Query

Please describe suspected cases of corruption involving multilateral organisations.

Caveat

On several occasions, this Helpdesk answer refers to allegations of corruption or misconduct made by third parties but not proven in a court of law. Both Transparency International and U4 keep distance do not take a position on the veracity of the allegations discussed here. They are nonetheless referred to as they illustrate some of the types of corruption risks that multilateral organisations must manage.

For some of the cases described in the paper, investigations and institutional responses are ongoing. The author has attempted to establish the status of the case at the time of writing with reference to information available in the public domain. In this regard, it is important to note that reports and outcomes of internal investigations conducted by multilateral organisations are often kept confidential.

Introduction

Within international development, bilateral donors typically channel a large part of their national aid budget through multilateral organisations such as United Nations (UN) agencies and multilateral development banks (MDBs) such as the World Bank (Nicaise 2022).d521857da1cb

Grigorescu (2013: 183) argues that prominent cases of corruption and mismanagement of funds in the 1990s and 2000s – such as the UN Oil-for-Food Programme – led to calls for greater oversight of multilateral organisations. With this, anti-corruption and integrity measures were embraced by such organisations (Rahman 2022; Kohler and Bowra 2022).8e60ef6f6d7b

Despite this, cases of suspected corruption involving multilateral organisations have continued to emerge and be reported on in recent years; to the extent that Krys (2016) argues these instances should not be treated as “isolated incidents.”

Corrupt acts can be perpetrated by multilateral organisations’ own personnel (staff and executive-level actors), but also external third-party partners (Jenkins 2016: 1). Multilateral organisations often depend on such third parties to acts as suppliers for and implementers of projects, and indeed donors expect the multilaterals to manage any risks posed by those entities they partner with (Nicaise 2022); this can include private sector actors, but also national government actors (Weinlich et al. 2022: 134).

Many multilateral organisations publish aggregate statistics disclosing corruption or mismanagement cases (Chêne 2019: 1). For example, in 2022, the World Banks’s oversight entity – the Integrity Vice Presidency (INT) – stated it had received 3,380 complaint submissions, leading it to sanction 35 firms and individuals (World Bank 2022: 2). However, this aggregated form of reporting is not best suited to interpreting the causes and effects of individual cases.

Most major multilateral development banks (MDBs) publicly list third-party firms or individuals found guilty of misconduct who are debarred from participating in the projects financed by MDBs (Jenkins 2016: 2). Yet beyond listing sanctioned and debarred third parties, multilaterals rarely publicly disclose information on the specific details of incidents of corruption, such as the amounts involved, nature of the wrongdoing and remedial action taken (Rahman 2022).

In particular, multilateral organisations tend to comparatively disclose less information on wrongdoing by their own personnel, purportedly out of concern for protection of sensitive information (OIOS 2015: 81). For example, the UN’s internal oversight body - the Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS) - does not make publicly available reports relating to its investigations under normal circumstances (OIOS 2015: 81).

Furthermore, many staff members of multilateral organisations are granted immunity from domestic prosecution (Krys 2016); this means that there are rarely public court records available regarding suspected cases. Taken together, these factors make it challenging to analyse the causes and effects of individual cases based solely on information disclosed by multilaterals themselves.

This Helpdesk Answer thus adopts a case study-based approach drawing on a wider range of sources, especially media investigations. For each case described below, the author attempted to determine, to the extent possible, the facts, the triggers and underlying factors, the impact on stakeholders, and the responses from multilateral organisations and donors.

Before turning to the specific cases, it is important to emphasise that each multilateral organisation typically has its own anti-fraud and anti-corruption policies (Nicaise 2022), meaning one should be cautious of generalising.Indeed, a 2016 report by the UN’s independent external oversight body – the Joint Inspection Unit (JIU) – found that while some UN system organisations were making concerted anti-fraud efforts, others were in “a state of near denial with regard to fraud” (Bartsiotas and Achamkulangare 2016: iv).

