Background

Before delving into the subject of corruption in the diamond sector in Angola, it is helpful to provide a brief overview of the Angolan political context and overall situation with regards to corruption. Moreover, a schematic look at the diamond industry’s supply chain and key actors illustrates the multinational nature of the sector and the range of actors involved across different jurisdictions.

Brief history of Angola

Angola is currently the fourth largest producer of diamonds worldwide, with 9.3 million carats produced in 2021 (Hollands 2022). The Minister of Mineral Resources, Petroleum and Gas, H.E. Diamantino Azevedo, has recently stated that the country could become the second-largest producer of rough diamonds globally by 2030 (Silva 2022). New exploration and discovery, considerable regulatory improvements and increased financing from the government as well as private sector actors (such as global diamond companies, including De Beers) are the factors being cited by the minister for Angola’s potential to become an even more significant diamond producer (Hollands 2022; Silva 2022; Garnett 2022).

Natural resources, including diamonds, are known to play a role in armed civil conflict (Gilmore et al. 2005). This holds true in Angola’s history as well. The country achieved independence from Portugal in 1975, but a long civil war that lasted until 2002 ensued between the armed liberating powers (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 4).

The two main forces vying for control after the departure of the Portuguese were the Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), under José dos Santos, and the National Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA), headed by Jonas Savimbi (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 4). Given that the Cold War was ongoing at the time, the civil conflict became a proxy war with the MPLA being supported by the Soviets and Cuba, and UNITA by South Africa’s apartheid regime, the United States and other Western countries (Bonnerot et al. 2022; Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 4; Soares de Oliveira 2007).

The MPLA, which “brutally repressed internal dissidence”, took control of the capital after independence, established a de facto government and was later legitimised by elections in 1992c36588f7e3e1 (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 4). UNITA, the rebel group, controlled nearly half of Angola by 1993 – including territories of Cuango, Cubango and the Lundas Valley, which were rich in diamonds. Once funding for the civil war dried up from external sources, UNITA turned to the diamond trade to fuel its fight against the MPLA by using proceeds from selling rough diamonds to obtain weapons (Harvey 2002; Hoekstra 2019). The terms blood diamonds and conflict diamonds6d8eea3ac7f2 were made common during the “gory conquest” for the stones by UNITA in Angola and other countries, such as Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia and Sierra Leone (Global Witness n.d.).

The bloody civil war that lasted nearly 30 years and claimed the lives of an estimated 1 million people at least, while displacing another 4 million, came to an end in 2002 when Savimbi was killed by government troops (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 4; Bonnerot et al. 2022).

Since the end of civil war in 2002, Angola has maintained a reasonable degree of political stability, if not political competition (World Bank 2022). The MPLA “recast itself as the party of stability and peace”, and during the first post-war elections in 2008, it used “the privileges of incumbency – access to state funds, media control, intimidation of the opposition and electoral manipulation – and successfully painted the spectre of a return to war if the opposition were to win” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 5).

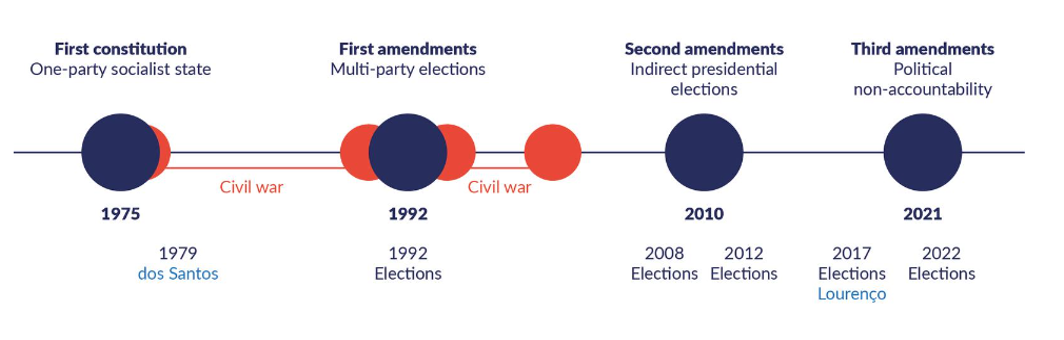

Having gained an absolute majority in parliament with 82 per cent popular vote in 2008, the MPLA also managed to then push through a constitutional amendment in 2010 that did away with direct presidential elections (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 5; Freedom House 2022). Instead, the head of the majority party/coalition would be declared president – without an approval process by the elected legislature (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 5; Freedom House 2022). This move to an idiosyncratic/unique “parliamentary-presidential system” resulted in power being concentrated in the hands of the president, while parliament’s oversight was reduced (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 5). Such a move allowed President dos Santos to “consolidate his grip on power”, permitting “even more deliberate monopolisation of economic assets” by the dos Santos family (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 5).

Figure 1: Instances of constitutional amendments in Angola.

Source: Amundsen (2021).

After dos Santos’s almost four-decade long rule, João Lourenço of the MPLA became president in 2017 (Pecquet 2022). With anti-corruption being a major theme of president Lourenço’s initial rhetoric, he moved – to the surprise of many – against the interests of the dos Santos family, dismissing dos Santos’s children Isabel (accused of embezzling funds) and José Filomeno from their positions of the head of the Sonangol oil company, and Angola’s sovereign wealth fund, respectively (Pecquet 2022; Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 5).

Nevertheless, the general public opinion is that the “president [is] using the fight against corruption as a tool against political rivals” (Pecquet 2022). The Bertelsmann Stiftung (2022: 10), for instance, reports concerns about the diversity of Angolan media as several private news outlets have been confiscated and nationalised as a part of Lourenço’s corruption clean-up campaign. The report adds that Angola remains “dependent on oil revenues and is held hostage to entrenched politically connected private interests” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 5).

In 2021, the Angolan constitution was once again amended. The move took place without proper civil society or citizen participation and was strongly criticised by the opposition. The results of the amendments, include, among others, a “political non-accountability clause”, which states that, in the case that a parliamentary investigative committee finds any wrongdoing, they cannot call for the resignation of the responsible minister but only “inform” the president on what they have found (Amundsen 2021).

According to Freedom House (2022), the government continues to systematically repress political dissent with regular crackdowns on civil society actors and human rights groups. Angola is deemed “not free” with a score of 30/100 by the organisation’s Freedom in the World Report 2022.

