Health sector corruption: A matter of life and death

For decades, donors have worked to strengthen anti-corruption, transparency, and accountability institutions in partner countries, but the development of specific approaches to address corruption in the health sector (and in other public service sectors) is more recent. A first wave of policy and programme guidance for the health sector emerged around 2010, including the original U4 Issue on the topic, Addressing corruption in the health sector: Securing equitable access to health care for everyone.aa97e2f38721 Since then, anti-corruption initiatives specific to health have been pursued around the world. At global level, meanwhile, the Sustainable Development Goals include commitments on universal health coverage and on good governance and transparency. In light of such changes, U4 has updated the original U4 Issue to provide guidance for donors on anti-corruption, transparency, and integrity approaches in health at the international and national levels.

Impact of corruption on health sector performance

Corruption in the health sector can make the difference between living and dying, especially for poor people in developing countries. A 2011 study analysing data from 178 countries estimated that the deaths of approximately 140,000 children per year could be indirectly attributed to corruption. Child mortality correlated more strongly with national corruption levels than with literacy, access to clean water, or even vaccination rates.1eb036cf09a3 In another study, antimicrobial resistance was found to be linked as much to national corruption levels as to antibiotic use.995fa6f1199c And the reduction of AIDS deaths has been significantly slower in countries with higher corruption levels.dc248b271dbd

Corruption in the health sector has severe consequences for access, quality, equity, efficiency, and efficacy of health care services – the five dimensions of health system performance.

Access to health services can be seriously affected by absenteeism of medical staff. Estimated rates range from 19% to 60% in low- and middle-income countries, with more qualified staff like doctors and pharmacists showing higher rates of absenteeism than less qualified staff.c68903ceccd0 Another barrier to access is demands for informal payments or bribes in exchange for services that citizens are entitled to receive for free. The incidence of bribes in direct interactions between citizens and health service providers varies widely, from 1% to 51% at global level, with higher levels in Africa, Central and Eastern Europe, and the Middle East/North Africa, and lower levels in Western Europe and the Americas.abf83b7627dd Theft, embezzlement, and bribery also affect access to needed medicines, equipment, and supplies. For example, in Togo a government audit discovered that a third of the anti-malarial medicines provided by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, worth over US$1 million, had been stolen.251c4fcad6a2

Quality of care and medical drugscan be severely compromised by bribes, kickback schemes, and fraud. Countries such as Tanzania, Uganda, and Ukraine have recognised corruption as one of the major barriers to providing quality health services.da0edbd5b026 Patients may be charged for diagnostics and treatments that are fake or substandard or were not performed at all. Additional problems include kickback-driven referrals and unnecessary procedures. A study by the World Health Organization (WHO) found that worldwide, 6.2 million unnecessary caesarean sections are performed every year, 2 million of them in China alone.49f6a06aa444

Good-quality medicines may be unavailable due to drug theft, stockouts, or extortion. Profiteers use corrupt schemes to avoid government regulation of drugs. Globally, 10% of all drugs are believed to be fake, while in some African countries the figure can amount to 50%.afe4158775ce Counterfeit drugs can lead to severe illness and death, as well as to the spread of drug-resistant viral or bacterial strains within and across countries.

The effect of corruption on equity is a great concern. Families fall into deeper poverty when they are forced to sell assets or go into debt in order to pay bribes for health services that they should have received without charge. Evidence shows that bribes are regressive, imposing a major burden on poorer households. In Peru, the poorest households spent 15% of per capita income on informal payments in general. Economic shock from illness was the most common cause of falling into poverty in Vietnam, affecting 3 million people in 2010.458fbe80a083

Corruption has enormous effects on the efficiency of the health sector, in particular the availability and use of scarce resources. Globally, an estimated 7% of health spending, amounting to more than $500 billion per year, is lost to corruption and fraud.0e3ce2acd3fa Even in Western European countries, the United States, and Canada, the losses are high, estimated at up to 10% of public health expenditure in Germany, 56 billion euros annually in Europe, and $75 billion in the United States for Medicare and Medicaid payments alone. The British Centre for Counter Fraud Studies found that ‘since 2008, losses as a result of corruption have increased by 25% worldwide and even by 37% for the National Health Service in the UK.’8f6f26891d96

Aggregated estimates for developing countries are scarce, but the following examples help illustrate severe efficiency losses. A study of 64 countries found that corruption lowered public spending on education, health, and social protection. In Chad, local regions received only a third of centrally allocated resources; in Cambodia, 5%–10% of the health budget was lost at the central level; in Tanzania, local or district councils diverted up to 41% of centrally disbursed funds; and in Uganda, up to two-thirds of official user fees were pocketed by health staff.d0baddaf0d2a Corruption and lack of transparency also affects drug pricing. In Vietnam, health facilities paid eight times and patients 46 times the international reference price for certain brand-name drugs, and two or 11 times, respectively, for generics; meanwhile, drug costs constitute 50% of the Vietnamese public health budget.394c8a4b5d6f

In terms of efficacy, corruption in the health sector has a corrosive impact on the population’s health, as illustrated by the examples noted earlier. According to the Transparency International (TI) Health Initiative, ‘Multiple studies have found that high levels of corruption are linked to weak health outcomes, and there is strong evidence to suggest that corruption significantly reduces the degree to which additional funding for the sector translates into improved health outcomes.’ In other words, pouring more money into highly corruption-prone health systems will not achieve the intended health goals. More broadly, corruption in the health sector erodes the legitimacy of, and public trust in, government institutions. The same TI report continues, ‘Political stability and efforts to contain epidemics are undermined because citizens encountering corruption at their local clinic lose faith in the state’s willingness and ability to provide basic services.’bd9c88862a9e

Finally, corruption is an obstacle to the long-term goal of achieving universal health care (UHC). The World Health Organization has identified good governance as a ‘critical element’ of efforts to achieve UHC.4c5464fa730f Globally, corruption in the health sector is estimated to cost more money than what would be required to achieve UHC. As noted above, an estimated $500 billion per year in public health spending is lost to corruption. In order to achieve UHC, an additional $370 billion per year would be needed until 2030, with international development funding required to cover $17–$35 billion.6150756f4f4e By this logic, the funds lost to corruption in the health sector globally could essentially fill the implementation gap for UHC.

The health sector’s vulnerability to corruption

A number of factors make health systems particularly susceptible to corruption. They include the vast quantities of resources flowing through these systems; the high level of uncertainty; asymmetry of information; the large number of actors; the complexity and fragmentation of national health systems; and the globalised nature of the supply chain for drugs and medical devices. These factors, explained briefly below, hinder transparency and accountability and create systematic opportunities for corruption, regulatory capture, and undue market pressure.

Resources spent in the health sector globally and at country level offer lucrative opportunities for abuse and illicit gain. As noted above, annual global spending on health is estimated to exceed $7.5 trillion in 2016.06dd5588a3f5 Health spending ranges from around 4% of gross domestic product in low-income countries to more than 15% in countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), with a rising trend.ae45967da333

Uncertainty regarding the effectiveness of medical treatments and the inability to predict who will fall ill, when, and with what kind of illness makes health markets distinct from others, leading to inefficiencies and scope for abuse. The poor functioning of health markets makes it difficult to set standards for accountability and to discipline health care providers for poor performance. Consumer choice is not a good regulator: particularly in developing countries, patients often cannot shop around for the best care, given distance, public service delivery monopolies, and limited availability or high cost of private care.

Similarly, the health sector is characterised by a high degree of information asymmetry. Information is not equally available to all actors. This makes it difficult to fully monitor the actions of different actors, hold them accountable, detect abuses, and assign responsibility. Patients lack information to judge medical decisions made on their behalf or to assess the correctness of a bill, and the discretion given to providers puts patients in a weak position if providers choose to abuse their position. Even insurance auditors may have a hard time evaluating whether a bill is correct and the services provided were necessary. Asymmetry of information also affects decisions related to procurement of medicines and medical devices. Pharmaceutical company representatives know more about their products than do the doctors who prescribe them, and regulators are hard pressed to ensure the quality of drugs and medical equipment. Policy and regulatory issues related to benefit packages, drug prices, and market access of new health technologies, among others, are also affected.

The large number of dispersed actors involved in health systems exacerbates these difficulties. The relationships between medical suppliers, health care providers, health service payers, and policy makers are often opaque, making it difficult to detect conflicts of interest that can lead to policy distortions. Health service delivery is often decentralised, making it difficult to standardise and monitor service provision and procurement.

