Conservation and corruption in Madagascar

Madagascar is widely recognised for its high concentration of endemic plant and animal species, as well as its broad diversity of ecosystems – from forests to wetlands, savannah to highlands, spiny deserts to mangroves and coral reefs. There are over 12,000 species of trees and other vascular plants, of which 96% are endemic to the island, 389 species of reptile (90% endemic) and 104 species of lemurs, all of which are endemic.888ea2bc2c3f Yet many of the habitats for these species are seriously threatened. For example, according to Global Forest Watch, in the last 20 years Madagascar has lost around 4.13 million hectares of tree cover,fcec473f9cde which is a decline of 24%. This has consequences for local ecosystems and biodiversity, but also for the ability of Malagasy forests to capture carbon.

The island’s diversity extends to its coastal areas. These regions are considered some of the most diversified in the Indian Ocean region,128cd5d21d17 ranging from mangroves to coral reefs, seagrass beds and coastal marshes, home to 752 species of fish, 28 species of marine mammals, and five species of sea turtles (all of which appear on the IUCN red list of threatened species9819784cc39b with the hawksbill turtle listed as critically endangered).

Threats to marine and terrestrial ecosystems are driven by several factors, including international demand for hardwoods and exotic animals tied to networks of corruption.adb1d82c9f0c Local natural resource use patterns such as harvesting firewood, artisanal mining, and unregistered fishing for sale and private/local consumption also threaten forests and seascapes. In many cases regulations and conservation programmes exist to manage and prevent over-extraction, and yet the figures above demonstrate limited success in preserving Madagascar’s forests and fisheries.

Corruption is one of the main challenges to the conservation of Madagascar’s natural resources.51582ea55fef Rooting conservation efforts in local communities through approaches such as community-based natural resource management (CBNRM) is viewed by conservation organisations as one way to address this corruption. Our research considers: (1) the ways in which conservation organisations tailor CBNRM activities to (explicitly or implicitly) combat, circumvent, or otherwise navigate corrupt systems and practices; (2) how local community members experience and evaluate these efforts; and (3) how associated outcomes are shaped by broader, multi-level dynamics.

Several challenges remain in engaging communities to manage and preserve threatened ecosystems. Many of these are related to how well conservation programmes reflect the needs and wishes of local communities and integrate those needs into the goals of programmes beyond the main conservation outcomes. Solutions can include compensating community members directly, substantially supporting the development of income-generating activities, and/or protecting communities from pressure or violence from vested interests that see corruption as a means to enable illicit resource extraction.

This U4 Issue presents evidence gathered through field-based research in communities surrounding protected areas in northern Madagascar where three different conversation organisations with CBNRM projects are working. The U4 Issue explores the logics, designs, perceptions, and effects of such projects in order to inform improved interventions aimed at combatting corruption, reducing associated illicit extraction of natural resources, and ameliorating conservation outcomes. The findings and policy implications contained in this U4 Issue continue the conversation begun in our previous publications: Enrolling the local: Community-based anti-corruption efforts and institutional capture and The unusual impacts of Covid: Reflections on the links between demand, extraction, conservation, and corruption, a note from the field.c01e267c4421

The goal of our research is to better understand the ways community-based conservation and anti-corruption activities address corruption to produce local natural resource management outcomes. The main research question framing the Targeting Natural Resource Corruption (TNRC) project was: What factors condition success and failure of anti-corruption interventions in renewable resource sectors?

Conservation threats and community engagement approaches in three case study areas

The primary results are drawn from relevant policy and practice documentation, broad and targeted literature reviews, and more than 238 field interviews with NGO staff, government officials, local authorities, project participants, and other local community members in the three case studies. These cases are the Makira-Masoala-Antongil Bay (MaMaBay) region, Andrafiamena-Andavakoera and Loky Manambato protected areas, and the Northern Highlands landscape and Northern Mozambique Channel seascape.

Map over field sites in Mozambique

All three cases are interventions designed to improve biodiversity conservation, promote alternative livelihood activities for protected area-proximate communities, and the secure local management and ownership of natural resources. The precise ways in which community management is exercised differs slightly in each case, but the main aim of prioritising local development with conservation goals remains constant. Prioritising local development can include allowing certain economic and livelihood activities in particular zones of the protected areas. All cases have a governance approach that involves shared management (gestion partagée), or co-management (co-gestion) between conservation NGOs, regional environment authorities, representatives from proximate municipalities (communes), and community (fokontany)-level management associations. These can be environmental protection committees (komity miaro ny tontolo iainana, or KMTs) or similar community-based organisations called communautés de base (COBAs) or vondron’olona ifotony (VOIs) to which management rights and responsibilities have been transferred. These interventions are supported by a bilateral foreign aid agency, a Malagasy NGO, Madagascar National Parks (MNP), and/or the national office of an international conservation NGO.

The MaMaBay, Adrafiamena-Andavakoera, and Loky Manambato interventions all target deforestation, though the causes in each case differ slightly. In the MaMaBay case – where a bilateral foreign aid agency is working in partnership with an international conservation NGO and MNP – deforestation is largely associated with illegal logging of precious hardwoods and expanding vanilla production.be98dc58d041 A recent boom in chainsaw availability and use has been of particular concern to conservation staff and other interested parties. The precious hardwoods in question (rosewood and palisander) and vanilla are lucrative commodities of strong interest to national and international elite actors, and have been linked to corrupt political–economic networks on the island and beyond.fbb77c686839 Also of great concern is deforestation linked to the expansion of agricultural fields for production of rice and other subsistence crops. Meanwhile, the primary threat to aquatic ecosystems is ongoing use of small-mesh fishnets (ramikaoko), as well as extraction of particular sea products which have a high consumer demand.

The main threats to Andrafiamena-Andavakoera and Loky Manambato – both overseen by a Malagasy NGO – are deforestation and landscape degradation linked to charcoal production, agricultural expansion, cattle grazing, and gold mining, as well as the hunting of local lemurs (eg Propithecus perrieri and Propithecus tattersalli) for consumption and sale. The challenges posed by gold mining – especially near the towns of Betsiaka and Daraina – and wildlife hunting have proved especially intractable, largely due to the involvement of corrupt elite networks in each of these sectors. The situation has become particularly fraught since the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has exacerbated local livelihood insecurity while also simultaneously prompting a spike in the global price of gold.

The third organisation included in our study is a different international conservation NGO that manages two priority areas in northern Madagascar: (1) the Northern Highlands landscape, which includes Marojejy National Park, Tsaratanana National Park, the Couloir Marojejy-Tsaratanana (COMATSA) New Protected Area, and Anjanaharibe Sud Special Reserve; and (2) the Northern Mozambique Channel seascape. As in the other cases, the primary threats to the first area include deforestation and landscape degradation chiefly driven by agricultural expansion, as well as by limited vanilla production and hardwood logging. For the second area, the greatest challenges to successful coastal conservation have been overexploitation by smallholder fishers and some commercial actors, compounded by jurisdictional conflicts between different government ministries and other stakeholders. Mangrove clearing for rice growing has also been a significant concern. This highlights an important distinction between this case and those of MaMaBay and Andrafiamena-Andavakoera/Loky Manambato: while cultivation and extraction of lucrative commodities (ie vanilla, hardwoods, marine products) do pose some marginal threat to these conservation areas, the main challenges faced by landscape managers are swidden (slash-and-burn agriculture) subsistence farming and overfishing.

