Query

Please provide a summary of the key corruption risks and potential mitigation measures in Mozambique’s energy sector.

Introduction

Mozambique is categorised as a low-income country0a236142acc6 with about two-thirds of its 33 million inhabitants living and working in rural areas (World Bank 2024). It has an abundance of natural resources, and it is hoped that the recent global interest in its energy sectora1e426ce8abb can play an important role in driving the country’s economic growth (African Development Bank Group n.d.). In 2023, Mozambique’s gross domestic product (GDP) grew around 5%, which was primarily driven by the start of natural gas production at the Coral South offshore facility (World Bank 2024).

However, to date, the benefits reaped from natural resources have not been distributed equally and Mozambique remains some way from becoming a middle-income country (Gaventa 2021). There are deep spatial inequalities between sub-national regions, including access to basic services, such as education, health, water and electricity (World Bank 2024; Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019). Despite recent progress, electricity access among the general population is estimated at 41% (World Bank 2023). In rural areas this is even lower, at only 8% of the population having access to electricity (World Bank 2021).

Several challenges hinder Mozambique’s development. Slowed growth related to the COVID-19 pandemic has been further compounded by an ongoing conflict in its gas-rich northern province of Cabo Delgado (African Development Bank Group n.d.). A decade after the hidden debt scandal,37c1836807d4 perceptions of corruption continue to be a prominent governance issue, with the country ranking 145 out of 180 countries in the most recent Corruption Perceptions Index (Transparency International 2023).

The energy sector is vulnerable to corruption – particularly political corruption and regulatory capture – which has slowed growth and prevented the wider population from accessing the benefits of Mozambique’s vast resource wealth and green energy potential. Corruption impacts the sector at all stages, from exploration to the resource extraction and production stage, through to the transmission and distribution of electricity. Political elites and their related businesses have consolidated power over the energy sector’s regulation and captured rents. At the same time, large multinational companies have influence over the sector due to their economic strength. While there have been recent commitments from the Mozambican government to ensure the integrity of the sector and safeguard its profits for the wider population, such as through the creation of the Sovereign Wealth Fund and an online registry for mining licenses, there is room for improvement.

The current state of the energy sector in Mozambique

As a net energy exporter, Mozambique is considered to have the largest power generation potential of all Southern Africa. The main destinations of exports are its neighbours, South Africa, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Botswana (IEA 2021; OEC n.d.; Deloitte 2024). Mozambique also has huge potential related to the development of green energy sources – solar, wind, and hydroelectric energy (Lopes 2024).

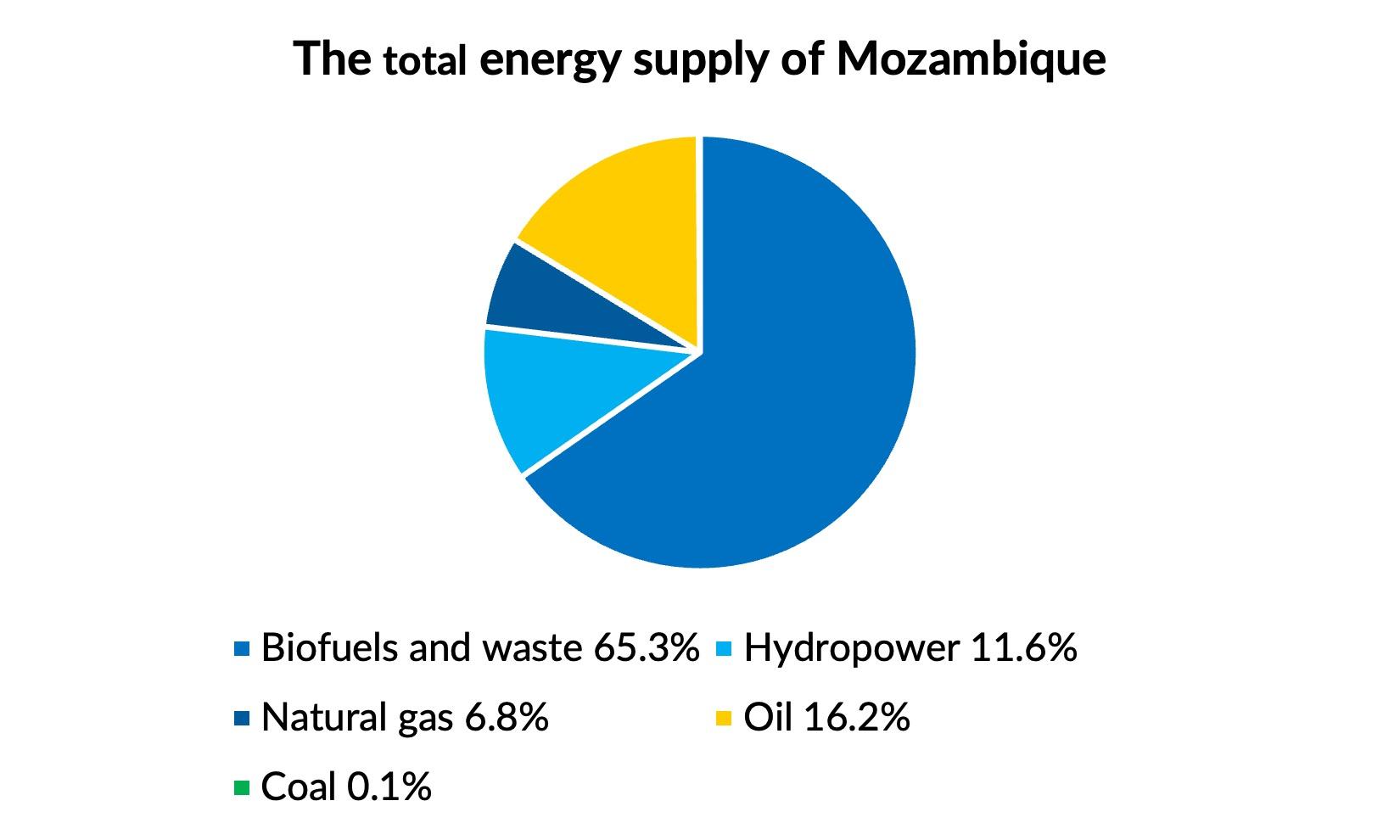

Figure 1: All energy produced in or imported to Mozambique (minus what is stored). Some of these energy sources are used directly while most are transformed into fuels or electricity for final consumption

IEA 2021.

