Query

Please provide an overview of how anti-corruption contributes to democracy promotion and protection, particularly in the following overarching democratic principles: a) division of powers, b) political competition, c) democratic culture, d) political participation. What are the risks of anti-corruption campaigns undermining democracy and are there any possible ways to address these risks?

Caveat

This paper serves to illustrate, with a few non-exhaustive examples, how anti-corruption contributes to democracy promotion. It does not provide recommendations on effective anti-corruption measures to implement to enhance democracy.

Background: Understanding the relationship between corruption and democracy

In much of the literature on good governance, corruption is understood as a driver of democratic decline, lowering public trust in government, prejudicing sound policymaking to favour private interests, as well as leading to the capture of accountability mechanisms and nominally independent oversight agencies (see Transparency International 2021: 3; Venard 2019; Kolstad and Wiig 2011). Indeed, the first paragraph of the preamble of the United Nations Convention against Corruption (UNCAC) recognises corruption as undermining “the institutions and values of democracy, ethical values and justice” as well as “jeopardising sustainable development and the rule of law”.

Corruption often involves the illicit extraction of public resources, which can enable leaders and patronage networks to strengthen their grip on power. For instance, corrupt actors may buy political allegiance from voters, the loyalty of the civil service and independent institutions, as well as to co-opt political opponents and activists (Jackson and Amundsen 2022: 1).

Political corruption works by extraction and reinvestment. Extraction includes bribery, embezzlement or extortion, while reinvestment involves using these funds to buy favours from courts, opposition politicians or electoral commissions (Jackson and Amundsen 2022: 3-4). The ability to both extract and reinvest relies on what is sometimes labelled informal policy spaces – in other words, policy processes that are not governed by official procedures or overseen by official institutions but by networks. The power to extract public resources directly translates into political power for corrupt and despotic leaders (Jackson and Amundsen 2022: 6).

In addition, corruption erodes state institutions and public accountability mechanisms, as well as undermining the separation of powers crucial for providing checks and balances in a democratic setting (Stöber 2020: 11). As highly corrupt regimes consolidate their grip on power, this is often accompanied by restrictions on political rights to stifle opposition or criticism (including of rampant corruption), which makes it even more difficult for citizens to effectively participate in public decision-making and to hold duty bearers to account (Lifuka 2022; Warren 2004). Citizens could also lose trust in institutions, leading to disenchantment with politics.

Studies have also documented that higher rates of corruption decrease the turnout during elections (Stockemer et al. 2013; Kostadinova 2009). For instance, Stockemer et al. (2013) assessed the effect of corruption scandals on voter turnout in a number of different democracies and found that high rates of corruption had a direct causal effect on lower voter turnout during elections.

As democracy is deeply reliant on public trust, a lack of political integrity tends to lower public trust and thereby weaken democracy (Rose-Ackerman 2004; Seligson 2005; Venard 2019). Studies have indeed demonstrated that there is an almost linear relationship between the perception of corruption in a country and the level of dissatisfaction with democracy in that country (Keulder and Mattes 2021).

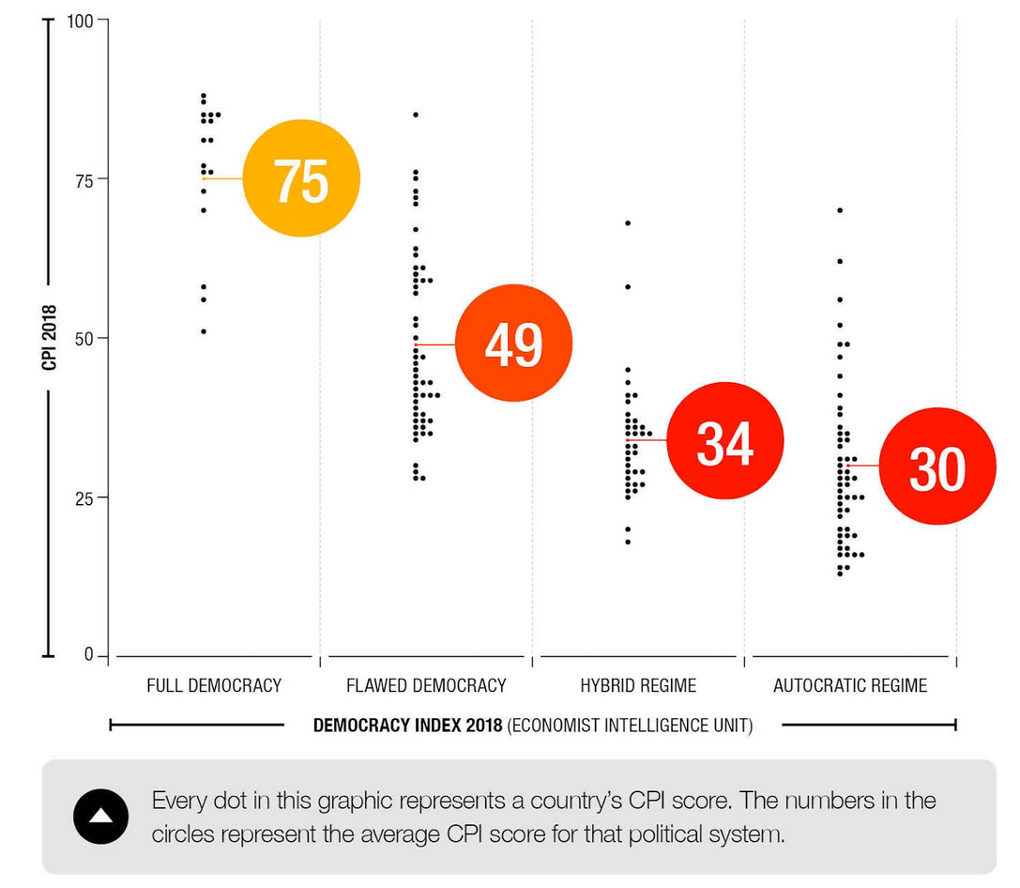

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index 2018 also showed “a disturbing link between corruption and the health of democracies, where countries with higher rates of corruption also have weaker democratic institutions and political rights”. It revealed that the continued failure by most countries to significantly control corruption was a contributing factor to the crisis in democracy worldwide (Transparency International 2019).

