Query

Please address the areas within tax administration with the greatest risk of corrupt behaviour and how could these risks be mitigated. We are particularly interested in examples from Liberia.

Background on corruption in tax administration

Revenue administration includes the collection and management of domestic revenues, such as taxes, custom duties, revenues obtained from state-owned firms and others (Morgner and Chêne 2014; Jenkins 2018:9). Having a well-functioning tax administration is crucial to promote business activities, investment and economic growth as well as to fund various social services, such as healthcare, education, critical infrastructure, and other public goods (Rahman 2009; Akitoby 2018:18).

A poorly operating tax administration, on the other hand, opens a window for collusion between tax officials and taxpayers, which can lead to declining trust between governments, businesses and citizens and consequentially to lower tax morale (Rahman 2009).

Troublingly, the sector of tax administration tends to be perceived as one of the areas most vulnerable to corruption within public administration. For example, Transparency International’s 2017 edition of the Global Corruption Barometerc5559a9ccaec surveyed citizens in 119 countries about how corrupt they thought different institutions and groups in a country were. Overall, 32% of respondents thought that “most” or “all” tax officials were corrupt (Pring 2017:5).

Figure 1. Perceptions of corruption in different institutions and groups in a society. Source: Pring 2017:5.

Question: How many of the following people do you think are involved in corruption, or haven’t you heard enough about them to say? Base: all respondents, excluding missing responses. Chart shows percentage of respondants who answered that either ‘most’ or ‘all’ of them are corrupt.

Key factors that contribute to the vulnerability to corruption include the complexity of legislation, discretionary powers of tax officials, non-transparent hiring and reward mechanisms, low pay for tax officials, a lack of sufficient checks and balances within the tax administration, and a poor enforcement of regulations (Rahman 2009; Morgner and Chêne 2014; McDevitt 2015; Jenkins 2018).

For example, preserving overly complex tax regulation frameworks may stem from incentives of tax officials to protect their rent seeking practices (Bridi 2010; Jenkins 2018). It should also be noted that every area of tax administration is potentially vulnerable to corruption as corruption can influence the registration/removal of taxpayers from national registers, the process of identifying tax-related offences as well as the investigation and prosecution of these offences (Morgner and Chêne 2014; Albisu Ardigo 2014; Jenkins 2018).

Corruption in tax administration damages the economy in various ways, including increasing the size of informal economy and lowering the trust in institutions, among others (Morgner and Chêne 2014). Studies have shown that corruption in advanced and developing countries is negatively associated with tax revenue (Baum et al. 2017). Specifically, studies show that “control of corruption” and “government effectiveness”, based on the World Governance Indicators,a88606199fc3 are positively correlated with tax collection in fragile and conflict affected states, of which Liberia is an example (Akitoby et al. 2020).

Liberia has had some success in increasing its tax revenues since the end of the civil war in 2004 (Akitoby 2018; USAID 2017). Yet, despite this, important corruption risks and challenges remain as Liberia still suffers from a high perception of corruption in tax administration as evidenced by survey data from the African edition of the Global Corruption Barometer.675ed88b5724 In the case of Liberia, when asked how many of the tax officials one thinks are involved in corruption, 68% answered that “most” or “all” are corrupt, which was close to double the regional average of 37% (Pring 2015:35).

This high perception of corruption is substantiated by the reported experiences of bribe-paying in tax administration. The Global Corruption Barometer Africa76d7ea486a90 suggests that of those who have had contact with at least one public service institution, 28% reported paying a bribe in the previous 12 months (Pring 2019). In Liberia, the percentage was much higher at 53% (Pring 2019:14).

This Helpdesk Answer is structured as follows. The next section will outline the approach to assess corruption risks within tax administration, focusing on identifying forms and underlying drivers of corruption. The third section focuses on corruption risks in the tax administration in Liberia. First, it provides background information on Liberia, its political, economic context and tax administration reform. Second, it describes key underlying drivers of corruption risks in tax administration in Liberia. The final subsection focuses on mitigating strategies for countering corruption risks in tax administration by offering general consideration and strategies specific to Liberia.

Key forms and underlying drivers of corruption risks in tax administration

It is important to choose an appropriate corruption risk assessment model before attempting to analyse key corruption risks in tax administration. As Selinšek (2015:10) points out, most risk assessment models include the following steps:

- analysing how corruption manifests in a particular context (i.e., forms of corruption)

- identifying the underlying drivers of this behaviour

- evaluating the efficacy of the existing legislative framework as well as existing policies, institutions, the nature and functioning of oversight and coordination between different institutions within the system

- based on this analysis, developing specific measures to mitigate the most severe corruption risks (see also Jenkins 2018:3).