Mozambique’s domestic electricity generation is heavily dependent on hydropower, which accounts for about 77% of all electricity generated (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019). Nonetheless, as seen in Figure 1, despite Mozambique being a net exporter of energy, most of the Mozambican population remains heavily reliant on biofuels and waste, which typically consists of the burning of firewood and charcoal (African Union n.d.). The wood fuel sector is informal throughout the country but is cost-effective for low-income families (Salva Terra 2022).

The energy sector has a long history of garnering interest and financing from overseas investors; most of this was originally generated by the Cahora Bassa dam. Construction of the dam began in 1969, initially financed by the Portuguese colonial government, and later partly financed by investors from South Africa. In 1975, an agreement was signed between Portugal and Frelimo – Mozambique’s ruling party – to grant Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB) (a Portuguese para-statal) the rights to manage 82% of the dam until Mozambique could repay its construction debt (Isaacman 2012). Because it was unable to repay this debt until 2007, the Portuguese company retained effective control of the dam and negotiated the sale of most of its electricity to South Africa (Isaacman 2012).

The Cahora Bassa dam currently supplies around 25% of the electricity that is provided by the state to the general population; the majority of the electricity generated by the dam is still exported to South Africa (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019; Kirshner et al. 2019). Mozambique’s Mphanda Nkuwa hydropower plant has been developed by Chinese investors and, more recently, with the support of French EDF-led investments (Conrad, Fernandez and Houshyani 2011: 45; Reuters 2023).

Mozambique also has the largest natural gas reserves in Sub-Saharan Africa (Deloitte 2024). Natural gas was first discovered in 1961 at the Pande gas field, leading the Mozambican government to sign an agreement with South Africa to allow its gas into the South African market (Gqada 2013). Natural gas has since been discovered in two additional areas: the Rovuma Basin off the coast of Cabo Delgado Province, and the Mozambique Basin (Gqada 2013). After the gas discoveries were made in Cabo Delgado, with licensing for exploration given to the multinational petroleum companies Andarko (who later sold its interests to Total) and Eni (Italy) (Gqada 2013: 10).

In May 2024, the Ministry of Mineral Resources and Energy (MIREME) signed concession contracts for oil exploration and production with China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC) for offshore blocks in Nampula province (The Maritime Executive 2024). This involvement of large multinational companies is indicative of a major shift in Mozambique’s political economy of energy starting in the 2000s, when the government opened its economy to large-scale foreign investments in the extractive resources sector (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019). The Mozambican government has openly called for further Chinese investment into its electricity industry to support its infrastructure development and hydroelectric projects (Forum Macao 2018). As of 2023, China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC) signed a cooperation framework agreement with Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetos (ENH) to jointly work on the ‘long-term strategic goal of China-Mozambique oil and gas cooperation’ (CL Brief 2023).

Mozambique is considered to be in a strong position generate green energy, given its abundance of hydroelectric, wind and solar resources (African Development Bank Group 2023). The government’s Energy Transition Strategy has committed to an investment of US80 billion in renewable energy (Howe et al. 2024). Current projects underway include the Cuamba II solar plant located in Niassa province, and new wind energy projects in Inhambane and Namaacha (O Pais 2024).

Key actors

Table 1: Key actors and their role in the Mozambican energy sector

|

Category |

Actor |

Description |

|

Ruling party |

Frelimo (Frente de Libertação de Moçambique) party |

Originally a liberation movement which won independence from Portuguese colonial rule in 1975, this political party has been in power ever since (Hanlon 2020). |

|

Ministries |

The Ministry of Mineral Resources and Energy (MIREME) |

Responsible for planning the country’s national energy strategy and its central body, the National Energy Directorate (DNE) conducts analysis and preparation of energy policies and licensing of electrical installations (Proler n.d.). It supervises the energy regulatory authority (ARENE) and controls the mining activities and licenses (IMF 2019). |

|

Ministry of Economy and Finance (MEF) |

The MEF is responsible for formulating and implementing the country's economic and financial policy. In the context of the energy sector, the ministry plays an important role in resource allocation, managing revenues from the sector and promoting investments. |

|

|

Regulatory agency |

ARENE |

ARENE and is supervised by MIREME and is responsible for regulating the subsectors (including those resulting from any source of renewable energy, liquid fuels, biofuels, and the distribution and commercialisation of natural gas), ensuring compliance with laws, regulations and other standards, and the suspension of contracts where necessary (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019: 11; ERRA n.d.). |

|

Government agencies |

National Petroleum Institute (INP) |

The INP is responsible for regulating, supervising and promoting the oil and gas industry in Mozambique. Its functions include granting exploration and production licenses, as well as ensuring operations are conducted in accordance with Mozambican laws and regulations. |

|

National Mining Institute (Instituto Nacional de Minas) (INAMI) |

INAMI regulates the exploration and production of mineral resources in Mozambique. It is involved in issuing mining licenses, supervising mining activities, and ensuring that mining practices are sustainable and beneficial to the country's economy. |

|

|

Mozambique Tax Authority (AT) |

The AT is responsible for the administration and collection of taxes in Mozambique. In the energy sector, the AT ensures energy and natural resource companies comply with their tax obligations, thereby contributing to public revenue. |

|

|

Administrative Tribunal |

Oversees public procurement and audits government expenses. |

|

|

Public companies |

Empresa Nacional de Hidrocarbonetos (ENH) |

The commercial branch of the government in the oil and gas sector, it is involved in the entire value chain for natural gas (Frelimo et al. 2020). |

|

Electricidade de Moçambique (EDM) |

State-owned, vertically integrated utility that is responsible for the generation, acquisition, transmission, distribution and sale of electricity, as well as managing the National Network (Proler n.d.) |

|

|

National Energy Fund (FUNAE) |

FUNAE delivers off-grid renewables in rural areas, and low-cost energy production (Kirshner et al. 2019; Proler n.d.). |

|

|

Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa |

A public hydropower generation company. |

|

|

Multinationals |

Eni (Italy), ExxonMobil, Chinese National Petroleum Company (CNPC), China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), TotalEnergies (France), Mitsui & Co (Japan), Bharate Petroleum (India) (Mozambique LNG n.d.; Gqada 2013) |

