Query

Please summarise the evidence on the links between global flows of illicit finance and fragility and conflict.

Caveat

Fragility has increasingly come to be viewed as a complex multidimensional phenomenon (OECD 2022), which poses urgent and unique challenges to sustainable development (German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development 2019). However, while there exists an expansive literature on the role of corruption in generating and sustaining fragility, there are fewer studies on how illicit financial flows (IFFs) relate to “fragility”.

Much of the literature on fragile and conflict-affected states (FCS) (Green 2017; Kaplan 2008; Commission on State Fragility 2018; IMF 2022) has little to say about the role of financial flows, whether licit or illicit. On the other hand, while some studies of IFFs do examine the negative impact on low and middle-income countries (LMICs) (Cobham and Janský 2018; Brandt 2023), they do not tend to consider the effects on FCS in isolation from the wider group of developing countries.

An additional issue relates to “the amorphous nature of IFFs, both in their definition and in their measurement” (Collin 2020: 2). The term IFFs encompasses a wide range of phenomena and behaviour, from cross-border money laundering to tax avoidance. This has led to calls to “disaggregate” IFFs (Reuter 2017) by unpacking the concept to explore in greater detail the various drivers and consequences of specific illicit economies, be that gold smuggling networks, tax evasion schemes or the movement of the proceeds of corruption (OECD 2018a).

This Helpdesk Answer attempts to synthesise the evidence on how IFFs relate to fragility. Yet the breadth of both concepts implies that practitioners and policymakers need to consider the precise links between specific dimensions of these two phenomena at a more granular level. For instance, by exploring the connection in given locations between narcotics trafficking and security, corruption and political legitimacy or multinational profit shifting and economic inequality.

Background

In recent years, a robust consensus has emerged that IFFs have a “potent negative impact” on the capacity of societies to achieve sustainable and inclusive development (OECD 2018a). This deleterious impact is expressed in various ways, most obviously through the effect IFFs have in reducing government revenue by diverting resources away from legitimate economic activities. This constrains the fiscal space for governments to invest in public goods like infrastructure, healthcare and education, which can impose direct costs on core indicators of human development (OECD 2018a: 18). The association between untaxed offshore wealth and high inequality has also been well documented (IMF 2023b: 6).

Yet IFFs also have less obvious consequences, such as lowering the incentives of governing elites to address inequality and adhere to the rule of law, hollowing out the quality and legitimacy of state institutions, damaging public trust and social cohesion and ultimately “a deepening of state fragility” (Cobham and Janský 2017: 2; Moyo 2021).

IFFs can have detrimental impacts in countries where the funds end up, such as fuelling money laundering and market instability or distortions generated by the need to keep illicit flows hidden, such as real estate bubbles, banking crises and tax haven services (Collin 2020: 2). Nonetheless, source countries12db52403f57 are generally thought to be more severely affected given these tend to be LMICs in “dire need” of resources for development (UNCTAD 2020c).

Some authors are sceptical about the empirical basis for the claim that LMICs are disproportionately affected by IFFs, with Collin (2020: 2) noting that “there is not enough evidence […] that the share of revenue lost to IFFs is higher in developing countries” than developed countries. He also notes that, despite the big claims about the negative economic impacts of IFFs, these “at this stage are largely theoretical” (Collin 2020: 36), with the exception of studies that have focused on potential tax revenue lost to profit shifting (Crivelli, De Mooij, and Keen 2016; Cobham and Janský 2018) or undeclared wealth (Zucman 2013).

However, findings by UNCTAD (2020b: 132) suggest that even if the proportion of revenue lost to IFFs in LMICs is not markedly higher than in advanced economies, the impact this has is more severe in countries with high political instability, notably FCS. Taking countries that performed worst on the State Fragility Index as a proxy, UNCTAD (2020b: 132) finds that fragility increases the “marginal impact of each unit of lost capital” to IFFs, indicating that the most fragile countries are also the ones that are most affected in relative terms by the illicit outflow of funds. This is a point that Collin (2020: 2) does not dispute, as he notes that in “countries that already struggle to maintain basic social services, functioning institutions, and a viable social contract, revenue losses will be more damaging.”

Indeed, there is growing recognition that IFFs are especially destructive in FCS, given they “exacerbate weaknesses in public institutions, undermine governance and empower those who operate outside of the law”, allowing bad actors to perpetrate arms dealing, drug trafficking or illicitly trade in legal goods (OECD 2018a: 18), further corroding state authority. In this view, IFFs “contribute to vicious cycles of low development, instability and conflict” (OECD 2018a: 108). Collin (2020: 2) points out that the criminal activities underlying IFFs can be egregious, such as “violent crime associated with drug trafficking, government decisions distorted by corrupt practices, or outright kleptocracy/state capture of resources”. In turn, income from such criminal activities escapes taxation and productive investment, perpetuating a vicious cycle of instability (IMF 2023a: 5).

Against this backdrop, there are growing calls to foreground the impact of illicit finance in exacerbating fragility – and take action to clamp down on ill-gotten gains hidden in destination countries – from academics (Chigas 2023), civil society actors (Cohen 2018) and governments (Commission on State Fragility 2018: 6; German Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development 2019: 2).

Despite this enthusiasm, the OECD (2016a)offers a word of caution, noting that:

“fragile countries face a different set of IFF risks to stable and developed countries, and many of the measures required by the international normative framework are irrelevant […] these countries do not have the capacity or resources to implement the whole anti-IFF framework initially, and must make hard choices about which measures to prioritise, and how to sequence the measures they do take forward.”

Definitions

Illicit financial flows

IFFs is an umbrella term that covers a wide range of financial transactions that cross national borders and for which there is as yet no universally accepted definition (IMF 2023b). This paper adopts the concept endorsed by the UN Statistical Commission in March 2022: “IFFs are financial flows that are illicit in origin, transfer or use, that reflect an exchange of value and that cross country borders” (UNCTAD 2023a: 5).

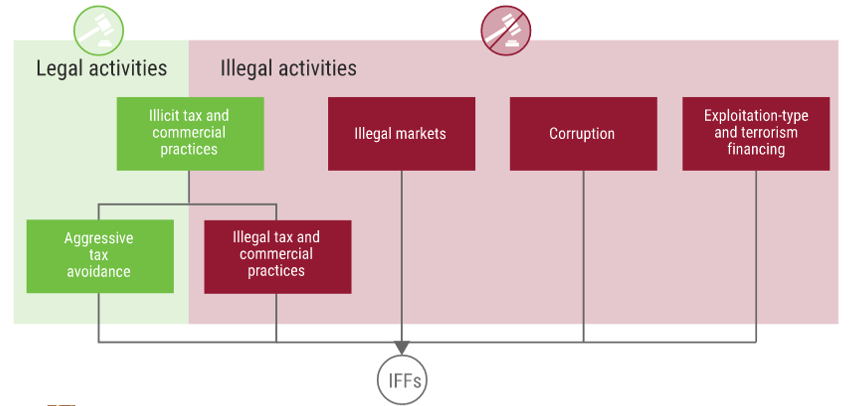

There are four main components of IFFs commonly identified in the literature (Cobham and Janský 2017; OECD 2016a; Reuter 2017; UNCTAD and UNODC 2020). As shown in Figure 1, these are:

- illegal tax and commercial practices (tax evasion, aggressive tax avoidance)

- illegal markets (from illicit goods and services, such as trafficking arms or narcotics)

- corruption

- exploitation-type activities such as modern slavery, extortion and human trafficking, as well as terrorism financing.521da9b0736f

As Reuter (2017: 3) notes, “each source [of IFFs] has different development consequences, both direct and indirect”.

Figure 1: Four main types of IFFs

UNCTAD 2020c.

Partly, the impact of IFFs will also depend on the channels used to move money. These vary according to the type of IFF and local context, ranging in sophistication from bulk cash smuggling and remittance transfers, to trade-based money laundering finance and the use of shell companies (OECD 2016a; Reuter 2017). Based on its analysis of 13 different illicit or criminal economies in West Africa that are linked to IFFs, the OECD (2018a: 107) identifies a wide range of possible harms and proposes that for each specific illicit economy careful diagnosis should “guide and diagnose” policy responses.

Box 1: Links between IFFs and corruption

Focusing on low-income states, Eriksson (2017) identifies five intersections between corruption and IFFs:

- Corruption facilitates the illegal activities that generate illicit funds.

- Corruption is itself a source of funds for IFFs.

- Corruption facilitates illegal transfers by incentivising oversight officials such as customs agents to look the other way.

- Corruption hollows out institutions that prevent or detect IFFs (such as financial intelligence units).

- Corruption facilitates the illegal use of funds once IFFs have crossed borders.

Historic cases of kleptocracies demonstrate a clear empirical link between corruption and IFFs: Sani Abacha (Nigeria), Valdimiro Montesinos (Peru), Ben Ali (Tunisia) and Ferdinand Marcos (Philippines) all moved embezzled funds to other countries to enjoy and safeguard these ill-gotten gains (Albisu Ardigo 2014: 2).

