Query

Are there any gender transformative approaches to anti-corruption in the field of development cooperation? What methods and specific measures can be used to make anti-corruption projects gender transformative?

Gender transformative approaches

Social transformative discoursesdc1ed33ddcec in society have been around since the 1800s, with women’s groups, religious groups and other groups that focused on injustices such as slavery, women’s rights and class structures (MacArthur et al. 2022). Gender inequality in particular rose in prominence in the field of international development in the 1990s, after the Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (1995) included specific gender mainstreaming objectives (MacArthur et al. 2022). While this was considered an important inclusion to the declaration at the time by some, other gender and women’s rights experts quickly began to doubt the transformational potential of gender mainstreaming in a neo-liberal climate, where it had, according to them, turned into an instrumental exercise without addressing important underlying power relations (Rutgers 2018:5). These criticisms then paved the way for the innovative conceptual framework that was put forward by Dr Geeta Rao Gupta at the International AIDS Conference in 2000 who distinguished between gender neutral, gender sensitive and gender transformative approaches (Gupta 2000).

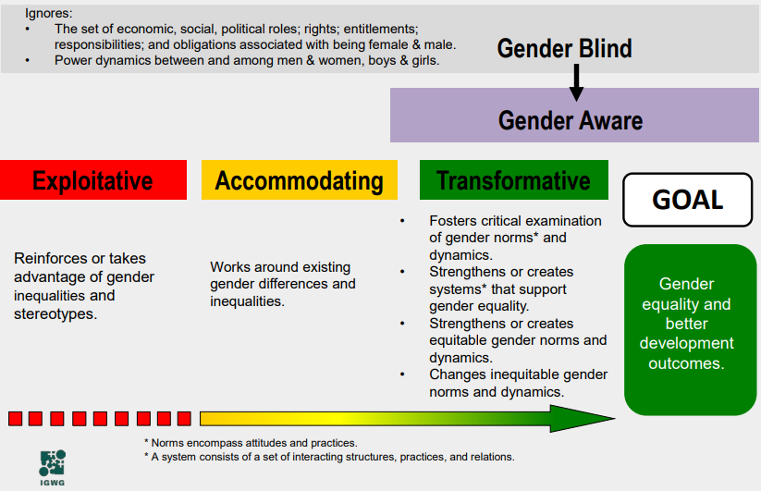

Since Gupta’s conceptual framework was put forward many development organisations have designed their own continuums based on her three concepts. These continuums illustrate the degree to which gender norms, relations and inequalities are analysed and explicitly addressed during a project design, implementation and monitoring (IGWG 2017:19). This aims to help move outcomes from development project outcomes from ‘do no harm’ to ‘do more good’ (MacArthur et al. 2022), moving down a continuum from gender blind to the goal of a gender transformative. As an example of ones of these, the Interagency Gender Working Group’s (IGWG 2017) illustration of the continuum is below:

Figure 1: the gender integration continuum

IGWG 2017.

The central notion behind gender transformative approaches is emphasised in the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA)’s (2023:4) definition, that it ‘support[s] gender equality by explicitly addressing the underlying causes of gender inequality, such as legislation, policies, norms, stereotypes’. That is, gender transformative approaches not only acknowledge gender inequalities and attempt to address the different needs of different genders but take a step further in redressing gender inequalities and the underlying structural barriers and social norms which cause these power asymmetries. Gender transformative approaches typically aim to tackle several areas of change at the same time, taking a multi-stakeholder and inclusive approach so that gender transformative change will come about quickly and be sustainable (Capacity4dev 2023).

Many have also sought to integrate intersectionality into gender transformative approaches, recognising that there are multiple intersecting and overlapping forms of social difference tied to structures of privilege and inequality (MacArthur et al. 2022). Gender identity alone is a limiting single issue analysis of people's experiences of discrimination and oppression. There are identity categories that according to their varied positioning in contextual social hierarchies and proximity to power make a person more or less exposed to discrimination; these can include, for example, rurality, ethnicity, disability status and poverty (Bergin 2024:45). Gender transformative approaches would therefore seek to address the root causes of inequalities for those in different groups, acknowledging that each is caused by particular harmful norms, beliefs and structures.

The FAO, IFAD and WFP (2020:6) identified six core characteristics of gender transformative approaches in projects. They studied 15 projects that employed gender transformative approachesin multilateral agencies, NGOs, non-profit foundations and the private sector and found the following common characteristics which were embedded into their broader development activities:

- to address the underlying social norms, attitudes and behaviours that perpetuate gender inequalities, which are rooted in discriminatory social, economic and formal and informal institutions, policies and laws

- use participatory approaches to facilitate dialogue, trust, ownership, visioning and behaviour change at several levels

- require critical reflection of deep-rooted social and gender norms and attitudes to challenge power dynamics

- explicitly engage with men and boys to address concepts of masculinity and gender

- engage with influential norm holders, such as traditional and religious leaders and others in leadership roles

- and use flexible approaches adapted to different contexts (FAO, IFAD and WFP 2020:6)

It should be noted that this is not an exhaustive compilation of gender transformative approaches, and projects do necessarily not need to employ a strict model, methodology or tool (FAO, IFAD and WFP 2020:5). It is, however, useful to identify core characteristics of gender transformative projects as there may be projects that achieve gender transformative goals without outwardly labelling themselves as gender transformative.

