1. Rationale for this research and key questions

In public policy documents, international development organisations and their partners implementing anti-corruption interventions widely recognise the importance of monitoring and evaluation (M&E).cc4368c36dcb These organisations universally describe the goal of M&E as learning about and improving outcomes from their work, while simultaneously ensuring they are accountable to stakeholders. In a context where there remain wide evidence gaps related to anti-corruption, and organisations are under ever greater pressure to assess results, the role of M&E has never been more critical.c610f0e39e4a However, despite the public commitment to M&E, the existing evaluation evidence base for anti-corruption work has been subject to little direct analysis. This U4 Issue aims to address this gap. It explores whether M&E is producing the quality of evidence that organisations in this field need to understand their effectiveness and impact.

There are a small number of guidance materials available to help practitioners think through the complexities involved in evaluating anti-corruption activities.d39b228fad53 Experts have particularly advocated Theory of Change (ToC) approaches as a basis for planning and evaluating programmes in this field.e5a36214f9b9 An ‘articulation of how and why a given intervention will lead to specific change’, ToC is intended to provide a more comprehensive basis for analysing context-dependent development interventions like anti-corruption.3d5f847cce59 In addition, there have been recent innovations in measuring corruption which might be drawn upon for M&E.06f16d14df0a

With organisations working in the anti-corruption field having regularly conducted evaluations for over a decade, a review of whether good practices are actually being applied is timely. This report is the first in-depth examination of the quality of the evaluation evidence available for anti-corruption interventions.ee871ff867ba Through a structured review of 91 evaluations, the report explores several research questions:

- What criteria can be used to assess the quality of evaluation research for anti-corruption programmes?

- How large is the existing evaluation evidence base for anti-corruption programmes and what does it cover?

- To what extent are anti-corruption programmes set up in a way which prepares them for strong M&E?

- To what extent do existing evaluations incorporate advances in anti-corruption and evaluation theory, as well as new approaches to measurement?

- To what extent do evaluations address gendered aspects of corruption?

- What changes, if any, are needed in organisational structures and approaches to M&E?

The aim is to provide clear evidence on evaluation quality and prompt renewed debate around the role of M&E in the anti-corruption field.

2. A new framework for analysing the quality of anti-corruption evaluations

Evaluating anti-corruption interventions involves some complexities which, although not necessarily unique in international development, present significant challenges. These include the difficulty in observing and tracking changes in behaviour; the need to navigate different conceptual understandings of the problem; and the criticality of political, economic, and socio-cultural factors in influencing outcomes. An evaluation must be responsive to these issues if it is to provide an authentic account of an intervention.

While there are extensive materials to draw upon, there is not a ready assessment framework for assessing the quality of evaluations of anti-corruption interventions specifically. The six evaluation criteria published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development’s Development Assistance Committee (OECD-DAC) Network on Development Evaluation are a normative standard which has diffused in the international development sector.1d059a288130 The criteria are a ‘set of lenses through which one can understand and analyse an intervention’ but they do not in themselves specify how these questions should be addressed.6b1266a4d626 OECD-DAC has separately published quality standards on evaluation.9c86de70c115 Various writers on evaluation have additionally discussed different elements of evaluation quality but none provide a complete framework capturing key developments in the evaluation field, such as the spread of theory-based evaluation designs.6a57a554bb08 Lastly, many development organisations have their own evaluation assurance processes which again provide a source on standards.4f40e586d09d

The framework that has been developed is included in Annex A. It is divided into two parts: it first sets out criteria to assess whether programmes are set up in a way to support strong M&E, and then turns to the quality of the evaluation itself. As some evaluations represent a source of good practice, the framework was in part developed iteratively and refined through three rounds of review. The final criteria draw on the materials outlined above as well as practitioner guides on evaluation for anti-corruption interventions.e0d264369b68 This is the rationale for the emphasis in the framework on ToC. To truly understand intervention outcomes, the argument is that evaluators need to explore the underlying logic behind a programme, and make judgements based on a thorough analysis of the context. Further attention is given to measurement issues and the recognised importance of triangulating data sources to form a fully rounded view on changes in corruption levels and forms.e7155ee6d2c5 Finally, the criteria cover issues around participation, gender and intersectionality, evaluation use, and the wider application of lessons from evaluations.

3. Research design and methodology

3.1. Sampling strategy

The author constructed the sample of evaluations with the goal of providing as comprehensive a picture of practice as possible across the development sector. The sample therefore includes organisations with the most significant levels of anti-corruption programming (bilateral development agencies, multilateral development agencies, and foundations) as well as select CSOs with a global or regional presence. The author used OECD statistical data on development finance for the last decade as a starting point for identifying relevant organisations.5c571c08dd3e This identified USA, UK, Scandinavian development agencies, and Germany as large bilateral funders, and the World Bank Group, European Union (EU) and United Nations (UN) agencies as important multilateral agencies.99cf42784f45

The author then cast a wide net to attempt to identify evaluations from other organisations which may have smaller funding volumes but are influential in the field. Examples of organisations reviewed were foundations such as the Hewlett Foundation, the Open Society Foundation, and the Omidyar Network. The CSOs reviewed were organisations with regional and/or global operations which engage in anti-corruption efforts as part of their activities. Examples of such organisations were Accountability Lab, Basel Institute, Global Integrity, Integrity Action, the Natural Resource Governance Institute, Open Ownership, Publish What You Pay, Transparency International Secretariat (TI), and the UNCAC Coalition.

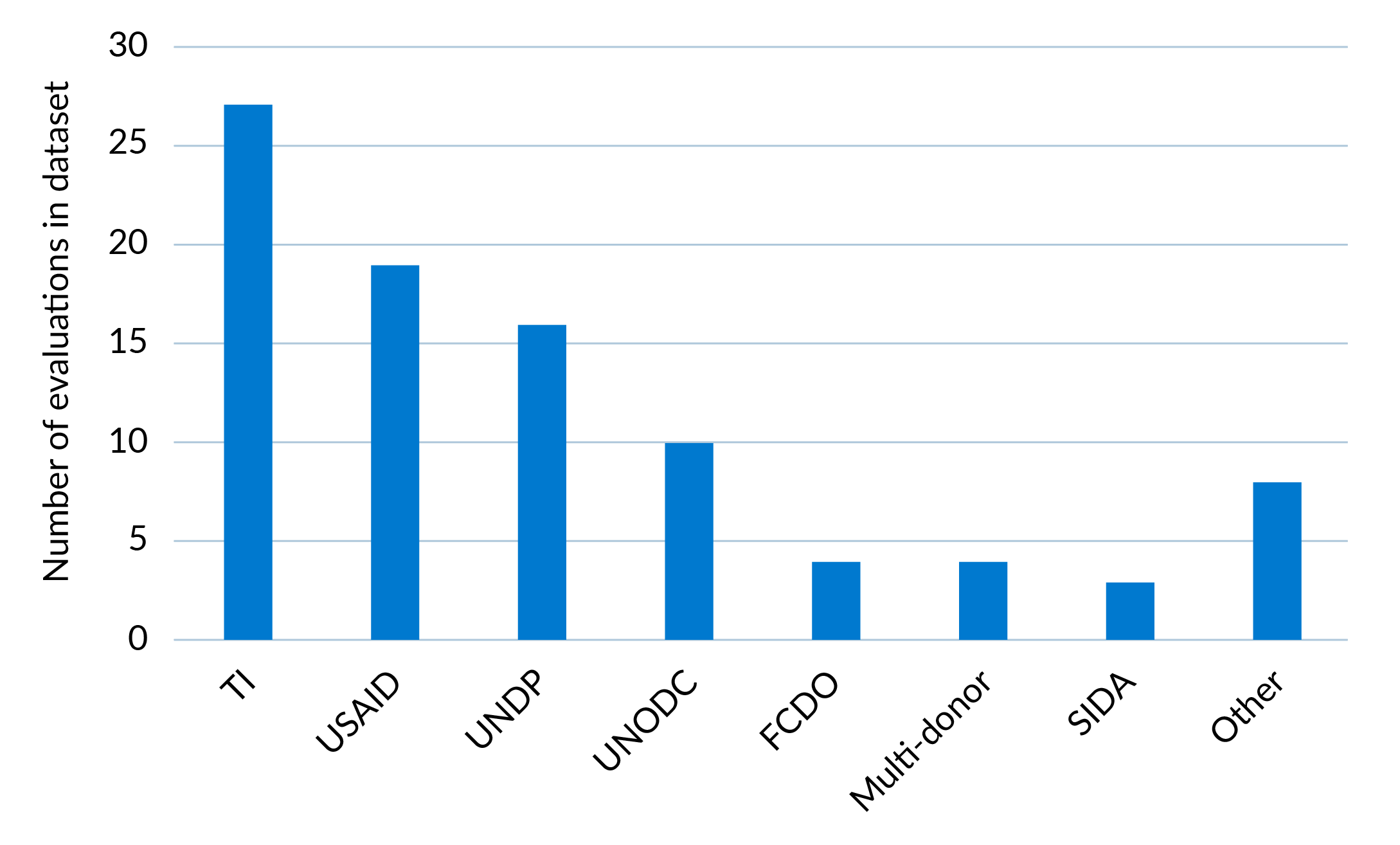

Reviewing relevant websites for these organisations, sometimes requiring searches using key words,72922b6608d4 yielded 91 evaluations from 11 organisations, as shown in Figure 1. Only evaluations covering programmes with explicit aims (stated internally at least) related to addressing corruption or a form thereof were selected. This was necessary to maintain the coherence of the sample but it is a limitation, the implications of which are discussed further below. The dataset covers evaluations published between January 2010 and October 2023. Of the reports identified, 92% were published in English.

While the review aimed to capture and assess as many relevant published reports as possible, it cannot be excluded that some published reports have been missed. It is also noted that 12% of the evaluations identified had a published midterm evaluation. These were not included in this analysis of quality as it would have distorted scoring, with some programmes in effect being assessed twice. A full list of the evaluation reports reviewed is provided in Annex B.

Figure 1: Organisations publishing evaluations

3.2. Limitations

There are several limitations to this report which relate to the forms of anti-corruption programmes covered in the dataset, the organisations represented, and the reliance on publicly available information. It should also be noted that the focus of this report is the quality of evaluation evidence, as opposed to discussion of any lessons about anti-corruption work these evaluations may hold.

As previously mentioned, the sample covers the evaluation of programmes which had aims specifically related to controlling corruption or forms thereof. This means that direct forms of anti-corruption programming are likely to be over-represented in the sample. One theory of anti-corruption holds that control of corruption comes about indirectly as part of wider societal transformation or institutional reform.40710c1a3d0e Related governance programmes, such as social accountability initiatives, public financial management, and rule of law reforms, can play important roles in reducing corruption. However, incorporating evaluations where there was no attempt internally to assess and understand the effects of the intervention on corruption risked losing the coherence and comparability of evaluations. Exploring the quality of evaluation in others of areas of governance work, and the lessons these evaluations hold for anti-corruption interventions, could be important avenues for future research.