It is also important to note that corruption risks in tax administration need to be assessed by looking at relationships between different institutions, formal as well as informal (Jenkins 2018:6). Interviews with experts in Liberia conducted for this Helpdesk Answer likewise stressed the need to understand how corruption within the tax administration is embedded in a broader institutional context, including relationships between the Liberian Revenue Authority, parliament and the Ministry of Justice. Consequently, the analysis needs to be attentive to networks of relations between relevant institutions and authorities to properly address the most critical corruption risks (Jenkins 2018). Evidence from Uganda supports this point, as an excessive focus on the administrative aspects of tax administration reform, while neglecting the role of social norms, is judged to have made the reforms of the Uganda Revenue Authority ineffective (Fjeldstad 2006; Jenkins 2018). Moreover, the attentiveness to informal networks is important as research has documented the presence of neo-patrimonialist networks in sub-Saharan Africa and beyond.

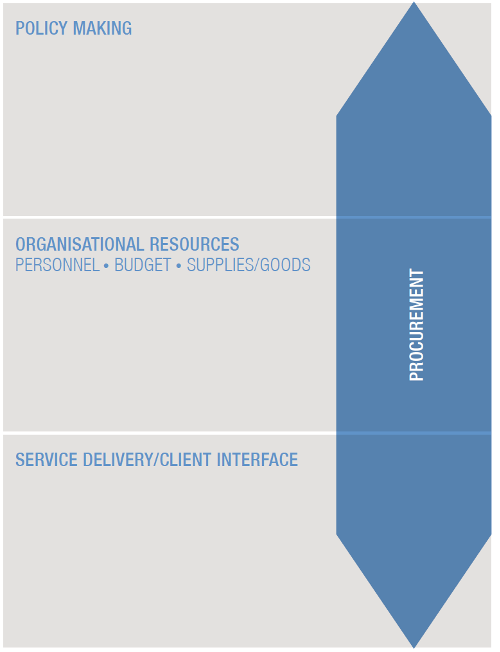

Figure 2. A framework for analysing corruption risks

Source: Trapnell et al. 2017:39.

This phenomenon refers to the coexistence of patrimonial rule with formal institutions in a system in which a patron uses public resources to secure loyalty by establishing clientelist ties with groups of similar political, religious or ethnic background (Gauthier and Reinikka 2001; Soest et al. 2014; Jenkins 2018).

This Helpdesk Answer will use Selinšek’s (2015) modified approach developed by Transparency International (Trapnell et al. 2017), which distinguishes between three different levels at which corruption may occur (see Figure 2):

- policymaking

- organisational resources

- client interface

Corruption risks at the policymaking level can manifest in two main forms. First, as grand corruption, which may involve the distortion of policies or actions taken by government officials which benefit insider interests at the expense of the public good (Trapnell et al. 2017:3; Jenkins 2018:7). Second, as undue influence, exerted by private companies with an aim to shape the process of the formulation/enforcement of laws and regulations by making illicit payments to state officials (Trapnell et al. 2017; Jenkins 2018:7). This process has been defined elsewhere in the literature as a phenomenon of state capture, particularly in the early scholarship on state capture in post-communist countries (see Hellman 1998; Hellman et al. 2003).

At the organisational level, which refers to the management of resources, such as goods, personnel and budgets, corruption risks are intensified when there is a weak oversight and abuse of discretionary powers, in the context of overly complex bureaucracies or when there is an overlap of the authorities and jurisdictions of relevant institutions (see Jenkins 2018:7). For example, patronage and nepotism may prevail over meritocratic practices in the process of recruitment, promotion, award and punishment of personnel (Trapnell et al. 2017:3). Various forms of corruption may occur at this level, such as embezzlement (see Table 1).

At the client interface level, which involves the interaction of tax officials with taxpayers, corruption typically manifests in the form of bribery or extortion (Jenkins 2018:7). Consequently, as discussed in detail below, some of the strategies to mitigate the risks of collusion at this level involve the digitisation of tax payments, by establishing e-services.

At this point, it is worth mentioning a typical classification of corruption in the sector of tax administration that distinguishes between collusive and abusive corruption. The former refers to a collusive relationship between tax officials and taxpayers which may result in taxpayers underpaying taxes in exchange for informal payments (see Fjeldstad 2005; Kabera 2008; Antonakas et al. 2013; Morgner and Chêne 2014; Jenkins 2018). The latter refers to situations where tax officials use their discretionary powers to extort bribes from honest taxpayers (Morgner and Chêne 2014). The remainder of this Helpdesk Answer will adopt the framework outlined above for assessing corruption risks and apply it to the sector of tax administration.

Key forms of corruption in tax administration

Table 1 lists the key forms of corruption that are particularly relevant for tax administration.