This is a particularly important point for this Helpdesk Answer as, given the limited evidence on gender transformative anti-corruption interventions thus far, it will instead examine projects which both label themselves as gender transformative and those which exhibit some gender transformative core characteristics but may not define themselves as such. While some anti-corruption interventions may exhibit the characteristics of addressing social norms which are rooted in policies (and so on), use participatory approaches, engage with influential norm holders and are adaptable, fewer tend to exhibit the characteristics of critical reflection of gender norms and the engagement of men and boys to address concepts of masculinity.

Norms and structures that hinder gender equality and promote corruption

Power dynamics in society affect and enable both corruption and gender inequality. Corruption and gender inequality are related in complex ways and are both perpetuated by social norms and structures, which can be overlapping and exacerbate one another. The same power imbalances that result in gendered discrimination and exclusion from decision-making and other societal structures can also enable corrupt acts and patterns to continue.

Social norms are defined as the unplanned result of individuals’ interactions and can be understood as a grammar of social interactions (SEP 2023). They specify what is acceptable and what is not in a society or group but cannot be identified only by observing behaviour (SEP 2023). Regarding gender inequality, social norms (or gender norms) may take the form of expectations such as men are breadwinners and women are caregivers, men are better suited to workplace leadership roles whereas women should dedicate more time to their families. In terms of corruption, they could the perception that women are less likely to be corrupt than men.

Structures (or structural determinants) are the socioeconomic and political processes that structure hierarchical power relations, which stratify societies based on class, occupational status, level of education, gender and more (BMJ 2020). In terms of gender inequality, these could be discriminatory policies and legislation, inadequate maternity leave, the gender pay gap, barriers to accessing education and limited access to reproductive health services such as contraception and safe abortion. For corruption, this could be a rigid and opaque bureaucracy.

There is an overlap in several of the social norms and structures that affect both gender equality and corruption negatively and perpetuate power imbalances. Table 1 provides several examples of these:

|

Social norms |

Potential impact on gender equality |

Potential impact on corruption |

|

Gendered stereotypes of leadership roles |

Fewer women in leadership roles and unfair recruitment bias. Male-dominated leadership may result in decisions being made that may not take women’s needs into account (O’Brien, Hanlon and Apostolopoulos 2023). Women are more likely to earn less and hold less management/decision-making power if they are not considered or encouraged to apply for leadership roles in the workplace. |

Results in an unequal access to power and resources which can facilitate corrupt practices towards the disadvantage of the underrepresented community. Undermines female leaders’ ability to enforce rules and regulations and limits their network building ability, therefore reducing their ability to counter corruption. Corruption often happens in informal networks, which excludes women, meaning female leaders may have more difficulty in detecting corrupt acts (Merkle 2022:12; UNODC 2020a:36). The lack of inclusivity in corrupt networks may also help to maintain them and the continuance of network members’ corrupt behaviour (UNODC 2020a:36). |

|

Gendered patronage systems* |

Patronage systems can constrain the advancement of women’s political careers (Correa 2016). In some cultures, women are often excluded from practices such as wasta,** meaning they may have less access to official processes or jobs (Alsarhan et al. 2020). |

Patronage systems may facilitate corruption and are a form of favouritism based on gender in which a person is selected, regardless of qualifications or entitlement, for a job or government benefit due to connections (Transparency International n.d.). |

|

Gendered norms of property ownership |

In many countries, men have much higher levels of land and property ownership than women (Gaddis, Lahoti and Swaminathan 2021). This is often because women perform unpaid activities during marriage, so have fewer opportunities to acquire property (Gaddis, Lahoti and Swaminathan 2021). Many customary tenure regimes in the world consider women’s land and property rights secondary to men (Richardson, Debere and Jaitner 2018) |

Lower levels of property ownership mean women have less of a voice in their communities and in politics, and less income meaning they are more vulnerable to sexual exploitation and corruption (Richardson, Debere and Jaitner 2018) |

|

Structures |

||

|

The informal economy |

Women make up a disproportionate percentage of workers in the informal sector, leaving them without the protection of labour laws, social benefits, health insurance or paid sick leave, as well as lower wages and unsafe conditions (UN Women n.d.). However, this may result in women losing their livelihoods if the informal sector is reduced. |

Studies show that high levels of corruption favour an increase in the informal economy (Ouédraogo 2017). |

|

The gender pay gap |

The gender pay gap means women are, on average, paid less than men. This means that women are less financially independent and may rely more on social benefits. |

The gender pay gap hinders the economic growth of a country (Betray, Dordevic and Sever 2020). Studies show that slower economic development and growth is also associated with higher levels of corruption (Bai et al. 2013). Lower income makes women more vulnerable to sexual corruption when trying to access resources; in Colombia and South Africa male water utility staff were soliciting sex from women in exchange for water (Feigenblatt 2020:15). |

|

Unequal access to education |

Unequal access to education may result in women and girls (and other marginalised groups) having less independence and career potential in their adulthood. |

Higher education quality is related to lower levels of perceived corruption (Spruyt et al. 2022) and failure to provide guaranteed access to education can create corruption risks, such as bribes in exchange for school placement. Less awareness of rights can make people more vulnerable to corruption and less able to seek redress. |

|

Lack of enforcement of laws |

This may lead to unenforced gender equality laws. |

This may lead to unenforced anti-corruption laws. |

* Gendered patronage systems refer to the support and privilege that an organisation or individual bestows to another, which are based on social arrangements that are distorted by gender (Correa 2016).

