Addressing corruption from the bottom-up: citizens as critical agents of change

There is widespread agreement that corruption cannot be effectively controlled without civil society involvement.79772d465578 This suggests that social accountability, understood as those formal or informal mechanisms through which citizens engage to bring state officials or service providers to account,cfd2f60e2e5d holds significant potential to counter corruption. This is especially the case in the delivery of public services, where corruption generates high social costs for service users. Social accountability empowers citizens with adequate information and institutional mechanisms to denounce and resist abuses of power, opening up opportunities for grassroots actions against corruption.

Reviews of social accountability interventions have shown mixed results.c88cfaf8e365 Nonetheless, the empirical evidence suggests that social accountability initiatives can make a meaningful contribution if they adequately involve anti-corruption practices that the intended audience can understand and apply.f31aaa6068b2

Social accountability: not a “one-size-fits-all” approach

Corruption hampers the provision of essential public services und severely undermines development outcomes. However, bribery, favouritism and other corrupt behaviours are disturbingly common at the point of service delivery in many developing countries. This can often be due to local state authorities’ weak monitoring and law enforcement capabilities. In such contexts, eliciting citizen participation is a promising way to assess public service quality, and monitor and denounce corrupt practices. Recognising the potential of citizen participation in countering corruption, development partners and international organisations have been prolific in developing a significant number of social accountability tools.

Box 1

Social accountability tools – common examples

Citizen charters

Citizen charters inform citizens about their rights and entitlements as service users, including the standards they can expect (timeframe and quality), the remedies available for providers’ nonadherence to standards, and the procedures, costs, and charges of a service.

Social audits

Publicly held social audits are monitoring processes through which organisational or project-related information is collected, analysed, and shared publicly in a participatory fashion.

Community scorecards

A community scorecard is a monitoring tool that assesses services, projects, and government performance by analysing qualitative data obtained through focus group discussions with the community.

Citizen report cards

A citizen reportcard is an assessment of public services by the users (citizens) through client feedback surveys.

Participatory budgeting

Participatory budgeting refers to a process through which citizens participate directly in budget formulation, decision-making, and monitoring of budget execution (World Bank 2018).

For more information see: UNDP’s guidance note on fostering social accountability: From principle to practice (2010)

Ensuring success, however, requires identifying which approach better fits local needs and community expectations. Therefore, eliciting, articulating and communicating citizen voice is a process that does not take place in a vacuum. Service users do not simply await to be empowered with the right information to become governance advocates. Rather, it is the practitioners’ responsibility to conduct sufficient background research to better understand the local conditions that shape the incentives, beliefs and expectations of citizens, which in turn affect their attitudes towards corrupt behaviours.

The discussion of social accountability initiatives in this U4 Brief draws from varied experience gathered in Mexico, the Philippines, Serbia and Tanzania.

Citizen voice – a central component of social accountability

Arguing that contextualisation is pivotal to programme design, this section discusses a general model of social accountability and its constituent elements.