As pointed out in the report, “corruption chips away at democracy to produce a vicious cycle, where corruption undermines democratic institutions and, in turn, weak institutions are less able to control corruption” (Transparency International 2019).

Similar analysis on the relationship between corruption and democracy can be found in a growing number of prominent policy documents. For instance, the 2021 US Strategy on Countering Corruption, explicitly states that corruption is an existential threat to democracy. Addressing corruption also features in global targets to pursue democratic and sustainable societies, such as the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goal 16.

However, upon deeper inspection, the relationship between corruption and democracy is complex. Although advanced democracies enjoy low levels of corruption, flawed democracies and democratising regimes may experience rising levels of corruption (McMann et al. 2017: 4, 6; Drapalova 2019: 5). In fact, in some cases, an increase in civil liberties, such as freedom of expression and freedom of association, may be associated with a rise in perceived corruption (McMann et al. 2017). One reason for this is that more freedom of expression and association may lead to new ways of exposing corruption. (McMann et al. 2017; Drapalova 2019: 5).

As Pring and Vrushi explain (2019), “countries which recently transitioned to democratic governance often did not develop effective anti-corruption and integrity mechanisms, and now find themselves stuck in a cycle of high corruption and low-performing democratic institutions”. Hence, it may be important to keep in mind how corruption, or even just its perception, may also be on the increase as countries start to strengthen democratic processes (UNODC no date).

Another example of the complex relationship between corruption and democracy is the fact that some authoritarian regimes enjoy relatively lower levels of corruption compared to some democracies (see Drapalova 2019: 2). However, these regimes are outliers (see Figure 1), and corruption remains a huge challenge in most autocratic countries (see Kukutschka 2018; Camacho 2021).

Figure 1: CPI scores grouped by regime type

(Pring and Vrushi 2019).

Contribution of anti-corruption measures to democracy

Generally, anti-corruption391e9cd6c032 measures aim to enhance integrity, transparency, participation, accountability and justice – which all contribute to a more democratic environment. This section describes how anti-corruption can contribute to democratic consolidation. It considers the potential contribution of anti-corruption efforts to the following four central principles of democracy:

- separation of powers

- political competition

- democratic culture

- political participation

A few non-exhaustive examples are provided without comment on the effectiveness of the interventions mentioned.

Anti-corruption and the separation of powers

The effective separation of powers is not just a hallmark of a well-functioning democracy, but also critical to effectively control corruption (Drapalova 2019: 4). As part of the division of powers, the system of checks and balances between branches of government is supposed to ensure that office bearers and politicians are held to account. The separation of powers is also intended to prevent and penalise abuse of entrusted power by any branch of government.

Note that there are also other non-state actors in the accountability ecosystem, such as civil society groups and independent media (Halloran 2021), which are sometimes referred to as the “fourth estate” (Gill 2020). While these actors can play an important role in holding power to account, they are not part of the formal system of checks and balances and so are covered in a later section on democratic culture.

Below are some examples of potential programmatic responses with regards to how anti-corruption measures can contribute to the democratic principle of separation of power.

Anti-corruption reforms in the judiciary

The judiciary is one of the most important institutions for curbing corruption, upholding the rule of law and maintaining the separation of power. Support to judicial reforms is widely considered one of the primary programmatic responses in the field of both anti-corruption and democracy promotion (Jennet 2014: 4). These reforms may be aimed at enhancing the integrity, independence and effectiveness of the judiciary.

Among the anti-corruption measures designed to strengthen integrity within the judiciary are (Jennet 2014; Schütte, Jennett and Jahn 2016):

- the establishment of a code of conduct

- access to information regimes

- electronic systems for case allocation to minimise manipulation

- court monitoring programmes that provide oversight over courts (including where these courts deal with corruption cases)

- complaints mechanisms

Such integrity measures help to promote a culture of excellence and independence in the judiciary (Matos 2017), and reinforce the separation of powers.

Some anti-corruption measures specifically aimed at strengthening the independence of judges cover issues such as transparency and due process in the appointment of judges, minimising political influence on judges’ tenure and conditions, as well as eliminating undue influence on human and financial resources in the judiciary (Gloppen 2014). These measures enable the judiciary to act without fear or favour, including when holding the executive and parliament to account.

Some donor programmes have focused on anti-corruption reforms in the judiciary.dcd8b27ac053 For example, the World Bank’s Romania Judicial Reform Project aimed to increase the efficiency of the Romanian courts and improve the accountability of the judiciary. From the independent review of the project, some of the achievements noted were improvements in accountability of judicial officers through revised codes as well as improved human and financial resource management systems (World Bank Independent Evaluation Group 2018).

The key issue in anti-corruption reforms in the judiciary involves balancing the need for judges to act independently and the need to have oversight mechanisms that hold judges to account (Jennett 2014: 4). If efforts to address corruption come at the expense of judicial independence, it may adversely affect levels of democracy as it could enable other branches of government to interfere. For example, where the executive is given excessive powers to institute disciplinary actions against judges, this may result in the abuse of such powers to target judges. However, at the same time, corrupt actors in the judiciary should also be held in check by strong oversight and sanctioning mechanisms (Jennet 2014: 4).

Attempts at judicial reform in Moldova offer valuable and cautionary lessons for the international community with regards to the design of anti-corruption reforms in the judiciary that ensure genuine democratic transformation. Some senior judges in the country – who were allegedly beneficiaries of the former kleptocratic leadership – have reportedly opposed the reform agenda advanced by the Party of Action and Solidarity under President Maia Sandu, who won an election in 2020 on an anti-corruption platform (Minzarari 2022:5).

The justice system is not under the control of the executive branch, but is still highly politicised and protects the interests of the former kleptocrat (Minzarari 2022: 3). An important lesson learned from reforms in Moldova has been that, rather than focusing just on judicial independence, donors should focus on strengthening impartiality (Minzarari 2022: 8).

Judicial reforms in emerging and transitional democracies have also focused on creating special anti-corruption courts. A number of lessons can be drawn from the process of setting up the High Anti-Corruption Court (HACC) in Ukraine (Vaughn and Nikolaieva 2021).