Table 1.Key forms of corruption relevance

|

Bribery |

Illegal payments to tax officials that may be used to secure tax exemptions, licences, ensuring that customs officials turn a blind eye to smuggling of illegal goods, etc. (see Fjeldstad 2005; Martini 2014). |

|

Revenue fraud |

Includes practices such as under-declaring goods, facilitated by tax and customs officials. |

|

Embezzlement |

Illegal appropriation of funds by tax officials for personal or other gains. It sometimes happens with the collusion of bank employees and auditors within the tax administration (Fjeldstad 2005; Martini 2014). |

|

Extortion |

Tax officials engage in extorting illicit payments from taxpayers, often relying on information asymmetry (see Martini 2014). |

|

Regulatory capture |

Firms exert influence on formulating taxation levels applied to their industry by using personal connections or illicit payments. |

|

Revolving doors |

The practice of moving between public office and private companies, which has been recognised as a problem within the tax administration in Africa. Tax officials may be recruited by private firms, as they can offer useful insider knowledge on processes within the tax administration (Martini 2014). |

|

Political corruption |

This may involve politicians interfering with the tax administration to grant favours to politically connected firms, such as tax exemptions, or targeting political opponents with burdensome audits (see Fjeldstad and Moore 2009; Bridi 2010; McDevitt 2015; Jenkins 2018). |

|

Patronage |

The existence of these networks can affect the process of selection, promotion, reward and punishment within the tax administration. |

Table 1.Key forms of corruption relevant for tax administration

Key drivers of corruption risks in tax administration

Identifying underlying drivers of corruption is important to be able to devise appropriate mitigation strategies.

Policymaking level

At the policymaking level, the most pressing underlying drivers of corruption in tax administration include:

- overly complex, unclear and/or inconsistent tax legislation and regulations (Martini 2014; Jenkins 2018)

- overlapping or unclear mandates of relevant institutions (McDevitt 2015; Jenkins 2018)

- insufficient autonomy of the tax or revenue authority (McDevitt 2015)

- a lack of adequate monitoring and supervision and a weak sanctioning regime (Rahman 2009; Martini 2014; Albisu Ardigo 2014)

First, tax legislation and regulations that are overly complex or unclear provide a fertile ground for various forms of corruption to occur as they provide loopholes that may be exploited by those attempting to evade taxes (see Jenkins 2018:10).

This is particularly relevant in the context of granting tax exemptions to foreign multinational companies. ActionAid’s (2017) research has suggested that governments in sub-Saharan Africa may be losing 2.4% of their GDP to tax incentives. Some existing research has provided empirical evidence that simpler tax systems are associated with lower corruption in tax administration (Awasthi and Bayraktar 2015). At the broader level, research has also shown that countries with better ability to control corruption benefit more from the tax reform (Yohou 2020).

Second, overlapping or unclear mandates of institutions relevant for the sector of tax administration are a strong underlying driver of some forms of corruption, such as political interference. For example, political officeholders may try to influence the tax administration in an attempt to grant tax exemptions or concessions to politically connected firms (see Fjeldstad 2006; Bridi 2010; Jenkins 2018). They can also instrumentalise existing tax regulations to target and harass political opponents, as evidence from Russia and Ukraine suggests (Markus 2015). If there are unclear mandates of key institutions, such as law enforcement, ministries, customs agencies and revenue authorities, this can negatively affect the consistency of applying and enforcing regulations (see Jenkins 2018:10). Furthermore, special interest groups may attempt to abuse the lack of clear mandates and responsibilities to exert undue influence on authorities to change legislation regarding tax exemptions, thresholds, VAT duties and others (see Jenkins 2018).

Third, insufficient autonomy of the tax administration has also been recognised as an important driver of corruption. For example, scholars have noted the importance of a clear division between the functional authorities of tax administration and those of the responsible ministry which develops tax policy and drafts legislation (McDevitt 2015; Jenkins 2018). This is a particularly relevant issue in Africa where establishing semi-autonomous revenue authorities has been one of the most common aspects of tax administration reform (Martini 2014:5).

Fourth, a poor monitoring and weak sanctioning regime may lead to a culture of impunity and further increase the risk of corruption in tax administration (Fossat and Bua 2013; Martini 2014). Africa has a poor track record of investigating corruption, particularly when it involves senior government officials (Fossat and Bua 2013; Martini 2014).

Organisational level

At the organisational level, the key underlying drivers of corruption in tax administration include:

- structure and effectiveness of the organisation, which include poor operational guidelines, inadequate policies and audit mechanisms, and weak oversight of personnel and budgets, as well as poor working conditions (e.g. low salaries) (Martini 2014; Jenkins 2018)

- a poor track record of investigating internal fraud and corruption (Fossat and Bua 2013; Martini 2014)

- non-transparent decision making, high levels of discretion, a lack of adequate checks and balances within the organisation

- a lack of meritocratic and transparent recruitment, promotion and reward standards (Rahman 2009)

- a lack of regular staff rotation to prevent the emergence of corrupt network structures (Purohit 2007; Jenkins 2018)

- a lack of professional ethics and integrity standards (Rahman 2009)

First, a poor internal structure and effectiveness of the organisation are important drivers of corruption in tax administration. Without a clear and strong oversight of personnel and budgets, tax officials can be incentivised to engage in corrupt practices, such as embezzlement and revenue fraud (see Jenkins 2018). For example, they may be involved in producing fraudulent invoices to under-declare goods (Martini 2014).

Second, a low sanctioning regime in terms of poor internal investigations of potential corruption also incentivises corrupt behaviour as it may lead to a culture of impunity within the revenue authority.