Figure 1 shows that the dataset is weighted towards four organisations: TI Secretariat, the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC), which together commissioned 80% of the evaluations reviewed. The EU, German development agency Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit (GIZ), and World Bank are three development agencies working in this space which may be under-represented relative to their spending on anti-corruption activity. This is either because they do not routinely disclose full evaluation reports or because many of their interventions are indirect.

With the exception of the TI Secretariat, the largest international CSOs working directly on corruption issues do not appear to routinely publish evaluation work. National CSOs have also been excluded to create a manageable dataset. The consequence is that the CSO evaluations reviewed here took place within the framework of programmes funded by donors in the Global North. The paper may not therefore be a full reflection of local practice in evaluating in this field, although it is uncertain as to the extent to which national anti-corruption CSOs engage in formal evaluations outside of donor processes. This is not to disregard more informal learning processes which take place at international and national CSOs – these are important but are not the particular focus of this review.

The reliance on publicly available evaluation reports additionally affects the review. Most of the key organisations in this field commit to publishing evaluation work but retain the right to non-disclosure in certain circumstances, such as when evaluations are deemed politically sensitive. It is possible this could affect the sample: organisations might withhold evaluations which appear unfavourable or not publish evaluations considered of poor quality. The effect on the sample is hard to judge as the number and quality of unpublished reports is unknown.

In addition, there may be non-public programme materials of relevance to the rating of certain criteria in the framework. This is especially the case when assessing programme evaluability. For instance, a programme’s ToC or original proposal documents might be restricted for internal use but if incorporated in the review would lead to higher ratings. The organisations included in the dataset do not ordinarily make these types of documents publicly available.1f0098a520a5 This caveat to the research is therefore made clear where appropriate below, although it is also reasonable to expect that summaries of materials would be included in an evaluation report.

Finally, a written report cannot provide a complete picture of the dynamics around an evaluation process. A document tells us little about key issues related to evaluation, such as the power dynamics shaping how an evaluation was organised and its findings used. Without direct knowledge of the context, we also cannot make a full judgement on how reliable the account appears to be. The review provides indicators on these types of questions only.

4. Overview of the evaluation evidence base

The compilation of the dataset allows us for the first time to form an overarching picture of the breadth of evaluation evidence available to the anti-corruption field. Before turning to the analysis of quality, the following sections describe core features of the evaluation evidence base.

4.1. Types of evaluation in the dataset

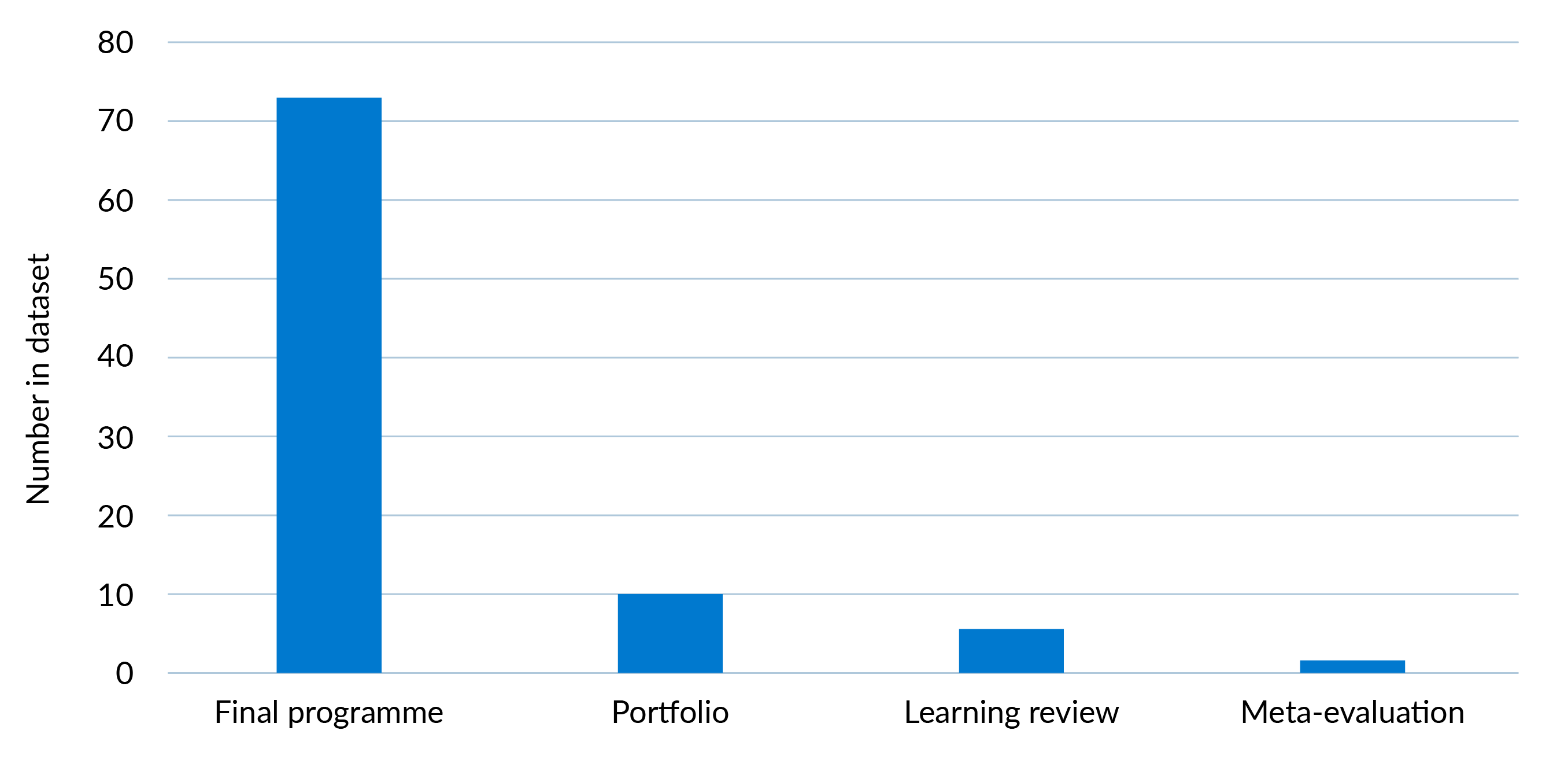

Figure 2 summarises the types of evaluation included in the dataset of anti-corruption interventions.

Figure 2: Evaluation types

Brief descriptions of each of these evaluation types are as follows:

- Final programme evaluation: An evaluation of a single programme at the end of its term. This is the majority of the evaluations in the dataset as shown in Figure 2.

- Portfolio evaluation: An evaluation which reviews multiple forms of anti-corruption programmes undertaken by an organisation either within a single country or across a wider body of work. There are ten evaluations of this type in the dataset.

- Learning review: A report where the sole objective is to identify lessons concerning a particular form of activity undertaken by the organisation.6e6175e9013d

- Meta-evaluation: A review assessing broader impact based on analysis of existing evaluation reports.

Alternative perspectives on evaluation

There are different terms in use in the evaluation field to categorise evaluations. Many experts use the term ‘impact evaluation’ and distinguish this from ‘programme evaluation’. Johnsøn and Søreide (2013, p.10) define impact evaluation as an assessment of ‘the causal effects of a programme, measuring what net change can be attributed to it’, while programme evaluation is an evaluation of ‘whether the programme has achieved its objectives and the effectiveness and efficiency with which it has pursued these objectives’. The challenge here is that over half of the evaluations reviewed explicitly have the goal of assessing impact. No distinction is therefore made in this paper between ‘programme’ and ‘impact’ evaluation, with the focus instead being on the different approaches used to evaluate.

In the evaluation field, there has historically been a strong preference for using experimental research designs and quantitative methods to assess impact (NONIE, 2009; Centre for Global Development, 2006). This view is contested by other commentators (see Aston et al., 2022; Stern et al., 2012). They make a distinction between the ‘counterfactual logic’ behind experimental designs and a ‘generative logic’ of causation, seeing the latter as ‘chiefly concerned with the “causes of effects”, that is, necessary and/or sufficient conditions for a given outcome’. They are open to using a much broader range of theory-based evaluation designs to understand contributions to impact (see Section 6.1 for examples).

The division stems from differences in the extent to which evaluation traditions engage with levels of complexity in development programming (see Roche and Kelly, 2012). In more simple forms of programming it may be possible to attribute changes to a particular intervention, for instance lives saved through a vaccination programme. Corruption, however, has been defined as a ‘wicked problem’ (Heywood, 2019), ie one that is continually evolving and will frustrate reformers. For this reason, the review advocates use of ToC as a means to unpack these complexities. The framework is nonetheless agnostic on evaluation design and methods, following the maxim that these choices should depend on the questions being asked.

4.2. What types of anti-corruption interventions have been evaluated?

The categorisation of interventions in Table 1 is in large part based on previous reviews of anti-corruption evidence commissioned by the Department for International Development (DFID, now FCDO) in 2012 and 2015.10092333eac4 Some interventions have also been added to reflect newer forms of programming pursued by development organisations, while some also overlap. The numbers shown in the table exceed 91 (the number of evaluation reports in the dataset) as each programme typically covers multiple types of intervention.

Table 1: Types of interventions evaluated

|

Category |

Type of intervention |

Number of |

|

Direct support |

Anti-corruption agencies |

24 |

|

Anti-corruption laws |

11 |

|

|

Anti-corruption strategies |

5 |

|

|

Financial intelligence units |

2 |

|

|

Indirect support |

Justice sector reform |

18 |

|

Procurement |

10 |

|

|

Open government |

10 |

|

|

Public financial management |

9 |

|

|

Local government |

7 |

|

|

Civil service |

5 |

|

|

Police |

3 |

|

|

Public service delivery |

2 |

|

|

Political parties |

1 |

|

|

Asset disclosure |

1 |

|

|

E-government |

1 |

|

|

Tax, revenue, and customs |

0 |

|

|

State-owned enterprises |

0 |

|

|

Privatisation |

0 |

|

|

Oversight |

Audit authorities |

13 |

|

Parliament |

6 |

|

|

Ombudsman |

2 |

|

|

Civil society |

Support to organised civil society organisations* |

65 |

|

Citizen engagement and awareness raising |

24 |

|

|

Media |

10 |

|

|

Community monitoring |

7 |

|

|

Private sector |

Business environment reform |

7 |

|

Company anti-corruption standards |

5 |

|

|

Collective action |

0 |

|

|

International |

International frameworks |

6 |

|

Transnational law enforcement |

2 |

|

|

Asset recovery |

5 |

|

|

Other |

Research |

16 |

|

Whistleblowing and complaints mechanisms |

15 |

|

|

Focus on specific sectoral corruption issues |

12 |

|

|

Education and training related to corruption |

4 |

|

|

Donor controls |

3 |

|

|

Mainstreaming |

3 |

* Category includes all evaluations published by TI.

The table shows that long-standing interventions favoured in international development – namely support to organised civil society, anti-corruption agencies, and justice sector reforms – have been most frequently evaluated. The volume of evaluation evidence is much more limited for newer approaches championed in the field, like mainstreaming anti-corruption work into other development programmes and collective action initiatives. Overall, the evaluation evidence base appears small in many areas. There are lots of promising types of interventions listed in Table 1 for which there is limited published evaluation evidence on their effectiveness and impact.