Fragility

The concept of fragility has been both slippery and contested since it rose to prominence in the 1990s. While the OECD, World Bank, the European Commission and bilateral donors all have their own idiosyncratic definitions of fragility (Olowu and Chanie 2016: 2), Kaplan (2014) contends that fragility has often been employed as a catchall term by development practitioners to explain virtually any governance problem in low-income countries. Stewart and Brown (2010) point out that the term itself is often considered politically provocative, and note that its use has in some cases negatively affected relationships between donors and recipient governments.

Early conceptualisations of fragility posited it as an expression of “state failure”; a state’s inability to assert its authority through a monopoly on and control of violence, lack of capacity to extract, manage and allocate resources, and weak legitimacy in terms of citizen acceptance of state rule (Grävingholt, Ziaja, and Kreibaum 2012). In recent decades, fragility has come to be seen as a more complex phenomenon that goes beyond the traditional focus on state structures, violence and economic growth (Eriksen 2010).

The OECD multidimensional fragility framework, introduced in 2016, sought to address these concerns by depicting fragility as a combination of exposure to risks and the coping capacities of states and communities to manage these risks (OECD 2016b: 75). The precise manifestation of fragility in any given setting is understood as the product of interaction between risks and coping capacities across five dimensions: societal, economic, environmental, political and security. While each fragile context is unique, the “mismatch between the risks they face and their capacities for coping” renders these countries more vulnerable to sudden crises or shocks (Roberts 2018).

As Cobham (2016) puts it, “in this view, fragility is closely related to a state’s ability to protect citizens from ‘negative’ insecurity (preventing personal, community, political and environmental insecurity) and provide them with ‘positive’ security (the conditions for economic, food and health security and progress)”.

Table 1. OECD’s five dimensions of fragility

|

Dimension |

Description |

|

Economic |

Vulnerability to risks stemming from weaknesses in economic foundations and human capital, including macroeconomic shocks, unequal growth and high youth unemployment. |

|

Environmental |

Vulnerability to environmental, climatic and health risks affecting citizens' lives and livelihoods. These include exposure to natural disasters, pollution and disease epidemics. |

|

Political |

Vulnerability to risks inherent in political processes, events or decisions; lack of political inclusiveness (including elites); transparency, corruption and society's ability to accommodate change and avoid oppression. |

|

Security |

Vulnerability of overall security to violence and crime, including both political and social violence. |

|

Societal |

Vulnerability to risks affecting societal cohesion that stem from both vertical and horizontal inequalities, including inequality among culturally defined or constructed groups and social cleavages. |

OECD 2016b: 73

This Helpdesk Answer adopts the OECD multidimensional fragility framework, as it provides a means of considering the range of impacts that different types of IFFs might have in different areas. Nevertheless, despite improving sophistication of the conceptualisation of “fragility”, there is still no comprehensive set of factors able to define fragile settings.735babd62e12 One should be wary of the “agglomeration of diverse criteria that throw a monolithic cloak over disparate problems that require tailored solutions” (Mazarr 2014: 116). As the OECD (2018b: 21) acknowledges, the challenge is to strike a balance between “recognising fragility’s complexity and translating this complex concept into practical policies and action”.

Characteristics of fragile and conflict-affected states

Certain characteristics of FCS make them especially vulnerable to the impact of IFFs, as depicted in Table 2, adapted from Commission on State Fragility (2018), OECD (2016a), (OECD 2018a: 109), Chigas (2023), Cobham (2016) and Collin (2020).

Table 2. Obstacles to tackling IFFs in FCS

|

Obstacle |

Description |

|

Political economy |

Governing elites may be deeply complicit in the underlying activities driving IFFs, such as extortion of commercial entities, embezzlement, illicit exploitation of natural resources and even organised crime. Officials may initiate illicit transactions across borders, protect illegal funds from seizure and criminals from prosecution, as well as launder money through legitimate businesses or international trade (OECD 2018a: 109). In such situations, “senior officials have a personal interest in financial opacity and the misuse of public funds, and fiscal policy is subordinated to […] allocation for patronage purposes” (Cobham 2016). Ordinary citizens may likewise be entangled in illegal markets, as such criminal “economies often provide basic livelihoods” (OECD 2018a: 108). In FCS, it is thus likely to be difficult to identify reformers with the political commitment and clout needed to tackle IFFs. |

|

Lack of capacity and resources |

Resource and capacity constraints are magnified in FCS. This may affect customs and border agencies, and affect coordination with foreign law enforcement bodies that track IFFs. |

|

Missing institutions

|

The agencies and institutions to counter illicit financial flows may not exist at all, and existing agencies may be unable to take on IFF responsibilities in addition to their core business. |

|

Coordination with other countries and international organisations |

National plans and priorities can be distorted by the objectives and conditions set by external partners, which can weaken national ownership and lead to incoherent policies. Governments in FCS are less likely to comply with international AML/CFT standards, or to have negotiated tax-information exchange agreements with other countries. |

|

Incomplete legal frameworks

|

Combating IFFs requires a large amount of detailed legislation on a range of topics. In many countries, the legal framework is confused, including laws from several sources and even different legal traditions; there may be duplicative and redundant laws, and provisions that could undermine measures to counter IFFs. As a result, the financial sector is likely to be effectively unregulated in many FCS. |

|

Security and rule of law

|

FCS are more likely to experience high corruption, informality and organised crime, which are major sources of IFFs. In addition, insecurity and inability to enforce laws can undermine measures to reduce IFFs. |

Due to these factors, authorities in FCS are less equipped to detect IFFs or deal with the underlying practices that generate them. Brandt (2023) observes that, empirically, countries with low regulatory quality and administrative capacity are more vulnerable to IFFs “both relative to the size of the economy and relative to total tax revenues”. Quantitative estimates on the scale of the damage are presented in the next section.

Measuring illicit financial flows from FCS

There are numerous approaches to measure the scale of IFFs, of which the most prominent involve looking for discrepancies in balance of payments, trade gap analyses and trade price deviation analyses (Collin 2020). Such measurement attempts all contain a very significant margin of error, given the large variation in sources, channels and nature of IFFs, as well as the lack of data due to the hidden nature of the phenomenon. Particular difficulties are encountered when trying to detect and trace flows such as hawala transfers or cash transactions (Global Financial Integrity 2019; Kotecha 2020: 74).a35f08cf713f

Estimates of the scale of the problem typically conclude that illicit financial outflows from LMICs outweigh incoming official development assistance (ODA). For example, UNCTAD (2020b) states that annual capital flight from Africa is US$88.6 billion, while inward ODA is worth US$48 and foreign direct investment is around US$54 billion.

Yet given the margin of error involved in such estimates, attempts are increasing being made to provide “bottom-up” estimates of the scale of IFFs at the country level, as these are seen to be more relevant for policymaking (Collin 2020: 36; IMF 2023b: 15).dfa99fce3cdb Some of these relate to FCS and provide a sense of the magnitude of the problem.

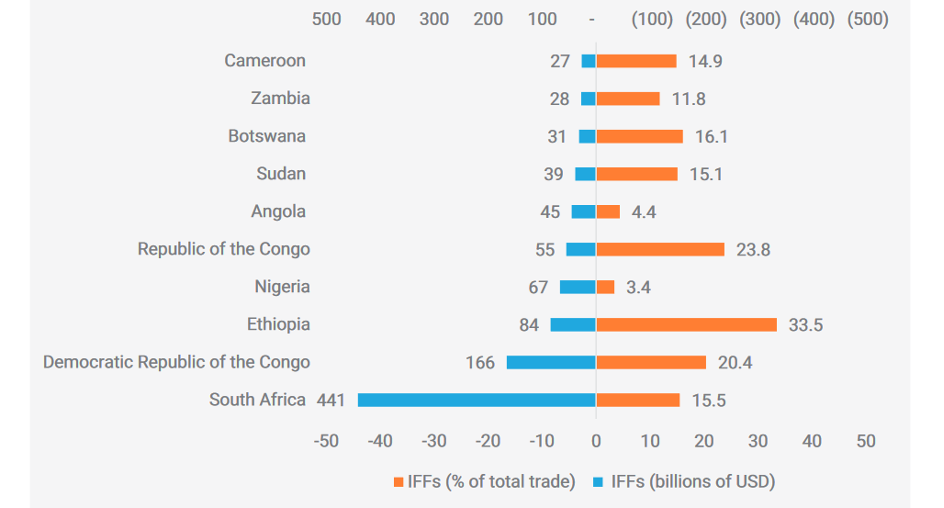

In 2021 and 2022, for instance, UNCTAD (2023a: 14) piloted various methodologies to track the scale of different types of IFFs across selected sub-Saharan countries. For example, in Burkina Faso, trade misinvoicing was calculated to account for US$6.8 billion in IFFs, mostly stemming from the petroleum industry. More generally, as shown in Figure 2, illicit financial outflows from Africa are estimated to be in the range of tens of billions of dollars a year, with FCS such as the Democratic Republic of Congo, the Republic of Congo and Ethiopia especially severely affected in terms of the percentage of their total trade accounted for by IFFs.

Figure 2: Top 10 African countries with highest total IFFs, 1980-2018

UN Office of the Special Adviser on Africa 2022.