Before the Russian invasion in February 2022, HACC faced serious challenges. It had low levels of citizen trust as some of its rulings had been overturned by the constitutional court and pending cases at the constitutional court challenged the constitutionality of the HACC itself (Vaughn and Nikolaieva 2021: 36).

Despite these challenges, the launch of the HACC may hold valuable lessons for actors seeking to implement similar actions in other contexts. In particular, there was widespread support among various stakeholders, including the international community, donors and local civil society – which enabled its establishment and support afterwards (see Vaughn and Nikolaieva 2021: 37).

Transparent and accountable parliaments

The transparency and accountability of parliaments are key factors in building public trust in the institution. As parliament is the “house of the people” responsible for shaping policies and laws as well as holding the executive to account on behalf of the people, it is essential that citizens can follow the activities of parliamentarians and understand what is transpiring in parliament (Prasojo 2009: 9-10).

As pointed by Prasojo (2009: 10), “only through transparency and accountability can the parliament, as one of the institutional pillars of democratic governance, ensure that the operations of the state and the government are responsive and accountable to the people’s needs and expectations”.

A guide by the Inter-Parliamentary Union, Parliament and Democracy in the Twenty-First Century: A Guide to Good Practice, points out that transparency and accountability are some of the key characteristics for a democratic parliament, in addition to being representative, accessible and effective.

Transparency in parliament entails the following:

- disclosure of information on parliament’s tasks and responsibilities, including the openness of its sessions, proceedings, drafting of bills, debates, lobbying of members of parliament, as well as its findings and decisions

- availability of mechanisms to ensure the public can access relevant information

- legal mechanisms to ensure the implementation of citizens’ rights to obtain such information (see Prasojo 2017: 15)

Access to information is a first step to enabling citizens to become more involved and exercise influence over the activities of parliament (Beetham 2006: 69). Hence, in addition to transparency, the participation of citizens in parliamentary processes and decision-making also increases public trust in the institution as their representatives (Prasojo 2017: 15).

On accountability, parliamentarian is regularly regarded as one of the most corrupt professions, according to Transparency International’s Global Corruption Barometer.

Table 1

|

Region |

Percentage of GCB respondents who believe most or all members of parliament are corrupt |

|

Europe (Transparency International 2021b: 14) |

28% |

|

Sub-Saharan Africa (Transparency International 2019b: 12) |

36% |

|

Latin America (Transparency International 2019c: 14) |

52% |

|

Middle East and North Africa (Transparency International 2019d: 12) |

44% |

|

Pacific (Transparency International 2021b: 21) |

36% |

|

Asia (Transparency International 2020: 14) |

32% |

To effectively leverage the legislature’s potential to control corruption and provide democratic checks on other branches of government, the legislature needs to be more accountable by establishing and adhering to its own integrity mechanisms (Chêne 2017: 6).

Some of these controls include parliamentary codes of conduct, conflict of interest policies, as well as assets and income declarations.3f70f3a0b90a All of these have the common objective of ensuring that public officials act in the interest of the public rather than their own private interests (France 2022; Harutyunyan 2021: 24). They aim to improve parliament’s actions and standing before voters. These are also included in the international anti-corruption frameworks, such as article 8 of UNCAC, which requires measures that regulate declarations of assets and income, assets and substantial gifts or benefits from which a conflict of interest may arise.

As pointed out by the Commonwealth Parliamentary Association (2016:1), good conduct by parliamentarians is “crucial because it builds trust – when there are trusting relationships between the people, parliament and other institutions, democracy works at its best… When people trust that their elected representatives are acting in their best interests, this helps legitimise our parliaments and our democratic systems”.

Other measures aimed at enhancing the integrity and independence of parliaments include the regulation of lobbying. Lobbying is defined as “any activity carried out to influence a government or institution’s policies and decisions in favour of a specific cause or outcome”.9b3201f0fb38 It can facilitate accountability and opportunities for interest groups to contribute to policies and laws, such as for climate change (see Nest and Mullard 2021). Yet, lobbying can also verge on corruption where – in exchange for certain favours – financially and politically powerful individuals enjoy privileged access to parliamentarians and these MPs defend narrow private interests over the public interest (see Nownes 2017).

There are various international standards regulating lobbying. The OECD Principles for Transparency and Integrity in Lobbying, for instance, establishes measures to enhance transparency, mechanisms for implementation and compliance (such as codes of conduct, sanctions) and measures to foster a culture of integrity. As emphasised in its 2021 report, regulation of lobbying “enables those who influence policies not to be systematically stigmatised as being corrupt” – thereby building trust between citizens and parliaments (OECD 2021: 126).

Anti-corruption and political competition

Corruption in politics and elections – such as electoral fraud, vote buying and capture of parties and candidates by private actors – undermines political processes and outcomes as well as public trust in democracy.

This form of corruption distorts the kind of fair competition between political parties and candidates vying for public office that is crucial for the functioning of democracy. Autocratic governments can use elections as a way to legitimise their stay in power and to avert internal and external pressure, and can turn to both intimidation and corruption to rig the outcome (Mostafa and Bhuiyan 2012: 185).

As such, countering corruption through enhancing transparency and integrity in political financing and elections can play a significant role in protecting and promoting the democratic principle of political participation, as set out below.

Transparency in political financing

Efforts to increase transparency in political financing is an anti-corruption measure that supports the democratic principle of political competition (International IDEA and OGP 2019: 1).

This is because transparency in political finance:

- Levels the political and electoral playing field. As political finance transparency usually includes controls on campaign spending by establishing caps, the spending gap between candidates and political parties is contained, thereby increasing political competition (International IDEA and OGP 2019: 1). In addition, the provision of public funding encourages political competition by promoting equal chances among competing political parties (OECD 2016: 22). Parties and candidates receiving public funds are expected to run their political and election campaigns with greater integrity when receiving money with no strings attached than when these political parties are financially dependent on big businesses, corporations and lobby groups (Mostafa and Bhuiyan 2012: 190).

- Keeps politics and elections clean from illicit and criminal money that erodes institutions, processes and outcomes of democratic governance. In particular, transparency in political finance can help ensure that only clean money is used to fund political parties and elections, thereby encouraging and promoting clean political competition.