Third, related to the above point, a lack of clear checks and balances within an organisation can erode constraints on corrupt behaviour as it reduces accountability.

Fourth, when recruitment, promotion, award and punishment are based on patronage networks rather than on meritocracy, this opens a space for corrupt behaviour (see Martini 2014). In these cases, tax officials may be more loyal to their patron than to the public interest.

Fifth, and related to the previous point, the lack of regular staff rotation within the revenue authority may further contribute to embedding corrupt network structures (see Jenkins 2018).

Sixth, studies suggest that revenue authorities should have a clear ethics and integrity framework, with proportional sanctions in place for violating these standards (Martini 2014). The lack of such frameworks may drive the corrupt behaviour of tax officials.

Client interface level

At the client interface level, the key drivers of corruption in tax administration include:

- the modes of tax collection (e.g. in person, e-filing, cash or transfers, whether there is a third-party reporting or not)

- poor supervision

- a lack of access to information regarding tax processes that may lead to information asymmetries between tax officials and taxpayers

First, evidence suggests that reducing face-to-face interaction between tax officials and taxpayers may help in reducing corruption risks (Rahman 2009). This is typically achieved by automating the process of tax collection. For example, establishing e-filing in Afghanistan in five provinces in January 2020 helped to increase tax collection and curb corruption (World Bank 2021). Based on the new system, taxpayers were able access all their tax documents online and see the amount that they needed to pay (World Bank 2021), although since the fall of the government in August 2021, the situation is likely to change.

Studies also show the benefits of third-party income reporting by employers. The mechanism which makes third-party tax enforcement successful is the existence of “verifiable book evidence that is common knowledge within the firm”, which allows any individual employee to blow the whistle on collusion between the employer and the employee by revealing evidence of tax cheating to the government (Kleven et al. 2012: 31). Kleven et al. (2012) show that tax enforcement is improved by third-party reporting if the government prohibits self-reported losses or audits them more rigorously, reducing overall tax evasion.

Further, some recent research has demonstrated the self-enforcing role of the paper trail when it comes to value added tax (VAT) (Pomeranz 2015). Using field experiments, Pomeranz (2015:2566) found that transactions that are subject to VAT paper trails respond much less to an increase in the perceived likelihood of audit, suggesting that paper trail acts as a deterrent to tax evasion. An important implication of these findings is that VAT taxation, compared to other forms of taxation, leaves a stronger paper trail, and consequently provides more information to the relevant tax authorities (Pomeranz 2015).

Second, when there is a lack of automation or when automation processes cannot cover the entire country due to structural constraints, an issue of poor supervision may arise. Tax officials are typically assigned to a particular geographic area. In the context of poor supervision, tax officials have monopoly powers, and they may offer a favourable interpretation of tax regulations in exchange for illicit payments (Purohit 2007; Jenkins 2018:12).

Third, a lack of clear information about how tax processes are organised may result in corrupt behaviour by tax officials going undetected and put taxpayers in a vulnerable position due to information asymmetries (Albisu Ardigo 2014; Jenkins 2018). For example, tax officials can abuse taxpayers’ lack of knowledge of tax regulations and take advantage of it by extorting illicit payments (McDevitt 2015; Jenkins 2018).

One consequence of this lack of accountability is a weakening of tax morale and of general trust in institutions. This is the case in Africa, as survey evidence suggests a broad perception that tax revenues are not used efficiently and that the government is doing a bad job in tackling corruption (Martini 2014; Pring and Vrushi 2019).

Customs administration

At this point, it is important to also mention customs administration, which tends to be particularly vulnerable to corruption, as one of their key functions includes revenue collection (Fjeldstad et al. 2020). Drivers of corruption in customs administration derive from several factors:

- monopoly powers over certain technical processes

- tariff schemes with a large number of exceptions and red tape

- potential large illicit gains

- poor supervision in geographically dispersed areas with limited staff

- a need to cooperate with other agencies, such as immigration, police, transport inspection, which makes control more complex (Fereira et al. 2007; McDevitt 2015:3)

For example, complex regulations and high tariffs create incentives for traders to try to lower import charges by bribing customs officials (Fjeldstad et al. 2020:123).

Experts suggest that attentiveness to local context is necessary to properly understand the underlying drivers of corruption and consequently devise appropriate mitigating strategies. Although it is important to simplify regulations and establish a robust legislative framework, it is also important to supplement these with approaches to address underlying causes of corruption. Social norms, for example, tend to be deeply embedded in informal structures of relations. With this in mind, Rwanda and Georgia have adopted a comprehensive approach to tackle corruption in their customs administration (Fjeldstad and Raballand 2020; Fjeldstad et al. 2020). After the Rose Revolution in 2003, Georgia embarked on the road of comprehensive anti-corruption reforms (Papava 2006). With regards to countering corruption in tax administration, the reforms address both the broader social roots of corruption as well as technical measures (Fjeldstad and Raballand 2020). For example, the tax code was simplified, many loopholes were closed, and one-stop windows were created for clearing procedures in customs Fjeldstad and Raballand 2020).