Across the varied sites included in our study, nearly all individuals interviewed agreed that corruption (kolikoly) was a problem. However, there were significant variations in what each respondent meant by ‘corruption’, which elements or manifestations of corruption were emphasised, and how these phenomena were put into conversation with assessments of conservation, resource access, and power. We explore these divergences in the findings and analysis below. To protect the identity of all participants, including NGO staff, local communities, government officials, and international bilateral donor agencies, we have chosen to anonymise the case studies.

Findings and analysis

After reviewing the interview data collected by research team members in project-related sites across northern Madagascar, we have identified seven main challenges that affect the practice and success of community-based anti-corruption and conservation campaigns in the region.

- While most research participants agreed that corruption was a problem, there were marked differences in their understandings of ‘corruption’ – how it should be defined, and what suite of activities should be considered ‘corrupt’. This illustrates the ways in which ‘corruption’ as a concept and narrative is both contested and used by the different stakeholders that were interviewed as part of a discursive strategy to assign blame and advance competing claims.

- Poverty and inequality pervade these contexts and efforts. Local groups’ unfulfilled expectations regarding ‘development’ and material benefits from the presence of – and participation in – project activities strongly shapes their perceptions of conservation and what constitutes ‘corruption’.

- Community-level actors enrolled in conservation and anti-corruption efforts often lack sufficient power to accomplish programme goals relative to higher-level authorities or other involved groups. This has left them thoroughly discouraged. Struggles between local officials, representatives of different state agencies, members of the judiciary, and conservation staff have muddied questions of jurisdiction and enforcement. KMT, COBA, and VOI members charged with enforcing rules, punishing transgressors, and reporting incidents of corruption often feel powerless, as offenders are suddenly released by the local courts (tribunals) and return to such activities with apparent impunity.

- Notions of social harmony or solidarity (fihavanana) are central to local social relations in the cases we studied and can pose a dilemma for conservation efforts deemed to be harsh or rigid. It is unacceptable to expect local residents to enforce externally defined rules on neighbours they must continue to coexist with – especially when higher-level authorities and/or the judicial system decide to not uphold charges, prosecute offenders, or levy associated penalties.

- Community perceptions of conservation are shaped significantly by historical factors. Associations continue to be made between colonial and post-colonial practices of exclusion and eviction and modern conservation efforts. Even when conservation organisations adopt new, people-centred models, past conservation efforts – from the colonial era, or from earlier iterations of contemporary projects – can undermine these novel approaches.

- The fundamental nature of ‘participation’ in these cases continues to prioritise externally defined goals over local needs and desires. This undermines local ownership of efforts that are ostensibly ‘community-based’.

- Relatively novel efforts to collaborate with communities on commodity production through the creation of cooperatives and/or alternative value chains, such as the vanilla cooperatives, have earned conservation actors some praise from local community members and seem to hold some promise – but they also bring their own set of complications in terms of conservation and corruption.

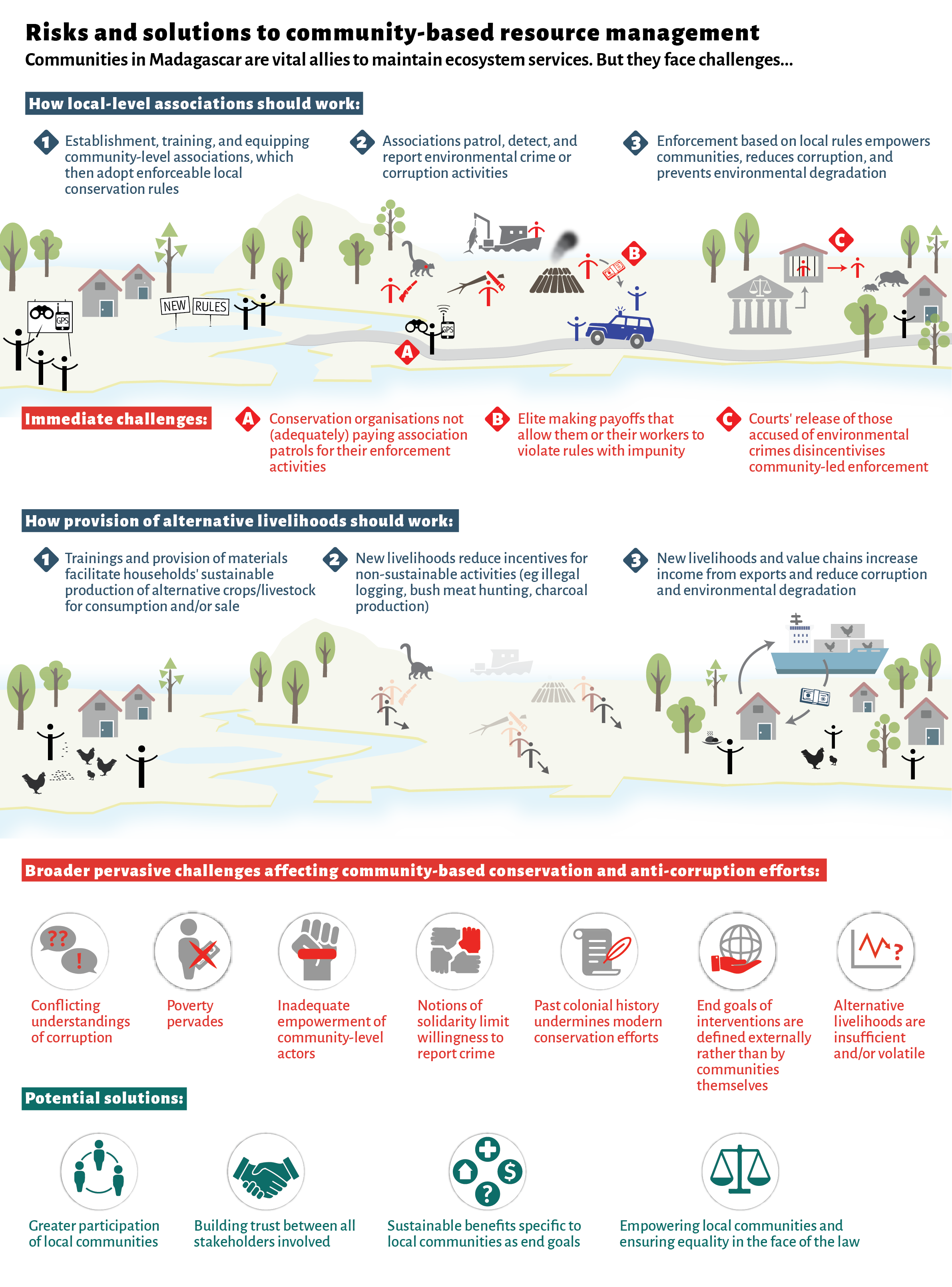

Risks and solutions to community-based resource management

For a better view download infographic as PDF.