Several international and multinational companies involved in hydropower and natural gas production in Mozambique. |

Key challenges

The political landscape of Mozambique is dominated by the ruling party, Frelimo, which has been in power since the country gained its independence from Portugal in 1975 (Hanlon 2020). The Frelimo party has been accused of serious misconduct during presidential elections by both EU and US observers (Hanlon 2020: 495-6). Power is concentrated in the hands of the political party members, with close connections between the party, the state, and the private sector (Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020).

Political power is centralised in Mozambique, with the president at the head of the country’s vital systems – the public sector, legal system, and the private sector (CIP 2021: 63; BTI 2020). This allows any person close to the president to enjoy privileges, while other segments of society are excluded (Cortes 2018 cited in CIP 2021). There is limited capacity in the legislative and judicial branches to hold the executive to account as the judiciary is financially and materially dependent on the government (BTI 2024: 12). Office holders of the judiciary are formally independent but are also high-ranking political party members, which undermines independence and prevents effective checks and balances (BTI 2024: 12).

The extractive industries account for a substantial portion of the economy (BTI 2024: 18). The lines between public and private are often blurred, as domestic business interests connected to the Frelimo party influence government decisions (Freedom House 2021). Foreign donors and investors also have a strong influence on economic policy and public sector reform in the country, as these are the other major contributors to the economy (Freedom House 2021; Flentø and Santos Simao 2020: 1). For instance, the petroleum hydrocarbon law in Mozambique cannot be changed for the next 35 years without the permission of both Electricidade de Moçambique (EDM) and TotalEnergies (Cascais 2023). This exemplifies the influence of both domestic and foreign companies on policymaking.

Another key challenge that impacts the energy sector is the legacy of Mozambique’s colonial past. The country is still heavily shaped by colonialism, having experienced colonialism under Portuguese rule, wherein the country was scarred by the slave trade and the brutal civil and political repression by Portuguese authorities (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019). This history has impacted the provision of electricity in the country today, as during the colonial period regions were deliberately divided between different chartered companies, which controlled the economy of each region autonomously (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019; Pereira 2022).

Under Portuguese rule, northern, central, and southern regions were divided into separate areas governed by charter companies (often British), which hindered the possibility of an integrated national development strategy and infrastructure (such as roads, and power transmission lines), linking regions of the country to other countries rather than interior regions in Mozambique (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019: 9). This has resulted in a fragmented electricity network with unequal distribution, divided into three distinct systems.

After colonial rule ended, it was important for the political classes to gain control of the country’s energy sources and infrastructure in order to reaffirm their independence and fulfil expectations for progress and modernisation (Showers 2011 cited in Kirshner et al. 2019). From 1995, EDM began expanding the domestic grid with support from the donor community, regional partners and foreign investment (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019: 9). For the period of 2020 to 2024, these donors include the World Bank, KfW Development Bank, Government of Norway, the French Development Agency (AFD) and ASDI (Alberto et al. 2020: 56).

However, in part due to the deep divisions established during colonial rule, the electricity network in Mozambique continues to bypass rural areas inhabited primarily by low-income groups, making it one of the countries with the lowest rates of electricity access in the world (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019). Further challenges include the fact that the infrastructure, including transmission lines, is inefficient and aging, which contributes to frequent power outages across the country (Salite et al. 2021).

Another major challenge is that a large portion of the electricity generated in Mozambique is exported, rather than being consumed domestically, and this has distorted priorities in the sector. This is not only the case in Mozambique. It is estimated that 89% of liquid natural gas from new infrastructure projects in African countries is exported to Europe, leading experts to question how much electricity from these projects is distributed to citizens in the producing countries (Younes 2022).

Due to unequal access and/or low income, a substantial portion of the population relies on charcoal as an energy source (Salva Terra 2022). The impact of charcoal is twofold, its production can lead to uncontrolled deforestation and changes in the natural ecosystem, but, at the same time, families depend on it for cooking and heating (Salva Terra 2022; Luz et al. 2015). Analysis of charcoal supply chains find that local producers and communities are benefiting the least from the value chain and profits are made by outside producers (Luz et al. 2015). Charcoal is produced, processed and transported informally, outside of legal frameworks, making work on the sustainability and regulation of the sector particularly difficult (Salva Terra 2022: 11). Despite this, there have been some attempts at regulating the activity. For example, the sale and transportation of charcoal is regulated under a new law (no. 17/2023).

Most of the electricity generated through hydropower in Mozambique is exported to South Africa under a long-term Power Purchase Agreement (PPA) between Hidroeléctrica de Cahora Bassa (HCB) and South Africa’s electricity utility (Eskom), which will remain in force until 2029 (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019). Selling the majority of electricity produced through hydropower to South Africa means that the state-owned utility company, EDM, has to purchase electricity from other energy sources, often with higher tariffs. This has reportedly stretched EDM’s finances and constrained its ability to fund grid extension and maintenance (Cotton, Kirshner and Salite 2019). Electricity provision to public institutions is also prioritised and the cost of connecting low-income and rural households is extremely high. Salite et al. (2021) report that EDM is increasingly in debt, further hindering its ability to ensure reliable, quality and affordable services.

