Query

What are some of the major contemporary concepts in the study of corruption? Who are the “big thinkers” involved in these discussions?

Caveat

The concepts and scholars cited in this Helpdesk Answer are not intended to be exhaustive. Instead, this paper provides a snapshot of selected works within specific theoretical areas that have had a particular impact in recent decades.

Background

This Helpdesk Answer provides an overview of notable recent theoretical innovations in relation to corruption that have been developed by experts and scholars over the last 20 years. Corruption as a distinct field of study first rose in prominence within scholarly discourse during the late twentieth century, when the likes of Banfield, Klitgaard, Rose-Ackerman, Kaufmann, Eigen and others discussed its definition, causes and consequences. At the same time, methodologies and indicators were developed in an attempt to quantify levels of corruption and assess its extent.

Corruption was (and still is) widely understood as an impediment to economic development and, as such, anti-corruption interventions have become a standard element of development programmes (Kuipers 2021). Conventional anti-corruption approaches often prioritised criminalisation, law enforcement and punitive sanctions through legal and technical reforms. These efforts have sought to ensure that corrupt behaviour is prohibited, increase the probability of detection and raise the costs of being penalised for corruption (Marquette and Peiffer 2015). As discussed in Box 1, these measures were designed in response to the conceptualisation of corruption as a so-called principal-agent problem.

Today, the number of scholars and organisations writing about corruption has grown substantially. While economists were in the past heavily represented among those studying corruption, the phenomenon is now examined by academics from a large variety of disciplines, including political science, history, behavioural economics, psychology, political economy, criminology, sociology and anthropology. Many of the ideas and concepts emanating from these fields of study have had direct impacts on policymakers and development practitioners.

The broad understanding of the drivers, patterns and forms of corruption has also evolved beyond the neat models of rational actors that underpinned much of the early academic work in the field. While individuals’ cost-benefit calculus is still often viewed as central, increasingly, contextual and non-material factors such as social relationships are considered to be important drivers of corrupt behaviour. At a macro level, corruption is no longer only viewed within the confines of the nation-state but also as part of a globalised financial system that enables corrupt money flows to cross borders with ease.

The collective experience of several decades of anti-corruption interventions has cautioned reformers about the need to respond to the demands of each local settings and not simply attempt to transplant institutional models from low-corruption to high-corruption environments (Mungiu-Pippidi et al. 2011). This turn away from top-down approaches is also reflected in the measurement of corruption, as scholars have looked to proxy indicators and subnational or sectoral data to measure corruption in a more granular manner. Emerging technologies are becoming increasingly prominent, such as the use of artificial intelligence to detect red flags that could indicate money laundering and the digitalisation of government services to improve the transparency and accountability of the state.

Despite these advances, there are still nonetheless many areas in which the evidence based on corruption – and the appropriate means of controlling it – is contested by different schools of thought. This Helpdesk Answer seeks to provide an overview of a select number of these debates and highlight major contributions by leading scholars in each respective area.

Box 1: Traditional understandings of corruption

While the study of corruption is not new, its prominence rose in the second half of the twentieth century, partly stimulated by the emergence of newly democratising low and middle-income countries (Farrales 2005). Much of the research into corruption at the time focused on its definition and classification, as well as the development of various typologies of corruption (administrative vs political, grand vs petty, public vs private and so on).

The concepts of political corruption, and “grand” versus “petty” corruption, became more established as well as the notions of local and national level corruption (Heywood 1997). Many of the most high-profile researchers at the time (Rose-Ackerman 1978; Klitgaard 1988) based their work on the principal-agent theory of corruption. According to this model, corruption occurs when agents (typically public officials) abuse their entrusted power for personal gain at the expense of the principal (generally citizens) who, while having nominal authority over agents, are unable to fully monitor or control their behaviour. Principal-agent models foregrounded corruption as an individual rather than systemic issue (Farrales 2005). The negative economic impacts of corruption and especially its role in impeding economic growth became a common theme of scholarly work in the 1990s, which sought to refute the view that corruption acted to grease the wheels of lumbering bureaucracies (Mauro 1995; Ades and Di Tella 1997; Goudie and Stasavage 1997).

Conceptualising the drivers and forms of corruption

Transnational corruption

Traditionally, the study of corruption – conceived of as the abuse of power (or more narrowly public office) for private gain – limited itself to behaviour confined within national borders. As such, it is little surprise that the dominant approach to curbing corruption – encapsulated in the United Nations Convention against Corruption – centred on domestic criminal and administrative law. However, recent decades have seen a growing interest in the concept of “transnational corruption”, which refers to cross-border forms of corruption enabled by a globalised financial system.

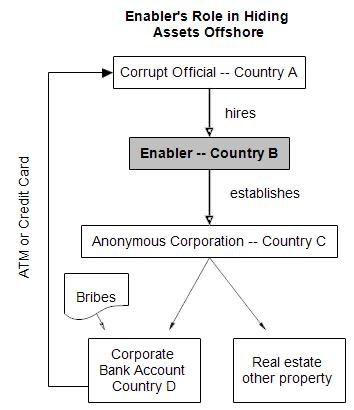

Heywood (2016: 7), for instance, has been prominent in arguing that the traditional scope of corruption that focused on individual states served the interest of high-income countries, which tend to perform well on global indices comparing countries in terms of the incidence of corruption. This, he contends, allowed governments in industrialised countries to overlook the role of actors in the Global North in facilitating corruption in low and middle-income countries. In this view, the architecture of international finance, shaped chiefly by Western countries, creates incentives that stimulate and vulnerabilities that enable the misappropriation of funds and their transfer and disbursement overseas (Heywood 2016: 7). A key role in the cross-border flow of such “dirty money” is played by so-called professional enablers, such as lawyers, notaries, accountants and corporate service providers. These enablers often operate in financial centres, tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions, and a favoured technique is the use of shell companies to obscure the true beneficial owner of ill-gotten gains.

The role of the financial and service industries in facilitating transnational corruption has climbed the research agenda in recent years. With the help of whistleblowers and investigative journalists, the sheer scale to which the global financial system is being misused has gradually come to light. In 2016, for example, the Panama Papers revelations exposed a global network of over 200,000 offshore entities (primarily shell companies) linked to the law firm Mossack Fonseca (ICIJ n.d.). While this was not the first scandal around the use of shell companies for money laundering, it was the largest and perhaps most high-profile in recent history. The law firm Mossack Fonseca acted as a corporate service provider to set up hard-to-trace companies, trusts and foundations to help obscure their beneficial ownership structures (ICIJ n.d.). This has led multiple scholars to analyse the ways in which shell companies and other corporate vehicles move the illicit gains from corruption (particularly grand corruption) around the globe (see Fisman and Golden 2017; Heywood 2016; Heywood 2018).

Cooley and Sharman (2017) have made a prominent contribution to the “new, more transitional, networked perspective on corruption”. They adopt this approach in conscious opposition to the traditional view of corruption, which they characterise as depicting corruption as relating to “direct, unmediated transfers between bribe-givers and bribe-takers, disproportionately a problem of the developing world, and as bounded within national units”. In contrast, analysis by Cooley and Sharman (2017) of how transnational networks facilitate corruption foregrounds professional intermediaries in major financial centres and centres on their role in assisting senior foreign officials to move illicit finance, acquire property and secure residence and citizenship rights.

Figure 1: How corporate service providers (otherwise known as “enablers”) hide the proceeds of corruption for their clients

Source: Messick, R. 2020. Three measures to put corruption enablers out of business. The Global Anticorruption Blog.

