headline estimates, and provides estimates for the five countries, even while urging readers “to be less focused on the actual amounts of [estimated] IFF, as this is a clandestine activity with resultant data problems” (Ibid: Conclusion).

Reflecting on these data concerns, many policymakers and many in the development/donor community are not persuaded by the magnitudes of the trade misinvoicing claims.ab53a3bd62fc The search for a preferred methodology has started in the UNODC-UNCTAD SDG Indicator exercise. Deliberate misinvoicing obviously can and does occur, but the quantum is in great doubt. GFI’s approach to IFF estimates has led to a view that trade misinvoicing outflow is by far the major type of underlying illegal activity involved in IFF.3580389f51d8 Global leaders have also announced the G20 is partnering with the World Customs Organisation (WCO) to throw new light on what is occurring.b5b2b85f5356

Trade taxes imposed at Customs border posts and ports clearly create opportunities for arbitrary delays, discretion on taxes, corruption and other frauds. The activities need to be understood and assessed. No one could dispute trade misinvoicing is a potentially major type of IFF and needs to be reviewed in any country study, but there is no evidence yet to suggest it is the major type.e944b6eca69b This claim results in part from assumptions (eg, in work by GFI) that all gross ‘mirror’ trade data mismatches are trade misinvoicing56f8451e31d3 and that the net BoP NE&O are the net of all other IFF and that the sum of the two is the total IFF. Not only should gross and net figures not be aggregated to create an estimate of total international IFF (it is adding apples and oranges), but clearly not all data mismatches and discrepancies reflect IFF.

One reason for why it is unrealistic to rely on the double entry bookkeeping approach and compare country BoP and trade data to try to figure out the size of IFF is because of data quality and coverage, which may very well be a question of governance. Why should we expect that the Central African Republic has qualitatively comparable data to Norway when there are no other comparable governance characteristics between the two countries are of similar quality?

BoP and trade accounts may come close to the ideal for double entry bookkeeping between countries in a statistically well-resourced and tight economic area such as the European Union (EU), but not in less integrated or statistically less well-endowed regions. Many developing countries lag in terms of the coverage and compilation of their BoP, capital flow and investment positions data. The importance of this is that much of what is alleged to be deliberate non-reporting or fake reporting may just as well reflect the different BoP data quality across the countries.