The country’s politics is characterised by rampant corruption, violation of due process, a culture of impunity, and a lack of checks and balances combined with limited institutional capacity (Freedom House 2022; US Department of State 2021: 2). Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) 2021 rank for the country is 136/180 with a score of 29/100.

Angola serves as an example of a country afflicted by the “resource curse” wherein a “vast array of societal, economic, and political woes […] proliferate alongside a sudden increase in natural resource-based wealth” (Bassetti et al. 2020). The oil and mining sectors are in particular deemed high-risk areas for corruption in the country (GAN Integrity 2020; Schock 2017).

According to GAN Integrity’s Risk and Compliance Portal (2022), “clientelistic networks generally govern the way business is conducted in Angola with many Angolan companies functioning as front organisations for government officials whose integrity and accountability are frequently questioned by observers”.

The country has signed and ratified the UN Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) and has signed the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption (AUCPCC). It has a fairly comprehensive anti-corruption framework that is comprised of measures found in the penal code, the public probity law, the contracting law and the law on the criminalisation of infractions related to money laundering. However, the de facto implementation of these laws remains limited (GAN Integrity 2022).

The country’s latest available UNCAC review of implementation report (2017) even makes notes of some areas to strengthen the legal anti-corruption framework. These include criminalising bribery in accordance with the convention, consider criminalising the abuse of function when failing to perform an act, and trading in influence, among others (CAC COSP 2017: 7).

Understanding the diamond sector

Diamonds are universally known precious stones that not only hold value for the jewellery business but have far-reaching industrial uses, including in sawblades and drill bits (Mineral Council South Africa 2022). They have certain distinguishing features that make them a “seemingly ideal currency for organised crime” and “a rebel’s best friend” (Tailby 2002: 1; Østensen and Stridsman 2017: 21).

For instance, diamonds are (Tailby 2002: 1):

- small and durable (thus easy to conceal and smuggle)

- of value (with a significantly high value-to-weight ratio), acting as a type of “compressed cash”

- readily exchangeable for money or other items (such as drugs or arms)

- practically untraceable once they are polished

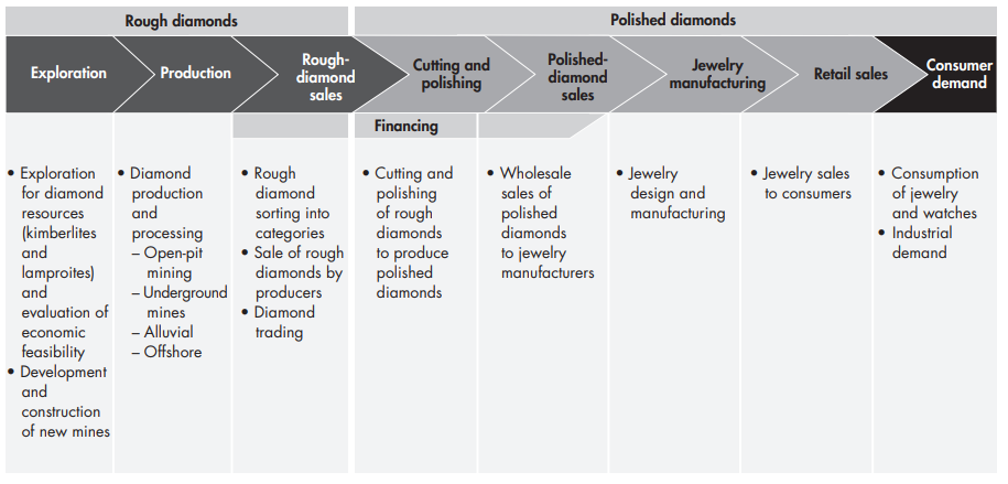

Bringing naturally formed diamonds from the earth to consumers involves several stages, including exploration, mining, trade by local diamond dealers and transfer to larger cities for sorting, selection and certification, transportation across borders, followed by trade of rough diamonds at the diamond bourses (such as London, Antwerp, Ramat Gan), then cutting and polishing, jewellery manufacturing and finally retailing. This process is also dubbed the diamond pipeline (World Diamond Council n.d.; Bain & Company 2011: 19; Siegel 2020).

The Global Diamond Report 2013, analysing the value chain ofthe diamond sector, demonstrated that price of diamonds rises considerably as they move through the pipeline from the mine to the final market, “nearly quintupling over the course of the journey” (Bain & Company 2013).

Figure 2: The various stages of the diamond value chain that showcases the different processes involved.

Source: Bain & Company (2011: 19).

The high retail value of diamonds is partly derived from their perceived rarity, although this is somewhat artificial given that diamond producers limit supply to keep prices high. De Beers, established in 1888, enjoyed a monopoly over diamond mining, trading and retail from 1938 until the 21st century.78577fd9786e With this control over diamond supply, the company could influence the distribution, and drive-up diamond prices. Simultaneously, successful advertisement campaigns for the sector made the purchase of diamonds engagement rings a social norm (Friedman 2015; Loose Threads 2020). Apart from De Beers, currently, diamond mining is still controlled by a handful of large companies including Alrosa,174dc10e3b7a Debswana Diamond, Rio Tinto and Dominion Diamond (NS Energy 2021).

Big diamond mining companies and traders are some of the key actors in the value chain, which also includes other players including miners, dealers, craftspeople and jewellers, as well as governing agencies in national contexts, national and international financial institutions, and international certification and regulatory bodies (Bain & Company 2011: 19-20; FATF 2013). Each stage of the value chain has its own set of actors that “vary greatly between different countries and even between different mining regions within the same country” (Priester et al. 2010: 4). For instance, the major actors involved in alluvial mining include labourers (diggers, gravel transporters, washers), gang leaders (group chiefs), site chiefs (mine managers), title holders, landowners, buyers (intermediaries, exporters), financers, official mining companies collaborating with artisanal miners, jig owners/operators, water providers, earth moving service providers, dredge owners, hirers and sellers of equipment, cooperatives, government/local mining departments. All of these actors have distinct relations to others as well as differing sources of income and interests (Priester et al. 2010: 4).