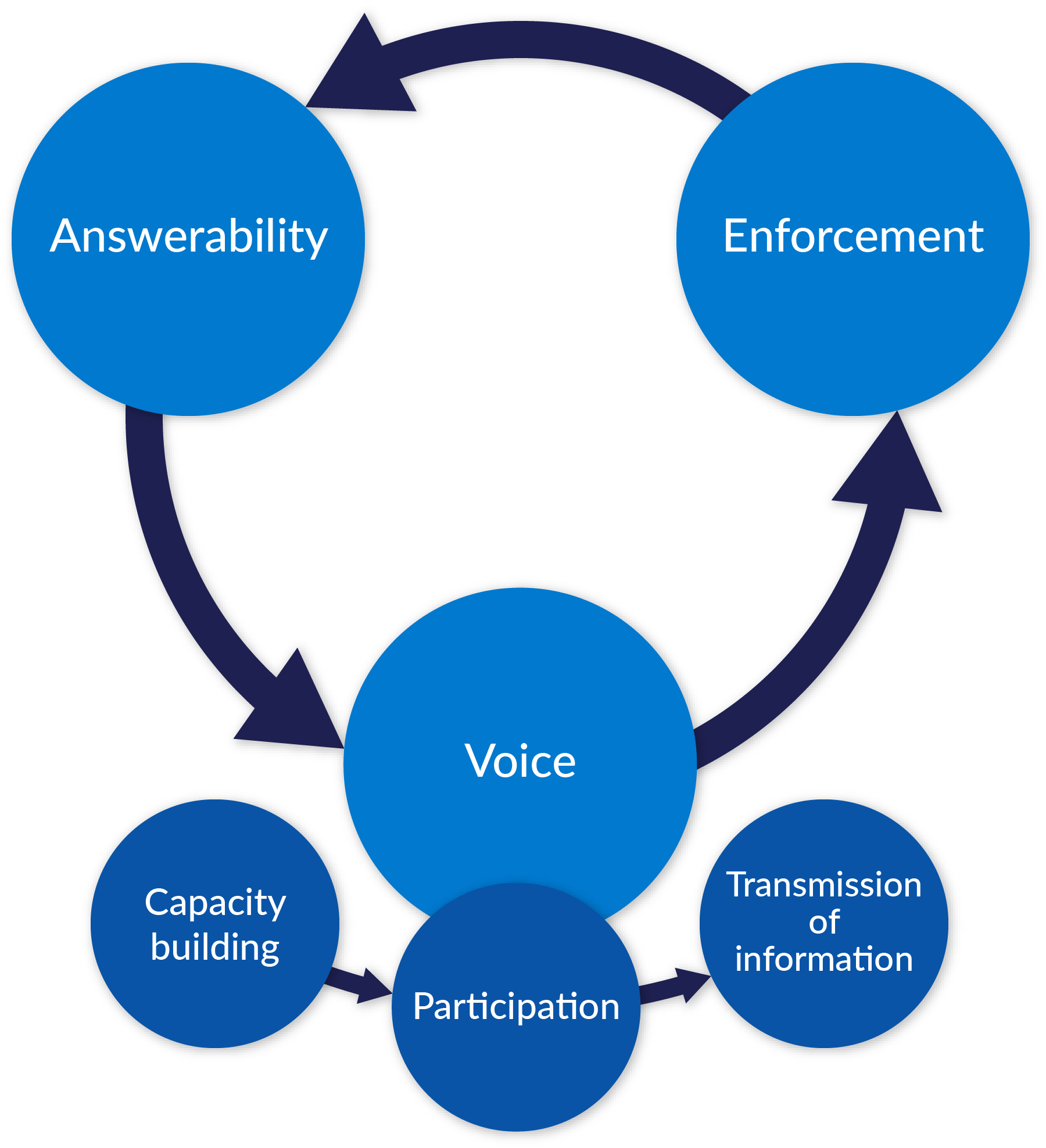

At its core, social accountability involves generating and articulating citizens’ voice to elicit enforcement of sanctions when public service provision fails, and to promote answerability of public authorities. Therefore, effective social accountability is made up of three building blocks – voice, enforceability and answerability – which together form a cycle.

This framework for contextualisation focuses on the steps necessary for articulating citizens’ voice. Citizen voice can be a variety of mechanisms – formal and informal – through which people express their preferences, opinions and views, and demand accountability from power holders.7d92d671d8e7 Voice can be understood as a process of citizen engagement involving capacity building, participation and transmission of critical information (see figure 1).fbc35be67c17 All three subcomponents of voice offer different modalities for programme implementation, which are highly context-sensitive.

Figure 1: Elements involved in excercising social accountability.

Source: Adapted from (Baez-Camargo and Jacobs 2011)

Capacity building

Citizens need a minimum understanding of their rights and entitlements in order to evaluate public service performance. Capacity building to ensure citizens have this information is therefore essential in social accountability initiatives.

Participation

Citizens may be invited to participate in a variety of activities aimed at steering public sector performance towards better outcomes. Participation may involve, for example, evaluating service provision quality, identifying and denouncing instances of corruption, or engaging in policy-making processes.

Transmission of information

Inputs resulting from participatory activities need to be aggregated and articulated in order to be conveyed to decision-makers. This is a crucial component of social accountability: It represents the stage in which social accountability outputs are expected to enter the public sphere and trigger institutional responses, such as sanctions and political answerability.

Identifying important local context features

Different social accountability instruments give different levels of prominence to capacity building, participation and transmission of information. Depending on which social accountability approach practitioners use, they need to confront distinct theory of change assumptions and align them with local realities. To understand these local realities, there are three features of the local context that are particularly important:

1. Collective action potential in the communities

Practitioners should pay attention to community attributes such as:

- Horizontal social networks

- Levels of participation in voluntary associations

- Communitarian or individualistic patterns for problem-solving

- Importance of social norms such as solidarity, reciprocity and gift-giving.