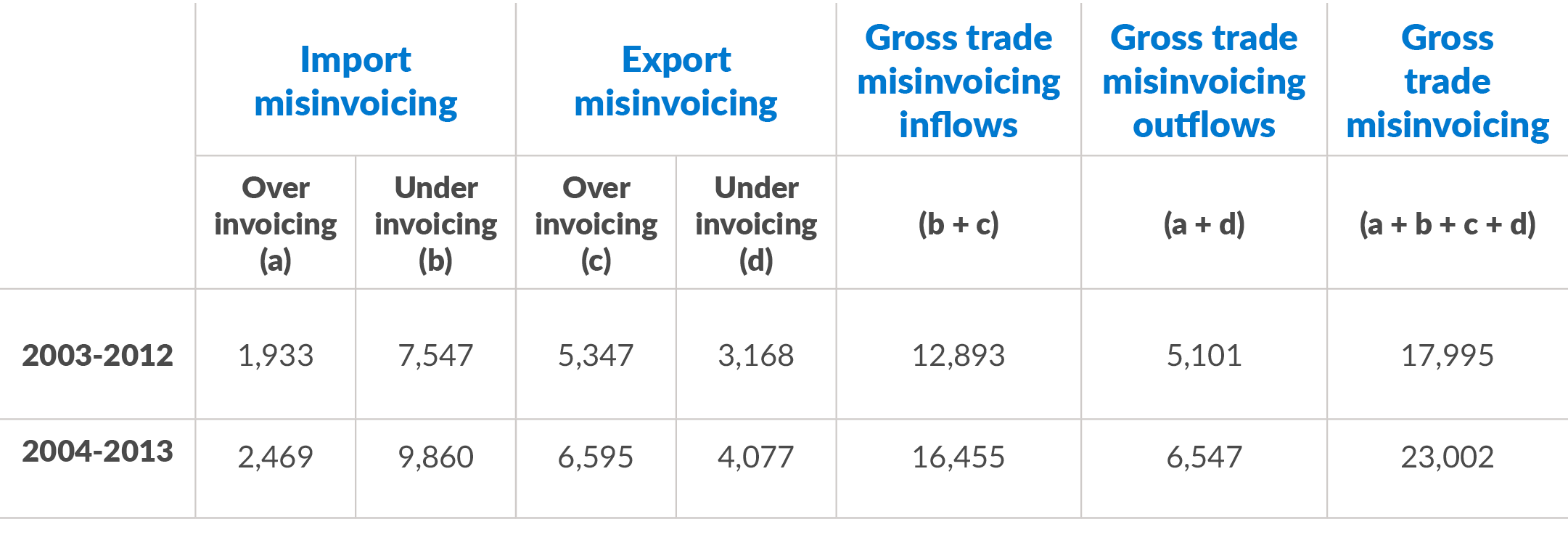

One critic has highlighted the arbitrary assumptions made by GFI, especially its decision (up to that point) to focus on what is seen as trade misinvoicing outflows while ignoring inflows.9607a8c13ade Table 3 provides an illustration, using the findings of two recent (but not the absolute latest) 10-year IFF studies by GFI. The alleged trade misinvoicing outflows are the sum of export underinvoicing and import overinvoicing (columns a. and d. in Table 3 below), whereas the alleged trade misinvoicing inflows are the (bigger) sum of export overinvoicing and import underinvoicing (columns b and c).

Table 3. The components of trade misinvoicing, all developing countries, US$ billion. (Source: drawn from Kar and Spanjers, 2014 and 2015b)

Table 3 shows that developing countries had been estimated to be receiving more ‘misinvoicing’ inflows than outflows. That observation undermines IFF agenda proponents’ headlines to the effect that an estimated US$6.5 trillion had been drained from developing countries through trade misinvoicing outflows in the period 2004-2013. The headlines could as validly claim that an estimate of US$16.5 trillion had been gifted to developing countries through trade misinvoicing inflows. In recognition of this criticism, GFI has given some prominence to estimates of trade misinvoicing for inflows as well as outflows in its latest, 2005-2014, report.5dd973ca0cd6

While grappling with the IFF estimates, the question of data integrity is important. As mentioned, unknown parts of statistical discrepancies may represent weak statistical governance or resourcing in developing countries. The amounts found by BoP NE&O and trade misinvoicing researchers varies over time as historic data is revised and research methods change.de8b1ae0acd0 Improvements in methods are important and revisions to underlying data are inevitable when new and revised country data is submitted. But that also means data quality will shift over time.

Finally, by at times setting aside estimates of illicit financial inflows which may contribute to development, the characterisation that emerges does not quite represent the whole picture. From a political economy perspective, countries that receive large inflows of IFF may have little incentive to prevent IFF, fearing that the loss of such inflows will not be replaced by legal inflows. Obviously, that is not a reason to accept status quo, but it ought to be important to inform policy and strategy to achieve wanted change.05be7930c6cf