Corruption risks in tax administration in Liberia

This section considers corruption risks in tax administration in Liberia. The first subsection provides a contextual background with regards to political and economic conditions and tax administration reform in Liberia. Subsection two addresses key drivers of corruption grouped into policymaking, organisational and client interface. Subsection three focuses on possible mitigation strategies considering the identified drivers of corruption in tax administration in Liberia.

Background on Liberia: political and economic context and tax administration reform

After the end of the civil wars in 2003, Liberia held three presidential elections. The last presidential elections, held in 2017, were assessed by international observers as generally credible and peaceful (Freedom House 2020). Since 2003, the country has made substantial efforts in improving the rule of law, political rights and civil liberties (Lee-Jones 2019; Freedom House 2020).

Despite this progress, there is a lingering influence of informal networks and power structures built during the war which are important obstacles to anti-corruption efforts (Funaki and Glencorse 2014).

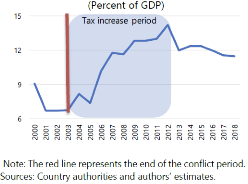

Liberia engaged in a comprehensive tax and tax administration reform in the period after the civil war (Akitoby 2018; DAI 2019). Figure 3 shows the increase in tax revenues as the percentage of GDP since 2003, which indicates an increase from 6.7% of GDP in 2003 to 14.2% in 2012.

Figure 3. Tax revenues in Liberia since the civil war

Source: Akitoby et al. 2020:19.

In 2014, the Liberia Revenue Authority (LRA) came into being as a semi-autonomous body of the Executive Branch of the Government of Liberia (LRA 2016:13).6d6e4e5dd955 This body was accorded greater autonomy than the previous tax and customs department, which was a part of the Ministry of Finance (USAID 2017).

Today, LRA is in charge of collecting almost all revenues that are received by the government and of ensuring that these revenues are transferred to the budget (USAID 2017). The main taxes include corporate income tax, personal income tax, goods and services tax, and excise tax (World Bank 2019).

The legal basis for taxation is the Revenue Code2276ec121eda of 2010, subsequently amended in 2016 and 2020 (NIC 2021). Liberia not only includes structural and operational aspects of all taxes in the Revenue Code but it also incorporates customs duties and all non-tax revenue provisions (USAID 2017:11).

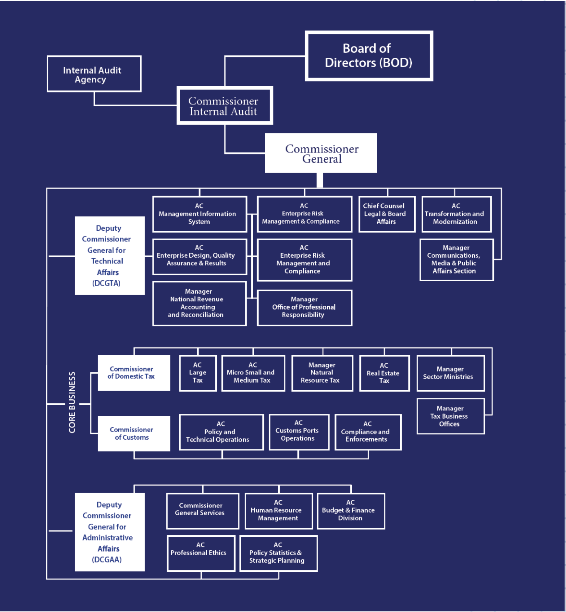

Figure 4 illustrates the current organisational structure of the LRA.

Figure 4. The organisational structure of the LRA

Source: LRA 2020:14.

Figure 4.The organisational structure of the LRA. Source: LRA 2020:14.

Efforts have been made to reduce corruption risks in tax administration in Liberia by, for example, establishing a desk audit system for large taxpayers and organising educating workshops for taxpayers (World Bank 2019:5). However, important challenges remain, and the perception of corruption is still high. As mentioned in the introductory section of this Helpdesk Answer, the perceived corruption in tax administration in Liberia is much higher than the regional average (Pring 2015). The results of the Global Corruption Barometer Africa survey suggest that 58% of surveyed Liberians think that their government is doing a bad job in countering corruption, which is around the regional average of 59% (Pring and Vrushi 2019). In the latest Afrobarometer (2021a:58) survey, when asked how many of “tax officials, like officials from the Liberian Revenue Authority” are involved in corruption, 32.5% responded “most of them”, while 15.7% responded “all of them”. A high perception of corruption in key institutions and groups in a country may also affect the general tax morale. Research suggests, for example, that petty corruption erodes tax morale in sub-Saharan Africa (Jahnke and Weisser 2019). Furthermore, an Afrobarometer survey (2021b) conducted in Liberia suggests that 73% of respondents think that it is “difficult” or “very difficult” to find out how government uses tax revenues. Finally, government officials, MPs, police and business executives are perceived as the most corrupt in Liberia, which offers some insights into the dynamic of regulatory capture in this country (Pring and Vrushi 2019:40).

