Caveat

The information presented in this brief is derived primarily from publicly available sources. As such, the completeness and accuracy of the data are subject to the extent of information available. Certain anti-corruption activities or initiatives, particularly those not extensively covered online, may not be adequately represented in this research.

Query

Please provide a summary of the key corruption risks in Burundi, with a focus on the foreign exchange market, land, mining and coffee sectors, and the status of anti-corruption measures, including an overview of existing interventions by international partners.

Overview of corruption in Burundi

Introduction

Burundi’s political landscape has undergone a transformation since the end of its 12-year civil war in 2005. Initially marked by democratic aspirations, the trajectory has gradually veered towards authoritarian tendencies under the ruling party, Conseil National pour la Défense de la Démocratie – Forces pour la Défense de la Démocratie (CNDD–FDD). This shift not only strained relations with international donors but also exacerbated internal tensions, particularly between the nation’s two main ethnic groups, the Hutus and Tutsis, heightening concerns about societal cohesion (UNHCRa 2023; BTI 2024).

The CNDD–FDD transitioned from an armed rebel group founded by Hutu intellectuals during the civil war (1993-2003) to a major political force in Burundi, but its governance has been marked by allegations of corruption and human rights abuses. Elections are marred by corruption allegations, physical violence and authoritarian repercussions against opposition. Freedom House has assessed that elections are not held in a free and fair way (Freedom House 2024). The CNDD–FDD’s youth wing, known as the Imbonerakure, has faced allegations of harassment, arbitrary detention, torture and killings of alleged members of opposition parties and militias on behalf of the country’s security forces (HRW 2022b).

Burundi relies on agriculture, which supports roughly 80% of its population whereas the manufacturing and financial sector are generally underdeveloped. Despite possessing abundant natural resources, Burundi contends with persistent challenges such as poverty, malnutrition and resource scarcity. With a population of 13.2 million, Burundi faces significant pressure on its limited land resources, making it one of the most densely populated countries globally (World Bank 2024b).

The nation’s economic ambitions, as outlined in its national development plan 2018-2027, envision a transition towards becoming an ‘emerging country in 2040 and developed country in 2060’ (PND 2017). However, achieving these aspirations is hindered by a myriad of challenges, including the adverse impacts of global events such as the Covid-19 pandemic and regional conflicts in the Great Lakes region. While poverty is often seen as the key development issue facing Burundi, evidence suggests it is compounded by the existence of systemic corruption (BTI 2024; USSD 2022).

After former president Pierre Nkurunziza made a contentious bid for a third term in 2015, many Western countries imposed sanctions. While sanctions were largely lifted in 2022, their impact reverberates in ongoing efforts to address budget transparency, corruption and governance deficits. Development assistance has not returned to levels before 2015 and focuses largely on low-key support to non-governmental stakeholders (BTI 2024; The Conversation 2022; ICG 2015).

Corruption stands out as a pivotal issue undermining Burundi’s development trajectory, a reality acknowledged by President Ndayishimiye upon assuming office in 2020 following the sudden death of his predecessor Nkurunziza. Despite initial optimism surrounding Ndayishimiye’s leadership, concerns persist regarding his ability to effect meaningful change within the ruling party CNDD–FDD’s elite, given the party’s entrenched grip on power and resources. Despite coming from the military, he was at the time of inauguration described as ‘open-minded’ and not associated with the worst abuses of recent years within the country’s elite (AlJazeera 2020).

Despite rhetorical commitments to governance reforms, education, agriculture and youth development, tangible progress remains elusive. Some observers argue that the efforts to counter corruption, such as the dismissals of select public officials, as well as the lifting of certain restrictions on anti-corruption organisations since 2020, fall short of addressing systemic forms of corruption and root causes of long-standing state capture and impunity among ruling party elites and public officials (BTI 2024; RFI 2021).

Extent of corruption

Burundi faces pervasive and systemic corruption; a reality reflected in global assessments. Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index (CPI) 2023 paints a grim picture, with Burundi scoring 20 out of 100 points, placing it 162 out of 180 countries surveyed. The World Bank’s World Governance sub-indicator (WGI) of control of corruption corroborates these findings, positioning Burundi in the lowest percentile of countries from 1996 to 2022 (World Bank 2024c). The CPI and WGI scores have been mostly stagnating over the past four years (see Figure 1).

Table 1: Burundi’s governance and anti-corruption ranking 2023–2019

|

Index |

2023 |

2022 |

2021 |

2020 |

2019 |

Country ranking |

Range/Scale |

|

TI /CPI |

20 |

17 |

19 |

19 |

19 |

162/180 |

0 lowest, 100 highest |

|

BTI |

3,54 |

3,38 |

N/A |

3,49 |

N/A |

114/137 |

1 lowest, 10 highest |

|

WGI - Control of Corruption |

N/A |

4,25 |

2,86 |

3,81 |

4,76 |

N/A |

0 lowest, 100 highest |

|

Freedom House - political rights |

4 |

4 |

4 |

3 |

3 |

14/100 |

40 highest, 1 lowest |

The 2024 Bertelsmann Stiftung’s Transformation Index (BTI) assessment places Burundi at 119 out of 137 observed countries in terms of political and economic transformation, indicative of deep-rooted governance deficiencies (BTI 2024). The assessment highlighted severe restrictions on political rights, exemplified by instances such as the suspension of the main opposition party’s activities by the interior minister in 2023 (Freedom House 2024). The regime’s use of intimidation, unlawful detentions, torture and arbitrary killings further erodes democratic norms (UNHCR 2023a). Moreover, the alarming number of documented cases of torture, totalling 1,420 in 2023, ‘underscores the grave human rights abuses that accompany the governance crisis’ according to local CSO, Ligue Burundaise des Droits de L’Hommes (Iteka 2024).