These elements are relevant because they point to the prevalence of intangible resources, such as social capital, which are conducive to collective action.088e5940a978

Assessing collective action capabilities is critical for choosing the right participatory approach. This is because some social accountability modalities require particularly strong and well-coordinated citizen actions. For example, social audits or community score cards – activities geared at monitoring and evaluating service delivery – require collective and coordinated mobilisation of citizens.

Collectively generated citizen inputs generally deliver detailed and comprehensive information. This helps to promote citizen empowerment given that social capital and trust increases when individuals work together. Indeed, evidence indicates that where community members know and trust each other, the impact of citizen-led monitoring is much higher (see box 2).

Other social accountability schemes involve individual inputs – for example citizen report cards and more traditional whistle-blower and complaints management mechanisms. Where collective action capabilities are low, suitable inputs include individual reporting through convenient, easy to access means – eg SMS or online surveys.

Box 2

Philippines – achieving a proactive attitude against corruption

Evidence from a social accountability monitoring programme in the Philippines that focused on the delivery of agricultural subsidies showed that citizen participatory inputs can greatly increase accountability of local government in contexts where community ties are strong. Informal social networks were instrumental in disseminating the programme’s activities, and helped strengthen links between the community and local government authorities. Because citizens discussed monitoring findings and outcomes in village assemblies and informally, even farmers who did not take part in monitoring developed a more proactive attitude. They forwarded issues or concerns to the local government as they became better informed about public services available to them (Baez Camargo 2016).

2. Predominant citizen attitudes and expectations towards public service providers

Enhanced citizen agency is an outcome indicative of success in promoting social accountability. However, the ability to exercise agency may be compromised by particular political, historical or cultural experiences that influence people’s attitudes and behaviours towards the state and public authorities. When tailoring capacity building and participatory activities it is useful to understanding these attitudes towards duty bearers.

Research and literature reviews reveal that attitudes of service users vary widely. Citizens are sometimes ignorant of their rights and may feel vulnerable and disempowered vis-à-vis service providers. They are easy victims of bribery, extortion and other power abuses. In other cases, service users proactively engage in gift-giving and bribery to obtain a privileged treatment or because they see it as the only way to access services. Feelings of disempowerment or even fear of reprisals on the part of citizens may be associated with a sense of futility and helplessness vis-à-vis the perceived impunity of corrupt individuals.

Different scenarios call for different capacity building approaches. Training and awareness raising about rights and entitlements can sometimes enable citizens to identify corruption and be aware of available counter measures. Other situations call for capacity building around behaviours such as gift-giving: Although these may be socially accepted and expected, they are not appropriate for interactions with public officials. Similarly, raising awareness about convictions and successful examples of anti-corruption law enforcement can address beliefs that corruption and impunity is inevitable.c334735b699a In cases where citizens feel intimidated by public officials, raising awareness about means to expose corruption while protecting denouncer’s identity is essential in social accountability capacity building.

Box 3

Tanzania – success in confronting corrupt health workers

A study of a local social accountability initiative in the health sector in Dar es Salaam revealed that lack of information about rights and entitlements caused resignation to bad service quality and a sense of impotence vis-à-vis staff in public health facilities. Capacity building activities consequently focused on helping users identify abuse of power by health facility workers. Trainees learned to successfully confront corrupt individuals, who often stopped in their tracks since they were used to the acquiescence of users. Social accountability participants reported feeling empowered and became reputable in their communities as resource persons advised and helped others (Baez-Camargo and Sambaiga 2015).

3. Working with trusted institutions and actors

Maximising the potential impact and sustainability of social accountability initiatives also requires identifying and working with actors and institutions that the community regards as trustworthy. In social accountability initiatives, such actors may serve as intermediaries or focal points in support of citizens’ anti-corruption activities – especially for relaying information to state actors and giving feedback to the communities.