According to the State Department of the United States, foreign investors tend to cite corruption as a key obstacle to investing in Liberia and specifically mention corruption in contract and concession awards, customs and taxation systems, among others (U.S. Department of State 2019; Congressional Research Service 2020).

Further, a weak judicial system also negatively affects the effective implementation of laws. Instances of officials engaging in corruption and low judicial accountability further exacerbate the culture of impunity (US Department of State 2019).

Key drivers of corruption risks in tax administration in Liberia

This section addresses the key drivers of corruption risks in Liberian tax administration at policymaking, organisational resources and client interface levels.

Policymaking level

Key challenges include:

- with regards to political corruption, there are allegations of the abuse of duty-free privileges (see The Liberian Express 2020)

- political interference, particularly with regards to processes around negotiating contracts between the state and private companies (e.g. concessions) (Makor and Miamen 2017)

- related to the above, the fact that Liberia has a narrow tax base and multiple tax concessions with a lack of adequate scrutiny on granting incentives creates favourable conditions for extensive corruption (World Bank 2019)

- there is also a lack of adequate oversight of the allocation of concessionary contracts as well as of fulfilment of obligations stated in the contracts

The abuse of duty-free privileges has been cited as one of the important drivers of corruption in Liberia. These privileges, granted to individuals such as MPs, to exempt them from custom duties, are often used as a mechanism of self-enrichment at the expense of communities (see Genoway 2019). In 2020, the LRA started an investigation into a firm called Building Materials Center (BMC) over an alleged tax evasion attempt. The firm is suspected of illegally clearing containers using a false claim of duty-free privileges for unspecified presidential projects (The Liberian Express 2020). BMC is a Syrian-Lebanese owned firm, which reportedly enjoys preferential treatment in getting lucrative government contracts under the administration of the current president, George Weah (The Liberian Express 2020).

In 2021, the LRA officially warned elected and appointed government officials to pay property taxes as many were reneging on this obligation. Furthermore, the LRA stated that it would restrict duty-free privileges if officials failed to pay their property taxes. It also threatened to publish the names of those who fail to pay their tax obligations in print and electronic media (Johnson 2021a).

There is a tendency for high-ranking public officials to use their powers to influence or discourage LRA customs officials from performing their duties (Johnson 2021a). In some cases, these officials reportedly serve as a front for foreign companies to exert influence to avoid paying taxes or avoid being closed down due to tax violations (Johnson 2021a).

Concessions are another important driver of corruption risks in Liberia. The government of Liberia through the National Investment Commission (NIC) and other agencies officially aims to create job opportunities, increase investments and improve foreign exchange, among other goals (NIC 2021). For investments over US$10 million, there are negotiations around concessionary contracts, which are then enacted into law (NIC 2021:26). These agreements typically include provisions on special favourable tax rates for companies in exchange for certain obligations to invest in social projects (World Bank 2019:18). Evidence based on informant interviews in Liberia points to the existence of vested interests between industry executives and policymakers with regards to concession agreements (Makor and Miamen 2017:29). Large businesses are able to use their political influence to renegotiate the terms of their royalty obligations (USAID 2017:44). For example, an audit of resource deals in Liberia between 2009 and 2013 found that only 2 out of 68 concessions awarded by the government were compliant with the law (Hirsch 2013). Experts pointed out numerous flaws in these deals that create a fertile ground for corruption, such as non-competitive bidding, missing documentation and lapses in the procurement procedure (Hirsch 2013). A case in point is the Liberian government’s deal with ExxonMobil and its partner Canadian Overseas Petroleum Resources from 2012 for an oil field. This deal was not in compliance with Liberian law as the arrangement would have generated 5% in royalties, whereas the law required 10% (Hirsch 2013). Exxon’s purchase was accompanied by large payments made by the Liberian oil agency to six Liberian officials who approved the deal, including, among others, finance, justice and mining ministers (Global Witness 2018).

In 2017, the Forest Industrial Development and Employment Regime Act was passed, which officially aimed to preserve investments and secure employment for Liberians by offering tax breaks to companies (FPA 2017). In practice, according to research by Global Witness, the law offers subsidies and protection to logging companies at the expense of the Liberian population (FPA 2017). The data suggest that logging companies’ debt to the government as of October 2017 was almost US$25 million in taxes and fees (Global Witness 2017). Consequently, Global Witness has argued that with such a poor record of previous investments, and of its monitoring, it is unlikely that further tax waivers would be beneficial to the Liberian population (FPA 2017). There is an additional danger of political interference in this process as evidence collected by Global Witness (2017:3) reportedly indicates that some logging companies are illegally owned by politicians, such as members of House of Representatives Alex Tyler, Moses Kollie and Ricks Toweh.

A USAID (2017:10) report on benchmarking the tax system in Liberia emphasised the issue of tax exemptions to selected producers. It pointed out that unless these exemptions are granted based on clear and transparent rules, they are vulnerable to abuse and mismanagement. This is particularly relevant for tax exemptions in the natural resource sector, which may potentially explain the fact that the corporate income tax productivity of Liberia is less than half of its neighbours in Africa (USAID 2017:10). Although relatively abundant in natural resources, such as iron ore, rubber and gold, Liberia collects minimal public revenues, which is likely due to arbitrary tax exemptions outside of the legislative oversight (World Bank 2019:11).