The repercussions of corruption extend beyond politics and the economy, impeding access to essential public services such as health and education: 75% of the population in Burundi is multidimensionally poor while an additional 16% is classified as vulnerable to poverty (UNDP 2021). Mismanagement and embezzlement of funds contribute to inadequate service delivery, perpetuating a cycle of poverty and deprivation (BTI 2024).

Furthermore, Burundi’s poor record on civil liberties and media freedom reflects the stifling environment for dissenting voices. Freedom House’s assessment categorises Burundi as ‘not free’, with a score of 14 out of 100 in 2024. Similarly, the World Press Freedom Index ranks Burundi as a hostile environment for journalists (RSF 2023).

Main forms of corruption

Misappropriation, trading in influence, abuse of office

Evidence suggests political leaders in Burundi often exploit their positions to manipulate public contracts such as oil imports, facilitate access to foreign currency reserves, access to land titles or exemptions from taxes and to provide benefits to their supporters or family members. This patronage system generates wealth for allies and ensures their loyalty (see e.g. Freedom House 2024; BTI 2024).

The systemic misappropriation of public resources implicates the highest echelons of the Burundian elite. Former president Pierre Nkurunziza, for instance, was linked to a hydrocarbon company in the Panama Papers leaks, revealing secret foreign accounts worth US$450 million. Dubbed ‘the shareholder’, Nkurunziza was accused of monopolising control over Burundi’s foreign currency reserves and personally profiting from preferential government contracts (Topona 2017; AIPC 2017; ZAM 2017).

Nkurunziza: President nicknamed ‘the shareholder’

According to the Panama Papers and a group of African journalists, it was revealed that former president Pierre Nkurunziza was holding hundreds of millions of dollars in accounts abroad. It was reported that almost the entire reserves of foreign currency went exclusively to an oil trading company called Interpetrol in which the president was said to have a secret stake. President Nkurunziza vehemently denied all accusations (The EastAfrican 2017; DW, 2017).

In 2021, President Ndayishimiye dismissed the Minister of Commerce Immaculee Ndabaneze after she was implicated in an embezzlement scandal involving the sale of aircraft belonging to the defunct airline Air Burundi (NewVision 2021).

A corrupt and manipulated electoral process has undermined the CNDD–FDD legitimacy for the Burundian population and relations with international partners. For example, the government’s controversial decision to fund elections in 2020 by deducting amounts from civil servants’ salaries illustrates the coercive tactics and abuse of power employed to extract resources. Local officials and members of the youth wing of Burundi’s ruling party extorted donations with threats or force. These officials blocked access to basic public services for citizens who could not show a supposedly ‘voluntary’ receipt for their payment. The extorted amounts were the equivalent to 2,000 Burundian francs (US$1.08) per household, 1,000 Burundian francs (US$0.54) per student of voting age. Direct deductions from the salaries of public sector workers and civil servants were made. Some people were forced to pay multiple times or more than the officially requested amount (BTI 2024; HRW 2024).

Administrative corruption

The bribery of low-level public servants is possibly the most common form of corruption experienced by ordinary citizens in Burundi (Justesen 2014). Due to political instability and restricted or lack of cooperation from authorities, data is sometimes outdated or based on anecdotal evidence. The 2014 East African Bribery Index shows that, within 12 months in 2014, 24% of citizens’ encounters with police resulted in bribery, closely followed 21% in the judiciary and 13% in the education sector (Transparency International 2015). Against a background of resource scarcity, courts, health centres, schools and police often play a determining role on who can access public services and receive goods such as medicine and school equipment, which can drive administrative corruption (Rwantabagu 2014).

Administrative corruption is socially tolerated in Burundi because loyalty to social networks outweighs allegiance to public institutions (Nicaise 2020). Recently, the government made some efforts to counter corruption at the local level. For example, in 2021 the minister of home affairs dismissed the accountants in all 119 local councils for diverting local taxes (ENACT 2023; USSD 2022; Nicaise 2019).

Drivers of corruption

Political instability and fragility

Burundi consistently ranks among the most fragile in the world (FFP 2023). Leaders within the CNDD–FDD have prioritised control over economic resources to sustain their regime and fulfil personal economic aspirations. The lack of robust social oversight and electoral accountability both originates from and contributes to political instability and insecurity, shielding Burundian leaders from integrity in governance (Rufyikiri 2016; BTI 2024; USSD 2022).

Weak public institutions

The politically unstable environment has significantly weakened Burundian public institutions at both the national and local levels. The inefficient public administration and the CNDD–FDD regime’s unwillingness to enforce compliance with legal and policy guidelines, including anti-corruption measures, has exacerbated this fragility. For example, the National Strategy for Good Governance and the Fight against Corruption (SNBGLC), initiated in the early 2010s and due for updating in 2020, was undermined by the abolition of the ministry in charge of good governance in 2021, which was supposed to implement the strategy (UNCAC Coalition 2023).

In 2021, the Burundian national assembly reportedly approved a law disbanding the anti-corruption special court and the anti-corruption police brigade in response to criticisms of poor coordination across the anti-corruption architecture. The responsibilities of these entities were transferred to the office of the attorney general and courts of appeals, and to the judicial police, respectively. However, the US State Department report on human rights practices notes that this decision might impede progress in countering corruption (USSD 2021a). BTI argued that the dissolution sends a discouraging message to the public and international partners about the political commitment to curb corruption (BTI 2024). However, some observers argue that these institutions were weak from the onset and reforms were needed (UNCAC Coalition 2023); for example, the Anti-Corruption Court was reportedly vulnerable to political interference and ineffective in addressing impunity (Schutte 2022). In 2023, the government of Burundi testified before the UN Human Rights Committee that reports the Anti-Corruption Court, its prosecutor’s office and the Special Anti-Corruption Brigade had been abolished were false and that they were operating as normal (UN Human Rights Committee 2023).