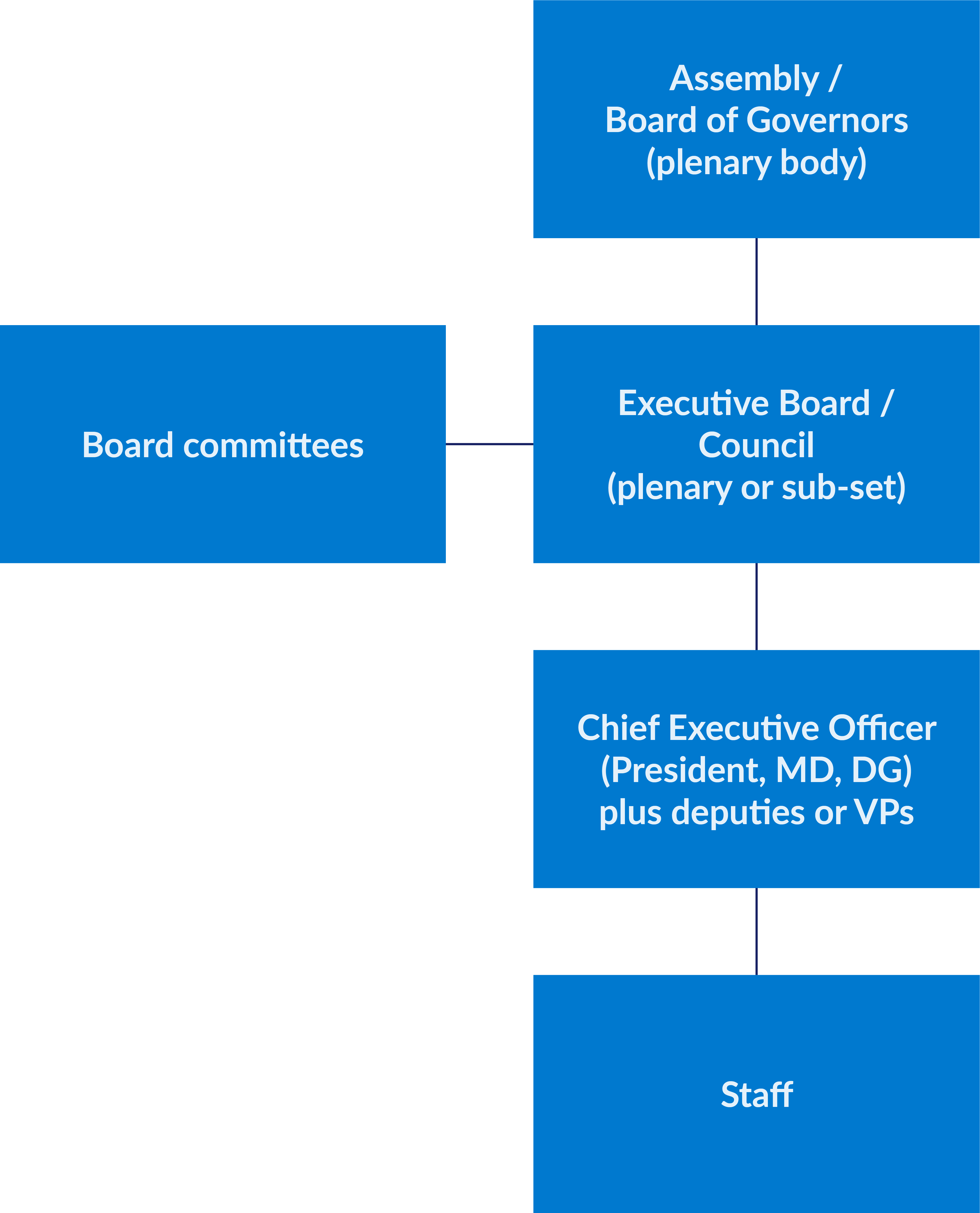

Nevertheless, some basic characteristics of multilateral organisations. While the exact institutional setup of multilateral organisations can differ greatly (Martinez-Diaz 2009: 86), they do typically share some key elements (see Figure 1).

Here, donor/shareholder representation and inputs are often accounted for in a plenary body or an executive board structure (that may comprise of different committees) that have governing functions, while normal operations are led by an executive (for example, a director) working together with the staff body may be divided across different headquarter, regional and field offices, making up a typically long chain of command.

The case studies described below were deliberately selected to illustrate risks both from within the organisation at different levels as well as risks emanating from third parties. They were also selected on basis of the availability of reliable information, how recently the alleged events took place, and the aim to have diverse geographical representation.

Figure 1: Typical Governance Structure of an Intergovernmental Organisation.

Source: Martinez-Diaz (2009: 86)

UNOPS and S3i initiative (Case #1)

Facts

The United Nations Office for Project Services (UNOPS) is a United Nations agency, describing itself as providing “infrastructure, procurement and project management services for a more sustainable world.” UNOPS functions uniquely within the UN system, because it receives fees from fellow agencies to provide them with such services to support the implementation of development projects (Ainsworth 2022a).

Through this model, UNOPS accumulated a significant surplus of reserves – increasing from US$ 159 million in 2017 to 360 million in 2021 (KPMG 2022b). It dedicated a portion of these reserves towards an impact investing initiative called Sustainable Investments in Infrastructure and Innovation (S3i) (Ainsworth 2022a). Under S3i and the leadership of its Chief Executive Vitaly Vanshelboim, UNOPS entered contracts worth more than US$59.7 million with Singapore-based construction firm SHS Holdings and affiliated companies (KPMG 2022b: 7), including a contract to attract private investors and build more than one million sustainable and affordable housing units in six developing countries (Ainsworth 2022a).

In 2022, former UN official Mukesh Kapila began blogging about alleged fraud within S3i, which led to subsequent coverage by media outlets Devex and the New York Times (Courtney 2022; Fahrenthold and Fassihi 2022). They highlighted that SHS Holding had not built any of the promised housing units and had failed to attract any private investors to the initiative (Gridneff 2022). This led to allegations of misconduct in S3i’s selection of SHS Holding due to the firm’s reported lack of prior experience in delivering large projects. Suspicions were also raised that members of the same family were behind both SHS Holdings and an ocean conservation initiative that received US$3 million in funding from UNOPS (Fahrenthold and Fassihi 2022).

Grete Faremo, Executive Director of UNOPS, resigned in May 2022 in response to the scandal (Courtney 2022). Vanshelboim was placed on administrative leave and following an internal accountability process was separated from service in January 2023 (UNOPS 2023a).

In 2022, the UN Office of Internal Oversight Services (OIOS) launched an independent internal investigation into S3i, which at the time of writing has not been made public. In August 2022, UNOPS commissioned two independent external advisory reviews to be carried out by the firm KPMG: the first review focused on “identifying the root causes and institutional vulnerabilities within UNOPS that led to the failures associated with S3i”, while the “second forward-looking review [focused] on UNOPS’ mandate, governance, risk management and internal control systems, performance management and accountability, and includes an assessment of the portfolio and cost structures” (KPMG 2022a).