‘Corruption’ as concept and discourse

Across research sites, nearly all individuals interviewed agreed that corruption (kolikoly) was a problem. What each respondent meant by ‘corruption’, or which elements or manifestations of corruption were emphasised, however, varied significantly. NGO staff tended to stress the complicity of local officials and representatives from state agencies in either encouraging transgressions or accepting payoffs for resource access, as well as local courts and judges (tribunal) who they said would accept bribes to suddenly release environmental criminals – or in some cases to detain innocent accusers. As one interviewee in the MaMaBay region put it:

‘The source of the corruption is…from our collaborators like the tribunal, the gendarmes, the forest administration… Whenever we detect infractions inside the protected area, we report them to the forest administration. Then, the forest administration with help of the OPJ [Officier de Police Judiciaire] and the gendarmes intervene, visiting the areas in question to see what’s really going on. If they find evidence of guilt, they bring the accused to the tribunal. Unfortunately, most of these efforts are eventually unsuccessful because the offenders are quickly released back into their communities. Wealthy offenders don’t even go to the prison; they just clandestinely pay some money to the tribunal and are freed. These are some of the difficulties that we are facing here that serve as bad examples to rest of the community.’

Another interviewee working with a Malagasy NGO explained how illicit networks targeting high-value resources are frequently the source of payments shaping officials’ behaviour.

‘We call it effet déclencheur – when wood extraction is happening, it means there are people buying it, there is a trade… When buyers demand the wood, poor extractors find all possible ways to get it. Buyers put pressure on everyone around, and this is where corruption appears. They “purchase” all of the authorities around; they give money to the chefs fokontany or other local officials to open the way to get wood. They buy the OPJ and the tribunal… [and] when those with the power to arrest people are corrupted, this becomes the defining problem… Natural resource conservation in Madagascar has become an environmental business, and this is the main cause of corruption.’

Some NGO staff also blamed local members of the community-based environmental protection committees (KMTs, COBAs, and VOIs) for engaging in ‘corruption’ via the ‘solicitation of unsanctioned fees’ from community members in exchange for cutting permits or other forms of access to resources in protected areas.

Local authorities and community members often corroborated these claims and expressed extreme consternation with the perceived unevenness of enforcement against well-connected offenders versus desperate smallholders. In doing so, however, they often insinuated that conservation actors themselves might also be complicit in the corruption. Several interviewees, for example, complained about the ongoing extractive operations of elites within the protected areas, and speculated that conservation organisations must be aware of this. Some respondents went as far as to implicate conservation organisations in corruption by allowing elite illicit activities to continue with impunity. Local fishers in the MaMaBay region, meanwhile, stated that wealthy outsiders pay people to enter their marine protected area where they are thought to engage in illegal harvesting of fish and other sea products. According to the fishers, these economic elites then use their wealth to corrupt the judicial system, winning immediate release for their accused employees and convincing authorities to arrest accusing community members instead. In this case, community members stated that conservation actors helped to secure the release of the innocent individuals.

In addition to these observations, though, local authorities and community members placed greater emphasis on other phenomena when asked about corruption. They raised a host of questions trying to make sense of pronounced differences between themselves and conservation actors in terms of wealth, resources, and power. For example, they asked: Why do conservation NGOs and projects have greater control over landscapes and resources than local communities do? Why is it that conservation organisations are well-funded, and staff well-compensated, whereas community members who are now expected to enforce conservation rules (eg as members of KMTs, COBAs, or VOIs) receive meagre or no pay for doing so? Why do conservation organisations have well-built and well-equipped offices whereas local villages have seen no infrastructural improvements financed by foreign donors? The answer to each of these questions given by respondents was ‘corruption’.

There were also more explicit accusations of wrongdoing by NGO staff in relation to training and per diems. As one local authority claimed:

‘I can say that there are some acts of corruption done by the NGOs here. For example, while they are on mission, they might leave their office to come to the community for what is supposed to be a ten-day training, but they compress the training into five days [and pocket the extra per diem meant for trainees]… [W]hen you look closely at the paper they ask you to sign before getting the per diem, you might find the exact number of days; they often do the training that is supposed to be for two days for only one day, then they just give us some money and tell us to eat at our homes.’

Community members reported that they are afraid to raise these issues because of the perceived power of conservation staff. While power imbalances are hardly unique to the dynamic between local residents and conservation NGOs – for example, the same can be said about local versus external actors across the development sector – the issues raised by community members are nevertheless important. Creating mechanisms that allow local communities a greater say in projects, and that offer systems for open and honest feedback is important in addressing these issues.

Local authorities and community members also discussed the uneven distribution of conservation project benefits as a form of corruption, often asking questions such as: Why do certain villages receive infrastructure improvements while ours does not? Why does the village that hosts the NGO’s headquarters and/or ecotourism venture have improved facilities and jobs on offer, but not ours? The answer respondents gave was, again, ‘corruption’. While it can be debated whether these decisions are the result of corrupt influence or the result of project management practicalities, the issue of inequality in the distribution of ‘benefits’ (tombontsoa) from conservation is a serious concern. It shows the importance of full transparency for all major and minor project decisions, and the need for a more equal distribution of benefits.

In other cases, local respondents acknowledged that conservation actors themselves might not be engaged in corrupt behaviour, but contended that they were well aware and tolerant of their collaborators’ corruption. For example, multiple interviewees complained that certain COBA leaders (who allegedly came to power after a fraudulent election) are corrupt, and that local NGO staff are aware of this corruption – but that agents choose to look the other way because of warm relations between the NGO and the powerful family who influence local leadership. Interviewees reported that bicycles and megaphones provided by the NGO, and meant for distribution to COBA members, disappeared after they were given to the COBA president. Fees collected from the sale of cutting permits haven’t properly added up. Interviewees also reported that monitoring and project follow-up by the NGO has been inadequate. Agents ride their motorcycles into town to the COBA president’s house, then leave without consulting or engaging with the broader local community – and reportedly accept the leaders’ corruption as the price of a local licence to operate.

Finally, some interviewees from local authorities and community members acknowledged that KMT, COBA, or VOI members – and local politicians – might issue ‘unsanctioned cutting permits’ and accept small fees for doing so. However, they considered this sort of ‘corruption’ categorically quite different from that of wealthy outsiders, law enforcement, and conservation actors themselves, and they see it as largely acceptable or, at least, understandable. This dynamic is explored further in the sections below.