Lack of transparency

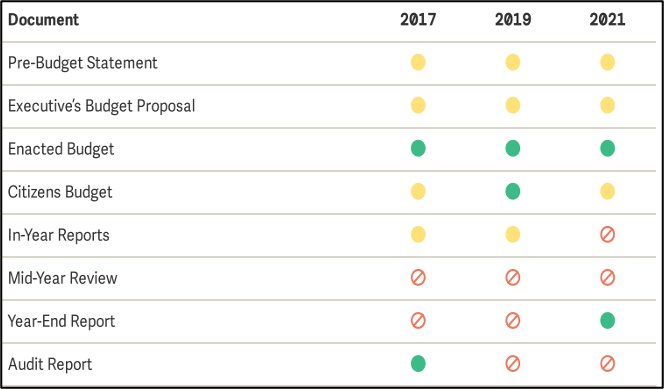

The Burundian public sector and its financial management systems lack basic transparency. There has been some modernisation of digital infrastructure to boost transparency and the availability of data. However, progress in public financial management and budget transparency remains slow, driven primarily by investments from international partners such as the World Bank (World Bank 2024a). According to the Open Budget Survey (OBS) 2021, Burundi ranks at 108 out of 120 countries assessed in the last survey. Civil society and public engagement in budgetary allocations at any level are close to non-existent. Many key documents such as audit reports or financial statements by the state-owned enterprises are not produced or disclosed to the public (OBS 2021; UNCAC Coalition 2023).

Figure 2: Public availability of budget documents in Burundi

Source: OBS 2021.

Resource scarcity

Poverty and economic hardship, including low salaries for public officials, is another important driver of corruption. The vast majority of the population, including civil servants, lives under the poverty level (UNDP 2021). The gross average salary per month of a public administration official ranges between 909,964 Burundian franc (BIF), equivalent to US$318, and BIF1,863,903, equivalent to US$651, in 2024 exchange rates (PayLab 2024). Nicaise (2020) found that “tax collectors’ salaries are so low that they argue they have no other choice but to disregard rules in order to survive”.

Impunity

The Bertelsmann Transformation Index (BTI, 2024) notes that the CNDD–FDD and the country’s security actors have effectively ensured impunity by seizing control of state functions and resources, including law enforcement and the justice system. The national police, under the Ministry of Interior, and the armed forces, under the Ministry of Defence, theoretically fall under civilian authority, but in practice, there is little effective civilian control over these forces. Government and ruling party officials enjoy significant immunity from corruption accusations, human rights’ abuses and other crimes (USSD 2022).

Law enforcement and public institutions are hampered in sanctioning influential leaders involved in corruption due to the pervasive influence of the CNDD–FDD over decision-making processes. The Imbonerakure, the ruling party’s youth militia, reportedly acts unrestricted as the main tool of repression against domestic and foreign activists (ICG 2020). The CNDD–FDD’s influence prevents institutions, civil society and media from achieving the necessary independence and ensures widespread immunity from corruption cases and other crimes (Nicaise 2020).

Suppression of civic space

One of the drivers of corruption in Burundi is the continuous persecution and undermining of civic engagement. President Ndayishmiye’s government has lifted some restrictions on CSOs since 2020, such as ending the suspension of the prominent anti-corruption organisation Parole et Actions pour le Réveil des Consciences et l’Evolution des Mentalités (PARCEM) and some detained rights defenders and journalists have been also released. However, the authorities still exert undue interference in and oversight of civil society and the media, which discourages civic engagement (HRW 2022a; UNCAC Coalition 2023). Some commentators (Vandeginste 2019) argue that a regulation requiring international CSOs active in Burundi to respect ethnic quotas in their staffing has been abused by some political actors to suppress select CSOs.

In 2023, the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights issued a statement condemning the ‘increasing crackdown on critical voices in Burundi’ following the detention of five human rights defenders and the imprisonment of a journalist (UNHCR 2023a). Burundi has established specialised institutions such as the National Human Rights Initiative, the Institute of the Ombudsperson and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission. However, these institutions are seen as ineffective and corrupt and unable to act against the party, military establishment and the feared youth militia. Human Rights Watch has repeatedly criticised Burundi’s National Independent Human Rights Commission (CNIDH) for its lack of independence, credibility and effectiveness, particularly its failure to publicly advocate for the release of detained journalists and human rights defenders (HRW 2024; 2023; 2022a).

Whistleblowing and corruption reporting are effectively stifled. Journalists face intimidation and threats, with some requiring permission from local authorities to travel within the country. Agents of the CNDD–FDD party, public officials and security sector personnel reportedly intimidate and threaten any form of civil engagement that challenges their authority (Nicaise 2020).

Main sectors affected by corruption

Security sector

The National Police of Burundi, under the Ministry of Public Security, is responsible for law enforcement and maintaining order. The armed forces, overseen by the Ministry of Defence, handle external security but also have domestic responsibilities. The National Intelligence Service, reporting directly to the president, has arrest and detention authority and has been involved in investigations into anti-corruption charges (RFI 2023).

Security sector actors are often complicit in the systemic misappropriation of funds and state capture. Security sector officials engage in trading in influence and abuse of power. For example, they are allegedly complicit in the misappropriation of public funds, customs fraud and the diversion of the country’s limited foreign currency reserves to finance imports linked to security sector and ruling party officials (USSD 2022).