** Wasta is defined as ‘the practice of using personal connections or influential relationships to gain advantages, favours, or even shortcuts past administrative roadblocks. These can include securing employment, accessing services, obtaining permits or even bypassing bureaucratic hurdles’ (Arabic Online 2023).

As seen from the above examples, gender equality and anti-corruption efforts are mutually reinforcing, particularly when addressing the same norms and structures that cause power imbalances.

Gendered forms of corruption

The complex relationship between gender and corruption extends beyond just the causes and drivers of gender inequality. Gender can also influence and shape the types of corruption that an individual is more likely to encounter or engage in.

For example, a study analysing gender and corruption in sub-Saharan Africa found that women are more likely to pay bribes for fulfilling their home-making role, whereas men are more likely to pay bribes to bureaucracies or the police for fulfilling their roles as breadwinners (Bukuluki 2024). Another study by Bauhr and Charron (2020) found that women are more likely to engage in corruption that is driven by ‘need’ (to receive services or avoid abuses of power) whereas men are more likely to engage in corruption that is driven by ‘greed’ (to receive special illicit advantages, privileges and wealth). The authors hypothesise that this is due to women being socialised into care taking roles, which means more time invested into activities such as education and healthcare and excluded from decision-making positions where ‘greed’ corruption is more likely to take place (Bauhr and Charron 2020:99).

Other forms of corruption have gendered aspects, such as sexual corruption (also known as sextortion). Sexual corruption is defined by Bjarnegård et al. (2024) as ‘when a person abuses their entrusted authority to obtain a sexual favour in exchange for a service or benefit that is connected to their entrusted authority’. Sexual corruption includes both extortive and collusive relationships where a service or benefit is at stake, such as a grade at school or a permit from a government agency. Given that there is a lack of legal definition for the behaviour in most jurisdictions, the prevalence is hard to capture and relies on anecdotal evidence (Feigenblatt 2020:11).

Documented cases show that women are disproportionately targeted, but men, transgender and gender non-confirming people are also targeted (Feigenblatt 2020:11). Family and patriarchal relationships are sometimes part of sexual corruption dynamics, in which women and girls are used to ‘pay’ for the bribes that relatives cannot afford (Feigenblatt 2020:12). Men can also be affected by sexual corruption, such as documented cases of male migrants experiencing sexual violence during their migration (Bossière n.d.). Some research shows that perpetrators deliberately exploit gendered hierarchies and harmful social myths around sextortion and sexual violence experiences to inflict shame and humiliation that stigmatises their masculine identity (Bossière n.d.).

The impact of social norms and structures on the gendered dimensions of sexual corruption are complex. For example, norms and structures shape the tendency of women to be in domestic and childbearing roles, limiting their financial independence and making them more likely to rely on public services where they may be exposed to sexual corruption (Coleman et al. 2024). Norms may make reporting sexual assault difficult, due to shame or potential ostracization by the family and community (Coleman et al. 2024). Moreover, gender power dynamics are further compounded by aspects such as poverty, rural and urban living, education levels, disability and sexual orientation (Coleman et al. 2024).

The current discussion and implementation of gender transformative approaches in anti-corruption

Gender transformative approaches are relatively new in the discourse of anti-corruption. The majority of the evidence and literature on the approaches that currently exists are primarily from development sectors such as sexual health and reproductive rights (SRHR), food security, education, health and other related areas.

Nonetheless, the following section examines the current conversation on anti-corruption gender transformative approaches which address the social norms and structures that perpetuate power imbalances. It does so through analysing five areas in the field of anti-corruption which engage with gender equality: anti-corruption policies and institutions, political participation, economic empowerment, land rights and access to public services. This is not an exhaustive list of relevant interventions, but instead intends to provide a snapshot of some of the main discussions in the sector. It also provides case studies of projects that have (some to more and some to a lesser extent) employed a gender transformative approach.

While there has been some progress in the anti-corruption field and this section will discuss some anecdotal examples of how anti-corruption projects could be considered as gender transformative, as well as gender projects which could have adjacent anti-corruption outcomes. It should be noted that not all these projects have been explicitly labelled as gender transformative, but many still fit within (some of) the six core characteristics of gender transformative approaches (as defined by FAO, IFAD and WFP a2020:6).

Anti-corruption policies and institutions

The UNODC (2020:73) recommends that all anti-corruption policies should incorporate considerations of gender inequalities, given that policies are an important tool for change, particularly regarding structures which hinder gender equality. Policymakers should be encouraged to think in pluralistic forms of masculinity, femininity and non-heteronormative forms. This means targeting the root cause of gender inequality in parallel with efforts to counter corruption in the implementation of deeper institutional reforms to build integrity (UNODC 2020a:69).

Policies that address structures which perpetuate gender inequality (and may additionally affect corruption) can include, for example, reforms such as policies to address the gender pay gap, paternity and parental leave, and addressing sexual harassment (Shang 2022). Anti-corruption policies that can also act as gender transformative tools could include gender responsive public procurement policies, gender budgeting and gender quotas in parliaments and judiciaries to target both corruption and gender equality (UNODC 2020a). While these target structural barriers, policies can spur on norms changes if implementation is successful.

The UNODC (2020) also highlights the importance of collecting data for evidence-based policymaking. There is a lack of data and primary research on how gender dynamics interplay with accountability, transparency and power structures (such as educational attainment, literacy rates and the gender digital gap etc.) and qualitative data is generally scarce (UNODC 2020a:70). Having reliable data on the prevalence of different varieties of corruption and associated gendered processes would enable policy recommendations to be prioritised and appropriately localised (UNODC 2020a:68). Additionally, it is considered essential that any policies that are designed to address the impacts of corruption on women should include women themselves during the policy formation process (Observatorio Cuidadano de Corrupción. 2022:16). This would help to ensure that policies targeting structural barriers are more effective, targeted and localised.