Some of the main diamond producing countries include Russia, Botswana, Canada, Angola, South Africa, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and Namibia, (King 2022). On the consumption side, the main importing countries as of 2020 included India, the US, Hong Kong, Belgium and the United Arab Emirates (OEC 2020). However, it ought to be noted that there are often discrepancies noted in worldwide diamond import/export figures. For instance, in 2016, the reported worldwide total for diamond imports was US$117.4 billon, however, the export total was US $127.6 billion. “Differences in classification concepts and detail, time of recording, valuation, and coverage, as well as processing errors,” or the “cost of doing business” are often cited as reasons for such inconsistencies (Raul 2018; IMF n.d.). Trade based money laundering (TBML) in the form of “overvaluation of the price of the traded goods” or “misrepresentation of transactions as import and export of diamonds”, among others, are also known to take place (FATF 2013: 107).

As mentioned above, diamonds have also been used by armed groups as a means to fund conflict in several countries, such as Angola, Central African Republic, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Liberia and Sierra Leone (Global Witness n.d.). The diamond trade, especially at the mining level, often involves severe human rights abuse (HRW 2018b). Likewise, corruption is reportedly common in the industry, enabling practices such as illicit mining and commodity mispricing, among others, (OECD 2016: 84; Siegel 2020).

To put an end to “conflict/blood diamonds”, the Kimberly Process (KP) was created to require certain “minimum standards” when trading in rough diamonds (Kimberly Process 2022). However, the process has been criticised for being inadequate and being a “perfect cover story for blood diamonds” (Rhode 2014). The Kimberly Process is discussed in detail in the upcoming sections.

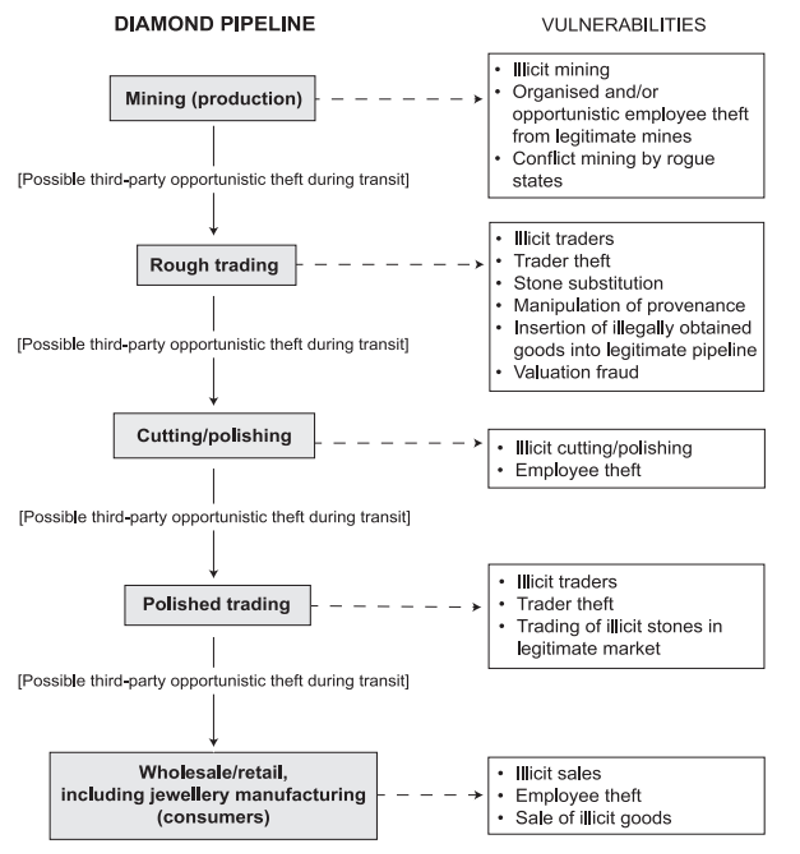

There are various corruption risks that can emerge at different stages of the diamond pipeline, such as undue influence in issuing mining and trade licences, illicit mining, theft, smuggling, valuation fraud and stone substitution, among others. The following infographic suggests a few illustrative risks that could emerge.

Figure 3: Diamond pipeline and its vulnerabilities to illicit activity.

Source: Tailby (2002: 2).

In a report on corruption in the extractive sector, the OECD (2016) highlights detailed corruption risks for each stage of the extractive value chain that can be applied to the diamond sector as well. Overarching corruption risks include (OECD 2016: 15-17):

Gaps in the anti-corruption legal and judicial system: such as weak anti-corruption legal and institutional frameworks, legislative gaps for key anti-corruption provisions such as whistleblower protection, and judicial and regulatory shortcomings, among others.

Discretionary power and high politicisation of decision-making processes in the extractive value chain: such discretionary powers can be seen, for instance, in the process of granting mining/extraction licences, approving environmental impact assessments, revenue collection and procurement of goods and services, among others.

Inadequate governance of the extractive sector: stemming from either a lack of or inadequate separation of roles and responsibilities between administrative, regulatory and supervisory functions. Moreover, a lack of independence and accountability in monitoring and oversight functions as well as the lack of civil society/local community participation can exacerbate corruption risks along the extractive value chain.

Gaps and discrepancies in corporate due diligence procedures: resulting from insufficient anti-corruption compliance and due diligence procedures applicable to employees, subsidiaries, business partners and intermediaries along the extractive value chain.

Opacity on beneficial ownership: with ever increasing complex multi-layered business arrangements across different jurisdictions involving shell companies and professional enablers, one of the largest corruption risks stems from the lack of access to information on these structures, including beneficial ownership information.

For more details on the corruption risks under each stage of the extractive value chain please refer to theOECD Report - Corruption in the extractive value chain: Typology of risks, mitigation measures and incentives (2016).

Given the vulnerability of diamonds for use in illicit activity, there are several approaches that can be deployed to enable revenue management, transparency and accountability, which are discussed further in the section on anti-corruption approaches below. These illustrative approaches, apart from covering certain overarching themes that would apply to the global diamond industry, are also adapted to the Angolan context.

Corruption in the Angolan diamond sector

The main methods for mining diamonds in Angola are industrial open pit mines on volcanic pipes (known as kimberlite), and alluvial mining of diamonds that are washed out from the pipes and are found deposited in water bodies such as riverbeds (Rodrigues 2016). While kimberlite mining is the most profitable type for large scale mining, alluvial mining also operates on a substantial scale in the country and was the starting point for diamond mining in Angola (Rodrigues 2016).

