Query

Please provide an overview of how civil society organisations (CSOs) can contribute to lower corruption in fragile settings. Please include any good practices in CSO community engagement and the provision of channels to report wrongdoing.

Caveat

This Helpdesk Answer focuses on how CSOs can contribute to positive change in fragile settings. That is not to overlook the risks that are associated with working with local, smaller CSOs. The UNODC notes that, where there are weaker institutional safeguards, external funding can sometimes lead to the opportunistic creation of CSOs that promote or conceal corruption schemes (UNODC no date: 15). Moreover, CSO are not neutral entities acting only in the interest of the common good; CSO can be politized, business oriented and can vary in their capacities and governance.Nonetheless, there are safeguards5f5c1cac540d that can be put into place so that any support given benefits society and does not have the adverse effect of increasing corruption. The work of local CSOs is still considered by many to be significantly important to holding the state to account and raising the voices of all citizens, particularly the most vulnerable, despite the associated risks (Oxfam 2013).

Background

Almost a quarter of the world’s population live in fragile states and these countries generate most of the global refugee population (OECD 2022 a). Both lower and higher income countries are vulnerable to fragility, with those previously thought to be resilient at risk of becoming weaker in an ever more connected globe (FFP 2022: 11).

Today, understandings of the concept of fragility go beyond the traditional focus on state structures and violence and instead highlight that formal institutions are not the sole determinants of fragility (Jenkins 2020: 6). As such, the OECD characterises fragility as a multidimensional state which is “the combination of exposure to risk and insufficient coping capacities of the states, system and/or communities to manage, absorb, or mitigate those risks” (OECD no date). The contexts of fragility are measured across six distinct dimensions: economic, environmental, political, security, societal, and human (OECD no date; OECD 2022 b: 9). Each dimension measures vulnerabilities to different risks, for example, the human dimension refers to vulnerability to risks affecting people’s well-being, ability to live long and prosperous lives, the reduction of inequalities, and the provision of social services (OECD 2022 b: 9).

International donors typically respond to these risks with increased volumes of official development assistance (OECD 2022 a). For example, in 2020, the volume of aid from all donors in fragile contexts peaked at US $91.4 billion (OECD 2022 a). While this could provide short-term relief to citizens in fragile settings, the OECD emphasises that inclusive, legitimate institutions remain central to exiting fragility (OECD 2022 a).

To build these strong state institutions, levels of corruption need to be controlled. However, in these fragile settings, corruption – the “misuse of entrusted power for private gain” (Transparency International no date a) – can run rampant as accountability mechanisms that typically hold those in power to account may be weak or missing entirely (DIIS 2008).