Ghana's National Anti-Corruption Action Plan (NACAP) was developed between 2010 and 2011 through a multi-stakeholder consultation process that included women's groups (UNODC 2020a:115). As a result of these multi-stakeholder consultations, there are signs that the coordinating body of anti-corruption has since been taking sexual corruption more seriously. For example, the 2017 NACAP implementation report states that 27 institutions have developed and published sexual harassment policies for their workplaces and awareness has been raised in the country on the risks of sexual corruption (UNODC 2020a:115-116). Later in 2019, after awareness had been raised on the issue, the BBC Africa Eye produced a documentary on sex for grades at the University of Ghana, which resulted in professors losing their jobs (UNODC 2020a:116). While these initial consultations were not labelled as gender transformative approaches, they did result in policy change, which eventually contributed to wider societal change and awareness of sexual corruption.

Anti-corruption agencies can also promote gender equality awareness among their staff, enhancing understanding of these issues for those involved in policy implementation and oversight. The Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) conducted a study into gender mainstreaming and mentoring in the APEC anti-corruption agencies between 2020 and 2021 across 21 member economies. Their findings suggest that there is gender segregation in the agencies, with teams being largely male or largely female. A subtle gender bias was also identified among staff, with a higher level of bias towards those of childbearing age. They also collected data on identifying the internal gendering mainstreaming measures that have been implemented within their agency and the particular struggles that women face, particularly regarding the balance of work and personal responsibilities (APEC 2021:18). The study aims to provide a gender integrated approach for the anti-corruption agencies, complemented by a gender targeted approach, to support the learning and development of its female employees (APEC 2021:3-4). It aims to do so primarily through sustained mentorship programmes (APEC 2021:4).

Political participation

Increasing the participation and representation of women in the political sphere can help to achieve gender equality aims through changing both social norms (that women are not suited for leadership positions) and structures (promotion criteria, work-life balance and a lack of mentorship for women). This is important as a lack of women’s political representation means that women rely on policies that are designed by men to address women-specific needs, which may not always be suitable for their needs (Feigenblatt 2020:24).

Therefore, it is considered important to address this issue through affirmative actiona601bae99501 such as political participation policies. The evidence on whether political participation can also achieve anti-corruption objectives at the same time is more complex, and some experts have raised concerns that affirmative action could lead to tokenistic representation (Soyaltin-Collela and Melis Cin 2022).

Braga and Scervini (2017) provide an example of how female participation can lead to policies benefiting women by examining whether the gender of elected politicians influences political outcomes at the municipal level in Italy. They found that, while the gender of politicians does not affect the general quality of life, it does increase significantly the efficacy of policies (such as childcare, water provision, health and environment) targeting women. This is measured through a higher fertility rate in regions with more women in political office.

Similarly, in the case of the Nordic region, which is characterised by a high proportion of women elected to parliament, studies show that social welfare policies tend to be higher when there is a higher proportion of women in government. Wangnerud (2009:58) links this to the fact that welfare state policies free women to enter the paid workforce, they provide public sector jobs that disproportionately employ women, and hence the political interests of working women increase enough to create an ideological gender gap (Wangnerud 2009:58). Wangnerud’s (2009:65) wider assessment of the evidence on women in parliament concludes that female politicians contribute to the strengthening of women’s interests.

However, whether this can act as an anti-corruption measure, the ‘fairer sex’ theory,606dbd54f842 has more recently been called into question by several studies. Bjarnegård, Yoon and Zetterberg (2018) found through looking into gender quotas and corruption in Tanzania, that while ‘clean slates’ (that is female political candidates with no previous ties to the current political class) could reduce corruption, they rarely exist in politics (Bjarnegård, Yoon and Zetterberg 2018:118). Instead, they found that the increase in female legislative representation in Tanzania was accompanied with persistent and high levels of political corruption (Bjarnegård, Yoon and Zetterberg 2018:118). Baur and Charron (2020) present similar findings from France that newly elected female mayors result in lower levels of corruption, whereas re-elected ones do not, indicating that women adapt to corrupt networks.

Branisa and Ziegler (2011) also examined the link between gender inequality and corruption using a sample of developing countries looking at corruption, representation of women, democracy and other control variables. They found that corruption is higher in countries where social institutions deprive women of their freedom to participate in social life, even accounting for the representation of women in political and economic life. The authors suggest that these findings show that where social values disadvantage women, neither political reforms towards democracy nor increasing the representation of women in political positions will be enough to reduce corruption (Branisa and Ziegler 2011).

Nonetheless, despite recent evidence showing that women’s representation in political spheres is unlikely to break established corrupt networks, Merkle and Wong (2020) point out that challenging patriarchal structures can also change attitudes towards corruption. They suggest that, instead of relying on female politicians to bring about anti-corruption change, policymakers should focus on more grassroot level initiatives. The inclusion of women into politics would diversify the thinking of government and create more multidimensional thinking in politics, benefiting the wider society (Merkle and Wong 2020).