Alluvial tracts are found mainly in the provinces of Lunda North and Lunda South and the northeast of the country (Cauanda Xavier 2017). The main kimberlite diamond mines include Catoca,3841124f5716 Luaxe and Camafuca-Camazambo (Energy Capital & Power 2022).

Emprêsa Nacional de Diamantes (Endiama) is the state-owned diamond company of Angola. However, there are several state-owned and private joint ventures for diamond mining and trade – including with De Beers and Alrosa. Preceding the creation of Endiama, Diamang (a Portuguese-run colonial mining company) had the monopoly to explore and mine diamonds in the country (Chambel et al. 2013: 7-8).

The general vulnerabilities of the industry to corruption are compounded by certain features of Angola’s political economy. A few cases are discussed below.

Elite capture of the Angolan diamond industry

Observers see nepotism, cronyism, and patronage as pervasive in the oil and diamond sectors in Angola (GAN Integrity 2020). While the power and control of the political elite1c04964a8300 over key Angolan oil and diamond businesses have been curtailed in recent years after President Lourenço came to power, this has not resulted in major structural change, with “many Angolans [worrying] that old networks of elites are simply being replaced by new ones” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 9, 30). Bye, Inglês and Orre (2021) note that, apart from the “selective exclusion of a few large economic predators, and selective combat of corruption impunity…there has been no threat against the maintenance of power structures”.

Under Lourenço, the top hierarchy consists of MPLA old-timers (many of whom were “rehabilitated” by the new president after being sidelined by dos Santos), as well as other “well-known allies and close relatives” (Bye, Inglês and Orre 2021). Only a select number of new people have been admitted to this elite group and “there have been no openings for people from civil society or from the very limited private sector outside of the MPLA in Lourenço’s inner circle” (Bye, Inglês and Orre 2021).

The release of the ‘Luanda Leaks’ documents, provided to the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) by the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa (PPLAAF), reveals several examples of elites having captured the diamond sector in the country (Freedberg et al. 2020).

President dos Santos was known to “give public assets to family and friends” and treat the country “like his personal farm” (Freedberg et al. 2020). After forces loyal to dos Santos captured the country’s largest diamond mines during the civil war, he set up the Angolan Selling Corporation (ASCORP) with an exclusive licence to market Angolan diamonds. While the Angolan state held a majority stake in ASCORP, Isabel dos Santos (dos Santos’s eldest daughter) and Tatiana Kukanova (dos Santos’s former wife and Isabel’s mother) owned 24.5% of it through another company – Trans Africa Investment Services (Freedberg et al. 2020; Bassetti et al. 2020).

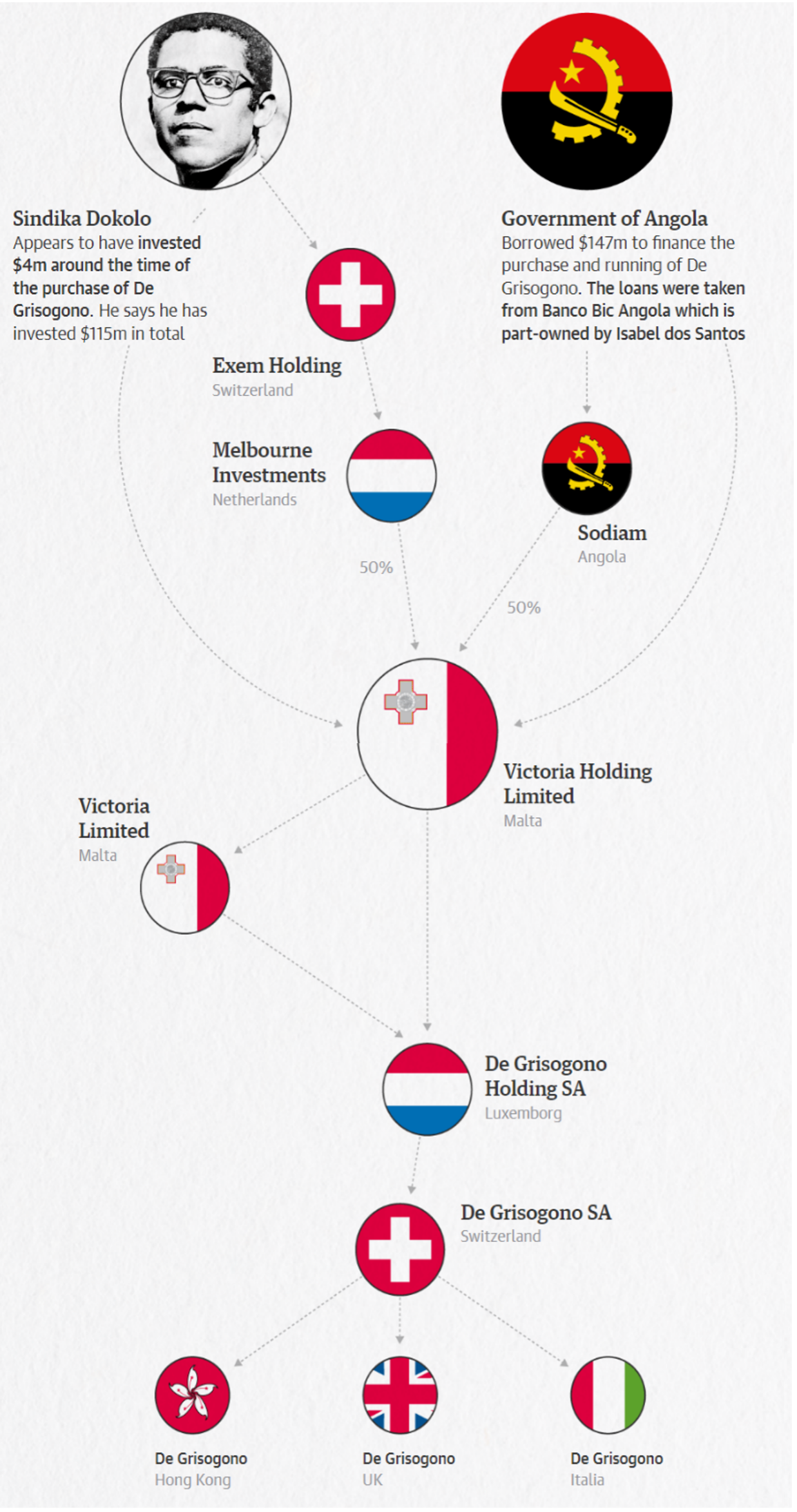

Apart from exercising control over diamond mining, Isabel dos Santos and her husband Sindika Dokolo were also involved in other stages of the diamond value chain. Dokolo wanted to “create a company that would control Angola’s diamond industry from mining to polishing to retail” (Freedberg 2020). He partnered with Sodiam, one of Angola’s government-controlled diamond enterprises, set up two shell companies in Malta, and through these they bought a controlling stake in De Grisogono – a Swiss luxury jeweller (Freedberg 2020; Bassetti 2020; Osborne and Barr

2020; Marques de Morais 2014b). The purchase was made possible through financing via a bank1b8c48f5b510 partially owned by Isabel dos Santos, illustrating the nepotistic connections that facilitated such high-level corruption (Bassetti 2020).