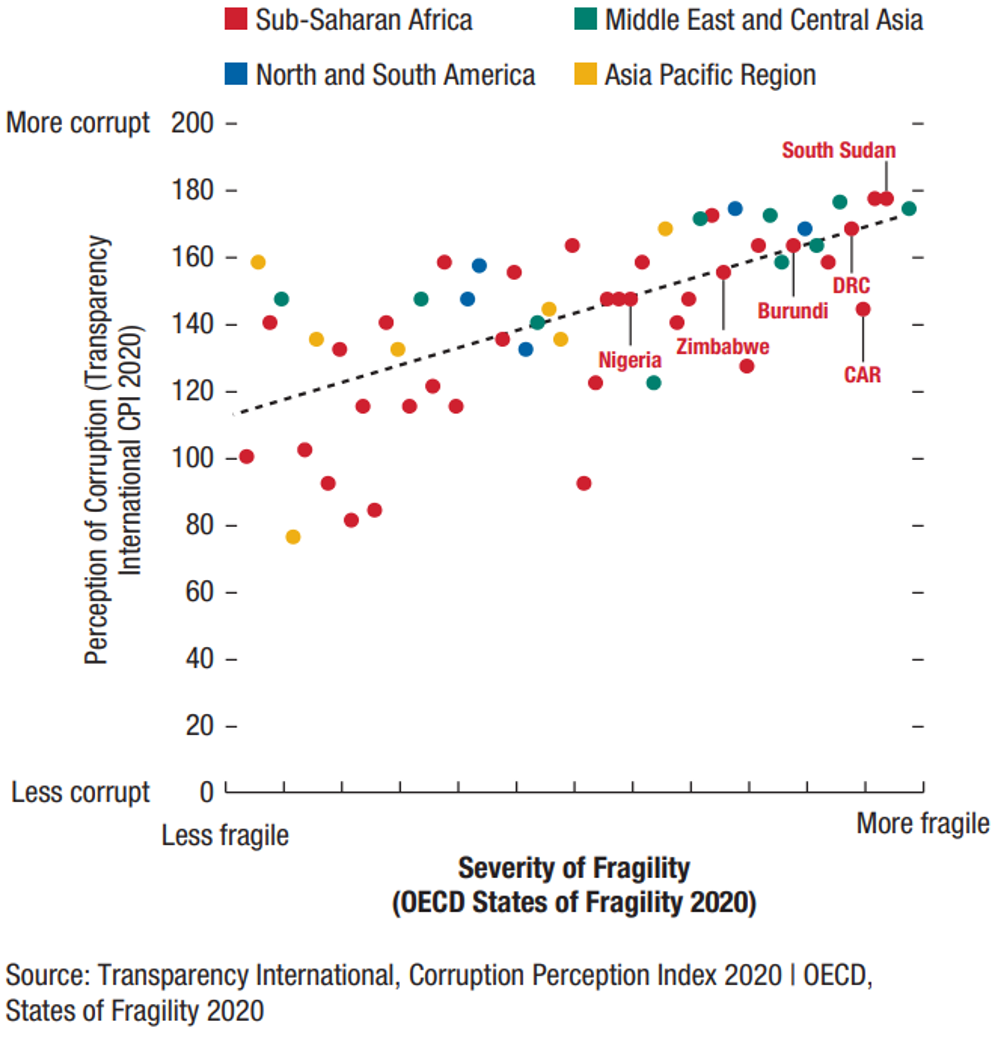

From 2008, there is the recognition that anti-corruption interventions can have a stabilising effect in a fragile state (DIIS 2008). Evidence now shows the importance of addressing corruption as a necessary precondition to development, poverty reduction and exiting fragility (Pompe 2022). As seen in the below graph, there is a strong correlation between the severity of fragility and levels of perceived corruption, with many of the lowest income countries having high levels of both.

Correlation between the severity of fragility and levels of perceived corruption

Source: Pompe 2022: 131

Confronting corruption should therefore be part of the parcel of building legitimacy and public confidence in fragile states (DIIS 2008). However, the challenge does remain of how to ensure anti-corruption strategies are not counter-productive but ensure local ownership, sustainability and that they build trust between the state and citizens.

Without careful selection of appropriate anti-corruption measures, these interventions are at risk of causing more harm that than good in fragile settings (DIIS 2008). For example, many anti-corruption commissions in sub-Saharan Africa failed (after being promoted by bilateral and multilateral development agencies such as the World Bank) and are dependent on the executive with very little real impact (Anders 2019; DIIS 2008). An outcome like this could cause the additional problem of increasing citizen apathy towards anti-corruption interventions, as they only see the reality of failed interventions with little independence from the ruling elite.

The literature, therefore, highlights the importance of designing interventions that keep in mind that there is no “one-size-fits” all reform strategy (Johnston 2010: 14; Jenkins 2020: 19). To help assess these differences, Johnston identifies four types of “syndromes” of corruption that reflect the nature of a states’ political economy (Johnston 2010). These are based on the premise that corruption arises as a result of the ways that people exchange wealth and power and in the strength or weakness of the state and social institutions that should control these processes (Jenkins 2020). The four syndromes that Johnston identifies are:

Influence markets:mature democracies with strong state/society capacity as well as strong economic institutions. The normal expectation is that corruption is the exception rather than the rule that, when it occurs, is addressed through crime prevention strategies or attempts to rebalance incentives.

Elite cartels: consolidating or reforming democracies with a reforming economic market and moderate state/society capacity and economic institutions. Corruption typically makes use of high-level networks. Certain governance capabilities that are important for economic development and service delivery are greater than the latter two syndromes, although they may rely on elite collusion. The expectation is that corruption will be extensive but predictable.

Oligarchs and clans: transitional regimes with new markets and weak state/society capacity and economic institutions. It is dominated by a few powerful figures that contend and compete, which leads to a climate of pervasive insecurity for citizens and oligarchs alike. Expectations are that corruption will be the norm.

Official moguls: undemocratic states with new markets and weak state/society capacity and economic institutions. Corruption is dominant and corrupt rulers wield state power with impunity and intrude into the economy and tap into flows of aid and investment. Expectations are that corruption can be practiced more or less with impunity (Johnston 2010: 17-19).

According to Johnston, as fragile states generally have weaker institutions, they typically fall under the “oligarchs and clans” and “official moguls” syndromes (Johnston 2010: 14). Zaum, building on the differences within these two syndromes in fragile settings, highlights that anti-corruption efforts need to understand the underlying political economy and drivers of corruption (Zaum 2013). This means that long-term investments in institutions and initiatives need to take place, and that what works is context-dependent, particularly in fragmented oligarchic contexts (Zaum 2013).

Five anti-corruption interventions for the foundations of reform for “oligarchs and clans” and “official moguls” are therefore proposed by Johnston, namely: crime prevention, incentives, civil society action, liberalisation, and international treaties and conventions (Johnston 2010: 7-8). Civil society organisations (CSOs)962ec671e62c can provide the civil society action interventions proposed here, and this bottom-up measure enables public participation through giving a collective voice to citizens (UNODC no date: 12).

As Zaum notes, supporting civil society is a longer-term tactic and will help to generate and articulate demands for reforms (Zaum 2013). As such, it is an important intervention for both the “oligarchs and clans” and “official moguls” syndromes of corruption (Zaum 2013). In support of this approach, much of the literature on fragile contexts stresses that assisting grassroots initiatives and local accountability mechanisms are perhaps one of the only viable anti-corruption options (Schouten 2011; UNODC no date).