Triggers and Underlying Factors

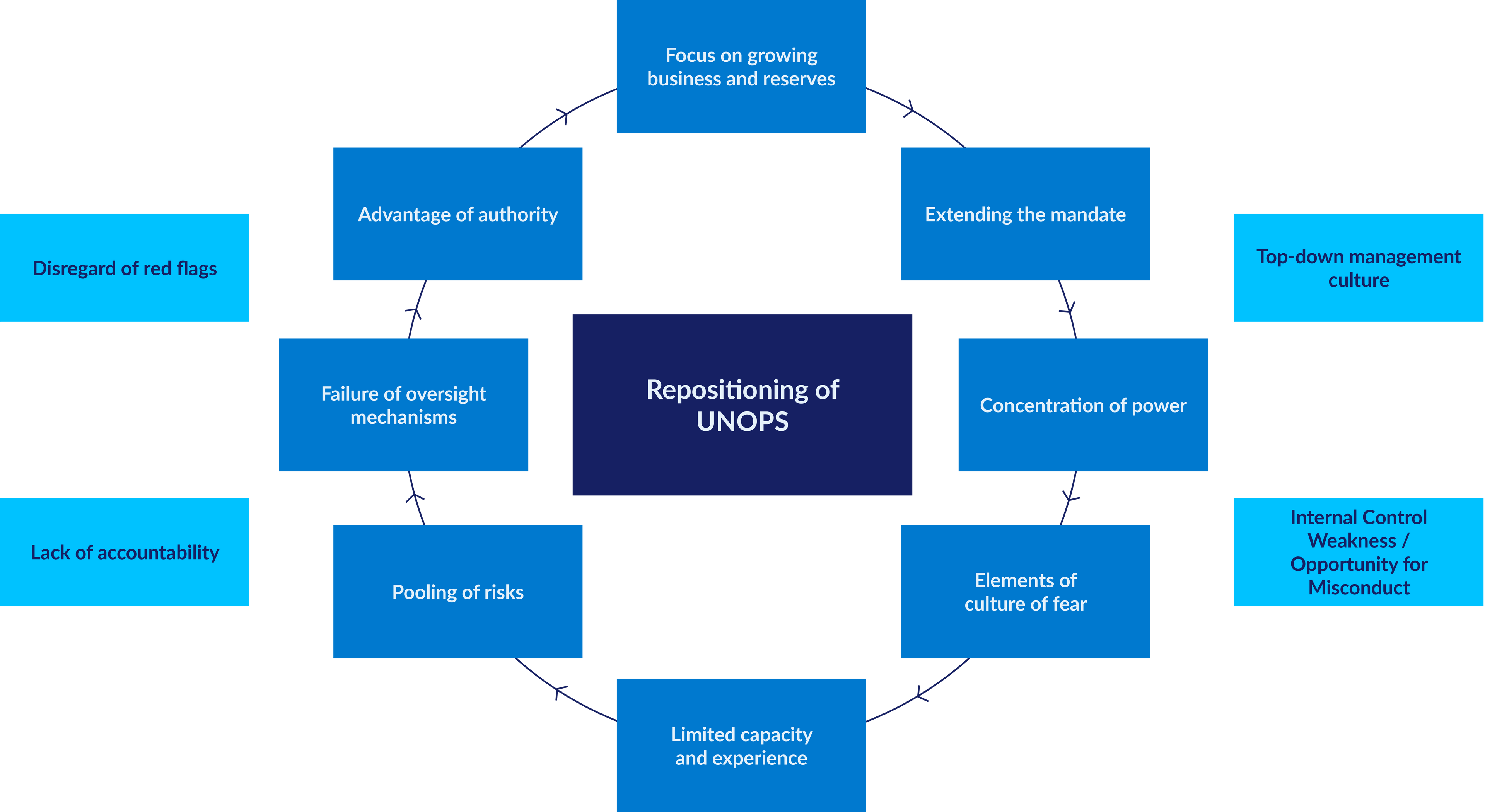

In its independent review, KPMG identified numerous root causes and vulnerabilities leading to the failures of S3i following an institutional “repositioning” UNOPS underwent in 2014 (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Root Causes and Institutional Vulnerabilities Associated with S3i Reported Failures.

Source: KPMG (2022b: 11).

It highlighted the following four points:

- A top-down management culture, in which power was highly concentrated with senior-level officials whose focus was primarily on business expansion (KPMG 2022b: 16)

- Internal control weaknesses, whereby staff had limited experience in due diligence and vetting (KPMG 2022b: 6)

- Lack of accountability, whereby the accountability of the S3i impact investing initiative to the UNOPS executive board was unclear (KPMG 2022b: 14). As such, S3i reportedly acted as a “standalone business unit” (Gridneff 2022).

- Disregard of red flags, whereby oversight bodies did not respond to warnings “in an adequate and timely manner” (KPMG 2022b: 37)

These root causes and vulnerabilities all contributed to the failure of UNOPS to adequately vet SHS Holdings’ ability to deliver on the contracts. For example, UNOPS was inexperienced in impact investing (Gridneff 2022) and its leadership has been reported as having an “aggressive” approach to securing contracts (Ainsworth 2022a). KMPG (2022b) found that “investment decisions of S3i were done without an investment policy framework in place and processes established”, referring to a lack of sufficient oversight and segregation of duty elements between decision-making and audit functions.