Despite the contradictory evidence on whether increasing women’s political participation could be a gender-transformative approach, it is useful to consider a real-life example reflecting these theoretical complexities. The UNODC (2020:97) provides the case of audit reports that were used to uncover corruption in Brazil. As mayoral elections drew closer, audit reports were published showing the proportion of audited funds spent in a way that violated the law. This resulted in votes shifting to a female candidate. It was found that if 20% of the audited funds were wrongly spent, the proportion of votes going to female candidates rose by roughly 11.8%. However, interestingly, this only applied to new female candidates as voters did not see female mayoral candidates in re-run elections as equally incorruptible (UNODC 2020a:98). Despite achieving increased representation of women in politics, it could be argued that this intervention in fact relied on perpetuating social norms of women as the ‘fairer sex’ to achieve these gender equality and anti-corruption goals.

Economic empowerment

Both gender norms and structures have an influence on women’s economic empowerment and financial inclusion.667f28af564f Having a bank account and savings is important for women as this enables them to make investments into their businesses and households and increase their economic independence (Marcus and Somji 2024:76). However, gender norms have limited women’s financial inclusion through male control over women’s income and savings, gender inequalities in access to mobile phones, restrictions on women’s mobility (Marcus and Somji 2024:80), as well as inheritance norms meaning that women can only access property through spouses or male relatives.

Evidence also shows that those who are economically disempowered (in this case, women) are more vulnerable to corruption, particularly when accessing basic services and goods that are provided by the state where they may be vulnerable to bribery or sexual corruption (Feigenblatt 2020). The following examples are projects designed to enhance women's financial inclusion and promote economic empowerment through various interventions, all of which also contribute to anti-corruption efforts.

The Egypt’s Women Citizenship Initiative, which was a multistakeholder initiative involving the government of Egypt and several UN agencies, established in 2011, worked towards increasing women’s financial inclusion in the Egypt. This involved addressing the gender gap in access to ID through a public awareness campaign and mobile registration points to support women gaining a national ID card (Marcus and Somji 2024:84). Through outreach in marginalised areas, the initiative resulted in nearly 460,000 additional women receiving a national ID card or waiting for one over the three years of the project, enabling more women to access financial services, with potentially far-reaching impacts on their economic empowerment (Marcus and Somji 2024:84). While this project did not have explicit anti-corruption aims, the provision of national IDs that will enable them to access financial services is an important step in ensuring the economic empowerment of women. Research shows that marginalised groups (particularly lower-income rural women) are more likely to be targeted for bribery as they are seen as an ‘easy target’ due to social norms (Peiffer 2023:22).

Public procurement can be leveraged to achieve policy objectives which can include the economic advancement of minority groups and addressing harmful systemic structures (Williams 2023). When working towards empowering women, it is referred to as gender responsive procurement, which can involve actions such as awarding contracts to women-owned businessescf570bf205a5 or writing parental leave policies (including paternity leave policies) into procurement legislation so that they accrue points in competitive bidding processes (Williams 2023; UNODC 2020:72). Opening public procurement to a wider range of businesses is important to ensure competitive markets and weakening patronage networks, which plays a role in reducing the risk of corruption (UNODC n.d.). In the Dominican Republic, for example, legislation was passed requiring 5% of public contracts to be awarded to medium, small and micro enterprises (MSMEs) owned by women (Williams 2023:12). This was considered as one of the most impactful in the region and by 2020, 29% of government contracts went to women-owned businesses, up from 10% in 2012 (Williams 2023:12). However, while gender responsive procurement can help to promote women’s economic empowerment through addressing structural barriers, it does not necessarily challenge harmful gender norms.

A civil society organisation (CSO) in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Search for Common Ground conducted a project to improve the policy and institutional environment to facilitate women’s cross-border trade in East Africa. Its aims were to increase the formalisation and value of goods traded by women and, at the same time, prevent and respond to gender-based violence and harassment of women traders (SFCG 2023). The project activities included advocacy to decision-makers to amend or implement policies which facilitated women’s trade in the region and educating women traders of the laws and their rights. The project evaluation found that women saw both an increase in the commercial value of their traded goods, better access to credit, and 75% felt that gender-based violence had decreased, and many became more confident to report harassment and violence (SFCG 2023:5). 66% of respondents said they had changed their behaviour and attitude towards customs officials, with less corruption being one of the criteria (SFCG 2023:10).

A similar project, the Great Lakes Trade Facilitation Project, which was a 5-year regional project implemented in the Democratic Republic of Congo, Rwanda and Uganda aimed to facilitate cross-border trade by increasing capacity and reducing trading costs and gender-based threats for women informal traders (Parshotam and Balongo 2020:10). It did so through the construction of new border facilities, cross-border markets and pedestrian lanes and the establishment of a cross-border committee which regularly meets to harmonise bilateral trade issues (Parshotam and Balongo 2020: 10). The construction of women-sensitive infrastructure (such as solar panel lighting) allowed women to operate more safely as night, as well as the border markets which served as logistical platforms and lowered their vulnerability to predatory middlemen (Parshotam and Balongo 2020:10). This helped to challenge the underlying structures that prevented women traders from achieving their economic potential. However, the extent to which this intervention successfully addressed underlying gender norms is unclear.

Land rights

Globally, there are a number of discriminatory practices against women in the context of land rights and ownership, such as inadequate land tenure, lack of credit, unequal pay and low levels of decision-making (Halonen 2023). Many of these are driven by structures and social norms. Moreover, land corruption30c322bdba51 further deprives women access to land and land ownership, and can take the form of bribery or demands for sexual favours in return for land services (Transparency International 2022).

