Corruption and gender in the judiciary

A well-functioning judiciary is essential for addressing corruption effectively. However, the judiciary itself is also corruptible. Judicial corruption ‘includes all forms of inappropriate influence that may damage the impartiality of justice and may involve any actor within the justice system’.c103766f3ca2 Such corruption involves bribery by court users and illegitimate political influence on judges by the executive, parliamentarians, or other power holders. Political actors trying to influence who gets appointed, reappointed, and promoted as judges is a common tactic to limit judicial independence and may take place within and outside of the legal framework.c555414d6da4 Another tactic is to control judicial budgets and judges’ tenure, salaries, and benefits. Undue influence may also come from within the judicial hierarchy.badf097afa08

Surveys show that the judiciary is regarded as one of the most corrupt of all public institutions in Latin American and African countries.b5fd91cb4bf8 While these perceptions might not be accurate,84088cf2b44b they should not be ignored – as judicial corruption drives impunity, erodes public trust in the judiciary, and prevents equal access to justice, contributing to the undermining of state legitimacy.477294dd2c67

Research also finds a link between gender and corruption. One of the most consistent findings in the literature is that countries with greater numbers of women involved in decision-making also have lower levels of corruption. Early studies hypothesised that this could be explained by women being more honest or risk-averse, and thus less likely to engage in corrupt practices than men.96deed1d807b Later studies suggest that the link is better explained by differences in how women and men are recruited (or not) to decision-making roles.f4502936c5bf

Corruption presents an obstacle to women’s recruitment, as women rarely have access to predominantly male power networks. ‘Shadowy’ arrangements in recruitment tend to favour the already privileged, who in most societies are men. Since women are not trusted as partners in these ‘networks of sensitive exchanges’,ae7cb37fe25a they are locked out of positions of power. This is especially the case in systems where the formal institutional environment is turbulent, unsteady, and unpredictable, and where clientelism thrives – such as in fragile state settings like Haiti. Women usually benefit from more merit-based, formal, and transparent recruitment procedures.6b32b6c6c074 Research further shows that there is a link between merit-based recruitment and reduced corruption in public service.c8dde0e6a722

Insights from the Haitian judiciary

While the bulk of research on the gendered aspects of corruption in government focuses on the legislature, recent research from Haiti shows a strong link between gender and corruption in the judiciary.9be14cf0686a

Haiti is a highly patriarchal society and currently ranks among the least gender-equal countries in the world.240c1c5b791b This is, among other things, reflected in the high prevalence of gender-based violence,64599f68cb6a the ‘feminization of poverty’,da4387dd31ce and the absence of women from decision-making roles in Haiti.5f58ca01b5bc Haiti is also regarded as highly corrupt. According to Transparency International, in 2021 Haiti ranked number 168 out of 198 countries in terms of perceived corruption.

Through decades of authoritarianism under François ‘Papa Doc’ Duvalier and his son Jean-Claude ‘Baby Doc’ Duvalier (1957–1986), the judiciary functioned as an extension of the executive. The judiciary has remained largely dysfunctional and highly corrupt during Haiti’s rocky transition towards democracy. Since the mid-1990s, a substantial amount of aid has been provided by foreign donors to reform and strengthen the judiciary as part of state- and peacebuilding efforts. Success has been limited, as the judiciary is still far from independent.b1ce2713430f Political actors in the executive and the legislature constantly interfere in the appointment and removal of judges and prosecutors, as well as in the handling of court cases. Bribery, threats, surveillance, harassment, and – in more extreme cases – assassinations and assassination attempts, have become part of everyday life for justice actors in Haiti.bb7558c91887

Haiti adopted France’s civil law tradition after independence in 1804. This entails a system of magistrates, which includes judges and prosecutors. There are two ways to become a magistrate in Haiti today: through direct appointment and, since 1996, through the magistrate school (Ecole de la Magistrature (EMA)). Around 25% of Haiti’s magistrates have thus far been appointed through EMA.

