Corruption during Covid-19: trends, drivers, and lessons learned for reducing corruption in health emergencies

The global response to Covid-19 is far from over. Governments have allocated substantial resources to address the crisis and will continue to do so as the virus evolves and causes periodic flare-ups of infections and deaths. These resources have been and will continue to be vulnerable to corruption, with deleterious effects on the world’s most vulnerable people.

Based on desk-based research between January 2020 and October 2022, the U4 Issue Corruption during Covid-19 recounts how corruption materialised during Covid-19, what drove it and how it impacted people. It also highlights anti-corruption strategies deployed and lessons learned for use in other health emergencies.

Trends and manifestations of Covid-19 corruption

Petty corruption in service delivery: Examples of corruption – such as sales of falsified Covid test certificates and vaccines, bribes, and queue-jumping to access Covid vaccines, and price gouging and profiteering – were found in South Africa, Lesotho, the UK, France, Spain, Malaysia, the Philippines, Peru, Argentina, Poland, Canada, Ecuador, India, Venezuela, and Iran.

Procurement corruption and embezzlement affecting health financing: Procurement corruption was responsible for the loss of key Covid financial resources in Cameroon (US$333 million), Malawi (US$1.3 million), South Africa (US$910 million), Nigeria (US$96000), and Uganda (US$528000). In Malaysia, the Anti-Corruption Commission opened 25 investigations over alleged Covid-related procurement corruption. In Bangladesh, corruption was prevalent in the procurement of Covid vaccine doses. Additionally, Covid-19 funds were allegedly embezzled and/or mismanaged in Afghanistan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Cameroon.

Grand corruption weakening health governance and leadership: State capture siphoned off much-needed resources from the Covid response. In Viet Nam, foreign ministry, tourism, air, medical, and manufacturing officials were arrested over allegations of corruption scandals and mismanagement of Covid funds. In Brazil, Covid corruption implicated members of Bolsonaro’s administration and key allies. In Kyrgyzstan, Zimbabwe, South Africa, Bolivia, and Honduras, former ministers of health and other high-level government officials were arrested because of their involvement in Covid-related grand corruption schemes.

Growing black markets, falsified medical products and lack of clinical trial transparency: Falsified versions of Covid-19 vaccines were found in Mexico, Poland, Iran, India, and China. Schemes to sell falsified records of Covid-19 vaccine status were discovered in Saudi Arabia,Canada, Hong Kong, Germany, and the US. Worldwide, there was a 257% increase in fake vaccination cards being sold online via the Telegram app. Additionally, the manipulation of clinical trials for Covid-19 vaccines eroded public trust and endangered people’s access to safe and good-quality health products.

Data manipulation and misuse affecting health management information systems: Governments manipulating data on Covid-19 infections and death rates created a mismatch between reality and official accounts in Brazil, India, the Philippines, Tanzania, Zambia, and Venezuela.

Opacity and corruption in health workforce management: Health workers would sometimes engage in ‘functional’ corruption, such as bribes and thefts, to protect themselves and/or secure a minimum living wage. The theft of medical products in hospital facilities was documented in Uganda, Rwanda, and Ghana.