While the deal was supposed to be a 50/50 split between Dokolo and Sodiam, “documents suggest that in practice, however, the Angolan state appears to have provided most, if not all, of the funds that made the purchase of De Grisogono possible”, while Dokolo maintained “full control of the management” (Osborne and Barr 2020; Freedberg 2020; Verde 2016).

The debt incurred by Sodiam for the purchase had an interest rate of 9% and was guaranteed by the Angolan treasury. Thus, while dos Santos reportedly benefitted from the interest earned from the state-owned company’s payment back to the bank, Isabel dos Santos and Dokolo “had no risk of losses should things have gone wrong and Sodiam found itself unable to repay its loans” (Osborne and Barr 2020). Isabel was allegedly able to siphon revenue in multiple ways, earning high rates of interest from Sodiam’s bank payments while getting a share in De Grisogono much greater than their investment contribution (Bassetti 2020).

In 2020, the deal between Dokolo and Sodiam was labelled as “fraudulent” by an Angolan court (Fitzgibbon 2020). Within Angola, Isabel dos Santos’s involvement in the state-owned oil and diamond sectors were well known, though the Luanda Leaks investigation by ICIJ was able to showcase on international stage the extent of her alleged corruption (Bassetti et al. 2020). It was found that:

“Dos Santos, her husband and their intermediaries built a business empire with more than 400 companies and subsidiaries in 41 countries, including at least 94 in secrecy jurisdictions like Malta, Mauritius and Hong Kong.Over the past decade, these companies got consulting jobs, loans, public works contracts and licenses worth billions of dollars from the Angolan government (Freedberg et al. 2020)”

Figure 4: Infographic tracing the purchase of stake in De Grisogono via Maltese shell companies.

Source: Osborne and Barr (2020).

Isabel dos Santos has been sanctioned by the US69a683baabca for “significant corruption”, and her assets have been frozen in Angola after being charged with “embezzlement and money laundering” by the Angolan attorney general (Fitzgibbon 2022; Dolan 2021). The total losses to the Angolan government as a result of Isabel dos Santos’s alleged corrupt activities stands at US$1.1 billion (Dolan 2021). Isabel dos Santos has denied all wrongdoing, and currently lives in Dubai and London (Dolan 2021). Dokolo, who was also facing corruption charges died in a diving accident in Dubai in 2020 (Reuters 2020).

While Isabel dos Santos provides the most glaring example of elite capture of Angolan state-owned natural resource enterprises, she was by no means the only player. Other close allies of her father, Nascimento and Dias (who go by Generals Kopelipa and Dino), who were appointed as generals under President dos Santos, are also accused in the US of siphoning off public funds for their personal benefit and are on the sanction list as well (Dolan 2021; Maussion 2021).

It ought to be noted that while the Luanda Leaks propelled graft in the Angolan natural resources sector onto the international stage – it was years of drawing attention to the corruption of the dos Santos regime by local journalists and activists such as Rafael Marques de Morais that eventually made these revelations possible. Marques, and others, used Maka Angola to report on the corrupt activities of various actors (including the dos Santos family, Angolan generals and the attorney general, among others). Such reporting often came at great personal cost and risk. For instance, Marques was had several criminal complaints from the Angolan generals and companies that he exposed in his book Diamantes de Sangue: Tortura e Corrupção em Angola (Blood Diamonds: Torture and Corruption in Angola) and other works (Maka Angola 2014; Marques de Morais 2014a; LUSA 2015).

Mispricing in commodity trading

Elite and kleptocratic access and control of major state-owned enterprises (SOEs) resulted in other forms of corruption, such as illicit commodity trading, taking place. For instance, it is alleged that Isabel dos Santos and her husband purchased diamonds from the Angolan government at below market prices. Such an act would amount to the bypassing of typical commodity trading practices by trading the diamonds at manipulated prices for the personal benefit of the dos Santos family (Bassetti et al. 2020).

Illicit mining, trade and smuggling

In the colonial era, garimpo (illegal artisanal mining) was a prevalent, albeit scattered activity, due to surveillance by the Portuguese controlled extractives company Diamang. During the civil war, UNITA’s use of diamonds as their income resulted in higher levels of artisanal mining and attracted people from the neighbouring war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) (Rodrigues 2016). Such activities gave rise to an intricate web of miners and traders with international contacts and resulted in a complex scheme of profit distribution among all those involved. Garimpo mining still persists and consists of “common people trying to earn a life in a place where [employment] options are very scarce” (Rodrigues 2016).

Given that illegal mining is rampant in the country, the police regularly seize mining sites as a part of the government’s “operation transparency” that aims to clean up the diamond sector, among other things (Nyaungwa 2020; Leotaud 2018). In 2018, diamonds worth US$1 million were seized as a part of these operations that also resulted in the deportation of 380,000 migrants (Leotaud 2018). As stated, a majority of these miners come from neighbouring DRC. Diamond smuggling was also commonplace, and between 2003 and 2006, the country deported 250,000 smugglers (Jeffay 2020).

Corruption enabled human rights abuses

The diamond mining process in Angola is associated with human rights abuses (US Department of State 2021: 16; 33; Freedom House 2022; Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 22). Human rights activists in the country have accused soldiers from the national army, police, and private security guards of torturing and killing civilians to gain control over diamond mining operations (HRW 2018; Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 11; Maka Angola 2016).