- Prevents capture of political parties and candidates through restrictions and limits on private contributors and requiring publication of their contributions. As funding is an important component in democratic processes and may be a key factor in a party’s electoral fortunes, an absence of restrictions will likely favour candidates and parties who receive the most contributions, and may be indebted to funders and donors who expect reciprocity from the newly elected officials.

- Promotes the political participation of women and other marginalised groups. According to International IDEA and OGP (2019: 3), female candidates face considerable barriers when running for political office due to a lack of access to campaign finance. Studies indicate that the political gender gap is still wide (Skaaning and Jiménez 2017: 21; WEF 2017: vii). Likewise, minority and Indigenous groups face similar hurdles (IPU and UNDP 2010: 16–17). Hence, political finance reforms that promote political participation and representation of women and marginalised groups in political offices can also help improve democratic competition and representation (International IDEA and OGP 2019: 3).

As such, transparency in the funding of campaigns and political parties is at the centre of the international anti-corruption agenda (International IDEA and OGP 2019: 1). For instance, article 7(3) of the UNCAC considers it paramount for member states to enhance transparency in the funding of elections and political parties. Article 10 of the African Union Convention of Preventing and Combating Corruption also requires countries to prohibit the use of illicit funds to finance political parties and embed the principle of transparency into the funding of political parties.

Some development projects have focused on enhancing transparency in political finance. For instance, International IDEA has been implementing the project Level Up: Political Finance with Integrity in Mongolia, Moldova and Paraguay in partnership with local institutions to facilitate inter- and multi-stakeholder dialogues aimed at improving political financing frameworks that empower women and young people to actively participate in politics.

Transparency and integrity in elections

Free and fair elections are the cornerstone of democracy and the most direct mechanism for citizens to express their political preferences by choosing their representatives and government (Bosso, Martini and Ardigó 2014: 6). Fairness and competition in elections is threatened by vote buying, abuse of office and election rigging (Uberti and Jackson 2018: 6).

Vote buying involves giving out material things such as cash or food to citizens in exchange for votes. Election rigging entails the manipulation of electoral outcomes through corrupt practices including ballot stuffing, mis-recording of votes to favour a certain candidate, manipulation of the voter register or demographic information to influence elections (Bosso, Martini and Ardigó 2014: 17).

Abuse of office involves a person using their official position and related powers and privileges to advance the electoral interests of a particular candidate or party. Such forms of corruption in elections have a negative impact on democracy, as they give an advantage to undeserving leaders and frustrate genuine political competition. According to the ACE Electoral Knowledge Network, “without electoral integrity, leaders and officials lack accountability to the public, confidence in the election results is weak, and the government lacks necessary legitimacy.”

Anti-corruption measures to ensure integrity in politics can play an important role in promoting and protecting democracy. This includes the following:

- prohibition of vote buying contributes to a level political playing field and a fair democratic process and outcome

- prohibition of the use of state resources for the purposes of election campaigning, other than those disbursed in terms of the electoral law (Bosso, Martini and Ardigó 2014; Jenkins 2017)

- the independence of election administrative staff ensures that any conflicts of interest are prevented and addressed (DeGregorio and Ambrogi 2016), and that all parties to elections are treated fairly in accordance with the law

- transparency in electoral processes, such as the ballot design or the procuring of services provides candidates and voters with information on how an electoral office conducts its business (DeGregorio and Ambrogi 2016), which boosts public trust in the democratic processes

International Foundation for Electoral Systems (IFES) has been implementing projects to enhance transparency and integrity in elections. For example, in 2020, it launched the Improving Electoral and Political Process for Change in Sudan (IEPP-Sudan), a project to establish and strengthen democratic institutions, stakeholders and processes to deliver transitional elections. It focuses on:

- supporting the electoral management body (EMB), once established, with its organisational capacity to administer credible elections

- enhancing transparency and accountability in electoral processes to strengthen the public’s understanding of and confidence in elections

- increasing the participation and empowerment of marginalised people in electoral processes, with special consideration for youth, women, people with disabilities, internally displaced people, refugees and people in geographically remote areas

- advising the transitional government on implementing international standards of impartiality, inclusivity and accessibility into the legal framework and regulatory reforms for elections, referendums and the EMB

In Armenia, IFES is also currently implementing the USAID-funded Strengthening Electoral Processes and Political Accountability (SEPPA) to promote the integrity of elections through electoral reforms, enhance professional development of the central election commission and capacity building to effectively oversee elections, as well as encourage citizen engagement in elections and political processes.

The European Commission project Support to the Nigerian Electoral Cycle 2012-2015 aimed to promote credible, transparent and sustainable electoral processes; improve the democratic quality of political engagement; enhance participation by women, youth and other marginalised groups; and strengthen channels for civic engagement.

According to the evaluation report, rather than supporting a one-off electoral event, it is important to build and support participation and understanding of the whole electoral cycle to “engender a democratic political culture” (Gómez and Jockers 2014: 27).

Some of the achievements from the project included improving political competition and the participation of women through successfully advocating for different stakeholders to promote affirmative action for women, including within the electoral management board, political parties and women’s organisations. In addition, it also resulted in the enhanced education and capacity of civil society, relevant private institutions and members of the public on freedom of information related to political parties and elections (Gómez and Jockers 2014).

Though donor support programmes are instrumental in enhancing transparency and accountability in electoral processes, Uberti and Jackson (2016) caution that the gains may sometimes be small and short-lived in some countries. They recommended that donors consider providing electoral assistance programmes to low-income countries and societies that are not receiving election support programmes. However, decisions on aid allocation should be based on in-depth analysis of context specific factors, such as political climate and social norms around elections, which may frustrate election related development assistance programmes.

According to the study, certain types of electoral misconduct, such as ballot stuffing, flawed vote-counting or other technical irregularities on polling day, are less likely to be addressed through election support aid. Hence, practitioners are advised to conduct a comprehensive analysis within a given setting of which kind of corrupt practices may be addressed through reform (Uberti and Jackson 2016).