Overall, the World Bank (2023) concludes that economic growth has not been inclusive in Mozambique and has not resulted in widespread poverty reduction. In its analysis, this is because economic growth has been mainly driven by extractive industries’ megaprojects and foreign direct investment (FDI), which have generated limited employment opportunities for local people1ea0389da0f4 (World Bank 2023).

Corruption risks in Mozambique’s energy sector

Political corruption

Resource-rich countries, particularly those who have been previously colonised, tend to have higher rates of conflict and authoritarianism and lower levels of economic growth; a phenomenon which is described as the ‘resource curse’ or ‘paradox of plenty’ (NRGI 2015). Research indicates that even during periods of discovery of natural resources, corruption and economic problems may arise, particularly in countries that lack strong financial institutions and legal systems (Younes 2022; Mihalyi and Cust 2017). This is referred to as the ‘pre-source curse’, which occurs during the period between discovery of the natural resources and production, and results in overblown expectations of the revenues that will be generated (Dupuy and Katera 2019).

In 2013 European and Russian banks, audit company Ernst and Young, a French Lebanese businessman, and Mozambican officials, arranged for US$2 billion in secret loans (equivalent to 12% of GDP) without the approval of the Mozambican parliament (Wensing 2022). The loans were meant for maritime security and the tuna fishing industry, however millions in bribes and corrupt payments were siphoned off by officials, and the subsequent projects have delivered no benefits to the country (Wensing 2022). The ‘hidden debts’ corruption scandal in Mozambique has been linked to the development of the energy sector and the discovery of vast amounts of offshore natural gas (Wensing 2022; Younes 2022).

Reports argue that that the loans were heavily influenced by the expectations that the gas revenues could repay the loans that were taken out (Wensing 2022). As oil multinational companies rushed to develop new fuel reserves, Mozambican officials also used the secret loans to establish commercial entities that would provide shipyard services and security for these multinational companies to carry out their work (Younes 2022).

According to the IMF, Mozambique will not be able to pay off these loans for decades, and the scandal sent the country into an economic crisis and international donors pulled out of the country (Cortez et al. 2019). Mozambique is therefore further reliant on gas revenues to pay off the increase in sovereign debt instalments (Cascais 2023). It is also becoming clear that natural gas projects are associated with significant environmental harm; however, the economic gains from fossil fuels may lead Mozambique’s governing class to overlook these risks (Cascais 2023). Public expenditure (education, health etc.) was also cut to less than a half of what it previously was since the corruption scandal, leading to poverty and inequality substantially increasing (Cortez et al. 2019).ec68b0af7448

Conflicts of interest

Many Mozambican extractive companies are linked to the Frelimo party and the Frelimo party members are sometimes described as ‘business-political elites’ (Yang 2021). Analysis by Centro de Integridade Publica (CIP) (2022) identifies a number of companies that are designed to provide services to multinationals in the oil and gas sector. Many of these companies resell licenses and concessions for natural resources and these are then distributed to international operators for large sums (CIP 2022). CIP’s (2022) report argues that these constitute rent-seeking income companies who use the political monopoly of their owners to earn income.

The former Mozambican president (2005-2015) was reported to have wide-ranging business interests which included the mining and the extractive industries (amaBhungane 2012). His family, through the companies Intelec Holdings and Tata Mocambique, held seven licenses for prospecting and mining research (Verdade 2014). All of these were assigned by the National Directorate of Mines when the president won their post and Intelec Holdings ranks in the top 100 larger companies in Mozambique (KPMG 2021).

However, many of the mining companies that are operating in Mozambique are registered outside of the country, particularly in Mauritius (which is considered a tax haven) (CIP 2021: 4). This makes it particularly difficult to identify the ultimate beneficiaries of the concessions and whether the ownership constitutes a conflict of interest (CIP 2021: 4).

EDM, as a state-owned enterprise (SOE), is closely linked to the Felimo party, and enjoys a monopoly over the domestic electricity market (Kirshner et al. 2019; Salite et al. 2021). Decisions are centrally managed in the Maputo headquarters in coordination with central government and these decisions have tended to prioritise areas of high demand in urban centres (Kirshner et al. 2019). Salite et al. (2021) argue that the party’s influence over EDM’s operations and goals (under the pretence of socio-economic viability) has negatively impacted the work of the SOE and has enabled financial accumulation for the Frelimo party and affiliated elites.

Challenges in the regulatory environment

Africa Energy Portal’s Electricity Regulatory Index for Africa identifies independence, accountability, transparency of decisions, and participation as particular areas of weakness in Mozambican energy governance. The law does not prohibit the appointment of persons to the board or to a CEO position at the Energy regulatory authority (ARENE) even if they have previously held positions in a regulated entity (ERI 2022). There is also no legislative requirement for ARENE to answer requests from or attend hearings organised by parliamentary committees, and the body is considered to have low institutional capacity (ERI 2022). Furthermore, MIREME, which supervises ARENE, acts as a counterparty at the signing of contracts, but at the same time must regulate and supervise their implementation, which constitutes an additional conflict of interest (CIP 2022).

According to CIP, (2022) the legislation that oversees the extractive industries has also been approved or amended in such a rapid way over the years, causing omissions and inaccuracies that may potentially open the sector for corruption. The legislation is complex, and this has reportedly provided opportunities for officials that are responsible for issuing licenses, permits and other formal approvals for commercial activities to extract bribes (CIP 2022).

Inadequate due diligence processes by foreign investors

Environmental regulations have been overlooked by foreign investors and multinationals in the sector, and loose interpretations of the law have led to questionable environmental impact studies (CIP 2022). These regulations have reportedly been disregarded or enforced inconsistently by the financial institutions that provide financing to Mozambique’s energy projects (GAN Integrity 2020).

