Caveat

This Helpdesk Answer focuses on corruption during the distribution of humanitarian assistance in conflict zones once these resources leave an aid agency. As such, the paper does not consider organisational corruption risks that could affect aid agencies, such as malpractice during the agency’s acquisition of goods and services outside of the conflict zone, unethical practices by agency leadership or undue influence over the agency’s internal decision-making. A comprehensive view of both internal and external corruption risks in humanitarian operations more generally is provided by Hees et al. (2014).

For aid agencies attempting to deliver humanitarian assistance to populations in conflict zones, addressing corruption is only one part of a bigger picture. Related considerations include the selection of appropriate aid modalities and delivery mechanisms, identifying suitable in-country partners, negotiating access with armed actors including non-state groups, establishing the needs of affected populations and providing them with a degree of downward accountability. For a broader analysis of how to deliver quality humanitarian assistance in conflict settings, see a study by Haver and Carter (2016) assessing what worked in Afghanistan, Somalia, South Sudan and Syria.

Finally, the Helpdesk Answer also does not consider how measures to tackle corruption in humanitarian aid could fuel violence, or how aid agencies can mitigate this risk.

Query

Please provide an overview of how corruption affects humanitarian aid provided to conflict-affected countries and identify potential safeguards in conditions of remote management.

What is at stake in humanitarian assistance?

International legal instruments establish certain basic rights for all human beings, including life, food and shelter (United Nations 1948). Yet some states, especially those affected by conflict, are ‘unable or unwilling to protect those fundamental human rights’ for part or all of their population (Carr & Breau 2009: 1). In such circumstances, other states and international organisations may intervene to try to uphold these rights, most often through the provision of humanitarian assistance to affected populations. This is in line with International Humanitarian Law, which stipulates that the civilian population of states affected by armed conflict is entitled to receive humanitarian assistance in the form of food, medicine and other critical supplies (International Committee of the Red Cross 2023).

Humanitarian assistance has been described by Carr and Breau (2009: 6) as the provision of ‘assistance to victims in third states or victims from third states for the purposes of relieving suffering caused by natural disasters or man-made disasters without discrimination on the basis of race, ethnicity, gender, sex, age, religion, nationality or political affiliations’. As ALNAP (2022: 102) states, this implies a balancing act between prioritising those facing the most acute need while also assisting as many people as possible.

The humanitarian sector has grown rapidly in the last decade, rising in financial terms from US$16.4 billion in 2012 to US$31.3 billion in 2021. Of this, US$24.9 billion came from governments and EU institutions and US$6.4 billion from private sources. In the same period, there has been a 40% rise in the number of humanitarian staff working in crisis areas (ALNAP 2022: 49). OECD DAC donors continue to account for more than 90% of reported humanitarian aid provided by governments (ALNAP 2022: 58), while nearly half of all humanitarian assistance funds were allocated to just three UN agencies: the World Food Programme, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and UNICEF (ALNAP 2022: 49). Nonetheless, it is important to recognise that international humanitarian assistance (IHA) forms only one part of the inflow of resources to crisis-affected countries, with other funding coming from community-led support, religious organisations, the private sector and diasporas (ALNAP 2022: 70).461a3c4888d4

In donor countries, a contentious issue in policy debates on foreign aid is the extent to which it is affected by corruption, and especially how much development funding and humanitarian assistance is misappropriated by actors in crisis-affected countries (House Committee on Oversight and Accountability 2024). Likewise, in aid recipient countries, Feldman (2018)documents how reciprocal allegations of corruption play an important role on the ground in interactions between providers and recipients of humanitarian assistance.

Empirical assessments seem to indicate that, overall, the proportion of foreign aid lost to corruption is relatively minor. Kenny (2024b) points out that of the US$8.5 billion spent by the US on reconstruction projects in Afghanistan between 2012 and 2020, only 0.4% of audited costs were ultimately disallowed. He also notes that only 0.1% of the value of World Bank contracts between 2007 and 2012 were found to have sanctionable incidents of fraud or corruption (Kenny 2017).

Nonetheless, there is consensus in the literature that humanitarian assistance is more vulnerable to corruption than other forms of official development assistance. According to Darden (2019b), estimates by those working in the humanitarian sector of losses to fraud and corrupt diversion of IHA range from 2% to 15%.ee1345796dcd Between 2015 and 2019, the USAID Office of the Inspector General (2019) received 358 allegations of fraud, theft, armed group diversion, bribery and other integrity breaches across its humanitarian operations in Lebanon, Iraq, Jordan, Turkey and Syria.fafba98357a8

Moreover, while the scale of corruption in foreign aid is likely not as extensive as claimed by some politicians in OECD DAC countries (Greenberg 2017), it is clear that corruption has a negative impact on the quality and quantity of international humanitarian assistance delivered to populations in need. According to a survey conducted as part of the 2022 study The State of the Humanitarian System, only 36% of aid recipients agreed that aid reached those who needed it most (ALNAP 2022: 106). This suggests that affected populations perceive widespread corruption and mismanagement in the delivery of IHA and that the diversion or theft of resources supplied by aid agencies is a ‘top concern for communities’ (ALNAP 2022: 101).

Not only can corruption reduce the amount of aid reaching the intended beneficiaries but poorly conceived humanitarian initiatives could potentially fuel further insecurity in crisis regions by providing incentives for continued conflict (Keen 2008). Importantly for anti-corruption practitioners, the form and extent of corruption in the delivery of aid appears to be a significant variable in whether IHA inflames or dampens violence. Where predatory behaviour diverts resources to armed groups and distorts the delivery of aid so that desperate people are left empty-handed, the potential for violence increases (Zürcher 2019: 849).

As Maxwell et al. (2012: 144) observe:

‘Humanitarian emergencies are particularly complex and often occur in political environments where the combination of destroyed or dysfunctional systems, the injection of external resources, and extreme and frequently rapidly shifting power relations creates the dangerous possibility of corrupt diversion of assistance intended for vulnerable people, as well as reinforcement of the circumstances that have made people vulnerable in the first place.’

Compounding this situation is the perception among aid agencies of a trade-off between the urgent need to reach populations in need and the desire to limit fraud, embezzlement and theft. Strand (2020) argues that in practice this typically leads to a greater willingness among aid agencies to tolerate corruption in humanitarian settings. Indeed, there are calls by some practitioners in the sector to recognise that

‘maintaining a principled humanitarian response will sometimes require making compromises (in order to access people), which can involve payments or other concessions that benefit private individuals – essentially, forms of corruption’ (Haver & Carter 2016: 50)

The situation is further exacerbated by the fact that aid agencies may have ‘little in-depth knowledge of the environment’ into which they are disbursing humanitarian assistance (Strand 2020). Limited familiarity with a country’s political economy may be especially pronounced when aid agencies operate in countries categorised as ‘closed autocracies’, to which there was a 19-fold increase in the provision of humanitarian aid by OECD DAC donors between 2010 and 2019 (Organisation for Economic Co-operation Development 2022). Revealingly, a study into delivering humanitarian aid to the most insecure environments by Haver and Carter (2016) identified corruption and the diversion of aid as one of the critical barriers to effectiveness, alongside staffing issues, finding suitable partnerships, negotiations with armed actors and communication with affected people.

Populations in conflict-affected states are particularly vulnerable to situations in which corruption scandals lead donors to suspend their programming (Cliffe et al. 2023: 31). Indeed, Cliffe et al. (2023: 8) contend that the ongoing crisis in Syria underscores how donor disengagement can aggravate conditions by accelerating ‘the collapse of social service provisions, further erosion of weak institutions, and the rise of corrupt and predatory behaviours’. The question therefore becomes how aid agencies can minimise the corrosive impact of corruption on their operations while mitigating any harmful unintended consequences generated by the supply of valuable resources into crisis regions.

Specific corruption risk factors for humanitarian assistance in conflict zones

Countries with active conflictse590ab3d62b0 comprise a high proportion of states receiving humanitarian aid; in 2021, 27 out of 30 humanitarian response plans were developed for conflict-affected countries (ALNAP 2022: 277). These settings pose additional and severe challenges for aid agencies seeking to ensure that the humanitarian assistance they provide reaches its intended beneficiaries.