Anti-corruption and political participation

Democratic consolidation entails more than establishing basic institutions and mechanisms for democratic rule, such as free and fair elections, an independent judiciary and a powerful parliament. Beyond elections, it also requires mechanisms that connect the state to its citizens to nurture public trust and legitimacy (UNDP 2012: 14; OECD 2022) and that ensure the participation of citizens in decision-making processes.

Public participation is a key driver of democratic and socio-economic change (National Democratic Institute, no date). As stated by Adserà, Boix and Payne (2003: 445), “how well any government functions hinges on how good citizens are at making their politicians accountable for their actions”.

Anti-corruption plays an important role in enhancing public participation through citizen led initiatives. Public participation in anti-corruption efforts is often “understood in terms of social accountability, where the citizens oppose corruption by keeping it in check, critically assessing the conduct and decisions of office holders, reporting corruption misdoings and crimes, and asking for appropriate countermeasures” (UNODC, no date: 12).

Social accountability refers to a wide range of actions and mechanisms that citizens use to demand accountability from office, including efforts by civil society organisations and media outlets to support citizens’ demands for accountability (UNDP 2010:10). It involves activities such as citizen monitoring of government performance, access to information, public complaints and grievance redress mechanisms, and citizen participation in decision-making such as the allocation of state resources such as participatory budgeting (F0x 2015: 346).

Such social accountability tools are also recognised in the international anti-corruption framework. For instance, article 13 of UNCAC provides for the promotion of public participation in anti-corruption, including contribution to decision-making processes, access to information, public information and education activities on anti-corruption, as well as respecting, promoting and protecting the freedom to seek, receive, publish and disseminate information concerning corruption.

Social accountability, as an anti-corruption approach, can strengthen links between governments and citizens, with citizens effectively contributing to:

- improvements in public service delivery

- monitoring of government performance and fostering responsive governance

- greater emphasis on the needs of marginalised groups in the formulation and implementation of government policies, including enhanced empowerment of marginalised groups excluded from policy processes and decision-making (UNDP 2010: 11)

- the exposure of government failures and pressure for redress

According to Jonathan Fox, to the extent that social accountability fosters citizen power against the state, it is a political process distinct from the political accountability of officials through elections. As such, “this distinction makes social accountability an especially relevant approach for societies in which representative government is weak, unresponsive, or non-existent” (Fox 2015: 346).

A few and non-exhaustive examples of social accountability tools, mainly at local government level, are provided below.

Participatory planning

Participatory planning involves mechanisms for citizen participation in policy and decision-making processes. For instance, participatory budgeting involves citizens in setting and executing budgets. This tool can also be combined with social audits as explained below (Ardigó 2019: 15).

Available evidence from studies in middle and lower-middle-income countries in South and Central America tends to find mixed to positive effects from interventions to implement participatory policy approaches (Campbell et al 2018). One potential explanation is the risk that participatory planning and budgeting is not always as participatory in practice as on paper. Indeed, some participatory policy processes tend to have a positive effect on spending on public services (Campbell et al 2018: 7-9), but some also find no positive effect and one study actually shows participatory budgeting can hurt low-income groups as social services become directed more towards those groups most involved in the process (Campbell et al. 2018: 9). Hence as covered in the final section of this paper, it is important to consider the do no harm principle when implementing such programmes.

One positive case of participatory policy processes is presented in Madhovi’s (2020) study of the impact of a participatory budgeting project in Zimbabwe. In this project, participatory budgeting was used as a way to address a series of fiscal issues, including petty tax evasion and difficulties in budget execution (Madhovi 2020: 141). In the intervention, a number of broad budget consultations were held with various stakeholders, from churches, business associations, youth and women’s associations. During the consultations, participants received information on the draft budget and were provided the opportunity to review and provide input (Madhovi 2020: 151). According to Madhovia (2020), this process was received positively by a slight majority of participants and led to a significant growth in tax revenue in the years after (as people allegedly cheated less on their taxes) (Madhovi 2020: 153). Nevertheless, local ownership still had some way to go.

Summing up, lessons learned from participatory processes show that they can be effective ways to: i) allow a broad range of stakeholders to participate in democratic political processes beyond the ballot box; and ii) improve service provision. However, if such approaches are to be effective, interventions focused on participation need to manage risks such as policy consultations being empty of actual content or a lack of meaningful representation for more marginalised communities (Khadka and Bhattarai 2012: 87; Ringold et al. 2012: 54).

Social audits

Another social accountability tool that has potential to leverage the synergy between anti-corruption and local democratic participation is the use of social audits. A social audit is an assessment focusing on social criteria carried out in collaboration by affected stakeholders (such as community organisations, citizens groups and government officials). This will theoretically create some oversight of those subject to the audit by communities (Ringold et al 2012: 54). The auditors are supposed to assess what has been delivered, and how this conforms with the needs of the communities in question.

Social audits have been carried out by anti-corruption CSOs around the world, including national chapters of Transparency International in Guatemala, Peru, Kenya and Ghana as a means to address corruption in local government (Transparency International 2018: 4). They have the potential to be an effective anti-corruption tool as well as a potential tool for involving civil society in the implementation of policies (Naher et al. 2020: 82).

In Nepal, where social audit committees have undertaken social audits in the health sector, the findings have been communicated publicly alongside the issuance of recommendations and action plans for future improvements in service distribution. Evidence appears to suggest that this had a positive impact on governance and the quality of health services (Naher et al. 2020: 82).

Nevertheless, like participatory budgeting, social audits are not an enforcement mechanism that can counter political corruption (Naher et al. 2020: 82). Moreover, just as is the case with participatory budgeting, social audits are not per definition guaranteed to benefit the affected communities. This was for instance the case in one programme in rural Karnataka where a dominant group captured the process (Rajasekhar et al. 2013).

Community scorecards

Very closely related to social audits is the process of community scoring through community score cards, which scores citizens’ satisfaction with service delivery, and thus the institution responsible for that delivery (Khadka and Bhattarai 2012: 51). The scorecards can identify possible areas of corruption or malpractices in public service delivery.

Following the scoring, involved stakeholders should have a mechanism for follow-up, for instance, in the form of a roundtable meeting or an action plan (World Bank 2012: 9; Khadka and Bhattarai 2012: 52).