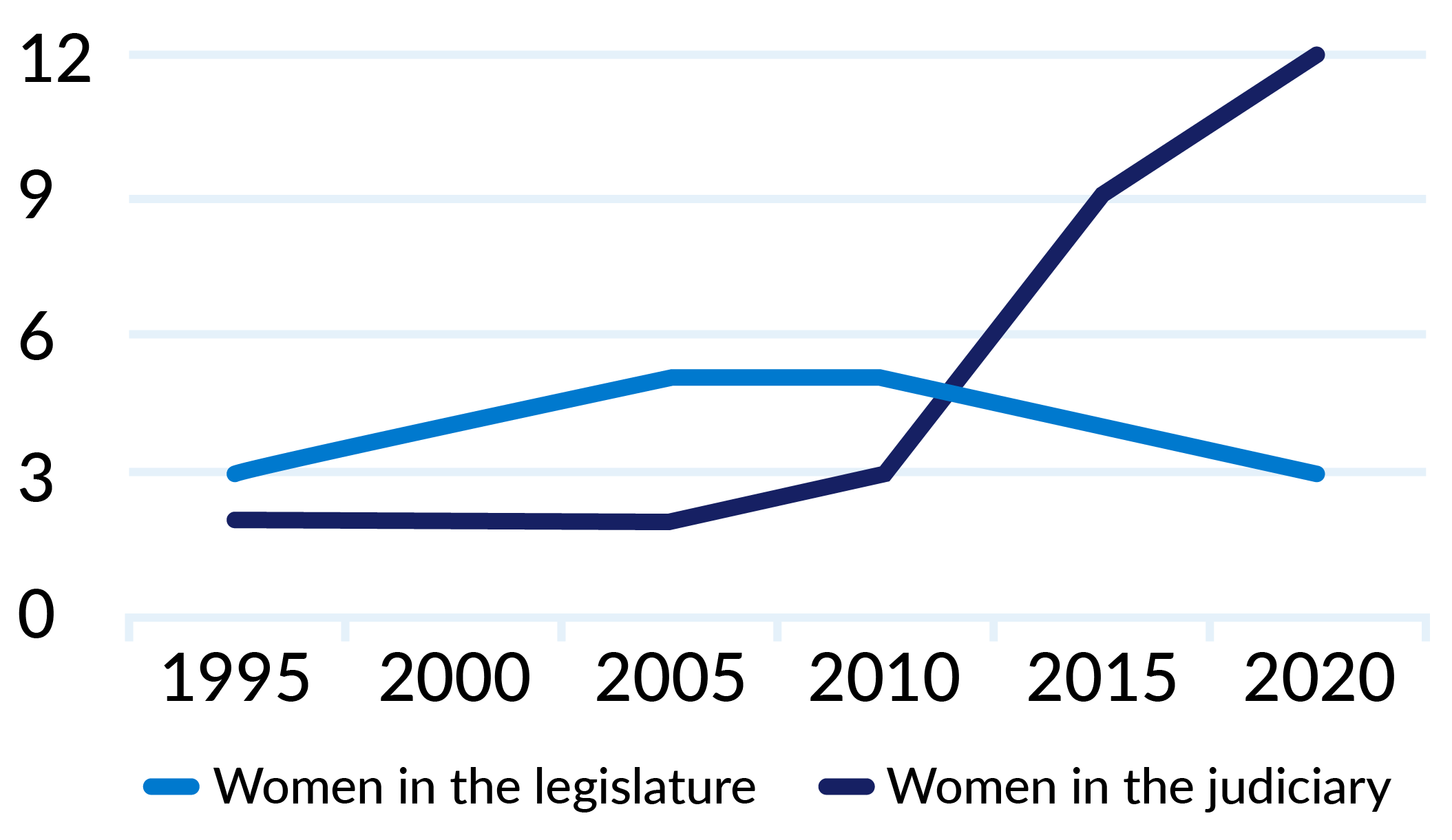

Complete and historic statistics on the evolution of women’s presence in the Haitian judiciary are hard to come by. The first woman magistrate, Ertha Pascal-Trouillot, entered the Court of First Instance in Port-au-Prince in 1979. In the mid-1990s, the proportion of women judges was reportedly 2%.89245538bb7c As shown in Figure 1, the past couple of decades have seen an increase in the proportion of women judges to 12% (101 women judges out of 867 judges in total), whereas women’s representation in the legislature has remained extremely low (just 3 out of 118 Members of Parliament, or 2.5%, in the last parliament were women).