Ultimately, and perhaps most importantly, the state of fragility can provide a window for change, particularly when addressing issues such as corruption (OECD 2012: 92). It is difficult to remove corruption once it is entrenched within a political system; therefore, the period during fragile contexts where new institutions and political systems are being created offers an opportunity to build in anti-corruption measures and accountability systems from the start (OECD 2012: 92).

This Helpdesk Answer looks at the different CSO led anti-corruption interventions in fragile states, while bearing in mind that there is no one-size-fits-all solution. Indeed, some of these interventions may fit a certain context better than others as some (such as advocacy) carry more risk, and each should be carefully assessed before implementation.

The solutions proposed in this paper are trust-building, supporting citizens to report corruption and the implementation of social accountability tools, all of which are considered by the literature as apt methods of instituting long-term change in fragile settings. Finally, this paper addresses the role of international donors and how they can better support these bottom-up anti-corruption initiatives.

Challenges in fragile settings

Fragile states are often characterised by a lack of social trust among citizens which is manifested in the form of collective action problems (Johnston 2010: 13). In terms of the proliferation of corruption in fragile settings, this means that corruption is seen as “normal” and therefore fewer people will abstain from engaging in it or taking the first step to implement sanctions if they perceive that everyone else is acting individually (Marquette and Peiffer 2015).

Therefore, conventional approaches to anti-corruption, such as the establishment of an anti-corruption commission, may fail in fragile states because of systemic/pervasive corruption and its social acceptance by people to access public service delivery. An additional hurdle to these types of approaches is that there may be a lack of independence from the executive (Schouten 2011: 2), which is common in both the “oligarchs and clans” and “official moguls” corruption syndromes. As weaknesses in the legal system are common, enforcement led approaches may be detrimental (Schouten 2011: 2). Judicial institutions such as autonomous public prosecution, effective freedom of information acts and an ombuds office to field citizen claims may be absent or dysfunctional (Grimes 2008: 16).

Additionally, the top-down organisation of anti-corruption groups, citizen watch organisation or mobilising public opinion will often fail for the reasons of low trust and lack of credible leadership (Johnston 2010: 9).

Advocacy efforts to influence government policies, which are often a tool for CSOs working in anti-corruption, may have different implications in fragile states. Advocacy can be more dangerous and face opposition from the government in these contexts (Fisman and Golden 2017; Marquette and Peiffer 2015 cited in Florez et al. 2018). Fragile states are often under authoritarian regimes (OECD 2022 a), and this means advocacy efforts by CSOs may be placed under more severe constraints under fear they could encourage political discontent among the public (Li et al. 2017).

A World Bank study on CSOs in Guinea Bissau found that, when people were asked to identify their primary needs, they listed social sector needs, with none identifying governance issues (Dowst 2009). The report stated that “when people lack even the most basic social services, can they really be that concerned with democracy and governance issues?” (Dowst 2009). Indeed, a major challenge that will face CSOs in their anti-corruption efforts will be to raise community awareness of the implications of poor governance, such as poverty, inequality, and deepening fragility.

Furthermore, civil society may be vulnerable to official resistance and repression (Johnston 2010: 9). Societal fragmentation7b0c1be314ce, a core feature of fragile states, often stands in the way of establishing a strong civil space in fragile settings (Pompe 2022).

As set out in this section, top-down anti-corruption measures can risk causing additional problems, for reasons such as anti-corruption agencies lacking independence from the executive and an absence of long-term support from donors in fragile settings (Schouten 2011: 2; Johnston 2010: 8). Some argue that these risks mean that anti-corruption interventions should be avoided in fragile contexts altogether (Mathisen 2007). However, many others still contend that the risks of not engaging are higher than those of engagement (OECD 2021: 3). The following section will document several CSO led interventions that have been recorded by academics and development practitioners that have made positive impacts in fragile settings.

Anti-corruption solutions led by CSOs

Building trust within and between communities

Local CSOs have an important role in building trust in fragile states as, through their local roots, they typically have social capital (Duthie 2009). Indeed, opinion surveys in the global south have found that the public generally has a favourable view of CSOs that advocate for rights and democratic values (Bishop and Wike 2017).

The social cohesion they can foster can maintain resilience by encouraging relationships and areas of cooperation and providing stability in an otherwise turbulent world (Aall and Crocker 2019). These organisations typically have a level of legitimacy that arises from their close connection with society (Aall and Crocker 2019). Their work can create a space for a dialogue that allows for active participation of local people, allowing for greater ownership and resulting in more sustainable interventions (Amatya 2020).

While trust-building is not an anti-corruption intervention itself, it is integral to create the pre-conditions for later anti-corruption initiatives. Measures that strengthen the social contract through deepening trust result in a greater societal resilience to fragility in the future (Jenkins 2020).

Building trust also reduces the risk of communal violence in fragile societies. An open society with a well-developed civil society permits people to have an identity which is not limited to ethnicity or religion and allows for public debate to be encouraged, whereby members of diverse communities have equal rights as citizens (Human Rights Watch 1995).