Several NGOs conducted research into the role of Export Credit Agencies (ECAs),ccaf6f80ec87 and identified irregularities in the approval process of public finance through ECAs from countries investing in Mozambican gas. ECAs from the Netherlands, France, Italy, UK and the US approved around US$9 billion in direct loans, credit and insurance to fund Mozambique’s gas projects (Wensing 2022). Due diligence measures had been taken by the ECAs prior to the project funding, but Wensing (2022) note that the analyses and assessments by which the projects were approved are unclear. The UK and US ECAs committed their support following the outbreak of a violent insurgency in 2017 in Cabo Delgado province. The Dutch committed the day after a violent attack on Palma in 2021, which caused TotalEnergies to declare a force majeure (Wensing 2022). They also noted in their analysis that the climate impacts undertaken by the ECAs were not sufficiently assessed despite experts warning for years about the continued investments in natural gas (Wensing 2022).

Mutemba (2023) notes that the absence of rigorous oversight mechanisms in the sector is being driven largely by investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) regimes in the extractive industries, which could expose Mozambique to enormous financial liabilities. These regimes are referred to in international investment contracts between state authorities and foreign investors in the oil, gas and coal industries, and recourse in the event of a dispute would bypass the national judicial system. The author (Mutemba 2023) suggests that ISDS clauses could seriously challenge any new public-interest regulations in areas such as health, environment, community rights or labour protections. Likewise, Messenger (2024) also contends that ISDS clauses may hinder the green transition away from fossil fuels. While not a corruption risk in itself, ISDS clauses underscore the influence that foreign investors can exert over the regulation of the energy sector.

The land conflict in Cabo Delgado (which has its roots in inequalities that were worsened due to the discovery of minerals and natural gas deposits) has led to the displacement of local communities and threatened their livelihoods (ACAPS 2023). However, mining concessions in the region continue to be given out to companies despite these ongoing issues (CIP 2021). The mining concessions in Cabo Delgado are concentrated among a small number of companies who are registered outside of Mozambique which, CIP (2021: 9) argues, helps to distance these companies from the ongoing conflict. The local populations have been unable to benefit from the mining sector, which continues to operate and expand, further risking escalation and displacement in the region (CIP 2021).

Corruption in public contracting

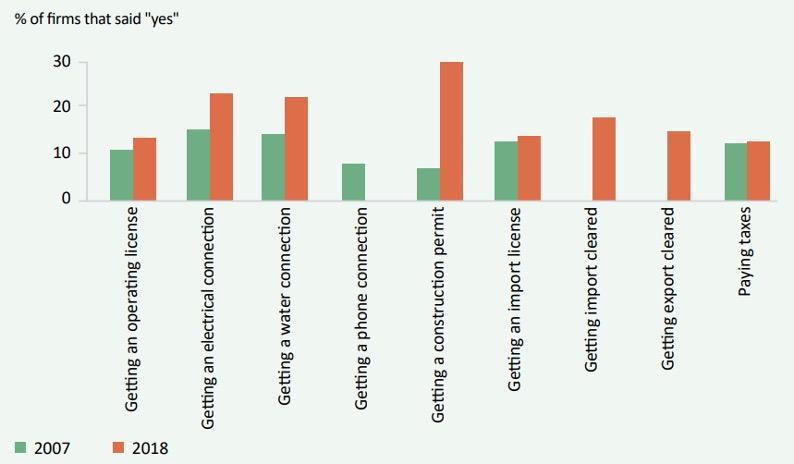

Public procurement is considered a high-risk area in the energy sector in Mozambique, where bribery and illicit payments to political officials to secure contracts are widely reported. A 2019 study by the World Bank found that 13% of firms across the economy reported paying illicit bribes or attempting to secure a government contract in the previous year (World Bank 2019: 8):

Figure 2: Responses to the World Bank survey (one in 2007 and then in 2018) asking companies if they were requested a bribe in Mozambique:

Source: World Bank 2019.

Companies operating in Mozambique perceive favouritism towards well-connected firms to be widespread among procurement officials (GAN Integrity 2020). Energy companies owned by political figures reportedly often win public contracts without a public tender, for projects such as conducting rural electrification works, replacing power cables, and supplying electrical material (Nhamire, Mapisse and Fael 2019). Inflated government contracts due to corruption are also common (GAN Integrity 2020). Gas was sold to private companies at artificial prices, most of which were reportedly controlled by the ruling factions under the Chissano and Guebuza governments (Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020).

Frelimo interest groups and their privately owned companies act as the gatekeepers of foreign investment by securing contracts with their chosen foreign investors rather than putting out a competitive public tender (GAN Integrity 2020; Yang 2021: 29). This can create a turbulent environment for foreign investors, which was seen during the negotiation process of awarding concession contracts to natural gas in Area 1/4 Rovuma Basin (Yang 2021). Three foreign firms entered into a political dialogue with elite business groups in the hopes of winning the governments favour, however, these groups later fell out of favour with the president, which resulted in the contracts being given to others (Yang 2021: 33).

The contracts awarded to multinationals by the Mozambican government are reportedly shrouded in secrecy (Tundumula et al. 2019). According to estimates by CIP, the Mozambican government does not reveal the full amount of revenues from natural gas production generated by the South African company Sasol, as companies such as Sasol enjoy overly generous contractual clauses and do not pay fair or adequate taxes to the revenue authorities (Tundumula et al. 2019: 106). This shows that, on the one hand, foreign multinationals and investors are both dependent on political favour to gain contracts, but that they can also exert significant influence to gain favourable contractual agreements in order to maximise their profits.

The expansion of gas production in Temane in 2012 gave the Mozambican government the opportunity to renegotiate the allocation of commercial gas (Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020). MIREME then allocated this commercial gas to four companies: ENH, Electrotec, the Gas-Fired Power Plant in Ressano Garcia (CTRG), and the Matola Gas Company (MGC) (Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020). Salimo et al. (2020) write that these companies have ‘limited access to financial capacity and technical knowledge to turn gas into electricity’ (Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020). The authors suggest that these companies are linked to different groups in the ruling elite connected to the Chissano interest group that negotiated the original Sasol deal, and to the Guebuza interest group during his two terms (Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020). This could indicate, according to the authors, that the Frelimo elite abused public entities for private gain and used these as a main mechanism for rent-seeking (Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020).