Predatory political economies

In conflict zones, armed non-state actors often act as ‘gatekeepers’, controlling information about, access to and the resources of local populations (Maxwell et al. 2008: 9). As armed groups compete for territorial control and legitimacy, they are likely to try to monopolise control over the influx and distribution of aid to shore up their political position. The ‘predatory political economies’ that characterise war zones are widely associated with high risks of aid diversion by warring parties (Maxwell et al. 2008: 4).

In this sense, international humanitarian assistance (IHA) appears to be viewed by many armed groups as one potential revenue stream among many; Bandula-Irwin et al. (2022) have shown how armed groups ‘tax’ constituencies under their control, including civilians, NGOs, businesses and international community actors such as humanitarian agencies. Interestingly, while material gain is a powerful incentive for these groups, Bandula-Irwin et al. (2022) contend that armed actors levy ‘taxes’ for multiple reasons, including to enhance their legitimacy, control over local communities, build institutions and provide public services.

In these settings, aid agencies often operate at the discretion of the de facto authorities in the territories they are trying to reach. Insurgents are generally reticent to fully evict humanitarian actors as coming to an arrangement with aid agencies can convey legitimacy as well as provide valuable goods that support both the fighters and the wider community that sustains them. Nonetheless, dealings with armed groups can be highly volatile given that their goal is typically political and military supremacy, rather than the well-being of population groups in the territory they control.

Acute need associated with human rights abuses

Beyond stealing a certain percentage of aid funds passing through their territory, armed groups may commit human rights abuses in areas under their control, including unlawful killings, forced displacement, sexual violence and recruitment of child soldiers. These rights violations mean that the need for humanitarian relief and protection is especially acute, building pressure on aid agencies to deliver assistance quickly (Maxwell et al. 2008: 9). Aid agencies may be compelled to rapidly roll out humanitarian aid without having had an opportunity to establish robust delivery mechanisms to ensure equitable and comprehensive coverage.

Maintaining impartiality in a fragmented political landscape

The complex political and military landscape in conflict zones, often characterised by a fragmentation of authority among multiple armed groups, makes negotiating access to affected communities time-consuming and dangerous. Once access has been secured, prioritising those most in need is also ‘an approximate and contested process’, which in conflict settings is both technically difficult and deeply political (ALNAP 2022: 102). In addition, aid agencies may have few options other than to contract politically connected suppliers when importing and transporting goods in the country (Resimić 2024: 17). Navigating local politics while maintaining neutrality and impartiality in aid delivery thus requires careful diplomacy on the part of aid agencies (Darden 2019b).

Security-related obstructions

Armed groups may obstruct the delivery of aid to certain population groups. ALNAP (2022: 140, 182) states that in Myanmar, Syria, Ethiopia, South Sudan and Yemen, both state and non-state armed groups have restricted the access of local communities to food and medicine in recent years. These situations exacerbate scarcity and concentrate access to resources in the hands of a few individuals, causing ‘critical survival challenges’ and generating ample opportunities for corrupt abuses of power (Maxwell et al. 2008: 9; Strand 2020).

War-damaged infrastructure such as bridges, roads and utilities can make travelling to frontline areas challenging, hindering the delivery of aid. At the same time, conflict is likely to have disrupted pre-war administrative, legal and financial systems (Maxwell et al. 2008: 9). Administrative records on different population groups are likely to be missing or incomplete, such as census data that could help aid agencies to better understand needs in different localities and allocate aid accordingly.

Not only can roadblocks, destroyed infrastructure or active combat prevent aid agency staff from accessing affected populations, armed groups are also known to deliberately target aid workers; in 2022 alone, 460 were killed, injured or kidnapped, the vast majority of whom (436) were national staff (Aid Worker Security Database 2023). Violence against aid workers in Syria has increased markedly in recent years and presents a major obstacle to reaching communities in need (ALNAP 2022: 109). Non-state armed groups, including the Islamist coalition Hay’at Tahrir a-Sham in Idlib province, have also reportedly hindered monitoring and evaluation activities in refugee camps (USAID Office of the Inspector General 2019: 5).

Remote monitoring

Where aid agencies do not have an in-country presence due to physical security risks to their staff and instead conduct cross-border operations from neighbouring countries, monitoring the use and impact of humanitarian assistance can be extremely challenging. The withdrawal of project staff and increased reliance on sub-contracting and proxy monitoring can weaken programme management and accountability (Hees et al. 2014: 138). Humanitarian corridors – negotiated agreements to allow safe passage to humanitarian convoys through to war-torn areas – may be subject to constant bargaining with armed groups who try to extort aid agencies in return for keeping the corridor open. Airdrops are another option to areas where access by road is restricted, but here aid agencies have virtually no control over the distribution of the goods provided.

Even where humanitarian actors partner with local people to monitor the delivery of aid, without on-the-ground verification, there is little guarantee that the data is not manipulated to inflate beneficiary numbers, favour certain population groups, exaggerate needs assessments or misrepresent project progress. Local staff involved in remote monitoring activities can still be vulnerable to physical threats, including intimidation or coercion by armed groups (Haver & Carter 2016: 47). This can be especially concerning where territory has changed hands and the new de facto authorities demand access to sensitive information, such as the personal details of aid workers or beneficiaries.

Consultation with affected populations is also likely to be a challenge, which can lead to ‘supply-driven’ rather than ‘demand-driven’ humanitarian aid. The provision of in-kind goods not actually required by targeted populations, as reportedly occurred in Syria when aid was sent by aid agencies from government controlled territories to other areas, can decrease constraints on these materials being stolen and sold on the black market (ALNAP 2022: 141).

International coordination

Coordinating humanitarian efforts among multiple actors, including governments, UN agencies, NGOs and local partners is highly fraught in conflict zones due to security risks, competing geopolitical agendas and lack of trust among stakeholders. In Syria, for example, Russia and China have used their vetoes in the UN Security Council to close three of the original four UN mandated border crossings into the north-west of Syria (Hall 2022: 3).

Lohaus and Bussmann (2021: 15) point out that rival external actors to a conflict often use corrupt means to ‘secure the allegiance of local players.’ On the other hand, local actors themselves may exploit any lack of coordination between different aid agencies to disguise corruption or game the system through practices like ‘double dipping’. In addition, sanctions by donor countries imposed on various armed groups and terrorist designations have apparently led certain aid organisations to suspend the provision of assistance to some areas out of fear of criminal liability should it transpire that designated terrorist groups have materially benefitted from the resources provided. This is reportedly the case in north-western Syria, where the need for IHA is acute (ALNAP 2022: 114). For more information on how to navigate international sanctions regimes when delivering aid to conflict zones, see Debarre (2019).

Outlook

Given the numerous barriers and risks involved in delivering humanitarian assistance in conflict zones, it is perhaps unsurprising that ALNAP (2022: 278) observes an ongoing trend that ‘fewer international humanitarian organisations [are] respond[ing] to highly violent, conflict-driven emergencies, irrespective of funding available and the needs of the population’. While ever-greater amounts of IHA are being provided to conflict-affected countries, including to areas outside of state control, there is often a high price to pay ‘not only in terms of financial costs, but also in terms of principles’ (ALNAP 2022: 278). Yet beyond the quantity of aid distributed, there is often limited analysis of the positive and negative effects of humanitarian assistance in countries experiencing intense conflicts (ALNAP 2022: 278). The evidence base for this, and the link to corruption, is briefly considered in the next section.

Corruption, humanitarian assistance and conflict

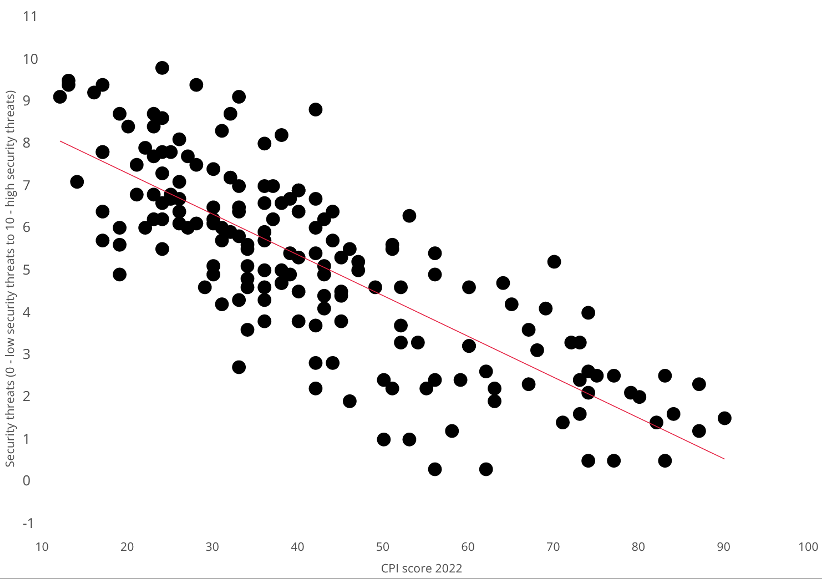

There is evidence of a strong correlation between conflict and corruption, as depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Corruption and security threats

Transparency International 2023.