4.3. Geographic coverage of programmes evaluated

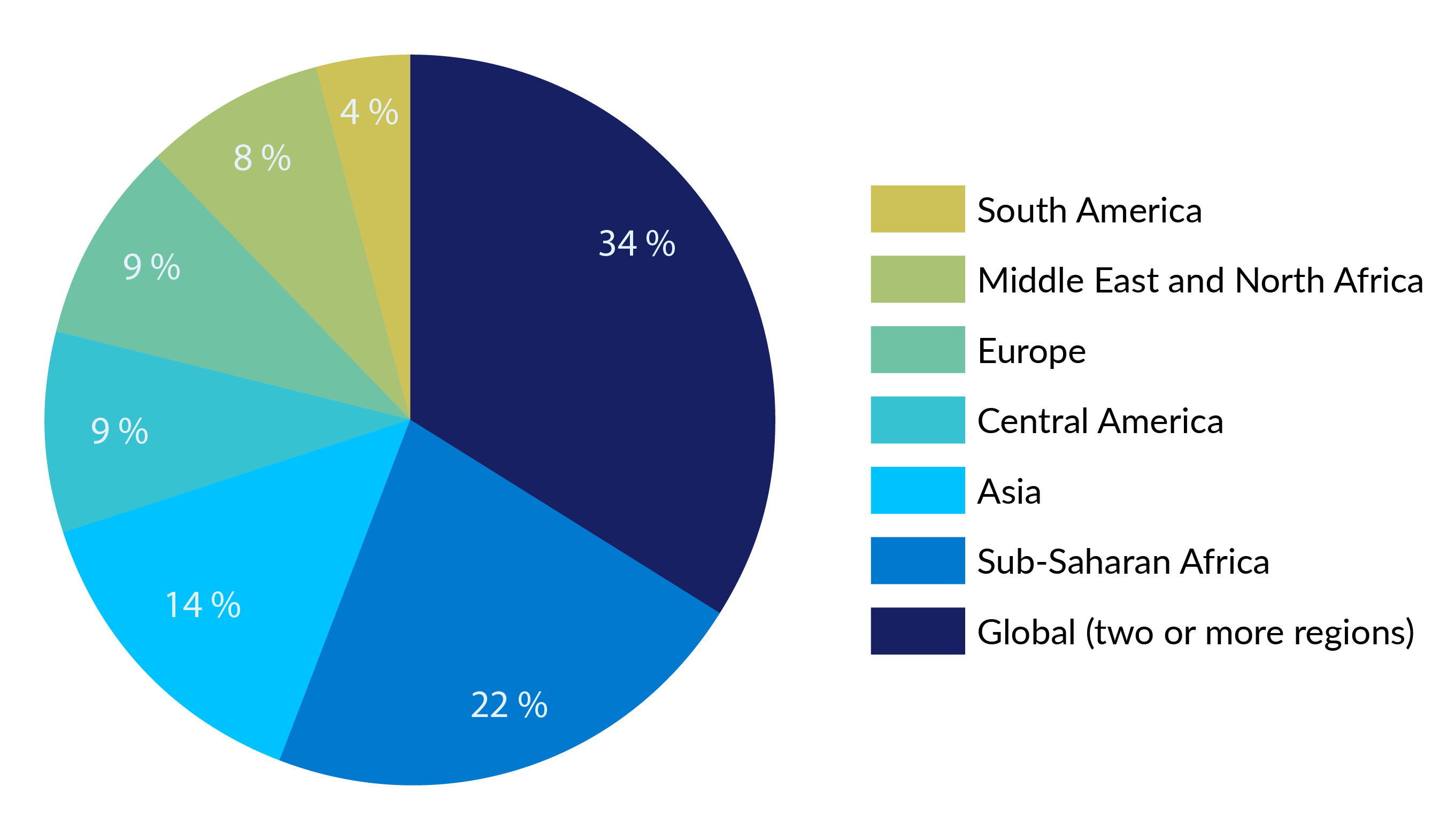

From the compilation of the dataset, it is possible to establish the geographic distribution of published evaluation evidence. Figure 3 shows the breakdown of programmes by region, while Figure 4 shows the number of evaluation reports per country globally.

Figure 3: Regional coverage of programmes

Figure 4: Country evaluation coverage

Sub-Saharan Africa emerges as the region with the highest number of evaluations. In this region and in others, the evidence is clustered in certain countries. Indonesia (14 evaluations); Ghana (8 evaluations); and Kenya, Mexico, Nigeria and Peru (all 7 evaluations) are the countries where there is the highest volume of evaluation evidence.2e0a9ff52643 This reflects the geographic priorities of the organisations included in the dataset and the extent to which they engage in anti-corruption activities in these jurisdictions. For those looking to draw lessons from the available evaluations, however, it is worth considering that the evidence is weighted towards some key jurisdictions.

4.4. Growth of the evaluation evidence base

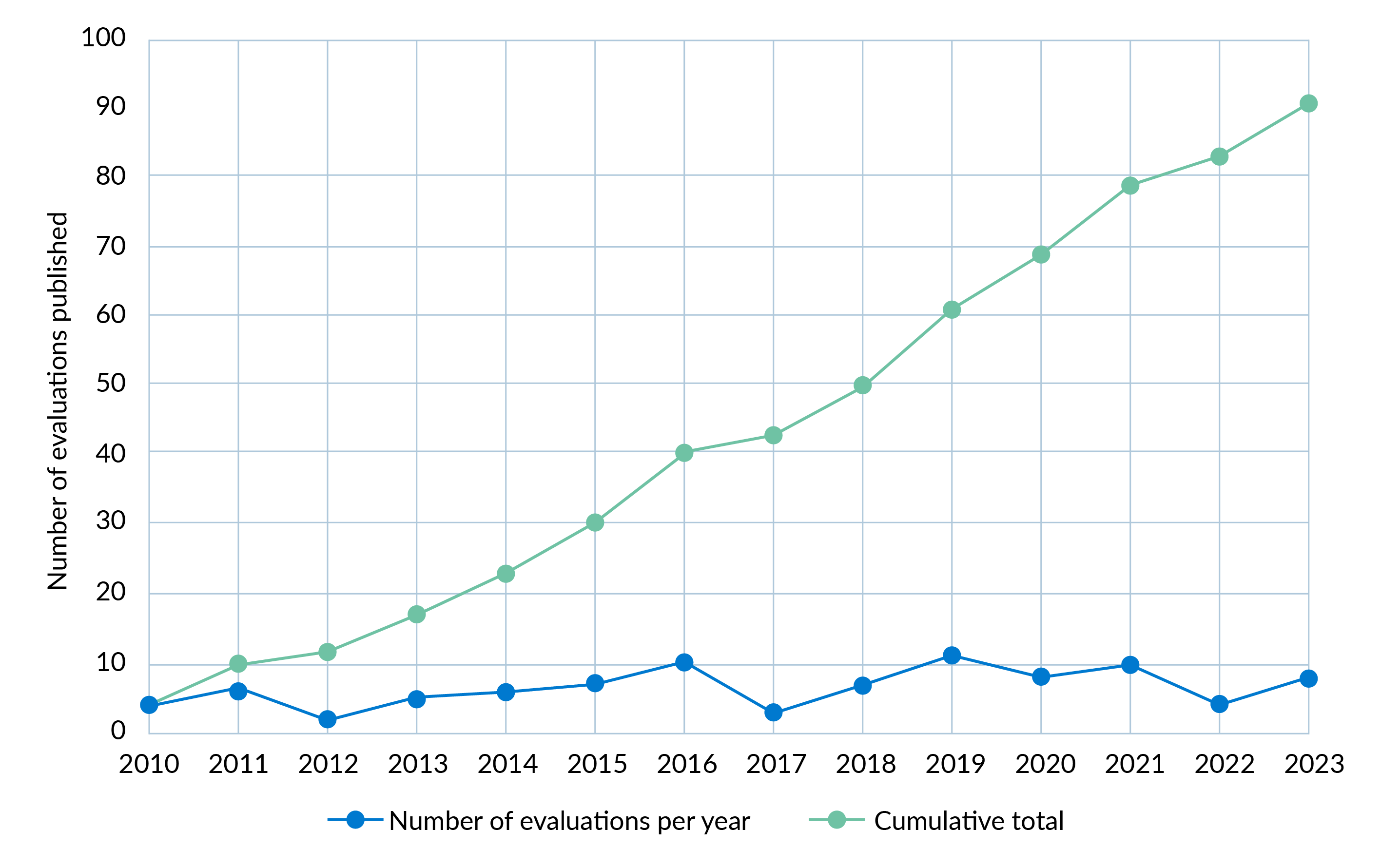

Based on the number of reports published per annum, there has not been a significant increase in the volume of evaluation evidence produced across the anti-corruption field over the last 14 years. Figure 5 shows that the number of evaluation reports published has increased at a fairly constant rate. The years 2019 (11 evaluation reports published) and 2012 (2 evaluation reports) represent the high and low years, with most years close to the mean of 6.5 reports published.

Figure 5: Growth of the evaluation evidence base

The year-to-year numbers are consistent with the level of funding for anti-corruption work, which has remained fairly constant.9dc37fe4e03d It is arguable that this remains a small pool of evaluation evidence given the level of activity in this field over the last two decades.

5. Programme evaluability

Before assessing evaluation quality, we need to examine whether there are factors related to the design and organisation of anti-corruption programmes themselves which affect their evaluability. Problems at this stage could be a root cause of a weak evaluation, while a well-designed programme could lay the groundwork for stronger analysis of effectiveness and impact. The sections below cover ToCs, the availability of baseline and monitoring data, and structural features of programmes.

5.1. Programme Theories of Change

Developed in response to concerns about the inflexibility of the LogFrame tool as a basis for development programming, ToCs are intended to underpin more adaptive work. There are different elements of good practice to ToCs – they should be built on sound analysis of the context; articulate a hypothesised route by which an intervention might contribute to change; outline key assumptions and preconditions for success; and identify risks to achieving objectives.ea3e3863eecc ToCs should further be continually revisited; as surmised by Vogel, a ToC is as ‘much as a process as a product’.5400df115e01

For only 17 of the programmes reviewed (20% of the dataset) was there clear evidence of a ToC in place prior to evaluation. In looking for a ToC, the review was not prescriptive about the presentation or terminology. It simply sought a clear description of the intervention logics. Of course, every intervention has an underlying theory and logic behind it. What this finding indicates is that many anti-corruption programmes do not appear to be making these logics explicit and therefore open to scrutiny through evaluation. For those 17 programmes with a ToC, only one is rated as strong (Evaluation 18, 2021) – that is, it clearly incorporates contextual analysis as well as key assumptions and risks. In the other cases, shortcomings with the ToC presented mean they are rated fair. Table 2 shows the common weaknesses with these ToCs against the different elements of good practice noted above.