Structured evaluation-based evidence on the strength of scorecards as a social accountability mechanism is still lacking, but, in theory, it provides one means of monitoring service provision and institutional quality at a local level (Naher et al. 2020: 90). As such, like other participatory accountability mechanisms, community scorecards provide a channel to simultaneously promote democratic participation in a manner that could also help reduce corruption.

Citizens’ charters

A citizens’ charter is a publicly available document that specifies the obligations of a local government. It will typically set out what services citizens can expect from the government and at what quality (Khadka and Bhattarai 2012: 13). For instance, a citizens’ charter can provide information on what medical facilities and services citizens can expect to be available or the exact procedures involved in obtaining identity documents from local administration offices (Khadka and Bhattarai 2012: 14). A subcategory of citizen’s charters are the so-called entitlement checklists, which provide a clear overview of government entitlements (e.g. pensions, relief) (Khadka and Bhattarai 2012: 18). From an anti-corruption perspective, citizen charters can reduce or eliminate corruption in bureaucracy as they specify what is expected from officials when conducting official business or engaging with citizens.

Citizens’ charters are widespread in both high-income, middle-income and low-income contexts. There is no clear-cut, cross-country evidence of their effectiveness as a tool because their impact seems to rely on the way they are implemented (Nigussa 2013). For instance, Naher et al. (2020: 82) finds that citizens’ charters have often been implemented in a number of local governments across south and southeast Asia with limited effect. Citizens’ charters often had little impact because there was limited awareness about them, were not circulated widely and were also not easily accessible. In most of these cases, the drafting and implementation of the citizens’ charter was a government led process and the limited inclusion of the citizens and communities restricted their effectiveness (Naher et al. 2020: 82). Ironically, citizens’ charters did not result in the intended impact exactly because the approach to them was driven too much by top-down logic.

Similarly, in a randomised control trial from the educational sector in Jaunpur district in Uttar Pradesh, Banerjee et al. (2010) tested the possibility of information based social accountability interventions on parents’ and communities’ involvement in the primary school system. They found that merely informing citizens about the availability and procedures of public services had no significant impact on citizens’ (parents) involvement in the primary school system. The authors suggest that information based mechanisms are not sufficient for increasing citizen involvement. This could be because parents of schoolchildren are too pessimistic about the likelihood of their involvement leading to change (Banerjee et al. 2010: 5). Meanwhile, they found that implementing reading camps was remarkably effective, suggesting that effective collective action needs either some form of “specific pathway” for citizens to influence outcomes (Banerjee et al 2010: 27) or a confidence that the institutions involved will respond.

Complaint mechanisms

A complaint mechanism is a platform for citizens to submit complaints about a public service, a public servant’s conduct or the overall perception of a public institution (OECD 2022: 44). Common mechanisms include hotlines, mailboxes, online or in-person submission forms that should ideally be set up to enable diversity and accessibility. Institutions responsible for handling these mechanisms may include ombuds institutions, courts and any other responsible agency or tribunals (Ringold et al. 2012: 70).

It is important that compliant mechanisms are set up in ways that build citizen accessibility and trust. There should be platforms for anonymous complaints, and efforts should be made to promote access to members of marginalised groups who may fear potential repercussions from filing complaints (Khadka and Bhattarai 2012: 65).

Complaints should be also handled by institutional structures that guarantee independence, reliability and timeliness (Transparency International 2016: 6-8). The implementation of corrective actions also builds citizen trust in the mechanism (see Ardigo 2014; Zúñiga 2020).

Effective complaint mechanisms are an important tool for identifying and preventing corruption and other misconduct. By enabling citizens to report any incidence or suspicion of corruption or other malpractice, complaint mechanisms allow for the identification of problems in public institutions which might otherwise remain unknown and for subsequent corrective action to be taken (Transparent International 2016). As such, they can lead to more participation of citizens in public accountability, which is a key aspect of democratic quality.

Anti-corruption and democratic culture

Democratic culture entails values, attitudes and practices that enable citizens to live freely and participate both individually and collectively in a democratic setting (Balkin 2004; Barrett 2016). A culture of democracy requires active citizens, suitable political and legal structures as well as procedures that support citizens’ exercise of various activities and participation (Barrett 2016: 17).

As part of creating a democratic culture, citizen led anti-corruption movements have been essential in overthrowing leaders around the world. For instance, social movements were instrumental in the removal of dictators in countries such as Libya, Egypt and Tunisia during the Arab Spring. While unfortunately many at the time thought this represented a sweeping democratic transformation in the Arab world, a decade later, the democratic space has shrunk and corruption is also on the rise (Hartmann 2021).

Scholars distinguish between specific “anti-corruption” protests and protests driven by a number of grievances that may be related to corruption (Lewis 2020: 4). Some movements protesting primarily as a result of socio-economic grievances rally around an anti-corruption narrative to advance their cause (Smith 2014). As the term “corruption” is often used by protestors to cover a wide range of economic grievances and democratic failings, it may not be easy to determine the actual drivers of the emergence and durability of anti-corruption movements (Bauhr 2016: 6).

A number of specific anti-corruption protests have been reported to have contributed to democratic awakening. In 2015, hundreds of thousands demonstrators went into the street to demand the impeachment of former Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff as a result of the Petrobras scandal, one of the biggest corruption scandals in Brazil’s history (Watts 2015). Eventually, Rousseff was impeached and removed from presidency. The 2017 anti-corruption protests in Romania were against a law that amended the criminal code and decriminalised certain acts of corruption. According to CIVICUS(2017), the protests “turned the inhabitants of Romania into a whole new generation of alert citizens”.

Freedoms and rights of citizens, and role of civil society and media

Little information is available on how anti-corruption initiatives can lead to the strengthening of basic freedoms. In fact, most literature focuses on how a democratic legal framework that ensures freedoms and rights can enable citizens, civil society and media to take action against corruption. In some parts of the world, unjustifiable restrictions of freedoms of speech and association have been used to clamp down anti-corruption movements. Civil society and journalists working on anti-corruption topics have been harassed and targeted (see Transparency International 2022).