Based on a cross-sectional analysis of conflict-affected countries between 1970 and 2014, Lohaus and Bussmann (2021) conclude that lengthy and intense conflicts are associated with a notable increase in levels of corruption compared to a country’s pre-war baseline. Syntheses of the literature by Transparency International Defence & Security (2017) and Transparency International (2023) point to a causal and symbiotic relationship, where corruption ‘creates conditions in which conflict is more likely to occur by fostering division between different groups and eating away at the rule of law’, while conflict creates ample opportunities for the corrupt abuse of power and the illicit capture of revenue streams, including humanitarian aid. As Lohaus and Bussmann (2021: 17) point out, ‘wars can interrupt the existing patterns and lead to new networks of corruption, thus fuelling the escalation of new conflicts’.

Despite this, there is limited evidence that IHA itself increases background levels of corruption in conflict-affected countries. Lohaus and Bussmann (2021: 15) hypothesised the large inflow of foreign funds would shape incentives for local actors in a way that ‘tilt[s] the balance away from public-goods provision towards rent-seeking’ and corruption. However, they found that the extent of international involvement in a conflict-affected country has no significant effect on the levels of corruption in that country.

Aid agencies seeking ‘do no harm’ in war-torn countries would therefore be well advised to consider the impact of corruption both on individual recipients, for whom the illicit diversion of humanitarian aid could have fatal consequences, as well on the wider dynamics of the conflict (ALNAP 2022: 190). As staff from Médecins Sans Frontières working in Chad and Darfur observed (Kahn & Lucchi 2009: 22),

‘We are unable to determine whether our aid helps or hinders one or more parties to the conflict […] it is clear that the losses – particularly looted assets – constitute a serious barrier to the efficient and effective provision of assistance, and can contribute to the war economy. This raises a serious challenge for the humanitarian community: can humanitarians be accused of fuelling or prolonging the conflict?’

Aid modalities in conflict zones

Before turning to a discussion of forms of corruption in IHA in conflict settings, a short overview of two core modalities of humanitarian assistance is useful: in-kind support and cash and voucher schemes.

In-kind support

In conflict-affected regions, governments, international organisations and private donors can provide affected populations with in-kind assistance, namely basic goods or services including food, shelter, non-food items like blankets and cooking utensils, medical supplies and educational materials (CALP Network 2024). These physical items are typically transported and distributed by aid agencies or their in-country partners, including through the use of mobile clinics and the establishment of more stationary infrastructure like latrines, accommodation or venues for vocational training and psychosocial support. A large proportion of aid delivered from Turkey into Syria, for instance, was sent as ‘one-off, mobile deliveries’ (Haver & Carter 2016: 26).

While a recent evidence review concluded that in-kind transfers are generally able to meet the basic needs of crisis-affected populations, it is increasingly thought that the delivery of physical goods is usually less cost-effective than cash or voucher schemes (Jeong & Trako 2022).

Moreover, the distribution of bulk supplies not only entails high transaction costs but is exposed to certain types of corruption throughout the supply chain. As the delivery of physical goods is often highly visible in crisis regions, aid convoys may be targeted for extortion or diversion by armed groups or local authorities (Hees et al. 2014: 157). In addition, distributors – whether agency staff or partners – may misappropriate in-kind assistance for their own use or sale. Corruption can lead to suppliers delivering fewer or lower quality goods than agreed, while unscrupulous intermediaries may manipulate inventory documents and skew delivery away from intended beneficiaries. Maxwell et al. (2012: 151) report that in both Afghanistan and Somalia, refugee camp leaders stole between one-third and one-half of food aid. Despite these risks, there are situations in which in-kind assistance remains aid agencies’ best option, such as where local markets have collapsed and there is no local supply of basic necessities (CALP Network 2024).

Cash and vouchers assistance (CVA)

The proportion of humanitarian assistance delivered via cash and voucher schemes is growing, and it now comprises around a fifth of total IHA (ALNAP 2022: 143). According to ALNAP (2022: 168, 252) there is now a ‘strong evidence base for [its] outcome-level effectiveness’ and cost-efficiency vis-à-vis in-kind assistance, as well as wider benefits such as greater dignity for recipients and the stimulation of local economies. While recipients can spend cash as they see fit, vouchers are ‘paper or electronic tokens that can be exchanged for a set value, quantity or type of goods or service […] and often have an expiry date’ (CALP Network 2024).755f78037b97

Cash can either be delivered physically or digitally through local banking systems or mobile money technology. Particularly the digital transfer of cash can circumvent some of the corruption risks involved in distributing physical goods by eliminating the need for procurement, transport, storage and distribution (Hees et al. 2014: 161). Bailey and Harvey (2015) found ‘no evidence of cash assistance being more or less prone to diversion than other forms of assistance’. Nonetheless, CVA schemes may simply displace corrupt behaviour rather than eradicate it.

In the absence of a functional banking infrastructure, aid agencies may rely on the physical transfer of cash, which can be even more attractive for intermediaries and armed groups to intercept than in-kind goods. One mitigating factor here is that cash is less bulky than other in-kind assistance, so distribution mechanisms may be less visible to potential predators (Maxwell et al. 2008: 13).

Cash sent to aid recipients via the national banking system or mobile phone networks is generally viewed as less susceptible to embezzlement or diversion than physical delivery via local shops, traders and other intermediaries (Hees et al. 2014: 161; Maghsoudi et al. 2023). Nonetheless, it can still be vulnerable to fraud in the banking system and collusion by money merchants to fix exchange rates (Hees et al. 2014: 108). Moreover, digital delivery mechanisms do not remove the risk of biased targeting criteria, manipulation of lists of recipients or the inflation of supposed beneficiaries (Hees et al. 2014: 161).

Some studies suggest that, in conflict zones, cash transfers are in fact more vulnerable to corruption than in-kind assistance, which may be explained by the fact that these settings are more likely to be characterised by a dysfunctional financial system, regulatory challenges and inadequate local markets (Haver & Carter 2016: 65). Thus while the experience of CVA schemes among Syrian refugees in Jordan and Lebanon appears to have been relatively successful (Harmer & Grünewald 2017; Schuler et al. 2017), in highly insecure environments, many donors reportedly consider the fiduciary risks of cash-based assistance to be unacceptably high (Haver & Carter 2016: 13, 65; Shipley 2022: 12).

Notably, international sanctions regimes and counter-terror regulations are reportedly an obstacle to cash assistance in Syria, while the closure of banks in Ethiopia has hindered aid agencies’ ability to provide cash (ALNAP 2022: 142-145). Wider considerations of cash-based assistance include potential inflationary pressures and protection risks such as gender-based violence against women collecting cash (ALNAP 2022: 145, 165).

Forms of corruption affecting humanitarian assistance in conflict settings

To deliver IHA, aid agencies need to engage in numerous activities, from procuring goods to transporting supplies, identifying target areas, conducting needs assessments, registering recipients and distributing aid (Carr & Breau 2009: 16). Much of this involves working with independent contractors and local partners, and every stage of the operation provides opportunities for corruption. Indeed, the range of integrity risks can appear overwhelming, from extortion by customs officials at the border to the fraudulent diversion of supplies, as well as non-financial forms of corruption including the skewed distribution of aid to serve political ends, nepotism in recruitment, undue influence over contracting arrangements and sexual corruption at the point of distribution (Shipley 2022: 5).

This section provides a structured overview of different forms of corruption that can plague humanitarian assistance in conflict zones. These include both classic forms of corruption, such as embezzlement, as well as manifestations of corruption that are unique to conflict zones, such as predation by armed groups.