Local mechanisms (which can be identified or facilitated by local CSOs) should be supported to build trust and strengthen local conflict resolution mechanisms in fragile settings. The OECD gives the example of building trust among adversaries in the African Program and Leadership Project at the Woodrow Wilson International Centre for Scholars, which brought together leaders in workshops to address tensions and mistrust that resulted from conflict in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Liberia (OECD 2011). Their aim was to use a “broader conceptualisation of capacity building to develop improved communications between parties and to enhance collaboration across all ethnic and political divisions” with the aim to build relationships and lasting peace (OECD 2011). While this example is not directly related to anti-corruption, such an approach could be employed in all interventions in fragile settings, as one of the first steps should always be to ensure that communities can work together, and social trust can be built. In an activity like this, local CSOs and other grassroots organisations would play an important role in the facilitation and trust-building process.

Service delivery

Johnston identifies that early actions against corruption in fragile states should be aimed at earning basic credibility (Johnston 2010: 5). In the absence of credible public institutions, CSOs may initially have a major role in social service delivery before they can move on to advocacy or policy influence (World Bank 2005).

These interventions should focus on corruption in the delivery of public services and pick at “low hanging fruit” as these are essential to building public trust (Johnston 2010: 5). Through providing public services in a reliable, transparent manner this builds trust within society for future anti-corruption interventions. Moreover, through providing such services without demanding bribes from the public, this decreases the level of everyday corruption that community members experience.

In Burma, for example, direct assistance to the government was not possible as using the country systems for aid delivery was challenging (DFID no date: 8). Humanitarian aid was channelled through CSOs in support of the national disease control programmes (DFID no date: 8). DFID notes that, where the state lacks legitimacy and capabilities, these bottom-up community driven development approaches are an alternative (DFID no date: 9). Here, funds are channelled directly to communities to help build local capacities through participatory approaches, which rebuilds links between the community and the state (DFID no date: 9).

Identifying corruption hotspots

Noting that there is no one-size-fits-all solution to corruption in fragile states, Chopra and Isser argue that “one of the biggest gaps in designing context-specific approaches is the lack of empirical data” in these contexts (Chopra and Isser 2012: 357).

While universally accepted norms such as those in international instruments are important, they are not self-implementing, and their interpretation must reflect local diversities (World Bank 2011: 39). The World Bank therefore emphasises that “regional institutions can bridge the gap between universal norms and local customs, such as those in the delivery of justice, where institutional models may not reflect the actual delivery of justice in certain contexts” (World Bank 2011: 39).

Here, local CSOs have played an important role in researching corruption in their contexts, identifying local patterns, hotspots and networks of corruption. Where international actors will not have the knowledge or access to communities in fragile settings, local CSOs can provide this empirical data that can be built on to design future anti-corruption interventions. They can help ensure that there is an institutional fit between demands, reforms and capacities with local contexts. CSOs will understand the local power dynamics and have a key role in supporting inclusive political dialogue and strengthening accountability mechanisms (Schouten 2011: 4).

Since 2010, Transparency International Rwanda (TI RW) has published the Rwanda Bribery Index (RBI) which analyses the experience and perception of Rwandans about bribe incidences in the country (TI RW 2022). TI RW conducts annual surveys in all four provinces of Rwanda and the City of Kigali in 11 randomly selected districts with 2,475 respondents (TI RW 2022).

Their data on the level of perceived corruption and its likelihood and prevalence of corruption in Rwanda has been used to provide evidence for their advocacy in curbing corruption (TI RW 2022). It allows the TI RW to assess information about areas susceptible to corruption and the opportunity to exert influence against corruption where it is found (TI RW 2022). As an example, in 2022, they identified that the private sector and the traffic police were the institutions where the likelihood of being asked for a bribe was the highest (TI RW 2022).

Supporting people to report corruption

The cost for an individual of acting against corruption is particularly high in contexts where corruption is the norm, such as in states characterised by both weak state/society capacity, weak institutions and oligarchic rivalry. In these contexts, individuals may be hesitant or afraid to speak out as reporting corruption may lead to social disapproval and perhaps even physical danger (Fisman and Golden 2017; Marquette and Peiffer 2015 cited in Florez et al. 2018).

The motivations to report corruption can be viewed as a series of decisions taken by individuals based on the information they have at any given point in time, coupled with a cost-benefit analysis (Florez et al. 2018). The internalised choice to act against corruption means that the perception of the “viability” of the anti-corruption mechanism is essential (Florez et al. 2018). This means that CSOs can help to raise the profile of these safe mechanisms where individuals can report corruption and, through successful cases, raise the cost-benefit analysis for people planning to report.

Approaches such as those led by advocacy and legal advice centres (ALACs) have helped empower citizens and counter citizen apathy (an issue commonly seen in “oligarchs and clans” and “official moguls” syndromes of corruption) through introducing innovative approaches to citizen participation (McCormack and Doran 2014 cited in UNODC no date). These centres provide free and confidential advice and support to victims and witnesses of corruption and advocate on behalf of communities for legislative, institutional, administrative and procedural change (Transparency International no date b).