Table 2: Analysis of Theories of Change

|

Element of good practice |

Percentage of Theories of Change incorporating this practice |

|

Conceptual clarity |

12% |

|

Disaggregation of corruption forms |

18% |

|

Clear evidence the Theory of Change has been developed from contextual analysis |

35% |

|

Assumptions are clearly set out alongside the Theory of Change |

47% |

|

Risks are clearly set out alongside the Theory of Change |

23% |

Incorporation of contextual analysis is a clear area of weakness. There is ample guidance available on how to use approaches like political economy analysis and systems thinking to identify problems and formulate solutions.8b6b701bfe82 In practice, from the published evaluations reviewed, there is rarely evidence of contextual analysis having been conducted at the outset of the programme. Where ToCs do reference contextual factors, the information presented tends to be surface level as opposed to detailed and problem specific analysis. As emphasised in Section 3.2, it is possible some programmes had this form of analysis available behind closed doors but this was not incorporated into the evaluation.

Only in one evaluation was there clear evidence of a ToC being revised in the course of the programme (Evaluation 2, 2021). This suggests they are not being used as flexibly as proponents of the ToC approach would advocate. Relatedly, and despite the inherent uncertainties around anti-corruption programming, across all the programmes reviewed the expected outcomes were fixed. There were no examples of programmes with a range of potential outcomes depending on circumstances, for instance. It was also rare for programmes to change their goals in response to unforeseen events. Therefore, even while there has been gradual uptake of the ToC approach, on paper many programmes do not appear to have abandoned notions of control and predictability associated with other programme management tools like the LogFrame.

5.2. Time frames and budgets for evaluations

Across the whole dataset, the median time frame afforded to conduct the evaluation was three months.ffdb7f919329 There were a small number of outliers: one large evaluation covering the anti-corruption portfolios of six development agencies was carried out over 24 months (Evaluation 11, 2011). The evaluators of a further four programmes had ten months or longer to complete their work (Evaluation 12, 2020; Evaluation 54, 2016; Evaluation 71, 2023; Evaluation 86, 2011). These examples aside, the time frame for the vast majority of evaluations was close to the three-month median.

It is questionable whether three months is an adequate time frame to prepare a high-quality evaluation. Alongside this data point, consider also that external evaluators completed all but three of the evaluations reviewed (Evaluation 54, 2016; Evaluation 90, 2011; Evaluation 91, 2013). Three months is a short time frame for an external evaluation team most likely unfamiliar with the activities to first understand a complex programme, and second, to make evaluative judgements on that programme. This challenge is compounded if, as discussed below, baseline and monitoring data is not available or of poor quality. In addition to limiting what types of approaches and research designs the evaluators can propose, another likely consequence of short time frames is that the evaluation team’s dependency on internal programme staff for contacts and information is increased. Short time frames similarly make it harder to reach individuals for interview who are working at organisations which have not been direct recipients of programme funding. Together this may diminish the weight given to independent perspectives.

For the majority of cases, all evaluative work started at the end – or near the end – of a programme. Only 12% of the programmes reviewed had a published midterm evaluation. These reports have the potential to support learning and adaptation if they take place at a point when the findings can still influence the direction of a programme. The dataset does not include any examples of evaluators providing ongoing support for learning. One approach of this type is known as ‘developmental evaluation’, as conceived by Patton.b79297334bde Some organisations working in the broader governance sector have trialled, or are considering adopting, this way of working.b5da88b452f2 This is not a model which has to date gained any significant traction with organisations undertaking anti-corruption programming. This again has important implications. There is a logic to an end-of-programme evaluation if the primary purpose is to assess results for accountability purposes. However, the timing limits the potential for an organisation to directly apply lessons from the evaluation to the programme pursued.

Additionally, budget has a critical bearing on what it is possible for the evaluators to achieve. It is possible this is another constraint on evaluation quality, although sufficient data is not available across organisations to assess this. Twenty-eight evaluations (31% of the dataset) publish evaluation budgets. However, this is heavily weighted towards UN agencies which commissioned 19 of the 28 evaluations. For those evaluations with data available, the average spend on evaluation was 0.99% of the overall programme budget.

5.3. Length and scope of programmes

Some academics argue that it can take decades to observe changes to corruption systems.616dbdb169c9 If a programme only takes place over a short time frame, one perspective might be that programmes do not run for long enough to observe impact. This indeed is a conclusion that evaluators often reach, with some stating that it is too early to make judgements on questions related to impact. The counterargument here is that it is possible to understand contributions towards change, even for shorter programmes, with a broader conceptualisation of impact in anti-corruption work. More tangible changes such as legal, policy, or regulatory reforms; strengthened capacity of institutions; enhanced networks of anti-corruption practitioners; and a reduction in corruption risks are examples of different forms of impactful contributions. These are also more practical goals for guiding activities than a singular objective of reduced corruption.

Across the dataset, the median time frame for a programme evaluated was four years. There were six outliers where an evaluation covered a programme or portfolio of work lasting ten years or more, and eight programmes where the activity lasted for two years or less. A four-year time period should allow for changes to be observed relating to the more tangible forms of impact outlined. Except perhaps in outlier cases for short programmes, the length of anti-corruption programmes is therefore not automatically an impediment to an evaluation providing strong evidence on contribution. However, this depends on how objectives are formulated by the portfolio/programme.

Related to this is the scope of the programmes evaluated. In the dataset, single programmes on average encompassed three of the different intervention types listed in Table 1 whereas evaluations of an organisation’s portfolio of work covered four intervention types. There is a rationale for a multi-pronged approach. There is increasing recognition of the importance of interdependences in anti-corruption work.8575d6f55118 This is the idea that the success of one form of intervention often depends on others. While a high-quality evaluation might yield lessons on how different forms of interventions interact, broad programmes often create challenges for evaluations. Evaluators are usually asked to make evaluative judgements on the whole breadth of a portfolio or programme’s activities rather than investigating aspects in depth (of particular relevance to theory-based evaluations), or in fact to explore interdependencies.

5.4. Programme data collection

It has been established that evaluation is ordinarily conducted by external consultants, takes place at the end of a programme’s lifecycle, and must usually be completed within a short time period. Given these circumstances, the quality of existing monitoring information collected by programme staff is crucial to programme evaluability.

5.4.1. Quantitative indicator design

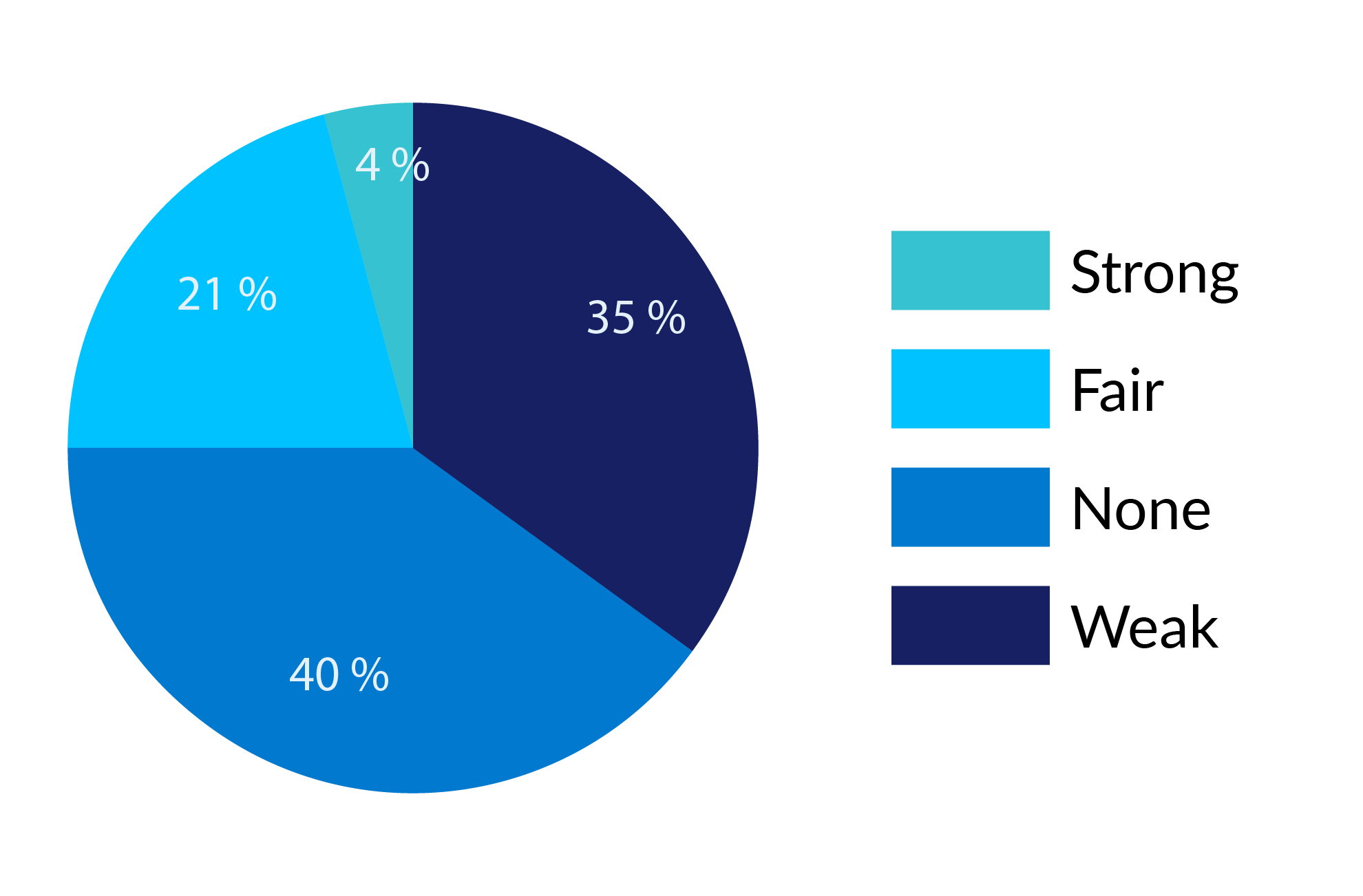

Indicators used in anti-corruption programmes are almost exclusively quantitative in form.9c81605518a1 Across the dataset there is evidence that 60% of the programmes reviewed put in place quantitative indicators to support programme monitoring. Figure 6 shows the ratings of these indicators for all programmes in the dataset.

Figure 6: Indicator design ratings

The most common weakness for those that did use indicators was that these only tracked outputs and not outcomes. The difference between the two can be subtle – are government attendance figures at a training programme a record of activities (outputs) or do they in themselves show engagement and therefore evolving attitudes (an outcome)? – but this is not just semantics. If programmes only track their own activities and not their contribution to external effects, this is a limited form of accountability. The indicators show whether the programme implemented its activities as planned but not what consequences it had.

In other cases, indicators were rated as weak because the measures chosen were disconnected from the programme activities. Most frequently, programmes used a national index like TI’s Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) to track change, which was not within their scope to influence – even if it were a reliable indicator of change.e90571787eae In other cases, the indicators were too vaguely defined. One programme for instance aimed for a ‘5% increase against the baseline in the percentage of people expressing the will to fight corruption’.