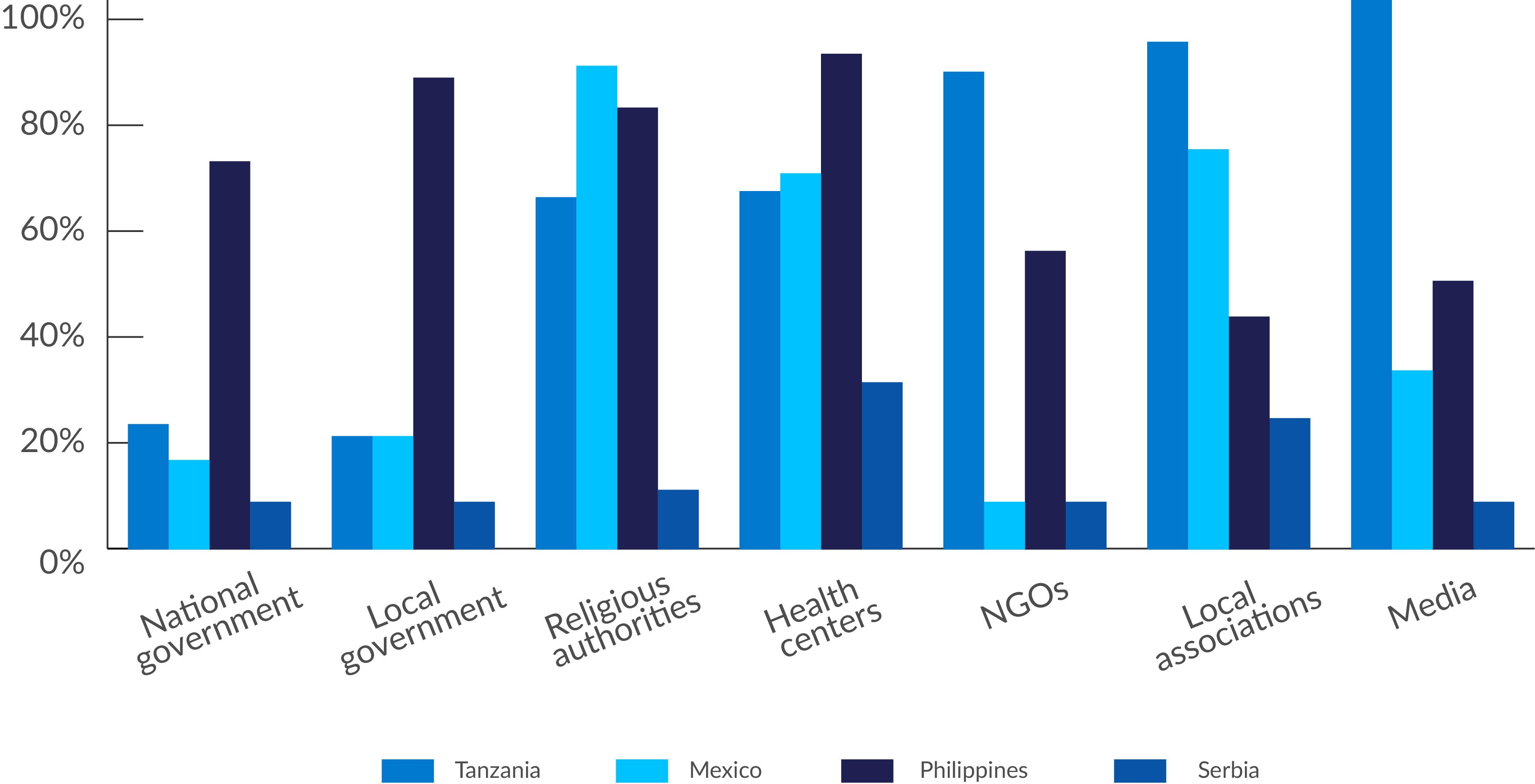

Figure 2 illustrates the variation in institutional trust across the four countries. As the survey results make clear, each context necessitates a different approach.

Figure 2: Context matters: trust in institutions

Source: Baez-Camargo (2015)

These findings illustrate the need to formally incorporate traditional community decision-making institutions into the formal complaints management mechanisms associated with essential public services, for example:

- In Tanzania, media and NGOs provided essential support in exposing cases of corruption in health facilities that participants of a social accountability initiative uncovered.

- High trust in local government institutions in the Philippines signalled the feasibility of strategies of direct constructive engagement between citizens and local authorities.

- In Mexico, high trust in local associations reflected the community assemblies’ central role in rural areas.

- In Serbia, low institutional trust across the board illustrate why contextualisation is essential to social accountability (see box 4).

Box 4

Serbia – impersonal approach to social accountability

A Serbian health sector study showed the challenges with bottom-up anti-corruption strategies where low levels of institutional trust mirror prevailing circumstances such as weak social capital and civil society, and health service users who fear repercussions for denouncing corruption. The situation was compounded by a lack of adequate communication about diagnosis and treatment options, contributing to patients’ feelings of confusion. Under such conditions, the analysis suggested adopting an indirect, impersonal approach to social accountability through the use of citizen charters. These charters –visibly displayed in health facilities – informed patients about their rights, fees, routine medical treatments, and an anonymous SMS complaints mechanism. A local NGO managed the system and relayed information to authorities at the Ministry of Health – reporting results via an open access website.