National health systems are complex and often fragmented, with different sub-systems attending to the health needs of different populations. For example, there may be sub-systems for public sector employees, for workers in the formal economy with labour contracts, for the military and/or police, and for the informal sector and/or the poor. Most countries’ systems involve a combination of public and private health care providers (with the latter often far less regulated than the former), and there may also be a combination of public and private health insurers. The multiple logics of these sub-systems and the different legitimate and illegitimate interests of the various actors provide opportunities for corruption and for regulatory and policy capture.

Finally, the global nature of the supply chain for drugs and medical devices allows for undue market pressure, information manipulation, regulatory capture, and abuse. This relates to the globalised nature of the pharmaceutical and health care product industries, their enormous size, and the inherent conflict between their legitimate business goals and the medical needs of the public.

Because these various factors create vulnerability to abuse, health care is among the most heavily regulated sectors in most countries. However, powerful interest groups frequently try to capture the regulators and influence their decisions through a variety of strategies, including undue influence, bribes, and complex kickback schemes.

Identifying and punishing corrupt practices in health remains difficult. The lines between inefficiency or unintentional misconduct, on one hand, and unethical behaviour, intentional abuse, and criminal behaviour on the other can be blurred, and abuses may be hidden behind apparent inefficiencies. Also, the imperative to save lives at all costs may impede frank discussions among government actors and development partners about corruption in the health sector. But experiences from around the world have shown that it is possible to begin a dialogue about these problems and develop strategies to address them (see Annex 1).

Understanding corruption in the health sector

The term ‘corruption’ means different things to different people, and there is no universally accepted definition. Transparency International defines corruption as ‘the abuse of entrusted power for private gain.’d6573c388b74 Those with entrusted power include public sector officials (whether appointed or elected) as well as officials and staff of private companies, international organisations, and civil society organisations.587a3d3516d8

The principal international treaty on corruption, the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC), does not define corruption as such. Rather, it enumerates specific acts of corruption, including bribery and embezzlement, influence trading, abuse of function, illicit enrichment, money laundering, concealment, and obstruction of justice. However, jurisdictions differ in terms of which practices are or are not criminalised. One of the starting points for addressing corruption in any country is to know how it is defined in the country’s own constitution and laws.

How does corruption manifest itself in the sector?

The various types of corruption find many manifestations in national health systems. Different health systems are prone to different types of corruption, and the risks for abuse depend in part on how funds are mobilised, managed, and paid.

Integrated systems are ones where the public sector finances and directly provides health care, as is common in developing countries. They tend to be particularly vulnerable to large-scale diversion of funds at the ministerial level, as well as in financial flows from the national to the subnational levels. Bribes and kickback schemes in procurement, illegally charging fees to patients, diverting patients to private practice, and absenteeism are also common. Finance-provider systems separate public financing from health service provision, and are more common in middle-income countries. They tend to be particularly vulnerable to fraud in billing government and insurance agencies. They can also suffer from excessive or low-quality medical treatment, depending on the payment mechanism, as well as regulatory capture and conflicts of interest. State and policy capture, and corruption in the drug supply chain, procurement, and appointments, can occur in both types of system.4a0a85792702

Case studies of health sub-systems for the poor in Colombia and Peru provide an illustration of how corruption can take different forms across different health systems (Box 1).

Box 1: Corruption in the Colombian and Peruvian health sub-systems for the poor

In 2011, the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) commissioned a study to explore the main vulnerabilities to corruption in the national health sub-systems of Latin America that provide services to the poor.* The results from Colombia and Peru present interesting insights.

First, there are basic structural differences between the two systems. Colombia’s subsidised health insurance system for the poor separates payments from providers and features regulated competition among a mix of public and private health insurers and providers. The Peruvian sub-system serving the poor is managed by the Ministry of Health and relies on direct, public provision of health services by public staff.

The Colombian system is highly decentralised in its authority, functions, and financing, the result of a major health reform started in the 1980s. By contrast, the Peruvian system remains substantially more centralised. Furthermore, Colombia has a progressive financing insurance structure, while Peru still depends heavily on out-of-pocket payments by users, the most regressive form of health care financing.

The study found that in Colombia, the main vulnerabilities related to fraud and corruption in claims processing and beneficiary affiliation. These are areas of vulnerability that do not exist in integrated public provision systems. Decentralisation of the subsidised system, in particular in the administration of funds, seemed to imply a decentralisation of corruption risks. At the same time, decentralisation allowed Colombia to achieve high health insurance coverage. Finally, vulnerability to policy and regulatory capture clearly affected the whole system in Colombia, including the regulatory and supervisory bodies themselves.

Peru, meanwhile, showed notable vulnerabilities in the area of human resources. Key problems included provider absenteeism; redirecting of patients to private practice instead of treating them for free; and the ‘buying’ of jobs and promotions. The management of drugs and supplies, as well as asset management in health establishments, also surfaced as particularly subject to abuses in Peru but not in Colombia. In addition, stewardship by the Peruvian Ministry of Health was perceived as weak, especially with respect to its controls on spending.

In both countries, procurement of drugs and medical supplies continued to be susceptible to corruption and undue influence despite reform efforts. Political interference in the nomination of hospital directors, which is supposed to be based on merit, was pervasive, with serious consequences for hospital performance. And in both countries, corruption was perceived to be higher in the other health sub-systems that serve the richer part of the population and people with formal employment, perhaps in part because they involve larger flows of resources.

Several insights can be gleaned from the Colombia-Peru comparison. First, the emergence of corruption scandals should not lead to hasty conclusions that one system is more prone to corruption than another. They simply have different dynamics and loci that attract corrupt activity. Second, decentralisation is not a ‘silver bullet’ for increased transparency and accountability. But there is no evidence, either, that centralised systems are necessarily less corrupt. Third, laws, norms, regulatory processes, and health sector oversight agencies are valuable targets for capture, but little attention has been paid to these issues. And fourth, an integral strategy of internal and external controls, with strong stewardship by the national health authorities, is essential but often lacking.

* Hussmann (2011b).