The case was also exacerbated by missed opportunities to expose it earlier. Red flags had been highlighted about SHS Holdings during due diligence procedures, but these did not prevent the selection (KPMG 2022b). Furthermore, a whistleblowing complaint on S3i was made in 2019, but was not investigated at the time by UNOPS’ internal oversight mechanism – the Internal Audit and Investigation Group. The IAIG later carried out a self-assessment and concluded it was not fully free from interference in its audit and investigative functions (UNOPS 2023c).

Impact on Stakeholders

The main negative impact of the S3i case was felt by the would-be beneficiaries of its projects living in lower-income countries and in need of affordable housing, renewable energy, and health infrastructure (Lynch 2022). Indeed, part of S3i’s aim was to de-risk7f3b5de800ff and attract private sector investment in such infrastructure projects (Gridneff 2022). Instead, significant risks materialised through the selection of contractors, and the resources not used effectively. In addition, poor management of the funds degraded UNOPS as an organisation. KPMG (2022b) determined the impact investing was partially “done at the expense of investing in the organisation in terms of systems and staff".

Response from Donors and Multilateral Organisations

The S3i case provoked significant donor backlash. The main donor to S3i, Finland, froze all its funding (approximately EUR70 million) to UNOPS, but also other UN agencies, and demanded the independent investigation carried out by KPMG (Mendez 2022). A group of more than 20 donors to UNOPS, including France, Germany, Japan, New Zealand and the United States, called for “full accountability, including individual accountability” during a plenary meeting. Other donors such Denmark (which plays host to the UNOPS headquarters) acknowledged the allegations but did not cut funding towards projects that were “clearly separated from S3i activities “(Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark 2022). Indeed, according to Lynch (2022), some low- and middle-income countries expressed concern over the potential withdrawal of funding to other UNOPS programmes from which they benefited.

KPMG’s forward-looking report (2022a) contained a number of recommendations for UNOPS, including to improve its whistleblower protection system and to introduce financial reforms to ensure excess reserves are accumulated.

UNOPS (2022) welcomed the KPMG reports and committed to implementing most of the recommendations. The Executive Board of UNOPS adopted a 10-point action plan in November 2022, including committing to phase out activities related to the S3i and close its Helsinki office, freeze new investments, and begin working with the United Nations Office of Legal Affairs to recover at least US$2o million in bad debt (Ainsworth 2022a; UNOPS 2023b).

Despite the resignations and contract termination of high-level officials, there is less clarity on measures to ensure the further accountability of UN personnel who may have been complicit in wrongdoing or mismanagement, and whose actions while in office are covered by immunity that can only be waived by the United Nations Secretary General (Lynch 2022). The new director of the IAIG reportedly indicated that he did not think the KPMG report provided sufficient evidence of financial misconduct to merit further legal action against these UNOPS personnel (Lynch 2022).

United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (Case #2)

Facts

The United Nations Stabilisation Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH) was a UN peacekeeping mission established by Security Council resolution 1542 in response to the 2004 Haitian coup d'état (UN Peacekeeping No date b). As with all peacekeeping operations, UN Member States provided, on a voluntary basis, the military and police personnel required (UN Peacekeeping No date a). The number of forces deployed under the mission increased following the 2010 Haitian earthquake, reaching a height of more than 12,500 peacekeepers and police (Johnston 2011). The mission was closed in 2017 and replaced by the smaller United Nations Mission for Justice Support in Haiti (UN Peacekeeping No date b).

Throughout its lifetime MINUSTAH was beset with many controversies. Contaminated peacekeepers were found to have been one of the main causes behind the large-scale outbreak of cholera (Chandler 2015). It also faced corruption allegations; for example, Police Unit officers were accused of extorting money from local, daily-paid workers (Transparency International 2013).

In 2015, investigative journalism undertaken by the Associated Press led to the leak of a draft OIOS report on suspected sexual abuse and exploitation (SEA) (Oakford 2015). Using the term "transactional sexual relationships”, the report outlined how victims, male and female, often received cash, food or other basic goods in return for sexual acts (OIOS 2015b). The power imbalance at work in these cases qualifies them as “sextortion”, which Transparency International (Feigenblatt 2020: 2) defines as a gendered form of corruption in which “those entrusted with power use it to sexually exploit those dependent on that power” and where “the perpetrator demands or accepts a sexual favour in exchange for a benefit that they are empowered to withhold or confer”(Feigenblatt 2020: 8).

The OIOS found evidence of 231 such cases involving local Haitians and MINUSTAH personnel between 2008 and 2013, one-third of which involved children (BBC 2015). The Associated Press investigation highlighted a shocking case in which nine children were exploited by 134 Sri Lankan peacekeepers in a “sex ring” in Haiti from 2004 to 2007 (Dodds 2017).

Triggers and underlying factors

One of the main findings of the OIOS report (2015b) into MINUSTAH was that “transactional sex is hidden and under-reported in missions”. The report relied on interviews with the 231 victims conducted by Kolbe (2015: 18) which found only a few respondents “knew of any policy prohibiting sexual harassment and none knew of a MINUSTAH reporting mechanism or of the MINUSTAH hotline”. Therefore, a general lack of awareness about the prohibition of SEA and the available means to report it may have acted as an underlying factor.

The responsibility of sextortion lies with the perpetrator and their exploitative behaviour. Accordingly, Cavalcante de Barros (2020: 63) argues the complicit peacekeepers “made use of their authority as UN representatives” to commit sextortion. They also relied on a power imbalance and the extreme conditions in Haiti during the period made victims vulnerable to peacekeeping personnel.

Lee and Bartel (2020: 1) interviewed community members in Haiti and found their high level of poverty was an underlying factor to the abuse.