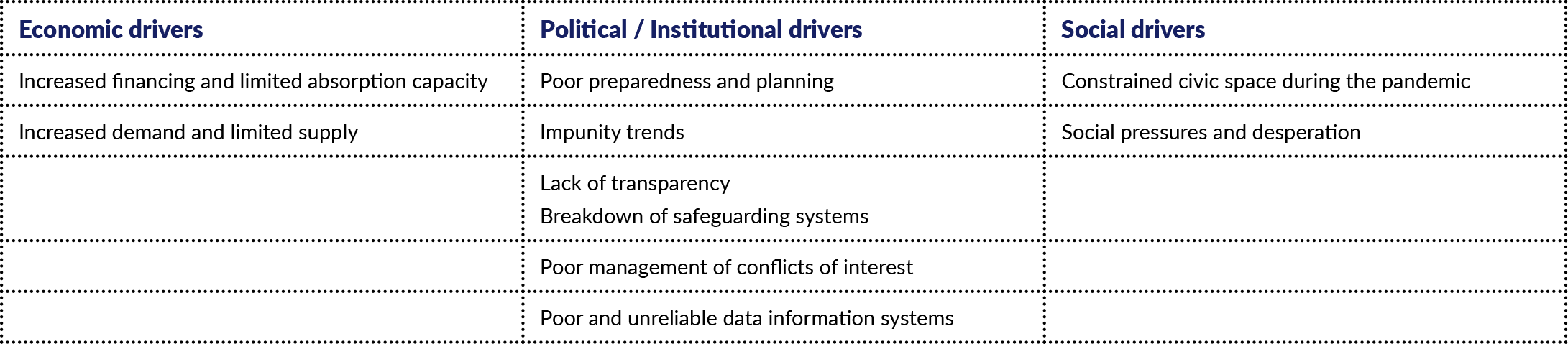

Corruption drivers during Covid-19

How Covid corruption impacted people

Inequality in healthcare access left marginalised groups more vulnerable to experiencing Covid corruption. Their experiences included being victims of bribery, overcharging, sextortion, and having to make other informal payments. They also experienced having limited access to quality medicines and were more prone to acquiring substandard and falsified medical products in the black market.

Covid corruption had an acute impact on women, because of gendered power differentials and the large role they play in providing care for their families. As patients and caregivers for infected family members, women had a higher likelihood of being in contact with public service providers, making them more vulnerable to corruption. Despite women representing 70% of the workforce in the health sector and occupying a large share of the service industry and the informal economy, they were underrepresented in decision-making bodies.

Strategies deployed to address Covid-19 corruption: what worked and what didn’t?

Service delivery – Tackling petty corruption with tech-based solutions: The adoption of tech-based solutions to tackle petty corruption, such as bribes and theft, has increased in LMICs. Yet, their effectiveness depends on how their design responds to the problem at hand in a particular country context and if the technology is supported by measures that ensure digital insights are turned into action.

Health financing – Bottom-up and top-down approaches: Anti-corruption interventions in health financing can benefit from bottom-up approaches. Civil society, for example, can play a complementary role as a watchdog to monitor procurement processes. Top-down approaches are also key for enhancing transparency. Several countries enhanced their institutional capacities to track Covid spending, including Rwanda, Pakistan, Benin, and Sierra Leone.

Medical products, vaccines, and technologies – Enhancing medical products’ quality across supply chains using blockchain: Despite its promising applications, blockchain’s potential as an anti-corruption tool during Covid-19 was limited. First, the pandemic was characterised by quick and shifting priorities, which truncated its rapid deployment to monitor different supply chains. Second, several countries did not meet all the key conditions for using blockchain technologies to enhance transparency in medical supply chains: political stability, collaboration among relevant interest groups, responsive legal frameworks, and technological capacity.

HMISs – Their role in enhancing decision-making: More than 40 countries used DHIS2, a free and open-source HMIS, for Covid-19 surveillance and 40 countries used it for Covid-19 vaccine delivery. Nonetheless, using DHIS2 or using another HMIS is no guarantee that data will not be misused or manipulated for private gain. Strong data governance is crucial to ensure that data collection, management, and use are ethical and equitable, and help promote better decision-making.

Human resources: The research conducted here did not find any clear indication of preventive measures taken to actively deter corruption in the selection of healthcare personnel, improper use of medical equipment and products, bribes, and absenteeism during Covid-19.

Lessons learned from Covid corruption

- Transparency in decision-making during health crises is crucial at the district, national, and global levels.

- Health emergencies-related anti-corruption initiatives should integrate a gender perspective.

- Healthy financial accounts require reliable public financial management, including public and user-friendly platforms to track funds and disseminate financial information, legislation to ensure due diligence and document conflicts of interest, as well as free civic space and well-established government institutions that can keep spending in check.

- Civil society can still play its monitoring role when space is constrained, physically and legally. Development practitioners can support this through the establishment of digital accountability networks.

- Strong data governance is essential for enhancing transparency, accountability and integrity of data collected during health emergencies.

- There needs to be more attention on protecting health workers and addressing the drivers of functional corruption, as well as petty corruption engendered by social norms.

- The private sector also engages in state capture, procurement corruption, and lack of transparency in clinical trials. There should be tailored anti-corruption measures aimed at drug manufacturers and private healthcare providers.

- Mainstreaming anti-corruption during health emergencies requires an institutional commitment from governments to adhere to anti-corruption principles within national, and global pandemic plans and policies, as well as context-driven measures in collaboration with all interest groups.