Indicators were strongest when linked to discrete forms of intervention. A programme looking to address nepotism in the civil service in Paraguay developed indicators linked to the use of competitive recruitment procedures (Evaluation 79, 2019). One programme working on transnational law enforcement tracked volumes of assets recovered as an indicator of performance (Evaluation 3, 2019). For other forms of intervention which lend themselves well to indicator development, such as procurement reform and support to audit authorities, programmes nonetheless missed opportunities to set up potentially value ways of following changes.

5.4.2. Availability of monitoring information

This section has thus far examined quantitative indicator design, but are programmes actually collecting monitoring data? The findings indicate there are deficiencies in the operation of monitoring systems across a large proportion of anti-corruption programmes. Sixty-eight per cent of the programmes are rated as weak because the evaluation does not clearly incorporate monitoring data (of a qualitative or quantitative form). Within this there were 26 programmes (29% of the dataset total) which established quantitative indicators, but this did not lead to the monitoring data being used for the evaluation. This suggests it was either not collected or not deemed significant enough to be incorporated into the evaluation. In other evaluations rated fair the monitoring information available was often incomplete, impeding time-series comparison. Similarly, 73% of the programmes seemingly lacked baseline information, understood as either quantitative data points or qualitative description of the situation prior to the programme being implemented. There was consequently not a ready comparison point against which evaluator(s) could analyse any changes which might have taken place.

5.5. Conclusions on programme evaluability

This section has shown that many anti-corruption programmes are set up in a way which makes evaluating them more difficult than it might otherwise be. The theories and intervention logics on which programmes are founded are not usually spelt out in sufficient detail to enable critical independent assessment. There is rarely evidence of contextual analysis being available for evaluators to situate their findings. In addition, there are established organisational operating models which see evaluations typically, although not exclusively, conducted in short time frames and at the end of programme lifecycles when many opportunities for learning have passed. Finally, the majority of programmes are not using indicators to support comparison of the situation before and after a programme. At the point of evaluation, relevant data on change is often not available for interpretation.

The implication is that, in many cases, programmes are poorly positioned to optimise an evaluation process. Evaluation resources will more likely be pulled towards retrospective sense-making and data collection as opposed to bringing fresh perspective to existing analysis. These are not insurmountable issues for evaluations but it is a poor starting point.

6. Evaluation quality

6.1. Evaluation design

If evaluation is to provide useful contributions on questions relating to impact and effectiveness, it must grapple with questions around research design. There is an important distinction to be made between research design and methods. Yin neatly surmises that design is logical whereas method is logistical.3b8a41225e32 In other words, research design involves choosing an appropriate framework for addressing a set of evaluation questions. Methods is a description of the processes followed by the evaluators to collect relevant information within this framework.

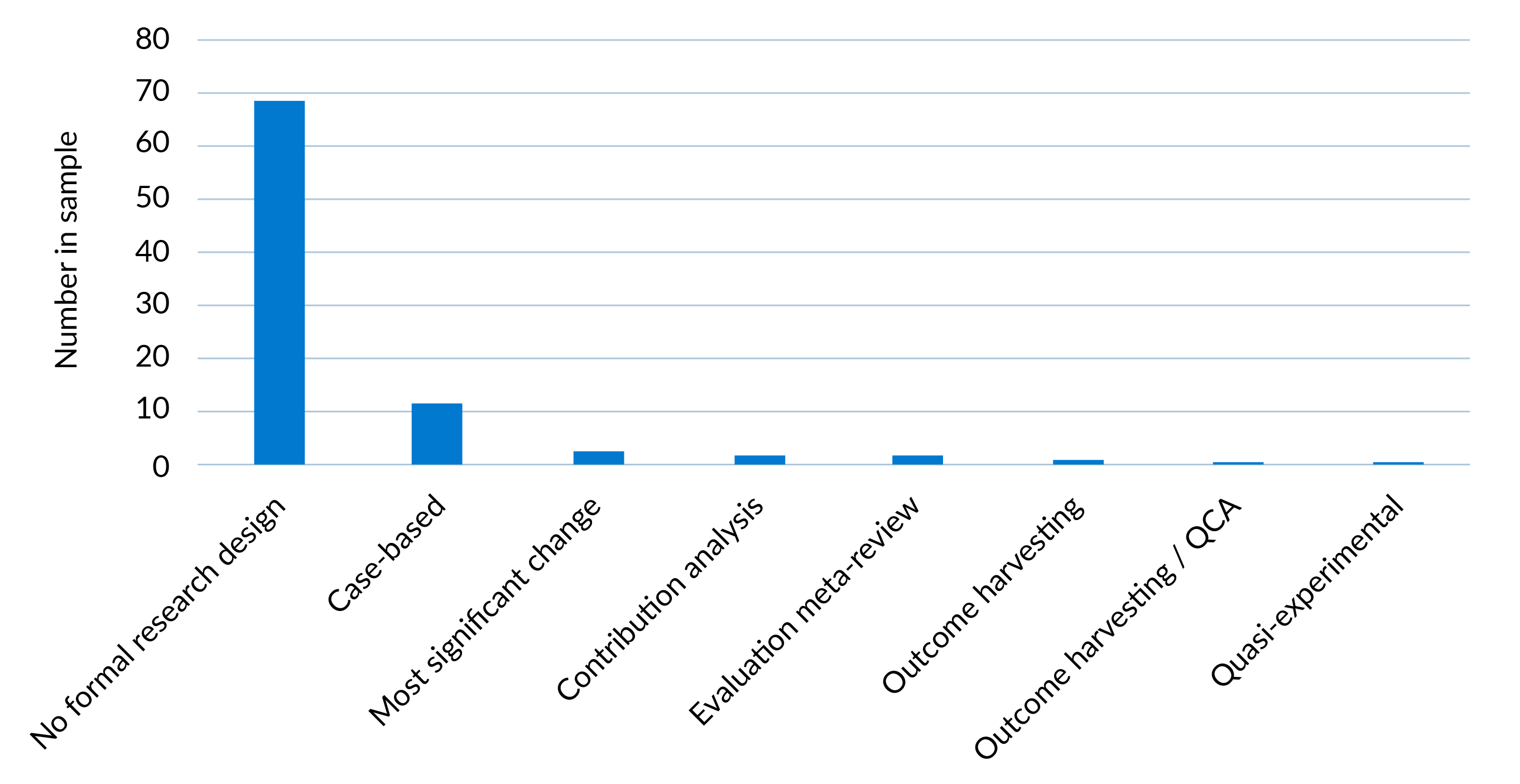

Figure 7: Evaluation research designs

The analysis shows that 76% of the evaluations included in the dataset do not have a formal research design.c82114c1e09b In these evaluations, the OECD-DAC criteria in effect provide a substitute framework. The evaluators organise the data they have collected through interviews, surveys etc. against the criteria selected for coverage in the evaluation. This is problematic as OECD-DAC criteria are in essence lines of inquiry, or a set of questions to consider, rather than a research design in and of themselves. While the evaluation might nominally refer to a research design, this is usually a description of methods.

One response to this finding might be that it cannot be expected that final programme evaluations, which make up the bulk of the dataset, would have a formal design. Some argue this is the type of structure required only for larger and more comprehensive studies of impact. A counterargument is that final programme evaluations are consistently expected to answer challenging questions around effectiveness and impact which can only be rigorously addressed through a structured design. There are also final programme evaluations in the dataset which follow a research design, demonstrating this is possible.

Some evaluation experts believe experimental evaluation designs (ie designs involving some form of randomisation) produce the strongest evidence on impact.bd64a3d5a0e2 This is a perspective which is increasingly challenged.61354c27b65d For anti-corruption interventions particularly, there are questions around the feasibility of these designs as well as whether they necessarily produce the types of evidence the field needs. Assessing impact should not only be about establishing outcomes, but also exploring how and why these outcomes were achieved, and if the lessons could be applied elsewhere (see ‘Alternative perspectives on evaluation’).

The review identified only one example of an evaluation based on a quasi-experimental design (Evaluation 80, 2018). This evaluation assessed the impact of a social mobilisation campaign on corruption ahead of elections in Peru. The funder had supported the organisation of anti-corruption fairs in 40 randomly selected localities in Peru. Using citizen surveys, the evaluators then estimated the effects of the programme on attitudes to corruption by comparing districts where fairs had and had not been held. The findings were stark: the evaluation found no effect of the fairs on citizen attitudes. This is a valuable piece of evidence to consider alongside recent academic research questioning assumptions around awareness raising on corruption.70bf1ac4d7e0 The difficulties in establishing comparison groups (beneficiary groups of anti-corruption work can often be hard to define), the structure of programmes, and the resources needed may be factors explaining the limited use of this type of design.

A qualitative case-based design was the most common research design in the dataset. In these examples the evaluators selected a subset of a programme or portfolio for closer analysis. There were significant variations, however, on the level of detail in cases. A strong example is Evaluation 7 (2022), a cross-cutting portfolio review of EU support to anti-corruption in partner countries. It used 12 country and regional case studies, each beginning with contextual analysis, to highlight learnings on good practice in different contexts. In some other evaluations, however, case studies were disconnected from the main narrative, and it was not clear how they informed the evaluation conclusions.

There has been limited application to date of evaluation designs based on generative logic, such as contribution analysis, qualitative comparative analysis (QCA), outcome harvesting, and process tracing (Aston et al., 2022 (see ‘Alternative perspectives on evaluation’). Evaluation 9 (2019) shows that these designs can yield valuable evidence and learning. For this evaluation of a programme aiming to strengthen accountability of local government bodies in Uganda, the evaluators combined outcome harvesting and QCA. The evaluators followed a participatory approach to engage stakeholders in developing a list of outcomes from the programme at national and local levels. Data on economic, social, and political conditions in local government authorities was then used to establish the contextual factors needed for the programme to make the strongest contributions to local government performance. This in turn informed analysis of the ToC behind the programme.

6.2. Evaluation coverage

One determinant of quality is the coverage of an evaluation, understood here as the types and breadth of questions evaluators are expected to address. Most organisations regularly use the six OECD-DAC criteria when setting evaluation questions (see Section 2). Notwithstanding warnings from the OECD that the criteria should be applied thoughtfully,5c8e242590ae in the majority of cases the evaluation questions follow a template format – they are standardised and not specific to the intervention. In contrast, around a third of the evaluations (31%) are based on adapted questions, even while they might still be organised within the OECD-DAC framework.