Tackling transnational corruption through beneficial ownership transparency and international cooperation

Sharman’s (2012) policy brief sets out how shell companies are used to conceal the proceeds of corruption and move illicit wealth by obscuring the connection to the real beneficial owner of the assets. His recommendations include mandating beneficial ownership registers and awareness raising with counterparts in national governments, as well as the effective implementation of the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) Recommendations (Sharman 2012). Sharman (2013) further focuses on additional measures to crack down on shell companies. In the brief, he outlines the important elements of an effective regulatory regime, which include (Sharman 2013: 2):

- the licensing of corporate service providers by a government regulator

- requirement of foreigners looking to form a company to use a local resident corporate service provider in that jurisdiction

- mandate confirmed beneficial ownership

- licensed corporate service providers should be reporting entities within the national anti-money laundering system

Van der Does de Willebois et al. (2011) refer to a “tiered structure” of corporate vehicles, which is used to obscure the ultimate beneficial ownership of a company. The authors draw attention to a further important complication in transnational corruption: that information about the beneficial owner will either be unavailable or accessible only at a specific location (Van der Does de Willebois et al. 2011). Therefore, bits of information need to be pieced together from different sources in different jurisdictions, making corruption investigations difficult and time-consuming. They further explain the mechanisms of hiding ownership through nominees (a selected person who holds a position or assets in name only on behalf of someone else) and front men (a hired employee selected to be named as the beneficial owner) (van der Does de Willebois et al. 2011).

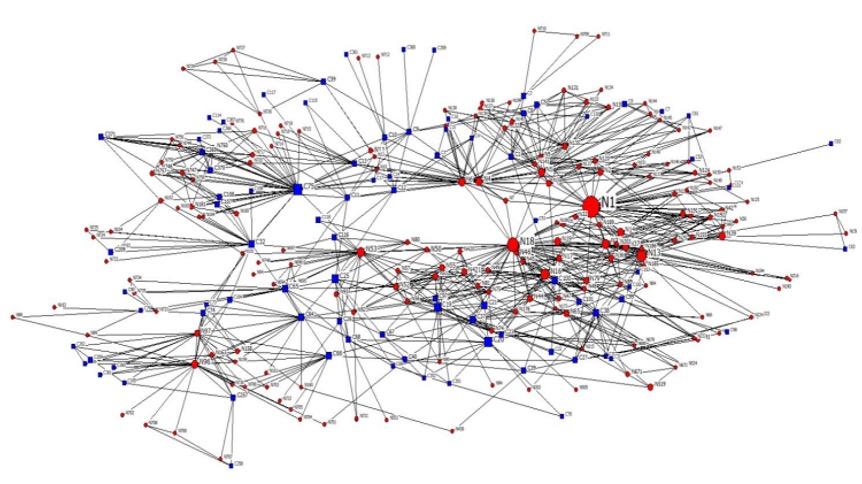

The complex structure of transnational corruption has been addressed by Costa (2021) in an attempt to identify perpetrators by applying a network lens. Costa (2021) does so through a combination of social network analysis and network ethnography techniques. This analysis allows a detailed mapping of the network of actors implicated in the corrupt deal between Toledo and Odebrecht,345bd1ae9083 showing a large network of 281 different nodes, 193 of which are individuals and 88 are collective entities. Costa (2021: 11) maps this complex network in the report, as displayed in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Transnational informal network, Toledo-Odebrecht connection

This figure presents the network of actors who intervened to materialise the corrupt deals between former President Alejandro Toledo and the Odebrecht Group. It consists of 281 nodes, of which 193 are individuals, and 88 are collective entities. Individuals are represented as red points (Nx) and collective entities as blue squares (Cx).

Source: Costa 2021: 11. The nexus between corruption and money laundering: deconstructing the Toledo-Odebrecht network in Peru.

This intricate web of formal and informal relations comprises of mainly middle-aged men from Brazil and Peru, businesspeople and high and mid-level politicians, bureaucrats, lawyers and accountants. The collective entities include corporate vehicles and service providers. This transnational network channelled financial flows through a web of shell companies based throughout central America. Costa’s analysis shows a cross-border, highly technological and complex exchange involving transnational informal networks and hidden financial infrastructures to hide the beneficiaries of the corrupt agreement (Costa 2021).

David-Barrett and Tomić (2022) argue in their research that transnational corruption requires global cooperation among law enforcement agencies to be able to “follow the money” across borders (David-Barrett and Tomić 2020: 6). However, law enforcement faces technical and resource obstacles when trying to cooperate as well as various power imbalances. Their paper analyses an example of law enforcement agencies who have formed a coalition to share intelligence to curb grand corruption: the International Anti-Corruption Coordination Centre (IACCC). David-Barrett and Tomić (2022) note that the IACCC is expanding the capacity of collective effort through international coordination and effective referrals to the relevant agency with the authority to initiate a prosecution.

Recommended reading

Alexander Cooley and Jason Sharman: Transnational corruption and the globalized individual.

Elizabeth David-Barrett and Slobodan Tomić: Transnational governance networks against grand corruption: Cross-border cooperation among law enforcement.

Jacopo Costa: Revealing the networks behind corruption and money laundering schemes.

Jason Sharman: Tackling shell companies: Limiting the opportunities to hide proceeds of corruption and Preventing the misuse of shell companies by regulating corporate service providers.

Paul Heywood: Rethinking corruption: Hocus pocus, locus and focus and Combating corruption in the twenty-first century: New approaches.

Raymond Fisman and Miriam A. Golden: Corruption: What everyone needs to know.

State capture

The notion of state capture as a type of systemic corruption has evolved and been refined in recent decades. The term “state capture” was first used to describe the patterns of systemic political corruption observed in the first decade of post-communist transition to democracy in Eastern Europe (David-Barrett 2024). Liberalisation and privatisation at the time enabled politicians and bureaucrats to maximise their private interests and powerful firms were able to capture and collude with public officials to extract rents, resulting in the term “state capture” (Hellman, Jones and Kaufmann 2000).

In the past 10 to 15 years the concept has been used to describe a much wider range of countries, including some that were once viewed as resilient democracies (David-Barrett 2024). When state capture happens in democracies, it is referred to as “democratic backsliding” (David-Barrett 2021).

Fazekas and Tóth’s (2016) work on state capture based on analysis of public procurement data is particularly innovative and noteworthy. Looking at procurement data from Hungary between 2009 and 2012, the authors identify a distinct network structure in which closely connected corrupt actors cluster around parts of the state (Fazekas and Tóth 2016). According to the data, state capture is an established daily practice in approximately 60% of public sector organisations in Hungry.

An increasingly sharp conceptual differentiation is being drawn between policy capture, corporate capture and regulatory capture (David-Barrett 2024). The OECD defines policy capture as “the process of consistently or repeatedly directing public policy decisions away from the public interest towards the interests of a specific interest or group” (OECD 2017: 9). Notably, policy capture involves the capture of the policymaking process, but the captor is not specified (David-Barrett 2024). Corporate capture involves a large company or group of companies but leaves open the question of what is captured. And regulatory capture means that the regulatory process is captured by a group (which is intended to be regulated) and may be a result of the revolving door (David-Barrett 2024: 309).

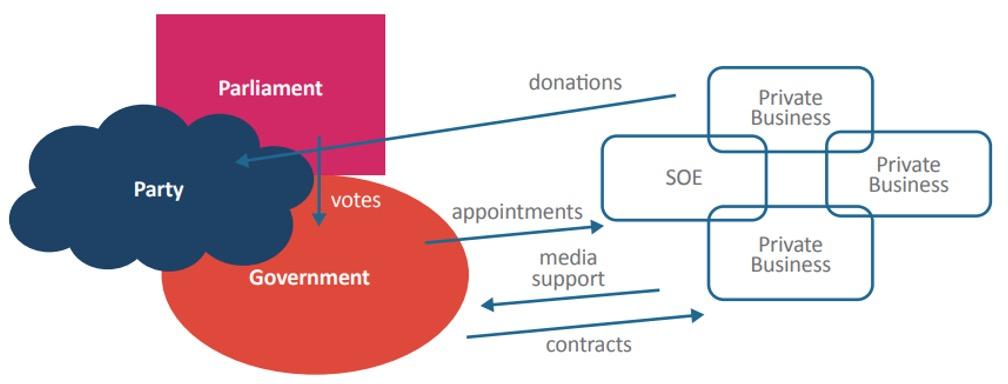

David-Barrett (2023) suggests that state capture happens through specific mechanisms in three pillars: influencing the formation of law and policy; influencing the implementation of policy; and disabling the accountability institutions. As an example of the process:

- The independence and capacity of accountability institutions, such as supreme audit institutions, are as targeted by corrupt actors embedded in the state to cripple the ability of these institutions to hold power to account.