ALACs have supported citizens in over 60 countries to report cases of petty corruption (Transparency International no date b), many of which are classified as fragile states. In Nigeria, they have helped residents in Abuja speak out against bribery in the supply of electricity (Debere 2021). Officials were demanding around US$70 for supplying pre-paid meters to residents’ businesses, and once the complaints were filed to the local ALAC, they wrote to the managing director of the Abuja Electricity Regulatory Commission, asking them to investigate the matter (Debere 2021). As a result, the commission provided the pre-paid meters to residents free of charge and promised the situation would be addressed (Debere 2021). Since, the intervention, no new complaints about bribery in the electricity supply sector have been brought forward (Debere 2021).

ALAC experts in Papua New Guinea, a post-conflict country with high levels of corruption and violence (CSIS 2022), gave an individual legal advice on a land rights dispute that resulted in the mediator demanding facilitation payments (Debere 2021). The ALAC experts advised the victim on the laws governing the village mediators and anti-corruption officers wrote to the country’s chief magistrate on the issue (Debere 2021). As a result, both mediators were suspended and the case has gone before court, where the ALAC is providing advice to support the individual navigate the legal system (Debere 2021). To further support the community in reporting corruption, the ALAC has successfully lobbied for a complaints desk at the lands department, rather than just a complaints box, which has now been expanded to a fraud and complaints unit (Debere 2021).

Educating communities on corruption and their rights

One of the core concepts behind anti-corruption is that information is a rational incentive, in that, humans make decisions based on cost-benefit calculations (Farag 2018 a). Therefore, if the public are better informed about corruption and the benefits of reporting it (and subsequently preventing further corruption), this can incentivise citizen action (Farag 2018 a). Local CSOs can educate their local communities and therefore incentivise them to act against corruption.

Training and awareness campaigns led by local CSOs on the rights of citizens can enable them to identify corruption and available counter measures, where they exist (Baez Camargo 2018). It can, for example, highlight that while gift-giving may be commonplace within a culture, this is not an appropriate act with public officials and can constitute a bribe (Baez Camargo 2018). If citizens feel intimidated by public officials, CSOs can raise awareness about how to safely expose corruption while protecting the reporting person’s identity (Baez Camargo 2018).

As an example of this, a study on local social accountability in the health sector in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, revealed that a lack of information among citizens about their rights and entitlements caused resignation to poor service quality in the health facilities (Baez-Camargo and Sambaiga 2015). They believed that receiving health care in exchange for a bribe was “the normal state of affairs” (Baez-Camargo and Sambaiga 2015).

Capacity building activities consequently focused on helping users identify abuses of power and how to confront corrupt individuals (Baez-Camargo and Sambaiga 2015). As a result, the participants reported feeling empowered and became resource persons for others in their community for advice on how to confront corruption (Baez-Camargo and Sambaiga 2015). Notably, the survey respondents in this study considered non-state actors, that is, local associations and CSOs, to have the greatest impact on community welfare (Baez-Camargo and Sambaiga 2015: 266).

Local community complaints mechanisms

Local community complaints mechanisms are an intervention that can enable citizens to report instances of corruption and misconduct where humanitarian aid is being distributed. They are developed alongside community members and include a complaints committee that is responsible for receiving and responding to community complaints and ensuring the community is aware of their right to complain (Wood 2011). Depending on the context, committees can be composed of representatives from government, community institutions (such as the church), village leaders, beneficiary household members and other stakeholders (Wood 2011). Community awareness raising must be conducted and then a physical space for the complaints established (Chêne 2013). This can include complaints registers, offices, desk, telephone line and suggestion box, among others (Chêne 2013).

According to World Vision International, community complaints mechanisms increase transparency and accountability, develop better relations with community members, and prevent potential harm caused by international aid and development projects in fragile settings (Wood 2011). They are particularly useful in contexts where humanitarian aid is being distributed as these programmes have regular contact with local communities (Chêne 2013: 2). For example, World Vision International implemented a feedback box form, with information in both English and Arabic, in its food assistance programme in South Darfur (Ammerschuber and Schenk 2017). This allowed beneficiaries to raise any concerns (anonymously or not) with the programme staff (Ammerschuber and Schenk 2017).

Crowdsourcing platforms

Crowdsourcing platforms are online tools that can be used to collect information and enable citizens to anonymously report corruption. Through these reports they can identify trends and where corruption is most likely to happen (Dykes and Kossow 2018). One example of this is Development Impact Lab’s Citizen Feedback Model (CFM). The CFM aggregates and publicises user-reported data on corruption and the quality-of-service delivery at Indian government offices (DIL no date). It then creates a score on the quality-of-service delivery and extent of bribe-taking for each office (DIL no date). These scores are communicated back to citizens through a mobile app or SMS messaging (DIL no date). Similarly, in Mali, the mobile phone application KENEKANKO alerts users on verified cases of corruption and human rights violations (KENEKANKO no date). These can be viewed by the user on a map interface to show the localities which are affected by these alerts (KENEKANKO no date).