The role of corruption in IFF

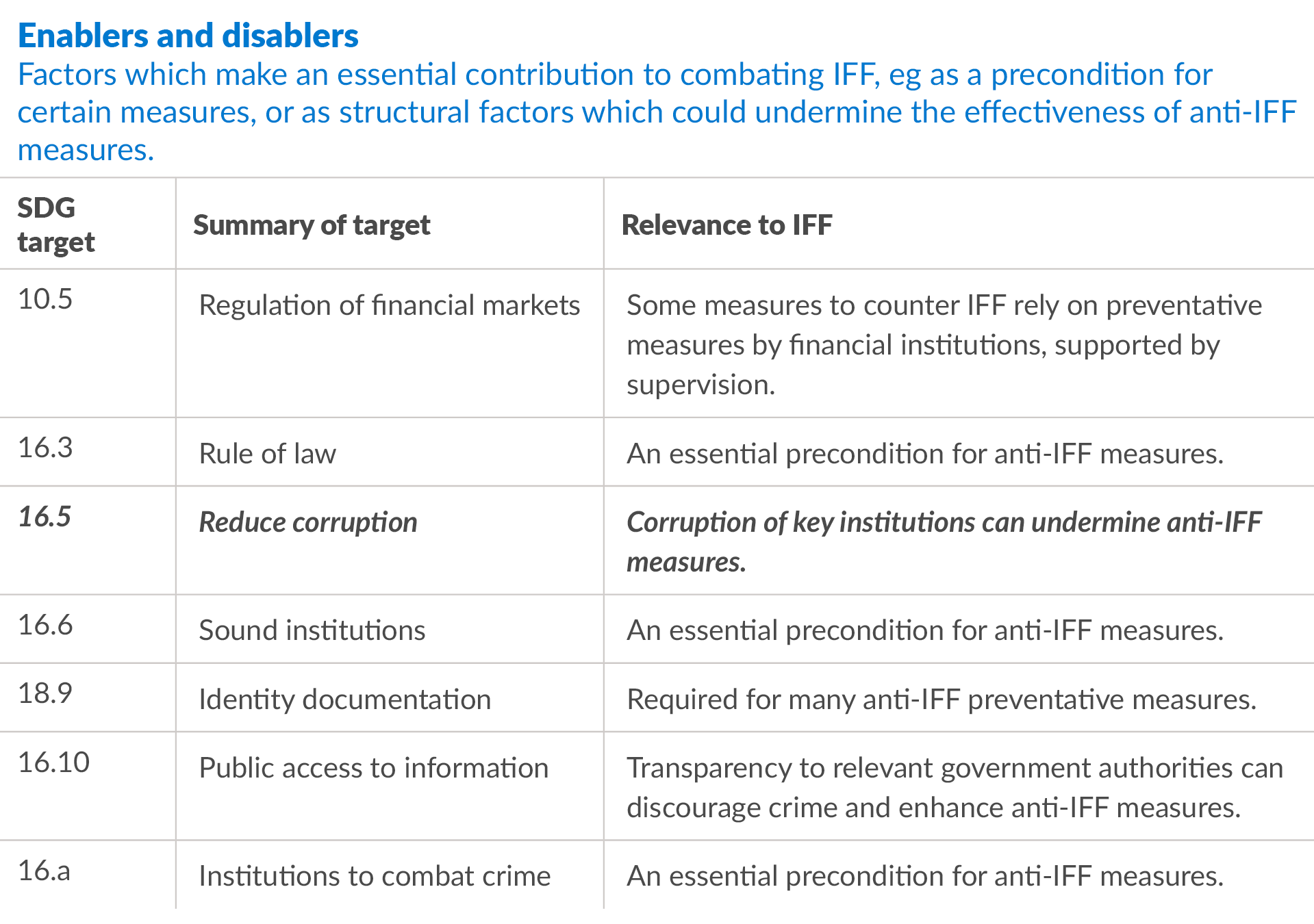

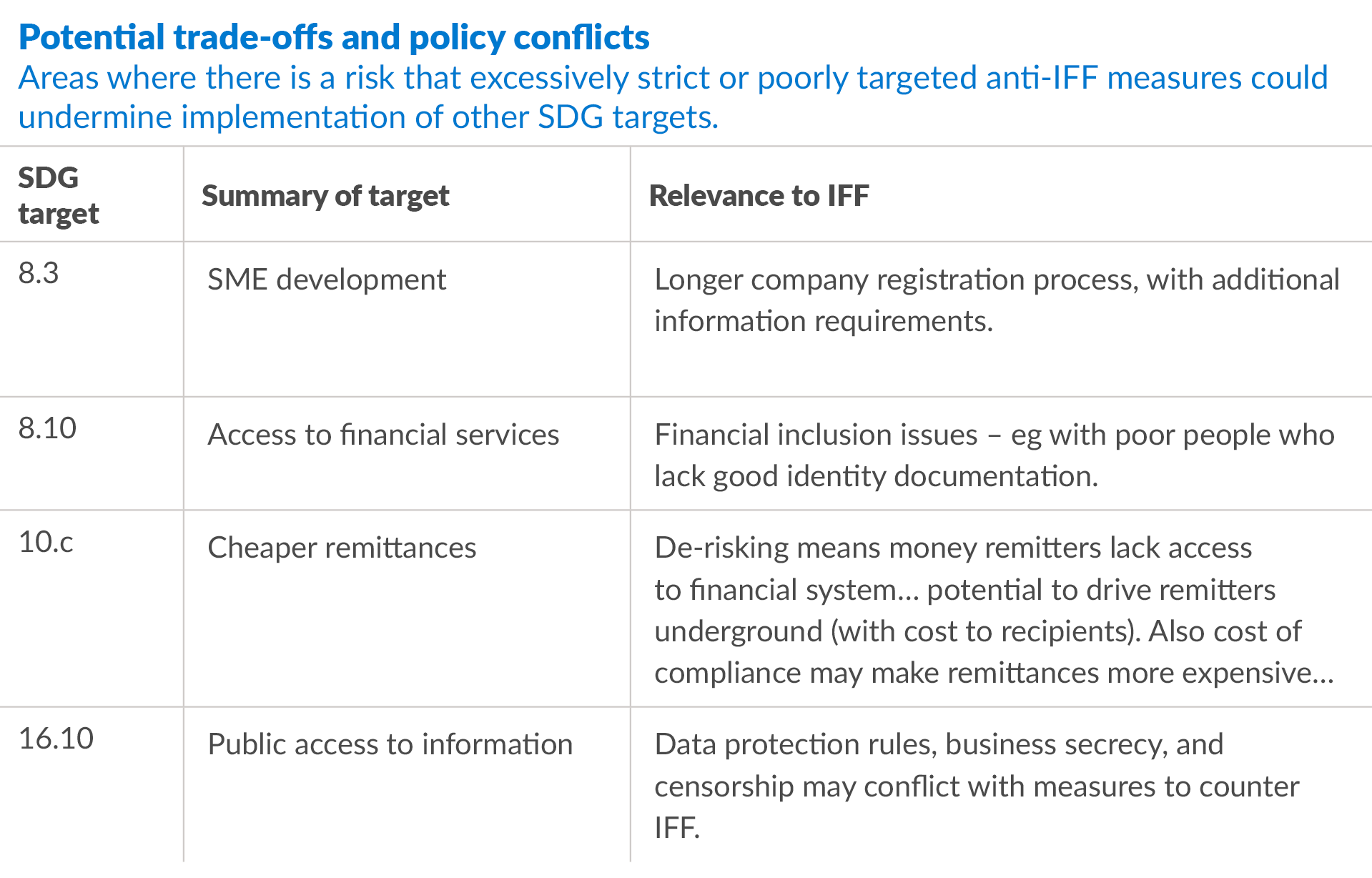

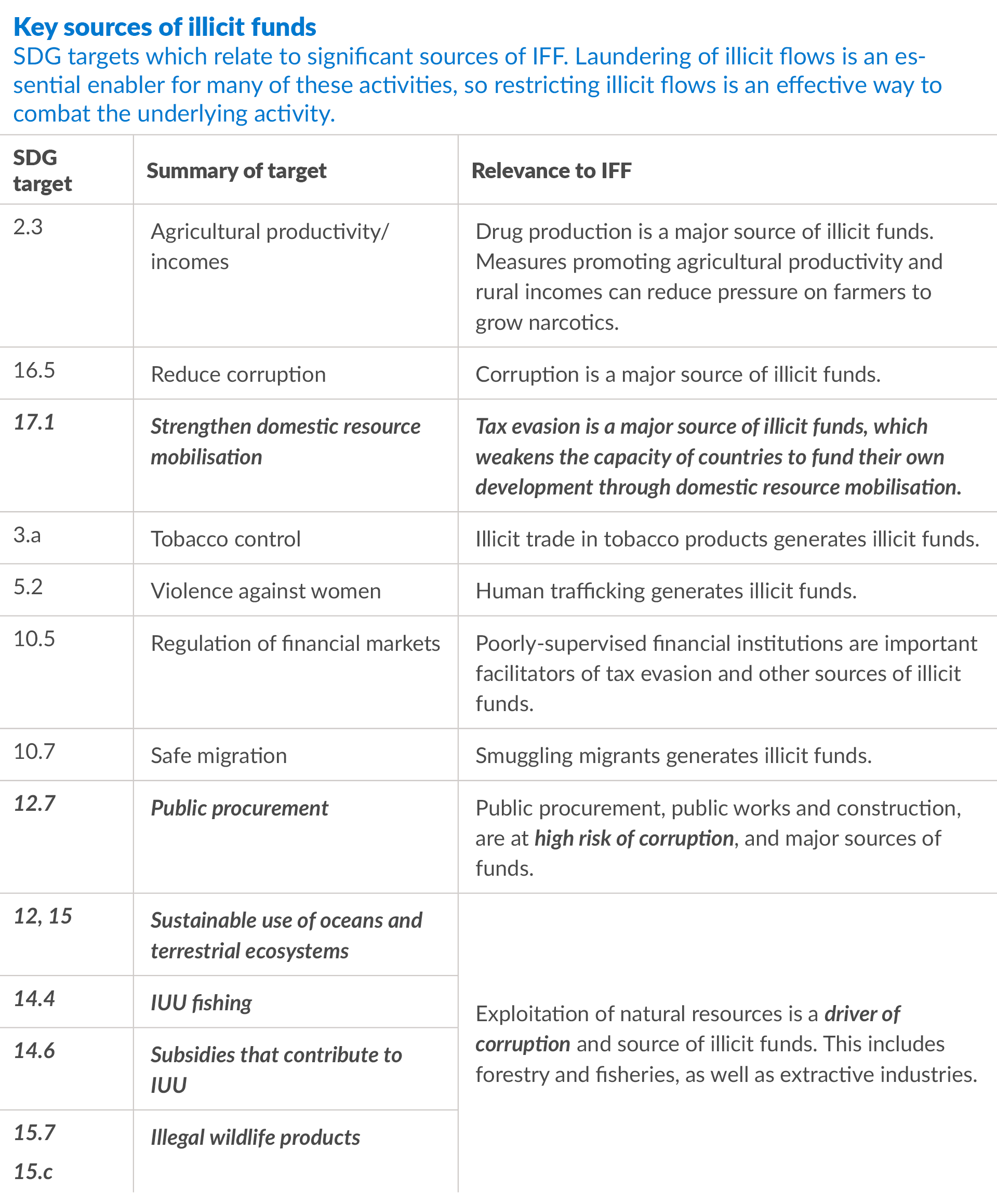

The SDGs comprise 17 goals and, within those goals, 169 targets. Corruption and bribery are specifically mentioned in Goal 16 on peace, for which Target 16.5 is: “Substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms”. Target 16.5 overlaps with Target 16.4 in relation to curbing IFF and facilitating asset recovery related to corruption cases. Table 4 sets out the SDG targets related to IFF, as seen by the OECD.