Security sector officials wield significant powers across the public administration and private sector. For example, General Adolphe Nshimirimana, a trusted ally of Nkurunziza and head of the secret services, who was murdered in 2015, was accused of running corrupt networks formed by his cronies (DW 2015). In another case, Nshimirimana had bought uniforms and military equipment cheaply in Ukraine and sold this military equipment for inflated prices to the Burundi government (Rufyikiri 2016). Defective military equipment was also purchased for USS$5.6 million from 2008-2010 from a Ukrainian company. At that time, the general state inspectorate estimated that 50% of the purchase value was inflated and that the contract did not comply with the procurement guidelines, implicating ministers and senior army officers (Rufyikiri 2016).

Mining and gold

Despite being a marginal producer of minerals relative to other countries in the Great Lakes region, Burundi faces systemic and widespread corruption linked to its mineral and natural resource sectors, implicating both the government and military. Gold, tin, tungsten and tantalum (known as 3TG minerals) are the most profitable and prevalently smuggled minerals in both Burundi and the broader Great Lakes region (GI-TOC 2023), while valuable minerals such as copper, cobalt and platinum are also smuggled. Corruption and illegal taxes paid to local state agents are pervasive in Burundi’s mining sector. Unofficial payments to state security forces are often seen as legitimate by mining stakeholders. Mining companies and cooperatives frequently underreport their production to avoid taxes and reduce the risk of extortion (ENACT 2023). Local state agents, supposed to supervise and maintain order in mining areas, often engage in mineral fraud or accept bribes to overlook illegal activities. This corruption undermines efforts to formalise and regulate the mining sector (Vircoulon 2019; IPIS 2015). Allegations concerning unfair contracts and illicit outflows have been levelled against international mining companies active in Burundi and in 2021, the Minister responsible mining suspended seven such firms (Tasamba 2021).

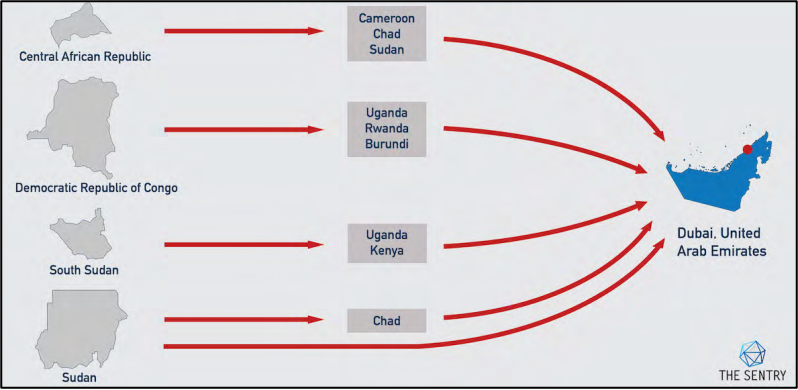

Gold is both locally produced and illicitly imported from the Democratic Republic of Congo, particularly from South Kivu (ENOUGH 2017). Limited data exists on the smuggling networks and routes, but it is believed that gold smuggling has increased in recent years, facilitated by corrupt customs officials who enable exports to the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Europe and Asia via commercial airlines and land routes, exploiting weak screening capacities at the Burundi international airport and land border crossings (ISS, Interpol, ENACT 2021). There are significant discrepancies in official versus estimated gold export statistics. While Burundi officially produced only 0.5 tons of gold in 2018, the UAE imported 3.1 tons from Burundi that year (Lezhnev 2020). This indicates that Burundi serves as a major regional hub for conflict gold from the wider Great Lakes region (OCCRP 2021b).

Figure 3: High-risk gold flows to Dubai from Great Lakes region

Source: Lezhnev 2020: 5.

Agriculture and coffee sector

Agriculture contributes to 80% of Burundi’s GDP, with 90% of the population dependent on it, mostly at the subsistence level (BTI 2024). Land tenure insecurity and land disputes are critical factors contributing to instability and affecting peacebuilding efforts. According to a study by Kasmi and Khan (2021), the imbalance of land ownership and class structure in Burundian society has fuelled decades of armed conflicts, leading to a cascade of social issues such as violence, forced displacement, dysfunctional land governance and shifts in power dynamics.

Corruption exacerbates these problems by undermining a sustainable land tenure system. Public urban lands are often seized by influential figures in the army, police, political spheres and business sectors, who violate existing legal frameworks with impunity, as courts and land officers are unable to challenge them (Turimubumwe et al. 2023). Obtaining land titles and registering land at the local level often involves bribing officials to expedite processes in Burundi. Unauthorised land allocations are perpetuated by government officials, and influential individuals frequently manipulate land allocation processes to benefit themselves or their allies. This includes the unauthorised allocation of public lands and fraudulent land transactions that disenfranchise legitimate landowners. Land laws and related regulations are abused, and Burundian landowners are accustomed to have to repeatedly defend their land titles in front of corrupt judiciary (BTI 2024; Bisoka 2023).

Burundi relies heavily on its coffee sector, which accounts for up to 80% of the country’s foreign exchange earnings. Despite its financial importance, coffee production in Burundi has steadily declined since 1990, leading to reduced income for coffee farmers. This decline is exacerbated by intentional and unnecessary regulatory restrictions imposed by the state, creating severe management challenges and corruption opportunities for private and public actors.The diminishing yields in the coffee sector are a result of ineffective governance, limited export alternatives and institutionalised corruption in the coffee value chain (Rosenberg 2021; Lenaghan et al. 2018).