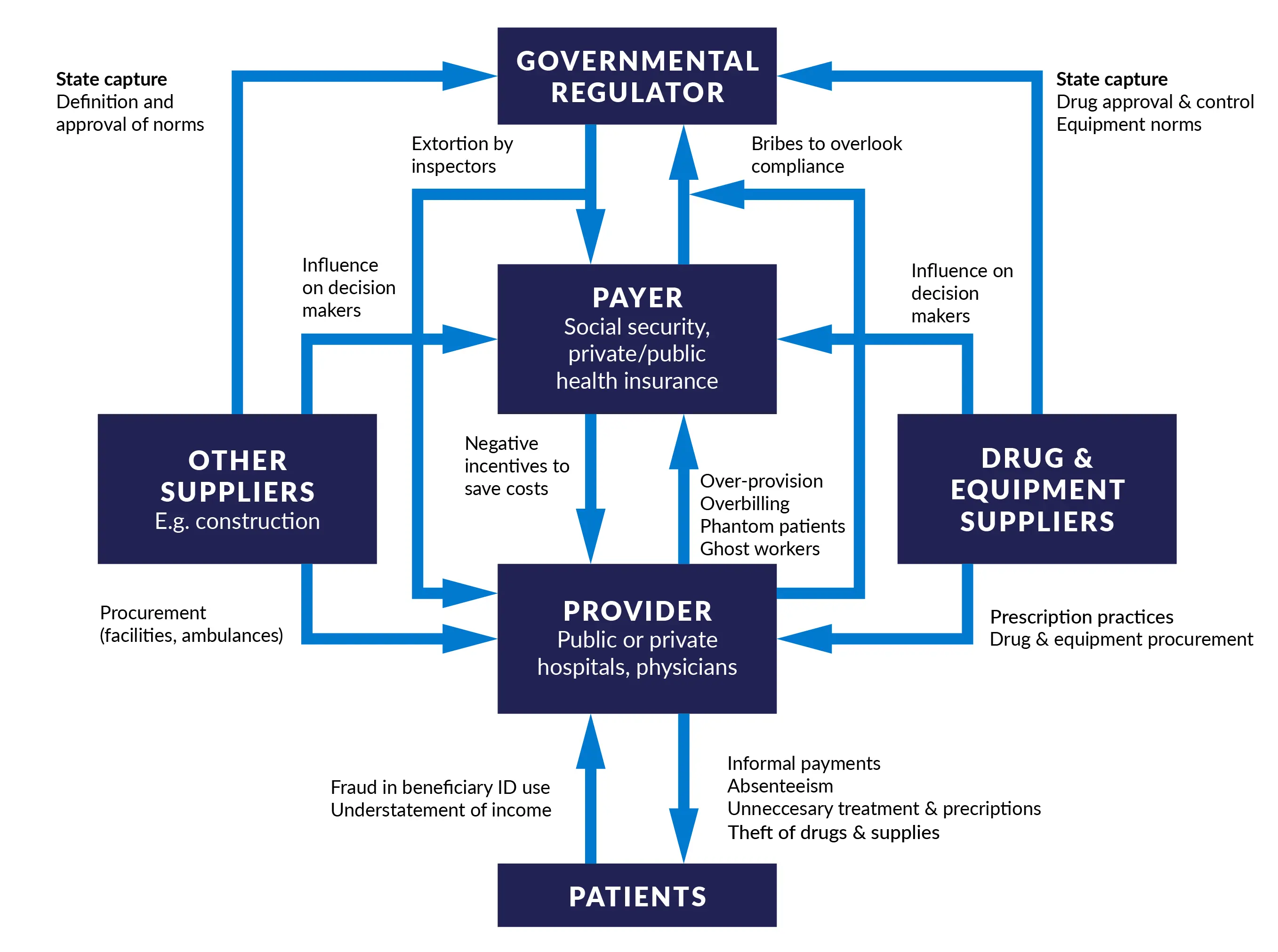

To assess the vulnerabilities in a given health system or sub-system, one can start by examining the roles and relationships among different players and understanding the ‘rules of the game.’ The players can be classified into five broad categories:

- Government regulators (parliaments, health ministries, and specialised health regulation, oversight, or public health agencies)

- Payers (public social security institutions, private insurers, government health funds)

- Providers (public and private hospitals, doctors, pharmacists, NGOs, faith-based organisations)7c3616f0eef2

- Consumers (patients)

- Suppliers (medical equipment, pharmaceuticals, construction, ambulances)

Figure 1 illustrates typical corruption risks arising from relationships between these main actors. Most publicly available research on these risks and possible mitigation strategies focuses on the service delivery level, that is, on interactions between providers and users, as well as on the pharmaceutical and health product supply chain. The risks of policy, regulatory, and institutional capture, and of corrupt interactions between payers and providers, tend to be under-researched, even though they have great impact on overall health system performance.

Figure 1: Examples of corrupt practices among different health sector players

Source: Adapted from Savedoff and Hussmann (2006).

Corruption used to be framed mainly as misconduct or criminal behaviour by individuals. However, in countries with systemic and deeply rooted corruption, corrupt practices may be used by different groups of legal and sometimes illegal actors for illegal objectives. For example, the buying and selling of positions in hospital administration may be part of a clientelistic political party system. Health providers may be fake companies set up for money laundering and other illicit purposes; cartels of doctors or other health professionals may capture specific high-cost treatments to extract rents from health systems; hospital inputs and other equipment may be stolen by small local cartels; and pharmaceutical companies may capture groups of patients or patient organisations for illicit purposes. When designing mitigation strategies, it is important to understand the dynamics of and incentives for individual and group behaviour in order to identify potential allies and opponents of change.

Social, political, and cultural differences in what is considered acceptable or unacceptable behaviour require context-specific understanding. Certain types of conduct universally constitute criminal behaviour or administrative misdemeanour, such as bribes or kickback schemes in procurement, buying and selling of positions, or intentional overbilling. But lines are often blurred. At the service delivery level, informal payments that are seen as socially acceptable gifts and favours in one context may be regarded as unacceptable bribery in another.

It should be recognised that not all forms of unethical behaviour are illegal. While most people might agree that it is wrong for a public physician to have an ownership stake in private medical ancillary services, some countries tightly regulate this conflict of interest while others do not. At the same time, not all practices that are illegal are necessarily seen as illegitimate. Some countries have prohibited certain promotional incentives by the pharmaceutical industry to medical staff, yet there may be fairly broad social acceptance of such practices.

In sum, context matters. An understanding of how corruption manifests itself in a particular national health system, along with an assessment of its prevalence and impact on system performance and health outcomes, is a crucial precondition for the design of mitigation strategies. (Table 2 below provides an overview of key corruption risks in the main health system functions, as well as potential mitigation strategies.)

What are the main tools used to diagnose corruption in health?

An array of tools and initiatives have become available for diagnosis of corruption in the health sector. These help define the problem and generate buy-in for anti-corruption measures; they also help practitioners and policy makers agree on goals and targets and monitor improvement (or deterioration) over time. Some assessment tools focus specifically on experiences or perceptions of corruption and on sectoral risks, while others look more broadly at how the health sector is governed. Some focus on specific areas or sub-sectors within health, such as drugs or human resources. Also, some general international surveys of corruption include assessments of the health sector. Table 1 gives an overview of the main tools available.

However, most of the commonly used tools do not assess high-level corruption in the health sector, that is, at the level of ministers, other high-ranking health authorities at national and subnational levels, or hospital managers. This gap, both in practice and in the literature, needs to be addressed if corruption in health systems is to be tackled seriously and strategically.

Table 1: Selection of tools to identify and measure corruption risks and corruption in the health sector

|

Area |

Issue |

Tool |

|

Corruption perceptions and experiences |

Perceptions of corruption |

|

|

Experiences of corruption |

|

|

|

General |

Sector-wide and cross-cutting issues |

|

|

Pharmaceuticals |

Drug and health product supply chains |

|

|

Individual providers |

Job purchasing |

|

|

Health worker absenteeism |

|

|

|

Informal payments |

Informal payments |

|

|

Budget and resource management |

Budget processes |

|

|

Payroll leakages |

|

|

|

In-kind leakages |

|

Source: Adapted and expanded from Lewis and Pettersson (2009).

How is corruption diagnosed in the health sector in practice?

Given that the forms and dynamics of corruption are highly context-specific, and considering that available assessments of corruption perceptions, experiences, and risks tend to be focused on the country as a whole, the corruption assessment methodology is a crucial element of the design of anti-corruption initiatives in the health sector.

Comprehensive corruption assessments on the initiative of the health sector authorities

Generally speaking, a comprehensive corruption assessment of the health sector provides a good basis for identification of strategic priority areas for action. Such an assessment covers perceptions and experiences; corruption risks and their causes, incentives, and consequences; as well as the tolerance levels of different actors towards corruption (see Box 2 for an example of this approach). In some cases further analysis might be needed: for example, if the administration of public hospitals is one of the priority risk areas, it may be necessary to conduct additional analysis on this topic. Corruption risks and practice often vary between different regions of a country as well as between different types of hospitals or private clinics performing public functions.

Box 2: Corruption risks and tolerance in Colombia’s health sector

In Colombia, a comprehensive assessment of health sector corruption and sector integrity strategies was conducted in 2017 under the auspices of the vice minister of health and the director of the superintendency of health. It analysed perceptions, experiences, and risks of corruption; areas of particular opacity; and levels of tolerance of corruption by internal and external stakeholders. The assessment received technical and financial support from an anti-corruption project funded by the European Union (EU), and was carried out by a national university with solid prior experience in the field of health sector governance.

The assessment was conducted in three phases, using complementary diagnostic tools. First, a series of macro-processes related to public health, health insurance, and service delivery were described in detail, identifying relevant norms, actors and their interactions, and resource flows. Through focus group discussions and key informant interviews, the main risk areas for corruption and opacity were identified within each of the macro-processes in order to select priorities for detailed diagnosis.

In the second phase, priority processes (contracting, service delivery, billing, payments and claims processing, as well as collective interventions for public health) were analysed in depth through a perception and experience survey of system users and an institutional survey of service providers and payers. These surveys were complemented by interviews with health sector staff in a selection of cities. In addition, a national survey was conducted on levels of tolerance to corruption in the health sector.

The third phase consisted of developing, through a participatory process, recommendations for concrete mitigating measures, strategies, and policies directed at the different actors (ministry of health and superintendency, public hospitals, insurers, and provincial health departments).

The assessment process ensured ownership by the lead health institutions through a carefully designed process of regular interaction with the vice minister, the superintendent, and lead officials, validating the methodology and seeking feedback on results in the different phases. At the same time, independence was maintained with respect to the final diagnosis and recommendations in order to ensure trust in the legitimacy of the process and outcome. The assessment was accompanied by a communication and awareness-raising strategy. This included academic seminars; 10 information bulletins on the different steps and partial results; and the presentation and discussion of results with the minister, vice ministers, superintendent, and relevant staff, as well as with professional and health industry associations.