Another crowdsourcing platform, Ushahidi, helps communities turn information into action through its crowdsourcing and mapping tool. In Kenya, it was used to make the voting process more transparent and peaceful and to encourage civic participation in the electoral process (Ushahidi 2022). Data was collected from citizens during this period, which was verified to evaluate how credible it is and forwarded to organisations and individuals for intervention where necessary (Ushahidi 2022). As an example, citizens reported incidents where marginalised groups, such as people with disabilities, were denied their vote at the polling stations (Ushahidi 2022). The platform was then used to escalate these reports to the National Council of People with Disabilities for immediate action (Ushahidi 2022).

Protection for people who report corruption

Johnston identifies that in the “oligarchs and clans” syndrome of corruption one of the recommended tactical interventions is the implementation (or advocating for the implementation) of protection mechanisms for whistleblowers (Johnston 2010: 26). Evidence suggests that in low-income countries, many of which are fragile states, whistleblowing has a key role to play as an accountability tool in countering corruption as it provides a bottom-line assessment that targets corruption, recoups stolen funds and institutes effective control over public and corporate resources (Okafor et al. 2020). Therefore, protection mechanisms are a first step in ensuring people can report safely.

Reporting to an ALACs, or any CSO that facilitates the reporting of corruption, can also help to anonymise the reporting person to ensure their protection. Anonymity is an important step in ensuring the physical safety of an individual as this means that the persecutor will not know who reported against them. The CSO can then bring the case of corruption forward without the individual’s identity and safety being compromised.

Reporting corruption in fragile states may be particularly dangerous for an individual (Fisman and Golden 2017; Marquette and Peiffer 2015 cited in Florez et al. 2018). Where institutionalised protection for those who report corruption is weak (such as legislation on the protection of whistleblowers that is enforced) CSOs can fill a gap by providing protection for those who report corruption.

For example, the CSO African Defenders (a network of five African sub-regional organisations), provides protection, including temporary relocation, to human rights defenders throughout the continent (African Defenders no date). There is a growing consensus that the work of whistleblowers, if motivated by human rights concerns, should come under the same protections of those offered to human rights defenders (Lawlor 2022).

Nonetheless, any advocacy by CSOs aimed at changing whistleblower legislation should be conducted with caution as governments in fragile states tend to view advocacy less positively than service delivery interventions (Dowst 2009: 6). It is recommended, therefore, that in fragile states, advocacy work should be conducted in collaboration with external actors, such as influential international organisations, to bring about significant changes (Dowst 2009: 6).

Social accountability tools

Social accountability tools allow CSOs to work directly with citizens, and they use participatory methods to ensure their voices are heard as part of the solution (Thindwa 2017). They are important for monitoring the work of public officials and identifying instances of corruption, particularly in the delivery of public services.

In fragile settings, citizen led (and CSO supported) social accountability measures lay the ground for longer term institution building, promote social cohesion and strengthen resilience (Thindwa 2017). Social accountability tools are typically used to advance vertical accountability, but when employed by CSOs can also support horizontal and diagonal accountability mechanisms too. Each of these different forms of accountabilitya91a97e82de0 have a role to play in stabilising a country (Walsh 2020). A growing body of evidence shows that social accountability efforts led by CSOs can serve to create new effective vertical mechanisms of accountability and strengthen existing horizontal ones (Agarwal, Diachok & Heltberg 2009; Fox 2015; Aceron 2018).

Advocating for transparency

Local CSOs are important in demanding the right to information and government, which is a key mechanism of vertical accountability and necessary for the application of social accountability tools that monitor government performance.

Freedom of information (FOI) laws give the public the right by law to access facts and data concerning the exercise of any public authority (Transparency International no date c). This is a powerful tool for exposing corruption, and the anti-corruption potential of it highlights the importance of transparency in promoting accountability and engendering public participation (Transparency International no date c). Moreover, a study on European countries found that respect for freedom of expression and information was significantly related to citizens’ trust in government (Briguglio and Spiteri 2018).

It can be a challenge for CSOs to advocate in fragile settings, due to the high levels of violence, conflict and restrictive regimes characteristic of fragile states (OECD 2022). The Lifeline Fund for Embattled CSOs offers guidance on how CSOs can advocate for transparency, among other goals, in restricted spaces (Greenfield 2020). They note that small steps should be identified, risk mitigation plans should be implemented and how entry points may come from alternative sources such as community elders and religious leaders (Greenfield 2020).

In Sri Lanka, Transparency International Sri Lanka (TI SL) advocated for the public disclosure of asset declarations of elected representatives to use to counter corruption (TI SL 2019)7fdcbdc7b431. The law existed for members of parliament to submit these declarations already, but not to provide this for public dissemination (TI SL 2019). They used social media and traditional media to create public awareness for International Anti-Corruption Day in 2018, leading to several MPs expressing their willingness to disclose their asset declarations to the public (TI SL 2019). This then led to more MPs choosing to submit their asset declarations to TI SL, which had never happened in Sri Lanka before (TI SL 2019). This was a smaller step towards transparency being enshrined in national law.

Another example of CSOs demanding transparency this is the Transparency and Right to Information Programme (TRIP) in Bangladesh which adopts a multi-stakeholder approach and worked with the government, civil society and private sector actors to empower citizens and demand accountability from local authorities (Jenkins 2020: 25).