- This is achieved through strategies such as appointing political allies as judges, reducing the budget of supreme audit institutions and dismissing prosecutors or attorneys general who challenge the incumbent elite.

- This results in hollowing out the rule of law by politicising judicial decisions, diverting prosecutors from prosecuting wrongdoing and reducing the ability of audit institutions to reveal irregularities (David-Barrett 2021: 12).

Figure 3: A typical captor network

Source: David-Barrett, E. 2021. State capture and inequality. Pathfinders.

Importantly, state capture generally deepens inequality in a state through shaping law-making and policy implementation to benefit those who occupy the most powerful positions (David-Barrett 2021). It neutralises institutions and organisations that are intended to act as checks on that power and act as a voice for the less powerful groups in society (David-Barrett 2021: 13). In the long term, state capture also results in a “brain drain” and the delineation of elites from the public, leading them to live entirely separate lives from ordinary people (David-Barrett 2021: 15-16). David-Barrett (2021: 15) also highlights how state capture intensifies stratification in societies as captor groups give advantages to a clearly defined group of allies, often according to identities associated with kin, tribe, ethnicity or regional identity.

Another approach to understanding state capture has been put forward by Wedel (2011), who describes what she terms a “shadow elite” that conflates official and private interests, often without violating the law. According to her, this “new breed of power” exercises outsized influence to distort public policy (Wedel 2011: 150). With more and more government functions being conducted outside of government in consulting firms, think thanks and corporate boardrooms, there are bountiful opportunities for deeply anti-democratic forms of decision-making that prioritises a narrow set of private interests (Wedel 2011).

Finally, an expansion in theoretical discussions on state capture is the notion that one state can “capture” another. Siegle (2022) labels Russia’s expanding influence in the African continent as state capture. He argues that Russia has opportunistically captured the allegiance of a series of politically isolated leaders to gain access to natural resources and opaque contracts (Siegle 2022). This has led to influence over national policies of the captured state, which swing in Russia’s geostrategic interests (Siegle 2022).

This debate is closely related to the rise in the past several years of a discourse around strategic corruption. Particularly among US security advisers, a view has emerged of strategic corruption related to the use of corrupt means to increase influence and shape the political environment in a targeted country (see Zelikow et al. 2020). In its most organised form, “corrupt inducements are wielded against a target country by foreigners as a part of their own country’s national strategy” (Zelikow et al. 2020).

Recommended reading

Elizabeth David-Barret: State capture and inequality and State capture and development: a conceptual framework.

Fredrik Larsson and Marcia Grimes: Societal accountability and grand corruption: How institutions shape citizens’ efforts to shape institutions.

Jane R. Wedel: Beyond conflict of interest: Shadow elites and the challenge to democracy and the free market.

Joseph Siegle: How Russia is pursuing state capture in Africa.

Michaela Elsbeth Martin and Hussein Solomon: Understanding the phenomenon of “state capture” in South Africa.

Mihály Fazekas and István János Tóth: From corruption to state capture: A new analytical framework with empirical applications from Hungary.

Discriminatory dimensions of corruption

The discriminatory dimensions of corruption are increasingly discussed, both in terms of how corruption can deepen pre-existing inequalities in societies and how tackling inequality holds potential as an anti-corruption strategy.

Studies have found that discrimination can result in greater exposure to corruption and that corruption has a disproportionate impact on certain groups (such as those marginalised due to their income, sex, age, race, ethnicity, migratory status, disability or other characteristics) (McDonald, Jenkins and Fitzgerald 2021). In addition, corruption increases the barriers for marginalised groups to access public services and to report corruption (McDonald, Jenkins and Fitzgerald 2021).

For example, women are more vulnerable to extortive forms of corruption, which may be due to the fact that corrupt officials assume that women lack recourse to justice, are unaware of their rights or have no formal employment protection (Boehm and Sierra 2015).

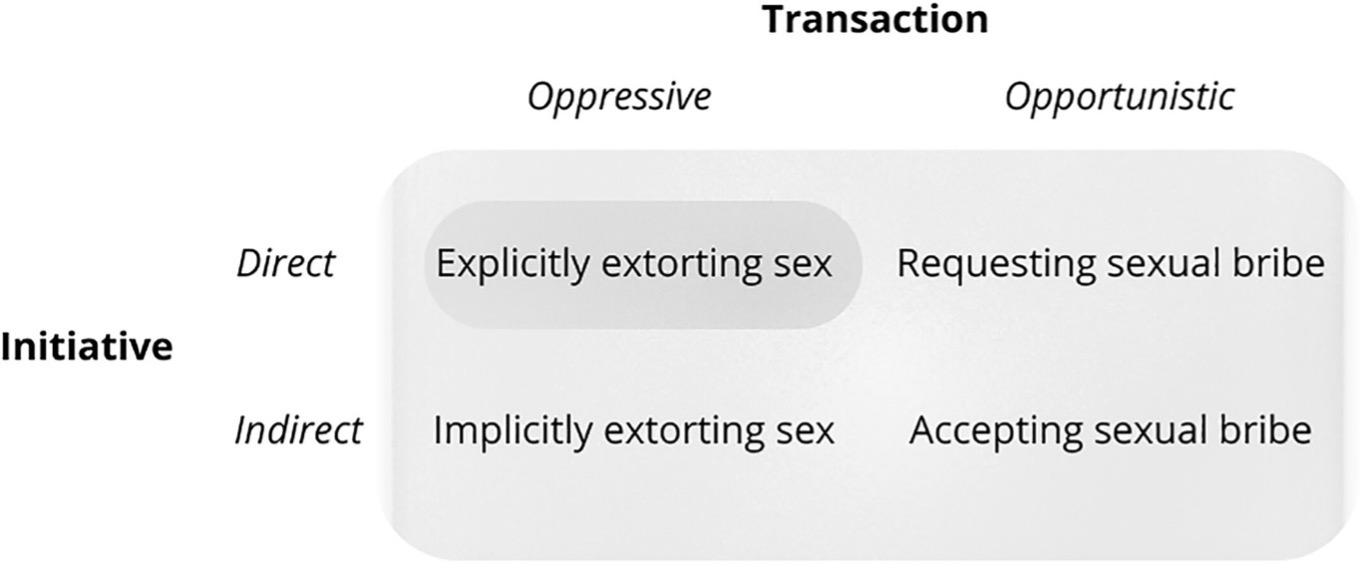

Bjarnegård et al. (2024) propose that the definition of corruption as the abuse of entrusted power for personal gain implies that corrupt abuses of power can also involve sexual acts as well as (or in place of) money. The authors advance a broad conceptualisation of sexual corruption that goes beyond the traditional focus on sextortion, whereby those in power coerce sexual acts in return for goods or services to which the victim is entitled (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Dimensions of abuse of entrusted authority in sexual corruption

The definition of sexual corruption builds on abuse of entrusted authority. Sexual corruption includes abuse of entrusted power regardless of whether the initiative was direct or not, and it incorporates extortion and bribery as oppressive and opportunistic transactions respectively.

Source: Bjarnegård, E. et al. 2024. Sex instead of money: Conceptualizing sexual corruption. Governance.

However, despite mounting evidence that women and girls are particularly vulnerable to sexual corruption, research shows there is still very little in the way of a legal definition or framework for it, making prosecution of cases difficult worldwide (Feigenblatt 2020).

Indigenous people may be particularly affected by forms of corruption, such as the fraudulent acquisition of land rights, as they often live in areas rich in natural resources, which is further exacerbated by the fact that their customary land rights are often not legally recognised (McDonald, Jenkins and Fitzgerald 2021).