However, the allegations made against MINUSTAH peacekeepers do not form an isolated case. Lee and Bartel point out that since reporting on SEA became more widespread in the 1990s, “almost all UN peace support operations […] have been associated with sexual misconduct to some degree of magnitude and severity” (Lee and Bartel 2020: 2).

Karim and Beardsley (2016: 113) have called the problem "endemic”. Analysing peacekeeping missions active between 2009 and 2013, they found that “higher proportions of both female peacekeepers and personnel from countries with better records of gender equality is associated with lower levels of SEA allegations.” This suggests that divergence in gender norms may act as a significant underlying factor.

Impact on Stakeholders

The main impact of the sextortion carried out by peacekeepers is on the Haitian victims and communities it affected, many of which already live in vulnerable conditions as a result of natural disasters, health crises and political unrest. The victims included extremely vulnerable groups such as orphaned children (Dodds 2017).

According to Feigenblatt (2020: 20) sextortion impacts survivors/victims differently, but it deeply affects many aspects of their lives, including mental and physical health, but also social aspects. For example, Cavalcante de Barros (2020: 42) found that prevailing social norms in Haiti may lead a community to blame women when they are sexually abused, meaning the sextortion by peacekeepers may lead to long-lasting social exclusion.

Furthermore, in the case of Haiti, many women were reported to have had children born as a result of sextortion by peacekeepers (Dodds 2019a). As all peacekeepers left Haiti in 2017, this imposed a significant socio-economic burden on these women.

Lastly, the MINUSTAH case forms part of a wider group of allegations that undermine the credibility of UN peacekeeping forces’ commitment to “do no harm” (UN Peacekeeping 2020).

Response from Donors and Multilateral Organisations

In the peacekeeping context, a distinction should be made between so-called troop contributing countries (TCCs), who second the military and police personnel to missions, and donors who contribute to funding operations more generally. In the same year as the revelations about MINUSTAH emerged, the United States - who was and remains the largest funder of operations (UN Peacekeeping No date b) – cut their funding by up to US$60 million; while representatives did cite the MINUSTAH case in their reasoning, other political factors also appear to have influenced this decision (Keating 2017; Lederer and Dodds 2017).

However, the general focus of the responses to the MINUSTAH cases has been on holding the perpetrators accountable rather than on threatening to withdraw funding. Former Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon said the UN would refuse to process payments to peacekeepers facing credible allegations (Lederer and Dodds 2017). While the UN body responsible for peacekeeping missions – the Department of Peace Operations (DPO) – has to power to carry out preliminary investigations into alleged SEA and to call for the repatriation of peacekeepers to their home countries, it is not able to investigate and prosecute individuals (Elks 2019). As Figure 3 indicates, after the UN has informed TCC of the suspicion of SEA the TCC is only obligated to notify the UN of its investigation, , which is often done through the military justice system (Lee and Bertels 2020).

Figure 3: Selected procedural requirement of the United Nations and TCCs.

|

Event |

United Nations obligation |

TCC obligation |

|

The United Nations has prima facie grounds indicating SEA may have been committed by military personnel |

Inform the TCC 'without delay' |

Notify United Nations within 10 working days if it will conduct its own investigation |

|

TCC decides to investigate |

|

'Immediately inform' the United Nations of the identity of its national investigation officer(s) |

|

Investigation is being conducted by TCC |

|

Notify United Nations of progress 'on a regular basis.' |

|

Investigation is concluded by TCC |

|

Notify United Nations of the findings and outcome of investigation subject to its national laws and regulations |

Source: OIOS (2015b: 14)

This process led to diverging outcomes for the offenders, including impunity for some. For example, in 2012 three Pakistani soldiers guilty of sexually abusing a 14-year-old Haitian boy were repatriated and handed down prison sentences of one year (Kolbe 2015). However, in the case of the 134 Sri Lankan peacekeepers, most of the implicated were repatriated in 2013 but the national government has reportedly since refused to comply with a right to information mechanism and disclose the status of the criminal procedure against them, leading commentators to conclude they have gone unpunished (Cavalcante de Barros 2020: 65).

UNHCR resettlement programmes (Case #3)

Facts

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is an agency mandated to protect and safeguard the rights of refugees. UNHCR (No date) oversees “resettlement”, which it defines as the “voluntary, safe and regulated transfer of people in need of international protection from the country where they are registered (either with UNHCR or with host government authorities) to another country which has agreed to admit them as refugees.” There is no right to resettlement and UNHCR personnel themselves identify persons prioritised for resettlement normally by identifying who is “most at risk of serious harm” in the countries where they are registered (UNHCR No date). Resettlement procedures are administered free of charge (UNHCR No date).

In 2018, journalist Sally Hayden working with The New Humanitarian reported on allegations made by refugees and former staff that certain UNHCR Sudan personnel were soliciting bribes to support refugees with resettlement (Hayden 2019 a). Follow up investigative reporting by Hayden supported by 100Reporters, NBC News, and Journalists for Transparency, and by Jonas Breng for the magazine Stern, uncovered similar allegations made against UNHCR staff in Ethiopia, Kenya, Libya, Uganda and Yemen (Hayden 2019a; Breng 2019).

Their interviewees claimed systematic corrupt abuses of the resettlement procedure were occurring. For example, in Uganda, refugees were reportedly paying up to US$2,500 in bribes to get resettled (Breng 2019). Complicit UNHCR personnel would reportedly falsify information in order to make the case to the third country authorities that the refugees were at risk of serious harm (Breng 2019). This was allegedly done in collusion with third parties such as middlemen and external security services (Hayden 2019 b; Breng 2019). Some refugees reported facing sextortion demands in return for resettlement (Hayden 2019 b). Others who could not afford to pay bribes said their identity documents were stolen to be used for the applications of those who could pay bribes (Hayden 2019 b).