The project strengthened collective action at the local level and empowered citizens to work together and demand accountability from public officials (Jenkins 2020: 25). Lessons from their 2022 annual review concluded that quick wins were important to build legitimacy and trust throughout the project, and stakeholders were more engaged with their project when its progress offered tangible benefit (FCDO 2023).

Additionally, the Partnership for Transparency Fund is a not-for-profit organisation that supports innovative CSO led approaches to reducing corruption and increasing transparency, particularly in low-income economies (PFT no date a). In Malawi, in partnership with CoST Infrastructure Transparency Initiative Malawi, they delivered training programmes to develop the institutional capacities of local CSOs to monitor infrastructure project procurement as well as budgetary expenditures on infrastructure procurement at the district level (PTF no date b). The results of this project are expected to include increased political commitment by local governments to integrity in public procurement and increasing capacity of local CSOs to monitor procurement in publicly financed projects and in their ability to demand accountability (PTF no date b).

Monitoring development outcomes

Research shows that civic space is required to provide accountability and to ensure that public services are delivered as they can identify the needs for services and criticise poorly functioning services (World Bank 2004). Citizen monitoring is also an important step in providing checks on corrupt public officials outside of the electoral process (Rose-Ackerman 2001).

Community scorecards can be used by community members to identify how public services are being experienced by users, report on the quality of services and track whether they are progressing well (CARE 2013). These were first implemented by CARE Malawi in 2002 as part of a model to improve health services and is a participatory tool that can be conducted at the local level (CARE 2013). However, it should be noted that the use of scorecards to report corruption is limited in countries with a low freedom of expression.

To summarise the process, the CSO, along with selected community members, assesses the priority issues and barriers to quality of services; indicators are then developed to assess the priority issues; the scorecard scores against each indicator and gives reasons for this scoring; and general suggestions are put forward for improvement (CARE 2013). The scorecard is then conducted with the service providers, and a meeting with both the providers and community members is set up to agree an action plan (CARE 2013).

Evidence on the effectiveness of community scorecards in fragile and conflict affected contexts finds that they result in increased transparency and community participation in public services and, in the case of health care (as assessed by the study), improved quality of care (Ho et al. 2015). Other evaluations of projects using community scorecards have similar findings, that their use led to improved service delivery and uncovering that public officials had failed to adhere to procurement guidelines (Escher no date).

Integrity pacts also provide a commitment from a contracting authority to comply with best practice and provide transparency, with a local CSO to then monitor the commitment made (Transparency International no date d). In 2013, TI Honduras exposed a corruption scandal in the purchase, sales and distribution of medicines to state hospitals, which led to an integrity pact being signed with the Ministry of Health and major pharmaceutical companies (Transparency International no date d). This resulted in increased access to information and compliance with open data principles (Transparency International no date d).

World Vision International has designed and implemented a citizen voice and action (CVA) model, which is an evidence-based social and accountability mechanism that aims to strengthen direct accountability to improve public services (Katende 2018). The CVA model can be implemented in contexts where there are weak transparency and accountability systems and where corruption and mismanagement of resources has led to poor public service delivery (Katende 2018). It does this through providing communities with knowledge on government responsibilities and platforms for citizens to influence local governments to fulfil these commitments (Katende 2018). The CVA model includes the following key steps:

Citizens are identified by individuals or CSO partners who will lead the CVA process at the local level

Relevant government policies and standards are identified and translated into contextually appropriate materials by World Vision International staff

Awareness-raising activities regarding these government policies are undertaken through meetings or mass media communications to local communities

Local government and service providers are consulted and agree to participate in the process

A CVA Facilitation Team is trained (preferably from among existing local civil society groups)

The CVA Facilitation Team compares the actual condition of public services against government standards and measures this on score cards

Meetings take place between the local government, CVA Facilitation Team, and the wider community to discuss the findings from the score cards and to develop an action plan to improve the public services going forward (World Vision International 2017: 12-14).

Social audits

Social audits scrutinise public officials’ decisions and/or actions, looking for administrative, legal or financial irregularities (Farag 2018 c). They can also support demands for greater transparency from a government. Social audits are entry points for citizen engagement into anti-corruption and gives citizens insights into the inner workings of public institutions (Farag 2018 c). They also help to create active citizens and strengthen relationships between local CSOs and citizens (Farag 2018 c).

The social audit is initiated by CSOs that then recruit, train, and coordinate the participation of citizens in the auditing process (Farag 2018 c). There are two types of social audit: compliance (or procedural) social audits that identify administrative or financial irregularities, and performance evaluation (or substantive) social audits that analyse the social impact of public institutions, programmes or services (Farag 2018 c).

A CSO can provide the training and legal documents to the citizens for them to conduct their review (Farag 2018 c). Requesting this information through online registers, submitting information requests, and appeals and legal complaints (Farag 2018 c). Once this information has been collected, volunteers (that have signed a memorandum of understanding or a code of conduct) undertake the social audit through reviewing the documents, and optionally attend field visits, assessing the transparency portals used, and getting people to sign petitions to support or amend the right to information law (Farag 2018 c).