Paying for access and extortion

Various gatekeepers are likely to attempt to exert control over the supply of IHA to crisis regions, including local government officials, elites, traditional leaders, volunteers, militias and religious organisations. The ability to ‘block, divert or skew aid’ can increase their power in contested territories and create leverage over aid agencies (Hees et al. 2014: 136).

A tactic employed by armed actors is to obstruct the flow of aid in an attempt to coerce aid agencies to meet their demands. This can occur at the strategic level, where access is denied to the entire territory or visas for international staff are refused. It can also happen at an operational level in the supply chain, such as delays during customs clearance or withholding travel permits. Finally, at the point of service delivery, roadblocks in affected areas may prevent aid convoys from passing (Hees et al. 2014: 82). Haid (2019: 2) has shown how Assad’s government in Syria has sought to undermine the independence of aid organisations, imposed local partners on them, influenced procurement procedures and obstructed direct monitoring and evaluation efforts. The cumulative effective of these types of impediments in Syria and Yemen has been ‘debilitating’ on aid operations (ALNAP 2022: 113).

Bribes and other illicit transactions may be extracted by regime officials, insurgent groups or local militias in return for unblocking the flow of aid. In Syria, for instance, government officials reportedly informed UN agencies and international NGOs that they would be denied future access to the country if they mentioned systemic diversion of aid convoys by the regime (Hall 2022: 36).

Armed groups may impose ‘pay-to-play’ extortion schemes, making physical threats and psychologically coercing aid staff to pay for access to territories they control (Hees et al. 2014: 102). State actors can also extract concessions from humanitarian actors, like demanding that aid be routed through or delivered by firms affiliated with the regime. In Syria, for example, Cheng (2022) reports allegations that the head of the WHO office pressured her staff to sign contracts with senior government officials. Another study of the 100 largest suppliers to UN agencies operating in Syria found that 47% of the contracts were awarded to risky or high-risk suppliers with ties to the Assad government (Syrian Legal Development Programme & Observatory of Political and Economic Networks 2022).

In Somalia, interviews with aid staff and local communities indicates that ‘access is almost always bought or paid for at some level (in the form of money, jobs or contracts)’ (Haver & Carter 2016: 52). Darden (2019a) reports that al-Shabaab’s Humanitarian Coordination Office has forced aid agencies to pay ‘registration fees’ of around US$10,000. Whereas a standard ‘tax rate’ of around 30% applies on all aid delivered in areas controlled by al-Shabaab, in other parts of the country ‘favours may amount to little more than a few hundred dollars or the inclusion of several family members or local militia on a beneficiary list’ (Haver & Carter 2016: 52). It appears that in Somalia at least, aid staff on the ground have a degree of discretion about the tolerable threshold for concessions to secure humanitarian access. However, the extent of these concessions may not be known by senior managers based in Kenya (Haver & Carter 2016: 52).

Haver and Carter (2016: 11, 51) observe that ‘paying for access and granting concessions are commonplace, yet remain taboo’ in the humanitarian community as most organisations have policies against ‘paid access’. Reported practices include paying money at checkpoints, paying unofficial taxes, extortion during customs clearance or agreeing to operate in certain areas rather than others to avoid antagonising local strongmen or insurgent groups (Carr & Breau 2009: 2). Occasionally, aid agencies may be able to avoid making illicit access payments by threatening to withdraw humanitarian assistance altogether or knowing which local actor to appeal to (Haver & Carter 2016: 52).

In the view of Haver and Carter (2016: 11), the culture of silence among aid agencies makes it hard to assess in which scenarios ‘paid access’ is justified. While most aid agencies reportedly do not have a strategic approach to engaging armed non-state actors to secure access, Haver and Carter (2016: 12) praise Médecins Sans Frontières and the ICRC for ‘organisational investments in engaging in regular dialogues with parties to the conflict’.

Aid diversion and embezzlement

A recent report into the humanitarian system called aid diversion a ‘fact of life’ in the sector (ALNAP 2022: 118). In a survey for that report, 73% of aid workers who answered stated that corruption was a moderate or high concern in the country they were operating in, while 22% of aid recipients identified aid diversion as the biggest problem they faced, which was second only to insufficient quantities of aid (34%) (ALNAP 2022: 118).

Hees et al. (2014: 84) point out that the diversion of aid can be systematic and pre-planned or opportunistic on the part of individuals involved in delivering aid, such as drivers. As indicated above, a proportion of the aid might be diverted by local strongmen in exchange for allowing the remainder to be delivered to the intended beneficiaries. Bandula-Irwin et al. (2022) has documented how armed groups in Afghanistan, South Sudan and Syria habitually levy ‘taxes’ on all revenue streams in territories they control, including humanitarian assistance, remittances and private investment. In contexts in which paying armed groups for access to communities is a realistic prospect, this can serve as convenient cover for unscrupulous individuals who can claim they were forced to hand some supplies over to armed actors, when in fact they have sold them on the black market themselves. Finally, convoys may also be raided by insurgent groups and armed militias.

There are no reliable estimates of the proportion of humanitarian aid diverted in conflict zones (ALNAP 2022: 119). Studies from Lebanon and Puntland nonetheless demonstrate the embedded nature of aid diversion in humanitarian responses, with state bodies, politicians, humanitarian agencies, local actors and community representatives all implicated (BouChabke & Haddad 2021; Sofe 2020). In the context of the recent conflict in Ethiopia, Knickmeyer (2023) reports that Ethiopian officials and fighters stole so much food aid that the US and UN temporarily suspended assistance to country.6677f7b83a57

Likewise, Hall (2022: 38) shows how food aid in Syria was systematically diverted to feed government troops, while the regime’s imposition of an artificially inflated exchange rate on aid agencies resulted in approximately half of the humanitarian funds supplied being used to prop up the Syrian Central Bank with foreign reserves (Hall et al. 2021). Another study on Syria has shown how aid diversion has affected humanitarian operations in Idlib and Northern Aleppo (Rasella 2023: 26). Aid diversion by designated terrorist groups is a particular concern for aid agencies in Somalia and Syria (Haver & Carter 2016: 12). Darden (2019a) reports that in 2018, USAID suspended a food aid programme in Syria worth nearly US$50 million after an investigation uncovered that, acting under duress, local employees of a US funded NGO had provided food to members of a terrorist organisation.

Given the blurred distinctions between civilians and soldiers both at the level of beneficiaries and authorities in South Sudan, ‘aid actors widely consider it impossible to keep food from reaching combatants’ (Haver & Carter 2016: 55). Both government forces and armed opposition groups there are reported to have looted food trucks or rerouted them to army barracks. Similar practices reportedly exist in Algeria, where armed groups in the Western Sahara region operate a ‘coordinated, systematic scheme to steal humanitarian aid goods’ intended for refugee camps and then sell these goods in Mauritania (Bondarenko 2022). In Yemen, Michael (2019) reports that trucks carrying medical supplies were hijacked by Houthi fighters, some of which were used on the frontline and some sold in pharmacies in areas under their control. According to Michael (2019), UN staff suspect that insiders within aid agencies had colluded with the Houthis to coordinate the theft.

Incidents such as these have led to pessimism in some quarters, with Zürcher (2019: 849) arguing that humanitarian actors should not provide aid to areas in which ‘insurgents retain meaningful capabilities to coerce and tax local communities and aid workers’. This view is nonetheless challenged by Cliffe et al. (2023: 8) and Haver and Carter (2016), who contend that disengagement by humanitarian actors aggravates the crisis on the ground, and make the case that even in insecure environments, ‘principled pragmatism’ can enable IHA to be effectively delivered.

Interference in targeting and registering beneficiaries

The impartiality and needs-driven targeting of humanitarian assistance can be undermined by donor governments, host governments at the national and local levels, non-state armed groups and community gatekeepers, each of whom may attempt to influence the allocation criteria and distribution patterns for political reasons (Haver & Carter 2016: 26). Indeed, in settings in which electoral politics are still playing out, a specific dimension entails the undue influence of local political functionaries, who direct aid to party members, supporters or vote banks (Khair 2017: 214-215).

Needs assessments

Needs assessments are vulnerable to manipulation by host governments and de facto authorities, who have been known to demand amendments to the data and to prevent the publication of the results of the assessment (Steets et al. 2018: 62). An evaluation of the humanitarian response to a drought in Ethiopia found that incentives existed among local leaders to both inflate the number of affected people identified in needs assessments to secure more resources as well as to underreport the scale of the crisis to demonstrate the apparent effectiveness of local leaders in dealing with the crisis (Steets et al. 2020). Hall (2022: 35) concludes that in extreme cases, for example, in government controlled territories in Syria, conducting an independent and accurate needs assessment is ‘virtually impossible’.