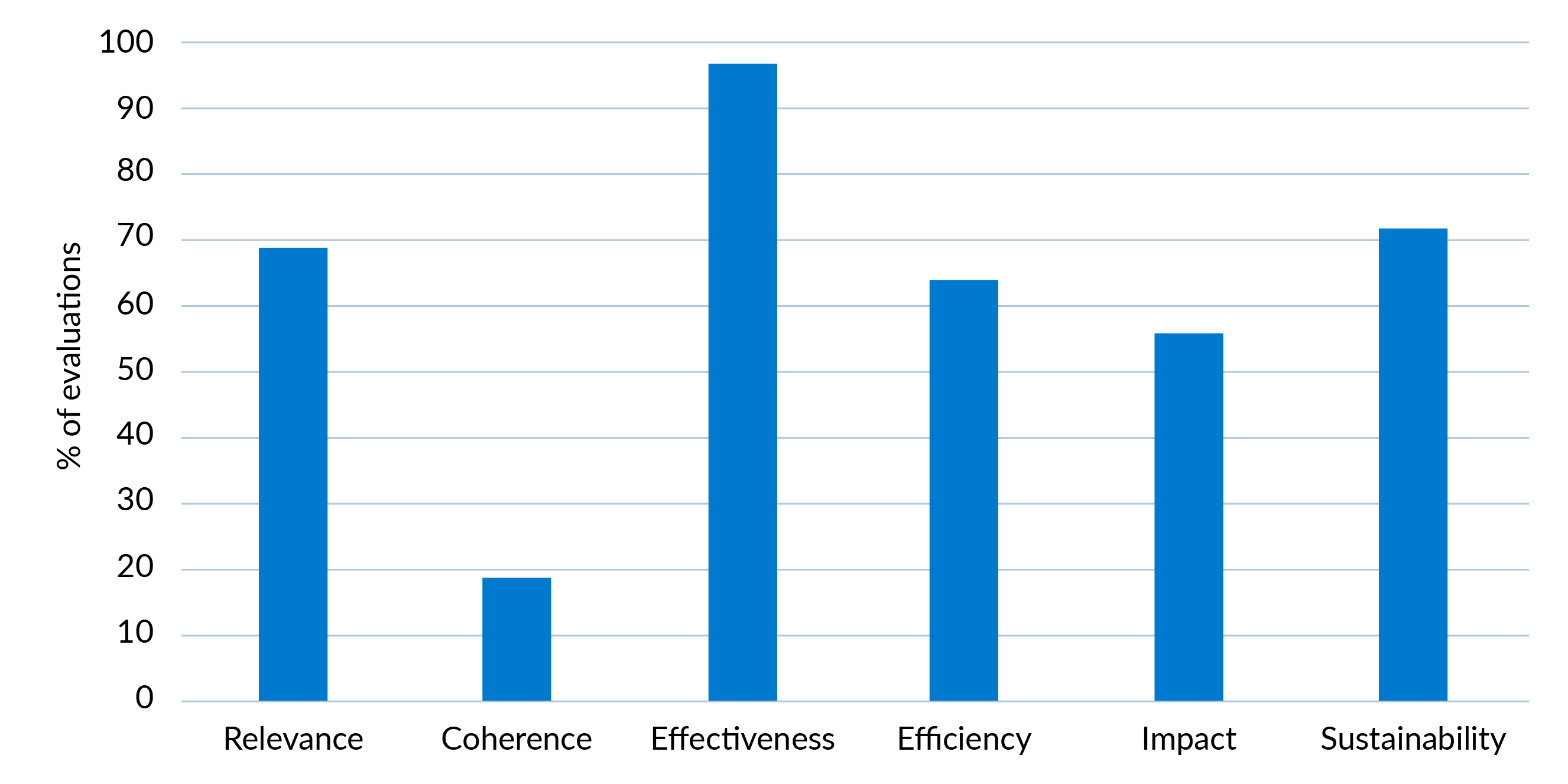

Figure 8: Coverage of the OECD-DAC criteria

Figure 8 shows the percentage of evaluations in the dataset which cover each of the criteria.8437802c06ba Almost all evaluations aim to examine effectiveness and just over half seek to assess impact. The distinction between the two is subtle and there are variations in how evaluators apply the terms in practice. For reference, the OECD definitions of the two criteria are as follows:

- Effectiveness: Is the intervention achieving its objectives? The extent to which the intervention achieved, or is expected to achieve, its objectives and its results, including any differential results across groups (own emphasis).

- Impact: What difference does the intervention make? The extent to which the intervention has generated or is expected to generate significant positive or negative, intended or unintended, higher-level effects (own emphasis).

As the objectives of programmes usually relate to some form of external change, this would mean evaluators would typically need to establish what external outcomes have been achieved to analyse effectiveness. In practice, evaluations struggle to reliably establish external outcomes because of the design issues noted and methodological weaknesses around clarifying information sources (see Section 6.3.2). Discussions of effectiveness can drift towards focussing uniquely on internal aspects of programme management. Furthermore, it is rare for an evaluation to consider differential results across groups.

While evaluators are often asked to assess impact, the majority of evaluations are not designed in a way which would allow them to rigorously do so (see Section 6.1). The consequence is that evaluators often avoid addressing this question in practice. As noted, this again points to some problems around how ‘impact’ is conceptualised in the field (see Section 5.3). If impact is conceived as whether corruption levels are going down – which is difficult to achieve and measure – this does not provide a tangible working goal against which to understand progress. Looking at alternative, more incremental forms of impact would allow evaluations to provide useful commentary on changes to which a programme might have contributed.

On evaluation coverage, one final point to consider is that the unit of analysis for an evaluation is ordinarily the programme. Figure 2 on evaluation types showed that 80% of published evaluations are based around reviews of single programmes. There is a logic to this. It might support accountability in the sense that organisations want to assess results tied to a specific pot of funding. It can often be limiting, however. This type of evaluation does not generally give an evaluator the scope to look beyond the programme to understand the wider dynamics which might be influencing changes, and thereby strengthen the analysis of the ToC. With one exception (Evaluation 80, 2018), the evaluations reviewed do not use a counterfactual to compare the outcomes from a programme to another setting where no intervention took place.

6.3. Internal validity

The limitations section noted challenges around assessing internal validity (understood as whether the evaluation is a reliable account of an intervention) from a published report only. What it is possible to assess is whether the evaluation findings are grounded in a clear description of the context and if this appears credible to an outsider. The review can also judge whether evaluators are transparent about their methods for collecting data and if there has been a genuine attempt to triangulate findings from different sources.

6.3.1. Contextual analysis

Section 5.1 established that for the majority of programmes, there is not clear evidence that they were premised on thorough contextual analysis. While it is preferable to build from an existing problem diagnosis, the absence of this information does not preclude evaluators from conducting their own analysis. The review demonstrates that this is an area where evaluation practice is generally weak. Just over half of the evaluations did not present any contextual analysis (weak rating). For another third, rated fair, the analysis was typically short, high-level and not necessarily linked to the evaluation findings.

In the strongest evaluations, the contextual analysis focussed on the immediate environment in which an intervention unfolded and was used to help explain the findings. One example is an evaluation of an anti-corruption programme seeking to improve financial management at government institutions in Nicaragua (Evaluation 87, 2011). The evaluation describes how political paralysis in the country in the mid-2000s meant that many of the planned activities could not get off the ground, and indeed this could have been anticipated. In general, case-based evaluation designs also allowed for more relevant contextual analysis to be incorporated. A large multi-donor portfolio evaluation began its case studies with analysis of corruption drivers and recent cases (Evaluation 11, 2011), thereby situating the rationale for the interventions. This depth of analysis was rare.

6.3.2. Methodological transparency

The transparency of evaluation approaches is an area where standards are stronger. Only 8% of the evaluations failed to include any detail on their methodological approach. Existing evaluation research in the corruption field is largely qualitative. While 40% of the evaluations stated that they applied mixed methods, the balance tended to be weighted towards qualitative summaries of document reviews as well as interview and focus group data. When evaluations incorporated a quantitative element – such as a stakeholder survey or a cross-national index – this was often, although not always, peripheral to the main analysis. There were also rarely attempts to triangulate findings from qualitative and quantitative sources of information.

Sixty-nine per cent of the evaluations cited limitations to their research. This demonstrates that this is a broadly established convention, even while the level of detail varied significantly. The most frequent limitations related to the structural aspects of programmes discussed in Sections 5.2 and 5.3. Evaluators most often expressed concerns that they lacked sufficient time for research as well as baseline and monitoring data. To be rated as strong, evaluations needed to provide potential mitigants and/or discuss the implications of the limitations for their research. This is important to validity but only 20% of evaluations took this step.

To have confidence in the findings, it is additionally important to see that evaluators have drawn on diverse sources of information, including documentary evidence, data, and individuals external to the programme. Evaluations are generally transparent about their information sources and in 74% of cases, there is at least some evidence that the evaluators consulted external information sources. On the other hand, there is a widespread problem with the attribution of information. Half of the evaluations do not clarify the sources of evidence for the conclusions they draw, such as by specifying a particular document or interview reference (anonymised if required) for key findings. Only 11% of the evaluations consistently provide sourcing. Some of these helpfully indicate the strength of evidence supporting a given point.

On attribution of information then, evaluations are much less transparent. Rather than weighing up the strength of evidence to support findings, it is much more common for an evaluation to consist of a singular narrative summary of the evaluator’s perspective. It is striking that evaluator narratives rarely acknowledge conflicting views on an issue or uncertainties around a conclusion, even while this should be expected for contentious interventions like anti-corruption programmes. Although it is part of the task of an evaluator to make sense of complexity, this often appears to be at the expense of acknowledging competing perspectives or alternative explanations. Lack of attribution allows more scope for an evaluator’s cognitive biases to have a strong bearing on the evaluation findings.

6.4. Assessment of programme Theories of Change

Evaluation is, in principle, an opportunity to critically re-examine a ToC but it has been established that the majority of programmes lack this type of theory at the outset (see Section 5.1). Evaluators might still attempt to reconstruct the ToC post-facto as a basis for their review and there are 14 evaluations in the dataset where this is the case. For 68% of evaluations rated weak, there is neither an existing ToC nor do the evaluators offer their own interpretation.

Only for 12% of evaluations rated strong are existing ToCs examined and refinements suggested if required. An example of an existing ToC further refined by evaluators is Evaluation 18. This was prepared for TI’s Accountable Mining Programme and illustrates the complexity involved in developing hypotheses around how anti-corruption interventions might work. Core assumptions are incorporated into the ToC and the change markers provide helpful indicators of incremental change.e55581c7e513

In many other cases where evaluators recreated a programme ToC, there were often still weaknesses with the theory presented. Similar to the original programme ToCs analysed in Section 5.1, some reconstructed ToCs are not clearly grounded in contextual analysis (6 of the 14 reconstructed ToCs); fail to disaggregate corruption forms (13 of 14); and do not incorporate assumptions (7 of 14) or risks (13 of 14). This may stem from misunderstanding around ToC, or simply that evaluators were not given the time or resources to develop the ToC – a task which in any case is challenging to do retrospectively.

In assessing ToCs, it is also instructive to establish whether evaluators looked beyond what the programme anticipated at the point of design to consider unintended consequences. Even though looking for unintended consequences often forms part of an evaluation scope, in practice only 15% of the evaluations in the dataset presented findings on this point. More often this question went unanswered. If evaluators do not explore this question, nor critically examine programme logics, the implication is that evaluators are only looking for the forms of change a programme expects to see.

6.5. Measuring change

It is of interest to observe whether evaluators are making use of the increasing number of corruption measurement tools available. Of the evaluations in the dataset, 62% either do not use any form of quantitative measurement or the measures used have significant flaws for understanding change. A distinction between the two is made in the ratings because it is not always feasible for an evaluator to quantitatively measure change.