Indeed, many mining areas and their inhabitants are essentially under the de facto control of private security forces, “though these are by and large owned by generals of the national army”, which illustrates “how emmeshed corporate and state interests are, mutually protecting and safeguarding each other” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 6). Other researchers looking into the Angolan diamond industry, such as Jourdain de Alencastro (2014) contend that the “diamond sector has functioned historically as the conduit through which the state projects its power and secures its interests in a strategic but hostile territory”. Such systems are entrenched by “privatised governance that has existed in the Lundas for more than a century” (Jourdain de Alencastro 2014).

In diamond mining districts, local people are known to face other challenges as well. For instance, several thousand inhabitants of Lunda Norte faced the risk of “state-sponsored famine” due to the “systematic destruction of hundreds of food crop plantations” by the Angolan diamond mining conglomerate, Sociedade Mineira do Cuango (SMC), and “compulsory removal of the villagers and destruction of their homes, cash crops and vegetable gardens” by local MPLA administrators (Marques de Morais 2016). Those affected also claimed of getting inadequate compensation (Marques de Morais 2016).

Potential corruption risks in licences for mining

Mineral resources, like diamonds, are owned by the Angolan state, and private investors can be granted mining rights by Endiamafd0d13815211 (Santos Vitor et al. 2019).

The various kinds of licensing titles include (Santos Vitor et al. 2019; Viana and Afonso Fialho 2020):

- prospecting/exploration title: for the identification, prospecting, research and evaluation of mineral resources

- mining title: for the mining of natural resources

- mining permit: for the exploration or mining of resources used in civil construction.

- mining ticket: for artisanal mining.116a90fd4af4

Moreover, licences are granted through a public tender procedure or even directly, following a request by the applicant (Santos Vitor et al. 2019). Angola’s public tendering process is reported to feature corrupt and collusive practices that involve kickbacks, and public funds being “very commonly diverted to companies, individuals or groups in an illegal manner” (GAN Integrity 2020). The award mining rights in the extractive value chain is particularly vulnerable to corruption (OECD 2016: 37). Thus, diamond mining processes such as tenders for licensing in the Angolan context can face corruption risks (as was seen in the earlier case of ASCORP).

Table 1: Potential corruption risks at key stages of the diamond value chain in Angola.

| Stage of diamond value chain | Potential corruption risks | Overarching corruption risk |

| Exploration | undue influence, collusion, kickbacks in public tenders for exploration titles; use of kleptocratic and patronage networks to distribute exploration titles | elite capture of diamond pipeline |

| Mining | corruption in licensing processes; corruption enabled human rights abuses; illegal mining | |

| Rough diamond trading | commodity mispricing, illegal smuggling; falsification of Kimberley Process Certification |

Ongoing reforms in the diamond sector

In a bid to make the diamond sector more attractive to foreign investors, President João Lourenço launched several initiatives and overhauled regulatory frameworks governing the sector (Kedem 2021). For instance, additional sales channels such as producer preferred buyer channele83735064d4c and tender or auction channel were created (Nyaungwa 2022).

The major shift came from producers being permitted to select their own buyers. Previously, producers had to choose from a limited pool of buyers that were pre-approved by the Angolan state. This allowed buyers to pay prices below the international market rates, dissuading foreign producers from investing in the country (Nyaungwa 2022).

To further boost the commercialisation process, the first diamond auction in the country was held in 2019. It used an electronic system to record bids from interested parties and help to ensure confidentiality (Eisenhammer 2019).

The Geological Institute of Angola has a new headquarters with high-end facilities for testing mineral samples. A new Surimo’s Diamond Development Hub is being constructed in the Lunda Sul province. The centre is set to house new diamond cutting factories and two training centres specialised in diamond mining, evaluation and polishing. The idea is also to create employment for the youth in the surrounding areas (Kedem 2021).

The National Agency for Mineral Resources has also recently been established. The body is tasked with regulating, inspecting and promoting diamond mining, while engaging in a continuous dialogue with the business community (ANGOP 2020; Xinhua 2020).

To tackle illegal immigration, smuggling and tax evasion, the National Police Force introduced ‘Operation Transparency’. Within six months of its launch, 455,022 insufficiently documented “illegal immigrants” were said to be “voluntarily” repatriated (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 22). Illegal miners from neighbouring countries were also deported as a part of this operation. Human rights organisations claim that these “sweeps were accompanied by police violence, and also included people who had been recognised as refugees in Angola” (Bertelsmann Stiftung 2022: 22). Lucapa, a well-known area for subsistence artisanal mining, experienced violence as a result of the police crackdown on Congolese migrants working in the illegal diamond mines. Reporters claim, “ethnic violence, police action and looting forced half the city to flee to the border and into DRC” (Eisenhammer and Paravicini 2018).

Despite the concerns of human rights advocates, the reforms seem to have generated greater confidence on the part of international investors, as large diamond companies, including De Beers, have recently applied for diamond exploration in the various parts of the country (Kedem 2021; Nyaungwa 2022).

Anti-corruption approaches

There are some standard measures that can be adopted at various stages of the diamond pipeline to address vulnerabilities to corruption and other illicit activity. However, context is key when applying anti-corruption reforms to specific corruption challenges. Apart from a thorough understanding of the sector in focus, knowledge of the political-economy environment, actors and middlemen involved, is critical to the success of anti-corruption interventions.

Any high value extractive sector commodity like diamonds holds strategic significance for economies. This means the industry is typically governed or controlled at the highest political levels, i.e., by the executive. Thus, in environments with weak regulatory and accountability institutions, the control of the extractive sector can easily fall into the hands of elites with limited external control and broad discretionary power (as seen above in the case of Angola). Thus, wider structural reforms designed to improve the accountability of governing bodies must be considered by those seeking to reduce corruption in the extractive sector.

In the application of anti-corruption measures, the first step would be to conduct a corruption risk assessment to tailor anti-corruption measures to specific vulnerabilities. The following potential anti-corruption approaches aimed at the diamond sector in Angola are illustrative. The measures are also aimed at a variety of stakeholders: host governments, international regulatory bodies as well as civil society actors.

Addressing corruption risks throughout the diamond value chain

The OECD (2016) published a report titled Corruption in the extractive value chain: Typology of risks, mitigation measures and incentives that sets out types of corruption schemes at each stage of the extractive value chain, the vehicles and parties involved, and mitigation measures, as well as incentives and barriers to making corruption less attractive in the sector. This can be adapted for the diamond sector. The report goes into a detailed analysis of each stage of the extractive value chain. The corruption mitigation strategies are aimed at host governments, companies and donor agencies.