Nonetheless, civil society and media outlets play a crucial role in anti-corruption and contribute to a robust democratic culture. CSOs’ contributions range from raising anti-corruption awareness to participation in policy formation as well as keeping track of the implementation of anti-corruption measures and strategies. CSOs are particularly important in mobilising and empowering citizens to participate in governance issues as well as to exert pressure on governments to become more transparent and accountable to citizens (Škorić 2015).

The African Union’s Charter on Democracy, Elections and Governance Convention, in chapter 5 of the convention, requires state parties “to establish and strengthen a culture of democracy and peace”. This includes establishing necessary conditions for civil society organisations to exist and operate legally.

Media and independent journalists are instrumental in investigating corruption scandals and can also inform and educate people about the devastating effects of corruption. Such exposure of corruption increases constraints on individuals’ cost-benefit analysis (Schauseil 2019).

In addition, civil society and journalists can play a crucial role in protecting victims of corruption and whistleblowers. For example, Transparency International has established Advocacy and Legal Advice Centres in more than 60 countries, which empower individuals, families, and communities to safely report corruption. Another example is the Platform to Protect Whistleblowers in Africa which supports whistleblowers around the continent.

In the era of deep fakes and fake news, which have become a major threat to democracy as well as anti-corruption activism (see Kossow 2018), media houses and civil society organisations play a role in debunking false narratives (Transparency International 2019e). An example is the Ukrainian Stop Fake project, which started in 2014. The organisation gathered fake news and published evidence on their own website that proved the news was fake (Khaldarova & Pantti 2016; Haigh et al. 2017). Similar websites have been established in the United States and other countries that have been affected by fake news (Vargo et al. 2018; Woolley & Howard 2017).

These various activities by media and civil society play an important role in calling out corruption and contributing to a democratic culture in which authority figures are held to account for their actions.

As well as operating independently of each other, some civil society organisations work together with journalists to curb corruption and promote democratic modes of governance. Supporting media actors working in challenging contexts can take different forms. The NGO International Media Support provides not just training in journalistic techniques but also supports independent media in developing business strategies. Their work includes support to the Arab Reporters for Investigative Journalism programme, which trains, mentors, connects and funds investigative journalists in select Arab countries. International Media Support also has a programme focusing on the safety of journalists, which, for instance, provides safe houses for threatened journalists and advocacy for the freedom of expression.

Another example is the Organised Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP), which is a global network of investigative journalists. OCCRP was instrumental in uncovering huge corruption scandals such as the Panama and Pandora papers. The organisation also partners with Transparency International through the project Global Anti-Corruption Consortium, which is a collaboration between the international group of investigative journalists and the global civil society organisations to expose and fight corruption.

There are also emerging opportunities in the digital realm (particularly on investigative matters), such as the burgeoning open source intelligence (OSINT) community.037a37c7d996 The Economist (2021) had arguedthat this was perhaps one of the most promising features of the internet age.

One example of how OSINT can be used in anti-corruption and democracy promotion is the organisation Center for Advanced Defense Studies (C4ADS), which works extensively on areas where corruption, democracy and security intersect. Using OSINT, the organisation’s work uncovered how corrupt networks undermine democracy in Sudan (see Cartier et al. 2022). Recently, international donors have also started becoming involved in OSINT for anti-corruption purposes. For instance, theDanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs has funded capacity building for the National Anti-Corruption Bureau of Ukraine (NABU) on OSINT investigations. The Basel Institute on Governance has also begun providing training on OSINT.

Risks of anti-corruption to democracy

Weaponisation of anti-corruption campaigns

Anti-corruption practitioners should be aware of how the anti-corruption rhetoric can be used to undermine democracy by unscrupulous individuals (Jackson and Amundsen 2022a). For example, anti-democracy and populist leaders can hijack citizens’ grievances to come to power, and once in office turn to non-democratic modes of governance (Kossow 2019; Amundsen and Jackson 2021: 11).

Despotic leaders also hijack and weaponise anti-corruption narratives and campaigns to consolidate power. For instance, they can use the anti-corruption apparatus, such as anti-corruption agencies and special corruption courts, as well as tax authorities, law enforcement and judiciary courts to target political opponents (Jackson and Amundsen 2022b: 8).

Examples include Nigeria where the Independent Corrupt Practices and Other Related Offences Commission, the Economic and Financial Crimes Commission, and the Code of Conduct Bureau and Tribunal were reportedly used by the executive to target and intimidate political opponents (Ojo, Prusa and Amundsen 2019: 86). In Cambodia, a U4 study found that the implementation of anti-corruption reforms, such as public financial management reforms, reportedly helped the Cambodian People’s Party to consolidate power (see Baker and Milne 2019).

The anti-corruption agenda can also be abused by despotic leaders to restrict and bring to heel the directors of nominally independent oversight institutions. For instance, autocrats can accuse potential opponents or independently minded leaders in oversight bodies of corruption and mismanagement as a pretext to limit their work or fire them (Amundsen and Jackson 2021: 12).

Unintended consequences from anti-corruption messaging

Public awareness campaigns against corruption have become a common trend in developing countries (Cheeseman and Peiffer 2020). Anti-corruption campaigns are aimed at sensitising citizens about corruption and its devastating effects, as well as to motivate them to take measures against it. This is in line with article 13(1) of UNCAC, which calls for governments to raise the public awareness of the “existence, causes and gravity of and the threat posed by corruption”.

However, anti-corruption messaging does not always inspire citizens to refrain from engaging in corrupt activities. In fact, it may encourage apathy and behaviours that actually undermine anti-corruption and democracy. For instance, a study in Nigeria revealed that instead of building public resolve to reject corrupt acts, anti-corruption messages either did not yield any positive effects, or they actually made people more likely to engage in corruption (Cheeseman and Peiffer 2022).

Another study in Indonesia found that “negative” messages on widespread corruption worsened citizen concerns about its devastating effects, lowered public confidence in anti-corruption work and decreased the belief that ordinary people can play a role in countering corruption. In addition, even positive messages about anti-corruption successes by government and how citizens can get involved in ways to curb corruption can have negative, unintended influences on perceptions. Even the positive messages about progress in curbing corruption results in decreased satisfaction in the governments’ anti-corruption efforts as well as reduced belief that ordinary people can counter corruption (Peiffer 2018).