Fried, Lagunes and Venkataramani (2010) examine the interaction between corruption and socioeconomic inequality. They conducted an experiment that looked at the manner in which police officers in a major Latin American city responded to socioeconomic distinctions when requiring a bribe. They identify the effect of citizens’ perceived wealth on officers’ propensity to solicit bribes, as well as the size of bribes and combine this with qualitative findings from interviews with officers. Their findings were that officers are more likely to target lower class individuals.

Despite scholars (and development practitioners) offering evidence on the discriminatory nature of corruption, Pyman shows through his research at over 40 national anti-corruption strategies at a panel at SOAS University of London, that not one of these strategies listed reducing inequality as an objective (SOAS n.d.).

Gender equality as an anti-corruption tool?

Bauhr, Charron and Wängnerud (2018) in their policy brief argue that the inclusion of women into locally elected councils decreases both grand and petty corruption. They argue that while gender equality is a vital part of the human rights agenda, the inclusion of women in elected assemblies has a knock-on effect in reducing corruption.

However, some of their later work paints a slightly more nuanced picture on the relationship between gender and corruption. Bauhr and Charron (2020 a) used data from French municipal elections combined with corruption risk data on almost all municipal contracts awarded between 2005 and 2016 and found that, overall, women mayors reduce corruption risks.

However, newly elected women mayors drive these results, whereas re-elected women mayors do not. Bauhr and Charron (2020 a) conclude that this indicates that women eventually adapt to the corrupt networks to survive. They hypothesise that new women mayors reduce corruption levels as they are socialised or incentivised into having a stronger demand for anti-corruption reforms, or perhaps because they lack the opportunities to participate in corruption transactions since they are excluded from the often-male dominated networks (Bauhr and Charron 2020 a).

In another study, Baur and Charron (2020 b) analyse whether men and women perceive corruption differently, due to their role socialisation, social status and experiences. They suggest in this paper that women are more likely than men to perceive corruption as driven by need than greed as they are more likely to be exposed to “need corruption” due to the fact they are more likely to be care providers for other people. This may happen, for example, in the education or healthcare sectors, supporting the marginalisation theoryfb6e56237730 that women are on average excluded from positions and decision-making areas where greed corruption is likely to take place (Bauhr and Charron 2020 b).

Recommended reading

Brian J. Fried, Paul Lagunes and Atheendar Venkataramani: Corruption and inequality at the crossroad: A multi-method study of bribery and discrimination in Latin America.

Ellie McDonald, Matthew Jenkins and Jim Fitzgerald: Defying exclusion: Stories and insights on the links between discrimination and corruption.

Frédéric Boehm and Erika Sierra: The gendered impact of corruption.

Hazel Feigenblatt. Breaking the silence around sextortion.

Monika Bauhr and Nicholas Charron: Will women executives reduce corruption? Marginalization and network inclusion and Do men and women perceive corruption differently? Gender differences in perception of need and greed corruption.

Monika Bauhr, Nicholas Charron and Lena Wängnerud: Close the political gender gap to reduce corruption.

Legalised corruption

Legalised corruption is a term used to describe “less obvious forms” of corruption that may be legal in some countries and can involve both the private and public sectors (Kaufmann 2005). It is also used to express concerns about how the influence of concentrated wealth can distort the political process and tilt policy outcomes in a direction that favours the affluent (Stephenson 2018). In this sense, legalised corruption could be used to consolidate power to capture a state. Scholars writing on the topic often focus on countries in the Global North, which tend to perform well on comparative international governance indexes.

The term has been often used to describe campaign financing and lobbying in the US and implies transactional influence (Stephenson 2018). Others use it to describe permitting companies to pay minimal tax, cronyism, land grabbing, effective immunity from prosecution granted to large corporations, tolerance to conflict of interest and the work of corporate service providers (WRM 2021).

Maciel and de Sousa (2018) offer a definition of legal corruption that relates to where specific powerful groups consolidate power through legal practices (such as regulatory distortion, lobbying, the revolving door, policy capture, favouritism) that benefit specific groups at the expense of the majority. They argue that legal corruption has been the driving factor in citizens’ dissatisfaction with democracy in the EU as it undermines the trust of citizens in democratic institutions and processes. Therefore, anti-corruption laws alone will not have a positive impact as these need to be integrated into a more comprehensive approach which includes improving institutions and processes affecting the daily running of politics (Maciel and de Sousa 2018).

Dincer and Johnston (2020) categorise corruption in the US as both legal and illegal. They define illegal corruption as private gains in the form of cash or gifts given to a government official in exchange for providing specific benefits to certain individuals or groups. Their definition of “legalised corruption” relates to political gains in the form of campaign contributions or endorsements offered to a government official in exchange for providing benefits to a group or individual. They find that voter participation and media coverage have an impact in decreasing “legal corruption” if the media covers corruption adequately, leading to a better-informed public (Dincer and Johnston 2020: 17).

Fisman and Golden (2017: 28) note that focusing on legal standards can lead to “different interpretations of the same behaviour in different countries” so that “using a legal standard to decide what is corrupt generates legitimate confusion.” In a similar vein, Giovannoni (2011) argues that relying on legal distinctions between legitimate (non-corrupt) and illegitimate (corrupt) forms of lobbying is misguided.

Seen in this light, corruption and lobbying are two sides of the same coin; aside from voting, they constitute the main means for private entities to influence public policy (Giovannoni 2011: 12). Giovannoni (2011: 16) goes on to argue that, as twin forms of rent-seeking activity, lobbying and corruption are substitutes rather than complements. As such, businesses may choose one strategy over another depending on contextual factors such as the strength of political institutions in the country, resulting in lobbying being a more viable rent-seeking strategy in democratic high-income countries than corruption (Giovannoni 2011).

Conversely, Stephenson (2018) disagrees with the use of the term legalised corruption, particularly when used to describe “legalised bribery” in the US political system. In terms of lobbying, he contends that a great deal of related activity is legitimate public advocacy, often providing the policy expertise needed to craft a certain law or regulation. The tools used to influence public policy in themselves are not corrupt. It is simply an example of where wealthy individuals or groups hold concentrated power over the masses, which is unfair, but not in itself an example of corruption (Stephenson 2018).

Recommended reading

Daniel Kaufmann: Legal corruption.

Gustavo Gouvêa Maciel and Luís de Sousa: Legal corruption and dissatisfaction with democracy in the European.

Matthew Stephenson: Is the US political system characterized by “legalized corruption”? Some tentative concerns about a common rhetorical strategy.

Oguzhan Dincer and Michael Johnston: Legal corruption?

Prominent approaches to preventing and countering corruption

Dynamic studies

When scholars or practitioners design an anti-corruption intervention, it is important to analyse the drivers, forms and types of corruption that they are aiming to address. One way to do so is to employ so-called dynamic studies, which include political economy analyses, political settlement analyses and corruption risk assessments (Wathne 2021: 43).

Political economy analyses

Over the last 30 or so years, the governance agenda has firmly established itself in development theory and policy. This process has been accompanied by attempts to develop tools able to account for governance issues in development programming, which can be broadly referred to as political economy analyses (PEA).

PEA seeks to understand how wealth and power are distributed and exercised within a society, which institutions and policies shape economic outcomes, the patterns of resource distribution and how these are situated in the wider international economy. Importantly for anti-corruption practitioners, PEAs can be conducted alongside and used to inform corruption risk assessments (Rocha Menocal et al. 2018).