Poverty and expectations of material benefits and development

Most interviewees confirmed the presence and problems of corruption. Interviewees also almost universally cited poverty as the main driver of corruption, and of environmental degradation generally. Our research team members were told that poverty is what leads people to cut wood for construction or sale, to use illicit small-mesh fishing nets (ramikaoko), to make charcoal in the forest, to hunt lemurs, and to engage in corrupt exchanges to secure access or evade punishments. In interviews, NGO staff recognised this dynamic, and explained that they have responded to such pressures with efforts to improve livelihoods through the encouragement of alternative income-generating activities. These measures have undoubtedly achieved some success (discussed below), and local authorities and community members expressed enthusiasm and appreciation for such activities. However, they more broadly viewed the material and development benefits brought by conservation actors as far too small for incentivising local enforcement compliance and compensating communities for lost access to local resources.

One of the most common issues raised by interviewees was the lack of adequate compensation for KMT, COBA, and VOI members. Again, conservation agents identified these local enforcement committees as the primary vehicles for combating environmental crime and associated corruption. Despite being tasked with the major responsibilities of managing access, conducting patrols, detecting and reporting infractions and associated corruption, and levying penalties and punishments, the committee members report receiving very low compensation. Most receive occasional per diem payments of roughly US$1.25–3.00 (based on 2021 exchange rates) for conducting joint patrols with conservation staff and law enforcement, or for participation in training. Some are also given a small lump sum of about US$9.00 every few months. To put these figures into context, the global poverty line782b96f2b444 was set in 2017 at US$2.15 per day. Across the board, this is viewed as utterly insufficient, as indicated by KMT, COBA, and VOI members working with each of the conservation projects included in the study:

‘Yes we have been trained – but the biggest challenge…is that we don’t feel motivated because our compensation is so low. Whenever we meet [with NGO staff], we always ask about increasing salaries to enhance the emotions we feel towards our work. We explain frequently that what we’re paid now is no help to weathering life’s challenges. We have families to feed. They increased our salaries once, from 30,000 Ariary [US$7.50] every three months to 36,000 Ariary [US$9.00]. …[O]ur responsibilities are significant, our work is hard, and it requires significant time – time that we usually spend on our everyday livelihood activities instead, because that’s what’s more important for survival… If we were paid better, we would have much greater motivation and dedication.’

‘…[Conservation will only succeed] if the patrollers and forest guards get paid, if it can be a main livelihood source for them. Otherwise, the protected area will be their business.’

‘I won’t tell [NGO staff] anything if I see people enter the protected area because I don’t get paid. This [reporting infractions] will also ruin my relationship with other local residents. This is why people are able to illicitly extract from the forest, because people know this is the case, and use it in their strategies.’

Many interviewees also cited inadequate salary payments to explain why KMT, COBA, or VOI members might accept unsanctioned fees in exchange for ‘looking the other way’ when illicit extraction occurs. As one KMT member explained:

‘The fact of not earning monthly wages makes me feel ashamed... One of my family members was seen illicitly cutting wood, and some charcoal-makers noticed and made a report to us. I directly intervened and gave them advance notice. I could have arrested them, but I have no money – not even a penny – and so instead I asked them to give me some rice, and in exchange I would let them quickly dispose of the wood and go free… When they were searched, the illicit wood was already gone. I recognise that this undermines our work, but what else can I do?’

When asked what an adequate salary might look like, KMT, COBA, and VOI members offered a figure of around 200,000 Ariary (approximately US$50) per month (as of 2021).

In one region, numerous VOI members expressed dissatisfaction with insufficient pay and promises of enhanced remuneration that were never kept. They also complained that the NGO had not provided adequate equipment, such as raincoats, shoes, tents, and uniforms. These materials are seen as essential for extended forest patrolling. VOI members also complained that responsibility for conducting monthly patrols has fallen disproportionately on them, while reporting that better-compensated NGO agents work on joint patrols for only three or fewer months of the year.

Also frequently raised was the lack of community infrastructure projects, and the insufficiency of alternative or sustainable livelihood projects to compensate for communities’ lost access to resources, which would reduce the incentives for illicit extraction. As several local authorities and community members expressed:

‘We don’t find any benefits from the existence of the national park, and I can also say that we have never received any infrastructures from the local NGOs. A month ago, the local community went on strike because they are getting impatient with the situation as the only thing these NGOs usually do is to put the people from here into prison.’

‘…[The] local community doesn’t benefit from those carbon credits in terms of local development or livelihood improvement; they should at least build some infrastructures such as dams or something else. Until now, we get nothing from them – but on the other hand, they try to increase the size of the protected area by moving their limits closer to the fields of the local community. This is the main problem of all the communes and fokontany around MaMaBay.’

‘…[The] local community members who live near the park should reap the benefits from conservation [through receiving] basic infrastructure hospitals, schools, dams, etc. It would also be easier for us to convince the local community to protect the natural resource if they find the tangible benefits from the conservation.’

Some local authorities and community members reported that conservation goals were damaged by conservation organisations’ unwillingness or inability to pay KMT, COBA, and VOI members living wages, and their lack of support for infrastructure or alternative livelihood projects sufficient to compensate for lost access to proximate resources. Also, given how obvious these issues are to local people, they reported that their absence or insufficiency was an indication that conservation organisations actually have ‘no interest’ in lifting people out of poverty or removing threats to protected areas. Rather, it was reported that conservation actors want protected areas to remain under threat, and community members to remain poor, because these conditions prevent conservation interventions from becoming obsolete. They also call this ‘corruption’.

Power imbalances and perceived impunity

Beyond feeling undercompensated and insufficiently supported, the local associations envisaged as first-line defenders against environmental crime and corruption also feel supremely powerless, for several reasons. KMT, COBA, and VOI members say that their legitimacy is undermined by other external authorities – the Forest Administration, Chef Cantonnement, Chef de Triage, and so on – who fail to cooperate with local actors and issue cutting or fishing permits, circumventing established procedure. External actors arrive with ‘authorisations’ from higher-level authorities in hand, and KMT, COBA, and VOI members become confused, intimidated, and generally feeling powerless to stop them. Meanwhile, local authorities are excluded from reporting and enforcement channels (eg chefs fokontany, mayors, and so on) – a measure ostensibly meant to insulate such processes from the perceived corruption of such officials. As a result, local authorities often feel insulted, and sometimes angrily respond by undermining conservation actors, KMTs, COBAs, and VOIs through encouraging local people to violate rules. This indicates the importance of building coalitions with reform-minded local officials for bringing about effective enforcement.

It is also important to note that local associations’ management rights and enforcement tools wholly rely on the approval of state and NGO collaborators, effectively giving these actors a veto over (or at least the ability to significantly hinder or delay) the sanctioning of KMT, COBA, and VOI activities. For example, members of multiple VOIs partnered in the Andapa region complained that management contract renewal processes have been slow and opaque, and that courts have failed to promptly recognise their dina (local codes that VOIs use to enforce conservation rules – explained further below).