Approaches to mitigate risks of anti-corruption to democracy

Doing anti-corruption “democratically”

According to Marquette (2021), anti-corruption should be seen as a means to support democratisation rather than an end in its own right, hence it is imperative that anti-corruption is done “democratically”. One way would be to move away from “solution led” approaches in anti-corruption to “problem-driven” ones, which are more politically feasible and likely to result in better outcomes. Marquette argues that the right starting point to counter corruption in a given context should not be a solution or some sort of universal toolkit. Rather, it should be defining the specific problem that corruption is affecting (Marquette 2021: 7).

When discussing anti-corruption efforts in procurement, a recent World Bank study likewise argued for a more “problem-driven and outcome-oriented” approach that “requires careful analysis of the specific mechanics of corruption, and often the development of sector or ministry-specific approaches to reducing the problem” (Rajni and Bernard 2020: 24).

As part of doing anti-corruption differently, Marquette (2021: 10) argues that there is a need to have more honest conversations on what might not work in anti-corruption and may even weaken democracy, including “being prepared to better test ways in which we can do things differently to how we do things now”.

Contextualising anti-corruption in de-democratisation

According to Amundsen and Jackson (2021: 15), various stakeholders, such as donors, international organisations and civil society organisations, can potentially promote effective anti-corruption in de-democratising regimes. This is possible by thinking through how anti-corruption measures can be used not only to address corruption but to curb the process of de-democratisation.

This entails a strategic approach to anti-corruption in areas susceptible to instrumentalisation by undemocratic leaders. According to the authors, “strategic anti-corruption in de-democratising regimes is about timely and targeted provisions aimed at urgent reinforcement of anti-corruption institutions, along with support to collective action, to frustrate further de-democratisation” (Amundsen and Jackson 2021: 15).

However, these strategies should be adapted to local political circumstances following four steps (Amundsen and Jackson 2021: 16-21):

- Understanding the context, which involves identifying the anti-democratic groups and actors, as well as the institutions, actors and coalitions that have not (yet) been captured.

- Provide urgent reinforcement to institutions and actors that have not yet been captured. This includes support to institutions that still provide institutional checks on the executive such as parliaments, supreme audit institutions and anti-corruption commissions. It is important that the kind of intervention has to be contextualised, localised and timely.

- Support collective action against de-democratisers. This mainly involves supporting broad and inclusive coalitions involving autonomous institutions, pro-democracy figures and any other actors.

- Anti-corruption strategies should be flexible and adjustable to rapidly changing situations as opportunities for pushbacks against anti-democratic forces may appear suddenly and should be addressed.

As anti-corruption rhetoric can also be hijacked and weaponised, the authors recommend that practitioners design intelligent and context specific interventions that include “smart” safeguards and quick exit options. Such interventions and strategic options should be updated frequently to cope with political surprises during implementation (Amundsen and Jackson 2021: 22).

One adaption of this approach is USAID’s Dekleptification Guide, which draws on examples from Romania, the Dominican Republic and South Africa to provide advice to civil society groups and citizens on how take seize windows of opportunity to “root out deeply entrenched corruption… [and] implement radical transparency and accountability measures” (USAID 2022).

Do not harm principle in fragile contexts

The “do no harm” principle in anti-corruption entails refraining from implementing poorly thought out reforms that would likely do more harm than good (Johnston 2011). In fragile settings, anti-corruption may not only be difficult to implement, but if poorly conceived or executed, it may worsen the country’s social, political and economic conditions by imposing unrealistic expectations, targets on public institutions, and may even weaken political linkages and social trust (Johnston 2011: 2).

Reforms that are rapidly devised or lack the necessary institutional and political backing may increase uncertainties, and may even create new opportunities for abuses. In particular, anti-corruption initiatives that threaten corrupt elites without strengthening balancing forces may give rise to repression or even incentivise corrupt elites to loot more resources, or both (Johnston 2011: 2-3). In the worst case scenario, it may exacerbate the fragility of the state (Jenkins et al. 2020).

According to Jenkins et al. (2020: 19), “perhaps the most important lesson to guide anti-corruption efforts in fragile settings is that all efforts need to be tailored to the local context”. They argue that to avoid doing more harm than good in fragile settings, contextualisation is crucial and any anti-corruption intervention logic in fragile settings should consider the following principles (Jenkins et al. 2020: 20):

- Though recognising its importance in enhancing government performance, trust in institutions and economic growth, anti-corruption should been seen a means to reduce the drivers of fragility and not as an end itself.

- Anti-corruption strategies in fragile settings should recognise that corruption is political. While petty corruption is often most visible, grand and political corruption usually have the greatest bearing on fragility.

- Lastly, “donor strategies should explicitly address the timing of interventions, seeking to embed practices that simultaneously contribute to reduced corruption and fragility at an early stage, as well as working with the grain to support domestic reformers. While aid agencies should be ready to scale up their ambitions where windows of opportunity present themselves, they must also be prepared to commit to incremental strategies that extend beyond a single electoral cycle”.

Some recommendations for donor support of anti-corruption in fragile contexts include supporting initiatives by non-state actors that build social cohesion, coordinating efforts with other stakeholders, deploying vigorous political economy analysis during the design and implementation of anti-corruption strategies, as well as being pragmatic and patient (Jenkins et al. 2020: 21-33).

- Anti-corruption measures, for the purpose of this paper, refers to common approaches specifically intended to prevent and curb corruption, rather than all policies that may result in reduced corruption as a spill-over effect, such as modernisation of the tax system.

- An example of an ongoing project is the EU-funded Consolidation of the Justice System in Armenia, which aims to provide support to Armenia’s judicial reform process.

- See also https://www.agora-parl.org/resources/aoe/preventing-corruption-mps

- See https://www.u4.no/terms#lobbying

- Open Source Intelligence entails “the practice of collecting and analysing information gathered from open sources to produce actionable intelligence. This intelligence can support, for example, national security, law enforcement and business intelligence. OSINT investigates open (source) data collected for one purpose and repurposes it to shed light on hidden topics. The whole concept of OSINT sounds counter intuitive—using open data to reveal information that organisations want to keep secret” See https://data.europa.eu/en/datastories/open-source-intelligence