For example, farmers and cooperatives must pay bribes to officials and commission agents at various levels to receive the necessary certification, permits and access to markets. Additionally, those in charge of purchasing coffee from farmers may demand kickbacks (Sinarinzi 2022).

Illicit trade and customs

In 2022, Burundi ranked as the 190th economy globally in terms of total exports and 179th in total imports, reflecting its limited participation in international trade. This can be attributed in part to the rampant corruption of customs, tax authorities and trade officials (OEC 2024).

Organised crime significantly exacerbates corruption in Burundi by infiltrating state institutions and the private sector, including tax and customs authorities. The Global Organized Crime Index identifies Burundi as highly vulnerable to organised criminality, with limited resilience to counteract it (GI-TOC 2023). Corrupt and ineffective law enforcement, including customs and border controls, enable organised cross-border crime within the Great Lakes region (ENACT, 2023).

Corruption among border guards and customs is a significant factor behind Burundi’s porous borders, which facilitate arms trafficking and other illicit trade. The most common counterfeit goods coming into the country are medical products. Other types of illicit trade are sugar, soft beverages and alcoholic beverages, illegally re-exported to neighbouring countries. These illegal businesses are reportedly in the hands of elite members of the ruling party and their associates (ENACT 2023).

There is widespread abuse of regulations relating to the import of certain goods and services (COFACE 2024). For example, Belgian and Dutch police raids uncovered illegal tobacco manufacturing linked to tobacco smuggled from Burundi through bribing customs officials, undermining measures of the World Health Organization’s Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (OCCRP 2021a).

Reports of bribery and corruption are widespread at major border crossings and the Bujumbura port, indicating systemic challenges in enforcing trade regulations and countering illicit activities such as gold smuggling or human trafficking (ENACT 2023). Trafficking of arms and ammunition has been a long-standing issue in Burundi, involving both civilian and military authorities. The high level of corruption in the military and police leads to inadequately secured weapons and ammunition, which are sold to criminals (GlobalSecurity 2024; ENACT 2023). Corruption among border agents facilitates arms trafficking and other crimes, contributing to high crime rates in affected areas (OCCRP 2021b).

The tax and customs system is characterised by the excessive abuse of discretionary tax and customs exemptions. Corrupt tax and customs officers accept bribes to lower the value of goods and taxes and accept false invoices, which distorts the tax base and lowers tax revenue (Holmes 2021). Tax exemptions are exceptionally high in Burundi. In 2009 and 2014, they represented 21% and 18.3% of total revenues. According to an IMF assessment, tax exemptions on imports, the lack of monitoring of companies to whom incentives have been granted, as well as abuse of the use of certificates granted by the investment regime to purchase goods and services locally without paying taxes, have eroded the tax base. The World Bank indicated that, in 2006, 60% of imports entered with partial or total exemptions, representing an estimated tax revenue loss of 11% of GDP and 66% of tax revenue (Ndoricimpa 2021).

Efforts to reform Burundi’s tax and customs systems have been thwarted by entrenched interests of the elites benefiting from corruption. There were some initial successes in the early 2010s, where tax and revenue collections between 2010-2012 increased by 76% (GlobalSecurity 2024). The Burundi Revenue Authority (OBR) has implemented measures such as performance contracts, a rigorous employee code of conduct, anti-corruption policies and automated customs IT systems. However, resistance from powerful public and private sector figures has hindered the reform of the trade regulations and customs system (GlobalSecurity 2024; Holmes 2021; 2013).

Illicit financial flows (IFFs)

Illicit financial flows (IFFs) cause extensive revenue losses and structural economic damage to Burundi. From 1985 to 2013, Burundi was estimated to have lost resources amounting to US$3.7 billion in 2013 prices or annually 10.2% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the form of capital flight (Ndoricimpa 2021). US$799 million worth of damages were caused by balance of payment leakages and US$289 million through trade misinvoicing. Ndoricimpa (2021) estimates that capital flight from Burundi is higher in comparison to other countries in the East Africa region, in part attributable to the small size of the national economy.

Monetary policy

Monetary policy in Burundi, particularly concerning dual exchange rates, presents significant challenges for the local economy. The existence of parallel foreign exchange markets cause divergent exchange rates, which leads to economic uncertainties and distort resource allocation. They create perverse incentives for rent-seeking behaviours and misreporting, affecting macroeconomic stability and overall economic performance negatively. The government criticises commercial banks for their handling of foreign exchange. The ineffectiveness of the financial intelligence unit underscores ongoing challenges in the financial sector. Falling prices for export products like coffee and the freeze in foreign aid after the 2015 political crisis made foreign currency reserves scarce (Iwacu 2023; IMF 2022b; 2018; The Exchange 2019).

The Central Bank of Burundi (BRB) prioritises specific strategic industries for foreign exchange allocation to mitigate abrupt exchange rate movements, resulting in a significant disparity between the official and parallel market exchange rates (USSD 2021b). In 2020, the BRB suspended the licences of foreign exchange traders accused of illegally trading beyond the 18% margin allowed for official exchange rates. The exchange bureaus reopened in 2022 (BTI 2024).