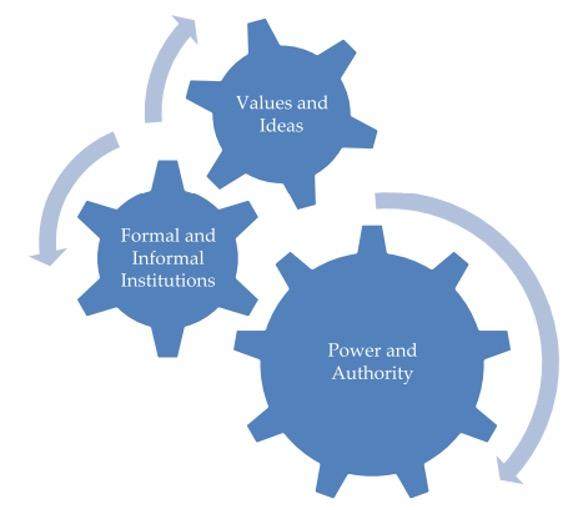

Figure 5 presents the wheels of political economy analysis by Serrat (2017: 209), who notes, “in a nutshell, PEA investigates the interaction of political and economic processes in a society, in the context of historical legacies”. It scrutinises the:

- power and authority of groups in society, counting the interests they hold and the incentives that drive them, in conducing particular outcomes

- the role that formal and informal institutions play in allocating scarce resources

- the influence that values and ideas, including culture, ideologies and religion, have on shaping human relations and interaction (Serrat 2017: 210)

Green (2014) and Fisher and Marquette (2014) identify successive “generations” of PEA that have surfaced over the past few decades. The first generation, which emerged in the 1990s but continues to be practised in some quarters, adopted a stringently technocratic, capacity building and public sector managerial perspective.

The second phase has been instrumental in “bringing the politics back in” to development programming, and emphasising the role that historical, structural, political and institutional factors (previously considered “externalities”) play in setting the parameters for development interventions (Green 2014). It was during this period that donors began to seriously consider how “politics”, broadly understood, is a critical determinant of project success (Chêne 2009).

As such, PEA is not a best practice but rather an umbrella term for a number of approaches that place power relations at the centre of programme planning and delivery. The intention is to improve rates of success through the use of better contextual analysis to identify obstacles to and opportunities for reform. Small but vocal groups of practitioners and experts have developed various analytical frameworks for PEA, such as SIDA’s Power Analysis, DFID’s Drivers of Change or the Strategic Governance and Corruption Analysis used by the Netherlands’ Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Yanguas & Hulme 2014).

Such a consensus is based upon mounting evidence that so-called “traditional” development approaches, which prioritise capacity building and technical assistance, often produce poor outcomes due to their neglect of the power dynamics all development assistance is contingent upon (Andrews 2013; Carothers & de Gramont 2013).

In the anti-corruption field in particular, Khan, Andreoni and Roy (2019) observe that conventional approaches have typically delivered poor results in developing countries as they focus on improving the enforcement of a rule of law and raising the costs of corruption for officials. They argue that, in contexts where the distribution of power allows actors to violate the rules, strengthening the enforcement of rules is unlikely to produce positive results.

As such, PEA is thought to be useful in finding pathways to more effectively increase political will to target reform priorities (Kassa, Costa, Stahl and Baez Camargo 2022). When used alongside a corruption risk assessment, it can help practitioners to better understand corruption risks within a specific context (country, region and/or sector) and helps to design mitigation measures that take prevailing political and power dynamics into account (Kassa, Costa, Stahl and Baez Camargo 2022).

Figure 5: The “wheels of political economy analysis”

Wheel 1: Values and ideas

Wheel 2: Formal and informal Institutions

Wheel 3: Power and authority

Source: Serrat 2017. Political Economy Analysis for Development Effectiveness.

Yet, despite the fact that most development agencies now have dedicated staff working on PEA, efforts to mainstream such approaches have encountered several obstacles, including “stiff opposition” within donor agencies (TWP Community of Practice 2016a), as well as administrative hurdles, institutional constraints and cultural inertia (Effective States and Inclusive Development 2014). Previous evaluations of DFID and World Bank programmes concluded that the use of political economy analysis remains a “largely intellectual agenda rooted in the governance silo” (Yanguas & Hulme 2014).

Critics allege that PEA is too often a one-off exercise and its findings and recommendations become subordinated to the broader programmatic logic (Yanguas & Hulme 2014; Halloran 2014). They further contend that existing ways of working, such as the widespread employment of logical frameworks, generally foster rigid and linear programme structures unsuited to the changing environment which a programme invariably experiences over its lifecycle (Algoso & Hudson 2016). In this view, the failure of PEA to overcome existing working practices typical of major donor agencies has hamstrung PEA’s potential to improve programme success rates (Carothers & de Gramont 2013).

Over the past decade, a growing section of the development community – both programme staff and academics – has become increasingly frustrated with the limitations of existing PEA approaches. The result has been a proliferation of alternative schemas and management approaches to combine the fruits of PEA with programmatic setups able to foreground politics and promote “responsive, adaptable and contextually relevant operations” (TWP Community of Practice 2016a).

Many of these initiatives seek to build upon the insights of problem-driven iterative adaptation (PDIA), proposed by Andrews, Pritchett and Woolcock (2012). In their own words, PDIA provides a framework for the development community to go beyond “transplanting other countries’ institutional blueprints” to generate specific solutions to locally nominated problems (Andrews et al. 2015).

Some of the most notable initiatives exploring the use PDIA in development programming are:

- Doing Development Differently: a grouping of researchers and practitioners whose manifesto appeals for development to focus on locally defined problems in an iterative fashion (Building State Capability 2014). When applied to anti-corruption interventions, this implies emphasising endogenous change and local agency in defining and addressing problems related to corruption (Jackson 2020: 11).

- Global Delivery Initiative: a collaboration of donors with the Word Bank acting as secretariat, which aims to curate knowledge about the effective operational delivery of aid (Global Delivery Initiative 2016).

- Thinking and Working Politically: a community of practice translating politically informed approaches into operationally relevant guidance (TWP Community of Practice 2016b).

- Political settlements framework: this approach, pioneered by Khan (2010; 2018) sets out to provide an analytical framework for understanding institutions and governance in developing countries. It spotlights the distribution of power across both formal and informal institutions to document the point of equilibrium (political settlement) at which the distribution of benefits by institutions is consistent with the distribution of power between groups in society (Khan 2010).

Although such approaches are still relatively new, they are designed to depend less on aid conditionality and comprehensive reform of institutions, and instead place a greater focus on working “with the grain” to develop local coalitions in favour of positive change and able to respond to events, risks and opportunities (TWP Community of Practice 2016a; Parks 2016).

Proponents of these initiatives point to a growing number of studies which contend that adaptive, iterative and politically informed programming has produced impressive results (Carothers & de Gramont 2013; Fritz, Levy & Ort 2014; Booth & Unsworth 2014; Wild et al. 2015; Fabella et al. 2011).

Increasingly these analytical frameworks are being applied at the sectoral level to identify root problems that drive people to turn to corruption to solve what Maquette and Pfeiffer (2021: 4) refer to as “corruption’s underlying functionality”. Key to this is understanding the different types of rent being allocated and appropriated in a given sector, the beneficiaries of these rents and the social outcomes attained as a result (Khan, Andreoni and Roy 2019). These sectoral approaches are discussed in the next section.

Recommended reading

Alina Rocha Menocal:Thinking and Working Politically (TWP) through applied political economy analysis (PEA).

Harvard University: The DDD Manifesto.

Heather Marquette and Caryn Peiffer: Corruption functionality framework.

Mushtaq H. Khan: Introduction: Political settlements and the analysis of institutions.

Mushtaq Khan, Antonio Andreoni and Pallavi Roy: Anti-corruption in adverse contexts: strategies for improving implementation.

Olivier Serrat: Political economy analysis for development effectiveness.

Saba Kassa, Jacopo Costa, Cosimo Stahl and Claudia Baez Camargo: How political economy analysis can support corruption risk assessments to strengthen law enforcement against wildlife crimes.

Sectoral approaches

A sectoral approach to anti-corruption refers to the design of interventions that focus on specific sectors, recognising that each sector has its own specific challenges and opportunities. For example, corruption in the education sector will present different problems and involve different actors to corruption in the natural resource management sector.

Approaching anti-corruption at the sectoral level (rather than at a broader governance level) helps reformers to understand the economic incentives that drive a specific sector, the language of the sector, the social norms that govern peoples’ behaviour and the political specificities of the sector (Pyman n.d.). Pyman (n.d.) argues that there are around 20 to 40 core governance challenges in each sector that are recognisable to those working there. Producing a typology in each sector therefore allows practitioners to focus on the relative importance of the issues, which ones could be feasibly tacked and ensure participation from those within the sector (Pyman n.d.).