Some important lessons were learned. First, this broad and deep process generated a solid diagnosis of the phenomenon of corruption in the Colombian health sector. The results were concerning and something of a surprise, as irregularities and corrupt practices were found to be even more widespread and systemic than initially thought. The process also made it possible to identify concrete action measures targeted at the different players and aimed at transformative change. Second, leadership at the highest level of the health authorities was crucial in ensuring the support of lower-level directors. Third, the role of the university was crucial as well. It provided an interdisciplinary team composed of several university departments as well as students from different disciplines, involved in continuous research on health sector governance, thus going beyond the role of mere consultant. And finally, the role of the EU-funded project in providing ongoing technical advice and political support was considered invaluable by all involved.

Source: Proyecto Anticorrupción y Transparencia de la Unión Europeo para Colombia (ACTUE 2018).

However, such broad assessments are rare. More common are narrowly tailored corruption studies intended to inform the design of mitigation measures aimed at specific risk areas, such as drug supply, or particular types of misconduct, such as informal payments. The following sections briefly describe several diagnostic approaches.

Health sector–specific diagnosis initiated by anti-corruption bodies

Despite recently increasing attention to corruption in national health systems, sector-wide assessments still tend to be driven by the national anti-corruption authority rather than by the ministry of health. This may be because anti-corruption authorities have an institutional mandate to promote integrity across government, based on international guidance in the anti-corruption field, and such initiatives are aligned with their performance measures. Ministries of health, on the other hand, have few incentives to pursue sector-wide approaches, as these require complex political and operational management and are not clearly aligned with sector goals. The Moroccan case in Box 3 illustrates this tension and provides lessons for sector diagnostics.

Box 3: Lessons from the Moroccan anti-corruption strategy for the health sector

The Moroccan Central Authority for Corruption Prevention (ICPC) opted for a sector approach, identifying the health sector as a priority. The ICPC commissioned a private consulting firm to develop a health sector integrity strategy focused at service delivery level. First, public policies, laws, and regulations for corruption prevention were reviewed. Second, corruption risks and experiences were identified in all service and administrative areas of public health institutions. Data were collected in five regions, 3,500 patients were interviewed, and 87 staff members of public hospitals participated in interviews and focus group discussions. This made it possible to define several typologies of corruption. Within these, a total of 87 corruption risks were identified for key players, including hospitals, health centres, clinics, regional centres for blood transfusion, private laboratories, and the central administration of the ministry. Third, the consultancy developed an action plan aimed at mitigating the risks.

The ICPC delivered the results and recommendations for action in 2011 to the Ministry of Health, but ownership of the process by the health authorities seems to have been weak. This resulted in slow initial implementation, among other effects. According to a 2019 interview with one of the ICPC leaders of the process,* the overall approach to the sector strategy was later reviewed with key sector players, and implementation of actions had improved. An analysis of the results achieved in terms of health goals and outcomes would be useful.

Some lessons learned from this experience are as follows: (a) officials at the highest level of key health sector institutions need to assume ownership of the process, ideally at the diagnostic stage; (b) the process needs to be clearly communicated by the top leadership of the health sector to lower-level officials; (c) pilot projects can boost implementation of the overall strategy; and (d) the anti-corruption authority needs to have the explicit backing of the president if leverage over a powerful line ministry is to be achieved.

* The interview was conducted at a meeting convened by WHO, UNDP, and the Global Fund in February 2019 in Geneva to create a Global Network on Anti-Corruption, Transparency and Accountability in Health (GNACTA).

Source: Hussmann and Fink (2013).

For sector-wide assessments in particular, national oversight and accountability institutions can help identify areas vulnerable to corruption and track progress. These include:

- Office of the auditor general (supreme audit institution): annual audit reports and specific investigations provide insights into vulnerable areas and help pinpoint where leakages occur.

- Anti-corruption commission, inspector general’s office, or ethics office: close cooperation in investigating specific allegations and regular analysis of complaints about alleged corrupt or unethical behaviour can help identify risk areas.

- Parliament: regular interaction with the parliamentary complaints commission and parliamentary accounts committee may provide information about specific risk areas.

In seeking their collaboration, however, attention should be paid to the risks of political influence and patronage that often permeate these institutions in countries with systemic corruption.

Pharmaceutical and medical device sub-systems

Assessments in the pharmaceutical and medical devices sub-system have become more common since around 2005. The most widely applied and referenced methodologies are the Good Governance for Medicines (GGM) instrument and the Medicines Transparency Alliance (MeTA) approach (Box 4). The GGM is mainly government-led, with strong support from WHO, and has been applied in some 30 countries. MeTA is a multi-stakeholder initiative between government, civil society, and the private sector, with support from development partners, and has been piloted in at least seven countries.

Box 4: GGM and MeTA in a nutshell

The World Health Organization has developed within the framework of its Good Governance for Medicines (GGM) programme an assessment instrument to identify corruption risks in the pharmaceutical sector. It is based on a diagnostic tool developed in 2002 for the World Bank’s work in the Costa Rica. According to UNDP (2011), it can ‘potentially examine up to eight core functions: medicines registration, licensing and inspection of pharmaceutical establishments, promotion, clinical trials, selection, procurement, and distribution. The end result is a baseline to monitor the country’s progress over time in terms of governance in the pharmaceutical sector (e.g., level of accountability, transparency in the various processes in the pharmaceutical sector).’ The GGM in its original form is particularly useful for integrated public health systems.

The Medicines Transparency Alliance (MeTA) is a multi-stakeholder alliance, initially led by the UK Department for International Development (DFID) and supported by the World Bank and WHO. ‘It examines issues related to drug prices, quality, availability, promotion, transparency and accountability, and multi-stakeholder relationships… MeTA uses a large arsenal of diagnostic tools to gather information. Such tools may include a pharmaceutical sector scan; review of data availability about price, registration and policies on promotion; and a stakeholder mapping. Priority information sought includes the quality and registration status of medicines, availability of medicines; price of medicines; and policies, practices and data on the promotion of medicines. Also investigated is the specific policy context as well as how supply chain operations work, affordability of medicines, access and their rational use.’

Source: UNDP (2011); see also WHO (2018b).

Intuitional-level diagnostics

Another approach to corruption risk assessment focuses on the institutional level. While all health sector institutions are vulnerable to corruption, corruption risk assessments are more often conducted in provider agencies – health centres, hospitals, clinics – and less often in national health regulatory agencies, public health insurers, or provincial health departments, not to mention ministries of health. As these non-provider institutions are also key players in the health system, their assessment would be a useful area of focus for development partners. In low-income countries, institutional corruption risk or accountability assessments are often part of donor-supported programmes. Middle-income countries are more likely to have national norms that require all public sector institutions to conduct such assessments on a regular basis. However, given that such public sector norms are often implemented in a non-participatory, ‘tick-the-box’ way, there is room for donor-supported technical assistance, as illustrated in Box 5.

Box 5: Turning an anti-corruption assessment from a compliance issue into a management tool: The case of Invima in Colombia

The Colombian drug and food authority is the Instituto Nacional de Vigilancia de Medicamentos y Alimentos, known as Invima. It set out to integrate transparency and integrity as a cross-cutting commitment into its institutional mission under new leadership in 2016.

A first step was to turn a legal instrument called the Plan Anticorrupción y Atención al Ciudadano (Anti-corruption and Citizen Service Plan) into a planning instrument that could be used instead of following the traditional ‘tick-the-box’ exercise to comply with a statutory obligation. Under the leadership of the director, focus group discussions allowed staff to break taboos and talk about corruption within the institution. This allowed the officials to identify corruption risks and develop mitigating measures, including an institutional policy of ‘zero tolerance to corruption.’

A second aspect was to approach ‘accountability’ as a permanent two-way dialogue with users and interest groups, including the different industry sectors regulated and overseen by Invima. Yearly public accountability sessions were preceded by consultations to identify perceived strengths and weaknesses (and areas of opacity) of the processes that Invima is in charge of. The entity was recognised for the innovation and openness of its accountability strategy by certain industry representatives, as well as by the Administrative Department of Public Service (Departamento Administrativo de la Función Pública).

A third initiative was the creation of an ‘integrated management system of transparency and integrity.’ The purpose was to place transparency, integrity, and corruption prevention norms for the public sector at the heart of Invima’s mission, going beyond mere compliance with formal obligations. The director entrusted the implementation of this initiative to a ‘seed group’ of managerial staff from different units in order to overcome existing silos and create staff ownership and empowerment. Assisted by external experts, this group identified priority areas for action, building on the results of the corruption risk analysis and combining prevention with detection and sanctions. An internal and external communication strategy linked all efforts with the commitment of Invima leadership to promote cultural change within the organisation. In addition, Invima implemented a pilot project to train its public officials to identify and respond to ethical dilemmas and corrupt practices. Finally, the entity developed a competition that invited all work units and teams across the institution to submit creative performance pieces spotlighting the institution’s values, including transparency, integrity, and honesty.