The BRB, although officially responsible for foreign exchange policy, operates with diminished independence, receiving directives from the head of state on foreign exchange allocation (Iwacu 2023). Corruption is manifested within the current foreign exchange management system through the unequal access to foreign currencies. Well-connected companies managed by the ruling party or connected to the country’s elite can access foreign currency easily at preferential exchange rates. Other private entities without such ties are at a substantial competitive disadvantage (World Bank 2022). The anti-corruption CSO Observatoire de Lutte contre la Corruption et les Malversations Economiques (OLUCOME) blamed widespread fuel shortages in 2017 on favouritism and a lack of transparency as the BRB allocated all US dollar reserves to a single Burundian company, Interpetrol Trading Ltd, to import fuel (Reuters 2017). The BRB governor, Mr Murengerantwari, was arrested and charged with money laundering and the misappropriation of public assets in 2023 (BBC 2023). While unclear, some commentators suggested these allegations related specifically to the misappropriation of foreign reserves (Fatshimetrie 2023).

Legal and institutional anti-corruption framework

Anti-corruption, money laundering and asset recovery legal framework

Burundi has enacted some laws to prevent and counter corruption, such as the Act on Preventing and Combating Corruption, the Act on the General Statute Governing Civil Servants, the Act on the Public Procurement Code, the Act on the Code of Private and Public Companies and the Act on the Fight against Money-Laundering and Terrorist Financing (LBCFT). The public procurement system is governed by the Public Procurement Code(UNODC 2020).

However, implementation is reportedly limited. In view of the lengthy backlog of cases in courts, Burundian prosecution and law enforcement institutions reportedly prefer legal settlements in which the government agrees not to prosecute, and the offending official agrees to reimburse the stolen money. The government exercises power to freeze and seize property and bank assets of officials, although officials implicated in corruption have been permitted to retain their positions in most cases (GlobalSecurity 2024; Freedom House 2024; BTI 2024). The legal framework addresses conflicts of interest in government procurement. Although Burundian law criminalises the bribery of public officials, it does not require private companies to establish internal codes of conduct (USSD 2023a).

The law requires senior public officials to declare their assets upon assuming and leaving office (Article 146 of the constitution). However, this information is not accessible to the public, reducing transparency and limiting public scrutiny. While there is no specific law on asset recovery, relevant provisions are found in the LBCFT and the criminal code (UNODC 2020). The obligation of financial institutions to verify the identity of clients is provided in the legal framework. Financial institutions are supposed to report contacts and business transactions of politically exposed persons (UNCAC Coalition 2023).

Burundi’s legal framework for countering corruption, money laundering and illicit financial flows has significant gaps, including:

- a beneficial ownership regime (Open Ownership 2024)

- access to information legislation

- comprehensive asset recovery mechanisms

- an effective verification system of asset declarations and no sanctions for non-submission of declarations

- regulation of cross-border cash movements

- legal frameworks or systems for elected officials and senior public servants to declare external activities, employment, donations or benefits which could result in a conflict of interest

- an explicit obligation to declare revenues and expenses of third parties who can campaign for or against parties (UNCAC Coalition, 2023; UNODC 2020).

Institutional frameworks

Burundi has a National Strategy for Good Governance and the Fight against Corruption (SNBGLC), established in 2012 and updated in 2020. This strategy includes measures to counter corruption, such as improving the legal framework, enhancing citizens’ access to information, establishing independent monitoring organisations, depoliticising civil service management, ensuring transparent procurement processes, reforming public servant recruitment and reforming the natural resources sector (ICG 2012). However, the implementation of these measures has been undermined since the second half of 2020, when the ministry in charge of good governance and responsible for monitoring and evaluating the strategy, was abolished. Consequently, the strategy was not widely disseminated and remains largely unknown among the public (UNCAC Coalition 2023).

A court of auditors, the general inspectorate of the state, and the national directorate for the control of public procurement are in place and have anti-corruption mandates. The court of auditors should play a crucial role by acting as an external and independent auditor to prevent mismanagement of public finances (BTI 2024; UNCAC Coalition 2023, GlobalSecurity 2024; ABP 2021). Nevertheless, these bodies suffer from a lack of independence and resources, and some operate under political supervision (UNCAC Coalition, 2023).

In 2008, the financial intelligence unit (FIU) was established. However, it has been largely ineffective. As of 2017, the FIU had not received a suspicious transaction report since its inception (UNODC 2020).

An integrated public finance management system was established in January 2015 and connects all ministries and some other institutions with the aim of streamlining public finance management (UNODC 2020).

Judiciary system

The justice system is widely regarded as ineffective and opaque, lacking independence and impartiality, which in turn hinders effective anti-corruption investigations and prosecutions (TRIAL 2020). It is considered generally subservient to the executive, which frequently interferes in the criminal justice system to protect members of the ruling party, CNDD–FDD, and its youth wing, the Imbonerakure, while persecuting the political opposition. In 2021, President Ndayishimiye publicly accused the judiciary of corruption, resulting in the dismissal and sentencing of 40 judges accused of various forms of misconduct or corruption, such as the appropriation of verdicts (Iradukunda 2021).

Since 2020, the government and judiciary have taken some ad hoc steps to identify, investigate, prosecute and punish officials and members of the ruling party involved in human rights abuses or corruption (USSD 2021a). Notable high-profile anti-corruption actions have included the 2023 dismissal and arrest of Burundi’s central bank governor, Mr. Murengerantwari, on charges of money laundering and misappropriation of public assets. In another case, the minister for trade, transport, industry and tourism was accused by the presidency in 2021 of misappropriating funds, but no judicial proceedings were initiated (UNHCR 2023a).

The National Intelligence Service often conducts high-profile arrests, yet the government typically does not communicate any information about these cases. Senior officials accused of corruption or economic embezzlement are sometimes arrested and interrogated secretly, occasionally forced to return some funds. They are rarely given prison sentences. Some are reinstated to their positions while others are dismissed (RFI 2023).