There have been a few examples of strategies being employed to shift gender norms in the context of land rights and land ownership for women. For example, the Ghana Integrity Initiative (GII) in collaboration with Women in Law and Development in Africa (WiLDAF) have been promoting women’s land rights in Ghana through participatory video (UNODC 2020a:123). The video explains how land corruption occurs in the Upper Eastern region of the country, often when a woman is widowed and the husband’s family illicitly obtains the land, sometimes using bribery (UNODC 2020a:123). These videos have been used to educate and raise awareness to Ghanaian women’s rights in land ownership and challenge the traditional gender roles. This aims to challenge and transform the social norms that have led people in the region to believe that women should not own land, therefore rendering them more vulnerable to land corruption.

However, it should be noted that while this intervention aims to educate the populace on women’s land rights, it should not be solely the responsibility of women to drive change. Many gender transformative projects which focus on changing social norms rely heavily on the education of men and boys to work towards gender equality (for example, see UNESCO’s Transforming MEN’talities initiative aims to change mindsets and policies by uplifting promising narratives and practices of positive masculinities).

Access to public services

Women are disproportionately affected by corruption at the point of access to public services as they tend to have more interaction with such services, particularly the provision of healthcare and education (Merkle 2021:4). Women also face greater risks of poverty so may be denied services if they cannot make informal payments (Merkle 2021:4). In these contexts, they may be particularly at risk of sexual corruption, when sexual demands are made from them in return for public services (Merkle 2021:4).

Coleman et al. (2024) note that to effectively address sexual corruption in the health sector, a combination of gender responsive strategies that deal with the consequences of gender inequality and gender transformative approaches that target the underlying drivers of inequality should be employed. Changes to laws and policies should promote anti-corruption and ensure equitable distribution of resources and services, along with the removal of structural barriers hindering access to healthcare (Coleman et al. 2024).

Where corruption at the point of access to public services is widespread, it is important that there are safe and secure whistleblowing and community complaints systems to report misconduct. However, there are also gendered dimensions to reporting corruption. A recent large-scale education survey in Madagascar found that, while 80% of respondents believed citizens were free to report corruption, only 25% believed women and girls had a safe space to report sexual corruption (Bergin 2024:48). This highlights the need for safe community complaint and whistleblowing systems which have gender and power dynamics considered in their design and implementation. When considering social norms, designing complaints and whistleblowing systems in a gender transformative manner is difficult. There are multiple social norms that prevent women from reporting misconduct, particularly in cases of sexual corruption. For example, there is often the cultural stigma related to reporting wrongdoing and research shows that women are particularly influenced by the reaction of their peers (Feldman and Lobel 2010).

To ensure that complaints and whistleblowing systems are gender sensitive, it is important to ensure they have protective rights in their policies, mobile units to reach rural settings, have online platforms and hotlines that can anonymise reports, and work with women’s organisations and other relevant organisations (Zúñiga 2020:8-9). There is significantly less research on gender transformative complaints and whistleblowing mechanisms, but a starting point would be to ensure that community’s (including women, girls, men and boys) are all engaged in a participatory manner in the design of the reporting mechanism and educated on the importance of reporting wrongdoing.

In terms of remedial actions for whistleblowers and reporting persons, there are some suggestions from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) and the United Nations Working Group on Business and Human Rights on providing gender transformative remedies. These include remedies that should be responsive to women’s experiences and should aim to bring about systemic changes in discriminatory power structures (UN n.d.:35). For example, compensation settlements should never exclude access to judicial routes, and non-disclosure agreements should never be used, unless requested by affected women (UN n.d.:34). In addition to legal advice other experts also consider that access to mental and physical health services to prevent the process from causing further re-victimisation should be provided to affected individuals (Feigenblatt 2020:30).

Finally, Bys (2022) investigates Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Abuse (PSEA) in the aid sector, and argues that emerging bottom-up, Global South perspectives are offering novel and effective ways to protect women and girls and address harmful social norms and structures. As an example of a novel approach to protecting women and girls, Bys refers to the Feminist Safeguarding Policy, which was developed by and for the young feminist fund FRIDA. Their policy moves away from a paradigm that presents safeguarding as a protective project rooted in Global North principles that can infantilise young feminists, into a more participatory one based on consent and context. While this is not an anti-corruption intervention in itself, it is useful to consider such women-led safeguarding policies for all staff that work with vulnerable communities.

Gender transformative approaches at the project level

This section provides an overview of resources on gender transformative project design, implementation, and monitoring and learning. It should be noted that most of the literature is taken from other development sectors as there are limited resources on anti-corruption gender transformative project approaches. Nonetheless, this information could be useful when designing an anti-corruption project that intends to take a gender transformative approach, as well as a project focusing on gender with adjacent anti-corruption aims.

Social norms change

Social norms change is already an important component and objective of many development projects, particularly those that work on dismantling gender norms which perpetuate harmful practices such as female genital mutilation (FGM) and child marriage. Development projects that focus on social norms change may include (for example) interpersonal dialogue and reflection on beliefs, values and behaviours, peer support, social mobilisation, collective celebration and linking individuals with professional services (USAID n.d.:5).

There are different areas of society that lead to change and equality. These can be categorised as individual (self-belief and agency), relations (power dynamics and decision-making), culture (challenging norms and stereotypes), and systems and structures (policy and institutional change and rights) (ATVET for Women project 2020). In terms of specifically driving change in gender norms, Marcus and Somji (2024) identified the different levels and potential interventions which could trigger social norms change. Examples of individual-level change include:

- cognitive change: recognition of the benefits of the new norms

- emotional identification with the new norm and behaviour

- changes in perceptions of the values and behaviours of others in a reference group

- empowerment or personal transformation that encourages people to behave in a new way

Examples of changes in social networks include:

- being part of a community of supportive others – peers, family, online networks, etc.