Triggers and underlying factors

There are several potential triggers and underlying factors for corruption of this nature. The countries the allegations concern all play host to large populations of refugees (Hayden 2019). The large numbers, typically remote location of the refugee camps and frequent rotation of international staff can make oversight of all exchanges between personnel and refugees more difficult (Breng 2019). On top of this, resettlement opportunities are scarce, with the UNHCR (2019a) itself acknowledging “the needs for resettlement are far greater than the places available [which] is a factor that weighs heavily in favour of those wishing to exploit desperate refugees”.

Exploiting those seeking resettlement can thus be a source of extra income. The media reporting suggested that local UNHCR staff rather than international staff were usually the ones complicit in the bribery schemes (Breng 2019; Rush 2019). Rush (2019) argues that this may be because they “work in troubled settings and are citizens of countries that face economic setbacks, social turmoil, and corruption issues.” Indeed, UN agencies normally operate different salary scales for national and international staff (United Nations No date).

Both former UNHCR staff and refugees have alleged that the corruption goes beyond individual cases and is systematic (Hayden 2019a). Indeed, there have been similar cases involving UNHCR personnel going back as far as 2001 in Kenya (Hayden 2018a). If both personnel and refugees perceive that bribe-paying in the resettlement process is widespread, this perhaps explains how such corruption could have become normalised.

Impact on Stakeholders

The primary impact of corrupt behaviour was on the refugees themselves who constitute a vulnerable population. It meant that the resettlement processes were not administered fairly and those at most serious risk and in need of resettlement may have lost prioritisation to those who were able to pay a bribe. For example, Hayden (2018c) describes how a victim of sexual violence was unable to pay a bribe that was demanded in order to be prioritised for resettlement.

In Sudan, many affected refugees reportedly said they had given up on the UNHCR resettlement process because of perceived corruption and had rather become more willing to turn to unofficial and more dangerous channels such as contacting smugglers to reach third countries (Hayden 2018a).

Both refugees and former UNHCR personnel claimed they faced forms of retaliation when they reported wrongdoing (Hayden 2018b). For example, three former UNHCR staff members claimed their employment contracts were unexpectedly terminated after they spoke out about fraud (Hayden 2019 b). Some refugees who engaged with UNHCR in their follow-up investigation felt inadequately protected from retribution (Hayden 2019 c). While both groups’ testimonies were crucial to uncovering the allegations, it may also be true that such lack of safeguards discouraged reporting and allowed the corruption to have remained hidden for longer.

Response from Donors and Multilateral Organisations

UNHCR undertook several responses to the allegations. It introduced biometric registration processes in order to prevent identity fraud (Hayden 2019b). In 2018, it temporarily suspended the refugee resettlement programme in Sudan as an internal integrity mission was launched (UNHCR 2019b). Some refugees reportedly felt the temporary suspension was an unfair response as it denied them the opportunity of resettlement (Hayden 2019 b). In August 2019, the suspension was lifted in response to observed successes in implementing the integrity mission’s recommendations (UNHCR 2019b).

UNHCR’s internal investigatory body - the Inspector General's Office (IGO) - launched investigations into the allegations made against officials in Sudan and Uganda (Hayden 2019c; Hayden, S. 2019d). For Sudan, it found one case was substantiated and recommended disciplinary action be taken against the official but found other complaints could not be substantiated due to insufficient evidence (Hayden 2019c). In 2019, the IGO reported on its ongoing investigation into Uganda, stating that most of the allegations appeared “to be mainly based on hearsay” (UNHCR 2019c: 9). The author of this Helpdesk Answer was unable to locate in the public domain any information on the outcome of this investigation.

Many of the former staff and refugees who reported wrongdoing conveyed dissatisfaction with the IGO, expressing doubts about its ability to work independently and asserting that there were more complicit UNHCR staff than the one individual who was penalised (Hayden 2019a; Hayden 2019 c). UNHCR has however denied that corruption and misconduct is endemic to its resettlement programmes. In 2019, it stated it “strongly rejects the widespread allegations against its workforce”, while acknowledging “[a]s with other organisations, we are not immune to risk or failure on the part of individuals” (UNHCR 2019a).

This study did not identify any specific responses of donors to UNHCR to these allegations (see Figure 4 for an overview of leading donors). However, leading UNHCR donors including the UK, EU and US had all reportedly threatened to withdraw financial support in response to a separate corruption scandal from the same period.

In this case, Ugandan government officials were suspected of having inflated refugee numbers and embezzled funds, and UNHCR personnel had allegedly failed to prevent this wrongdoing (Okorir 2018; Hayden 2019e; Titeca 2022). This suggests that some donors may be more sensitive to cases of large-scale corruption involving senior officials than to pettier forms of corruption, even where the latter are endemic.