Fragility and IFFs: a vicious cycle

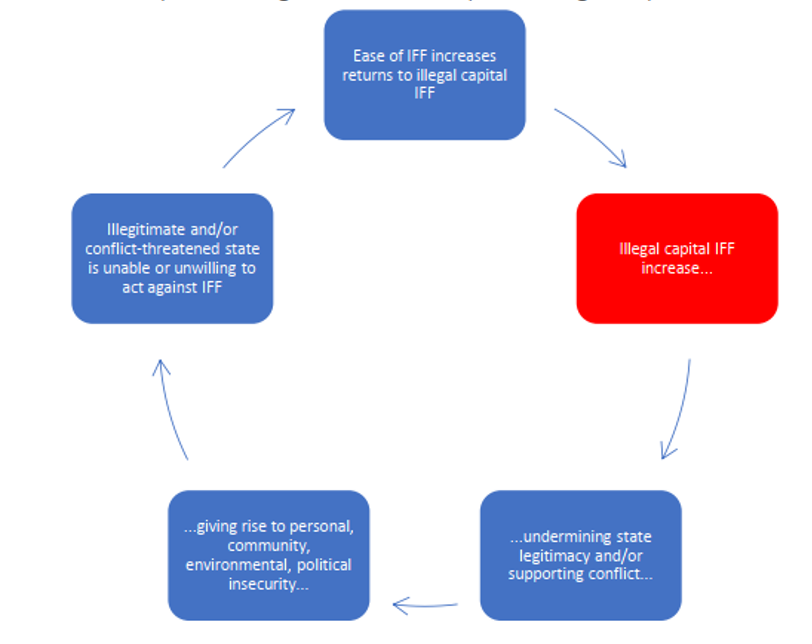

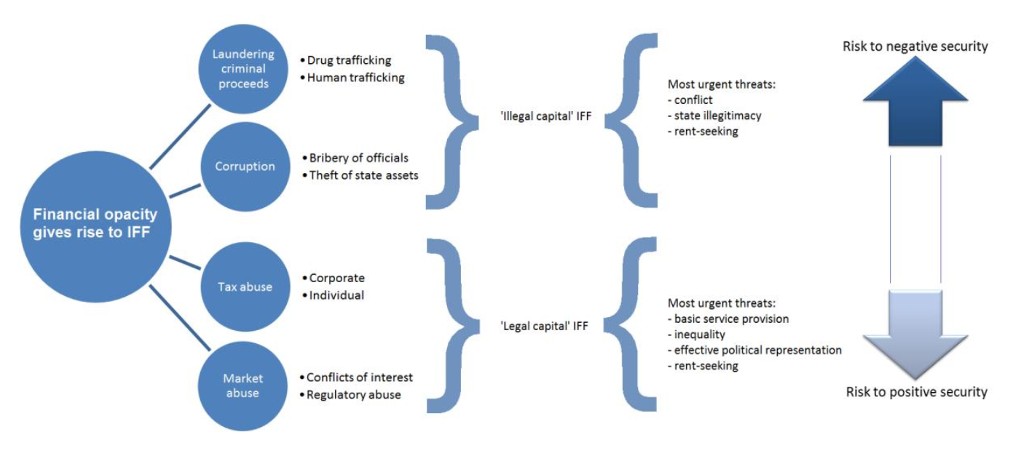

Some scholars have pointed to a symbiotic relationship between IFFs and fragility, with causality operating in both directions: fragility creates enabling conditions and incentive structures that generate IFFs, while the outflow of resources from these states further exacerbates fragility (Herkenrath 2014; Cobham and Janský 2017).

Specifically, Cobham and Janský (2017: 11) argue that illegal activities associated with IFFs:

“give rise to a vicious cycle of negative insecurity, in which the growth of IFFs further undermines the state’s legitimacy and/or fuels internal conflict, weakening in turn the state’s will or ability to act against IFFs, and so increasing the returns to the underlying activity and the incentives to take part.”

Figure 3: The vicious cycle of negative insecurity and illegal capital IFF

Cobham 2014.

Cobham (2016) implies that the cycle of negative insecurity is especially pronounced in FCS.32fc662c7870 Herkenrath (2014) likewise suggests that illicit outflows from FCS are more likely to stem from illegal sources, whereas IFFs related to tax evasion mostly originate in “middle-income countries with relatively well-developed tax systems”.

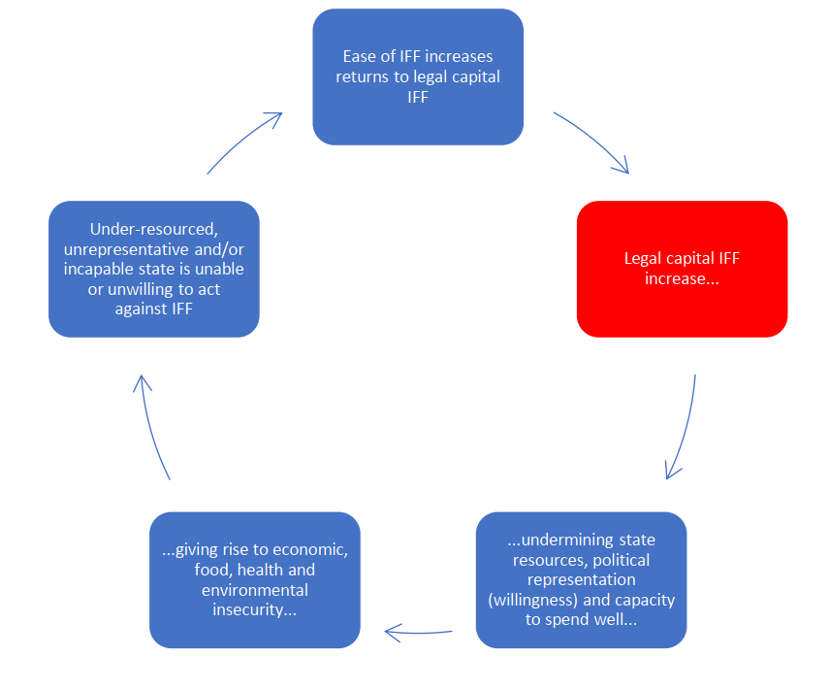

Cobham and Janský (2017: 12) also propose a vicious cycle of the absence of positive security, in which states are unable to appear responsive to citizen needs or provide the conditions necessary for sustainable peace, such as food security, health, education and environmental regulation. In this view, IFFs arising primarily from commercial tax avoidance deprive states of:

“both the available revenues to provide positive security, but also the political responsiveness to be willing to do so. The resulting insecurity and inequalities have the potential to further weaken both the capacity and the willingness of the state to fight IFF, reinforcing the cycle.”

Figure 4: The vicious cycle of positive security and legal capital IFF

Cobham 2014.

There is some empirical basis for the circular nature of the relationship. In a quantitative country comparison study by Cerra, Rishi, and Saxena (2008), the strongest predictor of the present level of IFFs was found to be the historical extent of IFFs in that country. The remaining sections of this Helpdesk Answer consider links between IFFs and fragility.

The macroeconomic effects of IFFs on FCS

The structural impact of IFFs in macroeconomic terms is a growing field of study, and there is an emerging consensus that illicit outflows damage economic growth, productivity and socio-economic development in source countries. There are three major reasons for this: IFFs reduce private capital accumulation, erode government revenue and discourage private and public investment (UNCTAD 2020b: 129).

IFFs are associated with a wide range of negative macroeconomic effects, many of which were recently documented by the IMF (2023b). First, revenue leaks caused by IFFs impede source countries’ domestic revenue mobilisation, which enhances the dependence of FCS on development aid and humanitarian assistance. Chehade, Tolzmann, and Notta (2021), for instance, argue that IFFs are partly responsible for the fact that “70% of fragile countries have a tax-to-GDP ratio below the minimum 15% needed to finance basic services”, while “almost half of official development assistance [is] used for humanitarian purposes or peace financing.”

Second, significant illicit outflows can distort source countries’ balance of payments, affect asset prices and reduce foreign reserves. Third, by lowering the rate of capital accumulation and thereby reducing private investment, IFFs can lead to diminished productivity (Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard 2020: 8). Fourth, capital outflows can precipitate a depreciation of the national currency, increasing the cost of investment and imports (Ampah and Kiss 2019). Fifth, IFFs can have deleterious effects on the fiscal position and indebtedness of source countries. This is because extensive capital flight might compel governments to increase external borrowing, while foreign loans can “trigger debt-fuelled capital flight” in which loans “guaranteed by the government flow immediately and directly into foreign private accounts” (Herkenrath 2014). Sixth, the shortage of capital associated with IFFs could increase the domestic interest rate, which can make it even harder for borrowers to service external debts (UNCTAD 2020b: 130).

Finally, criminal activities underlying IFFs can be significant enough to have macroeconomic effects, such as where grand corruption and rampant embezzlement leads to the gross misallocation of public resources, or where organised crime deepens the informality of the economy and distorts markets in legal goods (IMF 2023b).

Several authors have attempted to quantitatively estimate the macroeconomic impact of IFFs. A study by Spanjers and Foss (2015) of how trade misinvoicing affected 82 LMICs between 2008 and 2012 found that 40 countries had illicit flows accounting for at least 10% of the country’s total trade value, while 20 nations had illicit flows amounting to more than the combined value of development assistance and foreign direct investment. Looking at revenue loss from corporate tax avoidance, Cobham and Janský (2018) estimate total global losses of approximately US$500 billion per year. UNCTAD (2020c) suggest that “IFFs may reach even a half of officially recorded trade”, while other studies estimate that between 20% to 30% of private wealth in many LMICs is held in tax havens (Zucman 2014; Johannesen, Tørsløv, and Wier 2020).