Figure 1. Women’s representation in Haiti

Note: Vertical axis represents the percentage of women in the respective bodies.

Sources: CSPJ (2015, 2018); IPU (2019); author’s interviews.

Haiti has adopted legislation aimed at increasing women’s representation in decision-making. A constitutional amendment on gender quotas from 2012 states that women should make up at least 30% of all public positions, including in the judiciary. However, fulfilment of the quota is still lacking, as the amendment contained neither implementing legislation nor sanctions for non-compliance. Disappointment in the quota became evident during the 2015 national election when women accounted for fewer than 10% of legislative candidates, and no women were elected to parliament.688c0ebff883 In other words, gender reforms fall short of explaining the increase of women judges in Haiti. The cause is more likely found in less gender-targeted judicial reforms.

Direct appointments and the importance of (male-dominated) power networks

Until the creation of the magistrate school in 1996, all magistrates were directly appointed by a procedure clearly stated in the law. Candidates require a law degree and several years of experience in the legal profession or legal education. They are nominated by departmental and municipal assemblies on lists which are submitted to the President of the Republic, and then take up a shorter, probatory internship at the magistrate school. The Higher Judicial Council, created in 2007, is responsible for ensuring that magistrate candidates for peace tribunals, courts of first instance, and appeals courts fulfil all the necessary conditions.ae1c84e10039 In reality, however, this procedure is rarely followed, and the process for direct appointments appears both arbitrary and highly politicised. Haitian magistrates interviewed for this study stressed the importance of knowing someone close to power – usually a Member of Parliament or another politician, sometimes referred to as a ‘parent’ – who could lobby the president for your candidacy.

The extreme poverty and politically volatile climate in Haiti have weakened formal institutions, paving the way for clientelist networks. Directly appointed magistrates talked about how they had to make phone calls to ‘the right people,’ or else their application would be ‘lying in a drawer somewhere.’3f00c7325ce6 Direct appointments also entail a certain degree of dependency and an expectation that appointees ‘owe someone something.’ Several magistrates believed that direct appointment was a way for Haitian politicians to maintain control of the judiciary and judicial decisions through clientelist networks.

However, in Haiti, as in many other cases, these power networks are mostly dominated by men, as women have been largely absent from public roles throughout the country’s modern history.46ab4c27ca90 Hence, the dynamics of direct appointments appear to be both informal and gendered. According to Haitian magistrates – men and women – it is very hard for women to gain access to the judiciary through direct appointment. As stated by a female ex-judge: ‘[V]ery few women generally join the judiciary [through direct appointment]. Unless it is a woman who is a good friend of a politician; you can see that this person joins the judiciary. No problem. But not many. It is rather men.’d39cdf6f419e

Women gaining access through merit

Most magistrates are still directly appointed, but the creation of the magistrate school in 1996 provided an alternative route to the judiciary. The school, largely funded by foreign donors, was part of judicial reform efforts to train a ‘new breed’ of more professional, competent, and independent judges and prosecutors.f0d22cf3f63d The school provides 16 months of initial training for law graduates to become magistrates and to enrol, aspiring magistrates go through an entrance exam. Appointments to the judiciary are organised by the school and are made through competitive oral and written examinations administered by a committee.7897e9ffde1f Appointments usually happen shortly after graduation, depending on available posts in the judiciary.1c87aba38a1c

The magistrate school thus offers a more transparent and merit-based route to the judiciary. Several of the women magistrates interviewed for this study who had chosen to go through the magistrate school saw this as a better opportunity for people without the right contacts. As stated by one female justice of the peace: ‘[F]or direct integration, you must have contacts. You must first have a thesis, then be a lawyer, then have contacts. Those who have no contacts like me still get to participate through the magistrate school… I know no one.’ba7c2a7ca81b