Table 4. SDG targets seen by the OECD as related to IFF and the role of corruption. Source: from OECD 2015, Table 2.2. p 54 (emphasis added).

What stands out from Table 4 above is that successful anti-corruption policies are recognised as one of several requirements for measures to curb IFF to be effective. Anti-corruption successes are needed to:

- Ensure many preconditions are achieved, including regulation of financial markets, rule of law, sound institutions, identity documentation, public access to information and institutions to combat crime.

- Disrupt sources of IFF from a large number of activities, in particular, though not limited to, agricultural productivity/incomes/drugs production, tax evasion, tobacco control, human trafficking/smuggling migrants, financial markets, public procurement, and exploitation of natural resources.

The OECD and World Bank suggest that anti-corruption policies cannot be subdivided into those that focus on IFF and those that do not. Anti-corruption policies (presuming they are effective) either reduce IFF directly, by preventing corrupt activities that are a source of IFF, or indirectly, by preventing corruption activities which undermine the rule of law and the quality of governance, making formal governance ineffective.

Still, the predominant understanding of the role of corruption in IFF is as the process that generates the unlawful gains that are then transferred across borders. However, only looking at corruption as a source of IFF misses important linkages between the two practices, as “[c]orruption is both a source and enabler of IFF.”a09337b02b32

While the volume of IFF is notoriously difficult to estimate, it is perhaps most difficult to estimate a useful volume of IFF that is related to corruption.538aa43f2c16 Compared to the actual corruption crime level, few corruption cases are ever exposed and confirmed. It is only confirmed cases that can be used to establish how much of the cross-border flows of funds that relate to corruption with any accuracy (according to definitions in criminal law). The reason for that is that the existence of corruption as defined in law is confirmed by courts of law. Other accounts are based on perceptions or experiences of corruption that have not been tested and confirmed by a court of law. But such positivist views do not mean that non-confirmed instances of actual corruption do not occur. It would be absurd to claim that few legal judgements confirming corruption means a kleptocracy or a country with weak justice system have few instances of actual corruption.

However, what is not confirmed has to be based on some model of estimation of what could be confirmed as corruption. In addition, to arrive at an estimation of corruption-based IFF, we also need to estimate the volume of the proceeds of the many different types of corruption, and how much of that crosses a border. Those definitions of IFF that also qualify cross-border flows of funds as IFF if funds are used for corruption also need an estimate of that.9057ac0ebc72

For obvious reasons, estimates of what is unknown cannot be accurate: claiming credibility for estimates will require a significant leap of faith. The resulting volume of corruption-based IFF then needs to be combined with the highly contested volumes emanating from other types of illegal activities for a total estimate.a7c7279d4228 Those eventual estimates will depend on what definition is used.d771a18dd465 Yet, to some extent, the link between corruption and IFF is self-evident in that corruption facilitates “all other aspects of IFFs.”64eff377e4a8 By taking a broader view and keeping the different components of the definition in mind,6bf94583a401 the role of corruption is considerably larger than only representing a source of funds for cross-border transfers. The expanded role/function of corruption in IFF includes:

- Facilitation of illegal transfers

Actors behind illegal (including criminal) activities can use corruption to access the international financial system for the purpose of hiding and eventually enjoying the proceeds of their illegal activities. - Facilitation of the illegal activities that generate the illicit funds themselves

The role of corruption in trafficking of drugs, humans, toxic waste, weapons and wildlife is well known. - Incapacitation of public and private institutions that could prevent or detect cross-border transfers

Examples of such institutions are financial institutions, intelligence agencies, tax-, customs-, or trade authorities.b3e0a0d13818 - Contribution to IFF as a source of funds

This is the current common understanding of the role of corruption in IFF. - Facilitation of the illegal use of funds that have crossed a border

Bribery of some kind can be used to make those with a role to prevent the illegal use of funds (for example for corruption, funding of terrorism, payment for trafficked goods or people) look the other way.

As is clear from the above, policy makers need to recognise corruption’s broad role in facilitating IFF. Policies dealing with corruption in IFF need a considerably wider scope than simply addressing the underlying corruption in individual cases of IFF.e55c2515b706 To make anti-IFF measures effective, policy makers will need to think much more critically about the nature, location and type of corruption that is relevant for countering IFF at country level.

Practical proposals at country level

This chapter sets out some thoughts on alternatives for identifying data that could alleviate some of the discussed problems of methodology to identify IFF in country studies. The immediate need is to find a robust approach to identifying and analysing IFF at the country or industry level. Also, an alternative approach to implementing IFF countermeasures is presented that recognises the complexity and uncertainties surrounding the implementation of IFF countermeasures in adverse contexts. Finally, a practical approach is presented as an alternative to measuring the effects of IFF countermeasures that builds on experiences from the field of anti-corruption. Rather than struggling with uncertain IFF estimates and assumptions as a consequence of unavailable or inaccessible data, which in turn stem from the definition of IFF, it assumes the effectiveness of countermeasures.