Roy, Khan and Slota (2022) also support a sectoral approach to anti-corruption, particularly in countries where corruption is widespread and rule of law is weak. This context means that top-down all-of-government reforms have little impact (Roy, Khan and Slota 2022). Sectoral approaches to anti-corruption efforts therefore can embed integrity measures as an integral part of relevant sectoral policies (Roy, Khan and Slota 2022: 5).

Somewhat linked to sectoral approaches is sequencing interventions. Sequencing anti-corruption measures involve a gradual approach predicated on flexibility and sustainability, as systems practices and support are built step by step (Wathne 2021: 32). Sequencing is seen as particularly important in fragile states as interventions are timed at a pace that should not put undue stress on any political accommodations and social negotiations that have established peace (Pompe and Turkewitz 2022).

Examples of sectoral approaches

Curbing Corruption provides a series on sectoral reforms and strategies. Tromme and Pyman (2021), for example, identify the main types of corruption in the fisheries sector. The risks they identify are fraud, non-observance of standards, forced labour, organised crime and money laundering, and petty corruption. After identifying these specific risks, the authors then form an overall strategy to mitigating corruption, including the relevant legal instruments, policing, access to information on agreements and licensing, and coordinating efforts through programmes such as the Fisheries Industries Transparency Initiative (FITI) (Tromme and Pyman 2021).

The series provides further sectoral guidance on sectors such as construction, defence and military, education, health, higher education, land governance, local government and more.

Abdou, Basdevant, David-Barrett and Fazekas (2022) developed a methodology to assess corruption risks in the public procurement sector. Seven red flags are described to assess whether there are corruption risks in the sector (such as single bidder contracts, non-open disclosures, etc.). This sector-specific risk assessment helps policymakers to identify corruption risks and the subsequent costs that may be associated with these. It also provides sector-specific anti-corruption measures, such as e-procurement, to increase transparency and reduce corruption in the sector.

Recommended reading

Aly Abdou, Olivier Basdevant, Elizabeth David-Barrett and Mihály Fazekas: Assessing vulnerabilities to corruption in public procurement and their price impact.

Mark Pyman: Sector by sector reforms and strategies.

Pallavi Roy, Mushtaq Khan and Agata Slota: A new approach to anti-corruption.

Sebastiaan Pompe and Joel Turkewitz: Addressing corruption in fragile country settings.

Innovations in the measurement of corruption

Corruption measurement tools are important when designing anti-corruption interventions as they provide data to identify corruption hotspots and specific risks, as well as measure any apparent changes in the level of corruption over time. A range of corruption measurement tools rely on perceptions based data, such as Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, which was launched in 1995. As an example, the CPI relies on data sources provided by experts and businesspeople on corruption in the public sector (Transparency International 2022).

However, scholars have become sceptical of global-level comparative measurements of corruption, predominantly because of their perceptions-based data and their non-actionability from a policy perspective. As Fisman and Golden (2017: 34) note, “perceptions-based surveys are also more vulnerable to misperceptions resulting from, say, a crackdown that puts bribery in the headlines, even while actual corruption may be on the decline”. That is, they may not be an accurate reflection of real-world corruption levels.

Ang (2020) additionally points out that corruption indices not only fail to distinguish different types of corruption, they also tend to focus predominantly on bribery, embezzlement and illicit enrichment rather than influence peddling or abuse of functions (see legalised corruption earlier).

Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadašov (2016) summarise the key concerns regarding aggregate perception indicators as the lack of validity of underlying theoretical concepts about what constitutes corruption, the lagging nature of indicators and the non-actionable nature of aggregated data points (Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadašov 2016: 5).

To counter these challenges, ERCAS developed a Corruption Risk Forecast which is composed of three indexes. The Index of Public Integrity assesses the public resources spent on public transparency through online services, budget transparency and others. Their Transparency Index measures how much public information governments offer to their citizens based on the availability of data online. Finally, their Corruption Risk Forecast, provides potential future corruption risks based on press freedom, judicial independence and other variables pertinent to the control of corruption (Corruption Risk n.d.).

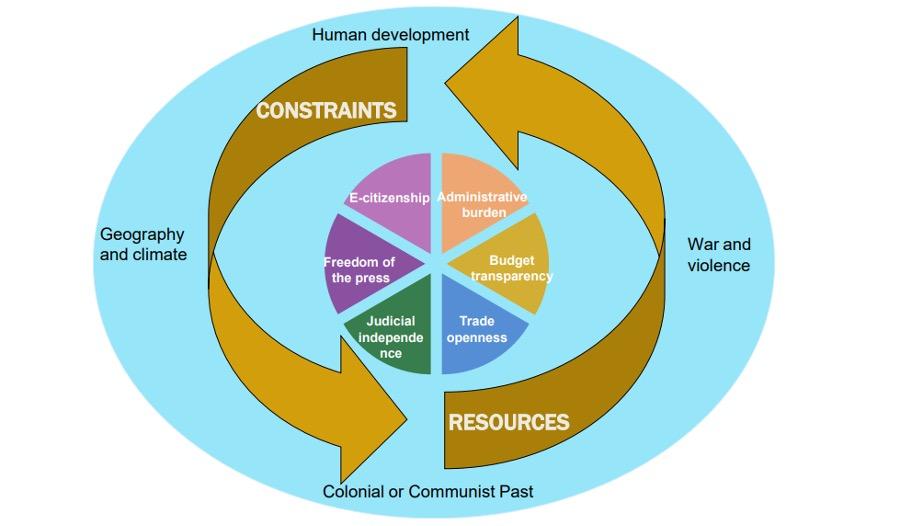

Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadašov (2016) present the rationale behind their measurement of the control of corruption in the Index of Public Integrity. They describe how the theory of governance (when defined as the set of formal and informal institutions determining who gets what in each context) allows for a more specific and objective measurement of the control of corruption (Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadašov 2016). A state’s degree of corruption is therefore an equilibrium between its collective resources (material and opportunities arising from power) and constraints (societal constraints limiting power) (Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadašov 2016: 13). They disaggregate resources and constraints by several factors which interact and use these indicators to measure the control of corruption.

Figure 6: Structural and policy determinants of the control of corruption

Source: Mungiu-Pippidi and Dadašov 2016: 14. Measuring Control of Corruption by a New Index of Public Integrity.