Furthermore, as mentioned above, KMT, COBA, and VOI members feel exceedingly discouraged by the quick release of offenders by law enforcement and the courts. As one interviewee explained:

‘When KMT members catch someone and bring that person to the tribunal, those efforts are for nothing, because they will let that person go. Consequently, people develop negative attitudes. People stop caring that there are others breaking the rules because they don't want to go through the hassle of citing or arresting somebody anymore. The offender is viewed as untouchable because of corruption.’

Another interviewee in the MaMaBay region shared a story alluding to the issue above, where they and other local association members caught illegal divers in their marine protected area and brought the case to the tribunal. In response, the divers’ wealthy sponsors convinced law enforcement agents to arrest the association member – and they and the offenders were ultimately released simultaneously. ‘It was shocking,’ they said, ‘…and left us completely discouraged.’

Some NGO staff and local government authorities explained that courts and judges might simply be lenient on poor people with few alternative, legal livelihood options. Others interviewees (NGO staff and local communities) say the tribunals are corrupt and accept bribes in exchange for immediate releases. Judges themselves often justify the release of prisoners by saying that NGO agents and/or KMT, COBA, and VOI members have failed to properly ‘sensitise’ local people, to make them aware of the rules, and so imprisonment is unduly harsh given offenders’ professed ignorance. Regardless, the practice is taking a toll:

‘The role of the VOI is to denounce infractions and corruption, but the reality is many of the people who commit infractions have some sort of well-known, elite, or respected person behind his/her back to protect him/her; that’s why most of the people who commit infractions get released… VOIs are discouraged because no matter how hard they do their job no one goes to prison; the only reward they get is conflict with and a desire for vengeance from the local community.’

Social solidarity (fihavanana), crime, and interpretations of ‘corruption’

Another challenge faced by community-based conservation and anti-corruption approaches is that delegating enforcement to local actors can heighten intra-community tensions. Particularly salient in the Malagasy context is the institution of fihavanana, generally translated as ‘social solidarity’ or ‘social harmony’. Respondents from across the spectrum of roles included in our study – NGO staff, local authorities, KMT, COBA, and VOI members, other local community members (including those engaged in forms of extraction themselves) – repeatedly invoked fihavanana as a social pressure that constrains rule enforcement and the application of penalties. One regional official put it in these terms:

‘Normally, there should be zero tolerance for infractions, but in certain circumstances there must be tolerance – a kind of “moral” corruption, you might say – because of the shame associated with hurting your friends or family. This is a kind of “corruption” linked to social pressure… Generally, KMT members are very helpful, but sometimes they hide infractions because of fihavanana.’

KMT, COBA, VOI, and other community members explained further:

‘Yes, this is a weakness of the VOI. We usually can’t apply the dina strictly, especially when the case involves one of our relatives, and that kind of situation often creates conflict within the local community.’

‘The biggest challenge that we’re facing here (as VOI members) is on how to apply the dina, because our sons or brothers may commit infractions inside the protected areas.’

‘[KMT members] don’t know what to do because, according to the responsibilities of their job, they should enforce the rule – but they also are expected to look after society. That makes their task difficult. For example, my son is a KMT member, and it would be extremely difficult for him to arrest me.’

Beyond invocations of kinship and solidarity, KMT, COBA, and VOI members frequently expressed reservations regarding rule enforcement based on fears of creating intra-community conflict more broadly, and of making themselves targets for vengeance and recriminations. These fears are exacerbated by the tendency for law enforcement and judges to quickly (and often inexplicably) release offenders. A neighbour you arrest for illicit cutting or burning might be back next door the following day – now harbouring deep animosity towards you. As KMT, COBA, and VOI members elaborated:

‘The collaboration between us [and the forest service] is not really good. We live here permanently, and so we know or see what’s going on here almost always in terms of infractions. When we report these things, though, little action is taken [or offenders are quickly released]… That makes our work difficult because it creates conflict among us in the community – but they [forest authorities or other officials] hide behind our backs, and we take the blame.’

‘The main challenge we have? Fear of being beaten up! …[Our] social relationships are damaged due to our conservation efforts. And it’s difficult to take on this job because everyone in this community depends on access to natural resources to live! … [W]e do not have the means to defend ourselves… [and] authorities like ANGAP [Madagascar National Parks or MNP] do nothing to help us.’

‘…[S]ome people ask [for] an authorisation to cut one tree, for instance, but maybe they cut four trees instead. It’s very hard because if we don’t send a report to the forest administration, we feel like we aren’t doing our jobs correctly – but if we do send the report, local community members might exact revenge. So, it’s very difficult to apply the dina while avoiding conflict or vengeful responses from the local community.’

Conservation organisations have tried to address this conundrum by creating anonymous reporting channels, and by training community members in techniques of public denunciation. One project stated that the number of reports submitted has increased following implementation of these measures. However, community members interviewed remained strongly discouraged, and still expressed strong scepticism towards reporting. They again pointed out that offenders are quickly released and said that, even if anonymity is retained (which isn’t guaranteed, as word inevitably travels and folks might know who saw them doing what), it still disrupts fihavanana, induces intra-community conflict, and puts KMT, COBA, or VOI members at risk – all for little or no compensation.

The weight of history and enduring impressions

Another challenge facing contemporary conservation and anti-corruption activities is that, despite current community-centred approaches, these efforts are often being undertaken in contexts that were much more exclusionary in the past. As a result, community members retain deeply rooted antipathy and distrust towards conservation actors and their state allies. For example, in one town on the borders of Andrafiamena-Andavakoera, local residents connect today’s protected area with memories of French colonial enclosures of forests and others landscapes rich in resources. They feel that the French wanted to preserve this natural wealth for themselves, as do the Malagasy state and its NGO partners now – hence the establishment of a restricted protected area.

More recent history also weighs heavy. Around one protected area we studied, most local authorities offered positive assessments of the present NGO’s current conservation and community development efforts, but also conceded that many local people strongly resent the organisation because of its past approaches. When the NGO first took over management responsibilities, community members felt that the organisation pursued a strategy of eviction and exclusion to force gold miners and others out of the protected area. As one local official explained:

‘…[T]here was time when no outside organisations controlled this area, and then [the NGO] and government representatives came in and chased people living around here [out of the protected area] without initiating any kind of conversation with the local community first. The mission was followed by arrests – and I was among those arrested. Most young people ran away into the forest, while old people stayed here with the kids. That was an unforgettable event for community members here.’

Another community member said that the NGO had won the consent of the local council of elders (ray aman-dreny) in establishing the protected area by promising to prioritise local people – especially local educated youth – in employment decisions. But now the ray aman-dreny feel as though the organisation failed to honour its word, as almost none of the protected area staff are from the local community.