Alternatives for identifying data

As previously discussed, there are numerous challenges to the identification of IFF. The trade misinvoicing methodology suffers from several shortcomings, including the assumptions of what it measures as well as only covering one type of IFF. But there are alternatives to identify IFF that are also likely to contribute to a better understanding of the contexts of the flows.

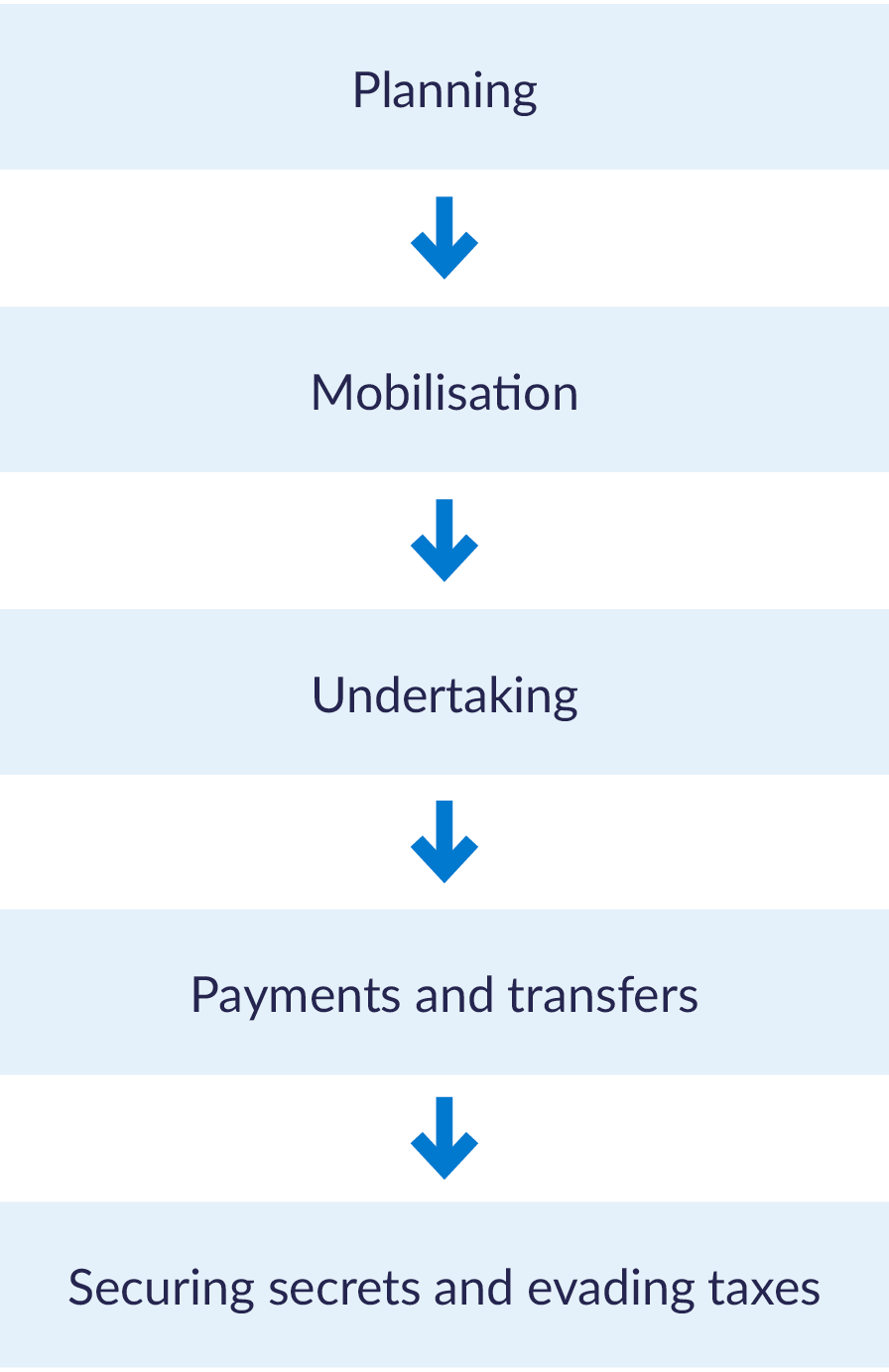

Analysing the steps involved in crimes or illegal activities linked to cross-border transfers

To understand the facilitators and interconnections of illegal activities and crime involved in cross-border transfers, country studies will need to trace through the illegality or illegalities involved in an IFF. These might occur at any (or every) stage of an IFF activity (see Figure 6).