Figure 4: Leading UNHCR donors.

|

Country |

2019 Financial Requirements (millions) |

Percent Funded as of April 2, 2019 |

Top Five Contributors |

Amount (millions) |

|

Kenya |

$170.1 |

14 % |

United States |

$8.5 |

|

Japan |

$2.5 |

|||

|

Denmark |

$2 |

|||

|

European Union |

$1.5 |

|||

|

Sweden |

$0.8 |

|||

|

Uganda |

$448.8 |

11 % |

United States |

$22.4 |

|

Denmark |

$9.9 |

|||

|

Germany |

$6 |

|||

|

Republic of Korea |

$2.5 |

|||

|

Norway |

$1.2 |

|||

|

Yemen |

$198.6 |

27 % |

United States |

$10.0 |

|

United Kingdom |

$4.5 |

|||

|

Japan |

$3.6 |

|||

|

European Union |

$3.4 |

|||

|

Sweden |

$1.6 |

|||

|

Ethiopia |

$346.5 |

13 % |

United States |

$17.3 |

|

United Kingdom |

$6.9 |

|||

|

Denmark |

$4.9 |

|||

|

IKEA Foundation |

$2.3 |

|||

|

Japan |

$2 |

|||

|

Libya |

$85.0 |

58 % |

European Union |

$12.6 |

|

United States |

$6 |

|||

|

Germany |

$5.9 |

|||

|

Italy |

$2.6 |

|||

|

Netherlands |

$2 |

Source: Rush (2019:5)

World Bank/International Finance Corporation in Guatemala (Case #4)

Facts

The International Finance Corporation (IFC) acts as “the private sector arm of the World Bank Group and shares its mission to reduce global poverty” (World Bank No date). It offers investment services to private sector actors working in developing countries.

In the early 2010s, the IFC in coordination with national and local authorities initiated an investment opportunity in which a 25-year usufruct8c72b47387ac was to be offered for a port in the Guatemalan city of Puerto Quetzal (Lohmuller 2016). In 2012, the Government of Guatemala awarded the contract to the Spanish corporation Grup Maritim TCB, which in turn created the subsidiary Terminal de Contenedores Quetzal (TCQ) to develop and manage a container terminal at the port (Lohmuller 2016).

The IFC provided a loan to TCQ and took an equity stake totalling US$44.7 million (see Figure 5). It also provided support to raise the debt financing needed to complete the project’s total financing plan of US$177 million (IFC No date).

Figure 5: IFC’s Investment as approved by the Board.

|

Product Line |

IFC Investment (million USD) |

|

Risk Management |

|

|

Guarantee |

|

|

Loan |

35 |

|

Equity |

9,7 |

|

Sum |

44.7 million (USD) |

These investment figures are indicative. Source: IFC (no date).

In 2016, an investigation carried out by the International Commission against Impunity in Guatemala (CICIG) in cooperation with the Attorney General’s Office of the Guatemala identified a network of 18 actors including five who are based outside of Guatemala, suspected of taking part in a scheme to pay up to US$12 million in bribes to secure the port contract (Lohmuller 2016; Freight Waves 2016). The bribes were allegedly given by TCQ and Grup Maritim TCB and then were transformed into kickbacks for Guatemalan political figures, most notably Otto Pérez Molina and Roxana Baldetti, the then President and Vice President of Guatemala respectively (El Economista 2016). Both were alleged to have “appointed several collaborators to top positions within a state company” that managed the port to receive these bribes from TCQ and facilitate these kickbacks (Lohmuller 2016).

These allegations triggered a wave of legal actions. The usufruct over the port was annulled (Freight Wave 2016). APM Terminals - a port-operating subsidiary company of shipping giant Maersk – acquired Grup Maritim TCB in 2016 and in the same year paid what was termed as a "civil reparation" of US$42.3mn to State of Guatemala to settle the corruption charges. In return, APM Terminals received a concession to use the now completed TCQ terminal (El Economista 2016).

Criminal prosecution processes were initiated in both Spain and Guatemala. The former TCQ director received an eight-year prison sentence in 2018 (Oliva 2021; España 2022). A June 2021 report by Spanish paper El Confidential alleged to have uncovered emails implicating Pérez Molina and Baldetti in the bribery scheme (Oliva 2021); in September 2023, an eight-year prison sentence was handed down to Pérez Molina by a Guatemalan court (Delcid 2023).

Triggers and underlying factors

At a basic level, the trigger for this case was a foreign company resorting to corrupt measures and get favourable treatment from local powerholders to secure a profitable contract. Therefore, the case brings together typical elements of foreign bribery and political corruption.

There is no evidence the IFC played an active role in the scheme. Nevertheless, it played a central role in approving the project and providing a loan to Grup Maritim TCB, for which it was required to carry out due diligence on third parties involved.

No Ficcion (2018) published an article accusing IFC of ignoring red flags raised during this process. Specifically, they claim that the CSOs Acción Ciudadana and USAID’s Transparency Project had flagged potential corruption risks and that the proper public tender process was not followed during the awarding process. The IFC denied both of these claims in a public statement and stated they were surprised when the reports of corruption emerged as the Guatemalan people were (Humberto López 2016). According to IFC (No date) Grup Marítim TCB was “Spain’s leading port terminal operator specialising in containerised cargo” and had not been considered a risk. Another senior IFC official said the organisation would review how the due diligence procedure was conducted based on “the information available at the time” (IFC 2016); the author of this Helpdesk Answer could not locate in the public domain the outcome of any such review.

Impact on Stakeholders

The main impact of the case was on the Guatemalan people who were supposed to be the beneficiaries of the TCQ project. Indeed, the IFC invested in the project in line with its stated aim of poverty relief; according to the World Bank (2023) itself, around 55% percent of Guatemalans live below the poverty line. The bribery led to wasted resources and the investigation led to a temporary moratorium being imposed on the constructed port (No Ficcion 2018. Furthermore, it can be assumed that competing firms bidding in good faith for the port contract unfairly lost out.