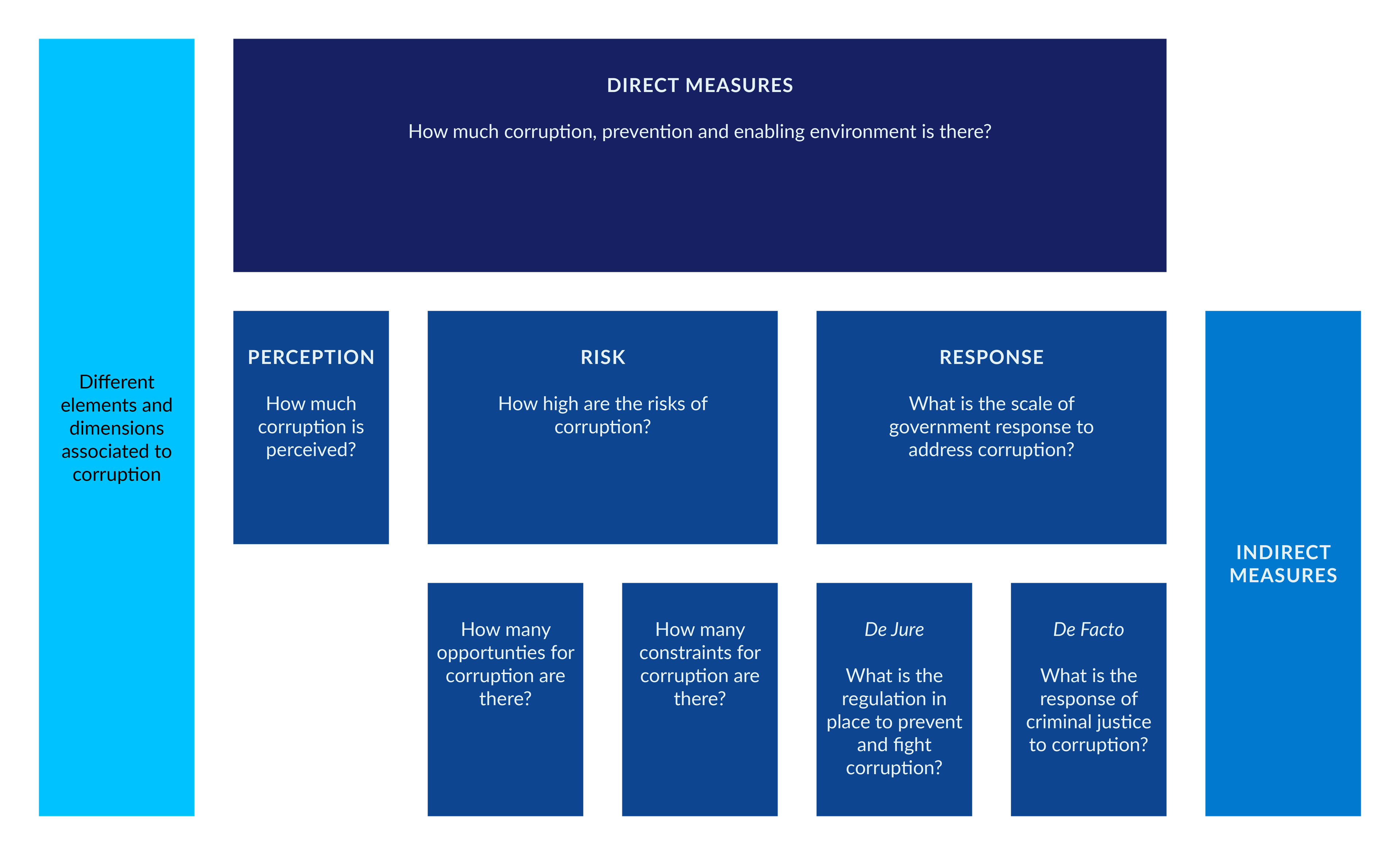

As another example of a novel attempt to measure corruption, the UNODC’s recent conceptual statistical framework to measure corruption provides a framework that combines national administrative data and perceptions of corruption. It measures a wide range of types of corruption, from bribery of public officials to public procurement as well as conditions believed to deter and sanction corruption, such as the protection of reporting persons (UNODC 2023: 6). It measures corruption in a matrix format through direct measures (such as bribery) and indirect measures (such as perception indicators, which acknowledge the elusive nature of corruption) (UNODC 2023: 7):

Figure 7: The dimensions of the UNODC statistical framework to measure corruption.

Source: UNODC 2023: 10. Statistical framework to measure corruption.

The proxy challenge

Notably, the UNODC’s framework also appears to draw on insights gleaned from the so-called proxy challenge, given its inclusion of indirect measures. This challenge is what Johnsøn and Mason (2013) describe as the fact that the term “corruption” is considered a collective term for a range of different practices, and therefore all different types of corruption cannot be measured by one indicator (Johnsøn and Mason 2013). The specific problems identified by Johnsøn and Mason (2013) are:

- how to measure other types of corruption, such as patronage, conflict of interest, abuse of power and so on, that so far have defied direct measurement

- how to present a measure of overall corruption levels in a country, region, sector or organisation that is not biased towards the measurable types of corruption and that can illustrate trajectories of change (Johnsøn and Mason 2013: 1-2)

In response, many scholars are now using proxy indicators to measure corruption. A proxy indicator is a measure that stands in or represents another concept that cannot be directly measured. Johnsøn and Mason recommend that proxy indicators for corruption should not be static and should accurately reflect local conditions (2013: 3). They could include living standard indicators that are adapted to local contexts, payroll fraud in the civil service, the number of ghost workers in the civil service, or “system tests” which estimate politicians’ inclination to engage in corrupt behaviour during high-level processes (Johnsøn and Mason 2013: 3-4).

When measuring corruption risks in public procurement, Fazekas, Cingolani and Tóth (2016) propose the following indicators as proxies that could point to corruption and impropriety: a single bidder contract, whether the tender was officially published, if the procedure was open or not, the length of submission period, whether the call for tenders and/or contract was modified, any modifications to the contract value or not, and others (Fazekas, Cingolani and Tóth 2016: 12).

Mungiu-Pippidi (2016) similarly notes that the “new generation” indicators correlate themselves with observable factors (such as procurement) therefore showing that governance practices are observable in clear patterns (Mungiu-Pippidi 2016). These are objective, fact based, sensitive to change and actionable from a policy perspective (Mungiu-Pippidi 2016: 366).

Recommended reading

Alina Mungiu-Pippidi and Ramin Dadašov: Measuring control of corruption by a new index of public integrity.

Alina Mungiu-Pippidi: Corruption: Good governance powers innovation and For a new generation of objective indicators in governance and corruption studies.

Jesper Johnsøn and Phil Mason: The proxy challenge: Why bespoke proxy indicators can help solve the anti-corruption measurement problem.

Mihály Fazeka, Luciana Cingolani, Bench Tóth: A comprehensive review of objective corruption proxies in public procurement: Risky actors, transactions, and vehicles of rent extraction.

Nicholas Charron. Measuring the unmeasurable? Taking stock of QoG measures.

UNODC: Statistical framework to measure corruption.

Insights from behavioural economics

Behavioural economics seeks to gain insights through psychology and other social sciences to understand individuals’ economic decision-making. While this field of study has been around for several decades, the insights it offers into human behaviour have only started being applied in the anti-corruption field relatively recently.

Behavioural economics views corruption as a complex phenomenon, driven by individual and social dynamics (Muramatsu and Bianchi 2021). This means that individuals engage in corruption due to social norms and what is collectively understood in a society to be permitted in the unwritten rules of behaviour (Jackson and Köbis 2018). The threat of social sanctions for social norm violations creates multiple pressures and can in fact sustain corrupt practices (Jackson and Köbis 2018). This means that even if an individual privately disagrees with a corrupt act, they will still comply with it if they perceive it to be a social norm.

Baez Camargo and Passas (2017) look at the lack of progress in the reduction of corrupt activities around the world to rethink the way anti-corruption approaches are formulated. They delve into context specific factors that account for this, particularly in Tanzania, Uganda and Rwanda, where petty corruption is widespread. Their findings point towards social norms fuelling and perpetuating positive attitudes towards corruption (Baez Camargo and Passas 2017 b: 12). For example, in Uganda and Tanzania, respondents agree that bribing should not be “excessive” or extorted but should be understood in “terms of a broader social contexts in which individuals share a common understanding of each other’s circumstances” (Baez Camargo and Passas 2017 b: 12).

Baez-Camargo and Ledeneva (2017) challenge the prevalent anti-corruption approaches through discussion of the failures of anti-corruption reforms and normative corruption rhetoric in Mexico, Russia and Tanzania. They find that simplistic binary understandings of corrupt/non-corrupt, good/bad, ethical/non-ethical are restrictive and can in fact be detrimental to efforts to curb undesirable behaviour (Baez-Camargo and Ledeneva 2017).

Feldman (2017) argues that anti-corruption interventions must go beyond ethical codes and financial incentives to prioritise preventive interventions based on behavioural ethics research. Feldman (2017: 93) instead proposed “ethical nudges”, such as affixing one’s signature to the beginning of a documents rather to the end, may change people’s behaviour when reminded of their moral responsibility at the moment of decision-making.

Hoffmann (2021) developed an interactive toolkit which explains how and why widespread corrupt practices are motivated by social beliefs and expectations and the influence society has on the type of corruption individuals engage in. For example, in cases of bribery in the education sector, pass-mark bribery is common (Hoffmann 2021). While most parents think that pass-mark bribery is wrong, they mistakenly think that others approve of it, so this form of bribery is sustained through these pre-existing beliefs held by parents (Hoffman 2021). In cases of embezzlement, social expectations associated with membership of a religious community can increase in-group favouritism and providing benefits to one’s religious community actually increases the social acceptability of embezzlement behaviour (Hoffman 2021). Therefore, Hoffman (2021) recommends interventions such as faith-based campaigns to strengthen democratic rights and civic engagement in these contexts.