Community gatekeepers and local elites may also try to manipulate needs assessment by providing inaccurate data ‘to exclude or include certain populations […] due to political, religious, ethnic, tribal or clan or personal affiliations’ (Shipley 2022: 6).

Recipients lists

Once a needs assessment has been conducted, potential recipients of aid need to be identified and prioritised. Again, this provides ample scope for undue influence by various players (ALNAP 2022: 101). An evaluation of the World Food Programme documented numerous instances of government interference in amending aid agencies’ lists and drawing up alternative lists (Steets et al. 2018: 63).

In Syria, Rasella (2023: 26) states that authorities pressured aid agencies to serve specific communities and hire certain people. Likewise, Hall (2022: 38) reports that regime security officials vet names on recipient lists, noting that employees of the Syrian Arab Red Crescent admit that, under pressure from intelligence officials, they have denied food aid to certain individuals. In this way, the Syrian government has ‘manipulated aid deliberately and effectively in order to reward loyalists and punish alleged dissidents’ (Hall 2022: 2).cf806ef03cdd Also in Syria, an investigation found that NGO staff had intentionally manipulated recipient lists to include fighters from a non-state armed group and submitted falsified beneficiaries lists to the aid agency (USAID Office of the Inspector General 2019: 3).

In Afghanistan, Mozambique, Somalia and Yemen, ALNAP (2022: 107-108) states that community leaders and local elites have also been complicit in introducing intentional biases into the process of drawing up recipient lists and demanding the final say over which individuals receive aid. In response, aid recipients in some focus group discussions recommended that aid agencies cut out ‘community leaders’ altogether and deal directly with intended beneficiaries (ALNAP 2022: 108). Clear communication of eligibility criteria is also important; in Syria a failure to convey who was entitled to cash support led to rumours on social media and suspicion of targeting choices (World Food Programme 2021).

There is some suggestion that women and girls are disproportionately affected by corrupt abuses of power in the process of drawing up lists of recipients. A report by UNHCR and Save the Children (2002: 4) in Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone found that aid workers withheld services or refused to include girls on beneficiary lists in an attempt to extort sex. A more recent study of humanitarian aid in the DRC produced similar findings, that both cash and sex were demanded from intended beneficiaries in exchange for inclusion on the list of recipients (Henze et al. 2020: 24).

Point of delivery

Interference can also occur at the point of distribution. For instance, non-state armed groups have been shown to threaten aid agencies with violence unless they direct aid to specified locations (Maxwell et al. 2008: 14). In South Sudan, for instance, government authorities and armed opposition groups ‘routinely seek to influence the location of [aid] distribution’. (Haver & Carter 2016: 55). In the DRC and Yemen, ALNAP (2022: 119) found that various intermediaries had intercepted cash and charged recipients for assistance. Similarly in Somalia and Yemen, community power holders have been shown to interrupt the distribution process to prevent it disrupting existing patronage networks (Haver & Carter 2016: 12).

Nepotism

Intermediaries may insist on the inclusion of family or community members on recipient lists (Maxwell et al. 2008: 9). However, interference by local players in the delivery of IHA can affect not only the supply chain but also organisational practices. For example, aid agencies may come under pressure to hire certain individuals and local staff may prioritise their kinspeople in employment opportunities (Carr & Breau 2009: 16).

Corrupt procurement practices

In conflict-affected countries, aid agencies are likely to procure a wide range of goods and services from local suppliers and face constraints on their ability to oversee and audit these contracts. As such, standard integrity risks in procurement may be heightened, including manipulated tender specifications, collusion in the bidding process, bribery in the tender evaluation, embezzlement during contract implementation, falsification of receipts and other fraudulent practices and poor record-keeping (Maxwell et al. 2008: 15; Shipley 2022: 6).

For example, a US based NGO was forced to pay around US$5 million to settle allegations that it had violated procurement regulations when supplying humanitarian aid to Afghanistan and Pakistan and had failed to adequately monitor its sub-contractors who were engaged in corrupt practices (US Department of Justice 2014). In another incident into cross-border humanitarian aid to Syria, an investigation by the USAID Office of the Inspector General (2019: 5) found evidence of corrupt sub-contracting and procurement fraud affecting numerous Turkish suppliers including bid-rigging, kickback schemes, the use of shell companies and collusion with NGO employees (Slemrod & Parker 2016).

One area that presents particular problems in war-torn countries is conducting robust due diligence on suppliers to ensure that ownership structures are clarified so that any links to regime officials or designated organisations can be identified. For more on mitigating corruption in emergency procurement processes, see Schultz and Søreide (2008), Fazekas and Nishchal (2023) and Williams et al. (2022).

Sexual corruption

Humanitarian assistance is often delivered in an environment characterised by widespread sexual exploitation and abuse (SEA) (Donli 2020). Sexual abuse by armed groups and peacekeeping forces is well documented (Alexander & Stoddard 2021), but in recent years aid workers themselves have come under scrutiny (Flummerfelt & Peyton 2020). A report by the House of Commons (2017: 11, 19) concluded that such abuse is ‘endemic’, and noted that in Syria, sexual abuse and exploitation by aid workers at aid distribution points is an ‘entrenched feature’ of the lives of women and girls. Meanwhile, reporting by Kleinfeld and Dodds (2020) on the DRC indicates that accountability for SEA by aid workers can be rare as aid agencies’ reporting mechanisms are often ineffective and perpetrators pay off victims.

Despite these clear risk factors, aid agencies have historically been slow to respond to non-financial forms of corruption in humanitarian responses (Maxwell et al. 2008: 12). Growing voices are calling for some forms of SEA in war-torn regions to be recognised as sexual forms of corruption (Storey & White 2023). A particular risk is known as sextortion, where perpetrators with access to resources like food, medicines or shelter withhold this from people in need in order to psychologically coerce sexual acts from them.

Sexual violence was widely documented alongside other human rights violations during the recent Tigray War in Ethiopia. The conflict also created conditions in which food, medical supplies and fuel ran low in Tigray, which led to a desperate situation in which corruption flourished (Human Rights Watch 2022). In these conditions, sextortion appears to have been particularly widespread alongside other forms of conflict-related sexual violence (Mahderom 2022).

Multiple testimonies have been collected that, faced with scarcity and starvation, many women and girls were forced to turn to so-called survival sex, a problem compounded when many of them lost access to their money after banking services in Tigray were cut off by the federal government (Kassa 2022). Refugees International has recorded how soldiers as well as men in host communities exploited displaced women and girls, coercing them into sexual acts in exchange for food and small amounts of cash (International Rescue Committee 2021). According to interviews conducted by IRC with internally displaced persons, this form of sextortion became very common, and 60% of people questioned knew of women and girls who had to exchange sex for food or petty cash (International Rescue Committee 2021).

Typology of humanitarian aid delivery models

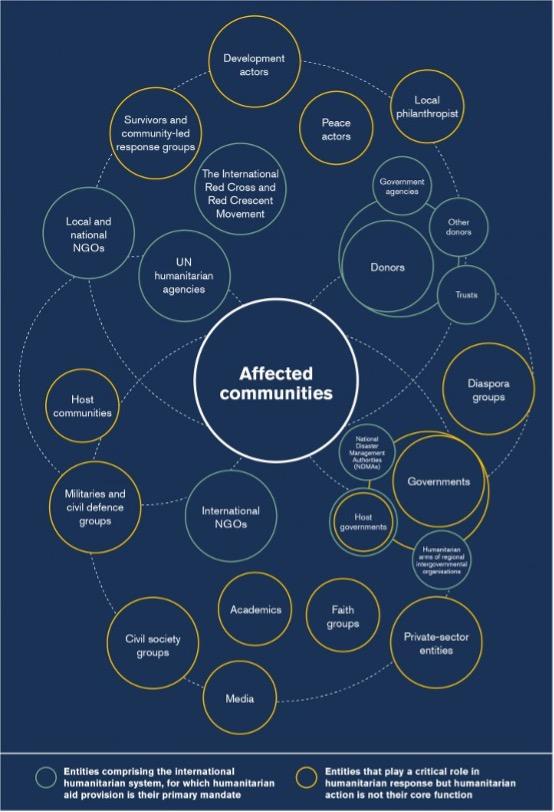

As Maxwell et al. (2008: 11) observed, the manner in which aid ‘delivery is contracted between various actors and the model of assistance all affect the nature and likelihood of corruption risk’. Different models entail different constellations of players, such as donors, aid agencies, implementing partners, sub-contractors, host governments, armed groups, local elites and affected communities, each of whom have differing interests and levels power (Bandstein 2007; Maxwell et al. 2012: 153).7195441814b2

Figure 2: Potential actors involved in humanitarian assistance

ALNAP 2022: 27.