Rent-seeking

Rents include, but are not limited to, the ‘monopoly profits … subsidies and transfers organized through the political mechanism, illegal transfers organized by private mafias, short-term super-profits made by innovators … and so on’ (Khan, 2010: 5 cited in Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020). Reports have been made that energy resource rents are captured by Frelimo-linked domestic business elites who participate in energy-related projects as shareholders and local partners for foreign investors (Macuane et al. 2018 cited in Kirshner et al. 2019). Reports claim that the ruling elite then uses this investment to support its own accumulation and to secure resources for the Frelimo party and key ruling factions (Salimo, Buur and Macuane 2020).

Petty and private-to-private corruption during distribution

The 2019 Economic Update report by the World Bank found that requests for bribes in Mozambique were increasing and that they were most commonly demanded when obtaining a construction permit or electricity connection (World Bank 2019). Demands for bribes have increased compared to 2007, and bribery request rates are above the average that is recorded both globally and throughout sub-Saharan Africa (World Bank 2019).

EDM has reportedly been overbilling in the acquisition of meters and other goods and services, with these expenses being charged to Mozambican citizens (Nhamire, Mapisse and Fael 2019). It is estimated that EDM has spent at least US$10 million annually in overbilling in the purchase of meters, excluding other acquisitions (Nhamire, Mapisse and Fael 2019). Moreover, field research has identified that EDM technicians have demanded ‘financial rewards’ from customers for power restoration services if carried out outside of working hours (Salime et al. 2021). Researchers note that this small-scale corruption is widespread in Mozambique, receiving ‘insufficient attention from policymakers’.

Employees at EDM have also been accused of corruption and theft of electricity in the district of Massinga in the southern province of Inhambane (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre 2023). Whistleblowers claimed that certain parts of the neighbourhood had privileged access to electricity, to the detriment of others (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre 2023). Accusations have also been made by residents that they had to pay bribes to ensure they had electricity access in their homes (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre 2023). EDM has since attempted to sue the journalist who reported on bribes for alleged libel (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre 2023). The Media Institute of Southern Africa has condemned this, calling it ‘intimidation and harassment’ (Business & Human Rights Resource Centre 2023).

Land corruption risks

Land administration has long been a sector that is vulnerable to corruption in Mozambique, and land rights have been seriously hampered by factors such as corruption and government inefficiency (GAN Integrity 2020). Land grabbingcec46600bda1 has been frequently observed in lower income communities and is primarily driven by investments in agribusiness, tourism and the mining sectors (GAN Integrity 2020).

In 2014 the Mozambican government awarded land in Palma, Cabo Delgado to extractive companies (Queface 2023). The transfer of land from communities was done so without community consultations, studies, or the issuing of an environmental licence (Queface 2023). In Mozambique, the Mining Law establishes the right to land to exploit certain products (such as logging and mining), but this stipulates that fair compensation should be paid to any displaced local communities (de Quadros n.d.). However, the government bypassed this and allocated the site in 2015 to Andarko and Empresa Moçambicana de Hidrocarbonetos (the national oil company) (Queface 2023). It is reported that the local government was sidelined during these negotiations, which were largely conducted between central government figures and the foreign investors (Salimo 2020: 104). This left the local government ill-equipped to perform its role in protecting the local community’s interests and rights during negotiations for compensation (Salimo 2020: 104).

As of 2022 over half of the people who were forced to resettle from Palma (which began in 2019) were still waiting for the compensation to which they were entitled (Wensing 2022). This has contributed to major discontent and violence in the area. The natural gas project has also reportedly failed to provide the promised employment to the local communities, many of which have seen their livelihoods vanish (Wensing 2022). Journalists and NGOs who have spoken out about the conflict have reportedly been intimidated, illegally detained, and even tortured or murdered, making it impossible to obtain a clear picture of the situation (Wensing 2022).

There has also been a perception the region of favouritism towards one group over another. Pre-existing grievances between Cabo Delgado Mwani (predominately Muslim) and the mostly Christian Makonde have been exacerbated, particularly due to the latter group having benefited economically and politically from the ruling Frelimo party (Bonate 2024: 22). This reached a tipping point during the election of a Makonde president, which is said to have ‘paved the way’ for Makonde Frelimists to take control of Cabo Delgado’s natural resources, most of which are not located in the historical Makonde areas and are instead inhabited by the Mwani and Makhuwa (Bonate 2024). This resulted in loss of land a revolt from the population, particularly the Muslim Mwani, and has led to major conflict in the area and that threatens to spread to neighbouring provinces (Bonate 2024).

Women are a particularly marginalised group when it comes to land ownership. They are disadvantaged in their access to land and other natural resources as customary land governance systems (which are protected by the Mozambican Land Law) only allow women secondary rights and access to land through a male relative (Land Governance 2018). While the legislation recognises women as co-title holders of community-held land, customary systems do not always follow national laws, and this has resulted in men owning roughly 80% of the community-owned land (Land Governance 2018). This situation risks further marginalising women, particularly when land is already a scarcity in the country, in part due to the number of private large-scale land acquisitions driven by the extractives industry (Land Governance 2018).

The more recent hydropower project, the Mphanda Nkuwa dam, also risks displacing an estimated 1,400 families (Machado 2023). Local communities told journalists that they had not been consulted on the project and have only heard about it through non-official sources (Machado 2023). Community members have said that they will only leave their homes if they are given fair compensation, which, as of 2023, had not yet been determined by authorities (Machado 2023). Moreover, according to scientists and experts, environmental climate impacts and increasingly erratic rainfall risk making the project unviable (Machado 2023).