Figure 6. The stages of an IFF activity

Example:

- A poaching crime financed from abroad followed by the illegal smuggling of wildlife parts

In the planning, there will have been an intent that a crime be committed. At the planning or mobilisation stages, some funding may have been transferred into the country to pay the poachers and their costs. At the mobilisation or undertaking stages, corrupt payments may have been made to secure non-enforcement of the law against poaching, and arms and ammunition illegally obtained. The undertaking stage may involve several illegal acts: killing wildlife, dismemberment and undeclared export of wildlife parts as well as illegal internal and cross-border financial flows. In the near-final stage, the foreign party may receive the illegal products for use or sale and illegal payments in-country and abroad may be made. Bribes may have been paid, or fees paid for accounting and legal advice, in effect to secure the secrecy of the crime, to hide the source of funds (money laundering), and to evade taxes.

Mapping the interconnections between various illegal activities and crimes is a common practice in crime prevention to identify strategic crime prevention measures. As suggested in the poaching example above, several illegal activities and crimes may be linked to the same cross-border transfer. This raises the risk of double-counting (or worse) if the outflows from all individual types of crimes are aggregated. To reduce the risk of double-counting, in each instance the main predicate crime must be identified, and intermediate crimes linked to that predicate crime.

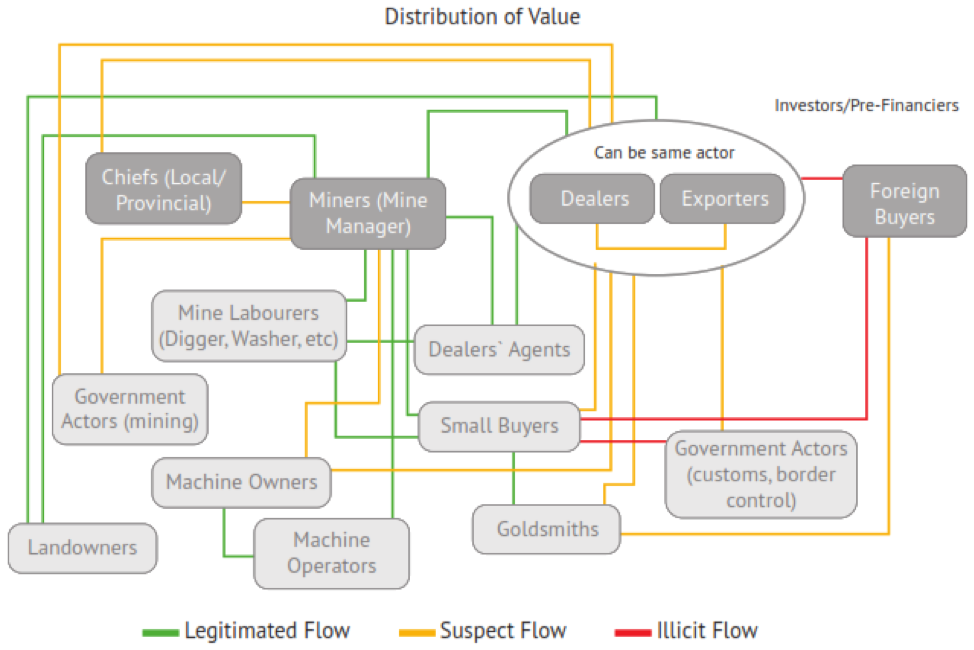

Mapping trafficking-type crimes leading to IFF

Trafficking crimes (the activity of selling and buying goods or people illegally) may involve value in some form (drugs, humans, wildlife, fish, forestry, waste, weapons, etc.) crossing borders, rather than money or financial capital. As discussed above, many IFF definitions refer to illegal cross-border transfers of money/financial capital, which would mean that such illegal cross-border value transfers do not qualify as IFF. Nevertheless, trafficking-type crimes may through payments result in illicit financial inflows, but also consist of contributing illegal acts or crimes somewhere along a trafficking operation that result in a cross-border flow. As illustrated in Figure 7 below, country studies seeking to identify such flows inevitably become highly detailed.

Figure 7. Financial flows linked to the Sierra Leone Artisanal and Small-scale Gold Mining Sector (after financing and start-up costs). (Source: Global Initiative and Estelle Levin Ltd. 2017b. Figure 5, p16.)

The illustration above only covers one sector of one industry and its potential IFF activity. Something similar could be required for each of the major IFF activities involved in many developing countries.