ALNAP (2022: 55) points to the complexity of the humanitarian system, which encompasses around 5,000 distinct organisations and notes that there is ‘no systematic tracking of how money travels down the transaction chain to reach crisis-affected people’ (ALNAP 2022: 58). Cliffe et al. (2023: 31) also argue that the ‘the multiplicity of aid delivery channels and the lack of direct controls over them’ raises the risks of aid diversion and corruption. This section therefore sets out a simplified typology of different IHA delivery models, considering types of corruption that are especially salient to each.

Channel through government agencies

Humanitarian agencies may work in coordination with national or local government authorities to deliver assistance. This can involve providing support to government led relief efforts or partnering with government agencies to reach vulnerable populations.

In war-torn countries and contested territories, most government agencies are likely to be highly partisan. Cliffe et al. (2023: 54-55) therefore suggest that aid agencies prioritise engagement with any existing semi-autonomous institutions like national delivery agencies or development coordination bodies, which may be positioned to implement humanitarian programmes at arm’s length from senior political figures. In Yemen, for example, donors, the UN and the World Bank decided to channel substantial support through the country’s existing institutional infrastructure, chiefly the Social Fund for Development and Public Works Project. According to Cliffe et al. (2023: 54-55), ‘the political and financial independence of these institutions; their ability to operate on both sides of the conflict; and the existence of sufficient delivery and fiduciary controls’ made them reliable partners in the provision of basic services to vulnerable people across the country.

Cliffe et al. (2023: 58) also suggest that in conflict zones in which some degree of cooperation with national or local government authorities is possible, providing ring-fenced budget support to state entities that are able to operate impartially across political or military boundaries could be an option. In Burundi, for example, during a period of political ‘estrangement’ from the international community, ring-fenced humanitarian funding was able to ensure continued provision of healthcare to most of the population (Cliffe et al. 2023: 58).

However, in high-intensity conflicts, in which violence between well organised factions is entrenched, neither semi-autonomous agencies nor ring-fencing are likely to insulate IHA from systematic diversion by government authorities and other armed actors.

In the aftermath of the coup in Myanmar, for instance, local civil society vociferously criticised the international humanitarian response as being too closely aligned with the military junta. Among local activists, the feeling was that the price paid for access was not worth it as the military was able to co-opt and capture incoming aid (ALNAP 2022: 270). This demonstrates that the risks of aid diversion and embezzlement are likely to be particularly high where humanitarian assistance is channelled through government authorities. Cliffe et al. (2023: 3) thus recommend rigorous political economy analysis prior to any delivery partnerships with government actors, as well as the institutionalisation of monitoring by civil society groups and affected communities to quickly alert aid agencies to any misappropriation of aid.

Direct delivery by aid agencies

In 2022, nearly half of people in fragile and conflict-affected states were living in countries in which relationships between national authorities and major donors were adversarial (Cliffe et al. 2023: 2).1c95ff568be5 In many conflict settings, there is thus good reason to avoid direct partnerships with government agencies, and routing aid such that it bypasses government systems may reduce the risk of it being compromised by elite corruption (Cliffe et al. 2023: 31).

One option for aid agencies could be to directly establish their own delivery mechanisms in conflict areas, establishing direct channels to affected communities (Carr & Breau 2009: 16). This is reportedly the case in South Sudan, where UN agencies have a track record of implementing their own programmes (Haver & Carter 2016: 9).

While reducing the number of intermediaries can reduce the heightened risk of corruption involved in partnering with local organisations, it does not eliminate integrity management challenges internal to the aid agency, such as unethical practices in the management of personnel, supplies and budgets.

However, the primary limitation on direct delivery in conflict areas is typically the lack of local expertise, access and security threats to staff (ALNAP 2022: 110). Consequentially, aid agencies usually opt to partner with or sub-contract other organisations, including multilateral agencies, private companies and local NGOs (Carr & Breau 2009: 16).

Channel through multilateral organisations

Between 2012 and 2021, nearly 56% of humanitarian funding from government donors went to UN agencies, compared to 19% to NGOs and 9% to the Red Cross and Red Crescent (ALNAP 2022: 57). The World Food Programme, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees and UNICEF are the biggest players, with Haver and Carter (2016: 14) noting the UN’s comparative advantage in logistics, coordination capacity and wider legitimacy. Even in conflict zones in which it is hard for external actors to operate, such as Somalia and Syria, multilateral organisations do directly implement large programmes (Haver & Carter 2016: 30).

However, even where aid is delivered under the supervision of UN bodies or other multilateral organisations, there is clear evidence that corruption still occurs (Bergin 2023; Carr & Breau 2009: 18). In 2019 the World Health Organisation was forced to investigate allegations that in its Yemen operations ‘unqualified people were placed in high-paying jobs, millions of dollars were deposited in staffers’ personal bank accounts, dozens of suspicious contracts were approved without the proper paperwork, and tons of donated medicine and fuel went missing’ (Michael 2019).

Another recent investigation by the Guardian reported that while UNDP carries out projects in Iraq directly and promises donors higher integrity standards than those provided by Iraqi government institutions, its staff were demanding kickbacks of up to 15% in exchange for helping businesses win contracts for reconstruction projects (Foltyn 2024).

Contracting work from the private sector

Many aid agencies rely on private sector companies to transport aid or provide security in conflict-affected countries, especially where they perceive the recipient government to be corrupt or unreliable (Wood & Molfino 2016: 4). While some of these entities may be registered in the conflict-affected country itself, much of the value of these contracts goes to firms in donor countries; in 2020, four-fifths of US foreign aid contracted to companies and non-profits went to US firms (Kenny 2024b). Beyond the potential problems of tied aid, this underscores the potential integrity risks in aid agencies’ procurement processes where cosy relationships develop with certain suppliers.

In-country, Haver and Carter (2016: 46) point out that there is very little evidence about the volume of illicit funds that commercial transport companies contracted by aid agencies may pay to armed groups. Nonetheless, an internal USAID investigation found evidence of ‘systemic weaknesses’ on the part of commercial vendors in the ‘procurement, storage, handling, transportation, and distribution of pharmaceuticals and medical supplies purchased for use in Syria’ (USAID Office of the Inspector General 2018: 41).

A study by Transparency International (2017) of humanitarian aid provided to Syrian refugees in Lebanon found that aid agencies who had sub-contracted operations to private companies were more exposed to corruption risks due to a lack of transparency around how funds were managed, which led the agencies to work increasingly with local NGOs.

Channel through local NGOs

There are widespread calls for greater ‘localisation’ in the delivery of aid, including in conflict zones (Duclos et al. 2019; Haver & Carter 2016; Slim 2021; Svoboda et al. 2018). Local NGOs are an important vector for aid delivery in war-torn countries as they have unrivalled knowledge of the operational environment and local legitimacy. Haver and Carter (2016: 66) argue that, given they are essential for access, aid agencies should ‘tolerate a higher level of fiduciary risk from those who have the ability to reach people safely’.

In practice, virtually all actors providing humanitarian relief tend to partner with local NGOs, who are invariably on the frontlines in the most dangerous areas (Haver & Carter 2016: 29). Partnerships with NGOs can take numerous forms, from helping to conduct needs assessments up to creating ‘shadow state administrative systems’ where central government authority has collapsed (Cliffe et al. 2023: 59).