Table 3 lists various direct and indirect approaches to measuring corruption and the number of evaluations of the 91 in the dataset which use each measure.6318a1f1ccf4 These are measures only of prospective outcomes from programmes as opposed to counts of outputs.

Table 3: Types of measurement used in evaluations

|

Type of measurement |

Description |

Number of |

|

Bespoke opinion surveys |

A survey constructed by the evaluator to collect views on the programme, usually from project beneficiaries |

37 |

|

Cross-national country indices |

An existing country index, such TI’s Corruption Perceptions Index or Global Corruption Barometer, or the Worldwide Governance Indicators |

22 |

|

Whistleblower and/or complaints data |

Numbers of reports received through whistleblower/ complaints channels and, in more limited number of examples, related data on outcomes from those reports |

18 |

|

Law enforcement data |

Case numbers on corruption investigations, prosecutions, and convictions, with different levels of granularity |

13 |

|

Legal and/or policy changes |

Number of changes to laws and/or policies targeted by the intervention |

8 |

|

Project rankings |

Bespoke ratings of projects developed internal to the organisation, used most commonly for large portfolio evaluations |

6 |

|

Media/ internet analytics |

Levels of publicity around an intervention, or engagement with content produced by a programme |

5 |

|

Procurement |

Specific data related to integrity in procurement processes |

3 |

|

Transparency |

A proxy measure on levels of disclosure by public organisations and/or private firms |

2 |

|

Corruption risk |

A proxy measure of levels of corruption risk related to an institution or activity (excluding procurement) |

1 |

|

Institutional defences against corruption |

A proxy measure of the capacity of institutions to prevent corruption |

1 |

|

Audit |

Audit data used as an indication of corruption or, alternatively, higher integrity in public spending |

0 |

One clear conclusion from the findings presented is that evaluations are not putting to use many good options for measuring change. Despite academic interest in different forms of proxy indicators – such as measures of corruption risk and institutional resilience to corruption – they are not used in evaluation, a practice area where there is high potential for application.

Looking more closely at how measurement is undertaken, there are widespread weaknesses which result in only 8% of evaluations being rated strong on this criterion. One common issue is that while an evaluation might contain isolated references to data, longitudinal trends are not presented to assess changes over time. Furthermore, the data is typically not triangulated with qualitative sources and therefore is rarely central to the main conclusions presented. In addition, the popularity of cross-national indices again confirms problems with choices around measures. Except perhaps for the large portfolio evaluations in the dataset, these indices are not in isolation an appropriate measure for understanding change at the level at which most anti-corruption programmes operate.

Bespoke opinion surveys commissioned for the evaluation are the most frequent means of measurement. Most commonly, evaluators surveyed stakeholders – usually partners of the programme – on their opinions of a project. These surveys have value as a programme management tool but have significant limitations for measuring outcomes. As the respondents are almost always insiders or direct beneficiaries, they are often conflicted and do not provide an independent perspective. The majority of the surveys are also small N and suffer from low response rates. There are only two examples in the dataset of evaluations which used large N surveys where there was clear evidence of attempts to capture perspectives from outside of the direct programme participants (Evaluation 80, 2018; Evaluation 83, 2014). Most opinion surveys also lack a baseline. To overcome this issue, respondents are asked how they believe a situation compares to a fixed moment in the past. Relying on memory in this way compounds potential bias and reduces reliability.

Law enforcement-led anti-corruption interventions are conducive to measurement. Schütte, Camilo Ceballos, and Dávid-Barrett have suggested disaggregated indicators on the capacity and performance of anti-corruption agencies (ACAs) which cover different stages of the law enforcement chain.6831bbafe5f6 There is also a potential wealth of data to be gathered for interventions related to justice sector reforms. Despite these types of approaches being some of the most frequently evaluated interventions, the data presented is rarely specific enough to assess progress. One exception is an evaluation of a justice sector reform programme in Bosnia and Herzegovina (Evaluation 77, 2019). The evaluation is grounded in detailed longitudinal data on prosecutions for corruption which is disaggregated by different phases of the enforcement chain. Data for different sub-regions is also presented. While data availability is often a constraint, there are several other evaluations of this type of programme where there is no apparent attempt to measure outcomes.

6.6. Localisation and participation in evaluation

There have been long-standing concerns in the international development sector about inadequate localisation, understood as the devolution of power and resources to the communities where development interventions take place. Even though organisations place ever greater rhetorical emphasis on these issues, this is an area where they have struggled to implement commitments.782ce22116b5

Localisation raises some important questions for M&E. If evaluation is the domain where final judgements on interventions are made, who is reaching those conclusions? Are evaluators local? If not, do external evaluators seek out local perspectives? What filters and preconceptions affect evaluator judgements? And how are resources distributed among the actors involved in evaluation at different levels?

Localisation receives wide support as a broad normative goal in development. There are also growing calls to recognise and address inequities in the representation of voices from the Global South in evaluation processes.6cdfa9773bca Outsiders may also bring valuable alternative perspectives and different forms of expertise. Some commentators have begun to think about the implications of localisation for M&E but this is a nascent debate.ed236ff20ba7

There are limits to what a review of evaluation reports alone can contribute on these questions. Career profiles for evaluation team members are usually included in reports. Across the dataset, 61% of applicable evaluations include at least one national of the country where the intervention took place.26d7350bda4b Across the whole dataset there is not, however, sufficient information available on the roles fulfilled by individuals. The evaluation report itself reveals little about the power dynamics around the evaluation process and the influence of different team members. The regional origins of an evaluator might also be important.

One additional data point is to look at is the identity of the contracting party, a crude indicator of where the funds for an evaluation could be expected to flow. In only a third of the applicable evaluations is the contract held by either a national firm or a group of individuals which includes a national. For the majority the contract is held by a firm located outside of the country, ordinarily a firm from the commissioning organisation’s home country or another high-income country. Although this is difficult to prove, this suggests that the bulk of funding for these evaluations typically remains with Western firms, even though the geographic spread of the work is global. There may nonetheless be trade-offs to consider around more diversified contracting models. Development agencies typically use framework agreements with core providers as a quicker means of commissioning evaluations.

Evaluators often state that they use participatory evaluation methods but it can be difficult to assess the extent of participation in practice. In its fullest meaning, participatory evaluation entails opening up the design of an evaluation, and the process of interpreting and using findings, to the intended beneficiaries of a programme.6df4fb4213a8 There is no clear evidence that any of the evaluations in the dataset opened up the design process to beneficiaries. The norm is for control of the scope of the evaluation to remain with the commissioning organisation, although in some instances this may involve external consultation.

In the data collection phase, some methods may lend themselves to stronger participation. Thirty-seven per cent of all evaluations in the dataset used focus groups, for instance. The problems discussed that related to attribution of information (see Section 6.3.2) nonetheless make it hard to determine what weight evaluators give to the evidence gathered. There are also limited examples of participation extending to involving beneficiaries in shaping the conclusions of an evaluation. Evaluation 9 (2019) applying an outcome harvesting design and Evaluations 21 and 23 (2020), both internal learning reviews commissioned by TI, are perhaps exceptions. Finally, there are around 20 evaluations where there is some evidence of intent by evaluators to engage stakeholders post-completion of an evaluation, such as through workshops on findings. This does not appear to be a common practice and again, it is often not clear whether the focus is on programme beneficiaries as opposed to staff internal to the commissioning organisation.

Language is likely to be an additional barrier to engaging local beneficiaries with evaluation findings. The overwhelming majority of evaluation research appears to be published in English, even where this is not an official national language.9cf20cd26359

6.7. Gender and intersectionality

This section explores the extent to which evaluations integrate gender and intersectionality considerations into different stages of the evaluation process. This includes consideration in:b4b96a528cca

- Evaluation design: Questions related to gender and intersectionality are incorporated into the scope and the evaluation is designed in a way which allows the evaluator(s) to explore how these factors influence outcomes from programmes.

- Research methods: Research methods ensure safe and full participation by any individual, regardless of their gender identity, race, class, sexuality, or nationality.

- Analysis: The evaluators assess the responsiveness of the programme to gender and intersectionality. This involves exploration of how gender and intersectionality affect outcomes from a programme. These outcomes, for instance, might be experienced differently by individuals with different gender identities.

There are seven evaluations in the dataset which are fully responsive to these issues. In a further 22 evaluations there is some acknowledgement of gender and intersectionality, but this does not appear to have been a core element of the evaluation process. Most commonly, the scope includes questions related to gender, and interviewee or survey data is disaggregated by gender, but the evaluators do not explore these issues in any depth. It is much rarer for evaluations to analysis the effects that gender and intersectionality might have on outcomes, including differentiated experiences of a programme. This lack of attention to gender dynamics is consistent with some of the issues noted previously (see Section 6.3.2). Evaluators often do not spend time analysing differences between perspectives on a programme.

Where an evaluation does cover these issues, the focus tends to be on programme management. The evaluators assess whether the programme integrated gender and intersectionality (often referred to as inclusion) into its work as opposed to independently attempting to establish the differentiated effects of these activities. A 2023 evaluation of a public financial management programme in Cambodia is a detailed example of a review of gender responsiveness in programme management. It considers the balance of beneficiaries for each of the programme components, as well as whether the design of programme was sensitive to inclusion (Evaluation 8, 2023).

6.8. Potential for direct use

A review of public reports cannot tell us too much about the utilisation of evaluation research, a key concern in evaluation.67114cc3b900 There are nonetheless aspects of reports which could affect the likelihood of findings being used, as captured in Table 4.

Table 4: Ratings on the potential for instrumental utilisation

|

Rating |

Clarity of presentation |

Framing of recommendations |

Follow-up to evaluation |

|

Weak |

14% |

33% |

67% |

|

Fair |

66% |

59% |

19% |

|

Strong |

20% |

8% |

14% |

A large majority of evaluation reports are presented and organised in such a way that a reader can easily digest the main messages (66% rated fair above). Evaluations were rated strong when they had certain notable features, such as using figures, graphics, or text boxes to engage a reader. A small percentage were rated as weak because of clear presentational issues, such as poor drafting, structuring, and major repetition of information.

Across the dataset, evaluators generally frame recommendations in a way which would support their uptake.a27bb8766723 A third of reports are rated as weak on this indicator on the grounds that the recommendations appeared vague and unactionable. In other evaluations the recommendations appeared sufficiently detailed to be actionable. To be rated strong, recommended actions needed to designate an actor responsible, such as a particular individual or organisation, and a time frame for fulfilment. This was much less common but without allocation of responsibilities, the likelihood that recommendations are ignored increases.

Based on the information available, there is evidence that only a third of evaluations had a follow-up mechanism in place. This usually takes the form of a management response to the report findings and/or recommendations. These responses vary in terms of the detail provided and the extent to which management appear to have engaged with the findings. Only 14% of evaluations were rated as strong on this indicator. In these cases, management responded to recommendations by giving a specific plan of action. The UNDP is an example of good practice, in that management commitments are made available online through its Evaluation Resource Centre.f0bb506abe1e Further research is necessary, however, to understand how these mechanisms function in practice.