In another region, a local authority said that community members distrust the present NGO because a prior director acted like a dictator and allegedly sold a small island off the coast to a foreigner. A local community member also recounted a case of one NGO worker abusing their power for personal gain: after this staff member was fired by the organisation, the person pivoted from being a strict and harsh enforcer of rules to engaging in unrelenting illicit extraction himself using the materials originally confiscated from others. Though they were no longer employed by the NGO, the person’s actions left a strong (and negative) impression on many local residents.

Other conservation projects included in the study suffered from similar historical associations and community impressions. In the MaMaBay region, a particular issue was the moving and remarking of park boundaries in 2005.700c1fc29e07 This resulted in some community members’ fields being allocated inside the protected area, and otherwise greatly constricted the availability of land. It also left local authorities and community members feeling precarious and under threat. One local official explained:

‘The biggest challenge [to conservation] is that the borders of the park were moved closer to locals’ fields. It used to be further from our lands, but now it is too close, and we don’t have any more space to use. This is the primary complaint of the local community…’

The same point was reiterated many times and was often used as an explanation for why locals feel as though they have inadequate land for rice and vanilla cultivation – and why they subsequently clear or enter the protected area’s forests for cultivation. The park’s boundary reallocation was also offered as evidence of ‘corruption’. According to respondents, some individuals who directed payoffs to conservation actors were able to influence the drawing of the borders to exclude their fields. Others said that NGO staff or environmental authorities have used the altered boundaries to extract unsanctioned fees from community members who unluckily found their fields within the new borders, or from the especially vulnerable who lack adequate land and so are forced to enter the protected area.

Local community members also see the long history of interventions in the region, and their perceived lack of success, as evidence of conservation actors’ ‘corruption’. Many respondents remarked on how obvious it seems that conservation actors do not want infractions to stop or local people’s livelihoods to improve. When asked what local conservation NGOs’ goals really are, one fisher who uses the illicit small-mesh net (ramikaoko), replied:

‘I don’t really know that they want to do! I think this is like a business for them, because I think they act as though they are very strict when they are soliciting money from abroad, but once they have the money, they seem to let up [on enforcement]. This situation has repeated over and over for a very long time. We [ramikaoko users] have been persecuted by these NGOs for ten years now, but here we are still doing the same thing. We have been dragged in front of the local tribunal for judgement three times, but they often tell us to resolve the problem ourselves, which makes me wonder: what kind of law is actually being applied? …[They] seized my materials once, but I threatened them once the police had left and was able to get them back…I tried to stop doing this activity because I don’t want to spend the rest of [my days] in prison; I was afraid I might kill someone because they harass us constantly, and sometimes I can’t manage my emotions.’

In concluding the interview with our research team, the same respondent offered this final plea:

‘…If they [the foreign researchers you’re working with] want to support or create a new project, I beg them not to work with these same conservation NGOs that have been here for so long – because they have used this situation as a business.’

Reconsidering ‘participation’

Across our case studies and sites, without exception, interviewees endorsed the importance of community participation in conservation and anti-corruption efforts. Many expressed it in terms similar to those offered by one respondent living south of Andrafiamena-Andavakoera:

‘Yes, it is very important involve the local community in environment conservation, because it is only them who will protect the forest as they care for their own house or clothing.’

Local authorities and community members often accept many of the propositions underlying the push for community-based conservation and anti-corruption activities. However, as the findings in the preceding sections demonstrate, many factors complicate and undermine the projects’ efforts. Underlying these dilemmas is a quite basic but incredibly difficult further issue: the nature of ‘participation’ itself – or, more specifically, who, when, where and how participation happens.

Consider again the experience of KMT, COBA, and VOI members. Generally speaking, the rules that these members are meant to enforce are not of their own making; nor are they the product of community consensus. Rather, they are largely dictated by national environmental law, by particularities associated with the categorisation of the protected area in question, and by ‘best practices’ or ecological imperatives determined by the managing project or organisation staff. Around Andrafiamena-Andavakoera, KMT members referred to the protected area as ‘belonging’ to the operating NGO. One KMT president confessed to having little concept of what the NGO expected, other than detecting and reporting infractions – but not arresting anyone, which the president said was expressly forbidden by the NGO. The KMT had no sense of why various restrictions had been put in place, what the overall management vision for the region might be, or what punishments might be meted out to offenders. Residents in the village hosting the NGO’s local headquarters said the NGO had brought great benefits to the community, and that deforestation had dramatically decreased. However, the president also admitted that many residents of other proximate communities strongly disliked the NGO, felt excluded, feared the organisation, and often continued to find ways to engage in illicit extraction.

In the MaMaBay region, local VOI members often talked about difficulties with dina – the codes they were meant to enforce. Dina are generally considered part of the corpus of so-called ‘customary law’ in Madagascar but can also be officialised by the state as part of CBNRM projects under the 1996 Gelose law, which provided a legal framework to integrate rural people into natural resource and forest management. Traditionally, dina have been generated and enforced by communities themselves, and so often retained an inherent legitimacy and flexibility tied to social embeddedness. However, development of the many dina was instigated and shaped by conservation actors, in consultation with communities..1cd3ea0cc60c In assessing these dina, many KMT, COBA, and VOI members said that enumerated provisions clash with local norms, are exceedingly rigid, and would severely harm fihavanana (social solidarity norms) if strictly enforced (see the relevant quotations above on this topic). Building on earlier discussions, members also saw little point in enforcing strict rules (especially those dictated by outsiders) that would cause intra-community conflict, when they saw that higher-level authorities engage in corruption and release offenders without consequence. As one fokontany president explained:

‘These NGOs have to consult and discuss with the local community regarding things they should or shouldn’t do inside the protected area… [Regarding] the pursuit of those committing infractions, the only tool that we use here is the dina. We always apply what is written without exception, but the problem is that, when offenders are brought to the forest administration or the tribunal, most of them are released without punishment – and we then become their victims!’

One VOI president in the region also complained that conservation staff refused to print and distribute copies of the dina, making enforcement practically impossible. Other KMT, COBA, and VOI members saw value in their dina, but complained that wealthy people and well-connected migrants flouted the rules, that higher-level authorities failed to uphold associated penalties, and, in some cases, that dina shaped by heavy community involvement had been repeatedly rejected for officialisation by tribunals due to often unspecified reasons.

As mentioned above, VOI members in the Andapa region reported that inexplicable and ongoing delays in the approval of dina have undermined their activities. They also expressed consternation over the slowness and opacity surrounding the renewal of their management contracts. To support the contention that some NGOs lack coherent strategies for making conservation efforts work, one VOI leader cited the lack of financial compensation for association members, the paucity of support for more substantial development projects, and ongoing conflicts over protected area boundaries.

The ostensibly ‘community-based’ models being implemented often involve prioritising goals that are set elsewhere. These models are severely restricted by national legislation, and are undermined by higher-level corruption that leaves local authorities feeling powerless. Local ‘participation’ is meaningless if community members aren’t involved in setting the agenda and writing the rules. Also, the local community must be able to hold transgressors accountable; this should not be undermined by a corrupt judiciary or fragmented authority across sprawling conservation bureaucracies.