Finally, charcoal is another energy source that has created risks in land governance in the country. Analysis shows that despite there being legislation in place that officially assures rights and access to land and resources for local communities and promotes community-based management initiatives, these plans and practices are often undermined due to poor governance in the forestry sector (Luz et al. 2015). The forestry sector reportedly has weak capacities, poor supervision, corruption and a lack of transparency (Luz et al. 2015).

Responses to corruption in Mozambique’s energy sector

Increased transparency

In recent, years, the government has taken several steps forward in improving the integrity and transparency of the energy sector in Mozambique. The IMF’s most recent diagnostic report on transparency, governance and corruption dates back to 2019. It notes that a comprehensive legislative and institutional framework to address governance and corruption (which includes business regulation and SOEs) has been adopted in Mozambique and that under this framework, some high-profile cases have been successfully prosecuted (IMF 2019).

The government has also made some progress in improving transparency; for example, an online registry (Flexicadastre) for mining licences has been implemented and is open for public access (IMF 2019: 23). However, not all contracts have been published and the awarding of mining licences has not always been published in a transparent and timely manner (IMF 2019).

In 2012, Mozambique gained ‘compliant’ status through the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI), indicating progress in the governance of its extractive industries (GAN Integrity 2020). It has since achieved a ‘moderate’ score, with key achievements including government engagement in addressing national extractive sector governance challenges (such as the distribution of revenues to the subnational level), increased transparency around SOEs, and improvements in the comprehensiveness of EITI disclosures (EITI 2023: 4). There are still several areas for improvement, particularly in the transparency of energy contracts. The EITI (2023) also concludes that Mozambique has now met the requirement to make all licences and contracts underpinning the extractive activities publicly accessible (EITI 2023).

Nonetheless, the report highlights that there are still some concerns regarding clauses or parts of annexes of contracts that may have been redacted (EITI 2023). The EITI Board determined that the redaction of commercially sensitive clauses for contracts is not permitted (EITI 2023). Environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and environmental monitoring reports were also noted as challenging to access (EITI 2023).

In the final assessment of Mozambique’s progress in implementing the EITI Standard (2023), it was also f0und that transparency around SOEs had improved and that there was a clearer understanding from the general public on the role that SOEs play in the extractive sector (EITI 2023). The reporting on revenue data management had also improved (EITI 2023). It notes that community-level data should be more accessible, and that any potential barriers for use of the information, particularly regarding environmental impact assessments, must be addressed (EITI 2023).

Additionally, progress on beneficial ownership transparency has been limited, which would represent a significant step in addressing corruption risks in the extractive sector (EITI 2023). Therefore, the EITI recommends revising the legal framework and setting up a public beneficial ownership register (EITI 2023), specifically:

- Ensure that there is a legal and regulatory framework in place for collection and public disclosure of beneficial ownership information of all companies applying for or holding extractive licences.

- Request all companies holding extractive licences to disclose beneficial ownership information, including at the application stage. This should also include the identity of any politically exposed persons.

- Introduce adequate assurances to ensure the reliability and comprehensiveness of this data. Undertake regular assessments on comprehensiveness and reliability with regards to all the beneficial ownership disclosures.

- Name entities that have failed to disclose beneficial ownership information (EITI 2023).

Another key recommendation made by the literature concerns the ISDS clauses in Mozambican contracts with multinational companies. Salvatore and Gubeissi (2024) recommend that the government take actions (where possible) to remove ISDS clauses from their contracts and treaties and replace these with alternative dispute resolution mechanisms. They also suggest taking steps to terminate the investment agreements that are currently in force (Salvatore and Gubeissi 2024). In their view, the countries in which Mozambique’s foreign investors are based also have a responsibility to support such actions, especially as they can remove references to ISDS from their own treaties (Salvatore and Gubeissi 2024).

Stronger regulatory oversight

Some changes have been implemented to strengthen the oversight of the energy sector. In July 2022, the Electricity Law, the legal instrument for electrification in Mozambique, was updated (Lopes 2024). This law aims to reflect the social, technical and financial dynamics in Mozambique, with an emphasis on renewable energy and increasing private sector participation in the supply of electricity (Lopes 2024). It also determines the entities responsible for processing concession applications for the import and export of electricity through ARENE, and establishes an Energy Cadastre, which contains information on energy supply or provision of energy services (360 Mozambique 2022). This updated law was generally well received, particularly in terms of improving transparency and increasing energy connections (360 Mozambique 2022).

Howe et al. (2024) also notes that the Mozambican government is seen as taking a proactive approach to developing legal and regulatory reforms, particularly regarding green energy (Howe et al. 2024). This includes the development of ARENE as an independent authority (Howe et al. 2024). However, the expansion of ARENE’s responsibility to include the off-grid sector means that it is stretched, as it is a new institution, and as of 2022, it was not yet operating at full staffing capacity (Howe et al. 2024).

To address this and other ongoing challenges, the Africa Energy Portal recommends that further measures be taken to limit the involvement of the executive branch in the development of ARENE’s long-term strategies, such as requiring the regulator to report directly to the legislature (ERI 2022), which could help preserve its operational independence and reduce opportunities for political corruption and rent-seeking. ERI (2022) further recommends prohibiting the appointment of people who were previously employed by regulated entities as ARENE commissioners to curb undue influence associated with the revolving door. Other recommendations include that the government should also impose environmental, social and governance (ESG) requirements on the private sector (Deloitte 2024).

The management of the Sovereign Wealth Fund

By 2028, it is predicted that revenues from natural gas sales will enhance the country’s debt sustainability generate funding for investments in the country (World Bank 2023). For the benefits of these revenues to be enjoyed by the wider population, the World Bank recommended in their Country Climate and Development Report that Mozambique establish a Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF) to ensure the sound management of natural revenues, which would include effective oversight mechanisms to provide transparency and accountability (World Bank 2023).

As of 2024, the Mozambican parliament successfully passed a bill to establish a SWF that will cover all natural gas revenues and revenues from any future gas discoveries (Sarmento 2024). Its objectives are to help the country’s economic and social development (Sarmento 2024). The SWF has several important controls to ensure transparency and accountability, including:

- A Transitory Account, which will be located at the Central Bank, will ensure revenues are accounted for and managed transparently.