Cross-cutting anti-corruption measures mentioned include (OECD 2016: 18-25):

Addressing gaps in anti-corruption and judicial systems: governments can carry out a preliminary risk assessment of all institutions involved in the extractive process to identify specific gaps and ensure that there is robust anti-corruption legislation implemented on the ground. Donors could provide support for the development or strengthening of anti-corruption agencies; or bolster citizen control through civil society organisations (CSOs) and media.

Countering discretionary powers: governments can introduce standardised and automatic procedures for licensing and procurement, limit political interference by ensuring merit based appointments to key positions, regulate lobbying activities, have clear codes of conduct and put mechanisms in place to prevent and detect conflicts of interest, among others. Companies can rigorously monitor the relationship between corporate personnel and public officials to safeguard against collusive practices.

Tackling inadequate governance: the mandate, administrative capacity and functions of state-owned companies ought to be clarified. Moreover, proper oversight mechanisms should be set up for SOEs. Donors can support relevant initiatives (such as national Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative chapters or other anti-corruption bodies) to ensure adequate monitoring of all stages of the extractive value chain. Other measures could include engaging with all stakeholders, especially extractive businesses or public-private partnership projects. For instance, multi-stakeholder dialogues can be organised and personnel can be trained on relevant standards, among others.

Dealing with gaps and discrepancies in corporate due diligence procedures: a comprehensive anti-corruption management system (in accordance with standards such as OECD Good Practice Guidance on Internal Controls, Ethics and Compliance, updated 2021) ought to be established within businesses. Such systems need to be allocated appropriate budgets and must be based on thorough corruption risk assessments. Regular reviews of systems are also required to identify gaps and to enable lessons to be learnt.

Beneficial ownership transparency: the first step is facilitating a legal framework for public beneficial ownership disclosure. Moreover, national jurisdictions should create public beneficial ownership registers of companies incorporated or that have their offices in their country. This register must also record ownership changes over time. Companies can support this process by disclosing beneficial ownership information and communicating further changes as they happen.

The detailed list of mitigation measures for cross-cutting issues along the extractive pipeline can be found here.

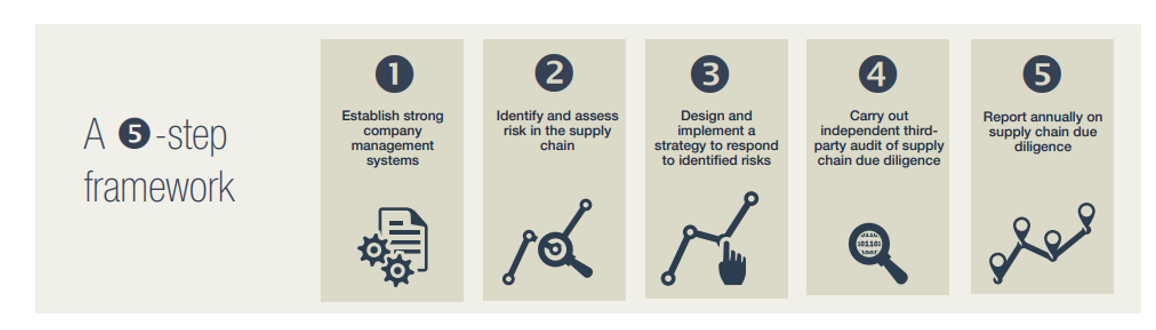

For extractive industries operating in high-risk and conflict afflicted jurisdictions, OECD has prepared a Due diligence guidance for responsible supply chains of minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas (2016). The guidance delineates a five-step framework for companies as seen in the infographic below (OECD n.d.).

Figure 5. Five-step due diligence framework for responsible supply chains of minerals from conflict-affected and high-risk areas

Source: OECD (2016)

The Kimberly Process

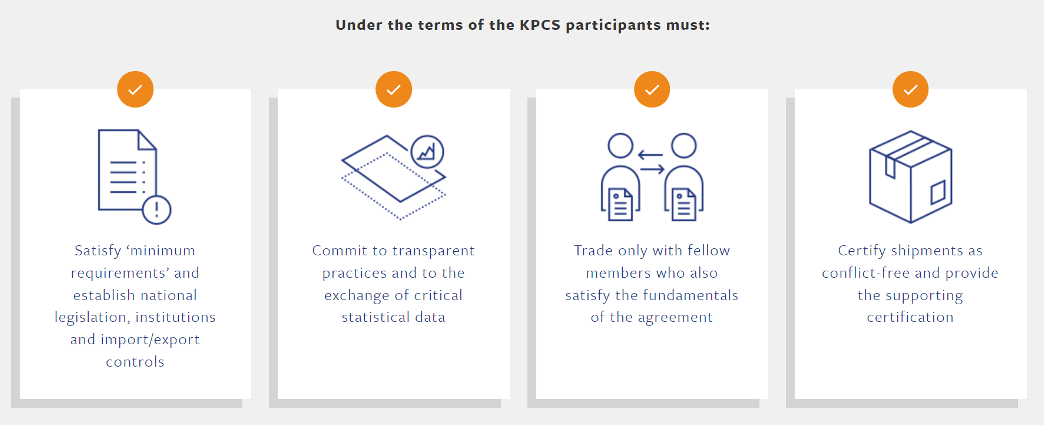

The Kimberly Process (KP), a multilateral trade regime, was set up in 2003 to stem the flow of diamonds being used to finance conflict in various states. At the heart of this regime is the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme (KPCS), under which countries employ “safeguards on shipments of rough diamonds and certify them as conflict free” (KP 2022).

Despite such standards, CSOs such as Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, Enough Project, Global Witness and Impact note that the “diamond industry continues to be tainted by links between diamonds and human rights abuses, conflict finance, and corruption” (Amnesty International 2018). These observers add that although “the diamond industry is not the only sector facing these threats, it is unique in its particular unwillingness and inability to take genuine steps towards responsible business conduct” (Amnesty International 2018).

Figure 6: Terms for KPCS participants.

Source: KP (2022).