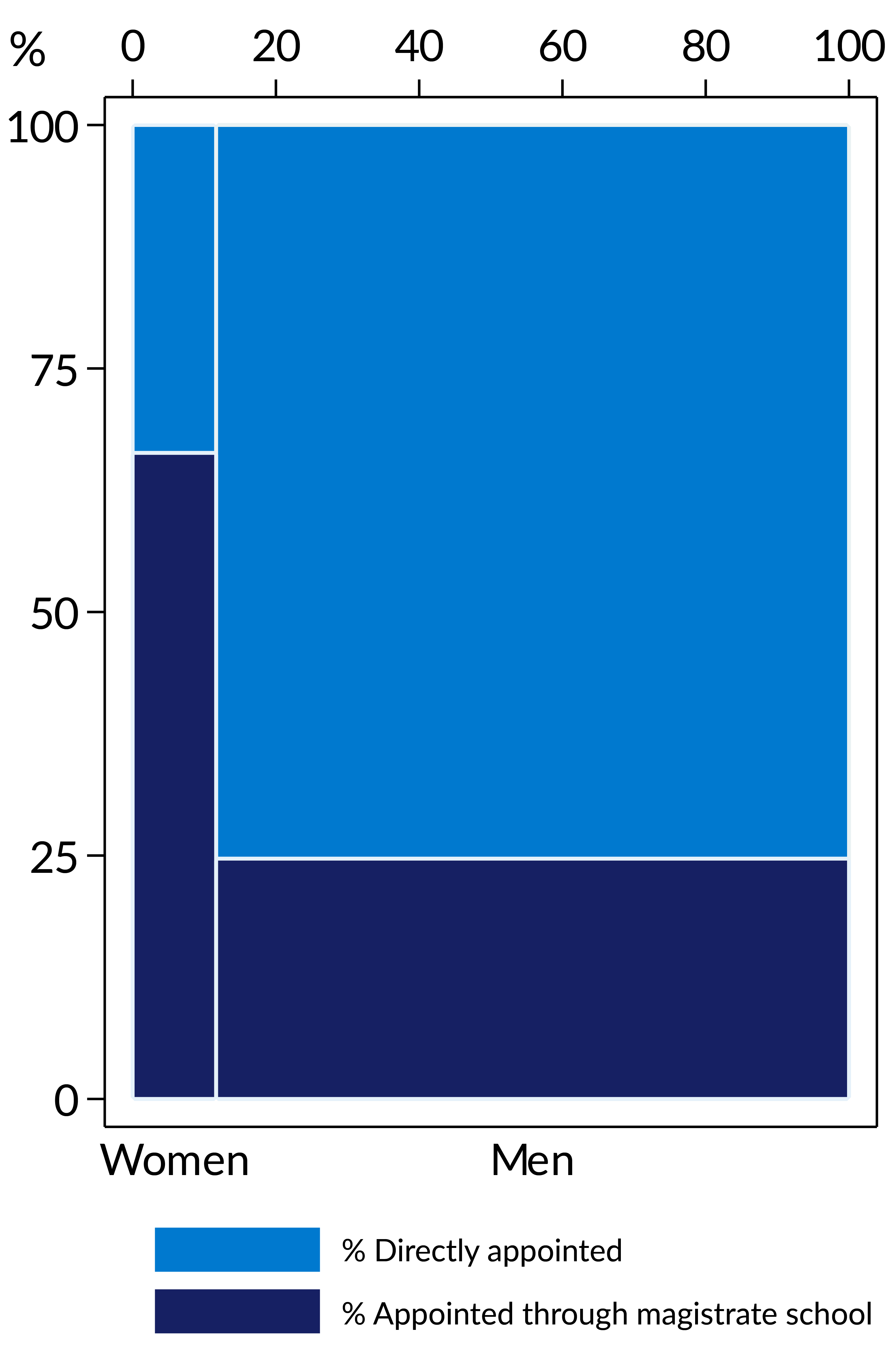

Such stories are supported by the numbers. Two hundred and fifty-six out of Haiti’s 867 judges have graduated from the magistrate school since its creation.d1c05c8e8584 During the same period, the proportion of women judges increased from 2% to 12%. Approximately 66% of current women magistrates went to the school, compared to approximately 23% of current male magistrates. By comparison, 77% of men and just 34% of women have been directly appointed (see Figure 2). Combined with an increase in the number of judicial posts (from 660 in 2013 to 867 in 2020), it is fair to say that the introduction of this alternative route helps women find a way into the judiciary.