A civil society-led social audit is effective in countering corruption in both reactive and preventive ways. For example, in Andhra Pradesh, India, a social audit uncovered five types of red flags and corrupt practices related to the local government (Aiyar and Kapoor Mehta 2015). Civil society has taken initial steps to build political support for the social audit process through engaging the then chief minister of the state (Aiyar and Kapoor Mehta 2015). This buy-in was essential to ensuring that the civilians could access the requested documents and information (Farag 2018 c).

The audit uncovered that funds had been diverted through faking workers’ attendance sheets; the local civil servants were in fact working alone, signatures had been forged, the measurement of completed works had been inflated so that higher public funds were committed to a project, and other activities were inflated to receive higher payments (Aiyar and Kapoor Mehta 2015).

Monitoring budget work

Participatory budgeting is another social accountability tool used to provide a space for citizens to monitor national and local budgets. It is defined as a process or mechanism through which citizens participate in decision-making around the allocation of public resources (Wampler cited in Shah 2007). Participatory budgeting presents an opportunity to engage citizens in fundamental budget decisions, which is important in the context of democracy deficits and dwindling trust in politicians and political institutions (Torcal and Christmann 2021). It aims to increase transparency and accountability of the government and provide additional checks and balances on the budget process (Shapiro 2007). Greater citizen and civil society involvement in these decision-making processes results in greater decentralisation of the decision-making authority and thus diminishes opportunities for corruption.

There can be two different forms of participatory budgeting: top-down, which is government led and passes through parliament, and bottom-up participatory budgeting that is civil society driven and involves grassroots organisations and citizen initiatives (Willmore 2005). One example is of Porto Alegre, Brazil, where participatory budgeting was implemented to challenge corruption and clientelism in the Brazilian political culture (LGA 2016). Neighbourhood assemblies convened in churches and union centres across the city of Porto Alegre to discuss the funding allocations for 16 city districts (LGA 2016). Through these district meetings the Council of the Participatory Budget was formed, which then refined and applied budget rules (through consultation in the neighbourhood meetings) and proposed these to the city councillors (LGA 2016). It was considered a wide success as marginalised groups who were usually excluded from the political process were included and resources were allocated more effectively (LGA 2016).

Strengthening the enabling conditions for CSOs

As noted by the literature, if the international community wants to build resilience in fragile states, they should apply foreign assistance to support these CSOs so they can fulfil their watchdog roles and empower these organisations to help design and implement country-specific plans (Blake and Quirk 2020; Aall and Crocker 2019).

Financial support from international donors is often short-term and investments are not driven by long-term strategies and priorities (World Bank 2005: 14). Due to the weak capacity of local CSOs, donors are reluctant to fund them long term and funding is often subcontracted through INGOs (World Bank 2005: 14). This has reported to be a concern by local CSOs, as they are unable to make longer term investments (and therefore increase their internal capacity) and too much time is wasted in searching for resources (World Bank 2005: 14). Recommendations to the international community is to therefore provide longer term funding with overheads included.

The international community can also provide technical assistance to local CSOs, where requested. CSOs in Togo and Guinea Bissau noted that, with only a few organisations within the country, they are forced to do a bit of everything without the relevant expertise (World Bank 2005). They remarked that international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) have greater technical capacity than local CSOs, therefore a sustained relationship between INGOs and local CSOs (with an investment in the latter) was put forward as a solution (World Bank 2005: 14).

Finally, as mentioned in the previous sections, local CSOs may be unable to conduct advocacy in fragile states, due to government repression or an immediate need for service delivery instead (Dowst 2009: 6). Here, this is where the international community can perform anti-corruption advocacy and put pressure on the government on their behalf, particularly by influential countries and international organisations (Dowst 2009: 7). However, these advocacy actions should be informed by local information gathered with and by in-country civil society actors.

- This Helpdesk Answer uses the definition of CSOs explained by the UNDP: “voluntary organisations with governance and direction coming from citizens or constituency members, without significant government-controlled participation or representation” (UNDP no date). This differentiates from international non-governmental organisations (INGOs) which are defined by the UNDP as: “a distinct category among non-state actors, which have been very prominent in development cooperation during the past decade. They constitute a subset of NGOs in which coalitions or families of NGOs, based in various donor and developing countries, have formally associated in an international or global governance structure” (UNDP no date).

- Societal fragmentation refers to “the absence or underdevelopment of connections between a society and the grouping of certain of its members. These connections may concern culture, nationality, race, language, occupation, religion, income level, or other common interests” (UIA no date).

- Vertical accountability: institutions and actions that make the government accountable to the people through elections or political parties.

- Horizontal accountability: the checks and balances that are in place and used by the legislative and judicial branches of government to hold the executive branch accountable.

- Diagonal accountability: means that media and civil society have to hold the government accountable through, for example, the spread of information, publicity, protests and other forms of engagement (Walsh 2020).

- While Sri Lanka is not necessarily considered a fragile state, it has some characteristics in common with fragile states. For example, its 2022 economic crisis and citizen distrust in the political regime are both common features that is shares with fragile states.

- See page 94 of the OECD’s Managing Risks in Fragile and Transitional Contexts for more information on how donors can reduce the risks of corruption when working with local CSOs.