The promises and perils of ‘alternative livelihoods’

Expecting uncompensated, under-supported KMT, COBA, and VOI members (and other local actors) to fight corruption and advance conservation amidst such contexts is unrealistic – especially given the abiding reliance of proximate populations on extraction and cultivation for basic subsistence. To address this, each of the conservation interventions in this study sought to support ‘alternatives’ to extraction and cultivation – for example, offering training in growing techniques or animal husbandry, and giving community members saplings (eg coffee, cloves, cacao, fruit trees) or seeds or animals (eg chickens, ducks, pigs, or fish for pisciculture). Local leaders and community participants were generally appreciative of these programmes, but also assessed them as largely insufficient. One mayor, recounting an experience at a regional conservation meeting, elaborated:

‘…[O]ne of the representatives from the NGO explained that they provided chickens [to community members], but when they went back home, those who had received them ate their chickens… [W]hen I stood up to speak, I responded that farmers adopt new crops or techniques after seeing others succeed in doing so. OK, so you gave away some chickens – but how about feeding and building coops for these chickens? So, I suggested that they should come stay in the community and raise their own chickens, because if local residents saw them do that, and saw that it was good, many people would then follow their example.’

Another local mayor offered another critical assessment:

‘[Conservation actors’] activities are only really interested in the conservation of protected area. If they bring some sort of support to the community, they don’t consult the local community but only do what is good or convenient for them. For example, sometimes they give chickens to the local community. These kinds of support don’t benefit the whole community, but only five people among a population of 600 or 1,000. What they really need to provide is infrastructure that benefits the majority of the local community – things like dams, schools, and bridges. These are the things that they really need here. For me, chickens are not the alternative that will stop local people from hunting wild animals…’

An issue that often came up in these conversations involved community members’ strong interest in the multiple lucrative commodity sectors that northern Madagascar hosts,3bf4d7e71c25 including vanilla and gold. Staff from each of the conservation initiatives included in the study explained that provision of ‘alternatives’ such as chickens or vegetables were frequently framed as sources of income to be drawn on during low points in commodity cycles – when gold was scarce, or vanilla wasn’t ready to be picked, or global prices had crashed. Local authorities and community members understood this logic, but felt as though the scale of these projects was wholly mismatched to the kind of destitution and desperation that can come with a collapse in vanilla prices (something the region is dealing with in 2023).

More recent efforts, however, have sought to engage more directly with commodity production processes. For example, one NGO has created a partnership with a social enterprise now active across ten regions of Madagascar. This enterprise works with four producer federations to source and sell vanilla, nuts, spice, grains, cereals, and fruits to the domestic and international markets. Around Loky Manambato and Andrafiamena-Andavakoera, local authorities and community members discussed how the social enterprise promotes vanilla and cashew cultivation. NGO staff reported working with two vanilla growers’ associations comprised of 400 members from around Loky Manambato. Respondents in Daraina and Betsiaka (two major gold-mining regions) conflated the social enterprise and the conservation NGO, and saw them as overlapping entities interested in the possibilities of gold commerce.

Despite broad agreement with the notion of offering heightened support to vanilla growers, farmers, and miners, many respondents were quite critical of the social enterprise, linking it with a host of problems. Two of the most consistent critiques were that the NGO that instigated the enterprise had diverted its focus away from community conservation as the enterprise grew, and that certain vanilla growers exploited their relationship with the enterprise to expand production into places within and surrounding protected areas that are otherwise off-limits to community members. NGO interest in forming gold miners’ associations was likewise seen as driven by commercial interest. This was especially derided by miners who feel as though the NGO has unfairly persecuted them while going easier on farmers (who the miners claim are the real deforesters). As interviewees in the region explained:

‘There was a gold miners’ association created by [the local NGO]. They paid all the fees for establishing the association and for mining activities. But I could see that, in return, [the NGO] wanted to buy gold from the association. The existence of [the social enterprise] has changed the objective of [the NGO]; they no longer focus on protecting the environment but rather on collecting varieties of products like cashew, gold, vanilla. Anyway, we could end up benefitting from the gold miners’ association created by [the NGO]. For example, we might be able to buy rice collectively at a more reasonable price. But ultimately I’m convinced that their prime objective is to collect the products around.’

‘[We must evict] the people who have been directed by [the social enterprise] to plant vanilla within the forests because that is their excuse; everyone we caught in the forest said they work with [the social enterprise]... Most of [the social enterprise] workers plant vanilla in the forests, and that cannot be denied. People should not be staying in the heart of the forest. They stay there because they want to exploit resources from there – maybe animal, wood, or planting vanilla.’

In the MaMaBay region, vanilla cooperatives have also been established. Cooperative members felt that the programme has brought them a host of benefits: training in how to cultivate and cure organic vanilla and combat recent pest infestations; connections with buyers who offer bonuses (of around 10%) and zero-interest loans to cooperative members (to be repaid in vanilla); and small grants for things such as tree nurseries or animal husbandry projects. While generally expressing satisfaction with the efforts thus far, participants’ enthusiasm was measured. As one cooperative member explained:

‘On the one hand, what [the project] has done is helpful – but on the other hand, it’s not yet really what we’re hoping for. They have done a lot of work and spent a lot of money to create these cooperatives – but what we’re looking for is faithful partners from abroad that can buy our product every year at a good price without any mediation of the local buyers or even the local government. If we have that kind of collaboration, all the problems that I mentioned above [heightened extraction from and/or cultivation within the protected area] will disappear automatically.’

What cooperative members are hoping for is a reliable buyer and consistently high vanilla price, things that would untether growers from the extreme booms and busts the sector has seen over the past several decades. Such developments are, of course, far beyond what these conservation actors could deliver. Promoting the expansion of community members’ engagement in commodity production in sectors subject to volatile price shifts carries inherent dangers. Conservation actors are admittedly responding to grounded realities and community members’ demands in supporting such activities, but they should be careful not to overpromise.

Conclusion

There is near-universal agreement among all actors involved that community-based approaches are essential to the success of conservation and anti-corruption efforts. However, there are disagreements over what conservation rules are appropriate, and very different perceptions in what constitutes ‘corruption’.

Community participants enrolled and placed on the front lines of conservation enforcement and anti-corruption activities (such as KMT, COBA, and VOI members) feel undercompensated, insufficiently supported, powerless, and vulnerable to intra-community conflict, vengeful actions, and recriminations. As a result, they are less likely to undertake work combatting illicit extraction or other environmental crime and are more likely to accept unsanctioned access fees themselves. Our findings suggest more broadly that the incentives paid to KMT, COBA, and VOI members are simply too small to promote the intended behaviours. The circumstances perpetuate negative perceptions of conservation actors, and allow a culture to persist where corrupt – and environmentally damaging – acts are tolerated.