Other stakeholders

CSOs and media

The global civil society alliance, CIVICUS, categorises Burundi as ‘repressed,’ reflecting the country’s restricted civic freedoms. Since the 2015 electoral crisis, there has been a consistent trend of suppressing civil society through legislation that often violates the state’s human rights obligations. This suppression has forced many human rights defenders and journalists into exile.

In 2006, estimates suggested that 2,000 formal CSOs were registered with the Ministry of the Interior, while an additional 5,000 community-based organisations (referred to as groupements) operated in rural areas without official registration. This situation, combined with a heavy reliance on foreign aid and a lack of coordination among formally registered CSOs, contributes to their vulnerability (BTI 2024).

Anti-corruption reporting and monitoring of the ruling party’s abuses of power rests largely on CSOs such as the Observatoire de Lutte contre la Corruption et les Malversations Économiques (OLUCOME) or radio stations such as IWACU. Whistleblowers in Burundi have received support from organisations such as Association Burundaise des Consommateurs-Transparency International Burundi (ABUCO-TI Burundi), which provided judicial assistance to 111 beneficiaries, 96 of whom were involved in cases of corruption in the private sector (UNODC 2022). Ordinary citizens rely almost entirely on CSOs to report corruption or another mistreatment as their ability to use digital media is several restricted. Internet penetration was only 10% in 2023, while only 5% of the total population had social media accounts (Kemp 2023).

The activities of anti-corruption activists and human rights defenders in Burundi are severely restricted. Anti-corruption activists are frequently detained or physically harmed. The vice-chairman of a prominent anti-corruption NGO OLUCOME, Ernest Manirumva, was killed in a knife attack in 2009 (Reuters 2009). The government has politicised CSO activities, conducted smear campaigns in official speeches by political figures and implemented surveillance measures. This shrinking of civic space presents a significant obstacle to anti-corruption efforts in the country (UNCAC Coalition 2023). Despite these pressures, some local civil society organisations, especially those with financial support and solidarity from abroad, continue to operate (BTI 2024).

The media is considered a crucial tool for reporting corruption in Burundi. According to an Afrobarometer survey, 81% of Burundians believe that the press should investigate and report on government mistakes and corruption, and 70% say that the media should be free to publish any views without government interference (Afrobarometer 2014). However, journalists are regularly attacked by the authorities, and media freedom is severely restricted. In a high-profile case, the journalist Floriane Irangabiye was sentenced to ten years in prison on charges of ‘undermining the integrity of the national territory’ in 2023, probably because of her radio talk-show criticising the government and the ruling party for corruption (HRW 2020; 2024).

Regional anti-corruption networks

Burundi is a signatory to the UN Anti-Corruption Convention, the OECD Convention on Combating Bribery and the African Union Convention on Preventing and Combating Corruption. Since joining the East African Community (EAC) in 2007, Burundi has been a member of the East African Anti-Corruption Authority. The country also holds observer status with the Eastern and Southern Africa Anti-Money Laundering Group (ESAAMLG) and participates in various regional networks, such as the Asset Recovery Inter-Agency Network for Eastern Africa (ARINEA), the Network of National Anti-Corruption Institutions in Central Africa (RINAC) and the Asset Recovery Inter-Agency Network for Southern Africa (ARINSA). Burundi formally committed to implementing the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2015 (EITI 2015).

Regional groups like the EAC foster a sense of collective responsibility and exert peer pressure on Burundi to take anti-corruption measures seriously. The East African Association of Anti-Corruption Authorities (EAAACA), for instance, facilitates capacity building programmes, workshops and training sessions on anti-corruption strategies. These organisations have also exercised diplomatic pressure on Burundi, such as during the 2015 constitutional crisis (ISS 2015).

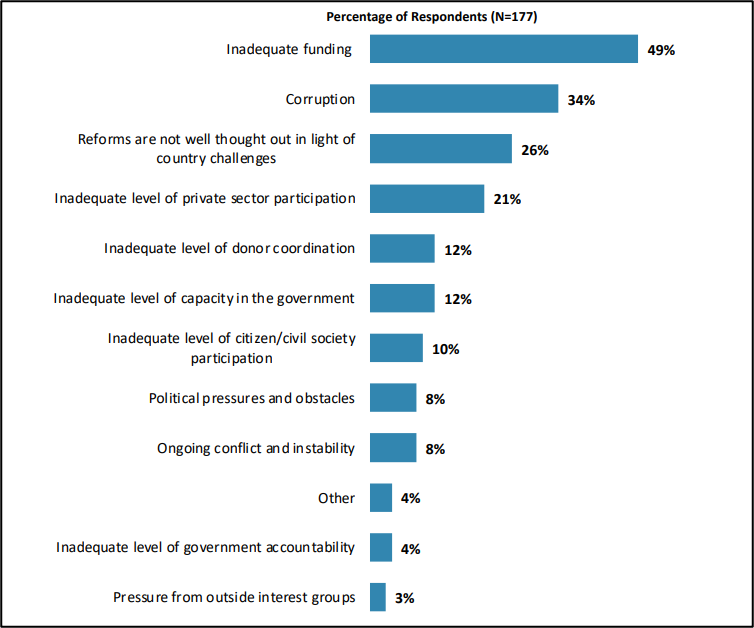

Development cooperation actors

A substantial portion of Burundi’s overall budget and investment capacity relies on oversees development assistance (ODA) from multilateral and bilateral development partners. Around 40% of Burundi’s annual budget flows through some form of ODA with the World Bank Group, United States and the European Union as the top three donors between 2020-2021 (OECD 2024). A World Bank survey among key development partners and governance stakeholders in 2021 highlighted corruption as the second most important factor hindering governance reforms (World Bank 2021).