Whether a report is available in different languages can also affect use. As noted in Section 6.6., the limited availability of evaluation research in local languages is likely to constrain use by intended beneficiaries of programmes.

6.9. Wider application of lessons

Looking beyond immediate use in the programme, to what extent do these evaluations contain evidence and lessons which might be valuable to consider in other situations? Do they add to the knowledge base in the field around how anti-corruption programmes work?

A principal challenge here is that the potential for wider application is largely contingent on programme and evaluation design. ToCs which in essence are ‘propositions about what interventions may work best under what conditions, or in which sequence’ are a potential mechanism for building understanding on anti-corruption effectiveness and impact across different settings.57c78c3b0897 This review has established, however, that ToCs – where they exist – are typically poorly formulated and then not tested through evaluation (see Sections 5.1 and 6.4). Similarly, structured evaluation designs provide a stronger basis for generating lessons but these are rare (see Section 6.1). Problems identified around the internal validity of some evaluations further diminish reliability and raise doubt as to whether it would even be wise to take lessons elsewhere in some cases.

What is also clear is that there is rarely intent in evaluation to generate findings for wider use. Sixty-nine per cent of evaluations do not consider potential for wider application at all. In around a quarter of evaluations (rated fair) there is some reflection on broader lessons learned but these tend to be general and lack detail. They also typically focus on programme management rather than findings which may explain any outcomes observed.

Evaluation 39 (2015) is an example of a review where there is clear intent to generate broader lessons. It reviews TI’s experience of employing Integrity Pacts, an intervention related to public procurement, in around 20 countries worldwide. The review highlights different factors which could increase the likelihood that a pact will support higher integrity in procurement processes.

More typically it is not part of the scope of the evaluation to consider whether learning from a programme might have wider value, either for the commissioning organisation itself or the broader field. This is likely because evaluation commissioners are not incentivised to generate evidence beyond that related directly to their own work, while evaluators will not look for wider lessons if they are not asked to and/or given sufficient time and budget to do so. This is a missed opportunity to improve engagement in evaluation research as well as for evaluation to contribute to building theory on how interventions can be organised to increase their prospects of success.4a3bab48ec77

7. Conclusion

7.1. Summary of findings on evaluation quality

The findings of this report show that there are widespread weaknesses with the quality of evaluation research currently available (see Tables 5 and 6). Many anti-corruption programmes are not set up in a way which would facilitate understanding the changes to which they are contributing. With some exceptions, organisations are then not using the moment of evaluation to redress these issues. Evaluations typically focus on different aspects of programme management and are not designed in a way which would allow them to authoritatively assess outcomes. This is despite the latter being intrinsic to understanding effectiveness, something which almost all evaluations have as an aim.

With some exceptions, advancements in corruption measurement and theory have largely not been applied in practice in the domain of evaluation. The majority of evaluations are not complexity-responsive, with many proceeding as though anti-corruption interventions were a simple form of programming with a linear causal chain. New ideas for evaluation designs based on generative logic have rarely been taken up, while evaluations only rarely attempt to base their findings on counterfactual analysis (see Section 6.1). Problems with internal validity identified for some evaluations – in particular, the attribution of information – can further negatively affect confidence in findings.

While there are examples of good practice, more commonly the lack of a structured approach to evaluation design, failure to critically assess programme theory and logic, and the absence of contextual analysis, are major issues which limit the potential value of evaluation research for understanding change related to anti-corruption. This casts significant doubt as to whether evaluations are truly providing learning to guide decision-making, as development organisations state is the aim. Evaluations which are formulaic and insufficiently analytical also represent a questionable form of accountability.

Table 5: Summary of ratings of programme evaluability

|

Category |

Sub-component |

Assessment criteria |

||

|

Weak |

Fair |

Strong |

||

|

Conceptual clarity |

Definition of corruption and related terms |

90% |

6% |

4% |

|

Disaggregation of corruption firms |

95% |

4% |

1% |

|

|

Theory of change |

80% |

19% |

1% |

|

|

Monitoring |

Availability of baseline information |

73% |

17% |

10% |

|

Use of quantitative outcome indicators* |

35% |

20% |

5% |

|

|

Availability of monitoring information |

68% |

26% |

6% |

|

Table 6: Summary of ratings of evaluation quality

|

Category |

Weak |

Fair |

Strong |

|

|

Evaluation coverage |

21% |

45% |

34% |

|

|

Evaluation research design |

70% |

23% |

7% |

|

|

Theory of change |

Assessment |

68% |

24% |

8% |

|

Unexpected outcomes |

85% |

13% |

2% |

|

|

Internal validity |

Contextual analysis |

56% |

32% |

12% |

|

Transparency of methods |

8% |

38% |

54% |

|

|

Diversity of information sources |

26% |

39% |

35% |

|

|

Attribution of information |

50% |

39% |

11% |

|

|

Transparency on limitations |

31% |

49% |

20% |

|

|

Measurement of outcomes* |

20% |

32% |

12% |

|

|

Participation |

Gender and intersectionality |

60% |

32% |

8% |

|

Potential for utilisation |

Clarity of presentation |

14% |

66% |

20% |

|

Framing of recommendations |

33% |

59% |

8% |

|

|

Follow-up to evaluation |

67% |

19% |

14% |

|

|

Transferability of lessons |

69% |

24% |

7% |

|

7.2. Are standards improving?

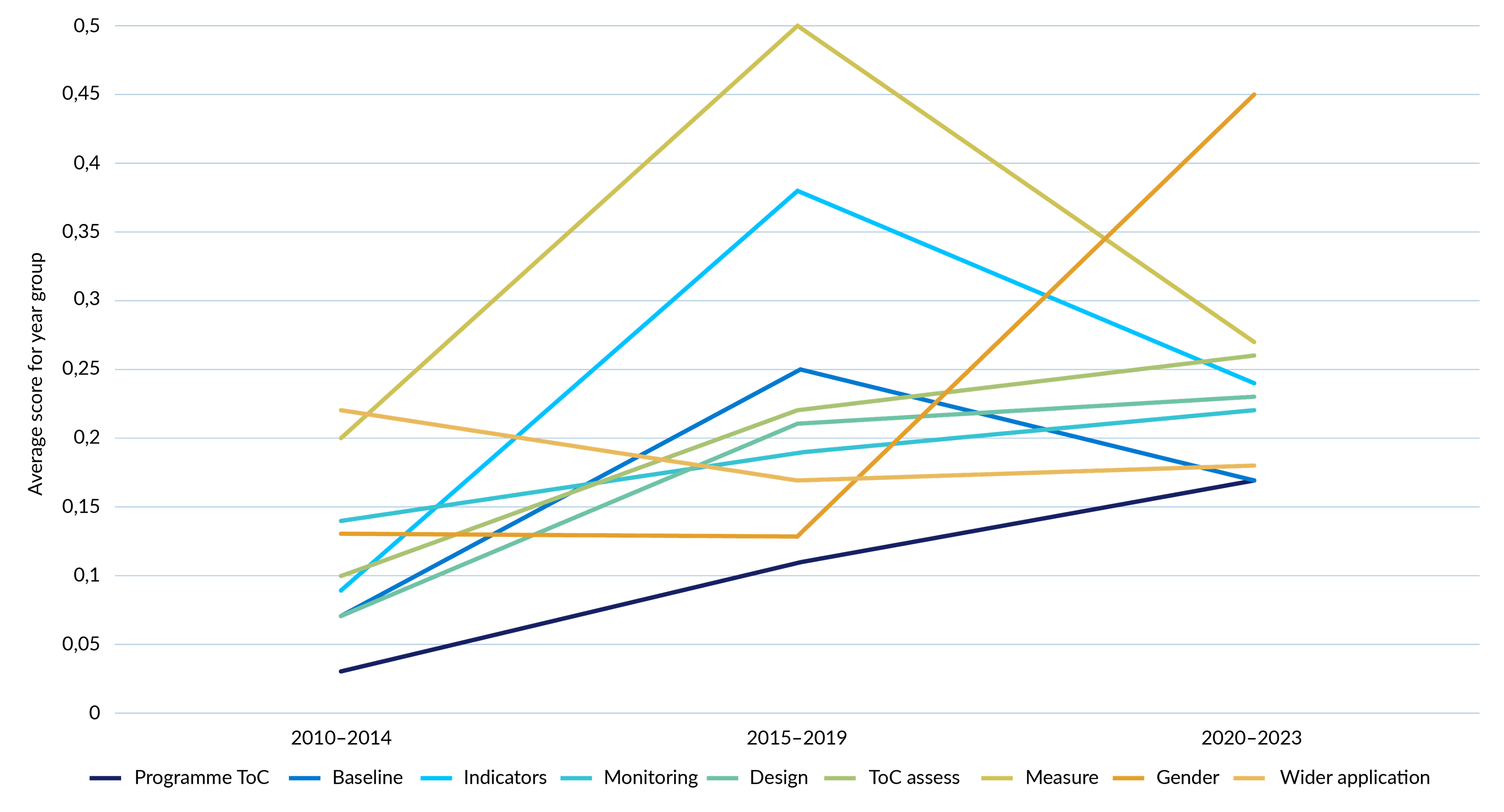

The dataset covers a 14-year timespan (2010–2023). It is therefore instructive to ask what evidence there is that standards are improving. To address this question, the analysis applied a simple scoring system.385c022d194a Figure 9 illustrates how the scores for select indicators have evolved across evaluations grouped into three main time periods.

The analysis shows that there has been only marginal improvement on some indicators of quality and in some areas, standards have stagnated or even regressed. The gradual increase in scores for the programme ToC indicator and the ToC assessment indicator, for instance (see Sections 5.1 and 6.4), indicate that the use of ToC has become more common in programme management and evaluation. The improvement is slight however and even for the latest group of evaluations (2020–2023) the average scores are far below the 0.5 benchmark for a fair score. The strongest upward progression is for the gender and intersectionality indicator, which rises from 0.13 for the 2010–2014 group to 0.45 for the 2020–2023 group. This suggests that gender and intersectionality are increasingly considered in evaluation processes but at the same time there are limitations. Even for the latest group (2020–2023) it is rare to have an evaluation which is fully responsive to the issues (strong rating, 1). This suggests that practitioners increasingly recognise that they need to signal that they are meeting certain norms: evaluations should be based around a ToC and acknowledge gender. In practice though, these approaches lack sophistication. ToCs are not typically constructed or assessed in a way which allows evaluators to interrogate the logics behind a programme; nor is there comprehensive analysis of the influence of gender and intersectionality on outcomes from an intervention.

In other areas standards do not appear to be improving. There is little difference in scores between the 2010–2014 group and the 2020–2023 group of three indicators which reflect on the programme’s set-up for M&E (the availability of baseline data, use of indicators, and collection of monitoring information). While the 2015–2019 group had the strongest scores on the use of quantitative indicators and measurement, this trend was not cemented and followed through to the 2020–2023 group. There is also no evidence that more recent evaluations are paying more attention to questions around the wider application of findings than the earliest published evaluations.