Furthermore, antipathy towards conservation actors, and disconnects between local priorities and externally set conservation goals continue to undermine the intended effects of community ‘participation’.

Conservation actors’ efforts to promote alternatives to illicit cultivation and extraction (and the ‘corrupt’ mechanisms that allow such activities) carry both promise and peril. They respond to certain local demands but do so in ways that risk overpromising stable and sufficient livelihood benefits while further exposing smallholder producers to the vagaries of commodity price volatility. The emphasis on commodity production has also added confusion over conservation actors’ intentions. This is especially the case when community members see areas that are off-limits for most forms of smallholder cultivation or extraction suddenly being made available for lucrative export crops – which conservation actors can financially benefit from.

Recommendations

From our Madagascar research findings, we have identified a number of recommendations for improving current practice. We believe that conservation actors could achieve better conservation and anti-corruption outcomes if they were to take these important steps. While many of the following recommendations have likely been articulated previously, we recognise serious gaps between their enunciation and active implementation. Genuine implementation for certain of these objectives will likely require systematic degrees of reorganisation and reprioritisation in the working practices of conservation organisations, as well as harnessing well-established lessons in community engagement approaches found in other sectors.

Participation

- NGOs and other conservation organisations should constantly renew efforts to solicit the opinions of local communities regarding their understandings of corruption. This should not involve standard training on corruption or ‘sensitisation’ but should use participatory approaches that empower individuals to state their views to ensure that their ideas are heard by all stakeholders and integrated into programme design. Consider Arnstein’s ladder of participation56d8a47f362e when developing these elements.

- NGOs need to clearly define who is a participant and reconsider when in the project cycle to bring local communities into their activities. NGOs should enrol participation prior to setting any project goals and outcomes.

- Conservation goals should be set locally using holistic and participatory approaches that favour partnership, delegated power, and citizen control. This may require NGOs to relinquish some degree of power and authority to local communities, in particular to disadvantaged groups and socially/economically marginalised community members. NGOs should support empowerment of local state structures to be effective, representative, transparent, and accountable.

- Conservation goals should be embedded in broader development goals around poverty alleviation and creating sustainable livelihood opportunities that reduce reliance on extractive practices. A priority should be to work with communities to identify broader social and developmental goals.

Building trust

- Conservation actors should analyse the social dynamics in each community to understand relations of power and social relationships that may prevent the reporting of corruption and reduce trust between local community members, NGOs, state actors, and other stakeholders. This type of analysis should be done at all stages of the project cycle: prior to start-up, midterm, and post-project. Qualified social scientists should be considered for this analysis to bridge the gap between biophysical-scientific competence and social-scientific competence.

- Conservation organisations should assess their own internal social dynamics, as well as their relationships with state and local institutions, and other political stakeholders to understand how community members’ perceptions of power inequities and collusion may also erode trust.

- Conservation organisations should develop transparent budgeting processes with local communities to clearly communicate the amounts being invested into conservation and development work in a given community (with care taken to avoid the inappropriate disclosure of personal information). Local community members engaged in project activities – especially those that may put them in danger or cause potential recriminations – should be properly compensated.

- Bottom-up accountability mechanisms need to be developed so that local residents can provide information of misused funds and other discrepancies in conservation organisations’ budgets, expenditures, and practices. Such mechanisms need to protect those providing information from retaliation by other stakeholders, and should be built in ways that support fihavanana rather than eroding it.

- Despite fears of corruption among local officials, it is important to build strong and accountable local state institutions. Support should be given to collaborations that include local communities, reform-minded local officials, law enforcement bodies, and conservation actors.

- To protect local people who report corruption, conservation actors should create and maintain broad and responsible reporting mechanisms, such as anonymous reporting and downward accountability measures. They should also work with law enforcement agencies to strengthen internal integrity and ensure that corruption is punished.

- As part of trust-building activities, conservation actors should create spaces for local communities to express their grievances, establish mechanisms to meaningfully respond to these ideas and complaints, and cultivate ways of reporting back to local communities on how grievances have been handled. This should be done in all cases, even when local perspectives or demands conflict with conservation methodologies, theories, and practices.

Alternatives to extraction and poverty alleviation

- Short-term ‘benefits’ to local communities need to be replaced with sustainable, long-term benefits. A community-level assessment, based on active participatory techniques, should determine how best to improve the lives and livelihoods of the local residents. For example, such assessments should examine how and to what extent projects should aim to improve educational opportunities, household incomes, local infrastructure, and so on. Once the needs have been identified with the community, these objectives should be integrated into conservation programmes and prioritised alongside conservation outcomes. Again, such goals need to be established in partnership with community members and integrated into monitoring, evaluation, and learning frameworks to ensure progress and accountability.

- Learning from successful income-generating initiatives should be embedded in participatory programme design. What determines ‘success’ should be identified and defined by community members. Measures of success will likely include increases in household incomes and the distribution of benefits across a significant number of resident households.

- Studies should calculate current incomes associated with extractive practices. Programmes should attempt to replace those income streams like-for-like so that poor and marginalised groups are not paying the cost of conservation via livelihood reductions. Detailed accounting should determine how employment in NGO/state activities, tangible benefits received from the programme, and additional income from the newly created or adjusted revenue streams are contributing to current and future household incomes. Studies should track how income streams change as project elements progress.

- Needs for local social infrastructure (schools, health centres, and so on) should be identified in consultation with local communities. Conservation organisations should coordinate with other development actors to create shared action plans, with the goal of providing such infrastructure as requested by local communities.

Empowerment and enforcement

- Ensuring equality of enforcement is crucial to achieving successful anti-corruption and conservation outcomes. Punishing poor community members but letting off influential perpetrators of corruption leads to a breakdown in trust. Working with local law enforcement bodies to ensure equality in the application of law is important. Progress towards this goal should be monitored regularly.

- Conservation actors should work to build networks beyond the community with national bodies, media, and civil society to empower local communities and anti-corruption actors in law enforcement.

- Conservation actors should adopt approaches that prioritise human dignity by building on rights-based development methods1562556e4902 to ensure fair treatment of all stakeholders.

- Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023.

- Global Forest Watch, 2023.

- Convention on Biological Diversity, 2023.

- Red List, 2023.

- Anonymous, 2018; Duffy, 2005; Randriamalala and Liu, 2010; Gore et al., 2013; Mandimbihasina et al., 2020; Randria Arson, 2016.

- Sundström and Wyatt, 2017; Sundström 2016; Gore. et al. 2013.

- Klein and Mullard, 2021.

- Martinez et al., 2020.

- Anonymous, 2018; Martinez et al., 2020.

- World Bank, 2022.

- In many cases, the actual GPS defined boundary did not move, but the physical markers did. In one case, a road was built through an area and this had cascading impacts on local stakeholders.

- For a more in-depth discussion of dina, see Klein, 2023.

- See Zhu and Klein, 2022.

- Kusi, 2023.

- UNFPA, 2023.