- opportunities to act in new ways – to test new behaviour before fully committing to it

And examples of broader drivers of change include:

- economic incentives or infrastructure development that makes work more available to women

- economic stress that leads to changed behaviour patterns and that may or may not shift norms in the long term

- legal or other forms of compulsion that mandate and, over time, normalise new forms of behaviour (Marcus and Somji 2024:18).

Social norms change is complex as norms are deeply embedded into societies, with change often happening over a long period of time. It can transpire when a small minority of individuals are willing to transgress existing norms, particularly those who are autonomous in their decision-making behaviour and, by repeatedly demonstrating behaviour in disagreement with the existing norm, they may slowly change the expectations of others (Andrighetto and Vriens 2022). However, it is not always easy to predict how or when this may occur, and which interventions will target the right mechanisms driving behaviour (Andrighetto and Vriens 2022).

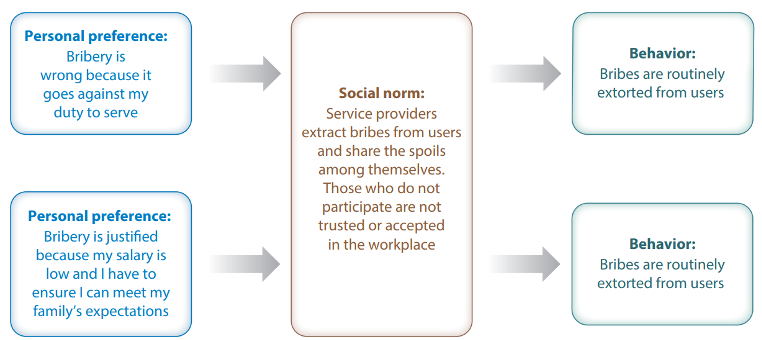

Kubbe, Baez-Camargo and Church (2024) suggest that adding a social norms lens to anti-corruption could prove useful given that legislative reforms alone cannot tackle the complex networks of the corrupt (Kubbe, Baez-Camargo and Church 2024). Where formal laws are not enforced, informal social networks associated with corruption are built and bound together using common understandings, mutual expectations, and accepted behaviours (Kubbe, Baez-Camargo and Church 2024). Figure 2 below illustrates how these informal social norms and networks can perpetuate corrupt behaviours:

Figure 2: social norms resulting in and perpetuating corrupt behaviour

Kubbe, Baez-Camargo and Church 2024:430.

An example of a social norms change approach in countering corruption could be to focus on shifting perceptions of the descriptive norm (what people think others do) to reduce corrupt acts or conduct a public awareness campaign highlighting bribery as being not as widespread as people think (Kubbe, Baez-Camargo and Church 2024). However, while social norms change could be useful in countering corruption (and gender inequality) there have been very few tested social norms anti-corruption interventions in the real world (Kubbe, Baez-Camargo and Church 2024).

Project design and implementation

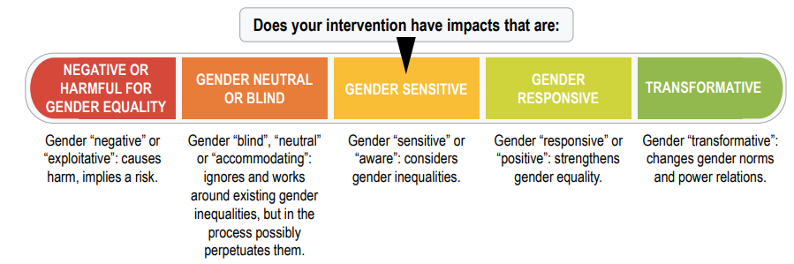

Figure 3: guidance on assessing the different gender-related project impacts

OECD 2021:3.

At the initial project design phase, there are several questions that can be asked to either assess whether the intervention will achieve gender transformative outcomes. Rutger’s (2021) GTA Quickscan tool is a useful resource to help staff assess whether a project can be considered gender transformative or not during the project design. This tool can be applied to projects in any sector and could potentially be useful for anti-corruption interventions. It asks the following questions (with accompanying sub-questions which can be found in the tool) for reviewers to score between 3 (very well) and 0 (not done):

- Is the programme design gender transformative?

- Is the programme based on human rights?

- Does the programme address power relations?

- Does the programme talk about norms and values?

- Is the programme inclusive of gender and sexual diversity?

- Does the programme empower women (all people who identify as a woman) and girls?

- Does the programme engage men and boys?

Another important tool in the project design and early implementation phase is a gender analysis framework. Gender analysis frameworks are instruments for understanding gender inequalities and can be used to visualise the main areas where gender inequality exists within in a target community (Espinosa cited in Feigenblatt 2020:15). CARE International provides a rapid gender analysis as a useful resource. It is particularly important in gender analyses that, at the project design phase, the gender analysis includes a human rights and intersectionality approach, as well as analysis of unequal power dynamics (Capacity4dev 2023).

THET and the Liverpool School of Tropical Medicine (LSTM) recommend in their guidance in gender equality and social inclusion (GESI) toolkit for health partnerships to develop an intersectional gender analysis matrix during the project design (with a proposed template on page 14 of the publication). This systematically explores the different ways that gender power relations manifest as inequalities/inequities and how these intersect with other forms on inequality/inequity (THET and LSTM n.d.:13). The matrix may reveal quantitative differences between and among genders in morbidity and mortality, for example, and can help to identify factors beyond gender which can lead to social exclusion and how they intersect with gender.