The case also had a strong national impact. It was one of several corruption allegations that contributed to the political downfall and eventual arrest of Pérez Molina; it also led to greater scrutiny of the Guatemalan justice sector after a magistrate was implicated in the case (Tabory 2016). It triggered the arrest of prominent businesspeople in Spain and Guatemala (Van Marle 2019). It also seems to have engendered further instances of corruption; for example, there are allegations one of the Spanish businessmen enlisted corrupt actors to avoid being extradited to Guatemala (Requeijo 2021).

Response from Donors and Multilateral Organisations

The author of this Helpdesk Answer was unable to locate in the public domain any responses from IFC donors or partners. The main responses to this case were driven by Spanish and Guatemalan criminal justice actors. It should be noted that the original detection of the case was driven by CICIG which was a body created by the United Nations and funded by the G13 donor group as well as multilateral organisations such as the World Bank (Guerrero 2021).

After the allegations were revealed, the IFC referred the case to the World Bank’s Integrity Vice Presidency for investigation (Humberto López 2016). The author was unable to determine whether the outcome of this investigation was ever made public.

Reflections

Good practice in research design is to avoid generalising from a small set of case studies or at least be cautious when doing so (Research Design Review 2020). Indeed, these four cases comprise a very small subset of suspected corruption cases involving multilateral organisations in light of the aggregate statistics they publish annually.

With this caveat in mind, a short comparative reflection of the four cases discussed above helps to identify some differences and similarities. The cases which best illustrate these points are highlighted in parentheses with their corresponding numbers i.e. Case #1, Case #2, Case #3, Case #4.

The facts of the cases are largely heterogenous due to the different kinds of multilateral organisations featured. Thus, the manifestation of corruption or misconduct to a certain extent reflects the mandate and structure of the multilateral organisation. The corruption risks for organisations carrying out in-field humanitarian operations (Case #2, Case #3) may be of a different nature than those working primarily off-field to plan and fund development interventions (Case #1, Case #4); for example, the average value of the individual bribes in the UNHCR case was far less than in the IFC case. Accordingly, corruption risks appear at both the lower and higher end of the hierarchy of multilateral organisations, at both headquarters and remote field locations, as well as different stages of the project life cycle, from design to implementation.

Investigative journalism played an important role in uncovering the facts of all four cases. This was achieved by interviewing victims (Case #3) or through leaks of investigation documents (Case #2).

In terms of identified triggers and underlying factors, corruption risks may stem from multilateral organisations working with unreliable third parties – be they private sector actors (Case #1, Case #4) or national governments (Case #4). Corruption risks may also be sourced from internal personnel, including those based in remote locations where supervision can be challenging (Case #2, Case #3). The availability of large financial resources may be accompanied by institutional pressure to expend them, leading to risk-prone decision-making (Case #1) and insufficient due diligence processes. In other cases, the effective impunity actors enjoyed enabled corrupt behaviour (Case #2). Another similar underlying factor was that early warnings either did not surface or were not heeded. All organisations featured in the cases had reporting mechanisms, but there was either a lack of awareness among victims of corruption (Case #2) or reports were ignored (Case #1, Case #3).

All cases demonstrate the severe impact on stakeholders that corruption in multilateral organisations can have. This can take the form of squandered donor resources not being used to benefit the targets of projects (Case #1, Case #4), but it can also take the form of more lasting and damaging impact on vulnerable populations (Case #2, Case #3). These impacts highlight the significance of multilateral organisation’s responsibility to manage corruption risks.

The responses of donors were heterogenous across cases. The response can be considerable and coordinated (Case #1), but in other cases more muted (Case #3, Case #4). Donors or TCCs may also obstruct a full remedial response to instances of corruption (Case #2). However, it should be reiterated that further information on donor responses is likely to be available outside the public domain, in the internal files of donors themselves.

The response of multilateral organisation were also heterogenous, which may be influenced by the magnitude of the media and donor attention (especially where there is coordination among donors) a given case receives. In all cases, the multilateral organisations did introduce measures or initiate investigations after allegations were featured in media reports.

In three cases (Case #2, Case #3, Case #4), the first response was to rely on internal investigations, often supplemented by institutional external oversight investigations such as the OIOS; in only one case (Case #1) was a truly external actor brought in. In all cases, accountability processes were opaque and possibly inadequate to truly hold perpetrators of corruption to account. On a related point, there appeared to be a common reluctance on the part of multilateral organisations to publish detailed outcomes of internal investigations. Finally, multilateral organisations remain important stakeholder in the fight against corruption; for example, CICIG (Case #4) which was established and supported by the UN and donors illustrate how such organisations can also proactively contribute to anti-corruption efforts.

- Organisations are considered to be multilateral when they have been “formed by three or more nations to work on issues of common interest” (Rydén, No date).They may also be referred to as “intergovernmental organisations”. Many multilateral organisations, but not all, have the status of international organisations, meaning they are organisations “established by a treaty or other instrument governed by international law and possessing its own international legal personality” (International Law Commission 2011).

- For a more detailed overview of multilateral organisations’ integrity measures, see previous Helpdesk answers (Rahman 2022; Jenkins 2016).

- The Law Insider (No date)defines de-risking as “mitigating the risks of doing business in high-risk environments through concessionary finance or investment guarantees”. It aims to avail of "risk-free capital”, including private sector markets, to facilitate projects that might otherwise be considered too risky.

- A usufruct is defined as the “right to use and benefit from a property, while the ownership of which belongs to another person” (Legal Information Institute 2021). Depending on the agreement, some of these uses might be exclusively granted.