- The Santiago Principles3878dd85507c were applied in the design of the SWF.

- The SWF may not be used to provide guarantees for the contracting of loans by the state or be used to pay debts or the financing of political party activities.

- A monthly report will publish the amounts received and transfers made to and from the account. The Administrative Court will audit the government institutions involved in the management of the SWF, and an independent international auditor will conduct the audits and publish the financial statements.

- A supervisory committee (including members of civil society) will be established to supervise the management of the SWF (Sarmento 2024).

The IMF considers the SWF an ‘important step toward ensuring transparency and sound management of natural resource wealth’ in Mozambique (Club of Mozambique 2024). It is hoped that this mechanism will safeguard the profits from the natural resources sector from corruption as well as preventing the state from going further into debt (Club of Mozambique 2024).

Asset recovery and sanctions

The Mozambican government has recently made improvements in its asset recovery framework in through the decree for the Management of Seized or Recovered Assets in Favour of the State and the setup of a new asset recovery office (Prusa 2020; Club of Mozambique 2024). This has led, for example, to the 2024 cooperation between the Vice-Attorney General of Mozambique and Jersey’s Attorney General which led to the return of £829,500 to Mozambique in an asset return arrangement (Government of Jersey 2024). The funds had been seized from a Mozambican national who had previously held high-level public positions and had placed bribes received for public contracts into a trust in Jersey (Government of Jersey 2024). Further recommendations put forward by the Civil Forum for Asset Recovery (CiFAR) are for the international community to exert additional external pressure through imposing sanctions, including secondary sanctions, on international business entities implicated in domestic Mozambican corruption scandals to send a clear message that there is no impunity for corruption in Mozambique (Prusa 2020: 10).

Improved dialogue with local communities

A study into the natural resource sector in Mozambique found that information campaigns were effective in raising community awareness and knowledge about natural gas discovery and can increase accountability while simultaneously decreasing the likelihood of violence (Armand et al. 2019). The information campaigns were delivered to local leaders and citizens, followed by meetings with citizens to discuss public policy priorities for the community in relation to the future of natural gas projects (Armand et al. 2019). The authors put forward the recommendation that the government engage more effectively with local communities.

The EITI assessment (2023: 9) observed based on stakeholder consultations and available evidence that opportunities for citizen participation differ widely from region to region. In Maputo, civil society organisations (CSOs) have opportunities to undertake advocacy related to ongoing reforms in the extractive industries (EITI 2023: 9). However, in part due to the ongoing conflict, in areas such as Cabo Delgado, opportunities for citizen participation are limited (EITI 2023: 9). The EITI (2023: 14) also therefore recommends that communities across the country be informed and empowered about their rights and benefits.

The International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED 2002) recommends that power imbalances between local communities and multinational companies be addressed. To do so, decentralisation of some of the decision-making has proved useful in several countries, with local governments taking on important roles in overseeing agreements (IIED 2002). Civil society groups can also be important mediators to facilitate the flow of information between government, companies, and local communities (IIED 2002: 209). Improved dialogue and consultation with communities could result in better distribution of wealth among communities and reduce land grabbing. An independent ombudsman may also serve to act as a third party to help resolve land-related disputes.ded78ee8d640

Finally, in terms of the green energy transition, the development of community energy projects could increase investors’ confidence (through mitigating the risks of potential conflict) in the sector as well as improve local ownership of energy sector projects (Howe et al. 2024). Investment in local ownership and skills, particularly in green energy production, is considered an important step in Mozambique’s energy future (Deloitte 2024) and in providing off-grid solutions to rural communities.

A responsible shift towards renewable energy sources

Gaventa (2021) considers that the ‘gas for development’ expectations for Mozambique have failed and have instead led to conflict and instability. The costs for wind, solar, and other renewables are now cheaper than new gas generation in most regions, which will change the future of gas demand (Gaventa 2021: 13). The author recommends that the country look towards renewable energy sources instead to prevent over-dependence on gas (while recommending caution with carbon credits from forestry projects as these may further exacerbate existing land conflicts).

Therefore, Mozambique’s international partners, donors and financial institutions should re-evaluate their assumptions about the purported development benefits of gas and instead redirect their financial support to more inclusive and sustainable economic sectors (Gaventa 2021: 28). These suggestions are also reflected in the BTI (2024: 43) report, which recommends that the Mozambican economy diversify, and move away from natural resource extraction and megaprojects to achieve sustainable growth. Investment in renewable energy sources is considered particularly important for the development of rural areas (Cristóvão et al. 2021).

- The energy sector is a broad sector. This Helpdesk Answer looks at the extraction of natural resources to produce energy, renewable energy sources, and the provision of electricity that is generated from these sources and how it is distributed and transmitted throughout the country.

- This categorisation refers to the World Bank’s country and lending groups classification.

- For further reading on the ‘hidden debt scandal’, see The Costs and Consequences of the Hidden Debt Scandal in Mozambique (2021).

- However, since the 1980s the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) imposed free market policies and privatisation which some argue has helped lead to the current situation (Hanlon 2022).

- For more information on the consequences of the corruption scandal see Costs and Consequences of the Hidden Debt Scandal of Mozambique (2019).

- According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (n.d.) definition, governments provide official export credits through ECAs in support of national exporters competing for overseas sales. These can be government institutions or private companies operating on behalf of governments.

- Land grabbing can be defined as the control of larger than typical amounts of land by any person or entity through any means for purposes of speculation, extraction, resource control or commodification at the expense of local communities and their food sovereignty and human rights (Baker-Smith and Attila 2016).

- The Santiago Principles were developed by the International Working Group of SWFs and aim to promote transparency, good governance and accountability in SWF activities (IFSWF n.d.).

- For more detail on how to address conflict between local communities and mining companies, see IIED’s report on local communities and mines.