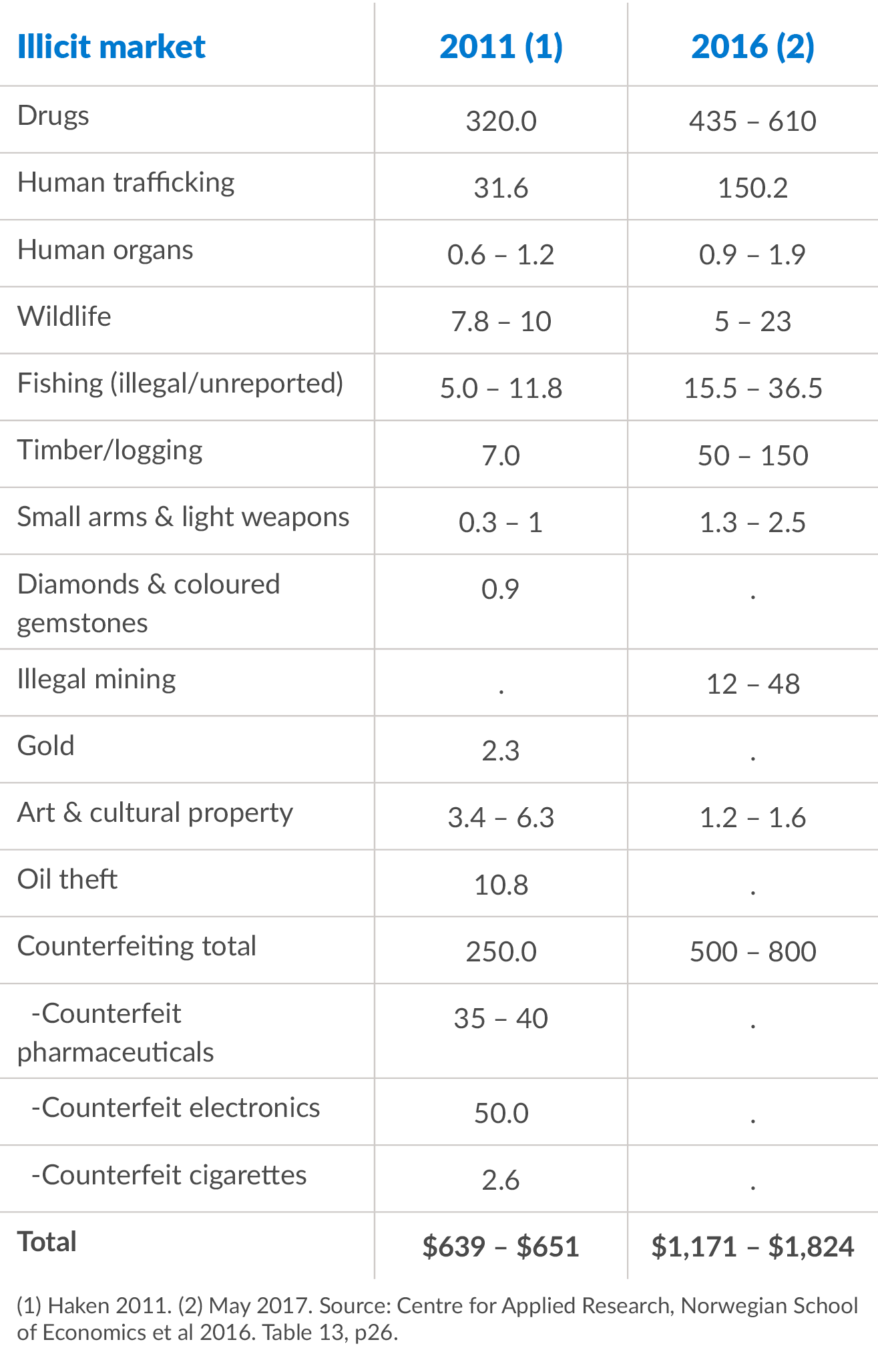

A starting place is GFI’s all-developing-countries aggregate trafficking-and-counterfeit approach to IFF.ff94ff60c276 This looks at IFF involved in a dozen or so different markets/crime types involving developing countries in one way or another – often as a source (Table 5 below).

Table 5. Estimated values of transnational crime (US$ billions)

The 2011 Haken study was widely quoted,d7dbfaf02371 and other researchers developed a broadly supporting database, with some country detail, see for instance Havocscope. The latter partially addressed the problem of the risk of double counting by leaving aside any additional estimates from studies of corruption, tax evasion or money laundering.

Haken makes clear that the estimates may not relate to flows into or out of developing countries, as an estimate of the value of an illicit market does not say much about how much of that value will actually translate to cross-border transfers of funds (eg the drug trafficking estimates are well above what the supplier countries receive).affb823d9eb1 Even though the estimates may be difficult to define, source and reconcile, the question is whether this crime-based/market-based approach to estimating IFF gives more insight than the traditional NE&O and trade-data mismatch studies. The answer depends entirely on the quality of estimates, and not least, on whether they actually represent the realities of IFF in specific countries.

Investigating tax crimes leading to IFF