Crivelli, De Mooij, and Keen (2016) estimated that, across all lower income countries, annual corporate income tax revenue loss is US$200 billion, equating to 1.3% of their GDP. A later study by UNCTAD (2020b) suggested that the value of illicit capital flight each year from Africa alone is around US$88.6 billion, which equates to 3.7% of Africa’s GDP. At the national level, Ogbonnaya and Ogechuckwu (2017) found that IFFs have a significant negative effect on economic growth rates and GDP per capita in Nigeria.

There is consensus that resource-rich and low-income FCS are the most acutely affected by the impact of IFF outflows (IMF 2023b: 32; Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard 2020). This leads some scholars to conclude that IFFs “cause low productivity traps that […] ultimately result in locking many African countries into a low-income trap” (Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard 2020: 35).

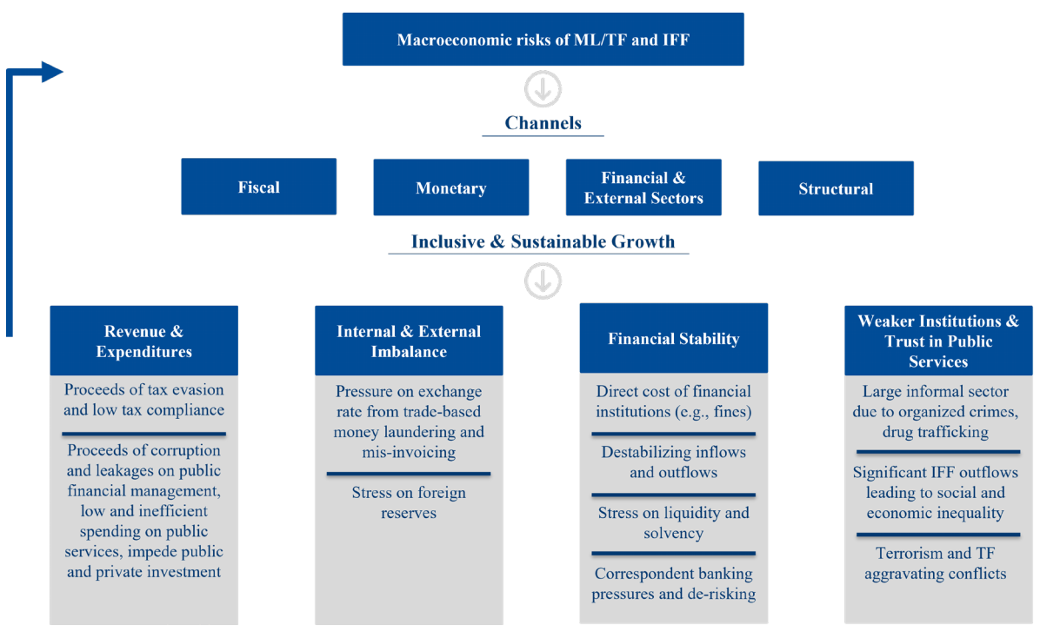

The various macroeconomic impacts of money laundering, terrorist financing, and IFFs were illustrated in a recent IMF report, as depicted in Figure 5.

Figure 5: The macroeconomic impact of ML/TF and IFFs

IMF 2023a: 9.

Recent IMF Article IV reviews of countries listed by the World Bank as FCS (including Mali and Niger) demonstrate that inadequate AML/CFT frameworks in these countries have severe impacts on fiscal and structural reforms (IMF 2023a: 17). The IMF (2023a: 8-9) nonetheless points to significant differences between the consequences on FCS of i) money laundering and ii) terrorist financing. In source countries, money laundering encourages “significant illicit financial outflows” and impedes domestic revenue mobilisation, ultimately affecting financial stability. Terrorist financing, on the other hand, is chiefly “macro-relevant” for FCS “where terrorist groups derive income from their control over natural resources”.

UNCTAD (2023b) estimates for countries on the World Bank FCS list include that the exports of opiates from Afghanistan generated between US$1,300 million and US$2,233 million in IFFs per year, and between US$508 million and US$1,347 million per year in Myanmar. In Nepal, heroin trafficking was estimated to generate IFFs similar to the value of imports of pharmaceutical goods (UNCTAD 2020c), while in Peru, IFFs related to cocaine trafficking were thought to represent between 3.5% and 4.5% of total exports (UNCTAD 2020c).

Completing the vicious cycle, fragility itself has “macro-critical” implications for the economy, as it destabilises “balance of payments positions, [and] disrupt[s] trade and financial flows” (IMF 2022: 1)

While the macroeconomic impact of IFFs on FCS is therefore clearly substantial, it is apparent that IFFs also affect various other dimensions of fragility, including the quality of political institutions, social cohesion, inequality and environmental factors(Maton and Daniel 2012; Moore 2012; Torvik 2009). The next section therefore turns to the broader ramifications of IFFs for FCS.

The broader impacts of IFFs on fragile and conflict-affected states

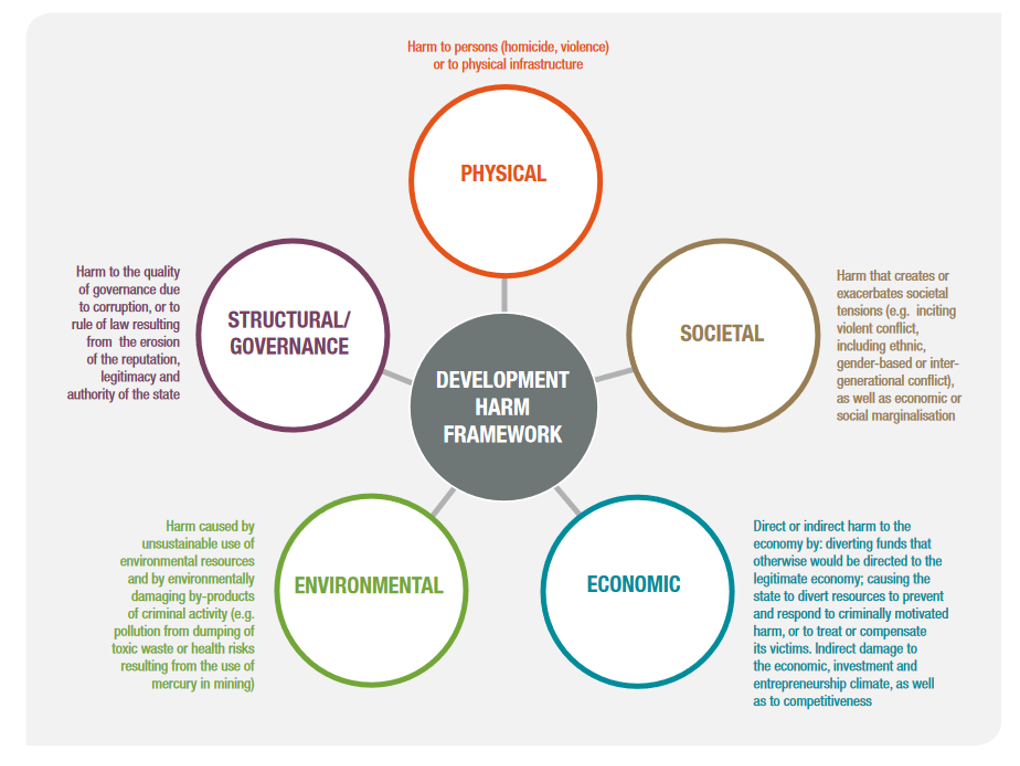

The consequences of IFFs are multidimensional in nature. In addition to the macroeconomic impact described above, the effects on the quality of institutions, environmental sustainability and armed conflict are common themes in the literature (UNCTAD 2020b; Vittori 2018; Cobham and Janský 2017).

Cobham (2014) has attempted to map the multidimensional impacts of IFFs on both “negative” and “positive” security, which shed light on the diverse effects that IFFs could have on the drivers of fragility.

Figure 6: The multidimensional effects of IFFs

Cobham 2014.

In a study of IFFs in West Africa, the OECD (2018a: 24-25, 58-59) examined the impact of IFFs across five categories that closely mirror the dimensions of fragility discussed above: governance, societal, economic, environmental and physical (Figure 7).

Figure 7: A framework for assessing harm to development resulting from illicit and criminal activities, and the associated financial flows

OECD 2018a.

The OECD (2018a: 25) recommends applying this 5 pillar framework to study specific criminal economies “to better understand the extent and nature of the harm stemming from illicit and criminal activities”. This section of the Helpdesk Answer adopts the framework but remains at a higher level of abstraction, documenting illustrative connections between each pillar and IFFs in FCS.

While considered in isolation in this paper for analytical ease, there are clear overlaps between pillars. For example, where IFFs are generated by militant groups’ control of natural resources or drug trafficking by organised criminals, these are likely to have effects across multiple pillars. Indeed, as UNCTAD (2020b: 131) points out, “the relationship between IFFs and structural transformation is driven by the combined effect of different channels, rather than each channel separately”.