Human Rights Watch (2018) identifies several shortcomings with the Kimberley Process:

It depends on an “indefensibly narrow” definition of what comprises a conflict diamond, only focusing on misuses by rebels while ignoring those of state actors or private security firms. For instance, even though the diamonds from Angola and Zimbabwe are mined under highly abusive conditions, the Kimberley Process has authorised exports of these diamonds under its banner.

The process only applies to rough diamonds, permitting fully or partially cut and polished stones to fall outside the initiative’s scope. Moreover, many diamond shipments passing through trading hubs are mixed with diamonds from other export countries, rendering them untraceable to their source.

The Kimberley Process has also shown hesitation in imposing sanctions on countries found non-compliant with its minimum requirements (the exception is the case of the war-torn Central African Republic).

The World Diamond Council’s System of Warranties, meant to support the KPCS, depends on “written or oral assurances” by diamond suppliers instead of being subject to independent and transparent monitoring.

Civil society critics point to the fact that the KP process is moving more towards confidentiality instead of transparency, adding that “little has been made public about the reform agenda or its broader activities” (Amnesty International 2018). Thus, Amnesty International (2018) has called for the industry as a whole to implement responsible sourcing practices that are directly aligned with the OECD Due Diligence Guidance for Responsible Supply Chains of Minerals from Conflict-Affected and High-Risk Areas, as well as the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.

Another avenue to explore in relation to certification processes could be ensuring traceability. As has been discussed, it can be difficult to delineate the source of diamonds; nevertheless, efforts can be made to ensure traceability. For instance, a Canadian diamond company, the Dominion Diamond Corporation, has launched a brand of traceable diamonds called CanadaMark, which are “independently tracked at every stage from the mine to polished stone” (Human Rights Watch 2018).

Extractives Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI)

EITI serves to strengthen governance and accountability in the extractives sector. Member countries of the initiative “commit to disclosing information along the extractive industry value chain – from how extraction rights are awarded to how revenues make their way through government and how they benefit the public” (EITI n.d.). EITI standards are implemented in member countries through multi-stakeholder participation, comprising the government, businesses and civil society (EITI n.d.).

In June 2022, Angola was approved by the EITI board to join EITI, making it the initiative’s 57th member country and the 28th in Africa (EITI 2022). As a process of its new membership, Angola will have to make relevant disclosures around topics such as “beneficial owners [including links to politically exposed persons] and contracts pertaining to extractive companies, as well as the management of state-owned enterprises and sector revenues”, among others (EITI 2022). The first set of disclosures will have to made within 18 months of its joining (EITI 2022). Information on these key areas can support the identification of corruption risks, bring about necessary transparency to a largely opaque system, open the way for civil society participation and boost the sustainable management of mineral resources within the country (EITI 2022).

Whistleblower protection

Given the high stakes and the power asymmetries between large diamond companies and state-controlled extractive industries on the one hand and anti-corruption activists, journalists and whistleblowers on the other, it is imperative that robust protection for civic space in general, and whistleblower protection in particular be implemented.

For instance, Rafael Marques de Morais, author of Diamantes de sangue: Corrupção e tortura em Angola (Blood Diamonds: Corruption and Torture in Angola) was sentenced to six months in prison when army generals and business elites filed a case of criminal defamation for being implicated in the book (Global Freedom of Expression 2015; Reventlow 2015).

Looking at other standards that go beyond a narrow conflict-only focus

Standards such as Maendeleo559e668793a8 Diamond Standard, deployed by the Development Diamond Initiative (DDI), go beyond conflict classification to address labour conditions, child labour, health and safety, and environmental protection. The DDI process includes independent and random audits at mine sites to ensure compliance. The initiative has been endorsed by several actors in the jewellery business including De Beers, Tiffany and Co., Cartier, and Rio Tinto (Human Rights Watch 2018).

Gender sensitivity in deploying anti-corruption measures

Little is known about the experience of women in the Angolan diamond mining sector. The US Department of State (2021: 24) reports that there are legal restrictions on women’s employment in occupations and industries compared to men. These include jobs that are perceived to be dangerous in factories, mining, agriculture and energy sectors. At the same time, forced labour of both men, women and children is known to take place in diamond mining in the country (US Department of State 2021: 33). Migrants face extra harassment in terms of “seizure of passports, threats, denial of food, and confinement” (US Department of State 2021: 33). In neighbouring Zimbabwe, diamond syndicate operators offer girls working under them to the police for sex as bribes (TI Zimbabwe 2012: 104).

Mineral development policies ought to be gender sensitive, formed through the participation of women and other vulnerable groups to address specific gendered forms of corruption in a particular context (TI Zimbabwe 2012: 105).

- Here it might also be worthwhile to understand that corruption is both a product and driver of instability. For instance, corruption exacerbates conflict by creating conditions in which conflict is likely to occur, fuels and maintains existing armed struggles, and weakens peacebuilding and peace-keeping efforts (Jenkins 2016: 11).

- The MPLA government was then recognised formally by a number of national governments. For instance, in 1993, US President Bill Clinton formally recognised the new government of Angola formed by the MPLA, while urging UNITA to accept a negotiated settlement (Office of the Historian n.d.)

- Alrosa and De Beers still control over half of the world’s rough diamond sales (HRW 2018a).

- As more diamond mines were discovered in North America, Russia and Australia, new players emerged, and the company found it “harder and harder to maintain its iron grip on the market” (Behrmann and Block 2000).

- Jointly owned by the Angolan state-owned Endiama and Russian company Alrosa, the world’s biggest diamond miner and subject of US sanctions (Cotterill 2022).

- Largely those figures closely connected to the former President dos Santos.

- The bank was Banco Bic Angola, which was established in Angola in 2005, and in 2008 it expanded operations to Europe by establishing Banco BIC Português, S.A. in Portugal (BankBIC n.d.).

- It was the first public US response to years of accusations of wrongdoing. The move took place two years after the Luanda Leaks (Fitzgibbon 2021).

- These are often through a concession agreement negotiated by means of the execution of a private investment agreement, which is, in the end, approved by the president (Santos Vitor et al. 2019).

- Artisanal or small-scale miners are subsistence miners who are not officially employed by a mining company but work independently, mining various minerals or panning for gold using their own resources (Santos Vitor et al. 2019).

- Where the diamond producer/miner has the right to sell to the buyers they prefer.

- Maendeleo is a Swahili word meaning “development” and “progress”.