For the design and implementation of these initiatives, Invima received technical assistance and modest financial support from an EU-funded anti-corruption project that included a focus on sector integrity strategies.

Some key lessons learned are as follows: (a) leadership of the director and support of the management team were essential in promoting institutional cultural change in favour of transparency, integrity, and accountability; (b) the support of national-level entities such as the Administrative Department of Public Service and the Secretariat of Transparency increased the legitimacy of the initiatives; (c) the internal seed group at managerial level, bringing together the areas of planning, internal control, human resources, and communication, proved crucial for the articulation of the different actions; and (d) the ongoing and flexible support of the international cooperation project was essential for the design and successful implementation of the initiatives.

Source: ACTUE, Estrategia de transparencia en el INVIMA.

Assessment of specific corrupt practices in the health sector

Yet another approach is to conduct assessments of specific corrupt and unethical practices when these have been identified as particularly harmful for health service delivery. Examples include informal payments, absenteeism, and corruption in drug procurement. Based on the available literature, these practices have been analysed in a large number of specific country cases. However, the applied assessment tools seem to vary considerably in the definitions and approaches used, given the great context specificity of these practices.d9e313ffcdfd

Combination of perception-based and experience-based assessments

Ideally, corruption perception assessment tools should be complemented by corruption experience assessment tools. The application of such tools in different settings suggests that there may be considerable discrepancies between their respective results in the health sector (Box 6). In addition, it is useful and sometimes essential to use different experience-based tools for health service users and the general public, on the one hand, and health sector employees or experts, on the other (the latter category includes personnel in medical care, human resources and financial administration, management, logistics, etc.). Triangulating the results from these two types of assessments can help establish a realistic diagnosis of system integrity.

Box 6: Contrasting results from perception-based and experience-based corruption diagnosis tools

In 2013 the Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer (GCB) asked more than 114,000 respondents in 107 countries about their experiences and perceptions of corruption. Perceptions of corruption in the health sector tended to be far higher than reported experiences of bribe paying. In Nigeria, for example, 41% of respondents considered the health sector to be corrupt, but only 9% reported having paid a bribe. In Indonesia this ratio was 47% to 12%. There may be multiple reasons for this gap, but it is clear that people who have had not personally experienced corruption nonetheless may consider parts of or the whole health system to be corrupt, perhaps due to scandals in the media, hearsay, or inefficiencies they have experienced.

Colombia, meanwhile, provides interesting insights into the need to distinguish even between different types of experience. According to the GCB 2013, 62% of Colombian respondents considered the health sector as corrupt, but only 7% reported a personal experience with bribe paying. This led policy makers and experts to believe that corruption levels in Colombia were highly overestimated. However, an in-depth sector corruption assessment by civil society organisations in 2017 found that 55% of the respondents considered the health sector as corrupt, and 53% had witnessed corruption during the past two years. One of the main differences in the 2017 Colombian study was that people were asked about their experience not only with bribes, but also with other forms of corruption like favouritism, influence trafficking, conflicts of interest, and fraud. Experience with bribery stood at 12%, very close to the results of the GCB. This suggests that it is important to conduct in-depth national analysis of perceptions and experiences with a range of common corrupt practices.

Sources: Transparency International Global Corruption Barometer 2013; GES and ACTUE Colombia (2018).

The review of how corruption diagnosis is carried out in practice shows that in many cases a combination of different tools will be useful. This is not an argument for duplication of efforts, but for deciding on an appropriate combination of tools for each context and purpose.

And finally, two important points for development partners. First, donor funding and technical support is essential for health sector corruption assessments. Even in middle-income countries, where the highest level of government may be vested in health sector anti-corruption assessments, it may be impossible to fund the assessments through the cumbersome national budget processes.

Second, promising initial results emerge from three-actor alliances between (a) high-level authorities of health sector institutions, which give strategic direction for assessments that respond to their needs and priorities; (b) development partners, which provide funding as well as technical assistance; and (c) national universities, which conduct the corruption assessments with multi-disciplinary teams involving large numbers of students. Political will at the highest level is an indispensable precondition, albeit not frequently found. At the same time, the involvement of universities helps ensure continuity when public leaders change.

Design of mitigation strategies

Corruption is a public health issue that will not disappear by itself, nor can it be ignored. Donor agencies, international organisations, and national governments have come to explicitly acknowledge the problem. The experience of mitigation strategies in the health sector as well as lessons learned from other sectors will help health advisors of donor agencies, their government counterparts in-country, and other actors recognise that it is possible to confront corruption. Towards that end, this section briefly outlines key elements to be taken into consideration when designing mitigation strategies.

Understanding the enablers and drivers of corruption

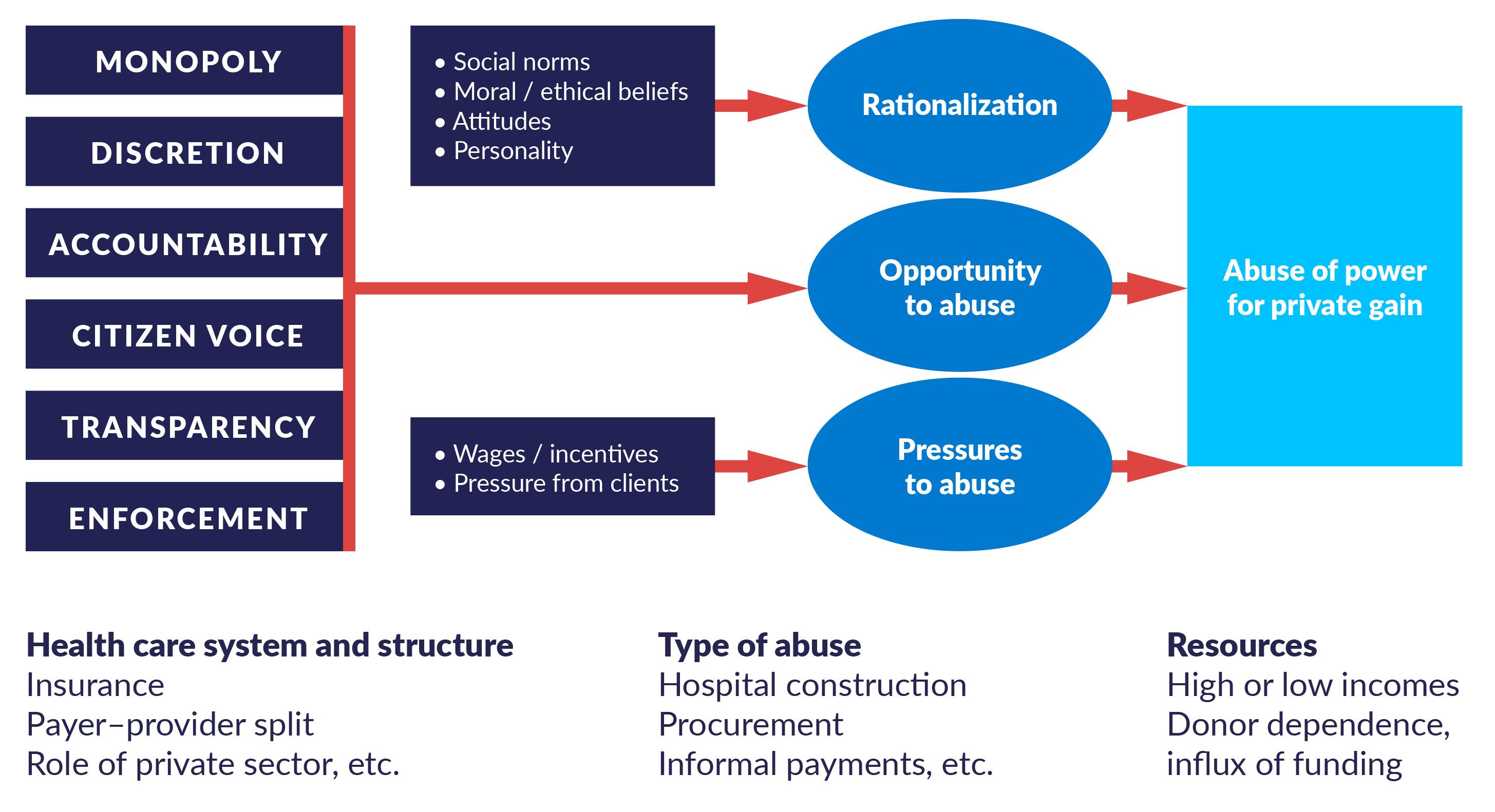

A first step is to understand the circumstances that are conducive to corruption. Figure 2 presents a conceptual framework that can be summarised as follows: People are more likely to cross the line between honest and corrupt behaviour when they have an opportunity to misuse their power (in part because the probability of consequences is low); when they feel pressured or incentivised to do so; and when personal or social beliefs and norms allow them to rationalise corrupt behaviour.