Governance

There is mounting evidence that IFFs and the activities associated with them can generate political tensions in society and damage the quality of governance institutions, which reduces society’s ability to cope with political pressures and heightens fragility. In particular, higher volumes of illicit outflows are associated with the development of political settlements in source countries that centre on state capture by narrow interest groups and rely on patronage networks to sustain themselves (UN ECA 2015; Lain et al. 2017). There is also some indication that political fragility itself can incentivise these interest groups to remove wealth from the country and weaken checks on financial transactions, making it easier for them to do so.

It thus appears that IFFs “are a consequence of weak institutions and [...] they also contribute to weakening them even further” (Herkenrath 2014). As Bak (2020: 15) puts it,IFFs form an intrinsic part of a vicious cycle of “state capture, neo-patrimonial governance, decline in state legitimacy and accountability, and ultimately increased fragility, criminality and conflict”.

How IFFs relate to political fragility

Herkenrath (2014) argues that IFFs produce political dynamics that lead to the intentional “weakening of state institutions and growing corruption and rent-seeking”, of the type that aggravates fragility.

First, the criminal activities underlying IFFs can be deeply damaging to the state, particularly those associated with the funding of terrorism and transnational organised crime, such as trafficking in drugs, arms and people. Reuter (2017: 7) suggests that IFFs resulting from proceeds of corruption have more direct and negative impact on political institutions than other sources of IFFs. Cobham and Janský (2017: 11) concur, pointing out that corruption is a major source of IFFs in FCS and undermine state capacity. For example, bribery subverts state power for the private gain of business interests, while embezzlement of state funds by officials hollows out state capacity. Le Billon (2003) argues that when corruption becomes a channel for those in power to trade public resources for political or economic support to retain power, opposition groups or those excluded from access to government rents have higher incentives to resort to violence to secure and/or contest access to these ill-gotten gains.

Second, the ability to launder and enjoy illicit profits abroad can distort public policymaking in harmful ways. Moore (2012: 474) argues that in states with “little or no effective institutionalised popular control over the actions of political elites”, officials “willing to participate in this nexus of corrupt internal accumulation and illicit capital outflows are also motivated and able to create or change the rules of the game to ensure that they can continue playing it in a rewarding way”. In this view, political elites complicit in IFFs therefore take steps to neutralise potential institutional checks on the flow of dirty money, such as capturing tax agencies, law enforcement, judicial organs, audit bodies, legislatures and political parties. In this way, IFFs weaken mechanisms of accountability (Ndikumana 2014).

Herkenrath (2014) agrees, proposing that the unchecked outflow of illicit finance can stimulate the “emergence of a veritable rent-seeking economy”. He argues that the possibility of spending ill-gotten gains overseas provides corrupt officials with even greater incentives to “enact regulations and channel public investments towards sectors that offer the best opportunities for bribery”, while in the presence of venal officials, businesses are incentivised to invest surpluses not in productive activities but rather in buying political support to obtain privileges and handouts (Herkenrath 2014). However, it remains unclear to what extent the ability to spend the proceeds of corruption abroad stimulates additional venality on the part of officials (Collin 2020: 36).

Third, once political and economic elites have moved most of their wealth abroad, Reuter (2017: 2) suggests that they become less concerned about upholding the rule of law and property rights domestically, which further reduces constraints on their abuse of power at home. This is corroborated by a study by Ndiaye (2014) of the CFA-Franc-Zone from 1970 to 2010, which found that capital flight is associated with reduced constraints on executive power. Conceivably, where elites are less reliant on legitimate tax revenue, they feel less answerable to citizens (Cobham 2016). Moreover, revelations that elites are moving large quantities of money out of the country can also lead to the collapse of public trust in government (Reuter 2017: 8). This is in line with findings that tax evasion is correlated with popular perceptions of state legitimacy (Hammar, Jagers, and Nordblom 2006).

Fourth, the use of illicit funds can have destabilising political influences. This can include financing election interference by malicious foreign actors(Reuter 2017: 8; Bak 2021). More fundamentally, those profiting from IFFs can invest their wealth to obtain political clout and then leverage this influence to benefit their client networks. Such corruption leads to public officials becoming ensnared in larger patron-client networks that are often involved in criminal markets, with a resulting disregard for these officials’ formal duties. A common feature of IFFs is the confluence of bureaucrats, political elites, businesspeople, professional enablers, organised criminal groups and occasionally violent extremists (Lain et al. 2017). As a result, IFFs can increase state fragility as they weaken state capacity and result in the proliferation of a range of actors who impose socio-economic costs on local communities(Bak 2020: 11-12).

How political fragility enables IFFs

Given that “poor institutional quality is both an enabler and a consequence of IFFs” (Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard 2020: 3), it is no surprise that political fragility can provide further opportunities for illicit financial transactions. Moore (2012: 474) describes how the opportunity to covertly transfer the illicit capital to tax havens overseas with impunity – largely a product of dysfunctional political institutions – “is a direct stimulus to corruption and other illicit activities” as it alters perpetrators’ cost-benefit analysis. Andersen et al. (2017) use data from the Bank of International Settlements to show how commodity earnings in polities with weak political institutions are associated with a notable increase in private bank holdings in tax havens. In autocratic countries, they estimate that approximately 8% of state oil revenues are captured and held as private assets abroad. Concerningly, UNCTAD (2020b: 132) finds that political instability increases the marginal impact of each unit of capital lost to IFFs.

The Norwegian Government Commission on Capital Flight from Poor Countries (2009: 82-84) argues that some regimes in low-income countries systematically weaken state institutions to accumulate private fortunes and secretly transfer them overseas. Baker and Milne (2015) substantiate this claim, arguing that state actors across southeast Asia have adopted a conscious strategy of placing themselves at the centre of networks of illicit flows. The authors coin the term “dirty money states” to describe regimes that deliberately weaken state capacity in some spheres, such as traditional forms of taxation, to allow political elites to generate income from illicit activities, including illegal logging and mining, as well as trafficking arms, drugs and people. Given the widespread view that the quality of institutions is a key determinant of economic development (Robinson and Acemoglu 2012; Subramanian, Trebbi, and Rodrik 2002), political regimes that finance their consolidation through IFFs have neither the institutional infrastructure nor incentive structures needed to address the root causes of fragility.

Societal

The fragility of a state is not only shaped by the forces that attempt to undermine or confront it (negative security) but also by its ability to provide essential goods and services for its citizens (positive security) (Cobham 2016). If a state cannot provide economic opportunities or basic social security, the ensuing grievances and rejection of dysfunctional public institutions can play into the hands of insurgent and criminal organisations able to provide surrogate structures (Albisu Ardigo 2014).

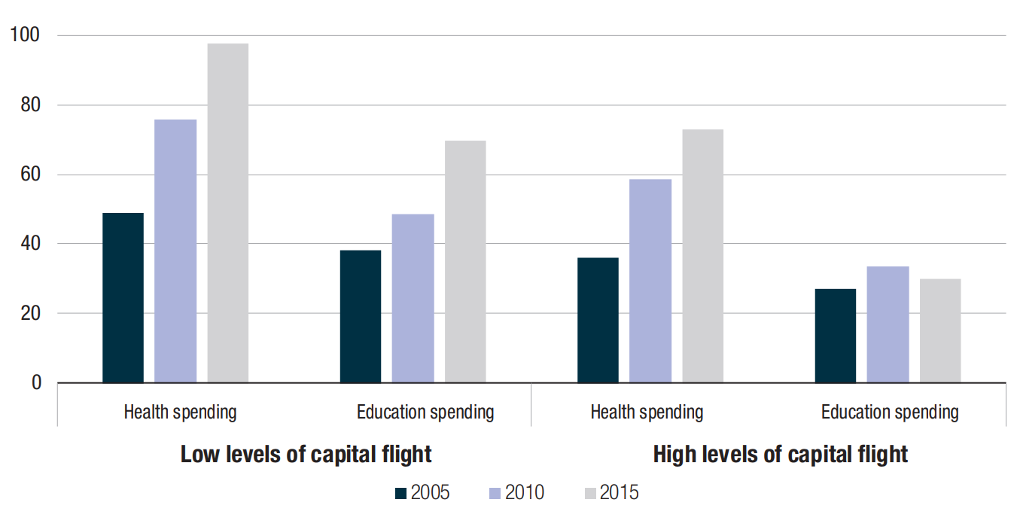

A well documented effect of IFFs is reducing domestic revenue mobilisation (DRM) in source countries, which has implications for government spending in sectors like health, education and public infrastructure (UNCTAD 2020b: 130). In a study of 89 LMICs, for instance, Reeves et al. (2015) demonstrate that “tax revenue was a major statistical determinant of progress towards universal health coverage”. Yet, Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard (2020: 13) observe that high capital flight is associated with less spending on health and education.

Thus, not only do IFFs encourage the development of political settlements that cater to a narrow political elite and encourage the emergence of a highly unequal social order, they also “obstruct a broad-based development trajectory that could help alleviate mass poverty” (Bak 2020: 12).