Further, there is evidence of the use of shell companies to conceal legitimate business income from tax obligations in Liberia (Cuffy 2020). Shell companies may also be employed by high-ranking government officials colluding with business owners to transfer illicit income from bribery and corruption to other destinations (Cuffy 2020).

At a broader level, recent attacks on employees of the LRA have shown the level of insecurity in which tax officials work. For example, there was an attack on an employee of the LRA’s anti-smuggling unit, which was the fourth attack on LRA officials in the seven months to May 2021 (Johnson 2021b).

Another example involves three tax officials who worked for the LRA and one senior auditor working for the International Audit Agency (IAA), who were found dead within one month of each other in 2020. At the time of death of IAA Director-General Emmanuel Barten Nyeswu, he was auditing Liberia’s Covid-19 relief fund as well as the financial statements of the National Ports Authority. Some opposition figures in the country believe that these deaths were related to the work the auditors were doing (Seagbeh and Mugabi 2020). These attacks, especially if they are not properly investigated, can incite fear and insecurity in tax officials and further contribute to the embedding of a culture of impunity in the context of a weak sanctioning regime.

Organisational resources

An important challenge at the organisational level is the insufficient capacities within the internal audit department. According to the LRA’s annual report, this department has reported 117 auditable areas with only 13 auditors in the department. An additional problem is that the entire audit process is done manually, which puts a lot of constraints on auditors in terms of their performance (LRA 2020:70).

Liberia ranks 184 out of 190 countries in the Trading across Borders measure of the Doing Business list and 44 out of 48 in sub-Saharan Africa (Doing Business, no date). Companies need to invest 144 hours in documentary compliance and 193 hours in border compliance,bcfda3594686compared to an sub-Saharan average of 71.9 and 97.1 respectivelyaa51f203547d (see Doing Business 2020). As a comparison, documentary compliance takes 2.3 hours and border compliance 12.7 hours in high income OECD countries.0de6d3c1c934 In terms of costs, companies in Liberia need US$405 for documentary compliance and US$1,103 for border compliance, compared to the average of US$172.5 and US$603.1, in sub-Saharan Africa, respectively5829122411be (see Doing Business 2020). Evidence suggests that extra costs and time in Liberia compared to OECD countries includes, among others, costs of corruption and fraud (USAID 2017:33). Some of the vulnerabilities to corruption that may cause revenue loss at customs centres include insufficient capacities of internal controls and investigation capabilities (USAID 2017:32).

Widespread smuggling poses yet another problem, in part due to porous borders. For example, evidence suggests that, considering the ease of crossing the river and selling gold in neighbouring Côte d’Ivoire and Guinea, gold smuggling over Liberian borders is a serious problem (Hunter 2020:35). There are important infrastructural challenges at some border crossings in the country, as some border centres have limited electricity and internet connectivity (USAID 2017:44).

Client interface

In its annual report for 2015/16, the LRA listed among key challenges the issue of the lack of funding to support the implementation of their strategic plan, as well as the general tax paying culture, characterised by false declarations, under-reporting, smuggling, mispricing and other various forms of tax evasion.

Extortion by tax officials remains an important challenge in Liberia. For example, there was a criminal verdict against two former employees of the LRA who were convicted of extortion at the Customs Business Office at the Freeport of Monrovia in 2015 (All Africa 2017).

Issues exist with tax evasion by brokers as well. For example, the LRA’s customs department has suspended the brokerage licence to the firm Snokri Clearing and Forwarding Inc. for its alleged involvement in false declarations that resulted in revenue losses for the government of Liberia (FPA 2020).

Data quality challenges also provide fertile ground for corruption to emerge. The LRA’s 2019/20 annual report states that the low quality of the data makes it a challenge to effectively monitor taxpayers for many reasons, such as multiple accounts for one kind of tax, inadequate taxpayer registration information, and others (LRA 2020:70).

Limiting the contact between tax officials and taxpayers is one way to reduce corruption risks. Important steps in this direction have been made in Liberia by establishing an e-filing platform for all types of taxes and a platform for tax and non-tax payments via commercial banks and mobile money platforms (USAID 2021). However, due to poor infrastructure, these new functions are not widely used beyond the capital, partly due to a low coverage of internet connectivity and electricity (USAID 2017:22).

Educating taxpayers on their rights is also important to reduce risks of corrupt behaviour by tax officials. Liberia has established the Taxpayer Advocate Service,6feb88e83649 which is in charge of providing support to taxpayers who are having trouble dealing with the LRA (Kitain and Coon 2018). Further efforts would be needed to promote this service beyond the capital.

Mitigating strategies for curbing corruption risks in tax administration

Given their position at a critical intersection of the public financial management system, tax officials can play a key role in curbing corruption (OECD 2013; Martini 2014).