Figure 2: Key elements for the design of mitigation strategies

Source: Vian (2008).

Looking more closely at the elements of opportunity included in Figure 2, we see that corrupt behaviour is more likely in situations where some or all of the following conditions are present:

- The agent with entrusted authority has monopoly powers. The agent might be the only provider of health services, medical treatment, or medicines and supplies.

- Officials have discretion without adequate control of their decision-making authority. Such decisions might concern the definition of treatments and drugs to be covered by health insurance, or the prescription of particular medicines, diagnostic tests, or treatments. Discretion is a complex issue due to the tension between control and medical autonomy.

- There is not enough accountability for decisions and actions. Accountability comes through measurement of results and sanctions for non-performance.

- Citizen voice and participation are insufficient to allow for social control – for example, by generating experience-based data on absenteeism, monitoring drug procurement or hospital construction, or exposing undue influence in regulatory and policy decisions.

- Transparency is lacking, in the form of active disclosure of and access to information. This affects, for example, the regulation of market access of drugs and medical devices, the prices of medicines, or prescription behaviour.

- Enforcement is weak. Abuse or corruption is not detected and punishedthrough administrative, fiscal, or penal enforcement or through social sanctions.

Pressures and incentives to engage in corruption can be political, financial, bureaucratic, or social. For example, public officials may feel an obligation to return political favours to superiors, the party, or suppliers. They may feel pressured financially because of low public sector wages. Public officials also may feel social pressure, for example to favour relatives in awarding contracts or filling positions.

Individual beliefs, attitudes, and social value systems influence the likelihood of corruption by allowing those engaged in corrupt practices to rationalise or justify their behaviour. In post-communist Europe and Central Asia, for example, the introduction of capitalism came with the notion that ‘everything has its price.’ In some African societies – indeed, in a range of societies around the world – corruption may be justified by the social imperatives of gift giving, family or ethnic solidarity, or redistributive accumulation.

Key elements of mitigation strategies

An understanding of the circumstances favouring corruption provides a basis for the design of mitigation strategies. The medical and governance fields share a fundamental principle: prevention is better than cure. In line with this, efforts to tackle corruption need to translate the main principles of good governance – information, transparency, integrity, accountability, and participation – into action. High-level political will and leadership is essential.

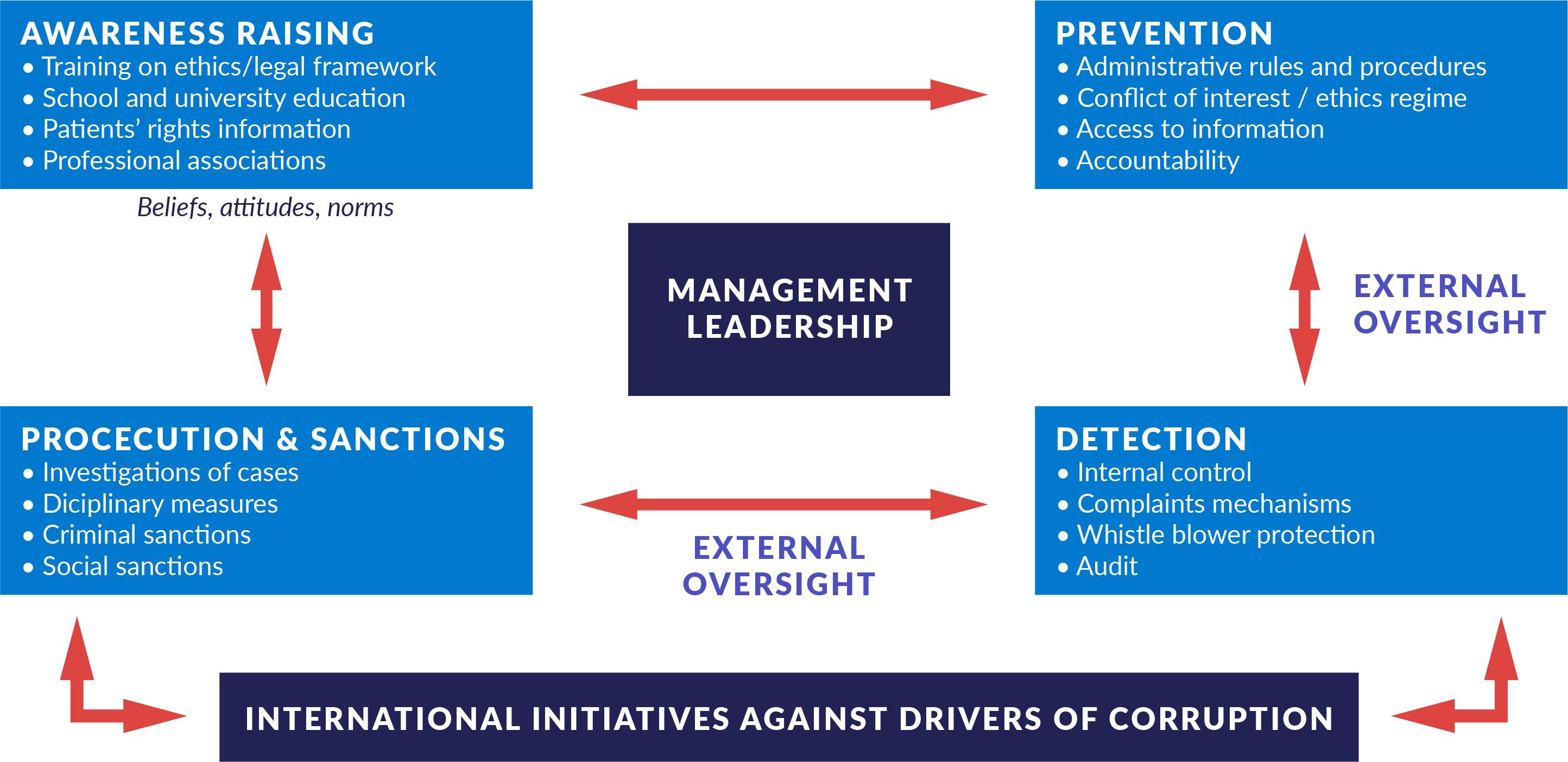

Efforts to address corruption risks should contain a combination of legal, institutional, and management measures. The linkages between prevention and enforcement require special attention. Of particular relevance, as reflected in Figure 3, are sound management systems and practices that reflect the principles of transparency, accountability, and participation in external oversight. In addition, credible control systems and enforceable sanctions, including audits, internal and external complaints-handling mechanisms,20181fed9ecb and whistle-blower protection, are needed to catch misconduct that could not be prevented. However, in countries with weak rule of law, expectations about the effectiveness of detection and deterrence need to be realistic.

A key challenge is to ensure the appropriate mix and sequencing of these approaches. No single measure alone will bring about real change. For example, active disclosure and free access to information (transparency) about drug-prescribing behaviours needs to be linked to monitoring of the desired result, whether this is to lower costs, reduce unnecessary treatments, or ensure that generic drugs are used where applicable. Monitoring in turn should be linked to reporting of the results (accountability). Finally, detection of improper practice could be facilitated through information systems that feed into the respective oversight institutions (enforcement). In other words, the different elements are mutually reinforcing and need to be combined for transformative change.

Figure 3: Interplay of awareness, prevention, detection, and sanctions in corruption mitigation strategies

Source: Author.

Corruption prevention and control requires authentic political commitment, high-level leadership, sufficient knowledge of the health sector, and resources to implement the chosen strategies and interventions.25ea4f7391f7 This may sound obvious, but these elements are often lacking in practice due to the political cycles of governments, the programme cycles of development projects, or a combination of both. While political leadership at the highest levels is usually essential to address the most pernicious forms of corruption in the health sector, the lack of such leadership should not be used to justify inaction on the part of donor agencies. Rather, donors should proactively and strategically look for areas, entry points, and/or partners that can promote even incremental change in corruption control while focusing on improving health outcomes.