How IFFs relate to social fragility

IFFs undercut state attempts to mobilise domestic revenues, reducing national tax take and lowering the tax base (UN ECA 2015). Domestic revenue mobilisation is a primary measure of state capacity and is, together with state expenditure, linked to mutual accountability between state and citizen as part of the social contract (Bak 2020: 9). As such, the inability of FCS to mobilise sufficient domestic revenue to fund social spending is widely recognised as a key constraint on development as well as a driver of inequality (OECD 2018b). Herkenrath (2014), for example, argues that IFFs damage social cohesion through two channels: by undermining the provision of basic public goods and services (thereby weakening the legitimacy of the political system), and by shifting the costs of what public spending does occur to the poorer sections of society.eb75d024bd7d

The FACTI Panel (2021: vii) observes that “given the magnitude of illicit outflows, these resources, if recovered or retained, have immense transformative potential” in areas such as water, sanitation, electricity, healthcare and housing.

According to UNCTAD (2020b), curbing IFFs could almost halve the US$200 billion annual financing gap Africa faces to achieve the SDGs. The “spoiler effects” of IFFs in diverting much-needed resources away from public coffers and into tax havens are particularly acute in FCS (OECD No date). Research has found that states with high levels of capital spend an average of 25% less on health and 58% less on education than countries with low levels of capital flight (UNCTAD 2020b: 152).

Figure 8: Africa: Total health and education expenditure, median by level of capital flight (dollars per capita)

UNCTAD 2020b: 157.

Unsurprisingly, the societal effects of IFFs are not equally felt; poorer people more reliant on the government for social services are most affected (UNCTAD 2023a), and women and girls are hardest hit by lower spending on health and education (Musindarwezo 2018). A substantial scholarship has arisen estimating the opportunity cost of resources lost to IFFs in LMICs.

At an aggregate level, the under-5 mortality rate in countries with high levels of capital flight relative to GDP was found to be slightly higher (59) than in states with lower rates of capital flight (55) (UNCTAD 2020b: 157). In a study of 34 sub-Saharan African countries, O'Hare et al. (2014) show that a curtailment of illicit flows could see substantial infant mortality reductions. At country level, (UNCTAD 2020a) suggests that if the amount lost to capital flight in Sierra Leone were invested in public health, an additional 2,322 children per year could survive infancy. In the Republic of Congo, illicit flows were estimated to equate to almost five times (483.5%) what the government spent on the public health system (Spanjers and Foss 2015).

Fewer estimates are available for education, but examining trade misinvoicing as a source of IFFs in 82 countries between 2008-2012, Spanjers and Foss (2015) find that 40% of them had illicit outflows exceeding public spending on education. Looking specifically at resource-rich developing countries, Bhorat et al. (2017) calculated that IFFs as a percentage of total public spending on health and education tend to be above 10%.

Chigas (2023) points to the implications on social cohesion of states with no effective social safety net, as this renders people more reliant on “in-groups”, such as those based on kinship, which can heighten social tensions. The OECD (2016a) emphasises how IFFs can “frustrate efforts to redistribute wealth” and therefore sustain social inequities. Overall, IFFs are associated with worse economic outcomes, lower levels of public service provision and a more unequal tax burden. As a result, IFFs not only exclude the poorest and most marginalised citizens from the benefits of economic growth and development but actively harm them (Bak 2020: 15).

Environmental

The links between poor governance, extractive industries and natural resource dependency is well established. The extractives sector is especially vulnerable to IFFs given its “complex value chains and transnational ownership structures, high-level of discretionary political control, and difficultly of monitoring outputs”(IMF 2023b). Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard (2020: 10) observe, however, that despite the prevalence of IFFs in extractive industries, “the association of illicit financial flows with environmental performance has received little attention”.

Nevertheless, several studies do identify a causal connection between IFFs and environmental degradation, which, by negatively affecting the health of the population and fuelling climate change, could catalyse fragility. UNCTAD (2020b: 144) points to a reciprocal relationship, where illicit outflows undermine public spending on environmental protections and climate change mitigation, and inadequate environmental safeguards and low enforcement “increase the incidence of illicit resource exploitation and capital outflows in extractive industries”. The same report estimates that curbing illicit capital flight could generate enough capital by 2030 to finance almost half of the US$2.4 trillion needed by sub-Saharan African countries for climate change adaptation and mitigation (UNCTAD 2020b: 164).

How IFFs relate to environmental fragility

According to the OECD (2016a), IFFs are key enablers of the “illegal and unsustainable mineral extraction, forestry, fishing, or trade in wildlife”. Not only does a large proportion of total IFFs stem from the illicit exploitation of environmental resources but these are often associated with “the unsustainable use of finite natural resources” (Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard 2020: 10) which have “severe environmental impacts” (UNCTAD 2020b: 143-4). Such scenarios can lead to violent land disputes, the displacement of already vulnerable sectors of the population and to increasing levels of poverty and hunger (Chene and Jaitner 2018), thus exacerbating fragility in local communities (Bak 2020: 11-12).Indeed, according to Herkenrath (2014), IFFs “are partly responsible for the fact that the commodity wealth of many least developed countries has not translated into developmental progress, but into a veritable resource curse”.

Environmental crime is an important source of IFFs, generating anywhere between US$110 billion to US$281 billion per year (Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard 2020: 10). The profits from these criminal activities create opportunities for corruption and money laundering and have wider destabilising effects. For example, the illicit mining of minerals and fuel smuggling are particularly significant issues in Africa (UNCTAD 2020b: 142), and these illicit trades stimulate conflict, fund armed groups, and lead to human rights abuses. Shaw, Nellemann, and Stock (2018) estimate that 38% of all illicit flows to non-state armed groups in conflict originate in the illicit extraction of natural resources, more than any other source of IFF.

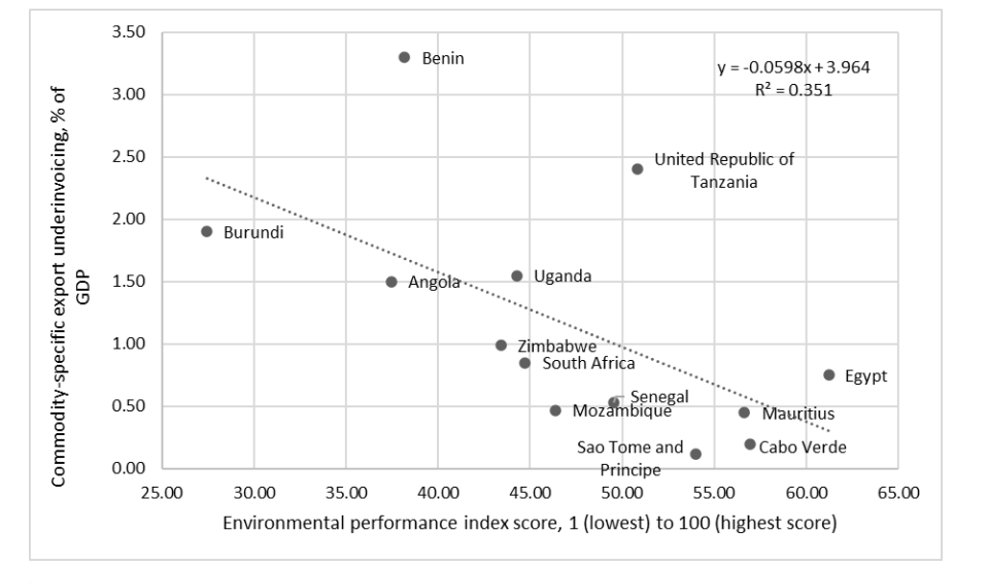

At the aggregate level, countries with higher rates of commodity related underinvoicing perform worse, on average, in terms of environmental policies as depicted in Figure 9 (Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard 2020: 15).

Figure 9: Environmental Performance Index and commodity-specific export underinvoicing (as percent of GDP), in 2018

Slany, Cherel-Robson, and Picard 2020: 15.

In addition, UNCTAD (2020b: 146) reports that “countries with high IFFs [outflows] have only 1/3 of the agriculture productivity levels of countries with low IFFs”. The causal mechanisms are thought to be the lack of available resources for investment to increase productivity, as well as the fact that illicit financial outflows are associated with the devaluation of local currencies, which increases the cost of imported fertiliser (UNCTAD 2020b: 147).

Finally, looking at the critical minerals sector in South Africa, Rakei (2022: 14) concludes that the scale of IFFs associated with the industry obstructs efforts to transition to a greener, low carbon economy, because IFFs reduce legitimate capital accumulation that could be invested in energy transition.

How environmental fragility enables IFFs

UNCTAD (2020b: 143-4) states that poor enforcement of environmental protections – which could indicate environmental fragility - facilitates the “illicit exploitation and trade of natural resources”. According to the Natural Resources Governance Institute (2021), FCS whose chief exports include oil and petroleum are the countries most heavily affected by illicit outflows. Indeed, Bhorat et al. (2017) have demonstrated that resource-rich states tend to have the highest IFF-to-GDP ratios. This could indicate that in countries where regulation and oversight of natural resources is weak and the environment especially fragile, extractive industry revenues are more likely to leave the country in the form of an IFF.

Economic

A previous section considered the macroeconomic effects of IFFs. This section examines in more detail the mechanisms by which the economic causes and consequences of IFFs could affect drivers of fragility, such as inequality and financial exclusion. As UNCTAD (2020b: 136) writes, the “the lower the level of state fragility, the more stable is the overall business environment and the less is the direct negative impact of IFFs”.