The evidence is mixed in terms of whether channelling aid via NGOs increases or decreases corruption risks. In non-conflict settings, empirical studies indicate that aid recipients may consider NGO staff to be less corrupt than government officials (Baldwin & Winters 2020). Both Cliffe et al. (2023: 60) and Haver and Carter (2016: 11) conclude that contracting with NGOs in conflict zones is not consistently associated with either higher or lower rates of corruption or mismanagement than other delivery modalities. Slim (2021) concurs, though notes that many local NGOs ‘operate on personal preference and political network more than they do by professional conduct’. As an example, he alleges that several national societies of the Red Cross and Red Crescent network function as ‘hereditary family firms’, while others are ‘run by political cliques’ (Slim 2021). Haver and Carter (2016: 48) contend that partnering with national NGOs in Syria whose staff were not from the part of the country in which the aid was delivered was associated with reduced bias and favouritism in aid delivery.

Specific corruption risks related to contracting with local NGOs relate to the partner selection process, which could be unduly influenced by kickbacks to aid agency staff or offers of employment (Shipley 2022: 6). Particularly in conditions of remote management where aid agency staff have been withdrawn from the field due to security concerns, it can be difficult for them to assess the performance and integrity of local NGOs. On the other hand, NGOs may have incentives not to report integrity breaches, especially where they fear losing funding as a result (Darden 2019b).

Channel through local communities

A further option for aid agencies is to seek to work with affected communities directly, by engaging local community leaders, volunteers and community based organisations. In Somalia, Haver and Carter (2016: 46) found that international aid agencies were ‘increasingly partnering more with smaller community based organisations, such as local farming cooperatives or youth groups, in order to bypass perceived corruption problems with NGOs’. Guggenheim and Petrie (2022) argue that community based aid models have been implemented successfully in a range of fragile and conflict-affected countries.

Cliffe et al. (2023: 51) define community based approaches as humanitarian interventions that ‘transfer development funds directly to a local governance body that is not dependent on the national administrative system’. These bodies could include local councils, traditional leaders or autonomous village governments.

As these initiatives involve direct transfers to local communities, they potentially limit financial complexity, bypass intermediaries and bureaucratic hurdles and reduce the risk of capture by regime officials or armed actors. In fact, Guggenheim and Petrie (2022: 17) argue that community based models are ‘the form of aid delivery where efforts to divert or capture aid resources meet the most opposition from local-level actors’. They point to the example of Pashtun communities in Afghanistan whose funds were stolen by Taliban fighters and who travelled to the Taliban headquarters to successfully demand their money back (Guggenheim & Petrie 2022: 13). Nonetheless, community based approaches may increase security risks for local communities in some countries, as in Myanmar where direct transfers to communities in opposition controlled territories reportedly made them targets of military aggression and predation (Cliffe et al. 2023: 53).b6c33a03bfc1

As community based programmes usually involve an element of community monitoring, they have certain advantages in terms of verifying the quantity and quality of aid received (Wong & Guggenheim 2018). There are nonetheless specific corruption risks. While the small size of grants provided to each community may limit large-scale diversion or leakage (Guggenheim & Petrie 2022: 11), this could complicate oversight and increase the risk that sanctioned entities are able to access funds (Cliffe et al. 2023: 53).

More generally, the rollout of these programmes at the community level may be more susceptible to reproducing local power hierarchies. Maxwell et al. (2008: 9) points out that community structures can be ‘both indigenous and corrupt at the same time’, excluding minorities and channelling the lion’s share of aid to dominant groups. In Syria, for instance, aid agencies have reported that the use of community development councils resulted in significant small-scale corruption in beneficiary selection (Haver & Carter 2016: 53).

Non-state armed actors

In general, populations in conflict-affected countries living in areas controlled by non-state armed actors receive less humanitarian aid than those in areas under government control (ALNAP 2022: 112). This is partly due to counter-terrorism laws that limit aid agencies’ ability to work in those areas, as well as the radical nature of many of those armed factions (ALNAP 2022: 114).

Nonetheless, in some scenarios, aid agencies may be forced to engage with non-state armed actors because they are more powerful than the local administration and control access to and information about the population in need of assistance (Haver & Carter 2016: 66; Maxwell et al. 2012: 153). In Idlib province in Syria, Rasella (2023: 14) states that aid organisations are required to register with an ‘NGO office’ as part of the opposition Syrian Salvation Government’s Ministry of Development and Humanitarian Affairs, which is used to ‘exert supervision over aid delivery’. More generally, in Syria, there is reportedly extensive overlap between armed and unarmed actors, with local councils, relief committees and even Sharia courts acting as intermediaries. For instance, local council members have been known to transport aid from the Turkish border, with members of armed groups accompanying the convoys as a form of ‘protection’ (Haver & Carter 2016: 60).

A household survey among aid recipients in Syria reported that in some regions humanitarian assistance was delivered directly by armed opposition groups. It is unclear whether the resources they distributed had been procured by these groups themselves, collected from private donors or were in fact goods that they had stolen from other aid agencies (Haver & Carter 2016: 30).

While cooperation between intended beneficiaries and armed groups may facilitate the delivery of aid, the extensive involvement of these groups entails clear risks. These include aid agencies or their local partners paying money at checkpoints, paying protection money or unofficial ‘taxes’, being compelled to employ local militia and agreeing to prioritise certain communities over others (Haver & Carter 2016: 50).

Role of intermediaries and informal networks

Humanitarian assistance is just one source of inward resource flows into crisis regions, alongside remittances and other revenue streams that form a complex and entangled web of support networks for affected communities. These broader support networks are often poorly understood by aid agencies (ALNAP 2022: 70).

Nonetheless, various intermediaries – including local businesspeople, landowners, government officials and religious leaders – play a complex role as gatekeepers who can simultaneously ‘exploit local populations while also helping to bring assistance to them and lobbying aid providers on their behalf’ (Haver & Carter 2016: 52). Humanitarian actors based in Turkey, for instance, have relied on local councils in Syria as intermediaries between aid agencies, diaspora communities, beneficiaries and armed groups (Haver & Carter 2016: 46), including to negotiate security guarantees for aid projects (Zürcher 2019: 849).

In the DRC, a UNICEF programme was undermined by an organised corruption scheme that involved community leaders inflating the number of affected people to NGO staff. Local businesspeople then purchased ID cards from hundreds of people unaffected by the crisis and bribed aid workers to falsely register them for support. The cash payments for fake beneficiaries were then split between the businesspeople and community leaders (Henze et al. 2020).

To mitigate these kind of risks, Zürcher (2019: 849) recommends that aid agencies invest time and resources into political economy analyses to better understand the role of gatekeepers and informal networks in local power constellations.

Potential safeguards

There are many potential anti-corruption safeguards that could be relevant to international humanitarian assistance, including risk management approaches, preventive policies and punitive measures. Due to the limited scope of this Helpdesk Answer, it focuses two main areas: remote monitoring and downward accountability.

Remote management

The UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs defines remote management as ‘the withdrawal for security reasons of international staff and the transfer of program responsibilities to local staff or partner organisations’ (Howe et al. 2015: 6). Fortunately, despite the lack of presence in the field, various options exist for aid agencies to remotely monitor aid distribution and evaluate programme outcomes.

- Biometric data: fingerprints and iris scans can be used to register and verify aid recipients’ unique identity. This can be useful in situations in which beneficiaries lack formal identification documents and can help reduce duplication and fraud as this data is less vulnerable to manipulation than paper documentation. To date, aid agencies have used biometric methods to register 4.4 million refugees in 48 countries, with successful use cases reported by both UNHCR and the WFP assisting Syrian refugees in Jordan (Hill 2023). Nonetheless, potential problems relate to privacy and protection of this type of sensitive data, not least in volatile conflict settings. In fact, Rahman et al. (2018) conclude that ‘the potential risks for humanitarian agencies of holding vast amounts of immutable biometric data – legally, operationally, and reputationally, combined with the potential risks to beneficiaries – far outweigh the potential benefits in almost all cases’. They contend that while they can speed up the registration process, typically alternative and less problematic approaches are available. In Yemen, the WFP tried to introduce a biometric registration system for aid recipients, but opposition by the Houthi group led the WFP to partially suspend food aid to the country (Darden 2019b).

- Blockchain: in principle, distributed ledger technology can create transparent and tamper-proof records of aid transactions, including cash transfers, procurement contracts and supply chain management. This could assist with record-keeping and anti-fraud safeguards. However, a recent literature review found that to date only a few pilot programmes have been deployed in the field and limited empirical evidence exists regarding the real-world application of the technology (Hunt et al. 2022). Zwitter and Boisse-Despiaux (2018) also point to blockchain’s ‘potential to perpetuate societal problems’ in the humanitarian sector.