Finally, the design of anti-corruption interventions should also look at levers that can have an impact on grand corruption in the health sector – for example, national officials channelling large amounts of money from the health budget to bank accounts abroad or to the purchase of property and luxury goods. The undue influence of the international pharmaceutical industry on national drug policy, a form of state capture, also falls in the category of grand corruption. Mitigation measures could include monitoring of the assets, interests, and lifestyles of senior health sector officials as well as scrutiny of their acquisitions and movement of assets, both in-country and internationally. On the development partner side, a whole-of-government approach to corruption in the health sector might be useful.

How has corruption been addressed in the health sector so far?

Corruption in the health sector is increasingly recognised by national governments and civil society in countries around the world; by different health-related industries, in particular the pharmaceutical and medical device industry; as well as by development partners and international organisations. The past decade has seen:

- A growing body of literature on corruption in the health care sector. Since the year 2000, the number of articles has more than doubled.65eb64fa4342

- A growing volume of sector and sub-sector policy, programme, and diagnostic guidance produced by donors and international organisations, including U4, UNDP, WHO, OECD, the World Bank, and DFID, among others.

- The crafting of specific national programmes or strategies to address corruption in the health sector, often supported by development partners.

- The implementation of practice-oriented research initiatives conducted by universities and think tanks from the Global North in partnership with local actors in the Global South, again mostly supported by international development funding.

- Initial steps to create a Global Network on Anti-corruption, Transparency and Accountability in Health, convened jointly by WHO, UNDP and the Global Fund in early 2019.

Countries around the world have made efforts to address corruption and unethical behaviour in health systems. In many if not most cases, the initiatives seem to be targeted at either specific problems (such as informal payments, absenteeism, or overbilling), specific processes (such as drug procurement or health workforce management), or specific institutions (such as health centres, hospitals, and maternity homes). These interventions are often deployed in limited geographic areas, and for limited periods of time. Moreover, the initiatives often seem to be developed in an opportunistic and not necessarily strategic way. Opportunities or imperatives for action may arise, for example, when donor funds become available to support anti-corruption projects in the health sector, or to mainstream a corruption risk approach into health sector programmes; when a government needs to respond to a publicised corruption scandal; or when civil society advocacy pushes the government into action. More holistic, strategic, and medium- to long-term initiatives to address corruption in health systems seem to be rare as yet.

To date, there is little documented evidence on what works and what does not, under what conditions, and with what kinds of results.8093b4e2029d The available literature mainly provides context-specific case studies on issues such as absenteeism, informal payments, theft and embezzlement of drugs and supplies, unnecessary or false procedures, and fraudulent reimbursement claims. There is also a fairly significant body of literature on how to address corruption in the pharmaceutical supply chain. A number of shared methodologies for this have been developed at international level and implemented at country level, with a review of results again from the international perspective.

It should be noted, though, that these considerations derive mainly from literature that is internationally available, mostly in English; a considerable part of it was developed with donor support, either through commissioned or funded research or through project reviews and evaluations. This may result in a distorted picture of the situation. There has been a growing demand for more research and critically documented evidence generated by practitioners and academia.

Table 2 outlines the main types of corruption in the health sector and lists some selected mitigation strategies. For further information on these forms of corruption and mitigation strategies, see Annex 1.

Table 2: Mitigation strategies for different types of corruption risks in health systems

|

Area |

Issue or process |

Type of corruption |

Selected mitigation strategies |

|

Regulation |

Health policy |

|

|

|

Health care financing |

|

||

|

Quality of products, services, facilities, and professionals |

|

||

|

Budget and resource management |

Budget process |

|

|

|

Billing for services |

|

|

|

|

Payroll management |

|

|

|

|

User fee revenue |

|

|

|

|

Use of resources |

|

|

|

|

Procurement |

Construction and rehabilitation of health facilities |

|

|

|

Equipment and supplies |

|

||

|

Drug management |

Approval |

|

|

|

Procurement |

|

||

|

Distribution |

|

||

|

Human resources management |

Appointments and promotions |

|

|

|

Accreditation of health professionals |

|

|

|

|

Time management |

|

|

|

|

Education and training |

|

|

|

|

Service delivery |

Service delivery at facility level |

|

|

Source: Author, with inputs from Vian (2008).

In a number of countries, anti-corruption, transparency, or accountability strategies have been developed for the health sector as a whole. The distinct feature here is that the whole sector was scanned for corruption risks, and on the basis of the results, priority areas for action were selected. This selection does not necessarily address all forms of corruption detected, or even the most harmful forms, as this may be politically or technically infeasible in the short term. Rather, priority might be given to corruption in service delivery, for example, as the area that citizens tend to care most about. However, if well-known forms of high-level corruption are not addressed, the credibility and legitimacy of the strategy might suffer (as was the case in the initial phase of the Moroccan health sector anti-corruption strategy described in Box 3).

In many cases such broad-based sector strategies seem to be supported, and sometimes promoted, by development partners. In cases where the main country counterpart is not the ministry of health but the national anti-corruption agency, special effort is required to achieve full buy-in at ministerial level. Unfortunately, documentation is scarce on the implementation and results of health sector strategies, and on lessons learned – without doubt an important area for comparative research.

A number of international initiatives have been created for the pharmaceutical sub-sector. The Good Governance for Medicines programme and the Medicines Transparency Alliance provide risk assessment methodologies and action plans that have been implemented over several years in the participating countries. Box 7 summarises some lessons learned.

Box 7: Results and lessons learned from MeTA and GGM

A study on MeTA from 2017 found: ‘Countries used evidence gathering, open meetings, and proactive information dissemination to increase transparency. MeTA fostered policy dialogue to bring together the many government, civil society and private company stakeholders concerned with access issues, and provided them with information to understand barriers to access at policy, organisational, and community levels. We found strong evidence that transparency was enhanced. Some evidence suggests that MeTA efforts contributed to new policies and civil society capacity strengthening although the impact on government accountability is not clear.’ The study highlights the importance of involving civil society in monitoring and advocacy for accountability efforts. It further underlines the need for sustained efforts if transparency is to increase accountability of government and other actors in the pharmaceutical sector.

Reviews on the GGM programme found that it increased awareness of transparency and governance in the pharmaceutical sector and contributed to the publication of previously unavailable information. However, it is not clear whether and to what extent corruption may have been controlled. GGM’s effort to actively promote leadership by the ministries of health was noted as important, although the vulnerability to changes in government and to lack of support or involvement from other relevant sub-sector actors, including ministries of finance, was also underlined. In this programme, too, the inclusion of civil society and the private sector was considered relevant.

Sources: Vian et al. (2017); Kohler and Ovtcharenko 2013.

Two global initiatives that aim to promote transparency, accountability, and civil society participation broadly at the state or government level have helped facilitate anti-corruption approaches in the health sector. The Open Government Partnership (OGP) is a multi-stakeholder initiative with close to 80 participating countries. By 2019, a quarter of the members had implemented commitments related to the health sector, including public monitoring of performance, budget and expenditure tracking, policies to address conflicts of interest, and social accountability in health. The OGP notes that ‘health commitments are often more ambitious than commitments in other sectors, but are less successful in significantly improving government openness.’ It calls on participating governments to ‘put citizens in the center of health policy development.’287ee5d234ad An initiative dealing specifically with procurement, the Open Contracting Partnership, works with governments, businesses, civil society organisations, academia, and the media to open up government procurement and address problems such as corruption and lack of transparency. Focusing on the health sector is a potential approach to be pursued.

Corruption in health procurement can lead not only to great financial losses but to drug shortages, inflated prices, and counterfeit medicines. Accordingly, a new initiative was started following the Anti-Corruption Summit in London in 2016, where a number of countries including Argentina, Malta, Mexico, and Nigeria pledged to introduce open contracting into their health sectors. Also, with funding from DFID, the Transparency International Health Initiative is working on a project called Open Contracting for Health (OC4H), with an initial focus on five countries in Asia and Africa.