Anti-corruption messaging

Baez Camargo (2017) notes in a policy brief that beliefs that corruption is a normal state of affairs and low expectations about the quality of public services lead to a society collectively legitimising corrupt actions. To counter this, she argues, information is key to educate the population on budget allocations to schools and health facilities, and what should be expected from these services (Baez Camargo 2017).

Public information campaigns have long been a component of anti-corruption measures. These aim to educate the general public on the forms of corruption, where to report corruption and why corruption is damaging to society. Recent years, however, have seen some scepticism towards the use of anti-corruption messaging, particularly in lower income economies.

For example, Peiffer and Cheeseman (2023) examine how anti-corruption strategies aimed at raising awareness may be wasted or even do more harm than good. Their review found that in 10 of the 19 of studies on the impact of anti-corruption messages, the messages backfired to some extent (Peiffer and Cheeseman 2023: 6). In some, it actually increased the willingness to bribe. Peiffer and Cheeseman (2023) conclude that practitioners need to think hard about whether to conduct anti-corruption awareness raising campaigns, particularly in contexts where corruption is functional to overcome administrative blockages.

Peiffer and Walton (2022) surveyed 1,500 citizens in Papua New Guinea, testing the legal, moral and communal aspects of corruption and anti-corruption. They found that respondents were more likely to be favourable about reporting corruption when they were exposed to anti-corruption messages that emphasised the impacts on their local kinship groups. Messages stating that corruption is widespread, illegal or immoral did not affect their willingness to report. Therefore, locally adapted messaging has more impact on reducing corruption.

Elrich and Gans-Morse (2023) assess the effectiveness of norms-based information campaigns to reduce corruption, using messages on how people typically behave (descriptive norms) or ought to behave (injunctive norms). Their findings show that injunctive norms messaging consistently reduced bribe intentions, but the effects were relatively modest and of short duration. The combination of injunctive norms and descriptive norms can produce large and durable effects, although this is primarily among respondents who perceive information about corruption declining as credible. Only a minority is likely to believe such messaging, and the greatest impact is on younger citizens. Importantly, they find no evidence of “backfire” effects of anti-corruption messaging that had been noted in other studies.

They conclude that these findings suggest cause for optimism on anti-corruption messaging campaigns. Effective campaigns will require attention to the content, perceived credibility, location and timing of placement and targeting. For example, materials emphasising injunctive-norm messaging could be placed at strategic locations (such as entrances to public service agencies).

Recommended reading

Aaron Erlich and Jordan Gans-Morse: Can norm-based information campaigns reduce corruption?

Caryn Peiffer and Grant W Walton: Getting the (right) message across: How to encourage citizens to report corruption.

Caryn Peiffer and Nic Cheeseman:

Message misunderstood: Why raising awareness of corruption can backfire.

Claudia Baez Camargo and Alena Ledeneva: Where does informality stop and corruption begin? Informal governance and the public/private crossover in Mexico, Russia and Tanzania.

Claudia Baez Camargo and Nikos Passas: Hidden agendas, social norms and why we need to re-think anti-corruption.

David Jackson and Nils Köbis: Anti-corruption through a social norms lens.

Heather Marquette and Caryn Peiffer: Corruption and collective action and Collective action and systemic corruption.

Leena Koni Hoffmann: Diagnosing social behavioural dynamics of corruption.

Roberta Muramatsu and Ana Maria Bianchi: The big picture of corruption: Five lessons from behavioral economics.

Yuval Feldman: Using behavioral ethics to curb corruption.

The use of emerging technologies

In recent decades, the anti-corruption community has begun focusing more on the potential of technology to support better governance and accountability. Adam and Fazekas (2021) identify six types of ICT based anti-corruption interventions that have been noted in academic and policy literature:

- digital public services and e-government

- crowdsourcing platforms

- whistleblowing tools

- transparency portals and big data

- distributed ledger technology and blockchain

- artificial intelligence

E-government refers to the digitalisation of government services and includes transparency portals that enable public officials to provide information as open data as well as the digitalisation of public services such as obtaining drivers permits, applying for land titles, registering businesses, among many others (Kossow and Dykes 2018). De Sousa (2018) describes how technology can improve access to information, creating conditions for more effective corruption control. This can be achieved through the digitalisation of government, the computerisation of public services, online service platforms, introduction of performance evaluation services, among others.

Mobile applications such as “I paid a bribe” in India allow citizens to report the location and type of bribe requested and passes the information on to the relevant authorities (I Paid a Bribe n.d.). Crowdsourcing platforms and online anonymous whistleblowing platforms also allow citizens to report incidences of corruption easily and securely (Kossow and Dykes 2018).

Blockchain is a method for storing records, where data is linked in a chained structure that has verification mechanisms (Aarvik 2020). This technology is increasingly used by development and anti-corruption practitioners as it can prevent protect public registries from fraud and tampering (Aarvik 2020). For example, blockchain can be used to timestamp proof of registered land rights in an immutable, distributed ledger such as the blockchain or be used to securely collect biographic and biometric information for identity systems aimed at providing refugees with access to assistance (Aarvik 2020).

Artificial intelligence (AI) can be used to uncover or detect money laundering schemes, predict tax evasion or monitor and identify suspicious tenders or bids in public procurement (Aarvik 2019). Open data can make it easier for citizens and civil society to track government spending through algorithms identifying potential corruption indicators in datasets (Petheram and Asare 2018). These algorithms can also be harnessed to access the financial accounts of suspected individuals (Petheram and Asare 2018).

ICT can also have an awareness raising function, a reporting function, a compliance function and a risk management function. However, De Sousa (2018: 191) cautions that the benefits and costs of introducing ICT should be evaluated, as government openness is “neither an absolute value, nor desirable at all costs”. He stresses that although ICT will generally improve the quality of governance, context matters a great deal when designing and implementing these tools, and that “the introduction of ICT is a complement, not a substitute, for legal and institutional reforms” (De Sousa 2018: 198).

Indeed, the relationship between good governance and technology is complex. Mungiu-Pippidi (2015) points out that corruption itself may be a major inhibitor of technological innovation. Her thought piece argues that, in countries where advancement is not based on merit but favouritism (as more commonly seen in corrupt states), this results in lower quality research and innovation (Mungiu-Pippidi 2015).

Conversely, technology has also been considered a potential facilitator of corruption by some scholars. Top-down artificial intelligence anti-corruption tools may be used as efficient means to consolidate power and result in new corruption risks (Köbis, Starke and Rahwan 2022). Moreover, other risks include consolidation of power and undermining of elections by the rapid spread of “fake news” through automated bots, which can be used to influence voter behaviour and the outcome of elections (UNODC 2019).

Recommended reading

Alina Mungiu-Pippidi: Corruption: Good governance powers innovation.

André Petheram and Isak Nti Asare: From open data to artificial intelligence: The next frontier in anti-corruption.

Isabelle Adam and Mihály Fazekas: Are emerging technologies helping win the fight against corruption in developing countries?

Luís de Sousa: Open government and the use of ICT to reduce corruption risks

Niklas Kossow and Victoria Dykes: Embracing digitalisation: How to use ICT to strengthen anti-corruption.

Nils Köbis, Christopher Starke and Iyad Rahwan: The promise and perils of using artificial intelligence to fight corruption.

Per Aarvik: Artificial intelligence – a promising anti-corruption tool in development settings? and Blockchain as an anticorruption tool.

- The former Peruvian president, Alejandro Toledo, was accused of taking around US$35 million in bribes from Obrecht, a construction company, to win a public works contract to build a highway connecting Peru and Brazil (Collyns 2023).

- Marginalisation theory refers to the processes where certain groups are pushed to the “margins” of a society through denial of access to resources and power.