- Crowd-sourcing via mobile data: information on humanitarian needs and beneficiary profiles can be collected from target communities via mobile networks (Hees et al. 2014: 139). SMS and internet based tools can allow target communities to report the receipt or absence of humanitarian aid and raise allegations of corruption, but this approach relies on functional and secure communications infrastructure.c787598ac0a5

- Drones: increasing attention is turning to application of drones in delivering, surveying and monitoring humanitarian assistance, though their use is not yet widespread(Rejeb et al. 2021).

- Geographic information systems (GIS): these mapping tools can help visualise and analyse spatial data, including the location of aid distribution points, health facilities, water sources and vulnerable populations. GIS can help identify gaps in service delivery and optimise resource allocation, and many UN agencies have specialised GIS teams (Ortiz 2020). Chege (2024) argues that GIS has multiple applications in the humanitarian sector, including assisting refugees with resettlement, logistics and planning, conflict analysis, impact and risks assessments, and monitoring and evaluation. In 2017, the Lebanese Red Cross used satellite imagery and GIS to plan escape routes for people fleeing fighting along the country’s border with Syria and to track minefields (Lanclos 2019). In Kenya, a web based platform called Ushahidi has been used to map election violence (GIS at Tufts 2024). For further information about potential applications of GIS in humanitarian assistance, see Humanitarian GIS Hub (2024).

- GPS shipment tracking: in-kind aid can be barcoded and scanned at each phase in the supply chain, a technique that has been used in northern Syria (Howe et al. 2015: 34-36).

- Partnerships: taking proactive steps to seek out high-quality partners to monitor the distribution of humanitarian aid in situations of remote monitoring is thought to be crucial (Howe et al. 2015: 7). Hees et al. (2014: 139) recommend working through established local partnerships and including clear terms of reference and anti-corruption clauses in contracting arrangements. Haver and Carter (2016: 10) found that the most effective aid agencies invest considerable organisational resources into building capacity of national staff and partners to conduct oversight. Verbal reports and debriefing meetings with local partners are useful techniques to collect up-to-date information about partner activities (Howe et al. 2015: 34-36).

- Photos and videos of distribution: have been widely used in Somaliland and Syria and typically include geotagging photos to verify data and location. While this can allow for real time monitoring, it does not always guarantee the aid reached intended beneficiaries (Howe et al. 2015: 34-36). Potentially, remote surveillance cameras could be installed at aid distribution sites and warehouses to deter theft, diversion or misuse of humanitarian resources.

- Satellite imagery: can be used to monitor changes in vegetation, land use, population movements, infrastructure and even minefields in conflict-affected areas (Braun 2019; Guida 2021; Ibrahim et al. 2021). In Somalia, local aid organisations have been able to provide donors with before-and-after images of completed projects, GPS coordinates and satellite imagery to verify work in areas controlled by al-Shabaab (Haver & Carter 2016: 38).

- Social media: a study by Transparency International (2017) found that social media offered good opportunities for communication with affected communities and provided an alternative mechanism for complaints and whistleblower disclosures. Social media monitoring may also lend insights into humanitarian needs and public perceptions in conflict zones.

- Third-party monitoring (TPM): is typically conducted by NGOs or private firms with the expertise and local knowledge to verify claims made by local project partners (Hees et al. 2014: 139). The focus is chiefly on financial accountability issues rather than programme outcomes (Cliffe et al. 2023: 63). According to Cliffe et al. (2023: 53), third-party monitoring was able to effectively assess the efficacy of World Bank fiduciary controls in areas of Afghanistan where Taliban presence made direct oversight too dangerous. Conversely, the World Bank (2022: 15) has had less positive experiences with TPM in Yemen, due to poor reporting quality, the low number of qualified firms and limited access to conflict areas. The World Bank concludes that TPM should be used in conjunction with technological monitoring mechanisms and community monitors and go beyond spot checks to include technical audits and monitoring of the implementation of procurement plans (World Bank 2022: 15).

In practice, curbing corruption risks in IHA is likely to require a combination of the above approaches. For example, after detecting a series of corrupt practices in their cross-border humanitarian assistance to Syria, USAID instituted post-award vetting of suppliers, heightened third-party monitoring, added new anti-corruption clauses to suppliers’ contracts and required partners to submit corruption risk assessments and mitigation plans (USAID Office of the Inspector General 2019: 2). For more detailed evidence-based guidance for aid agencies partnering with local organisations in remote monitoring situations in Syria see Howe et al. (2015).

Downward accountability

The anti-corruption and fraud prevention measures described above could help aid agencies to account to donors for the money spent. Yet Haver and Carter (2016: 50) stress that this type of upwards accountability should not come at the expense of downward accountability to affected communities. Indeed, they point out that generally, local communities in conflict settings are dissatisfied with their level of involvement in the design and rollout of humanitarian programmes. In fact, 85% of aid recipients surveyed stated that they had never been consulted about the assistance they receive (Haver & Carter 2016: 65). In Syria, the lack of consultation with intended beneficiaries reportedly led to a situation in which a significant proportion of in-kind aid did not meet local needs and was sold by recipients to raise cash to buy items they really required (Haver & Carter 2016: 65).

Aid agencies are increasingly expected to adhere to the Accountability to Affected People (AAP) framework. This calls for humanitarian actors to take account of, give account to and be held to account by people affected by a crisis, including those ‘unintentionally excluded from receiving assistance, which often happens to marginalised groups including people with disabilities, older persons, and LGBTI group’ (IOM 2019). The AAP framework stresses the importance of sharing timely and actionable information with communities, supporting the meaningful participation and leadership of all affected people, and ensuring feedback systems are in place to enable communities to assess and comment on the performance of humanitarian action, including regarding corruption and SEA.

Komujuni and Mullard (2020) likewise emphasise the importance of downward accountability mechanisms to improve the appropriateness, targeting and efficiency of humanitarian assistance. They recommend that intended beneficiaries are involved in the design and rollout of these mechanisms, and aid agencies make a concerted effort to communicate the function and availability of these channels.

Ultimately, meaningful dialogue and consultation should include – where possible – broader communities and not just rely on information provided by ‘communityleaders’ and other gatekeepers (Haver & Carter 2016: 64). In fact, it is increasingly recognised that participatory methods need to be designed in a truly inclusive manner. One example is a study that engaged fifty-five Syrian and South Sudanese refugee women and girl as co-researchers to generate evidence on how to make the distribution of aid safer (Potts et al. 2022).

Beyond consultation and community based monitoring approaches, another important consideration relates to whistleblowing and grievance mechanisms. Hees et al. (2014: 52, 139) state that affected communities should be made aware of complaints mechanisms, how they operate, how to file grievances, the investigation process and potential outcomes. Various channels can be established, including complaints boxes and hotlines. In Uganda, for instance, UNHCR has set up a feedback, referral and response mechanism that provides a helpline and call centre for refugees to raise concerns, and report corruption, violence, sexual assault and other wrongdoing (Komujuni & Mullard 2020). Complaints boxes have also been used in northern Syria, but there aid agencies rely on local partners to distribute and collect the boxes, which may be being watched by armed actors (Howe et al. 2015: 34-36). Shipley (2022: 11) observes that an increasing number of aid agencies are taking steps to protect staff, partners or recipients who report corruption or misconduct from retaliation. Nonetheless, evidence suggests that complaints processes in humanitarian settings are often deeply flawed (IASC 2012). IASC (2021: 32) notes that complaints boxes have been found to be inappropriate for reporting forms of SEA (potentially including sexual corruption) in some settings and increasingly being replaced by hotlines.

As a final reflection, Haver and Carter (2016: 68) appeal to aid agencies to speak more openly about the challenges of corruption and aid diversion they face in conflict settings. In their view, this can facilitate productive discussions between aid agencies and local staff and assist in the development of principled, pragmatic approach to delivering international humanitarian aid in war zones.

- The relative weight of international humanitarian assistance compared to other inbound resources to crisis-affected countries varies widely. For instance, in 2019 humanitarian assistance accounted for only 1.3% of resource flows to Bangladesh, but 46% of flows to Yemen. In general, humanitarian assistance is a more prominent component of resources sent to conflict-affected countries relative to countries affected by other types of crises (ALNAP 2022: 71).