This section will first address some general considerations from the literature and policy relevant research on effective strategies for mitigating corruption risks in tax administration. Second, it will address the possible strategies for addressing the key drivers of corruption in tax administration in Liberia.

General considerations

Experts have identified a number of steps that may help to curb corruption risks in the tax administration, with some studies focusing specifically on the African context. Rahman (2009:2-4) suggests that successful tax administration reform should follow a specific sequence. In the short term, it should include:

- simplifying tax procedures and processes: this should reduce tax officials’ discretionary powers and the abuse of tax laws; for example, a recent study from Belgium has shown that simplifying communication significantly increases tax compliance (De Neve et al. 2021)

- facilitating underlying legal reform: an effective enforcement mechanism is necessary as a lower tax burden will not increase compliance in and of itself (Rahman 2009:3)

- providing training and capacity building for tax officials and the private sector: this can improve trust between the tax administration and taxpayers and reduce information asymmetries which often serve as fertile ground for various forms of corruption, such as extortion

In the medium-long term, it should include:

- redesigning the structure of the tax administration to establish its institutional autonomy: developing a risk-based auditing system

- reorganisation of the system of tax services based on types of taxpayers

- automation, especially electronic services to reduce face-to-face interaction between tax officials and taxpayers and establishing clear transaction records

- implementation of a human resource management policy: clear and transparent recruitment, promotion, award, and punishment policy, developed ethics standards and codes of conduct

Specifically, in the African context, there are several important corruption mitigating approaches:

- establishment of semi-autonomous revenue agencies with the goal of insulating them from the interference of governments and politicians. Additionally, creating independent management boards that would oversee the operations of revenue agencies could also increase their independence, as well as having an operational budget independent of regular annual budgeting processes. The main problem with these agencies in sub-Saharan Africa has been their lack of independence and legal safeguards to preserve their autonomy (Fjeldstad and Moore 2009; Kloeden 2011; Martini 2014).

- introduction of self-assessment: this can curb corruption as it limits the direct interaction between tax officials and taxpayers and reduces the opportunities for negotiations between the two parties (Martini 2014)

- strengthening internal investigation mechanisms; for example, by having an independent unit in charge of investigating corruption allegations within the tax administration)

Mitigating strategies in Liberia

As explained in the previous sections, Liberia has significantly improved its tax administration over the last decade, but some important challenges persist.

First, the allocation of tax concessions is an important driver of corruption risks. One potential strategy to minimise corruption risks in this sphere is to strengthen the audit capacities of the LRA to oversee companies operating in the natural resource sector (World Bank 2019:15). To increase transparency, it would also be helpful to create a database of existing tax incentives and exemptions that are granted through executive orders and decrees (World Bank 2019:15). This transparency is necessary to reduce the likelihood of rent seeking behaviour. One additional step would be to consolidate tax exemptions in the Revenue Code so that they can be subject to legislative review (World Bank 2019:20). Not only is the process of granting tax exemptions problematic but there needs to be better monitoring and control to ensure that those entities that received tax breaks and other concessions meaningfully comply with their reciprocal obligations, particularly with regards to local communities.

Second, the process of internal investigation within the LRA needs to be strengthened, particularly with regards to customs, considering that there is a lot of space for corrupt behaviour, as explained in the previous section (USAID 2017:33). Although the LRA has a professional ethics division, which is committed to countering fraud, this office needs further support for training, logistics and equipment to improve its internal investigation capacities (USAID 2017:42).

Third, in cases of corruption scandals involving brokers, it is necessary to improve broker certification requirements as allegations of brokers engaging in valuation fraud and misreporting quantities exist (USAID 2017:43).

Fourth, a review of tariffs and payment systems would be important to change incentive structures and encourage taxpayers to pay taxes. For example, USAID (2017:6) argued that applying specific instead of ad valorem excise tax rates should, among other benefits, reduce the scope of corruption, as ad valorem tax rates create undervaluation issues.

Fifth, more efforts are necessary to make the e-filing system accessible in rural areas since poor infrastructure contributes to the underutilisation of recent automation efforts in the tax collection process.

- The survey was conducted between March 2014 and January 2017, covering 119 countries, territories and regions.

- See: https://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/

- The survey included 28 countries in sub-Saharan Africa between March 2014 and September 2015 (Pring 2015).

- The data is based on a survey from 34 African countries conducted between September 2016 and September 2018.

- See: https://revenue.lra.gov.lr/.

- See: https://revenue.lra.gov.lr/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/REVENUE-CODE-LIBERIA-REVENUE-CODE-AMENDEMENT-2020-min.pdf.

- See: https://www.doingbusiness.org/content/dam/doingBusiness/country/l/liberia/LBR.pdf.

- See: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/data/exploretopics/trading-across-borders

- See: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/data/exploretopics/trading-across-borders.

- See: https://www.doingbusiness.org/en/data/exploretopics/trading-across-borders.

- See: https://revenue.lra.gov.lr/taxpayers-advocacy/