The public frequently complains about corruption in development and humanitarian assistance. However, as Uvin (2009: 68) explains, the reason why corruption comes up when the public talk about international aid ‘is not because aid agencies are uniquely corrupt but because this is one of the few flows of money or goods that come close to the poor’.

Figure 4: Attributions for slow/failed reform efforts in Burundi according to development partners and governance stakeholders

Source: World Bank 2021.

Annex

The following is a non-exhaustive list of several initiatives of international donors and partners that provide technical assistance to Burundi’s governance sector and highlights if and how these initiatives have addressed corruption. In some cases the initiatives have not directly addressed corruption but have addressed linked or tangential governance issues.

Table 2: Interventions that address corruption

|

Donor/partner |

Initiatives |

Relevance to corruption |

|

European Commission |

PRESCIBU TUYATUZE: Strengthening Burundian Civil Society against GBV, Budget: €1 million Duration: 2022-2025 |

Funding is granted to eight CSOs to strengthen the role of civil society organisations in good governance and the socio-economic development of the country. |

|

Swiss Cooperation and the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands |

Synergies for peace in Burundi: Phase III, Duration: 3 years since 2022, January 2022 to December 2024 |

The programme aims to contribute to reconciliation and to more accountable and inclusive governance for peacebuilding and development in Burundi and includes workshops to promote good governance in general, including anti-corruption. |

|

Netherlands Enterprise Agency |

LAND-at-scale project, Budget: €4,310,481, Duration: 1 December 2021 to 31 May 2025 |

The objective of this LAND-at-scale project is to improve tenure security of women and men, conflict resolution and to create the basis for improved agricultural production, access to justice and sustainable, climate smart agri-businesses. |

|

Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs through the Power of Voices Partnership |

Strengthening Civil Courage - Burundi, Budget: US$25,000 Duration: 2021 to 2025 |

The main objective is to support Burundian human rights defenders and civil society organisations whose leadership is in exile, and human rights monitors in Burundi (they gather information for human rights CSOs). Another important target group are victims and families of victims that have experienced grave human rights violations. |

|

Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs and VNG International |

Sustainable Development through Improved Local Governance (SDLG) Duration: 2020 to 2025 |

The multi-county programme focuses on four thematic priorities: security & rule of law, migration, local revenue mobilisation, and integrated water management. In Burundi, the project aims at empowering citizens to be better informed and claim accountability to engage in inclusive decision-making in the communes in Cibitoke and Makamba. |

|

Belgium Technical Cooperation |

Soutien à la société civile pour un développement inclusif au Burundi, Budget: €939,782, Duration: 2022 to 2026 |

Through civic participation, the initiative aims to bring about a paradigmatic shift towards an approach to development based on the rule of law and human rights. Under outcome 1 ‘Grassroots organizations and CSOs improve their methods of engagement with duty bearers’, it is expected that CSOs and grassroots organisations improve their capacity to serve as bridges between affected populations and duty holders |

|

World Bank |

Modernization of Public Financial Management, Budget: US$42 million |

|

|

Enabel – formerly Belgium Technical Cooperation, European Union |

JUSTIBUR Project (Justice Sector Support Program), Duration: 2022-2025 |

The JUSTIBUR Project (Justice Sector Support Program) contributes to strengthening the rule of law and the respect and protection of the human rights of all by ensuring that leave no one behind. Its specific objective contributes to improving judicial governance for justice that is faster, independent, impartial, gender-sensitive, digital and close to right holders. |

|

BMZ Germany through GIZ |

Peace work and civil society networks in the Great Lakes Region, Duration: 2023 to 2025 |

The civil society partner organisations promote cross-border dialogue to resolve conflicts non-violently, deal with differences constructively and counteract the instrumentalisation of young people. |

|

BMZ Germany through GIZ |

Duration: 2022 to 2026 |

The promotion of sustainable raw material supply chains and sustainable mineral resource supply chains through the support of the regional certification mechanism to prove the conflict-free origin of mineral resources and to further develop and professionalise services in mineral resources. |

|

African Development Bank |

EACPayment and Settlement Systems Integration Project (EAC-PSSIP) Duration: 2012 to 2024, Budget: United Arab Emirates dirham, AED15,000,000 (around €3,750,000) |

The multi-country project aims to modernise, harmonise and integrate payment and settlement systems to foster regional convergence and integration. It seeks to bolster a unified legislative and regulatory framework for the financial sector across EAC partner states including: i) integration of financial market infrastructure; ii) harmonisation of financial laws and regulations; and iii) capacity building. |

|

USAID |

Fiscal Accountability and Sustainable Trade (FAST) to conduct a Domestic Resource Mobilization (DRM) and a Public Finance Management (PFM) assessment. Duration: April 2022 to October 2022 Budget: US$ 201,186 |

The main objective is to inform USAID on the current state of the DRM and PFM systems in Burundi and to provide actionable and programmatic recommendations for future interventions with USAID support. |

|

GIZ |

The Social Cohesion Fund in Burundi Duration: 2018 to 2022 |

The fund promotes social cohesion. Anti-corruption is not a specific focus, but the project supports CSOs in human rights, gender-based violence and political manipulation. Media support has also been provided. |

|

European Union |

Multiannual Indicative Programme (MIP) Duration: 2021 to 2024, Budget: €194 million |

The majority of programming is earmarked for priority area 1: ’Inclusive, green, sustainable, and job-creating growth’ and priority 3, good governance and rule of law. Civil society actors and authorities within the framework of the democratic process are supported. It also encourages the capacities of the media to contribute to the development of a free environment that is pluralistic, independent and conducive to national reconciliation with monitoring and protecting of human rights. |