Figure 2: A higher percentage of female judges are appointed through the magistrates school compared to men.

Note: The horizontal axis refers to the percentage of women versus men magistrates. The vertical axis refers to the percentage of appointments through EMA versus direct appointments.

Forging a path: What does the future hold for women in the judiciary?

The insights from Haiti find that reforms aimed at making the judiciary more professional and independent may simultaneously boost women’s representation in this sector. By simply rewarding merit over powerful connections, the creation of the magistrate school has opened up opportunities for women to access the judiciary in increasing numbers, and now offers an alternative route to direct appointments.f1c217ca5228 It remains to be seen whether the women graduating from the magistrate school will change the culture of the judiciary from within if they take on leadership positions or move up to higher judicial positions, or if they will be sidelined into courts of less import or assigned only to cases dealing with issues affecting women and children.

Nonetheless, the current trend presents some hope, as Haiti has been struggling to implement reforms that more explicitly target women’s underrepresentation in decision-making roles, such as the 2012 constitutional amendment on gender quotas..b50758a14418f26fb3e34441

Simultaneously, both the executive and the legislature have shown limited willingness to create a stronger and more independent judiciary. Direct appointments have been a way for actors within these branches of government to maintain control over the judiciary. The operation of the magistrate school – and the continued future influx of women to the judiciary – relies on ongoing international support. At the same time, this makes the functioning of the school vulnerable to external shocks and changing donor priorities. Bilateral donors and international agencies that are working for good governance reforms and women’s representation in Haiti should therefore strive for sustainable ways to continue supporting the magistrate school.

- Gloppen, 2013.

- Transparency International, 2007.

- Gloppen, 2013.

- Latinobarometro, 2018; Afrobarometer, 2020.

- UNODC, 2020.

- Messick and Schütte, 2015.

- Dollar, Fisman, and Gati, 2001; Swamy et al., 2001.

- Goetz, 2007.

- Bjarnegård, 2013.

- Kittilson, 2006; Sundström and Wängnerud, 2016; Rothstein, 2018.

- Dahlstrom et al., 2011.

- Tøraasen, 2022.

- UNDP, 2020.

- IHE/ICF, 2018.

- Padgett and Warnecke, 2011.

- Bardall, 2018; Moore, 2021.

- Berg, 2013; Mobekk, 2016.

- Tøraasen, forthcoming; Jean-Baptiste, 2021.

- Oral accounts by sources in the Higher Judicial Council (CSPJ) and the UN mission to Haiti.

- Bardall, 2018.

- Le Moniteur, 2007a.

- Interview, female magistrate, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, November 2019.

- Interview, female magistrate, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, November 2019.

- Tøraasen, 2022.

- According to the law, the committee consists of a Supreme Court judge, a law professor, a lawyer, the school’s director, and a vaguely defined ‘qualified personality’ (Le Moniteur, 2007b).

- Interviews, Haiti, 2018–2020. Apart from one female interviewee (out of 50 interviewees in total) who claimed that her appointment to the judiciary through the magistrate school was delayed due to political disagreements between her and the then president, there was little evidence that this process was ‘shadowy’ to the same extent as direct appointments.

- Berg, 2013.

- Interview, female magistrate, Pétion-Ville, Haiti, June 2019.

- Numbers are not absolute as no data exist for public prosecutors, and because some magistrates may have left the profession since graduating from EMA. These numbers however give a strong indication of the gendered dynamics of the two appointment procedures.

- While the creation of the Higher Judicial Council was meant to provide some oversight over direct appointments, there is little data on how this has worked out in practice.

- Author’s interviews with Haitian women’s activists, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2018–2020.

- Bardall, 2018.