How IFFs relate to economic fragility

Nkurunziza (2012) argues that IFFs act as a powerful constraint on poverty reduction in Africa, by hindering inclusive economic growth. The economic consequences are not felt equally. IFFs provide an opportunity for the richest segments of society to opt out of the social contract with the state, by evading their economic obligations. The AfDB et al. (2012: 73) states that virtually everyone implicated in capital flight in Africa is part of the richest 10% of society. The rest of the population does not have that luxury, and the poor in particular will lose out from lower levels of investment and government spending (UNCTAD 2020b: 138), particularly in social sectors such as health and education, as mentioned above. Signé, Sow, and Madden (2020) estimate that had illicit outflows from Africa been invested efficiently, this could have reduced the poverty rate by an additional 4% to 6%.

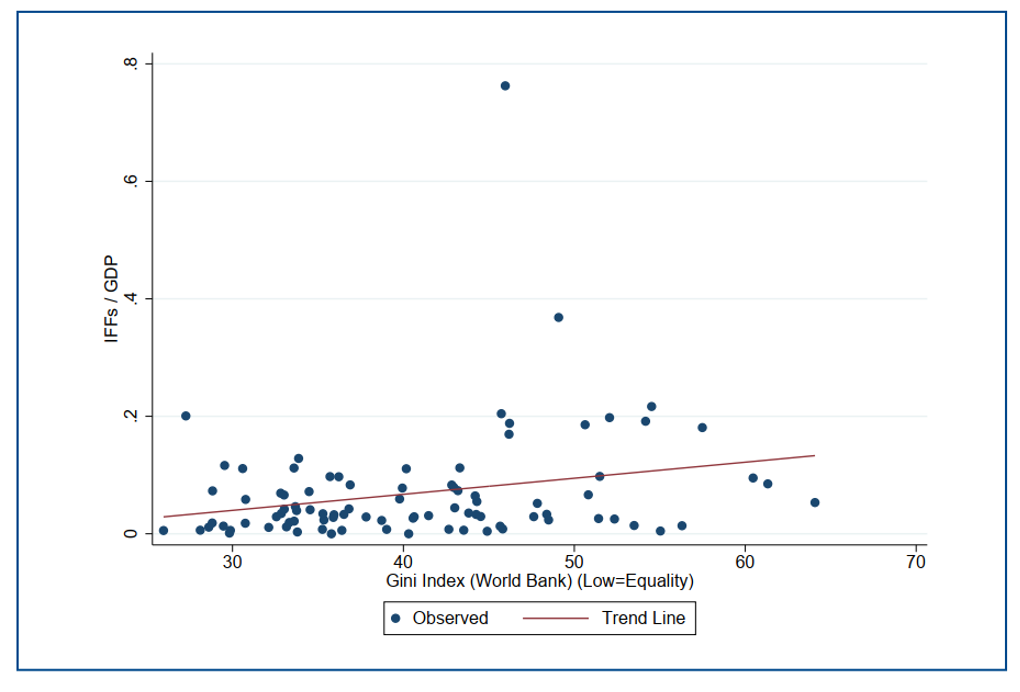

Lower inequality is strongly correlated with faster and more sustainable economic growth (Berg et al. 2018). Yet not only does the very existence of “IFFs imply an unequal distribution of wealth” (UNCTAD 2020b: 138), but illicit outflows act as an accelerant on inequality.Bak (2020: 1) argues that IFFs reproduce inequality in several ways. First, IFFs are associated with less efficient economic outcomes, lower rates of poverty reduction and more rent-seeking behaviour. Second, IFFs reduce state capacity and the revenues needed to finance development and state building. Third, IFFs shift the tax burden towards the middle and lower ends of the income distribution spectrum (Coplin and Nwafor 2019). The response of some governments in LMICs to declining revenue collection, partly attributable to IFFs, has been to increase forms of taxation that target household consumption and thus disproportionately affect the poor. In other countries, the perception that the tax burden is unfairly distributed has caused the middle class to opt out of state service provision and demand tax cuts, which further decrease the quantity and quality of social welfare available to the poor (Alonso-Terme 2014). Fourth, IFFs are often associated with state capture and deteriorating institutional quality, political arrangements likely to frustrate redistributive policies.

Against that backdrop, Global Financial Integrity (2015: 4) argues that these numbers also show that “there is perhaps no greater driver of inequality within developing countries than the combination of illicit financial flows and offshore tax havens”. There is some empirical evidence to support this view. As Spanjers and Foss (2015: 19) find, higher income inequality – as measured by the Gini coefficient – is positively correlated with greater illicit outflows, and they suggest there is a vicious circle in which IFFs exacerbate inequality and vice versa.

Figure 10 Illicit financial outflows and income inequality (Gini coefficient)*

* “A weakness of this index is that it is based on official income surveys, which do not capture illicit assets and income; if they did, the inequality measure would likely be much worse. As such, official Gini coefficients tend to understate inequality.”

Spanjers and Foss 2015: 20.

How economic fragility enables IFFs

Some characteristics of economic fragility may enable an increase in both the volume and impact of IFFs. Specifically, the structure of the economy in FCS can affect the risks of IFFs: a substantial extractives sector, poorly governed state-owned enterprises, a large informal sector and financial exclusion are all identified by the OECD (2016a) as risk factors.

Informality and financial exclusion are hallmarks of economies in FCS. One study estimated that in FCS in Africa, up to 90% of the economy is outside of state control (OECD 2018a: 134).Chehade, Tolzmann, and Notta (2021) note that FCS average 8 commercial bank branches per 100,000 adults, while non-fragile countries average 22, which is indicative of how underdeveloped the financial sector is in fragile countries.

A study of illicit trade in West Africa by the OECD (2018a: 110-11) identified high rates of financial exclusion as a driver of criminal economies and IFFs. In such settings, cash transactions and the use of the hawala system predominate and are largely outside the control of regulators. This reportedly increases the risk of money laundering and terrorist financing. Increasing financial inclusion in FCS is complicated by the practice of de-risking, where commercial banks limit their activities in high-risk environments, such as FCS on FATF grey lists. These banks have good reason to do so, but greylisted countries are calculated to experience a resulting 10% decrease in the volume of international payment flows (Collin 2020: 4). The OECD (2018a: 110-11) calls for efforts to widen financial inclusion, including through the use of mobile money systems, to reduce the dependency on hawala and criminal economies, and protect money “from rent-seeking protection payments by all manner of actors”.

Physical

In terms of physical fragility, scholarship has documented how IFFs can amplify insecurity in several ways. First, where illicit outflows stem from the abuse of power by political elites, such as embezzlement and grand corruption, this can generate deep-rooted popular grievances that undermine state authority and legitimacy, and perhaps ultimately spark violent conflict between rival factions (Cobham 2014). Second, where IFFs derive from the profits associated with illegal markets, organised criminal groups may be able to “parlay their IFFs into political power or economic leverage” (OECD 2018a: 109), which in fragile states can led to the criminalisation of governance itself (Cockayne 2010). Third, vulnerabilities in the international financial system can be exploited by violent extremist groups, who rely on illicit financial transactions to conduct their operations (Vittori 2018). Finally, physical insecurity can also provide incentives and opportunities for people in FCS to channel ill-gotten gains to secrecy jurisdictions.

As IFFs hamstring state capacity and erode the social contract, this creates a void of authority and legitimacy. An OECD (2018a) study in West Africa found that into this gap had stepped a variety of state and non-state actors engaged in lucrative criminal activities, including local powerbrokers, organised criminal groups and armed insurgents.

The next sections consider three expressions of how insecurity is exacerbated by IFFs: by facilitating transnational organised crime, by sparking and fuelling civil strife and by enabling international terrorism. Through this discussion, it becomes clear that polities characterised by social fragmentation and propped up by weak, particularistic institutions provide the perfect breeding ground for a multitude of security threats, including violent extremism, insurgency and the proliferation of illegal arms.

IFFs and organised criminal groups

According to the OECD (2018a), organised criminal groups (OCGs) operating in FCS are implicated in three main types of activities: the illicit exploitation of natural resources; the illicit trade in legal goods; and outright criminality, such as extortion and black markets in human beings, weapons, drugs, conflict diamonds, poached ivory, illegally harvested timber and oil (Zdanowicz 2009).

Each of these activities typically involves both inward and outward IFFs, which “help make crime pay” (Vittori 2018: 38). Inward IFFs, such as the for the purchase of opiates, are a major source of income for OCGs and strengthen their ability to evade, co-opt or combat law enforcement agencies (UNCTAD 2020c). OCGs may rely on outbound IFFs to hide the origin and nature of profits stemming from criminality, preventing law enforcement from detecting or seizing these funds (Albisu Ardigo 2014).

While it is possible that the ability of OCGs to channel ill-gotten gains overseas due to vulnerabilities in the international financial system stimulates additional crime in IFF source countries, Collin (2020: 36) notes that further research is needed on this question. There is, nonetheless, broad consensus that IFFs derived from crime heighten insecurity and weaken the state’s enforcement capacity in source countries, which can make future illicit transactions less risky for OCGs (Cockayne 2010).

Cobham (2014) observes that OCGs may incite violent disorder to take advantage of the lucrative opportunities it provides, such as supplying opposing sides with arms and other commodities, or profit from the fact that state security forces are distracted by the conflict and unable to simultaneously pursue OCGs.