To develop a gender transformative theory of change (ToC), Hillenbrand et al. (2015:19) recommend that project staff should ensure that a participatory approach is used. This means engaging critical local stakeholders in defining what success looks like, ensuring that qualitative and quantitative indicators are drawn from local realities, and context-specific monitoring and evaluation systems that are sensitive to power dynamics be created. A collective mapping process should also be used to help strengthen accountability and transparency across stakeholder groups, staff and, in the later reporting, to donors (Hillenbrand et al. 2015:19). The ToC itself should provide a nuanced understanding of gender relations and gender constraints in the target areas, informed by the consultations with local stakeholders (Hillenbrand et al. 2015:19).

As an illustrative example, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) has designed a theory of change for gender transformative programming for food security, nutrition and sustainable agriculture. This was drafted with the working hypothesis that addressing the root causes of gender inequalities and triggering a transformative change in policies, institutions and society at the individual, household and community levels are essential to achieving zero hunger (FAO n.d.). While this is not focused on anti-corruption, it can still be a useful reference point when considering gender transformative anti-corruption ToCs.

The UNODC provides a useful resource on mainstreaming gender in organised crime and illicit trafficking projects (2020b) which provides guidance on questions for the project situational analysis, project description (including a logical framework), the project management and examples of gender aspects in organised crime and illicit trafficking projects. While the resource primarily focuses on gender mainstreaming approaches (rather than gender transformative approaches), many of the points are still applicable. For example, it notes that project performance indicators should be formulated in a manner that makes them able to measure changes for both men and women and how the programme is achieving transformative gender related sustainable development results (UNODC 2020b:8).

The OECD’s guidance on gender equality and empowerment of women and girls guidance for development partners suggests that traditional monitoring and evaluation frameworks based on measuring performance against predetermined targets and visible change may not necessarily be appropriate in measuring change in gender relations or gender discriminatory social norms (OECD 2022). They instead provide the example from a project, Finland, UN Women Nepal, which instead used a storytelling methodology to measure change. The mass storytelling tool combines the depth of storytelling with the statistical power of aggregated data for tracking patterns and trends in social behaviour. The project used the storytelling tool SenseMaker to track and interpret programmatic contributions linked to the SDG5 indicators to changes in social norms and gender equality (OECD 2022).

Finally, any gender transformative project training or project events and workshops more generally should reframe their events from ‘how can we get more women to attend this training?’ to asking, ‘how would we approach capacity building if it was designed with marginalised gender groups in mind, and if it was designed jointly with marginalised gender groups?’ (Practical Action 2019:10).

Indicators to measure progress

Commitment No.7 of the Lima Summit seeks to identify progress in actions to promote gender equity and equality in anti-corruption policies. Progress in these actions have been assessed through three policy indicators and three practice indicators (Observatorio Cuidadano de Corrupción 2022:12). The policy indicators include:

- Is there a group, agency or entity in charge of promoting women's leadership and empowerment in public anti-corruption policies?

- Are there provisions that lead to the promotion of gender equity and equality in anti-corruption policies?

- During the last two years, have there been any policy developments for the promotion of gender equity and equality in anti-corruption policies?

And the practice indicators include:

- Are the leading positions of the working group on women's leadership and empowerment held by women?

- In the last two years, has the working group on women's leadership and empowerment promoted actions at the national and international level to promote gender equity and equality in anti-corruption policies?

- Do you consider that there has been significant progress in the last two years towards compliance with this mandate?

Conclusion

While the evidence does suggest that there is a gradual increase in awareness in the anti-corruption sector regarding gender transformative approaches, anti-corruption does lag behind other development sectors. There are several areas that could potentially be strengthened in this regard, identified by gaps in the current literature. Anti-corruption interventions tend to focus on the empowerment of women and girls, which may mean that the onus is placed on marginalised groups to advocate for their rights instead of international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) and government agencies holding responsible institutions to account. The focus on only women and girls is also limiting in the sense that it is important to engage all members of society to bring about transformative change. Furthermore, a focus on projects that ‘empower’ or ‘upskill’ women without long term plans of monitoring and sustainability may not achieve transformative change. Every project that has such aims should be mindful of its context, particularly those that are hostile to women’s autonomy. Finally, the literature shows a gap in intersectional analysis and what that means for anti-corruption, particularly gender transformative anti-corruption projects and how to integrate this effectively into project objectives.

- Social transformative discourse is communication that aims to bring about social change through contesting existing social norms and structures.

- Affirmative action for gender equality is included into Article 4 of Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women 1979.

- The ‘fairer sex’ theory refers to the concept that women are more trustworthy and public spirited than men and therefore are more effective at promoting honesty in government (Dollar, Fisman and Gatti 2001).

- Financial inclusion is defined as defined as the access and ability to use affordable financial products and services that meet the needs of individuals and businesses, and can include payments, savings and credit (Marcus and Somji 2024:80).

- The definition of a women-owned business varies from country to country. In Kenya and Tanzania, 70% of ownership must be led by women to qualify, whereas in the US 51% ownership qualifies businesses (Williams 2023:5).

- Land corruption is a sectoral form of corruption and is defined as the abuse of entrusted power for private gain while carrying out the functions of land administration and land management’ (De Maria and Howai 2021).