Specific risk areas of the health sector have recently received attention in terms of policy guidance. The issue of transparency in drug pricing has become an important point on health policy agendas, both national and international. In many countries the cost of medicines accounts for a large proportion of health spending. Moreover, drug prices vary greatly between countries, with some poorer countries paying 10 times the reference price of the same drug in Europe or North America. Efforts to regulate drug prices can generate results, but one of the main challenges is the opacity of drug markets and regulations. Against this backdrop, the World Health Assembly in 2019 approved a milestone resolution on ‘improving the transparency of markets for medicines, vaccines, and other health products.’201e96ce5a68

Clinical trials have been identified as vulnerable to opacity, with severe consequences for the health sector. According to Transparency International UK, ‘This lack of transparency in clinical trials can increase the risk for undue influence, manipulation of data and evidence distortion. It is a symptom of limited regulatory authority over the reporting process. It opens the door to fraud and corruption and undermines both medical advances and public health objectives.’ With civil society partners, TI has developed a practical guide for policy makers on how to foster transparency in this area.9f6158ecaed7

Several countries have experimented with using social accountability measures to curb health sector corruption. A recent study of a programme focusing on maternal health in the Indian state of Uttar Pradesh found that informing women of their rights and teaching them how to lodge complaints yielded substantial results. The initiative reduced bribe taking and informal payments for health services that should have been provided free of charge.0933b2a933ef

Similarly, a 2009 randomised controlled trial and 2012 follow-up research in Uganda revealed that social accountability interventions improved both health service delivery and health outcomes. The interventions facilitated monitoring-oriented citizen engagement with health facility personnel and provided information for citizens about the facilities’ operations. The interventions led to a reduction in mortality of 33% for children under five years old, as well as a 15% reduction in medicines going missing from the facilities and a 13% reduction in staff absenteeism. The 2012 follow-up, which sought to determine the long-term effects of the initial intervention, found that there was still a 23% reduction in under-five child mortality and 27% for children under two, as well as a 12% reduction in medicines going missing.a2818c5065ff

A similar study looked at the impact of community scorecards on reproductive health outcomes in Malawi. Compared to control areas, areas using the scorecards showed significantly greater proportions of women receiving a home visit during pregnancy and a postnatal visit, as well as higher levels of service satisfaction. The scorecards apparently helped facilitate relationships between community members, health service providers, and local government officials by building mutual accountability and promoting locally relevant and feasible solutions to problems.deabba7d6815

Weaving health and governance commitments together: Universal health coverage and the Sustainable Development Goals

As part of the international development agenda, all UN Member States have committed to achieve universal health coverage as part of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) by 2030. According to the World Health Organization, at least half of the world’s population still does not have full coverage of essential services, and around 100 million people are being pushed into extreme poverty because they have to pay for health care.c5a0d7627a7c

According to WHO, universal health coverage means that ‘all individuals and communities receive the health services they need without suffering financial hardship. It includes the full spectrum of essential, quality health services.’db746d07e1cc In addition to improving people’s health, attaining UHC is also expected to help achieve other health-related SDG targets such as those on health outcomes (e.g., mortality, infectious diseases), as well as SDG goals on education and poverty.

Making progress towards UHC requires health system strengthening at country level, as well as efforts to address a number of international health issues such as the pharmaceutical value chain and drug pricing. Critical elements include robust financing structures and the pooling of funds (health insurance); a health workforce with good capacity; good governance of the health sector; sound systems for procurement and supply of medicines and health technologies; and well-functioning health information systems.

All of these elements for the achievement of UHC, however, can be vulnerable to different types of corruption, opacity, and unethical behaviour. In many developing countries corruption affects not only frontline service delivery for UHC, but also the provision and management of the required funding and appropriate regulation. In this sense, corruption should be widely recognised as a severe threat to UHC.

While recognising that each country is unique and can choose its own focus areas for measuring progress towards UHC, WHO also calls for a global approach that allows for comparisons between countries. It suggests that measurement should focus on (a) the proportion of a population that can access essential quality health services, and (b) the proportion of the population that spends a large percentage of their household income on health. Both of these indicators can and should be linked to an approach that assesses the extent to which corruption influences the results.

Three of the Sustainable Development Goals contain commitments relevant to addressing health sector corruption. They include SDG 3, ‘Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages’; SDG 16, ‘Build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels,’ which includes fighting corruption; and SDG 17, ‘Revitalize the global partnership for sustainable development.’

In each of these SDGs, specific targets and indicators are particularly relevant to health sector corruption. In SDG 3, the most relevant targets are 3.8, achieve universal health coverage, including financial protection and access to quality care; 3.c, increase health financing and retention of the health workforce; and 3.d, strengthen the capacity of countries to manage health risks.

In SDG 16, the most relevant are targets 16.4, reduce illicit financial flows and return stolen assets; 16.5, substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms; 16.6, develop effective, accountable, and transparent institutions; 16.7, ensure responsive, inclusive, and participatory decision-making; and 16.10, ensure public access to information.

For SDG 17, relevant targets include 17.9, enhance international support for targeted capacity building; 17.14, enhance policy coherence for sustainable development; 17.16, enhance multi-stakeholder partnerships to achieve the SDGs; and 17.17, promote public, public-private, and civil society partnerships.

A recent study provides concrete proposals on how these three SDGs could be woven together in order to address corruption in health systems.bece5014fecc The study first presents examples of how different types corruption affect the SDG 3 targets and indicators, and then suggests how SDG 16 and SDG 17 targets and indicators could be applied in relation to health sector corruption (see Table 3).

Table 3: Non-health SDGs with potential application to health sector corruption

|

SDG goal and target |

SDG indicators |

Implications for health sector corruption |

|

16.5: Substantially reduce corruption and bribery in all their forms |

16.5.1 and 16.5.2: Proportion of persons or businesses who had at least one contact with a public official and who paid a bribe or were asked to bribe during the previous 12 months |

Could be used to measure how many people have paid a bribe in the public health sector |

|

16.6: Develop effective, accountable and transparent institutions at all levels |

16.6.1: Primary government expenditures as a proportion of original approved budget, by sector 16.6.2: Proportion of the population satisfied with their last experience of public services |

Could be used to measure misallocation of health sector funds |

|

17.14: Enhance policy coherence for sustainable development |

17.14.1: Number of countries with mechanisms in place to enhance policy coherence of sustainable development |

Need to establish policy coherence around international and regional laws, regulations, and enforcement against health-related corruption |

|

17.16: Enhance the global partnership for sustainable development, complemented by multi-stakeholder partnerships that mobilise and share knowledge, expertise, technology and financial resources, to support the achievement of the SDGs in all countries, in particular developing countries |

17.16.1: Number of countries reporting progress in multi-stakeholder development effectiveness monitoring frameworks that support the achievement of the SDGs |

Need to establish multi-stakeholder partnerships that monitor progress towards these goals specifically in the health sector |

Source: Mackey, Vian, and Kohler (2018).

The authors of the study suggest that the UN’s Inter-agency and Expert Group on SDG Indicators should work with WHO on creating a multi-stakeholder partnership to strengthen coherence in programming and policies relevant to addressing the ‘disease of corruption.’

Reflections on the approaches pursued so far

Given that corruption is an important barrier to health access and has a serious impact on health outcomes (see section 1), the framing of anti-corruption and transparency approaches needs to be more clearly linked with health outcomes and with the policy goals of the health sector. Reducing corruption and promoting good governance should not be seen as ends in themselves, but as a means to achieve sector goals. Such an approach could generate support from different actors in the system even for unpopular measures. Most importantly, it could be politically attractive to the senior health leadership, as their performance would be assessed in view of health sector outcomes and not in terms of curbing corruption per se.

There has been considerable progress in diagnosing and understanding corruption in the health sector, as well as in the design of methodologies for this purpose. Although each country context requires its own specific analysis, the available literature and policy guidance (on systems or sub-systems, as well as on specific phenomena like absenteeism, informal payments, drug procurement, or clinical trials) allows interested actors to build a sufficiently strong narrative to promote specific anti-corruption initiatives in a given country. Also, the available diagnostic tools provide a pool of references to draw from in designing a purpose-tailored set of instruments (see Box 2 for an example).

However, there is often a significant gap between the identification of problems, the strategic design of interventions to address problems, and the implementation of these measures. The tools used are often normative and prescriptive, focusing on rules and procedures that are assumed to prevent corrupt practices, but these tools may not adequately capture the complex dynamics that lead to a specific corrupt behaviour. Also, there is a tendency to underestimate the financial and especially the human resources that will be needed over time to implement, monitor, adapt where necessary, evaluate, and communicate the results of the measures undertaken.

The design and implementation tend to be documented in context-specific cases studies, often focused on corrupt practices at the service delivery level. Given that there is no one-size-fits-all approach, there is a need for forums in which experts and other stakeholders can exchange experiences and best practices. Towards this end, steps should be taken to strengthen existing knowledge hubs and centres of excellence and develop new ones.

Documented evidence on outcomes of the initiatives is patchy at the best, and even less is known about impact.27d152b5baca Sometimes evaluations or studies are conducted on particular tools and their effectiveness in improving health sector governance, but without making a clear link to processes or outcomes in the health sector. High-quality studies, comparative where possible, are needed to assess the effects of anti-corruption strategies, with a special focus on their links to health sector goals and outcomes.