IFFs and conflict

There is an established literature on how corruption can ignite and fuel conflict (Chayes 2015; Dix, Hussmann, and Walton 2012; Le Billon 2003; Andvig 2010). Growing attention is also being paid to how illicit finance can spark and sustain violence by providing access to international funds, arms and other contraband. IFFs generate dynamics that play out in harmful ways at the various stages of a conflict.

First, IFFs create material conditions in which conflict is more likely to occur by fostering antagonisms between different groups and eating away at the rule of law. A study by Andvig (2010)found that economic downturns caused by illicit outflows from source countries were prime triggers for conflict. A good example of this is Yemen, which was the fifth largest source of illicit capital from the developing world between 1990 and 2008 (Hill et al. 2013). High illicit outflows from the country contributed to the years of economic stagnation that culminated in the 2011 uprising against the government. Since then, instability and fragility have led to a further increase in capital flight, eroding the country’s tax base and public resources, and creating a vicious cycle of conflict and economic disparity (Midgley et al. 2014; Bak 2023).

Furthermore, in many FCS, high levels of illicit outflows are associated with the consolidation of a rent-seeking clientelist regime, which depends on illicit wealth extraction and the distribution of rents to a variety of actors to maintain power, many of whom stash such ill-gotten gains overseas. As such, high illicit outflows are a feature of the kind of political order, namely state capture, that generates hostility among excluded groups, providing incentives for opposition factions to violently contest state resources and the regime to aggressively persecute opponents to maintain its monopoly on rents (Cobham 2016).

Second, IFFs fuel existing armed struggles by facilitating cross-border smuggling of weapons and other commodities (Dechery and Ralston 2015), thereby prolonging conflict, even where the state is subjected to arms or trade embargos (Schneider 2012). Capital is fundamental to sustaining conflict, and warring parties have an interest in keeping the source of their funding secret (Chigas 2023). IFFs also seem to play an important role in allowing different violent non-state actors to overcome their mutual mistrust and cooperate, to the detriment of the state (Idler 2020).

Commercial actors may be complicit in this. UN ECA (2014: 5) notes that timber companies in Africa have functioned as intermediaries between insurgent groups and financial institutions, facilitating arms trafficking in exchange for lumber. Vittori (2017) points out that anonymous shell companies are used to finance insurgents, criminals and dictators. IFFs may also reduce the effectiveness of security forces, as in Nigeria, where IFFs were “partly linked to the illicit diversion of the funds meant to procure arms to fight Boko Haram insurgency” (Ayodeji 2018: 277).

Third, IFFs undermine peacebuilding and peacekeeping efforts. This is because illicit outflows prevent the development of an inclusive state apparatus able to reconcile and mediate different groups’ (often conflicting) political and material aspirations (Le Billon 2008). Chigas (2023) argues that IFFs create “stakes in continuing violence and the war economies that support or result from it”, pointing to reports that the leaders of Nigerian military involved in the ECOMOG peacekeeping force in Sierra Leone allegedly made so much money from the illicit diamond trade that they sought to perpetuate the conflict.

IFFs and terrorism

The role of IFFs in financing terrorist organisations has been well documented (Midgley et al. 2014). Terrorist groups are known to illegally extract minerals, such as gold or tungsten, and sell them to large multinational companies to finance their activities (Gomez 2012). Similarly, transnational terrorist organisations have often developed extensive multinational networks to finance themselves with the use of secret jurisdictions and offshore banks (Baker and Joly 2008).

Strategic corruption

IFFs may also be exploited by hostile state actors to interfere in an adversary’s political life or even ongoing conflicts. For example, Bak (2021: 4) notes that finance from overseas can be used to “exercise undue or illegal influence over democratic institutions or processes, such as by circumventing restrictions on political donations from foreign sources”.

While much of the conversation around such “strategic corruption” has focused on how geopolitical adversaries of the West use illicit finance to hollow out democratic institutions and interfere with electoral processes in the Global North (Vittori 2018: 42), FCS may also be affected by such tactics. Particularly in polities with poorly regulated financial systems, foreign actors may be able to use illicit financial transactions to fund openly hostile activities with relative ease. This could include the proliferation of dangerous materials ranging from small arms to chemical weapons (Bak 2021: 9). Cohen (2018) gives an example of a UK-registered company that was used to facilitate sanctions-evading arms exports to South Sudan.

AlShehabi (2017) has studied how much of the foreign policy spending by Gulf states is off-budget and unaccounted for, suggesting that actors from the region have used their wealth to expand their influence in FCS in ways that have undermined the national security of these states. According to AlShehabi (2017), Qatar is alleged to have sponsored political parties and armed movements in Afghanistan, Syria, Mali, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya, while Gartenstein-Ross and Zelin (2013) report that some of the funds provided by large charities in the Gulf region to FCS under the guise of humanitarian aid end up in the hands of violent extremists.

How physical insecurity enables IFFs

Insecurity and conflict can serve as a breeding ground for IFFs, providing incentives and opportunities for a multitude of actors to engage in illegal markets, extract wealth in illicit ways and spirit the ill-gotten gains out of the country, often to countries in the Global North where they can shelter and enjoy these funds. The IMF (2022: 7) identifies that an increase in illicit flows is one of the most significant cross-border impacts of fragility and conflict. The OECD (2016a) points to the core dilemma facing FCS: these countries are typically “unable to implement comprehensive measures to combat IFFs, but could face a worsening security situation if they do not address the specific financial flows that support militant groups”.

Spotlight on financial centres

IFFs affect economies in different ways according to whether the proceeds of crime are “laundered domestically or moved abroad, transiting through, or integrated in the economy as a final destination” (IMF 2023a: 10). The majority of this paper has examined the impact of IFFs in FCS, but it is worth noting that IFFs can cause bank liquidity and solvency issues in transit countries, while in international financial centres they can result in “economic capture and distortions, asset price bubbles, and reputational risks, with global spillovers” (IMF 2023a: 8-9).

The OECD (2016a) points out that vulnerability to IFFs may be high for countries that share borders with fragile neighbours or for those en route between source and destination countries for illegal goods like narcotics. Beyond physical proximity, other factors that influence the direction and destination of transnational IFFs include historical, trading, cultural and linguistic connections, as well as the quality of regulatory oversight of financial transactions in transit and destination countries.

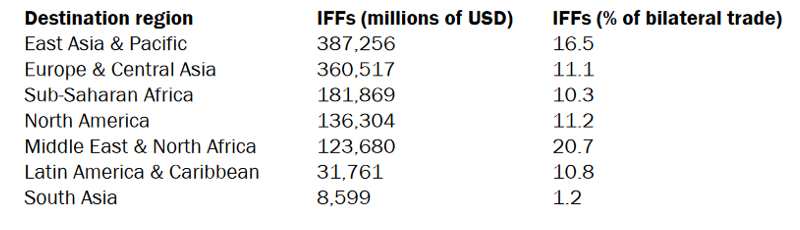

In their study of illicit outflows from Africa, Signé, Sow, and Madden (2020) find that Europe remains a major destination region and that significant illicit funds are also transferred between countries in Africa. Nonetheless, they highlight that emerging economies in Asia and the Middle East are becoming major destinations of ill-gotten wealth from Africa (Figure 11).

Cohen (2018) underscores the complex global picture, noting that illicit outflows from South Sudan have ended up in Ugandan and Kenyan real estate; London was the destination of illicit finance from the Democratic Republic of the Congo, while ill-gotten gains in Afghanistan were transferred to Dubai.

The specific constellation of transit and destination countries may also depend on the nature of the commodity or market. Dubai, for example, seems to play a key role as a destination country for outflows related to the illicit gold (Abderrahmane 2022; Martin and de Balzac 2017), while Uganda seems to function as an important transit country (Global Initiative against Transnational Organised Crime 2021). Dubai’s real estate market has also come under increasing scrutiny in recent years for facilitating the laundering of the proceeds of corruption and crime and sanctions evasion (Kirechu and Vittori 2020; C4ADS 2018; Page 2020).

Figure 11: Illicit financial flows out of Africa, by destination region (1980-2018)

Signé, Sow, and Madden 2020.

- Countries from which wealth is illicitly extracted and moved overseas.

- Occasionally, terrorist financing is added as a discrete category (UNCTAD 2020c), at other times it is included alongside financing of criminal activities, markets and groups (UNCTAD 2023a: 7).

- At the request of the enquirer, this Helpdesk Answer pays specific attention to countries on the World Bank’s list of fragile and conflict-affected situations.

- Hawala is an alternative remittance channel that exists outside traditional banking systems. Transactions between hawala brokers are made without promissory notes because the system is heavily based on trust and the balancing of hawala brokers' books.

- These include efforts to estimate IFFs based on aggregating data on crime to produce a national-level measure of money laundering (Collin 2020: 15). See also the survey of measurement techniques conducted by the UNCTAD-UNODC Statistical Task Force, Conceptual Framework for the Statistical Measurement of Illicit Financial Flows.

- Cobham (2016) does not explicitly mention FCS but talks about “countries characterised by low levels of institutionalisation of authority, a heavy reliance on patronage politics and an accordingly high level of allocation of state rents to unproductive activities (patronage, to maintain the political machine).”

- In FCS, UNCTAD (2020b: 157) notes that a higher proportion of state expenditure is on defence and debt service.