How to: measurement, indicators and practical research tips

Doing research is the best way to understand the communities that will be included in social accountability programmes. Relevant information about the three elements proposed in this framework for context assessment may be captured through surveys and focus group discussions.

Before developing and tailoring tools for context assessment, implementers should think about those groups in a community that will most likely profit from participating in a social accountability scheme. This initial decision informs subsequent ones on sampling, focus group composition, and tailoring the interview questionnaires.

Applying the research instruments will yield information to construct relevant indicators for each of the three dimensions considered in this assessment framework, for example:

Collective action capabilities

- Level of participation in voluntary associations: percentage of respondents participating in various types of social organisations.

- Prevailing social norms and values: for example, reciprocity (prevalence of practices of gift-giving), sociality (practices of hospitality), solidarity (practices of mutual help), inclusiveness (presence of socially-marginalised groups).

- Prominence of horizontal social networks: Degree of proximity among network members, incentives and sanctions for cooperative behaviour.

Citizens’ attitudes toward service providers

- Empowerment vs.vulnerability: Citizens understand they enjoy inalienable rights and entitlements and if needed will act to make them effective vs. they believe they must gain the good will of service providers and public officials to receive benefits and services.

- Confidence vs.doubt: Citizens believe they can count on state officials and institutions to realise their entitlements vs. they do not believe that public officials will help realise their legal entitlements.

- Motivation vs. apathy: Citizens believe they can exercise their agency and bring state officials to account vs.they believe that the prevailing problems dealing with the public sector cannot be overcome, no matter what they do.

Trust in institutions

- Likert scales for levels of trust in broad range of state and non-state institutions: Options ranking from very high to very low trust.

For examples of a survey tool, focus group discussion guidelines and suggestions for constructing relevant indicators see Participatory monitoring to improve performance of government services and promote citizen empowerment: A success story from the Philippines.

Adopt tailored approaches to achieve sustainable, positive results

That corruption takes a toll on citizen welfare is indisputable. However, what motivates people to act against it can vary dramatically across contexts. Anti-corruption practitioners are therefore encouraged to evaluate contexts thoroughly to decide which social accountability tools are best suited to bring positive and sustainable results.

Practitioners and policymakers should adopt a tailored approach to social accountability that builds on the resources available to communities to act against corruption. It is therefore important to:

- Assess whether the conditions for facilitating collective citizen action are present.

- Try to understand corruption risks in the delivery of public services from the perspective of users.

- Engage the right stakeholders in support of the anti-corruption initiative.

Best practices associated with the three relevant dimensions of context

Collective action capabilities

- Participation-intense interventions such as community scorecards, social audits, or citizen monitoring are adequate when collective action potential is high.

- Interventions based on individual inputs such as citizen report cards, SMS reporting, or citizen charters are appropriate when collective action potential is low.

Citizen attitudes

- Capacity building should directly address identified challenges to citizen empowerment, confidence and motivation.

Trust in institutions

- Bring on board actors and institutions that are trusted in the community. They can play a pivotal role in support of the articulation, aggregation and transmission of citizens’ voice.

Limitations to participatory approaches

In continuing this discussion, we should acknowledge some of the limitations to participatory approaches and emphasise that social accountability is not a silver bullet. Authorities’ response to citizen inputs and whether they enforce sanctions against wrongdoers is often beyond the reach of what direct citizen involvement can achieve – at least in the short run.

Without sanctions, accountability has limited impact, yet enforceability tends to be the most difficult component to incorporate into social accountability programmes because it often requires institutional reforms and, ultimately, political will. Nonetheless, citizen voice and engagement can be determining factors to create greater public awareness of the need for legal and institutional reforms and to spawn political will.

We therefore need to concentrate on designing social accountability approaches that – as well as articulating citizen voice – promote constructive, regular, and predictable engagement with official institutions and actors.

- (Landell-Mills 2013; Johnston 2014)

- (Baez-Camargo and Jacobs 2011; Fox 2015)

- (Arroyo and Sirker 2005; Rocha Menocal and Sharma 2008; Gaventa and McGee 2010; Gaventa and Barrett 2012; DFID 2015; Mcneil and Malena 2010).

- (NORAD 2011; O’Mealley 2013; DFID 2015; Fox 2015)

- (UNDP 2010: 11)

- The model and its components reflect a widely accepted operationalisation of the concept of social accountability. For similar approaches see Arroyo and Sirker (2005).

- (Putnam 1995)

- (Stahl, Kassa, and Baez-Camargo 2017)